#A chestnut tree

Text

I remember seeing a little bit of an episode of Beauty and the Beast (the weird 80s show; not the Disney movie lol) and noticing the similarities to another thing I had just seen, not even an hour before (I was seven-ish), and went, “Wow that’s a weird coincidence… twice in one day?? What.”

Anyway… I started thinking about that movie because of an article I read… and then that made me think of that weird series again… so I looked up the episode list.

Hoooooly shit I was not aware of the sheer amount of whump in Beauty and the Beast

Everyone gird your loins; I’m about to enter critical hyperfixation levels

#[Dr. Smith voice] “I am being s u m m o n e d” [walks off into the sunset like a zombie]#uh oh#it’s the “hyperfixation chain reaction” at it again#It’s not done#oh god#o fuk#o lei o lai o lord#< and thanks to a Tumblr post about a certain alternate version of a certain character from a certain sci fi show#I now associate that song with [someone] who is very relevant to the whole reason I am interested in THIS series#so of course I would put that in the tags#I got Pavloved so hard; ring the bell and watch me beg (that came out unintentionally 😏ohohoHO but whatever)#But I have a feeling that I need to recharge the mother root of the hyperfixation chain reaction#Not the seed; the root#And the tree in the bog and the bog down in the valley-o#No literally… all my interests? They’re one big expansive root system#All part of the same tree#A chestnut tree#Aaaaaaand CUT#Currently vibrating like a jackhammer#aieou#OUIOUIOUIIIUIIIIOIIIOOGH

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

There, in the sunlit forest on a high ridgeline, was a tree I had never seen before.

I spend a lot of time looking at trees. I know my beech, sourwood, tulip poplar, sassafras and shagbark hickory. Appalachian forests have such a diverse tree community that for those who grew up in or around the ancient mountains, forests in other places feel curiously simple and flat.

Oaks: red, white, black, bur, scarlet, post, overcup, pin, chestnut, willow, chinkapin, and likely a few others I forgot. Shellbark, shagbark and pignut hickories. Sweetgum, serviceberry, hackberry, sycamore, holly, black walnut, white walnut, persimmon, Eastern redcedar, sugar maple, red maple, silver maple, striped maple, boxelder maple, black locust, stewartia, silverbell, Kentucky yellowwood, blackgum, black cherry, cucumber magnolia, umbrella magnolia, big-leaf magnolia, white pine, scrub pine, Eastern hemlock, redbud, flowering dogwood, yellow buckeye, white ash, witch hazel, pawpaw, linden, hornbeam, and I could continue, but y'all would never get free!

And yet, this tree is different.

We gather around the tree as though surrounding the feet of a prophet. Among the couple dozen of us, only a few are much younger than forty. Even one of the younger men, who smiles approvingly and compliments my sharp eye when I identify herbs along the trail, has gray streaking his beard. One older gentleman scales the steep ridge slowly, relying on a cane for support.

The older folks talk to us young folks with enthusiasm. They brighten when we can call plants and trees by name and list their virtues and importance. "You're right! That's Smilax." "Good eye!" "Do you know what this is?—Yes, Eupatorium, that's a pollinator's paradise." "Are you planning to study botany?"

The tree we have come to see is not like the tall and pillar-like oaks that surround us. It is still young, barely the diameter of a fence post. Its bark is gray and forms broad stripes like rivulets of water down smooth rock. Its smooth leaves are long, with thin pointed teeth along their edges. Some of the group carefully examine the bark down to the ground, but the tree is healthy and flourishing, for now.

This tree is among the last of its kind.

The wood of the American Chestnut was once used to craft both cradles and coffins, and thus it was known as the "cradle-to-grave tree." The tree that would hold you in entering this world and in leaving it would also sustain your body throughout your life: each tree produced a hundred pounds of edible nuts every winter, feeding humans and all the other creatures of the mountains. In the Appalachian Mountains, massive chestnut trees formed a third of the overstory of the forest, sometimes growing larger than six feet in diameter.

They are a keystone species, and this is my first time seeing one alive in the wild.

It's a sad story. But I have to tell you so you will understand.

At the turn of the 20th century, the chestnut trees of Appalachia were fundamental to life in this ecosystem, but something sinister had taken hold, accidentally imported from Asia. Cryphonectria parasitica is a pathogenic fungus that infects chestnut trees. It co-evolved with the Chinese chestnut, and therefore the Chinese chestnut is not bothered much by the fungus.

The American chestnut, unlike its Chinese sister, had no resistance whatsoever.

They showed us slides with photos of trees infected with the chestnut blight earlier. It looks like sickly orange insulation foam oozing through the bark of the trees. It looks like that orange powder that comes in boxes of Kraft mac and cheese. It looks wrong. It means death.

The chestnut plague was one of the worst ecological disasters ever to occur in this place—which is saying something. And almost no one is alive who remembers it. By the end of the 1940's, by the time my grandparents were born, approximately three to four billion American chestnut trees were dead.

The Queen of the Forest was functionally extinct. With her, at least seven moth species dependent on her as a host plant were lost forever, and no one knows how much else. She is a keystone species, and when the keystone that holds a structure in place is removed, everything falls.

Appalachia is still falling.

Now, in some places, mostly-dead trees tried to put up new sprouts. It was only a matter of time for those lingering sprouts of life.

But life, however weak, means hope.

I learned that once in a rare while, one of the surviving sprouts got lucky enough to successfully flower and produce a chestnut. And from that seed, a new tree could be grown. People searched for the still-living sprouts and gathered what few chestnuts could be produced, and began growing and breeding the trees.

Some people tried hybridizing American and Chinese chestnuts and then crossing the hybrids to produce purer American strains that might have some resistance to the disease. They did this for decades.

And yet, it wasn't enough. The hybrid trees were stronger, but not strong enough.

Extinction is inevitable. It's natural. There have been at least five mass extinctions in Earth's history, and the sixth is coming fast. Many people accepted that the American chestnut was gone forever. There had been an intensive breeding program, summoning all the natural forces of evolution to produce a tree that could survive the plague, and it wasn't enough.

This has happened to more species than can possibly be counted or mourned. And every species is forced to accept this reality.

Except one.

We are a difficult motherfucker of a species, aren't we? If every letter of the genome's book of life spelled doom for the Queen of the Forest, then we would write a new ending ourselves. Research teams worked to extract a gene from wheat and implant it in the American chestnut, in hopes of creating an American chestnut tree that could survive.

This project led to the Darling 58, the world's first genetically modified organism to be created for the purpose of release into the wild.

The Darling 58 chestnut is not immune, the presenters warned us. It does become infected with the blight. And some trees die. But some live.

And life means hope.

In isolated areas, some surviving American Chestnut trees have been discovered, most of them still very young. The researchers hope it is possible that some of these trees may have been spared not because of pure luck, but because they carry something in their genes that slows the blight in doing its deadly work, and that possibly this small bit of innate resistance can be shaped and combined with other efforts to create a tree that can live to grow old.

This long, desperate, multi-decade quest is what has brought us here. The tree before me is one such tree: a rare survivor. In this clearing, a number of other baby chestnut trees have been planted by human hands. They are hybrids of the Darling 58 and the best of the best Chinese/American hybrids. The little trees are as prepared for the blight as we can possibly make them at this time. It is still very possible that I will watch them die. Almost certainly, I will watch this tree die, the one that shades us with her young, stately limbs.

Some of the people standing around me are in their 70's or 80's, and yet, they have no memory of a world where the Queen of the Forest was at her full majesty. The oldest remember the haunting shapes of the colossal dead trees looming as if in silent judgment.

I am shaken by this realization. They will not live to see the baby trees grow old. The people who began the effort to save the American chestnut devoted decades of their lives to these little trees, knowing all the while they likely never would see them grow tall. Knowing they would not see the work finished. Knowing they wouldn't be able to be there to finish it. Knowing they wouldn't be certain if it could be finished.

When the work began, the technology to complete it did not exist. In the first decades after the great old trees were dead, genetic engineering was a fantasy.

But those that came before me had to imagine that there was some hope of a future. Hope set the foundation. Now that little spark of hope is a fragile flame, and the torch is being passed to the next generation.

When a keystone is removed, everything suffers. What happens when a keystone is put back into place? The caretakers of the American chestnut hope that when the Queen is restored, all of Appalachia will become more resilient and able to adapt to climate change.

Not only that, but this experiment in changing the course of evolution is teaching us lessons and skills that may be able to help us save other species.

It's just one tree—but it's never just one tree. It's a bear successfully raising cubs, chestnut bread being served at a Cherokee festival, carbon being removed from the atmosphere and returned to the Earth, a wealth of nectar being produced for pollinators, scientific insights into how to save a species from a deadly pathogen, a baby cradle being shaped in the skilled hands of an Appalachian crafter. It's everything.

Despair is individual; hope is an ecosystem. Despair is a wall that shuts out everything; hope is seeing through a crack in that wall and catching a glimpse of a single tree, and devoting your life to chiseling through the wall towards that tree, even if you know you will never reach it yourself.

An old man points to a shaft of light through the darkness we are both in, toward a crack in the wall. "Do you see it too?" he says. I look, and on the other side I see a young forest full of sunlight, with limber, pole-size chestnut trees growing toward the canopy among the old oaks and hickories. The chestnut trees are in bloom with fuzzy spikes of creamy white, and bumblebees heavy with pollen move among them. I tell the man what I see, and he smiles.

"When I was your age, that crack was so narrow, all I could see was a single little sapling on the forest floor," he says. "I've been chipping away at it all my life. Maybe your generation will be the one to finally reach the other side."

Hope is a great work that takes a lifetime. It is the hardest thing we are asked to do, and the most essential.

I am trying to show you a glimpse of the other side. Do you see it too?

#american chestnut#hope#climate change#biodiversity crisis#climate crisis#trees#plantarchy#learning to imagine the future

3K notes

·

View notes

Text

rumble in the jungle

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

Landscape with canal and chestnut tree - Jan Toorop , 1889.

Dutch, 1858 - 1928

Oil on canvas , 66.2 x 75.7 cm

395 notes

·

View notes

Link

The Biggest American Chestnut He’d Ever Seen

In November 2019 an exciting discovery connected the Delaware Nature Society (DelNature) with a past that few of us had known. Bret Lanan was hunting deer in a remote corner of our Coverdale Farm Preserve in Greenville when his keen eyes spotted what he suspected was a mature American chestnut tree. He alerted DelNature Land Steward Dave Pro, who quickly assembled our staff and Bill McAvoy, the state botanist.

Bill confirmed that it was indeed a healthy American chestnut (Castanea dentata)! He excitedly declared it to be the biggest one he’d ever seen. Based on its diameter, he estimated it to be at least 50 years old...

#american chestnut#chestnut#trees#plants#botany#ecology#forests#nature#outdoors#environment#north america#conservation#biology#science#good news

3K notes

·

View notes

Photo

In the garden. Värmland, Sweden (May 19, 2018).

989 notes

·

View notes

Photo

horse chestnut by the pond

July 2022

#original photographers#photographers on tumblr#lensblr#nature photography#woods#forest#trees#horse chestnut#leaves#leaf#pond#water#stump#reflections#summer#colours#dark nature#aesthetic#forestcore#naturecore

3K notes

·

View notes

Link

Excerpt from this story from the New York Times:

Billions of chestnuts once dominated Appalachia, with Americans over many generations relying on their hardy trunks for log cabins, floor panels and telephone poles. Families would store the trees’ small, brown nuts in attics to eat during the holiday season.

Now, Mr. French and his colleagues at Green Forests Work, a nonprofit group, hope to aid the decades-long effort to revive the American chestnut by bringing the trees back onto Appalachia’s former coal mines. Decades of mining, which have contributed to global warming, also left behind dry, acidic and hardened earth that made it difficult to grow much beyond nonnative herbaceous plants and grasses.

As coal continues to decline and many of the remaining mines shut down for good, foresters say that restoring mining sites is an opportunity to prove that something productive can be made of lands that have been degraded by decades of extractive activity, particularly at a moment when trees are increasingly valued for their climate benefits. Forests can capture planet-warming emissions, create safe harbor for endangered wildlife species and make ecosystems more resilient to extreme weather events like flooding.

The chestnut is a good fit for this effort, researchers say, because the tree’s historical range overlaps “almost perfectly” with the terrain covered by former coal mines that stretched across parts of eastern Kentucky and Ohio, West Virginia and western Pennsylvania.

Another advantage of restoring mining sites this way is that chestnut trees prefer slightly acidic growth material, and they grow best in sandy and well-drained soil that isn’t too wet, conditions that are mostly consistent with previously mined land, said Carolyn Keiffer, a plant ecologist at Miami University in Ohio.

Since 2009, Green Forests Work has helped plant more than five million native trees, including tens of thousands of chestnuts, across 9,400 acres of mined lands. Over that time, the group has collected supporters, including U.S. Forest Service rangers trying to bring back the red spruce onto national forests in West Virginia, and bourbon companies interested in the sustainability of white oak trees that are used in barrels to store and age whiskey.

[Green Forest Works] also planted 625 chestnuts in a one-acre space they called a progeny test to evaluate the health of hybridized chestnut trees — fifteen-sixteenths American chestnut and one-sixteenth Chinese chestnut — that were crossbred by scientists at The American Chestnut Foundation, a nonprofit group formed in the 1980s.

The Chinese chestnuts had co-evolved with the fungus, making them resistant to the blight’s effects. The scientists then infected the part-American, part-Chinese chestnuts with the fungus to pick out the ones that survived. Then, they repeated that process over several generations.

3K notes

·

View notes

Text

Vincent van Gogh, Blossoming Chestnut Branches, Auvers-sur-Oise, May 1890

Vincent van Gogh, Horse Chestnut Tree in Blossom, Paris, May 1887

Vincent van Gogh, Chestnut Tree in Blossom, 1890

Vincent van Gogh, Chestnut Trees in Blossom, 1890

Vincent van Gogh, Avenue with Flowering Chestnut Trees at Arles, 1889

#vincent van gogh#post impressionist art#post impressionism#dutch artist#dutch painter#chestnut#trees#nature#landscape#landscape painting#landscape art#french art#french painting#floral#floral art#floral painting#flowers#flowers in art#flower art#modern art#art history#aesthetictumblr#tumblraesthetic#tumblrpic#tumblrpictures#tumblr art#aesthetic#beauty

85 notes

·

View notes

Text

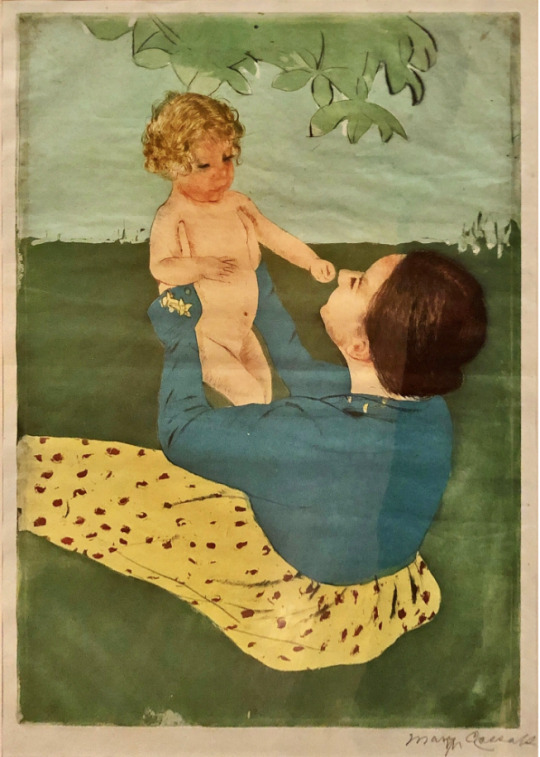

Mary Cassatt (US 1844-1926)

Under the Horse Chestnut Tree (1897)

Drypoint and aquatint on green paper

#mary cassatt#1897#american art#mother and child#horse chestnut tree#etching#aquatint#drypoint#the metropolitan museum of art

73 notes

·

View notes

Text

One of my American chestnuts sprouted!!!

#there’s several in there#I figured I’d do a few in a small batch#please read about the plight of the American chestnut#and also the tree that misses mammoths (unrelated but a good read)

65 notes

·

View notes

Text

#photographers on tumblr#original photography#summer#garden#greenery#flowers#cottage#countryside#blossom#trees#warmcore#landscape#horse-chestnut tree#sunny

53 notes

·

View notes

Text

The most "???????" thing I found in r/collapse though was a thread talking about the "extinction" of the American Chestnut tree...the whole thing, but in particular this fucking comment

the implication that right after the blight started, "settlers" suddenly got the idea of cutting down all the trees. Does this person think a tree has to be already dead to be cut down for wood?

"there was no breeding project or attempt at all at saving them" shut up. just shut up. i beg

"University extensions are encouraging people to cut down healthy ash trees so they can sell the timber" ..."they?" The university extensions?

So for context, the American chestnut is NOT extinct, it has been the subject of intensive breeding programs with a broad and robust genetic base for decades, genetic engineering has been used to create trees with blight resistance that are now being planted and the work is continuing, I have had the privilege of speaking with some of the people that have devoted their entire lives to saving this tree, and let me FUCKING tell you, the eighty-year-old gentleman walking with a cane did not hobble painstakingly up a mountain to the chestnut grove for some dumbass to say "boohoo so sad that there were no breeding programs for american chestnut tree"

I cannot even describe how humbling it was to hear the old folks speak about the decades they worked to save the American Chestnut tree, long before the technology now being used to create blight resistant trees even EXISTED. It is a quest that will take multiple human lifetimes to complete, the people that began it will never see the trees grow old, but they made it their life's mission anyway.

I'm just...unable to understand why someone would say something like that. How could someone be so attached to their sad, dismal fantasy of apocalypse that they either fail to learn about, or outright lie about, a much more beautiful truth????

LOOK AT HER, YOU BITCH.

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

costume gacha illustration icons!!

[part 6]

#cookie run#cookie run ovenbreak#crob#snow sugar cookie#fire spirit cookie#cotton candy cookie#millenial tree cookie#chili pepper cookie#chestnut cookie#spinach cookie#timekeeper cookie#popping candy cookie#cookie run icons#my icons#pizzas icons

94 notes

·

View notes

Text

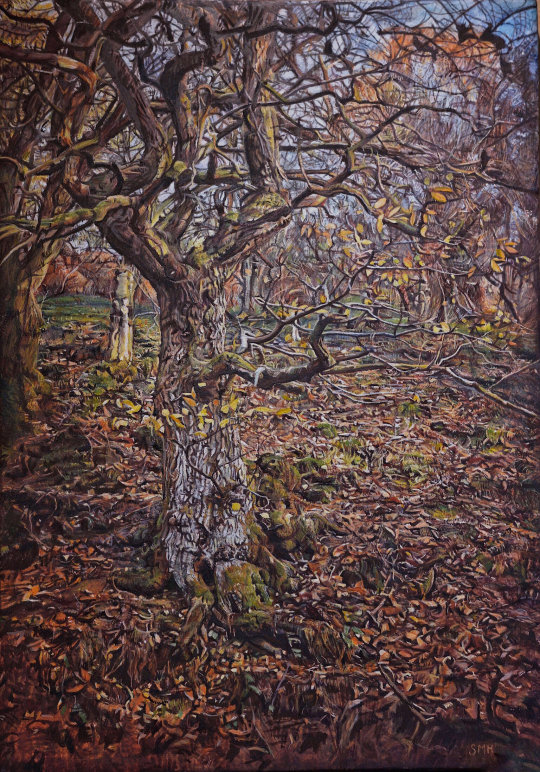

Chestnut Tree - Sarah Harding , 2018.

British , b . 1960s -

Egg tempera on guesso , 21.5 x 15.5 cm.

159 notes

·

View notes

Link

For Judd, the chestnut is a solution to environmental and economic problems facing the area. The chestnut is a perennial crop, meaning it doesn’t have to be replanted every year, so it’s a better moneymaker than the annual monocultural agricultural system that dominates so much of the American landscape. It grows easily in a variety of environments, from Maine to Florida. As a source of protein and carbohydrates, the chestnut – nicknamed “the bread tree” – can provide food security for communities.

And they can be a boon for farmers: once chestnut trees mature, they can produce 50 to 100lb of nuts per tree annually, retailing from $3 to $16 per pound. Planting one, Judd said, means “you’ve got a real valuable, storable, nutrient-rich food you can rely on annually”.

Judd, who organizes his efforts through the non-profit SilvoCulture, which he helps to run, is not alone in his enthusiasm for chestnuts. His project is part of a surge of interest among food activists, academics and farmers in using nut trees to replace large-scale forms of agriculture and food sources, which dominate billions of acres of land globally and produce 11% of US greenhouse gas emissions.

Nut trees, on the other hand, are easy to maintain once established and boast all the same benefits as other trees: they sequester carbon, stabilize and retain topsoil, buffer against flooding and other extreme weather events, and provide a habitat for wildlife.

“If we were to think about how to radically change agriculture, one of the ways we would do that is to eliminate tillage agriculture by planting trees that do the same function,” said Eliza Greenman, a germplasm specialist at the Savanna Institute, a non-profit that promotes planting trees on farmland in the midwest.

253 notes

·

View notes