Text

intimate starters

''come here.''

''stay with me.''

''i want to show you something.''

''i love you.''

''can you hold me?''

''i don't want to be alone.''

''i'm here for you.''

''stay tonight.''

''come closer.''

''why don't you come here for a second?''

''i wanted to apologize.''

''thank you for taking care of me.''

''i really like you.''

''is this your first time?''

''trust me.''

''let's stay here for a while.''

''come to bed.''

''it's just the two of us.''

''touch me.''

''i feel safe here.''

''what is love to you?''

''could you bring me [something]?''

''i need your help.''

''come with me.''

''you don't have to pretend with me.''

''i wanted to thank you.''

''i need a hug.''

''call me when you get home.''

''kiss me.''

''you're cute.''

''it hurts when you're not around.''

''i miss you.''

''be one with me.''

5K notes

·

View notes

Photo

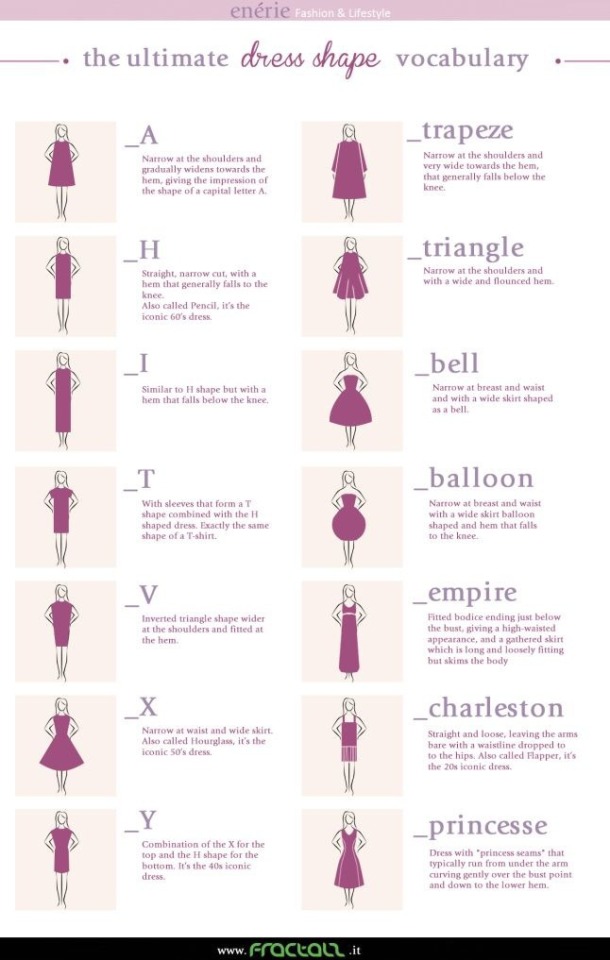

Right. Here is it everything you ever wanted to know about fashion cuts, trends, style, all in one post.

Every example of a trend that existed is list in the above post. So get to know your styles, perfect your image and enjoy mixing trends and different eras together. 😍👌👌

189K notes

·

View notes

Link

Grammar snobs love to tell anyone who will listen: You should NEVER end a sentence with a preposition! Luckily for those poor, persecuted prepositions, that just isn’t true. Here are a few preposition guidelines:

Don’t end a sentence with a preposition

1) In formal writing:

(Casual) Which journal was your article published in?

(Formal) In which journal was your article published?

It’s not an error to end a sentence with a preposition, but it is a little less formal. In emails, text messages, and notes to friends, it’s perfectly fine. But if you’re writing a research paper or submitting a business proposal and you want to sound very formal, avoid ending sentences with prepositions.

2) If something is missing:

(Incorrect) He walked down the street at a brisk pace, with his waistcoat buttoned against the cold and a jaunty top hat perched atop.

The preposition atop is missing an object all together. Let’s try that again:

(Correct) He walked down the street at a brisk pace, with his waistcoat buttoned against the cold and a jaunty top hat perched atop his stately head.

It’s ok to end a sentence with a preposition

1) In informal writing or conversation:

(Correct) To whom should I give a high five?

(Correct) Who should I give a high five to?

Unless you’re a time traveler from another era, you’ll probably use the second sentence when speaking. Informal language is generally accepted in conversation and will likely allow your conversation to flow more smoothly since your friends won’t be distracted by your perfectly precise sentence construction.

2 If the preposition is part of an informal phrase:

(Correct) Five excited puppies are almost too many to put up with.

Also correct:

(Correct) A good plate of spaghetti should not be so hard to come by.

Both ‘put up with’ and ‘hard to come by’ are commonly accepted informal phrases, and it’s OK to end sentences with them. Note, however, that you should avoid these phrases in formal writing.

2 notes

·

View notes

Link

We’ve got rules and standards for everything we include in our novels—how to start those novels, how to increase tension, how to introduce characters, how to format, what to include in dialogue, how to punctuate dialogue, what to exclude from the first chapter. And we have rules for numbers. Or maybe we should call all these rules conventions.

This article covers a few common specifics of using numbers and numerals in fiction. I’m just going to list the rules here, without much explanation, laying out those that you’ll typically make use of in a novel. Keep in mind that there are always exceptions. For the most part, you’ll want to stick to the standards to make the read smooth and easy for the reader and create consistency within the manuscript.

Yet we’re talking fiction here, not a treatise or dissertation or scientific finding. You have choices. And style choices sometimes get to stomp all over the rules. If you want to flout the rules, do so for a reason and do so consistently every time that same reason is applicable in the manuscript.

For a comprehensive list of the rules concerning numbers, check out the Chicago Manual of Style or another style guide.

______________________

General Rules

__ Spell out numbers from zero through one hundred. You could argue for zero through nine, as is recommended for AP style, but do note that the recommendations in the Associated Press Stylebook are primarily for newspaper and magazine writing. Some rules are different for fiction.

You could also make a style choice to spell out almost all numbers, even if that conflicts with this and other rules.

Use numerals for most numbers beyond one hundred. While this is the standard, there are definitely exceptions to this one.

The witch offered Snow White one crisp, dewy apple.

Bobby Sue sang thirty-two songs before her voice gave out.

The rock-a-thon lasted for just over 113 hours.

The witch offered Snow White 1 crisp, dewy apple. Incorrect

__ Spell out these same numbers (0-100) even if they’re followed by hundred or thousand. (Your characters may have reason to say or think all manner of odd numbers, so yes, zero thousand might come up, even though this isn’t a common usage in our 3-D lives.)

The forces at Wilmington were bolstered by the arrival of ten thousand fresh soldiers.

The knight had died four hundred years earlier.

But—The knight had died 418 years earlier.

“How many thousands of lies have you told?”

“I’ve told zero thousand, you fool.”

__ Spell out ordinal numbers through one hundred as well—even for military units and street names. Ordinal numbers are often used to show relationship and rank.

We’d write the Eighty-second Airborne Division but the 101st Airborne Division. (Newspapers and military publications may have different conventions.)

A restaurant would be on Fifth Avenue, not 5th Avenue. Or the restaurant is on 129th Street, not One hundred and twenty-ninth Street.

A quick guide to ordinals—

no ordinal for zero twentieth

first twenty-first

second twenty-second

third and so on . . .

fourth

fifth*

sixth thirtieth (thirty-first, thirty-second, and so on)

seventh fortieth

eighth fiftieth

ninth sixtieth

tenth seventieth

eleventh eightieth

twelfth ninetieth

thirteenth

fourteenth one hundredth

fifteenth* one thousandth

sixteenth one millionth

seventeenth

eighteenth

nineteenth

The only odd ordinals are those using fives—fifth and fifteenth. Note the letter D in both hundredth and thousandth.

__ Use full-size letters, not superscript, to mark ordinal numbers (st, nd, rd, th) written as numerals.

__ Use first, second, third and so on rather than firstly, secondly, thirdly unless your character would use this odd construction as part of her style.

__ Spell out numbers that start a sentence. If spelling creates something awkward, rewrite.

One hundred and fifteen [not 115] waiters applied for the job.

__ Hyphenate compound numbers from twenty-one to ninety-nine. Do this when the number is used alone and when used in combination with other numbers.

Louise owned forty-one cars.

“I heard she owned one hundred and thirty-five diamond rings.”

__ For an easier read, when numbers are written side by side, write one as a numeral and the other as a word.

He made 5 one-hundred-pound cakes.

We lashed 3 six-foot ladders together.

__ Spell out simple fractions and hyphenate them.

He took only one-half of yesterday’s vote.

He needed a two-thirds majority to win the election.

__ For the most part, treat large numbers, made large by being paired with the words million, billion, and so on, just as you would other numbers.

Some nine [not greater than one hundred, so spelled out] million years ago, the inhabitants of Ekron migrated to our solar system.

The family had collected the pennies, 433 [greater than one hundred] million of them, over eighty years.

But for large numbers with decimals, even if the number is less than 101, use the numeral version.

The team needed 10.5 million signatures for their petition.

Yet since we want to hear the words, you could just as easily write—

The team needed ten and a half million signatures for their petition.

This last example works both for narration and dialogue. But for dialogue you could also write—

“The team needed ten point five million.”

__ Use words rather than symbols and abbreviations in dialogue and in most narrative. Symbols are a visual representation, but characters need to think and speak the words.

Use the words rather than the symbols for degree (°) and percent (%) and number (#), both in dialogue and narrative. Use the word dollar rather than the dollar sign ($) in dialogue. Do not abbreviate the words pounds or ounces, feet or inches (or yards), hours or minutes or seconds, or miles per hour (or similar words) in dialogue or narrative.

An exception might include something like stretches of text where you note the changing speeds of a car but don’t want to repeat miles per hour again and again. Your use of mph becomes a style choice.

You might find other exceptions in headers and chapter titles. You can, of course, use symbols in titles and headers if you want to. For example, in geo-political thrillers, stories that jump all over the world and back again, headers might show longitude and latitude and the degree symbol would come in handy.

If you do include full compass coordinates in the narrative, using numerals and the symbols for degrees, minutes, and seconds might be the best choice in terms of clarity and ease of reading.

“But I don’t have a million dollars.”

“Nobody gave a hundred percent.”

“The baby weighed seven pounds eleven ounces.”

“It’s fourteen degrees out there!”

The # of crimes he’d committed kept rising. Incorrect

The chasm looked at least 40 ft. wide. Incorrect

The roadster crept along at no more than 28 mph. Incorrect

Note: You’re writing fiction. Think flow in the visuals as well as in the words. What will make sense to the reader and keep him from tripping over your style choices?

Time

__ Use numerals when you include a.m. and p.m., but you don’t have to use a.m. and p.m.

It was 5:43 a.m. when he got me out of bed. Correct

It was five forty-three a.m. Incorrect

__ Use lower case letters with periods or small caps without periods for a.m. and p.m.

__ Include a space between the numbers and a.m. or p.m., but no space within a.m. or p.m.

__ Spell out numbers when you include o’clock.

But he did wait until after five o’clock to call.

__ Use numerals to emphasize exact times, except in dialogue.

She pointed out that it was still 5:43 in the morning.

“It’s four forty-three.” She looked out into the darkness. “In the morning!”

The robbery took place at 2:22 a.m.

__ Spell out words for the hour, quarter, and half hours.

The hall clock was wrong; it showed eight thirty. No, it showed eight forty-five.

__ Do not use a hyphen to join hours and minutes. I have seen advice on several Internet sites that says you do use a hyphen in such cases, except when the rest of the number is already hyphenated. So they’d have you write two-twenty but two twenty-five. This doesn’t make much sense, although there may be a style guide out there recommending such punctuation (and may provide a valid reason for it). The Chicago Manual of Style, however, does not use a hyphen (see 9.38 in the sixteenth edition). Their example is “We will resume at ten thirty.”

It was four-forty-five. Incorrect

It was four forty-five. Correct

The bomb went off at eleven-thirty. Incorrect

The bomb went off at eleven thirty. Correct

__ While we normally would never use both o’clock and a.m. or p.m. and typically don’t use o’clock with anything other than the hour, fiction has needs other writing doesn’t. The following might very well come out of a character’s mouth or thoughts—

It was five o’clock in the a.m.

“Mommy, it it four thirty o’clock yet?

Dates

__ Dates can be written a number of ways. The twenty-fifth of December, December 25, December 25, 2015, or the twenty-fifth are all valid ways of referring to the same day.

December 25th and December 25th, 2015 are incorrect. Do not use ordinal numbers for dates that include month, or month and year, written in this format. You can, however, write the twenty-fifth of December.

December 25 and December 25, 2015 would both be prounounced as the ordinal, even though the th is not written.

The exception is in dialogue.

“Your kids can’t wait for December twenty-fifth.”

__ Do not use a hyphen (actually, this in an en dash) for a range of dates that begins with the words from or between. (This rule is true of all numbers, not just dates, arranged this way.) Use the words to, through, or until with from, and and with between.

He planned to be out of town from August 15-September 5. Incorrect.

He planned to be out of town from August 15 to September 5. Correct

He planned to be out of town between August 15-September 5. Incorrect

He planned to be out of town between August 15 and September 5. Correct

He planned to be out of town August 15-September 5. Correct

__ Decades can be written as words or numbers (four- or two-digit years). Unless it’s in reference to a named era or age—the Roaring Twenties—do not capitalize the decade.

The cars from the thirties are more than classics.

Cars of the 1930s were my dad’s favorites.

The teacher played songs from the ’60s and ’70s to get the crowd in the right mood. (The punctuation is an apostrophe, not an opening quotation mark.)

__ There is no apostrophe between the year and the letter S except for a possessive.

The doctor gave up smoking back in the 1980’s. Incorrect

The doctor gave up smoking back in the 1980s. Correct

The doctor gave up smoking back in the ’80’s. Incorrect

The doctor gave up smoking back in the ’80s. Correct

BUT—She was the fifties’ [also the ’50s’] most glamorous star.

An earlier example was incorrect—She was decked out in cute 1950’s clothes, but the haircut was atrocious. Incorrect

__ Spell out century references.

He wanted to know if it happened in the eighteenth or the nineteenth century. When the guide reminded him it was the seventeen hundreds, he was even more confused.

__ Adding mid to date terms can be confusing. The general rule is that mid, as a prefix, does not get a hyphen. So midyear, midcentury, midterm, midmonth, and midthirties are all correct. (The same rules apply for other prefixes, such as pre or post, that can be used with date words.)

There are, however, exceptions—

Include a hyphen before a capital letter. Thus, mid-October.

Include a hyphen before a numeral. Thus, mid-1880s.

Include a hyphen before compounds (hyphenated or open). Thus, mid-nineteenth century and mid-fourteenth-century lore.

Note: The Chicago Manual of Style has a wonderful and comprehensive section on hyphenating words. I recommend it without reservation.

Dialogue

__ Spell out numbers in dialogue. When a character speaks, the reader should hear what he says. And although a traditional rule tells us not to use and with whole numbers that are spelled out, keep your character in mind. Many people add the and in both words and thoughts. Once again, the rules are different for fiction.

“I collect candlesticks. At last count I had more than a hundred and forty.”

“At last count I had more than one forty.”

“She gave her all, 24/7.” Incorrect

“She gave her all, twenty-four seven.” Correct

One exception to this rule is four-digit years. You can spell out years, and you’d definitely want to if your character has an unusual pronunciation of them. But you could use numerals.

“He told me the property passed out of the family in 1942.”

“I thought it was fifty-two?”

A second exception would be for a confusing number or a long series of numbers. Again, if you want readers to hear the character saying the number, spell it out. Even common numbers might be spoken differently. One character might say eleven hundred dollars while another says one thousand one hundred dollars.

If you have to include a full telephone number—because something about the digits is vital—use numerals, even in dialogue. (But if you want to emphasize the way the numbers are spoken, spell out the numbers.)

You’d use numerals rather than words because writing seven or ten words for the numbers would be cumbersome. But most of the time there is no reason to write out a full phone number.

__ Write product and brand names and titles as they are spelled, even if they contain numbers—7-Eleven, Super 8 hotels, 7UP.

Heights

__ Heights can be written in a variety of ways.

He was six feet two inches tall.

He was six feet two.

He was six foot two.

He was six two.

He was six-two. (a recommendation from some sources, although not one I’d make)

Money

__ Do not hyphenate dollar amounts except for the numbers between twenty-one and ninety-nine that require them. Don’t use a hyphen between the number and the word dollars (except as noted below). Note the absence of commas.

two dollars

twenty-two dollars

two hundred dollars

two hundred twenty-two dollars or two hundred and twenty-two dollars

two thousand two hundred and two dollars

But—

a two-dollar bill

a twenty-dollar fine

a two-hundred-dollar fine

a two-hundred-and-twenty-two-dollar fine

Punctuation

__ No commas or hyphens between hours and minutes, feet and inches, pounds and ounces, and dollars and cents that are spelled out. If the meaning is unclear, rewrite.

Ben promised to be there at four thirty, but it was six twenty when he pulled into the driveway.

At seven feet three inches, he was the shortest of the Marchesa giants.

The piece of salmon weighed one pound eleven ounces, but they charged the rude customer the price for three pounds.

He owed his boss forty-two fifty.

He owed his boss forty-two dollars and fifty cents.

__ Use hyphens for compound adjectives containing numbers the same way other compound are created. They are almost always hyphenated as an adjective before the noun. Age terms, both nouns and adjectives used before nouns, are hyphenated. (Noun forms of compound words paired with the word old are hyphenated, as are adjectives paired with old that are placed before nouns.)

A two-inch hole in the street became a six-by-six-foot crater.

My two-year-old loves puppies.

My son has a two-year-old puppy.

But—My puppy is two years old.

__ No hyphen between numbers and percent.

The drink was only 60 percent beer. The rest was water. Correct

The drink was 20-percent beer. Incorrect

__ For multiple hyphenated numbers sharing a noun, include a hyphen and a space after the first number and hyphenate the last as usual.

Our Johnny couldn’t wait to tell us about the ten- and twenty-foot-tall monsters in the yard.

His sister shared details about the two- and three-headed versions that lived under her bed.

__ For the words half and quarter, use the hyphen for adjectives but not for noun forms. (Some words with half are closed compounds—halfway, halfwit—so check the dictionary.)

“Join me in a quarter hour or join me in a half hour; it’s your choice.”

Join me half an hour from now.

The half-price items were poorly made.

__ For compound words made with odd, always use a hyphen.

Thirty-odd hours later, my son finally returned home.

He’d saved some 150-odd comic books.

__ For numerals greater than 1,000, include commas after every three digits from the right (for American English). For fiction, it’s likely you’ll often round off these numbers and/or write the numbers as words, but the rule is good to know.

1,000

10,525

10,525.78

953,098,099

__ For dollar amounts written as numerals, use the period to separate dollars and cents, and include the dollar sign. But you could spell out the amount, especially if you’re rounding the number.

He needed $159.75 for the bar tab.

He needed a hundred and sixty dollars for the bar tab.

You may have been advised to always write one hundred rather than a hundred, but for fiction, we want to reflect a character’s words and style.

__ Do not add a period if a.m. or p.m. comes at the end of a sentence. Do use a comma midsentence if that is necessary.

The fire alarm was pulled at 11:58 a.m.. Incorrect

The fire alarm was pulled at 11:58 a.m. Correct

The alarm was pulled at 11:58 a.m., just before lunch. Correct

Weapons and Guns

For the most part, stick with the rules governing numbers when you write about weapons. A publisher’s style guide may overrule your choices, but you’ll want consistency either way. Keep in mind your speaker’s or viewpoint character’s familiarity with weapons. One character might know every detail about a weapon while another calls every weapon a gun.

Use only the necessary detail. For example, in fiction you might not often have cause to write The AH-64D Apache Longbow was the team’s first choice. Instead, you might write, The Longbow was the the team’s first choice. Yet before this moment in the story, you might have needed to list the equipment available to them, writing out the full name of several helicopters.

__ In both narrative and dialogue, if you use the name of the gun or ammo, spell it as the manufacturer does, including numerals and capital letters. Do the same for military weapons and tanks. Spell out the word caliber.

If you don’t use the full name, still capitalize brands and manufacturers. The designation mm is accepted in narrative.

He eyed the .357 Magnum in the loser’s shaky hand.

Anderson’s Colt .38 was under his pillow, two rooms away.

Both the Browning 9mm, his favorite, and his stacked salami sub, another favorite, were destroyed by the car crusher.

I knew she lied when she told me the M1 Abrams had been named after her father; she was much too young.

__ In dialogue, if the character is saying a variation of the name but not the name itself, you have options. Use words when doing so isn’t convoluted or cumbersome or unclear.

“Dirty Harry used a forty-four, not a three fifty-seven.”

“How would I know? Thirty aught six, thirty aught seven. What’s the difference anyway?”

Deke back-whistled through his teeth. “You’ve never even picked up a rifle, have you?”

“What was it? A nine millimeter?”

“A Glock 17 Compensated. New and shiny.”

Contradictory Rules

If you’ve got rules that conflict, you have a few options.

Rewrite.

Choose the option that gives clarity to the reader.

Remember that in fiction, words can almost always be substituted for numerals. When in doubt, write it out. Yeah, corny and elementary, I know. But it’s advice that’s easy to remember.

______________________

Keep in mind that characters don’t all speak or think the same way, with the same words. Let your choices reflect your characters and not only the rules. That is, sometimes the rules are less important than the way the characters express themselves.

As an example, the rules (for American English, not British English) tell us not to write years in this manner—fourteen hundred and ninety-two, with the and. But your character just may think or say a date with the and. Be true to his voice and style.

And be consistent. Create a style sheet and stick with it. Know what choice you made for your numbers in chapter six and do the same in chapter fifteen.

Fiction is different from other writing styles. We use words rather than symbols, abbreviations, and images. If you’re unsure, spell out the numbers. Put it in words.

~~~

LG’s Note: These are just conventions, not “must do’s”. I’m only posting these as guidance for myself as someone who prefers writing out numerals or anyone interested in seeing the explicit difference between the two styles - numerical and textual - laid out cleanly.

3 notes

·

View notes

Link

Since this is my 100th episode, it seems like a fitting time to talk about how to use numbers in sentences.

[Note: There are many exceptions to the rules about how to write numbers. These tips will point you in the right direction, but if you are serious about understanding all the rules, you need to buy a style guide such as The Chicago Manual of Style or The Associated Press Stylebook.]

Whether to use a numeral or to spell out a number as a word is a matter of style. For general writing, most guides agree that you should use words for the numbers one through nine, but for larger numbers the rules vary wildly from style guide to style guide. Some say to use words for the numbers one to one hundred, one to ten, any word that can be written with one or two words, and so on. Typically, people who write business or technical documents are more likely to use numerals liberally, whereas people who write less technical documents are more likely to write out the words for numbers. If someone handles numbers a different way than you do, they're probably using a different style guide, so the best advice I can give you is to pick a style and stick with it when it makes sense. (Since I used to be a technical writer, I write out the words for numbers one through nine, and use numerals for most other numbers.)

Fortunately, some rules about writing numbers are more universally agreed upon than the general rules I just told you about.

Normalization

Let's say you’re writing about snail development--a technical subject--and you've decided on a style that says you use words for the numbers one through nine and numerals for anything bigger. If you come upon a case where you have two related numbers in the same sentence, you should write them both as numerals if you would write one as a numeral. The idea is to write them the same way when they are in the same sentence. So even though you would normally write out the word "one" if you were writing,

"The snail advanced one inch,"

if you added a number over nine to that sentence, then you would use numerals instead of words when you write,

"The snail advanced 1 inch on the first day and 12 inches on the second day."

(You'd write both 1 and 12 as a numeral.) Most style guides agree that you should break your general rule in cases like that, when doing so would make your document more internally consistent.

Web Bonus: Normalization

If you have a third number that would normally be written as a word in the example sentence above, and if it isn't referring to inches, you would still write it out as a word. You only normalize to numerals if the numbers are referring to the same thing:

The five researchers noted that the snail advanced 1 inch on the first day and 12 inches on the second day.

Numbers Next to Each Other

Here's another one most people seem to agree on: When you are writing two numbers right next to each other, you should use words for one of them and a numeral for the other because that makes it a lot easier to read. For example, if you write,

"We tested 52 twelve-inch snails,"

you should write the number 52, but spell out twelve (or vice versa).

Beginning of a Sentence

When you put a number at the beginning of a sentence, most sources recommend writing out the words. If the number would be ridiculously long if you wrote out the words, you should rephrase the sentence so the number doesn't come at the beginning. For example, this sentence would be hard to read if you wrote out the number:

Twelve thousand eight hundred forty-two people attended the parade.

It's better to rephrase the sentence to read something like this:

The parade was attended by 12,842 people.

The second sentence uses passive voice, which I generally discourage, but passive voice is better than writing out a humongous number and taking the risk that your readers' brains will be numb by the time they get to the verb.

Some style guides make an exception to allow you to use the numeral when you're putting a year at the beginning of a sentence, but others recommend that you use words even in the case of years.

Dialogue

OK, here's a final rule that's pretty straightforward. If you're writing dialogue, for example quoting someone in a magazine article or writing a conversation in fiction, spell out all the numbers. Of course, even here The Chicago Manual of Style notes that you should use numerals "if [words] begin to look silly." But the idea is that you should lean toward using words in dialogue.

There is so much more to say about numbers that I'm going to make this a two-part series. Next week I'll cover rules about writing percents, decimals, and numbers over a million.

~~~

LG’s Note: I prefer writing out numbers in text instead of numerals, but I find that time presents a problem. Anyone have any ideas?

2 notes

·

View notes

Link

Here are some adjectives for scars:

1) In alphabetical order separate words that can be combined:

Abdominal

Aboriginal

Almost

Already

Amazing

Ancient

Angry

Angular

Artificial

Attractive

Awful

Back

Bald

Bare

Barren

Beautiful

Best

Big

Bitter

Black

Bleak

Bloody

Blue

Bluish

Bright

Brilliant

Broad

Broader

Brown

Brownish

Brutal

Burned-out

Bygone

Caesarean

Cancerous

Capricious

Certain

Characteristic

Characteristically

Charred

Circular

Clean

Coal

Coal-black

Coloured

Complete

Concave

Concrete

Conspicuous

Contiguous

Continuous

Corrugated

Countless

Crimson

Criss-crossed

Crooked

Cruel

Crusty

Crystal

Curious

Curved

Cute

Dangerous

Dark

Dark-blue

Dark-brown

Dead

Deep

Deepest

Deeply

Deep-seated

Definitely

Deliberate

Depressed

Desperate

Diagonal

Diamond-shaped

Dim

Distinctive

Double

Doubtless

Dramatic

Dreadful

Drunk

Dry

Dull

Dusty

Elegant

Elliptical

Emerald

Emotional

Enough

Entirely

Equally

Evil

Extensive

External

Extra

Facial

Faint

Fainter

Fake

Familiar

Famous

Fat

Fearful

Fearsome

Few

Ficial

Fierce

Fine

Finer

Five-inch

Flaming

Flat

Fleshy

Flexible

Florid

Foul

Four-inch

Frail

Frequent

Fresh

Frightful

Frontal

Funny

Furrowed

Garish

Genuine

German

Ghastly

Gigantic

Glandular

Glassy

Glorious

Glossy

Gnarly

Good

Granular

Grassy

Grave

Gray

Great

Green

Greenish

Grey

Grievous

Grim

Grisly

Gross

Grotesque

Gruesome

Hairless

Half-forgotten

Half-inch

Half-melted

Hard

Harden--emotional

Healthy

Heavy

Heroic

Hideous

High

Hind

Honeycombed

Honorable

Horizontal

Horrendous

Horrible

Horrid

Horrific

Horrifying

Hot

Huge

Identical

Immense

Immovable

Impressive

Inconsequential

Indelible

Indistinct

Indistinguishable

Inexplicable

Inflamed

Inflexible

Infrared

Ingrained

Inner

Innocuous

Innumerable

Interesting

Internal

Intriguing

Inverted

Invisible

Irregular

Itchy

Jagged

Jaggedly

Just

Keloidal

Knotted

Knotty

Large

Larger

Lateral

Lazy

Leathery

Legendary

Less

Life-long

Linear

Little

Livid

Long

Longest

Longitudinal

Low

L-shaped

Lumpy

Malignant

Many

Massive

Mauve

Medical

Mental

Microscopic

Mighty

Mile-long

Minimal

Molten

More

Mostly

Moth-like

Much

Muddy

Multiple

Myriad

Mysterious

Naked

Narrow

Nastier

Nasty

Natural

Neat

New

Newest

Next

Nice

Nine-year-old

Non-existent

Noticeable

Now

Numb

Numerous

Obscene

Obvious

Occasional

Ochre

Odd

Often

Old

Older

Ominous

Open

Ordinary

Ornamental

Other

Outer

Oval

Painful

Painless

Pale

Papery

Parallel

Peculiar

Perceptible

Perfect

Permanent

Perpendicular

Perpetual

Petty

Physical

Pink

Pinkish-white

Placental

Plain

Possible

Post-operative

Powdery

Precisely

Present

Prominent

Psychic

Psychological

Puffy

Purple

Purple-black

Pyramid-shaped

Queer

Quite

Ragged

Rainbow-hued

Rakish

Random

Rather

Raw

Razor-thin

Readily

Real

Recent

Re-created

Red

Reddish

Regular

Remarkable

Repulsive

Rhomboidal

Right-handed

Ringed

Ritual

Rocky

Rough

Roughly

R-shaped

Rubbery

Rugged

Sad

Same

Sandy

Satisfyingly

Savage

Scabrous

Scarcely

Scarlet

Scarred

Seamy

Seemingly

Self-inflicted

Semicircular

Sensitive

Serpentine

Several

Shadowy

Shallow

Sharp

Shiny

Shocking

Short

Sickle

Significant

Silvery

Simple

Simply

Single

Six-inch

Slick

Slight

Slim

Small

Smaller

Smooth

Sonic

Sooty

Spectacular

Spidery

Spiral

Startling

Steep

Stiff

Still

Straight

Strange

Such

Suitably

Sullen

Sundry

Sunken

Super

Surgical

Swollen

Symmetrical

Tan

Taut

Telltale

Tell-tale

Temporary

Tense

Terrible

Thick

Thickest

Thin

Thinner

Three-cornered

Threefold

Three-foot

Three-inch

Three-month-old

Three-week-old

Thy

Tidy

Tight

Tiny

Tolerably

Tough

Transversal

Transverse

Traumatic

Triangular

Tribal

Trifling

Triple

Troubling

Truly

Tubercular

Twin

Twisty

Two-inch

Ugly

Umbilical

Undeniable

Uneven

Unhealed

Unimportant

Unmistakable

Unpleasantly

Unseen

Unsettling

Unstructured

Untouched

Usual

Usually

Vaccination

Vaguely

Variously

Vast

Vermilion

Vertical

Vicious

Vile

Visible

Vivid

V-shaped

Warm

Weird

Wet

White

Whitened

Whitish

Whole

Wicked

Wide

Withered

Worst

Wrinkled

Yellow

2) Copied directly form the website with minimal formatting:

crooked pink, glossy, whitened, doubtless psychological, physical and doubtless psychological, pink, three-cornered, ragged, inflamed, fresh jagged, thickest worst, mile-long parallel, rubbery false, invisible, permanent, older surgical, thick and jagged, tidy but visible, terrible furrowed, old l-shaped, multiple scarlet, bald, spiral, livid, diagonal, large transversal, dreadful threefold, already pink and shiny, pale triangular, smaller but broader, strange, regular, scarred, tiny, ragged, attractive, linear, longitudinal, crooked, cruel, recent placental, pale triangular smaller but broader strange, regular scarred, tiny ragged, attractive linear, longitudinal crooked, cruel recent placental prominent umbilical red, diamond-shaped numerous furrowed tiny innocuous neat and painless obvious, dramatic tight, diagonal right-handed, numerous parallel, self-inflicted gigantic burned-out thick recent razor-thin, parallel still inflamed startling and massive reddish, ragged jaggedly yellow satisfyingly horrific jagged five-inch horrible angry brilliant flaming fearsome jagged still hard and hot characteristically depressed crimson seamy contiguous dangerous slight but long jagged, red fresh, jagged nasty pink long, livid unmistakable and honorable big whitish funny, triangular fresh and livid best, terrible long and livid sunken, livid great, powdery big caesarean two-inch linear deep l-shaped two-inch jagged new, livid pale, jagged pink, flat telltale surgical faint, ancient vicious, red vivid diagonal hideous, angry itchy old brown familiar scabrous honeycombed newest permanent jagged, ancient concave, semicircular noticeable and remarkable artificial prominent curious, livid deep-seated, small jagged, glorious complete and little ugly frontal red withered flexible, bluish smooth or keloidal triangular, purple --surely honorable hard and immovable slight, whitish reddish, slight deep criss-crossed concave triangular broad, fearful unhealed umbilical unhealed red great capricious savage and mysterious grotesque brown several visible deep, v-shaped dramatic facial old, tiny same traumatic new, jagged broad, livid long brutal fine, parallel great, livid keloidal hideous facial shocking red great livid five-inch pink knotted, crusty cancerous grey wide terrible horrendous, jagged visible emotional big, gruesome perceptible horizontal ornamental spiral still red and angry red surgical new, wrinkled ugly three-inch florid, white large and distinctive ragged, three-inch jagged facial warm ragged deliberate tribal taut pink gnarly white vicious ritual noticeable surgical already pink queer triangular straight and pale jagged distinctive thin, four-inch neat livid thin facial large, pyramid-shaped old post-operative unpleasantly tense hideous horizontal deep, horrifying white, jagged visible three-inch old tubercular hind mental still red and prominent half-inch pink thin, half-inch parallel bluish smooth, livid famous lateral rather jagged malignant crimson forearms crystal pale, elliptical faint jagged raw facial old, whitened tiny but visible wide, corrugated familiar ritual symmetrical but equally honorable intriguing diagonal bald, evil indelible emotional brutal, unhealed new, horrid old smooth cruel semicircular definitely emotional lazy, bitter aboriginal ritual cute psychological super ficial ragged, nine-year-old myriad honorable diagonal facial ragged, pink drunk, red shallow pink frightful and impressive white and knotted vaguely itchy perfect surgical large and spectacular suitably large and spectacular lumpy surgical vile purple-black old, outer faint, rakish red, uneven shiny sickle smaller fainter grisly facial triple ringed lumpy new three-foot, jagged wicked pink bare, concave other half-melted charred, glassy vicious sonic vicious, hot white and inconsequential random, circular ‘‘tribal black abdominal bygone medical vast, coal-black unhealed mental long, life-long faint surgical horrific facial bright and livid livid, angry raw and unhealed hideous livid large and perpetual three-cornered, jagged cruel, slim jagged, bluish hideous, red frequent and deep awful, livid tiny v-shaped angry, wrinkled rough, circular long and conspicuous depressed circular older, livid gray diagonal prominent triangular long ingrained parallel white livid white prominent facial tiny, old deep livid own facial hard circular hideous, repulsive long livid red, smooth raw brown old crystal fresh pink sad, naked livid, red black, serpentine awful facial shiny circular bright infrared horrible purple still livid peculiar v-shaped deep and hideous often ancient deep and jagged ugly raw furrowed deep broad livid deep and livid circular umbilical deep vermilion old, small jagged white irregular pink thick triangular deep furrowed great furrowed deep and indelible plain bald deep and crooked slick, shiny ugly purple distinctive facial quite deep few attractive ugly pink small, microscopic more livid red, granular jagged old ugly facial long and ragged weird facial old, huge small, undeniable dark coal long and jagged swollen and bloody slick, pink wide and angry long surgical hard, inflexible small, semicircular semicircular white finer, thinner elegant facial inverted v-shaped irregular, jagged fine horizontal several garish white facial hard, numb harden--emotional angry thin deep ritual pink, puffy also curved larger, nastier vivid, shocking unsettling white dreadful surgical little triple deep surgical jagged, vertical neat diamond-shaped myriad fresh great burned-out awful jagged lumpy, pink present surgical angry, jagged myriad psychic strange straight countless pale extra facial shiny, knotted untouched such frightful, hideous jagged crimson curious dark-blue old faint curious ragged entirely legendary less troubling mighty red red triangular deep, white reddish blue old, pale small, uneven several shiny livid pink white jagged small depressed brutal white deeply depressed wide purple several faint long jagged immense long new, pink deep, vicious enough psychological thick, pink clean, broad minimal old jagged knotted pink peculiar and vivid frightful red grave great parallel perpendicular wide and ragged long, jagged thick, jagged now non-existent old and recent nice ordinary brutal german few pink dreadful facial old, wide deep, jagged wide, jagged huge fresh long facial pink, leathery own honorable red new long, obscene deep horizontal few facial fierce, raw naked, red brown and greenish deep, crooked still internal fine crystal lumpy purple obvious long flat, brownish old, jagged fresh, livid irregular, oval r-shaped old diagonal flat, slick taut, shiny simple, knotted sad, white white three-cornered three-cornered white numerous grey tiny lateral foul white long, whitish big silvery jagged red faint old flat shiny triangular white long vivid smooth, hairless tiny, ancient black, irregular new facial knotted white huge, circular livid short, pink tiny three-cornered telltale little more smooth characteristic facial massive pink frail new small but distinctive ugly crimson _ornamental broad flaming grim, naked terrible purple more indelible deep parallel deep ragged great, angry few honorable smooth, blue fresh, shiny many emotional fresh, scarlet vast and strange long, wrinkled conspicuous oval thin, livid longest, deepest horrible facial raw heavy distinctive jagged long, fresh long twisty pink, shiny visible facial still red and swollen small and recent old knotty myriad faint rough, pale usual bloody single honorable broad, ragged curved, white deep, livid curious jagged hard and knotted unhealed dry black still faint old, long long angry thin ragged twin red long, diagonal muddy yellow dark and jagged long, ragged long ancient hideous crimson permanent red several honorable fresh, pink shallow black characteristic white scarlet and black few funny deep angry placental several facial little, dim vivid white stiff, old ugly wrinkled pale new small twin livid crimson back physical deep facial other facial pale, deep several livid wide bloody pink shiny small but noticeable fine surgical usually pink suitably large new, inner spidery white broad, big huge livid deep, flaming long dark-brown much irregular red, ragged long pink many and beautiful new pale several fierce good, tough deep and impressive thin pink thick stiff long, triangular angry red ugly jagged old, faint small, fresh continuous deep large facial pale vertical certain tribal painful emotional thin, jagged six-inch long pale and livid faint parallel deep, nasty recent and glorious strange, jagged vaccinal grey and pink faint pink large muddy extensive sandy remarkable large deep, rugged long whitish broad lateral own significant own genuine old, white small, sensitive vast emerald green and ochre simply dead more facial permanent emotional certain facial old, thick wide, purple deep emotional horrible red many ragged small, old pinkish-white long, knotted more fake red, angry long, pink white, small small glandular ghastly blue own trifling ugly red thick, red black, jagged facial tiny grey jagged permanent external extensive facial thin jagged recent surgical ugly bald fine, heroic molten red few tell-tale pale, shiny nasty white great fresh sundry deep deep and fearful black and sullen new pink thin white small bluish vivid red black sooty deep, old few external single neat small parallel fresh, deep faint white l-shaped many visible smooth, shiny dry, healthy three-foot long jagged pink faint mauve own identical faint double pale, old savage red brown barren savage brown more sunken next prominent faint oval huge, bare queer double many hideous roughly circular black, charred long bleak dark circular long vertical thin vertical long, parallel tiny silvery tolerably broad small triangular many honorable short deep still hard other, older wide silvery livid red long concrete dark ominous white hairless faint, tiny long, vivid readily visible sharp pink hard knotted circular blue jagged and irregular knotted red hideous long long transverse dull, yellow huge, ragged deep, irregular swollen red emotional and physical red and pink myriad other little smooth tiny oval now thick bare thy thick, tough numerous black hideous red pink or purple old surgical deep, ancient fine, straight several deep almost unseen new interesting short, jagged small jagged small transverse deep white few visible small angular open old small three-cornered thin, straight few and small tiny, white deep, red several nasty great jagged raw red precisely identical other rocky deep and angry real thin great charred fleshy white several noticeable low curved huge flaming great triangular dreadful red long deep curved white narrow white fresh yellow broad red peculiar black umbilical thin, white many blue large fresh sooty black thick knotted thick, whitish thin, papery straight, fine long, brutal invisible white temporary and permanent ugly white numerous tiny other pale quite visible fat black long, white wide red smooth purple nasty big deep, angry long crooked equally honorable shiny grey shiny pink white horizontal dark uneven deep, cruel old, deep other brutal ragged yellow long reddish steep dark long, angry black, ragged myriad small large, irregular smooth, silvery deep grassy few psychological long v-shaped thin, vertical occasional red long parallel faint pale short pink vivid crimson hideous yellow ragged red raw, red ragged white long white long old vertical white white vertical deep bright long, faint lumpy white long, sandy straight yellow huge jagged three-month-old numerous ancient deep and long new, white sharp, thin bare rocky long, wicked myriad tiny narrow red long ragged small whitish “emotional many inner faint dark still raw thick pink thin red small, triangular small, ragged old thin awful green funny white just faint ancient natural ugly concrete straight vertical odd white small, white many grievous thin fine intriguing little deep, sad large, pale dusty white innumerable old large, jagged long uneven small shadowy long regular few possible indelible many fresh long, horizontal broad, blue deep muddy scarcely visible small straight same funny large, ragged little surgical raw, new three-week-old strange double wide, rough rhomboidal strange, vivid small but perfect long, red long red occasional faint truly amazing several recent emotional livid purple crooked white thin pale still painful deep and desperate high grey fine white thick, white rather significant bright, red small, crooked still red thick vertical whole broad clean, smooth diamond-shaped nasty red slight white long, perfect faint, silvery fresh red broad, red long rough triangular fine, pale small surgical many faint few indistinct smooth red great raw narrow, deep certain unimportant long brown seamy tiny white tough white angry purple wide wet rough, jagged slight red wide, brown large, broad peculiar double surgical ritual furrowed broad, green three-cornered wide, dark few petty five-inch razor-thin single straight almost indistinguishable deep red small white unstructured old half-forgotten self-inflicted rough red pale tan few new re-created long fine impressive little deep vertical puffy red long, cruel black triangular such honorable honorable flat, white mostly white bare red large, red small fine large pale old white diagonal small, circular caesarean criss-crossed rainbow-hued vivid pink deep wet small, faint variously coloured numerous white great oval gross physical transversal ugly brown old circular small pale more invisible small fresh single visible post-operative long, purple long pale few fresh moth-like long diagonal countless new seemingly inexplicable

0 notes

Link

However is a conjunctive adverb (aka adverbial conjunction), so other conjunctive adverbs can fill the same slot depending on the relationship you want to establish between two independent clauses. Conjunctive adverbs can be inserted within a sentence like a regular adjective, they can begin a sentence as a one-word introductory phrase followed by a comma, or they can join two independent clauses together if they appear after a semicolon.

They come in the following flavors, which I quote from Allison D. Smith’s Signs, p. 117:

additive: moreover, furthermore, likewise, finally, additionally, also, incidentally

contrastive: however, nevertheless, in contrast, on the contrary, nonetheless, otherwise, on the other hand, in comparison, conversely, instead

comparative: similarly, likewise

exemplification: for example, for instance

intensification: indeed, moreover, still, certainly

resultative: therefore, thus, consequently, as a result, finally, then, accordingly, hence, subsequently, undoubtedly

temporal: meanwhile, then, next, finally, still, now

0 notes

Link

Language Name Generators

Iconic names come from all over the world, such as Don Quixote, Elizabeth Bennet, and Jean Valjean. If you'd like to venture beyond the scope of your own country for the right name, this random name generator is for you.

Medieval Name Generators

Here lie the original names of the world — as sturdy and worthy today as they were thousands of years ago. If you’re interested in the secrets that the ancient world of names holds, this medieval name generator is for you.

God Name Generators

Long before books came into existence, men and women relied on their ancient gods for guidance. If you, too, would like to look to the universe’s greater powers for help when it comes to a name, this god name generator is for you.

Fantasy Name Generators

For the next J.R.R. Tolkien in the world — or anyone who wants a more fantastical name. If you’d like to ascend into legend alongside characters like Azazel, Bilbo, and Daenerys, this fantasy name generator is for you.

Archetype Name Generators

Heroes. Villains. Sidekicks. Mentors. Oh my! This generator will put a name to the face of the hero or villain that you have in mind. If you’d like a character who lives up to the name, this archetype name generator is for you.

So you want to create good character names?

Stop us if you've been through this before. You get a brilliant story idea, you sit down at your computer, all ready to outline the whole thing out — which is when you realize that you’re missing one very important ingredient: a character name. Needless to say, the right character name can go a long way. It’s why J.K. Rowling scoured phone directories and Charles Dickens paid visits to cemeteries in search of the perfect name. (He derived the now-iconic Ebenezer Scrooge from a tombstone that read, “Ebenezer Lennox Scroggie.”)

Hopefully, this character name generator will be able to help out if you’re stuck. Feel free to wander between each of our name generators. Any combination of names that you score are yours to use. We’d be delighted if you dropped us the success story at [email protected]!

Here are some tips for you to consider while using this random name generator.

Most of our categories are divided into a male name generator and female name generator. However, if you prefer not to be confined by these constraints, feel free to select “Random” to generate even more combinations of names.

Don’t forget the usefulness of nicknames as you’re picking a name from this name generator. Keep in mind alternative shorter names that might ring true to your character. Pip from Charles Dickens’ Great Expectations, for instance, is really Philip Pirrip.

Test the character name on yourself. Look at it on the page. Then try to sound it out loud just to see if it rolls off your tongue. If you can clearly picture your character in both cases, then you just might have a winner on your hands.

And if you’d rather create a character name all by yourself? Great 👍 Head here for a guide on how to come up with character names.

0 notes

Link

I stumbled on this while looking at their name generators, it’’s maybe useful?

0 notes

Link

This name generator will generate 10 random Korean surnames and first names in their Romanized versions and in this order.

The Koreas are two countries in East Asia. South Korea has a population of roughly 52 million (half of whom live in the capital city), while North Korea has an estimated population of about 25 million.

South Korea is an urban focused and technologically advanced country with a strong economy, as well as a high quality of life. North Korea is unfortunately the polar opposite.

As far as names go, the two Koreas share similar names, but South Korea begins to favor English names as well, whereas North Korea sticks to more traditional Korean names instead.

0 notes

Link

How to write dialogue in fiction

Dialogue in the novel: tricks, tools and examples

Speech gives life to stories. It breaks up long pages of action and description.

Getting speech right is an art but, fortunately, there are a few easy rules to follow. Those rules will turn your dialogue from something that might feel static, heavy and unlifelike into something that shines off the page.

Better still, dialogue should be fun to write, so don’t worry if we talk about ‘rules’. We’re not here to kill the fun. We’re here to increase it.

“Ready?” she asked.

“You bet. Let’s dive right in.”

Dialogue rule 1: keep it tight

One of the biggest rules in dialogue is: no spare parts. No unnecessary words. Nothing to excess.

That’s true in all writing, of course, but it has a particular acuteness (I don’t know why) when it comes to dialogue.

If you include an unnecessary sentence or two in a passage of description – well, it’s best to avoid that, of course, but, aside from registering a minor and temporary slowing, most readers won’t notice or care.

Do the same in a block of dialogue, and your characters will seem to be speechifying rather than speaking. It’ll feel to a modern reader like you want to turn the clock back to Victorian England.

So don’t do it!

Keep it spare. Allow gaps in the communication and let the readers fill in the blanks. It’s like you’re not even giving the readers 100% of what they want. You’re giving them 80% and letting them figure out the rest.

Take this, for instance, from Ian Rankin’s fourteenth Rebus crime novel, A Question of Blood. The detective, John Rebus, is phoned up at night by his colleague:

… “Your friend, the one you were visiting that night you bumped into me …” She was on her mobile, sounded like she was outdoors.

“Andy?” he said. ‘Andy Callis?”

“Can you describe him?”

Rebus froze. “What’s happened?”

“Look, it might not be him …”

“Where are you?”

“Describe him for me … that way you’re not headed all the way out here for nothing.”

That’s great isn’t it? Immediate. Vivid. Edgy. Communicative.

But look at what isn’t said. Here’s the same passage again, but with my comments in square brackets alongside the text:

… “Your friend, the one you were visiting that night you bumped into me …” She was on her mobile, sounded like she was outdoors.

[Your friend: she doesn’t even give a name or give anything but the baresr little hint of who she’s speaking about. And ‘on her mobile, sounded like she was outdoors’. That’s two sentences rammed together with a comma. It’s so clipped you’ve even lost the period and the second ‘she’.]

“Andy?” he said. ‘Andy Callis?”

[Notice that this is exactly the way we speak. He could just have said “Andy Callis”, but in fact we often take two bites at getting the full name, like this. That broken, repetitive quality mimics exactly the way we speak . . . or at least the way we think we speak!]

“Can you describe him?”

[Uh-oh. The way she jumps straight from getting the name to this request indicates that something bad has happened. A lesser writer would have this character say, ‘Look, something bad has happened and I’m worried. So can you describe him?’ This clipped, ultra-brief way of writing the dialogue achieves the same effect, but (a) shows the speaker’s urgency and anxiety – she’s just rushing straight to the thing on her mind, (b) uses the gap to indicate the same thing as would have been (less well) achieved by a wordier, more direct approach, and (c) by forcing the reader to fill in that gap, you’re actually making the reader engage with intensity. This is the reader as co-writer – and that means super-engaged.]

Rebus froze. “What’s happened?”

[Again: you can’t convey the same thing with fewer words. Again, the shimmering anxiety about what has still not been said has extra force precisely because of the clipped style.]

“Look, it might not be him …”

[A brilliantly oblique way of indicating, “But I’m frigging terrified that it is.” Oblique is good. Clipped is good.]

“Where are you?”

[A non-sequitur, but totally consistent with the way people think and talk.]

“Describe him for me … that way you’re not headed all the way out here for nothing.”

Just as he hasn’t responded to what she had just said, now it’s her turn to ignore him. Again, it’s the absences that make this bit of dialogue live. Just imagine how flaccid this same bit would be if she had said, “Let’s not get into where I am right now. Look, it’s important that you describe him for me . . .”]

In short:

Gaps are good. They make the reader work, and a ton of emotion and inference swirls in the gaps.

Want to achieve the same effect? Copy Rankin. Keep it tight.

Dialogue rule 2: Watch those beats

Oftener than not, great story moments hinge on character exchanges,that have dialogue at their heart. Even very short dialogue can help drive a plot, showing more about your characters and what’s happening than longer descriptions can.

(How come? It’s the thing we just talked about: how very spare dialogue makes the reader work hard to figure out what’s going on, and there’s an intensity of energy released as a result.)

But right now, I want to focus on the way that dialogue needs to create its own emotional beats. So that the action of the scene and the dialogue being spoken becomes the one same thing.

Here’s how screenwriting guru Robert McKee puts it:

Dialogue is not [real-life] conversation. … Dialogue [in writing] … must have direction. Each exchange of dialogue must turn the beats of the scene … yet it must sound like talk.

This excerpt from Thomas Harris’ The Silence of the Lambs is a beautiful example of exactly that. It’s short as heck, but just see what happens.

As before, I’ll give you the dialogue itself, then the same thing again with my notes on it:

“The significance of the chrysalis is change. Worm into butterfly, or moth. Billy thinks he wants to change. … You’re very close, Clarice, to the way you’re going to catch him, do you realize that?”

“No, Dr Lecter.”

“Good. Then you won’t mind telling me what happened to you after your father’s death.”

Starling looked at the scarred top of the school desk.

“I don’t imagine the answer’s in your papers, Clarice.”

Here Hannibal holds power, despite being behind bars. He establishes control, and Clarice can’t push back, even as he pushes her. We see her hesitancy, Hannibal’s power. (And in such few words! Can you even imagine trying to do as much as this without the power of dialogue to aid you? I seriously doubt if you could.)

But again, here’s what’s happening in detail

“The significance of the chrysalis is change. Worm into butterfly, or moth. Billy thinks he wants to change. … You’re very close, Clarice, to the way you’re going to catch him, do you realize that?”

[Beat 1: Invoking the chrysalis and moth here is almost magical language. it’s like Hannibal is the magician, the Prospero figure. Look too at the switch of tack in the middle of this snippet. First he’s talking about Billy wanting to change – then about Clarice’s ability to find him. Even that change of tack emphasises his power: he’s the one calling the shots here; she’s always running to keep up.]

“No, Dr Lecter.”

[Beat 2: Clarice sounds controlled, formal. That’s not so interesting yet . . . but it helps define her starting point in this conversation, so we can see the gap between this and where she ends up.]

“Good. Then you won’t mind telling me what happened to you after your father’s death.”

[Beat 3: Another whole jump in the dialogue. We weren’t expecting this, and we’re already feeling the electricity in the question. How will Clarice react? Will she stay formal and controlled?]

Starling looked at the scarred top of the school desk.

[Beat 4: Nope! She’s still controlled, just about, but we can see this question has duanted her. She can’t even answer it! Can’t even look at the person she’s talking to.]

“I don’t imagine the answer’s in your papers, Clarice.”

[Beat 5: And Lecter immediately calls attention to her reaction, thereby emphasising that he’s observed at and knows what it means.]

Overall, you can see that not one single element of this dialogue leaves the emotional balance unaltered. Every line of dialogue alters the emotional landscape in some way. That’s why it feels so intense & engaging.

Want to achieve the same effect? Just check your own dialogue, line by line. Do you feel that emotional movement there all the time? If not, just delete anything unecessary until you feel the intensity and emotional movement increase.

Dialogue Rule 3: Keep it oblique

One more point, which sits kind of parallel to the bits we’ve talked about already.

It’s this.

If you want to create some terrible dialogue, you’d probably come up with something like this:

“Hey Judy.”

“Hey, Brett.”

“You OK?”

“Yeah, not bad. What do you say? Maybe play some tennis later?”

“Tennis? I’m not sure about that. I think it’s going to rain.”

Tell me honestly: were you not just about ready to scream there? If that dialogue had continued like that for much longer, you probably would have done.

And the reason is simple. It was direct, not oblique.

So direct dialogue is where person X says something or asks a question, and person Y answers in the most logical, direct way.

We hate that! As readers, we hate it.

Oblique dialogue is where people never quite answer each other in a straight way. Where a question doesn’t get a straightforward response. Where random connections are made. Where we never quite know where things are going.

As readers, we love that. It’s dialogue to die for.

And if you want to see oblique dialogue in action, here’s a snippet from Aaron Sorkin’s The Social Network. (We don’t usually reference films so much on this blog, but there’s an obvious exception when it comes to talking about dialogue.) So here goes. This is the young Mark Zuckerberg talking with a lawyer:

Lawyer: “Let me re-phrase this. You sent my clients sixteen emails. In the first fifteen, you didn’t raise any concerns.”

MZ: ‘Was that a question?’

L: “In the sixteenth email you raised concerns about the site’s functionality. Were you leading them on for 6 weeks?”

MZ: ‘No.’

L: “Then why didn’t you raise any of these concerns before?”

MZ: ‘It’s raining.’

L: “I’m sorry?”

MZ: ‘It just started raining.’

L: “Mr. Zuckerberg do I have your full attention?”

MZ: ‘No.’

L: “Do you think I deserve it?”

MZ: ‘What?’

L: “Do you think I deserve your full attention?”

I won’t discuss that in any detail, because the technique really leaps out at you. It’s particularly visible here, because the lawyer wants and expects to have a direct conversation. (I ask a question about X, you give me a reply that deals with X. I ask a question about Y, and …) Zuckerberg here is playing a totally different game, and it keeps throwing the lawyer off track – and entertaining the viewer/reader too.

Want to achieve the same effect? Just keep your dialogue not quite joined up. People should drop in random things, go off at tangents, talk in non-sequiturs, respond to an emotional implication not the thing that’s directly on the page – or anything. Just keep it broken. Keep it exciting!

Dialogue rule 4: reveal character dynamics and emotion

Let’s take a look here at Stephen Chbosky’s The Perks of Being a Wallflower as another example.

Protagonist Charlie, a high school freshman, learns his long-time crush, Sam, may like him back, after all. Here’s how that dialogue goes:

“Okay, Charlie … I’ll make this easy. When that whole thing with Craig was over, what did you think?”

… “Well, I thought a lot of things. But mostly, I thought your being sad was much more important to me than Craig not being your boyfriend anymore. And if it meant that I would never get to think of you that way, as long as you were happy, it was okay.” …

… “I can’t feel that. It’s sweet and everything, but it’s like you’re not even there sometimes. It’s great that you can listen and be a shoulder to someone, but what about when someone doesn’t need a shoulder? What if they need the arms or something like that? You can’t just sit there and put everybody’s lives ahead of yours and think that counts as love. You just can’t. You have to do things.”

“Like what?” …

“I don’t know. Like take their hands when the slow song comes up for a change. Or be the one who asks someone for a date.”

The words sound human.

Sam and Charlie are tentative, exploratory – and whilst words do the job of ‘turning’ a scene, both receiving new information, driving action on – we also see their dynamic.

And so we connect to them.

We see Charlie’s reactive nature, checking with Sam what she wants him to do. Sam throws out ideas, but it’s clear she wants him to be doing this thinking, not her, subverting Charlie’s idea of passive selflessness as love.

The dialogue shows us the characters, as clearly as anything else in the whole book. Shows us their differences, their tentativeness, their longing.

Want to achieve the same effect? Understand your characters as fully as you can. The more you can do this, the more naturally you’ll write dialogue that’s right for them. You can get tips on knowing your characters here.

A few last dialogue rules

If you struggle with writing dialogue, read plays or screenplays for inspiration. Read Tennessee Williams or Henrik Ibsen. Anything by Elmore Leonard is great. Ditto Raymond Chandler or Donna Tartt.

Some last tips:

Keep speeches short. If a speech runs for more than three sentences or so, it (usually) risks being too long.

Ensure characters speak in their own voice. And make sure your characters don’t sound the same as each other.

Add intrigue. Add slang and banter. Lace character chats with foreshadowing. You needn’t be writing a thriller to do this.

Get in late and out early. Don’t bother with small talk. Decide the point of each interaction, begin with it as late as possible, ending as soon as your point is made.

Interruption is good. So are characters pursuing their own thought processes and not quite engaging with the other.

6 notes

·

View notes

Link

This is one of a few times I’m NOT going to copy and paste the contents of the page as these are in many cases VERY explicit. I suggest using with caution in writing as personally I have no idea how crude these are culturally.

1 note

·

View note

Link

Mandarin25 Hysterical Chinese Insults That You Should Know Today (NSFW)

Chinese insults words are different than what an English speaker may expect. What we think as some of the most insulting words in our language barely register to a Chinese speaker. Conversely, we might think some of China’s most offensive insults are actually quite funny in English. Even funnier than some of the English swear words we have.

That’s why it’s always best to study a bunch before speaking. That includes your insults. So yes, this is a time where we are going to tell you to insult and curse nonstop. With that practice, you’ll soon find out that these words can be both funny translations as well as some unexpected funny insults into Mandarin speakers.

25 Chinese Insults That You Should Know

Let’s explore some the language’s most colorful insults and what they mean to English speakers:

Animals

Chinese insults tend to incorporate animals quite often. In some instances, the term is more harmless. In other cases, they can pack a pretty hurtful punch:

1. 猪头 (zhū tóu) — “Pig head”

This is one that English speakers should have no problem recognizing. Around the world it seems that a pig’s head is known for the symbol or being stubborn. Use this to describe the same typically male crowd in China as you would across the globe.

2. 吹牛 (chuī niú) — “Blowing up cow skin”

This is probably the tamest insult on the list. However, when saying a bragger is blowing up cow’s skin, you have to include it on your list. This one also ties back into history with an intriguing test of strength amongst some Mongolians.

3. 拍马屁 (pāi mă pì) — “Pat a horse’s ass”

English Speakers call it “brown nosing.” Others might say ‘kiss up.’ Regardless the term, these insults will let the person know you think that they endear themselves to higher-ups quite often. In the hard-working world in China, you can only imagine how many people have earned this distinction.

4. 狗屁 (gŏu pì) — “Dog fart”

This is Chinese’s equivalent to “bullshit” and “bollocks.” You don’t so much call someone 狗屁. Instead, you use this Chinese insults to call someone out on their b.s. Because of its tone and situational use, steer clear of using this one at work. Instead, keep this one between your friends at the pub.

5. 狐狸精 (hú li jīng) — “Fox spirit”

Foxes carry deep symbolism in Chinese culture. For women, unfortunately, this becomes an additional insult in the Chinese language. If you call someone a fox spirit, you are calling them a danger to men that possess some dark intentions.

6. 色狼 (sè láng) — “Color-seeking wolf”

If foxes are bad for women, then wolves aren’t great for older men. This Chinese insult is used to label something a predator. Though often related to a sexual nature, it can also be towards anyone preying on the young. If an older male-targeted a 小白脸, then they might be called a 色狼.

7. 王八 (biē) — “Freshwater turtle”

This is a big insult. Promiscuity is a big point in Chinese insults. Women, in particular, face a brunt of the insults. In this case, they associate the image of a turtle and its similarities to the male anatomy. However, eggs once again come into play in Chinese insults. In this case, you are using one of the most offensive ones.

8. 狗崽子 (góu zaĭ zi) — “Dog Whelp”

This is another one that would make an English speaker laugh while a Chinese person gets livid. The closest equivalent you’ll find in English is “son of a bitch.” However, in most parts of the English speaking world, this insult won’t mean much. In Chinese, it is a whole different story.

9. 兔崽子 (tù zaĭ zi) — “Rabbit whelp”

If dog whelps are incredibly hurtful in Chinese, consider a rabbit to a slight bit less of an insult. However, it still packs a punch. Much like the previous entry, the English equivalent isn’t so hurtful while impacting Chinese speakers much more. In English, we’d use this word to call someone young a real piece of work.

10. 土鳖 (Too Bee-eh) –“Ground Beetle”

You might hear folks in Beijing, Shanghai and other major cities use this to describe out of towners. Used mostly towards China’s more rural population, this is what some English speakers might call a “fish out of the water.”

11. 死鱼眼 (Sǐ Yú Yǎn) — “Dead fish eye”

In English, you may hear that someone looks “dead behind the eyes.” In Chinese, this similar term conveys a person that looks vapid and out of reality’s touch.

Another emerging English term that also does the trick in Chinese would be Kardashian.

Chinese Insults Using Food

Much like animals, food plays a hand in both the harsh and friendlier Chinese insults. One thing is for sure, eggs mean much more than they do in English.

12. 生個叉燒都好過生你 — “It would be better to have given birth to a piece of barbecue pork instead.”

This is a common phrase used by exhausted parents. When a child is just not giving up, even a loving parent will crack. Instead of saying something truly hurtful, this mainly Cantonese insult helps blow off steam without harming the child with something actually mean.

13. 吃软饭 — “To eat soft rice”

Eating soft rice is a way of saying that a Chinese man is living off his girlfriend. In English, you might hear a “mooch” or a “sap.” When you need to tell someone that it’s time they support themselves, this is what you say.

14. 懒蛋 (lǎn dàn) — “Lazy egg”

This is an insult that veers more into the tame category. Consider this the American equivalent of calling your friend “a lazy bum.” You might hear a parent say this to a child or a girlfriend to a boyfriend. While it doesn’t pack a brutal sting, it is one of China’s many egg-themed insults.

15. hún dàn (混蛋) — “Mixed egg” or “Scumbag”

On the other side of egg-based insults, this one stings a bit. Calling someone a scumbag in any language is bound to cause some conflict. So, don’t go throwing this word around in public, or even in many private settings. That is unless you’re looking to exchange many more colorful words as a follow-up.

The More Obscure

These are some of the more hysterical insults due to their translations. Some are specific while others may leave you scratching your head. However, this is the fun of learning another language. In this section, you’ll get to learn some doozies that include some history as well.

16. 肏你祖宗十八代 (cào nǐ zǔzōng shíbā dài) — “Fuck your ancestors to the eighteenth generation”

Family and history are sacred in Chinese culture. With a long-running history, the pride you have in your family is vital. That’s why this one may seem like a comical mental image, but is one of the language’s more impactful insults. Unless you want to make a situation ugly, it’s best to avoid insulting any Chinese ancestors.

That being said, there are a couple variations of this insult that are fun to play around with. Try with a friend that won’t get offended.

17. 二百五 (èr bǎi wŭ) — “250”

You’d think that calling someone a number wouldn’t hurt, right? Yet in Chinese that isn’t the case. While this one’s definition is a bit vague, many believe it translates to calling someone not enough. This stems from the ancient Chinese currency revolving around 1,000 copper coins. Essentially, “500” was an insult for a halfwit. So, you can imagine what it felt like to be called half of that.

18. 小白脸 (xiǎo bái liǎn) — “Little white face”

A little white face typically applies to naive men. When someone hasn’t experienced much in the world, this mild insult is what Chinese speakers use. This also works to wind up so-called pretty boys and older female gold diggers. Now, imagine this being used in the famous Kanye West track.

19. 装蒜 (Joo-ang Swan) — “Wait til”

The English equivalent here would be used when calling someone dumb. However, this Chinese insult relates to the history of garlic and medicine in China. What was once considered a remedy is now a symbol for someone’s foolishness.

20. 你算哪根葱 (Nǐ Suàn Nǎ Gēn Cōng) –“Who the hell are you?”

Sometimes we all need to be reminded that we’re just a person like everyone else. In this case, you wouldn’t use this Chinese insult for when you don’t know someone. Instead, it’s more for calling someone out. If someone is acting rudely or mistreating people, this insult checks them down a bit. \

21. 绿茶婊 (Lǜ Chá Biào) –“Green Tea Bitch”

What’s so wrong with green tea?! Well, in this case, it means that what someone is presenting on the outside isn’t their true representation. If a person looks innocent on the outside but devious on the inside, the Chinese would call them a 绿茶婊.

22 – 25. Ghosts