#y gododdin

Text

The Birth of Myth

A period piece about the composition of Y Gododdin by the Welsh bard Aneirin. While the film is almost entirely about the development of old and middle Welsh poetry, the end of the film teases the Arthurian legend as one stanza obliquely references King Arthur, setting up a series of other films about literary references to the character.

#bad idea#movie pitch#pitch and moan#king arthur#arthurian legend#arthur pendragon#arthuriana#arthurian mythology#arthurian literature#welsh#british#british history#english history#english literature#medieval literature#saga#poetry#welsh bard#bard#y gododdin#aneirin#mythology#old welsh#middle welsh#period film

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

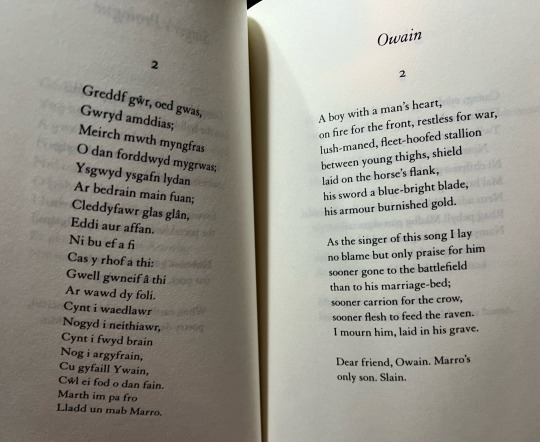

I picked up Gillian Clarke's translation of Y Gododdin. To my surprise, I read it all in one sitting.

It's *beautiful,* and poignant, and terribly bittersweet. I picked it up because it's got the earliest mention of Arthur, briefly, in one line. But I have no regrets about picking up a whole book for one line, because ye gods. It's an incredible read.

The second verse took my breath away:

2. Owain

A boy with a man's heart,

on fire for the front, restless for war,

lush-maned, fleet-hoofed stallion

between young thighs, shield

laid on the horse's flank,

his sword a blue-bright blade,

his armour burnished gold.

As the singer of this song I lay

no blame but only praise for him

sooner gone to the battlefield

than to his marriage-bed;

sooner carrion for the crow,

sooner flesh to feed the raven.

I mourn him, laid in his grave.

Dear friend, Owain. Marro's

only son. Slain.

And so I was hooked. I kept meaning to put the book away, and kept reading just one more poem, until suddenly I was at the end.

For the Arthuriana, since I'm keeping this Tumblr pretty focused, here's the poem that mentions Arthur. It's the second-to-last of the elegies.

99. Gwawrddur

Charging ahead of the three hundred

he cut down the centre and the wing.

Blazing ahead of the finest army,

he gave horses from his winter herd.

He fed ravens on the fortress wall

though he was no Arthur.

Among the strongest in the war,

Gwawrddur, citadel.

I absolutely recommend this book, regardless of your interest or lack thereof in Arthurian literature. I don't know enough about different translations, but Gillian Clarke was the National Poet of Wales for eight years, and this is her life's work. She strove to convey the poetry, rhythm, musicality, and power of the original work while also keeping the meaning, whereas other translations are more academic and focused on literal accuracy. So which translation you go for depends on why you're reading it.

#y gododdin#the gododdin#gillian clarke#arthurian newbie#reading list#resources#lament for the fallen

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

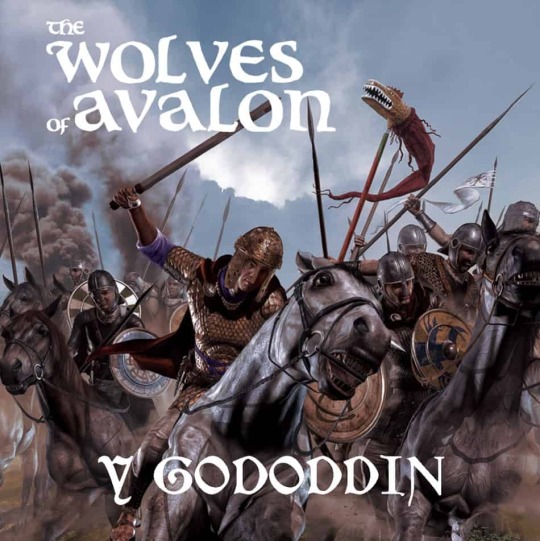

Album Review: Y Gododdin by The Wolves of Avalon (Godreah Records)

Album Review: Y Gododdin by The Wolves of Avalon (Godreah Records)

It is time to step back through the ages once more with The Wolves Of Avalon on their new album, Y Gododdin, due for release on the 25th of November via Godreah Records.

Formed in 2009 by Metatron (The Meads Of Asphodel) and song writer James Marinos, the band’s fourth album, Y Gododdin, brings us a vision of the Gododdin, Northern warriors whose battles against the Angle tribes are documented in…

View On WordPress

#Across Corpses Grey#Album Review#ancient Britain#Aneirin#Black Metal#Drudkh#Folk Metal#Godreah Records#James Marinos#Metatron#Pagan Metal#Primordial#Sigh#Taake#The Meads Of Asphodel#The Wolves of Avalon#Venom Inc.#Y Gododdin

0 notes

Text

if you had your heart broken by The Shining Company as an impressionable pre-teen, you may be be eligible for a medieval studies degree

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

just come to the realisation that I'm essentially the equivalent of the Jungkook = Princess Diana person on twt except if they were forced to read early mediaeval primary sources and hagiographies instead of documentaries about the British royal family.

#anyways had to reread parts of Y Gododdin and Preiddeu Annwfyn today#had a terrifying thought about how the Gildas Arthur relationship might transfer over#anyways not saying an insane m*picc theory is coming soon or anything#but#what if it wasn't just gildas and m*pic was actually also possessed/influenced by someone#zam could even be taliesin!

0 notes

Text

Ségurant, the Knight of the Dragon (1/4)

In order to do my posts about Ségurant, I will basically blatantly plagiarize the documentary I recently saw - especially since it will be removed at the end of next January. If you don't remember from my previous post, it is an Arte documentary that you can watch in French here. There's also a German version somewhere.

The documentary is organized very simply, by a superposition of research-exploration-explanation segments with semi-animated retellings of extracts of the lost roman.

0: The origin of it all

The documentary is led by and focused on the man behind the rediscovery of Ségurant, the Knight of the Dragon – Emanuele Arioli, presented simply as a researcher in the medieval domain, expert of the Arthurian romances, and deeply passionate by the Arthurian legend and chivalry. If you want to be more precise, a quick glimpse at his Wikipedia pages reveals that he is actually a Franco-Italian an archivist-paleographer, a doctor in medieval studies, and a master of conferences in the domain of medieval language and medieval literature.

It all began when Arioli was visiting the Bibliothèque de l’Arsenal, at Paris. There he checked a yet unstudied 15th century manuscript of “Les prophéties de Merlin”. Everybody knows Monmouth’s Prophetiae Merlini, but it is not this one – rather it is one of those many “Merlin’s Prophecies” that were written throughout the Middle-Ages, collecting various “political prophecies” interwoven with stories taken out of the legends of king Arthur and the Round Table. And while consulting this specific 15th century “Prophéties de Merlin”, Arioli stumbled upon a beautiful enluminure (I think English folks say “illumination”) of a knight facing a dragon. Interested, he read the story that went with it… And discovered the tale of Ségurant, a knight he had never heard about during the entirety of his studies.

Here we have the first fragment of Ségurant’s story: “Ségurant le Brun” (Ségurant the Brown, as in Brown-haired, you could call him Ségurant the Dark-haired, Ségurant the Brunet), a “most excellent and brave knight”, sent a servant to Camelot, court of king Arthur, and in front of the king the servant said – “A knight from a foreign land sends me there, and asks you to go in three days onto the plain of Winchester, with your knights of the Round Table, to joust. You will see there the greatest marvel you ever saw.”

Checking the rest of the manuscript, Arioli found several other episodes detailing Ségurant’s adventures, all beginning with illuminations of a knight facing a dragon. And this was the beginning of Arioli’s quest to reconstruct a roman that had been forgotten and ignored by everybody – a quest that took him ten years (and in the documentary he doesn’t hide that he ended up feeling himself a lot within Ségurant’s character who is also locked in an impossible quest).

I: Birth of king, birth of myth

The first quarter of the documentary or so is focused on Arioli’s first step in his quest for Ségurant: Great-Britain of course! However, slight spoiler alert, Arioli didn’t find anything there – and so the documentary spends a bit more time speaking about king Arthur than Ségurant, though it does fill in with various other extracts of Ségurant’s story.

Arioli’s first step was of course the National Library of Wales, where the most ancient resources about king Arthur are kept, and where old Celtic languages and traditions are still very much alive, or at least perfectly preserved. The documentary has Ceridwen Lloyd-Morgan presenting the audience with the oldest record of the name Arthur in Welsh literature – if not in European literature as a whole. The “Y Gododdin”, where one of the characters described is explicitly compared to Arthur in negative, “even though he was not Arthur”. The Y Gododdin is extremely hard to date, though it is very likely it was written in the 7th century – and all in all, it proves that Arthur was known of Welsh folks at the time, probably throughout oral poems sung by bards, and already existed as a “good warrior” or “ideal leader” figure.

From there, we jump to a brief history lesson. Great-Britain used to be the province of the Roman Empire known as Britannia – and when the Romans left, it became the land of the Britons (in French we call them “Bretons” which is quite ironic because “Breton” is also the name of the inhabitants of the Britany region of France – Bretagne. This is why Great-Britain is called Great-Britain, the Britany of France was the “Little-Britain”, and this is also why the Britain-myth of Arthur spreads itself across both England and France – but anyway). However, ever since the 5th century, Great-Britain had fallen into social and political instability, as two Germanic tribes had invaded the lands: the Angles and the Saxons. In the year 600, the Angles and the Saxons were occupying two-thirds of Great-Britain, while the Britons had been pushed towards the most hostile lands – Cornwall, Wales and Scotland. This era was a harsh, cruel and dark world, something that the Y Gododdin perfectly translates – and thus it makes sense that the figure of Arthur would appear in such situation, as the mythical hero of the Briton resistance against the Anglo-Saxons.

However we had to wait until a Latin work of the 12th century for Arthur’s fate to finally be tied to the history of the kings of England: Geoffrey of Monmouth, a Welsh bishop, wrote for the king of England of the time the “Historia Regum Britanniae”, “History of the Kings of Britain”, in which we find the first complete biography of Arthur as a king – twenty pages or so about “the most noble king of the Britons”. Geoffrey’s record was a mix of real and imagination, weaving together fictional tales with historical resources – it seems Geoffrey tried to make Arthur “more real” by including him into the actual History with a big H, and it is thanks to him that we have the legend of Arthur as we know it today ; even though his Arthur was a “proto-Arthur”, without any knight or Round Table. The tale begins in Cornwall, at Tintagel, where Arthur was conceived: one night, Uther Pendragon, with the help of Merlin, took the shape of the Duke of Cornwall to enter in his castle and sleep with his wife Igraine. This was how Arthur was born.

The documentary then has some presentations of the archeological work on Tintagel – filled with enigmatic and mysterious ruins. The current archeological research, and a scientific project in 2018, allowed for the discovery of proof that the area was occupied as early as 410, and then all the way to the 9th and 10th century, maybe even the years 1000. There are many elements indicating that Tintagel was inhabited during the post-Roman times when Arthur was supposed to have lived: post-Roman glass, and various fragments of pottery coming from Greece or Turkey and other parts of the Eastern Mediterranean Sea – overall the area clearly was heavily influenced by Mediterranean commerce and cultures. Couple that with the fact that we have the ruins of more than a hundred buildings built solidly with the stone of the island – that is to say more buildings than what London used to have during the same era – and with the fact that there are scribe-performed inscriptions for various families and third parties (meaning people were important or rich enough to buy a scribe to write things for them)… All of this proves that Tintagel was important, wealthy and connected, and so while it does not prove Arthur did exist, it proves that a royal court might have existed at Tintagel – and that Geoffrey of Monmouth probably selected Tintagel as the place of birth of Arthur because he precisely knew of how ancient and famous the area was, through a long oral tradition.

2: After birth, death

The next area visited by the documentary is Glastonbury. “On a Somerset hill formerly surrounded by swamps and bogs”, medieval tradition used to localize the fabulous island of Avalon – where Arthur, mortally wounded by his son Mordred, was taken by fairies. Healed there, he ever since rests under the hill, and will, the story says, return in the future to save the Britons when they need it the most… More interestingly fifty years after Monmouth’s writings, the actual grave of king Arthur was supposedly discovered in the cemetery of the abbey of Glastonbury, and can still be visited today. It is said that in 1191, the monks of the abbey were digging a large pit in their cemetery, 12 feet deep, when they find a rough wooden coffin with a great lead cross on which were written “Here lies king Arthur, on the island of Avalon”. Now, you might wonder, why were monks digging a pit in their cemetery? Sounds suspicious… Well it is said that Henry II was the one who told the monks that, if they dug in their cemetery, they might find “something interesting”… Why would Henry II order a research for the grave of king Arthur? Very simple – a political move. Henry II was a Plantagenet king, aka part of a Norman bloodline, from Normandy, and the House of Plantagenet had gained control of their territory through wars. The Plantagenet was a dynasty that won large chunks of territory through battles (or through marriage – Henri II married Aliénor d’Aquitaine in 1152, which allowed him to extend his empire so that it ended up covering not just all of Great-Britain but also three quarters of France). But as a result, the Plantagenet House had to actually “justify” themselves, prove their legitimacy – prove that they were not just ruling because they were conquerers that had beaten or seduced everybody. They needed to tie themselves to Briton traditions, to link themselves to the legends of Britain – and the “discovery” of king Arthur’s tomb was part of this political plan. And it was a huge success – Glastonbury became famous, and so did king Arthur, who went from a mere Briton war-chief that maybe existed, to a true legend and symbol of English royalty.

However, so far, there are no traces of Ségurant in the Welsh tradition, and here we get our second extract of Ségurant’s roman, which actually seems to be the beginning of his adventures.

Ségurant comes from a fictional island (or at least going by a fictional name): l’île Non-Sachante. There Ségurant le Brun was knighted on the day of the Pentecost by his own grandfather. There was great merriment and great joy, and after the party, Ségurant openly declared he wanted to see the court of king Arthur and all the great wonders in it that everybody kept talking about. He claimed he would go to Winchester – and thus it leads to the invitation mentioned above. Yep, he decided that the best way to go see king Arthur’s court and his wonders was to basically challenge the king and his knights…

3: No place at the Round Table

Of course, the next step of the documentary is Winchester, former capital of Saxon England. Some traditions claim that it was at Winchester that Camelot was located, king Arthur’s castle and the capital of his Royaume de Logres, Kingdom of Logres. Logres itself being actually clearly the dream of a land rebuilt and given back to the Britons, once all the Germanic invaders are kicked out.

The documentary goes to Winchester Castle, built by William the Conqueror, and takes a look at the famous “Round Table” kept within its Great Hall – a table on which are written the name of 24 Arthurian knights, with a painting of king Arthur at the center… Above the rose of the Tudors. Because, that’s the thing everybody knows – while the Round Table itself was built in the 13th century and presented as an “Arthurian relic”, it was repainted in the shape it is today during the 16th century, by Henry the Eight (you know, the wife-killer), who used it as yet another political tool to impose and legitimize the rule of the Tudor line – and he wasn’t subtle about it, since he had Arthur’s face painted to look like his… On this table you find the names of many of the famous Arthurian knights: Galahad, Lancelot of the Lake, Gawain, Perceval, Lionel, Mordred, Tristan, the Knight with the Ill-Fitting Coat… They were organized according to a hierarchy (despite the very principle of the table being there was no hierarchy): at the top are the most famous and well-known knights, with their own stories and quests, such as Galahad, Lancelot of Gawain. At the bottom are the less famous ones: Lucan, Palamedes, Lamorak, Bors de Ganis…

And Ségurant is, of course, absent. Which can be baffling when you consider what the story about Ségurant actually says…

NEW EXTRACT! We are on the field of Winchester. All the tents are prepared for the greatest tournament Logres ever knew. The tent of Ségurant is very easy to spot, because there is a precious stone at the top, that shines day and knight, constantly emitting light as if it was a flaming torch. In front of king Arthur, all the bravest and most courageous knights of the Round Table appear and joust between them: Lancelot and Gawain are explicitly named. Suddenly, Ségurant appears and defies them all in combat! One by one, the knights of the Round Table battle with Ségurant – but all their spears break themselves onto his shield, and in the end, no knight wants to defy him, realizing they could not possibly defeat him. And in the audience, a rumor start spreading… “For sure, it will be him, the knight who will find the Holy Grail!”

So we have a knight who managed to defeat all the knights of the Round Table, in front of king Arthur, and yet nobody talks about him? But as the documentary reminds the audience – the Winchester Round Table only contains knights that the British tradition is familiar with. There many Arthurian knights with their own story and quests, such as Erec or Yvain the Knight of the Lion, who are absent from it… Because they are part of the French tradition, and thus less popular if not frankly ignored by England (a specific mention goes to Erec who was only translated very recently into English apparently, and for centuries and centuries stayed unknown in the English-speaking world).

Anyway – the conclusion of this first part of the documentary is simple. Ségurant is not from Great-Britain, he is not British nor Welsh, and so his origins lie somewhere else.

ADDENDUM

In the first part of this documentary, they stay quite vague and allusive about the story of Ségurant (because the documentary is obviously about the quest and research behind the reconstruction of the roman, not about what the roman contains in every little details). So to flesh out a bit the various extracts above I will use some information from the very summary Wikipedia page about this recently rediscovered knight (I didn’t had the time to get my hands on the book yet).

In the version that is the “main” one reconstructed by Arioli and that is the basis for the documentary’s retelling, soon before being knighted, Ségurant had proved his worth by performing a successful “lion hunt” onto the Ile Non-Sachante. Said island is actually said to have originally been a wild and deserted island onto which his grand-father, Galehaut le Brun, and his grand-father’s brother, Hector le Brun, had arrived after a shipwreck – they had taken the sea to flee an usurper on the throne of Logres named Vertiger (it seems to be a variation of Vortigern?). Galehaut le Brun had a son, Hector le Jeune (Hector the Young), Ségurant’s father. However, unlike the documentary which presents Ségurant as immediately wishing to see Camelot and defy its knights as soon as he is knighted, the Wikipedia page explains there is apparently a missing episode between the two events: in the roman, Ségurant originally leave the Ile Non-Sachante to defeat his uncle (also named Galehaut, like his grandfather) on the mainland. After beating his uncle at jousting, rumors of his various feats and exploits reached Camelot, and it was king Arthur himself who decided to organize a tournament in Ségurant’s honor at Winchester, so that the Knights of the Round Table could admire Ségurant’s exploits.

The fact that the documentary presents a version of the story when the Knights of the Round Table are already in search for the Holy Grail when Ségurant arrives at Winchester is quite interesting because according to the Wikipedia article, Ségurant’s name is mentioned in a separate text (a late 15th century armorial) as one of the knights of the Round Table who was present “when they took the vow of undergoing the quest of the Holy Grail, on Pentecost Day”. The same armorial then goes on to add more elements about Ségurant’s character. Here, instead of being the son of “Hector the Young”, he is son of “Hector le Brun” (so the whole family is “Brown” then), and this title is explained by the color of his hair, which is actually of a brown so dark it is almost black. Ségurant is described here as a very tall man, “almost a giant”, and to answer this enormous height, he has an incredible and powerful strength, coupled with a great appetite making him eat like ten people. But he is actually a peaceful, gentle soul, as well as a lone wolf not very social. He also is said to have a beautiful face, and to be “well-proportioned” in body. A final element of this armorial, which is the most interesting when compared to the main story given by the documentary (where the dragon comes afterward) – in this armorial, Ségurant is actually said to have killed a dragon BEFORE being knighted, a “hideous and terrible” dragon, and this is why his coast of arms depict a black dragon with a green tongue over a gold background.

Again, this all comes from an armorial kept at the Bibliothèque de l’Arsenal – which has a small biography and drawing of Ségurant over one page (used to illustrate the French Wikipedia article). It is apparently not in the “roman” that Arioli reconstructed – especially since in the comic book adaptation, and the children-illustrated-novel adaptations, not only is Ségurant depicted as of regular size, but he is also BLOND out of all things…

As for the name of the island Ségurant comes from, “l’île Non-Sachante”, it is quite a strange name that means “The Island Not-Knowing”, “The Unknowing island”, “The island that does not know”. This is quite interesting because, on one side it seems to evoke how this is an island not known by regular folks – this wild, uncharted, unmapped island on which Ségurant’s family ended up, and from which this mysterious all-powerful knight comes from (and you’ll see that the fact nobody knows Ségurant’s island is very important). But there is also the fact that the adjective “Sachante” is clearly at the female form, to match the female word “île”, “island”, meaning it is the island that does not “know”. And given it is supposed to be this wild place without civilization, it seems to evoke how the island doesn’t know of the rest of the world, or doesn’t know of humanity. (Again I am not sure, I haven’t got the book yet, I am just making basic theories and hypothetic reading based on the info I found)

#ségurant#segurant#the knight of the dragon#le chevalier au dragon#arthurian myth#arthuriana#arthurian literature#arthurian legend#king arthur#arthurian romance

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

Unglücksrabe - "Raven of Ill Luck"

The Germans have a word for it, naturally - Unglücksrabe, raven of ill luck. Usually meant for a person who is plagued by slings and arrows of outrageous fortune on a regular basis. "Er ist ein Unglücksrabe!"

Art by Catbat

When the Welsh poet Aneirin wrote his Y Gododdin, an elegy to the fall of the Brytonic Old North at some time between the 7th and the 10th century CE, a transvaluation of values in terms of ravens had taken place long since from the shamanistic trickster spirit of old to the kenning for battle in northwestern Europe. Nearly every stanza of Y Gododdin has a reference to the birds along the lines of “Sooner than to a nuptial feast; / Thou hast become a meal for ravens”, “And the head of Dyvnwal Vrych by ravens devoured”, “And on his white bosom the sable raven is perched” and whatnot.

Ravens kept their roles as messengers, though, once to the gods, Apollo and Odin, to name a few, and from the Middle Ages onwards they became the bearers of ill news. Not only from the battlefields where they had feasted but from the places of execution as well, a well-laid table for the ravens, hence the German term “Galgenvogel”, gallows’ bird, or “just Unglücksrabe”.

56 notes

·

View notes

Text

dude i wish i can see a full transcript of the test dept translation of y gododdin because i think its my favorite translation that sounds the best recited and i want to recite it to myself for fun but they didnt post their lyrics anywhere probably so that you have to just look up y gododdin yourself and figure it out. but the other translations arent as good and i dont speak welsh

#i mean probably i just like it because 1. i like test dept's music 2. i heard it first#3. they repeat whatever they want however many times they want whenever they want to make it flow (which i could do too)

7 notes

·

View notes

Note

I do want to ask, what version of the Arthurian tales you prefer most? Do you lean towards Welsh mythology like the Y Gododdin or Geoffrey's writings or Chrétien's works most? Or is it a mixture of different things and your own ideas?

- 🌟

hi!! thank you for the ask!!!!

i think as far as the actual texts i like most i lean towards chrétien’s works, i love the way he writes!!! i think it’s very funny that he seems a little biased toward gawain, especially in story of the grail. and i just love knight of the cart so much.

as far as the version of the tale, i do kinda like to mix it up and create my own mish-mash of lore! like, seneschal kay with his fire powers from the mabinogi and stuff like that. and i use the name geraint instead of erec, but also lancelot and gareth are there. my brain is running at like 2fps right now so apologies for the very Vague thoughts, but yeah!

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

What does your Muse’s Name Mean?

Arthur

Gender: Masculine

Usage: English, French, German, Dutch, Norwegian, Danish, Swedish, Welsh Mythology, Arthurian Romance

Pronounced: AHR-thər(English) AR-TUYR(French) AR-tuwr(German) AHR-tuyr(Dutch)

Meaning and history:

The meaning of this name is unknown. It could be derived from the Celtic elements *artos "bear" (Old Welsh arth) combined with *wiros "man" (Old Welsh gur) or *rīxs "king" (Old Welsh ri). Alternatively it could be related to an obscure Roman family name Artorius.

Arthur is the name of the central character in Arthurian legend, a 6th-century king of the Britons who resisted Saxon invaders. He may or may not have been based on a real person. He first appears in Welsh poems and chronicles (perhaps briefly in the 7th-century poem Y Gododdin and more definitively and extensively in the 9th-century History of the Britons) However, his character was not developed until the chronicles of the 12th-century Geoffrey of Monmouth. His tales were later taken up and expanded by French and English writers.

The name came into general use in England in the Middle Ages due to the prevalence of Arthurian romances, and it enjoyed a surge of popularity in the 19th century. Famous bearers include German philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer (1788-1860), mystery author and Sherlock Holmes creator Arthur Conan Doyle (1859-1930), and science-fiction author Arthur C. Clarke (1917-2008).

tagged: @eternitycyber (thanks for tagging the boy)

tagging: @eris-the-phantom-thief , @illuminaryxmuses , @universestreasures , @violetueur , @brighterburn , steal this if you wanna

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

did u know that the poem Y Gododdin is the first welsh poem that survived (half in old Welsh half in mid Welsh) and and AND hear me out - a certain Arthur is mentioned. Yes it's probably the first mention of King Arthur. Going INSANE

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Read All the Arthurian Literature!

I was originally going to do this chronologically, but after pulling the enormous list of classic texts from @fuckyeaharthuriana's Arthurian List of Everything, I quickly abandoned that idea.

Instead, I'm going to start with the "core texts" in chronological order... more or less. I'll fill in the remaining literature over time if I stick with this project long enough. Core texts are bolded. These are the very influential, foundational texts that Arthurian literature built on over time, and that modern Arthuriana derives from. (What's a "core text" is debatable; I'm bolding the texts that I've most often seen recommended across the internet.)

This is my tracking sheet for what I've acquired, what I've read, and what I have left to read, with a link to the tag associated with that text where you can find my reactions, thoughts, and quotes from the text. Currently a shortlist, with additional texts from the complete list added in as I read them.

✓ 540 - Excerpt from De Excidio Britanniae / The Ruin of Britain, by Gildas. Translated by Michael Faletra (appendix in Faletra's History of the Kings of Britain)

□ The rest of De Excidio Britanniae, by Gildas. (Probably not going to bother with this.)

✓ 600 - Y Gododdin. Translated by Gillian Clarke

✓ 828 - Excerpt from Historia Brittonum, by pseudo-Nennius. Translated by Michael Faletra (appendix in Faletra's History of the Kings of Britain)

□ The rest of Historia Brittonum, by Nennius. (Probably not going to bother reading this.)

□ 1000-1185 - The Lives of Saints (various saints with Arthurian content in their stories) - This is not what I'd call a core text, I'll probably skip most of them for now, but I already read excerpts in Faletra's appendices and I wanted credit for it.

□ 1000 - Life of St. Illtud

□ 1000 - Life of St. Cadoc, by Lifras of Llancarfan

□ 1019 - Legenda Sancti Goeznovii (Arthur is mentioned as being "recalled from the actions of the world" and not much more, probably skippable)

□ 1100 - Life of St. Padarn (only a brief mention of Arthur and Caradoc, probably skippable)

□ 1100 - Life of St. Efflam

✓ 1130 Excerpt from Vita Gildae / Life of St Gildas, by Caradoc. Translated by Michael Faletra (appendix in Faletra's History of the Kings of Britain)

□ The rest of Vita Gildae / Life of St Gildas. Translated by Hugh Williams because it's literally the only one I can find.

□ 1185 - The Life of Kentigern, by Jocelyn of Furness

✓ 1100 - The Lais of Marie de France. Translated by Claire Waters (newest recommended translation I could find, from 2018 by Broadview Press which was the selling point for me because they're amazing; has translation on one page and the old French on the other).

✓ 1138 - Historia regum Britanniae / History of the Kings of Britain, by Geoffrey of Monmouth. Translated by Michael Faletra (appendix in Faletra's History of the Kings of Britain)

✓ 1125 - Excerpt from Gesta Regum Anglorum / The Deeds of the Kings of the English by William of Malmesbury. Translated by Michael Faletra (appendix in Faletra's History of the Kings of Britain)

□ The rest of Gesta Regum Anglorum, by William of Malmesbury. (Probably not going to bother reading this.)

✓ 1150 - Vita Merlini / Life of Merlin, by Geoffrey of Monmouth. Translated by Michael Faletra (appendix in Faletra's History of the Kings of Britain)

□ 1155 - Roman de Brut, by Wace. (Might skip this, not sure.)

□ 1170 - Tristan, by Thomas of England

□ 1170-81 - Romances of Chretien de Troyes

□ 1170 - Erec and Enide. Translated by Ruth Harwood Cline (the only one who's done verse translation instead of prose)

□ 1176 - Cliges. Translated by Ruth Harwood Cline

□ 1177 - Lancelot: the Knight of the Cart. Translated by Ruth Harwood Cline

□ 1177 - Yvain: the Knight of the Lion. Translated by Ruth Harwood Cline

□ 1181 - Perceval: the Story of the Grail. Translated by Nigel Bryant (because it's the only edition that also includes all the Continuations)

□ 1185 - Le Bel Inconnu / Fair Unknown, by Renaut de Bage

□ 1191 - Poems of Robert de Baron. Translated by Nigel Bryant (because it's the only edition I could find that included all the poems in one volume)

✓ 1191 - Excerpt from Itinerarium Kambriae / The Journey Through Wales, by Gerald of Wales. Translated by Michael Faletra (appendix in Faletra's History of the Kings of Britain)

□ The rest of Itinerarium Kambriae. Probably skippable.

✓ 1200 - Excerpt from De Principis Instructione Liber / The Education of Princes, by Gerald of Wales. Translated by Michael Faletra (appendix in Faletra's History of the Kings of Britain)

□ The rest of De Principis Instructione Liber. Probably skippable.

□ 1200 - Wigelois, by Wirnt von Grafenberg

□ 1200 - Conti di Antichi Cavalieri (Conto di Brunono e di Galeotto suo figlio) - this is not a core text, I just want all the Galehaut content I can get

□ 1200 - First Continuation of Chretien's Perceval, by Unknown / Wauchier of Denian. Translated by Nigel Bryant (because it's the only edition I could find that includes Chretien's Perceval plus all the Continuations)

□ 1200 - Second Continuation of Chretien's Perceval, by Gauchier of Donaing. Translated by Nigel Bryant (because it's the only edition I could find that includes Chretien's Perceval plus all the Continuations)

□ 1200 - Lanzelet, by Ulrich von Zatzikhoven (date debated, may be much earlier). Translated by Thomas Kerth (literally the only version I could find in hardcopy) (this isn't a core text, but I really like Lancelot, so I'm reading it). Currently reading it, it’s not as entertaining as I’d hoped, have bounced off of it and will come back to it later.

□ 1200 - Perlesvaus / High Book of the Grail. Nigel Bryant's translation, acquired.

□ 1200 - Tristan, by Beroul

□ 1200 - Tristan, by Gottfried von Strassburg

□ 1210 - French Vulgate / Lancelot-Grail / Prose Lancelot. Translated by a team of scholars led by Norris J Lacy (it's 2024 and I'm still into Arthuriana so I have acquired this!).

□ 1230 - Third Continuation of Chretien's Perceval, by Manessier. Translated by Nigel Bryant (because it's the only edition I could find that includes Chretien's Perceval plus all the Continuations)

□ 1230 - Fourth Continuation of Chretien's Perceval, by Gerbert de Montreuil. Translated by Nigel Bryant (because it's the only edition I could find that includes Chretien's Perceval plus all the Continuations)

□ 1230 - Prose Tristan, Luce de Gat

□ 1230 - Post Vulgate. Translated by a team of scholars led by Norris J Lacy (it comes in a set with the Lancelot-Grail)

□ 1250 (or 1000) - Welsh Triads

✓ Excerpt translated by Michael Faletra (appendix in Faletra's History of the Kings of Britain)

□ 1300 - Black Book of Carmarthen. Translated by Meirion Pennar because I can't find any other translation in hardcopy.

✓ ~950? What Man is the Gatekeeper? / Pa gur yw y porthor? Translated by Michael Faletra (appendix in Faletra's History of the Kings of Britain)

✓ ~1100? Afallennau / The Apple Trees. Translated by Michael Faletra (appendix in Faletra's History of the Kings of Britain)

□ 1300 - La Vendetta Che fe Messer Lanzelloto de la Morte di Miser Tristano (Lancelot avenging Tristan; not a core text, but sounds very relevant to my interests)

□ 1300 (or 900) - Book of Taliesin. Translated by Lewis & Rowan because it’s the most recent translation and I can’t find any comparisons between translations, or recommendations about translations, so I’m going with most recent and hoping that works.

□ 1300 - The Stanzaic Le Morte Arthur. Maybe Sharon Kahn’s verse translation? Alternatively, Larry Benson’s because it comes with the Alliterative Morte.

□ 1382 - The Mabinogion. Translated by Sioned Davies. (Acquired. Started reading it and finished book 1 almost by accident.)

□ 1400 - Alliterative Morte Arthure. Probably Simon Armitage’s translation? Alternatively Larry Benson’s translation because it comes with the Stanzaic Mort?

□ 1400 - Sir Gawain and the Green Knight. (I have Tolkien's translation in ebook format, might go with a different translator though.)

□ 1400 - Syre Gawene and the Carle of Carlyle

□ 1450 - The Wedding of Sir Gawain and Dame Ragnell

□ 1485 - Le Morte Darthur, by Thomas Malory. Translated by Keith Baines because it's apparently the least tedious of the translations. (Acquired.)

□ 1500 - The Grene Knight

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Fyrthœr bookes fyr the færestę mayden tew consydre (@lapokinanaz)

1. Troilus & Cressida (Shakespeare; tho’ there’s also a rendition by Chaucer)

2. Hereward the Wake (Anglo-saxon hero legend)

3. Cúailnge (Celtic hero legend)

The above two however may be included in a volume of British/Celtic legends, so be wary in your query.

4. Y Gododdin

5. Bulfinch’s Mythology

6. The Howard Collector

7. A volume of Lewis Carrol (including Jabberwock)

8. The Metamorphosis and other stories (Kafka)

9. The One (Rick Veitch, comic)

A surprising Christian allegory

10. A Dictionary of Angels (Gustav Davidson)

11. a volume of ancient English poetry 🏴

1 note

·

View note

Text

Hero, shield firm below his freckled forehead,

His stride a young stallion's.

There was battle's din, there was flame,

There were keen spears, there was sunlight,

There was crow's food, a crow's profit.

Before he was left at the ford,

As the dew fell, graceful eagle,

With the wave spreading beside him.

Y Gododdin, XXIV.

0 notes

Text

idylls of the king off tallahassee makes me think of the arthur mention in y gododdin so arthur and guinevere are my alpha couple

0 notes