#william wilberforce

Text

Ioan Gruffudd as William Wilberforce in Amazing Grace

#ioan gruffudd#amazing grace#william wilberforce#a gruffudd smile a day keeps the doctor away#come on tumblr did you eat my tags?#I don't think I've posted that one before#my gif folder is a mess I'm sorry#my gifs

99 notes

·

View notes

Text

I do not agree w/all my friends on every issue. I don't have to. I don't have to agree w/them on even most issues. All I am called to do by the Creator who put the divine spark of life in all of us is to love, to see beyond the surface. I do not walk away from people. I do not turn my back. I will not change my principles, or reject someone because I don't agree with them. I have been in that position, lost and alone, and I WILL NOT be pressured or guilted into doing that to anyone else. I love, I accept, I have open arms to welcome anyone of any religion, gender, belief system, whatever the fuck you are, come on in...but know that everyone else is welcome too...and everyone is loved. And if you walk away, that is your choice. Accepting you back afterwards...well, that is mine. And while I am a forgiving person, that does not mean blindly trusting.

As it harm none, do as ye will.

I have found the paradox, that if you love until it hurts, there can be no more hurt, only love. - Mother Teresa

Let it not be said that I was silent when they needed me. - William Wilberforce.

#cj speaks#love#friendship#all are welcome#all are loved#I am who I am#your acceptance is not required#no judgment zone#i will not be silenced#as it harm none..do as ye will#love until it hurts#mother teresa#william wilberforce#hate changes no one's mind#rejection changes no one's mind#we don't have to agree#writeblr#writeblr community#writeblr connect

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

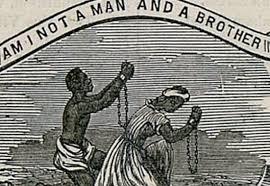

It was bound to happen sooner or later: a guest on the BBC’s Antiques Roadshow presented an artefact, which derived from the slave trade – an ivory bangle.

One of the programme’s experts, Ronnie Archer-Morgan, himself a descendant of slaves, said that it was a striking historical artefact but not one that he was willing to value.

‘I do not want to put a price on something that signifies such an awful business,’ he said.

It’s easy to understand how he feels. The idea of people profiting from the artefacts left over from slavery is distasteful.

Yet, as Archer-Morgan said, it is not that the bangle has no value: it has great educational value.

It should be bought by a museum and displayed in order to demonstrate the complex nature of slavery and as a corrective to the narrative that slavery was purely a crime committed by Europeans against Africans.

The bangle was, it seems, once in the possession of a Nigerian slaver who was trading in other Africans.

It’s a reminder that slavery was rife in Africa long before colonial government.

It could also remind us that, though slavery was a global institution, the country that led the world in the rebellion against this barbarism – and played a bigger role than perhaps anyone else in its eradication – was the United Kingdom.

Britain did not invent slavery.

Slaves were kept in Egypt since at least the Old Kingdom period and in China from at least the 7th century AD, followed by Japan and Korea.

It was part of the Islamic world from its beginnings in the 7th century.

Native tribes in North America practised slavery, as did the Aztecs and Incas farther south.

African traders supplied slaves to the Roman empire and to the Arab world. Scottish clan chiefs sold their men to traders.

Barbary pirates from north Africa practised the trade too, seizing around a million white Europeans – including some from Cornish villages – between the 16th and 18th centuries.

It was in fear of such pirates that the song ‘Rule Britannia’ was written: hence the line that ‘Britons never ever ever shall be slaves.’

Even slaves who escaped their masters in the Caribbean went on to take their own slaves.

The most concerted campaign against all this was started by Christian groups in London in the 1770s who eventually recruited William Wilberforce to their campaign, and parliament went on to outlaw the slave trade in 1807.

British sea power was then deployed to stamp it out.

The largely successful British effort to eradicate the transatlantic slave trade did not grow out of any kind of self-interest.

It was driven by moral imperative and at considerable cost to Britain and the Empire.

At its peak, Britain’s battle against the slave trade involved 36 naval ships and cost some 2,000 British lives.

In 1845, the Aberdeen Act expanded the Navy’s mission to intercept Brazilian ships suspected of carrying slaves.

Much is made about how Britain profited from the slave trade, but we tend not to hear about the extraordinary cost of fighting it.

In a 1999 paper, US historians Chaim Kaufmann and Robert Pape estimated that, taking into account the loss of business and trade, suppression of the slave trade cost Britain 1.8 per cent of GDP between 1808 and 1867.

It was, they said, the most expensive piece of moral action in modern history.

The cost of fighting the slave trade cancelled out much, if not all of Britain’s profits from it over the previous century.

There are those who continue to demand reparations for slavery from the UK government and other western powers, yet they rarely, if ever, acknowledge Britain’s role in all but eradicating the evil of the transatlantic slave trade, a cause on which we spent the equivalent of £1.5 billion a year for half a century.

Britain’s role in hastening slavery’s extinction is a remarkable achievement.

It’s astonishing that we have forgotten it almost entirely in the 21st century.

It would be difficult to find anyone in the world whose ancestral tree does not somewhere extend back to a slave-trader.

Huge numbers of us, too, will have been partly descended from slaves.

Britain should not minimise or deny the extent to which it traded slaves to the colonies in the early days of Empire.

But it is also important to remember the thousands who served and died with the West Africa Squadron while seizing 1,600 slave ships and freeing some 150,000 Africans.

We must examine and remember everything about the history of the slave trade, including the forces – moral and military – that eventually brought it to an end.

It’s profoundly worrying that slavery evolved to be a near-universal phenomenon among human societies and inspiring that it came to be all but eradicated within a single human lifespan.

#Britain#slave trade#Antiques Roadshow#Ronnie Archer-Morgan#ivory bangle#artefacts#Rule Britannia#William Wilberforce#Aberdeen Act#slavery#suppression of slave trade#moral action#transatlantic slave trade#BBC

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

You may choose to look the other way but you can never say again that you did not know.

William Wilberforce

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

"And, sir, when we think of eternity, and of the future consequences of all human conduct, what is there in this life that should make any man contradict the dictates of his conscience, the principles of justice, the laws of religion, and of God?"

William Wilberforce

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

William Pitt's sleeping habits

I always found the private Pitt much more interesting than the political Pitt and probably one of the first aspects to really capture my attention about Pitt’s private life were his sleeping habits. I find sleep to be utterly fascinating, both from a medical/biological point of view but also from a personal point of view. And while Pitt’s sleep habits were nothing unheard of, there still were some peculiarities.

Pitt often was happy to get out of London, even if only for a short time, and to enjoy some peace and quiet in the country. Holwood House was a dearly beloved retreat of his. This desire to be out of the bustling city of London also extended to Pitt’s sleeping arrangements. William Wilberforce later wrote:

In the spring of one of these years Mr. Pitt, who was remarkably fond of sleeping in the country, and would often go out of town for that purpose as late as eleven or twelve o'clock at night, slept at Wimbledon for two or three months together. It was, I believe, rather at a later period that he often used to sleep also at Mr. Robert Smith’s house at Hamstead.

A. M. Wilberforce, editor, Private Papers of William Wilberforce, T. Fisher Unwin, London, 1897, p. 49.

Wimbledon was Wilberforce’s villa – he was one of the few of Pitt’s friends at the time to actually own a house.

But a country house was not the only place where Pitt could fall asleep, far from it. Although being Prime Minister is an important and dignified position, Pitt would often fall asleep in the House of Commons itself. Richard Rush, son of Benjamin Rush, American physician, and signer of the Declaration of Independence, was the American Minister to the court of St. James. In his papers he retells this story of a conversation he had once during a dinner:

He [William Wilberforce] spoke of Mr Pitt. They had been at school together. He was remarkable, he said, for excelling in mathematics; there was also this peculiarity in his constitution, that he required a great deal of sleep, seldom being able to do with less than ten or eleven hours; he would often drop asleep in the House of Commons; once he had known him do so at seven in the evening and sleep until day-light.

Richard Rush, Residence at the Court of London, third Edition, Hamilton, Adams & Co, London, 1872, p. 175

We can further read in the diaries of Charles Abbot:

March 17, 1796.—Dined at Butt’s with the Solicitor-General and Lord Muncaster. Lord Muncaster was an early political friend of Mr. Pitt, and our conversation turned much upon his habits of life. Pitt transacts the business of all departments except Lord Grenville’s and Dundas’s. He requires eight or ten hours’ sleep.

Earl Stanhope, The Life of the Right Honourable William Pitt, Vol. 3, John Murray, London, 1862, p. 4.

When you, for example read through Wilberforce’s diaries and journals, you will see many instances where he mentions that he either got no sleep at all or only slept very poorly. It was different with Pitt. When he was asleep, he normally could sleep on with neither internal nor external factors disturbing him. His ability to sleep on was apparently so outstanding that many of his contemporaries, Bishop Tomline and William Wilberforce for example, found it worthwhile to mention the few times that something disturbed Pitt’s sleep:

This was the only event of a public nature which I [Bishop Tomline] ever knew disturb Mr. Pitt’s rest while he continued in good health. Lord Temple’s resignation was determined upon at a late hour in the evening of the 21st, and when I went into Mr. Pitt’s bedroom the next morning he told me that he had not had a moment’s sleep.

Earl Stanhope, The Life of the Right Honourable William Pitt, Vol. 1, John Murray, London, 1861, p. 158.

The context of this scene was the resignation of Lord Temple as Secretary of State shortly after accepting the office. Pitt had really wanted Temple to be Secretary of State and was rather dismayed that he had resigned so quickly.

There were indeed but two events in the public life of Mr. Pitt, which were able to disturb his sleep—the mutiny at the Nore, and the first open opposition of Mr. Wilberforce; and he himself shared largely in these painful feelings.

R. I. Wilberforce, S. Wilberforce, The Life of William Wilberforce, Vol. 2, John Murray, London, 1833, p. 71.

Pitt himself told Lord Fitzharris that there was only one event that had kept him awake at night:

Lord Fitzharris says in his note-book:—‘‘One day in November, 1805, I happened to dine with Pitt, and Trafalgar was naturally the engrossing subject of our conversation. I shall never forget the eloquent manner in which he described his conflicting feelings when roused A the night to read Collingwood’s despatches. He observed that he had been called up at various hours in his eventful life by the arrival of news of various hues; but whether good or bad, he could always lay his head on his pillow and sink into sound, sleep again. On this occasion, however, the great event announced brought with it so much to weep over as well as to rejoice at, that he could not calm his thoughts; but at length got up, though it was three in the morning.”

Earl Stanhope, The Life of the Right Honourable William Pitt, Vol. 4, John Murray, London, 1862, p. 334.

The more you read about Pitt, especially in the private papers of his contemporaries and intimate friends, the more you see accounts of how often somebody mentions that he either roused him from his sleep him or found him to be still asleep/in bed. When Addington told Pitt that the Kings health was steadily mending – he was asleep. When the news of Trafalgar reached him – he was asleep. There is one letter from Admiral Nelson to Emma Hamilton. In it he describes that he had wanted to meet with William Pitt but when he arrived at his accommodation, he was told that Pitt was still asleep.

The older he got, the more sleep Pitt seemed to require and during his last illness, his ability to sleep was greatly impaired. Still, at the end of the day, his sleeping habits can be summed up by this quote from his niece Lady Hester Stanhope:

(…) for he was a good sleeper

Charles Lewis Meryon, Memoirs of the Lady Hester Stanhope, As related by Herself in Conversations with her Physician, Volume 2, Second Edition, London, 1845, p.58.

#william pitt#william pitt the younger#william wilberforce#sleep#lady hester stanhope#charles lewis meryon#bishop tomline#richard rush#english history#benjamin rush#lord temple#lord fitzharris#charles abbot#earl stanhope#admiral nelson#henry addington

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

#david collings#william wilberforce#1975#great performances#words fail me#he's wonderful#fight against slavery e3-6#DVD MUCH NEEDED

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Argentina tiene una oportunidad única de salir adelante y dejar atrás la agenda empobrecedora de la Internacional Socialista. Es momento de entender que un Estado que regala y emite no es un Estado efectivo, haciendo pagar esos errores a los menos favorecidos.

Interesante punto de vista en este video sobre los cambios que Argentina debe efectuar de manera urgente .

https://x.com/dolar_sabroso/status/1745904388130865160?t=078aD1zDHJ775zbwdHdzPg&s=09

#alberdi#argentina#buenos aires#libertad#milei#viralpost#politics#cfk#javier milei#karina milei#gobierno abierto#economia#politica argentina#ajuste#luis lacalle pou#william wilberforce#liberalismo#libertarios

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

An Act of Parliament freed 800,000 slaves on this day in 1834

#Emancipation Day#British Empire#1 August 1834#slavery#UK#abolitionist movement#William Wilberforce#liberation#Caribbean#West Indies#Act of Parliament#Victoria & Albert

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

📍Hull, Yorkshire

#hull#yorkshire#land of green ginger#city#architecture#william wilberforce#photography#April 2022#mine

3 notes

·

View notes

Note

Headcanons for teenage Henry form forever, meeting midshipmen Horatio and Archie? I mean they were all alive in the 1790s.

Actually I headcanon that Horatio and Henry are one and the same :) One might argue that it's silly, but is it? What if Horatio, young privileged boy becomes Navy officer for a while. Then as he was traveling on one of his father's ships to try and free the slaves, he gets shot. He comes back to life, finds his way home. His wife sends him to the asylum. He escapes, changes name, and starts a new life as Henry Morgan. He starts studying medicine, becomes a doctor.

See, it all works out :)

Alternatively, Henry could have done his national service with Horatio and Archie on the Indie :)

Oh and of course Henry, as a young idealist man, before his first death, was passionated about William Wilberforce and he went to listen to him talk at the Chamber a few times. His father is actually the one who introduced him to Wilberforce.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

It's God. I have 10,000 engagements of state today but I would prefer to spend the day out here getting a wet arse, studying dandelions and marveling at... bloody spiders' webs.

- William Wilberforce, Amazing Grace

#amazing grace#amazing grace movie#william wilberforce#ioan gruffudd#dandelions and spiderwebs#quotes#about time vibes

12 notes

·

View notes

Quote

William Wilberforce escreveu em "Cristianismo verdadeiro":

Acima de tudo, avaliem seu progresso por meio de sua experiência com o amor de Deus e do exercício desse amor diante dos homens. [...]

Em contraste, é servil, básica e mercenária a noção da prática cristã entre os cristãos nominais. Eles não dão nada além daquilo que não ousam reter. Eles não se abstêm de nada, a não ser daquilo que não devem praticar. Quando você lhes declara a qualidade duvidosa de qualquer ação, e a consequente obrigação de evitá-la, eles respondem, no espírito de Shylock, que "não podem encontrá-la na fronteira".

Em resumo, eles conhecem o cristianismo somente como um sistema de restrições, posto à parte de qualquer princípio liberal ou generoso, considerado quase inadequado para os relacionamentos sociais da vida, e apropriado somente para as paredes soturnas de um monastério no qual o confinariam.

Mas os verdadeiros cristãos se consideram não como se estivessem satisfazendo a um rigoroso credor, mas como se estivessem pagando uma dívida de gratidão. Não veem seu compromisso como um retorno limitado de obediência forçada, mas como a medida ampliada e liberal de um serviço voluntário.

Livro “Paixão e Pureza”, de Elizabeth Elliot.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

The founder and leader of the anti-slavery movement, William Wilberforce, specifically ruled women out of the campaign: 'For ladies to meet, to publish, to go from house to house stirring up petitions – these appear to me, proceedings unsuited to the female character as delineated in Scripture.'

"Normal Women: 900 Years of Making History" - Philippa Gregory

#book quotes#normal women#philippa gregory#nonfiction#founder#leader#anti slavery#slave trade#william wilberforce#campaign#exclusion#sexism#meeting#publishing#doorknocking#petitions#scripture#bible#justification#christianity

1 note

·

View note

Quote

And, sir, when we think of eternity, and of the future consequences of all human conduct, what is there in this life that should make any man contradict the dictates of his conscience, the principles of justice, the laws of religion, and of God?

William Wilberforce

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

(…) to open yourself full and without reserve to one, who, believe me, does not know how to separate your happiness from his own.

William Pitt to William Wilberforce, December 2, 1785

Around this time, Wilberforce had a change in his religious opinions and because of this, toyed with the idea of leaving politics behind. He wrote the same to Pitt and was answered by this letter where Pitt voiced his doubts but more importantly, also expressed his great affection for Wilberforce and reminded them, that they could talk openly about everything. Pitt’s letter was followed by a visit from Pitt to Wilberforce and a two-hour long conversation.

A. M. Wilberforce, editor, Private Papers of William Wilberforce, T. Fisher Unwin, London, 1897, pp. 12-15.

#quote#letters#1785#william wilberforce#william pitt#william pitt the younger#british history#religion

6 notes

·

View notes