#why is it 50 degrees in december (global warming???)

Text

Happy holidays! Have some frogs 🐸

(no reposts; reblogs appreciated)

#my art#artists on tumblr#art#doodles#fanart#star wars#grogu#the mandalorian#lineless art is so fun#i should definitely do that more#the thought process went: grogu is green…green is a holiday color#the logical hoops i jump through to draw grogu 24/7 365#poor mando got ornamented#also where is the snow#why is it 50 degrees in december (global warming???)

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

my Dad will say things every once in a while about how it's still cold so global warming clearly isn't happening or at least isn't that bad

and I'm just sitting there freaking out cause "don't you remember when it was like 40s to 50s in October, don't you remember cold halloweens and the dark October blue skies" "Don't you remember when it would start getting a little chilly in September" "Don't you remember when by this time of the year there would be large parts of sidewalk covered in frost and how we'd have to warm up the car and scrape off the frost every single day and every time we opened the door the sharpest gust of cold air would come through and reach the kitchen" "Don't you remember when all that happened in late November" Don't you remember when we had reason to maybe hope for snow for at least a week and it wasn't just accepted that the only snow we got would last for three hours" "Don't you remember when it was unreasonable to ever expect a day when I could wear a tank top in December, when I needed five blankets and my feet would still be chilly at night"

We've never had especially cold winters where I live but we would have freezing temperatures fairly often. I remember because I always thought it was so annoying that the freezing and below temperatures would almost only come on the days with 0 chance of precipitation. Now we get 90 degrees for all of September and the only reason why the temperature would ever dip below maybe 35 is if we get an especially bad cold front.

1 note

·

View note

Text

grave concerns over the hazards of global warming

Once people started to realize my history and what I do with my life, I guess they started to accept it and call me that. I am still amazed at the video's reach. And yes, I use a bit of self deprecating humor in what I do. The contemporary hip hop outfits are lots extra cheap jerseys various as well as the brands like Gucci or even the Louis has manufactured some desirable contributions in the men hip hop apparel. Consequently the hip hop clothing is now a preferred trend throughout the world. The loose fitting shirts, T shirts, tight jeans, trousers and jackets are some favorite apparel.

Other than that, Danbury let me remind you, it's the second largest public high school in nfl jerseys Connecticut is pretty darn average. Sports like field hockey and baseball have their years, but others have been marginal (at best) for quite some time. The football team hasn't had a winning season since 2004 and the boys basketball team is 11 29 in its wholesale jerseys from china last two seasons..

One thing is clear. If we're grading on a curve, Barack Obama ranks near the top, just below FDR. In changing course, getting bold things done, setting a tone, lifting our spirits and confidence, we haven't seen anything like this since Roosevelt. Although there may be more Filipinos in Vancouver or cheap nfl jerseys Toronto, they are spread out over a much larger geographic area, making it harder for new www.cheapjerseysofchina.com arrivals to plug into the local community. In Manitoba, newly arrived Filipinos easily find a support system that includes Cheap Jerseys china Filipino culture, food, music, news and services. The cost of housing and other necessities is also much more affordable in Manitoba, a big draw for many Filipinos..

Mr. Kenneth A. Lynch is Senior Vice President, Chief Risk Officer of the company. The 2013 first round draft pick converted on a wraparound attempt, beating an unsuspecting Ondrej Pavelec to give the Preds a 1 0 lead just 3:48 in to the game.That lead would be short lived, however, as the Jets made it 1 1 just 22 seconds later with Chris Thorburn's first goal of the year. Thorburn redirected Cheap Jerseys from china a Mark Stuart shot from Cheap Jerseys china the point that beat Preds netminder Carter Hutton low.The Jets spent four of the next six minutes a man down, killing off back to back penalties to keep the score even. Dustin Byfuglien was cheap nfl jerseys called for a slash, followed by a goaltender interference call on Mark Scheifele.The Jets closed out the period with a power play of their own, the first in the game for Winnipeg, but they were unable to convert, registering just one shot on net.Nashville got off to another hot start in the second period this time is only took 42 seconds to take a 2 1 lead over the home team.

The whole concept of global warming revolves around the fact that the Earth is getting warmer, which according to the proponents of this concept is attributed to anthropogenic or human induced causes. While environmentalists express grave concerns over the hazards of global warming, skeptics seem least interested. They argue that wholesale jerseys from china the predictions on which these environmentalists and scientists are relying are made by computer simulated climatic models which are far from reliable..

'It's my data, and I felt I should be entitled to that,' she says. 'I contacted members of staff to collect it but before I could get any, Shane phoned me and said, "How dare I call his staff" for my information. A meeting we had scheduled to further explain why my www.cheapjerseys-football.com contract hadn't been renewed was cancelled.'.

Folks could line up after the game for player autographs. And we were all invited to join the players at the San Francisco Zoo the next night for some sort of hockey/zoo activity. It occurred to me that minor league athletes must be tasked wholesale nfl jerseys from china with participating in lots of awkward marketing events.

Animals working in a circus are tortured all their lives. They are forced to perform on stage for an audience who is least bothered of their pain. Wild animals like tigers, lions, elephants, etc., are forced to perform shows and look fierce to keep the audience captured with awe.

With the past of 2010, we welcome for the new beginning of 2011. Hey, girls, it seems it the time to update your wardrobe with New Year dresses and 2011 spring dresses. No matter what you like to wear and what the styles you like, your wardrobe is never wholesale jerseys from china complete without a couple of these sexy casual dresses.

Most aren winners, so they cranky. I arrived just after the running of race 8, and I got to enjoy one particular drunk who felt the jockey of the losing horse he bet on had phoned it in yelling and cursing derisively at the jockey as he slunk back to the paddock area. Aqueduct has an overhang that allows fans a balcony right over the paddock area, so this guy had an unobstructed stage to hurl abuse down on the Dominican jockey who probably didn understand the words, but clearly got the sentiment..

It was a very interesting tournament for me. I have always been able to get people to step up and push themselves. But understanding what I have to do nfl jerseys to get them to push themselves was the big learning part for me. Nike treasurer Blair (DonBlair) informed source for this article analysts when it comes to June during the past year, this agency by grand toward end of the money yr in the Cheap Jerseys china first city district arrant space could be fell 50 percent of an area, having said that the physical state of affairs in the dead can be obscene profit fushia that will help forty seven% out of 46.2% last year. Nike and cautioned "advice overhead augment, employing complimentary time unit of one's des affaires year termination around December, this agency coarse perimeter degree then a lot more www.cheapjerseyssalesupply.com than in 2009. Greek deity announced general profit surge can be the biggest source of entire sales and profits multiply lessen typically the deal objects.

1 note

·

View note

Text

{REPORT}. Eat less meat: UN climate change report calls for change to human diet

The report on global land use and agriculture from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change comes amid accelerating deforestation in the Amazon.

Efforts to curb greenhouse gas emissions and the impacts of global warming will fall significantly short without drastic changes in global land use, agriculture and human diets, leading researchers to warn in a high-level report commissioned by the United Nations.

The special report on climate and land by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) describes plant-based diets as a major opportunity for mitigating and adapting to climate change ― and includes a policy recommendation to reduce meat consumption.

On 8 August, the IPCC released a summary of the report, which is designed to inform upcoming climate negotiations amidst the worsening global climate crisis. More than 100 experts compiled the report in recent months, around half of whom hail from developing countries.

“We don’t want to tell people what to eat,” says Hans-Otto Pörtner, an ecologist who co-chairs the IPCC’s working group on impacts, adaptation, and vulnerability. “But it would indeed be beneficial, for both climate and human health, if people in many rich countries consumed less meat, and if politics would create appropriate incentives to that effect.”

Researchers also note the relevance of the report to tropical rainforests, where concerns are mounting about accelerating rates of deforestation. The Amazon rainforests is a huge carbon sink that acts to cool global temperature, but rates of deforestation are rising, in part due to the policies and actions of the government of Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro.

Unstopped, deforestation could turn much of the remaining Amazon forests into a degraded type of desert, possibly releasing over 50 billion tonnes of carbon into the atmosphere in 30 to 50 years, says Carlos Nobre, a climate scientist at the University of São Paolo in Brazil. “That's very worrying,” he says.

“Unfortunately, some countries don’t seem to understand the dire need of stopping deforestation in the tropics,” says Pörtner. “We cannot force any government to interfere. But we hope that our report will sufficiently influence public opinion to that effect.”

Paris goals

While fossil fuel burning for energy generation and transport garners the most attention, activities relating to land management, including agriculture and forestry, produce almost a quarter of heat-trapping gases. The race to limit global warming to 1.5 degrees above pre-industrial levels ― the goal of the international Paris climate agreement reached in 2015 ― might be a lost battle unless the land is used in a more sustainable and climate-friendly way, the latest IPCC report says.

The report highlights the need to preserve and restore forests, which soak up carbon from the air, and peatlands, which release carbon if dug up. Cattle raised on pastures of cleared woodland are particularly emission-intensive, it says. This practice often comes with large-scale deforestation such as in Brazil or Colombia. Cows also produce large amounts of methane, a potent greenhouse gas, as they digest their food.

The report states with high confidence that balanced diets featuring plant-based, and sustainably-produced animal-sourced, food “present major opportunities for adaptation and mitigation while generating significant co-benefits in terms of human health”.

By 2050, dietary changes could free millions of square kilometers of land, and reduce global CO2 emissions by up to eight billion tonnes per year, relative to business as usual, the scientists estimate.

“It’s really exciting that the IPCC is getting such a strong message across,” says Ruth Richardson, the Toronto, Canada-based executive director at the Global Alliance for the Future of Food, strategic coalitions of philanthropic foundations. “We need a radical transformation, not incremental shifts, towards global land use and food system that serves our climate needs.”

Careful management

The report cautions that land must remain productive to feed a rising world population. Warming enhances plant growth in some regions, but in others ― including northern Eurasia, parts of North America, Central Asia and tropical Africa ― increasing water stress seems to reduce the rate of photosynthesis. So the use of biofuel crops and the creation of new forests― seen as measures with the potential to mitigate global warming ― must be carefully managed to avoid the risk of food shortage and biodiversity loss, the report says.

Farmers and communities around the world must also reckon with more intense rainfall, floods and droughts resulting from climate change warns the IPCC. Land degradation and expanding deserts threaten to affect food security, increase poverty and drive migration, the report says.

About a quarter of the Earth’s land area appears to suffer soil degradation already ― and climate change is expected to make things worse, particularly in low-lying coastal areas, river deltas, drylands, and permafrost areas. Sea level rise is adding to coastal erosion in some regions, the report says.

Industrialized farming practices are responsible for much of the observed soil erosion and pollution, says Andre Laperrière, the Oxford, UK-based executive director of Global Open Data for Agriculture and Nutrition, an initiative to make relevant scientific information accessible worldwide.

The report might provide a much-needed, authoritative call to action, he says. “The biggest hurdle we face is to try and teach about half a billion farmers globally to re-work their agricultural model to be carbon sensitive.“

Nobre also hopes that the IPCC’s voice will give greater prominence to land use issues in upcoming climate talks. “I think that the policy implications of the report will be positive in terms of pushing all tropical countries to aim at reducing deforestation rates,” he says.

Regular assessments

Since 1990, the IPCC has regularly assessed the scientific literature, producing comprehensive reports every six years, and special reports on specific aspects of climate change ― such as today’s― at irregular intervals.

A special report released last year concluded that global greenhouse-gas emissions which hit an all-time high of more than 37 billion tonnes in 2018 must sharply decline in the very near future to limit global warming to 1.5 degrees ― and that this will require drastic action without further delay. The IPCC’s next special report, about the ocean and ice sheets in a changing climate, is due next month.

Governments from across the world will consider the IPCC’s latest findings at a UN climate summit next month in New York. The next round of climate talks of parties to the Paris agreement will then take place in December in Santiago, Chile.

António Guterres, the UN’s climate secretary, said last week that it is “absolutely essential” to implement that landmark agreement ― and “to do so with an enhanced ambition”.

“We need to mainstream climate change risks across all decisions,” he said. “That is why I am telling leaders don’t come to the summit with beautiful speeches.”

https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-019-02409-7

#vegan#veganism#climate change#un report#meat eaters#carnists wake up#animal rights#ANIMAL RIGHTS NOT WELFARE

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

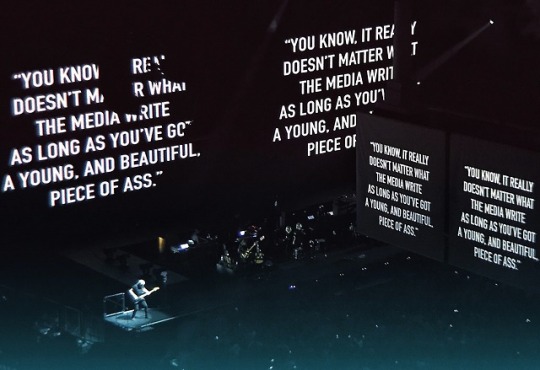

Absurd New York #91: Quotes by Trump Edition

In a world of slogans and soundbites, a brand jingle here and a sales pitch there, with oxymoronic pairings and definitions-be-damned, where search engine optimization is more sought after than content, and “liking” what’s written or uttered more lauded than actually comprehending it, are we becoming more anesthetized to words? Is the overload of all these things making us lazy and less willing to be critical of what passes before us? If so, isn’t that frightening? For all those who have the ability, and all those who still value language, the answer is emphatically YES.

In perhaps the most poignant part of Roger Waters’ current Us + Them Tour, Waters forces the issue. Near the end of Pink Floyd’s “Pigs (Three Different Ones),” the show’s massive LED screens flash a few of the things Donald Trump has said around the arena. Whether you care about Trump or not, whether you remember what he’s composed for public consumption or not, no matter: You’re challenged to think. You’re tasked with understanding his words and considering what they mean. Any maybe, just maybe, being detached from the image he cultivates for a moment you’ll be able to take a true measure of the man. Let’s give it a try.

----

“Im not schmuck. Even if the world goes to hell in a handbasket, I won’t lose a penny.”

On March 12, 1989, a piece by Glenn Plaskin appeared in the Chicago Tribune. The headline was “Trump: The People’s Billionaire.” Under the subheading “Tiny Trumps,” Plaskin wrote that “For R and R, in between tending to the little Trumps...Daddy raids corporations.” Also, having convinced banks and other investors to lend him money on the strength of his name alone--they gave him “instant credit” lines because they thought he had “unlimited collateral”--Trump went about building the Taj Mahal in Atlantic City for $725 million and purchasing the Plaza Hotel on Central Park South for $400 million. In reality, though, he only spent $50 million of his own money to buy the Taj. The remaining $675 million was “financed with uncollateralized junk bonds.” As far as the Plaza went, most of that $400 million was “borrowed.”

As Trump “reflected” during the interview, Plaskin recorded his words: “I’m not a schmuck. Even if the world goes to hell in a handbasket, I won’t lose a penny.” And he wouldn’t. When Trump bankrupted the Taj in 1991 and the Plaza too in 1992, he wasn’t left holding the worthless bonds or losing income from missed interest payments, his investors were. As far as the economic losses that got passed down to his employees, well, they weren’t his problem either. None of them did any damage to his bank account.

“A nation without borders is not a nation at all. We must have a wall.”

Trump first tweeted it out on July 14, 2015, and then again on July 28th as an attack on Jeb Bush, one of his then opponents in the Republican presidential primary. He’d double down with it again on September 17, 2016, only this time he including the hashtag “#AmericaFirst.” After being elected president, Trump decided to make his Twitter decree a cornerstone of national security policy. “Mexico will pay for the wall!” he tweeted. Of course it will, that’s why he’s spent the past year and a half trying to cajole Congress into giving him the funds.

So aside from sounding like Pink, the megalomaniac protagonist of Pink Floyd’s album “The Wall”--who, coincidentally, also wanted to barricade himself off from the rest of the world--what gives with Trump’s definition of what makes a nation? If you peruse the nearest map, you’d notice plenty of boundaries drawn around land masses across the globe. Don’t those markings designate countries? Is Canada, for example, somehow less a country because it hasn’t defined its sovereignty with a magnificent wall on the United States’ northern border?

“It’s freezing and snowing in New York--we need global warming!”

Although Trump has offered variations on this theme over the years, the original appeared via Twitter on November 7, 2012. Back then, the high temperature in New York was 41 degrees fahrenheit and the low 34. Sounds like just another pre-winter day in the Northeast, right?

Well, according to the folks at Custom Weather, not exactly. From 1985 to 2015, the average November day posted a high of 54 and a low of 41. Now, granted that particular November 7th was colder than normal, but it’s not as if the recorded high were zero and the low -15 as Trump would have had Twitter believe. Besides, his conclusion was wrong anyway. Given that November 7th’s readings were outliers, perhaps they were actually the predicted effect of a climate in flux. If so, he needn’t have clamored for global warming at all. It had already arrived.

“I was down there and I watched our police and our fireman, down on 7-Eleven, down at the World Trade Center, right after it came down.”

On April 18, 2016, that’s what Trump said at a presidential campaign stop at the First Niagara Center--today’s KeyBank Center--in Buffalo, NY. Yes, he inexplicably confused 9-11 with the Japanese-based chain store, sure, and didn’t bother to correct his mistake, but the core of what he proclaimed wasn’t true anyway.

On the morning of September 11, 2001, Trump actually called into the live broadcast on WWOR-TV Fox 5 Local News. (Although the station’s antenna was destroyed with the Twin Towers, its signal was being transmitted by other conduits.) He told anchors Alan Marcus and Brenda Blackmon that he saw the tragedy unfold from his apartment in Trump Tower at 5th Avenue and 56th Street--several miles from ground zero. Moreover, when Marcus asked “Did you have any damage, or did you--what’s happened down there?” he replied:

“40 Wall Street [a 71-story building he owned under the guise of “40 Wall Street, LLC”] actually was the second tallest building in downtown Manhattan, and it was actually, before the World Trade Center, was the tallest--and then, when they built the World Trade Center, it became known as the second tallest. And now it’s the tallest.”

Despite the horrific circumstances, he apparently couldn't resist promoting his interests. He even threw in an extra hyperbole. According to city property records, the 66-story building at 70 Pine Street--formerly known as the American International Building and the Cities Service Building--was actually 25 feet higher than his 40 Wall Street at the time. And still is.

Now 40 Wall Street didn’t suffer any damage in the terrorist attack, but the Trump Organization still applied for a $150,000 grant being offered to help small businesses in the aftermath. Known as World Trade Center Business Recovery Grants, they were given to businesses in Lower Manhattan with less than $8 million in annual revenue. However, in spite of generating $16.8 million that year, 40 Wall Street was still awarded a grant by the Empire State Development Corporation.

“You know, it really doesn’t matter what the media write as long as you’ve got a young, and beautiful piece of ass.”

While researching a story printed in the May 1991 edition of Esquire called “Donald Trump Gets Small,” Harry Hurt III was expertly entertained by the man himself. Trump took him on a VIP tour of the Trump Taj Mahal in Atlantic City and that apparently had the desired effect. When Hurt began his story, he scribed, “Given the kind of year he has had, Donald J. Trump might be forgiven a little ego candy.” What? Even then, the media seemed unfazed by what was happening under his shiny veneer.

At the time, the very casino Trump was showing to Hurt, the Taj Mahal, was going bankrupt. The Trump Castle, another Atlantic City casino, was destined for a similar fate until his father forestalled the inevitable. In December 1990, Fred Trump bought $3 million worth of chips at the Castle and left them in the casino cage so his son could use them pay off a bond payment on the property. Meanwhile, as Ivana Trump argued for more money from their divorce settlement, Marla Maples, the woman with whom Trump committed adultery while married to Ivana, was “pressuring him to propose in the wake of his highly publicized dalliance with model Rowanne Brewer.” But all that was seemingly of little consequence. Hurt remarked:

“One might think that the chill breath of potential collapse and enough tacky publicity to shame Pia Zadora might have taken the swagger out of Donald J. Trump. One would be wrong.

‘You know,’ [Trump] muses philosophically as we return to our ringside seats [in the Taj Mahal for the Ray Mercer-Frabcesci Damiani heavyweight fight], “it really doesn’t matter what they write as long as you’ve got a young and beautiful piece of ass.

‘But,’ he adds after a pause that suggests this is a distinction with a difference, ‘she’s got to be young and beautiful.’”

In other words, he’d never be held accountable by the media, by investors, by anyone if he could razzle-dazzle them with the women he attracted. Case and point: Hurt’s profile reads like a breezy apology for the economic havoc Trump was soon to unleash on Atlantic City. Something like “Give him a break, he’s too nice a guy to punish. After all, he gave me ringside seats, a few fun girls, and a comped penthouse suite for the night.”

-----

So how did you do? Did you measure the man by his words, or were you dumbfounded again by the show?

-----

(With Roger Waters and company at Barclays Center. Photos by Riff Chorusriff. Reading the Trump quotes pulled and projected under the watchful eye of Waters’ creative director/set designer Sean Evans. You can view more of Evans’ ingenuity on Instagram @deadskinboy. September 12, 2017.)

#absurd new york#trump quotes#trump words#roger waters#us + them tour#us and them tour#nyc music#barclays center#pacific park#sean evans#dave kilminster#jess wolfe#holly laessig#gus seyffert#jonathan wilson#bo koster#jon carin#ian ritchie#joey waronker#brooklyn#new york city#photographers on tumblr#riffchorusriff photography#riffchorusriff essay#donald trump#trump

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Regulations for ocean mining have never been formally established. The United Nations has given that task to an obscure organization known as the International Seabed Authority, which is housed in a pair of drab gray office buildings at the edge of Kingston Harbour, in Jamaica. Unlike most UN bodies, the ISA receives little oversight.

"Mining companies want access to the seabed beneath international waters, which contain more valuable minerals than all the continents combined."

History’s Largest Mining Operation Is About to Begin.... It’s underwater—and the consequences are unimaginable.

Story by Wil S. Hylton | Published January/February 2020 Issue | The Atlantic | Posted December 26, 2019 |

Unless you are given to chronic anxiety or suffer from nihilistic despair, you probably haven’t spent much time contemplating the bottom of the ocean. Many people imagine the seabed to be a vast expanse of sand, but it’s a jagged and dynamic landscape with as much variation as any place onshore. Mountains surge from underwater plains, canyons slice miles deep, hot springs billow through fissures in rock, and streams of heavy brine ooze down hillsides, pooling into undersea lakes.

These peaks and valleys are laced with most of the same minerals found on land. Scientists have documented their deposits since at least 1868, when a dredging ship pulled a chunk of iron ore from the seabed north of Russia. Five years later, another ship found similar nuggets at the bottom of the Atlantic, and two years after that, it discovered a field of the same objects in the Pacific. For more than a century, oceanographers continued to identify new minerals on the seafloor—copper, nickel, silver, platinum, gold, and even gemstones—while mining companies searched for a practical way to dig them up.

Today, many of the largest mineral corporations in the world have launched underwater mining programs. On the west coast of Africa, the De Beers Group is using a fleet of specialized ships to drag machinery across the seabed in search of diamonds. In 2018, those ships extracted 1.4 million carats from the coastal waters of Namibia; in 2019, De Beers commissioned a new ship that will scrape the bottom twice as quickly as any other vessel. Another company, Nautilus Minerals, is working in the territorial waters of Papua New Guinea to shatter a field of underwater hot springs lined with precious metals, while Japan and South Korea have embarked on national projects to exploit their own offshore deposits. But the biggest prize for mining companies will be access to international waters, which cover more than half of the global seafloor and contain more valuable minerals than all the continents combined.

Regulations for ocean mining have never been formally established. The United Nations has given that task to an obscure organization known as the International Seabed Authority, which is housed in a pair of drab gray office buildings at the edge of Kingston Harbour, in Jamaica. Unlike most UN bodies, the ISA receives little oversight. It is classified as “autonomous” and falls under the direction of its own secretary general, who convenes his own general assembly once a year, at the ISA headquarters. For about a week, delegates from 168 member states pour into Kingston from around the world, gathering at a broad semicircle of desks in the auditorium of the Jamaica Conference Centre. Their assignment is not to prevent mining on the seafloor but to mitigate its damage—selecting locations where extraction will be permitted, issuing licenses to mining companies, and drafting the technical and environmental standards of an underwater Mining Code.

Writing the code has been difficult. ISA members have struggled to agree on a regulatory framework. While they debate the minutiae of waste disposal and ecological preservation, the ISA has granted “exploratory” permits around the world. Some 30 mineral contractors already hold licenses to work in sweeping regions of the Atlantic, Pacific, and Indian Oceans. One site, about 2,300 miles east of Florida, contains the largest system of underwater hot springs ever discovered, a ghostly landscape of towering white spires that scientists call the “Lost City.” Another extends across 4,500 miles of the Pacific, or roughly a fifth of the circumference of the planet. The companies with permits to explore these regions have raised breathtaking sums of venture capital. They have designed and built experimental vehicles, lowered them to the bottom, and begun testing methods of dredging and extraction while they wait for the ISA to complete the Mining Code and open the floodgates to commercial extraction.

At full capacity, these companies expect to dredge thousands of square miles a year. Their collection vehicles will creep across the bottom in systematic rows, scraping through the top five inches of the ocean floor. Ships above will draw thousands of pounds of sediment through a hose to the surface, remove the metallic objects, known as polymetallic nodules, and then flush the rest back into the water. Some of that slurry will contain toxins such as mercury and lead, which could poison the surrounding ocean for hundreds of miles. The rest will drift in the current until it settles in nearby ecosystems. An early study by the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences predicted that each mining ship will release about 2 million cubic feet of discharge every day, enough to fill a freight train that is 16 miles long. The authors called this “a conservative estimate,” since other projections had been three times as high. By any measure, they concluded, “a very large area will be blanketed by sediment to such an extent that many animals will not be able to cope with the impact and whole communities will be severely affected by the loss of individuals and species.”

At the ISA meeting in 2019, delegates gathered to review a draft of the code. Officials hoped the document would be ratified for implementation in 2020. I flew down to observe the proceedings on a balmy morning and found the conference center teeming with delegates. A staff member ushered me through a maze of corridors to meet the secretary general, Michael Lodge, a lean British man in his 50s with cropped hair and a genial smile. He waved me toward a pair of armchairs beside a bank of windows overlooking the harbor, and we sat down to discuss the Mining Code, what it will permit and prohibit, and why the United Nations is preparing to mobilize the largest mining operation in the history of the world.

Until recently, marine biologists paid little attention to the deep sea. They believed its craggy knolls and bluffs were essentially barren. The traditional model of life on Earth relies on photosynthesis: plants on land and in shallow water harness sunlight to grow biomass, which is devoured by creatures small and large, up the food chain to Sunday dinner. By this account, every animal on the planet would depend on plants to capture solar energy. Since plants disappear a few hundred feet below sea level, and everything goes dark a little farther down, there was no reason to expect a thriving ecosystem in the deep. Maybe a light snow of organic debris would trickle from the surface, but it would be enough to sustain only a few wayward aquatic drifters.

That theory capsized in 1977, when a pair of oceanographers began poking around the Pacific in a submersible vehicle. While exploring a range of underwater mountains near the Galápagos Islands, they spotted a hydrothermal vent about 8,000 feet deep. No one had ever seen an underwater hot spring before, though geologists suspected they might exist. As the oceanographers drew close to the vent, they made an even more startling discovery: A large congregation of animals was camped around the vent opening. These were not the feeble scavengers that one expected so far down. They were giant clams, purple octopuses, white crabs, and 10-foot tube worms, whose food chain began not with plants but with organic chemicals floating in the warm vent water.

For biologists, this was more than curious. It shook the foundation of their field. If a complex ecosystem could emerge in a landscape devoid of plants, evolution must be more than a heliological affair. Life could appear in perfect darkness, in blistering heat and a broth of noxious compounds—an environment that would extinguish every known creature on Earth. “That was the discovery event,” an evolutionary biologist named Timothy Shank told me. “It changed our view about the boundaries of life. Now we know that the methane lakes on one of Jupiter’s moons are probably laden with species, and there is no doubt life on other planetary bodies.”

Shank was 12 years old that winter, a bookish kid in North Carolina. The early romance of the space age was already beginning to fade, but the discovery of life near hydrothermal vents would inspire a blossoming of oceanography that captured his imagination. As he completed a degree in marine biology, then a doctorate in ecology and evolution, he consumed reports from scientists around the world who found new vents brimming with unknown species. They appeared far below the surface—the deepest known vent is about three miles down—while another geologic feature, known as a “cold seep,” gives rise to life in chemical pools even deeper on the seafloor. No one knew how far down the vents and seeps might be found, but Shank decided to focus his research on the deepest waters of the Earth.

Scientists divide the ocean into five layers of depth. Closest to the surface is the “sunlight zone,” where plants thrive; then comes the “twilight zone,” where darkness falls; next is the “midnight zone,” where some creatures generate their own light; and then there’s a frozen flatland known simply as “the abyss.” Oceanographers have visited these layers in submersible vehicles for half a century, but the final layer is difficult to reach. It is known as the “hadal zone,” in reference to Hades, the ancient Greek god of the underworld, and it includes any water that is at least 6,000 meters below the surface—or, in a more Vernian formulation, that is 20,000 feet under the sea. Because the hadal zone is so deep, it is usually associated with ocean trenches, but several deepwater plains have sections that cross into hadal depth.

Deepwater plains are also home to the polymetallic nodules that explorers first discovered a century and a half ago. Mineral companies believe that nodules will be easier to mine than other seabed deposits. To remove the metal from a hydrothermal vent or an underwater mountain, they will have to shatter rock in a manner similar to land-based extraction. Nodules are isolated chunks of rocks on the seabed that typically range from the size of a golf ball to that of a grapefruit, so they can be lifted from the sediment with relative ease. Nodules also contain a distinct combination of minerals. While vents and ridges are flecked with precious metal, such as silver and gold, the primary metals in nodules are copper, manganese, nickel, and cobalt—crucial materials in modern batteries. As iPhones and laptops and electric vehicles spike demand for those metals, many people believe that nodules are the best way to migrate from fossil fuels to battery power.

The ISA has issued more mining licenses for nodules than for any other seabed deposit. Most of these licenses authorize contractors to exploit a single deepwater plain. Known as the Clarion-Clipperton Zone, or CCZ, it extends across 1.7 million square miles between Hawaii and Mexico—wider than the continental United States. When the Mining Code is approved, more than a dozen companies will accelerate their explorations in the CCZ to industrial-scale extraction. Their ships and robots will use vacuum hoses to suck nodules and sediment from the seafloor, extracting the metal and dumping the rest into the water. How many ecosystems will be covered by that sediment is impossible to predict. Ocean currents fluctuate regularly in speed and direction, so identical plumes of slurry will travel different distances, in different directions, on different days. The impact of a sediment plume also depends on how it is released. Slurry that is dumped near the surface will drift farther than slurry pumped back to the bottom. The circulating draft of the Mining Code does not specify a depth of discharge. The ISA has adopted an estimate that sediment dumped near the surface will travel no more than 62 miles from the point of release, but many experts believe the slurry could travel farther. A recent survey of academic research compiled by Greenpeace concluded that mining waste “could travel hundreds or even thousands of kilometers.”

Like many deepwater plains, the CCZ has sections that lie at hadal depth. Its eastern boundary is marked by a hadal trench. No one knows whether mining sediment will drift into the hadal zone. As the director of a hadal-research program at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, in Massachusetts, Timothy Shank has been studying the deep sea for almost 30 years. In 2014, he led an international mission to complete the first systematic study of the hadal ecosystem—but even Shank has no idea how mining could affect the hadal zone, because he still has no idea what it contains. If you want a sense of how little we know about the deep ocean, how difficult it is to study, and what’s at stake when industry leaps before science, Shank’s research is a good place to start.

I first met Shank about seven years ago, when he was organizing the international mission to survey the hadal zone. He had put together a three-year plan to visit every ocean trench: sending a robotic vehicle to explore their features, record every contour of topography, and collect specimens from each. The idea was either dazzling or delusional; I wasn’t sure which. Scientists have enough trouble measuring the seabed in shallower waters. They have used ropes and chains and acoustic instruments to record depth for more than a century, yet 85 percent of the global seabed remains unmapped—and the hadal is far more difficult to map than other regions, since it’s nearly impossible to see.

If it strikes you as peculiar that modern vehicles cannot penetrate the deepest ocean, take a moment to imagine what it means to navigate six or seven miles below the surface. Every 33 feet of depth exerts as much pressure as the atmosphere of the Earth, so when you are just 66 feet down, you are under three times as much pressure as a person on land, and when you are 300 feet down, you’re subjected to 10 atmospheres of pressure. Tube worms living beside hydrothermal vents near the Galápagos are compressed by about 250 atmospheres, and mining vehicles in the CCZ have to endure twice as much—but they are still just half as far down as the deepest trenches.

Building a vehicle to function at 36,000 feet, under 2 million pounds of pressure per square foot, is a task of interstellar-type engineering. It’s a good deal more rigorous than, say, bolting together a rover to skitter across Mars. Picture the schematic of an iPhone case that can be smashed with a sledgehammer more or less constantly, from every angle at once, without a trace of damage, and you’re in the ballpark—or just consider the fact that more people have walked on the moon than have reached the bottom of the Mariana Trench, the deepest place on Earth.

The first two people descended in 1960, using a contraption owned by the U.S. Navy. It seized and shuddered on the descent. Its window cracked as the pressure mounted, and it landed with so much force that it kicked up a cloud of silt that obscured the view for the entire 20 minutes the pair remained on the bottom. Half a century passed before the film director James Cameron repeated their journey, in 2012. Unlike the swaggering billionaire Richard Branson, who was planning to dive the Mariana in a cartoonish vehicle shaped like a fighter jet, Cameron is well versed in ocean science and engineering. He was closely involved in the design of his submarine, and sacrificed stylistic flourishes for genuine innovations, including a new type of foam that maintains buoyancy at full ocean depth. Even so, his vessel lurched and bucked on the way down. He finally managed to land, and spent a couple of hours collecting sediment samples before he noticed that hydraulic fluid was leaking onto the window. The vehicle’s mechanical arm began to fail, and all of the thrusters on its right side went out—so he returned to the surface early, canceled his plan for additional dives, and donated the broken sub to Woods Hole.

The most recent descent of the Mariana Trench was completed last spring by a private-equity investor named Victor Vescovo, who spent $48 million on a submarine that was even more sophisticated than Cameron’s. Vescovo was on a personal quest to reach the bottom of the five deepest trenches in the world, a project he called “Five Deeps.” He was able to complete the project, making multiple dives of the Mariana—but if his achievement represents a leap forward in hadal exploration, it also serves as a reminder of how impenetrable the trenches remain: a region that can be visited only by the most committed multimillionaire, Hollywood celebrity, or special military program, and only in isolated dives to specific locations that reveal little about the rest of the hadal environment. That environment is composed of 33 trenches and 13 shallower formations called troughs. Its total geographic area is about two-thirds the size of Australia. It is the least examined ecosystem of its size on Earth.

Without a vehicle to explore the hadal zone, scientists have been forced to use primitive methods. The most common technique has scarcely changed in more than a century: Expedition ships chug across hundreds of miles to reach a precise location, then lower a trap, wait a few hours, and reel it up to see what’s inside. The limitations of this approach are self-evident, if not comic. It’s like dangling a birdcage out the door of an airplane crossing Africa at 36,000 feet, and then trying to divine, from the mangled bodies of insects, what sort of animals roam the savanna.

All of which is to say that Shank’s plan to explore every trench in the world was somewhere between audacious and absurd, but he had assembled a team of the world’s leading experts, secured ship time for extensive missions, and spent 10 years supervising the design of the most advanced robotic vehicle ever developed for deepwater navigation. Called Nereus, after a mythological sea god, it could dive alone—charting a course amid rocky cliffs, measuring their contours with a doppler scanner, recording video with high-definition cameras, and collecting samples—or it could be linked to the deck of a ship with fiber-optic cable, allowing Shank to monitor its movement on a computer in the ship’s control room, boosting the thrusters to steer this way and that, piercing the darkness with its headlamps, and maneuvering a mechanical claw to gather samples in the deep.

I reached out to Shank in 2013, a few months before the expedition began. I wanted to write about the project, and he agreed to let me join him on a later leg. When his ship departed, in the spring of 2014, I followed online as it pursued a course to the Kermadec Trench, in the Pacific, and Shank began sending Nereus on a series of dives. On the first, it descended to 6,000 meters, a modest target on the boundary of the hadal zone. On the second, Shank pushed it to 7,000 meters; on the third to 8,000; and on the fourth to 9,000. He knew that diving to 10,000 meters would be a crucial threshold. It is the last full kilometer of depth on Earth: No trench is believed to be deeper than 11,000 meters. To commemorate this final increment and the successful beginning of his project, he attached a pair of silver bracelets to the frame of Nereus, planning to give them to his daughters when he returned home. Then he dropped the robot in the water and retreated to the control room to monitor its movements.

On-screen, blue water gave way to darkness as Nereus descended, its headlamps illuminating specks of debris suspended in the water. It was 10 meters shy of the 10,000-meter mark when suddenly the screen went dark. There was an audible gasp in the control room, but no one panicked. Losing the video feed on a dive was relatively common. Maybe the fiber-optic tether had snapped, or the software had hit a glitch. Whatever it was, Nereus had been programmed to respond with emergency measures. It could back out of a jam, shed expendable weight, guide itself to the surface, and send a homing beacon to help Shank’s team retrieve it.

As the minutes ticked by, Shank waited for those measures to activate, but none did. “There’s no sound, no implosion, no chime,” he told me afterward. “Just … black.” He paced the deck through the night, staring across the Stygian void for signs of Nereus. The following day he finally saw debris surface, and as he watched it rise, he felt his project sinking. Ten years of planning, a $14 million robot, and an international team of experts—it had all collapsed under the crushing pressure of hadal depths.

“I think we’ll be looking at hundreds or thousands of species we haven’t seen before, and some of them are going to be huge.”

“I’m not over it yet,” he told me two years later. We were standing on the deck of another ship, 100 miles off the coast of Massachusetts, where Shank was preparing to launch a new robot. The vehicle was no replacement for Nereus. It was a rectilinear hunk of metal and plastic, about five feet high, three feet wide, and nine feet long. Red on top, with a silvery bottom and three fans mounted at the rear, it could have been mistaken for a child’s backyard spaceship. Shank had no illusion that it was capable of hadal exploration. Since the loss of Nereus, there was no vehicle on Earth that could navigate the deepest trenches—Cameron’s was no longer in service, Branson’s didn’t work, and Vescovo’s hadn’t yet been built.

Shank’s new robot did have a few impressive features. Its navigational system was even more advanced than the one in Nereus, and he hoped it would be able to maneuver in a trenchlike environment with even greater precision—but its body was not designed to withstand hadal pressure. In fact, it had never descended more than a few dozen feet below the surface, and Shank knew that it would take years to build something that could survive at the bottom of a trench. What had seemed, just two years earlier, like the beginning of a new era in hadal science was developing a quixotic aspect, and, at 50, Shank could not help wondering if it was madness to spend another decade of his life on a dream that seemed to be drifting further from his reach. But he was driven by a lifelong intuition that he still couldn’t shake. Shank believes that access to the trenches will reveal one of the greatest discoveries in history: a secret ecosystem bursting with creatures that have been cloistered for eternity in the deep.

“I would be shocked if there aren’t vents and seeps in the trenches,” he told me as we bobbed on the water that day in 2016. “They’ll be there, and they will be teeming with life. I think we’ll be looking at hundreds or thousands of species we haven’t seen before, and some of them are going to be huge.” He pictured the hadal as an alien world that followed its own evolutionary course, the unimaginable pressure creating a menagerie of inconceivable beasts. “My time is running out to find them,” he said. “Maybe my legacy will be to push things forward so that somebody else can. We have a third of our ocean that we still can’t explore. It’s embarrassing. It’s pathetic.”

While scientists struggle to reach the deep ocean, human impact has already gotten there. Most of us are familiar with the menu of damages to coastal water: overfishing, oil spills, and pollution, to name a few. What can be lost in the discussion of these issues is how they reverberate far beneath.

Take fishing. The relentless pursuit of cod in the early 20th century decimated its population from Newfoundland to New England, sending hungry shoppers in search of other options. As shallow-water fish such as haddock, grouper, and sturgeon joined the cod’s decline, commercial fleets around the world pushed into deeper water. Until the 1970s, the slimehead fish lived in relative obscurity, patrolling the slopes of underwater mountains in water up to 6,000 feet deep. Then a consortium of fishermen pushed the Food and Drug Administration to change its name, and the craze for “orange roughy” began—only to fade again in the early 2000s, when the fish was on a path toward extinction itself.

Environmental damage from oil production is also migrating into deeper water. Disturbing photographs of oil-drenched beaches have captured public attention since at least 1989, when the Exxon Valdez tanker crashed into a reef and leaked 11 million gallons into an Alaskan sound. It would remain the largest spill in U.S. water until 2010, when the Deepwater Horizon explosion spewed 210 million gallons into the Gulf of Mexico. But a recent study revealed that the release of chemicals to disperse the spill was twice as toxic as the oil to animals living 3,000 feet below the surface.

Maybe the greatest alarm in recent years has followed the discovery of plastic floating in the ocean. Scientists estimate that 17 billion pounds of polymer are flushed into the ocean each year, and substantially more of it collects on the bottom than on the surface. Just as a bottle that falls from a picnic table will roll downhill to a gulch, trash on the seafloor gradually makes its way toward deepwater plains and hadal trenches. After his expedition to the trenches, Victor Vescovo returned with the news that garbage had beaten him there. He found a plastic bag at the bottom of one trench, a beverage can in another, and when he reached the deepest point in the Mariana, he watched an object with a large S on the side float past his window. Trash of all sorts is collecting in the hadal—Spam tins, Budweiser cans, rubber gloves, even a mannequin head.

Scientists are just beginning to understand the impact of trash on aquatic life. Fish and seabirds that mistake grocery bags for prey will glut their stomachs with debris that their digestive system can’t expel. When a young whale drifted ashore and died in the Philippines in 2019, an autopsy revealed that its belly was packed with 88 pounds of plastic bags, nylon rope, and netting. Two weeks later, another whale beached in Sardinia, its stomach crammed with 48 pounds of plastic dishes and tubing. Certain types of coral like to eat plastic more than food. They will gorge themselves like a kid on Twinkies instead of eating what they need to survive. Microbes that flourish on plastic have ballooned in number, replacing other species as their population explodes in a polymer ocean.

If it seems trivial to worry about the population statistics of bacteria in the ocean, you may be interested to know that ocean microbes are essential to human and planetary health. About a third of the carbon dioxide generated on land is absorbed by underwater organisms, including one species that was just discovered in the CCZ in 2018. The researchers who found that bacterium have no idea how it removes carbon from the environment, but their findings show that it may account for up to 10 percent of the volume that is sequestered by oceans every year.

Many of the things we do know about ocean microbes, we know thanks to Craig Venter, the genetic scientist most famous for starting a small company in the 1990s to compete with the Human Genome Project. The two-year race between his company and the international collaboration generated endless headlines and culminated in a joint announcement at the White House to declare a tie. But Venter’s interest wasn’t limited to human DNA. He wanted to learn the language of genetics in order to create synthetic microbes with practical features. After his work on the human genome, he spent two years sailing around the world, lowering bottles into the ocean to collect bacteria and viruses from the water. By the time he returned, he had discovered hundreds of thousands of new species, and his lab in Maryland proceeded to sequence their DNA—identifying more than 60 million unique genes, which is about 2,500 times the number in humans. Then he and his team began to scour those genes for properties they could use to make custom bugs.

Venter now lives in a hypermodern house on a bluff in Southern California. Chatting one evening on the sofa beside the door to his walk-in humidor and wine cellar, he described how saltwater microbes could help solve the most urgent problems of modern life. One of the bacteria he pulled from the ocean consumes carbon and excretes methane. Venter would like to integrate its genes into organisms designed to live in smokestacks and recycle emissions. “They could scrub the plant’s CO2 and convert it to methane that can be burned as fuel in the same plant,” he said.

Venter was also studying bacteria that could be useful in medicine. Microbes produce a variety of antibiotic compounds, which they deploy as weapons against their rivals. Many of those compounds can also be used to kill the pathogens that infect humans. Nearly all of the antibiotic drugs on the market were initially derived from microorganisms, but they are losing efficacy as pathogens evolve to resist them. “We have new drugs in development,” Matt McCarthy, an infectious-disease specialist at Weill Cornell Medical College, told me, “but most of them are slight variations on the ones we already had. The problem with that is, they’re easy for bacteria to resist, because they’re similar to something bacteria have developed resistance to in the past. What we need is an arsenal of new compounds.”

Venter pointed out that ocean microbes produce radically different compounds from those on land. “There are more than a million microbes per milliliter of seawater,” he said, “so the chance of finding new antibiotics in the marine environment is high.” McCarthy agreed. “The next great drug may be hidden somewhere deep in the water,” he said. “We need to get to the deep-sea organisms, because they’re making compounds that we’ve never seen before. We may find drugs that could be used to treat gout, or rheumatoid arthritis, or all kinds of other conditions.”

Marine biologists have never conducted a comprehensive survey of microbes in the hadal trenches. The conventional tools of water sampling cannot function at extreme depth, and engineers are just beginning to develop tools that can. Microbial studies of the deepwater plains are slightly further along—and scientists have recently discovered that the CCZ is unusually flush with life. “It’s one of the most biodiverse areas that we’ve ever sampled on the abyssal plains,” a University of Hawaii oceanographer named Jeff Drazen told me. Most of those microbes, he said, live on the very same nodules that miners are planning to extract. “When you lift them off the seafloor, you’re removing a habitat that took 10 million years to grow.” Whether or not those microbes can be found in other parts of the ocean is unknown. “A lot of the less mobile organisms,” Drazen said, “may not be anywhere else.”

Drazen is an academic ecologist; Venter is not. Venter has been accused of trying to privatize the human genome, and many of his critics believe his effort to create new organisms is akin to playing God. He clearly doesn’t have an aversion to profit-driven science, and he’s not afraid to mess with nature—yet when I asked him about the prospect of mining in deep water, he flared with alarm. “We should be very careful about mining in the ocean,” he said. “These companies should be doing rigorous microbial surveys before they do anything else. We only know a fraction of the microbes down there, and it’s a terrible idea to screw with them before we know what they are and what they do.”

Mining executives insist that their work in the ocean is misunderstood. Some adopt a swaggering bravado and portray the industry as a romantic frontier adventure. As the manager of exploration at Nautilus Minerals, John Parianos, told me recently, “This is about every man and his dog filled with the excitement of the moon landing. It’s like Scott going to the South Pole, or the British expeditions who got entombed by ice.”

Nautilus occupies a curious place in the mining industry. It is one of the oldest companies at work on the seafloor, but also the most precarious. Although it has a permit from the government of Papua New Guinea to extract metal from offshore vents, many people on the nearby island of New Ireland oppose the project, which will destroy part of their marine habitat. Local and international activists have whipped up negative publicity, driving investors away and sending the company into financial ruin. Nautilus stock once traded for $4.45. It is now less than a penny per share.

Parianos acknowledged that Nautilus was in crisis, but he dismissed the criticism as naive. Seabed minerals are no different from any other natural resource, he said, and the use of natural resources is fundamental to human progress. “Look around you: Everything that’s not grown is mined,” he told me. “That’s why they called it the Stone Age—because it’s when they started mining! And mining is what made our lives better than what they had before the Stone Age.” Parianos emphasized that the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea, which created the International Seabed Authority, promised “to ensure effective protection for the marine environment” from the effects of mining. “It’s not like the Law of the Sea says: Go out and ravage the marine environment,” he said. “But it also doesn’t say that you can only explore the ocean for science, and not to make money.”

The CEO of a company called DeepGreen spoke in loftier terms. DeepGreen is both a product of Nautilus Minerals and a reaction to it. The company was founded in 2011 by David Heydon, who had founded Nautilus a decade earlier, and its leadership is full of former Nautilus executives and investors. As a group, they have sought to position DeepGreen as a company whose primary interest in mining the ocean is saving the planet. They have produced a series of lavish brochures to explain the need for a new source of battery metals, and Gerard Barron, the CEO, speaks with animated fervor about the virtues of nodule extraction.

His case for seabed mining is straightforward. Barron believes that the world will not survive if we continue burning fossil fuels, and the transition to other forms of power will require a massive increase in battery production. He points to electric cars: the batteries for a single vehicle require 187 pounds of copper, 123 pounds of nickel, and 15 pounds each of manganese and cobalt. On a planet with 1 billion cars, the conversion to electric vehicles would require several times more metal than all existing land-based supplies—and harvesting that metal from existing sources already takes a human toll. Most of the world’s cobalt, for example, is mined in the southeastern provinces of the Democratic Republic of Congo, where tens of thousands of young children work in labor camps, inhaling clouds of toxic dust during shifts up to 24 hours long. Terrestrial mines for nickel and copper have their own litany of environmental harms. Because the ISA is required to allocate some of the profits from seabed mining to developing countries, the industry will provide nations that rely on conventional mining with revenue that doesn’t inflict damage on their landscapes and people.

Whether DeepGreen represents a shift in the values of mining companies or merely a shift in marketing rhetoric is a valid question—but the company has done things that are difficult to dismiss. It has developed technology that returns sediment discharge to the seafloor with minimal disruption, and Barron is a regular presence at ISA meetings, where he advocates for regulations to mandate low-impact discharge. DeepGreen has also limited its operations to nodule mining, and Barron openly criticizes the effort by his friends at Nautilus to demolish a vent that is still partially active. “The guys at Nautilus, they’re doing their thing, but I don’t think it’s the right thing for the planet,” he told me. “We need to be doing things that have a low impact environmentally.”

By the time I sat down with Michael Lodge, the secretary general of the ISA, I had spent a lot of time thinking about the argument that executives like Barron are making. It seemed to me that seabed mining presents an epistemological problem. The harms of burning fossil fuels and the impact of land-based mining are beyond dispute, but the cost of plundering the ocean is impossible to know. What creatures are yet to be found on the seafloor? How many indispensable cures? Is there any way to calculate the value of a landscape we know virtually nothing about? The world is full of uncertain choices, of course, but the contrast between options is rarely so stark: the crisis of climate change and immiserated labor on the one hand, immeasurable risk and potential on the other.

I thought of the hadal zone. It may never be harmed by mining. Sediment from dredging on the abyssal plains could settle long before it reaches the edge of a trench—but the total obscurity of the hadal should remind us of how little we know. It extends from 20,000 feet below sea level to roughly 36,000 feet, leaving nearly half of the ocean’s depths beyond our reach. When I visited Timothy Shank at Woods Hole a few months ago, he showed me a prototype of his latest robot. He and his lead engineer, Casey Machado, had built it with foam donated by James Cameron and with support from NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, whose engineers are hoping to send a vehicle to explore the aqueous moon of Jupiter. It was a tiny machine, known as Orpheus, that could steer through trenches, recording topography and taking samples, but little else. He would have no way to direct its movements or monitor its progress via a video feed. It occurred to me that if Shank had given up the dream of true exploration in the trenches, decades could pass before we know what the hadal zone contains.

Mining companies may promise to extract seabed metal with minimal damage to the surrounding environment, but to believe this requires faith. It collides with the force of human history, the law of unintended consequences, and the inevitability of mistakes. I wanted to understand from Michael Lodge how a UN agency had made the choice to accept that risk.

“Why is it necessary to mine the ocean?” I asked him.

He paused for a moment, furrowing his brow. “I don’t know why you use the word necessary,” he said. “Why is it ‘necessary’ to mine anywhere? You mine where you find metal.”

I reminded him that centuries of mining on land have exacted a devastating price: tropical islands denuded, mountaintops sheared off, groundwater contaminated, and species eradicated. Given the devastation of land-based mining, I asked, shouldn’t we hesitate to mine the sea?

“I don’t believe people should worry that much,” he said with a shrug. “There’s certainly an impact in the area that’s mined, because you are creating an environmental disturbance, but we can find ways to manage that.” I pointed out that the impact from sediment could travel far beyond the mining zone, and he responded, “Sure, that’s the other major environmental concern. There is a sediment plume, and we need to manage it. We need to understand how the plume operates, and there are experiments being done right now that will help us.” As he spoke, I realized that for Lodge, none of these questions warranted reflection—or anyway, he didn’t see reflection as part of his job. He was there to facilitate mining, not to question the wisdom of doing so.

We chatted for another 20 minutes, then I thanked him for his time and wandered back to the assembly room, where delegates were delivering canned speeches about marine conservation and the promise of battery technology. There was still some debate about certain details of the Mining Code—technical requirements, oversight procedures, the profit-sharing model—so the vote to ratify it would have to wait another year. I noticed a group of scientists watching from the back. They were members of the Deep-Ocean Stewardship Initiative, which formed in 2013 to confront threats to the deepwater environment. One was Jeff Drazen. He’d flown in from Hawaii and looked tired. I sent him a text, and we stepped outside.

A few tables and chairs were scattered in the courtyard, and we sat down to talk. I asked how he felt about the delay of the Mining Code—delegates are planning to review it again this summer, and large-scale mining could begin after that.

Drazen rolled his eyes and sighed. “There’s a Belgian team in the CCZ doing a component test right now,” he said. “They’re going to drive a vehicle around on the seafloor and spew a bunch of mud up. So these things are already happening. We’re about to make one of the biggest transformations that humans have ever made to the surface of the planet. We’re going to strip-mine a massive habitat, and once it’s gone, it isn’t coming back.”

#u.s. news#u.s. military#politics#politics and government#trump china#china news#china#tech news#technology#tech#world news#international news#news#atlantic ocean#oceanography#climatechangeisreal#climateaction#climate crisis#climate change

0 notes

Text

Where is winter chill: Lack of rainfall may be one of the culprits

In the last week of November itself venerable India Meteorological Department (IMD) predicted that winter will be mild this year. The Met office said, that temperatures in the winter months will rise by 0.5 to 1 degrees. Why it will be so remains a mystery as weak La Nina conditions prevailed in the pacific Oceans, which is usually seen as a sign of severe winters over Northern India.

Global warming may be one of the culprits. The signs were there for the previous couple of years, says the Met man but El Nino was the primary culprit then. Confusing? I am afraid it is. It only shows that despite our huge advances in technology and computer generated weather models, we understand so little of it.

The next factor responsible may be the lack of rainfall in the winter months. Rainfall usually helps winter chills to 'set in' over Northern India. Whenever a strong Western disturbance approaches the Western Himalayas, areas like Punjab, Delhi and Haryana witness some rainfall.

Also read: Over 50 trains delayed, six cancelled due to fog

WEATHER FORECASTING

There is some good news as the weatherman is forecasting a Western disturbance in the coming week. Delhi, parts of North-western Uttar Pradesh, Punjab and Haryana may get light to moderate rains in roughly the next three to five days.

If it happens then it will be the first spell of winter rainfall over the Northern plains. It is expected to bring down the maximum and minimum temperatures over these areas and winter will expectedly make a comeback.

Further from home the Arctic has seen unusually high temperatures. One reading in December was around zero degrees, which is more than 15-20 degree warmer than the average temperature for corresponding period in years. Another unusual phenomena is being noted as high temperatures in the Arctic is corresponding with extremely cold snaps over Siberia.

Also read: 52 trains delayed, 10 rescheduled due to fog

WARM ARCTIC COLD CONTINENTS

Scientists call this phenomena 'Warm Arctic Cold Continents' a sometimes contentious term, little understood, but with grave implications if true. The model is complicated but generally entails the Poles getting warmer and the mid latitudes getting colder - Siberia, parts of the USA, Europe and Northern Asia.

As with every hypothesis there are two sides of a debate. Global warming is blamed by a group while the other argues that it is a cyclic event when Arctic literally shed its snow. However even with scientific models it is difficult to see if this is a normal trend that we are seeing for the past decade or if it is the result of human interventions.

Also read: Except north India, country to have above normal winter: IMD

#_lmsid:a0Vd0000002uQfeEAE#_revsp:india_today_57#_draft:true#_uuid:f73dc1da-db90-3c81-a264-9cb4dcc1b7eb

1 note

·

View note

Text

The climate change exchange: ‘Back-up’ plan

Whether we are talking about atmospheric normalization or global warming’s and/or climate change’s causation, “balance” is the word. That’s right, balance.

So in a kind of holistic air-healing sense or maybe more precisely, a holistic air-remedying context, what does being balanced mean exactly?

From physics, we know that if an object exerts a force opposite and equal to that which is being externally exerted upon it, then that object is said to be in a state of equilibrium and consequently that object remains at rest. Furthermore, for soils whose pH levels are lower they are more acidic (less alkaline) and for soils whose pH levels are higher they are less acidic (more alkaline). When a state of equilibrium is reached and pH levels are balanced, the alkalinity zeros out the acidity and vice versa, meaning in terms of pH levels these soils are balanced.

So, how does this relate to air or the atmosphere?

Ever hear of the term “carbon neutral” or “carbon neutrality”? What this implies is that for whatever amount of carbon is entering air or the atmosphere, as long as there is an equal amount of carbon exiting or leaving air or the atmosphere, the air or the atmosphere is carbon neutral.

So, the question becomes: Is carbon neutrality what we should be shooting for?

What we know definitively is that since the introduction of the Industrial Revolution in 1750, Earth’s average surface temperature has risen approximately 1 degree Celsius (1.8 degrees Fahrenheit). If we stay on the track we’re on currently, that is, without any intervention – human or otherwise, the scientific consensus has it that by 2100 the Earth’s average surface temperature will rise to between 3.4 and 6 degrees Celsius (5.2 and 7.8 degrees Fahrenheit).

So, it is with this in mind that NASA Earth Observatory correspondent Rebecca Lindsey in 2009 reasoned, “If the concentration of greenhouse gases stabilizes, then Earth’s climate will once again come into equilibrium, albeit with the ‘thermostat’—global average surface temperature—set at a higher temperature than it was before the Industrial Revolution.” The operative term here: greenhouse-gas stabilization.

The bigger question here is: What is the plan to get there?

Backing up

An important consideration to keep in mind is that historically global mean surface temperature has heated up much more rapidly than the rate at which GMST has cooled.

So, any intervening or mitigating strategy involving extraneous means with which to achieve atmospheric greenhouse-gas stabilization, must not only be effective in bringing this so-called air normalization about, but does so, in theory, at least, in relatively short order.

In realistically approaching this situation, we have options. One of these, of course, is carbon capture and storage (CCS) and carbon removal and reuse (CRR). These are atmospheric recovery or air rescue – mitigation – schemes. There are others as well.

What “back-up” means is just what the term implies: to back up or go in reverse.

Think about all of the times we have gotten lost when behind the wheel. What do we do to get out of the jam we’ve gotten ourselves into? We ask for directions if that is an option or we go back the way we came and start over again. As to the latter, why not do the same when it comes to atmospheric greenhouse gas stabilization or atmospheric normalization? This is not difficult. Just back up!

So, does that entail reverting back to practices comparable to those just prior to the introduction of the Industrial Revolution? No. What it means is what brought us to this place air quality/atmosphere degradation-wise, do less of what has contributed to that and, while we’re at it, make more use of the practices, procedures, programs which help improve air quality as well as not cause further air degradation.

Examples

Flue gas stacks and scrubber absorber vessel

Cutbacks in coal-fired power plant generation – Just about a third of U.S. energy production is by way of coal-fired power plant generation. This is down significantly since the mid-20th century; about a 50 percent reduction.

There are examples of coal-fired power plant shutdowns. One, the Navajo Generating Station in Page, Arizona, profiled in “With Ariz. generator decommissioning come coal-hauler, mine demise,” on Sept. 7, 2019, was due to go offline in December of last year.

Coal-plant closures have come about for one reason or another. There are other more efficient ways of producing electricity. Another has to do with requirements for meeting clean-air standards. Doing such for some plants is cost-prohibitive. Some that are able to can reconfigure, that is to say that they can be converted to burn natural gas, for instance, in place of coal which is cleaner-burning.

Boulevards from highways – You know what they say: Out with the old, in with the new. It’s a familiar refrain.

This topic was covered in the “Being on ‘broad way’ maybe not such an air-smart move after all,” Jun. 25, 2018 Air Quality Matters post.

From the post: “On the afternoon of Oct. 17, 1989 in the Santa Cruz Mountains located south of San Francisco, California a magnitude 6.9 earthquake struck. Violent shaking from what is now known as the Loma Prieta Earthquake of 1989, affected a number of buildings and infrastructure throughout the area and that included in West and East Bay Area communities alike as well as to the upper and lower spans of the San Francisco-Oakland Bay Bridge east of Yerba Buena Island. Hardest hit it seems were San Francisco and Oakland. Extensive damage to freeway structures including the Cypress Street Viaduct portion of the 880 interstate in Oakland and a section of the Embarcadero Freeway (State Route 480) in San Francisco was incurred. The double-decked structures experienced “pancaking,” whereby the upper portions collapsed onto lower parts. Where damage occurred those portions were demolished.”

Long story short, “In the Embarcadero Freeway’s case, it was torn down and replaced by a boulevard at grade or ground level. Moreover, new development in the area took root.”

Similar cases abound. An excellent resource is: “A federal Highways to Boulevards program is the infrastructure project a healthy and equitable America needs,” by Ben Crowther, a Public Square article on the Web site of the Congress for New Urbanism here.

and lastly …

Cities transformed – How one city, Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada, got it right.

When faced with the choice on how to redevelop, Vancouver, Canada chose smartly.

So really briefly, “This truly insightful decision resulted in Vancouver being transformed, evolving from what once could be described as having a “cookie cutter” urban framework or appearance, in effect, following a growth and development style so common in so many other cities across the North American continent, to what can be considered a model with respect to place-making, space utilization, and enhanced travel and transportation efficiencies. A new and improved Vancouver had arrived!” (Source: “Growing pains: Dispersed or concentrated cities: Which is better?”).

Vancouver, B.C. is among good, like company.

These are but three examples. There are indeed more.

Images: Dennis Murphy (upper); U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (middle)

Published by Alan Kandel

source https://alankandel.scienceblog.com/2020/08/30/the-climate-change-exchange-back-up-plan/

0 notes

Text

9 Things Americans Can Learn From European Offices

If you were born in the United States, your work habits probably raise more than a few eyebrows across the pond. Europeans have a different philosophy of work, and if you look at happiness surveys, you’d say they’re doing something right.

What can Americans learn from their cousins across the Atlantic? More importantly, what takeaways can U.S.-based industries borrow to improve productivity and employee retention? While many differences exist, the crucial contrast occurs in the realm of work-life balance.

1) They Don’t Eat at Their Desks