#while I will say I made this with a more comic centric mindset I think a lot of these questions could work with other genres

Text

🦸🦹Superpower Character Ask Game:

I think a lot about characters with superpowers so I thought it would be fun to make an ask game surrounding that theme. Whether they're a hero, a villain or somewhere in between, if they've got powers this game is for them! Up, up, ask awaaaay!~

Does your character like their powers?

How often is your character underestimated?

Is your character's supersona true to their regular personality?

How does your character feel about publicity?

Under what circumstances would your character willingly give up their powers?

How did your character get their super identity?

If your character could choose to gain an additional power, what would they choose?

Does your character prefer to work solo or with others?

Where is your character’s base of operations?

Is your character good at fighting without their powers?

Does your character more often deal with localized, globalized or intergalactic matters?

If your character could have a pet with superpowers similar to their own, what kind of animal would they choose to have?

Does your character feel obligated to use their powers?

Is your character more impulsive or strategic?

How did your character learn to fight?

Who is your character most likely to turn to for guidance?

Does your character prefer having a civilian job or a super career?

How does the general public feel about your character's powers?

What adjective(s) would you use in front of your character's super moniker?

Does your character have a theme they like to stick with?

Is your character more offensive or defensive?

How would your character’s civilian self speak about their supersona?

Who would your character most like to disclose their secret identity to?

How would your character feel about someone trying to impersonate them?

What might make your character act recklessly?

If your character had to rebrand their supersona, how would they change it?

Does your character have someone they’d be willing to give up their super lifestyle for?

What is a principle your character lives by?

Who would your character say is an inspiration of theirs?

What would your character say is most cumbersome about their super lifestyle?

How would your character react if they encountered an opposite personality version of themself?

Does your character feel a connection to the force they fight against?

Would others find it surprising to see your character act vengefully?

What are your character’s views on violence?

Would your character still choose to fight if they lost their powers?

Does your character prefer using their powers, natural abilities, or gadgets/weapons?

What are your character’s views about others in their field?

Did your character have to switch aspirations because of their powers?

What imagery would be used to get your character’s supersona as a result in an online quiz?

Would your character work well with a duplicate version of themself?

Does your character care about public opinion?

If your character had to transfer their powers to someone else, who would they choose to give them to?

What is your character’s opinion on quips, banter and monologuing?

How does your character feel about the legal system?

If your character had to have a catchphrase what would they choose it to be?

What would be your character’s dream base of operations?

Does your character have a strong opinion on costumes?

What kind of merchandise would best suit your character if they had to get branded?

What genre of music would your character’s score be?

How willing would your character be to fight alongside their adversary for a common goal?

#oc asks#oc ask game#oc#ocs#writing#writing prompt#ask game#superhero#superheroes#super villain#super villains#while I will say I made this with a more comic centric mindset I think a lot of these questions could work with other genres#also as will be true for any future ask games#if you worry about reblogging without sending an ask I grant you guilt free enjoyment excelsior!#its-a me portfolio!

9 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hey! I’m not sure if anyone else has asked you this before, but I’m interested in getting to know Harry better as a character, and how he relates to other main characters within Spider-Man, and I wanted to ask you this: If Harry ever appeared again in any brand new piece of media as a character, what would you have wanted the writers to have read or known about him before writing him, that you think, if taken into account when writing him, would make him really spot on? Sorry if this is a strange way to put it!

Hi! That's a great question.

I've answered a somewhat similiar ask over here, but my response focused on good Harry centric material. While I absolutely recommend everything in the reply I linked to get a good picture of Harry as a character, I wouldn't recommend that exclusively. Because as I mentioned in that post, a lot of what defines Harry as a person happens outside of big dramatic developments for him. And I think that one of the major mistakes most adaptations so far have made is reducing Harry to Green Goblin Junior when he has always been so much more.

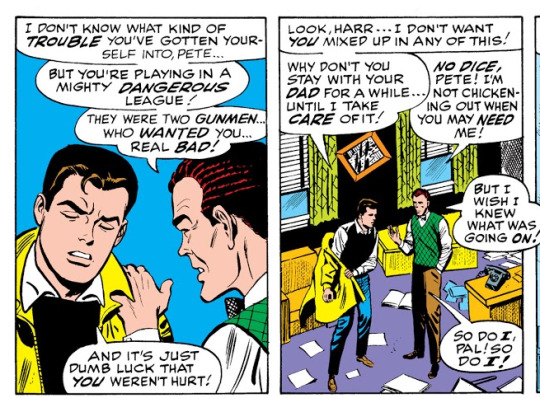

The result is that audiences see this side of Harry:

The Spectacular Spider-Man (1976) #200

But not necessarily this one:

The Amazing Spider-Man (1963) #60

Or this one:

The Amazing Spider-Man (1963) #261

I would recommend anyone having a go at an in-depth Spidey adaptation to read "casual" issues that don't stand out much on their own. Not all of them ofc, as that is an impossible amount of comics, but a handful from whichever era(s) you plan to take inspiration from. That way, you get a feel for how the characters behave in day to day situations, and which struggles follow them beyond the villain of the week. Harry is no exception here.

I believe seeing him just being his regular self is extremely integral to the true weight of his eventual villainy. Because who he tries to be when he’s the Goblin stands in such stark contrast to who he is authentically, but also because the build-up to Goblin Harry has honestly been there since day one. Not that it was intentional since day one - I'm very sure Harry was absolutely not supposed to be this complex and prominent of a character when he was introduced in TASM #31. But the emotional issues he exhibited since the beginning of his character - his strained relationship to his father, his own feelings of inadequacy and "weakness" - have followed the character for many years and gradually snowballed into the mindset that led him to put on the ol green costume. (I will say, originally Harry's Goblin was not as multidimensional and captivating as JMD eventually wrote him to be. He was more like a stand-in for Norman's after his death lol. But even so, the theme of power vs weakness has been tied to the persona for Harry since early on - Somewhere around the Dr Hamilton arc, if not earlier)

Now that you've gotten past this wall of text, here's what you really came for: A couple more or less "unspectacular" Harry appearances I recommend to people who wanna see beyond the Goblin (hah) Primarily from the 60s and 70s because I'm still working on my 616 readthrough and also because the list might get far too long otherwise

The Gwen Stacy miniseries - or what Marvel published of it before it got unjustifiably cancelled. Harry appears as a side character and we get a good look at his longlasting friendship to Gwen

The Amazing Spider-Man (1963) #39 & #40. The beginning of Peter and Harry's friendship, as well as first insights into Harry's... less than ideal upbringing

The Amazing Spider-Man (1963) Annual #96 Heart&Soul. A flashback of sorts to an earlier issue with more focus on Harry's emotional turmoil at the time.

The Amazing Spider-Man (1963) #53, #54, #57 & #59. Harry is pouty at Peter for not spending enough time with him but immediately struck by regret when Peter disappears suddenly. Once he returns, Harry instantly forgives his roommate.

The Amazing Spider-Man (1963) #61 & #62. Harry is caught up in unfavorably comparing himself to Peter

The Amazing Spider-Man (1963) #96 & #97. Tension arises between Peter and Harry, and Harry's drug addiction comes to light.

Everyone feel free to drop more suggestions for good Harry content!

38 notes

·

View notes

Text

Some Initial Thoughts on Daredevil Volume 6

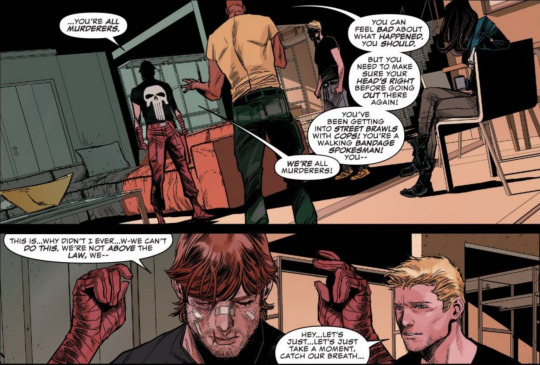

[ID: Excerpt from the current Daredevil run. Matt Murdock is standing in his apartment, wearing the bottom half of his Daredevil costume, a Punisher shirt, and no mask. He is unshaven and his face is bandaged. He’s talking with Luke Cage, Danny Rand, and Jessica Jones, all of whom are in civvies.]

Matt: “...You’re all murderers.”

Luke: “You can feel bad about what happened. You should. But you need to make sure your head’s right before going out there again! You’ve been getting into street brawls with cops! You’re a walking bandage spokesman! You--”

Matt: “We’re all murderers! This is... why didn’t I ever... w-we can’t do this. We’re not above the law, we--”

Danny: “Hey... let’s just... let’s just take a moment, catch our breath...”

Daredevil vol. 6 #5 by Chip Zdarsky, Marco Checchetto, and Sunny Gho

I haven’t talked much about the current Daredevil run, because I tend to avoid talking about things I’m not enjoying, but I was extremely torn about the first story arc. It’s not just because it's ripped right from the Netflix show (616 Matt has never been this religious, all of the themes and character cameos are Netflix-y, and the recently-revealed cover for #9 is basically a screenshot from Season 3.) If that’s where Zdarsky has drawn his inspiration, that’s fine. It’s his story to tell. It’s not what I would like, since I am very attached to 616 Matt, but it’s certainly a way to get MCU fans reading comics, and that’s great! Soule made clear references to the show as well, and at least Matt has his red hair back (poor Jessica hasn’t been so lucky). And it’s not just because the characterization is iffy (as I discussed in regards to the Punisher’s guest appearance in issue #4). And it’s not even the themes of the story itself. Zdarsky is far from the first person to address the violence and hypocrisy inherent in superheroism-- that was a primary theme of Nocenti’s run as well, and digging into Matt’s mindset regarding this aspect of his crimefighting can be highly compelling.

My biggest disconnect with this story is its seeming ignoring of Daredevil continuity. I’d be far more convinced by Matt’s freak-out about murder if this didn’t take place so soon after “Shadowland”, when Matt rammed a sai through Bullseye’s chest on the roof of the Javits Center. I would be more interested if this story addressed the other people Matt has accidentally killed over the past 55 years: the Fixer, who had a heart attack while fleeing Daredevil in the very first issue of the comic. Heather Glenn, who Matt drove to suicide. All of the various Silver Age villains who conveniently fell to their deaths after Matt tried and failed to rescue them. Heck (...not to make everything about Mike, but...), Matt’s newfound regrets about trying to delete his brother! Matt is not a killer, and I would hate for him to come across that way, but if that’s what Zdarsky wants to explore, he should at least explore it in a meaningful way. I would love this story if it were actually in conversation with the rest of the comic, particularly coming, as I mentioned, so close on the heels of the biggest murder-centric Daredevil story ever written. Given all of this context, all of the painful experiences Matt has had involving the deaths of others, I’m struggling to buy his having a mental breakdown over causing the death of a random guy in what was clearly an accident... without even mentioning those past experiences and explaining why this is somehow more traumatic.

So far, this run has felt like all flash and no bang-- beautiful art and cool fight scenes strung together by weak characterization and uninspired writing... plus a complete lack of a supporting cast, which was one of the downfalls of Soule’s run as well. And to be clear: I love beautiful art and cool fight scenes. I just feel like this story thinks it’s deeper and more groundbreaking than it actually is. I think there are a lot of strengths in this run, and of course I will keep reading, because it’s Daredevil, but that’s been my reaction so far. I have high hopes for improvement. I was so-so on a lot of Soule’s run, and then he introduced Mike, so you really can’t judge a story until it’s over. Please, Zdarsky, give me a reason to love this run.

31 notes

·

View notes

Text

Thoughts on the comic book industry, Part 6

I've been touching on this on and off during this prolonged rant about the state of the comic book industry, but there's no way to continue this rant without going into detail on this point. It's at least half the reason the industry is in such ruin, and it's a big reason why the major publishers are so unwilling to get with the times and get their acts together.

Over the past 3 decades, the major publishers have cultivated a core audience of regressive, close-minded, selfish fanbrats who (a) are in lockstep with the tastes and preferences of the Big 2, (b) are resistant to any kind of beneficial change, and (c) are ready and willing to excommunicate anyone who, shall we say, "isn't of the body." Essentially, what little remains of the readership is a twisted hybrid of Landru from Star Trek and the Buddy Bears from Garfield. (Although I suppose another Star Trek villain, Gorgan, applies as well – "Our purity of purpose cannot be contaminated by those who disagree.") All the awful stereotypes associated with geek culture? These are the people on whom those stereotypes are based.

If you think the Big 2 don't give a shit about the integrity of their characters, or about the quality of the stories, or about the legacies they're supposed to be caretaking...well, neither does their core audience of choice. The tiny minority they cater to may make a lot of noise about preserving the "history" of the characters, but they define that history purely by their pet incarnations and dismiss everything outside of that. For DC, the "history" its target audience wants preserved is the 1986-2011 period (or, for what's left of the Superman fandom, 1986-1999 only), with a burning, outspoken contempt of anything that doesn't bear at least a surface similiarity to it. Hence "Rebirth," despite being a creative and sales failure, being praised to the skies on social media. For Marvel, what's left of its audience doesn't give a damn about the company's history at all; they just accept whatever's thrown their way. There's a reason why the term "Marvel Zombies" existed long before the comic of the same name. That same willful ignorance and disregard of the history and legacy of the Big 2 even extends to the creators they choose to lionize or condemn. If it's a creative team or a specific era the fandom has decreed holy writ, they can get away with anything they want and the worst aspects of that era will be whitewashed or made excuses for. But if its creative teams or eras the fandom doesn't approve of? Everything about it, no matter how innocuous or even based in the franchise's existing history, will be excoriated as an abomination. Everything the remaining fandom upholds or tears down has nothing to do with the actual history of the industry and everything to do with their personal tastes.

(By the by, this also extends to comic book adaptations as well. Whoever the fandom chooses to rally behind can do no wrong regardless of how destructive and ruinous their ideas are, while filmmakers the fandom chooses to hate can't win no matter how respectful they try to be.)

It also doesn't help that the target readership of the major publishers also shares the same nihilistic, meanspirited attitude so prevalent in most comic book stories now. It's not uncommon for the remaining fandom to justify malicious event-gimmicks with comments like "Why should the heroes' lives be nothing but rainbows all the time?" (This was an actual defense for Cry for Justice/Rise of Arsenal, I kid you not.) Characters behaving horribly, like Lois Lane being emotionally abusive or Batman being willing to betray and assault the people closest to him (his physical attacking of Alfred in All-Star Batman in particular) gets praised as being "badass," "cool," "strong and empowering," etc. Hell, even Spider-Man openly admitting that he was making his deal with Mephisto for purely selfish reasons – that he didn't want to honor Aunt May's wishes to die peacefully because he didn't want to feel guilty about his mistakes leading to her death – was praised as heroic and noble even though he explicitly stated his intentions on-panel. And look at the SJW characters Marvel's been pushing for years. Many of them are hostile and unlikable people, and yet the readership will defend them by accusing naysayers of sexism, racism, and any other politically-charged insult they can think of. In a lot of ways, what passes for comics from the Big 2 these days is, in essence, glorified Mary Sue fiction, with the creators and the remaining fandom glorifying themselves and their pet choices.

And as a result of this, many characters who were once noble and honorable are turned into absolute jerks, characters who once had depths and layers are reduced to one-dimensional cutouts with no real personality or soul, and characters with a history of being unlikable get exalted and showcased at the expense of all else. And what's left of the fandom wants it this way, because it feeds their own sense of superiority and allows them to project themselves onto the characters. If you dare to point out that certain characters have been stripped of their humanity and nobility and are just one-note, shallow husks, the remaining fandom will assert that such characters are "cool" and "deep," and that you're just an idiot or a fan of another character who doesn't know any better. If you point out that certain female characters are consistently portrayed as selfish, entitled, and cruel for no good reason, you'll be accused of misogyny and "not being able to handle strong women." And so on. To point out flaws and failings in the fandom's golden calves of choice is tantamount to personally insulting the fandom itself. Which is the same mindset DC and Marvel have when faced with criticism.

There's also an insane, utterly baffling refusal to even consider even moderate, reasonable updates and/or changes to certain properties, whether it's long-overdue costume upgrades, shedding outdated tropes or settings, or even replacing old creative teams who've overstayed their welcome with fresh blood. Over and over again, you'll hear "If it ain't broke, don't fix it" as a catch-all excuse to never change anything at all, no matter how necessary those changes are or if the old creative teams are completely out of anything resembling fresh ideas. In some cases, the industry's target audience will point to said old creators' past successes (if any) as an excuse to never replace them with new talent. And if the fandom decides they won't accept any new talent, there's no excuse they won't use to dismiss or demonize said new talent. Back in the early 2000s, for example, Ed McGuinness, Doug Mahnke, Mike Wieringo, and other creators working at DC were repeatedly bashed for being "too manga" for the fans' liking. Never mind that Mahnke's work doesn't look anything like manga, never mind that Wieringo had previously worked at DC during the '90s on high-profile books, and never mind that McGuinness owed his style more to American animation. They were replacing old, worn-out talent that the fandom didn't want to let go of, therefore "too manga" was seen as a valid excuse to hate their work. Even artists like the late Darwyn Cooke and Eric Powell have been bashed for being "too cartoony" or "too childish," despite it being well-known that cartoony art styles are much harder to pull off because you can't hide behind a lot of detail.

The refusal to accept anything but old, stale creators on the same properties ad nauseum often extends to a refusal to even consider artists drawing anything but the same damn thing over and over again. With Superman, you still have, decades after the fact, people wanting nothing but Curt Swan or Curt Swan imitators drawing the books, never mind that the franchise visually stagnated during the Bronze Age as a result. With creators like Darryl Banks, Scott McDaniel, Mark Bagley, and – before his career-ending stroke – Norm Breyfogle, fans don't want them drawing anything but their "signature" characters, and are actively hostile to even the suggestion that those artists could or should draw anything else. Speaking from personal experience, I've found that 90% of the time artists love drawing something other than their usual fare. But talk about this with the comic book fandom that exists now, and they treat it as an insult to the artists and an unnecessary risk because "you're making them draw things they have no affinity for." The idea of comic book artists being versatile and able to draw any kind of subject matter doesn't even occur to them at all, and they treat it as an affront if you even suggest it. Again, all they want is stale, stagnant comfort food, even if it conflicts with what the artists themselves would want to do.

Then again, that same inability to look beyond their personal tastes is reflected in their willful ignorance of the history of comic books, and even of the nature of comic storytelling. Over and over again, you see the existing fandom claiming to love and protect the "history" of the Big 2, but that history begins and ends with their pet incarnations. How often have you seen DC's pre-1986 history trashed and mocked on both fan forums and comic-centric blogs? A lot. There's very little love, if any, for anything published before Crisis on Infinite Earths. And a lot of times, the fandom will parrot outright lies – be they fan-made or even pimped by the publishers themselves – as absolute historical fact despite what was actually published in the past. (Batman's pre-Frank Miller history and Gwen Stacy and Mary Jane Watson's roles in Spider-Man immediately come to mind as examples of such.) Even worse, sometimes the fandom will pimp their pet creators as being more deserving of creator credit than the characters' actual creators, or even advocate abolishing creator credits altogether if they decide they don't like either the original creators or the creators' estates. As for the willful ignorance of how comic storytelling works, here's a very worrying example: Marvel artist Greg Land is notorious for copy-pasting his old work and tracing/swiping from other sources, including porn and other artists' work. This habit has cost him friends and creative partners over the years. And yet, when his fans came to his defense, not only were his habits excused and defended, but some even made the assertion that Land isn't responsible for telling a story; he's just there to draw pretty pictures and that artists aren't there to tell stories in the first place.

This is a direct violation of what comics are: writing and art coming together to tell a story visually. In many cases, creators write and draw their own work. Visual storytelling is what comics are all about. But because an artist the fandom decided to champion was outed as a hack, some of his defenders decided that the rules of comic storytelling didn't exist, much less apply to said artist.

This should worry anyone who actually does love comics as a medium, because this is the audience the industry has been cultivating over the last 26-32 years. A tiny, whiny minority readership that doesn't have any real love or knowledge of the medium or the characters therein, that only wants the same tired old shit no matter how stale or outdated it is, that mimics the tastes and attitudes of the creators responsible, and is insanely devoted to either no change whatsoever regardless of merit or to extreme and destructive changes by their pet creators. I mean, really, is there any difference between legendary social media bully Michael "ManoftheAtom" Sacal screaming and yelling at anyone who doesn't share his "Iron Age only or else" mentality and creators like Mark Waid and Joe Quesada insulting and bullying anyone who doesn't share their distorted, selfish personal interpretations of their pet eras? Is there any real difference between fans incapable of accepting even minor and harmless updates and creators like Mike Manley going "Fuck your [insert character]!" on Facebook in regards to anything but his pet interpretations of said characters? (Ironically, Manley famously called fans unwilling to accept anything but Frank Miller's Batman "babymen." Apparently he's not capable of heeding his own advice.) Is there any real difference between fans who don't even understand how comic storytelling works at all and editors like Tom Brevoort who defend hack artists by pointing to sales (such as they are) and if their tracing and swiping "looks good"? Is there any difference at all between fans who spout bad SJW/far-left jargon and comic book pros who do likewise? And is there any difference between fanbrats who spew bile toward cosplayers and comic book pros who do the same damn thing? The answer is no. What remains of the comic book fandom is nothing but an echo chamber for the industry and its sycophants. No room for anything other than the chosen dogma, no room for anything resembling growth, change, evolution, or even just new ideas in general.

Making matters worse is that like any echo chamber, there's a huge amount of infighting when it comes to how pure of a fan you are and how devoted you are to the chosen dogma. Let's be honest; comic book fans don't just hate anyone not already in the clique, but they can't even play nice with each other. Male fans will tear each other apart for even slight differences of opinion, and female fans will tear each other apart for the same reason or even for daring to depart from the far-left/feminist/SJW bent of websites like Girl Wonder.org, The Mary Sue, and the Dreamwidth version of Scans Daily. (By contrast, the original Livejournal version of Scans Daily was a far more tolerant and welcoming community than what replaced it.) And when male and female fans collide for whatever reason...forget it. Their agendas are too polar opposite for them to ever have any common ground (the feminist/SJW fans crying sexism over anything that even slightly evokes female sexuality and hardcore male fans whining endlessly about anything that isn't fanservice sleaze). There's a reason why comic book fandom has a such a negative image attached to it. It's so insular, so arrogant, so unwilling to bend from its sense of self-entitlement that there isn't any place for new fans, or even older fans who are far more moderate and willing to accept change as necessary. Nobody's going to want to be part of an industry and/or fan community that tries to dictate what you can't or can't like, what you can or can't think, or how you can or can't treat anyone not already in the existing clique.

Don't ever expect these guys to show any self-awareness if or when it's pointed out that their attitudes are not only strangling the life out of comics, but also giving comic book fandom a deservedly terrible reputation. Any time this lunatic fringe gets called out on its bullshit, they repeatedly, without fail, justify their behavior by calling it "passion." They see themselves as the true believers, the chosen ones to whom the industry truly belongs and thus anything they say and do is A-OK. No, I'm sorry, but that's not how any of this works. Being utter jerks to anyone not already in their clique is not "passion." Being insanely hateful and willfully ignorant while congratulating each other for being "scholars and gentlemen" is not "passion." Demanding and encouraging creative and artistic stagnation is not "passion." Bullying each other over perceived fandom purity is not "passion." And when they make it clear over and over again that their regard for the medium begins and ends purely with their personal tastes, that's not "passion," either. It's just plain being a selfish ass. These people have just as much love for comics as the major publishers do...little to none. It's all about self-aggrandizement for them, and they're too wrapped up in themselves to realize it.

Which is going to bring us to the next issue that needs to be broached, an issue that could and likely will spell the death of the comic book industry as we know it.

3 notes

·

View notes

Note

hi so I didn't know who to ask but in my psych class we're learning about adolescent psychology, & there was this unit on developing interest in relationships. It went way into detail on how the brain changes during that time, which was interesting, but ofc my gay ass couldn't relate. at the end all it said was 'it's different for homosexuals.' I guess I'm wondering if you know of any way to learn about psychology relating to LGBT people? srsly im thirsty for anything in academia I can relate to

(same psych anon) that was a pretty specific question so I guess like do you have any info or know of any links/ websites/places to learn about lgbt history and lives and stuff like that in an academic way? bc I love school & learning but I’ve always wanted to learn more about myself and people like me, but they never teach that in schools.

Oh my gosh SO MANY THINGS! Okay, so, the psych stuff is pretty outside of my knowledge but I asked my gf (she does the science in this relationship while my gay ass just reads a whole lot of books), and she recommends Helen Fisher and looking at the researchers at the Society for the Scientific Study of Sexuality or the Kinsey Institute, as well as The Sage Encyclopedia of LGBTQ Studies (it’s an online resource a lot of universities subscribe to). But I’d also say that as far as thinking about developmental narratives, LGBTQ memoirs are a great place to start, especially since so many of them go through their own experiences of having to confront this heteronormative, cis-centric narrative that just doesn’t fit them and their lives.

So some good queer history authors are: John D’Emilio (comprehensive, if a bit male-centric), Lillian Faderman (writing all about lesbian history, including more recent history; very well-respected; she’s got some issues in her scholarship that by no means discount it as a whole, but I’m happy to talk more about if you want), Michael Bronski (his Queer History of the United States is really accessible), George Chauncey (it’s just of NYC, but still fun), Estelle B. Freedman, Foucault (though it’s not quite “history,” it’s a kind of history meets theory of regimes of power and how sexuality got tied up in that), Martha Vicinus (I adore her), Valerie Traub (goes all the way back to the early modern period), and so many others who really focus more on niche history, so I won’t list them here. There are some web resources, but I know a lot of them are databases that are subscription-based. I’ll see what I can’t dig up in the next couple of days as far as free websites. I know they exist; it’s just a matter of having the time to look…

Okay, you didn’t specifically say you were interested in literature but bc I taught literature and think it’s a great way to learn about the history of a group, I’m gonna list some anyway and you can feel free to disregard!

Patricia Highsmith, The Price of Salt (or Carol, depends on the year it was printed) – you can also check out the movie! I find the two to be complementary (the book gives you Therese’s POV almost exclusively, whereas the movie shows much more of Carol’s story)

Alison Bechdel, Fun Home is her graphic novel/memoir that’s really excellent, but the comic strip that sort of launched her as a public persona (at least within the lesbian community) was Dykes to Watch Out For, quite a bit of which is available for free online

Henry James, The Bostonians – one of the first recognizable depictions of a queer female character in literature (not really…I’d trouble that as a professor, but that’s how it gets taught in general, and it was one of the first books where even contemporary reviewers were quick to note that there was something “wrong” or “morbid,” which was 19th C. code for what would come to be understood as lesbian sexuality, about Olive Chancellor) – free online, though it’s James at his most….Jamesian, which means it’s not that accessible

The poetry of Emily Dickinson! It’s all free online. There’s a ton of it, though much of it isn’t obviously queer

James Baldwin, Giovanni’s Room – gets into bisexual identity in a way a lot of works don’t do; on the sadder side…fair warning

Virginia Woolf! Especially Orlando or Mrs. Dalloway – the former has been called “the longest and most charming love-letter in literature” (to Woolf’s longtime friend and lover, Vita Sackville-West) and deals with the fluidity of gender and time; the latter has quite a few flashbacks to the brief childhood romance of the protagonist and her friend. Both of them are great, but Woolf, as a modernist, can have a writing style that’s difficult to get into at first (for instance, time really isn’t stable or linear, which is something I adore about her, but definitely takes some getting used to). They’re both available free online through Project Gutenberg

Radclyffe Hall, The Well of Loneliness – it’s a classic, in the sense that it’s one of those books people sort of expect you to have read if you do lesbian literature. It’s certainly an interesting story and told well, but it’s not even close to a happy ending and is rather conciliatory to prevailing norms (though even still it was taken to the courts under the obscenity laws) - free online, though!

Sarah Waters – a contemporary novelist who writes almost all historical fiction about queer women! Some of her stories are better known (e.g. Tipping the Velvet), but they’re pretty much all great. Varying degrees of angst, but definitely an accessible read

Maggie Nelson, The Argonauts – sort of experimental in form (it’s fiction with footnotes!); it deals with a lesbian woman coming to terms with her partner’s transition and her own identity during the process

E.M. Forster, Maurice – even though it was first drafted in the 1910s, Forster edited it throughout his life, and, given the subject matter, which was also autobiographical, and the prevailing attitudes at the time, the book was only published posthumously in the 70s

Colette’s Claudine series – it’s long (multi-volume) but sort of a classic – they’re all old enough to be free online, though the English translation is harder to come by

Eileen Myles – lesbian poet and novelist – I’d recommend Inferno but some of her poetry is free online

Rita Mae Brown – Rubyfruit Jungle and Oranges Are not the Only Fruit are both quite good, though, especially the latter deals with religiously-motivated homophobia, so I know at least my girlfriend, who dealt with a lot of that from her family, opted not to read it for her own mental health.

Tony Kushner, Angels in America – this two-part play deals with the AIDS crisis in America – it’s been turned into a TV miniseries, a Broadway play, and a movie, some of which are available online

Really anything by David Sedaris or Augusten Burroughs – both are gay authors who deal a lot with short stories (a ton of memoir/autobiographical stuff) – the former is a bit funnier, but they both have enough sarcasm and dry wit even in dark situations to make them fast reads

Alan Ginsburg’s poetry

Walt Whitman’s poetry (though it can be really fucking racist)

Binyavanga Wainaina, One Day I Will Write About This Place – does deal with issues of sexual abuse as a warning

Anything by Amber Hollibaugh (she writes a lot about class and butch/femme dynamics – quite a bit of her stuff has been scanned and uploaded online)

Michelle Tea – was a slam poet; recovering alcoholic; fantastically funny and talented author and delightful human being if you ever get the chance to meet her or go to one of her readings

Randy Shilts, And the Band Played On – more a work of investigative journalism than anything, the work is a stunning indictment of the indifference of the US government during some of the worst years of the AIDS crisis, but it also provides a good bit of gay history

Terry Galloway Mean Little Deaf Queer – deals with one woman’s experience of losing her hearing and navigating the world and the Deaf and deaf communities as a once-hearing person – she’s sort of acerbic and always funny;

Jeffrey Eugenides, Middlesex – grapples with intersex identity in a way that’s still far too rare in literature

Theodore Winthrop, Cecil Dreem – just rediscovered about two years ago, this is one of the few pretty happy gay novels from the nineteenth century! Free online!

Leslie Feinberg, Stone Butch Blues – pretty clear from the title, but deals with a butch character’s struggles with gender identity (takes T to pass for a while, but then gets alienated from the lesbian community; eventually stops taking T, but still struggles with what that means for her) – Feinberg’s wife made it free online for everyone after Feinberg’s death (the book had a limited print run, which made finding copies both hard and expensive)

Harvey Fierstein, Torch Song Trilogy – trilogy later adapted for film about an effeminate gay man (who also performs as a drag queen) and his life and family

Oscar Wilde – his novels aren’t explicitly gay, but they often dance around it thematically, at least; his heartbreaking letter, De Profundis, which he wrote to his lover while imprisoned for “gross indecency,” is available online

Anything by Dorothy Alison

Audre Lorde, Zami: A New Spelling of My Name - great as a memoir and a cultural history

There’s so many more but this is so my jam I suspect I’ve already rambled too long

If you’re interested in film, here are a few:

Paris Is Burning (a film about drag ball culture in NYC)

Fire – Deepa Mehta (it’s on YouTube in the US)

Boys Don’t Cry – there is a lot of homophobia and transphobia in the film, so it’s definitely one you’ll want to be in the right mindset to watch (I, for one, have only watched it once)

But I’m a Cheerleader – over-the-top mockumentary-esque film that satirizes conversion therapy and the Christian “documentaries” that claimed to showcase their successes (RuPaul is in it as well)

Desert Hearts – one of the earliest films to leave open the possibility of a happy ending for the lesbian couple

Hedwig and the Angry Itch – deals with gender identity and feelings of not belonging (also a fabulous musical)

Philadelphia – about one man’s experience of discrimination while dying of AIDS

There are plenty of lighter films, but I figure these tend to also talk more seriously about some issues as well

I don’t know if anyone but me made it to the end of this post, but there’s also so much fun queer theory out there that I won’t get into here, but I’m always up for giving more recommendations!

#ask me#anon#professor rambles#lgbtq history#lgbtq literature#book recommendations#film recommendations

75 notes

·

View notes

Link

The following blog post, unless otherwise noted, was written by a member of Gamasutra’s community.

The thoughts and opinions expressed are those of the writer and not Gamasutra or its parent company.

This post is co-authored by Pietro Polsinelli and Daniele Giardini.

In this post we discuss two themes:

How to facilitate writing for games?

Given that writing say partially generative in-game dialogue is a specific process, how can one minimize the impact on writing of values from state and output variations technicalities?

and

How to design an in-game dialogue user interface?

Designing in-game dialogues doesn’t seem to generally get much attention with respect to other kinds of game assets. We look at existing usages and we point out features to be considered when designing dialogues’ user interface.

A note on the use of the author’s point-of-view. We sometime write as “we”, in the outlining sections, and sometime use “I” as a part may be one of the authors writing his direct experience, be it Daniele or Pietro. Bare with us - him - me :-)

Stories are remarkably useful tools for creating good games, Bogost aside. But writing for games is hard for several different reasons.

In The future of dialogue in games Adam Hines is quoted:

Writing for games and writing for anything else is a totally different job. It’s more like trying to solve a very complex mathematical problem than it is a pure writing exercise.

Most media have a predetermined, linear, progress. Even when the writer tries to hide this under a complex narrative, there's only one way to go from beginning to end. Under this aspect, games are a completely different medium: writing a game means dealing with mutations, branching narratives, and is a sort of chaos theory applied to storytelling.

Hence the writing style for games needs to be quite specific - this is from Writing for Animation, Comics, and Games:

Animation, comics, and games fall into the category I think of as “shorthand” writing. This is in contrast to prose writing, where a writer can write plot, description, and dialogue to any length, and can cover all of the senses—sight, sound, touch, taste, smell—using both external storytelling (description, dialogue) and internal storytelling (thought processes, emotional description).

This specialized form of “shorthand” writing requires the discipline to write within a structured format; to pare description down to an absolute minimum; to boil dialogue down to a pithy essence; and to tell concise, tightly plotted stories.

In the following we consider how shorthand writing merged with state and variations handling can be smoothened for writers using specific tools. Methodological advances in how writing can be prototyped and tested can make a crucial difference in the quality of results (see How We Design Games Now and Why for an historical perspective) and so adding practical writing applications to your toolset can be useful.

Another feature of writing for games is that it has specific properties in the testing process: when you write say a short novel, you can do testing by printing drafts on paper, or reading it out loud, but in all cases you are working on a unique draft. In the case of in game state you need a way to do quick testing and changes while testing multiple possible results.

For example this allows testing of the logic of what your characters end up saying in different situations.

Narrative in games can solve problems - but it must be capable to relate and change in connection with dynamic state.

Here is a problem described by Daniele that having a dynamic flow tool that supports interactive writing and testing can probably help to solve:

As a short out-of-theme anecdote, Pietro wanted me to write about one thing I mentioned in our talks, a thing that always kinda annoys me, and which represents a good example of bad flow. It's what I call the "wall of NPCs" effect, which is typical of RPGs but also of some adventure games.

It's when, for a few hours, you went around exploring and met no more than a couple people to talk to, then suddenly you reach a city. And kaboom, tons of people appear and, if you're a completionist / narrative - explorer like me, you HAVE to talk to each and every one of them. If the group of people was small, let's say four people, it would be a welcome change in pace. When the group is city-sized though, the flow completely breaks and you simply enter the "wall of NPCs" section of the game, which I find to be both interesting and stressful, mostly because all these people are not introduced gradually, but as a sudden presence, a feat, you have to overcome.

One solution to this problem is already used by less dialogue-centric games, where most NPCs are idiots with nothing to say. This removes depth from the characters, but keeps the flow, uh, flowing, since the player doesn't see them as a weight anymore. Still, I'm sure there's better solutions for more dialogue-centric games. Just something to ponder about.

So let’s have a look at the existing writing tools for games.

Inkle’s Ink

A remarkable tool that allows all above is Inkle’s Ink, presented generally by Jon Ingold here and in more technical detail in this GDC’s talk by Joseph Humfrey.

Ink is free and open source, just download it, install and there you go. Writing is linear (top down), the syntax is a markup language of sorts, and you control everything directly from text.

This is how Ink’s author sums it up:

Possible problems with this (wonderful) tool is that it seems really hard for anyone to get what is happening in anybody else’ writing, and possibly the writer herself could get lost when the text gets longer.

Dialogue as flow graph

A different approach is to write by creating nodes of a connected graph on a plane, as in the pictures below.

Night School Studio’s Oxenfree dialogue editor - image from The future of dialogue in games.

Daniele’s Outspoken (see below).

In a recent podcast by Keith Burgun interviewing Raph Koster, the latter made a wonderful casual observation about IDEs (Interactive Development Environment, Unity's in particular) embodying in their evolution some principles of game design. In the case of Unity, some of this learning by the IDE structure is built-in, and sometimes it is provided by third-party extensions. For the case of writing tools for games, let’s see an example from one of the author’s: Daniele Unity’s plugin Outspoken.

Outspoken

A while ago I (Daniele) found myself in need of a dialogue editor to use in Unity. I'm sure there's some marvellous in-house editors out there, but for what concerns publicly available stuff, I couldn't find anything that suited my tastes, most of all because all editors were pretty writer-unfriendly (except Ink, which is great but is missing a quick visual/organizational side which for me is—totally subjectively—fundamental). So I started the taxing feat of making my own internal dialogue editor, Outspoken. Please note that this is not advertising for Outspoken, especially because it is internal/for-friends-only. It's just a good example of the philosophy behind an in-house dialogue editor which I obviously know extremely well.

So. The philosophy I decided to follow for the editor:

1. It must be, first and foremost, writer-centric.

As a writer, I will write directly inside it, so I want its flow to be fast, easy to read/use, and pleasant. If my focus is lost and I'm distracted by the usage/complexity of the editor, the coherence and verve of my writing will resent it.

2. It must be fun to use, almost giving the writer the feeling of a comic.

Because this editor is very personal to me and I'm a comic writer too, so that mindset works perfectly for me.

3. Nice to the eye, no cluttering UI.

A dialogue node shouldn't be cluttered with encumbering UI, and should be as small as possible. In the end, I decided to hide all UI that is not always necessary (which means a lot of it) unless ALT is pressed.

4. Keyboard shortcuts for the win.

They allow to write without moving your hands back and forth between mouse and keyboard, which is a focus-breaker.

5. It must obviously have all necessary features, and be expandable.

"Necessary" as in "what I personally deem necessary" :P Which means actors, audio clip references, a custom in-dialogue scripting language, in-dialogue text blocks either randomized or chosen from variables/gender/etc, localization, global and local variables, etc.

It was a lot of work, but I used it for a few games and I can say I'm pretty happy with it (and the few friends that used it, Pietro first among them, seem happy too). Clearly, I'm also constantly evolving it.

How to design beautiful dialogues in games? Here we begin by presenting some example of existing in-game dialogues and then describing what we learned from developing several projects with such dialogues.

Learn from comics

I (Daniele) come from a strong comic culture. I loved, studied, cherished, all forms of comics — and also made tons of them. Thus when I made my first mini-adventure, Faith No More, it felt natural to me to look in that direction and start experimenting.

There's one thing comics understand very well, out of necessity. Lettering/written-dialogues are, or should be, an art. They can be used to convey emotions, mystery, fascination, as much — sometimes even more — as the text they display. Videogames instead, either consider text as mere subtitles, even when there's no audio, or as a beautifully printed paragraph from a book, sometimes surrounded by a multitude of decorations (there's just few recent exceptions I can think of, like Night in the Woods and Oxenfree, both inspired from comics). In short, every dialogue is, if not a wall, a brick of text. And that's bad: lettering can be so infinitely better. Both in how it displays text and in how it composes its elements, pulling them apart, shrinking and distorting them, giving a director's touch to their flow. Just look at these wonderful works — please enlarge those images to watch them in full glory.

Cerebus: Dave Sim and Gerhard

Snapchat: Chris Ware

Arkham Asylum: Grant Morrison, Dave McKean, lettering by Gaspar Saladino

Giallo Scolastico: Andrea Pazienza

Elektra Assassin: Frank Miller, Bill Sienkiewicz, lettering by Jim Novak

Obviously, comics have it easy. Everything is—kind of—created altogether in there, with perfect knowledge of each, utterly static, element. Videogames instead live in a dynamic state, with lots of variables messing things up. They're much more complicated. So I'm not saying, "Look at them comics! Let's just make dialogues like they do!" I'm just saying it's a pretty cool visual culture to start from, in order to find one's own way.

Learn from games

Let’s start with a negative example, or “how not to do it” / the standard way / the obvious way: I (Pietro) chose The Banner Saga, because it’s a wonderful game and also its narrative flow is a marvel but its dialogue user interface may be its less curated feature, as you can see from the screenshots:

The great quality of the graphic design of the game is a bit in contrast with the dialogue and ensuing choices UI. It looks like the designers have a cinematographic sensitivity, that does not consider “user interface” as deserving design attention beyond the basics.

A (very) positive example of user interface for in game dialogue is Night In The Woods (best comic-based example in our opinion - it's just beautiful):

As Night in the Woods dialogues are explored best when seen in animation (and that already tells something), check out this: 24 Minutes of Gorgeous Night in the Woods Gameplay.

For each of the examples we’ll list a recap of the design choices is expresses.

Choices for the user interface: text all caps, fixed font size, animated background, left aligned.

In 80 Days, there are two kinds of dialogues. The most used is a flow of pure text in a graphic context:

And a second less used style is with characters on the side:

Choices for the user interface: sentence case, no balloon, left aligned on left and right aligned on right.

Now let’s see three examples of user interface for in game dialogue we (the authors) developed.

Faith No More + Nothing Can Stop Us - link

Notes on the user interface: (Daniele) apart from the comic-based approach, the interesting thing here is the choice of leaving previous balloons present in the background. In my opinion, this helps readability, since the player can see a partial history of the dialogue (still, in a new game I'm working on, I'm scrapping this "history" concept to have single animated balloons, so it all depends on the context—see work-in-progress example of a "thought balloon" below).

In hindsight, I have to say I find the dialogue user interface of the two pictures above as nothing more than interesting experiments, still lacking a lot of the depth and charm they should strive to achieve. The one on the bottom is already going in a better direction. Whew, did I write too much here? Pietro never scolds me and then this is what happens!

Football Voodoom - link

Choices: centered balloon text, fixed font size, standard “sharp” pointer, slight bounce of talking character.

The above dialogue design examples draw ideas and techniques from comics and game feel (see An Incomplete Game Feel Reader to learn about the latter). What is the conclusion?

The conclusion is that there is no conclusion. What are you, crazy, in thinking the creative work of crafting a dialogue user interface can be concluded anyhow? It's a constant never ending work in progress, and being inspired from comics is just a suggestion, mostly to point out a different creative direction than the "widely accepted and standardized" one :-) But games are games, not comics nor books nor movies, so it's an open ground for experimentation and for bringing your own personality in play. Cheers!

You can follow Daniele and Pietro on Twitter.

0 notes