#treaty principles bill

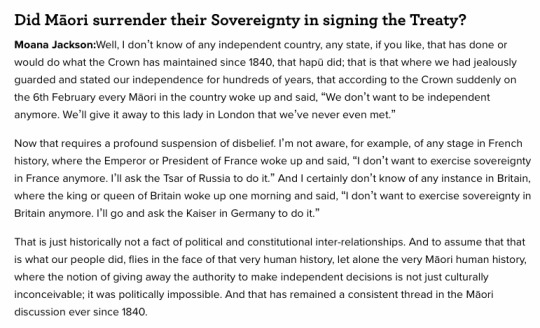

Text

THE GODS HATE HIM TOO

"I am māori so I couldn't be doing anything to them uwu"

Text: Act Party leader David Seymour came a cropper on his electric bike in Auckland's Parnell on Sunday, and says he got a lot of help from passersby - but one onlooker was not quite so supportive.

Seymour was cycling on Parnell Rd after leaving the Holy Trinity Cathedral’s Commonwealth service in the early evening.

“I just didn’t see a car. It wasn’t their fault, they had right of way. So I slammed on the brakes and realised I was going to cartwheel over, but I also realised I was still going to hit the car so I slammed on the brakes harder and over I went.”

Seymour says he did not hit the car, and the people in it stopped and came back to check on him. “They were mortified, but it wasn’t their fault.”

He was unhurt other than the shock and a sore wrist that he hoped would heal quickly. A number of people turned up to check on him, bringing out water and offering him a ride home.

However, there was one negative reaction to his plight.

“While I’m sitting on the traffic island in a state of shock, some guy comes over and starts filming me. I thought ‘that’s a bit weird’ and then he says ‘you know what, sometimes you get exactly what you deserve”.

“In a [British] accent, he said ‘look what you’re doing to Māori, you’re just a trust fund baby who’s out of touch with reality.”

“I thought ‘I am Māori, and I don’t have a trust fund’.”

Seymour has been prominent this year for pushing his Treaty Principles Bill, which attempts to define the principles of the Treaty of Waitangi, and the coalition government has also told government departments to use their English titles ahead of the te reo Māori title.

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

OPINION: The national hui at Tūrangawaewae Marae saw 10,000 people united in the face of actions by the coalition government, including its proposed Treaty Principles Bill. John Campbell was there.

History happens on single days.

Yesterday, at Tūrangawaewae, will be one of them.

“Why are you here?”, I asked Tame Iti.

“Vibrations”, he replied.

The rest of us will feel them over the days and months and years ahead.

Initial estimates of how many people would come had begun at 3000. Then 4000 registered, so estimates grew to 5000. Then 7000. By lunchtime, organisers were saying 10,000 had arrived. There wasn't room inside for them all. A large marquee across the road was full, all day. Every seat, everywhere, was taken. There was hardly standing room.

This special place, which has held tangi for royalty, which is where the Tainui treaty settlement was signed, which was visited by Nelson Mandela, and Queen Elizabeth II, and many of our greatest rangatira, has seldom seen so many people.

But no one objected. To standing. To the steaming heat. To the fact that sometimes people were too far away from the speakers, or the screens relaying them, to hear.

New Zealand First’s deputy leader, Shane Jones, told RNZ the hui could turn into a “monumental moan session”.

But it didn’t. Somehow, the word I keep coming back to is joyful.

The National Hui for Unity it was called. And it felt like exactly that.

On the way to Ngāruawāhia early yesterday morning, I pulled into a truck-stop near Bombay, at the southernmost end of the Auckland motorway system, to meet the Ngāpuhi convoy travelling down from the far north.

Some had begun their journey way up, in Kaikohe, at 3am. They spilled out into the half light of an overcast morning and inhaled the beginning of what would be an extraordinary day.

It’s easy for the significance of this delegation to be lost amid all the other arrivals. The people who’d come from even further away. Iwi after iwi. Ngāpuhi, Ngāti Porou, Tainui, Ngāti Kahungunu, Ngāi Tahu, Te Arawa, Ngāti Tūwharetoa, Ngāi Tūhoe, Ngāti Maniapoto – the big ten, all there, in declaratory numbers.

Just a few members of the Ngati Porou contingent who drove over on Friday from Tairāwhiti to attend the hui.

Ngāi Tahu representatives had taken a huge journey by road, then Cook Strait ferry, then road.

A friend’s father flew up from Invercargill.

But the size and standing of Ngāpuhi’s delegation provides some insight into how very significant this hui was.

Ngāpuhi aren’t a Kīngitanga iwi. They don’t see Kīngi Tūheitia as their king. And they contain Waitangi within their broad, northern boundaries – home, of course, to the Waitangi commemorations, our most famous form of national hui.

And yet they came, hundreds of Ngāpuhi. Some wearing korowai made especially for the occasion. Some the direct descendants of Treaty signatories. A waiata, composed for the hui, rehearsed beyond newness into a heartfelt and singular voice.

“Why are you going?” I asked Mane Tahere, the chair of Te Runanga-Ā-Iwi-Ō-Ngāpuhi. “It feels significant that Ngāpuhi are attending in such numbers.”

“Because”, he answered, “the challenges we face do not discriminate amongst iwi. We held three hui to discuss whether we should come, and who would come, and what our message would be. The final hui was only last Saturday. I wouldn’t have put our rūnanga resources into something we didn’t collectively support. This was hapū rangatiratanga. Hapū after hapū spoke and said we should go.”

Why?

“Because the question we have to ask as Māori is how we activate ourselves, re-activate ourselves, for 2024? How do we say to the coalition government, ‘hang on, what do you mean, and what are you doing?’ And the best way to do that is to do it together. Now is the time for Māori unity.”

The National Hui for Unity was only called by Kīngi Tuheitia Pootatau Te Wherowhero VII (Kīngi Tuheitia) at the beginning of December. That so very many people would arrive here, only six weeks later, in the holiday-season slowness of the third week of January, speaks not only to how resoundingly those present reject the coalition government’s Treaty Principles Bill, but also to a strength of unity already existing.

That is to say, a unified rejection of what Kīngitanga Chief of Staff, Archdeacon Ngira Simmonds, described as the “unhelpful and divisive rhetoric” of the election campaign.

“Maaori can lead for all”, said Ngira Simmonds, at the beginning of this month, “and we are prepared to do that.” *

This is part of a growing sense, as Ngāpuhi’s Mane Tahere told me, that “we’ve turned a corner”.

The corner is that u word – unity. The increasingly urgent sense of the need for a collective response to the coalition government.

And, without great external fanfare, these relationships have already been building.

The Kīngitanga movement has begun sending some of its most senior figures north for Waitangi Day commemorations – into the heart of Ngāpuhi country. And again, like Ngāpuhi coming to Ngāruawāhia, this reflects a belief that by Māori for Māori, all Māori, is the strongest possible response to a government they fear is intent on division.

This year, for the first time since 2009, Kīngi Tūheitia himself (who has Ngāpuhi whakapapa on his father’s side) will be attending Waitangi.

Symbolic? Yes.

Significant? Yes.

Unity.

Mana motuhake (self-government).

“Look at all these people,” Tame Iti said to me. “They’re here to listen. To learn. The first layer of mana motuhake is yourself.”

All protest is a form of risk.

Risk that it goes awry – and costs support, rather than galvanises it.

Risk that it arms your most cynical critics with the material for derision or contempt.

Risk that no one notices. Or that the turnout is so small that those who have the luxury of being able to not protest can turn away.

Some politicians may tell you that 10,000 people is not very many. I would say otherwise. In 30 years of covering politics, I have never attended a New Zealand party-political rally that attracted anywhere near that many. Or even half that number.

What happened at Tūrangawaewae yesterday was a triumph for all those involved.

In the striking heart of the mid-afternoon, I passed Tukoroirangi Morgan, the chair of the Waikato-Tainui executive board. We were going in opposite directions over the sunburnt road.

Chair of the Waikato-Tainui executive board Tukoroirangi Morgan.

Chair of the Waikato-Tainui executive board Tukoroirangi Morgan. (Source: 1News)

“How’s it going, Tuku?”, I asked him.

“It’s amazing”, he replied. “All these people.” And then he stopped, looked out over the everyone, everywhere, and repeated himself. “Amazing.”

Tūrangawaewae is located just outside Ngāruawāhia, directly across the Waikato River from the shops in that little township. Somewhere, just to its east, the new Waikato Expressway has stolen many of the estimated 17,000 cars a day that once passed through here. For decades, Ngāruawāhia was a pie and petrol stop on the main road between Hamilton and Auckland.

Not so much, any longer.

The challenge of history is to survive it.

And Kīngitanga itself was a kind of survival strategy.

It wasn’t this simple, of course, but a famous saying of the second Māori King, Tāwhiao, broadly speaks to the hopes of the Kīngitanga movement: “Ki te kotahi te kākaho ka whati ki te kāpuia e kore e whati.” The Māori Dictionary translates it prosaically: “If there is but one reed it will break, but if it is bunched together it will not.”

Yesterday, the reeds felt tight and strong.

“Why are you here?” I asked people, over and over.

The answer was almost always a variation of what Christina Te Namu told me. Christina, too, is Ngāpuhi. “I just wanted to support our people”, she said. “Now is the time for us to stand together as one.”

A group of women from Ngati Porou stopped to say kia ora.

It seems almost inadequate to state it like this, but they were there to be there. They had driven from Tairawhiti because being there mattered. Every person I spoke to had come to be part of this declaration of solidarity.

'An attempt to abolish the Treaty'

On Friday morning, something happened that gave this already significant day a vivid, extra weight.

My 1News colleague, Te Aniwa Hurihanganui, obtained details of the coalition Government’s Treaty Principles Bill. In its initial form it is not so much a re-evaluation of the role of the Treaty as an abandonment of it. Professor Margaret Mutu, speaking on 1News on Friday night, called it “an attempt to abolish the Treaty of Waitangi.”

This has arisen out of National’s coalition agreement with ACT.

I wrote about this at the end of last year, and also in the weeks after the election. I looked at the coalition agreements between National and ACT, and National and New Zealand First. And I noted their pointed focus on Māori. Some of it felt mean. What I called a strange, circling sense of a new colonialism.

I wrote about what I saw as ACT and New Zealand First's experiments with a kind of "resentment populism".

Who are we?, I asked. And where are we heading?

We’re heading to National reaching 41 percent in the first political poll of the year, “a massive jump”, as Thomas Coughlan described it in the NZ Herald, earlier this week. And we’re heading here, to Tūrangawaewae, and to thousands of people who travelled from throughout the country to collectively say, “no”.

In other words, we’re heading towards, or have already arrived in the vicinity of what PBS called the “divide and conquer populist agenda”.

And we’re heading to politics that purport to speak out against division, whilst arguably fomenting it.

In an opinion piece by David Seymour, published in the NZ Herald on Friday, the ACT leader begins with the sentence, “If there’s one undercurrent beneath so much of our politics, it’s division”.

Is David Seymour responding to division, or causing it?

The Treaty, he said, in December, “divides rather than unites people, as most treaties are supposed to do.”

But whose endgame is division? Really?

I've written before about the kind of populist politics that drive people to division, then throw up their hands and yell, “LOOK! DIVISION”, having wished for exactly that.

This, as Australian Academic Carol Johson wrote in The Conversation after the “no” vote in Australia’s Voice referendum, speaks to “a conception of equality controversially based on treating everyone the same, regardless of the different circumstances or particular disadvantages they face.”

That's equality as David Seymour consistently claims to define it.

But do as they say, not as they do. There was a time when ACT received some handy support from National. Remember that famous cup of tea? Surely Seymour's idea of equality would have insisted that Act get trounced than receive a leg-up?

The fascinating thing is that populism is typically structured around “the claim to speak for the underdog and the critique of privileged 'elites' and their disregard for the needs of ’ordinary people’".

But it’s hard for National to occupy that space when the party has historically been supported by the “elite”, and when your leader is a former CEO who owns seven properties, and who received total remuneration of $4.2 million in his last full year at Air New Zealand.

So, you can do two things. You can outsource populism to your coalition partners. (And sit there with a face of injured innocence, like someone insisting it was really the dog who farted.) And you can allow coalition partners to redefine the definition of “elite”.

No-one does this more enthusiastically than Winston Peters.

During the months prior to the election, the New Zealand First leader said “elite” more often than Kylie Minogue has said “lucky”.

“Elite Māori”, “elite power-hungry Māori”, “an elite cabal of social and ideological engineers.”

The idea, as I wrote after the election, is to somehow persuade us that Māori are getting something the rest of us are not. And they are: a seven-years-shorter life expectancy, lower household income, persistent inequities in health, the greatest likelihood of leaving school with low or no qualifications, and an over-representation in the criminal justice system to such a great extent that Māori make up 52 percent of the prison population.

Elite as.

So, had this hui erupted into a kind of rage, would that have been a victory for populism? Would the divisions have become entrenched? Would Māori have been blamed for reacting to provocation, rather than the provocation itself being examined?

None of this is new. Which is why Māori recognise it.

In July 1863, the Crown issued a proclamation demanding: “All persons of the native race living in the Manukau district and the Waikato frontier are hereby required immediately to take the oath of allegiance to Her Majesty the Queen”.

And those who wouldn’t?

“Natives refusing to do so are hereby warned forthwith to leave the district aforesaid, and retire to Waikato beyond Mangatawhiri.”

And anyone “not complying with this Order… will be ejected.”

Vincent O’Malley, in his remarkable book The Great War for New Zealand describes what happened next.

“On the same date some 1500 troops marched from Auckland for Drury.”

The troops didn’t stop. There are few more egregious and cynical predations in our history. South they went. Without just cause or provocation. Into Waikato.

Ngāruawāhia, Vincent O’Malley tells us, was “strategically important during the war because of its location at the confluence of the Waikato and Waipā rivers.”

“By 6 December 1863, Ngāruawāhia (‘the late head quarters of Māori sovereignty’ as one reporter dubbed it) had been deserted.”

At four o’clock that afternoon, a British flag was hoisted there.

And why does this story matter, still? 160 years later.

Because the Crown used the requirement for “allegiance”, the demand that Māori be loyal to it, so disingenuously. The language of colonisation purported to be about governance, about the role and rule of a single law, but it was a violation of law and a betrayal of the principles of government.

By the end of this rule of law, roughly 1.2 million acres of Waikato land had been “confiscated”.

And any opposition to it was defined, in law, as “rebellion”. And rebellion was justification for seizing more land.

This is our history. And part of it happened here, where the 10,000 people met yesterday.

It was so hot by late morning that people were swimming in the Waikato River.

I wandered down from the crowds at the hui to talk to the people swimming. They were mostly young, although not all.

I met a ten year old who told me her parents had brought her so she could “find out where I’m from”.

She was from Waitara, in Taranaki, so this wasn’t a literal homecoming.

I wondered how many people had travelled big distances to have a new or reinvigorated sense of what it means to be Māori.

Heading back inside, I saw Professor Margaret Mutu.

There are few who have more rigorously applied their formidable intellect to making sense of the intersection of Māori and colonisation.

Professor Margaret Motu: "You have two parties to a treaty, and one of them can’t unilaterally redefine it."

She is of Ngāti Kahu, Te Rarawa, Ngāti Whātua and Scottish descent. She is Professor of Māori Studies at the University of Auckland. And, her university profile tells us, she holds a BSc in mathematics, an MPhil in Māori Studies, a PhD in Māori Studies specialising in linguistics and a DipTchg.

There was nowhere quiet for us to sit. But people kindly made space at the back of a kitchen prep area. And I asked her about the significance of the Treaty, for Māori, for the Crown, and for us all.

“Te Tiriti is where you go," she said. “When things look as if they’re not working for you, you have a protection, and that’s where you go. It will always look after you. It will always protect you.”

“And while it seems clear that this government wants to abolish the Treaty," Margaret Mutu continued, “that can never happen. For one thing, you have two parties to a treaty, and one of them can’t unilaterally redefine it. But also, our tūpuna were very, very wise. In the Treaty they invited Pākehā, the British, to come and live with us. But they had to live with us in peace. In peace and friendship. And that’s what the Treaty is. It’s a treaty of peace and friendship. You can’t redefine that. You can’t rewrite that. It was very wise and it was very clear.”

And here’s where Margaret Mutu helped me understand why the mood at Tūrangawaewae was so – and I wish I could find better words – hopeful, positive, constructive.

Manaaki manuhiri: to support and care for your guests.

“We invited Pākehā to live amongst us,”, she said. “And what a lot of our Pākehā friends don’t understand, I think, is that our tikanga requires us to manaaki manuhiri. And that’s about looking after everybody. Everybody. So even when we have hate thrown at us, we have to assert aroha. That’s what manaaki manuhiri requires, even when people are very badly behaved.” Margaret Mutu laughs at this. “So, people have come here today to find that strength. It’s not about fighting people. It’s to find that strength and unity to be able to rise above the hatred. And now we will just get on and do exactly that.”

After lunch, I was invited to meet the King.

I’ve never been inside Tūrongo before, the royal residence. Or Māhinaarangi, which is both a famous meeting house and a unique kind of museum.

It looks out over the marae. And it gently contains, as if nestled in the palm of a large, open hand, photos and remembrances of those who’ve come before. The people who built Kīngitanga. Tāwhiao is there, his photo looking down from the wall. He died 130 years ago. How he would have marvelled, with great pride, at such a gathering, and perhaps, also, despaired at it still being necessary, in 2024.

Ngira Simmonds took me in. And I found myself, shy for once, able to stand and look out, viewing the unfolding of this new history from a place that is so central to the story of the history of us.

Kīngi Tuheitia was beaming.

“I didn’t sleep last night”, he told me. “But I knew this was the time for us to come together. And we have. We have.”

It occurred to me, as I walked back to stand amongst the thousands Kīngi Tuheitia was looking out to, with such delight, that the hui was the actualisation of Tāwhiao’s hope for the unbreakable strength of reeds tied together.

What was was happening felt transformative in the very fact it was happening. The mana motuhake of 10,000 people.

The vibrations.

Will the government feel them?

Will they survive the divisions of populism? Of politics that echo our repeated capacity to claim we are governing to unite people whilst governing against Māori?

Or maybe, this is how it all begins. In an historically large display of unity.

Rātana follows. Then Waitangi.

Yesterday ended with Kiingi Tuheitia speaking.

“The best protest we can do right now is be Maaori. Be who we are, live our values, speak our reo, care for our mokopuna, our awa, our maunga, just be Maaori. Maaori all day, every day. We are here, we are strong.”

The reeds tightening.

*Macrons haven't been used when quoting Tainui, who choose not to use them.

fantastic article on the national hui in response to aotearoa’s assault on indigenous rights. click through for pictures and video.

#new zealand#aotearoa#nz#nzpol#news#politics#indigenous rights#maaori#maori#land back#david seymour#waitangi#long post

33 notes

·

View notes

Text

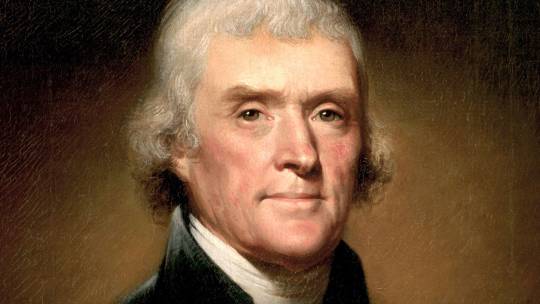

“France is in the throes of violent birth”: Thomas Jefferson and the 1789 French Revolution

"The deputies retired, the people rushed against the place, and almost in an instant were in possession of a fortification, defended by 100 men, of infinite strength..."

• Ambassador Thomas Jefferson report on the events on 14 July 1789.

The excerpt shown here is from a letter in Jefferson’s own hand to Secretary of Foreign Affairs John Jay. In great depth, he describes the events of July 14, 1789, including the storming of the Bastille in Paris. The Bastille was a symbol of the old regime, and housed arms, gunpowder, and prisoners.

On 14 July 1789, the U.S. Ambassador to France, Thomas Jefferson, was a witness to the events of a day in Paris that is commonly associated with the beginning of the French Revolution. Jefferson recorded the events of the day in a lengthy and detailed letter to John Jay, then Secretary of Foreign Affairs.

The American Revolutionary War began as a conflict between the colonies and England. In time, what began as a civil disturbance turned into a world war drawing France, Spain, and the Netherlands into the hostilities. France would send troops, ships, and treasure to support the American effort. During the war, one of the first priorities of the French government and its allies was to raise funds to fight the war.

When the Treaty of Paris was signed in 1783, France was virtually broke and on the edge of social catastrophe, the result of decades of war with England and other countries. The poor suffered hunger and privation. By 1789, revolution would come to France.

In 1785, Thomas Jefferson arrived in Paris to replace Benjamin Franklin, who was retiring as ambassador to France. At the age of 81, Franklin returned to the United States where he would serve as President of the Pennsylvania Assembly and also participated in the Constitutional Convention of 1787.

John Adams was reassigned to London where he would be the first American ambassador to the Court of St. James. Jefferson remained on duty in France until late 1789 when he returned to the United States. While in France, Jefferson reported on developments at the court of King Louis XVI, the country at large, and the rest of Europe.

Jefferson was sympathetic to the revolution, opening his home in Paris to its leaders and assisting his friend the Marquis de Lafayette with drafting the Declaration of the Rights of Man. As the first Secretary of State under the Constitution and George Washington, his support for France and the revolution continued.

His friendship to the Marquis de Lafayette, who served in the War of Independence and lived almost 10 years in the USA, became very important in the beginning of the French revolution. The Marquis was the General of the french forces 1789 and tried to prevent a civil war and turmoil. He corresponded with Jefferson, who came from a country with the same experiences. Jefferson and the Marquis agreed that France was not mature to become a republic but a constitutional monarchy, like in Great Britain. However, this was the decision of the national assembly, of which the Marquise was a member. Jefferson went daily to Versailles to inform himself about the decisions. During Jefferson’ s visits, they passed the following laws:

1. Freedom of the person by habeas corpus

2. Freedom of conscience

3. Freedom of the press

4. Trial by jury

5. A representative legislature

6. Annual meetings

7. The origination of laws

This totally fit to Jefferson’s principles. In addition, there was passed a bill, which was prepared by Lafayette and Jefferson and which abolish any title or rank to make all men equal.

Thomas Jefferson also helped his friend Lafayette to bring the different opinions in his party about the constitution to an agreement. France should become a constitutional monarchy.

However, after this, Jefferson recognised that he is not allowed to interfere in the French domestic affairs and that he should be neutral and represent his country. He left France in the thinking that the Revolution was over and that France would grow to a constitutional monarchy. Jefferson was proud of the achievements in France and after his return to USA he declared: “ So ask the travelled inhabitant of any nation, In what country on earth would you rather live? - Certainly, in my own where are all my friends, my relations, and the earliest and sweetest affections and recollections of my life. Which would be your second choice? France."

For all his francophile fervour, as the chief American diplomatic representative, Jefferson’s Enlightenment had been a conventionally English one, dominated above all by John Locke. And Jefferson’s first impressions of America’s principal ally in the Revolution were not positive ones. “The nation,” he confided to Abigail Adams in 1787, “is incapable of any serious effort but under the word of command.”

The stars of the French Enlightenment - Voltaire, Diderot, d’Holbach - were frivolous and useful only for manufacturing “puns and bon mots; and I pronounce that a good punster would disarm the whole nation were they ever so seriously disposed to revolt.”

The events of the spring of 1789 soon changed all of that before Jefferson’s very eyes. “The National Assembly,” he excitedly wrote to Tom Paine, “having shewn thro’ every stage of these transactions a coolness, wisdom, and resolution to set fire to the four corners of the kingdom and to perish with it themselves rather to relinquish an iota from their plan of a total change of government” had excited Jefferson’s imagination as nothing before.

Even when the Paris mob seized the Bastille and beheaded the hapless officers of the Bastille, Jefferson shrugged it aside as a mere incident, since “the decapitations” had accelerated the king’s surrender. As Jefferson would write later, “in the struggle which was necessary, many guilty persons fell without the forms of trial, and with them some innocent.” But rather than seeing the French Revolution fail, “I would have seen half the earth desolated. Were there but an Adam and an Eve left in every country and left free, it would be better than as it now is.”

Jefferson’s admiration for the French Revolution seemed to increase in direct proportion to his distance from it. And once he returned to America at the end of 1789, one of his chief motives for taking the post of Secretary of State was to observe and encourage the French eruption, when the National Assembly seized and redistributed the lands of the Catholic Church, when the king foolishly attempted to flee France, only to be captured, placed on trial and executed.

And when a Committee of Public Safety began a national purge - the “reign of terror” - Jefferson continued to describe the French Revolution as part of “the holy cause of freedom,” and sniffed that “the tree of liberty must be refreshed from time to time with the blood of patriots and tyrants. It is its natural manure.”

There is no question that Jefferson’s influence in the beginning of the French Revolution was very important. His initial moderate counsels and ideas helped in the beginning to prevent a civil war. His opinion that France was not mature to become a republic is probably right, because after 600 years of monarchy and aristocracy they people were not used to have any rights or take part in political matters. Jefferson thought that a republic had to develop from a constitutional monarchy. When you look to the cruel end of the French Revolution, Jefferson’s assessment was right up to a point.

Jefferson’s time as Secretary of State coincided with the most explosive phase of the French Revolution. What started as an attempt to dismantle the Ancien Régime and institute a constitutional monarchy blossomed into a radical experiment in creating an entirely new republican society. As his correspondence with Minister to France Gouverneur Morris and Minister to the Netherlands William Short during the emergence of the Jacobin Terror reveals, Jefferson responded to the violent radicalisation of the Revolution with enthusiastic support.

His advocacy for the French Revolution did not signify his emergence as a disruptive insurrectionist in favour of purposeless violence, anarchy and unbridled populism. Instead, he advocated for recognition and support of the Jacobin government as a successful international analog to the republican project he wanted to pursue at home at the expense of the “monarchical” aspirations of Hamilton and the Federalists.

In practice, the parallels he imagined between the ideal Jeffersonian and Jacobin republics were usually more apparent than real, as Jefferson often ignored the reports of Morris and Short in favour of fanciful idealising of his French counterparts – a problem Jefferson would only come to grips with in retirement.

Despite these dilemmas, Jefferson’s impassioned advocacy for the French Revolution proved effective, emerging as a cornerstone of the burgeoning Republican Party’s foreign policy and remaining important well into the early nineteenth century, until the Revolution ceased to be an important political issue. It was not until he became President in 1801 that Jefferson’s views toward France began to cool and became more pragmatic, highlighted by the Louisiana Purchase Treaty.

#thomas jefferson#jefferson#french revolution#14 july 1789#bastille day#america#france#french#monarchy#republic#history#politics#ideology#jacobin#essay#diplomacy#ambassador#jefferson in paris#paris

59 notes

·

View notes

Text

The the WHO lawyers are trying to play us, saying the nations are sovereign because they still make the laws. What the WHO omits saying is that under the Treaty and proposed IHR Amendments, nations will be forced to pass the laws that the WHO tell them to pass. Examples of this and other word games below.

First the treaty tells you that unhindered, timely access to information is a general principle. Then it adds the caveat that transparency means open access to “accurate” information.

Then a few pages later the treaty demands that nations perform “infodemic management”—which requires not only censorship, but also surveillance of everyone’s social media footprint, so the nation will know who and what to censor. This violates both the First and Fourth Amendments to the US Constitution.

Not only that, but the censorship should be performed with international collaboration—so all nations can target the same misinformatin spreaders and there will be nowhere to hide. Finally, they want to make sure you Trust the(ir) Science.

Below, the treaty is forced to admit that the so-called sovereignty that Tedros claims we will retain— the ability to pass laws—will in fact be subject to the orders of the WHO.

The WHO treaty draft requires that every nation pass laws to legalize Emergency Use Authorizations, so that unlicensed vaccines can be given to populations during a WHO-declared pandemic. You know, like a Monkeypox pandemic. There are no standards required and the WHO Director-General can declare any pandemic whenever he wants. Then the needles come out.

The WHO also demands that nations pass the laws needed to remove all liability from these untested and potentially deadly vaccines. Who’s sovereign now?

So you see, the WHO has just played a bunch of word games and they intended for us to be the suckers and go along, ignorant. So long as the Treaty and IHR Amendments still let nations make laws, the WHO insists on calling us sovereign. But the real sovereign is the one ordering that laws be passed. That’s the real power. Why would anyone give that up to the WHO, especially when its Director-General is a puppet for Bill Gates, is not a real doctor, and has been accused of withholding food and hiding 3 cholera epidemics to kill members of competing tribes in his native Ethiopia, when he was the #3 top official there? Do you really think he cares about your health during a pandemic?

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

Bill Bramhall

* * * *

LETTERS FROM AN AMERICAN

February 12, 2024

HEATHER COX RICHARDSON

FEB 12, 2024

Today’s big story continues to be Trump’s statement that he “would encourage [Russia] to do whatever the hell they want” to countries that are part of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) if those countries are, in his words, “delinquent.” Both Democrats and Republicans have stood firm behind NATO since Dwight D. Eisenhower ran for president in 1952 to put down the isolationist wing of the Republican Party, and won.

National security specialist Tom Nichols of The Atlantic expressed starkly just what this means: “The leader of one of America’s two major political parties has just signaled to the Kremlin that if elected, he would not only refuse to defend Europe, but he would gladly support Vladimir Putin during World War III and even encourage him to do as he pleases to America’s allies.” Former NATO supreme commander Wesley Clark called Trump’s comments “treasonous.”

To be clear, Trump’s beef with NATO has nothing to do with money. Trump has always misrepresented NATO as a sort of protection racket, but as Nick Paton Walsh of CNN put it today: “NATO is not an alliance based on dues: it is the largest military bloc in history, formed to face down the Soviet threat, based on the collective defense that an attack on one is an attack on all—a principle enshrined in Article 5 of NATO’s founding treaty.”

On April 4, 1949, the United States and eleven other nations in North America and Europe came together to sign the original NATO declaration. It established a military alliance that guaranteed collective security because all of the member states agreed to defend each other against an attack by a third party. At the time, their main concern was resisting Soviet aggression, but with the fall of the Soviet Union and the rise of Russian president Vladimir Putin, NATO resisted Russian aggression instead.

Article 5 of the treaty requires every nation to come to the aid of any one of them if it is attacked militarily. That article has been invoked only once: after the September 11, 2001, attacks on the United States, after which NATO-led troops went to Afghanistan.

In 2006, NATO members agreed to commit at least 2% of their gross domestic product (GDP, a measure of national production) to their own defense spending in order to make sure that NATO remained ready for combat. The economic crash of 2007–2008 meant a number of governments did not meet this commitment, and in 2014, allies pledged to do so. Although most still do not invest 2% of their GDP in their militaries, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and annexation of Crimea in 2014 motivated countries to speed up that investment.

On the day NATO went into effect, President Harry S. Truman said, “If there is anything inevitable in the future, it is the will of the people of the world for freedom and for peace.” In the years since 1949, his observation seems to have proven correct. NATO now has 31 member nations.

Crucially, NATO acts not only as a response to attack, but also as a deterrent, and its strength has always been backstopped by the military strength of the U.S., including its nuclear weapons. Trump has repeatedly attacked NATO and said he would take the U.S. out of it in a second term, alarming Congress enough that last year it put into the National Defense Authorization Act a measure prohibiting any president from leaving NATO without the approval of two thirds of the Senate or a congressional law.

But as Russia specialist Anne Applebaum noted in The Atlantic last month, even though Trump might have trouble actually tossing out a long-standing treaty that has safeguarded national security for 75 years, the realization that the U.S. is abandoning its commitment to collective defense would make the treaty itself worthless. Chancellor of Germany Olaf Scholtz called the attack on NATO’s mutual defense guarantee “irresponsible and dangerous,” and NATO Secretary-General Jens Stoltenberg said, “Any suggestion that allies will not defend each other undermines our security.”

Applebaum noted on social media that “Trump's rant…will persuade Russia to keep fighting in Ukraine and, in time, to attack a NATO country too.” She urged people not to “let [Florida senator Marco] Rubio, [South Carolina senator Lindsey] Graham or anyone try to downplay or alter the meaning of what Trump did: He invited Russia to invade NATO. It was not a joke and it will certainly not be understood that way in Moscow.”

She wrote last month that the loss of the U.S. as an ally would force European countries to “cozy up to Russia,” with its authoritarian system, while Senator Tim Kaine (D-VA) suggested that many Asian countries would turn to China as a matter of self-preservation. Countries already attacking democracy “would have a compelling new argument in favor of autocratic methods and tactics.” Trade agreements would wither, and the U.S. economy would falter and shrink.

Former governor of South Carolina and Republican presidential candidate Nikki Haley, whose husband is in the military and is currently deployed overseas, noted: “He just put every military member at risk and every one of our allies at risk just by saying something at a rally.” Conservative political commentator and former Bulwark editor in chief Charlie Sykes noted that Trump is “signaling weakness,… appeasement,… surrender…. One of the consistent things about Donald Trump has been his willingness to bow his knee to Vladimir Putin. To ask for favors from Vladimir Putin…. This comes amid his campaign to basically kneecap the aid to Ukraine right now. People ought to take this very, very seriously because it feels as if we are sleepwalking into a global catastrophe…. ”

President Joe Biden asked Congress to pass a supplemental national security bill back in October of last year to provide additional funding for Ukraine and Israel, as well as for the Indo-Pacific. MAGA Republicans insisted they would not pass such a measure unless it contained border security protections, but when Senate negotiators actually produced such protections earlier this month, Trump opposed the measure and Republicans promptly killed it.

There remains a bipartisan majority in favor of aid to Ukraine, and the Senate appears on the verge of passing a $95 billion funding package for Ukraine, Israel, and Taiwan. In part, this appears to be an attempt by Republican senators to demonstrate their independence from Trump, who has made his opposition to the measure clear and, according to Katherine Tulluy-McManus and Ursula Perano of Politico, spent the weekend telling senators not to pass it. South Carolina senator Lindsey Graham, previously a Ukraine supporter, tonight released a statement saying he will vote no on the measure.

Andrew Desiderio of Punchbowl News recorded how Senator Thom Tillis (R-NC) weighed in on the issue during debate today: “This is not a stalemate. This guy [Putin] is on life support… He will not survive if NATO gets stronger.” If the bill does not pass, Tillis said, “You will see the alliance that is supporting Ukraine crumble.” For his part, Tillis wanted no part of that future: “I am not going to be on that page in history.”

If the Senate passes the bill, it will go to the House, where MAGA Republicans who oppose Ukraine funding have so far managed to keep the measure from being taken up. Although it appears likely there is a majority in favor of the bill, House speaker Mike Johnson (R-LA) tonight preemptively rejected the measure, saying that it is nonstarter because it does not address border security.

Tonight, Trump signaled his complete takeover of the Republican Party. He released a statement confirming that, having pressured Ronna McDaniel to resign as head of the Republican National Committee, he is backing as co-chairs fervent loyalists Michael Whatley, who loudly supported Trump’s claims of fraud after the 2020 presidential election, and his own daughter-in-law Lara Trump, wife of Trump’s second son, Eric. Lara has never held a leadership position in the party. Trump also wants senior advisor to the Trump campaign Chris LaCivita to become the chief operating officer of the Republican National Committee.

This evening, Trump’s lawyers took the question of whether he is immune from prosecution for trying to overturn the 2020 presidential election to the Supreme Court. Trump has asked the court to stay last week’s ruling of the Washington, D.C., Circuit Court of Appeals that he is not immune. A stay would delay the case even further than the two months it already has been delayed by his litigation of the immunity issue. Trump’s approach has always been to stall the cases against him for as long as possible. If the justices deny his request, the case will go back to the trial court and Trump could stand trial.

LETTERS FROM AN AMERICAN

HEATHER COX RICHARDSON

#Bill Bramhall#political cartoon#shot dead on 5th avenue#NATO#Letters from An American#Heather Cox Richardson#MAGA craziness#national security#history#MAGA Republicans#war in Ukraine

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

This attack was undertaken at the direction of Bill Flanagan, President and Vice Chancellor of the University of Alberta.

Thus it is imperative that President Flanagan, the University of Alberta Board of Directors, and the campus community be reminded of the kihci-asotamâtowina, the sacred promises which bind all who live upon these lands to live according to the principles of miyo-wîcêhtowin (good relations), wîtaskêwin (peaceful living together on the land), and tâpwêwin (speaking with truth). This treaty relationship is the only moral or legal claim the university has to the lands it occupies, to the research it conducts, and to the access it has to Indigenous lands and resources.

This university, its president Bill Flanagan, and other members of administration, violated all of these principles, and failed to uphold their Treaty obligations when they unleashed state violence upon students, staff, and community members on May 11th.

âpihtawikosisân posted on May 14,2024. Statement of Treaty Principles: University of Alberta’s May 11th attack on students, staff, and community

To access the signable Google form please click here.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

This is just shameful. I’m glad that at least the MoJ is providing advice that this is a terrible, horrible, racist, destructive idea.

#Aotearoa#new zealand#te tiriti o waitangi#the treaty of waitangi#trying to legislate away our founding document as a nation#so they can pretend all that *history* is over and everyone’s equal now and Māori who aren’t rich and healthy need to stop complaining

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

opinion article by John Campbell about the National Hui for Unity.

(full text below the "read more" button in case of paywall)

OPINION: The national hui at Tūrangawaewae Marae saw 10,000 people united in the face of actions by the coalition government, including its proposed Treaty Principles Bill. John Campbell was there.

History happens on single days.

Yesterday, at Tūrangawaewae, will be one of them.

“Why are you here?”, I asked Tame Iti.

“Vibrations”, he replied.

The rest of us will feel them over the days and months and years ahead.

Initial estimates of how many people would come had begun at 3000. Then 4000 registered, so estimates grew to 5000. Then 7000. By lunchtime, organisers were saying 10,000 had arrived. There wasn't room inside for them all. A large marquee across the road was full, all day. Every seat, everywhere, was taken. There was hardly standing room.

This special place, which has held tangi for royalty, which is where the Tainui treaty settlement was signed, which was visited by Nelson Mandela, and Queen Elizabeth II, and many of our greatest rangatira, has seldom seen so many people.

But no one objected. To standing. To the steaming heat. To the fact that sometimes people were too far away from the speakers, or the screens relaying them, to hear.

New Zealand First’s deputy leader, Shane Jones, told RNZ the hui could turn into a “monumental moan session”.

But it didn’t. Somehow, the word I keep coming back to is joyful.

The National Hui for Unity it was called. And it felt like exactly that.

Iwi after iwi: the big 10

On the way to Ngāruawāhia early yesterday morning, I pulled into a truck-stop near Bombay, at the southernmost end of the Auckland motorway system, to meet the Ngāpuhi convoy travelling down from the far north.

Some had begun their journey way up, in Kaikohe, at 3am. They spilled out into the half light of an overcast morning and inhaled the beginning of what would be an extraordinary day.

It’s easy for the significance of this delegation to be lost amid all the other arrivals. The people who’d come from even further away. Iwi after iwi. Ngāpuhi, Ngāti Porou, Tainui, Ngāti Kahungunu, Ngāi Tahu, Te Arawa, Ngāti Tūwharetoa, Ngāi Tūhoe, Ngāti Maniapoto – the big ten, all there, in declaratory numbers.

Ngāi Tahu representatives had taken a huge journey by road, then Cook Strait ferry, then road.

A friend’s father flew up from Invercargill.

But the size and standing of Ngāpuhi’s delegation provides some insight into how very significant this hui was.

Ngāpuhi aren’t a Kīngitanga iwi. They don’t see Kīngi Tūheitia as their king. And they contain Waitangi within their broad, northern boundaries – home, of course, to the Waitangi commemorations, our most famous form of national hui.

And yet they came, hundreds of Ngāpuhi. Some wearing korowai made especially for the occasion. Some the direct descendants of Treaty signatories. A waiata, composed for the hui, rehearsed beyond newness into a heartfelt and singular voice.

“Why are you going?” I asked Mane Tahere, the chair of Te Runanga-Ā-Iwi-Ō-Ngāpuhi. “It feels significant that Ngāpuhi are attending in such numbers.”

“Because”, he answered, “the challenges we face do not discriminate amongst iwi. We held three hui to discuss whether we should come, and who would come, and what our message would be. The final hui was only last Saturday. I wouldn’t have put our rūnanga resources into something we didn’t collectively support. This was hapū rangatiratanga. Hapū after hapū spoke and said we should go.”

Why?

“Because the question we have to ask as Māori is how we activate ourselves, re-activate ourselves, for 2024? How do we say to the coalition government, ‘hang on, what do you mean, and what are you doing?’ And the best way to do that is to do it together. Now is the time for Māori unity.”

A powerful rejection

The National Hui for Unity was only called by Kīngi Tuheitia Pootatau Te Wherowhero VII (Kīngi Tuheitia) at the beginning of December. That so very many people would arrive here, only six weeks later, in the holiday-season slowness of the third week of January, speaks not only to how resoundingly those present reject the coalition government’s Treaty Principles Bill, but also to a strength of unity already existing.

That is to say, a unified rejection of what Kīngitanga Chief of Staff, Archdeacon Ngira Simmonds, described as the “unhelpful and divisive rhetoric” of the election campaign.

“Maaori can lead for all”, said Ngira Simmonds, at the beginning of this month, “and we are prepared to do that.” *

This is part of a growing sense, as Ngāpuhi’s Mane Tahere told me, that “we’ve turned a corner”.

The corner is that u word – unity. The increasingly urgent sense of the need for a collective response to the coalition government.

And, without great external fanfare, these relationships have already been building.

The Kīngitanga movement has begun sending some of its most senior figures north for Waitangi Day commemorations – into the heart of Ngāpuhi country. And again, like Ngāpuhi coming to Ngāruawāhia, this reflects a belief that by Māori for Māori, all Māori, is the strongest possible response to a government they fear is intent on division.

This year, for the first time since 2009, Kīngi Tūheitia himself (who has Ngāpuhi whakapapa on his father’s side) will be attending Waitangi.

Symbolic? Yes.

Significant? Yes.

Unity.

Mana motuhake (self-government).

“Look at all these people,” Tame Iti said to me. “They’re here to listen. To learn. The first layer of mana motuhake is yourself.”

All protest is a form of risk.

Risk that it goes awry – and costs support, rather than galvanises it.

Risk that it arms your most cynical critics with the material for derision or contempt.

Risk that no one notices. Or that the turnout is so small that those who have the luxury of being able to not protest can turn away.

Some politicians may tell you that 10,000 people is not very many. I would say otherwise. In 30 years of covering politics, I have never attended a New Zealand party-political rally that attracted anywhere near that many. Or even half that number.

What happened at Tūrangawaewae yesterday was a triumph for all those involved.

In the striking heart of the mid-afternoon, I passed Tukoroirangi Morgan, the chair of the Waikato-Tainui executive board. We were going in opposite directions over the sunburnt road.

“How’s it going, Tuku?”, I asked him.

“I’s amazing”, he replied. “All these people.” And then he stopped, looked out over the everyone, everywhere, and repeated himself. “Amazing.”

The challenge of history

Tūrangawaewae is located just outside Ngāruawāhia, directly across the Waikato River from the shops in that little township. Somewhere, just to its east, the new Waikato Expressway has stolen many of the estimated 17,000 cars a day that once passed through here. For decades, Ngāruawāhia was a pie and petrol stop on the main road between Hamilton and Auckland.

Not so much, any longer.

The challenge of history is to survive it.

And Kīngitanga itself was a kind of survival strategy.

It wasn’t this simple, of course, but a famous saying of the second Māori King, Tāwhiao, broadly speaks to the hopes of the Kīngitanga movement: “Ki te kotahi te kākaho ka whati ki te kāpuia e kore e whati.” The Māori Dictionary translates it prosaically: “If there is but one reed it will break, but if it is bunched together it will not.”

Yesterday, the reeds felt tight and strong.

“Why are you here?” I asked people, over and over.

The answer was almost always a variation of what Christina Te Namu told me. Christina, too, is Ngāpuhi. “I just wanted to support our people”, she said. “Now is the time for us to stand together as one.”

A group of women from Ngati Porou stopped to say kia ora.

It seems almost inadequate to state it like this, but they were there to be there. They had driven from Tairawhiti because being there mattered. Every person I spoke to had come to be part of this declaration of solidarity.

'An attempt to abolish the Treaty'

On Friday morning, something happened that gave this already significant day a vivid, extra weight.

My 1News colleague, Te Aniwa Hurihanganui, obtained details of the coalition Government’s Treaty Principles Bill. In its initial form it is not so much a re-evaluation of the role of the Treaty as an abandonment of it. Professor Margaret Mutu, speaking on 1News on Friday night, called it “an attempt to abolish the Treaty of Waitangi.”

This has arisen out of National’s coalition agreement with ACT.

I wrote about this at the end of last year, and also in the weeks after the election. I looked at the coalition agreements between National and ACT, and National and New Zealand First. And I noted their pointed focus on Māori. Some of it felt mean. What I called a strange, circling sense of a new colonialism.

I wrote about what I saw as ACT and New Zealand First's experiments with a kind of "resentment populism".

Who are we?, I asked. And where are we heading?

We’re heading to National reaching 41 percent in the first political poll of the year, “a massive jump”, as Thomas Coughlan described it in the NZ Herald, earlier this week. And we’re heading here, to Tūrangawaewae, and to thousands of people who travelled from throughout the country to collectively say, “no”.

In other words, we’re heading towards, or have already arrived in the vicinity of what PBS called the “divide and conquer populist agenda”.

And we’re heading to politics that purport to speak out against division, whilst arguably fomenting it.

In an opinion piece by David Seymour, published in the NZ Herald on Friday, the ACT leader begins with the sentence, “If there’s one undercurrent beneath so much of our politics, it’s division”.

Is David Seymour responding to division, or causing it?

The Treaty, he said, in December, “divides rather than unites people, as most treaties are supposed to do.”

But whose endgame is division? Really?

I've written before about the kind of populist politics that drive people to division, then throw up their hands and yell, “LOOK! DIVISION”, having wished for exactly that.

This, as Australian Academic Carol Johson wrote in The Conversation after the “no” vote in Australia’s Voice referendum, speaks to “a conception of equality controversially based on treating everyone the same, regardless of the different circumstances or particular disadvantages they face.”

That's equality as David Seymour consistently claims to define it.

But do as they say, not as they do. There was a time when ACT received some handy support from National. Remember that famous cup of tea? Surely Seymour's idea of equality would have insisted that Act get trounced than receive a leg-up?

The fascinating thing is that populism is typically structured around “the claim to speak for the underdog and the critique of privileged 'elites' and their disregard for the needs of ’ordinary people’".

But it’s hard for National to occupy that space when the party has historically been supported by the “elite”, and when your leader is a former CEO who owns seven properties, and who received total remuneration of $4.2 million in his last full year at Air New Zealand.

So, you can do two things. You can outsource populism to your coalition partners. (And sit there with a face of injured innocence, like someone insisting it was really the dog who farted.) And you can allow coalition partners to redefine the definition of “elite”.

No-one does this more enthusiastically than Winston Peters.

During the months prior to the election, the New Zealand First leader said “elite” more often than Kylie Minogue has said “lucky”.

“Elite Māori”, “elite power-hungry Māori”, “an elite cabal of social and ideological engineers.”

The idea, as I wrote after the election, is to somehow persuade us that Māori are getting something the rest of us are not. And they are: a seven-years-shorter life expectancy, lower household income, persistent inequities in health, the greatest likelihood of leaving school with low or no qualifications, and an over-representation in the criminal justice system to such a great extent that Māori make up 52 percent of the prison population.

Elite as.

A shameful history

So, had this hui erupted into a kind of rage, would that have been a victory for populism? Would the divisions have become entrenched? Would Māori have been blamed for reacting to provocation, rather than the provocation itself being examined?

None of this is new. Which is why Māori recognise it.

In July 1863, the Crown issued a proclamation demanding: “All persons of the native race living in the Manukau district and the Waikato frontier are hereby required immediately to take the oath of allegiance to Her Majesty the Queen”.

And those who wouldn’t?

“Natives refusing to do so are hereby warned forthwith to leave the district aforesaid, and retire to Waikato beyond Mangatawhiri.”

And anyone “not complying with this Order… will be ejected.”

Vincent O’Malley, in his remarkable book The Great War for New Zealand describes what happened next.

“On the same date some 1500 troops marched from Auckland for Drury.”

The troops didn’t stop. There are few more egregious and cynical predations in our history. South they went. Without just cause or provocation. Into Waikato.

Ngāruawāhia, Vincent O’Malley tells us, was “strategically important during the war because of its location at the confluence of the Waikato and Waipā rivers.”

“By 6 December 1863, Ngāruawāhia (‘the late head quarters of Māori sovereignty’ as one reporter dubbed it) had been deserted.”

At four o’clock that afternoon, a British flag was hoisted there.

And why does this story matter, still? 160 years later.

Because the Crown used the requirement for “allegiance”, the demand that Māori be loyal to it, so disingenuously. The language of colonisation purported to be about governance, about the role and rule of a single law, but it was a violation of law and a betrayal of the principles of government.

By the end of this rule of law, roughly 1.2 million acres of Waikato land had been “confiscated”.

And any opposition to it was defined, in law, as “rebellion”. And rebellion was justification for seizing more land.

This is our history. And part of it happened here, where the 10,000 people met yesterday.

Rising above the hatred

It was so hot by late morning that people were swimming in the Waikato River.

I wandered down from the crowds at the hui to talk to the people swimming. They were mostly young, although not all.

I met a ten year old who told me her parents had brought her so she could “find out where I’m from”.

She was from Waitara, in Taranaki, so this wasn’t a literal homecoming.

I wondered how many people had travelled big distances to have a new or reinvigorated sense of what it means to be Māori.

Heading back inside, I saw Professor Margaret Mutu.

There are few who have more rigorously applied their formidable intellect to making sense of the intersection of Māori and colonisation.

She is of Ngāti Kahu, Te Rarawa, Ngāti Whātua and Scottish descent. She is Professor of Māori Studies at the University of Auckland. And, her university profile tells us, she holds a BSc in mathematics, an MPhil in Māori Studies, a PhD in Māori Studies specialising in linguistics and a DipTchg.

There was nowhere quiet for us to sit. But people kindly made space at the back of a kitchen prep area. And I asked her about the significance of the Treaty, for Māori, for the Crown, and for us all.

“Te Tiriti is where you go," she said. “When things look as if they’re not working for you, you have a protection, and that’s where you go. It will always look after you. It will always protect you.”

“And while it seems clear that this government wants to abolish the Treaty," Margaret Mutu continued, “that can never happen. For one thing, you have two parties to a treaty, and one of them can’t unilaterally redefine it. But also, our tūpuna were very, very wise. In the Treaty they invited Pākehā, the British, to come and live with us. But they had to live with us in peace. In peace and friendship. And that’s what the Treaty is. It’s a treaty of peace and friendship. You can’t redefine that. You can’t rewrite that. It was very wise and it was very clear.”

And here’s where Margaret Mutu helped me understand why the mood at Tūrangawaewae was so – and I wish I could find better words – hopeful, positive, constructive.

Manaaki manuhiri: to support and care for your guests.

“We invited Pākehā to live amongst us,”, she said. “And what a lot of our Pākehā friends don’t understand, I think, is that our tikanga requires us to manaaki manuhiri. And that’s about looking after everybody. Everybody. So even when we have hate thrown at us, we have to assert aroha. That’s what manaaki manuhiri requires, even when people are very badly behaved.” Margaret Mutu laughs at this. “So, people have come here today to find that strength. It’s not about fighting people. It’s to find that strength and unity to be able to rise above the hatred. And now we will just get on and do exactly that.”

Meeting the King

After lunch, I was invited to meet the King.

I’ve never been inside Tūrongo before, the royal residence. Or Māhinaarangi, which is both a famous meeting house and a unique kind of museum.

It looks out over the marae. And it gently contains, as if nestled in the palm of a large, open hand, photos and remembrances of those who’ve come before. The people who built Kīngitanga. Tāwhiao is there, his photo looking down from the wall. He died 130 years ago. How he would have marvelled, with great pride, at such a gathering, and perhaps, also, despaired at it still being necessary, in 2024.

Ngira Simmonds took me in. And I found myself, shy for once, able to stand and look out, viewing the unfolding of this new history from a place that is so central to the story of the history of us.

Kīngi Tuheitia was beaming.

“I didn’t sleep last night”, he told me. “But I knew this was the time for us to come together. And we have. We have.”

It occurred to me, as I walked back to stand amongst the thousands Kīngi Tuheitia was looking out to, with such delight, that the hui was the actualisation of Tāwhiao’s hope for the unbreakable strength of reeds tied together.

What was was happening felt transformative in the very fact it was happening. The mana motuhake of 10,000 people.

The vibrations.

Will the government feel them?

Will they survive the divisions of populism? Of politics that echo our repeated capacity to claim we are governing to unite people whilst governing against Māori?

Or maybe, this is how it all begins. In an historically large display of unity.

Rātana follows. Then Waitangi.

Yesterday ended with Kiingi Tuheitia speaking.

“The best protest we can do right now is be Maaori. Be who we are, live our values, speak our reo, care for our mokopuna, our awa, our maunga, just be Maaori. Maaori all day, every day. We are here, we are strong.”

The reeds tightening.

*Macrons haven't been used when quoting Tainui, who choose not to use them.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Thomas Jefferson (1743 - 1826)

His portrait is on the $2.00 Dollar Bill.

Thomas Jefferson was a very remarkable man who started learning very early in life and never stopped.

At 5, began studying under his cousin's tutor.

At 9, studied Latin, Greek and French.

At 14, studied classical literature and additional languages.

At 16, entered the College of William and Mary

Also could write in Greek with one hand, while writing the same in Latin with the other.

At 19, studied Law for 5 years starting under George Wythe.

At 23, started his own law practice.

At 25, was elected to the Virginia House of Burgesses.

At 31, wrote the widely circulated "Summary View of the Rights of British America," and retired from his law practice.

At 32, was a delegate to the Second Continental Congress.

At 33, wrote the Declaration of Independence.

At 33, took three years to revise Virginia's legal code and wrote a Public Education bill and a statute for Religious Freedom.

At 36, was elected the second Governor of Virginia, succeeding Patrick Henry.

At 40, served in Congress for two years.

At 41, was the American minister to France and negotiated commercial treaties with European nations along with Ben Franklin and John Adams.

At 46, served as the first Secretary of State under George Washington.

At 53, served as Vice President and was elected President of the American Philosophical Society.

At 55, drafted the Kentucky Resolutions and became the active head of the Republican Party.

At 57, was elected the third president of the United States.

At 60, obtained the Louisiana Purchase, doubling the nation's size.

At 61, was elected to a second term as President.

At 65, retired to Monticello.

At 80, helped President Monroe shape the Monroe Doctrine.

At 81, almost single-handedly, created the University of Virginia and served as its' first

president.

At 83, died on the 50th Anniversary of the Signing of the Declaration of Independence, along with John Adams.

Thomas Jefferson knew because he himself studied, the previous failed attempts at government. He understood actual history, the nature of God, His laws and the nature of man. That happens to be way more than what most understand today.

Jefferson really knew his stuff..

A voice from the past to lead us in the future:

John F. Kennedy held a dinner in the White House for a group of the brightest minds in the nation at that time. He made this statement:

"This is perhaps the assembly of the most intelligence ever to gather at one time in the White House, with the exception of when Thomas Jefferson dined alone."

"When we get piled upon one another in large cities, as in Europe, we shall become as corrupt as Europe." -- Thomas Jefferson

"The democracy will cease to exist when you take away from those who are willing to work and give to those who would not." -- Thomas Jefferson

"It is incumbent on every generation to pay its'own debts as it goes. A principle which if acted on, would save one-half the wars of the world." -- Thomas Jefferson

"I predict future happiness for Americans if they can prevent the government from wasting the labors of the people, under the pretense of taking care of them." -- Thomas Jefferson

"My reading of history convinces me that most bad government results from too much government." -- Thomas Jefferson

"No free man shall ever be debarred the use of arms." -- Thomas Jefferson

"The strongest reason for the people to retain the right to keep and bear arms is, as a last resort, to protect themselves against tyranny in government." -- Thomas Jefferson

"The tree of liberty must be refreshed from time to time with the blood of patriots and tyrants." -- Thomas Jefferson

"To compel a man to subsidize with his taxes, the propagation of ideas which he disbelieves and abhors, is sinful and tyrannical." -- Thomas Jefferson

Something every American ought to know.

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

Germany joins NASA's Artemis accords as newest signatory

During a ceremony at the German Ambassador's Residence in Washington on Thursday, Germany became the 29th country to sign the Artemis Accords. NASA Administrator Bill Nelson participated in the signing ceremony for the agency, and Director General of the German Space Agency at DLR Dr. Walther Pelzer signed on behalf of Germany.

NASA Deputy Administrator Pam Melroy and the following also were in attendance:

Jennifer Littlejohn, acting assistant secretary, U.S. Department of State

Chirag Parikh, executive secretary of the U.S. National Space Council

Andreas Michaelis, German ambassador to the United States

Dr. Anna Christmann, federal German coordinator of German Aerospace Policy

"I'm thrilled to welcome Germany to the Artemis Accords family," said Nelson. "Germany has long been one of NASA's closest and most capable international partners, and their signing today demonstrates their leadership now and into the future—a future defined by limitless possibilities in space and the promise of goodwill here on Earth."

The Artemis Accords establish a practical set of principles to guide space exploration cooperation among nations, including those participating in NASA's Artemis program.

"Germany and the United States have been successful partners in space for a long time. For example, German companies in the space sector are already central contributing to the Artemis program. The German signing of the Artemis Accords gives a further boost to this joint endeavor to carry out programs for the exploration of space. Thus, the Artemis Accords offer a multitude of new opportunities for industry and scientific research in Germany—and ultimately also across Europe," said Pelzer.

NASA, in coordination with the U.S. Department of State, established the Artemis Accords in 2020 together with seven other original signatories.

The Artemis Accords reinforce and implement key obligations in the 1967 Outer Space Treaty. They also strengthen the commitment by the United States and signatory nations to the Registration Convention, the Rescue and Return Agreement, as well as best practices and norms of responsible behavior NASA and its partners have supported, including the public release of scientific data.

More countries are expected to sign the Artemis Accords in the months and years ahead, as NASA continues to work with its international partners to establish a safe, peaceful, and prosperous future in space. Working with both new and existing partners adds new energy and capabilities to ensure the entire world can benefit from our journey of exploration and discovery.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

In October 2021, the Russian State Duma passed legislation requiring all regional leaders to go by the official title “glava“ (“head”), with some minor exceptions. A year later, Tatarstan, the last of Russia’s republics to call its leader “president,” had still yet to bring its legislation into compliance with this federal law. In December 2022, after months of negotiations with Kremlin representatives, the region’s parliament finally voted to amend its constitution and jettison the last major symbol of its once-meaningful “special status.” Why was Moscow so intent on ensuring that Putin is Russia’s only president? Meduza’s Andrey Pertsev explores this question and whether the change might have unintended consequences.

We’re in the middle of a “special [military] operation.” You see how the global community wants to dismember Russia. While we’re discussing our own issue, here’s how people are going to perceive it: “Look — Tatarstan has rebelled. Things aren’t going well for Putin. Russia’s going to break into pieces.” We can’t let that happen.

This is how Tatarstan President Rustam Minnikhanov explained in a speech on December 23 why the region’s parliamentary deputies should vote to scrap the title of “president” for the republic’s next leader.

A little more than a year earlier, Russia’s State Duma voted to implement new naming conventions for the country’s chief regional administrators. Before the change, though most regional leaders were called “governors,” the law allowed them to use other titles, including “administration head,” “mayor,” and even “president.” But in October 2021, federal parliament decided that “head” should become the standard in official documents, and that Russia should only have one president. Lawmakers made minor exceptions for Moscow, which is led by a mayor, and St. Petersburg and Sevastopol, which are led by governors.

The rest of the country’s regions have been allowed to keep the title of “governor” only as an unofficial, “secondary” title. As another alternative, republics can use the word “head” translated into the local language. But federal law now reserves the word “president” for Russia’s commander-in-chief.

For Tatarstan, the presidential status of its leader has always been a matter of principle. After the collapse of the Soviet Union, the predominately Muslim republic held a referendum in which most residents voted in favor of becoming a “sovereign state.” As a result, it became a subject of international law, gained the ability to enter into agreements with other foreign states, and refused to sign Moscow’s Federation Treaty, which regulated the Kremlin’s relationships with other Russian regions. Instead, in 1994, the two governments signed a power-sharing treaty. It gave regional authorities broad authority to make their own decisions, including economic ones: for example, Tatarstan maintained the right to impose its own taxes and manage natural resources as it saw fit.

In the early 2000s, however, the republic’s autonomy started to decline. As its constitution was rewritten multiple times, the regional government saw its powers diminish, while the federal authorities’ reach expanded.

Eventually, the regional head’s “presidential” title was virtually the only remaining sign of the republic’s special status, and regional elites found themselves in a constant battle with the federal authorities to preserve it.

For years, they were successful. But in late December 2022, thirty-seven local deputies (out of the regional parliament’s 100), including every committee head and both vice speakers, introduced a bill that would amend the republic’s constitution to eliminate the regional leader’s presidential status.

The new bill would bring Tatarstan’s regional legislation in line with federal law and do away with the last major vestige of the independence the republic once enjoyed. Furthermore, it would remove from the constitution the language that codifies Tatarstan’s state sovereignty.

Despite the bill’s impressive group of sponsors, however, the regional parliament’s State Building and Legislation Committee recommended that their fellow deputies reject the amendments.

The following day, a new and slightly less drastic bill was introduced. This one didn’t require the republic to relinquish its nominal sovereignty, though it did abolish the region’s presidency, replacing the title with “rais,” an Arabic word meaning “leader.”

In a speech urging parliamentarians to approve the amendments, Minnikhanov acknowledged that Tatarstan had long managed to resist the federal authorities’ pressure: “Unfortunately, probably, neither my efforts nor our deputies’ efforts were enough. We were unable to defend it as our right, of course, to name [the position], but we do have the chance to make an additional title.”

The president’s predecessor, Mintimer Shaimiev, also supported the changes: “Tatarstan will not become weaker!” The bill ultimately won support from a majority of regional deputies, even though Tatarstan’s State Council voted in October 2021 against the federal bill outlawing regional presidencies, becoming the only regional parliament to oppose the Kremlin’s initiative.

Two sources close to the Putin administration told Meduza that Kremlin officials viewed the regional parliament’s dissent “negatively” but always believed they would ultimately change enough deputies’ minds. “Communications and consultations went on for practically the entire year, and there was never a chance it was going to end any other way. Especially in these [wartime] conditions,” said one source. He also noted that deputies in Tatarstan were “allowed to speak out freely” and even express opposition through State Council committees: “It was clear that the legislation would go through anyway.”

The version of the bill that finally passed officially does eliminate Tatarstan’s presidency but not until 2025 — after the next election. Multiple sources close to the Kremlin told Meduza that Tatarstan could still lose its “sovereign” status in the next few years: “There definitely can’t be a state within a state in Russia right now.”

Historian Damir Iskhakov, one of the leading thinkers behind the Tatar National Movement, stressed to Meduza that “people in Tatarstan are reacting negatively” to the loss of their leader’s presidential status. “Officials in Moscow might think that people [in Tatarstan] don’t care, and that they don’t understand anything. On the contrary, they understand everything. They understand that this could be the start of the republic’s unraveling,” he said, adding that local elites are also “far from the people,” and that they don’t understand what it means to have independence from the country’s federal center, even if that independence is only symbolic.

Iskhakov noted that Tatarstan’s lawmakers also considered doing away with the requirement that the republic’s leader knows the Tatar language. “[That would be] much worse than the renaming of the republic’s leader. People can see that there’s a clampdown [from the federal center], but they don’t understand why,” he said.

On the other hand, political scientist and former regional deputy Vladimir Belyayev believes that most Tatarstan residents are “indifferent” to the changes: “People are worried about something else: social problems.” In his view, what residents of the republic need isn’t a “presidency” but “decent federalism” — for example, more equitable tax distribution between Moscow and Kazan.