#to be clear this is christian conservative media reviewer's god

Text

I’m just over here writing and god’s watching me through binoculars like a cartoon villain with steam coming out of his ears, saying, ‘someone has to stop them!!!!!’

#to be clear this is christian conservative media reviewer's god#big goal in life is to write something that gets a scathing review in world magazine#about writing#about me#txt#narn#also I dyed my hair hot pink again#and it's making me want to fall into middle-earth again#for the uproar that would cause in the shire

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Is it Okay for a Christian to Watch Yaoi and Yuri Anime?

Why do you post about yaoi on a Christian blog?

We receive this question from time to time across our various platforms when we post, say, fan art from Given on Tumblr or a first impression piece on a yuri series here on the website. And it is a good question, one I want to more fully address here today instead of piecemeal when we receive it, and in advance of my review of Sweet Blue Flowers (Aoi Hana) later this week.

Much of the Christian culture in the west has an aversion to all things homosexual. While the phrase “love the sinner, hate the sin” has gripped an entire generation of mostly evangelicals, the functional form of doing life with this in mind isn’t as easy as speaking it. Loving someone is a complex, dynamic action, and when someone’s entire identity is something your faith deems as sin, it’s all the more challenging.

I wonder also if, as it often does, the culture adds a layer to the issue that hinders us from expressing a godly love to the LGBT community—not “wordly” culture, but the church’s. Homosexuality is treated as a “special sin” in church, perhaps representative of both a complete rejection of Christian values and conservative American values. It’s uncomfortable and dangerous territory for many. And yet, we’re here to make disciples of people across the entire spectrum of humankind, and with otaku Christian reading this, and you connected to probably dozens of otaku who identify as LGBTQ, you’re in a unique space to love these folks, though you may struggle with it.

But you know what we struggle with less—and again, likely because of the acceptance within our culture? Hyper violence and fanservice. The latter, especially in ecchi series, may make us uncomfortable, and we might not watch anime featuring a ton of fanservice with others, but we’ll still often tune in. And violence? Well, we may watch a series with gore with even family members. Perhaps most telling, though, is that we’ll watch an entire series in which the worldview being presented, and sometimes promoted, is Shinto or otherwise one that would never fit within the Christian framework. Sometimes these series affirm those religions, thus negating a belief in the Christian God. We’ve become okay with Weathering with You, but not with Wandering Son.

We need to strip away the trappings of culture and look at how actions, lifestyles, and beliefs are presented in anime through a biblical lens. So Let’s ask the question in that framework: Can we or should we be watching yaoi and yuri? The answer, as is usual, isn’t clear-cut, though I do believe it’s clear that we should at least entertain the thought. I’ve heard theologians, and one in particular whom I respect terribly, state that we as Christians probably shouldn’t watch any media. I understand his perspective, and in truth, if we were perfect, we would be able to find this immense satisfaction and enjoyment in God alone that wouldn’t find in even the latest episode of Dr. Stone or The Promised Neverland. But stuck here on earth, we’re going to stream video. We’re going to watch anime. And more than that, being part of the culture allows us to understand people in a way that we wouldn’t if we lived apart from it. This is, after all, what we do here on Beneath the Tangles—our passion for anime and love for people collide as we chat about both anime and faith. I imagine Paul was much the same. Such a learned man, he must have doubly enjoyed studying the Greek philosophers—both as a way to exercise his mind and as a path into the hearts of the Greeks.

But as I’ve mentioned in the past, each person must decide for themselves where the line is, at what point he or she should stop watching a certain series. And as we mature in our faith and in all other ways, that line may shift and it may become zig-zagged and complicated itself. Returning to yaoi, we might find that series like Given expresses fundamental truths about love and care within a framework that isn’t scriptural, and that it could help us draw nearer to God. On the other hand, some show relatively devoid of violence, fanservice, or other aspects we might consider sinful has an incredibly desolate and nihilistic worldview that leads us to a dark place, away from the love of Christ. Which should we leave behind, and which should we embrace?

And so, as you continue your otaku journey, I hope you won’t exclude yaoi and yuri just because it’s yaoi and yuri. Think about all your media choices, how you approach anime and what impact it has on you. And if that one yaoi show leads you to sin, cut it off! And if that yuri show leads you ponder on the sacrificial nature of love, go give it a try! And the same for all anime—shounen, seinen, slice-of-life, coming-of-age, sci-fi, mecha, and on down the line.

As for us as a ministry? It is a little more complicated. We have to consider also that we’re a model, that what we do can be taken as “acceptance” or even reveling in sin. And we are certainly prone to error, as well. However, I want to assure our readers that we do think about these things as we develop and post content. For instance, after considerable discussion, we decided not to discuss a certain series currently airing because we did not find it likely to be spiritually uplifting in any manner, and very likely, instead, to lead our audience to sin.

Ultimately, though, we put much trust in you to develop godly viewing habits as you watch anime. And likewise, we do our best not to “promote” sin. That’s a blurry line itself, for is posting an image for said series promoting it? It could be. But returning to Weathering with You, about which we recorded a podcast episode and also developed much additional content, were we promoting a Shintoist approach to the world? I would say not, and I would think that you’d agree if you saw our posts. We were instead celebrating the goodness in the series, things reflective of God’s character—creativity, wonder, sacrifice, music, and love.

And if you can find the same in yaoi or yuri, even a glimmer of God, maybe you should be watching. I know we will be.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

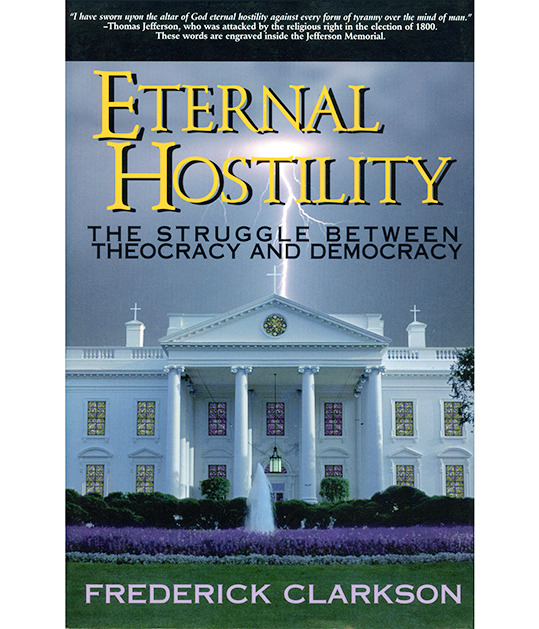

CAUSA and the Catholic Church in the 1980s

“Moon’s Law: God Is Phasing Out Democracy”

By Fred Clarkson

extract:

While best known for its growing relationship with Protestant fundamentalism, the Moon organization has actively sought close links with the Catholic Church, particularly in Latin America.60 Their success has been decidedly mixed. The Bishops of Honduras, El Salvador, Panama, and Japan have all denounced the Unification Church in pastoral letters. While this has put a crimp in their operations, Moonism is not without allies. The Archbishop of La Plata, Argentina, sponsored the first CAUSA seminar in that country, and later awarded an honorary doctorate to Moon from the Catholic University, while he was in jail.

According to an internal strategy document dated January 1985, CAUSA views its relationship with the Catholic Church as “extremely important…. One [pastoral] letter of the Bishops in any country will considerably damage our activities. If it happens in a Third World country, all the faithful Catholics will go away, leaving us with ‘non-faithful’ ones, making our situation even more miserable.”61

▲ Pope John Paul II with Moonies Tom Ward (circled) and Bo Hi Pak (standing behind the Pope) at the 2nd AULA conference – Rome, December 1985.

Indeed, the Honduran Bishops denounced CAUSA as “anti-Christian” and declared that the Unification Church “creates a species of material and spiritual slavery” that poses “serious dangers to the psychological, religious, and civic integrity of anyone who yields to its influence.”62 The Japanese Bishops, noting major theological differences with the Unification Church, also “discourage all Catholics from any collaboration with it. While the Holy See is contrary to any participation by the faithful, it is even more opposed to whatsoever [sic] attendance and collaboration on the part of Catholic priests.”63

The principal Moon advocate within the Church appears to be Father Sebastian Matczak, a Polish priest who has spoken frequently at CAUSA conferences, and who teaches philosophy at the Unification Seminary in Barrytown, New York. The CAUSA paper notes that “Dr. Matczak, in his latest visit to Rome the past January [1984] could verify that the bad reputation of our movement is mainly coming from Latin America, while there they say that official documents from the Vatican prevent them from any relation with us.”64

Despite serious obstacles to Moonist advances on the Catholic Church, the organization claims that CAUSA has a “strong connecting point” with the Church in most Latin countries. The internal report notes, however, that the strategy of seeking relationships with the hierarchy, and inviting priests to CAUSA conferences, has generally failed. As a result, “it seems that we have to open two fronts, one in Rome, one in Latin America.” The latter option emphasized secret and highly selective CAUSA conferences with priests as a way to build a core of supporters, whose favorable reports would percolate up to the Vatican. Dr. Matczak reportedly “finds this strategy...the only way and an absolute necessity.” The twin goals of this plan were to “STOP THE NEGATIVITY FROM WITHIN” (the Catholic Church) and to “Declare war to the Liberation theology.”65

It is possible that the Rome option is still viable. A new Moon unit called AULA (Association for the Unification of Latin America) was formed in Rome in December 1984.66 AULA’s second annual conference, in December 1985 in Rome, was attended by a dozen former presidents of Latin American countries and was received by the Pope. The Moon organization is skilled at using the prestige of out-of-power politicians. Two weeks later three former presidents of Colombia, and two of Costa Rica represented AULA at Moon’s welcome home rally in Seoul, South Korea.67

______________________________________

Notes

60. Louis Wolf, “Accuracy in Media Rewrites the News and History,”

in CAIB, Number 21 (Spring 1984), n. 57. LINK to PDF

61. Internal CAUSA document. January 1985.

62. Interchange Report, Fall 1984.

63. Arlington [Virginia] Catholic Herald, August 8, 1985.

64. Internal CAUSA document, January 1985. The Report is a confidential 3-year review of CAUSA/Catholic relations. Written by Roger Johnstone and Liliana Karlson, and submitted to CAUSA’s Bo Hi Pak, Tom Ward, and Antonio Betancourt, the Report makes clear that their intentions are more than ecumenical in spirit: “The goal is: the CATHOLIC WORLD (80% of all Christianity). The time is: NOW! Tomorrow might be too late!”

65. Ibid.

66. AULA is headed by Jose Maria Chaves, a longtime Moon operative. A native of Colombia, Chaves is now based in New York. He is a director of the Committee to Defend the U.S. Constitution, a Moon front group which placed full page ads in major American newspapers claiming Moon was a “Victim of a Government Conspiracy.” Warren Richardson, the first director of CAUSA North America and former general counsel to the Liberty Lobby was a director at one time as was David Finzer of the Conservative Action Foundation. In 1985, Finzer took over the youth arm of WACL, and in 1986 was elevated to the executive board. See “Christian Voice,” in this issue [of CovertAction].

67. Times [London], December 17, 1985.

“Japanese Warned about Moon's Unification Church” National Catholic Register 61, July 28, 1985

LINK to PDF: CovertAction No 27, Spring 1987

___________________________________________

“Moon’s Law: God Is Phasing Out Democracy”

Missing Pieces of the Story of Sun Myung Moon by Frederick Clarkson

NPR: Church and State: ‘Eternal Hostility’ with Frederick Clarkson

Money and Power and Moon’s Washington Times by Rory O’Connor

Sun Myung Moon was found guilty of US tax fraud and sent to Danbury prison in 1984

Pope Francis meets Moonies at the Vatican – he was asked to support the UPF in Seoul 2020

In Bolivia, Moon disciple Tom Ward and the former Hitler SS Officer, Klaus Barbie were often seen together

The CAUSA Kingdom

“Through CAUSA… people will eventually be drawn to the root, which is Rev. Moon.”

CAUSA and Three South American Terror Generals

#CAUSA#Roman Catholic Church#Sun Myung Moon#Unification Church#Family Federation for World Peace and Unification#Tom Ward

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Book Review: 1 Corinthians For You, by Andrew Wilson

Does God’s grace really change people? What does it do for the church community? In 1 Corinthians For You, Andrew Wilson studies Paul’s letter and thrills you with how God’s grace changes lives.

Pride and Division

Pride and division were taking over, devastating the Corinthian church. Wilson shares how the same might be said about evangelicalism today. For instance, we seem to be a culture absorbed with church growth and elevating human leaders. Wilson encourages us by saying that we must seek the Spirit as He guides us to humility and unity.

This book, while similar to a commentary, reads more like a devotional. Wilson is sharp and clear, with pastoral insight to share. He compares the Corinthians with the way we sin today, looking at incest, sexual immortality and drunkeness, greed and slander. We must not tolerate unrepentant sin. We must challenge it. Christ crucified might not shape our culture today, but it shapes our church communities.

Sex and Singleness

Paul spoke about sex, and Wilson explains how sex connects to the doctrine of the church. Ultimately, sex is about the gospel. Sex is a signpost. “It is but a glimpse of a relationship, a union and a happiness that are grander and deeper than our wildest imagining."

I was reminded that remaining unmarried can be good, right, and beautiful. Do we idolize marriage in our churches? I also saw how self-discipline, self-denial, and laying down our rights for the love of others and are important as we press on to win the prize.

Conservatives and Charismatics

Wilson sees “a message of wisdom” and “a message of knowledge” in 1 Corinthians 12 to mean a God-given ability to read a situation and speak wisely into it. In regards to Ch. 13, he understands Paul to mean that “completeness” comes when Jesus comes – when we see him face to face.

“Conservatives need to hear that prophecy should be pursued and that languages should not be forbidden. Charismatics need to hear that everything should be done in a fitting and orderly way, with a focus on comprehensibility, edification, and the lordship of Christ.”

Love Never Fails

Paul urges us to pursue prophecy, and Wilson describes it as being directed towards people, as it strengthens, encourages, and comforts us. He elaborates that Paul sees the Corinthians as speaking a language (as opposed to a sequence of nonsensical noises). He concludes that love trumps our right to express ourselves.

Interestingly, Paul concludes with a mention of Christ’s resurrection, and Wilson sees it as a fitting way to end a letter talking about unity and grace. This book helped me better understand 1 Corinthians, and I see how the message of pursuing purity and peace in Christ is essential. Love never fails.

I received a media copy of 1 Corinthians For You and this is my honest review. Find more of my book reviews and follow Dive In, Dig Deep on Instagram - my account dedicated to Bibles and books to see the beauty of the Bible and the role of reading in the Christian life. To read all of my book reviews and to receive all of the free eBooks I find on the web, subscribe to my free newsletter.

0 notes

Text

OBSERVATIONS ON RECENT CURRENT EVENTS

I haven't been following too much news since the Capitol Building riots last week, as I've been disgusted with what politics has become in present-day America (and I'm sure I'm not the only one who feels that way). These truly are strange times we're living in.

However, at the end of the day yesterday I did hear that the House of Representatives voted to impeach President Trump, and I also finally had time to read most of Trump's "Save America" speech from that January 6th rally, as I wasn't there to hear it in person that day. (Despite what some of you may think, I'm not an exclusively politically-minded person, and I'm really not into attending political rallies.) As I've touched on before, there are considerable aspects of Trump's behavior that I, and others, find just slightly repulsive. He can be coarse, rude, arrogant, & demeaning. And you'll find some of those same aspects of his persona in that speech he gave that day. It also wasn't helpful that at this late stage of the game he was still claiming he won the election by a landslide. And when he placed so much public pressure on Vice President Pence, urging him to overturn the certification of the election results & send it back to the states - that was very uncool. Yet with all this being said, as I read the speech, I didn't see blatant calls of insurrection from Trump in that speech that many in the media claim existed. At one point he said to the crowd, "I know that everyone here will soon be marching over to the Capitol Building to peacefully and patriotically make your voices heard". Yes, Trump used the 3rd person once in a way that could be very easily misconstrued, and he used various figures of speech, such as fight, strength, & weakness, that in retrospect were highly ill-advised. He also referred to Congressional Republicans who were questioning election certification results as "warriors" and he referred to them as "fighting" & then studying, working hard to verify the issues at hand. He claimed that those Republicans in the house who wouldn't "fight" for this cause would be primaried in their forthcoming elections. Again, while this use of figurative language is really not a good idea, especially when there are fringe elements of the political party in the crowd, I didn't find explicit calls for violence against anyone in the parts of the speech that I read.

A brief interlude: I realize that many will read this and consider me an apologist for Trump. Whatever. I know some people will hate me & suspect me of wrongdoing irregardless of what I write or don't write, of what I do or don't do. I'm not excusing Trump's behavior. I still believe he should have moved to publicly calm things down so much earlier than he did. And I was still so disappointed in his behavior in the days leading up to January 6th. Also, rioters & anarchists should be held legally accountable for their crimes. But I'm just writing today to express my observations on what has taken place since the anarchy at the Capitol.

I heard that some Democrats want to conclude the impeachment process of Trump in the Senate well after Trump has already officially left office. While I'm not a constitutional scholar & I can't comment on the legality of that, I do think it would open up an unwelcome can of worms, in terms of impeaching officials who have already left office. I'm sure there are people who would like to impeach former President Bush in this manner for invading Iraq way back when even though there were no weapons of mass destruction to be found there. I gather others would like to impeach former Secretary of State Hillary Clinton for failing to provide security for our ambassador & personnel in Benghazi, or others who would move to impeach former President Obama for weaponizing the branches of federal government against his political enemies or for giving an untold fortune in funds to Iran, one of the world's foremost sponsors of terrorism. So perhaps our elected officials should seriously consider the steps they plan to take in this regard, as others may seek to imitate your actions in the future.

Since the rioting that occurred at the Capitol Building, many on the left have attempted to portray Republicans as criminals with "guilt by association" type of accusations. Businesses, social media networks, and elected representatives have all joined in to engage in "canceling" or censoring conservatives. While I'll again repeat myself that I denounce the violence that occurred on January 6th (as I've denounced previous violence from both the right & the left), these blacklisting & censorship efforts are the beginning of the rise of fascism here in America from the left that I warned about in months past. Some are recommending that media now be scrutinied for "misinformation" (and make no mistake about it, that type of scrutiny will only be applied to conservative news outlets). Some have proposed the idea of "deprogramming" Trump supporters or sending them to "re-education" camps, I suppose so they can be taught (or forced) to think & believe the "correct" way, according to the left. When many of America's businesses, media establishment, & elected officials embrace socialism & China's communist methods, it shouldn't be surprising when they attempt to recast our country according to those methods.

It's strange. There were none of these types of recommendations when anarchists were looting & destroying businesses, attacking federal courts & federal buildings, and tearing down state property such as statues in 2020. Instead, certain legislators lauded these people & some even stood side by side with them. Many local police departments stood back and let the mayhem continue. City councils & mayors waxed poetic about the so-called "justice" of their cause. And celebrities bailed out several of the criminals who had been imprisoned for their part in that. You don't see this occurring now, however. There truly is not equal justice in America.

When the Christmas bombing occurred in Nashville just a few weeks ago, I had truly intended to comment on that when the holidays & New Year had passed. However political & current events changed, so I put it off. But now I'm still wondering about the FBI's ability to protect the American population. In the Nashville case, the FBI had been warned that the man who committed the crime was in the process of making bombs and yet it seems there wasn't sufficient follow-thru on the FBI's part in order to prevent the detonation. (Yes, the Nashville police were also warned of the suspect's activities, but I'm not familiar with their track record on such incidences. And bravo to the police there who gave warning to citizens when the bomb was about to go off.) And in this case of the Capitol Building anarchy, it appears an FBI office saw a threat of violence on a message board, and yet again, direct warning was not provided to the appropriate corresponding authorities in order to fortify the Capitol Building on January 6th. And lives were lost as a result. I know there are lives that have been saved & crimes that have been averted by the FBI in the past, but I'm extremely concerned that the opposite is becoming a recurring issue with this agency. I'm also concerned that one of the incoming Congress' first acts was to recently pass a bill on gender pronouns, of all things. Perhaps the first act of any incoming Congress in a post 9/11 world is to make a thorough review of security procedures & systems in the Capitol Building. For some time now I've been warning about my concerns regarding those who are in charge of local & national security, and I hope my concerns don't continue to be confirmed. Please focus on the right things & make the necessary changes in your agencies in order to be able to respond immediately and effectively to any potential & legitimate threats.

There are reports of threats of violence in all 50 state capitals for the upcoming inauguration of Biden, and while I've already stated that I don't believe my core audience here consists of fringe elements from the left or the right, I'll state this again: Do not use violence to express your beliefs, political or otherwise. Let there be a peaceful transition of power in the upcoming days and weeks.

Truly, America is no longer a Christian nation. Yes, there are many Christians in this country, but it's clear that as a nation we no longer espouse values of faith, self-control, and love for our neighbors. Our "look-to-God-as-a-last-resort" response to the coronavirus is a classic example of this. Our violent political & rioting behavior in the past year also shows we don't really trust God with our lives & problems anymore. Maybe that's why God pre-ordained the rare celestial sign that occurred in late December 2020, that merging of the planets that takes place only every several hundred years. Maybe God was trying to get our attention in the midst of all our self-absorbed behovior. Or maybe God is about to do all sorts of wonders in our time, wonders unseen in generations. I don't know. I just pray that we find God and turn to Him before we destroy ourselves from within.

0 notes

Text

Christian Films and Misc Rambling Thoughts on the Subject that Might or Might Not be Actually Connected

@cogentranting At some point, years from now, when all else is turned to dust and the sun has set for the last time, a post for this reply, stating I will reply in a longer fashion later (which would actually be now) shall appear. I will likely delete it out of pure spite. Stupid mobile app uploads.

I haven’t seen God’s Not Dead. Or God’s Not Dead 2. I should. Not because I just want to, or because It Is The Inspired Word Of Our Lord™ (hahahah it’s not guys, ok), but because of my overall interest an involvement in the world of film. I should be informed.

Also, I appreciate the sarcasm. XD I hope that was sarcasm or now I look really stupid but you’re going to get an earful either way, so it works out.

So let’s get to it:

I hate the Christian Film Industry™

Whew. There. I said it. Pray for my salvation.

Why? So, soooo many reasons.

1. The Sacrifice of Art in the Name of ‘Message.’

I, for one, want to know why the Christian church is constantly smashing down on the creative outputs of their members for not being enough about God, or published by Thomas Nelson, or advocated by Willie Roberts. Why. We would rather squelch the heartfelt, beautiful, God-given art produced by our brothers and sisters for not showing a clear Conversion Experience rather than be amazed at the ability God has allowed us to have to make such fantastic, whimsical, thought-provoking, emotionally-resonant things.

This is point number one because it. is. my. biggest. issue.

“Message films are rarely exciting. So by their very nature, most Christian films aren’t going to be very good because they have to fall within certain message-based parameters. And because the Christian audience is so glad to get a “safe, redeeming, faith-based message,” even at the expense of great art, they don’t demand higher artistic standards.” ~ Dallas Jenkins, movie reviewer and director of The Resurrection of Gavin Stone??? (Imma have to check back with you later on this, but the quote still stands on its own.)

“We have the makings of a movement that can change this culture. I honestly believe this. But I also believe the first step toward establishing the groundwork for a vibrant, relevant cultural movement based on scriptural thought is to stop producing “Christian films” or “Christian music” or “Christian art” and simply have Christ-followers who create great Art.” ~ Scott Nehring, in his book You Are What You See: Watching Movies Through a Christian Lens.

“If we are trying to evangelize, the fact that most Christian-themed movies are torn to shreds by non-Christian critics becomes an issue. If, however, we just really want to see our fantasies validated on screen, then we will write-off these poor reviews as “persecution.”” ~ Andrew Barber, in his article “The Problem with Christian Films.”

On a similar note, I want to know what the Mormon church is doing that the Christian church is not. Every time I turn around, I discover that another of my favorite artists, whether it be in film or elsewhere, is a professing Mormon:

musicians Imagine Dragons, the Killers, and Lindsey Stirling

authors Brandon Sanderson, Shannon Hale, Heather Dixon, and Brandon Mull

animator Don Bluth

actress Amy Adams and actor Will Swenson (both formerly)

etc, the list goes on

Hi, my Mormon friends. What is your secret. What ways of encouraging art and artists do you employ that my Baptist upbringing, and the Conservative Christian community in general, is so sorely lacking in?

2. The Christian Culture’s Subsequent Villainization of Hollywood.

This past Christmas, my sister gifted me a book titled Behind the Screen, “Hollywood Insiders on Faith, Film, and Culture.”

I sat down after all the gift-giving was done and read the first three sections before the holiday meal was served. But let me quote from the introduction which had me “Amen!”-ing and punching my fist to the sky every third word:

“We obsess about “the culture” endlessly; we analyze and criticize. But we can’t figure out anything to do but point an accusatory finger at Hollywood... Blaming Hollywood for our cultural woes has become a habit... Casting Hollywood as the enemy has only pushed Hollywood farther away. And the farther Hollywood is from us, the less influence we have on our culture. We’ve left the business of defining human experience via the mass media to people with a secular worldview.... In pushing away secular Hollywood, haven’t we turned our backs on the very people Christ called us to minister to - the searching and the desperate, those without the gospel’s saving grace and truth?”

Btw, if this subject is something you are interested in, I highly recommend this book. Written by creatives and executives in the film world (including one of the writers from Buffy the Vampire Slayer, the producer of Home Improvement, and even the multi-credited Ralph Winters, among others), it’s a frank, beautiful, and challenging read for artists, Christians, and film buffs.

The point here is that the church culture says if it doesn’t come from Sherwood, or have Kirk Cameron or Ducky Dynasty in it, or have a conversion sequence, it isn’t Christian and therefore Christians should not view or encourage it in any way. This. Is. Crap. Pardon my French.

Beauty can come from imperfection. Even unregenerate hearts still bear the image of the Divine and are capable of producing so much worthwhile and significant art. Which leads to...

3. Guess What? Secular Film Companies Make Quality Faith Films Too??!

Idk what I should even say here, but I’m just going to go with the one shining example I always think of: Dreamworks’ Prince of Egypt. It is purely a work of art from any standard, and that is the epitome of what Christians should be looking for in their endeavors to create good film. PoE is gorgeously animated, seamlessly directed, well-scripted, morally driven, more Biblically and historically accurate than you would believe (and where it falls down on direct representation, it remains true to theme and character), etc. etc. etc.

I could go on for ages about how much I adore this film. (Joseph, King of Dreams, is also noteworthy, but nearly up to par with the craftsmanship of its predecessor.

I mean

just look at

the art

4. I Do Like Some Films Made By ‘Christian’ Companies

Idk, I might step on people’s toes or surprise you by which of these I actually approve of, but here we go:

I like Fireproof. I have many issues with it, but overall it is a fairly well-made, Hallmark-style emotional flick. The acting leaves much to be desired, but it’s a decent bit of showmanship, story, and truth.

I do not like Facing the Giants. Give me Blind Side any day of the week, except don’t because... sports.

However, both Courageous (some actual real life dialogue and not a completely happily ever after, whaaaat???! Oh, but token conversion experience, of course), and the early-and-forgotten Flywheel (which, although low in camera quality and acting, is actually an enjoyable story), come in as films I would sit down and watch at least a second time.

Risen is well-made and acted and has some establishment of genuine Craft. However, as far as story plots go, a lot was sacrificed. The mountain-top encounter with Christ was, while perhaps the most generally cliche piece of story, to me the most heartfelt and provocative. After that...the film kind of ended in mediocrity. Like...what did the characters do after the credits rolled.

I actually really enjoy Mom’s Night Out. The manic theme almost kills me, but the quiet and the reveal at the end is worth sitting through to see.

And I appreciate Luther. I don’t watch it often, because I personally can’t stomach the more violent aspects (the reason I haven’t/don’t watch The Passion or End of the Spear.) But Luther is a great biographical film, and I would encourage anyone studying Catholic and/or Protestant history, especially Martin Luther, to watch it. This is a Film in both art, message, and class.

Tbh, I’ve been avoiding most of the other Christian films, which is why I won’t talk about them there.

5. You Don’t Have To Slap A Jesus Fish Bumper Sticker On It To Be Christ-Honoring

Walden Media is a prime example, I believe, of what Christians in the film industry should be doing. I mean, they’re not perfect at all, but they are not sacrificing art for message - or vice versa for that matter. While not strictly a Christian Film group, Walden is founded and run by a majority of Christian Conservatives who are actively seeking to make quality and wholesome films for people of all diversities. They’ve had a few flops and several more that just didn’t quite live up to their potential, but they also brought us

The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe, as well as

Mr. Magorium’s Wonder Emporium, and the one I will never stop talking about:

Amazing Grace.

Well-crafted films, put out by *gasp* an assortment of believers and non-believers. Art. Good films. Not Messages dressed up in makeup with a classy Instagram filter and a 30-day challange booklet to get your revival outfit on.

In looking through this stuff, I just found this article, which is a superb read and really gets at the heart of what I feel, and am very badly trying to communicate:

Why Faith-Based Films Hurt Religion

So.

When Christian Films start being an actual representation of creative community and the artistic talents God has given to us as personal and spiritual gifts, rather than a cheap way to try to force morality on Hollywood and on our neighbors without ever leaving the confines of our Bible Boxes in case we might get soiled, I may start appreciating the Christian Film Industry™. Until then??? I’ll stand behind my fellow creatives and my fellow believers and hope and work for the best.

Lastly, two things:

Christians Can Enjoy Secular Film Productions.

I would even argue that they should. We were created by a Creator God, who takes pride and joy in making beautiful things, in making each of us. And we are made in His image. We are creators as well, we make art all the time. Scripture tells us to worship God in everything we do. The movement of making “Christian Films for Christian Audiences because of Christian Reasons” is missing the point entirely. We as creatives are not here to make God Art, we are here to make art that glorifies God

Christ Does Not Need Hollywood. However, Hollywood Does Need Christ.

“While many missionaries travel to remote villages in Africa or South America to spread Christianity, [Karen] Covell believes her calling—her mission field, if you will—is right here in Los Angeles, in an industry that many of her fellow Christians find immoral or even downright sinful, both for its on-screen depictions of sex and drugs and the real-life sex, drugs, and other temptations that exist behind the scenes. Covell, who was a film producer in the early 1980s, says "the church did not get how I could justify being a Christian in Hollywood, and Hollywood did not get how I would follow God. It was a divide." It was nearly impossible to meet other Christians working in the industry, let alone ones who would express their faith openly. "I said, 'The church hates Hollywood, Hollywood hates the church. There's got to be some way to bridge that divide.'" - in an article by Jennifer Swan.

As I said in my original little “about me” tag response, I have felt called to ministry in this world. Whether it be film or live theater, that world is calling to me, both in its creative endeavors, and in its desperate need for the hope, truth, life, and light of Christ. Actors and directors in Hollywood and on Broadway are in as much need of the grace of our Lord as the starving orphans in the unreached people groups on the other side of the planet - same as your next door neighbor.

If Christians continue to tie themselves down, and group themselves together, cutting themselves off from the culture and the culture off from them, then we are doing absolutely no heavenly or earthly good to anyone.

So, you see, it’s not just the artistry (or, so often, lack thereof) in the Christian Film Industry™ that gets to me.

It’s the fact that the film media culture is a people group that the church as a whole is ignoring. We are ignoring the impact Hollywood has on the world around us and still trying to be relevant to that world, which is counter-productive and just plain silly.

It’s the fact that I see actors, actresses, producers, writers, who are obviously searching for the Something that will fill the void in their souls, and their primary exposure to Christianity and Christ - the only One who can satisfy them - is the Christian Film Industry™, which is largely full of broad and meaningless substance because heaven help us we should talk about something real, and then just plain bad art.

I believe God has called us to higher things than this.

Higher art, loving to create as he lovingly created us.

High impact, going deeper into the issues of our culture and our nature to address and satisfy problems and needs felt be every human, not just the church-goers who will show up for Sherwood’s next big thing.

So, yes, my pet peeve cracked from its proverbial nutshell:

I have issues with the Christian Film Industry

#end rant#i used the trademark symbol way too many times#long post#rags has opinions#christian films#movie making#i feel like i did not even touch on so many things#this is such a ramble#ragamusings#for certain

921 notes

·

View notes

Link

INTELLECTUAL MOVEMENTS advance on multiple levels — through academic and popular books and journals, via mass and social media, and in the populist grassroots imagination. At present, the world of Midwestern studies is advancing on all these fronts, although at different speeds.

On the level of popular but serious books, the forerunner is J. D. Vance’s Hillbilly Elegy (2016), much of which transpires in southern Ohio, though the story is mostly concerned with the culture of Appalachia. A few years on, Vance has been overtaken by writers of greater intricacy who are specifically focused on the Midwest. The literary world also needs to move on. While entertaining pitches from agents about “the next Hillbilly Elegy,” publishers searched for something new, something less conservative, something more nuanced. The results include three new books about the Midwest by three young authors (two first-timers), all released by major publishers, and each garnering a New York Times review. Collectively, they signal a new moment, a time of rejuvenation for a neglected American region, a springtime for the Midwest.

The most magnetic of these authors — and surely a voice to be reckoned with for many decades to come — is Meghan O’Gieblyn. After growing up in Michigan, O’Gieblyn went to college in Chicago and then landed at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, where she earned an MFA. While a student there, she penned most of the essays woven into Interior States. All of O’Gieblyn’s work is deeply pondered and researched, infused with a Midwestern pragmatism, and elevated by the author’s innate curiosity and intellectual acuity. Her prevailing method is logic, not passion; her style is persuasion, not badgering.

O’Gieblyn’s father sold industrial lubricant, so her family moved around the Midwest “to the kinds of cities that had been built for manufacturing.” In short, she knows the territory well. She is bonded to Lake Michigan, especially the beautiful shores around Muskegon, and can nimbly read the scenes of Chicago’s south side, its traces of industrialism and its bawdy bars. She recalls visits to Henry Ford’s Greenfield Village, a monument to the remembrance of things past, especially the Midwest’s old agrarian order. She drives down to the large Creation Museum in Indiana, in the midst of her own confusion over her diminishing Christian faith. The fading industrial remnants of Southern Chicago and Northern Indiana, and the ebbing of the old Christian order in the Midwest, conjure a “profound loss of telos, the realization that the industries and systems that built the region are no longer tenable.” If the old core of the Midwest has lost its vibrancy, its “bucolic peripheries” persist, undergirding the “autumnal sentimentalism” of the “Pure Michigan” campaign, but also the calming, woodsy, cabin culture that draws so many to the northern half of the Midwest.

As an emerging writer and intellectual, O’Gieblyn expected to leave the Midwest, to join the preponderant pattern of out-migration, to follow the interstates, the “sound of transit, or things passing through.” Instead, she stayed in her home region, becoming part of its stable rhythms while still feeling an “existential dizziness, a sense that the rest of the world is moving while you remain still.” As an intellectual, an analyst, a quiet observer with a monkish reserve, O’Gieblyn appreciates the Midwest’s “stoicism, a resistance to excitement that is native to this region” and its habit of “tuning out the fashions and revelations of the coastal cities, which have nothing to do with you.”

The trendy bakeries and co-ops and fair trade coffees and Orange You Glad It’s Vegan? cakes of Madison and the drone of NPR do not impress O’Gieblyn. She thinks Madisonians have “suffered from the fundamental delusion that we had elevated ourselves above the rubble of hinterland ignorance.” O’Gieblyn’s métier throughout her essays is intelligence and nuance and gratitude. The highlight of the book might be the chapters “On Subtlety,” which was first published last year in Tin House, and “American Niceness,” which ran in The New Yorker in 2017. Wisconsin, she says, “is a place where niceness is so ubiquitous that it seems practically constitutional”; in her work, and in her travels and speeches, she shows no sign of breaching these constitutional norms.

O’Gieblyn’s particular concern is faith, her internal beliefs, her journey within the Midwest toward a new state of mind — thus, the dual meaning of the smartly titled Interior States. O’Gieblyn grew up in a family that attended a shrinking Baptist church in southeast Michigan. She was homeschooled until the 10th grade and then attended Moody’s Bible Institute in Chicago. She left Moody’s after her sophomore year, and her dwindling faith and search for a new purpose form large chunks of the book. She dials up the pills and drinking and hard-living for a while, to contend with the “overwhelming despair at the absence of God.” But she also reads and thinks and begins to write, launching what we can confidently predict will be a triumphant career.

O’Gieblyn’s voice is consistently generous and inquiring. She still finds Christianity beautiful, though unconvincing, certainly not worthy of scorn. She takes a telescopic view, always considering ancestry and posterity and the world ahead — surely a flickering vestige of her biblical training — and rightly remains annoyed with electronic devices and the digital world’s “hypnotic […] assurance that nothing lies beyond the day’s serving of novel minutiae.” Instead of a fashionably snarky dismissal of John Updike, she attempts to understand his moment and his appeal, a rare maneuver indeed.

Soon after the appearance of O’Gieblyn’s Interior States came Sarah Smarsh’s memoir Heartland, an account of her life growing up in Kansas. The book has been reviewed in all the right places, and Smarsh has talked to all the key gatekeepers, large and small, orchestrating the literary equivalent of the “full Ginsburg.” She even became the master of ceremonies at the Topeka inauguration of the new Kansas governor, Laura Kelly, who last fall defeated Trump’s choice, Kris Kobach, a result widely cheered by The Resistance.

Smarsh’s coming-of-age experiences are not easy to summarize. Her grandmother, Betty, and her mother, Jeannie, grew up primarily in Wichita and other nearby places; both were teenage mothers. Due to fizzled marriages, protracted poverty, and various failed ventures, Jeannie had moved 48 times by the time she started high school. Smarsh’s greatest source of love and stability did not come from the maternal side of her family, urban-oriented and transitory as it was, but from Smarsh’s father, a genuinely kind and decent man who was descended from a long line of Kansas wheat farmers. Smarsh’s step-grandfather, Arnie, who married Betty (her seventh marriage), operated a small wheat farm west of Wichita, which provided a refuge for Smarsh, with a piano and a pool and a rural room to breathe when she needed to live away from her mother. Grandma Betty “found her happiest home in the country,” as did Smarsh. Smarsh’s encomium to rural life is reminiscent of Debra Marquart’s ruminations on the northern plains in The Horizontal World (2006).

In a sad breach of the Midwestern code described by O’Gieblyn, Smarsh’s mother was not nice to her daughter. As a result, Smarsh was left “emotionally impoverished,” a sharper source of agony, she implies, than her family’s financial constraints. Her frustrations with her mother are laced throughout the book, her swelling disgust palpable. When her mother leaves her father, Smarsh gives no explanation. When her mother leaves her new and likable and stable newspaper-columnist husband with the nice house, who subscribes to The New Yorker and reads art books and collects Beat poetry and watches Woody Allen movies and listens to NPR, Smarsh gives no explanation. Maybe none was given to her at the time. But Smarsh’s abrupt announcements of these splits leave the clear impression that she disapproved, that these decisions only brought more instability and financial pain. She hints that her mother was partying too much, stepping out, enjoying a nightlife she was deprived of as a young mother, but few details are provided. One feels Smarsh inching toward a full ventilation of her feelings but pulling back, seeking to protect her mother, not wanting to reignite simmering animosities.

By contrast, her treatment of Betty, her heroic grandmother, steals the show. After settling into her seventh marriage, on the wheat farm with Arnie, Betty finds some normalcy and success. She begins work at the Sedgwick County (Wichita) courthouse, working her way up to subpoena officer and even joining the Wichita Police Reserve. Smarsh bonds with Betty, along with an African-American county judge dubbed “Hang ’em High Watson,” over case files; she admires the young female district attorney, and contemplates the miseries of the parolees and prisoners. Betty brings a salty cynicism to the parade of excuses she hears from her wards about spotty childhoods: “Don’t give me that dysfunctional childhood bullshit. My family invented dysfunction.”

The difficulty of overcoming this dysfunction is the burden of Smarsh’s book. She carries it well, with a few qualifications. One can simultaneously offer a hard-boiled look at the complexity and hardship of prairie poverty while also rejecting the increasingly frequent and grand but tiresome pronouncement that the American-Dream-is-Dead, another form of beating the anti–Hillbilly Elegy dead horse. The Washington Post review insisted that Heartland is a “rebuke” to the “myth” that “clean living” can promote social advancement. But, in fact, Smarsh tends to show the opposite — that the DWIs, fights, drugs, drinking, excessive gambling, broken marriages, shoplifting, random shootings, car wrecks, teenage mothers, et cetera, do indeed tend to set back the Kansans she describes.

Smarsh eschews a simple morality tale. She wants her readers to understand the various forms and levels and intricacies and traps of poverty, first and foremost, but she does not blush at highlighting self-imposed stumbles. Smarsh lends credence to the advice dispensed to young Kansans, which has hardened into a foundational piece of conventional wisdom common to the center of the country: “Don’t act like a knothead or you’ll end up in jail.” In the end, Smarsh offers a qualified version of the American Dream: “You got what you worked for, we believed. There was some truth to that. But it was not the whole truth.”

To understand the first part of that truth, it is essential to pause and admire Smarsh’s resilience and fortitude. She vowed to work hard and overcome her circumstances. In the aspect of her book most widely panned by critics, Smarsh explains to her never-born child why she tried so hard to avoid teenage pregnancy. A snide New York Times reviewer mocked how Smarsh’s “unborn child pops into the prose like Ally McBeal’s Baby Cha-Cha.” But I found this device to be touching and real and, as Smarsh says, vital to her achievements: “[Y]ou kept me away from poison and danger.” She got into gifted programs, published a story in a national children’s magazine, won public speaking contests, was a homecoming queen candidate; she made it to the University of Kansas for her undergraduate degree and to Columbia University for a graduate degree, and recently she finished a stint at Harvard’s Shorenstein Center. She barely missed winning the National Book Award. There were no bullshit dysfunction excuses from Smarsh, as grandma Betty would say.

In the end, despite the lure of its simplicity and the tug of its narrative cohesion, Smarsh’s Heartland doesn’t really fit into our conventional political boxes. She examines poverty unflinchingly, but she also shows how the “cycle had been broken” with her success. She suggests ways to make poverty less difficult, but she is neither grandiose nor annoyingly didactic. In other words, Smarsh is real — Kansas hardscrabble, no-bullshit real. Smarsh’s realism taps into an older and once-prominent literary tradition from the Midwest, the region that broke the Northeast’s domination of the proper 19th-century Victorian drawing room. She’s in the line of Midwestern realists that includes Hamlin Garland and Theodore Dreiser.

Smarsh’s realism is closely connected to place. She writes powerfully of thunderstorms and prairie winds and the tornadoes that made Kansas famous. When Kansas-born Betty visited Chicago, she was not impressed with “The Windy City”: “Shit. They never seen wind.” To better understand the appeal of agrarianism and the traditions of small farms, Smarsh reads Wendell Berry. She sees how critical rural Kansas was to her plan to succeed: “[M]ost essential to my well-being was the unobstructed freedom of a flat, wide horizon.” As someone who understands and defends Kansas as a place, she grows weary of her home being “spurned by more powerful corners of the country as a monolithic cultural wasteland,” a “flyover country” populated by “backward” “rednecks” and “white trash.” The wider nation, she comes to see, viewed places like Kansas as “unimportant, liminal places. They yawned while driving through them, slept as they flew over them.” Smarsh calls for a new way of thinking about diversity, one that also stresses class and neglected regions of the country. She seeks to counter a form of inequality seldom commented on but frequently hinted at — the regional inequality that leaves New York and California the dominant forces in our culture.

If O’Gieblyn is the cerebral analyst and Smarsh the plucky climber of this trio, then Stephen Markley is the guy in the fluorescent green vest running the jackhammer on the streets of Akron while imagining happy hour. Like O’Gieblyn and Smarsh, Markley is young and Midwestern and on the brink of a major literary career. Growing up in Mount Vernon, Ohio, about an hour north of Columbus in the center of the state, he played basketball and partied a bit but maintained his grades. His social life was bonfires, dances, and football games. His parents are professors — his mother, Laurie Finke, is Kenyon College’s first tenure-track director of women’s and gender studies, and his father, Robert Markley, is a prominent professor of English at the University of Illinois. Markley majored in creative writing and history at Miami University in Oxford, Ohio, and then freelanced in Chicago for six years while writing two nonfiction books. For three years, he lived in Iowa City, where he earned a degree from the Iowa Writers’ Workshop and began work on his novel, Ohio. (MGM recently bought the rights, and it will be made into a television series.) He’s now in Los Angeles writing a new book and working as a screenwriter. An ex-girlfriend has described Markley “as a Midwestern bro who happened to make it.”

Markley sees Ohio as a hopeful novel, rejecting some critics’ charges of nihilism, and he is not wrong. But it takes some readerly endurance to reach that conclusion. Ohio is the story of one day in the town of New Canaan, Ohio (population 15,000, located halfway between Columbus and Cleveland). It focuses on The Big Chill–ish re-convergence of several young lives a decade after they all graduated from high school. Some of their comrades were slain by drugs, some by war; the survivors struggle with their identities, one becoming consumed with the clichés of left-wing politics. The backdrop is the death of Rick Brinklan, whose parents were “prototypical kind, plainspoken midwesterners.” Rick was an earnest and patriotic running back at New Canaan High School, with an “electric core of decency,” who bravely defended the honor of victimized classmates, while his friend the social justice warrior (Zuccotti Park, Mexican collective farms, Cambodian NGOs) wilted under the pressure. Rick went off to Ohio State to become a math teacher and coach, but dropped out to join the Marines after 9/11, ending up dead in Iraq.

Ohio is brilliantly structured and a challenge to set aside. While executed well, the numerous flashbacks and the complex connections among the characters require close attention; the reader is advised to make a small chart inside the book’s front cover for easy reference. Markley’s descriptive powers and characterization skills shine throughout. A school is an “institutional slab of crap architecture with that sixties-era authoritarian aura to its brick Lego look.” A bar is “one of those sad dips in the dunes of the rural-industrial Midwest.” A grocery store is the “epicenter of New Canaan stop-and-chat time sucks.” As for Rick, he was the

kind of guy you’d find teeming across the country’s swollen midsection: toggling Budweiser, Camels, and dip, leaning into the bar like he was peering over the edge of a chasm, capable of near philosophy when discussing college football or shotgun gauges, neck on a swivel for any pretty lady but always loyal to his true love, most of his drinking done within a mile or two of where he was born.

Markley’s most salient descriptions are reserved for Ohio itself. Characters cross the Ohio River into the state or cross the hills around the Mahoning Valley, where the “oblate plain of Northeast Ohio came into repose.” They pass through the “flat expanse of cornfields, barns, and country homes that peppered the drive south to Ohio’s capital,” always watching closely for deer. They get sunburned up on Lake Erie and visit Cedar Point and take boats out to South Bass Island. The kids go to the country to drink: “Shit, if you can’t drive these country roads loaded on cheap whiskey what’s the point of being from Ohio?” Characters bounce between Dayton, Toledo, Mansfield, Youngstown, Akron, Marysville, Dover, Worthington, Springfield, Cincinnati, Canton, Cedar Point, Van Wert, and Lima. They take in the rural and forgotten places that Markley calls “Deep Ohio.”

The students of New Canaan learned the details of Ohio history in seventh grade from the devoted Mrs. Bingham, who was a teacher for 50 years and had thick “Buckeye blood.” Bingham taught Ohio history by way of stories of savage frontier warfare, of General “Mad” Anthony Wayne, Little Turtle, the Battle of Fallen Timbers, the Gnadenhutten massacre, and Marcus Spiegel (a German Jew who immigrated to Ohio and led the 120th Ohio Volunteer Infantry as it sliced through Mississippi and Louisiana and learned, as he said, the “horrors of slavery”). All this expertise on Midwestern history brings to mind the work of Andrew Cayton of Miami University — and, sure enough, when an Ohio character visits his former high school teacher in the nursing home, he tells her: “I’ve actually been rereading some Ohio stuff. Andrew Cayton and this historian Rob Harper.” [1] The intense focus on early Ohio recalls a comment by the novelist Dawn Powell of Mount Gilead, Ohio (30 miles from Markley’s Mount Vernon) — which, oddly enough, serves as an epigraph for O’Gieblyn’s book: “All Americans come from Ohio originally, if only briefly.”

Markley chronicles the ravages of deindustrialization — New Canaan is hurt by the loss of a steel-tube plant and two plate-glass manufacturers — and recounts the ravages of opioids and other drugs, as well as episodes of sexual abuse. Channeling the themes of the century-old “revolt from the village” genre, [2] he at times sees the town as the “poster child of middle-American angst,” finds the “raw wrath roosting in the small towns, suburbs, and exurbs of Middle America,” and detects an abiding “alienation.” And yet the town has fierce defenders — like Rick, of course, and also Dan Eaton, another New Canaanite who joined the military. Eaton tacks an Abraham Lincoln quote to his corkboard: “I like to see a man proud of the place in which he lives. I like to see a man live so that his place will be proud of him.” After a chat with her high school teacher, one young woman “marveled at how many extremely decent people she’d known in this place. How much she’d taken them for granted.”

The book bounces between love and contempt for small-town Ohio in a manner that makes broad conclusions impossible. Momentary truths are found in the stories of individuals who struggle to stabilize their lives after going through a rough patch, an experience that is hard for them to articulate to others. In this regard, Markley resembles Sherwood Anderson, who found his muse close to Markley’s Mount Vernon in Elyria, and whose varied characters in Winesburg, Ohio (1919) contend with forces similar to those in Ohio: secrets, rumors, poverty, muted emotions.

These three new books display both odd convergences and intra-regional variations. A character’s religious de-conversion in Ohio recalls much of O’Gieblyn’s story in Interior States, and Smarsh says too that she has abandoned the pro-life Catholicism of her youth. The poverty discussed in Smarsh’s Heartland recalls the struggles of one of Markley’s young adults, working at the Walmart in Van Wert over by the Ohio-Indiana line. The drugs that trip up Smarsh’s relatives at times kill Markley’s characters.

These similar themes play out over variable Midwestern terrain. Smarsh’s flat Kansas of tornadoes and dust is distinct from Markley’s hilly and green Ohio. Smarsh’s Wichita feels, at times, like a Midwestern borderland, one that bumps into the South and witnesses some cultural cross-pollination. [3] Smarsh does not comment on Wichita’s proximity to the southern pale, but Markley is adept at distinguishing Ohio from what comes farther South. In his military scenes, he describes chip-on-the-shoulder Kentuckians who view Ohioans as “effete snobs sticking their noses up at the real salt-of-the-earth south of the river.” For their part, Ohioans mock Kentuckians for calling their towns “hollers” and make Kentucky jokes: “You know why they can’t teach driver’s ed and sex ed on the same day in Kentucky? ’Cuz that poor fucking horse gets too tired.”

This variation and texture highlights an intra-regional diversity across the Midwest, a complexity that is captured not only by O’Gieblyn, Smarsh, and Markley, but also by many other novels of the current wave. These include Peter Geye’s Wintering (2016), Keith Lesmeister’s We Could’ve Been Happy Here (2017), Nickolas Butler’s The Hearts of Men (2017), Melissa Frateriggo’s Glory Days (2017), Celeste Ng’s Little Fires Everywhere (2017), Sarah Stonich’s Laurentian Divide (2018), Steve Wingate’s Of Fathers and Fire (2019), and J. Ryan Stradal’s greatly anticipated follow-up to his Kitchens of the Great Midwest (2015), The Lager Queen of Minnesota (2019).

Similarly, in nonfiction, the wave includes Ted Genoways’s This Blessed Earth: A Year in the Life of an American Family Farm (2017), Matthew Desmond’s Evicted (2017), Amy Goldstein’s Janesville: An American Story (2018), Eve Ewing’s Ghosts in the Schoolyard: Racism and School Closings on Chicago’s South Side (2018), Andy Oler’s Old-Fashioned Modernism: Rural Masculinity and Midwestern Literature (2019), Jim Reese’s Bone Chalk (2019), and Carson Vaughan’s Zoo Nebraska: The Dismantling of an American Dream (2019). It also includes the wonderful work of Belt Publishing (as in Rust Belt), which, for the past few years, has released such titles as Edward McClelland’s How to Speak Midwestern (2016) and the anthologies Grand Rapids Grassroots (2017) and The Milwaukee Anthology (2019). And it includes recently launched journals such as Middle West Review, Studies in Midwestern History, Midwest Gothic, and The New Territory, along with the creation of the Midwestern History Association, which hosts an annual conference in Michigan in conjunction with the Hauenstein Center in Grand Rapids. [4]

The Midwestern studies wave, in other words, is building. O’Gieblyn, Smarsh, and Markley are riding it. The region, after a half-century of neglect, is having its moment. Even the coasts are starting to notice.

To have more than a moment, however, the Midwest must build some enduring institutions. It cannot depend on the periodic notice of The New York Times, an unreliable arrangement at best and a position of colonial domination at worst. The dependence on the Times and the concentrated power of Manhattan’s literary scene leave interior writers forced to produce work “warped to the market” (as Hamlin Garland once said during an earlier era of burgeoning regionalist energies) — a distant market with distinct interests, which is driven by the logic of commodification and the demand for the edgy and the novel. The Midwest must also overcome a history of failed regionalist ventures, such as Midwest Review, Mid-America, Upper Midwest History, Flyover Country Review, and The Midwesterner.

In sum, the Midwest needs a sustained cultural presence so that its cultural production does not have to be consistently revived. The Midwestern literary scholar Sara Kosiba has noted John Updike’s shrewd comment on the literary output of Ohioan Dawn Powell, which he saw as “doomed to a perpetual state of revival.” [5] The Midwest needs an archipelago of university-based regional studies institutes, such as those that the South and the West enjoy. It needs a permanent presence on Big Ten campuses in the form of Midwestern studies classes. It needs to become a strong cultural force independent of the coastal gaze. This would be a revolutionary regionalist revival, one with permanence, not a fleeting spasm from the American center destined to repeat itself in another two decades.

¤

An adjunct professor of history at the University of South Dakota, Jon K. Lauck is the author of From Warm Center to Ragged Edge: The Erosion of Midwestern Literary and Historical Regionalism, 1920-1965(University of Iowa Press, 2017).

¤

[1] On the early passing of Cayton and the significance of his career in Midwestern history, see Jon K. Lauck, “Remembrance: Andrew R. L. Cayton: Midwesterner, 1954-2015,” Middle West Review vol. 2, no. 2 (Spring 2016), 201–205. Harper is a graduate of Oberlin College in Ohio and earned his PhD at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. He now teaches at University of Wisconsin-Stevens Point and is the author of Unsettling the West: Violence and State Building in the Ohio Valley (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2017).

[2] Jon K. Lauck, “The Myth of the Midwestern ‘Revolt from the Village,’” MidAmerica vol. 40 (2013), 39–85.

[3] See Jay Price, “Where the Midwest Meets the Bible Belt: Using Religion to Explore the Midwest’s Southwestern Edge,” in Jon K. Lauck, (ed), The Interior Borderlands: Regional Identity in the Midwest and Great Plains (Sioux Falls: Center for Western Studies, 2019), 229-42 and Price, “Dixie’s Disciples: The Southern Diaspora and Religion in Wichita, Kansas,” Kansas History vol. 40 (Winter 2017-18), 244–261.

[4] See Jon K. Lauck, “The Origins and Progress of the Midwestern History Association, 2013-2016,” Studies in Midwestern History vol. 2, no. 11 (2016), 139–149.

[5] Sara Kosiba (ed), A Scattering Time: How Modernism Met Midwestern Culture (Hastings, NE: Hastings College Press, 2018), ix.

The post The Neo-Regionalist Moment: Hearing the Emerging Voices of the American Center appeared first on Los Angeles Review of Books.

from Los Angeles Review of Books https://ift.tt/2UWToUp

0 notes

Link

INTELLECTUAL MOVEMENTS advance on multiple levels — through academic and popular books and journals, via mass and social media, and in the populist grassroots imagination. At present, the world of Midwestern studies is advancing on all these fronts, although at different speeds.

On the level of popular but serious books, the forerunner is J. D. Vance’s Hillbilly Elegy (2016), much of which transpires in southern Ohio, though the story is mostly concerned with the culture of Appalachia. A few years on, Vance has been overtaken by writers of greater intricacy who are specifically focused on the Midwest. The literary world also needs to move on. While entertaining pitches from agents about “the next Hillbilly Elegy,” publishers searched for something new, something less conservative, something more nuanced. The results include three new books about the Midwest by three young authors (two first-timers), all released by major publishers, and each garnering a New York Times review. Collectively, they signal a new moment, a time of rejuvenation for a neglected American region, a springtime for the Midwest.

The most magnetic of these authors — and surely a voice to be reckoned with for many decades to come — is Meghan O’Gieblyn. After growing up in Michigan, O’Gieblyn went to college in Chicago and then landed at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, where she earned an MFA. While a student there, she penned most of the essays woven into Interior States. All of O’Gieblyn’s work is deeply pondered and researched, infused with a Midwestern pragmatism, and elevated by the author’s innate curiosity and intellectual acuity. Her prevailing method is logic, not passion; her style is persuasion, not badgering.

O’Gieblyn’s father sold industrial lubricant, so her family moved around the Midwest “to the kinds of cities that had been built for manufacturing.” In short, she knows the territory well. She is bonded to Lake Michigan, especially the beautiful shores around Muskegon, and can nimbly read the scenes of Chicago’s south side, its traces of industrialism and its bawdy bars. She recalls visits to Henry Ford’s Greenfield Village, a monument to the remembrance of things past, especially the Midwest’s old agrarian order. She drives down to the large Creation Museum in Indiana, in the midst of her own confusion over her diminishing Christian faith. The fading industrial remnants of Southern Chicago and Northern Indiana, and the ebbing of the old Christian order in the Midwest, conjure a “profound loss of telos, the realization that the industries and systems that built the region are no longer tenable.” If the old core of the Midwest has lost its vibrancy, its “bucolic peripheries” persist, undergirding the “autumnal sentimentalism” of the “Pure Michigan” campaign, but also the calming, woodsy, cabin culture that draws so many to the northern half of the Midwest.

As an emerging writer and intellectual, O’Gieblyn expected to leave the Midwest, to join the preponderant pattern of out-migration, to follow the interstates, the “sound of transit, or things passing through.” Instead, she stayed in her home region, becoming part of its stable rhythms while still feeling an “existential dizziness, a sense that the rest of the world is moving while you remain still.” As an intellectual, an analyst, a quiet observer with a monkish reserve, O’Gieblyn appreciates the Midwest’s “stoicism, a resistance to excitement that is native to this region” and its habit of “tuning out the fashions and revelations of the coastal cities, which have nothing to do with you.”

The trendy bakeries and co-ops and fair trade coffees and Orange You Glad It’s Vegan? cakes of Madison and the drone of NPR do not impress O’Gieblyn. She thinks Madisonians have “suffered from the fundamental delusion that we had elevated ourselves above the rubble of hinterland ignorance.” O’Gieblyn’s métier throughout her essays is intelligence and nuance and gratitude. The highlight of the book might be the chapters “On Subtlety,” which was first published last year in Tin House, and “American Niceness,” which ran in The New Yorker in 2017. Wisconsin, she says, “is a place where niceness is so ubiquitous that it seems practically constitutional”; in her work, and in her travels and speeches, she shows no sign of breaching these constitutional norms.

O’Gieblyn’s particular concern is faith, her internal beliefs, her journey within the Midwest toward a new state of mind — thus, the dual meaning of the smartly titled Interior States. O’Gieblyn grew up in a family that attended a shrinking Baptist church in southeast Michigan. She was homeschooled until the 10th grade and then attended Moody’s Bible Institute in Chicago. She left Moody’s after her sophomore year, and her dwindling faith and search for a new purpose form large chunks of the book. She dials up the pills and drinking and hard-living for a while, to contend with the “overwhelming despair at the absence of God.” But she also reads and thinks and begins to write, launching what we can confidently predict will be a triumphant career.

O’Gieblyn’s voice is consistently generous and inquiring. She still finds Christianity beautiful, though unconvincing, certainly not worthy of scorn. She takes a telescopic view, always considering ancestry and posterity and the world ahead — surely a flickering vestige of her biblical training — and rightly remains annoyed with electronic devices and the digital world’s “hypnotic […] assurance that nothing lies beyond the day’s serving of novel minutiae.” Instead of a fashionably snarky dismissal of John Updike, she attempts to understand his moment and his appeal, a rare maneuver indeed.

Soon after the appearance of O’Gieblyn’s Interior States came Sarah Smarsh’s memoir Heartland, an account of her life growing up in Kansas. The book has been reviewed in all the right places, and Smarsh has talked to all the key gatekeepers, large and small, orchestrating the literary equivalent of the “full Ginsburg.” She even became the master of ceremonies at the Topeka inauguration of the new Kansas governor, Laura Kelly, who last fall defeated Trump’s choice, Kris Kobach, a result widely cheered by The Resistance.

Smarsh’s coming-of-age experiences are not easy to summarize. Her grandmother, Betty, and her mother, Jeannie, grew up primarily in Wichita and other nearby places; both were teenage mothers. Due to fizzled marriages, protracted poverty, and various failed ventures, Jeannie had moved 48 times by the time she started high school. Smarsh’s greatest source of love and stability did not come from the maternal side of her family, urban-oriented and transitory as it was, but from Smarsh’s father, a genuinely kind and decent man who was descended from a long line of Kansas wheat farmers. Smarsh’s step-grandfather, Arnie, who married Betty (her seventh marriage), operated a small wheat farm west of Wichita, which provided a refuge for Smarsh, with a piano and a pool and a rural room to breathe when she needed to live away from her mother. Grandma Betty “found her happiest home in the country,” as did Smarsh. Smarsh’s encomium to rural life is reminiscent of Debra Marquart’s ruminations on the northern plains in The Horizontal World (2006).

In a sad breach of the Midwestern code described by O’Gieblyn, Smarsh’s mother was not nice to her daughter. As a result, Smarsh was left “emotionally impoverished,” a sharper source of agony, she implies, than her family’s financial constraints. Her frustrations with her mother are laced throughout the book, her swelling disgust palpable. When her mother leaves her father, Smarsh gives no explanation. When her mother leaves her new and likable and stable newspaper-columnist husband with the nice house, who subscribes to The New Yorker and reads art books and collects Beat poetry and watches Woody Allen movies and listens to NPR, Smarsh gives no explanation. Maybe none was given to her at the time. But Smarsh’s abrupt announcements of these splits leave the clear impression that she disapproved, that these decisions only brought more instability and financial pain. She hints that her mother was partying too much, stepping out, enjoying a nightlife she was deprived of as a young mother, but few details are provided. One feels Smarsh inching toward a full ventilation of her feelings but pulling back, seeking to protect her mother, not wanting to reignite simmering animosities.

By contrast, her treatment of Betty, her heroic grandmother, steals the show. After settling into her seventh marriage, on the wheat farm with Arnie, Betty finds some normalcy and success. She begins work at the Sedgwick County (Wichita) courthouse, working her way up to subpoena officer and even joining the Wichita Police Reserve. Smarsh bonds with Betty, along with an African-American county judge dubbed “Hang ’em High Watson,” over case files; she admires the young female district attorney, and contemplates the miseries of the parolees and prisoners. Betty brings a salty cynicism to the parade of excuses she hears from her wards about spotty childhoods: “Don’t give me that dysfunctional childhood bullshit. My family invented dysfunction.”

The difficulty of overcoming this dysfunction is the burden of Smarsh’s book. She carries it well, with a few qualifications. One can simultaneously offer a hard-boiled look at the complexity and hardship of prairie poverty while also rejecting the increasingly frequent and grand but tiresome pronouncement that the American-Dream-is-Dead, another form of beating the anti–Hillbilly Elegy dead horse. The Washington Post review insisted that Heartland is a “rebuke” to the “myth” that “clean living” can promote social advancement. But, in fact, Smarsh tends to show the opposite — that the DWIs, fights, drugs, drinking, excessive gambling, broken marriages, shoplifting, random shootings, car wrecks, teenage mothers, et cetera, do indeed tend to set back the Kansans she describes.

Smarsh eschews a simple morality tale. She wants her readers to understand the various forms and levels and intricacies and traps of poverty, first and foremost, but she does not blush at highlighting self-imposed stumbles. Smarsh lends credence to the advice dispensed to young Kansans, which has hardened into a foundational piece of conventional wisdom common to the center of the country: “Don’t act like a knothead or you’ll end up in jail.” In the end, Smarsh offers a qualified version of the American Dream: “You got what you worked for, we believed. There was some truth to that. But it was not the whole truth.”

To understand the first part of that truth, it is essential to pause and admire Smarsh’s resilience and fortitude. She vowed to work hard and overcome her circumstances. In the aspect of her book most widely panned by critics, Smarsh explains to her never-born child why she tried so hard to avoid teenage pregnancy. A snide New York Times reviewer mocked how Smarsh’s “unborn child pops into the prose like Ally McBeal’s Baby Cha-Cha.” But I found this device to be touching and real and, as Smarsh says, vital to her achievements: “[Y]ou kept me away from poison and danger.” She got into gifted programs, published a story in a national children’s magazine, won public speaking contests, was a homecoming queen candidate; she made it to the University of Kansas for her undergraduate degree and to Columbia University for a graduate degree, and recently she finished a stint at Harvard’s Shorenstein Center. She barely missed winning the National Book Award. There were no bullshit dysfunction excuses from Smarsh, as grandma Betty would say.