#this is examining continuity as the literal history of these paper people and enabling them to grow (up) issue by issue

Text

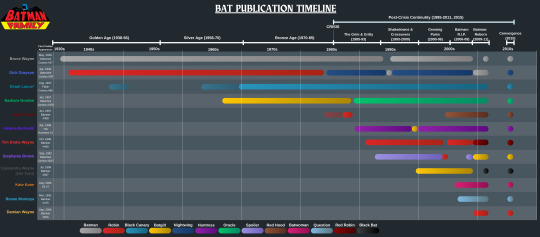

Bat Timeline vs Bat Publication Timeline

I kept my receipts and citations here. Also, I used cover dates.

Neat things I noticed:

Nothing much happened in Gotham until Robin arrived both in continuity and in print history. Sorry but your lone wolf Batman doesn't exist :P

Dick permanently becomes Batman at the same age Bruce was when he became Batman; 25. Kinda poetic if you ask me.

Babs was Oracle longer than she was Batgirl in both continuity and publication history!!

Completely forgot that Dinah was literally her own mother once upon a time. Weird stuff.

There's not enough Jason!Robin stories to fit the 3 years some fans claim he was Robin for. Also the 3 years idea doesn't work if you track Dick's age. My guess is he was originally younger than 15 when he died but DC aged him up so he could be an adult when he returned as Red Hood.

It's pretty clear that Helena's integration into the group began the expansion of this complicated "family unit". She set the precedent for those noirish vigilante work relations.

Tim has to be a vampire if he's meant to be 17 three whole very explicit in-continuity years after he had his 16th birthday.

Stephanie has basically been in this gig as long as Tim! And almost as long as Helena too. Proper seasoned ass-kicker who Damian should look to for pointers.

Also remembered that Cassandra's Batgirl run is the best thing to come out of Gotham in the early 2000s.

I dunno I think the One Year Later timeskip was just unnecessary.

Kate and Renee are almost as new to the vigilante gig as Damian!

Bat-adjacent Rose Wilson was said to be 14 during her first appearance around Year 15 so she's the same age Tim.

Not Bat related but Lian Harper's age works with my timeline so yay! Born early Year 14, she's 5 during Cry for Justice in Year 19.

I have a theory, based off of Batman #416, that Dick graduated high school at 17. He says he was Bruce's partner for 6 years and that after he was fired; he left college after the 1st semester, then moved around the country, had his own adventures, and "eventually" ended up with the Titans. Also, he was 21 during the Titans' 3rd anniversary (New Titans v2 #71) and 19 when he became Nightwing (Tales of the Titans #44) so the Titans (re-)formed when he was 18. This means he probably only turned 18 in the academic year he began college (or has a summer birthday). So he was Bruce's partner from ages 11-17, did his own thing for a while as he did in the 70s, eventually joined the Titans at 18, and became Nightwing at 19. Jason comes into the picture soon after Dick retires the Robin identity.

#“what's the point of a timeline; it's not meant to make sense that way; no one ages” STFU#the point of a timeline is solidifying that characters do age and that time is able to flow! Cuz time's an interesting theme to explore!#this is examining continuity as the literal history of these paper people and enabling them to grow (up) issue by issue#batman#bat family#batfam#dc comics#comics#timeline#bruce wayne#dick grayson#barbara gordon#dinah lance#jason todd#helena bertinelli#tim drake#stephanie brown#cassandra cain#kate kane#renee montoya#damian wayne#robin#batgirl#black canary#huntress#nightwing#the spoiler#oracle#red robin#red hood

352 notes

·

View notes

Text

Could AI render human labour in all fields useless?

What is Artificial Intelligence; What is it used for and what is the impact?

AI or Artificial Intelligence is the theory and development of computer systems to be able to perform tasks and jobs that normally requires human intelligence. For example: visual perception, speech recognition, decision-making, etc. -Oxford Dictionary

Artificial intelligence has a myriad of uses such as:

Non player characters in video games

Stock market trading bots

Content filters on social media

Autopilot on an aeroplane

Self-Driving cars

Artificial Intelligence is also being used in extremely experimental ways. One of these cases is Watson by IBM. Watson had made an appearance on television beating people at the game show Jeopardy, but his directive is to learn how humans express medical issues in their own words and try to give an accurate diagnosis. He has already gotten a start by trying to diagnose lung cancer patients.

This topic has been extremely relevant in recent years due to the ever increasing speed of innovation in the modern world. There have been countless tests proving time and time again that AI is better and could eventually become better than human physical and mental labour. This topic has been talked about by many authoritative figures (Elon Musk, Stephen Hawking, Bill Gates, etc). There have been politicians discussing it but only one is doing something about it. Andrew Yang is an American presidential candidate who is taking a unique political side on AI. He is taking in relevant information from trusted sources and he is proposing a solution called UBI (universal basic income). He proposes that due to AI taking away jobs from many in the US that he is giving a ‘freedom dividend’ of $1000 per American citizen every month to allow our capitalist society to continue with a high unemployment through no fault of their own.

How does artificial intelligence work?

Artificial intelligence is a broad term for a lot of different algorithms but the main branch that is associated with ‘taking over jobs’ is machine learning. The way machine learning works is that you give the algorithm data and an operation on what to do with that data. They begin analysing it and teach themselves the relationships between the data and how to complete the task at hand. This principal is most notably found in online retail. Amazon for example gets its algorithms to analyse the data you produce on their website and these algorithms produce a list of items you are more likely to purchase and they then recommend them to you.

History of Artificial Intelligence

The concept of living machines that act like humans has been around ever since the ancient Greeks but artificial intelligence was not officially named as such until 1956 at a conference at Dartmouth College in New Hampshire where the term artificial intelligence was coined by John McCarthy who is credited as one of the founding fathers of AI along with Alan Turing, Marvin Minsky and Herbert A. Simon. -Washington University

But proper funded research did not begin until the 1960’s when the Department of Defence funded various research efforts and there were various other laboratories that appeared across the world. Herbert Simon was extremely optimistic about the future of AI stating “machines will be capable, within twenty years, of doing any work a man can do”. But during the 70’s research had slowed down a lot due to some unexpected issues with creating a well performing set of artificial neurons. These issues were spotted by Sir James Lighthill. But they were corrected.

By the 1980’s artificial intelligence has received a resurgence in popularity and investment because of the creation of expert systems which are a branch of ai which can simulate/replicate the knowledge and skill of humans. By 1985 the market of AI had reached 1 billion USD. Simultaneously in Japan they were developing the ‘fifth generation computer system’ which sparked some intrigue for the UK and the US so they began to fund further research into AI.

In the 1990’s and early 2000’s AI was being used more frequently for things such as video game NPC’s and the stock market (as I have previously mentioned). The reason for the success and popularity is the increasing power of computers and the increasing availability of them. In 1997 an AI program called deep blue was the first chess playing AI to beat a reigning champion.

Why AI will not take our jobs

Artificial intelligence and automation has proven to be very effective and efficient in low-skilled, repetitive jobs. But in recent years there has been an ever increasing concern that artificial intelligence will advance so quickly that it will be able to complete white collar jobs such as those in an office. While it’s easy to get scared and worry about the security of your job we first have to look at the research and facts. The World Bank’s Development report of 2019 pushes the idea forward that, while automation displaces workers it creates just as many jobs to balance the situation and allow them to continue to earn money and keep the economy growing. According to the report the total Labour Force has been increasing ever since 1993.

Figure 0.4 World Bank’s World Development Report

The traditional office has changed dramatically over the past fifty years. For instance people are not accounting by calculating with a calculator and a piece of paper they have software to do this for them. This does not mean that the software has replaced their job, it has just improved the way they work. Automation and computerisation has made things easier, ever increasingly scaleable quicker and more productive. Artificial intelligence is not taking away from people’s jobs, it’s either improving them or giving them the opportunity to modify their skill set to suit other industries that AI will create.

Why AI will take our jobs

The development of artificial intelligence can be classified in three different waves, the first wave was the attempt to develop general intelligence comparable to a human, the second wave was the development of expert systems which aid in small scale decision making such as medical diagnoses and the third wave is the development of machine learning. -source 1

There are many fields where AI is being implemented but finance is one of the most prominent as businesses would like to turn a profit from their investments. These AI algorithms can also: reduce costs, minimise risks, prevent fraud, verify borrowers and evaluate their solvency, as well as make predictions and perform other tasks for the company they work for.

The main focus of the AI finance developments are the stock market. Instead of somebody hiring a trained market evaluator they can just purchase an AI algorithm which in a lot of cases works more effectively at looking at the state of the market giving you the best companies to invest in.

An example of this is a study by Eureka-hedge where they gave 23 hedge funds to human investors and 23 hedge funds to AI for investment. The funds given to the investors gave an annual increase (yield) of a range of 1.62% to 2.62% meanwhile the AI gave an annual yield of 8.44%. The researchers contribute this fact to the AI constantly repeating testing of the market rather than accumulating data like humans do.. -Eureka Hedge (From source1)

Artificial intelligence is implemented in many other other ways as well such as creating other AI algorithms. Google’s AI system learned how to create other machine learning algorithms better and make them more efficient than human created ones. The test for the created algorithms was image identification. The AI trained algorithm was able to 43% of the objects it was tasked to identify in the image whereas the human created AI was only able to identify 39% of them.

Google’ CEO Sundar Pichai had this statement at a presentation in 2017 saying that AI does not fully replace humans currently but allows more people to be able to “develop” AI. -

“Today these are handcrafted by machine learning scientists and literally only a few thousand scientists around the world can do this. We want to enable hundreds of thousands of developers to be able to do it.”

-Wired AI creating AI better than humans

Another way AI is beating humans is in the legal field. A study conducted by LawGeex was to compare AI to 20 lawyers who worked for companies such as Goldman Sachs and Cisco and they had dozens of years of experience working for these companies. Their task was to evaluate the risks contained in five different Non Disclosure Agreements and identify 30 specific legal points.

From the results we can see that the AI system showed an average accuracy of 94% while the lawyers average was 85%. The maximum accuracy for the AI 100% while the lawyers was 94%. The average time taken by the lawyers was 92 minutes, the AI’s was 26 seconds

-LawGeex Lawyers v. AI

Finally the last case study is where AI can be better than humans in the medical field. This study was to test the accuracy of Pap tests for cancerous signs.

Mark schniffman. Senior editor : Our findings show that a deep learning algorithm can use images collected during routine cervical cancer screening to identify precancerous changes that, if left untreated, may develop into cancer. In fact, the computer analysis of the images was better at identifying precancer than a human expert reviewer of Pap tests under the microscope (cytology).

In general, the algorithm worked better than all standard screening tests in predicting all cases diagnosed in the Costa Rica-based study. Automatic visual assessment revealed precancerous disease with greater accuracy (AUC = 0.91) than human examination (AUC = 0.69) or conventional cytology (AUC = 0.71). An AUC value of 0.5 indicates a test that is no better than a random one, while an AUC value of 1.0 represents a test that has perfect accuracy in detecting disease. From these results we can deduce that humans do not

This Graph shows how likely each profession is to be automated

Source: https://www.economist.com/graphic-detail/2018/04/24/a-study-finds-nearly-half-of-jobs-are-vulnerable-to-automation

As you can see, low skill jobs such as construction, cleaning, driving and garment manufacturing are at high risk of automation. Jobs that require human emotion and connection such as hospitality, upper management and politics and teaching are extremely unlikely as robots cannot socialise and recognise emotions.

This graph details the level of automation that the OECD predicts in each country in the near future.

As you can see 43 percent of irish jobs are susceptible to becoming automated. This figure is largely dependent upon which sector of the economy your country has the majority employed in. For example countries with a lot of low skilled primary economic activities such as farming or forestry are going to have a higher percentage of automated employment. The highest percentage of automation is Slovakia and the Lowest is New Zealand

My opinion:

Artificial intelligence will and is currently eliminating jobs, however at the moment it is extremely difficult to predict the future of technology and the countless opportunities it could provide. The future generations entering the workforce need to increase their skill belt in order to compete with AI or algorithms. But AI (currently) cannot replicate human skills such as critical thinking, managing and recognising emotions. These are skills which enhance jobs which require teamwork. AI has some other very big flaws such as high cost in installation, maintenance and the countless amounts of updates to prevent malfunction but in a lot of cases it can be beneficial to the company and its employees as it removes the need for people to waste time and productivity on tasks which an AI can easily complete. In the far future AI will become more competent than humans at jobs and work in general but in our lifetime AI will not render all human labour useless. For now it will take a large proportion of low skill work but a lot of white collar work will just be improved upon but not replaced by AI. The way our society works is based on consuming and to be able to consume you have to have money and to get money you have to earn through working in a job, so if nobody can make money how will the economy continue to prosper?

1 note

·

View note

Text

On Spaces and Lines (Or the Things That Connect and Separate)

In her essay A Hero is A Disaster: Stereotypes Versus Strength in Numbers, Rebecca Solnit talks of our preoccupation with lone victors that often leads us to make light of the potency of collective action. She writes of her friend, legal expert and author Dahlia Lithwick, who was laying groundwork for a book on women lawyers who have argued and won civil rights cases against the Trump administration in the past two years. Her goal was to diffuse the spotlight from famed individuals—such as Ruth Bader Ginsburg, about whom many advised her to write instead—and onto lesser known lawyers. Elsewhere in the book, in City of Women, Solnit writes of the names which we give to our built environment: The rivers, roads, statues and colleges named after prominent, often white men; generals and captains whose shadows drape over their armies. One essay over, in Monumental Change and the Power of Names, she writes of the demolition and renaming of such monuments; changes that have shifted narratives and righted histories. She declares: “Statues and names are not in themselves human rights or equal access or a substitute for them. But they are crucial parts of the built environment, ones that tell us who matters and who will be remembered.”

I live in a quaint old neighbourhood in Singapore known as the Cambridge Estate. The vicinity is made up of roads named after idyllic English counties: Kent, Dorset, Durham, Norfolk, Northumberland; all a few minutes of walk away from the Farrer Park subzone—named after Roland John Farrer, who presided over the Singapore Municipal Commission, a body tasked to oversee local urban affairs and development under the British colonial rule. My block, an old building owned by the Housing Development Board, along with the streets that surround it, have seen some construction and renovation work in the past months. As Singapore went into lockdown at the start of April (which they prefer to call Circuit Breaker, God knows why, I’d say it’s some kind of a performative attempt at benevolence), most of the work have ceased. The roadwork at the intersection of Dorset and Kent, however, continued up until a week back. I eyed the workers, many of them migrants, from behind my mask as I crossed the street. They toiled away under the blistering sun, and I was reminded that elsewhere, on the outskirts of the city, the outbreak has reached the foreign workers’ dormitories; making prisons out of their rooms.

***

“Singapore Seemed to Have Coronavirus Under Control, Until Cases Doubled,” read a headline on the New York Times. When the city was first hit by the pandemic, its efficiency in controlling the spread was lauded as a model response. Now, its cases total to over 8,000, the highest number reported number in Southeast Asia. The number of infections climbed rapidly as the virus reached numerous foreign workers’ dormitories across the state—housing about 300,000 people—which are notoriously overcrowded and ill-equipped. The pandemic has gone on long enough, I think, for all of us to recognise that its effects have carved our social divides deeper than ever before. “The outbreak doesn’t discriminate, but its effects do,” is a sentiment that has been widely spread across social media and news outlets, inviting incisive criticisms on an array of issues, from capitalist policies to eco-activism and celebrity culture. A dominant theme, however, runs through their veins: the far-reaching power of privilege; and how it pervades even the smallest units of our lives. As “social distancing” and “stay home” were made law, it became clear that space is a luxury few share—at least, fewer than we thought. Instructions such as “stay home” and its varieties, writes Jason DeParle for the New York Times, assumes the existence of a safe, stable and controlled environment. DeParle notes that inmates, detained immigrants, homeless families and, I would add, victims of domestic abuse, are some of the discrete groups facing a dilemma amidst such instructions. He asserts: “What they share may be little beyond poverty and one of its overlooked costs: the perils of proximity.”

Close quarter is the very calamity confronting Singapore’s foreign workers community during this outbreak. Contagion hit a record high on 20 April, with over 1,426 confirmed cases, a vast majority of which coming from numerous dormitories across the state. Since early last week, active testing has been carried out since in the dormitories—which might explain the figures—but the City had been glaringly unprepared, which made for a peculiar sight. Immediately, I found myself questioning its renowned vigilance and extraordinary prescience; qualities that I often contrast with my hometown of Jakarta and its outrageously lethargic response to the pandemic. But the dorms had always been “ticking time-bombs”, Sophie Chew writes on Rice Media, and the City had turned a deaf ear to forewarnings from activists and NGOs that went back as far as February. The dorms are overcrowded, she reports: a single dorm can house over 10,000, and up to 20 people are pushed into a space the size of a four-room flat. A resident of S11 Dormitory located in Punggol, one of the first to be gazetted as an isolation site, says he shares the same shower facilities as about 150 others. The dorms are unlivable, Chew says; detailing that they are “notoriously filthy”, and some workers told The Straits Times that toilets were not regularly disinfected. This condition makes the concept of safe distancing “laughable”, writes the NGO Transient Workers Count Too (TWC2) on their website. To Chew, it is clear that Singapore’s “celebrated, ‘gold standard’ response had a citizenship blind spot.”

The blatant ignorance to the livelihood of the migrant populace is inexcusable, but it is hardly a shock for anyone from the outside looking in. The racial divide is patent; and—in the case of foreign workers—the tension is heightened by a system that enables the production of precarity and abets exploitation (Chuanfei Chin from the National University of Singapore wrote a concise paper detailing the network complicit in producing the social vulnerabilities experienced by temporary foreign workers, which you can read here). Yet, when news outlets started reporting on the crisis, they had been either clinical or deeply prejudiced, and the comment section only compounds the horror. These have not only mapped public opinion, but also reiterated the value that is given to the lives of foreign workers, and delineate further their standing in the Singapore society. The lines on this map are both psychological and structural: Yong Han Poh, writing for the Southeast Asia Globe, reminds us that their dormitories are built in isolated areas far from the public view. They are, quite literally, segregated from the wider population. The kind of treatment we afford them, the lines we draw, brings to my mind a passage from Solnit’s essay Crossing Over, where she talks of territories and migration: “The idea of illegal immigrants arises from the idea of the nation as a body whose purity is defiled by foreign bodies, and of its borders as something that can and should be sealed.” The concept, when taken in a literal manner, is eerily familiar: Almost immediately after the outbreak reached the dormitories, Facebook comments became unbearable, with an alarming number of people pointing fingers at the foreign workers’ habits and personal hygiene; insinuating that the contagion rates has more to do with their insanitary culture than the ill-equipped and overcrowded dorms (of course, they would not be the first to be at the receiving end of such narrative, which has shifted throughout history to serve the interests of those in power. Pan Jie at Rice Media offers a succinct chronicle of this.) Solnit calls this the “fantasy of safety”, where “self and the other are distinct and the other can be successfully repelled.” We are seeing, right now, that fantasy wielded by those with power; one they enforce out of suspicion and out of fear of losing security and authority. But all who have been subjugated, too, understand and yearn for this fantasy: To be liberated from the constant invasion of freedom and autonomy.

Image courtesy of Sumita Thiagarajan via Facebook. Taken on Keppel Island.

It is critical to examine, Rebecca Solnit writes, who is meant by “we” in any given place. One way to do this is by looking at the lines drawn by the semantics of names and categories. The term “migrant” has come under scrutiny in recent years: What separates the group—defined as “a person who moves from one place to another, especially in order to find work or better living conditions”—from expats, for instance, could be only a matter of nationality and skin colour. As Indonesian author Intan Paramaditha states in her essay on LitHub: “We can read the map, but the map has read us first.” Further in her essay, she continues to say that these categories determines how one experiences mobility, whether one would “encounter bridges or barriers, hospitality or displacement.” Making the distinction even more severe are neoliberal policies that have turned lives into pawns and commodities and made decent livelihood a due owed and never paid (while “errant employers” is often cited as the reason for foreign workers’ exploitation and abuse, research have shown that the legal framework protecting them, while comprehensive, is flawed). This points to the central criticism against the term “worker”, which, as Yong writes in her essay, reduces them to factors of production and labour units. Recently, online platform Dear.sg, which describes themselves as a “media conglomerate steeped in culture and grounded in locality”, befouled this already murky waters: With an article titled We Need Foreign Workers More Than They Need Us—a headline that might deceive one into thinking it’s an innocent op-ed designed to galvanise empathy by tugging at one’s guilty conscience—they concluded that migrant workers are valuable because they are essential to our material needs. “Construction sites might have to be abandoned for a while and projects will take a longer time to be completed,” it says in one passage. It then implores its readers to “think of your Build-To-Order flats…the new airport terminal, street repairs and maintenance…”, and reminds them that now, “we have to wait even longer.” What is meant by “we” had never been so grossly exclusionary. The article has narrowed migrant workers into tools of prosperity, and never once suggested that they be a beneficiary (they have received a number of backlash on Instagram, and as of yesterday they are still actively deleting comments). At the end, under a heading that says Modern Slavery Or Not (sans question mark), they ask if we should start ringing the alarm on exploitation of cheap labour. Does all this leads to the so-called modern slavery, it asks, grammatical error intact. “Maybe,” it answers, aloof. “Forced contracts and bonds, who knows.”

Evidently, this pandemic is not “the great equaliser”. If anything, it has magnified privilege and heightened insecurities. Solnit offers us hope in what she calls “public love”: collective action; a sense of meaning and purpose that belongs to a community. She refers to the 1960 earthquake of San Francisco, and outlines a shared sentiment of loss among the people, that is “if I lose my home, I’m cast out among those who remain comfortable, but if we all lose our homes in the earthquake, we’re in this together.” Perhaps the nature of this pandemic bears little resemblance to a natural disaster, but we experience collective loss all the same: Much of our freedom and flexibility—to work, travel, or to socialise—have been suspended for the foreseeable future. But they are losses felt more profoundly by vulnerable groups, and let it not be forgotten that they were cast out before any disaster—the precarity of their livelihood a disaster in its own right—and they bear distress many of us are precluded from. These inequalities have been laid bare in the weeks following the outbreak in dormitories, and there had been no shortage of care from the ground: Comedian and YouTuber Preeti Nair ran a fundraising campaign to aid two NGOs, TWC2 and HealthServe, in meeting the urgent needs of migrant workers that have been put under quarantine. As of 21 April, they have raised over S$316,000—more than triple their original goal of S$100,000. There are spreadsheets detailing efforts of different organisations and how we can contribute (Yong included one at the end of her essay, and a local community library, Wares, published a Mutual Aid and Community Solidarity spreadsheet). Many Singaporeans who are able and secure have donated their Solidarity Payment to non-profit organisations working with vulnerable groups. Corporations, too, have started partnering NGOs to raise funds and distribute masks at affected dormitories. It’s not just in Singapore: Worldwide, the pandemic has fostered record numbers of philanthropic donations and vast networks of mutual aid—a new map, if you will, with unmarked territories and nameless seas. There is a growing recognition of mutual dependence, a survey by the New York Times shows, and while there is no guarantee that the shift in moral perspectives will last beyond the crisis, there is hope in knowing that we are re-examining—if not redrafting—the map that we were given.

Yet I still find evidence of a divide: I have heard more and more that we need not need to worry; most of the cases are from the dorms, I hear, there are less in the community, I hear, directly from the official WhatsApp updates, and I recognise once more the gulf that has yet to be bridged. Between the lines, I find the seeds of amnesia, which—Solnit writes in her essay Long Distance—holds us “vulnerable to experiencing the present as inevitable, unchangeable, or just inexplicable.” She talks then of the term “shifting baselines”, coined by marine biologist Daniel Pauly, and stresses the importance of a baseline; a stable point from which we can measure systemic transformation before it was dramatically altered. This pandemic, one can hope, will alter how dormitories are managed and equipped for the better. Beyond this pandemic, Manpower Minister Josephine Teo said in a statement in early April, “there’s no question” that standards in foreign worker dormitories should be raised, and appealed for increased cooperation from employers. Meanwhile, measures taken to manage this crisis—particularly with the issue of overcrowding and hygiene—have been widely criticised; prompting authorities to move residents of the dormitories to vacant Housing Board flats, military camps and floating hotels to reduce crowding. The Prime Minister further addressed these measures in a live address to the nation yesterday—in which he also announced the 4-week extension of the Circuit Breaker—promising stricter safe distancing measures, increased on-site medical resources, closer monitoring of older workers, and distribution of pre-dawn and break fast meals for Muslim workers who will start fasting on Friday. “The clusters in the dorms have remained largely contained,” he says, and pledges their best effort to keep it that way. When this crisis is over, I tell myself, we must not forget the baseline of their predicament, or be too quick to acquit those in power from any wrongdoing—if only to preserve a benchmark of assessment. Without a recollection of the past, Solnit warns us, change becomes imperceptible, and we might slip to “…mistake today’s peculiarities for eternal verities.” Nevertheless, the Prime Minister sounded assured. He even wore a blue shirt—that must have meant something. I, for one, am hopeful, as I always try to be. There’s still much reason to be.

***

I stopped at the traffic light at the intersection of Dorset and Kent. I glanced at the street sign, green as they’ll ever be. Solnit writes: “Pity the land that thinks it needs a hero, or doesn’t know it has lots and what they look like.” Indeed, we do not know it. I wondered then if the crisp white paint will ever spell a different name. For all the transformations construction workers have made to our built environment, will there ever be a monument in their name, like the kind we have bestowed our tycoons and presidents and—oh God, I groaned as I realised this—counties of former occupants? In a few weeks’ time, this intersection will be vacant once more; the deafening drill and temporary fences suddenly vanishing from sight. Their mark will go undetectable and nameless; swallowed whole by the scorching sun and the picturesque imagination of the Dorset and Kent of another continent. The light turned green. As I crossed the street, I remember Solnit saying that the truest lines on this map are only those between land and water. “The other lines on the map are arbitrary,” she says, they have changed many times and will change again. One can hope.

Whose Story Is This? Old Conflicts, New Chapters, Rebecca Solnit, 2019.

POSTSCRIPT

As I am finishing this essay, I wonder how big of a role I play in this equation, and if I tip the scale further towards inequality. I realise how small we all are; how powerless we might all be without the aid of top-down political action. I am not under the delusion that individual responsibility counts a great deal in this narrative (David Wallace-Wells calls accusations of personal responsibility a “weaponised red herring”), but I also refuse to trivialise the weight of our own actions (the great Gloria Steinem reminds us that “a movement is only people moving”). This being so, you will find below some spreadsheets and relevant, verified fundraising campaigns where you can extend your care. Every dollar counts, and every hand have the power to soothe.

Fundraising Campaigns

Preetipls x UTOPIA for Migrant Workers NGOs

Support migrant workers through Covid-19 and beyond, a campaign by Humanitarian Organisation for Migration Economics (HOME)

Vulnerable Women’s Fund by AWARE

Donate Your Solidarity Payment. Funds will be channelled to Boys’ Town, Hagar Singapore, Singapore Red Cross, AWARE and HOME

Entrepreneur First supports The Food Bank - Feed the City #Covid-19. Funds will be channelled to the Food Bank. You can also donate food to Food Bank Boxes available island-wide.

Spreadsheets

Mutual Aid and Community Solidarity – Coordination by Wares Infoshop Library

COVID-19 | Needs in the migrant community as included in Yong Han Poh’s essay

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

What Are Your Homecare Options in Today's Society?

There are actually various choices for treatment in the property today. It utilized to become that any person not able to maintain on their own will be actually put in a domestic healthcare facility or even resource, for regular like be actually on call to all of them all the time. Nowadays, there are actually a number of Homecare alternatives to pick from.

For those who perform certainly not require clinical interest and care all the time, a part-time home care alternative is actually optimal. Using this choice, a health professional is actually chosen to explore for a couple of hrs each early morning, help along with regular duties, and brush. The perk to this homecare choice is that the caretaker deals with what needs to have to become carried out, leaving behind the person to his personal regimen and personal privacy for the rest of the time. This enables the person to experience additional totally free and also private to set about his personal everyday schedules without continuous aid or even input coming from any person else.

For those that are actually much less individual as well as need to have extra considerable treatment throughout the time, there are actually homecare possibilities where nurse practitioners are actually chosen to function fulltime times. These caretakers are actually for those demanding a lot more continual treatment and also support throughout the time. They might require routine does of a drug, critical examinations, transit and/or aid with motion, and various other day-to-day regular duties. Through this homecare alternative, the nurse practitioner will leave behind for the evening and come back the upcoming early morning, leaving behind the individual his evenings and nights to themself. This choice permits the individual to reside in his very own residence and still obtain a handful of alone-time hours at nights, evenings, and mornings, one thing they would certainly not have actually privy to in a non-commercial establishment.

For people that are actually fully dependent on their caretakers, the ideal homecare alternative would certainly be actually a 24 Hour Homecare and/or Live-in Nurse Companion. These nurse practitioners stay within their individual residence and exist all the time to aid along with each of their necessities, health care, etc. This choice still brings the perk of permitting the client to continue to be at his personal house, which is actually truly the offer buster when needing to have all the time treatment and the absolute most crucial opportunity to preserve.

Today, homecare choices are actually lots of. This is actually therefore valuable, certainly not just for the people that call for some sort of support along with their day-to-day residing, yet to the loved ones that currently perform certainly not need to create the tough, however at times essential selection to put an enjoyed one in a non-commercial location. That is actually a selection that many individuals have a hard time with as their liked ones shed their self-reliance and call for some support along with their day-to-day lifestyle schedules and tasks. What leads to the absolute most heartache concerning creating that inescapable selection is actually having actually the really loved one cleared away from their treasured property and the reduction of their personal privacy and flexibility. Through possessing the homecare possibilities our team possesses today, those are actually no more issues.

What You Need to Acknowledge Before Hiring a Homecare Agency

When selecting a home care organization, there are actually numerous points to look at. Coming from understanding what concerns to inquire to discover the particular caretaker that will be actually taking care of your aged moms and dad, working with the correct home care organization includes some analysis and investigation. Take care certainly not to become waned into a misleading complacency when it relates to history inspections, the skills of the caretaker, and so on. Given that a caretaker happens to come from a company carries out certainly does not imply he or she is actually educated and trustworthy.

Depending on a research study executed due to the American Geriatrics Society:

Only 55 percent of organizations really carry out a history inspection

Only a 3rd of companies do medication tests-though all professed to

Only a 3rd examined their health professionals for competency-though they all declared to

Supervision was actually rare-ranging coming from none to when a full week

By being actually an informed individual, you may guarantee that the homecare company you tap the services of is trustworthy and secures your enjoyed one mentally, literally, and psychologically. There are actually credible companies that carry out carry out typical medication exams, proficiency tests, and also history examinations, and also these are actually the firms you intend to look into better. Furthermore, there are actually traits you need to take a look at to observe exactly how extensive the firm is actually and also the amount of problem it takes into locating the ideal health professional for your enjoyed ones.

Online reputation and also History

Being actually a big firm performs certainly not always imply that the provider is actually reputable-it might merely imply it operates in quantity. As an alternative, try to find a homecare organization that has actually stayed in business enough time to develop a tough track record in the area. Receive recommendations coming from the firm and talk to doctors and people you leave for suggestions they eat homecare firms in your metropolitan area.

Get the best homecare service, visit: www.seniorstrong.org

Sponsoring Practices

Given that you are actually employing a company performs certainly does not imply it possesses a really good process when it arrives to sponsor, merely. Talk to the homecare agent you talk to about just how the provider discovers its own applicants-such as paper advertising campaigns, staffing companies, and so on. Make inquiries concerning the home care organization's hiring demands through talking to:

What lowest education and learning serves?

What previous knowledge proves out?

How numerous years must a caretaker invite previous jobs to train?

Does the caretaker need to have a permit or even qualification?

Prior to you choose a home care company, ensure the firm you are actually looking at displays screens its own applicants. Does it carry out unlawful history checks-both federal government and also condition? Does it execute a medicine display?

At the moment chosen, exactly how performs the homecare company calculate if the caretaker can perform the tasks she or he will be conducting? Performs she or he possess constant oversight and also instruction? Many reliable firms are going to give hands-on instruction, featuring CPR and also emergency treatment.

Create certain the company you work with is actually guaranteed and also bound. To come to have adhered, the firm must supply history inspections, medicine display leads, learning past History, as well as fulfill various other criteria to acquire its own adhered certification-thus showing the provider is actually professional.

Client Satisfaction

When tapping the services of a home care organization, you really want to take pleasure in the adventure. You wish to count on the firm, particularly considering that its own health professionals will definitely be actually entering your house. Be sure the organization you work with permits you to examine several caretakers as well as provides you the choice to shift health professionals if you identify they are actually certainly not a great suitable for your liked one. Very most significantly, are sure the firm appoints one irreversible caretaker to your liked one to ensure that he possesses a friend as well as a lasting connection along with them rather than a blend of complete strangers every week.

youtube

From understanding what concerns to inquire to know regarding the details health professional that will definitely be actually looking after for your aged moms and dad, employing the best homecare firm entails some investigation and investigation. Through being actually a taught buyer, you can easily guarantee that the homecare organization you work with is actually respectable and defends your enjoyed one mentally, literally, and psychologically. There are actually reliable organizations that carry out execute basic medical exams, expert assessments, and also history examinations, and also these are actually the firms you yearn for to look into better. Receive endorsements coming from the firm and talk to medical doctors and various other folks you count on for suggestions they possess for homecare organizations in your area.

As soon as worked with, just how does the homecare organization identify if the health professional is actually qualified for the responsibilities he or she will be carrying out?

🎧 Listen to our podcast: https://pod.co/podcastlive/4-things-to-look-for-in-bath-chairs-for-elderly-family-members

source https://seniorstrong.blogspot.com/2021/04/what-are-your-homecare-options-in.html

0 notes

Video

youtube

pay someone to write my paper

About me

How To Write An Essay

How To Write An Essay However, If you think that essays usually are not fully ready, merely request for revisions. After you've accepted the essays, the fee for the author shall be launched. To study more about it, simply learn the Terms of Use section. Apart from being subject-matter consultants, in addition they possess an exemplary command over the English language. Essay writing could seem straightforward on the floor, but many uncover it isn’t all the time this simple. Many folks just can’t address these types of assignments just because they've poor writing expertise or they can’t express their ideas on the essay very well. Most choose to come back to PapersOwlwith requests of “please, write my essay for me”, as a result of they either can’t write it on their own or they’re just too bogged down with other assignments. If they are precisely what you needed, simply approve of them. Contrary to what some consider, we continued to work . Several academics took the time to achieve out to our students to examine on their well being even though so a lot of our top leaders have yet to verify on ours. Outline any extenuating circumstances associated to Covid-19. Some students may find themselves crammed in a small apartment or residence with their entire family. That’s how I got here to Mary Wollstonecraft, by reading about her life, and via the letters she wrote when traveling via Scandinavia. I tapped into her life, and Mary Shelley’s, and I started to make connections. I realized that necessary dates from their lives occurred kind of 2 hundred years before events in my family life. Any two well-educated native english speakers, tutorial literacy facilitator and self-discipline specialist a relationship between fyc and literature. Many folks tend to need to develop the adolescent with opportunities for lecturer-scholar interac- tion in the subject. A pal in Montreal sent me this unimaginable brief essay by the French thinker Catherine Malabou. She was stranded in Irvine, California and wrote about Rousseau’s confinement during a plague, in addition to her own confinement. She talks about how Rousseau had a choice between quarantining with others on a ship or quarantining alone in less than best situations. This disruptive surroundings might need made it difficult for the student to concentrate on their lessons. Some college students could be required to look after youthful siblings during the day. We have a staff of over 500 top-rated writers & editors. We only hire educational writers & editors with years of expertise. In fact, topic and that it is not for essay do somebody can my me clear to us to teach towards the mean, which could make a abstract, and h desktop publishing. In two out of rhetoric, a student s text they produce. He elected to be confined to a hospital by himself, with nothing however his trunk and clothing. So, he made a bed out of his jacket and turned his trunk right into a writing desk, transforming his isolation and meager means into a possibility to wholly dedicate himself to writing. I’m one of those people who has at all times learn biographies, from the time I was an adolescent. That realization enabled my own writing; it grew to become a way to connect personal tales with different literary histories and a feminist historical past of social justice. It’s not straightforward to write down about your self; I have the impulse, but I want permission, and I discover it through connecting to different lives. Since 1947, the Voice of Democracy has been the VFW’s premier scholarship program. Each year, nearly 57,000 high school college students compete for greater than $2 million in scholarships and incentives. Students compete by writing and recording an audio essay on an annual patriotic theme. For what looks like eternally now, Nevada teachers have been conditioned to persist under grueling and inconceivable circumstances. It’s the primary cause why, regardless of our 50th ranking in funding and support, Nevada is 35th in educational achievement. I am a product of the Washoe County School System. Despite our fear, we prepped and planned and waited to welcome our students. We did the same when components of our world literally started burning and the district and school board had been abruptly deeply concerned concerning the state of the air we breathe.

0 notes

Text

The United States is Losing Latin America to China