#shonen sunday comics

Text

Yofukashi no Uta Vol.18

63 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Case Closed (Vol. 1)" by Gosho Aoyama

#apparently folks dont know that detective conan named himself after ACD#sherlock holmes#comics#case closed#detective conan#great detective conan#名探偵コナン#Meitantei Konan#manga#comic book#manga art#shonen#shonen manga#gosho aoyama#kudo shinichi#shinichi kudo#jimmy kudo#Conan Edogawa#shonen sunday

238 notes

·

View notes

Text

Shōnen Big Comic (少年ビッグコミック) / Shōgakukan (小学館) / 27th Sep 1985 issue

#vintage manga#shonen manga#retro shonen#80s manga#big comic#shonen sunday#shogakukan#少年ビッグコミック#小学館#issue month: september

83 notes

·

View notes

Text

Yuta and Mana:)

Yuta and Mana do have height difference. It's no random that when they're walking side by side, Mana always walks on the railings, she likes to be on Top,to be taller than him. Due to Mana is for Power.

#Takahashi Rumiko#高橋 留美子#人魚シリーズ#Mermaid Saga manga#Horror fantasy#Supernatural#historical drama#Romance#Strong female lead#Rumicworld#Rumic couple#Shōnen Sunday Comics Special#Shonen manga#少年漫画#Shogakukan manga#株式会社小学館#Sunday Shonan Zokan#週刊少年サンデーS#Weekly Shōnen Sunday#週刊少年サンデー#Mermaid Saga Yuta and Mana#湧太#真魚#Immortality

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

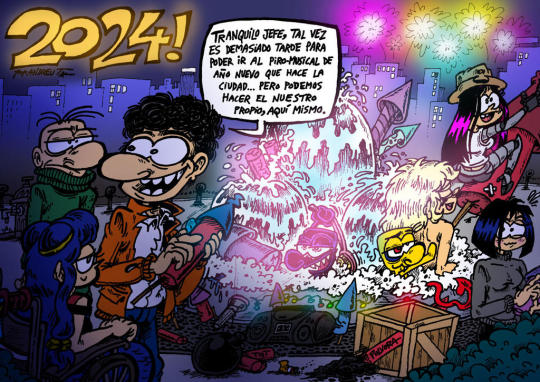

art by ANDREU-T

#Shogakukan#Shueisha#Shonen Sunday#Business Jump#Ranma 1/2#Gunnm#-(Japanese%3A#Battle Angel Alita#Alita: Battle Angel#Mort & Phil#Mort and Phil#Mortadelo y Filemón#Mortadelo y Filemon#Mortadelo and Filemón#Mortadelo and Filemon#Clever & Smart#Clever and Smart#retro#vintage#european comics

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

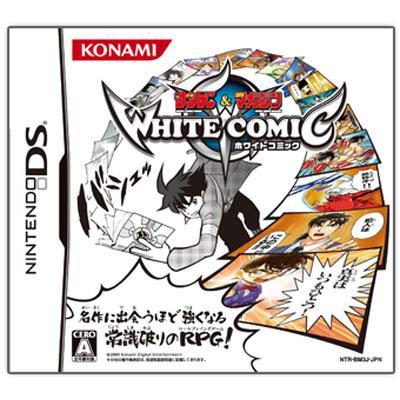

I want to play this game so badly that it's not a want, it's a NEED.

#a crossover game between shonen sunday and shonen magazine#which features almost all the series im so normal over????#this was made just for me#like uy ranma inuyasha detco gsm touch kindaichi and more??#and with like atleast a good number of characters from each??#hopefully i get my hands on this one day#and i would love to see a translated version as well!!#weekly shonen sunday#shonen magazine#shonen sunday & shonen magazine white comic#video games#wishlist#I NEED THIS SO BADLY

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

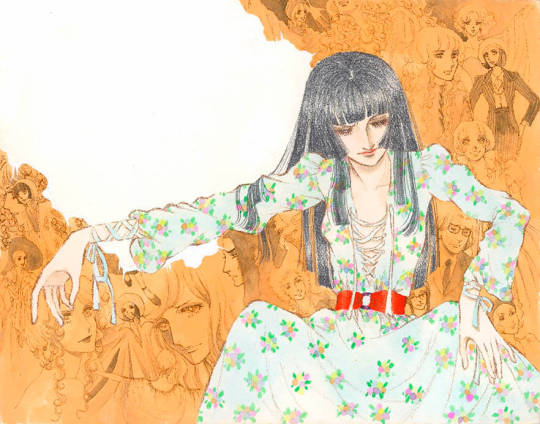

Orochi (おろち)

Written and illustrated by Kazuo Umezu in Weekly Shōnen Sunday from June 1969 to August 1970. Orochi, a perpetually young-looking woman with mysterious abilities who takes it upon herself to observe the lives of different individuals who catch her fancy, from afar. The story contains several varying elements such as paranormal and psychological themes.

The art is eerie & dark. It literally made me shiver & I don’t like that feeling, I couldn’t even finished reading it. I don’t really read horror manga like that, I would like to sleep at night…The cover art is amazing, it really pulls you in. Also, this is a hardcover edition & it’s beautiful. I want some shojo series like this, that would be nice. If you like horror/supernatural manga then this is for you.

Thank you @vizmediaofficial for sending this manga my way. I was not expecting this, made my heart jump.

✨Insta📸 & Tiktok @luziiannne ✨

#orochi#manga#anime#shonen sunday#shonenjump#kazuo umezu#horror manga#supernatural#booklr#漫画#manga review#vizmedia#comic books#graphic novel#books and literature#books#bibliophile#manga books#horror series#comics#おろち#orochi manga

8 notes

·

View notes

Link

Following the success of the Shonen Jump app, which launched four years ago, Viz Media has now launched a new general Viz Manga app, featuring access to their full VIZ MANGA (note: not including the Shonen Jump imprint) digital library of over 10,000 chapters, including free simulpub chapters every week. This includes title from their Shojo Beat imprint, titles originally serialized in Shonen Sunday, and many more.

You can access chapters through the website or the VIZ MANGA app, with a monthly subscription costing $1.99 per month. Subscriptions can only be purchased on the app, which is available on Apple and Google Play. Currently, the service is only available to those in the U.S. and Canada.

Several titles do not have all of their chapters available, but will be available soon. These include: Komi Can’t Communicate, Zom 100: Bucket List of the Dead, Fly Me to the Moon, Call of the Night, Case Closed (Detective Conan), Queen’s Quality, Sleepy Princess in the Demon Castle, Mao, Yashahime: Princess Half-Demon, Insomniacs After School, Frieren: Beyond Journey’s End, Black Lagoon, How Do We Relationship?, The King’s Beast, Persona 5.

In addition, due to certain restrictions on mature content for app stores, several titles and chapters containing such are not available to be read on the VIZ MANGA app and instead are only available on the website.

#viz media#manga#shonen sunday#shojo beat#junji ito#komi-san#komi can't communicate#rumiko takahashi#komi san#comics#comic books#shogakukan

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

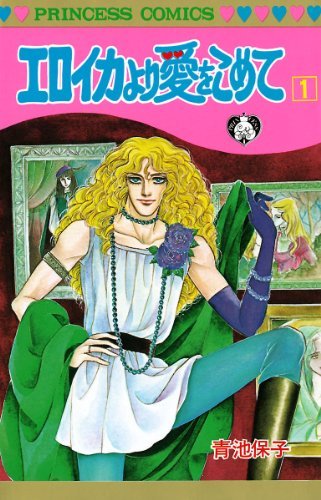

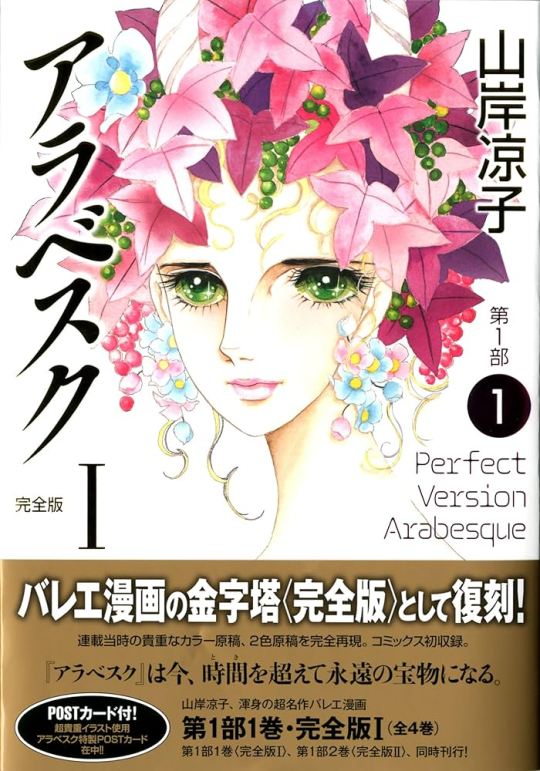

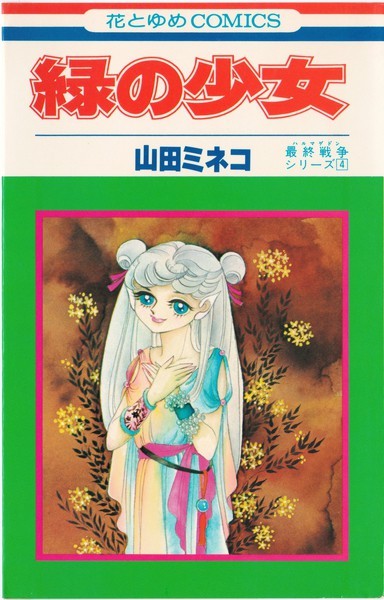

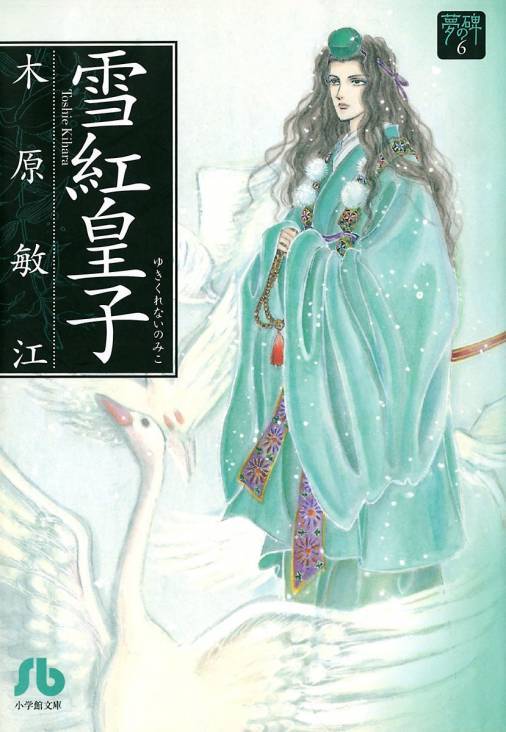

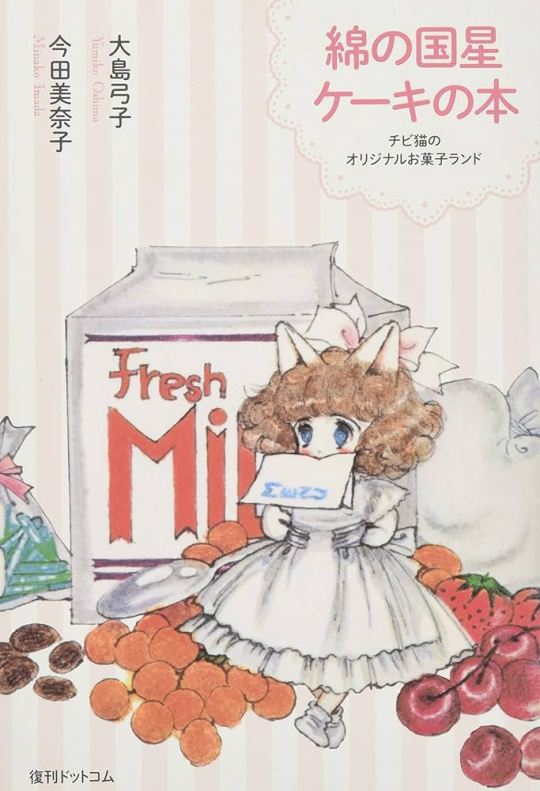

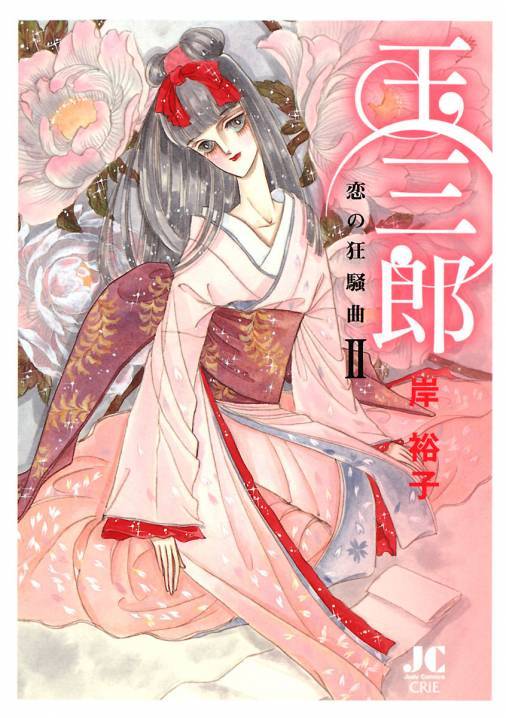

Shoujo Manga's Golden Decade (Part 2)

Shoujo manga, comics for girls, played a pivotal role in shaping Japanese girls’ culture, and its dynamic evolution mirrors the prevailing trends and aspirations of the era. For many, this genre peaked in the 1970s. But why?

Part 1

The Year of 24 Group

Some of the best-selling work by the Year 24 Artists (l-to-r): Yasuko Aoike's "From Eroica with Love," Ryoko Yamagishi's "Arabesque," Mineko Yamada's "Minori no Shoujo," Toshie Kihara's "Yomie no Ishibume," Yumiko Oshima's "The Star of Cottonland," Yuuko Kishi's "Tamasaburo."

Back in the early '70s, there was the prevailing notion that manga was for young kids. Despite the variety in themes, big magazines like Margaret, Shoujo Club, Nakayoshi, and Ribon were theoretically aimed at elementary school-aged girls.

In practice, the reality was more nuanced. Due to being published in Weekly Margaret, "The Rose of Versailles" was for kids. And it did very well with them. Yet, its revolutionary romance also appealed to broader audiences, exemplifying the crossover potential of shoujo manga. It was the title that opened the door for what is known as "the golden age of shoujo," which was further cemented by several other groundbreaking hits.

These hits widened the shoujo manga field, and soon, other editorial houses also wanted to cash in. Shogakukan, which published the powerful Weekly Shonen Sunday, entered the shoujo market in the late '60s. Shueisha and Shogakukan also partnered to form a keiretsu and open the Hakusensha publisher which deals mostly with shoujo manga.

That is the context in which a batch of artists known as "The Magnificent 24 Group" rose. And they were another key reason as to why '70s shoujo made such a mark. These manga-kas introduced themes such as sci-fi and homosexuality to the segment, revolutionized its art, further explored historical and terror narratives, and generally broke barriers of what was possible in shoujo manga. Their work was intellectually challenging, philosophical, and, above all, fundamental for male manga critics and connoisseurs to finally take shoujo seriously.

The Year 24 Group refers to the fact most artists were born around 1949, which is known as the year 24 of the Showa era in the Japanese calendar. These women came of age during the time artists like Hideko Mizuno were debuting and doing revolutionary work in the shoujo field, and they were eager to follow their lead. The success of unorthodox hits like "The Rose of Versailles" and the emergence of new magazines enabled them to be bold.

The two artists who led the movement are Moto Hagio and Keiko Takemiya. Their shared house in Tokyo, known as the Oizumi Salon, became a gathering place for several young artists keen on breaking new grounds for shoujo manga-kas. These women became the Year 24 group. But there were other two people, besides the artists themselves, who were just as crucial for the existence of the movement.

Firstly, there was Junya Yamamoto. Yamamoto was a young male editor at Shogakukan who had risen through the ranks of the successful Shonen Sunday weekly manga magazine. Noticing they were lagging behind Shueisha and Kodansha in the manga segment for their lack of a robust shoujo presence, the editorial house appointed Yamamoto to launch Shoujo Comic (known as Sho-Comi) in 1968 and Bessatsu Shoujo Comic (known as Betsucomi) in 1970. However, he quickly ran into an issue: most successful shoujo artists already had exclusive contracts with the competing houses, and aspiring names were vying for positions at the already established magazines.

In 1969, the "God of manga," Osamu Tezuka, introduced Yamamoto to Keiko Takemiya, then a university student living in Tokushima City. Takemiya had spent her school years dreaming of becoming a manga-ka and participated extensively in the readers' corner section of COM. COM was an avant-garde manga magazine Tezuka founded to nourish young talents and publish stories without the typical restraints of more commercial shoujo and shonen publications. In her first year of college, Takemiya won a Shueisha's Weekly Margaret newcomer competition and had a work published in the magazine. Still, she was persuaded by her parents to focus on her studies instead and to leave manga as a side hobby.

Yamamoto, in turn, was impressed with her talent and convinced her to chase her dreams. Quickly, she found work in all three publishers and started simultaneously publishing in Kodansha, Shueisha, and Shogakukan's shoujo titles.

Meanwhile, Moto Hagio also grew up enamored with the manga world. During her college years, she had a work selected by Shueisha's Bessatsu Margaret (Betsuma) through a competition, but she could not find a fixed slot in the magazine. Then, she got introduced to Kodansha's Nakayoshi editors, who were impressed by her talent. While she did start publishing short stories there, editors rejected most of her submitted work as they did not fit the magazine's mold. One day, an editor introduced her to Takemiya, who, overworked while working for several magazines, was in dire need of an assistant. The two hit off, and Takemiya, who until then had her permanent residence in far away Tokuma City but was planning a move to Tokyo, proposed they both live together. She also decided to introduce Hagio to risk-taker editor Yamamoto, who, impressed by her talent, encouraged her to pursue her path instead of trying to fit into the expected shoujo template.

Then there was Norie Masuyama, who first became acquainted with Moto Hagio before becoming Takemiya's manager. Hagio was from Fukuoka, while Masuyama was from Tokyo, but due to their similar interests, they became penpals. When Hagio first moved to Tokyo, Masuyama hosted her in her home in Oizumi. Eventually, Hagio introduced Masuyama to Takemiya, and the three of them became close. Because both were artists from outside of Tokyo, Masuyama suggested Keiko and Moto should live together, and she was the one who alerted them of a house in her Oizumi neighborhood being up for rent.

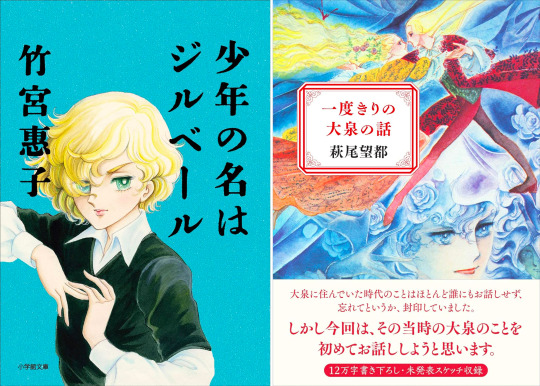

Keiko Takemiya and Moto Hagio, estranged since the late '70s, revealed details of their feud in autobiographic books: Takemiya's "Shonen no na wa Gilbert" (2019) and Hagio's "Ichidou kiri no Oizumi no Hanashi" (2021). The dispute, stemming from Takemiya accusing Hagio of plagiarism, was fueled by Takemiya's jealousy during a challenging creative and personal period. While Takemiya appears self-aware and analytical in her account, Hagio's book indicates she hasn't forgiven Keiko, revealing unresolved feelings. The publications triggered intense online debates.

Masuyama came from a sophisticated family that was very involved in arts and, from a young age, got familiarized with the world of music, literature, and movies. Her refined taste impressed Hagio and Takemiya. At a time when Japanese girls dreamed of Europe, Masuyama actually had friends living there and was up-to-date on the latest European trends. She also had a lot of knowledge of European cinema and literature.

As their rented house was old and rusty, Hagio and Takemiya started spending a lot of time at Masuayama's house across the street. She introduced them to films, songs, books, and paintings. It was Masuyama's taste -- including her interest in movies and books depicting gay romance and her desire for girls' comics to have bolder and riskier themes -- that helped to instill a passion in both artists to go further than the safe cliches usually depicted in shoujo works.

In 1970, editor Yamamoto convinced Takemiya to sign an exclusive contract with Shogakukan. The following year, Hagio also started publishing for Sho-comi and Betsucomi. Their work would attract a loyal fanbase, and aspiring manga-ka would flood their mailboxes. So Takemiya made a decision: to select female artists around her and Hagio's age to mentor and train at their shared home. Thus, the Oizumi Salon was born.

Despite attracting attention, Takemiya and Hagio's works were not always popular. In fact, they'd often rank last in readers' popularity polls, which tend to be all-deciding in manga magazines. But they persevered, and Yamamoto trusted them.

Keiko Takemiya aimed to establish herself with a top-rated series through "Pharaoh no Haka" (left) in order to garner the necessary respect from editors to write the series she wanted, "Kaze to ki no uta" (right). Despite her resolute efforts, "Pharaoh no Haka" never secured the top spot in Sho-comi's readers' poll, peaking at #2. Nevertheless, the series succeeded in elevating her fame and earning her the respect she sought.

In 1972, Hagio had an idea for a serial focused on a male European vampire. However, as she wasn't a famous artist, Yamamoto only allowed her to publish one-shots. So she came up with a plan: to write three interconnected standalone stories. To circumvent another restraint - shoujo editors' avoidance of male leads - she put the first story focus on Marybelle, Edgar's sister. Once Yamamoto realized what Hagio was doing, he was amused and allowed her to continue. And so, "The Poe Clan" series began. In 1974, Shogakukan finally started publishing their shoujo titles in compiled paperback format. In another proof of trust, Yamamoto chose Hagio's "The Poe Clan" as the first title of the Flower Comics imprint.

To everybody's surprise, "The Poe's Clan," in paperback format, was a groundbreaking success, almost instantaneously selling out its initial printing. At the time, Hagio had just started a new serialization, "The Heart of Thomas," a tragic gay love story set in an all-boys German school. As usual for her, the story wasn't all that popular with Sho-Comi's readership, and its lackluster results in the reader's poll almost got the series discontinued. But the notable success of "The Poe's Clan" tankobon assured editors, who allowed Hagio to continue the series. "The Heart of Thomas" went on to become another best-seller and a seminal shoujo title. It also attracted critical acclaim and a loyal fanbase to Moto Hagio, which in turn helped put the Year 24 artists -- who were pretty good at self-promotion -- in the spotlight.

Hagio, Takemiya, and several other "Year 24" authors drifted between being popular and underground. They had a sizable, loyal fanbase that followed them and turned several of their works into best-sellers. On the other hand, by finding a way around the usual shoujo traditions, they weren't particularly popular with the average shoujo reader, ordinary young girls across the country.

Their peculiar position forced them to be clever, so they could fulfill their creative desires as well as their editors' expectations, who were there to make sure the stories published were satisfying to the core readership. Takemiya wrote "Pharaoh no Haka," an Egypt-set romantic adventure, to be well-accepted so that she could then dedicate herself to doing what she truly wanted in "Kaze to Ki no Uta," a gay love story set in a 19th Century French boarding school.

Initially overlooked in popular shoujo magazines, Moto Hagio gained success with "The Poe Clan" in compiled format, launching Shogakukan's Flower Comics imprint. Over time, she became a highly respected manga artist, the only manga-ka alongside legendary filmmaker Hayao Miyazaki to receive a Person of Cultural Merit recognition. In 2016, marking 40 years of the conclusion of her first hit, she released a new "The Poe Clan" chapter in Flower magazine, selling out the increased print run of 50,000 copies in a day. This success marked a significant shift for Hagio, who, despite not being a major magazine seller in earlier years, became a valuable asset to the struggling publishing industry. Following the one-shot, she released three more chapters and, in 2022, began a new sequel series.

Besides Takemiya and Hagio, several other notable shoujo artists who went on to become huge names used to frequent the Oizumi Salon and were part of the "Year 24 group." In the early '70s, most published their work on Shogakukan's titles, which had a "free policy" on storytelling compared to Margaret, Shoujo Friend, Nakayoshi, and Ribon. Then, as Shogakukan started being more strict to properly compete with the market leaders, several moved to newly launched Hakusensha titles Hana to Yume and LaLa. Influential names that were part of the movement included Yumiko Oshima, Yasuko Aoike, and Ryoko Yamagashi, among several others.

Despite their unorthodox preferences, they weren't necessarily trying to rebel against the system, they simply wanted to put out good quality work they believed in. Like other Japanese girls from that era, they were fascinated by Europe, and plenty of their stories took place on the continent. In 1972, Hagio, Takemiya, Yamagishi, and Masuyama made a 45-day trip to Europe, visiting the Soviet Republic, France, and several other countries, which had a profound impact on them. Still, their narratives were widely innovative. They often had male leads, introduced sci-fi, "boys' love," and other bolder genres to shoujo manga, and contributed to the evolution of shoujo illustration. Above all, this group of artists was the one who made clear to naysayers, once and for all, that shoujo manga is indeed an art form.

But while their influence in manga history is undisputed, other significant -- and much more commercial -- manga movements also shook the shoujo manga world during that decade.

A Need for Drama

When talking about '70s shoujo manga, it's common for minds to drift directly to iconic series from that time, like "Candy Candy" and "Rose of Versailles." But, unlike in present times, in that decade, the manga industry's focus wasn't on successful, long-running series but on the artists themselves.

As opposed to the struggling publishing marketing of today, major shoujo manga magazines all sold over 1 million copies during that decade. Manga in tankobon (standalone paperback) format was turning into a money-maker field, but being able to sell paperback was very much secondary compared to being a name capable of selling magazines. Keiko Takemiya and Moto Hagio, from the Amazing Year 24 Group, would go on to become household names and had best-selling series, but, at the time, they couldn't compete with the actual shoujo manga superstars who were the signboard artists of the Kodansha and Shueisha's shoujo titles, the ones who actually moved publications. These artists' work was the most significant indicator of what the mainstream readers wanted and aspired to back then.

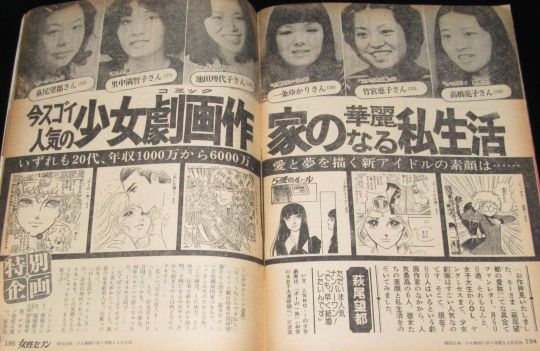

In a December/1975 issue, weekly Josei Seven spotlights the new generation of superstar shoujo manga artists: (l-to-r) Moto Hagio, Machiko Satonaka, Ryoko Ikeda, Yukari Ichijo, Keiko Takemiya, and Ryoko Takahashi. While contemporary manga-kas are highly discreet about their lives and do not even tend to show their faces, in the '70s, they were treated like superstars, and, in the article, the manga-kas openly discuss their love life and details of their high incomes, including how much they had in the bank and how much they spent on rent and daily utilities.

For Kodansha, the top shoujo artist was definitely Machiko Satonaka, who won the Best New Artist competition in 1964, when she was still a freshman in high school. There have been several high-schoolers making their debut in the industry throughout the decades, but, as the first, Satonaka caused a media frenzy. Her ascent gave confidence to countless other young women -- from "Glass Mask"'s Suzue Michi to Keiko Takemiya (who also won a smaller prize in the same competition) -- to pursue their manga careers.

The attention surrounding Satonaka, who went on to become a public personality with TV hosting gigs and other appearances, is another interesting, nostalgic phenomenon. In the past, it was common for manga superstars to have a strong media presence. Nowadays, the norm is the complete opposite: for manga-kas to be highly private, no matter how famous their work is.

In any case, Satonaka quickly proved herself to be more than a sensational news story as she created extremely popular mangas for Kodansha shoujo titles like Shoujo Friend and Nakayoshi. Her style, widely accepted by readers, became symbolical of the story-telling the '70s girls craved: extremely dramatic with emotionally driven plots and lots of bombastic twists and developments.

In his book on subcultures and otaku culture, sociologist Shinji Miyadai notes that '70s shoujo manga can be divided into very few categories. There is the category the Year 24 artists dominated -- which he defines as the "Moto Hagio domain" -- of works with a lot of artistic value, up-to-par with literature. And then there's the far more commercially viable "Satonaka domain," which represented the mainstream taste.

In the "Satonaka category," the artist depicts a stormy life story as a proxy experience for the readers. Of course, there are universal elements of love, friendship, and insecurity that girls can directly relate to. Still, these stories provide adventures that readers could never experience in the real world.

These facets of the "Satonaka domain" are present in almost all the best-selling, mainstream shoujo series of the '70s, like the revolutionary historical romance of "The Rose of Versailles," the dramatic rags-to-riches story of the beautiful orphan in "Candy Candy," and the rise of an ordinary girl to the top of the sports elite in "Ace wo Nerae." In all of these titles, you'll also spot other defining characteristics of '70s shoujo: the death of beloved characters and beloved female characters with voluminous blonde hairs and huge, sparkling eyes (a legacy of Macoto Takahashi, the illustrator who, throughout the '50s, created the art that directly influenced subsequent shoujo history).

Yukari Ichijo was the most prominent Ribon signboard artist throughout the '70s, creating popular mangas like "Suna no Shiro" (left) and "Designer (right). Young girls across the country adored her work despite the adult drama in it.

Since these stories are extraordinary and dream-like, many of them use Europe or the US as their setting, another reflection of the times when Japanese youth dreamed with the West.

While Satonaka was Kodansha's star, Shueisha also had its top shoujo artists. For Margaret, it was Ryoko Ikeda who kept creating memorable dramatic manga after the conclusion of "The Rose of Versailles." Other classic '70s dramatic works published in the weekly included Kyoko Ariyoshi's ballet drama "Swan." Meanwhile, over at Ribon, no one shone brighter than Yukari Ichijo. Ichijo's works, which young girls across Japan devoured, contained a lot of adult drama with adult characters. Her 1974 manga, "Love Game," had a bed scene. One of her most celebrated works of the decade, "Suna no Shiro" (Sand Castle), dealt with incest. While Ichijo is the one who stood the test of time, another artist who also enjoyed great popularity in Ribon following this formula was Kei Nogami.

These mangas served as an escape for girls, who left their ordinary school life behind for a few hours to embark on extraordinary adventures. In contrast, one of the main genres in contemporary shoujo is unassuming, everyday high school romance. How could the shoujo segment go through such a drastic transformation? The reasons for that also dates back to the 1970s.

Part 3

#shoujo manga#vintage shoujo#otometique#yumiko oshima#keiko takemiya#yumiko tabuchi#hideko tachikake#machiko satonaka#yukari ichijo#ribon#1970s japan#1970s#year 24 group#moto hagio#vintage manga

38 notes

·

View notes

Photo

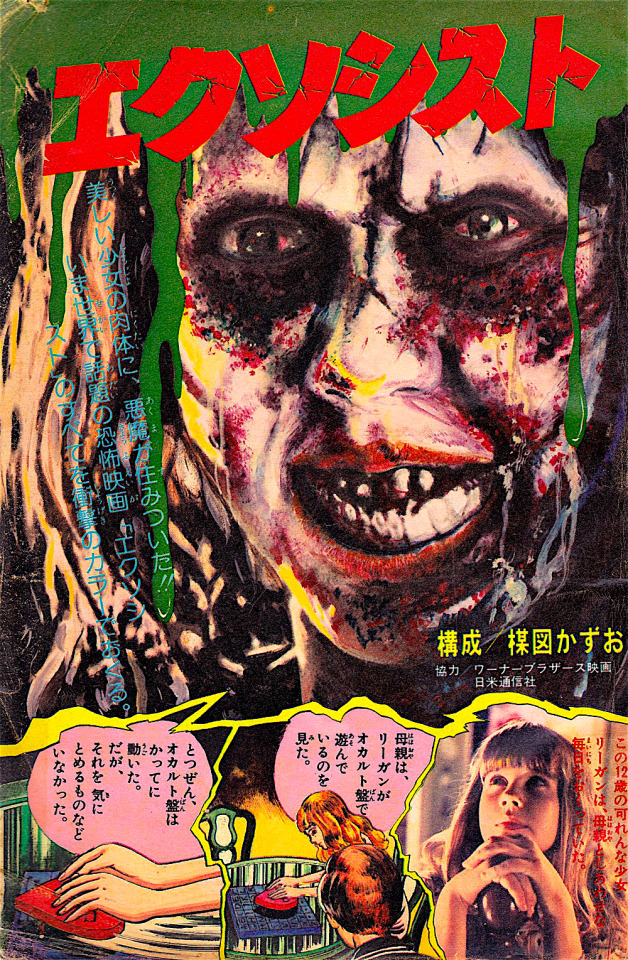

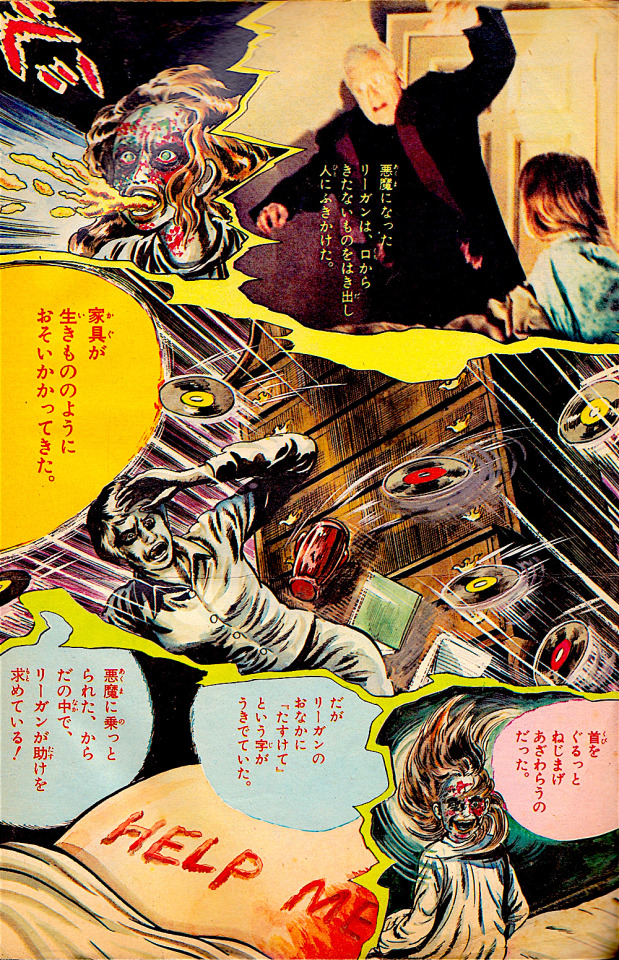

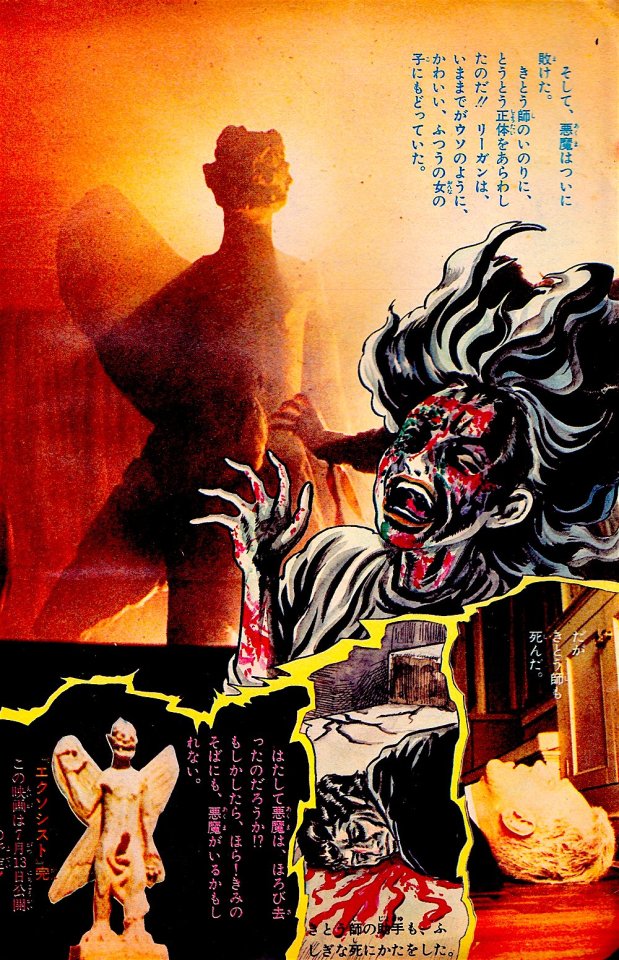

Kazuo Umezu - The Exorcist Comic, 1974

Originally published in the July 7th, 1974 issue of Shonen Sunday, a week before the film's Japanese release.

https://monsterbrains.blogspot.com/2022/07/kazuo-umezu-exorcist-comic-1974.html

478 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sousou no Frieren Vol.13

#sousou no frieren#frieren: beyond journey's end#kanehito yamada#tsukasa abe#shonen sunday comics#shogakukan#manga

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

Takashi Shiina Blog Translation - First Chapter Completed

09/01/2021

The first chapter is completed. Regarding this blog, it will have notes and advertisements before the chapter is released and when the manuscript has been finished, with a cut image at the beginning, and I’ll write about this and that, but this time I won’t post spoilers.

I think this project of me drawing “Yashahime” is interesting in terms of matching itself. I’d laugh too if I was told “Takashi Shiina will draw a Rumiko Takahashi manga” (laugh). Well, you could certainly say that this is an original anime project that uses “InuYasha” as its base.

I think those who saw the announcement (of the manga) and have interest in it feel expectation and suspense like “what is Shiina-sensei exactly going to cook and how is he going to wrap it up”. That’s why I want you to taste that until the moment you pick it up and read it (laugh).

(The first chapter) went over well for those in the staff who checked the storyboard and Takahashi Rumiko-sensei also praised it, so I think the result wasn’t bad. My self checking function is often broken, but if it passes Takahashi-sensei’s standards, it’s okay (laugh). I sat down and drew more than (the usual number of pages) expected for weekly publication. It’s okay if you look forward to it… I think… probably. At least I hope you guys enjoy it as it turned out to be “a comicalization of my liking” for me.

Therefore, please wait a little bit longer until the Weekly Shonen Sunday S (Super) is released around 09/25.

Source: https://cnanews.asablo.jp/blog/2021/09/01/9417955

#inuyasha#犬夜叉#inu yasha#anime#manga#rumiko takahashi#yashahime#hanyou no yashahime#takashi shiina#takashi talks

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

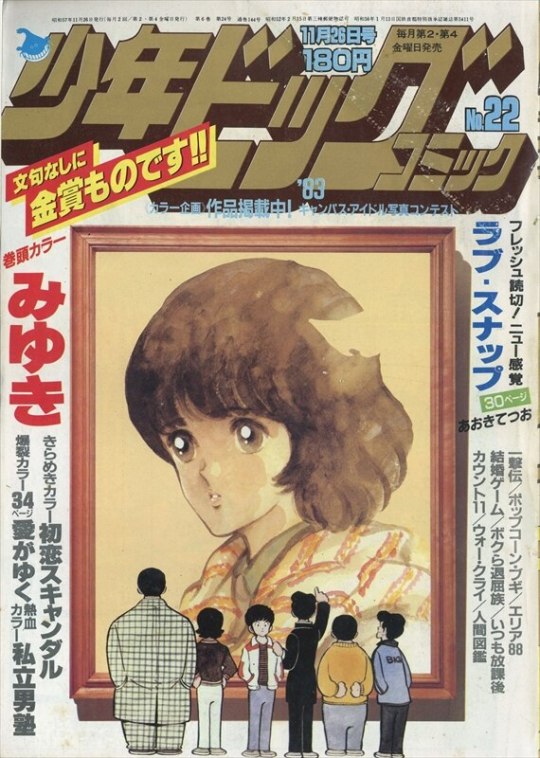

Shōnen Big Comic (少年ビッグコミック) / Shōgakukan (小学館) / 26th Nov 1982 issue

#vintage manga#shonen manga#retro shonen#80s manga#mitsuru adachi#shonen sunday#big comic#shogakukan#issue month: november#少年ビッグコミック#小学館

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

Noragami on Hiatus this month... but for good reasons

Regarding Monthly Shonen Magazine Issue 6 (on sale 5/6)

“Noragami” will be on hiatus for this issue.

In the issue on sale in June (Issue 7), chapter 100 will not be split, but appearing all at once!!

Furthermore, there will be information regarding the “100 Chapters Commemoration Project” and Comics Volume 25. We have lots of plans for chapter 100 and the tankoubon release!

Please look forward to it!

Issue 7 looks like it’s coming out 6/6, which is 6/5 for me, so that’ll give me all of Sunday to work on the full chapter, which should hopefully not be a problem. From the back cover preview of this month’s issue, looks like “Noragami” will get a cover image and the chapter 100 commemoration is some kind of gift.

381 notes

·

View notes

Text

art by ANDREU-T

#Shogakukan#Shueisha#Shonen Sunday#Business Jump#Ranma 1/2#Battle Angel Alita#Alita: Battle Angel#Gunnm#Mortadelo y Filemón#Mortadelo y Filemon#Mortadelo and Filemon#Mort & Phil#Mort and Phil#Clever & Smart#Clever and Smart#retro#vintage#european comics

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Which Manga should get the Full Metal Alchemist Brotherhood/second anime adaptaion treatment?

To clarify what I mean by by a second anime adaptaion, it means these would follow the events of the original Light Novel from beginning to end (or up to the current point) and retain the original character personalities and development.

For example, Naruto and Naruto Shippuden would omit all of the filler arcs and anime original characters.

Another example would be Akame ga Kill where the original ending was replaced by an anime original ending, so a second anime adaptaion would restore the original ending.

Hope it clears things up.

#Naruto (Series)#Black Cat (Anime Series)#InuYasha (Series)#Zatch Bell! (Series)#Love Hina#Rave Master#Soul Eater#Akame ga Kill!#Magic Knight Rayearth#Princess Knight#Question Poll

6 notes

·

View notes