#royalties

Text

Spotify don't be a terrible service challenge (IMPOSSIBLE)

#Spotify#streaming#royalties#stream#streams#popularity contest#payments#royalty#capitalism#Apple Music#Tidal#better streaming platforms than Spotify#Spotify sucks#Billboard#music industry#industry#music#music news#twitter

291 notes

·

View notes

Text

It's been a whole god damn week and I'm going to need the people being absolute fucktrumpets in my inbox over my "fuck Audible post" to simmer the fuck down and stop telling me "I have other options" when I'm already utilizing every option available to me and that it's my own fault for using Amazon.

I have gone wide with global distribution for my titles since day one. I have every global retailer available to me as an indie author listed here and on my website. People still choose Amazon because it is cheap and convenient. Removing Amazon listings won't drive people to the other retailers, it'll just mean I won't get 80% of my sales which I rely on to pay bills and help put food on the table.

Also to the people absolutely jacking off in my inbox over how I should just use Scribd because it's superior to Amazon for authors, I'm going to need you to show your sources, because here's mine:

ID: A screenshot of my royalty report from Scribd for the month of June 2022. It reports the "sale" of 2 units for a total profit of $1.18. /End ID.

This is a great example of why when authors tell you they can't afford to not sell on Amazon, this is why. If I'd sold 2 copies of that title on Amazon, I'd have made roughly $2.10+ (depends on currency).

Don't get me wrong, I'm still absolutely thrilled people are using paid services like Scribd to access my work. I'd rather you did that than pirate it. And by all means, keep using Scribd if that's what works for you. I'm not here to shame anyone for enjoying things however they can afford to. But don't come onto my post or into my inbox and spout bullshit about how it's "morally superior to Amazon."

Newsflash, there is no ethical consumption under mainstream capitalism. Scribd is not Amazon, and that is to its credit, but that doesn't mean it's "better for authors." It just means it's not Amazon.

Anyway, support indie authors direct where you can, order through a local indie store, ya-da-ya-da.

Fuck I'm tired.

#beating my head off a brick wall would feel more productive#indie author stuff#royalties#late stage capitalism

4K notes

·

View notes

Text

An excerpt from The Bezzle

I'm on tour with my new novel The Bezzle! Catch me next in SALT LAKE CITY (Feb 21, Weller Book Works) and SAN DIEGO (Feb 22, Mysterious Galaxy). After that, it's LA, Seattle, Portland, Phoenix and more!

Today, I'm bringing you part one of an excerpt from Chapter 14 of The Bezzle, my next novel, which drops on Feb 20. It's an ice-cold revenge technothriller starring Martin Hench, a two-fisted forensic accountant specialized in high-tech fraud:

https://us.macmillan.com/books/9781250865878/thebezzle

Hench is the Zelig of high-tech fraud, a character who's spent 40 years in Silicon Valley unwinding every tortured scheme hatched by tech-bros who view the spreadsheet as a teleporter that whisks other peoples' money into their own bank-accounts. This setup is allowing me to write a whole string of these books, each of which unwinds a different scam from tech's past, present and future, starting with last year's Red Team Blues (now in paperback!), a novel that whose high-intensity thriller plotline is also a masterclass in why cryptocurrency is a scam:

https://us.macmillan.com/books/9781250865854/redteamblues

Turning financial scams into entertainment is important work. Finance's most devastating defense is the Shield Of Boringness (h/t Dana Clare) – tactically deployed complexity designed to induce the state that finance bros call "MEGO" ("my eyes glaze over"). By combining jargon and obfuscation, the most monstrous criminals of our age have been able to repeatedly bring our civilization to the brink of collapse (remember 2008?) and then spin their way out of it.

Turning these schemes into entertainment is hard, necessary work, because it incinerates the respectable suit and tie and leaves the naked dishonesty of the finance sector on display for all to see. In The Big Short, they recruited Margot Robbie to explain synthetic CDOs from a bubble-bath. And John Oliver does this every week on Last Week Tonight, coming up with endlessly imaginative stunts and gags to flense the bullshit, laying the scam economy open to the bone.

This was my inspiration for the Hench novels (I've written and sold three of these, of which The Bezzle is number two; I've got at least two more planned). Could I use the same narrative tactics I used to explain mass surveillance, cryptography and infosec in the Little Brother books to turn scams into entertainment, and entertainment into the necessary, informed outrage that might precipitate change?

The main storyline in The Bezzle concerns one of the most gruesome scams in today's America: prison-tech, which sees America's vast army of prisoners being stripped of letters, calls, in-person visits, parcels, libraries and continuing ed in favor of cheap tablets that bilk prisoners and their families of eye-watering sums for every click they make:

https://pluralistic.net/2024/02/14/minnesota-nice/#shitty-technology-adoption-curve

But each Hench novel has a variety of side-quests that work to expose different kinds of financial chicanery. The Bezzle also contains explainers on the workings of MLMs/Ponzis (and how Gerry Ford and Betsy DeVos's father-in-law legalized one of the most destructive forces in America) and the way that oligarchs, foreign and domestic, use Real Estate Investment Trusts to hide their money and destroy our cities.

And there's a subplot about music-royalty theft, a form of pernicious wage theft that is present up and down the music industry supply-chain. This is a subject that came up a lot when Rebecca Giblin and I were researching and writing Chokepoint Capitalism, our 2022 book about creative labor markets:

https://chokepointcapitalism.com/

Two of the standout cases from that research formed the nucleus of the subplot in The Bezzle, the case of Leonard Cohen's batshit manager who stole millions from him and then went to prison for stalking him, leaving him virtually penniless and forced to keep touring to keep himself fed:

https://www.theguardian.com/music/2012/apr/19/leonard-cohen-former-manager-jailed

The other was George Clinton, whose manager forged his signature on a royalty assignment, then used the stolen money to defend himself against Clinton's attempts to wrestle his rights back and even to sue Clinton for defamation for writing about the caper in his memoir:

https://www.musicconnection.com/the-legal-beat-george-clinton-wins-defamation-case/

That's the tale that this excerpt – which I'll be serializing in six parts over the coming week – tells, in fictionalized form. It's not Margot Robbie in a bubble-bath, it's not a John Oliver monologue, but I think it's pretty goddamned good.

I'm leaving for a long, multi-city, multi-country, multi-continent tour with The Bezzle next Wednesday, starting with an event at Weller Bookworks in Salt Lake City on the 21st:

https://www.wellerbookworks.com/event/store-cory-doctorow-feb-21-630-pm

I'll in be in San Diego on the 22nd at Mysterious Galaxy:

https://www.mystgalaxy.com/22224Doctorow

And then it's on to LA (with Adam Conover), Seattle (with Neal Stephenson), Portland, Phoenix and beyond:

https://pluralistic.net/2024/02/16/narrative-capitalism/#bezzle-tour

I hope you'll come out for the tour (and bring your friends)!

Between 1972 and 1978, Steve Soul (a.k.a. Stefon Magner) had a string of sixteen Billboard Hot 100 singles, one of which cracked the Top 10 and won him an appearance on Soul Train. He is largely forgotten today, except by hip-hop producers who prize his tracks as a source of deep, funky grooves. They sampled the hell out of him, not least because his rights were controlled by Inglewood Jams, a clearinghouse for obscure funk tracks that charged less than half of what the Big Three labels extracted for each sample license.

Even at that lower rate, those license payments would have set Stefon up for a comfortable retirement, especially when added to his Social Security and the disability check from Dodgers Stadium, where he cleaned floors for more than a decade before he fell down a beer-slicked bleacher and cracked two of his lumbar discs. But Stefon didn’t get a dime. His former manager, Chuy Flores, forged his signature on a copyright assignment in 1976. Stefon didn’t discover this fact until 1979, because Chuy kept cutting him royalty checks, even as Stefon’s band broke up and those royalties trickled off. In Stefon’s telling, the band broke up because the rest of the act—especially the three-piece rhythm section of two percussionists and a beautiful bass player with a natural afro and a wild, infectious hip-wiggle while she played—were too coked up to make it to rehearsal, making their performances into shambling wreckages and their studio sessions into vicious bickerfests. To hear the band tell of it, Stefon had bad LSD (“Lead Singer Disease”) and decided he didn’t need the rest of them. One thing they all agreed on: there was no way Stefon would have signed over the band’s earnings to Chuy, who was little more than a glorified bookkeeper, with Stefon hustling all their bookings and even ordering taxis to his bandmates’ houses to make sure they showed up at the studio or the club on time. Stefon remembered October of ’79 well. He’d been waiting with dread for the envelope from Chuy. The previous royalty check, in July, had been under $250. The previous quarter’s had been over $1,000. This quarter’s might have zero. Stefon needed the money. His 1972 Ford Galaxie needed a new transmission. He couldn’t keep driving it in first.

The envelope arrived late, the day before Halloween, and for a brief moment, Stefon was overcome by an incredible, unbelieving elation: Chuy’s laboriously typewritten royalty statement ended with the miraculous figure of $7,421.16. Seven thousand dollars! It was more than two years’ royalties, all in one go! He could fix the Galaxie’s transmission and get the ragtop patched, and still have money left over for his back rent, his bar tab, his child support, and a fine steak dinner, and even then, he’d end the month with money in his savings account.

But there was no check in the envelope. Stefon shook the envelope, carefully unfolded the royalty statement to ensure that there was no check stapled to its back, went downstairs to the apartment building lobby and rechecked his mailbox.

Finally, he called Chuy.

“Chuy, man, you forgot to put a check in the envelope.”

“I didn’t forget, Steve. Read the paperwork again. You gotta send me a check.”

“What the fuck? That’s not funny, Chuy.”

“I ain’t joking, Steve. I been advancing you royalties for more than three years, but you haven’t earned nothing new since then—no new recordings. I can’t afford to carry you no more.”

“Say what?”

Chuy explained it to him like he was a toddler. “Remember when you signed over your royalties to me in ’76? Every dime I’ve sent you since then was an advance on your future recordings, only you haven’t had none of those, so I’m cutting you off and calling in your note. I’m sorry, Steve, but I ain’t a charity. You don’t work, you don’t earn. This is America, brother. No free lunches.”

“After I did what in ’76?”

“Steve, in 1976 you signed over all your royalties to me. We agreed, man! I can’t believe you don’t remember this! You came over to my spot and I told you how it was and you said you needed money to cover the extra horns for the studio session on Fight Fire with Water. I told you I’d cover them and you’d sign over all your royalties to me.”

Stefon was briefly speechless. Chuy had paid the sidemen on that session, but that was because Chuy owed him a thousand bucks for a string of private parties they’d played for some of Chuy’s cronies. Chuy had been stiffing him for months and Stefon had agreed to swap the session fees for the horn players in exchange for wiping out the debt, which had been getting in the way of their professional relationship.

“Chuy, you know it didn’t happen that way. What the fuck are you talking about?”

“I’m talking about when you signed over all your royalties to me. And you know what? I don’t like your tone. I’ve carried your ass for years now, sent you all that money out of my own pocket, and now you gotta pay up. My generosity’s run out. When you gonna send me a check?”

Of course, it was a gambit. It put Stefon on tilt, got him to say a lot of ill-advised things over the phone, which Chuy secretly recorded. It also prompted Stefon to take a swing at Chuy, which Chuy dived on, shamming that he’d had a soft-tissue injury in his neck, bringing suit for damages and pressing an aggravated-assault charge.

He dropped all that once Stefon agreed not to keep on with any claims about the forged signature; Stefon went on to become a good husband, a good father, and a hard worker. And if cleaning floors at Dodgers Stadium wasn’t what he’d dreamed of when he was headlining on Soul Train, at least he never missed a game, and his boy came most weekends and watched with him. Stefon’s supervisor didn’t care.

But the stolen royalties ate at him, especially when he started hearing his licks every time he turned on the radio. His voice, even. Chuy Flores had a fully paid-off three-bedroom in Eagle Rock and two cars and two ex-wives and three kids he was paying child support on, and Stefon sometimes drove past Chuy Flores’s house to look at his fancy palm trees all wrapped up in strings of Christmas lights and think about who paid for them.

ETA: Here's part two!

If you'd like an essay-formatted version of this post to read or share, here's a link to it on pluralistic.net, my surveillance-free, ad-free, tracker-free blog:

https://pluralistic.net/2024/02/17/the-steve-soul-caper/#lead-singer-disease

#pluralistic#the bezzle#martin hench#marty hench#red team blues#fiction#crime fiction#crime thrillers#thrillers#technothrillers#novels#books#royalties#wage theft#creative labor

99 notes

·

View notes

Text

…okay but why did this clip from Royalties 2020 predict Starkid’s future method for recasting Hatchetfield characters:

…was relaxing watching Royalties for the first time enjoying all of the cameos and now I have angst

#joey richter#starkid#team starkid#hatchetfield#the guy who didn't like musicals#black friday musical#tgwdlm#nerdy prudes must die#npmd#npmd spoilers#royalties#darren criss#robert manion#john stamos#ethan green#peter spankoffski#starkid returns#nightmare time

407 notes

·

View notes

Text

A Book Is a Book Is a Book—Except When It’s an e-Book

But corporate mega-publishers want purchasing a book to be like renting a movie or streaming an album.

by Maria Bustillos

Buying a book should be no different from buying an apple. When you buy an apple, the farmer can’t show up in your kitchen later and decide your time is up, and you’ve got to pay for it again. It’s yours forever—to eat, or paint in a still life, or cut up for a kid’s snack. And thanks to the first sale doctrine of copyright law, codified by Congress in 1909, the books on your shelves are yours forever, too, in exactly the same way your apple is; you’re free to read them (or not), loan them to friends, or sell them to a used bookshop, without restriction. Copyright law balances the public good—our collective right to access information—with the rights it grants to authors and inventors.

Publishers can’t demand more money for the paper books you’ve already bought, but the technology for copying and distributing books has evolved a lot since 1909. So four titanic corporate publishers are currently in court, insisting on the effective right to barge in and demand multiple, recurring payments for digital books–like they do for digital movies, music, and software–and they want to exercise that same power over the books in libraries.

This threat to the ownership of books is what makes the ongoing publishers’ lawsuit against the Internet Archive politically dangerous, and in an altogether different way from earlier challenges and amendments to copyright law. At a time of increasing book bannings and attacks on libraries, public schools and universities, it is not safe for democracy, or for our cultural posterity, to leave an “on/off” switch for library books in the hands of corporate publishers.

READ MORE

138 notes

·

View notes

Photo

DARREN CRISS

Royalties 1x08 "Also You"

#darrencrissedit#dcrissedit#darren criss#royaltiesedit#royalties#tvedit#filmtvcentral#cinemapix#cinematv#smallscreensource#tvandfilm#filmtv#popularculturesource#userbbelcher#chewieblog#userstream#usersource#!gif

139 notes

·

View notes

Text

In December, 2020, in the depths of pandemic winter, the actress Kimiko Glenn got a foreign-royalty statement in the mail from the screen actors’ union, SAG-AFTRA. Glenn is best known for playing the motormouthed, idealistic inmate Brook Soso on the women’s-prison series “Orange Is the New Black,” which ran from 2013 to 2019, on Netflix. The orchid-pink paper listed episodes of the show that she’d appeared on (“A Whole Other Hole,” “Trust No Bitch”) alongside tiny amounts of income (four cents, two cents) culled from overseas levies—a thin slice of pie from the show that had thrust her to prominence. “I was, like, Oh, my God, it’s just so sad,” Glenn recalled. With many television and movie sets shuttered, she was supporting herself with voice-over jobs, and she’d been messing around with TikTok. She posted a video in which she scans the statement—“I’m about to be so riiich!”—then reaches the grand total of $27.30 and shrieks, “WHAT?”

The post got more than four hundred thousand likes and nearly two thousand comments, many from disbelieving fans: “Wait how is that even legal??” “how is this even real you were on one of the biggest netflix shows.” This past May, with screenwriters on strike and labor unrest sweeping Hollywood, Glenn reposted the video on Instagram, where she has almost a million followers. This time, not only fans but castmates weighed in. Matt McGorry, who played a corrections officer: “Exaccctttlllyyy. I kept my day job the entire time I was on the show because it paid better than the mega-hit TV show we were on.” Beth Dover, who played a manager at the company taking over the prison: “It actually COST me money to be in season 3 and 4 since I was cast local hire and had to fly myself out, etc. But I was so excited for the opportunity to be on a show I loved so I took the hit. Its maddening.”

Television actors have traditionally had a base of income from residuals, which come from reruns and other forms of reuse of the shows in which they’ve appeared. At the highest end, residuals can yield a fortune; reportedly, the cast of “Friends” has each made tens of millions of dollars from syndication. But streaming has scrambled that model, endangering the ability of working actors to make a living. “So many of my friends who have nearly a million followers, who are doing billion-dollar franchises, don’t know how to make rent.”

Despite the Beatlemania-like fame, many cast members had to keep their day jobs for multiple seasons. They were waiting tables, bartending. DeLaria continued doing live gigs to keep up with her rent. Diane Guerrero, who played the fashionable inmate Maritza Ramos, worked at a bar, where patrons would recognize her.

These are just some highlights, but the entire article is worth a read, especially if someone you know is (or you are) so deep into watching celebrity culture that you’re having a hard time understanding why actors could possibly want more than they’re getting now.

#orange is the new black#netflix#streaming#actors#residuals#royalties#wga strike#sag-aftra strike#solidarity forever#hot union summer#summer of strikes

54 notes

·

View notes

Photo

(via Denying Black Musicians Their Royalties Has a History Emerging Out of Slavery - The Temple 10-Q)

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

Belgian royalties on a ceremony

Belgian vintage postcard

#postcard#ceremony#postal#sepia#briefkaart#tarjeta#photography#postkarte#historic#belgian#vintage#postkaart#carte postale#ephemera#ansichtskarte#royalties#old#photo

12 notes

·

View notes

Note

If I had a nickel for every time the Langs wrote a musical that implied that the Prince in Cinderella had a foot fetish, I’d (probably) have two nickels, which isn’t a lot, but it’s weird that it (probably) happened twice, right?

https://youtube.com/clip/UgkxSq2Ma1UbikUAgT6J7RXDiEahtZVbW5da?si=nW45ViEOqXEsY4te

~~~

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

How much authors make on print vs ebook

In looking at a $17.99 paperback vs a $7.99 ebook of the same title, you might assume it would help the author more if you bought the paperback. After all, it's fully $10 more! But: nope. At least with the book contracts I have, I get more money from the ebook, even at those prices.

How? Because I get a higher royalty rate on ebooks than on print. I get 10% (usually) of the profit on print books, so from that $17.99 book sale, $1.79 comes to me. (That's simplifying things. It's actually a bit less, since I get 10% of NET profits, not gross. But the numbers are close enough.) With ebooks, meanwhile, I usually get 35% of the profits, so I get $2.79 coming to me from that $7.99 ebook. And with some of my titles, I get 50% of ebook profits, so even better!

These exact percentages vary based on one's publishing contracts (they even vary among my different titles), but the above is the basic idea, and is probably pretty true across most of the industry.

Print books just cost a lot more than ebooks, since they have to be printed, bound, shipped, and stored, which means more people needing to be paid for their part in the process. We all want brick-and-mortar bookstores to thrive, and we all love physical books, so by all means, let us keep supporting those places. But ebooks do often pay authors better than print does, so no need to feel bad if you buy a lot of those too. :)

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

instagram

#Spotify#Spotify Wrapped#Spotify sucks#Apple Music#TIDAL#are better platforms#music industry#royalties#royalty#Capitalism#corporate greed#Instagram

171 notes

·

View notes

Text

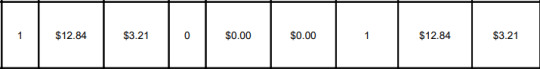

Not to dredge the Audible discourse up again, but I said I'd come back when I had more numbers, and this post is specifically aimed at the people still trying to claim in my inbox that 'Scribd pays authors better than Audible' and giving me shit for using Audible as an author.

So here we go. This is what I earn per 1 book via Audible purchase vs. Audible subscription:

Image ID: a screenshot from ACX, the Audible portal for authors. The text is broken up into boxes. Running from left to right, it reads Hunger Pangs: True Love Bites (Unabridged) by Joy Demorra. The sales region shown is the UK, and my royalty rate is Audible's standard of 25%. The number of units sold is 1. The amount the person paid is $25.59. My earnings from this sale is $6.40.

The following image is the same data but taken from Audible credits. The quality "sold" is 1, at a rate of $12.84, giving me a payment of $3.21. The next few numbers denote zero, showing no returns, making my earnings from Audible credit for this region $3.21. /End ID.

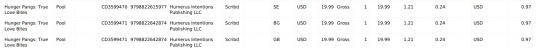

And this is what I earned from Scribd (sorry it's so small, I don't know if anyone will be able to read it):

Image ID: Another screenshot from the FindAwayVoices portal shows my royalty earnings from Scribd across three regions.

From top to bottom, it shows the number of sales for Hunger Pangs: True Love Bites, followed by a series of ID numbers. It also shows three individual sales from Sweden, Bulgaria, and the UK. The individuals have paid the equivalent of $19.99 in subscription fees. Out of that $19.99, Scribd pays me $1.21, and then FindawayVoices subtracts a further 0.24cents as a distribution fee leaving me with a total income of 0.97cents per book read. /End ID.

Now, I am aware that the Scribd subscription fee allows customers to listen to multiple things for the cost of their monthly fee without forcing them to return it the way Audible does. This means the author isn't subjected to negative income which is a good thing. And if that works for you, great. I'm happy for you. I am glad you have found a way to enjoy media that still pays authors something.

But can people who don't have a clue how the industry works please stop making unfounded claims that Scribd is 'better' and 'more ethical than Amazon' and 'actually pays authors' because, as you can see from the above, that's a crock of shit.

I'm not saying this to shame anyone. I'm not trying to guilt anyone for using Scribd services. Again, if it is something that works for you and you can afford it, great. Please keep using it. I would rather earn 97cents than nothing. But I am sick and tired of people who don't work the industry telling authors we have 'better options than Audible' then listing places like Scribd, seemingly operating on the belief that just because it isn't Amazon, it's inherently better.

My inbox is a nightmare of people telling me I deserve to have my work stolen for using Amazon at all, and I don't know how people can say things like that without realizing they're also the villain.

And just for the people saying it's illegal for Amazon to take refunds from the authors and leave us with negative income and we're all lying:

ID: another screenshot from ACX, the Audible portal for authors. The text is broken up into boxes. Running from left to right, it reads Hunger Pangs: True Love Bites (Unabridged) by Joy Demorra. The sales region shown is the UK, and my royalty rate is Audible's standard of 25%. There are no individual outright sales, but there is a negative credit indicating a return, with the subscription fee shown as -$13.31 (note: this is MORE than what Amazon charges for a sale ($12.84)) with a negative royalty rate of -$3.33 for the author, which is also 12 cents MORE than what we earn for a non-returned sale.

There is some debate over why this is, but the most prevalent idea at the moment is that this is Amazon factoring in the exchange rate, and making authors pay it. So not only are we paying for the return and making a negative income, but we're also paying the cost of the exchange rate. 🙃🙃🙃

And people are wondering why authors are screaming about booktok "hacks" that promote returning books even if you enjoyed them and begging people to use libraries instead. And just in case you want to see those figures:

Image ID: Another screenshot from the FindAwayVoices shows Library transaction details. The library paid $29.99 for the lending license, earning me a royalty fee of $13.50. FindAwayVoices took a further fee of $2.70 for distribution, making my total income from a single library transaction $10.80. /End ID.

With that single library transaction, I have earned more than what I made from 5 separate sales from both Amazon and Scribd combined. And I will continue to earn royalties from the library lending service. Not much. It will probably be about a dollar max depending on the country and exchange rate. BUT--that's a dollar I am making that YOU don't have to pay for. This is why library lending services are so essential and why authors are begging readers/listeners to use services like OverDrive and Libby instead of abusing Amazon return policies.

Libraries pay us. And the more people request our books and check them out, the more likely they will be to keep buying our stuff and keep us in their catalog.

So please, please, please, support your local libraries and also stop harassing creators for using multiple platforms to sell our work. Most of us are making a pittance from our work. We don't need people who don't understand how rigged the system is against us lecturing us about how it's our fault because of where we are forced to sell just to try and make a living. 😔

Anyway, support authors direct where you can. Support your local libraries. Stop being a dick to creators, etc.

I'm going to go scream into a pillow for a bit then get back to work.

Edit: sorry for the weird formatting. I have no idea how that happened. I couldn't see the excess text until it posted.

#long post#described#audible#scribd#indie author#indie publishing#publishing#sales figures#royalties#the reality of publishing#there is no ethical consumption under late stage capitalism#this is the bad place

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

The Bezzle excerpt (Part II)

I'm on tour with my new novel The Bezzle! Catch me next in SALT LAKE CITY (Feb 21, Weller Book Works) and SAN DIEGO (Feb 22, Mysterious Galaxy). After that, it's LA, Seattle, Portland, Phoenix and more!

Today, I'm bringing you part two of this week's serialized excerpt from The Bezzle, my new Martin Hench high-tech crime revenge thriller:

https://us.macmillan.com/books/9781250865878/thebezzle

Though most of the scams that Hench – a two-fisted forensic accountant specializing in Silicon Valley skullduggery – goes after in The Bezzle have a strong tech component, this excerpt concerns a pre-digital scam: music royalty theft.

This is a subject that I got really deep into when researching and writing 2022's Chokepoint Capitalism – a manifesto for fixing creative labor markets:

https://chokepointcapitalism.com/

My co-author on that book is Rebecca Giblin, who also happens to be one of the world's leading experts in "copyright termination" – the legal right of creative workers to claw back any rights they signed over after 35 years:

https://pluralistic.net/2021/09/26/take-it-back/

This was enshrined in the 1976 Copyright Act, and has largely languished in obscurity since then, though recent years have seen creators of all kinds getting their rights back through termination – the authors of The Babysitters Club and Sweet Valley High Books, Stephen King, and George Clinton, to name a few. The estates of the core team at Marvel Comics, including Stan Lee, just settled a case that might have let them take the rights to all those characters back from Disney:

https://www.thewrap.com/marvel-settles-spiderman-lawsuit-steve-ditko/

Copyright termination is a powerful tonic to the bargaining disparities between creative workers. A creative worker who signs a bad contract at the start of their career can – if they choose – tear that contract up 35 years later and demand a better one.

Turning this into a plot-point in The Bezzle is the kind of thing that I love about this series – the ability to take important, obscure, technical aspects of how the world works and turn them into high-stakes technothriller storylines that bring them to the audience they deserve.

If you signed something away 35 years ago and you want to get it back, try Rights Back, an automated termination of tranfer tool co-developed by Creative Commons and Authors Alliance (whose advisory board I volunteer on):

https://rightsback.org/

All right, onto today's installment. Here's part one, published on Saturday:

https://pluralistic.net/2024/02/17/the-steve-soul-caper/#lead-singer-disease

It was on one of those drives where Stefon learned about copyright termination. It was 2011, and NPR was doing a story on the 1976 Copyright Act, passed the same year that was on the bottom of the document Chuy forged.

Under the ’76 act, artists acquired a “termination right”— that is, the power to cancel any copyright assignment after thirty-five years, even if they signed a contract promising to sign away their rights forever and a day (or until the copyright ran out, which was nearly the same thing).

Listening to a smart, assured lady law professor from UC Berkeley explaining how this termination thing worked, Stefon got a wild idea. He pulled over and found a stub of a pencil and the back of a parking-ticket envelope and wrote down the professor’s name when it was repeated at the end of the program. The next day he went to the Inglewood Public Library and got a reference librarian to teach him how to look up a UC Berkeley email address and he sent an email to the professor asking how he could terminate his copyright assignment.

He was pretty sure she wasn’t going to answer him, but she did, in less than a day. He got the email on his son’s smartphone and the boy helped him send a reply asking if he could call her. One thing led to another and two weeks later, he’d filed the paperwork with the U.S. Copyright Office, along with a check for one hundred dollars.

Time passed, and Stefon mostly forgot about his paperwork adventure with the Copyright Office, though every now and again he’d remember, think about that hundred dollars, and shake his head. Then, nearly a year later, there it was, in his mailbox: a letter saying that his copyright assignment had been canceled and his copyrights were his again. There was also a copy of a letter that had been sent to Chuy, explaining the same thing.

Stefon knew a lawyer—well, almost a lawyer, an ex–trumpet player who became a paralegal after one time subbing for Sly Stone’s usual guy, and then never getting another gig that good. He invited Jamal over for dinner and cooked his best pot roast and served it with good whiskey and then Jamal agreed to send a letter to Inglewood Jams, informing them that Chuy no longer controlled his copyrights and they had to deal with him direct from now on.

Stefon hand-delivered the letter the next day, wearing his good suit for reasons he couldn’t explain. The receptionist took it without a blink. He waited.

“Thank you,” she said, pointedly, glancing at the door.

“I can wait,” he said.

“For what?” She reminded him of his boy’s girlfriend, a sophomore a year younger than him. Both women projected a fierce message that they were done with everyone’s shit, especially shit from men, especially old men. He chose his words carefully.

“I don’t know, honestly.” He smiled shyly. He was a good-looking man, still. That smile had once beamed out of televisions all over America, from the Soul Train stage. “But ma’am, begging your pardon, that letter is about my music, which you all sell here. You sell a lot of it, and I want to talk that over with whoever is in charge of that business.”

She let down her guard by one minute increment. “You’ll want Mr. Gounder,” she said. “He’s not in today. Give me your phone number, I’ll have him call.”

He did, but Mr. Gounder didn’t call. He called back two days later, and the day after that, and the following Monday, and then he went back to the office. The receptionist who reminded him of his son’s girlfriend gave him a shocked look.

“Hello,” he said, and tried out that shy smile. “I wonder if I might see that Mr. Gounder.”

She grew visibly uncomfortable. “Mr. Gounder isn’t in today,” she lied. “I see,” he said. “Will he be in tomorrow?”

“No,” she said.

“The day after?”

“No.” Softer.

“Is that Mr. Gounder of yours ever coming in?”

She sighed. “Mr. Gounder doesn’t want to speak with you, I’m sorry.”

The smile hadn’t worked, so he switched to the look he used to give his bandmates when they wouldn’t cooperate. “Maybe someone can tell me why?”

A door behind her had been open a crack; now it swung wide and a young man came out. He looked Hispanic, with a sharp fade and flashy sneakers, but he didn’t talk like a club kid or a hood rat—he sounded like a USC law student.

“Sir, if you have a claim you’d like Mr. Gounder to engage with, please have your attorney contact him directly.”

Stefon looked this kid up and down and up, tried and failed to catch the receptionist’s eye, and said, “Maybe I can talk this over with you. Are you someone in charge around here?”

“I’m Xavier Perez. I’m vice president for catalog development here. I don’t deal with legal claims, though. That’s strictly Mr. Gounder’s job. Please have your attorney put your query in writing and Mr. Gounder will be in touch as soon as is feasible.”

“I did have a lawyer write him a letter,” Stefon said. “I gave it to this young woman. Mr. Gounder hasn’t been in touch.”

Perez looked at the receptionist. “Did you receive a letter from this gentleman?”

She nodded, still not meeting Stefon’s eye. “I gave it to Mr. Gounder last week.”

Perez grinned, showing a gold tooth, and then, in his white, white voice, said, “There you have it. I’m sure Mr. Gounder will get back in touch with your counsel soon. Thank you for coming in today, Mr.—”

“Stefon Magner.” Stefon waited a moment, then said, for the first time in many years, “I used to perform under Steve Soul, though.”

Perez nodded briskly. He’d known that. “Nice to meet you, Mr. Magner.” Without waiting for a reply, he disappeared back into his office.

ETA: Here's part three!

If you'd like an essay-formatted version of this post to read or share, here's a link to it on pluralistic.net, my surveillance-free, ad-free, tracker-free blog:

https://pluralistic.net/2024/02/19/crad-kilodney-was-an-outlier/#copyright-termination

#pluralistic#the bezzle#martin hench#marty hench#red team blues#fiction#crime fiction#crime thrillers#thrillers#technothrillers#novels#books#royalties#wage theft#creative labor

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

A prompt meme collection for fics about Tony Revolori characters!

Whether it's Graydon or Flash, Jason or Zero, Jib, Deuce, Theo, Nat, Chester, Tobe or any other character -- if he's played by Tony, we want your ideas and stories!

Come submit prompts for fics or fill prompts yourself. If you have questions the FAQ doesn't cover, send us an ask or hit us up at [email protected]!

#tony revolori#graydon hastur#willow 2022#flash thompson#spider-man#jason carvey#scream vi#zero moustafa#the grand budapest hotel#jib#dope#deuce gorgon#monster high#the long dumb road#take the 10#royalties#servant#prompt meme#fic challenge#revolori promptorium#revolorilution#graylora#graydon x elora#graythrax#graydon x boorman#grayairk#graydon x airk#spideyflash#flash x peter

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Chris Gural

48 notes

·

View notes