#philippa of hainaut

Text

Favorite History Books || Philippa of Hainault: Mother of the English Nation by Kathryn Warner ★★★★☆

Edward III, king of England, was fifteen years old at the time of his wedding in York on 24 or 25 January 1328, and Philippa of Hainault, his bride, was perhaps fifteen months or so younger and, according to one chronicler, about to turn fourteen. Although their marriage was to endure for more than four decades and would prove to be a most happy and successful one that produced a dozen children, it could hardly have begun in a more unromantic fashion. Edward’s mother Queen Isabella had arranged her son’s marriage with Philippa’s father Willem, count of Hainault in 1326 so that he would provide ships and mercenaries for her to invade her husband Edward II’s kingdom in order to bring down the man she loathed above all others, Edward II’s adored chamberlain and perhaps lover Hugh Despenser the Younger. Just a month before his wedding to Philippa, Edward III had attended the funeral of his deposed, disgraced and possibly murdered father, the former king, at St Peter’s Abbey in Gloucestershire. Whether intentionally or not, Edward III and Philippa of Hainault married on his parents’ twentieth wedding anniversary, and on the first anniversary of the young Edward’s reign as king of England.

Philippa of Hainault accompanied her husband abroad on many of his military and diplomatic missions; the couple hated to be apart for long and spent as much time together as they possibly could. Despite Philippa’s decades-long marriage to one of medieval England’s most famous and successful kings, there has only ever been one full-length biography of her, published by Blanche Christabel Hardy in 1910 and titled Philippa of Hainault and Her Times. In addition, two chapters in Agnes Strickland’s nineteenth-century work The Lives of the Queens of England cover the basics of Philippa’s life, and Lisa Benz St John’s 2012 book Three Medieval Queens examines the lives of Philippa and her two predecessors as queen of England.

#litedit#historyedit#house of plantagenet#philippa of hainaut#medieval#french history#belgian history#english history#european history#women's history#history#history books#nanshe's graphics

62 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hi! I was reading some of your previous posts and saw a brief comparison between Alyssa Velaryon and Isabella of France. Could you elaborate a little more on the parallels between them? I've always had a fascination for Isabella's story, and I think Alyssa is a character who doesn't get nearly as much credit as she deserves for her support of the Targaryen dynasty.

I do think that GRRM was partly inspired by Isabella of France, queen to King Edward II and mother of King Edward III of England, when creating Alyssa Velaryon. Specifically, though, I think GRRM was heavily, perhaps even primarily drawing on Isabella of France as she is depicted in The Accursed Kings novels by Maurice Druon (I know, I know, it me) - and unfortunately (especially given the, let's say problematic nature of that series), not to the benefit of Alyssa.

Both Isabella (again, as depicted by Maurice Druon) and Alyssa are initially married to kings the narrative clearly wants to portray as weak. Just as GRRM described Aenys physically as "[a] weakling" who was "[a]s tall as his father Aegon, but softer looking", "[s]lender, weedy, [and] dreamy", so Druon notes that while Edward II was "a fine-looking man, muscular, lithe and alert", Edward's "forehead was utterly unlined, as if the anxieties of power had failed to mark him", his "long chin" was "merely too big and too elongated ... whose weakness the silky beard could not conceal", his hand "was flaccid ... flutter[ing] aimlessly and then tugg[ing] at a pearl sewn to the embroidery of his tunic", "[h]is voice ... merely suggested lack of control", and "[h]is back ... curved unpleasantly from the neck to the waist, as if the spine lacked substance". (Druon does not precisely emphasize this point, but I think it's probable that GRRM was also thinking of the contrast between Druon's weak and unimposing Edward II and his indomitable conqueror father, Edward I, when trying to underline the contrast between the "weakling" Aenys and his warrior and conqueror father, Aegon I.) Too, just as Aenys came to the throne only to face, almost immediately, a slew of rebellions - Lodos, Harren the Red, the Vulture King, and Jonos Arryn - so Edward II ( in the fifth novel of Druon's series, The She-Wolf of France) complained about rebellions again him, past and current: "The Scots are always threatening and invading my frontiers", he moaned, while "my barons of the Marches raise troops against me on the principle that they hold their lands by their swords" and Roger Mortimer, former magnate of the Marches, had so recently escaped imprisonment and fled to France. Although GRRM substitutes a much more condensed reign for Aenys I for the timeskip Druon gave the English court in his novels (as Druon focused little on Edward II until the opening of The She-Wolf of France), both kings are eventually deposed in the midst of rebellions against their respective rules (formally in the case of Edward II, while somewhat less formally in the case of Aenys I). If Alyssa Velaryon is perhaps less a leader in the rebellion which puts her son on the throne than Isabella is in hers - Alyssa flees to Storm's End with her two youngest surviving children and supporters of Jaehaerys thereafter gather there to acclaim him, while Isabella was at the front of the invasion force, dressed in armor and backed by Hainaut soldiers she had gained thanks to the betrothal she had arranged between her son Edward and the Count's daughter Philippa - both nevertheless see their sons assume royal power at the age of 14.

Too, although the circumstances of those rebellions are quite different (and in fact, GRRM may have shifted some of the antagonism against Edward II, and generally Edward II's own position as a villain in Druon's narrative, to Aenys' brother and successor Maegor, also de facto deposed), both Isabella and Alyssa then become romantically/sexually involved with leaders of these rebellions. Indeed, I find it not at all coincidental that GRRM shifted from the name "Robar Baratheon" to "Rogar Baratheon", because of the strikingly similarity between "Rogar" and "Roger" - that is, Roger Mortimer, Queen Isabella's chief ally and lover. Nor do the similarities end at their respective names. Just as Rogar Baratheon was the grandson of Orys Baratheon and a powerful magnate in his own right as Lord of Storm's End, so Roger Mortimer was both "a descendant of a companion of William the Conqueror" (whom Mortimer's uncle, also named Roger Mortimer, described to his nephew as "our kinsman") as well as a powerful aristocrat before his relationship with the queen (as "eighth Baron of Wigmore, Lord of the Welsh Marches ... the King’s ex-Lieutenant of Ireland" and "the Justiciar of Wales"); likewise, both are proud, ambitious men, eager and even desperate to seize and hold onto supreme royal power (with Rogar trying first to integrate his Baratheon relatives by marriage into the royal family and then openly conspiring to overthrow Jaehaerys in favor of a puppet-queen in the person of Aerea Targaryen, and with Druon describing Roger Mortimer as one "born with the soul of a king" who "had been obsessed by an impatient longing for power").

Unfortunately, this is where the influence of The Accursed Kings results in a distinctly (well, perhaps more distinctly) negative character experience for Alyssa Velaryon. In keeping with the rampant misogyny observable throughout The Accursed Kings, Druon depicts Isabella as virtually entirely ruled by Roger Mortimer once the two of them begin their relationship. Druon blithely informs the audience (in The She-Wolf of France) of his view that "[t]hough a woman may be a queen, her lover is always her master" (ugh) and thereafter has Isabella continually defer to Mortimer. Worse, in this vein, Isabella is shown multiple times as having to put up with or give in to Mortimer's petty jealousy, selfishness, and rage. When Isabella gives an innocuous sign of thanks to one of their Hainaut allies during the landing in England, Mortimer is so incensed at what he perceives as a flirtation that Isabella the has to overtly acknowledge thereafter that "it was thanks to Lord Mortimer that she had been able to return so strongly supported", while "pras[ing] his services highly and order[ing] that Lord Mortimer’s opinion should prevail in all things; when Isabella shows a "hysterical gratitude" during sex with Mortimer (I know, I hate it too) following the execution of Edward II's lover Hugh Despenser, Mortimer immediately assumes that Isabella's passion and fury against Despenser means that she "must surely once have loved Edward"; and when Isabella refuses to order her husband murdered, Mortimer stalks out, threatening to leave forever, until Isabella, weeping and clinging to him, begs Mortimer to stay and agrees to order whatever he wants done with Edward.

In turn, Alyssa Velaryon shows little in the way of her own voice and agency, and indeed sometimes finds herself at the mercy of her own rebel-lover's bullying leadership. When Alyssa decides to go to Dragonstone to beg Jaehaerys and Alysanne to return, Rogar "angrily" forbids her from doing so, dismissively referring to Jaehaerys as "the boy" for good measure. When Alyssa finally acknowledges that the regency government has to accept Jaehaerys' marriage to Alysanne, Rogar declares that to Alyssa that she is "weak ... as weak as your first husband was, as weak as your son". Worse, when Alyssa refuses to accept Rogar's actively treasonous plan to depose Jaehaerys in favor of Aerea, Rogar insults her as "[w]oman" (emphasis in original) and mockingly asks "[y]ou think you can dismiss me"? Moreover, just as Isabella had been reduced (by Druon) to tears by Mortimer's temper tantrum over her refusal to murder Edward II, so GRRM has Alyssa start crying when Rogar throws a fit over the acknowledgement of Jaehaerys' marriage to Alysanne (with the supremely frustrating additional note that the tears came "as if to prove that he [i.e. Rogar] had spoken truly" - that is, by calling her weak).

And, just as unfortunately, both Isabella and Alyssa "die" - the former narratively, the latter first narratively and then literally - in ways related to pregnancies caused by their respective second husbands/lovers. Toward the end of the sixth novel, The Lily and the Lion, Isabella becomes pregnant by Roger Mortimer, a condition that fills her son Edward with disgust and alarm. Fearful that, as young Edward puts it, "Mortimer is perfectly capable of killing us all, marrying my mother so as to get himself recognized as Regent and then claiming the throne for his bastard", Edward sets out to depose and arrest Roger Mortimer - an event that, so the novel implies, causes Isabella to suffer a miscarriage of her child by Mortimer. After this miscarriage, Isabella all but disappears from the story: Robert of Artois muses in The Lily and the Lion that "[h]e would have liked to see Queen Isabella, who was really the only person in England with whom he had memories in common", while Druon then adds that Isabella "no longer appeared at Court" and "[s]ince Mortimer’s execution ... no longer took any interest in anything" and flatly comments in his "Historical Notes" that "Queen Isabella still had another twenty years to live, but she took no further part in affairs". (This, in case you were wondering, is not true at all.) Even in the seventh novel, The King Without a Kingdom, the in-universe narrator Cardinal Talleyrand barely acknowledges Isabella, merely noting that "she is still alive" as of 1356, in "a huge and sad castle where, twenty-eight years ago, her son locked her up after he had had her lover, Lord Mortimer, executed", because "[f]ree, she would have caused him far too much trouble"

GRRM, for his part (and bafflingly, if you ask me), not only emotionally crushes Alyssa in a similar manner - recall Barth's conclusion that Alyssa "could not survive" Rogar's fury at being dismissed as Hand, which instead apparently "shattered her" - but decides that he needs to physically eliminate Alyssa from the narrative in ways even beyond what Druon had done to Isabella. If Alyssa is given the barest amount more presence in the story following the end of the regency (and the effective end of her relationship with her husband) than Isabella is following the end of Edward's regency (and the definite end of her relationship with her lover), it is nevertheless a sham of representation in the spirit, if not the letter, of Druon's narrative. Alyssa Velaryon's reunion with her son is summarized a brief third-hand account, and she participates in no public (much less private or familial) events or activities at either the Red Keep or Storm's End following her departure from the capital (even Druon allowed, in passing mentions, that Edward III would annually spend Christmas with his mother); indeed, Alyssa's only further involvement in the story is in conceiving, carrying, and giving birth to Boremund and Jocelyn Baratheon. Worse, while not entirely shying away from Rogar's guilt in forcing his wife to undergo a dangerous (much less drastically unnecessary) second pregnancy - indeed, Rhaena's vehement denunciation of Rogar following her mother's death is one of the (very) few truly bright spots in F&B for me - GRRM nevertheless indulges in a gruesome and lurid depiction of Alyssa Velaryon's final hours that itself provides Alyssa no opportunity to voice her own thoughts and feelings.

Did I mention I really, really don't care for the way Alyssa Velaryon is depicted in F&B?

43 notes

·

View notes

Text

currently doing a Frostfur as Philippa of Hainaut and Lionheart as Edward III family tree, will keep you updated because I can't be the only one to suffer

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Queens of Six: Genealogical Connections

Hey! I promised a long time ago to make a post about some of the familial relationships between the queens. While some, like Boleyn and Howard’s relationship as cousins, are fairly well known within the queendom, others aren’t.

All six of the queens shared a common ancestor in King Edward I of England. This means they were all direct descendants of him and one or both of his wives, or that he was a great-great-great (etc) grandfather of all six queens.

I’m happy to provide more details on these connections if requested!

Note: The royal families of the era were fairly closely related, so many of the queens were related in several ways. I generally used the closest genetic connection I could find, but I included several of those relationships for a few of them.

Aragon and Boleyn

- Aragon and Boleyn were 6th cousins 2x removed. They shared ancestors in King Edward I of England and his wife Eleanor of Castile, who were Aragon’s 5th great-grandparents and Boleyn’s 7th great-grandparents. Boleyn was also descended from Edward I and his wife Margaret of France.

Aragon and Seymour

- Aragon and Seymour were 4th cousins 3x removed. They shared ancestors in King Edward III of England and his wife Philippa of Hainault, who were Aragon’s 3rd great-grandparents and Seymour’s 6th.

Aragon and Cleves

- Aragon and Cleves were 5th cousins 1x removed. They shared ancestors in King Peter II of Sicily and his wife Elizabeth of Carinthia, who were Aragon’s 4th great-grandparents and Cleves’ 5th.

- They were also 5th cousins 2x removed via Count William I of Hainaut and his wife Joan of Valois, who were Aragon’s 4th great-grandparents and Cleves’ 6th.

Aragon and Howard

- Aragon and Howard were 6th cousins 1x removed. They shared ancestors in King Edward I of England and his wife Eleanor of Castile, who were Aragon’s 5th great-grandfather and Howard’s 7th. Howard was also descended from a child of Edward I and his other wife, Margaret of France.

Aragon and Parr

- Aragon and Parr were 3rd cousins 2x removed. They shared an ancestor in John of Gaunt, who was Aragon’s 2nd great-grandfather and Parr’s 4th. However, they were descended from children of different wives - Aragon from Constance of Castile and Parr from Katherine Swynford.

- Catherine Parr’s mother, Maud Green, was Aragon’s lady-in-waiting and a close friend. Aragon served as Catherine’s godmother, and it’s speculated that she was named after her.

Boleyn and Seymour

- Boleyn and Seymour were 2nd cousins. They shared an ancestor in Elizabeth Cheney, who was their great-grandmother, but they were descended from children of different husbands - Boleyn from Sir Frederick Tilney and Seymour from Sir John Say. This made their grandmothers, Elizabeth Tilney and Anne Say, half-sisters.

Boleyn and Cleves

- Boleyn and Cleves were 9th cousins. They shared an ancestor in King Philip III of France and his wife Maria of Brabant, who were both Boleyn and Cleves’ 8th great-grandparents. Philip III was also the 8th great-grandfather of Cleves via his other wife, Isabella of Aragon.

- They were also 8th cousins 1x removed via King Edward I of England and Eleanor of Castile, who were Boleyn’s 7th great-grandparents and Cleves’ 8th. Edward I was also the 7th great-grandfather of Boleyn via his other wife, Margaret of France.

Boleyn and Howard

- Boleyn and Howard were cousins. They shared grandparents: Thomas Howard and Elizabeth Tilney. Boleyn’s mother, Lady Elizabeth Boleyn, and Howard’s father, Lord Edmund Howard, were siblings.

Boleyn and Parr

- Boleyn and Parr were 4th cousins 1x removed. They shared ancestors in John Montagu (3rd Earl of Salisbury) and his wife Maud Francis, who were Boleyn’s 3rd great-grandparents and Parr’s 4th.

Seymour and Cleves

- Seymour and Cleves were 7th cousins 1x removed via William I, Count of Hainaut, and his wife Joan of Valois, who were Seymour’s 7th great-grandparents and Cleves’ 6th.

- They were also 9th cousins via King Philip IV of France and his wife Joan I, Queen of Navarre, who were their 8th great-grandparents.

Seymour and Howard

- Seymour and Howard were 2nd cousins. They shared an ancestor in Elizabeth Cheney, who was their great-grandmother, but they were descended from children of different husbands - Howard from Sir Frederick Tilney and Seymour from Sir John Say. This made their grandmothers, Elizabeth Tilney and Anne Say, half-sisters.

Seymour and Parr

- Seymour and Parr were 6th cousins. They shared 5th great-grandparents: Ralph Neville (2nd Baron Neville) and Alice de Audley.

- After Henry VIII’s death, Parr married Seymour’s brother.

Cleves and Howard

- Cleves and Howard were 8th cousins 1x removed. They shared common ancestors in King Edward I of England and his wife Eleanor of Castile, who were Cleves’ 8th great-grandparents and Howard’s 7th. Howard was also descended from a child of Edward I and his other wife, Margaret of France.

- They were also 9th cousins via King Philip III of France and his wife Maria of Brabant, who were both Cleves and Howard’s 8th great-grandparents. Cleves was also descended from a child of King Philip and his other wife, Isabella of Aragon.

Cleves and Parr

- Cleves and Parr were 7th cousins. They were both descended from William I Count of Hainaut and his wife Joan of Valois, who were their 6th great-grandparents.

Howard and Parr

- Howard and Parr were 6th cousins. They shared ancestors in Richard FitzAlan, 3rd Earl of Arundel, and his wife Eleanor of Lancaster, who were their 5th great-grandparents.

#six the musical#catherine of aragon six#catherine parr six#anne boleyn six#anna of cleves six#jane seymour six#katherine howard six#six musical#misc#six history#my post

54 notes

·

View notes

Text

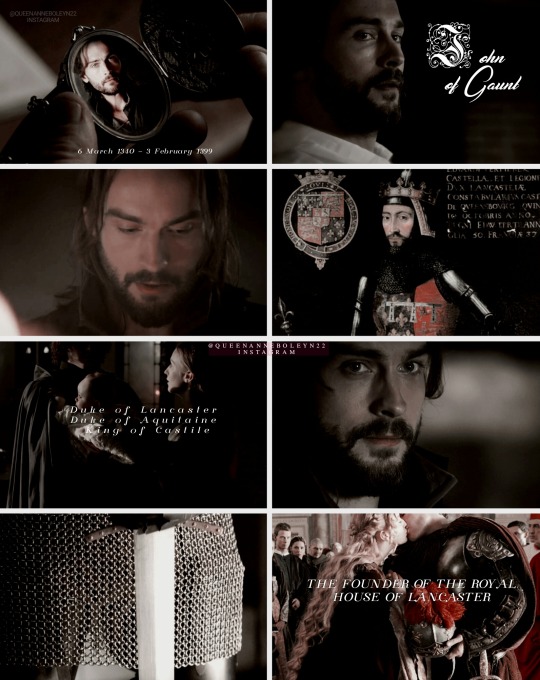

John of Gaunt, duke of Lancaster, also called (1342–62) earl of Richmond, or (from 1390) duc (duke) d’Aquitaine, (born March 1340, Ghent—died Feb. 3, 1399, London), English prince, fourth but third surviving son of the English king Edward III and Philippa of Hainaut; he exercised a moderating influence in the political and constitutional struggles of the reign of his nephew Richard II. He was the immediate ancestor of the three 15th-century Lancastrian monarchs, Henry IV, V, and VI. The term Gaunt, a corruption of the name of his birthplace, Ghent, was never employed after he was three years old; it became the popularly accepted form of his name through its use in Shakespeare’s play Richard II.

Through his first wife, John, in 1362, acquired the duchy of Lancaster and the vast Lancastrian estates in England and Wales. From 1367 to 1374 he served as a commander in the Hundred Years’ War (1337–1453) against France.

Meanwhile, in England, war had nearly broken out between the followers of King Richard II and the followers of Gloucester. John returned in 1389 and resumed his role as peacemaker.On his return he obtained the chief influence with his father, but he had serious opponents among a group of powerful prelates who aspired to hold state offices. He countered their hostility by forming a curious alliance with the religious reformer John Wycliffe. Despite John’s extreme unpopularity, he maintained his position after the accession of his ten-year-old nephew, Richard II, in 1377, and from 1381 to 1386 he mediated between the King’s party and the opposition group led by John’s younger brother, Thomas Woodstock, earl of Gloucester.

In 1386 John departed for Spain to pursue his claim to the kingship of Castile and Leon based upon his marriage to Constance of Castile in 1371. The expedition was a military failure. John renounced his claim in 1388, but he married his daughter, Catherine, to the young nobleman who eventually became King Henry III of Castile and Leon.

His wife Constance died in 1394, and two years later he married his mistress, Catherine Swynford. In 1397 he obtained legitimization of the four children born to her before their marriage. This family, the Beauforts, played an important part in 15th-century politics. When John died in 1399, Richard II confiscated the Lancastrian estates, thereby preventing them from passing to John’s son, Henry Bolingbroke. Henry then deposed Richard and in September 1399 ascended the throne as King Henry IV.

Source: britannica.com

#perioddramaedit#history#edit#history edit#john of gaunt#john of gaunt and katherine swynford#14th century#middle age#medieval history#english history#richard ii#historical figures#tom mison#fancast#katherine swynford#constance of castile#house of lancaster#lancaster#philippa of hainault#edward iii

107 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Mary of Avesnes (or Marie de Hainaut;1280 – 1354) was the daughter of John II, Count of Holland and Philippa of Luxembourg. In 1310 she married Louis I, Duke of Bourbon, son of Robert, Count of Clermont and Beatrix of Bourbon. They had eight children.

#marie de hainaut#marie d'avesnes#royaume de france#maison de bourbon#county of holland#the netherlands

1 note

·

View note

Quote

Eleanor of Aquitaine, Eleanor of Castile (d. 1290), and Philippa of Hainaut (d. 1369) were buried in the same churches as their husbands and near them, but not in the same tombs with them. While double monuments for aristocratic couples appeared in England around the mid-fourteenth century, it was only with Anne of Bohemia (d. 1394) and Richard II (d. 1400) that a double royal tomb was commissioned; this fashion prevailed for the surviving royal monuments of the later medieval period - Henry IV (d. 1413) and Joan of Navarre (d. 1437) at Canterbury, and Henry VII (d. 1509) and Elizabeth of York (d. 1503) at Westminster Abbey.

John Cami Parsons, 'Never was a body buried in England with such

solemnity and honour': The Burials and Posthumous Commemorations of English Queens to 1500.

#richard and anne commissioned the first couple tomb... wah#richard ii#anne of bohemia#henry vii#elizabeth of york#henry iv#joan of navarre#plantagenet tag#also#tudor tag

67 notes

·

View notes

Photo

24 June? 1313/15 ✧ Philippa of Hainault was born in Valenciennes in the County of Hainaut as the fourth daughter of William I, Count of Hainaut and Joan of Valois, who was the granddaughter of Philip III of France. In the year of 1328 Philippa married Edward III, King of England and bore thirteen children, through the course of twenty-five years. Nine of the children survived past infancy and five were living sons whose descendants would bring about the long-lasting dynastic wars known as the Wars of the Roses.

Few, if any, Queen consorts of England have left behind them so noble and distinguished a record as Philippa of Hainault. From the days when she was a schoolgirl at Valenciennes to the hour when she died, a tired woman, at Windsor forty-three years later, she was the good angel of Edward and of England. All the years of her life, and they were fifty-six, she had worked faithfully and untiringly for those dear to her, nor did her labours cease when failing health, sorrow, bereavement and disillusion darkened her path. A true Mother of her people, through the most difficult period of history she held the balance even between duty and inclination; nor did she win the less love because, with all her kindness, she was never weakly indulgent to follies, her own or others’. The few murmurs that rose against her have been mentioned, and in a great measure explain themselves: she was a woman of business, and against such the unbusiness like will ever rebel. – Blanche Christabel Hardy (Philippa of Hainault and Her Times)

#historyedit#on this day in history#philippa of hainault#<3#14th century#medieval history#history#english history#edward iii#house of plantagenet#house of avesnes#queens#happy 705th birthday#our darling <3#our gifs#our creations

505 notes

·

View notes

Text

I’m over 100 pages into The King’s Concubine and:

Alice Perrers is about to bone Edward III

Alice is basically very hard-done-by. She’s an orphan who was abandoned in a nunnery and the nuns are all horrible people who beat her

(I have the sneaking suspicion that O’Brien is going to give Alice an outlandish parentage and be like “Isabella of France and Roger Mortimer’s love child! Secret incest!”)

one time Joan of Kent came to visit her and was horribly nasty to her so Alice is all “Joan the Fair! Joan the Fat!”

and then she’s sent off to marry Jamyn Perrers who has a nasty sister who treats Alice like a slave and strips the household when Jamyn dies from the plague that only Alice nursed him through and Alice is forced to go back to the nunnery

also for some reasons, never clarified beyond “he didn’t want to marry, he just wanted to stop his sister from nagging him”, Jamyn doesn’t consummate the marriage

but don’t worry, Philippa of Hainaut turns up to the nunnery and Alice proves herself by helping Philippa up when she’s fallen and picking up her rosary [sic] beads so Philippa adopts her

and then when Alice arrives in the royal household, Philippa is too sick to see her so Philippa’s nasty daughter, Isabella, sends Alice to be a kitchen maid

(why do people act like medieval women were helpless pawns and then find a woman who had some control over their marriages were spoilt bitches?)

and then she’s bullied and sexually harassed and then accused of stealing the rosary [sic] Philippa gave her and no one believes her but Philippa saves the day by rising from her sickbed

so now Philippa has made Alice a lady-in-waiting and now it’s all “omg she has amazing clothes now!” and she gets to hang out with the king and she’s got an instant connection with Edward III, who is old but still 10/10 would bang (unlike Philippa)

and then Edward III summons Alice to have sex with him and Alice goes but she’s wracked with guilt

BUT THEN PHILIPPA TURNS UP WHILE ALICE IS WAITING TO SEE EDWARD.

Alice is all “oh noo I’m not going to do it, I’m crying, I’m guilty, I can’t do it to you” and Philippa is like “hush child, I’m only here to tell you that I understand my husband has needs and I can’t fulfil them so I picked you with the express purpose of having you fuck my hubby now go forth with my blessing”

(and like yeah, it is fair that they have this conversation. Philippa is very sickly. But it also removes all guilt from Alice, prevents Philippa being the victim of her husband’s affair and casts Philippa in a quite manipulative light, almost to the point of presenting her as grooming Alice for Edward III and I just YIKES.)

but no one can know Alice has Philippa’s blessing so the man who takes Alice to see Edward III after this conversation is furious with Alice

and now Alice is about to bang Edward III.

#lisa reads anne o'brien#tw grooming#what did philippa of hainault ever do to you#like ok i'm just a bit... oh at this casting of philippa's role in the edward/alice affair#given it was framed as expressly insulting to philippa (or her memory) so like#she's not only ok with it but in fact engineered it!#just removes alice's guilt and wrongdoing#in a novel that's already laying it on with a towel how sad and pathetic and victimised alice is#also after the king's mistress by emma campion#i'm not very impressed with the attiude that alice did nothing wrong she's the real victim here!#(i am also uncomfortable with my reaction given i've played with something similar for eleanor and humphrey's affair)

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Favorite History Books || Three Medieval Queens: Queenship and the Crown in Fourteenth-Century England by Lisa Benz St. John ★★★★☆

Edward III intended to bury his consort with all the honor suitable for a member of the royal family. Philippa was interred in Westminster Abbey, following the observance of her wedding anniversary. The death of Philippa marked the end of a 70-year period in which the practice of queenship was continuous. There would not be another queen for 13 years, and in that time it seems as if the practice of queenship began to change.

But what did it mean to be a queen in the fourteenth century? This book has shown that the queen held a place all her own, which was determined by her gender, her status, and her role in the royal family. Gender and status were inextricably linked because her gender made her a wife and mother to kings, and these roles dictated her place within medieval society. Consequently, her place in the social structure was determined by the biological aspects of gender. Gender enabled all women to become mothers because the biology of pregnancy and birth, and the symbolic power gained from those characteristics, belonged only to women. Nevertheless, the agency employed in transforming ascribed power to achieved power was not necessarily gendered. Kings utilized their children in dynastic maneuverings in the same way that queens could use their children to spread their influence, secure their authority, or even govern in the absence of the king. Likewise, the ideological emphasis on intercession and influence was also a consequence of gender roles. Both men and women acted as intercessors, but it was a duty especially emphasized for women because sometimes it was the primary avenue open to them. Since queens did not consistently hold positions within government—they did not always act as an administrator for the king—intercession was one way queens could have a significant impact on political activity. Similarly, noblewomen did not always hold their land in jointure, so they too interceded in this way with their husbands. Men, on the other hand, could not only intercede with the king, but also had many more opportunities for roles in government.

However, this is where the queen’s similarity to other noblewomen— her closest female equivalents—ends. The independence associated with her status was different from that of her other female counterparts. She received her lands through her marriage, and she held those lands in the same way as a male lord who held a life grant from the king. Holding land in the same way as a male head of household meant that the king could not interfere with the queen’s landholdings to any greater extent than he did with those of other noblemen who held land from him. It was the queen’s status as an independent landlord that allowed her to execute her authority over the administration of her household and estates. As a lord, the queen extended her patronage through appointments on her estates and in her household. Other married women of the landed elite were not able to exercise this level of direct authority over their estates because they held them jointly with their husbands. It is tempting to assume that jointure gave women equal authority on these estates, but this was not the case. Holding land in jointure with one’s husband did not automatically designate the wife as an equal partner in administering land. The common law prevented married women from controlling real and moveable property or any income from these lands during their marriages. Noblewomen only managed estates in their husband’s absence, or as widows.

However, being the king’s wife meant that the queen enjoyed privileges that even the earls did not. She had access to the king and crown, which she could manipulate to increase her influence and authority. When she could not use her land as a source of patronage, she could extend her patronage through intercession with the crown. All members of the upper echelons of medieval society acted as intercessors; it was part of being a good lord. Nevertheless, because her husband was the king, intercession gave the queen access to the most important sources of patronage in the realm. She also had the full backing of the crown’s apparatus behind her, making her one of the most formidable magnates. When Philippa came into financial difficulties, she could call upon the king’s resources to relieve her of her debts. When there were complaints against Isabella’s ministers, they had to be brought before the king’s council instead of the common law courts. Her status as the king’s wife also put her in standing to hold positions in the royal government. The queen had to be expressly appointed to some positions, such as keeper of the great seal. On the other hand, other positions, such as keeper or administrator of the realm, were inherent to the office of queenship and did not require articulation. In these terms, her gender and her status were not limiting. They allowed her the potential to be the most privileged woman and one of the most advantaged among the male landed elite. The only other male members of elite society who might have had similar prerogatives were the other members of the royal family.

#historyedit#litedit#margaret of france#isabella of france#philippa of hainaut#house of plantagenet#house of capet#house of flanders#french history#english history#medieval#women's history#european history#history#history painting#nanshe's graphics

70 notes

·

View notes

Note

Why does Queen Alysanne look so different from her siblings and parents? She has blue eyes and blond hair instead of purple eyes and silver hair. I highly doubt she's a bastard, but I feel like there must be a reason for her distinct coloring? Thank you!

Well, to be pedantic about it, we’re not certain what all of Alysanne’s siblings looked like. We have a good idea about Jaehaerys and Rhaena of course, and given that at 15 Aegon the (future) Uncrowned “was said by many to be the very image of his grandsire at the same age”, it may be worth guessing that he shared the silver-gold hair and purple eyes of Aegon the Conqueror. However, we don’t have any idea what Prince Viserys looked like, nor the short-lived Princess Vaella, so it is entirely possible that they shared Alysanne’s honey-colored curls and/or blue eyes. Nor should we necessarily assume that Alysanne’s looks were entirely non-Valyrian, or owed nothing to her Targaryen/Valyrian heritage: after all, Gyldayn later goes on to describe Moredo Rogare as looking like “the very image of a warrior of Old Valyria” in part because of his “blazing blue eyes”, while Daenerys’ Lysene handmaiden Doreah is described as having “hair the color of honey, and eyes like the summer sky”.

Anyway, to the extent GRRM wanted Alysanne to look less obviously Targaryen/Valyrian than her two longest-surviving siblings, perhaps GRRM depicted her this way to show Alysanne as more in touch with the common people of Westeros, befitting her eventual “good queen” moniker. As Alysanne looked less strikingly, indeed inhumanly beautiful than the common image of the Targaryens, so, perhaps, her appearance embodied the bridge she encouraged (through her good works and intercession with the king) between crown and people. Maybe the suggestion is supposed to be that Alysanne was not a faraway god-like figure who did not care for her people, but a queen who, for example, wished to hear the injustices of the women in her realm, end the terror of the right of the first night, and provide the citizens of her capital with clean water. But that’s just a guess, of course.

I also wonder the extent to which GRRM is again drawing from The Accursed Kings. (I know, it me.) Since I think Jaehaerys I in F&B pulls quite a bit from Druon’s depiction of King Edward III of England, it would hardly surprise me that GRRM would also be thinking about Edward’s (sometime) beloved bride, Philippa of Hainaut, when detailing Alysanne. While I don’t think personality-wise Druon’s Philippa and F&B’s Alysanne have much in common - Philippa is indeed barely a character in The Accursed Kings, likely a surprise to no one in that misogynistic series - and they don’t in fact look particularly similar, Druon is very insistent that the readers see his Philippa as not particularly beautiful (indeed referring to her multiple times as “chubby”, “stout”, and “fat”, and never as a compliment). More to the point, when Philippa marries Edward, Druon notes that while Philippa “was not even very pretty ... she had an attractive simplicity”, as “[w]ithout her royal adornments, she would have looked no different from any other red-headed girl of her age”; accordingly, in Druon’s opinion, Philippa “was essentially no different from the women over whom she was to reign”, and “[e]very stout, red-headed girl felt that she had, somehow or other, been personally complimented and honoured” as Philippa was made the king’s wife. (Did I mention how problematic this series is?) So maybe Alysanne being “oft described as pretty but seldom as beautiful”, yet nevertheless being mutually in love with her fair young king, is meant to recall this distinctly un-beautiful (in Druon’s opinion, anyway) princess falling mutually in love with her fair young king.

63 notes

·

View notes

Photo

On This Day In History

.

24th January 1328

.

.

Edward III married Phillipa of Hainault.

.

.

◼ Edward married his cousin, Phillipa of Hainault, granddaughter of Phillip III of France. .

.

◼ The marriage had been negotiated by Edward’s mother, Isabella, in the summer of 1326, Isabella, who was estranged from her husband, Edward II, visited the Hainaut court, along with Prince Edward, to obtain aid from Count William to depose King Edward in return for the couple’s betrothal.

.

▪ After a dispensation had been obtained for the marriage of the cousins (they were both descendants of Philip III), Philippa arrived in England in December 1327 escorted by her uncle, John of Hainaut.

.

◼ The marriage, celebrated at York Minster on 24th January, 1328, was a happy one, the two became very close & produced a large family. .

.

▪ Phillipa was kind & inclined to be generous & exercised a steadying influence on her husband. Their eldest son Edward, later known as the Black Prince, was born on 15th June 1330, when his father was eighteen. Phillipa of Hainault was a popular Queen Consort, who was widely loved & respected, & theirs was a very close marriage, despite Edward’s frequent infidelities. She frequently acted as Regent in England during Edward’s absences in France.

.

▪ Edward & Phillipa produced twelve children in all, among them were John of Gaunt, later the 1st Duke of Lancaster, (father of King Henry IV)

.

.

.

#OnThisDayInHistory #ThisDayinHistory #TheYear1328 #History #Heritage #RoyalWedding #EdwardIII #King #KingEdwardIII #HouseofPlantagenet #Plantagenets #Medieval #Monarchy #KingofEngland #EnglishMonarchy #QueenConsort #PhillipaofHainault #D24jan #Plantagenet #onthisday #theking #kingandqueen #Royalhistory (at York Minster)

https://www.instagram.com/p/B7tQFEMgqU-/?igshid=u45lp33b6hw6

#onthisdayinhistory#thisdayinhistory#theyear1328#history#heritage#royalwedding#edwardiii#king#kingedwardiii#houseofplantagenet#plantagenets#medieval#monarchy#kingofengland#englishmonarchy#queenconsort#phillipaofhainault#d24jan#plantagenet#onthisday#theking#kingandqueen#royalhistory

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Marie of Hainaut (1280 – 1354) was the daughter of John II, Count of Holland and Philippa of Luxembourg, and her brother was William I, Count of Hainaut.

6 notes

·

View notes

Photo

historicwomendaily celebration week : Favorite consorts

Theodora (c. 500 – 28 June 548) was empress of the Eastern Roman Empire by marriage to Emperor Justinian I.

Philippa of Hainault (Middle French: Philippe de Hainaut; 24 June c.1310/15 – 15 August 1369) was Queen of England as the wife of King Edward III.

Elizabeth Woodville (also spelled Wydville, Wydeville, or Widvile) (c. 1437 – 8 June 1492) was Queen consort of England as the spouse of King Edward IV from 1464 until his death in 1483.

Catherine of Aragon (Spanish: Catalina; 16 December 1485 – 7 January 1536) was Queen of England from June 1509 until May 1533 as the first wife of King Henry VIII.

Anne of Austria (22 September 1601 – 20 January 1666), a Spanish princess of the House of Habsburg, was queen of France as the wife of Louis XIII, and regent of France during the minority of her son, Louis XIV, from 1643 to 1651.

Maria Feodorovna (26 November 1847 – 13 October 1928), known before her marriage as Princess Dagmar of Denmark, was a Danish princess and Empress of Russia as spouse of Emperor Alexander III

#historyedit#history#perioddramaedit#historicwomendaily#elizabeth woodville#catherine of aragon#philippa of hainault#anne of austria#empress theodora#maria feodorovna#vikings#the hollow crown#the white queen#borgia#the musketeers#anna karenina 2017#my edit

574 notes

·

View notes

Note

Fancast meme!!!!!! Hmmmmm Philippa of Hainaut maybe?? :D

other people have said this but I really love Angel Coulby :)

2 notes

·

View notes