#operation herrick

Text

A Harrier waits in a hangar at Kandahar, Afghanistan prior to departure. 1(F) Squadron marked the end of Harrier air operations in Afghanistan in June 2009, five years after RAF and Royal Navy pilots first engaged the Taliban in Operation HERRICK.

@ron_eisele via X

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

6 November 2013

The Duchess of Gloucester presents campaign medals to soldiers attached to 1 Mechanized Brigade following their recent tour of duty in Afghanistan during Operation Herrick 18, as they parade at Picton Barracks, Bulford, Wiltshire. (The Royal Family)

“9 years ago today with HRH The Duchess of Gloucester receiving my Afghanistan medal. Pretty sure I wasn't meant to shake her hand but I went for it anyway 😁”

— Sarah Taylor (posted 9 January 2023)

25 notes

·

View notes

Photo

LIRR Herricks Road, View E, M3 EB, April 12, 1998

"HERRICKS ROAD CROSSING"

View east at the temporary Herricks Road crossing as the gates are down as an eastbound M3 train crosses Herricks Road.

This photo was taken of the once notorious grade crossing at Herricks Road, one week before the cutover of the grade crossing elimination. The new LIRR overpass has been completed along with track and signals. In a week the temporary grade crossing will be eliminated and trains will run over the new structure, eliminating this heavily trafficked highway/rail crossing. On March 15, 1982 a van with 10 teenagers returning to their homes, after a night of partying, drove around the already down crossing gates and were hit by an oncoming LIRR train. Only one survived.

This was always a particularly dangerous crossing as LIRR trains operated at maximum speed (79mph for electric trains/64mph for diesel hauled trains), and vehicle traffic was also very heavy, with two lanes of traffic in each direction. In addition the track level was higher than the highway and site distances very poor for vehicle drivers. Even without the events of March 15th, the grade crossing was one that needed to be eliminated.

#commuter train#lirr#long island rail road#mta#metropolitan transportation authority#1998#trains#passenger train#history#mineola#new york

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

DOMINION REPRESENTES BUYER IN THE PURCHASE OF FORMER HOSPITAL IN TECUMESH, MICHIGAN

Bingham Farms, MI (February 2024) - James Mitchell, Vice President of Brokerage at Dominion Real Estate Advisors, LLC. (DRA) represented the purchaser, Greater Midwest Group, LLC in the sale transaction of the former Herrick Memorial Hospital property located at 500 E Pottawatamie St., Tecumseh, MI. Herrick Memorial Hospital operated as a 50-bed, full-service, acute-care hospital that closed in September of 2020. The new owner of the property will use this 188,179 SF property as a Behavioral Health facility.

ABOUT DOMINION REAL ESTATE ADVISORS

Dominion Real Estate Advisors (DRA) is a full service commercial real estate firm recognized nationally as a leading provider of professional commercial real estate services. DRA brings decades of experience and expertise in commercial brokerage, property and asset management, real estate advisory, construction, design, and development services.

DRA is committed to bringing its clients creative, cutting-edge solutions, and providing the highest level of professional service fostering long lasting relationships based on loyalty, integrity, and trust. DRA assists corporate clients, lenders, institutions, property owners, investors, and real estate developers in achieving their real estate objectives.

To read about the lease transaction with RoboVent, posted by Crain’s Detroit Business click here: https://dominionra.com/news.php/736627861047394304

For more information, please visit:

LinkedIn: https://www.linkedin.com/company/dominionra

Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/dominion_realestateadvisors

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/dominionra/

0 notes

Text

Frontier Resilience: Rising Against Adversity in the Fight for Homeland Security

As homeland security is evolving each day, resilience is key to overcoming adversity and safeguarding our nations. From combating terrorism to responding to natural disasters, the frontier of homeland security highlights many challenges that demand innovative solutions and determination.

This article will help you understand how resilience plays a key role in the ongoing fight for homeland security.

Understanding the Frontier of Homeland Security:

Homeland security includes many threats and hazards that endanger the safety and well-being of our communities. These threats range from traditional concerns such as terrorism and border security to emerging challenges like cyber threats and pandemics.

It is important to understand the frontier of homeland security that requires a comprehensive approach addressing both known and risks.

Strategies for Overcoming Adversity in Homeland Security:

Resilience serves as a guiding principle in homeland security efforts. There are many strategies, like proactive risk assessment and mitigation, robust emergency preparedness and response plans, and investments in technology and infrastructure that can help enhance security capabilities.

To build resilience and effectively counter threats, it is essential to promote collaboration and coordination among government agencies, private sector partners, and community stakeholders.

Advancing Frontier Resilience in Homeland Security:

Advancing frontier resilience in homeland security requires a continuous cycle of learning, adaptation, and innovation. It includes cutting-edge technologies like artificial intelligence, data analytics, and predictive modeling to anticipate and respond to evolving threats.

Investing in training and capacity-building programs for first responders and emergency personnel enhances readiness and ensures an effective response to crises. By embracing a forward-thinking mindset and embracing new approaches, we can strengthen our resilience against threats to homeland security.

Triumphs in the Fight for Homeland Security:

Despite the challenges, there have been numerous triumphs in the ongoing fight for homeland security. From terrorist plots to successfully responding to natural disasters, these challenges highlight the resilience and dedication of those working tirelessly to keep our communities safe. From the heroic efforts of first responders, the innovative solutions developed by security professionals serve as a beacon of hope and inspiration amidst adversity.

Are you ready to work together to safeguard the homeland, ensuring the resilience of our communities? Jim Herrick, a seasoned Border Patrol veteran, takes readers on a gripping journey through the complexities of border security in 'War on the Rio Grande: Laredo Under Fire.' , this literary gem not only unravels high-stakes action but also sheds light on the diverse careers of Border Patrol veterans.

The narrative follows Kelly Smith, a battle-hardened Border Patrol agent, as he confronts a grand conspiracy to breach the U.S./Mexican border. Herrick's firsthand experience as a 25-year Border Patrol veteran and his stint as a mentor in Afghanistan lend authenticity to the plot, making it a compelling and insightful read.

The book 'War on the Rio Grande: Laredo Under Fire,' delves into the challenges faced by Border Patrol families, recognizing their unsung contributions. It highlights the strength and unity of these hidden heroes who form the backbone of the operation, providing unwavering support to those on the frontlines.

Dive deep into this thought-provoking and compelling narrative by ordering your copy of 'War on the Rio Grande: Laredo Under Fire' from Amazon today!

1 note

·

View note

Text

Events 10.27 (after 1940)

1944 – World War II: German forces capture Banská Bystrica during Slovak National Uprising thus bringing it to an end.

1954 – Benjamin O. Davis, Jr. becomes the first African-American general in the United States Air Force.

1958 – Iskander Mirza, the first President of Pakistan, is deposed by General Ayub Khan, who had been appointed the enforcer of martial law by Mirza 20 days earlier.

1961 – NASA tests the first Saturn I rocket in Mission Saturn-Apollo 1.

1962 – Major Rudolf Anderson of the United States Air Force becomes the only direct human casualty of the Cuban Missile Crisis when his U-2 reconnaissance airplane is shot down over Cuba by a Soviet-supplied surface-to-air missile.

1962 – By refusing to agree to the firing of a nuclear torpedo at a US warship, Vasily Arkhipov averts nuclear war.

1964 – Ronald Reagan delivers a speech on behalf of the Republican candidate for president, Barry Goldwater. The speech launches his political career and comes to be known as "A Time for Choosing".

1967 – Catholic priest Philip Berrigan and others of the 'Baltimore Four' protest the Vietnam War by pouring blood on Selective Service records.

1971 – The Democratic Republic of the Congo is renamed Zaire.

1979 – Saint Vincent and the Grenadines gains its independence from the United Kingdom.

1981 – Cold War: The Soviet submarine S-363 runs aground on the east coast of Sweden.

1986 – The British government suddenly deregulates financial markets, leading to a total restructuring of the way in which they operate in the country, in an event now referred to as the Big Bang.

1988 – Cold War: Ronald Reagan suspends construction of the new U.S. Embassy in Moscow due to Soviet listening devices in the building structure.

1991 – Turkmenistan achieves independence from the Soviet Union.

1992 – United States Navy radioman Allen R. Schindler, Jr. is murdered by shipmate Terry M. Helvey for being gay, precipitating debate about gays in the military that results in the United States' "Don't ask, don't tell" military policy.

1993 – Widerøe Flight 744 crashes near Overhalla, Norway, killing six people.

1994 – Gliese 229B is the first Substellar Mass Object to be unquestionably identified.

1995 – Former Prime Minister of Italy Bettino Craxi is convicted in absentia of corruption.

1997 – The 1997 Asian financial crisis causes a crash in the Dow Jones Industrial Average.

1999 – Gunmen open fire in the Armenian Parliament, killing the Prime Minister and seven others.

2014 – Britain withdraws from Afghanistan at the end of Operation Herrick, after 12 years four months and seven days.

2017 – Catalonia declares independence from Spain.

2018 – A gunman opens fire on a Pittsburgh synagogue killing 11 and injuring six, including four police officers.

2018 – Leicester City F.C. owner Vichai Srivaddhanaprabha dies in a helicopter crash along with four others after a Premier League match against West Ham United at the King Power Stadium in Leicester, England.

2019 – Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant founder and leader Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi kills himself and three children by detonating a suicide vest during the U.S. military Barisha raid in northwestern Syria.

0 notes

Text

AIRFIX - A03702 - British Forces Vehicle Crew "Operation Herrick Afghanistan" - 1/48

Plastic Model Kit - 8 Multi-part Figures

0 notes

Link

[ad_1] Queues formed at ATMs on Tuesday night when a technology issue at Bank of Ireland allowed customers to withdraw or transfer funds beyond their limits. Bank of Ireland has told customers that the money withdrawn during the blunder will be debited. Speaking to Morning Ireland, ICCL Executive Director Liam Herrick said: "The starting point is that if the guards are involved in an operation that restricts people’s rights, restricts people’s movement and their ability to access finance for example, they must have a clear basis for it and they must be clear about what that basis is.”He said gardaí responded to the events as part of a “public order operation,” adding: “If that is the case, then I think it needs to be compared with the general public concern at the moment – and a real problem also – about unresponsiveness and ineffectual responses to serious public order issues in Dublin city in particular."So, when the guards are saying that they received a number of calls from members of the public and then deployed a significant number of guards to engage in an operation – what was the risk assessment there? What information did they have that there was a serious public order risk and did it require the deployment of guards directly onto the streets?Mr Herrick said more information is required on the “phone calls between Bank of Ireland and An Garda Síochána” that night."We know that Bank of Ireland themselves have said that there was dialogue between the bank and An Garda Síochána over the course of that evening. They say that they didn’t make a request for assistance, but they didn’t say that there was a subsequent decision to deploy the guards.”He added there is potentially “public concern” in the aftermath of the incident."We’ve seen that there are serious crimes, serious assaults, life-threatening assaults occurring in the Templebar area and the north inner city area,” Mr Herrick said."We can only assume that there were significant calls from businesses and community organisations in those areas on a regular basis, which the public don’t really feel receive the same level of response.”He added there are also “questions” about what happened when gardaí attended the scene at a number of ATMs across the country earlier this week."There’s images and footage out there of guards parking garda vehicles to block people accessing ATM machines and physically blocking those ATM machines themselves."Now, there’s no clear indication about what the legal basis for that would be,” he said, adding that he believes the gardaí have been drawn into “civil law matters.”"We have in this instance one particular financial institution having a security problem itself. We know that they contacted the guards and we then have a significant deployment of guards.”He said “questions do arise” when the public perception is that similar levels of deployment are not being taken when “serious assaults are taking place.”Mr Herrick added that it would be “helpful” for the Commissioner to provide more information about the risk assessment involved."I think we need a full report of exactly what happened here. We don’t even know, for example, from Bank of Ireland how much money was withdrawn illegitimately in the first place but I think there is a wider concern here about the transparency around policing and the legal basis for the guards being involved in civil matters.”He said in that context, the public have “legitimate concerns” about the situation. [ad_2]

0 notes

Text

Registration opens the NALPs Elevate 2023 show in Dallas

If you live in Pensacola, it's just a matter of time that you have to do the inevitable and remove a tree.

Tree Services Pensacola is a tree removal company that specializes in stump grinding, tree removal, and arborist services. They have been in business for over 10 years and have the experience and expertise to get the job done right. Fully licensed and insured, so you can rest assured that your property is in good hands.

Pensacola tree service is a company that specializes in removing trees. They have been doing this for over 10 years and they are really good at it. They also do stump grinding, which means they get rid of the stump left behind after the tree is removed. They are fully licensed and insured, so you can be sure that your property is in good hands.

The LM team including Publisher Bill Roddy, Jones, Editor Christina Herrick and Associate Publisher Craig MacGregor were on hand for Elevate 2022 in Orlando. (Photo: LM Staff)

The National Association of Landscape Professionals (NALP) opened registration for its annual conference and expo, Elevate. The event will take place Sept. 10-13 at Gaylord Texan Resort & Conference Center in Grapevine, Texas.

Elevate is the national conference and expo for landscape maintenance, design/build, lawn care, irrigation and horticulture professionals offering management-level education and networking and peer learning.

“The attendee reviews and feedback from the first Elevate conference were exceptional — like nothing I’ve seen for a new conference in my decades in association management,” said Britt Wood, NALP CEO. “We are thrilled to deliver such an inspiring, fun, and exciting conference and expo experience that enlightens and accelerates growth for attendees.”

The event’s education will focus on four key areas: team building (recruiting, retaining and developing employees), customer service and the customer experience, business and finance and operations. Elevate is designed for industry CEOs, decision-makers and key management staff members.

“Elevate is all about building connections with the best in the business,” said Wood. “Elevate brings together some of the top company owners, CEOs, directors, managers, HR and sales professionals to share their knowledge.”

Visit here to learn more and register for this year’s event. Register before June 15 to secure the best rate. Hotel rooms at the Gaylord Texan can only be booked after registering for the event. Companies bringing ten or more attendees receive the lowest registration rates.

The inaugural Elevate 2022 saw more than 1,500 attendees gather at the Gaylord Palms Resort & Convention Center in Kissimmee, Fla.

0 notes

Text

From ALS treatment to a historic transplant: The biggest medical breakthroughs of 2022

When COVID-19 arrived in the United States, it was all hands on deck. The country’s brightest scientific minds dropped whatever they were doing to join the effort against SARS-CoV-2, developing novel vaccines and treatments in record time.

In 2022, researchers had time to resume projects they were forced to put on hold, and the USA TODAY health team has spent the year reporting on novel procedures, medical discoveries, and advances in disease prevention and treatment.

Some highlights: Scientists completed the map of our DNA. The FDA approved the first new ALS drug in five years. And we reached major milestones in organ transplantation.

Below, read about some of the biggest medical breakthroughs of 2022, plus a preview of what's in store for 2023.

First pig-to-human heart transplant

In January, David Bennett Sr., 57, became the first patient to have a heart transplant using a pig heart. In the nine-hour operation, doctors at the University of Maryland Medical Center replaced his heart with one from a 240-pound pig that had been gene-edited and bred specifically for this purpose.

The procedure was initially considered a success, but Bennett died two months later. Doctors said his death may have been partially the result of a virus he contracted from the pig heart, called pig cytomegalovirus, or CMV.

But health experts hold out hope for xenotransplantation, which is the transplantation of organs or tissues from an animal into a human. More than 100,000 people are waiting for organ transplants, and many never qualify.

US marks 1 million successful organ transplants

In September, the United States marked its 1 millionth successful solid-organ transplant.

The first organ transplant was in 1954 when Richard Herrick, 23, received a kidney from his twin, Ronald.

Half of the country’s million transplants came during the 53 years after Herrick’s surgery and half in just the past 15 years, according to the data from the nonprofit United Network for Organ Sharing.

In 2021, for the first time, more than 40,000 solid organs – more than 100 a day – were transplanted. At that pace, the next 1 million transplants will take only 25 years – and probably far less because of medical innovations under development, said David Klassen, the network's chief medical officer.

Delaying Type 1 diabetes

In November, the Food and Drug Administration approved a monoclonal antibody, called teplizumab, that could delay the onset of Type 1 diabetes for years. Under the brand name TZIELD, the treatment is a 14-day, 30-minute infusion for adult and children 8 years and older with Stage 2 Type 2 diabetes.

In the three stages of Type 1 diabetes, Stage 2 is one step before clinical diagnosis. In clinical trials, teplizumab delayed the onset of Stage 3 diabetes for about two years compared with the placebo.

Although health experts called the treatment “game-changing,” it comes with a price. The cost is $13,850 a vial for a total of $193,000 over the 14-day treatment. A study published in October found more than 1.3 million adults in the U.S. skipped doses, delayed buying or otherwise rationed the lifesaving medication insulin because of its cost.

Mapping out the human genome

Scientists finally finished mapping the human genome, more than two decades after the first draft was completed.

About 8% of genetic material had been impossible to decipher with previous technology.

It will be years before there’s a concrete payoff to that additional information, researchers said, but those previously missing bits could offer insights into human development, aging and diseases such as cancer, as well as human diversity, evolution and migration patterns across prehistory.

Mapping this genetic material should help explain how humans adapted to and survived infections and plagues, how our bodies clear toxins, how people respond differently to drugs, what makes the brain distinctly human, and what makes each of us distinct, said Evan Eichler, a geneticist at the University of Washington School of Medicine who helped lead the research.

First new ALS drug in 5 years

In September, the Food and Drug Administration approved the use of Relyvrio to treat amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, more commonly known as ALS.

Early trial data suggests Relyvrio is particularly helpful early in the fatal disease that gradually robs people of their ability to control their movement, eventually including breathing. Preliminary data from a six-month trial in 137 patients, half of whom received a placebo and half the active drug, suggested Relyvrio could slow the rate of decline. A follow-up found that patients on the active drug lived longer than those who got the placebo.

But patients expressed dismay after Amylyx Pharmaceuticals, the Cambridge, Massachusetts-based company that makes Relyvrio, said it would charge $158,000 a year for the drug.

Only five other drugs are approved to treat ALS, the most recent in 2017, but none has been shown to stop the inexorable loss of muscle control. Only one has been shown in some people to extend life, but by just three months on average.

What's in store for 2023?

Vaccines, vaccines and more vaccines: The research probably will carry into the new year as scientists continue their fight against respiratory viruses.

Flu and COVID vaccine: Moderna and Pfizer-BioNTech are beginning trials to assess the safety, efficacy and dosage of their candidate vaccine that combines four flu strains and two coronavirus strains.

Treatment for RSV: Six drug companies are developing RSV vaccines or antibodies, which suggests this year could be the last without adequate tools to fight the virus.

Visit medicine boxes homepage for more details.

Weight loss medications: Treatment for obesity is on the verge of transformation in 2023. Here's a look:

Tirzepatide: A new study showed the drug approved to treat Type 2 diabetes is extremely effective at reducing obesity. Those taking the highest of the three studied doses lost as much as 21% of their weight – up to 60 pounds in some cases.

Semaglutide: Makers of a weight loss drug approved last year say they'll increase supply in 2023. Under the brand name Wegovy, the 2.4 mg dose of semaglutide provides an average of up to about 15% weight loss.

0 notes

Photo

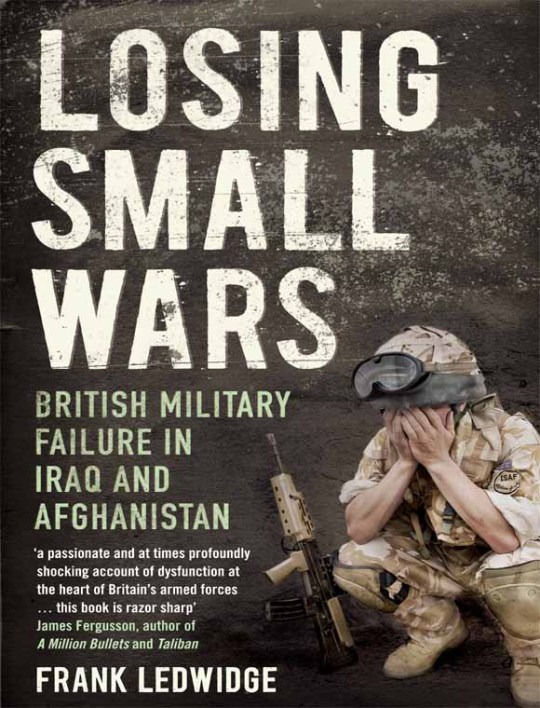

Title: Losing Small Wars: British Military Failure in Iraq and Afghanistan

Authors: Frank Ledwidge

ISBN: 9780300166712

Tags: Afghanistan, Basra, British Army, From LAPL, Helmand, Iraq, Operation Enduring Freedom, Operation Herrick, Operation Iraqi Freedom, Operation Telic

Subject: Books.Military.20th-21st Century.Middle East-SWA.Afghanistan.UK, Books.Military.20th-21st Century.Middle East-SWA.Iraq.OIF.UK

Partly on the strength of their apparent success in insurgencies such as Malaya and Northern Ireland, the British armed forces have long been perceived as world class, if not world beating. However, their recent performance in Iraq and Afghanistan is widely seen as—at best—disappointing; under British control Basra degenerated into a lawless city riven with internecine violence, while tactical mistakes and strategic incompetence in Helmand Province resulted in heavy civilian and military casualties and a climate of violence and insecurity. In both cases the British were eventually and humiliatingly bailed out by the US army.

In this thoughtful and compellingly readable book, Frank Ledwidge examines the British involvement in Iraq and Afghanistan, asking how and why it went so wrong. With the aid of copious research, interviews with senior officers, and his own personal experiences, he looks in detail at the failures of strategic thinking and culture that led to defeat in Britain's latest "small wars." This is an eye-opening analysis of the causes of military failure, and its enormous costs.

#books#ebooks#booklr#nonfiction#uk#military history#Afghanistan#basra#iraq#british army#helmand#operation enduring freedom#operation herrick#operation iraqi freedom#operation telic#GWOT

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

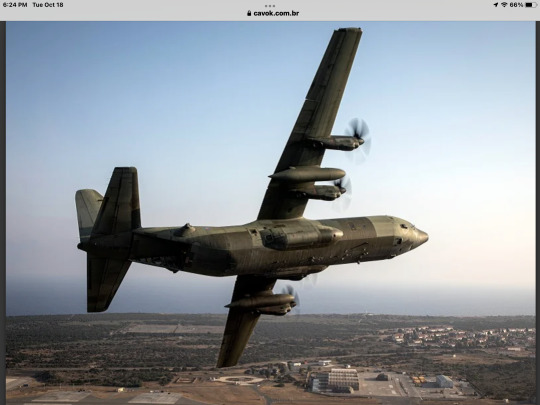

United Kingdom sells its C-130J aircraft

Fernando Valduga By Fernando Valduga 10/18/2022 - 11:00 in Military

The UK Ministry of Defense has added the fleet of 14 Royal Air Force (RAF) C-130J aircraft to its list of military equipment that will be available for sale from 2023, which is scheduled to be the type service withdrawal date.

Availability was disclosed by the Defense Equipment Sales Authority (DESA) that is part of Defense Equipment and Support (DE&S), within the United Kingdom Ministry of Defense (MoD), and is the organization with exclusive authority and responsibility to oversee the sale of surplus military equipment from the United Kingdom Armed Forces. The sale advertising by DESA offers customers the most economical alternative for the purchase of new military equipment.

DESA is currently trading several C-130J aircraft that are leaving service between 2023 and 2025. They are available for sale at the UK Ministry of Defense, which is working with its main retail partner Marshall Aerospace, which will provide the necessary entry into service, support and capacity improvements.

The Lockheed Martin C-130J Super Hercules, a four-engine turboprop military transport aircraft, is the latest version of the C-130 Hercules and the only model in production. In March 2022, 500 C-130J aircraft were delivered to 26 operators in 22 countries. Externally similar to the classic Hercules in general appearance, the J model features considerably updated technology. These differences include new Rolls-Royce AE 2100 D3 turboprop engines, propellers with blades composed of six Dowty R391 blades with 35-degree inclined paddle tips, digital avians and reduced crew requirements.

The Hercules is the main tactical transport aircraft of the Royal Air Force and in its current C.Mk 4 and C.Mk 5 versions of the C-130J-30 and C-130J, respectively, it has been the backbone of the UK's operational tactical mobility tasks since it entered service in 1999. It is often used to operate in countries or regions where there is a threat to aircraft; its performance, tactics and defensive systems make it the ideal platform for such tasks.

The C-130J aircraft is highly flexible, with the ability to launch a variety of supplies and paratroopers, and operate from natural land landing areas. Long-range capabilities are enhanced with air-to-air refuelling, while the Air Survival Rescue Apparatus can be mounted in the cabin for search and rescue missions, allowing Hercules to release lifeboats and emergency supplies.

Having worked intensively during Operations Telic and Herrick alongside the fleet inherited from Hercules, the C-130J accumulated flight hours much faster than had been projected. It was identified in the 2010 Strategic Defense and Security Review for withdrawal from service in 2022, a decade earlier than originally planned. At this point, the A400M program was very advanced.

The Airbus A400M Atlas has always been intended to replace the Hercules and, although its tactical capacity has probably expanded dramatically by 2022, the C-130J clearly had an important tactical role to play until the A400M was fully established. The 2015 Strategic Defense and Security Review reflected this thought, with the announcement that 14 Hercules C4s would remain in service until 2030.

Comparing the two platforms, the Atlas has greater resistance, speed and payload of the C-130J. However, although Atlas can perform much, if not all, of the functions of the C-130Js over time, the loss of the United Kingdom's Super Hercules fleet still represents a cut in the number of fuselages, with suggestions for additional purchases of A400M seem increasingly unlikely, due to the cuts that will probably be necessary to balance the budget of the MoD.

Tags: Military AviationC-130J Super HerculesRAF - Royal Air Force/Royal Air Force

Previous news

Heart Aerospace and Sevenair sign agreement for up to six ES-30s electric planes

Next news

New video of the runway exit of DHL's Boeing 757 occurred in April

Fernando Valduga

Fernando Valduga

Aviation photographer and pilot since 1992, he has participated in several events and air operations, such as Cruzex, AirVenture, Dayton Airshow and FIDAE. It has works published in specialized aviation magazines in Brazil and abroad. Uses Canon equipment during his photographic work in the world of aviation.

Related news

HAL LCA Tejas.

MILITARY

India evaluates modifying LCA Tejas for Argentina

18/10/2022 - 18:40

MILITARY

GA-ASI flight tests state-of-the-art flight computer in the Gray Eagle Extended Range

18/10/2022 - 16:00

MILITARY

Belarus will hold several joint exercises of real shots with Russia

18/10/2022 - 14:00

Boeing image of the probable future cockpit of the B-52H, after modifications to the radar and engine were made to the 60-year-old bomber. (Photo: Boeing)

MILITARY

Image of the new cockpit of the B-52 shows a cleaner layout

18/10/2022 - 08:07

MILITARY

Swedish Gripens and RAF Typhoons perform Baltic Striker air attack exercise

17/10/2022 - 22:56

AIR ACCIDENTS

VIDEO: Russian Su-34 jet collides with residential building in Russia

17/10/2022 - 20:06

home Main Page Editorials INFORMATION events Cooperate Specialities advertise about

Cavok Brazil - Digital Tchê Web Creation

Commercial

Executive

Helicopters

HISTORY

Military

Brazilian Air Force

Space

Specialities

Cavok Brazil - Digital Tchê Web Creation

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

6 November 2013

The Duchess of Gloucester presents campaign medals to soldiers attached to 1 Mechanized Brigade following their recent tour of duty in Afghanistan during Operation Herrick 18, as they parade at Picton Barracks, Bulford, Wiltshire.

© Ben Birchall

#birgitte spam#she looks tiny#hahaha#surrounded by tall men#smiley birgitte#i have a crush on her#duchess of gloucester

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

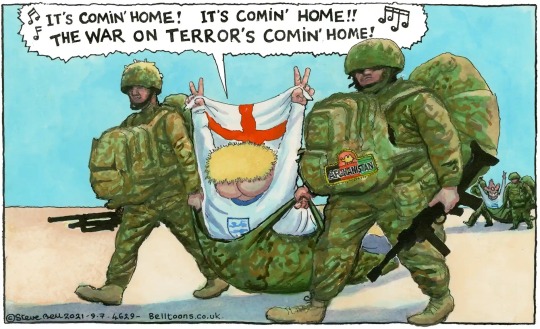

ltdan2288 asked: As a fellow veteran of the Afghan Campaign, might I ask if you have any thoughts about the imminent end of Allied air support & combat-advisory operations over there? The fall of large swaths of the country to the Taliban is already underway, which can only be seen as an unspeakable tragedy for the people there. From a strategic perspective, there’s no reason to believe that we won’t have to return in some capacity of AQ or ISIS reestablish themselves under Taliban sponsorship. At the same time, it’s not clear to me that our presence did anything beyond kick the can down the road and delay this inevitable outcome. As someone with such a deep knowledge of military history, I’m curious if you have a different perspective.

I have been avoiding answering this post for a while now because Afghanistan dredges up so many conflicting emotions inside me. I wrestle with so many memories of my time there with my regiment to fight in a war that we all didn’t really understand what we were fighting for.

Deep breath.

Almost two decades of conflict in Afghanistan has cost British taxpayers £22.2billion, or $31.3 billion according to UK government figures. As British troops prepare to leave Afghanistan, the 20-year deployment bill could be even higher. As of May 2021, the total cost of Operation Herrick (codename for the deployment of British soldiers to Helmand province) is £22.2billion. There were 457 fatalities on, or subsequently due to, Op Herrick. Of which 403 were due to hostile action. During the operation between January 1, 2006 and November 30, 2014, there were 10,382 British service personnel casualties. Of these 5,705 were injuries and the remainder being illness or disease. The UK’s remaining 750 troops in Afghanistan, involved in training local forces, started exiting the war-devastated country in May. Most of them will return home by the end of July.

They, like every one of us who went to fight in Afghanistan, will ask the same questions, ‘Why did we go there?’ ‘What was the real purpose of the mission?’ ‘Was it worth it?’

Both my older brothers fought there with special distinction and I later fought there too. I have very mixed emotions when I think about my time in Afghanistan. For all its faults and tortured history, I love that country and love its many ethnic people. I even started to learn Pashtu as I already had a spoken command of Urdu because I had been raised partly in both Pakistan and India and it’s where many Afghan refugees living in the UN camps for over a generation had learned Urdu too.

It’s not just that my family has history in Afghanistan going back to the days of the East India Company but I had a sincere respect for its culture and history as one of the central hot spots for great civilisational achievements, but also as a stubborn and unruly country who proudly defied the Great Powers to bend the knee and turned it into a ‘graveyard of empires’. Most of all I think of the friendships I made there and how my perspective on life changed as a consequence of knowing such resilience and fortitude in the face of catastrophe and death.

I’m sure like everyone else I wasn’t too surprised by President Biden’s announcement that he was announcing the imminent withdrawal of all American troops in Afghanistan. He wanted to pivot to something else when asked about it. “I want to talk about happy things, man!” He said. Who could begrudge him given that America has been at war in Afghanistan for a better part of 20 years and has nothing to really show for it. Except of course the loss of its brave service men and women as well as the death of thousands of Afghan civilians. It spent more than $2 trillion to kill Osama bin Laden, the architect behind 9/11 attacks and failed to convincingly snuff out both murderous terror groups, Al Qaeda and ISIS.

When the Secretary General of Nato announced back in April 2021 all alliance troops were to be withdrawn from Afghanistan, it was made to look like a nice, clean, enunciation of a joint decision. The end date was set for 11 September, 2021 - 20 years after the terrorist attacks on New York and Washington - and it was in line with the oft-repeated alliance maxim: we went in together; we will come out together. Except that, on closer examination, it was all rather messier.

This was partly because the withdrawal from Afghanistan had actually been Trump’s policy, so here was Joe Biden, the anti-Trump, co-opting a policy from his predecessor (a policy Trump had been so keen on that he tried to accelerate the withdrawal after he lost the election). Biden then tried to detach it from Trump by slowing down the withdrawal date a little and expressing it in terms more comprehensible to the Washington establishment and to US allies.

Where Trump had essentially done a deal with the Taliban and set a withdrawal date of 1 May, Biden left the Taliban out of it and invoked the totemic date of 9/11. This does not mean, of course, that the withdrawal will not be completed a good deal sooner - once you announce a withdrawal, you might as well get on with it.

In fact, Biden had to make a decision one way or another, given the rapid approach of Trump’s 1 May withdrawal date. And, whether it came from Washington or Nato, it was pretty low key for an announcement that a 20-year military involvement that had cost 4,000 allied lives was ending. Indeed, many people beyond Washington and Afghanistan might not quite have registered the news, given the considerable noises from Nato’s simultaneous dire warnings about Russia massing troops on the Ukrainian border, the death of the Duke of Edinburgh in the UK, and the Covid pandemic everywhere.

And distractions were needed not just because Biden was implementing a Trump policy. It was also because he was ordering an unconditional withdrawal – which he justified, correctly, by saying that setting preconditions would mean that the troops could be there forever. It was a risk Biden knew all too well, given that Barack Obama had been persuaded by General David Petraeus – against his election pledges and his better judgement – that what Obama really wanted was not a withdrawal, but a ‘surge’ with conditions attached before a withdrawal could take place.

Distractions were also useful for London, where the timing was hardly ideal. Imagine you were in government in London, you had watched the dismal failure of the UK’s Herrick operations in Helmand Province between 2006 and 2014, you knew that your armed forces had suffered 456 deaths in 20 years, with many more severely injured, but you had hung on in there.

Your government had also just released a blueprint for foreign and security policy, setting future priorities even further from home, in the Indo-Pacific, and your Prime Minister was about to make a high-profile visit to India as part of his post-Brexit ‘Global Britain’ branding . In those circumstances, an announcement that the US had decided to leave Afghanistan, giving you no choice but to follow, was almost exactly what you did not need. Rather than showing the UK as a powerful, autonomous military actor and a valued ally, it showed the exact opposite.

It also reminded an unhappy British public about a costly conflict it had rather forgotten. And those who did more than bother to remember - like the families who lost loved ones on the battlefield - and who over the years have blamed successive governments for moving the goalposts and lacking an exit strategy (all true too).

All of which might explain why the UK’s Foreign and Defence Secretaries followed the US example by changing the subject to the iniquities of Russia and China, rather than issuing a joyous pronouncement to the effect of: hooray and thank goodness, our boys and girls are coming home.

The UK’s Chief of Defence Staff, General Sir Nick Carter gave a subdued, unenthusiastic response to Biden’s announcement. I cannot remember such open acknowledgement of UK-US military policy friction in recent decades - or such an abject admission by the UK of its defence dependence on the US. What Carter said was that the unconditional withdrawal was ‘not a decision we had hoped for, but we obviously respect it and it is clearly an acknowledgement of an evolving US strategic posture’. In other words, the UK had opposed Biden’s decision – or would have done, if asked (which is not clear). Also, that it was Washington’s ‘strategic posture’ that had ‘evolved’, not the UK’s. He suggested there was a real danger that progress made could be lost and that there could be a return to civil war, with the Taliban maybe returning to power - again, all true.

Given that the UK officially has only 750 troops in Afghanistan at present, and most of them are there in a training capacity, to dissent from the US position so openly would be considered decidedly rude in the Ministry of Defence. Perhaps to that end, General Carter played the dutiful soldier and had to - through gritted teeth - put a positive gloss on Afghanistan’s future, insisting that the objective in going into Afghanistan, ‘to prevent international terrorism emerging from the country’, had been achieved which was ‘great tribute to the work of British forces and their allies’.

He also said that Afghan forces were ‘much better trained than one might imagine’ and that the Taliban ‘is not the organisation it once was’, so that ‘a scenario could play out that is actually not quite as bad as perhaps some of the naysayers are predicting.’ Blah blah blah. He’s wrong, and I think he knows it but only in the sanctity of his gentlemen’s club might he truly admit it.

I know he’s wrong because the chatter amongst ex-veterans I know is that we’ve made a balls up of Afghanistan yet again - by ‘again’ I mean from the past 200 years of us Brits trying to bring order to chaos in Afghanistan and getting burned for our troubles.

Both my father and my older siblings tell me what their friends and ex-service peers (some very senior indeed) have been nattering over a drink at their gentlemen clubs where ex-veterans haunt the club bar. Many just shake their heads in sighed resignation before burying themselves in the Times crossword or drowning their sorrows with a beer or two at how lock in step we’ve become to the Americans at a time when the British army is re-branding itself as a more independent nimble hi-tech impact army (the creation of a new ranger regiment being but one example).

Still if President Biden wanted to tie a neat bow on U.S. involvement in Afghanistan - saying, as he had, that the logic for the war ended once al-Qaida was gutted and Osama bin Laden killed - then it reveals a stunning lack of introspection about the United States’ role in the conflict that will continue in Afghanistan long after the last American and British troops leave.

Less than three months after President Joe Biden declared that the last American troops would be out of Afghanistan by September 11th, the withdrawal is nearly complete. The departure from Bagram air base, an hour’s drive north of the capital, Kabul, in effect marked the end of America’s 20-year war. But that does not mean the end of the war in Afghanistan. If anything, it is only going to get worse.

It is true that the president had no good choice on Afghanistan, and that he inherited a bad deal from his predecessor. There are never good choices when it comes to Afghanistan: only bloody trade offs.

But in announcing an unconditional withdrawal, he made the situation worse by throwing out the minimal conditions U.S. Special Envoy Zalmay Khalilzad had negotiated under the Trump administration. U.S. envoy Zalmay Khalilzad has delivered to the Afghan government and Taliban a draft Afghanistan Peace Agreement - the central idea of which is replacing the elected Afghan government with a so-called transitional one that would include the Taliban and then negotiate among its members the future permanent system of government. Crucial blank spaces in the draft include the exact share of power for each of the warring sides and which side would control security institutions.

The refrain now from the Biden administration is that the United States is not abandoning Afghanistan, that it will aim to do right by Afghan women and girls, and that it will try to nudge the Taliban and Kabul toward a peace deal using a diplomatic tool kit.

But the narrative ignores much of the reality on the ground. It also ignores history.

In theory, the Taliban and the American-backed government had been negotiating a peace accord, whereby the insurgents lay down their arms and participate instead in a redesigned political system. In the best-case scenario, strong American support for the government, both financial and military (in the form of continuing air strikes on the Taliban), coupled with immense pressure on the insurgents’ friends, such as Pakistan, might succeed in producing some form of power-sharing agreement.

But even if that were to happen - and the chances are low - it would be a depressing spectacle. The Taliban would insist on moving backwards in the direction of the brutal theocracy they imposed during their previous stint in power, when they confined women to their homes, stopped girls from going to school and meted out harsh punishments for sins such as wearing the wrong clothes or listening to the wrong music.

More likely than any deal, however, is that the Taliban try to use their victories on the battlefield to topple the government by force. They have already overrun much of the countryside, with government units mostly restricted to cities and towns. Demoralised government troops are abandoning their posts. In the first week of July 2021, over 1,000 of them fled from the north-eastern province of Badakhshan to neighbouring Tajikistan. The Taliban have not yet managed to capture and hold any cities, and may lack the manpower to do so in lots of places at once. They may prefer to throttle the government slowly rather than attack it head on. But the momentum is clearly on their side.

America and its NATO allies have spent billions of dollars training and equipping Afghan security forces in the hope that they would one day be able to stand alone. Instead, they started buckling even before America left. Many districts are being taken not by force, but are simply handed over. Soldiers and policemen have surrendered in droves, leaving piles of American-purchased arms and ammunition and fleets of vehicles. Even as the last American troops were leaving Bagram over the weekend of July 3rd, more than 1,000 Afghan soldiers were busy fleeing across the border into neighbouring Tajikistan as they sought to escape a Taliban assault.

As the outlook for the army and for civilians looks increasingly desperate, so do the measures proposed by the government. Ashraf Ghani, the president, is trying to mobilise militias to shore up the flimsy army. He has turned for help to figures such as Atta Mohammad Noor, who rose to power as an anti-Soviet and anti-Taliban commander and is now a potentate and businessman in Balkh province. “No matter what, we will defend our cities and the dignity of our people,” said Mr Noor in his gilded reception hall in Mazar-i-Sharif, the key to holding the north (sounds like Game of Thrones). The thinking is that such a mobilisation would be a temporary measure to give the army breathing space and allow it to regroup and the new forces would co-ordinate with government troops to push back hard on the Taliban.

However this is Afghanistan. The prospect of unleashing warlords’ private armies fills many Afghans with dread, reminding them of the anarchy of the 1990s. Such militias, raised along ethnic lines, tended to turn on each other and the general population.

With America gone and Afghan forces melting away, the Taliban fancy their prospects. They show little sign of engaging in serious negotiations with Mr Ghani’s administration. Yet they control no major towns or cities. Sewing up the countryside puts pressure on the urban centres, but the Taliban may be in no hurry to force the issue. They generally lack heavy weapons. They may also lack the numbers to take a city against sustained resistance. On July 7th they failed to capture Qala-e-Naw, a small town. Besides, controlling a city would bring fresh headaches. They are not good at providing government services.

Perhaps the Taliban have learned their history lesson and might refrain from attacking Kabul this time around. Their best course may be to tighten the screws and wait for the government to buckle. American predictions of its fate are getting gloomier. Intelligence agencies think Mr Ghani’s government could collapse within six months, according to the Wall Street Journal. So clearly the momentum is on the side of the Taliban and they just need to chip away at Ghani’s forces one district after another until the inevitable and hateful surrender of the central Afghan government to their demands.

At the very least, the civil war is likely to intensify, as the Taliban press their advantage and the government fights for its life. Other countries - China, India, Iran, Russia and Pakistan - will seek to fill the vacuum left by America. Some will funnel money and weapons to friendly warlords. The result will be yet more bloodshed and destruction, in a country that has suffered constant warfare for more than 40 years. Those who worry about possible reprisals against the locals who worked as translators for the Americans are missing the big picture: America, Britain and other allies are abandoning an entire country of almost 40m people to a grisly fate.

Nothing exemplifies - at least in Afghan eyes - of all that has gone wrong with American involvement in Afghanistan than in the manner of their leaving.

The U.S. left Afghanistan's Bagram Airfield after nearly 20 years by shutting off the electricity and slipping away in the night without notifying the base's new Afghan commander, who discovered the Americans' departure more than two hours after they left in the middle of the night without raising any alarms.

They left behind 3.5 million items, including tens of thousands of bottles of water, energy drinks and military MRE's (Meals Ready to Eat ration packs to the uninitiated). Thousands of civilian vehicles were left, many without keys to start them, and hundreds of armoured vehicles. The Americans also left small weapons and ammunition, but the departing US troops took heavy weapons with them. Ammunition for weapons not left for the Afghan military was blown up.

Now that is some feat considering the logistics of this mass exodus without drawing any attention. You have obviously been to Bagram and so you will know just how big and sprawling it is. Bagram Airfield is the size of a small city, roadways weaving through barracks and past hangar-like buildings. There are two runways and more than 100 parking spots for fighter jets known as revetments. One of the two runways is 12,000 feet long and was built in 2006. There's a passenger lounge, a 50-bed hospital and giant hangar-size tents filled with furniture. And all those shops to remind Americans of home from familiar fast food restaurants and hairdressers and massage parlours to buying clothing and jewellery and buying a Harley Davidson motorbike (or so I’ve been told).

I’m guessing that the Afghans were certainly outside of the wire and probably had not been inside Bagram Airfield for months. So from the outset they would not have had any reason to think anything was going on until the generators probably ran out of fuel and it started to go a little too quiet. The inner gate was probably discretely left unlocked and when the US stopped answering the radio/phone and then they probably investigated.

Before the Afghan army could take control of the airfield about an hour's drive from the Afghan capital, Kabul, it was invaded by a small army of looters, who ransacked barrack after barrack and rummaged through giant storage tents before being evicted, according to Afghan troops. Afghan military leaders insist the Afghan National Security and Defense Force could hold on to the heavily fortified base despite a string of Taliban wins on the battlefield. The airfield includes a prison with about 5,000 prisoners, many of them allegedly Taliban members.

I’m pretty sure some bright spark in the US Pentagon public affairs dept convinced his military superiors that it was important to avoid the optics of Americans leaving in the same way they did in Vietnam in case it depresses the American public and the US military. Instead it demoralised its allies, the Afghan national army who are now the only line of defence against the Taliban. In one night, they lost all the goodwill of 20 years by leaving the way they did, in the night, without telling the Afghan soldiers who were outside patrolling the area. The manner in which the Americans left Bagram air base amounts to a resounding vote of no confidence in Afghanistan’s future. It just looks bad.

The U.S. choice came with costs attached to each decision. With staying, the cost was potential U.S. troop casualties and a fear that things would not change on the ground. With leaving comes the cost of a deeper conflict in Afghanistan and a backsliding of progress made there over the past two decades. In many ways, the costs of staying seem shorter-term and borne by the United States, while the costs of leaving will be predominantly borne by Afghans over a longer time horizon. Yet, even if those costs seem remote now, history tells us that they will be blamed on the United States.

Biden perhaps reflective of history of Americans getting into quagmires abroad didn’t want to be seen exerting time and energy for a losing cause. His decision also reflects his administration’s foreign policy for the American middle-class paradigm, which focuses on domestic considerations over international ones (and is this so different from Trump’s “America First”? No, it is not). The irony, though, is that the American middle class largely doesn’t care about Afghanistan - their ambivalence gave way to support for this decision once it was announced, but it wouldn’t be hard to visualise the public approving of a scenario that kept a couple thousand troops there for a while longer.

What’s perhaps most disturbing is the narrative the president has presented along with the rationale for withdrawal: that America went to Afghanistan to defeat al-Qaida after 9/11, that mission creep led America to stay on too long and, therefore, it is time to get out. This takes an incomplete view of U.S. agency in the war in Afghanistan. The narrative implies that the civil conflict in Afghanistan today did not originate with America - that this more than 40-year war began with the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan in 1979, preceded America’s interference in Afghanistan, and will follow our departure.

The fact of the matter is that, by beginning the campaign in Afghanistan in 2001 and overthrowing the Taliban, who were then engaged in their draconian rule, and installing a new government, we western allies began a new phase of the Afghan conflict — one that pitted the Kabul government and the United States/Britain/NATO against the Taliban insurgency. The Afghan people did not have a say in the matter. That we allied powers are leaving Afghan women, children, and youth better off in many ways after 20 years is due to us, and we should be proud of that. But that we are leaving them mired in a bloody conflict is also due to us, because we could not hold off the Taliban insurgency, and we must all reckon publicly with that.

I have to ask myself why did we fail?

I’m only speaking about us Brits now as I’m sure you have your own thoughts as an ex-Marine officer of what you thought of the American military effort. Yes, I’m copping out of really bashing the yanks because first, I have too much respect for those fantastic American service men and women I did have the privilege to fight alongside with; and second, we Brits have nothing to crow about as we fucked up in lots of ways too, and to make things worse, we should have known better given our imperial history with Afghanistan.

The seeds of our failure in Afghanistan lies in not learning from history. We didn’t have a mission that was properly defined nor did we have a strategy that was clear, coherent, and easily communicated to both its fighting men and women as well as to the British public.

Were we there to get our hands bloody and to root out and destroy extreme Islamist terrorists or were we there to indulge in state building out of some idealistic notions of liberal humanitarianism? This question was at heart of our failure within our government and also within the British army as well as our relations with America and our NATO allies and finally the Afghans themselves.

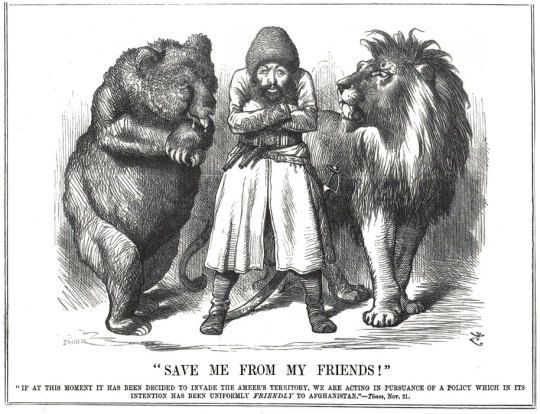

Although never colonised in the same manner as other central and south Asian countries, the modern Afghan state is very much a creation borne out of great power rivalry. A land occupied by a number of different ethnic, linguistic and religious groups, it is a country whose borders were defined by, and whose sense of national identity was forged in response to western great power competition. Its geopolitical position - landlocked, mountainous, and surrounded by past great powers and present regional rivals - lends Afghanistan a dual role of geographic obscurity and great strategic significance, and has as such frequently been treated as little more than a buffer state between empires and a proxy of local powers. Its shared historical border with Russia and British India made it an object of imperial intrigue and, by consequence, has been subject to five European military interventions in the last 175 years.

The first three interventions of these occurred during the era of ‘the Great Game’ in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, in which Britain and Russia (latterly the Soviet Union) competed for influence and control over Afghan politics in order to protect their respective imperial holdings in India and central Asia.

The fourth and fifth interventions, ranging from the late 1970s to the present day, similarly involved attempts by Soviets and then by an American-led international coalition to remove political leaders acting against their interests and to protect their favoured candidates.

The unifying feature of all these conflicts was the idea of Afghanistan as the site of potential threats to the interests and security of more powerful states.

Britain’s legacy in Afghanistan in particular set the tone for the country’s historical pattern of conflict and political contestation, fuelling both the intermittent emergence of Afghan national consciousness and a fractious political lineage that saw thirteen amirs in just eighty years. Interventions by the Empire during the Great Game set the conditions for the assassination of ostensibly national leaders by their compatriots (Shah Shuja Durrani in the First war) or their exile by the British (Shere Ali Khan and Ayub Khan in the Second).

Despite the British achieving their aim of protecting India in the second and third conflicts by maintaining Afghanistan as either a pro-British buffer state or as a neutral party, the Afghan narrative tends to emphasise successes such as the massacre of British forces retreating from Kabul to Jalalabad in 1842, the defeat of British and Indian forces at Maiwand in 1880, and the gaining of sovereignty in foreign affairs in 1919.

Soviet intervention in the late 1970s and 1980s further buttressed this identity of resistance, and the failure and ultimate overthrow of the Communist-backed Najibullah government, as well as the collapse of the Soviet Union shortly after their drawdown from Afghanistan, led to a sense amongst the victorious mujahidin of the country as the ‘graveyard of empires’.

Afghanistan’s modern history should thus be seen as inextricably linked to the ebbs and flows of great power politics. Each intervention exacerbated extant internal power struggles between rival elite individuals and groups vying for nominal control over the country. Foreign intervention in Afghanistan was met on each occasion with fierce resistance from tribal militias coalesced around religion; as has been remarked upon by one historian of the country, the threat of external domination has been one of the few means of uniting its disparate population around the concept of an Afghan ‘nation’, and in most cases this shared sense of identity cohered around religion, not nationalism.

Indeed, the presence of intervening powers and the development of the Afghan state may be seen as mutually supporting: whilst most Afghan leaders throughout the last two centuries have asserted their sovereignty over the country, the reality has in most circumstances been one of competing tribal chiefs and/or ‘warlords’ rather than a single dominant leader.

Where leaders have managed to cohere the disparate tribal and ethnic groupings of the country under one banner - most notably under the regime of Dost Mohamed Khan (1826-1839, 1845-1863) – this was due in large part to their diplomatic abilities of compromise and co-optation with Afghanistan’s regional power- brokers. In other cases, such as that of the reign of Abdurrahman (1880- 1901), power was maintained by an unflinching ‘internal imperialism’ and the use of punitive force against rebellious factions.

The challenges of maintaining and projecting centralised power in Afghanistan allow us to see the relationship of its leaders with world or regional powers in the last two centuries as one of mutual exploitation. Throughout the Great Game and the Cold War, whilst the British/Americans and Russians/Soviets would use threats and bribes (and occasionally force) to compel Afghan rulers to comply with their geopolitical needs, Afghan rulers themselves often deftly manipulated those powers to maintain and extend their own power.

The pattern followed by Afghan leaders from the nineteenth century to the present day is remarkably similar in the respect that most have relied upon a rentierist economic model, seeking external aid in order to sustain the cost of security and administration. The plan of modern rulers was to warm Afghanistan with the heat generated by the great power conflicts without getting drawn into them directly. Abdurrahman, for example, used British subsidies to fund his military campaigns against rebellious factions; the Musahiban rulers of the mid-twentieth century used American capital to develop its nascent economic infrastructure and Soviet finance to bolster its armed forces; and, following the overthrow of the last royal leader of Afghanistan, Mohamed Daoud, in 1978, the quasi-communist leadership of Babrak Karmal, Hafizullah Amin, Nur Muhammad Taraki, and Mohammad Najibullah during the late 1970s and 1980s relied in the main on Soviet money and military assistance in its ultimately failed attempt to implement socialist policies and put down the American, Saudi and Pakistani-backed mujahidin.

These trends continued into the post-Cold War period in respect to both the Taliban movement (essentially directed and funded by Pakistan), the Northern Alliance (funded largely by former Soviet central Asian states) and the regime of Hamid Karzai (maintained in economic and military terms by the American-led, NATO-operated International Security Assistance Force and the wider international community). In the former cases, occurring in the main in the period of civil war between 1992 and 2001, rentierism was limited to the maintenance of proxy parties and the continuation of conflict.

By contrast, the ISAF mission bore similarities with the Soviet-backed socialist regimes of the 1980s, insofar as it focused huge amounts of capital and military resources on stabilisation and state-building efforts. Both intervening parties made the error of ignoring Afghanistan’s political history and focused their efforts on bolstering the authority of a centralised state, both promoted policies that were deemed ‘universal’ in their application and were, unsurprisingly given such hubris, vulnerable to accusations by Afghan opposition to being alien and imperialistic ideologies, and both expended enormous amounts of blood and treasure in order to sustain the regimes they supported.

The UK’s struggle to locate a coherent strategy for Afghanistan should, therefore, be seen firstly in the light of the historical problematic of Afghan state-building. This is important in narrative terms because difficulties of defining strategy imply similar challenges in explaining strategy. As with its efforts to ‘think’ strategically, Britain’s ability to explain the strategy(ies) for the war in Afghanistan have been frequently criticised by various commentators. The most strategically debilitating aspect of the Afghan campaign has always been the incoherence of the mission’s purpose; indeed the question ‘‘why are we in Afghanistan?’’ has never really been settled in public consciousness.

The international community massively underestimated the difficulties of state-building and greatly overstretched themselves in the commitments made to Afghanistan, and that they did so because ‘strategies’ for Afghanistan rested on assumptions of the universal applicability of liberal state-building.

The international community from the start (meaning from the Bonn Conference of late 2001) fundamentally misunderstood the nature of an Afghan society deeply ravaged by decades of conflict, and failed to foresee the malign effects state-building ventures would have on the country. Specifically, the Bonn Conference, which set out the parameters of the post-invasion Afghan state, implemented a centralised state system onto a state whose experience of such was limited, and where the success of such a system in extending its authority beyond the major cities was predicated on coercion and the use of force.

Historically this has rarely been a credible option for Afghan rulers or their international backers, and was even less so under the self-imposed restrictions of liberal war-fighting and state-building. Rather, re-creating a centralised state required Afghan and international actors to enter into the same methods of co-optation and compromise as those of the past; in necessitating these kind of measures – as opposed to implementing a looser, federal system of governance – the centralisation of the Afghan state paved the way for a reconstitution of a ruling order based on tribal elements and ‘strongmen’. This produced something of a paradox for state-builders, as the creation of a strong, central state capable of implementing liberal policies across Afghanistan came at the cost of entering into alliances with ‘warlords’ known for their illiberal and coercive political approaches and illicit economic activities.

Another unintended but unavoidable consequence of centralised state-building identified by scholars is the re-constitution of the rentier state in Afghanistan. Post-Bonn, Afghanistan returned to its historical norm of maintaining the state via the extraction of external security and development rents, without which it would almost certainly implode due to the ruinous state of its economy and taxation system. Studies have shown that his new rentierism differed from previous patronage systems at the state level insofar as it was fuelled by an unprecedented influx of capital and resources into the country. This had the effect of introducing regulated systems of ‘neo-patrimonalism’, where departments were to be distributed as rewards to the various factions that took part in the Bonn conference, and there had to be enough rewards to go around.

In other words, the structure of the post-invasion Afghan state was, to a great extent, defined not by the demands of good governance, the needs of the country or the demands of post-conflict stabilisation and reconstruction – the purposes for which the centralised model was chosen to promote – but rather by the first-order need to avoid the derailment of the centralised state by co-opting regional power brokers.

Because of the imperative of shoring up a nascent state by securing support from potential competitors, the gulf between the ends of liberal state-building and the illiberal means required to facilitate its functioning can therefore be seen to a certain extent as inevitable.

A major issue, however, was that the patrimonial linkages created by the state for its regional proxies was not comprehensive, as it did not extend to the Taliban’s Pashtun heartland and, as such, fuelled resentment and alienation as much as they placated and co- opted extra-state power brokers. Key players in the Northern Alliance - the primarily Tajik opposition to the Taliban - received prestigious posts within the state, whilst the predominantly Pashtun Taliban were themselves excluded from such arrangements. Because those rewarded by the state tended to be given ministerial or governorial roles in cities, the conflict dynamic tended to reflect an urban – rural divide similar to that of the Soviet occupation. Along this reading, the neo-Taliban insurgency was in many ways a product of the political miscalculations and deficiencies of post-invasion state- building activities.

Given this starting point, such a view concludes that the strategic problems encountered by the international community in Afghanistan were, to a large degree, problems created by (or at the very least exacerbated by) the state-builders themselves. They misread Afghan politics in a way that reflected their own philosophical assumptions about the state and society.

Strategy in Afghanistan suffered because the coalition effort, comprised of multiple national actors and the United Nations, rarely took on the form of a unified effort. Part of the reason for this was a divergence of opinion between actors as to the ultimate purpose – counter-terrorism or state-building – of the intervention.

In the first years of the Afghan campaign, the United States’ Bush Administration remained staunchly opposed to what it called ‘nation building’ and opted instead to pursue a policy of capture- or-kill missions against suspected terrorists. For the United Nations and most of the United States’ European NATO allies, however, state-building was considered a necessary element of any counter-terrorist strategy. This difference of opinion was manifest from the start by the creation of two parallel missions – the US-led, counter-terrorism-focused Operation Enduring Freedom (OEF) and the stabilisation missions of the European Union, United Nations (United Nations Assistance Mission in Afghanistan (UNAMA)) and NATO (International Security Assistance Force (ISAF)) – engaged in seemingly incompatible aims of military prosecution and peace building.

Opinion on the impact of this dual approach varies. Some scholars have noted, along lines similar to those critiquing the state-building efforts of the international community that the approach taken by the UN, EU and ISAF was too ambitious, naïve and unrealistic, and therefore bound to fall short of their liberal political and economic goals. Both Europe and these international agencies ignored the necessity of paring down the international community’s state-building efforts to core, security-centric capacity building within the Afghan National Security Forces. But of course one can make the counter argument, as many have of course, that on the contrary it was the insufficiencies of state-building approaches vis-à-vis OEF’s counter-terrorist approach that led to subsequent failures in UN and ISAF efforts; specifically, that a disproportionate focus on counter-terrorism missions meant that opportunities of peace- building were irreparably compromised.

Within NATO there was a division not just of opinions but also one of mission relating to different political perspectives about the purpose of the Afghan mission and its ultimate referent object – whether it was primarily about the interests of the coalition member states or concerned in the main with Afghanistan itself – and, from that, the methods to be employed in pursuit of one or another objective. This was not merely a debate bounded by strategic necessity, however; rather, such debates stemmed as much from institutional disagreements over who would or could do what in Afghanistan, which in turn arose from the differences in political constitutions and cultural attitudes towards counterinsurgency and counter- terrorism.

These ‘national caveats’ or ‘red cards’ of participation created significant problems for NATO in Afghanistan, both political, in terms of the relations between states and the abiding sense amongst some that others were ‘free-riding’ on the collective security system and, and strategic and operational, in the sense that command-and-control capabilities and cohesion between forces were limited by the engagement restrictions placed on certain armed forces. Indeed, the disproportionate burden placed on combat-oriented states like the United States, the United Kingdom, and several new member states in Eastern Europe led to political statements denouncing Europe’s perceived transgressors of collective security participation; former US Defence Secretary Robert Gates argued, for example, that NATO had effectively become a ‘two-tier alliance’ ‘between members who specialise in ‘soft’ humanitarian, development, peacekeeping and talking tasks and those conducting the ‘hard’ combat missions - between those willing and able to pay the price and bear the burdens of alliance commitments, and those who enjoy the benefits of NATO membership... but don’t want to share the risks and the costs’.

A lack of strategic unity was the natural consequence of a structural compromise that produced two distinct strategic authorities that were, in many ways, competing with one another. Along similar lines to the political arrangements between the Afghan state and its regional proxies, the NATO alliance structure can be seen (and evidently is seen by officials such as Gates) as patrimonial: states participated on the basis of fulfilling their own interests and along operational lines that were complementary to those interests, for the purposes of securing an alliance structure that accommodated all participants ahead of the imperative of creating a coherent strategy for stabilising Afghanistan. As with the neo-patrimonialism of the Karzai regime NATO’s efforts would be dictated by the limitations imposed upon it by circumstance.

Thus, in the cases of Afghanistan’s and the international community’s internal political dynamics, strategy was confined by the structure of the Afghan state and society, the structure of the international community and NATO, and the interplay between those structures. The implication here is that the agency required for the possibility of a workable strategy may have been illusory from the start.

Leaving Afghanistan was never going to be pretty, but the latest turn is uglier than expected.

No one quite expected the speed of collapse within the Afghan National Army to hold of attacks of the Taliban. I don’t think it’s do with the lack of training or their professional skills is lacking (though there may be some truth in it). A big driver in the collapse is the money for wages, food and medical care for troops is syphoned to Dubai, so the Afghans who want to fight, and there are quite a few who hate the Taliban, get less replenishment than the 6th army in the last weeks of Stalingrad. They have arms, ammo and boots for this season only and that is it. Both money and morale are in short supply for these soldiers.

If I was a trained soldier in the Afghan National Army I would desert. I would say to them abandon the fixed defences these ‘ferenghis’ (foreigners) have gifted you and move to the hills and seek refuge with your tribal clan, who will be glad of the arms and experience you bring. Or get over the border if you are lucky to be in the North, if in the West you hire yourself to the Narcos in the badlands on the Iran border. Most other places it is either a last stand or defection, your Government and their relatives have already got their planes fuelled up in Kabul ready to move to their villa complexes in the UAE.

I’m being a trifle cynical but for good reason. Everyone who has been to Afghanistan sees the veil lifted on the corruption of aid and how the elites protect themselves ahead of defending the masses who bear the brunt of the bloodshed.

The corruption has been endemic from the get go, but the international community ignored it all for 'progress'. Any Afghan politico you hear on the media complaining about the West abandoning Afghanistan has at least $30 million parked in Dubai that should have gone to the soldiers, teachers, doctors, builders etc.

As spectacular as the collapse of the Afghan National Army has been it’s been even more scarier seeing how swift the Taliban has been in taking over vital provincial areas through propaganda, civilian intimidation, and rapid attacks. One by one, the Taliban has been taking over areas in a number of provinces in northern Afghanistan in recent weeks. The Taliban says it has taken control of 90 districts across the country since the middle of May. Some were seized without a single shot fired.

The UN's special envoy on Afghanistan, Deborah Lyon put the figure lower, at 50 out of the nation's 370 districts, but feared the worst was yet to come. Most districts that have been taken surround provincial capitals, suggesting that the Taliban are positioning themselves to try and take these capitals once all foreign forces are fully withdrawn. On a map, it's easy to see the point Lyon is making. A stark example is Mazar-i-Sharif, the biggest city in the north and a significant power centre in its own right. It was the rock upon which the Northern Alliance fought against the Taliban.

It is significant the Taliban are kicking off this offensive in the north, not their heartland in the south and east. The north was the toughest part of the country for them to crack last time. Their expectation is if they have victory there, success will flow much easier in their traditional homelands further south.

The strategy of taming the north extends to emasculating and profiting from trade routes to neighbours. On Monday night they captured the important border town of Shir Khan Bandar, Afghanistan's main crossing into Tajikistan. Earlier in the day, top Tajik government officials had met to discuss concerns about the growing instability next door. There is no indication that the Taliban intend to take their fight north of the border, but in the past Tajikistan has been a vital conduit for supplies flowing to the militants' northern enemies.