#no ginsberg poem here BUT it was the california supermarket one

Text

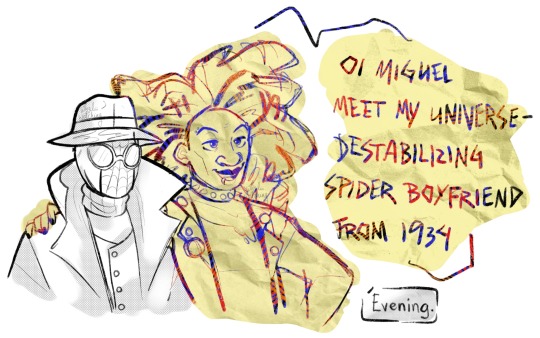

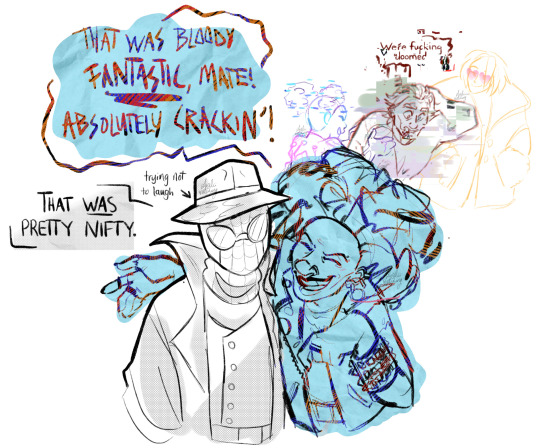

fake to real relationship speedrun record

#spider man: across the spider verse#spider punk#spider noir#hobie brown#noirpunk#miguel o'hara#also margo and lyla are there#this is how noir was introduced to spider society#their combined idea of a perfect date is annoying tbe shit out of miguel#together they are menaces with the power to level societies#the words on hobie’s last paper scrap is a ginsberg poem :)#i forgot i changed it oops#no ginsberg poem here BUT it was the california supermarket one

4K notes

·

View notes

Note

okay okay okay. top 3 albums for summer? favourite book? favourite poem?

i love you <3

ok so. i'm not a party gay i'm a chill at the beach and go on hikes and get sunburnt at a cafe terrace while sipping a fruity little cocktail while i try to contain my third mental breakdown of the day gay. so my summer vibes are quite mellow. i'm gonna go with

when facing the things we turn away from by luke hemmings (lowkey favourite album of all time. this is more of a late august vibe)

strange trails by lord huron (this is my hiking album specifically)

heathers the musical soundtrack (for when i'm in a fun mood)

my favourite book used to be pride and prejudice but lowkey the raven cycle is becoming my fave. like maybe it's because it's the only thing i've read since high school but i really really love it. it's not one book though it's 4

it's so hard to pick a favourite poem!!!! but here are a few i really like off the top of my head, in no particular order:

grow up with me by keaton henson

song of myself by walt whitman (the do i contradict myself very well i contain multitudes quote is in part 51. i distinctly remember being smacked in the face with it the first time i read that)

roots like that by @evenupsidedownbeautifulsomehow

believe me, i'm lying! by @faithdeans (hi <3)

coward, south carolina by @croatstiel

a supermarket in california by allen ginsberg (i just find it comforting that i'm not the only one in a parasocial relationship with walt whitman)

#sorry this took me forever to answer i've been reading poems for the past hour lol#and you know what?#i skimmed through a few of my favourite poetry books#and genuinely my favourite of them all is poetry for fish by us#it's literally so good#better than a lot of classics#rain.asks#isaac tag 🌿

15 notes

·

View notes

Note

hey :) im kinda new to poetry but i rlly like it, and u always seem to have good opinions on it, so do u have any recs?

ABSOLUTELY I DO!!!!

okay i absolutely have to recommend mary oliver at all times!! my personal favorite collection of hers is thirst but you can read a bunch of her stuff online here, and there are also a bunch of collections that feature selections from multiple of her individual works!!

i also really am vibing with maggie smith right now and her collection “good bones”

would HIGHLY recommend alok vaid-menon’s “femme in public” but make sure to check content warnings!!

also ocean vuong has AMAZING prose and poetry (he wrote on earth we’re briefly gorgeous which i would very very highly recommend) and you can read some of his stuff here but my personal favorites are a little closer to the edge and essay on craft

as for individual poems, here are some of my favorites right now!!

vacant lot with pokeweed by amy clampitt (“bleach blond low life” lives in my head rent free)

morning song by sylvia plath (i am obsessed with love poems that are far more than just romantic love!! this one is about maternal love) ((also the “i’m no more your mother/than the cloud…” is one of my favorite stanzas ever!!)) (((and one more thing rip,, i also recommend firesong)))

I am! by john clare (if you vibe with frankenstein, this is a great one!!)

demeter’s prayer to hades by rita dove (i just love her)

the soaring dust of the mortal realm by fei ming

a supermarket in california by allen ginsberg (also howl, which is a read and a half but def worth it)

i would also recommend getting a poetry app!! i like the app poem hunter, it gives you a few poems everyday and has a pretty substantial archive. poetryfoundation.org also has a poem of the day! also, if you’re struggling with a poem, look and see if you can a reading of a poem! they can be super duper helpful

thank you SO much for asking, i love talking about poetry and i think everyone should read it!

#also if you hate all of these poems that’s totally cool!!#there is SO much variety#ask#anon ask#poetry

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

Our Dear Old Queer Uncle Walt

Audrey Salmons

Walt Whitman holds a place in my heart as a sort of patron saint of queer poets. He’s influenced generations of queer literary icons. Langston Hughes, who was closeted but wrote about queer subjects (see “Cafe: 3am” and “Blessed Assurance”), responded to Whitman’s claim to be America’s voice in his poem “I, too, sing America.” Oscar Wilde, who had grown up reading Whitman, met with him while on the lecture circuit in America in 1882, and later wrote to a friend, “the kiss of Walt Whitman is still on my lips.” Allen Ginsberg’s poem “A Supermarket in California” describes a bizarre dream of seeing Whitman at a supermarket, a “childless, lonely old grubber, poking among the meats in the refrigerator and eyeing the grocery boys.” Ginsberg’s irreverent portrayal of the old poet looking rather lost in the landscape of commercialism and family values, surrounded by “[w]hole families shopping at night! Aisles full of husbands! Wives in the avocados, babies in the tomatoes!” makes the grand, flowing, omnisexual poet of “Song of Myself” seem far gone. Rather, Ginsberg’s Whitman reminds me of Whitman’s more cautious and ambivalent “Calamus” poems, which focus on the experience of same-sex love. In slowing down and focusing on a specific and nuanced set of experiences, Whitman contributes to the foundations of what we think of as modern queer identity.

A discussion of the history of queer identity would be incomplete without referencing Foucault’s History of Sexuality, which details the genesis of the homosexual and homosexuality. Until the late 1800s, homosexual acts were generally recognized insofar as they were criminalized as sodomy, but there was no concept of a homosexual identity. Foucault credits Carl Westphal with the creation of the modern homosexual in his 1870 article on “contrary sexual sensations.” From then on, Foucault writes, “[t]he nineteenth-century homosexual became a personage, a past, a case history, and a childhood, in addition to being a type of life, a life form, and a morphology, with an indiscreet anatomy and possibly a mysterious physiology.” When discussing the identities of queer historical figures, it may be tempting to ask, for example, was this person gay or bisexual? However, that person may not have lived with the same language of sexual taxonomy we use today. If we accept that such labels are socially constructed and not essential, then trying to determine which label best suits someone who lived outside those specific constructs is not particularly useful in understanding their personal sense of identity. A similar issue arises when discussing texts such as “Calamus” that describe queerness without specific familiar labels.

So, the shift in language, medicine, and morality from describing homosexual behavior to defining homosexual identity takes place takes place as Whitman is exploring identity and sexuality in “Leaves of Grass.” The focus of the “Calamus” poems on same-sex male attraction and relationships reflects an increasing awareness of a homosexual identity distinct from the androgynous omnisexuality of “Song of Myself,” marked not only by a refocusing of content but a shift in tone. The speaker here does not identify himself so readily with what he observes in the natural world. He describes an oak tree growing “[w]ithout any companion… uttering joyous leaves of dark green,” which at first “made me think of myself, / But I wonder’d how it could utter joyous leaves standing alone there without its friends near, for I knew I could not.” This sense of anxious loneliness is woven throughout “Calamus.” He mourns in “To a Stranger,” “I am not to speak to you, I am to think of you when I sit alone or wake at night alone.” In “Calamus 9,” found in the 1860 edition of Leaves of Grass but eventually cut out, Whitman mourns: “Sullen and suffering hours! (I am ashamed--but it is useless--I am what I am;) / Hours of my torment--I wonder if other men ever have the like, out of the like feelings? / Is there even one other like me--distracted--his friend, his lover, lost to him?” This sense that one’s loneliness and longing are a dreadfully unique burden may be linked to the fact that increasing cultural awareness of homosexuality as an identity necessitates a new type of “closet”: homosexuals must now hide not only acts, but identities. They must present a false front to the world, which Whitman expresses anxiously in “Are You the New Person Drawn Toward Me?”: “Do you see no further than this façade, this smooth and tolerant manner of me? / Do you suppose yourself advancing on real ground toward a real heroic man? / Have you no thought O dreamer that it may be all maya, illusion?” Another struggle in “Calamus,” then, is to create a sort of code by which homosexuals may subtly identify one another, which now may signal not only sexual or romantic intentions, but also solidarity in a shared identity. In “Among the Multitude,” Whitman describes “one picking me out by secret and divine signs, / Acknowledging none else, not parent, wife, husband… Some are baffled, but that one is not— that one knows me.” Whitman addresses “this one” (who is, interestingly, not explicitly gendered in the poem) as a “lover and perfect equal” whom Whitman intends to “discover me so by faint indirections, / And I when I meet you mean to discover you by the like in you.” I find myself imagining Ginsberg (or possibly imagining Ginsberg imagining himself) as the one addressed in this poem, picking up on Whitman’s “indirections” from across the supermarket. I’d like to think that I, too, would be one to recognize Whitman’s queerness— for despite over a century of evolving language and politics, I recognize elements of my own experience as a queer person reflected in "Calamus.”

This article gave me some great insights about “Calamus” and queer identity.

1 note

·

View note

Text

funny guy ginsberg, or “grins”berg

After looking into an alternate technique of queer humor in Peterson’s piece, I’d like to look at Ginsberg and his humor. I am going to look beyond just the poem “A Supermarket in California”, mostly because there is a lot of interesting discussion surrounding the humor in Ginsberg’s poetry and I am intrigued by it. Here’s a little sample of what people are saying about Ginsberg’s humor.

Let’s first look at what Ginsberg himself said in a 1977 interview with Kenneth Koch. When asked what he liked about his poetry, he stated, “ The other thing I like is that I think it's witty or funny. That is the phrasing itself. . . There's a funniness to the manipulation of the syntax.” Ignoring content completely, Ginsberg focuses instead of how the words themselves feel and sound, finding humor in vocabulary and structure instead of meaning. This idea is echoed by Mark Doty in his essay “Human Seraphim: “Howl," Sex, and Holiness” - he references the lines “Time, & alarm clocks fell on their / heads every day for the next decade, / who cut their wrists three times successively / unsuccessfully.” Doty notes that “You can even hear Ginsberg’s chuckle in the sonics; that “successively unsuccessfully” is meant to make us grin”, acknowledging Ginsberg’s idea of wittiness and humor through the use of language. There’s something unique and unusual in provoking humorous reaction through syntax instead of meaning. (It’s also fun to watch the video I posted with this idea in mind - Ginsberg so obviously relishes the text.)

There were two other moments in Doty’s essay that felt important to this conversation. In this first quote, Doty is discussing a reading that Ginsberg did at the Geraldine R. Dodge Poetry Festival:

Then he starts in on his ode to his sphincter muscle, a quirky little paean of praise. This seems to me the most unlikely poem in the world to find a congenial welcome on the ears of the assembled secondary school teachers, so I can’t help looking around the ranked seats to check it out. Sure enough, they are loving it, they are laughing and clapping, absorbed in delight. . . But Ginsberg entirely transcended the question of polite behavior, of queerness, of the appropriate [and] created some zone of permission and distinction for himself that seemed to make all things possible, and he seemed to occupy a category all his own.

Doty here is introducing the idea of Ginsberg as using his humor to surpass and destabilize norms. Ginsberg was able to present a poem that was “the most unlikely poem in the world to find a congenial welcome” and made it acceptable in the eyes of the audience because he was able to make them laugh. The following quote sets up a similar concept:

This pose—transcendent wild boys versus spirit-crushing monolithic Moloch—is an affecting one, in small doses, though it might be a bit hard to take were “Howl” not so exuberantly funny. That’s the part I’d forgotten, or perhaps never really seen. Was Ginsberg’s humor harder to get, back when his transgressions seemed more incendiary?

In this case, Doty is pointing out that Ginsberg uses his humor as a way to make his work. . . not necessarily more palatable, because that gives an air of desiring social approval, but rather as a way of providing levity in a text that could get overdone. Ginsberg is doing the work of queering by writing in way that could be unacceptable, but not seen as such because of the comedy. Doty, in both situations, is acknowledging how Ginsberg’s humor in his poetry is used to transform opinion, whether that is drawing laughter out of a poem about his asshole or undercutting what could be am irritating trope in his collection.

The last interpretation that I want to look at is by Harvard Professor David Perkins, who says:

Perhaps the hardest aspect of the poem to accept is, paradoxically, its humor. . . Ginsberg's self-reducing humor helps to explain the remarkably good-natured acceptance bestowed on him. He is perceived more as a spiritual clown than as a threat. A psychoanalyst might suggest that Ginsberg is a child testing the father's love. His provocations are what Erik Erikson calls "teasing." They defy and disarm at the same time. . . .

While this whole quote provides a fascinating grounds of exploration, what really draws me in is the last sentence, because it feels like the crux of queer comedy and the humor that Ginsberg utilizes. Consider the poem Doty referenced, Ginsberg’s ode to his own asshole. He observed how the presentation of this poem defied the norms - for who else could write this poem and get away with it - and also disarmed - as the audience was led to laughter instead of discomfort or upset. Queer comedy is disruptive, yes, because it’s challenging the norms, but it disarms because in that challenge, it creates laughter. Through Perkins’ perspective, we see how Ginsberg’s humor fits so very well into our greater understanding of queer comedy.

1 note

·

View note