#native North American insect species

Text

Bzzz!

Just some bees in my garden and in the fields and on a neighbourhood walk. :)

Featured bees include bumblebees (native), green sweatbees (native), honeybees (invasive), carpenter bees (native), and some I'm not sure about.

Featured flower hosts include bull thistles (invasive weed), rose of sharon (invasive), New England aster (native), cup plant (native), starthistle (not native), Nuttall's sunflower (native), purple coneflower (native), anise hyssop (native), white wood aster (native), swamp milkweed (native), sow thistle (invasive weed), creeping charlie (invasive), creeping thistle (invasive weed), wild rose (native maybe), wild bergamot (native), bride's feathers (native), bigleaf lupin (native maybe or invasive), and upright prairie coneflower "Mexican hat" (native species, but a cultivar).

All my photos, unedited. Don't mind the weirdness of the third last photo. It's my phone's "portrait" which I found out belatedly can have, uh, interesting results.

#bees#bumblebees#insects#hymenoptera#bees wasps and ants#honeybees#sweatbees#carpenter bees#my photos#photography#blackswallowtailbutterfly#bees on flowers#flowers#native North American plant species#native North American insect species#thistles#milkweed#sunflower#purple coneflower#upright prairie coneflower#swamp milkweed#lupin#bigleaf lupin#asters#New England aster#white wood aster#coneflowers#wild rose#starthistle#creeping charlie

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Racket Tailed Emerald (Dorocordulia libera)

Gorgeous dragonfly who graciously stopped to pose for me the other day. Others in this genus are also referred to as “Little Emeralds” and are native to North America.

This is a juvenile, makes sense with the time of year! Later on, the eyes become a bright emerald green.

edit: I used to assume it was a male, it is 100 percent a female!

#racket tailed emerald#dragonfly#dorocordulia libera#corduliidae#odonata#nature#nature photography#insects#bugs#entomology#buglr#North American species#native species#my photos

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Chemically sterilized...or mechanically sterilized?

It is clear that applying chemicals to your yard and landscape, be it fertilizers, weed killers, or pesticides, has devastating effects to the community of life that is present in every place.

But is the terrifying decline in insects explainable by chemicals alone?

When i am in mowed environments, even those that I know have no lawn chemicals, they are almost entirely empty of life. There are a few bees and other insects on the dandelions, but not many, and the only birds I see are American robins, Grackles, and European starlings.

Even without any weed killers at all, regular mowing of a lawn type area eliminates all but a few specially adapted weeds.

The plants of a lawn where I live include: Mouse ear chickweed, Birds-eye Speedwell, Common blue violet, Dandelion, Wild Garlic, Creeping charlie, White Clover, Black Medick, Broad-leaved plantain, Mock Strawberry, Crabgrass, Small-flowered Buttercup, Ribwort Plantain, Daisy Fleabane, a few common sedges, Red Deadnettle...That sounds like a lot of plants, but the problem is, almost all of them are non-native species (Only Violets, Daisy Fleabane, and the sedges are native!) and it's. The Same. Species. Everywhere. In. Every. Place.

How come...? Because mowed turf is a really specific environment that is really specifically beneficial to a number of almost entirely European plants, and presents stressors that most plants (including almost all native north american plants) simply can't cope with.

The plants mentioned above are just the flowering weeds. The grasses themselves, the dominant component of the lawn, are essentially 100% invasive in North America, many of them virulently and destructively invasive.

Can you believe that Kentucky bluegrass isn't even native to Kentucky? Nope, it's European! The rich pasture of the Bluegrass region of Kentucky was predominantly a mix of clover, other legumes, and bamboo. The clovers—Kentucky clover, Running buffalo clover, and buffalo clover—are highly endangered now (hell, kentucky clover wasn't even DISCOVERED until 2013) and the bamboo—Giant rivercane, Arundinaria gigantea—has declined in its extent by 98%. Do European white and red clovers fulfill the niches that native clovers once did? Dunno, probably not entirely.

One of the biggest troubles with "going native" is that North America legitimately does not have native grass species that really fill the niche of lawn. Most small, underfoot grassy plants are sedges and they are made for shady environments, and they form tufts and fancy sprays, not creeping turf. Then there's prairie grasses which are 10 feet tall.

What this means, though, is that lawns don't even remotely resemble environments that our insects and birds evolved for. Forget invasive species, lawns are an invasive BIOME.

It's a terrible thing, then, that this is just what we do to whatever random land we don't cover in concrete: back yards, road margins, land outside of churches and businesses, spaces at the edges of fields, verges at bypasses and gas stations...

Mowing, in the north american biomes, selects for invasive species and promotes them while eliminating native species. There's no nice way to put it. The species that thrive under this treatment are invasive.

And unfortunately mowing is basically the only well-known and popular tool even for managing meadow and prairie type "natural" environments. If you want to prevent it from succeeding to forest, just mow it every couple of years.

This has awful results, because invasive species like Festuca arundinacea (a plant invented by actual Satan) love it and are promoted, and the native species are harmed.

Festuca arundinacea, aka Tall Fescue, btw is the main grass that you'll find in cheap seed mixes in Kentucky, but it's a horrific invasive species that chokes everything and keeps killing my native meadow plants. It has leaves like razor blades (it's cut me so deeply that it scarred) and has an endosymbiont in it that makes horses that eat it miscarry their foals.

And this stuff is ALL OVER the "prairie" areas where I work, like it's the most dominant plant by far, because it thrives on being mowed while the poor milkweeds, Rattlesnake Master and big bluestems slowly decline and suffer.

It's wild how hard it is to explain that mowing is a very specific type of stressor that many plants will respond very very negatively to. North American plants did not evolve under pressures that involved being squished, crushed, snipped to 8 inches tall uniformly and covered in a suffocating blanket of shredded plant matter. That is actually extremely bad for many of the prairie plants that are vital keystone species. Furthermore it does not control invasive species but rather promotes them.

Native insects need native plant cover. Many of them co-evolved intimately with particular host plants. Many others evolved to eat those guys. And Lord don't get me started on leaf removal, AKA the greatest folly of all humankind.

So wherever there is a mowed environment, regardless of the use of chemicals or not, the bugs don't have the structural or physical habitat characteristics they evolved for and they don't have the plant species they evolved to be dependent on.

Now let's think about three-dimensional space.

This post was inspired when I saw several red winged blackbirds in the unmowed part of a field perching on old stems of Ironweed and goldenrod. The red-winged blackbirds congregated in the unmowed part of the field, but the mowed part was empty. The space in a habitat is not just the area of the land viewed from above as though on a map. Imagine a forest, think of all the squirrels and birds nesting and sitting on branches and mosses and lichens covering the trunks and logs. The trees extend the habitat space into 3 dimensions.

Any type of plant cover is the same. A meadow where the plants grow to 3 feet tall, compared with a lawn of 6 inches tall, not only increases the quality of the habitat, it really multiplies the total available space in the habitat, because there is such a great area of stems and leaves for bugs and birds to be on. A little dandelion might form a cute little corner store for bugs, A six foot tall goldenrod? That's a bug skyscraper! It fits way more bugs.

It's not just the plants themselves, it's the fallen leaves that get trapped underneath them—tall meadow plants seem to gather and hoard fallen leaves underneath. More tall plants is also more total biomass, which is the foundation of the whole food chain!

Now consider light and shade. Even a meadow of 3ft tall plants actually shades the ground. Mosses grow enthusiastically even forming thick mats where none at all could grow in the mowed portions. And consider also amphibians. They are very sensitive to UV light, so even a frog that lives in what you see as a more "open" environment, can be protected by some tall flowers and rushes but unable to survive in mowed back yard

#anti lawn#kill your lawn#native plants#the ways of the plants#native plant gardening#plants#random#bitching about mowing again

867 notes

·

View notes

Text

Making Better State Insects

So at some point I stumbled across a list of State Insects. Honestly I wasn't even aware states had "state insects", but as I looked down the list my disappointment grew. A vast majority of states had selected the European honeybee (which is not even native) as their state insect, with monarch butterflies and ladybugs being the two runner ups. I thought this was a damn shame because there's so many interesting insects in the US, so I'm making a better official new list of state insects.

For this list my criteria are:

Insect must be native to the state

No repeats

Insect must be easily observable to the naked eye

I also had general guidelines of picking insects that were relatively common (based on inaturalist heat maps of observation) and picking insects that were cool or interesting. Some of these insects I picked because I thought they were important parts of the areas culture and experience (lovebugs, toebiters, and periodical cicadas) and some insects I picked just to raise awareness that they exist in the US.

I also don't think I gave anyone huge L's, no mosquitoes, louses, cockroaches, ect, because my goal of this list is to get people interested in their native insects and I want it to be fun to find and observe your state insect.

Also some states get gold stars for picking state insects that already meet these criteria and are cool so they get to keep theirs. Some states also have "state butterflies" or "state agricultural insect" which for this list I'm ignoring, you can keep those I'm just focused on state insects. Slight disclaimer also, I've only ever lived in California, Nevada, Oregon, Washington, and South Carolina, and all these states are keeping their original state insect. So all the insects I'm choosing are for states I haven't lived in. Also I'm not including photos in this post just for my own sanity.

List under the cut!

Alabama

Old: Monarch Butterfly

New: Giant Leaf-footed Bug (Acanthocephala declivis)

Leaf-footed bugs are cute, they're big, they're stanced up, the males have big back legs, you've probably seen them. Being true bugs they have piercing mouthparts and suck plant juices.

Alaska

Four-spot Skimmer (Libellula quadrimaculata)

Alaska gets to keep their old state insect, it's a cool dragonfly and apparently was partially chosen to honor bush pilots who fly to deliver supplies in the Alaskan wilderness, so really cool!

Arizona

Two-tailed swallowtail butterfly (Papilio multicaudata)

Arizona also gets to keep their state insect. Kind of a shame because Arizona has a lot of cool species, but it did meet my requirements and they get points for choosing a different kind of butterfly.

Arkansas

Old: European honeybee

New: North American Wheel Bug (Arilus cristatus)

One of the largest assassin bugs in the US, these guys are appreciated by gardeners for their environmentally friendly pest control. They also look badass.

California

California Dogface Butterfly (Zerene eurydice)

Endemic to California and on a stamp! Again, kind of a shame because there's a lot of cool insects in California, but I respect this choice, especially since California was the first state to designate a state insect (1929).

Colorado

Colorado Hairstreak Butterfly (Hypaurotis crysalus)

Same deal as California, the state's name is in the common name, unique butterfly found in the four corners region. Just get a stamp or something soon!

Connecticut

Old: European Praying Mantis

New: Cecropia Moth (Hyalophora cecropia)

You picked a state insect no one else had but went with a nonnative mantis? Here's an insect that'll make you stand out and it's a native species. Lesser known than some of the other giant silk moths, the Cecropia moth is the largest native moth and has some truly stunning colors.

Delaware

Old: Convergent Ladybeetle

New: Periodical Cicada (Magicicada septendecim)

Cicada's had to be somewhere on this list and Delaware was one of the main hotspots for brood X, one of the largest broods of the multiple staggered brood cycles. Hey, they have a lot of history in America. Accounts go back as early as 1733, with Thomas Jefferson and Benjamin Franklin making a note of them.

District of Columbia

Old: None

New: Monarch Butterfly (Danaus plexippus)

The Entomological Society of America is trying to get the Monarch Butterfly added as our national insect, so I think that's reason enough to let DOC claim it.

Florida

Zebra Butterfly (Heliconius charithonia)

Florida gets to keep their state butterfly, but the populations that have existed in Florida are in steep decline. Ideally I would want being the official state insect to come with some protections, hopefully people can get invested in reintroducing them.

Georgia

Old: European Honeybee

New: Horned Passalus Beetle (Odontotaenius disjunctus)

Also called bess beetles or patent-leather beetles, these cute guys are important for forest systems because they eat decaying wood, helping to break down felled trees. They're cute beetles that squeak when disturbed.

Hawaii

Kamehameha Butterfly (Vanessa tameamea)

An endemic Hawaiian butterfly named after a ruling dynasty of Hawaii. Their population is under threat, as with a lot of native Hawaiian species, so I think this is a good state insect to build protections and activism around.

Idaho

Old: Monarch Butterfly

New: Ice Crawler (Grylloblatta sp. "Polaris Peak")

Look Idaho, I have to admit that even though I've traveled extensively through WA, OR, CA, and NV I've never stepped foot in Idaho and I don't intend to. Your state exists in a weird liminal zone, not really the pacific northwest but not really whatever Montana is either. Your state isn't even all in one time zone. So look, I really wanted ice crawlers to be on this list, but they're exclusively found on mountains in the pacific northwest and Sierra Nevadas. Normally I would've given them to Washington or Oregon, but those states already have state insects that work for them. So your state gets ice crawlers, and they do exist in Idaho in the panhandle. It's not an L, ice crawlers are amazing extremophiles that crawl over snow in high elevation mountain peaks. They exist in their own unique order and theres only one genus in the US, with different species being region locked, sometimes onto specific mountains. Their thermoregulation is so delicate, the warmth of someones hand holding them causes them to over heat and die. They're cool, unique, and weird, and let's face it so is your state. At least I didn't take a cop out by picking the potato bug.

Illinois

Old: Monarch Butterfly

New: Red-banded Leafhopper (Graphocephala coccinea)

Leafhopper done Chicago style.

Indiana

Old: Say's Firefly

New: Common True Katydid (Pterophylla camellifolia)

I wanted to give you Say's Firefly. I really did. But when I looked on Inaturalist not A SINGLE OBSERVATION was listed for the species in Indiana. I'm even going to post pictures.

So even though this is extremely funny I'm giving your state the Common True Katydid instead. Large, loud, and easy to spot, these guys can frequently be heard chirping in trees. Not only do different populations have different rates of chirp, but the rate of chirp is also so predictably dependent on temperature that you could make an equation to tell the temperature based on chirp rate.

Iowa

Old: None

New: Westfall's Snaketail (Ophiogomphus westfalli)

Really cool clubtail dragonfly that's almost exclusively found in Iowa, Missouri, and Arkansas.

Kansas

Old: European Honeybee

New: Rainbow Scarab (Phanaeus vindex)

A kind of true dung beetle, they play an important role in removing waste. And although they don't roll waste like the stereotypical dung beetles, they are extremely pretty.

Kentucky

Viceroy Butterfly (Limenitis archippus)

This is fine.

Louisiana

Old: European Honeybee

New: Lovebug (Plecia nearartica)

Look, one of the southern states was going to get this one and Louisiana has a majority of the observations for them. Although annoying, it's things like having to scrape thousands of flies off your car that makes the Southern experience. Embrace it!

Maine

Old: European Honeybee

New: Brown Wasp Mantidfly (Climaciella brunnea)

I really wanted these guys to be somewhere on the list. Neither a wasp, mantis, or fly, these are predatory neuropterans related to lacewings. They have raptorial front legs (resembling a mantis) and their coloration resembles paper wasps that they live alongside. Weird, unique, and wonderful!

Maryland

Baltimore Checkerspot Butterfly (Euphydryas phaeton)

This butterfly might've been picked for the resemblance of the state flag. It's in decline in it's native range, so hopefully more awareness and consideration to state insects will help push conservation efforts.

Massachusetts

Old: Ladybug

New: Hornet Clearwing Moth (Paranthrene simulans)

Hornet mimic moth, the caterpillars feed on chestnuts and oaks. All lepidopterans (moths and butterflies) have modified hairs on their wings that form the "scales" that give this order their name. For this moth though, parts of it's wings don't have any scales so it more convincingly resembles a hornet. Underneath the scales, butterfly and moth wings look pretty much like any other insect's wing. Cool!

Michigan

Old: None

New: American Salmonfly (Pteronarcys dorsata)

The biggest salmonfly in North America. They make excellent fishing bait, and several fly fisherman use salmonfly lures to catch trout. Their nymphs are also an important indicator of water quality, with them being one of the first species to disappear in the presence of pollution or contaminants.

Minnesota

Old: Monarch Butterfly

New: American Giant Water Bug (Lethocerus americanus)

Also one of the ones that had to be on the list somewhere, and the Inat heatmap says Minnesota. Toebiters are part of the experience, and they are cool and ferocious looking.

Mississippi

Old: European Honeybee

New: Eastern Eyed Click Beetle (Alaus oculatus)

Click beetles have a cool adaption that allows them to launch themselves in the air to avoid predators. This makes an audible sound, hence their common name. The Eastern Eyed Click Beetle is one of the largest and most striking click beetles in the US, with large false eyespots on their thorax.

Missouri

Old: European Honeybee

New: Goldenrod Soldier Beetle (Chauliognathus pensylvanicus)

A soldier beetle that feeds on aphids and small plant pests, these beetles also eat pollen and nectar from flowers. They don't harm the flower, and though their common name reflects their preference for goldenrod flowers, they're also an important pollinator of the prairie onion (Allium stellatum). This is a native species of onion that grows from Minnesota to Arkansas.

Montana

Old: Mourning Cloak

New: Western Sheep Moth (Hemileuca eglanterina)

Mourning Cloak butterflies do technically work for my criteria, but I wanted to showcase some more regional insects in this as well, as Mourning Cloaks are found throughout North America and Eurasia. The Western Sheep Moth is an absolutely stunning giant silk moth, found throughout the western United States. Although not as big as some other silk moths, the bold orange and black coloration on these make them absolutely stand out.

Nebraska

Old: European Honeybee

New: Blowout Tiger Beetle (Cicindela lengi)

A tiger beetle with unique patterns, these guys are active predators and are particularly difficult to spot because they run extremely quickly. They seem to be pretty cold tolerant and exist from Colorado up into Canada.

Nevada

Vivid Dancer Damselfly (Argia Vivida)

This damselfly was picked as Nevada's state insect because it's widespread throughout the state and matches the state colors, silver and blue. That gets my seal of approval!

New Hampshire

Two-spotted Lady Beetle (Adalia bipunctata)

This is fine.

New Jersey

Old: European Honeybee

New: Margined Calligrapher (Toxomerus marginatus)

A pretty hoverfly, they strongly resemble bees in both looks and behavior. Larvae feed on common plant pests such as thrips and aphids, while the adults sip nectar and pollinate flowers. These helpful attributes make it something the Garden State can appreciate!

New Mexico

Tarantula Hawk (Pepsis grossa)

New Mexico wins the official state insect list by a landslide. Not only is the tarantula hawk a super cool and formidable insect to showcase, but New Mexico's state butterfly (Sandia Hairstreak) was discovered in New Mexico. No notes 10/10!

New York

Nine-spotted Lady Beetle (Coccinella novemnotata)

A native species of lady beetle that's been in decline in recent years, New York is one of the last remaining states where they've been spotted. I also appreciate that New York designated a specific ladybug species instead of just saying "Coccinellidae species".

North Carolina

Old: European Honeybee

New: Eastern Rhinoceros Beetle (Xyloryctes jamaicensis)

A large native species of rhinoceros beetle. They breed in ash trees, and are under threat due to competition from the Emerald Ash Borer.

North Dakota

Old: None

New: Nuttall's Blister Beetle (Lytta nuttalli)

As with all blister beetles, these guys have a chemical defense. Unlike the more famous Bombardier Beetle thought, instead of being black and red they are iridescent red/purple and green.

Ohio

Old: Ladybug

New: Bald-faced Hornet (Dolichovespula maculata)

Look, when the one thing everyone knows about your state is that it sucks, it's time to lean into it. Bald-faced hornets, everyone knows them, everyone has opinions about them, and they get a lot of attention. I don't think I have to explain this one anymore.

Oklahoma

Old: European Honeybee

New: Giant Walking Stick (Megaphasma denticrus)

The largest insect in the United States. Being a native walking stick, they're less damaging than the imported invasive walking sticks that are heavily controlled.

Oregon

Oregon Swallowtail Butterfly (Papilio oregonius)

Oregon in the common name and in the species name, and also has a stamp!

Pennsylvania

Pennsylvania Firefly (Photuris pensylvanica)

Pennsylvania in the common name and species name. If fireflies weren't already on this list I would've made sure to include them somewhere.

Rhode Island

American Burying Beetle (Nicrophorus americanus)

When I saw this on the list I was worried. American Burying Beetles are one of my favorite insects, but they're extremely endangered now. I also thought they existed more in the midwest, so I was worried I would have to change this one because it violated the "native to the region" rule. But! To my pleasant surprise, not only did their historic range extend to Rhode Island, but there is actually a carefully maintained wild population on Block Island. They estimate between 750-1000 individuals live there, making it one of the few remaining places where the American Burying Beetle still exists. Excellent work Rhode Island!

South Carolina

Carolina Mantis (Stagmomantis carolina)

This is fine. I wanted to give South Carolina the Palmetto bug but they're actually not native.

South Dakota

Old: European Honeybee

New: Golden Northern Bumble Bee (Bombus fervidus)

"Save the bees" should really be focused on native pollinators, many of whom are in decline. There are a lot of species of native bee you can feature as a state insect, with the Golden Northern Bumble Bee being a particularly large and striking species.

Tennessee

Old: Firefly and ladybug

New: Black-waved Flannel Moth (Megalopyge crispata)

Seriously look them up, these guys are adorable.

Texas

Old: Monarch Butterfly

New: Rainbow Grasshopper (Dactylotum bicolor)

It was really hard to pick an insect for your state. The Texas Unicorn Mantis was a contender but I eliminated it because it's really only found in the southern part of Texas, so it was between the Rainbow Grasshopper and the Eastern Velvet Ant (or Cow Killer). I went with the Rainbow Grasshopper because it's more wide spread and common, and occurs everywhere except the east part of Texas. But the Eastern Velvet Ant only occurs on the east part of Texas, maybe you should get an East and West Texas insect? I also thought more people have probably already heard of the Eastern Velvet Ant than the Rainbow Grasshopper, which is a shame because they're super interesting to look at.

Utah

Old: European Honeybee

New: Mormon Cricket (Anabrus simplex)

Mormon Crickets are not true crickets, and instead closer related to katydids. Their common name comes from an early account of Latter-day Saint settlers in Utah. In 1848, a swarm of Mormon Crickets decimated the settler's crops, so the legend goes that they prayed for relief from this plague of insects. Later that year, a swarm of gulls appeared and ate the crickets, thus saving the crops. This is recounted in the "miracle of the gulls" story. To recognize their contributions, the California Gull is commemorated as Utah's state bird. I thought it was fitting then that the Mormon Cricket be recognized as your state insect.

Vermont

Old: European Honeybee

New: Long-tailed Giant Ichneumon Wasp (Megarhyssa macrurus)

A pretty wasp with an extremely long ovipositor, these wasps are common in deciduous forests across the eastern United States. They can't sting, and instead use their long ovipositor to stab into tree bark and deposit eggs on the horntail larvae that burrow into the trees.

Virginia

Old: Eastern Tiger Swallowtail Butterfly

New: Giant Stag Beetle (Lucanus elaphus)

A large stag beetle native to the Eastern United States. Although not as well known as their similar looking fellow stag beetles from Japan, these guys are a lovely chocolate brown instead of solid black. Like most stag beetles, they breed in decaying wood.

Washington

Green Darner Dragonfly (Anax junius)

I imagine this was chosen because it matches the flag.

West Virginia

Old: European Honeybee

New: Appalachian Tiger Beetle (Cicindela ancocisconensis)

This tiger beetle likes hilly terrain. As with all tiger beetles, they can be hard to spot because they run across the ground in search of prey. They are fast! But this can make it more rewarding when you finally catch up to one.

Wisconsin

Old: European Honeybee

New: Phantom Crane Fly (Bittacomorpha clavipes)

Don't believe old wive's tales about crane flies drinking gallons of blood, they are nonbiting. Those striking black and white legs are hollow, and are held out when they fly, making an extremely distinct sight that's been likened to sparklers or snowflakes.

Wyoming

Sheridan's Hairstreak (Callophrys sheridanii)

This is fine.

#insect#insects#state insect#long post#list#text post#entomology#bugblr#invertebrates#invertiblr#inverts#invert

190 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Groove-Billed Ani (Crotophaga sulcirostris)

Family: Cuckoo Family (Cuculidae)

IUCN Conservation Status: Least Concerned

While many species of cuckoos are brood parasites that trick other birds into incubating their eggs and raising their young, the 3 species of large-billed, black-feathered cuckoos in the genus Crotophaga, known collectively as Anis, are not, and the Groove-Billed Ani (notable for being possibly the most common Ani species) is no exception: every Groove-Billed Ani lives in a small social group consisting of 4-10 individuals, with the number of individuals in a group always being even. This even numbering is the result of the way the flock is organised, as each flock is made up of 2-5 pairs of mates, and while each individual will only breed with their mate all individuals in the group work to establish and defend a shared territory and to construct a large, cup-shaped shared nest into which every female in the flock will lay eggs. Found in grasslands, shrublands and other open habitats, the Grooved-Billed Ani is native to much of northern South America and southern North America (although on occasion it may be observed as far south as northern Argentina and as far north as Canada as a vagrant) and feeds on fruits, seeds, insects and small vertebrates, with its large and extremely powerful beak being well suited to breaking hard seed shells as well as the exoskeletons and bones of prey. Throughout the majority of its range this species is resident (non-migratory), but in the northernmost extremes of its North American range it may seasonally travel south to avoid cold weather and low resource availability during the winter.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------

Image Source: https://www.inaturalist.org/taxa/1972-Crotophaga-sulcirostris

#Groove-Billed Ani#ani#anis#cuckoo#cuckoos#bird#birds#zoology#biology#ornithology#animal#animals#wildlife#South American wildlife#North American wildlife

932 notes

·

View notes

Text

Salix discolor (American pussy willow)

The catkins of this pussy willow (Salix discolor) is another sure sign of early spring and they're the only flower I can think of that wears a fur coat. Pussy willows use these silky fibers as insulation to keep their catkins protected in late winter. This species is native to North America in a wide band that runs, coast-to-coast, through southern Canada and the northern lower United States.

Plants know when to flower by measuring the air temperature and the length of day. A brief warm period in the winter will not be enough for pussy willows- they need longer days too. Then, when the timing is perfect - boom they bloom!

As with so many spring flowering trees, willows produce flowers before they leaf-out. Male and female catkins grow on different plants. The appearance of yellow anthers indicates that this one is a boy and it's just about to start producing pollen. Willows are insect-pollinated and this means that hungry worker bees will soon wake up and these pussy willows will immediately get their full attention.

#flowers#photographers on tumblr#pussy willows#spring flowers#catkins#fleurs#flores#fiori#blumen#bloemen#Native plants#my garden#recommendation: "What a plant knows” by Daniel Chamovitz#Vancouver

74 notes

·

View notes

Text

Bison are often associated with North America, but the wisent (Bison bonasus) is native to Europe. It was driven to extinction in the wild in the early 20th century (it had been extirpated from western Europe for several centuries), but reintroduction efforts began a few decades later.

As with American bison (Bison bison), the wisent is an important keystone species, and its reintroduction stands to benefit the ecosystems it is returning to. As browsers, wisent help keep plant growth in check, and their manure is valuable both for the plant community as well as detritivores and decomposers like various insects, fungi, and microbes. Native large carnivores are generally as scarce as the bison, but in places where wolves and other predators still exist, the bison could be important sources of food.

The hard truth about restoration ecology is that we will never be able to get ecosystems back to how they were before humans so heavily altered them. We can't even necessarily return them to when our impact was much lighter, given all the changes we have made. But if we can at least create pockets of biodiversity with safe travel corridors between them, that will go a long way in at least keeping native wildlife from disappearing entirely. The reintroduction of the wisent in Europe, and the bison in North America, represent important steps in undoing at least a little of the damage done.

#wisent#bison#bovidae#European bison#endangered species#extinction#ecology#restoration ecology#habitat restoration#keystone species#mammals#nature#wildlife#animals#environment#conservation#science#scicomm#rewilding

94 notes

·

View notes

Text

February 2nd, 2024

Thick-legged Hoverfly (Syritta pipiens)

Distribution: Native to Europe, but found throughout Eurasia and North America.

Habitat: Occur wherever there are flowers, but most common around human habitations; common habitats include farmland, gardens and parks. Larvae are most common in rotting organic matter such as compost, manure, silage, and occasionally cadavers.

Diet: Larvae feed on decaying organic matter, while adults feed on many types of flowers. Their most common food plants are water-willow, white vervain, American pokeweed and candyleaf.

Description: The thick-legged hoverfly is called so due to their overdeveloped hind legs. These insects can sometimes be pests, as they occasionally feed on ornamentals, but are generally considered beneficial because they pollinate many common flower species. They also act as bio-indicators, especially to demonstrate the effects of environmental changes on pollinators.

Hoverflies are very agile fliers, and are often found hovering near flowers. This species, however, is very rarely found flying more than a metre above ground level. When they encounter another fly, males will sometimes circle around them; if they're male, this often results in the two males circling eachother, and if they're female, the male may dive at her at an acceleration of up to 500 centimetres per second squared in an attempt to initiate copulation.

Images by Joaquim Alves Gaspar and Stephen Luk.

65 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hey I thought you might appreciate a heads up that the yellow-legged hornet (Vespa velutina) has been spotted in Savannah, Georgia. 😞

Nice. Well, not nice news. But glad that you thought of me. Thank you.

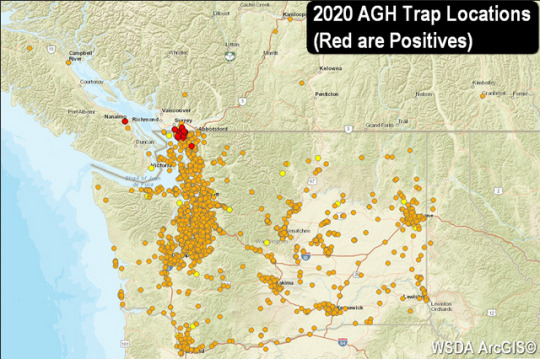

(For other people who have yet to fully embrace and explore their innate love of hornets, this Vespa velutina hornet is originally from Southeast Asia. This creature is closely related to Vespa mandarinia, the creature derisively referred to in the US as "murder hornet" or "Asian giant hornet", originally from South/East Asia, which is now apparently established near in the Salish Sea region near Bellingham, Vancouver, and Nanaimo.)

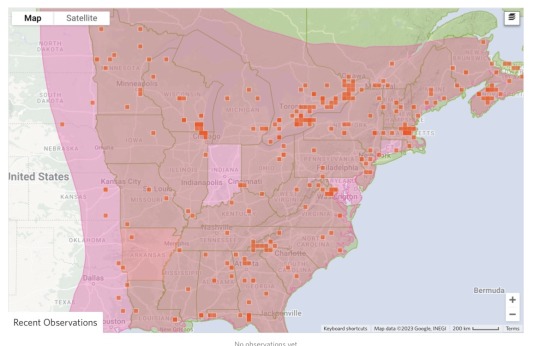

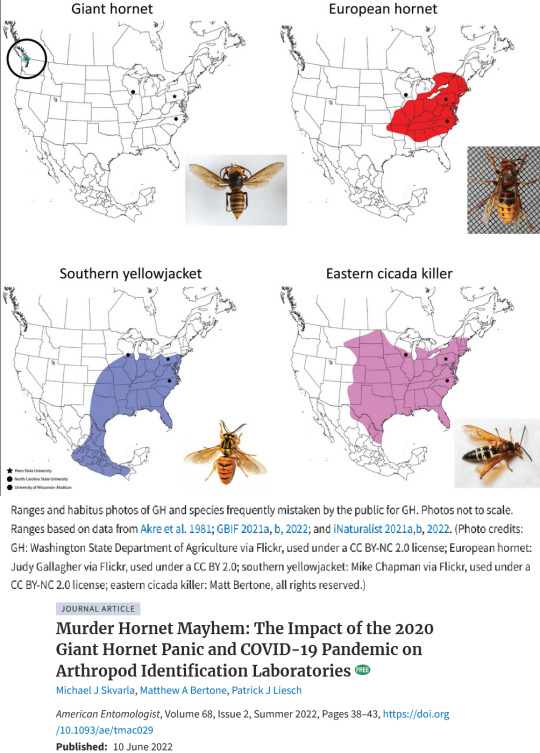

Here's a look at where the giant hornets now live in North America, along with the distribution of some other large hornets which might be mistaken as Vespa manadrinia/velutina:

The map was originally published in 2022 in American Entomologist, displaying distribution range of (non-native) giant hornet; (non-native) European hornet; (native) southern yellowjacket; and (native) eastern cicada killer. The article also identifies a few few other species which might be mistaken for "murder hornets": great golden digger wasp, bald-faced hornet, German yellowjacket, red-legged cannibal fly, and pigeon horntail. (Available to read for free online; article title in the source/caption beneath the map.)

I've had many memorable encounters with large (native) bald-faced hornets in dense cedar-hemlock rainforest-y places. And coincidentally, the Pacific Northwest is also now apparently the North American home/homebase of Vespa mandarinia. So here are some other PNW wasps/hornets in comparison, from Oregon State University Extension Catalog (2022):

From 2020 research on potential dispersal of Vespa mandarinia over a couple of decades (not necessarily a good or realistic representation, not inevitable, kinda just "potential"):

Apparently Vespa mandarinia haven't yet been encountered outside of the general Vancouver area during targeted samples:

I know that you too are fond of wasps/hornets, and are aware of their popular demonization, the way that they're feared, etc. In July 2022, the Entomological Society of America put out an online resource thing that explains why they don't like the name "Asian giant hornet" for Vespa mandarinia and Vespa velutina, instead adopting "northern giant hornet" and "yellow-legged hornet" (which you called the creature, too!) because of the racialized/xenophobic implications. ("Northern Giant Hornet Common Name Toolkit" available at: entsoc.org/publications/common-names/northern-giant-hornet) They say: '"Murder hornet" unnecessarily invokes fear and violence, which impede accurate public understanding of the insect and its biology and behavior. While "Asian" on its own is a neutral descriptor, its association with a pest insect that inspires fear and is targeted for eradication may bolster anti-Asian sentiment in some people - at a time when hate crimes and discrimination against people of Asian descent in the United States are on the rise.'

Which, for me, brings to mind this recent book from Jeannie Shinozuka:

From the publisher's blurb: 'In the late nineteenth century, increasing traffic of transpacific plants, insects, and peoples raised fears of a “biological yellow peril” [...]. Over the next fifty years, these crossings transformed conceptions of race and migration, played a central role in the establishment of the US empire and its government agencies, and shaped the fields of horticulture, invasion biology, entomology, and plant pathology. [...] Shinozuka uncovers the emergence of biological nativism that fueled American imperialism and spurred anti-Asian racism that remains with us today. [...] She shows how the [...] panic about foreign species created a linguistic and conceptual arsenal for anti-immigration movements that flourished in the early twentieth century [...] that defined groups as bio-invasions to be regulated—or annihilated.'

A lot going on at that time with insects, empire, and xenophobia. In the 1890s, the British Empire was desperately searching for a way to halt malaria, and mosquitoes had just been discovered as vectors of malaria. And from Nobel prize podium lectures to popular media newspapers and academic journals, there was all kinds of talk about how "bacteria/viruses/insects are the greatest enemy of the Empire" and whatever. The US was also expanding in the Caribbean, Central America, Pacific islands towards East Asia, etc. Tropical plantations were proliferating, not just in Dutch Java or British India, but also in US administered Central America. And so insects were perceived not just as a threat to the human body of the British soldier or American administrator; insects were also a threat to profits, as insect pests threatened monoculture plantations and agriculture.

That same time period saw the US invasion of the Philippines and exports of products from the islands; the US annexation of Hawai'i, and elevating rivalry with Japan; the 1882 passage of the notorious Chinese Exclusion Act; US control of Cuba and Puerto Rico; expansion of US fruit corporations in Central America and US sugarcane plantations in Cuba/Hawai'i, where insect pests threatened plantation profits; the advent of "Yellow Peril" tropes and fear of invasion in science fiction literature; the detaining of half a million (mostly Chinese) people at the medical quarantine processing center that the US Public Health Service operated at Angel Island in San Francisco; and US insect extermination projects, mosquito control campaigns, and medical policing of local people in Cuba and the Panama Canal Zone (where US authorities detained local people for medical testing).

A lot to consider.

58 notes

·

View notes

Text

Spectember D27: Revamp the Dinosauroid

The end of the Triassic propitiated finally the dominance of dinosaurs in the next period with the rupture of the large supercontinent Pangea, though in this timeline something pushed further the fragmentation of the continent, and instead of just opening the rift of the Atlantic, it multiplied across Africa and a section of south America, making the Tr/J mass extinction more severe and killing out many more species of dinosaurs, so now the Jurassic was no longer dominated by the animals we have in our timeline, instead we get a strange variety of large dinosaur-like crocodiles, many sauropodomorphs that diverged from the smaller species that survived and never went into the same trend of gigantism as in our earth, many synapsids and so on.

At the end of the late Jurassic a lot happened with the new order, within some of the second radiation of sauropodomorphs included varied carnivorous carnosaur-like species, medium size coelurosaur-like omnivores and smaller herbivores that look like silesaurs; from the omnivore lineage that have expanded in varied niches would rise a branch of semiaquatic species that resembled something like a scaly penguin with hands, long finger and claws, with short robust tails, shorter necks and longer heads with narrow keratinized mouths.

They are remarkable as many other animals of this world, through one particular species seems to have started a peculiar evolutionary trend in the last 10 million years.

For the reader, we will refer to this species as the Shagoids, a species originated from 50 cm long aquatic sauropodomorph descendants that wandered on the estuaries of the now more fragmented north Africa/south American region, their ancestors were more of a mix of a cormorant with an otter as unlike the rest of its own family this belongs, as one main feature of these are they still functional forelimbs, these still preserved functional arms and hands that helped them to manipulate their prey of crustaceans and mollusks. Over time these developed strategies to break down their prey shell, including the habit of picking and using stones which choose appropriately for this task. This behavior was passed on to new generations, learned and properly helped them to get food with less effort, the food quality increased brain energy, brain size also increased and so their skills were forged much more adequately.

It was on matter of few million years the Shagoids lineage abandoned their swimming lifestyle and became mostly semi aquatic coastal dwellers, living in the shores and just entering water to hunt their food rather than spending most of their time there. As social animals they formed hierarchy groups, formed by the head of a dominant female around minor males that could either mate with her or just serve them, as well many other younger individuals, matriarchs often had the duty to select and organize hunting and spending of food, as well regulate reproduction and mating between their lower family, as she normally is the eldest of the group, and only another female of the same blood can turn into a elder matriarch of if mated by the son of the elder, this perhaps was the moment they gained proper sentience as how they defined a cultural and social structure.

It seems at the end rathe in a sudden change of sea level in the last 3 million years did the final push on their evolutionary journey, as most of the Shagoid populations got stranded within the main continent with almost no way to find new connections to large water bodies, in other situation their species would have die for starvation, but at that point they were already adapted to feed on other food sources, from tubers, insects and small animals, being able to cook them using fire they managed to craft, and so properly passed the harsh time with the loss of a chunk of their population over the sudden change.

When the Shagoid expanded and found again large water bodies far from their native regions, they really have changed considerable from their ancestors, as their closest relative was a sort of strange loon like reptilian species wandering in the coasts, these were more like limbed penguins with long arms and tridactyl hands, which the third finger being a derivation of the 4th an 5th clawless digit fused into one, their short legs lost their webbed feet a while ago and are more adapted for walking, their head still preserve the characteristic seabird like shape but their teeth have changed in shape to be generalistic omnivore, with a large head which houses the most intelligent brain in the planet.

Over the last thousands of years, they have been becoming more and more prone to establish permanent settlements populated by hundreds of them much more different of their wandering tribes, often farm plants and even carry some animals for domestication.

For the first time in their history they are in the pathway of civilization… who knows what will happen next, either the Shagoid can remain like this until their extinction, or they will start building towards the sky and beyond.

#speculative evolution#alternative evolution#triassic#jurassic#sauropodomorph#dinosauroid#sapient#spectember

34 notes

·

View notes

Text

Some Pollinator Appreciation

#flowers#bees#wasps#bumblebees#honeybees#insects#nature#entomology#I didn’t know purple coneflowers were native wildflowers to NA very cool#all of these are very common species but it’s still nice to see#there are more than just hymenopteran pollinators of course#purple echinacea#bombus impatiens#apis mellifera#apidae#dolichovespula arenaria#common aerial yellowjacket#vespidae#hymenoptera#north american species#introduced species#my photos

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Types of Bears:

Black Bears:

The American Black Bear (Ursus americanus) is a medium-sized bear species native to (you guessed it!) North America. Black Bears can be found in the forests as south as Florida and as North as Alaska. Being so widely distributed it’s no surprise that their population is twice the size of all the other bear species combined! Males generally weigh up to 500lbs, while females weigh up to 300lbs. The heaviest bear on record was found in North Carolina in 1998, weighing in at 880 lbs. Despite what their name may lead you to believe, they actually come in many different colors! They can be cinnamon, blonde, kermode or glacier bears as well as black! These bears are omnivores but their diet varies greatly depending on season, location, etc. They may eat berries, carrion nuts, insect larvae, fish, grasses, and small mammals. Although an adult Black Bear is quite capable of killing a person, they typically avoid any interaction or confrontations with humans. Attempts to relocate American black bears are typically unsuccessful, as the bears are able to return to their home range, even without familiar landscape cues.

Brown Bears:

The Brown Bear (Ursus arctos) is a species of large bear found across North America and Eurasia. In North America, the populations of brown bears are called grizzly bears, while the even larger subspecies that inhabits the Kodiak Islands of Alaska is known as the Kodiak bear. The largest populations are are in Russia with 120,000, the United States with 32,500, and Canada with around 25,000. Males generally weigh up to 600lbs , while females weigh up to 350lbs with the largest Brown Bear on record was a Kodiak that weighed 1,656 lbs. The Brown Bear is omnivorous and has been recorded consuming the greatest variety of foods of any bear. They may eat fish, carrion, insects, fungi, berries, flowers, nuts and small-medium sized mammals. Brown Bears do go out of their way to avoid humans but are much more likely to attack than Black Bears. They are formidable indeed, with females being extremely quick to aggression when with cubs.

Sloth Bear:

The Sloth Bear (Melursus ursinus), also known as the Indian bear, is a medium-sized bear species native to the Indian subcontinent. Their population inhabits the forests and grasslands of India, the Terai of Nepal, Bhutan and Sri Lanka. Males generally weigh up to 380lbs, while females weigh up to 210lbs with the biggest Sloth Bear on record weighing 423 lbs. Sloth Bears are considered myrmecophagous, meaning they feed on ants and termites. It has also been called the “labiated bear" because of its long lower lip and palate used for sucking up insects. They also may eat fruits and flowers. The Sloth Bear is one of the most aggressive bears alive which is likely due to the large human populations living so close to their habitats. These attacks are pretty frequent and if not fatal, the victim is often left terribly disfigured, as the bear strikes at the head and face.

Andean Bear:

The Andean Bear (Tremarctos ornatus) also known as the Spectacled Bear is a species of medium-sized bear native to the Andes Mountains in western South America. It is the only living species of bear native to South America, and the last remaining short-faced bear. Males generally weigh up to 340lbs, while females weigh up to 190 lbs with the largest Andean Bear on record weighing 440 lbs. Andean Bears are omnivores, eating small mammals, birds, and berries with their favorite foods being fruits and bromeliads. There have never been any reported attacks on humans.

Sun Bear:

The Sun Bear (Helarctos malayanus) is a species of small bear native to the tropical forests of Southeast Asia. They can grow up to be 150 lbs with males being 1/3 larger than the females. Sun bears get their name from the characteristic cream coloured chest patch! They are the most arboreal natured of all the bears with long claws fit for climbing trees. They feed omnivorously on insects, berries, fruits and mammals. They do not seem to hibernate, possibly because food resources are available the whole year throughout the range. Sun bears are shy and reclusive animals, and usually do not attack humans unless provoked to do so.

Polar Bear:

The Polar Bear (Ursus maritimus) is a species of large bear native to the Arctic Circle. Males generally weigh up to 1,200lbs, while females weighing up to 700lbs with the largest Polar Bear record weighing 2,209 lbs. Although most polar bears are born on land, they spend most of their time on the sea ice. Their scientific name means "maritime bear" and derives from this fact. Polar Bears are hypercarnivorous feeding primarily on ringed seals, but will also eat bearded seals, harp seals, hooded and harbor seals. Larger prey species such as walrus, narwhal and beluga are occasionally hunted. Due to location, attacks on humans are infrequent but potential chances of survival are very low. “If it’s black: fight back, if it’s brown: lay down, if it’s white: goodnight.”

(I'm experiencing a minor bear hyperfixation, if you can't tell!!! I hope this was beary educational for you ROFLROFLROFL)

#bear#bears#educational#grizzly bear#polar bear#black bear#spirit bear#sun bear#sloth bear#spectacled bear

107 notes

·

View notes

Note

hello!! i am so interested in all of the insects you keep!! they are all so lovely and fascinating thank you for sharing them! i am very interested in your centipede feeding on carrion! you mentioned previously that they are venomous, how many venomous insects do you have, if u mind sharing, as well would any of them have an effect if they happened to strike you/people in general? thank you!

I don’t have any venomous insects.

I have a lot of venomous myriapods, and four venomous arachnids. I haven’t been stung/bitten by any of them, except once by a small baby Scolopendra hainanum. it was only painful for a day or so, but a very strange bone-aching sensation from an animal barely two centimeters long.

my house centipedes are essentially harmless and lack the strength or size to piece human skin, and their venom is probably very mild. the scolopendrid centipedes I have vary from “bee sting” to “utterly excruciating” but effects seem to vary depending on individual. they’re not likely to kill though, centipede venom is painful but usually does not have lasting effects.

I don’t know much about the tarantulas/mygalomorphs I have since neither is prone to biting but I would imagine neither is much more painful than a bee sting.

my scorpions are probably the most seriously venomous animals I keep. a sting from Graciela would be very painful but probably not life-threatening if I’m not allergic. Scorpion Files says “C. gracilis from Cuba have a reported LD 50 value of 2.7 mg/kg, which is quite potent” but also mentions that the North American populations are less venomous than they are in their native range, though they don’t cite a source. the effects of the venom are poorly known for this species, but unlike other species in its genus I don’t think there are any documented fatalities.

I don’t really think about how my creatures are venomous on a daily basis though, at least towards me. it is easy to not get stung/bitten and the animals do not want to sting or bite anything except they prey they eat.

94 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Boat-Tailed Grackle (Quiscalus major)

Family: American Blackbird Family (Icteridae)

IUCN Conservation Status: Least Concern

Native to the southeastern USA, the Boat-Tailed Grackle shares much of its range with the closely related Common Grackle, but can be distinguished from its relative thanks to its larger size (Growing to be around 40cm/15.7 inches long compared to the around 32cm/12.6 inch long Common Grackle) and its considerably longer, broader tail, which is present in both sexes but more prominent in males. Found largely in coastal habitats (although they may also be found near large inland bodies of water or in human settlements where they feed on abandoned food scraps), members of this species roost in large, loosely organised flocks that may contain hundreds of individuals, and which scatter during the day to feed on seeds, fruits, insects, eggs and small vertebrates such as frogs, fishes and occasionally smaller birds before gathering back together at dusk. Boat-Tailed Grackles mate in the early spring (with a male establishing a strictly-guarded territory and producing a high-pitched mating call to invite a large number of females into it) and nest during the late spring and early summer (with several females constructing small, cup-shaped nests among dense elevated vegetation within close proximity to one another to increase the likelihood of potential predators and egg thieves being spotted, and 3-5 pale, speckled and striped eggs being laid in each nest.) Females of this species have pale brown bodies and dark brown wings, while males (such as the individual pictured above) are nearly twice the size of females and possess iridescent black feathers that reflect light in such a way that they may appear purple, blue or green if seen under bright sunlight. As is true of many grackles the males of this species are frequently mistaken for crows (with the word grackle being derived from the Latin graculus, meaning “jackdaw”, in reference to the two small species of Eurasian crows known collectively as jackdaws), but despite their superficial similarities grackles and crows are not closely related (with grackles and their fellow American Blackbirds being more closely related to the American Sparrows of the family Passerellidae.)

--------------------------------------------------------------------------

Image Source: https://www.inaturalist.org/taxa/9601-Quiscalus-major

(Side note: Some of the sources I’ve read about grackles seem to suggest that they’re among the most common passerine birds in North America, but I’m curios as to how true that is. I don’t suppose anyone who sees this post and lives in/has been to America can confirm or deny this?)

#Boat-Tailed Grackle#grackle#grackles#blackbird#blackbirds#icterids#icteridae#bird#birds#zoology#biology#ornithology#animal#animals#wildlife#north american wildlife

251 notes

·

View notes

Text

Euphorbia myrsinites (donkey tail, myrtle spurge, blue spurge)

Handle with Care

I've always called this plant a donkey tail but it's probably better known as myrtle spurge. Euphorbia is a big genus with over 2000 species but I'm afraid that donkey tail is 'the bad boy of the family'. It's native to Italy, the Balkans and Turkey but it's considered a noxious weed in Utah, Oregon and Colorado. According to the Salt Lake County Weed Control Program, "Small infestations can be controlled through multiple years of digging up at least 4" of the root. Myrtle spurge is best controlled in the spring when the soil is moist and prior to seed production. Make sure to dispose of all the plant parts in the garbage instead of composting." Goggles and rubber gloves are strongly advised.

Why all this heavy security? All Euphorbias produce a poisonous sap which burns the skin and can cause blindness if it gets in your eyes. If you eat the leaves, you get vomiting and severe diarrhea. This milky sap is a very good defense against any type of herbivore. Donkey tail in particular is extremely toxic to: humans, cattle, sheep, pets etc. etc. Rabbits and deer won't go near it. It has no known North American insect pests. Not surprisingly, it should never be planted next to a playground.

On the other hand, donkey tail is a common ornamental plant and widely available in local plant shops. Euphorbia myrsinites has also been awarded the Royal Horticultural Society's, Award of Garden Merit. It has attractive blue foliage, a very long blooming period and thrives in poor soil. But pleased be advised: Handle with Care.

#flowers#photographers on tumblr#donkey tail#Euphorbia#noxious weeds#fleurs#flores#fiori#blumen#bloemen#Vancouver

69 notes

·

View notes

Text

Species You Didn’t Know Weren’t Native to North America

There are some species found here in North America that are so common that many people just assume they’re part of the native menagerie. They’re naturalized, which means they’re non-native but have managed to establish reproducing populations here. Some may also be considered invasive, in that they aggressively compete with native species and may even displace them in some places.

I know some of you readers will already be familiar with the fact that the following species aren’t native here. But I bet there’ll be surprises for the rest of you! Let’s see who our not-actually-natives are.

Ring-necked Pheasant (Phasianus colchicus)

Hunters across the continent have long hunted pheasants for the table. First introduced in 1773–exactly 250 years ago–they have since made themselves at home in fields and meadows. While the largest populations can be found in the Midwest, especially the Great Plains states, they can be found throughout the United States, with additional scattered populations in southern Canada and Mexico.

While sometimes assumed to have integrated into their introduced habitats, pheasants actually wreak havoc on native game birds like quail and grouse. They compete for suitable food and nest sites, and may also practice nest parasitism, laying their eggs in other birds’ nests. This competition has led to decreases in native bird populations, as has the spreading of diseases that the pheasants tolerate, but which decimate other species. Pheasants will even attack and kill other birds.

So what other species made the list? Keep reading to find out!

Cross Orb Weaver (Araneus diadematus)

Fall is cross orb weaver time, and I run into these spiders constantly–sometimes literally, depending on how inconveniently their webs are placed! By that time of year, they’ve grown large enough to be noticeable, and their orange and brown coloration looks rather festive.

While I haven’t been able to find any indication that these spiders have a deleterious effect on their introduced ecosystems, they likely put at least some pressure on local invertebrate populations, whether as predators or competitors for prey species. This may become more pronounced as continued overuse of pesticides and habitat loss contribute to the invertebrate apocalypse.

Honey Bee (Apis mellifera)

“Save the bees!” has been an increasingly common headline since Colony Collapse Disorder first became widely known among the general public almost twenty years ago. What the articles rarely mention is that the honey bee is actually a domesticated insect that originated from wild stock in Europe. In fact, the true wild honey bee may be close to extinction, another victim of its domesticated descendants.

In fact, honey bees cause the decline of wild bee species wherever they are introduced. Not only do they compete with wild bees for food and nest sites, but they also spread diseases and parasites to these other species, some of which have become quite scarce. Moreover, honey bees are less effective at pollinating native plants outside their own range, and these species are at risk of extinction if their native pollinators are out-competed.

Another invertebrate beloved of gardeners here, the earthworms actually consist of a mix of both native and non-native species. Unfortunately, many native earthworms went extinct during the last Ice Age, so if your area has a recent glacial history it’s likely that the worms in your garden are invasive. (That does include the red wigglers (Eisenia fetida) commonly used for vermicomposting.)

What damage can a bunch of worms do? Plenty, as it turns out. They speed up decay and mix up nutrients in the soil in ways that many North American ecosystems aren’t used to. This changes physical characteristics of the soil like pH, texture, and density, as well as distribution of nutrients. Some young plants may not be able to reach nutrients that worms have moved deeper underground. So while you may thank earthworms for aerating the soil in your garden, they’re more of a problem for a lot of native ecosystems here.

umbleweed (various species)

“Drifting along with the tumbling tumbleweeds,” sang the Sons of the Pioneers in 1934, though tumbleweeds have been associated with the American West for much longer. Several species of plant dry out, snap off the root system, and roll along the ground spreading the mature seeds. The best-known species is the Eurasian Kali tragus, though there are other species that have been introduced here.

Because these plants take up a lot of physical space, they can crowd out native plants, especially those that are not shade-tolerant. Their seed distribution method means that one plant can spread its descendants many miles from where it originated. Moreover, the masses of dead, dry tumbleweeds can build up and become wildfire fuel.

Red Clover (Trifolium pratense) and White Clover (Trifolium repens)

These two plants are so ubiquitous that it’s easy to assume they’ve always been here. White clover is especially common in lawns, and red clover will pop up in just about any disturbed sunny spot. Both are native to Europe and Asia, and red clover additionally may be found in North Africa. However, both species have been widely introduced elsewhere.

While neither is considered particularly invasive, they can take over large areas of disturbed land. They are deliberately sown for cover crops and livestock forage, so they’re not likely to go away any time soon.

Stinging Nettle (Urtica dioica)

This is one of the most popular spring plants for foragers; chemicals that cause irritation can be removed through soaking the plants in water or cooking them. Although stinging nettle grows well in large areas of the United States, Mexico, and southern and western Canada, it is actually native to northern Africa, Europe, and Asia.

Stinging nettle makes itself at home in forested settings in particular. While it doesn’t create the same sorts of monocultures that, say, Himalayan blackberry does, it can shade out smaller plants with its broad leaves.

Saffron Milkcap (Lactarius deliciosus)

People don’t often think of fungi when it comes to non-native and invasive species, and yet there are fungi that have been moved around to new areas, often with their partner plants. Some are tiny soil fungi, but there are those that produce visible fruiting bodies. The edible saffron milkcap is one of these. It is mycorrhizal with pine trees in its native Europe, and managed to form connections with pines in North America as well.

As saffron milkcap does not cause any known diseases of plants, it is not considered an invasive species in the way that chestnut blight (Cryphonectria parasitica) is. While the mycelium of saffron milkcap may certainly compete for some of the same soil nutrients as native species in the same area, it has not become aggressive enough to displace native fungi.

Death Cap (Amanita phalloides)

There are large, white Amanita species native to North America, like A. ocreata and A. bisporigera, both known colloquially as “destroying angels.” The death cap, however, is native to Europe. It has been spreading through parts of the United States, particularly along all the coastlines, and may sometimes be yellow-tinted. Its close cousin, the European destroying angel (A. virosa), has made a few appearances in New England and southern Quebec according to iNaturalist’s map of research-grade observations.

While these invasive Amanitas do not cause widespread ecological damage, they are considered invasive due to their extreme lethality. One cap is sufficient to kill a healthy adult human being.

Did you enjoy this post? Consider taking one of my online foraging and natural history classes or hiring me for a guided nature tour, checking out my other articles, or picking up a paperback or ebook I’ve written! You can even buy me a coffee here!

#CW spider#spider#animals#plants#fungi#wildlife#nature#invasive species#native species#biodiversity#ecology#conservation#environment#gardening#weeds#foraging#mushroom hunting

55 notes

·

View notes