#managerialism

Text

"By 1924, progressive prison reformers were openly lamenting the atrophy of public interest in the cause of humanitarian prison reform; two years later, many noted that this inattentiveness had turned to outright hostility toward a number of the foundational principles of progressive penology. That year, under the leadership of Republican Crime Commissioner, state Senator Caleb Baumes, the Republican-dominated New York state legislature breathlessly enacted twenty two crime bills that, together, had far-reaching implications for offenders and life in the state’s prisons. Popularly known as the "Baumes laws," the new legislation created new crimes, retrenched procedural protections for the accused, abolished the good-time system under which good behavior in prison reduced a convict’s sentence, reintroduced mandatory sentencing, and drastically raised maximum sentences for a number of serious crimes. (For example, the maximum sentence for first-degree robbery was raised from twenty years to life imprisonment and, for second-degree robbery, from ten to fifteen years). Most infamously, the Baumes laws strengthened the state’s 1907 habitual criminal law by providing that any person convicted of a fourth felony "shall be sentenced to life imprisonment without possibility of parole or commutation of sentence."

The passage of these laws had little, if any, appreciable impact upon New York’s supposed crime wave (although, according to an outraged Clarence Darrow, they contributed significantly to a national "hate wave" and constituted an egregious assault upon civil liberties). The laws did, however, play a catalytic and, in many ways, deeply ironic role in the history of legal punishment. In effectively abolishing indeterminate sentences and providing that upon a fourth conviction for felony crime a convict would automatically receive a life sentence without possibility of parole or commutation, the Baumes laws threw a large spanner into the disciplinary machinery of the prisons. As noted earlier, the logic of the new disciplinary system held that prisoners would render up obedience in exchange for earlier freedom and, in the meantime, the pleasures and releases afforded by movies, athletics, tobacco, and various other sublimating activities. The Baumes laws, however, challenged three of the principal presuppositions of this penology: namely, that all but a small minority of convicts would eventually leave prison; that no hardened core of embittered, hopeless "lifers" would accumulate in the prison; and that every prisoner, in theory at least, enjoyed the possibility of early discharge through good behavior. These were important structural preconditions for penal managerialism’s system of incentive; without them, convicts had much less reason to cooperate with the administration and far more incentive to rebel.

As well as tinkering with the incentive system of managerial penology, the Baumes laws breached a principle of justice dear to the hearts of prisoners: equality of sentencing (wherein the same crime got the same time, regardless of the convict’s record). As Warden Lawes understood very well, equality of sentencing, and more especially prisoners’ perception that the criminal justice system treated convicts more or less equally, was essential to the task of maintaining the good morale of the prisoners – and, hence, the good order of the prison. The "four strikes” law engendered the situation by which a person convicted of four burglaries would be automatically incarcerated for life without possibility of parole or commutation, whereas a person with a conviction for manslaughter (or even two previous convictions for manslaughter) would more likely serve a sentence of twenty years. This assault upon equality of sentencing prompted Lawes to complain to a reporter from the New York Times that the Baumes laws quite perversely provided robbers an incentive to kill their victims and plead guilty to what was now the lesser charge of manslaughter. The third problem posed by the Baumes laws was that their provision for longer sentences and mandatory lifetime sentences for fourth-timers threatened to trigger a rapid increase of the prison populations in prisons that were already putting two, and sometimes three, men in cells measuring just six feet by five feet. The Baumes’ laws seemed very likely to overfill the prisons; moreover, the surplus of prisoners would consist not in the usual run of convicts, but in an aggrieved and hopeless class of convicts who considered themselves profoundly wronged by the law.

Once the Baumes laws went into effect in July 1926, prison populations began to grow quite steeply and prison conditions began to degenerate. The initial source of the increase was not a rapid upswing in new commitments, but rather a decrease in the release rate, and people entering with longer sentences to serve: Fewer people were committed to New York’s state prisons and reformatories in 1927 than in 1926, but New York’s state prison population nonetheless increased quite steadily in the following years, as the first to be sentenced to life under the four strikes law began to trickle into the system. Every year after 1927, commitments to the state prisons increased dramatically. In 1928 and 1929, the population of the four main state prisons increased over eleven percent, or just over five percent per annum. Cellblocks that already held a full complement of prisoners overflowed: By 1929, New York’s male state prison population exceeded cell capacity by almost 1,000 men – or twenty percent – of the prisons’ capacity. Although, in and of itself, the increase in the sheer number of prisoners exerted considerable pressure on the prison order, the particular source of the surplus population was even more significant. Just as Lawes had warned, the prisons began accumulating miserable and volatile lifetime prisoners, and a larger mass of prisoners serving longer sentences for lesser crimes. At Sing Sing an influx of Baumes "lifers" increased the total number of prisoners serving life terms by sixty-five percent in just sixteen months. These were precisely the prisoners whom Lawes warned would have no hope for the future and who, in their mounting desperation, were likely to resist, escape, or even attempt to overthrow prison authorities.

Prisoners at Auburn and Clinton, the prisons to which the majority of repeat and lifetime convicts were committed, became increasingly restive in these years. Audacious escape attempts multiplied: A train-load of men being transferred out of overcrowded Sing Sing to Clinton in late 1927 attempted a mass break in transit (the attempt was foiled). The same year, Clinton authorities intercepted a cache of weapons, ammunition, and maps intended for a group of prisoners, and learned of plans for a large-scale prison break. In another spectacular, if equally unsuccessful, escape attempt, three convicted felons held in Manhattan’s "Tombs" jail used smuggled pistols to shoot their way to freedom; along the way, the warden and head keeper were shot dead, and two of the prisoners turned their weapons on themselves rather than face trial under the new laws. The rate of smaller scale escape attempts also inclined – both at the state prisons and at police jails, where accused offenders awaited trial under the new sentencing laws or transfer to a state prison.

Under the strain, the critical mechanisms of managerial prison discipline – sublimation and the activation of a convict’s desire to be free – threatened to jam. The respective state prison wardens took immediate steps to head off trouble: All scaled-up security and most rolled back privileges. In the midst of the statewide spate of escape attempts, the warden of Great Meadow abolished the honor league and put the convicts to work building a high wall around that previously low-security prison. At Auburn, warden Edgar S. Jennings abandoned the basic managerial approach and began to crack down on various prisoner-organized activities. Anxious to assert his authority, Jennings moved, in 1927, to cancel the established celebrations surrounding various national and ethnic holidays in the prison. Failing to recognize that such affairs could be restructured in such a way as to stabilize rather than undermine the prison order, Jennings insisted they were inherently disruptive, unruly events: "The Irish-Americans wish to celebrate St. Patrick’s Day; the colored men, Emancipation Day; the Italians, Columbus Day; the Polish, a Polish Day; and the Hebrews, a special feast day," he exclaimed in an exasperated memo to the Superintendent of Prisons in 1927. "The rivalry between those few different groups to have a more successful performance, bigger acts, and more entertainment has developed a condition that is very unsatisfactory," he went on: The celebrations had to be curtailed. The warden proceeded to abolish half-holidays, lock-down the prisoners in their cells on Saturday nights, cancel special suppers, reinstate the punishment cells, and suspend various privileges. As warden Jennings cracked down, prisoners began defying orders, the warden punished alleged troublemakers with ever longer periods of isolation in the punishment cells, and the keepers turned against both the league and a warden who seemed incapable of reining in the prisoners. Clinton’s warden rolled back privileges and segregated suspected troublemakers in the punishment cells.

At Sing Sing, Lewis E. Lawes took a different tack. Like his colleagues up-state, he quietly tightened security at the prison (chiefly, by suspending visiting, reinforcing the prison wall, and mounting machineguns on the watchtowers). But, at the same time, he stepped up his program of morale-building. Lawes redoubled his efforts to demonstrate his responsiveness to the prisoners and their needs. As well as maintaining established programs, he gave the entire prison a special chicken dinner, motion pictures, and live music on Thanksgiving; likewise, on Christmas day, he and his wife provided the men with movies, a special meal, and small "favors" and gifts. At the request of one "lifer" he ordered the stars and stripes hoisted within sight of the cellblock, in honor of the 300-odd Great War veterans who resided there. He also extended the new psychiatric program at the prison, describing the program as a great asset to prison administration. Finally, he made a number of public statements in which he made it clear, not only to the general public but to the prisoners, that he was unequivocally opposed to the Baumes laws and that he felt considerable empathy for the convicts. All men, including prisoners, had their breaking point, Lawes declared in a 1928 radio address on Collier’s hour (which was broadcasted live to the men of Sing Sing): All were subject to temptation.

The deteriorating situation in the prisons came to a head in the summer of 1929. At Clinton prison, on July 22, 1929 (almost exactly three years after the Baumes laws had gone into effect), 1,300 prisoners attempted to storm the walls and burn down the buildings. Before a hastily convened force of keepers and volunteers restored order, three prisoners were shot dead and dozens more, peppered with buckshot. Governor Franklin D. Roosevelt indicated, following the Clinton rebellion, that no executive action was needed. However, within days of the Clinton rebellion, the escalating power tussles at Auburn erupted into open conflict. A full-scale uprising broke out. Auburn prisoners rioted for several days, razing the wood and furniture shops, foundry, dye house, store house, and commissary and seriously damaging five other prison buildings. Order was restored only after the National Guard was called out. Realizing that these riots were probably not isolated incidents, after all, Roosevelt called for an immediate and wide-ranging investigation of the prisons, and for a review of the Baumes laws (which he strongly inferred were responsible for the recent unrest in the prisons).

Using a technique he would later put to use as President of the United States, Roosevelt convened a series of “parleys” at his Manhattan residence, calling together a wide array of experts, including prison wardens, members of the National Committee on Prisons & Prison Labor, and criminologists, to discuss the prison situation. As the investigation got underway in earnest, Auburn prisoners acted a second time to register their frustration and anger at the Baumes laws. In December 1929, a handful of Auburn prisoners rebelled once again, this time taking warden Jennings hostage and calling for the release of their comrades from the punishment cells. When the authorities refused to cooperate, the prisoners put that marvelous technology of penal managerialism – the radio system – to work, broadcasting a general call to riot, and successfully precipitating a second, full-fledged prison uprising. The National Guard was called out once more. By the time order was restored, the principal keeper and eight convicts were dead, four guards and two convicts were seriously wounded, and dozens of convicts and guards had been gassed. (Warden Jennings survived).

...

Notably, convicts at the most infamous of American prisons – Sing Sing – did not riot. Although it was the case that Sing Sing had not borne the full brunt of the four strikes laws (largely because it received mostly shorter-term first and second-time offenders) it was, nonetheless, more overcrowded than at any other point in its history, and it did have a small, but rapidly growing, population of Baumes "lifers." Like his colleagues, Lawes had tightened security as unrest among the prisoners had mounted after 1926. But, unlike the others, Lawes had extended and reinforced the morale-building disciplinary system and sought, at every turn, to shore up the "square deal" between prisoners and keepers.

Upon hearing rumors that Sing Sing prisoners might follow Auburn’s example and riot, Lawes deftly deployed a combination of force and empathy to maintain control of Sing Sing. He immediately talked with the Sing Sing convicts and solicited their grievances. While consulting with his wards, he also made it clear that any collective action or protest on the convicts’ part would be met with swift and certain repression. An overwhelming show of force punctuated this threat: Within hours of the December uprising at Auburn, three companies of the National Guard went on alert at Sing Sing, a small U.S. naval vessel sailed up the Hudson from New York City, and three more Gattling machine guns appeared on the high wall of the prison. As convicts witnessed this show of force, Lawes quietly suspended the Mutual Welfare League’s annual Christmas show on the grounds that a large gathering of convicts might be volatile. As Lawes later told the story, when the league’s leaders voted to resign in protest and rumors began circulating to the effect that a riot was imminent, he accepted their resignations and then promptly informed the prison population that the former organizers had resigned and were on their way to Clinton prison. But even at this point, Lawes did not abolish the league or institute a prisonwide crack-down, as Jennings had done at Auburn. Rather, he worked with the league’s new leaders (who quietly "agreed" with Lawes that the show, indeed, ought to be cancelled, after all) to calm the prison. Rumors of imminent riot subsided. Some sixteen years after the scandalous rebellion of 1913, and as prisons around the state and in other parts of the country erupted in protest, Lawes had enforced the good order of Sing Sing. Even more critically, he had been seen to have done so.

Rather than undermining the penal managerial model of imprisonment, the riots of 1929 indirectly facilitated its consolidation and extension throughout New York’s state prison system. That the Baumes laws had very likely precipitated the Auburn and Clinton prison riots was not lost on Governor Franklin D. Roosevelt; nor did Roosevelt fail to notice Sing Sing’s relative calm and Lawes’s apparently adept handling of the unrest there. In a confidential memorandum to Lawes, Roosevelt sought his advice and, in particular, his views on the Baumes laws’ impact on prison order. A series of official investigations further called into question both the efficacy and the justice of the Baumes laws and cast a very positive light on Lawes and his well-worked-up model of prison administration.

Following the December riot at Auburn, a hastily convened commission headed by Colonel George F. Chandler (former Superintendent of the New York State Police) scrutinized not only the actions of prisoners, but prison conditions and the conduct of the warden, guards, police, and troopers. In his report, Chandler condemned Auburn as an overcrowded prison full of ill-disciplined, underfed convicts and declared that a small group of "desperate" longterm convicts (of the sort generated by the Baumes laws) had taken over the Mutual Welfare League (MWL) and were more or less running the prison. His objection, critically, was not that the convicts were attending entertainments but that the warden had suffered the MWL to become a thuggish gang under the tutelage of the long-term men. (Chandler wrote: "These League officers have police powers, administer punishments, order privilege taken away or granted, run entertainment once or twice a year for which they collect money from the general public who attend, and run a baseball club where male outsiders may attend." Moreover, the convicts ran the telephone switchboard, assisted in mail handling and the cleaning of the offices, guard rooms, and hallways, which, Chandler objected, compromised security.) He concluded by recommending that the overcrowding of the prison be relieved and the Auburn MWL, abolished.

In a separate investigation, Joseph M. Proskauer, an associate justice of the Supreme Court of New York, affirmed these findings but was far more explicit in placing the blame for the riots squarely on the shoulders of the Baumes laws. Proskauer urgently recommended that Governor Roosevelt undertake "fundamental and drastic reform" of the state’s penal system. The Superintendent of Prisons, Raymond Kieb, also criticized the Baumes laws, and recommended the restoration of compensation time. He publicly declared: "(i)t was the strongest instrument the office had for the preservation of law and order in the prisons, as each [convict] knew that behavioristic [sic] deviation led to time forfeiture and delayed the date the prisoners might be granted the privilege of again being free." Finally, the National Society of Penal Information (whose membership was composed of veteran progressive reformers) issued a report laying the blame for the first two New York rebellions on the new sentencing laws, the curtailment of the good-conduct system of early release, and the retrenchment of parole.

In 1930, Roosevelt proceeded to act on these recommendations. He and the Superintendent of Prisons consulted with the wardens about how best to rebuild discipline at Auburn and in the system more generally: Warden Lawes’s Sing Sing was to serve as the basic model of reform. Notably, prison industries – which, just a few years earlier, had been the object of intensive discussion – were given very little emphasis. In announcing the appointment of two prison planning committees (one on the "segregation" of various classes of prisoners and one on prison industries), Roosevelt indicated that putting prisoners to productive labor would most likely not be part of the solution: Noting that "an idle prisoner becomes a brooder and only too often eventually a plotter" he suggested that "trade schools rather than ... factories" might be established in the prisons. Instead, New York’s prison reforms concentrated on segregating various classes of prisoners, repealing the Baumes sentencing laws, and, slowly but surely, applying the principles of Lawes’ managerial penology across the entire state prison system. Roosevelt announced a $30 million program for the improvement of prison conditions, athletics and exercise programs, education, manual training, and the systematic segregation of various classes of prisoners. Notably, when Roosevelt discussed the program he remained silent on the topic of prison industries.

Over the next few years, the principles of the sublimation of prisoners’ emotions through a variety of mostly nonlaboring activities, the privilege system, and the occasional show of uncompromising force, were generalized to the entire state prison system. Although, at Auburn, the MWL was abolished (as per Roosevelt’s request), the recreational and educational activities its members had organized were eventually reinstituted under the auspices of the state, much as Chandler had recommended. On Lawes’s insistence that good food was an important "aide to morale," the quality of prison rations was improved all round. Psychiatrists were hired for each prison and proceeded to play an important role in the assessment of those convicts thought to pose a risk to the prison’s security. Sing Sing psychiatrist, Bernard Glueck’s, taxonomy of mental health was adapted to these ends; in all the prisons, the psychiatrists’ primary task was that of adapting petulant, troublesome, or depressed convicts to prison discipline and identifying for segregation (or exile to Clinton) those deemed to be security threats. Penal managerialism’s need for guards who would resort to psychological, rather than corporeal, means of managing prisoners, was implicitly recognized in the planning and execution of the state’s first guard training programs and the New York State Training School for Guards at Wallkill prison (opened in 1936). Finally, in 1931, at the recommendation of the State Commission of Correction, and with the vocal support of Lawes and Roosevelt, the New York legislature repealed several of the Baumes laws: Most critically, lawmakers reinstituted one of the cornerstones of managerial penology – the good-time compensation plan, under which good behavior was to be rewarded by early release. A year later, Roosevelt signed into law a bill that repealed the mandatory life sentence that another Baumes law imposed on fourth-time offenders: Persons convicted of a fourth felony were now subject to a minimum sentence of fifteen years in prison rather than the mandatory sentence of life.

As part of this general overhaul of the state prison system, Roosevelt also established a State Commission on Prison Administration and Construction, charging it with the task of planning and building six new prisons. The state’s second great wave of prison building soon followed, and in four years, five new state prisons were opened (Attica, Bedford Hills, Coxsackie, Wallkill, and Woodburne). All were to be administered according to much the same managerial principles prescribed for the other prisons of the state. Critically, prison labor was not to be used in the construction of these new facilities: William Green, the President of the AFL, successfully lobbied New York state, and the federal government, to restrict the use of penal labor in public works on the grounds that convicts were provided with "food, clothing, and shelter" while, as the Great Depression wore on, free labor was going without. Prisons were "public works" and as such, it was agreed that free labor, rather than convict labor, should build them."

- Rebecca M. McLennan, The Crisis of Imprisonment: Protest, Politics, and the Making of the American Penal State, 1776-1941. Cambridge University Press, 2008. McCormick, p. 450-459

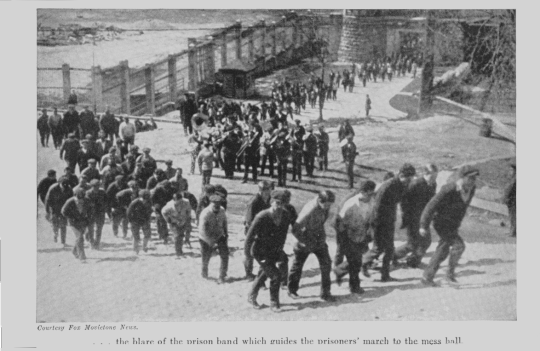

The photo shows prisoners at Sing Sing marching to the mess hall, from Lewis E. Lawes, Twenty Thousand Years in Sing Sing. New York: A. L. Burt Company, 1932, p. 178.

#sing sing prison#penal reform#penal modernism#managerialism#prison riot#causes of prison riots#crisis of imprisonment#new york prisons#classification and segregation#tough on crime#baumes laws#history of crime and punishment#academic quote#reading 2023#lifers#severe sentencing#lewis lawes#prison construction#auburn prison#clinton prison#new york history#prisoner resistance#convict revolt

0 notes

Text

"Democracy” has long since been redefined to mean the uninterrupted rule of the managerial elite and the undiluted supremacy of their ideological values.

0 notes

Photo

i know larry sleeps in those ebenezer-scrooge ass pajamas.

#pokemon#pokemon sv#pokemon sv spoilers#pokemon scarlet#pokemon violet#pokemon scarlet and violet#pokemon larry#larry pokemon#geeta pokemon#pokemon geeta#pokemon sv geeta#pokemon sv larry#larry#geeta#casual managerial abuse by geeta#Lo#i wont tag something unruly about larry but i could#i want him#id take him in his silly pajamas.#pokemon scarlet violet#1k#5k#10k

16K notes

·

View notes

Photo

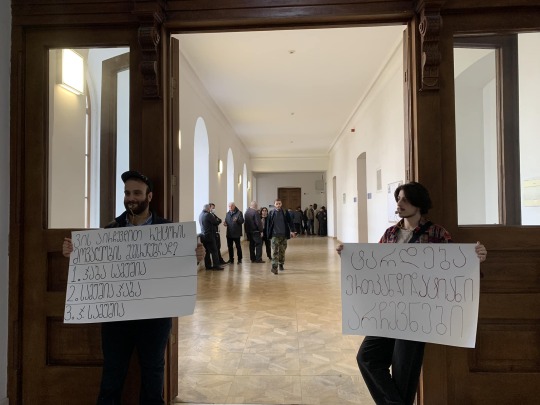

მუხლი 11. წარმომადგენლობითი საბჭოს (სენატის) უფლებამოსილება

1. წარმომადგენლობითი საბჭო კანონმდებლობის მოთხოვნების შესაბამისად, ამ წესდებით განსაზღვრული მიზნების განსახორციელებლად:

ა) შეიმუშავებს და აკადემიური საბჭოს მონაწილეობით განიხილავს უნივერსიტეტის წესდების, წესდების ცვლილებების პროექტს და დასამტკიცებლად წარუდგენს საქართველოს განათლების, მეცნიერების, კულტურისა და სპორტის სამინისტროს;

ეს არის ამონარიდი თბილისის სახელმწიფო უნივერსიტეტის წესდებიდან, რომლის მიმდინარე ვერსია ჩვენთვის, საზოგადოებისთვის, მხოლოდ ერთი თვის წინ გახდა ხელმისაწვდომი, ვინაიდან, უნივერსიტეტის ვებგვერდზე განთავსებული იყო წესდების ძველი ვერსიები. გარდა ამისა, როდესაც მაისის სტუდენტური მოძრაობა უნივერსიტეტში სხვადასხვა შეხვედრების დროს აჟღერებდა მოთხოვნას რექტორის არჩევის წესის ცვლილების შესახებ, უნივერსიტეტის, რექტორის და ადმინისტრაციის პასუხი იყო შემდეგი, რომ უნივერსიტეტს არ ჰქონდა ბერკეტი ამგვარი ცვლილების განსახორციელებლად. აქედან გამომდინარე, მაისის სტუდენტური მოძრაობის და უნივერსიტეტის წარმომადგენლების შეხვედრის შედეგად, ამ მიმართულებით არ შექმნილა სამუშაო კომისია.

მოულოდნელი არ არის, რომ ისინი თავს იკავებენ სტუდენტებთან დიალოგისგან ისეთ სისტემურ ცვლილებებთან დაკავშირებით, როგორიც არის რექტორის არჩევის წესის ცვლილება და მასთან ლოგიკურად დაკავშირებული სხვა მმართველობითი სტრუქტურების რეორგანიზაცია. პირიქით, ჩვენ ვხედავთ, რომ სახელმწიფო და უნივერსიტეტი მეტ-ნაკლებ მზადყოფნას აცხადებენ სტუდენტურ საერთო საცხოვრებელთან დაკავშირებით, თუმცა, არც კი განიხილავენ სისტემურ ცვლილებებს. არსებული სისტემა, მათ შორის რექტორის არჩევის წესი, აკადემიური საბჭოს უფლებამოსილებები, აკადემიური საბჭოს ფორმირების პრაქტიკა და სხვა, წარმოადგენს ანტისოციალურ და ანტიაკადემიურ მიკროკლიმატს, კომფორტის ზონას ნებისმიერი არაჯანსაღი ელემენტისთვის. ისინი საუბრობენ რექტორის პირდაპირ გზით არჩევის წესის რისკებზე, თუმცა, რეალობა განსხვავებულია.

თვალს თუ გადავავლებთ სამეცნიერო ლიტერატურას რექტორის მენეჯერული მოდელის და მისი შედეგების შესახებ, აღმოვაჩენთ, რომ გაერთიანებულ სამეფოში, კონტინენტური ევროპის და ლათინური ამერიკის იმ ქვეყნებში, სადაც ბოლო ოცი წლის განმავლობაში განხორციელდა უმაღლესი განათლების რეფორმა და რექტორის არჩევის ტრადიციული წესი შეიცვალა მენეჯერული მოდელით, აკადემიური აზრი თითქმის სრულად კრიტიკულია. რაც შეეხება, რექტორის მენეჯერული მოდელის მომხრეთა პოზიციებს, ისინი ძირითადად გვხვდება რუსული წარმომავლობის აკადემიურ წყაროებში, რომლებიც ცალსახად ნეოლიბერალური ხასიათისაა. ავტორები საუბრობენ, თუ რამდენად დადებითად აისახა მენეჯერული მოდელი რუსეთის უმაღლეს საგანმანათლებლო-კვლევით დაწესებულებებში.

ვინაიდან, ვიცით, რომ რექტორის არჩევის წესის ცვლილება გრძელვადიანი პროცესია, გარდა ამისა, ხდება მისი ხელოვნურად გაჭიანურებაც, ხოლო ამ თვის 26-ში თბილისის სახელმწიფო უნივერსიტეტში ტარდება რექტორის არჩევნები, არსებული წესის ფარგლებში, სანამ შეიცვლება არჩევის წესი, ჩვენ უნივერსიტეტს ვთავაზობთ შემდეგს:

მნიშვნელოვანი გადაწყვეტილებების მიღების, მათ შორის, რექტორის არჩევის პროცესში, აკადემიური საბჭოს წარმომადგენლები, რექტორის არჩევნებში ხმას აძლევენ არა მათთვის სასურველ კანდიდტს, არამედ საფაკულტეტო მასშტაბით, პროფესორების მიერ პირდაპირი ფარული კენჭისყრის გზით არჩეულ კანდიდატს.

სტუდენტები მოვითხოვთ, რომ კანდიდატთა შერჩევის პროცესში, აკადემიურმა საბჭომ კანდიდატთა სამოქმედო გეგმები განიხილოს საჯაროდ, სტუდენტებთან ერთად და შესაბამისად მიიღოს გადაწყვეტილება!

ჩვენს მიერ შეთავაზებული ალტერნატივები ემსახურება არსებულ ჩაკეტილ პირობებში სიტუაციის შეძლებისდაგვარად გამოსწორებას და, რა თქმა უნდა, უკავშირდება ჩვენს საბოლოო განუხრელ მიზანს:

შეიცვალოს რექტორის არჩევის წესი! შეიცვალოს სისტემური საფუძვლები, რომლებიც აღრმავებენ სხვადასხვა სტუდენტურ სოციალურ და ეკონომიკურ პრობლემებს!

ტექსტში გამოყენებული აკადემიური წყაროები:

1. Gornitzka, Å., Maassen, P., & De Boer, H. (2017). Change in university governance structures in continental Europe. Higher Education Quarterly, 71(3), 274-289.

2. Ziegele, F., & Kunkel, F. The Election of University Rectors in Germany: New Processes to Support Strategic Leadership. IEB’s Report on Fiscal Federalism and Public Finance 4 Informe IEB sobre Federalismo Fiscal y Finanzas Públicas 70 Informe IEB sobre Federalisme, 30.

3. Goedegebuure, L. C. (1994). Mergers in higher education: A comparative perspective.

4. Amaral, A., Meek, V. L., Larsen, I. M., Larsen, I. M., & Lars, W. (Eds.). (2003). The higher education managerial revolution? (Vol. 3). Springer Science & Business Media.

Dyachenko, E., & Mironenko, A. (2019). Academic Leadership Through the Prism of Managerialism: The Relationship Between University Development and Rector's Specialization.

Voprosy obrazovaniya/Educational Studies Moscow

, (1), 137-161.

#მაისისსტუდენტურიმოძრაობა#რექტორისარჩევისწესი#თსუ#მენეჯერიალიზმი#უმაღლესიგანათლება#maystudentmovement#tsu#rectorelections#managerialism#highereducation#georgia#tbilisi

0 notes

Quote

As large corporations came to dominate the economic landscape after the first part of the twentieth century, the control and management of business enterprises also changed in a fundamental way. In the factory economy, corporations were largely instruments of their entrepreneurial owners. Such men as Carnegie, Harriman, Ford, Eastman, DuPont, and, of course, Rockefeller were known as corporate titans. Yet as corporations grew and became ever more complex, with a vastly increased need for management and administration, they became controlled by a class of professional managers. Scholars argued that control was now separate from ownership. Adolph Berle of Columbia University, a leading member of Franklin Roosevelt's "Brains Trust," went so far as to conclude that the large corporation gave no rights to the owners of the enterprise, so it was up to a class of enlightened managers to guide the corporation. It wasn't just New Dealers who held this view; Republican Senator Robert Taft, known as Mr. Conservative for his rock-ribbed midwestern conservatism, stated, 'The social consciousness of great corporations is promoted by the glare of publicity in which they must operate, and by a management attitude now approaching that of trusteeship, not only for the stockholders, but for employees, customers, and the general public.

Robert D. Atkinson and Michael Lind, “Big is Beautiful: Debunking the Myth of Small Business” (2018).

#Economics#Economic Development#Heterodox Economics#National Economics#Economic Nationalism#Innovation Economics#Managerialism

1 note

·

View note

Photo

(link)

0 notes

Text

Amazon’s financial shell game let it create an “impossible” monopoly

I'm on tour with my new, nationally bestselling novel The Bezzle! Catch me in TUCSON (Mar 9-10), then San Francisco (Mar 13), Anaheim, and more!

For the pro-monopoly crowd that absolutely dominated antitrust law from the Carter administration until 2020, Amazon presents a genuinely puzzling paradox: the company's monopoly power was never supposed to emerge, and if it did, it should have crumbled immediately.

Pro-monopoly economists embody Ely Devons's famous aphorism that "If economists wished to study the horse, they wouldn’t go and look at horses. They’d sit in their studies and say to themselves, ‘What would I do if I were a horse?’":

https://pluralistic.net/2022/10/27/economism/#what-would-i-do-if-i-were-a-horse

Rather than using the way the world actually works as their starting point for how to think about it, they build elaborate models out of abstract principles like "rational actors." The resulting mathematical models are so abstractly elegant that it's easy to forget that they're just imaginative exercises, disconnected from reality:

https://pluralistic.net/2023/04/03/all-models-are-wrong/#some-are-useful

These models predicted that it would be impossible for Amazon to attain monopoly power. Even if they became a monopoly – in the sense of dominating sales of various kinds of goods – the company still wouldn't get monopoly power.

For example, if Amazon tried to take over a category by selling goods below cost ("predatory pricing"), then rivals could just wait until the company got tired of losing money and put prices back up, and then those rivals could go back to competing. And if Amazon tried to keep the loss-leader going indefinitely by "cross-subsidizing" the losses with high-margin profits from some other part of its business, rivals could sell those high margin goods at a lower margin, which would lure away Amazon customers and cut the supply lines for the price war it was fighting with its discounted products.

That's what the model predicted, but it's not what happened in the real world. In the real world, Amazon was able use its access to the capital markets to embark on scorched-earth predatory pricing campaigns. When diapers.com refused to sell out to Amazon, the company casually committed $100m to selling diapers below cost. Diapers.com went bust, Amazon bought it for pennies on the dollar and shut it down:

https://www.theverge.com/2019/5/13/18563379/amazon-predatory-pricing-antitrust-law

Investors got the message: don't compete with Amazon. They can remain predatory longer than you can remain solvent.

Now, not everyone shared the antitrust establishment's confidence that Amazon couldn't create a durable monopoly with market power. In 2017, Lina Khan – then a third year law student – published "Amazon's Antitrust Paradox," a landmark paper arguing that Amazon had all the tools it needed to amass monopoly power:

https://www.yalelawjournal.org/note/amazons-antitrust-paradox

Today, Khan is chair of the FTC, and has brought a case against Amazon that builds on some of the theories from that paper. One outcome of that suit is an unprecedented look at Amazon's internal operations. But, as the Institute for Local Self-Reliance's Stacy Mitchell describes in a piece for The Atlantic, key pieces of information have been totally redacted in the court exhibits:

https://www.theatlantic.com/ideas/archive/2024/02/amazon-profits-antitrust-ftc/677580/

The most important missing datum: how much money Amazon makes from each of its lines of business. Amazon's own story is that it basically breaks even on its retail operation, and keeps the whole business afloat with profits from its AWS cloud computing division. This is an important narrative, because if it's true, then Amazon can't be forcing up retail prices, which is the crux of the FTC's case against the company.

Here's what we know for sure about Amazon's retail business. First: merchants can't live without Amazon. The majority of US households have Prime, and 90% of Prime households start their ecommerce searches on Amazon; if they find what they're looking for, they buy it and stop. Thus, merchants who don't sell on Amazon just don't sell. This is called "monopsony power" and it's a lot easier to maintain than monopoly power. For most manufacturers, a 10% overnight drop in sales is a catastrophe, so a retailer that commands even a 10% market-share can extract huge concessions from its suppliers. Amazon's share of most categories of goods is a lot higher than 10%!

What kind of monopsony power does Amazon wield? Well, for one thing, it is able to levy a huge tax on its sellers. Add up all the junk-fees Amazon charges its platform sellers and it comes out to 45-51%:

https://pluralistic.net/2023/04/25/greedflation/#commissar-bezos

Competitive businesses just don't have 45% margins! No one can afford to kick that much back to Amazon. What is a merchant to do? Sell on Amazon and you lose money on every sale. Don't sell on Amazon and you don't get any business.

The only answer: raise prices on Amazon. After all, Prime customers – the majority of Amazon's retail business – don't shop for competitive prices. If Amazon wants a 45% vig, you can raise your Amazon prices by a third and just about break even.

But Amazon is wise to that: they have a "most favored nation" rule that punishes suppliers who sell goods more cheaply in rival stores, or even on their own site. The punishments vary, from banishing your products to page ten million of search-results to simply kicking you off the platform. With publishers, Amazon reserves the right to lower the prices they set when listing their books, to match the lowest price on the web, and paying publishers less for each sale.

That means that suppliers who sell on Amazon (which is anyone who wants to stay in business) have to dramatically hike their prices on Amazon, and when they do, they also have to hike their prices everywhere else (no wonder Prime customers don't bother to search elsewhere for a better deal!).

Now, Amazon says this is all wrong. That 45-51% vig they claim from business customers is barely enough to break even. The company's profits – they insist – come from selling AWS cloud service. The retail operation is just a public service they provide to us with cross-subsidy from those fat AWS margins.

This is a hell of a claim. Last year, Amazon raked in $130 billion in seller fees. In other words: they booked more revenue from junk fees than Bank of America made through its whole operation. Amazon's junk fees add up to more than all of Meta's revenues:

https://s2.q4cdn.com/299287126/files/doc_financials/2023/q4/AMZN-Q4-2023-Earnings-Release.pdf

Amazon claims that none of this is profit – it's just covering their operating expenses. According to Amazon, its non-AWS units combined have a one percent profit margin.

Now, this is an eye-popping claim indeed. Amazon is a public company, which means that it has to make thorough quarterly and annual financial disclosures breaking down its profit and loss. You'd think that somewhere in those disclosures, we'd find some details.

You'd think so, but you'd be wrong. Amazon's disclosures do not break out profits and losses by segment. SEC rules actually require the company to make these per-segment disclosures:

https://scholarship.law.stjohns.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=3524&context=lawreview#:~:text=If%20a%20company%20has%20more,income%20taxes%20and%20extraordinary%20items.

That rule was enacted in 1966, out of concern that companies could use cross-subsidies to fund predatory pricing and other anticompetitive practices. But over the years, the SEC just…stopped enforcing the rule. Companies have "near total managerial discretion" to lump business units together and group their profits and losses in bloated, undifferentiated balance-sheet items:

https://www.ucl.ac.uk/bartlett/public-purpose/publications/2021/dec/crouching-tiger-hidden-dragons

As Mitchell points you, it's not just Amazon that flouts this rule. We don't know how much money Google makes on Youtube, or how much Apple makes from the App Store (Apple told a federal judge that this number doesn't exist). Warren Buffett – with significant interest in hundreds of companies across dozens of markets – only breaks out seven segments of profit-and-loss for Berkshire Hathaway.

Recall that there is one category of data from the FTC's antitrust case against Amazon that has been completely redacted. One guess which category that is! Yup, the profit-and-loss for its retail operation and other lines of business.

These redactions are the judge's fault, but the real fault lies with the SEC. Amazon is a public company. In exchange for access to the capital markets, it owes the public certain disclosures, which are set out in the SEC's rulebook. The SEC lets Amazon – and other gigantic companies – get away with a degree of secrecy that should disqualify it from offering stock to the public. As Mitchell says, SEC chairman Gary Gensler should adopt "new rules that more concretely define what qualifies as a segment and remove the discretion given to executives."

Amazon is the poster-child for monopoly run amok. As Yanis Varoufakis writes in Technofeudalism, Amazon has actually become a post-capitalist enterprise. Amazon doesn't make profits (money derived from selling goods); it makes rents (money charged to people who are seeking to make a profit):

https://pluralistic.net/2023/09/28/cloudalists/#cloud-capital

Profits are the defining characteristic of a capitalist economy; rents are the defining characteristic of feudalism. Amazon looks like a bazaar where thousands of merchants offer goods for sale to the public, but look harder and you discover that all those stallholders are totally controlled by Amazon. Amazon decides what goods they can sell, how much they cost, and whether a customer ever sees them. And then Amazon takes $0.45-51 out of every dollar. Amazon's "marketplace" isn't like a flea market, it's more like the interconnected shops on Disneyland's Main Street, USA: the sign over the door might say "20th Century Music Company" or "Emporium," but they're all just one store, run by one company.

And because Amazon has so much control over its sellers, it is able to exercise power over its buyers. Amazon's search results push down the best deals on the platform and promote results from more expensive, lower-quality items whose sellers have paid a fortune for an "ad" (not really an ad, but rather the top spot in search listings):

https://pluralistic.net/2023/11/29/aethelred-the-unready/#not-one-penny-for-tribute

This is "Amazon's pricing paradox." Amazon can claim that it offers low-priced, high-quality goods on the platform, but it makes $38b/year pushing those good deals way, way down in its search results. The top result for your Amazon search averages 29% more expensive than the best deal Amazon offers. Buy something from those first four spots and you'll pay a 25% premium. On average, you need to pick the seventeenth item on the search results page to get the best deal:

https://scholarship.law.bu.edu/faculty_scholarship/3645/

For 40 years, pro-monopoly economists claimed that it would be impossible for Amazon to attain monopoly power over buyers and sellers. Today, Amazon exercises that power so thoroughly that its junk-fee revenues alone exceed the total revenues of Bank of America. Amazon's story – that these fees barely stretch to covering its costs – assumes a nearly inconceivable level of credulity in its audience. Regrettably – for the human race – there is a cohort of senior, highly respected economists who possess this degree of credulity and more.

Of course, there's an easy way to settle the argument: Amazon could just comply with SEC regs and break out its P&L for its e-commerce operation. I assure you, they're not hiding this data because they think you'll be pleasantly surprised when they do and they don't want to spoil the moment.

If you'd like an essay-formatted version of this post to read or share, here's a link to it on pluralistic.net, my surveillance-free, ad-free, tracker-free blog:

https://pluralistic.net/2024/03/01/managerial-discretion/#junk-fees

Image:

Doc Searls (modified)

https://www.flickr.com/photos/docsearls/4863121221/

CC BY 2.0

https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0/

#pluralistic#amazon#ilsr#institute for local self-reliance#amazon's antitrust paradox#antitrust#trustbusting#ftc#lina khan#aws#cross-subsidization#stacy mitchell#junk fees#most favored nation#sec#securities and exchange commission#segmenting#managerial discretion#ecommerce#technofeudalism

602 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Amazing Digital Menagerie (1/3)

Jumping on the tadc au train. The idea was that the game they entered was an animal circus management game thing but instead of entering the player role, they instead entered the animal roles.

#tadc menagerie au#tadc au#the amazing digital menagerie au#menagerie Pomni#menagerie ragatha#managerie zooble#menagerie gangle#the amazing digital circus pomni#the amazing digital circus#tadc fanart#pomni#procreate#tadc#cat pomni#dog ragatha#chimera zooble#kitsune gangle#tadc pomni#tadc ragatha#tadc gangle#tadc zooble#I’ve never made an au before aaa#I’m bad at explaining my ideas#tadc but everyone’s based on animals

770 notes

·

View notes

Text

I'm becoming increasingly convinced that JLQ's clear refusal to believe DFS could even be slightly gay is the one and only reason she didn't try to skin Wuyan alive. Wuyan who, is trusted by DFS, allowed extremely close proximity, and has all the same skills DFS values in her. TBH if there was a possible love rival outside of anyone other than LXY - she should have suspected Wuyan first, before any of the 12 Pillars.

It's sad that we didn't get enough episodes to see a little more of Wuyan for anything, or JLQ for her actual Alliance duties -- but I know enough about what it takes to run operations that I can extrapolate the skill sets needed:

Skills they both have:

budgeting and currency exchange/issues

managerial acumen/ability to organize and move large groups of people

planning

communication at both upper and lower levels

resourcing

logistics

strong understanding of timing, topography, weather and how to deal with issues

stealth

esoteric knowledge for random shit they likely have to source or deal with themselves due to rarity, etc

negotiations

how to present yourself to the public

thorough and systemic thinking

planning for failure

Where JLQ fails but Wuyan succeeds:

ability to anticipate what DFS wants

ability to deliver what DFS wants in the way he wants it

ability to not sexually harass DFS

putting DFS' desires over their own (Whatever Wuyan's feelings are, we have no idea)

Where Wuyan fails but JLQ succeeds:

getting public credit for hitting their kpis

choosing to not be subservient

public leadership / getting public buy-in

It's interesting that with the both of them -- if DFS chose at any random time to just get up and leave Jinyuan Alliance behind -- both would immediately drop everything and follow him.

They're both used to seeing DFS' back - Wuyan because he deliberately positions himself there regardless of what DFS seems to wish (his own show of willfulness). JLQ because DFS is always walking away from her.

And of the two - i feel like DFS would likely take Wuyan with him, while leaving JLQ in charge of the things he doesn't care about.

So yeah. I'm still surprised Wuyan wasn't killed before DFS came back from seclusion. It's pure speculation but maybe his outward presentation of being a servant is the thing that saved him. Why does he play a servant when DFS himself is like, "You do know I think you're supposed to be standing up there with the higher ranking ppl, right?" Is it from a sense of distrust of everyone, leading him to create a persona? An emotional need to serve DFS? A not-so-secret kink? A sense of loyalty that he feels he can only express in this manner?

Just what history do they share that DFS feels comfortable enough to cry in front of him? Twice. Both times while mourning LXY/LLH.

I have so many questions.

#listen i know im couching everything in modern managerial and operations language but it's honestly not changed from ancient days to now#like even in the 80s and early 90s corporate training would trot out the Art of War to train their CEOS and upper management#it's just in wuxia land you have the option to kill someone for not delivering on their promises#mysterious lotus casebook#di feisheng#jiao liqiao#wuyan#jinyuan alliance#my royal ramblings#meta

106 notes

·

View notes

Text

#managerial work#hardback#non fiction#dust jacket#graphic design#henry mintzberg#1970s#management theory#harper collins

39 notes

·

View notes

Text

"It was at Sing Sing that the instrumentalization of new penological reform found its fullest expression. More than any other prison warden, Sing Sing’s Lewis E. Lawes insisted that the best prison was one in which the prisoners were well-fed, well-exercised, and frequently entertained. Lawes had risen through the ranks of prison administration from the position of prison guard at Clinton, in 1905, to that of Superintendent of the New York Reformatory for Boys, in 1916, and, finally, in 1920, to the wardenship of Sing Sing. He brought with him an unusually acute understanding of the peculiar problems that beset prison administrators in the years after the abolition of prison labor contracting. A first-hand witness to the great disciplinary and political crises that beset New York’s penal system in the early Progressive Era, he also had an intuitive grasp of the “unwritten law” of the prison that the convicts would forcefully defend what they took to be their fundamental rights. Between 1920 and 1943, Warden Lawes carefully and skillfully constructed a prison order based on the principle of the square deal and the morale-building techniques that Moyer had begun to refine at Sing Sing. Grasping that the stability of the prison also depended upon outside forces, he also worked tirelessly to legitimize his administration in a slew of books, articles, radio shows, and Hollywood films.

When Lawes arrived at Sing Sing in 1920 to take up his wardenship, he gave all the prisoners a clean disciplinary slate and placed them in “A” grade. As “A graders,” they were entitled to all entertainment and recreational privileges. Lawes explained that if they broke a rule, they would be demoted to “B” grade, with limited privileges. A further offense would land them in “C” grade, with no privileges. Good behavior would result in promotion to a more privileged grade. As part of this overhaul of the disciplinary system, Lawes reorganized the sale of tobacco and other comforts at the prison, linking the purchase of those “pleasures” to the disciplinary system: He merged the two commissaries to create a single grocery store, and authorized prisoners to purchase a set amount of goods each week, to be determined by the grade they were in. Lawes then set about extending sporting activities at Sing Sing and made the mass media of radio, film, and newspapers part of the fabric of everyday life. He installed a master radio receiving station in the east wing of the prison and appointed a civilian censor, who then relayed selected radio programs to loud speakers and headphone sets around the prison and cellhouse. He also expanded the prisoner baseball program, established a football team, laid down playing fields and handball courts, and gave the prisoners three hours of outdoor exercise time every afternoon in the summer months. Like Moyers and Osborne before him, Lawes continued the practice of having outside teams come to play the prisoners; in 1925, he also organized a memorable ballgame on the prison diamond, between the New York Giants and the New York Yankees (Babe Ruth was reported to have hit the ball over the field wall for a home run; unfortunately, the outcome of the game appears not to have been recorded). Although Lawes understood prisoners’ conception of their elemental rights, he recognized few of these rights as having any basis in positive law (the two he did explicitly acknowledge as properly legal were the right to attend a religious congregation of the prisoner’s choosing and the right to a minimum food allowance.) Nonetheless, Lawes’s actual management of the prisoner indicates that he understood the force of custom in the prisons and that he was very attentive to convicts’ sense of fairness in all his dealings with them.

As at other New York prisons, the new warden retained the Mutual Welfare League (MWL), chiefly as an organizing staff by which to provide entertainments, education, and recreation, and as a disciplinary agency, by which convicts who transgressed minor rules would be policed and punished. Lawes also moved to consolidate his administrative powers viz. the MWL (which, just like outside reformers and embattled politicians, was a potentially disruptive force from the administrators’ point of view). In particular, he took steps to mute the league’s voice beyond the prison walls and to curtail the scope of its activities within the prison walls. The administration clamped down on prisoners’ correspondence with the outside world, and warden Lawes established a censorship office where all prisoners’ outgoing correspondence (whether letters to loved ones or short stories for publication) and incoming mail were scrutinized for subversive content. Lawes also restructured the league’s election process and prohibited the prisoner “political parties” that had emerged in the late 1910s, on the grounds that prison-yard electioneering was overly exciting and emotional for the prisoners, and hence damaging to prison morale. From 1920 onwards, the league’s primary obligation was to regulate the leisure hours of prisoners, Lawes directed; its other obligations were to maintain discipline at these events and to represent prisoners’ grievances and requests to the warden: “The League was to be a Moral force,” insisted Lawes; “If it could not sustain itself in that capacity it was futile and should be eliminated.”

Lawes also maintained the automobile, barber, cart, and tailoring classes and made reading and writing courses compulsory for all illiterate convicts. By 1934, all convicts were routinely administered educational tests. Those achieving lower than the level of the sixth grade were then enrolled in classes taught by a civilian head teacher, two civilian assistant teachers, and twenty grade school convict teachers. Ten prisoners taught more advanced courses, and several convicts were enrolled in correspondence college courses run by the Massachusetts Department of Education. It was under Lawes that psychomedical therapies became a critical component of the disciplinary regime, not merely as a means of classifying prisoners (as the new penologists had initially envisioned them), but as a means of managing convicts’ daily frustrations, depression, and desire to rebel. Like the educational, recreational, and athletic programs, the psychomedical sciences were given over to the therapeutic pacification of convicts. Glueck’s psychiatric Classification Clinic was reorganized and funded by the state in 1926 and proceeded to surveil the entire prison population; clinicians also began attending the warden’s court to give advice on disciplining rule-breakers. Convicts were encouraged to seek psychological and psychiatric advice from Dr. Amos T. Baker and his staff of psychologists and psychiatrists. Throughout his career, Lawes repeatedly made it clear in press releases, radio interviews, and a series of books and articles that high prisoner morale was the immediate objective of his penology, and the peace and security of the prison were his foremost concerns. As he put it in an interview in 1924, under his system:

The men are no longer bottled up, constrained to silence, tyrannized and brutalized by unworthy keepers, or exploited and spied upon. They are permitted some chance of self-expression, some freedom for their personalities. They are shown humane and constructive precepts and they are not repressed, screwed down and baffled. The result is that we have almost done away with those emotional explosions so common in the older kinds of prisons. All acts of violence and attempts at escape are the result of these emotional disturbances.

Lawes conceptualized the various reforms initiated by the new penologists as means to the end of higher morale. On the question of education, for example, Lawes justified the expense of running classes for prisoners: “To me, as a warden, prison schools more than justify their continuance and expansion if for no other reason than to foster and maintain the morale of those prisoners who take advantage of the facilities offered them to study and to learn.” In a similar vein, Lawes argued for the benefits of commercial radio at Sing Sing: “I am happy to report,” he wrote in Radio Guide in 1934, “that since this system has been in vogue, the morale and behavior of the prisoners [have] rocketed sky-ward.” As Lawes conceptualized it, the proper objective of prison management was to facilitate “decent, normal and satisfying expression of personal interests.” This expression was entwined in a system of incentive and privilege that aimed at keeping the convicts more or less happy. Even fire-fighting (for which the convicts were responsible) succumbed to the logic of Lawes’s managerialism. As he wrote, “There is a keen rivalry between the different fire companies and positions on the fire department are frequently given as rewards of merit.” So, too, the death of a prisoner (by natural or other causes) became an occasion for boosting the morale of other prisoners: “When a fellow dies,” Lawes informed an audience at the New School for Social Research in 1931, “whatever his religious belief was, or if he had any, or if he hadn’t, whatever his belief was, it is respected. I don’t know if that helps a fellow that is dead any, but I think it helps the fellows who are left behind” (emphasis added).

Notably, Lawes rarely mentioned the new penological objective of restoring convicts to citizenship. Indeed, he frequently argued that crime originated in the structures and pathologies of modern industrial society itself, and would be eliminated only once those structures were themselves changed. As he saw it, “(u)nder our present social order prisons are a necessary evil.” For Lawes, unlike Osborne and the new penologists, the chief task of prison administration was not to “cure” criminals or deter crime; it was to maintain the peace and security of the prison, both within the institution’s walls and outside, in the large sphere of penal politics.

Although most, if not all, the disciplinary techniques found in Sing Sing and the other New York prisons in the 1920s owed their origins to the progressives, those techniques were being put to different uses and were taking on very different meanings than the ones progressives had intended. At Sing Sing, the enlightened “republic of convicts” became a bargaining table across which prisoners and administrators hashed out a “square deal;” the goal of making good prisoners of convicts usurped that of restoring convicts to manly worker-citizenship. The lament of one new penological investigator, in 1924, was typical:

The emphasis today is laid on the gaining of privileges as a reward for conduct rather than in stimulating the sense of individual responsibility for the common welfare, which is the basis of good citizenship. In one case the privileges are used as a (sic) end in themselves; in the other, merely as the means to a very different, and far greater end.

The disappointed observer concluded that the warden “uses the League chiefly to serve the prison administration rather than uses both the League and Administration to serve society.” Although rehabilitation remained a formal objective of imprisonment, “morale-making” was the guiding principle of the new system. Although both the new penologists and the administrators of the 1920s aimed to produce a prison order in which the convict turned outwards from his self, his soul, or his morbid unconscious and became absorbed in activities that sublimated his mental and physical energies, the new penologists had subordinated those techniques to the overriding objective of socializing prisoners as self-disciplined worker–citizens. After the war, conversely, New York’s prison wardens consistently reiterated that imprisonment’s principal task was essentially managerial in nature: The administrator’s job was to maintain what Lawes referred to as the “morale of the domain” and he was to achieve this by establishing various activities that sublimated the passions and desires of the prisoners.

The morale of the domain depended upon prisoners and keepers entering a double relationship of exchange. On the one hand, prisoners exchanged their good behavior for “good-time”: That is, if they behaved well, they would regain their liberty sooner. In the meantime, they also traded obedience for the gratifying privileges of attending (or playing in) convict baseball matches, watching movies, making use of psychiatric counseling services, and purchasing tobacco and other small pleasures from the prison commissary. Radio, cinema, recreational activities, athletics, access to a well-stocked grocery, and therapy were all part of one pervasively psychological penal order of sublimation. These various activities were comforting commodities to be purchased with the only hard currency a prisoner possessed: obedience. Lawes did not hesitate to plainly state this point: “Naturally the convicts have to pay some price for the possession of such a cherished bounty. The asking price is a matter of obedience.” At Sing Sing, in particular, but to a significant degree in Auburn and Clinton as well, prison order came to rest on a more or less tacit agreement between prisoner and keeper that the former could purchase some measure of pleasure from the latter by resisting the urge to cause trouble. Morale-building, as a technique of maintaining peaceful institutions, took the place of moral reform.

Within a few years of arriving at Sing Sing, Lawes had completed the transformation of the original new penological project into a new, managerialist penal order. Although elements of this penal managerialism could be found in other New York prisons (and in a number of other states, including Texas, Minnesota, Illinois, and California), nowhere was it as fully and systematically developed as at Sing Sing. In the few years either side of 1930, three separate, though related, strings of events – the Baumes laws, prison riots at Auburn and Clinton prison (but not at Sing Sing) and federal regulation of prison labour - would propel Lawes’s system to national notice and reinforce the relevance and utility of penal managerialism."

- Rebecca M. McLennan, The Crisis of Imprisonment: Protest, Politics, and the Making of the American Penal State, 1776-1941. Cambridge University Press, 2008. McCormick, p. 443-449.

The photo shows an officer instructing a Sing Sing prisoner on bed-making, from Lewis E. Lawes, Twenty Thousand Years in Sing Sing. New York: A. L. Burt Company, 1932, p. 176.

#sing sing prison#penal reform#penal modernism#managerialism#prison discipline#prison administration#crisis of imprisonment#new york prisons#classification and segregation#mutual welfare league#sports in prison#history of crime and punishment#academic quote#reading 2023#psychiatric examination#prison psychiatry#lewis lawes

1 note

·

View note

Text

hi. for ppl who jumped the twitter ship. im quitting my job suddenly and missing out on what was going to be a good week of pay so if anyone wants to toss like ten bucks for an icon or something so i can eat in the meantime i would GREATLY appreciate it

#talking#and in case ur wondering i got sent home yesterday for finding someone to cover a coworker's lunch break. and the manager threw a fit#yesterday was all kinds of fucked from a managerial point though. but until we were sent home i didnt think much#bc that place was an actual dumpster fire. lmao#anyway yayyyyy jobhunting. did not think this would be my out from a job that i liked and liked me. but oh well

73 notes

·

View notes

Text

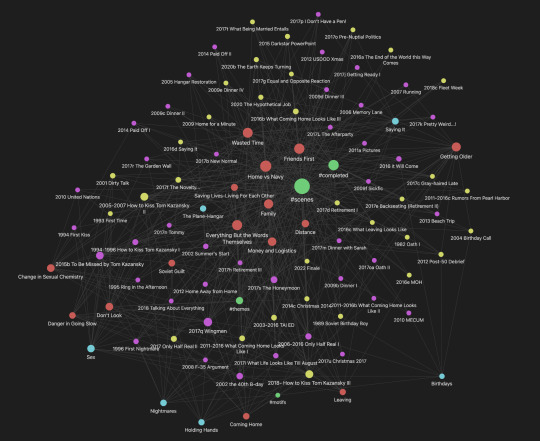

wip wednesday: made a HUGE amount of progress this week (for context—purple is unfinished & yellow is finished; last week all of them were purple) … i am in the home stretch here

#and then… it will be time for me to say goodbye i think#some darkstar politics in here#driven by an essay I read last year titled tinted blue: Air Force culture & American civil-military relations#everyone has a different idea of what modern warfare will look like#1 & 2 are from the same section obviously… i just think it’s interesting#& i wrote elsewhere in may maybe that ice & mav would be on opposite sides of this debate#ice with his big picture managerial perspective… it’s good for warfare… mav with his specialist pilot loyalty POV#obviously their conversation predates the russia-ukraine war which has shown drone warfare in its fullest to date potential#4. is… idk. does it help to tell you it takes place in 2014?#3. *#pete maverick mitchell#tom iceman kazansky#icemav#top gun#top gun maverick#top gun fanfiction#sorry for the like defense ethics conversations if that’s boring#i just think that stuff is philosophically so interesting

72 notes

·

View notes

Note

I like how libs, mostly white cishets, talk about how trump is worse than Biden while using every minority under the sun as their scapegoat victim. "oh but gay people will suffer worse under trump" "oh but minorities will suffer worse under trump" "oh but disabled people will will suffer worse under trump" instead of asking the people they seem to be "fighting" for what they think. And the smugness too thinking they figured it out and how they are the main smart person that has figured it out and everyone around them is stupid. I honestly do hope trump wins and is as horrible as they say he will be they really deserve it. Oh and this coming from someone who is gay, a minority, and disabled, Biden has materially been worse than trump has been. If the vote blue maga people want to do something useful they should kill themselves

I like how libs, mostly white cishets

I think the problem is less their physical identity and more that they're comfortable petite bourgeois/Professional-Managerial Class types. For them, Trump is worse than Biden. While the PMC isn't exclusive to the Democratic Party, that's where you'll find that they predominate. They're the same people that are saying "what do you expect me to do, NOT work at Raytheon?"

Minorities, the disabled, etc, sure, they care about them, but only insofar as they care about themselves as a part of that group. This mindset is fixed in their heads even if only subconsciously because their own position requires exploiting all those identities as they exist in the working class. Sure, they care about the quality of life of their paraplegic employees, but they'd damn well better clock in on time.

The promise of the Democratic Party is that its members aren't supposed to be touched by the same miseries as the hoi polloi. Their credentials mark them out as a better sort of person. They're smarter, they worked harder, they earned it. They don't really have a problem with the GOP preying on people, they have a problem with the GOP preying on them. Just take this leaking dickhole as an example:

It's fine to talk shit about Biden! 😌 But you still better vote for him🤬

The problem isn't that Trump is deporting people. Biden's busy doing that very fucking thing, after all. No, the problem is that now the wrong people might be deported! This is so much worse than when regular brown illegals get imprisoned and deported en masse.

You can take the right to abortion as another example. Trump's plan is to let the states figure it out for themselves. Well, it turns out that's the Democrat plan too. The Democrats and the PMC aren't really concerned about abortion because their class position basically guarantees they'll be able to get it. They live in states where its protected, or they have the money to take care of the problem some other way if the need arises. It's an abstract problem for them. Their only real fear is if that suddenly isn't the case, that they would face the real problems of regular people. That's the terror and threat of Trump to them, not that he'll commit genocide like Biden is, but that their ass might be the one in the fire this time, which of course makes Trump "worse."

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

Nie MingJue, the unintentional kidnapper

Or that time A-Yuan almost got adopted into the Nie Sect

Nie MingJue is starting to get slightly uncomfortable. Sure, it has been decades since HuaiSang was a toddler (two decades, to be more specific), but surely toddlers need to blink more? The child is looking at him like he is the most mesmerising vision it has ever seen in its entire 4 years on earth.

He tries to glance through the door without being too intruding. He understands there is a touching reunion happening somewhere inside, and God knows he doesn't want to interrupt the Jiangs screaming and crying and hitting and hugging their wayward prodigal demonic cultivator, but surely someone else can take the child? Is it not a cousin of the Ghost General and her terrifying sister? Now he thinks about it, he is not so sure they are very fit guardians if they are willing to abandon their charge to any random cultivator. And the worst part is A-Yao, the person best suited to deal with this situation, has left with them, presumably trying to find a quieter resting place for the Wen remnants away from the chaos that is the 100 days celebration of the newest Jin baby.

He flinches when a soft finger cautiously pokes his cheek. The child grins guilelessly at him and says, "Pretty gege!"

Nie MingJue blushes to the root of braids. That's it! This child is obviously surrounded by unreliable people who would teach him utter nonsense or dump him in the middle of enemy territories, so as a responsible adult, it is his solemn duty to adopt the child (a boy? It is dressed as one, but who knows with Wei Wuxian?) and take it to Qinghe. He stands up with the child under one armpit, the child seemingly unbothered by being dangled like a sack of potatoes.

"He's mine!"

Lan Xichen's baby brother looks just as angry as he did on the day they first met, when he ended up biting HuaiSang. Except now he is almost as tall as MingJue, and he has already put the tip of his finger on his sword.

Rude!

Nie MingJue, a sect leader and the chief cultivator, is an older brother first and foremost. How can he resist ruffling Lan Er-Gongji's already ruffled feathers even more?

"I didn't know Wangji had a child."

Wangji bristles even further, reminding him of the time he accidentally stepped on Second Mother's cat's tail.

The child waves at him from his precarious position, "Rich Gege!"

Does Wangji's eyes soften a little? Nie MingJue can swear he saw a crack of smile in his lips. Surely, he is just hallucinating. The child chirps out again, "Pretty Gege!" pointing at MingJue. The room temperature plummets several degrees.

"GIVE HIM TO ME!"

If Wangji doesn't want to take over from Lan Laoshi, he can easily earn his living teaching enunciation to rich masters. Nue MingJue heard every syllable distinctly, including the single exclamation mark at the end. Is he serious?

Nie MingJue stares at him. He has heard rumours. The light bearing lord! The war has done awful things to the cultivators. Once kind, just men have been reduced to butchers with enough trauma to last a few lifetimes, but surely it hasn't changed the upright young man in front of him to such an extent that he was willing to...

He moves the child from underneath his arm and settles him down on the ground behind him.

"Look here, Wangji, he is just a child..."

He gets interrupted again by the same clear, obstinate tone.

"Give him to me! Now!"

Has Wangji lost it? Does he want to kill a child, practically a baby, to avenge his father and his sect? Does he really think he can get away with killing the adopted child of Wei Wuxian when Wei Wuxian himself was just a few doors away? Not to mention the Ghost General and the Jiang sect leader in the vicinity?

You can probably cut the tension with a blunt sabre. That's the first thing Lan Xichen notices when he walks in, the second thing being his brother and his best friend locked in a staring contest. Wangji looks like he is ready to start a fight, and Da-Ge has that little mocking smile, which means he is happy to indulge. Behind him, little A-Yuan is studiously examining the pattern on the carpet.

Wangji breaks the stare first. He turns to his big brother and says, almost petulantly,

"He's not giving A-Yuan back!"

Lan Xichen smiles and shakes a deprecating finger at MingJue in mock sensor,

"Now, now, what do you mean by not handing over my nephew to my brother? Da-ge! If you indeed want a child,..."

Wait a second! The jibe about the child being Wangji's, that was purely a taunt. Is it true? Did Wangji really have a child? A 4 years old? But, he begs your biggest pardon, Wangji is a child himself! How can he have a child? When? With whom?

Having his sympathetic brother on his side seems to encourage Wangji to speak further.

"A-Yuan called him pretty!"

If only people could see their Light bearing Lord pouting! Xichen tuts.

"For shame, Da-Ge!"

But before Nie MingJue can demand explanation, A-Yuan decides he has had enough of the carpet and stands up, then walks over to Lan Wangji in a brisk, businesslike manner, who bends down to pick him up without breaking eye contact with Nie MingJue and pointedly kisses the child's forehead.

Nie MingJue is pretty sure he is having a Qi deviation right now. Ah well, there are worse ways to go, he supposes.

#mdzs#mo dao zu shi#mdzs crack#pure crack#nie mingjue#lan wangji#a yuan#wen yuan#lan xichen#Just imagine Wei Wuxian brought the whole burial mound to the Carp Tower for Jin Ling's 100 days celebration#of course he and the Jiang siblings have a lot to catch up on#and Jin ZiXuan needs to hold the baby while patting Jiang Yanli on the back#And Jin GuangYao needs to somehow accommodate few extra dozen of people! Managerial nightmare!!#Wait! Nie MingJue is just sitting there! Let him mind the toddler for a while!#Lan Wangji believes his precious son almost got kidnapped by the chief cultivator

33 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Amazing Digital Managerie (2/3)

#the amazing digital menagerie au#managerie Jax#managerie Kinger#the amazing digital circus#tadc#procreate#tadc fanart#fanart#jax#kinger#unicorn Kinger#and Jax who’s stays mostly the same#just with new drip#and a bit of a different role from the others#but I’ll get into that some other time

119 notes

·

View notes