#mammoth genome

Text

#nicevice Parade

It has been a good season-🥲

Cherish every memory

#art#drawing#doodle#fanart#kamen rider revice#kamen rider vice#kamen rider#仮面ライダー#仮面ライダーバイス#仮面ライダーリバイス#rex genome#eagle genome#mammoth genome#ptera genome#megalodon genome#lion genome#jackel genome#kong genome#kamakiri genome#brachio genome#ultamate vice#neo batta genome#kamen rider jack revice#chibi vice#nice vice

52 notes

·

View notes

Note

You're being targeted by the CIA on Twitter

Oh MOTHERFUCKER LMAO

Where's the option for "both, and still do"

#one of my top research labs I applied to was a paleogenomics lab that helped assemble the neanderthal and mammoth referenxe genomes#still kinda salty i didnt get in to that uni lmao

103 notes

·

View notes

Text

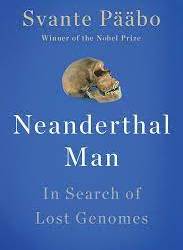

Neanderthal Man Book Review

I just finished reading Neanderthal Man by Svante Pääbo, and I would like to share my thoughts with you.

What is this book about? It's a memoir that follows Svante's quest to extract ancient DNA. First from mammoths and then from Neanderthals. It even includes a chapter on the Denisovans.

What do I like about this book? I like how the author explains complex procedures in easy to understand language and writes in a conversational style. Also, I found the narrative flow easy to follow and engaging. I learned so much that I hadn't known before!

What do I dislike about this book? At times, the author would interrupt his narrative about the search for mammoth and then Neanderthal DNA to talk about his personal life. This bit of information seemed out of place and not integral to the main story. It seemed better suited in an author's note or in a separate memoir about his life.

What do I rate this book? I rate this book a four out of five stars.

Would I recommend this book? Yes!

Why would I recommend this book? I would recommend this book because it provides a lot information on ancient DNA, mammoths, Neanderthals, and our Pleistocene ancestors.

To whom would I recommend this book? I would recommend this book to anyone who has an interest in ancient DNA, Neanderthals, anthropology, or scientific memoirs.

Note: If you liked this book, I would recommend A Brief History of Everyone Who Ever Lived by Adam Rutherford.

Well, that's all I have for today. Until next time, take care and stay curious.

#lgbtqia#bisexual#dna#ancient dna#mammoths#neanderthal#denisovans#pleistocene#Svante Pääbo#genomics#book review#personal opinion#memoir#anthropology

0 notes

Text

project to bring back the woolly mammoth (or something similar) is making progress ...

0 notes

Text

Thinking about this post. "The only way to make a cell is from another cell" is somewhat of a troubling fact to me. I mean, not for any practical reason, just because it underscores the precarity of *gestures broadly*.

It's like, some people talk about trying to de-extinct the mammoth. And people are trying to sequence the genome of the mammoth, I don't know if they've done it yet. But even if they do, one of the problems with the idea of de-extinction is... to grow a baby mammoth, you need another mammoth! Last time I heard people talking about this, I think they were talking about using an elephant as a surrogate mother. But imagine if elephants were extinct too.

The point is that information is often tied to the systems that transmit it; even if you know everything in the mammoth genome, once all the mammoths are gone there's nothing capable of reading and using that information. Like when you can't read the data on a perfectly good floppy disk because your computer doesn't have a floppy drive.

This is related to why language death troubles me so much. Even the most well-documented languages aren't actually that well understood; linguists have produced more pages of work on English syntax than maybe any other specific descriptive topic and yet still the only reliable way to get the answer to any moderately subtle syntactic question is elicit native speaker data. We know almost nothing, we can barely extrapolate at all! And every language is like this, a hugely complex system that we know basically nothing about, and if the chain of native speaker transmission is ever broken it's just gone.

"Language revival", I mean from a totally dead language, is kind of a myth. It's like the "came back different" trope. In Israel they revived Hebrew, but Modern Hebrew is really not the same thing as Biblical Hebrew at all. I mean in a stronger sense even than Modern English isn't Old English. All the subtleties of Biblical Hebrew that a native speaker would have had implicit competence with died without a trace. All they left is a grainy image, the texts. The first generation of Modern Hebrew speakers took the rough grammatical sketch preserved in these texts and imbued it with new subtleties, borrowed from Slavic and Germanic and the speakers' other native languages, or converged at by consensus among that first generation of children. There's nothing wrong with that, but it would be inaccurate to imagine Biblical Hebrew surviving in Modern Hebrew the way Old English survives in Modern English. For instance, you can discover a great deal that you didn't know about Old English by comparing Modern English dialects. There is nothing you can discover about Biblical Hebrew by comparing Modern Hebrew dialects in this way.

There's nothing wrong with this, of course. I'm not like, judging Modern Hebrew. I'm just making a point.

Mammoths died recently, so we still have (some of?) their genome. Something that died longer ago, like dinosaurs, we have traces of them in the form of fossils but we could never hope to revive them, the information is just gone. Even if we're not aiming for revival, even if we just want to know stuff about dinosaurs, there's so much that we will never know and can never know.

We imagine information as the kind of thing which sits in an archive, because this is the context most of us encounter information in, I think. Libraries, hard drives. Well obviously hard drives don't last. And most ancient texts only survive because of a scribal tradition, continuous re-writing, not because of actual archival. So I think that imagining archives as the natural habitat of information is sort of wrong; the natural habit of information is in continuous transmission. Information is constantly moving. And it's like one of those sharks, if it ever stops moving it drowns. And if the lines of transmission are broken, the information is gone and can never be retrieved.

Very precarious.

1K notes

·

View notes

Note

hey! I was wondering if you ever watch clints reptiles - he just posted a video about marcupeal phylogeny and specifically mentioned thylacines, and talked about how theres been sightings in new guinea? i was just wondering about your opinion, since you just posted a new thylacine drawing and i know youre very interested in them :D

idk, the fact i haven't heard all that much buzz about this theory from the zoologists i follow on twitter makes me doubtful by default.

i'll be honest i'm pretty skeptical of this new guinea claim because of dingoes and new guinea singing dogs.

the popularly accepted theory for the mainland extinction of the thylacine and likely tasmanian devil was competing pressure from dingoes.

clint mentions all of this, but he leaves out the fact that dingoes arrived on the australian continent from the north and studies indicate that dingoes may be descendants of more basal new guinea singing dogs. that would likely mean imo that the new guinea thylacine population, if anything, would be the first to suffer the consequences of canine encroachment.

only on the island of tasmania where absolutely no dingoes were ever present sheltered a 100% verifiable thylacine population by the time of european colonization. to my knowledge, the most recent solid physical evidence of thylacines in new guinea is still several thousand years old. so to me it seems that dingo/wild dog distribution and thylacine distribution mixed as well as oil and water. If there's thylacines in new guinea, it would have to be some enclave free of dogs.

i know the topography of new guinea can give refuge to very cryptic animals, and as clint said the relatively low human population and no european persecution is a plus. i won't disocount local indigenous anecdotes because they've been proven right with other species once thought extinct, but like where are skins or bones or footprints?

also i feel like clint really really oversimplified the cloning process thylacines would require. he makes it seem like it would be simple because we have their whole genome sequenced and have specimens under 100 years old to work with. the thing is, cloning a mammoth is simpler than cloning a thylacine even though they went extinct millenia ago, because mammoths still have a close living relative.

a cursory look at google tells me wooly mammoths and extant asian elephants last shared an ancestor as recently as 6 million years ago, they both belong to the family elephantidae. thylacines however were the last living member of their own family, thylacinidae, which diverged somewhere around 25mya from the other dasyuromorphs. scientists don't really have a close living relative to work with. clint says the complete genome means we wouldn't have to "stick frog DNA in there" to complete it, but the thing is with cloning you have to start with a frog/living DNA sample to tweak it into a thylacine!! until we can 3D print an organism out of thin air with proteins and acids, there has to be a template sample of living cells whose nuclei we can tamper with. and the less related they are, the more DNA has to be overhauled

if you wanna learn exactly how much of a logistical nightmare it's gonna be to clone a thylacine, this lecture explains it way better:

youtube

the takeaway analogy is that cloning a thylacine is the CRISPR equivalent of doing a puzzle of a clear blue sky, not having the box to look at for any reference, and about half the pieces are doubles of other pieces (because most DNA is junk code that does nothing). it's like next to impossible and i still have more faith in de-extinction than a rediscovery.

so yeah, i guess i'm a bit of a thylacine doomer. but i do want to believe, just temper your expectations. to me a win would be a single engineered thylacine cell by the centennial of their extinction lol.

71 notes

·

View notes

Text

Recent efforts in de-extinction have focused on the Tasmanian tiger, as its natural habitat in Tasmania is still mostly preserved, and its reintroduction could help recovering past ecosystem equilibriums lost after its final disappearance. However, reconstructing a functional living Tasmanian tiger not only requires a comprehensive knowledge of its genome (DNA) but also of tissue-specific gene expression dynamics and how gene regulation worked, which are only attainable by studying its transcriptome (RNA).

"Resurrecting the Tasmanian tiger or the wooly mammoth is not a trivial task, and will require a deep knowledge of both the genome and transcriptome regulation of such renowned species, something that only now is starting to be revealed," says Emilio Mármol, the lead author of a study recently published in the Genome Research journal by researchers at SciLifeLab in collaboration with the Centre for Paleogenetics, a joint venture between the Swedish Museum of Natural History and Stockholm University.

87 notes

·

View notes

Text

I've realized something about de-extinction projects that never truly crossed my mind before. Of course, the 'resurrected' animals (woolly mammoth, thylacyne, dodo, what have you) are very unlikely to even BE themselves because of the surrogate parent, the incomplete genome, the fact that we're ultimately going into this from the point of view of someone doing a reconstruction. But what about the social aspects? Who's going to teach the first 21st century woolly mammoth baby how to be a woolly mammoth, it's very unlikely the genome it has is going to instinctively tell it what to do. And what if it does? Can we cope? What happens if a woolly mammoth baby has the innate desire to start migrating in the middle of autumn the same way birds and other large herbivores seasonally migrate. But that's learned behavior, who's going to teach that? Who is going to teach them mammoth. Pachyderms are social animals, are you gonna keep it isolated? among other elephants? What of the social dynamics of being reared up among animals that look similar to you but not QUITE, again what about innate behaviours that will make it be an outcast? What happens if that de-extincted animal, sole of its mutated kind, reaches maturity? Will it be allowed to mate?

Idk, why should we create something just to doom it ugly duckling style.

Edit: like the panda in this post. behavior of extinct species is something that is going to be almost entirely lost and even if we have evidence of it replicating it for a de-extincting species that might only have 1 individual in human care is near impossible.

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

Around 40 000 years ago, Homo Sapiens came to Europe and genocided Homo Neanderthalensis (Adams event?). Thus, all modern humans in Europe and Northern Africa have a bit of Neanderthals DNA.

Logically, the Neanderthals DNA should have disappeared completely in modern humans by now... but it didn't. Why? Most likely because of adaptive introgression: process by which adaptation occurs via genetic variants that were introgressed into the recipient population from the donor population (introgression - incorporation of DNA from one species to the gene pool of another). Sapiens really needed some Neanderthals genes for protection from European infections.

The problem, however, is that Neanderthals genes protect us from infections in a short run. In a long run, our Sapiens bodies start to consider Neanderthals DNI as the alien DNI, causing rejection, which leads to different autoimmune disorders and sometimes even cancer. The bloodline curse we have to bear is paying for sinners of our ancestors...

In particular, biologists and archaeologists established a connection between Neanderthals DNI and kidney membranous neuropathy: the more you have Neanderthals genes, the higher the chance to develop such unpleasant disorder. COVID-19 severity is also dependent on the Neanderthal genome.

Neanderthals had lived in quite cold places in those times, and thus, they had to eat more meat. "Alas, though fat is easier to digest, it’s scarce in cold conditions, as prey animals themselves burn up their fat stores and grow lean. So Neanderthals must have eaten a great deal of protein, which is tough to metabolize and puts heavy demands on the liver and kidneys to remove toxic byproducts. In fact, we humans have a “protein ceiling” of between 35 and 50 percent of our diet; eating too much more can be dangerous. Ben-Dor thinks that Neanderthals’ bodies found a way to utilize more protein, developing enlarged livers and kidneys, and chests and pelvises that widened over the millennia to accommodate these beefed-up organs. To cope with the fat famine, Neanderthals probably also specialized in hunting gigantic animals like mammoths, which retain fat longer in poor conditions and require greater strength but less energy and speed to kill."

Since Neanderthals had such large kidneys, they needed a greater scale of kidney cleansing. And that's why they ate a lot of cranberries and lingonberries: even nowadays, cranberries extract is sold in pharmacies to people with kidney problems.

Cranberries properties: rich in antioxidant compounds, prevention of urinary tract infections, support anti-aging, skin health, heart health, reduce the risk of stomach ulcers, antibacterial properties, protect against certain cancers, support eye health and vision, promote a healthy immune system, etc.

Lingonberries are especially high in the antioxidant "anthocyanins," which is known to prevent oxidation of blood cholesterol and aid in keeping blood vessels healthy. Researchers believe these potent antioxidants may be able to help reduce the risk of heart disease and even some cancers.

Thus, people with kidney memranous neuropathy or with high risk of its development, people with severe post-COVID complications, people with high levels of Neanderthals DNI should come to Lithuania! :D We have a lot of cranberries and lingonberries sold not in pharmacies at wild prices but in average grocery stores! :D

#history#biology#medicine#archaeology#covid 19#post covid#membranous neuropathy#kidney disease#neanderthals#genetics#Lithuania#health#healthy food

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Had an interesting conversation with my boyfriend the other day about Jurassic Park, because along with the message "theme park of dinosaurs bad" he also interpreted the message of the movie as "cloning extinct animals bad," and didn't really think about ways cloning extinct animals could be useful at all. Cloning is simply a tool, and in the right hands it could be incredibly beneficial.

Cloning creatures without modern habitats, like mammoths and dinosaurs, is probably both impossible and impractical. I will not argue about that. I agree with my boyfriend on that part.

But similar to artificial insemination, cloning could be a very powerful tool to save species on the brink of extinction (or extinct in the wild) that would benefit from some more diversity in their genome.

Did you know that the Scottish wildcat is extinct in the wild because it's interbred too much with domestic cats? Don't you think the remaining ones might benefit in some way from having a few mates that aren't the neighbor's kitty?

We know every single kākāpō parrot by name, because domestic cats and rats were the second worst thing to ever happen to New Zealand. Kākāpō breed when their food source of berries experiences a bumper crop. A bird named Lisa crushed one of her eggs in 2014, and it was so precious that the conservation team opted to tape and glue the shell back together. Ruapuke, who successfully hatched from it, turns ten in February 2024. But the birds are having issues with fertility now, because of the small gene pool, resulting in fewer successful eggs. Sure would be nice if we could create a couple of healthy kākāpō from museum specimens to diversify the genome, huh?

I'm not saying cloning will be the miracle fix for conservation in the future. Cloning has its own inherent difficulties I won't delve too far into. The success of a species also depends on whether or not it has a place to live that it can thrive in. But if funding wasn't a roadblock, and since these populations are so incredibly low, I think some of these animals could greatly benefit from it.

So yeah, dinosaurs aren't coming back, but I'd appreciate it if we had a few extra wild cats.

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

Woolly mammoth (Mammuthus primigenius)

(temporal range: 0.40-0.0037 mio. years ago)

[text from the Wikipedia article, see also link above]

The woolly mammoth (Mammuthus primigenius) is an extinct species of mammoth that lived during the Pleistocene until its extinction in the Holocene epoch. It was one of the last in a line of mammoth species, beginning with the African Mammuthus subplanifrons in the early Pliocene. The woolly mammoth began to diverge from the steppe mammoth about 800,000 years ago in East Asia. Its closest extant relative is the Asian elephant. The Columbian mammoth (Mammuthus columbi) lived alongside the woolly mammoth in North America, and DNA studies show that the two hybridised with each other.

The appearance and behaviour of this species are among the best studied of any prehistoric animal because of the discovery of frozen carcasses in Siberia and North America, as well as skeletons, teeth, stomach contents, dung, and depiction from life in prehistoric cave paintings. Mammoth remains had long been known in Asia before they became known to Europeans in the 17th century. The origin of these remains was long a matter of debate, and often explained as being remains of legendary creatures. The mammoth was identified as an extinct species of elephant by Georges Cuvier in 1796.

The woolly mammoth was roughly the same size as modern African elephants. Males reached shoulder heights between 2.67 and 3.49 m (8.8 and 11.5 ft) and weighed up to 8.2 metric tons (9.0 short tons). Females reached 2.6–2.9 m (8.5–9.5 ft) in shoulder heights and weighed up to 4 metric tons (4.4 short tons). A newborn calf weighed about 90 kg (200 lb). The woolly mammoth was well adapted to the cold environment during the last ice age. It was covered in fur, with an outer covering of long guard hairs and a shorter undercoat. The colour of the coat varied from dark to light. The ears and tail were short to minimise frostbite and heat loss. It had long, curved tusks and four molars, which were replaced six times during the lifetime of an individual. Its behaviour was similar to that of modern elephants, and it used its tusks and trunk for manipulating objects, fighting, and foraging. The diet of the woolly mammoth was mainly grasses and sedges. Individuals could probably reach the age of 60. Its habitat was the mammoth steppe, which stretched across northern Eurasia and North America.

The woolly mammoth coexisted with early humans, who used its bones and tusks for making art, tools, and dwellings, and hunted the species for food. The population of woolly mammoths declined at the end of the Pleistocene, disappearing throughout most of its mainland range, although isolated populations survived on St. Paul Island until 5,600 years ago, on Wrangel Island until 4,000 years ago, and possibly (based on ancient eDNA) in the Yukon up to 5,700 years ago and on the Taymyr Peninsula up to 3,900 years ago. After its extinction, humans continued using its ivory as a raw material, a tradition that continues today. With a genome project for the mammoth completed in 2015, it has been proposed the species could be revived through various means, but none of the methods proposed are yet feasible.

16 notes

·

View notes

Note

Will it ever be possible to bring non avian dinos back to life?

Short answer: No.

Long answer:

DNA does not last very long, in the scheme of things. It has a half-life of about 521 years, which means at its absolute maximum, DNA material can last 6.8 million years. And the nearest non-avian dinosaur is about 10 times that, at 66mya.

Even in amber, the preservation of DNA is fuzzy at best. While a few studies in the 90s did claim to have extracted ancient insect DNA from amber, because yes we definitely did immediately try to recreate Jurassic Park, we've since had trouble recreating the results. While studies are currently being done on modern samples, to try and see how far back DNA extraction can work, so far we don't have any confirmation of the potential to extract DNA from ancient amber. So even those dinosaur fragments in amber aren't helping us.

There are ethical debates about de-extinction as well. We've figured out a complete mammoth genome, but currently the debate is SHOULD we bring back mammoths, and WHY. The environment mammoths used to live in, that they were adapted to, are gone now; the world is very different. Probably a lot of the plants they ate are gone, even the air composition is different. Would a mammoth suffer, if you were to bring it into the modern world? And then there's the nature vs nurture problem - would a cloned mammoth, likely born to an elephant surrogate and raised by an elephant surrogate, act like a mammoth? Or would it act.... like a modern elephant? And if that is potentially the case, then why even bring the mammoth back, when you can't study it to learn more about mammoths? All of these arguments apply tenfold when you think about dinosaurs. There is potentially very little scientific gain to such a venture.

There is Jack Horner's famous Chickenosaurus project, which is an intriguing idea, at least, but will at the end of the day just give us a bird that.... looks like a non-avian dinosaur. Currently the project is stalled by the fact that non-avian dinosaur tails don't have an atavistic gene to turn back on, unlike teeth. There's a lot of debate as to if this will even be possible - and again, what real scientific value is there in doing it - but even assuming it is, it won't bring any non-avian dinosaurs back to us.

So no, realistically, we're probably never going to get non-avian dinosaurs back. It's a fun little dream, but it'll probably stay just that. But at least we have their fossils, so that we can still study them, and at least we have birds, so that we can still know them.

[Links go to paper, video, and article sources]

162 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Texas entrepreneur working to bring back the woolly mammoth has added a new species to his revival list: the dodo.

Recreating this flightless bird, a symbol of human-caused extinction, is a chance for redemption. It might also motivate humans to remove invasive species from Mauritius, the bird's native habitat, said Ben Lamm, CEO and co-founder of Colossal Biosciences.

"Humanity can undo the sins of the past with these advancing genetic rescue technologies," Lamm said. "There is always a benefit for carefully planned rewilding of a species back into its native environment."

The dodo is the third animal that Colossal Biosciences — which announced Tuesday it has raised $225 million since September 2021 — is working to recreate.

And no, the company isn't cloning extinct animals — that's impossible, said Lamm, who lives in Dallas. Instead, it's focusing on genes that produce the physical attributes of the extinct animals. The animals it's creating will have core genes from those ancestors, engineered for the same niche the extinct species inhabited.

The woolly mammoth, for instance, is being called an Arctic elephant. It will look like a woolly mammoth and contribute to the Arctic ecosystem in a way that’s similar to the woolly mammoth. But it will technically be an Asian elephant with genes altered to survive in the cold. Asian elephants and woolly mammoths share 99.6 percent of their DNA.

The mammoth was the company's first project because it had long been a passion for Harvard University geneticist and Colossal co-founder George Church. He believes that Arctic elephants are the key to creating an Ice Age-like ecosystem with grasslands and grazing mammals, and this could help fight climate change by sequestering carbon under permanently frozen grounds that span areas including Siberia, Canada, Greenland and Alaska.

The altered genes could also give elephants a new habitat that’s far away from the destructive forces of (most) humans, and the company's gene editing technologies could help eradicate elephant diseases.

The company's de-extinction projects seek to fill ecological voids and restore ecosystems, Lamm said. The Tasmanian tiger, which Colossal announced as its second de-extinction animal in August of 2022, is a good example. This tiger was the only apex predator in the Tasmanian ecosystem. No other animal filled its place when it went extinct.

Apex predators eat sick and weak animals, which helps control the spread of disease and improves an ecosystem's genetic health. So the tiger's extinction could have contributed to the near-extinction of Tasmanian devils that lived in the same ecosystem, Lamm said.

For the dodo, Colossal is partnering with evolutionary biologist Beth Shapiro, a scientific advisory board member for Colossal who led the team that first fully sequenced the dodo's genome.

The dodo went extinct in 1662 as a direct result of human settlement and ecosystem competition. They were killed off by hunting and the introduction of invasive species. Creating an environment where the dodos can thrive will require humans to remove the invaders (the non-human invaders, anyway), and this environmental restoration could have cascading benefits on other plants and animals.

"Everybody has heard of the dodo, and everybody understands that the dodo is gone because people changed its habitat in such a way that it could not survive," Shapiro said. "By taking on this audacious project, Colossal will remind people not only of the tremendous consequences that our actions can have on other species and ecosystems, but also that it is in our control to do something about it."

The company has secured $150 million in funding to revive this bird and build an Avian Genomics Group, bringing the company's total fundraising to $225 million.

Colossal has more than 40 scientists and three laboratories working to recreate the woolly mammoth, and they hope to have mammoth calves in 2028. There are 30 scientists working on the Tasmanian tiger.

Reviving extinct animals is not a quick process, especially when considering the development of new technologies and the natural processes of Mother Nature (elephant gestation takes 22 months!). Some of Colossal's projects will take nearly a decade to complete, which is why the company is working to reintroduce multiple animals at the same time.

"Given the rapidly changing planet and various ecosystems heavily influenced by humankind, we need more tools in our tool belt to also help species adapt faster than they are currently evolving," Lamm said.

And the tools aren't limited to extinct animals. Colossal is developing technology that can benefit other industries, and it's spinning these out into new companies. Last year, it spun out a software platform called Form Bio that's designed to help scientists collaborate and work with their data, visualizing it in meaningful ways rather than looking at raw numbers in a spreadsheet.

"Synthetic biology will allow the world to solve various human-induced, world-wide problems," Lamm said, "like making drought-resistant livestock, curing certain disease states in humans, creating corals that are tolerant to various salinities and higher temperatures ... and much more."

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

1 note

·

View note

Text

ok so writing those tags did make me wanna check out the latest longreads roundup and man, I'm really enjoying the de-extinction article

In the eyes of some researchers, the best candidate for de-extinction is an animal some might wish were extinct: a rat. When Thomas Gilbert, a genomics researcher at the University of Copenhagen, sat in at some of the first de-extinction meetings at National Geographic in 2012, he remembers a brainstorm of what species the efforts should focus on. Suggestions of mammoths, Steller's sea cows, and woolly rhinos were all met with lots of attention. "Then I go, 'Christmas Island rat,' just to see what happens," Gilbert said. "And it was just like, dead silence."

nobody wanted to work with the unglamorous christmas island rat 😔

(link)

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

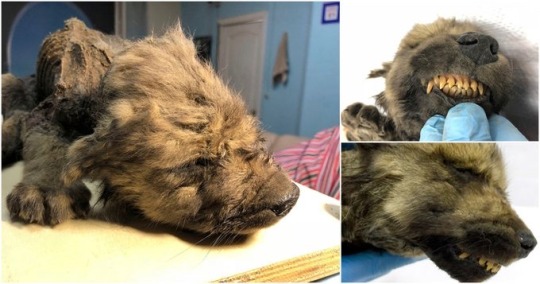

In Siberian Permafrost, An 18,000-Year-Old Puppy Was Discovered - Hasan Jasim

After being discovered in the depths of Siberia’s permafrost, a fascinating prehistoric pup has experts scratching their brains.

The puppy’s name was “Dogor,” which means “Friend” in the Yakut language spoken in the area. It was reported to be only two months old when it died. It was discovered in Siberia, north-east of Yakutsk, near the Indigirka River, and was recently researched at the Swedish Centre for Palaeogenetics (CPG).

The ancient canine has survived in amazingly fine shape, complete with fur, whiskers, and teeth, thanks to the permafrost, which acts as a natural refrigerator. However, researchers are still unaware of what species this curious creature previously belonged to.

While preliminary genome sequencing revealed that the specimen is male and 18,000 years old, it was unable to determine if it is a wolf, a dog, or a proto-dog common ancestor of the two.

“Despite having Europe’s largest DNA database of all dogs from around the world,” Love Dalén, professor of evolutionary genetics at the CPG, told The Siberian Times, “they couldn’t identify it on the first try in this case.”

“What if it’s a dog?” says the narrator. “We can’t wait to see the results of more testing,” said Sergey Fedorov of the North-Eastern Federal University in Yakutsk’s Institute of Applied Ecology of the North.

Around 32,500 years ago, humans began to settle in this northern area of Russia. In addition, earlier study suggests that humans domesticated dogs from wolves between 10,000 and 40,000 years ago. Dogor might theoretically fit anywhere within this range, whether as a devoted home dog, a voracious wild wolf, or anything in between.

Permafrost produces ideal conditions for the preservation of organic materials. The sub-zero temperatures are just enough enough to prevent most bacterial and fungal development from decomposing the body, but not so cold that the tissues are damaged. Scientists are occasionally able to obtain viable DNA fragments that can be used to sequence the genome of the organism in question if the conditions are just perfect.

The 40,000-year-old head of an ice age wolf, still coated in skin and fur, discovered last year in the Abyisky district of northern Yakutia, is another amazing example of permafrost preservation.

In the last few decades, researchers have discovered scores of wooly mammoth remains from the tundra of Siberia and beyond. A 28,000-year-old mammoth named “Yuka” was discovered near the mouth of the Kondratievo River in Siberia in the summer of 2010. It is one of the most famous and studied examples. Scientists have even considered harnessing the DNA of permafrost-preserved mammoths and utilizing it to resuscitate the species from extinction, despite the fact that there is still a long way to go.

11 notes

·

View notes