#lobopodia

Text

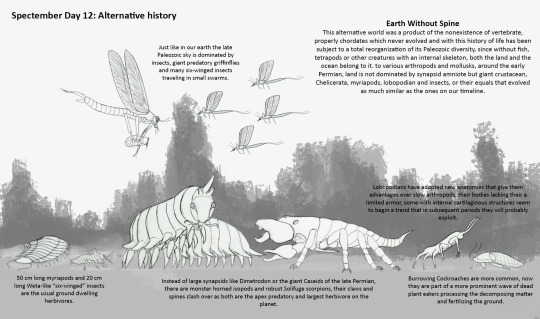

Spectember D12: Alternative history

The early Permian of this alternative timeline physically looks almost the same, same geography, same flora, same events of mass extinction, but there is a considerable difference that is remarkable when one checks on the fauna, there are arthropods wandering around, of different sizes, of different shapes, alongside them there are other strange velvet worm like forms, some large mollusks, but what we could recognize nowhere to be found; in the rivers, there are more arthropods and mollusks, and even some large worms, but not bony fishes, sharks or anything that resemble a vertebrate, this world have never seen vertebrates ever.

Something happened through the beginning of the Paleozoic that caused to vertebrates to never evolve, leaving a gap in history that only other animals would fill on their ways.

Moving towards the Silurian and Devonian started to show the consequences of this change as without any type of fish, shark, placoderm, anything that we could relate to the the early paleozoic vertebrate diversification did not happen and the result of such vacuum was the diversity of arthropods and mollusks, some larger species of marine arthropods/panarthropods evolved, some larger mollusks did evolve too, cephalopods and gastropods became predominant where large marine vertebrates should dominate, and in the coasts the trend of arthropod conquest was ongoing as on our world, evolving convergently things like insects, myriapods and arachnids, alongside many other terrestrial crustacean species.

The carboniferous had a different face on land now that since there were not tetrapods taking over and with arthropods like insects and arachnids evolving similarly to our world species, they were fully conquering the planet with diverse and large sized forms, from the early carboniferous to the cooler late period, insects were dominant in numbers on land and the sky, myriapods were the usual predominant herbivores, and arachnids took over predatory roles, being scorpions the apex predators, secondarily were with them some isopod like forms, more packed and suited for dry land so they could extend off the humid forest regions, as well velvet worms which started to be more prominent in some minor parts of the ecosystem.

Up to the early Permian with the desertification of the landscape and loss of environment have pushed the most adaptable species on changing to face the new life conditions, many of the gigantic forms remained, new ecological trends started to appear within some groups, and so this spineless version of the Permian is full of a new cast of arthropods.

The north america of the Early Permian is a land dominated by 50 cm long Solifuge-like scorpions that have evolved with robust chelicerae, more used to large prey they are the apex predators on land, meanwhile in the sky 40 cm of wingspan robust griffin fly predators have evolved, more heavier lethal than any other odonatan, herbivorous palaeodictyopterans still swarm around as well; on the ground is different types of omnivorous and herbivores arthropods going along, there are Arthropleura-like myriapods, but along them some other arthropod herbivores have developed more chubby and taller, these isopod-like armored forms are as big as 1 m, they are close or even heavier than any of the flat Myriapoda; smaller herbivores surround them along, such as 20 cm long flightless cockroaches and Weta-like Palaeodictyopterans are common small herbivores; lobopodians grew up to 30 cm in length, gracile and are among the most agile terrestrial animals on land, sort of evolving a complex inner cartilage skeleton, might become the blueprint of a new future group that will take over in the next periods.

#speculative evolution#alternative evolution#arthropod#paleozoic#permian#insects#myriapods#velvet worm#lobopodia#arachnids

99 notes

·

View notes

Text

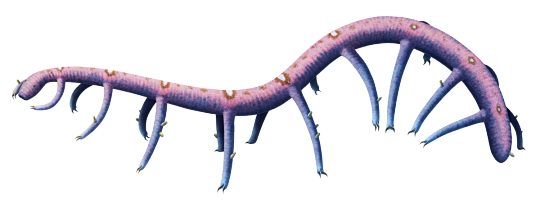

Lobopodians were some of the earliest known panarthropods, closely related to velvet worms, tardigrades, and the ancestors of all the true arthropods. They were small soft-bodied worm-like animals with multiple pairs of fleshy legs, and some species also bore elaborate spikes, armor plates, and fleshy bumps all over their bodies – with the spiny Hallucigenia being the most famous example.

But unlike its more charismatic relative Paucipodia inermis here didn't seem to have any ornamentation at all.

Known from the Chinese Chengjiang fossil deposits, dating to about 518 million years ago, Paucipodia lived in what was then a shallow tropical sea. Its 13cm long (~5") tubular body had nine pairs of legs, with each foot tipped with a pair of hooked claws, and the inside of its mouth was ringed with tiny sharp teeth.

Several specimens have been found preserved in association with the weird gummy-disc animal Eldonia, which may indicate Paucipodia either preyed on them or scavenged on their carcasses.

Some Paucipodia fossils also have enigmatic tiny "cup-like" organisms attached to their legs. It's currently unknown what exactly these were, or whether they were parasitic in nature or simply opportunistically "hitching a ride" similar to the Inquicus found on armored palaeoscolecid worms in the same fossil beds.

———

NixIllustration.com | Tumblr | Twitter | Patreon

#science illustration#paleontology#paleoart#palaeoblr#paucipodia#lobopodia#panarthropoda#arthropod#invertebrate#cambrian explosion#parasitism#symbiosis#oh worm

389 notes

·

View notes

Text

Cambrian Dashboard Simulator: obscure lads!

🥔 nonvermiform

Does anyone else here enjoy some nice silt every now and again?

🫂 embracingbeast Follow

literally nobody cares about you and your fellow mud-eaters, Saccorhytus

swedish_cyclopsdeactivated1003065012

I’ll have you know that anti-meiofaunal speech like that is incredibly nicheist. What’s he supposed to do about it, suddenly grow to as big as an Isoxys?

🦞 shrimp_from_oland Follow

I second that. As a fellow sediment-feeder myself, I can confirm swedish_cyclops’s views are true.

🗡️ laminatedlad Follow

bro wtf are you gonna do you’re like 1 mm long

48,194 notes

🔦 alightinthedark

🪛 chaetognatha_stem Follow

Me obviously, I eat isoxyids for breakfast. I’m also twice the size of @proclamation_claw.

🦂 omnidens_worshipper

You do realise your phylum is dying out, right? Plus, I’m bigger than you and don’t even bother with the isoxyids.

21,947 notes

🪳just_mosiing_along

me when I have the entirety of the beach to myself

🐟fishfromhaikou Follow

you’re lucky to have such a good life. i have to worry about radiodonts eating me or getting washed up on the shore and left to people like you

3,710 notes

🌲petalonamae_fan Follow

bro what happened in the last 40 million years I swear the Ediacaran was yesterday

🌊 beforejawswerecool

did you accidentally settle onto those paucipodia brownies @incertae_sedis made?

because I don’t think 40 million years of memory loss is normal.

🪶 wonderfulfeather Follow

t h e y t o l d m e a p r o p h e c y

8,158 notes

🥕not_a_spiralian Follow

reblog if you hate lobopodians

278 notes

🪸 the_king_omnidens

hey

#lobopodia #pambdeluriidae #maotianshan reef

291,481 notes

👻 phantomofruinwash

it feels nice to finally be described as Mobulavermis adustus. I’ve also finally gotten a fossil with a preserved head!

🦀shu’s_shrimp Follow

speak for yourself. i’ve barely been mentioned in the literature and only have an abstract available.

🇷🇺 kuonamka_tardigrade

you guys have scientific names?

#kuonamkaformation #tardigrade

1,974 notes

🧢meio_beret

hey @nonvermiform, how are you doing? it’s always nice to see you again with no company on the Yanjiahe seafloor but the weird stalked things.

🥔 nonvermiform

Doing alright. Although there were some radiodonts that tried to get a sifter to eat me.

🐋romip65415 Follow

still gonna eat you, @nonvermiform

28,193 notes

(this is for you @ravewing)

#cambrian#anomalocaris#mobulavermis#lobopodia#radiodont#chaetognatha#anomalopost#dashboard simulator

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

Glitterback (Artwork by https://www.deviantart.com/yuujinner)

Kingdom: Animalia

Phylum: "Lobopodia"

Class: "Xenusia"

Order: Xenaraneae

Family: Pterorhomidae

Genus: Pterorhomos

Species: P. polydens (“many-toothed flying woodworm”)

Temporal range: Pliocene to recent (4.333 mya - present)

Information:

Soaring through the dense undergrowth of Xenogaea’s rainforests, the Glitterback, also known by its native Xenogaean name as babunakiri (from babuna [“spider”, “tarantula”, “thing with fangs”] and kiri [“bat”, from a corruption of hakiryt, which literally means “mammal-bird” {haki, “mammal”, “thing with fur”, and ryt, “bird”}], hence having a combined meaning of “spider bat”), is as iconic to the Pacific island nation as it is bizarre. Though it looks like some sort of alien creature in comparison to most other animals living on Earth, the Glitterback is actually a large (roughly the size of a golden eagle), air-breathing, arboreal lobopod which has developed the ability to glide over long distances. Its jaws, not unlike those of a camel spider, are designed to rip and tear through its preferred prey: small birds and bird-like ornithurans living in the jungle canopy. While these animals make up some 70% of its diet, it will also go after arboreal dromaeosaurs, small primates, plesiadapiforms, arboreal therapsids (such as the venyukovioids), small pterosaurs, bats, snakes, and other arboreal reptiles, in addition to arboreal amphibians and amphibian-grade tetrapods, such as reptiliomorphs belonging to the family Dendrosauropidae. Like the avians which it primarily hunts, its sense of smell is rather poor, instead relying on its large, chameleon-like eyes to locate prey in the dense undergrowth. Its eyes are, in fact, some of the best in the panarthropoda clade, rivaled only by those of dragonflies. Its eyes can not only see in UV light, but also fast motion which would otherwise look like a frenzied blur to other organisms. In several tests, Glitterbacks were also shown to be quite adept at distinguishing between subtle color differences. These traits not only help them to spot birds ducking through the canopy, but to also better pinpoint their target’s location for when they go in for the kill. Anecdotally, Glitterbacks appear to have a symbiotic relationship with some of the sauropods found living in their native range, often using the large animals to hitch rides to new hunting locations in exchange for hunting small, hematophagous pterosaurs which often plague the sauropods.

In color, Glitterback tends to be a mottled green color with light blue spots on their backs (hence their name), though other color morphs also exist, including all-black with light blue dorsal spots, red with orange dorsal spots, light blue on the underside with green on top and brown dorsal spots, and, in very rare occasions, vibrant purple with red spots (though these individuals rarely live long in the wild since their coloration makes them easy to spot). Glitterbacks are quite vocal animals, emitting a wide range of calls from clicking to pulsating, guttural drumming to loud shrieking. These sounds are primarily used to convey location to other members of their species so as to establish their hunting territory. Glitterbacks are primarily crepuscular and nocturnal animals, hunting in low light levels and in an environment filled with potential obstacles in their path.

While commonly recognized as belonging a monospecific genus (i.e., it is the only known living member of its genus), studies on its genetics and morphology have revealed that the Glitterback may, in fact, constitute a species complex, with anywhere from 3-8 distinct species, of which at least one is usually considered distinct enough from the rest to be placed in a separate proposed genus, Babunakiriia.

Glitterbacks are notable for their longevity: in the wild, they may live up to 15 years, and in captivity, up to 25. Bizarrely, for an arboreal species, their life actually starts all the way at the forest floor, where the small (only slightly larger than a grain of rice), pearl-like eggs are laid in a small hole in the ground before being promptly buried. Once the eggs hatch after 3 weeks, the young, who resemble tiny, white insect larvae, will spend the next 2 years on the forest floor and in the soil hunting small invertebrates, such as worms and insects. The larvae, at this point, have underdeveloped eyes and no wing membrane between their front 3 pairs of limbs. Once they reach 2 years in age, they bury themselves in the soil and form a thin, elastic cocoon around themselves, emerging as their adult forms in the spring of the following year and making an exodus up the nearest tree to the jungle canopy. While the now 3-year-old Glitterbacks may have their adult forms, they will only begin to reach reproductive age at around 5 years old, when they receive their distinctive dorsal markings. Of the some 100,000 eggs the female lays, as few as just 10 may reach reproductive age, and siblings are not above cannibalism to erase the competition for resources. Once they reach sexual maturity, the female will emit a call which is often likened to a high-pitched rattling (which is made from grinding her chelicerae together rapidly) to significantly to males that she is ready to mate. However, she won’t mate with just anyone: males must present her with a fresh kill, and the more vibrant the prey, the better the male’s chance of her being sexually receptive. Copulation occurs while she feasts on the kill, and afterwards, the male departs back to his own region of the forest, not wanting to risk incurring the territorial wrath of another Glitterback. The fertilized eggs will be deposited on the ground in a few weeks time, and in another two years, she will be ready to mate again, a cycle which repeats up until her death.

Despite their territorial and aggressive nature, Glitterbacks tend to be either timid or inquisitive around humans, and outside of a few unconfirmed reports of attacks on small children in Xenogaea’s countryside, some of which were supposedly fatal, aggression towards humans is all but unheard of. However, being opportunistic feeders, a lone Glitterback which has found itself on the ground may, like many of Xenogaea’s other macropredators, occasionally resort to scavenging the graves of the recently deceased, a practice which has seen many tribal folks placing large slabs over the coffins of the deceased, digging the graves deeper, or exclusively cremating their dead in large funeral pyres.

While Glitterbacks are listed as a Least Concern species, poaching and the illegal pet trade are often listed as threats to their survival, with their ownership as pets being particularly popular in parts of many South American, Sub-Saharan African, and Southeast Asian countries because of their hunting prowess making them invaluable aids in fowling and their adaptations to living in a tropical climate making them well-suited to the environment and with navigating the dense jungle in pursuit of otherwise difficult-to-catch prey. However, as with many of the other indigenous lifeforms of Xenogaea, its export out of the country is highly restricted, with dead specimens being sold to museums for large sums of money, sometimes well in the millions of local currency, and live specimens only rarely being sold to biological research institutions. This has not only led to the black market sale of live specimens being highly valuable, but it has also led to underground breeding facilities overseas becoming a prevalent way to circumvent local laws against the trafficking of exotic animals. This issue of the black market sale of native wildlife is so deeply-entrenched within Xenogaea’s system, that the country’s government has a subdivision, the Bureau of Indigenous Wildlife Protection and Action Against Poaching (BIWPAAP), which is dedicated entirely to stopping poaching and illegal animal trafficking within the country and notifying the local authorities of other countries about the illegal sale and breeding of Xenogaean wildlife within their borders. If caught illegally selling a Glitterback in Xenogaea, the legal repercussions can range from anywhere from 4 years in prison and a $100,00 fine to 20 years in prison and as much as $1,000,000 in fines. It should be noted, however, that while the sale of a Glitterback, whether within the country’s borders and to a buyer outside of them, is illegal, the ownership of one in the country is not, and some native tribes may raise Glitterbacks for hunting purposes, much like buyers outside of the country.

#speculative evolution#scifi#fantasy#novella#speculative biology#speculative fiction#speculative zoology#worldbuilding#scififantasy#sci fi creature#fantasy creature#creature design#creature art#creative writing#creature#lobopodia#panarthropoda

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Orstenotubulus

Orstenotubulus — рід лобопод, відомий з орстенських відкладів пізнього “середнього” кембрію (міолінгу) Швеції. Дехто вважає, що він є предком тихоходів (Tardigrada).

Повний текст на сайті "Вимерлий світ":

https://extinctworld.in.ua/orstenotubulus/

#orstenotubulus#cambrian#lobopodia#sweden#cambrian period#tardigrada#paleontology#paleoart#prehistoric#animals#digital art#illustration#extinct#article#sciart#art#палеоарт#палеонтологія#ukraine#ukrainian#тварини#швеція#україна#мова#українська мова#арт#наука#prehistory#science#image

16 notes

·

View notes

Note

26, 39, 49, 62, 86?

26. how many pillows do you sleep with?

just the one big one

39. do you have a nickname? what is it?

I don't have one irl

49. what was the last compliment you received?

62. do you still watch cartoons?

Not really. I wasn't a fan of them as a kid either. Mostly too american. I don't mind watching children's shows though, if they're good, like Star Trek Prodigy.

86. what is your phone background?

A nebula that moves around when I move my phone :))

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

There's something about velvet worms that just speaks to me on a fundamental level. I won't even elaborate, just look at them!

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

i love lobopods and their two little black beady eyes and their stupid little noodle grabby legs. if they where alive today they would be the most pathetic sopping wet animals currently existing on the planet

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

En Eski Beyin Fosili

En Eski Beyin Fosili

Çin’de keşfedilen 525 milyon yıllık fosil, günümüze kadar keşfedilmiş en eski beyin örneğine sahip. Bilim insanlarının şaşırtıcı şaşırtıcı olarak belirtiği beyin şekli, böcekler, araknidler ve kabukluları içeren bir grup olan eklembacaklıların evrimi hakkında çok fazla bilgi sunuyor.

En Eski Beyin Fosili

Cardiodictyon catenulatum olarak isimlendirilen bu tür, 1984’te Çin’de…

View On WordPress

#Beyin Fosil#Cardiodictyon#Cardiodictyon catenulatum#catenulatum#eklembacaklar#en eski#En Eski Beyin Fosili#kambriyen#Lobopodia

0 notes

Text

Locomotor Organelles in Protozoa

There are 4 types of locomotor organelles in protozoa: Pseudopodia, Flagella, Cilia, and Pellicular Contractile Structures.

Pseudopodia: False feet that temporarily form and extend with the flow of cytoplasm. There are 4 subtypes: Lobopodia, Filopodia, Reticulopodia, and Axopodia.

Lobopodia are lobe-like and have broad rounded ends. They're made up of both the cells ectoplasm and endoplasm. Seen in Amoeba.

Filopodia are filamentous, they taper from the base of the cell to the pointed tip. They're only made up of ectoplasm. May branch to form simple or complex networks. Seen in Euglypha

Reticulopodia are also filamentous. The filaments branch profusely and interconnect to form a network. They display a two-way flow of cytoplasm. Seen in Globigerina.

Axopodia are straight pseudopodia radiating from the surface of the body. Each axopodia has a central axis rod enclosed in cytoplasm. Also exhibits a two-way flow of cytoplasm. Seen in Actinophrys.

Flagella: Thread like projections on the surface of the cell. Each flagellum has an elongate, stiff axial filament, called an axoneme, enclosed in an outer sheath. In mastigophoran protozoa, there are flagellar appendages called mastigonemes which extend laterally from the outer sheath. Seen in Euglena.

Cilia: Resemble flagella in structure but are much smaller. They are highly vibratile small ectoplasmic processes, they move in a spiral manor. Seen in Pleuronema

Pellicular Contractile Structures: Many protozoans have contractile structures called myonemes. They may be in the form of ridges, grooves, contractile myofibrils, or microtubules. They exhibit metabolic movement though gliding and wriggling. Seen in Euglena.

0 notes

Photo

Retro vs Modern #09: Hallucigenia sparsa

If just one single species had to represent how our reconstructions of prehistoric animals can drastically change, it would have to be Hallucigenia sparsa.

1970s

First discovered in the 1910s in the Canadian Burgess Shale fossil deposits, specimens of Hallucigenia were initially categorized as being a species of the early polychaete worm Canadia. It wasn't until the 1970s that they were recognized as being something else entirely, and the first reconstruction of this tiny animal was bizarre.

It was depicted as a long-bodied creature with a single row of tentacles along its back, and several pairs of long sharp spines that were interpreted as being stilt-like "legs" used to walk. The tentacles were thought to catch food from the water and pass it forwards to the bulbous "head" – and at one point it was even proposed that all the tentacles had their own additional "mouths" at their tips!

It's easy to look back on this version now and laugh at how ridiculous and obviously wrong it was, but it's important to remember the historical context here. This was coming from a point when the incredible animal diversity of the Cambrian Explosion was only just starting to be understood, revealing a range of poorly-understood bizarre and alien-looking forms like Opabinia – "weird wonders" that were considered to be representatives of previously unknown ancient branches of life.

At the time, Hallucigenia's utter weirdness and impractical body plan seemed to almost make sense as a unique evolutionary "failed experiment" that had left no living relatives.

1990s

Discoveries of legged-and-armored lobopodian "worms" in the Chinese Chengjiang fossil deposits during the 1980s prompted a re-interpretation of Hallucigenia in the early 1990s. Speculatively reconstructing it as a lobopodian with the spines on its back and with the tentacles as a set of paired clawed legs started to make it seem a lot less alien and a lot more like a real velvet-worm-like animal – and just a year later the "missing" other half of the leg pairs was confirmed to be present in some of the fossil specimens.

But it was still unclear which end was actually the head, and whether the large blob-like structure was a real part of Hallucigenia's anatomy or just an artifact of the fossilization process.

2020s

New research in the mid-2010s finally settled the head problem and clarified a lot of Hallugicenia's anatomy, discovering that the slender elongated end had a pair of simple eyes and a mouth with a throat ringed with tiny teeth.

We now know Hallucigenia sparsa lived all around the world during the mid-Cambrian, about 518-508 million years ago, with body fossils known from Canada and China and isolated spines found in numerous other similarly-aged locations. Instead of an evolutionary dead-end "weird wonder" it was actually an early member of the vast arthropod lineage, just one of a highly diverse collection of successful Cambrian lobopodians, and its closest living relatives are probably velvet worms and tardigrades.

It grew up to about 5cm long (2") and had seven pairs of long sharp defensive spines along its back, covered with a microscopic surface texture of tiny triangular "scales". It had seven pairs of clawed walking legs, with most of its feet tipped with two claws each but the final two pairs having just one, and its body ended right at the final pair of limbs – the "blob" structure in some fossils was actually just an artifact the whole time, formed by Halligenia's innards being forcefully squeezed out during its burial in the seafloor sediment.

Its neck region bore three pairs of long delicate tendril-like limbs, which may have been covered in feathery hair-like structures for filter-feeding similar to some other lobopodians. A small pair of velvet-worm-like antennae may also have been present on its head, and could have been a sexually dimorphic feature.

———

Nix Illustration | Tumblr | Twitter | Patreon

#retro vs modern 2022#science illustration#paleontology#paleoart#palaeoblr#hallucigenia#hallucigeniidae#lobopodia#panarthropod#art#hallucigenia my noodly beloved

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

check out this worm

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

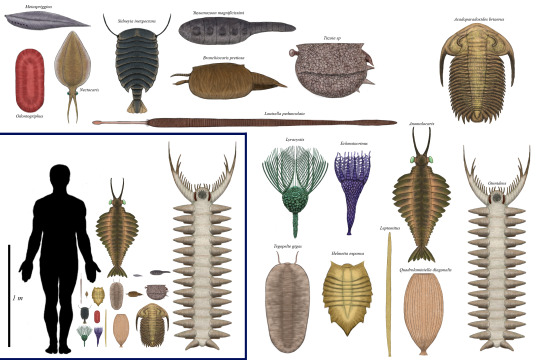

As many know well the Cambrian is the beginning of our world’s biodiversity, is an advance follow up of the ediacaran flourish of life under the ocean, the major period of life diversification with the explosion and rise of the many major clades of animals that would establish for the next 500 million years, such as mollusks, annelids, arthropods, chordates, etc. as well alongside them some other very bizarre clades that arose and at the same time perished in that span which couldn’t leave any descendant after. The marine life grew up and became more from the pacific sessile or slow filter feeders or detritivorous ediacarans stuck in the sand, radiating into a crazy mosaic of different creatures nothing like anything that appeared before and establishing the bases for the dominant clades today, with different shapes, number of legs, numbers and shape of eyes, segments, and most important… in different sizes, mostly small, but some larger than the average…

For this chart I wanted to do something more than just pick the few largest animals of period which excess the meter long (which could have been just 2 specie), so I tried to see specimen size from all other clades known from the period, giving more variety of what some of the biggest animals were, even if they weren’t gigantic like most of actual fauna, of course with this I have to be a bit selective as not many clades really became enough large, at least in this chart the species I will expose are larger than 10 cm and noticeable enough, so even the largest animals of some clades here will be out for being very, very small…

The world in this point was pretty much the world of the Panarthropods, the major clade that includes all known Arthropoda and stem-arthropod, and there is no doubt that the Lobopodians were one of the major faunistic Panarthropods in many pelagic and benthonic niches, becoming some species iconic for its many bizarre forms and some others for their extraordinary sized, specially the Anomalocarids such as the iconic genus Anomalocaris with known specimens reaching lengths of around 60 cm to a meter long making it one of the biggest predators of the ocean at the period and being the first apex predator of history; there is also a tentative competitor for the position as the biggest lobopodians, as well the biggest animal of the period, the species Omnidens amplus (originally classified as a worm), only know by a preserved set of mouthparts, which scaled up with some relatives like the benthonic dweller Pambdelurion gives a size estimation of 1.5 to 2 meters long, but for the lack of a complete body makes difficult a properly size estimation.

Alongside the Lobopodians were also the myriad species of Arthropods, most of them were in the genesis of the clades that could come up millions of years after, just like Crustaceans, Chelicerata or Mandibulata, but in this point on time these weren’t yet a thing like they would be in next periods, instead the diversity of these was formed by other clades, specially a lot of stem-group outside euarthropods and still unknown to link clades as well others euarthropods unrelated to the major clades mentioned first; the pelagic Tuzoiid Tuzoia sp. was able to reach 18 cm long, the benthonic Sidneyia inexpectans with specimens reaching up 16 cm long and the genus Branchiocaris pretiosa which reached up sizes around 15 cm long, not giants but still pretty large among their groups.

The Trilobites are one if not the major clade of arthropods for excellence during the Paleozoic, with different variety of species, being the Cambrian the pinnacle of its population clades with more than 60 families, most of these were around the lengths of less than 10 cm and often were the prey of bigger animals, but in some others places they were able to reach a very extraordinary size, being one of the biggest species known the redlichiide Acadoparadoxides briaerus from morocco, with specimens reaching up 45 cm long. Apart of trilobites, there were some other relatives which belongs to a major clade known as “Trilobitomorpha” which resemble them in certain anatomical features, but they weren’t true trilobites, such as the Helmetiid Helmetia expansa, a very large soft-bodied looking arthropod of around 27 cm long is one of the largest non-anomalocarids arthropods of burgers shell, and the Tegopeltidae Tegopelte gigas with a size of 19 cm.

The Archaeopriapulida (stem-priapulids) were other of the predatory benthonic animals of the Cambrian landscape, pretty much found burrowing in the sand and mud and protruding from their places, exposing a large proboscis they were mostly ambush hunters. The most well known is probably Ottoia for the common of its specimens, but these often doesn’t pass the length of 8 to 15 cm, but others were bigger that this one, a good example is the species Louisella pedunculata, which the largest specimen reached a size of 30 cm long with the proboscis extended.

One odd group among the Cambrian biota was the Vetulicolians, an enigmatic clade probably related to deuterostomes. These were weird arthropod-looking creatures that shown adaptations for pelagic lifestyle and mostly being filter feeders, many of these tended to be average lengths less than 10 cm, but Yuyuanozoon magnificissimi from comes to be the largest species known, with a length of 20.2 cm

The Chordates diversity during the Cambrian was formed by a small group of vermin agnatha forms, mostly swimming filter feeding of small size of few centimeters, the largest of these was Metaspriggina with specimens reaching up to 10 cm long which wasn’t that large size compared to many Cambrian lifeforms, was still an outstanding length compared to other of the chordates of the period.

Echinoderms were in their early genesis of its diversification with some unique morphology, so bizarre and alien compared to our actual species, as well there were others similar or very close in many aspect to actual ones, although most were very minuscule, some of the few macroscopic forms included, Lyracystis which is the largest eocrinoid with specimens reaching up sizes to 21 cm tall being half of it the arms.

Lophotrochozoa flourished during this period, evolving into the important clades including the very common brachiopods, the basic annelids and the Mollusks, although there were some species that could be classified as the last ancestors or stem-relatives of such clades, they don’t belong to these clades but they are coming to the roots of these, including Odontogriphus which specimens were able to reach up sizes around 12 cm long. Mollusks started their slow path into diversification with early small shelled varieties, most of them minuscule and don’t reaching up few centimeters of length, although few reached some considerable size for the average, such as the pelagic Nectocaris pteryx, the enigmatic cephalopod-like mollusk (?) with specimens reaching up sizes of 7 cm long.

Cnidaria are among the oldest animals on earth which during the cambrian expanded though the warm oceans either as jellyfish or small coral-like forms that could spread in the next periods, among some of these early species there was Echmatocrinus which is a pretty robust form with a height of 18 cm tall.

Sponges were one of the major reef builders of the Cambrian, forming alongside other sessile lifeforms extensive biomes which thrived in the warm swallow oceans. Some of the biggest sponges found so far belong to the species Quadrolaminiella diagonalis which were barrel shaped sponge from the Chengjiang Fauna, with a height of 20 cm and a diameter of around 12 cm. Another species was Leptomitus, a very tall but thin kind of sponge from Burgers Shale, with specimens reaching up heights around 36.4 cm, but with a diameter less than a centimeter long.

A minor stuff worth to mention, other of the bizarre benthonic reef builders that dominated the Cambrian seabed were the archaeocyathids, a group formed by small conical shaped forms with some brachiating forms, similar in many ways to sponges except in inner structure, some of these often reached sizes of around 9 to 10 cm tall and some centimeters in diameter, but according to some mentions in websites and papers some were able to reach up even very larger sizes, with giant specimens reaching around 60 cm, but I wasn’t able upon this date to locate these very big forms so I couldn’t add them (either these are exaggerated estimations from fragmentary individuals or actually those were hinted from other fossil sponges)

References

-Briggs, D. E. (1972). Anomalocaris, the largest known Cambrian arthropod. Palaeontology, 22(3), 631-664.

-Vinther, J., Porras, L., Young, F. J., Budd, G. E., & Edgecombe, G. D. (2016). The mouth apparatus of the Cambrian gilled lobopodian Pambdelurion whittingtoni. Palaeontology, 59(6), 841-849.

- Xianguang, H., Bergström, J., & Jie, Y. (2006). Distinguishing anomalocaridids from arthropods and priapulids. Geological Journal, 41(3‐4), 259-269.

-Whittington, H. B. (1985). Tegopelte gigas, a second soft-bodied trilobite from the Burgess Shale, Middle Cambrian, British Columbia. Journal of Paleontology, 1251-1274.

-Bruton, D. L. (1981). The arthropod Sidneyia inexpectans, Middle Cambrian, Burgess Shale, British Columbia. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. B, Biological Sciences, 295(1079), 619-653.

-Vannier, J., Caron, J. B., Yuan, J. L., Briggs, D. E., Collins, D., Zhao, Y. L., & Zhu, M. Y. (2007). Tuzoia: morphology and lifestyle of a large bivalved arthropod of the Cambrian seas. Journal of Paleontology, 81(3), 445-471.

- Rudkin, D. M., Young, G. A., Elias, R. J., & Dobrzanski, E. P. (2003). The world's biggest trilobite—Isotelus rex new species from the Upper Ordovician of northern Manitoba, Canada. Journal of Paleontology, 77(1), 99-112.

- Daley, A. C., Antcliffe, J. B., Drage, H. B., & Pates, S. (2018). Early fossil record of Euarthropoda and the Cambrian Explosion. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 115(21), 5323-5331.

- Aria, C., & Caron, J.-B. (2017). Burgess Shale fossils illustrate the origin of the mandibulate body plan. Nature, 545(7652), 89–92.

-Walcott, C. D. (1911). Cambrian Geology and Paleontology II: No. 5--Middle Cambrian Annelids.

-Morris, S. C., & Caron, J. B. (2014). A primitive fish from the Cambrian of North America. Nature, 512(7515), 419.

-Sprinkle, J., & Collins, D. (2006). New eocrinoids from the Burgess Shale, southern British Columbia, Canada, and the Spence Shale, northern Utah, USA. Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences, 43(3), 303-322.

- Sprinkle, J., & Collins, D. (1998). Revision of Echmatocrinus from the middle cambrian burgess shale of British Columbia. Lethaia, 31(4), 269-282.

- Caron, J. B., Scheltema, A., Schander, C., & Rudkin, D. (2006). A soft-bodied mollusc with radula from the Middle Cambrian Burgess Shale. Nature, 442(7099), 159.

- Walcott, C. D. (1917). Middle Cambrian Spongiae. Smithsonian Miscellaneous Collections.

- Legg, D. A., Sutton, M. D., & Edgecombe, G. D. (2013). Arthropod fossil data increase congruence of morphological and molecular phylogenies. Nature communications, 4, 2485.

- Wu, W., Zhu, M., & Steiner, M. (2014). Composition and tiering of the Cambrian sponge communities. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology, 398, 86-96.

#Paleoart#paleontology#History Size Chart#Cambrian#Burgess Shale#Anomalocaris#Trilobite#Arthropoda#Echinoderms#Lobopodia

141 notes

·

View notes

Note

Top 5 Cambrian animals

1. Pikaia

2. Cloudinids

3. Paradoxides

4. Eocrinoidea

5. Lobopodia

But I have to point out that Chambered Nautilus’ are one of my favorite animals. I really want a stuffed animal of one I just haven’t looked yet.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Erratus

Erratus — вимерлий рід морських членистоногих з кембрійського періоду Китаю. Типовий і єдиний відомий вид — Erratus sperare. Erratus займає перехідне положення між лобоподами (Lobopodia) та справжніми членистоногими, а його відкриття допомогло вченим зрозуміти ранню еволюцію ключових характеристик членистоногих. Деякі з найстаріших стовбурових членистоногих, таких як Anomalocaris, не мали ніг, натомість у них були придатки,…

Повний текст на сайті "Вимерлий світ":

https://extinctworld.in.ua/erratus/

#erratus#cambrian#china#erratus sperare#arthropoda#lobopodia#paleontology#paleoart#extinct animals#палеонтологія#палеоарт#вимерлі тварини#доісторичні тварини#ukraine#ukrainian#prehistoric#made in ukraine#animals#nature#scientific illustration#art#science#history#український tumblr#україна#українська мова#наука#український тамблер#creatures#prehistory

6 notes

·

View notes