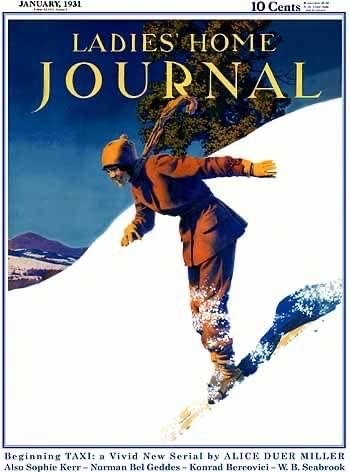

#ladies home journal

Photo

From Ladies’ Home Journal magazine - October 1927.

#ladies home journal#womans fashion#vintage illustration#vintage clothing#fashion#vintage advertising#the 20s#the roaring twenties#1927

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

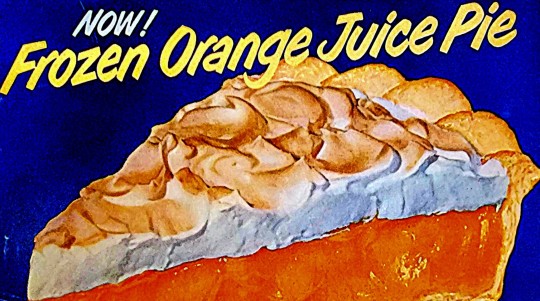

From our picture files: Ladies' Home Journal July, 1950

#now! frozen orange juice pie#pie#pi day#ladies home journal#1950#orange juice#1950s#vintage#vintage advertising#now!#oj#pies#orange juice pie#detroit public library

110 notes

·

View notes

Text

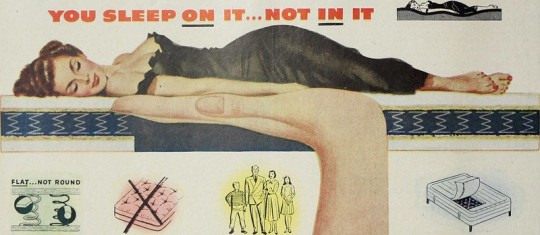

Ladies Home Journal 1952

101 notes

·

View notes

Text

John La Gatta (John LaGatta), "Doesn't the groom kiss the bridesmade" Alan asked. He took a step forward. Mimi smiled, something glimmered between her lashes. Their lips met. Ladies Home Journal, 1930s.

#John La Gatta#John LaGatta#1930s#ladies home journal#illustration#painted illustration#fashion illustration#big hats#evening dresses#30s fashion#1930s fashion#short story illustration#1930s illustrations#30s romance#30s magazines#iris#bridesmaids#groom#wedding#bridal#wedding dress#bridesmaid dress#bridesmaid kiss#bridal story

57 notes

·

View notes

Text

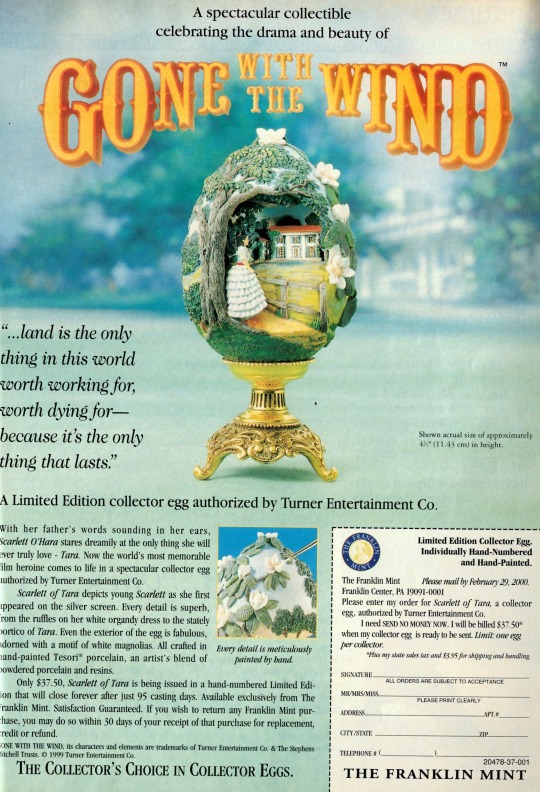

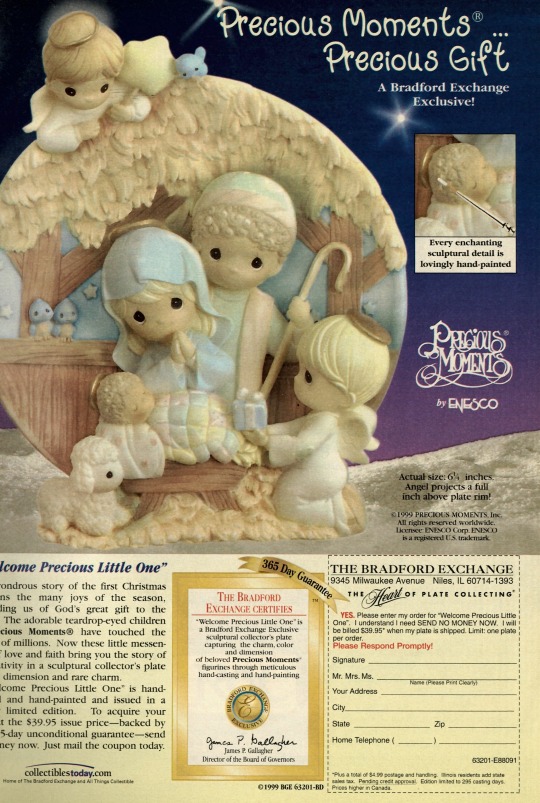

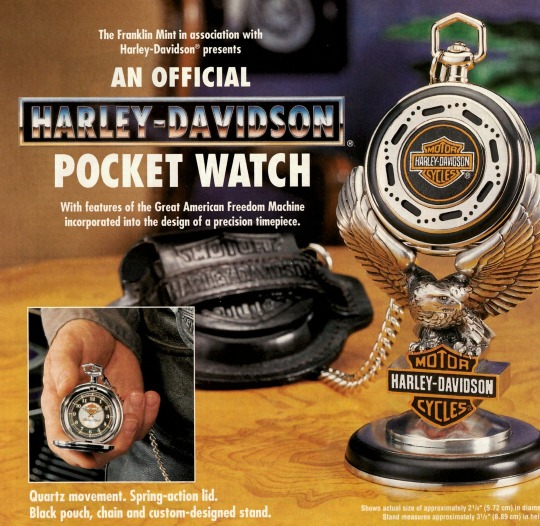

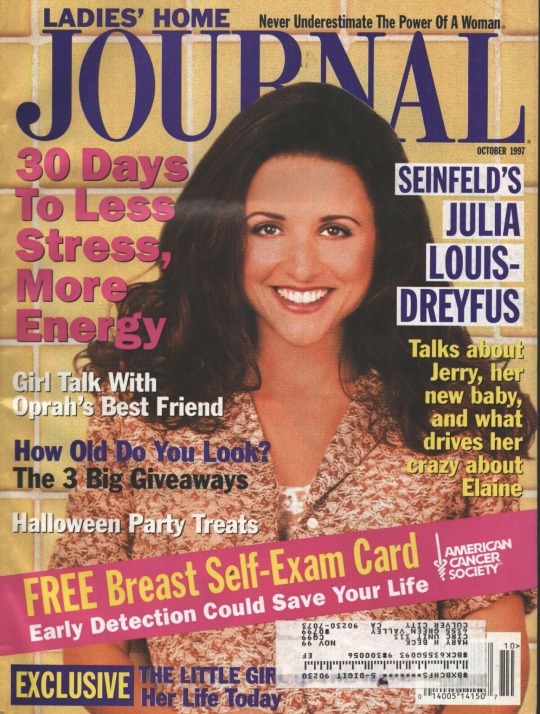

Assorted ads from Ladies' Home Journal, February 2000

#nostalgia#but like. nostalgia for your parents' things if that makes any sense?#I have a lot of that (heavy on the Harley ad)#mine#original#90s#magazines#ladies home journal#nostalgic#print#harley davidson#precious moments#gone with the wind

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

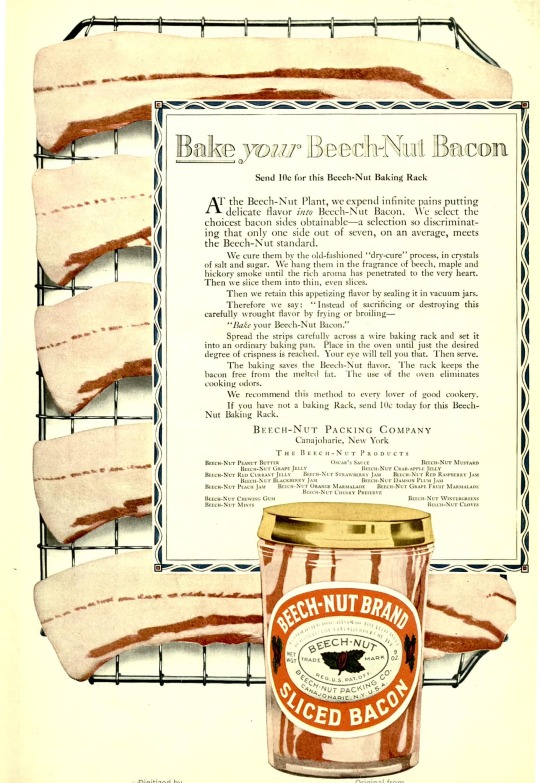

Advertisement, 1917. Found in, Ladies Home Journal.

#vintage#nostalgia#bacon#beech-nut brand#1917#ladies home journal#vintage ads#advertisement#vintage advertisement#vintage advertising

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

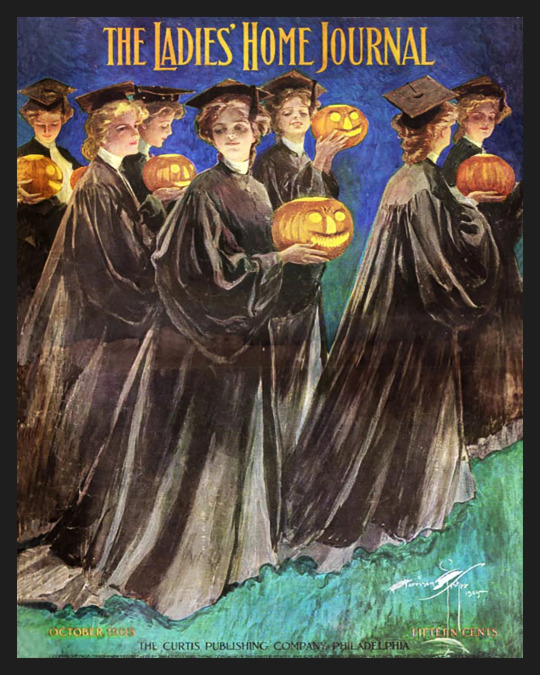

Ladies Home Journal 1905 Magazine Cover

#Halloween#Jack o lanterns#pumpkins#Halloween Costumes#Retro Halloween#Vintage Halloween#Ladies Home Journal#1905

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

lingerie advertisement, Heinz beans advertisement

Ladies Home Journal, May 1920

#vintage ads#vintage advertising#vintage advertisement#1920s#vintage magazine#magazine pages#ladies home journal#jazz age#roaring twenties#magazine ad#historical advertisements#paper ephemera

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Cover illustration. Ladies Home Journal magazine - April 1928.

#vintage illustration#vintage art#vintage magazines#the 1920s#magazine illustration#ladies home journal

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

She is ✨Everything✨

She is Housewife!

Created by Miranda Parkin, I have fallen in love with this character and had to put her on a magazine cover~

✨My Links

✨My Unhinged Blog

#Housewife#digital art#fan art#house wife#oc#original character#oc fanart#artist#ladies home journal#nostalgic#nostalgia#magazine cover#vintage magazine

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

"The House on a Back Street."

By Mary Abbott Hand, Ladies' Home Journal, 1885, transcribed by myself, 2024

The Skittles family lived in a tidy, little box of a house, on a back street in the city. But though small, it was as pretty and pleasant as possible. There was a little parlor, dear to Mrs. Skittles' mournful heart, where funeral wreaths and hair bouquets and a portrait or two hung in the shade and never a wanton sunbeam was allowed to disturb the colors of the carpet and upholstery.

Then, there was a bright sitting-room, where geraniums smiled and fuchsias swung their crimson bells and a canary sung from morning until night. An open fire vied with the bay window for cheerfulness. There was a low bookcase filled with pleasant volumes, a lounge heaped with gay pillows, easy chairs at tempting angles, an old organ that for sweetness far exceeded the smart, new piano in the dark parlor. In fact, that pleasant sitting-room contained a wide range of delights for a contented mind.

In front of the house, a blossoming linden perfumed the air in May; and, later, spread its broad green sunshades so that Mr. and Mrs. Skittles and their little girl could sit under the pleasant arbor it made. And then, the leaves were no sooner on than they began to fall and she must keep the broom wagging till December if she would have her door-steps tidy.

The kitchen windows looked out upon what Mr. Skittles called "the garden." With Mrs. Skittles it was only "a back yard," though a grape vine trailed its graceful leaves and hung its purple pendants right before her eyes. Beds of verbenas and pansies made rich mosaics beneath the windows and the boundary fence was all overhung with morning glories that made the place look like fairyland the moment the sun was up.

But it was the prospect beyond that spoiled the garden for Mrs. Skittles. This was the beautiful home and gardens of their landlord, Charles Meliss, Esq. His mansion fronted on Main Street, but the terraced garden with its fountain, its exotics, its velvet sward and rare shrubs, reached quite to the Skittles; morning glories.

Mr. Skittles rejoiced in his neighbor's possessions was thankful, every day of his life for the sight of so much freshness and beauty. But, to Mrs. Skittle, as she expressed it "was a constant aggravation." Fortunately, the Skittles' only child was like the father. She had, to be sure, the shell-pink complexion, the dimples, the lovely blue eyes and wavy golden hair that had won for Mrs. Skittles long ago the title of belle.

But all these external beauties were made radiant by a sunny disposition. No wonder strangers would turn their heads on the street to look at the charming girl. It was the great disappointment of Mrs. Skittles' life that her child was a girl. It had been her dream to have a boy--to name him Robert Dalrymple for her father. But the best she could do was to name the baby Roberta Dalrymple and insist on having her called by the second name. But of course it became shortened to "Dallie" by her father and playmates, but Mrs. Skittles always called the child Dalrymple. She was such a beauty that Mrs. Skittles was sure she would never live to grow up and was fond of quoting--"Death loves a shining mark."

Nevertheless Dalrymple weathered all the children's diseases and at sixteen was a specimen of perfect health. And now began another worry. Mrs. Skittles did not forget that at sixteen she had a lover and in two short years from that time was married. The idea of Dalrymple and a lover! That would be a drop too much for Mrs. Skittles. So the girl was restricted like a prisoner of war. She could not go to a prayer-meeting or a party unless her father was her escort. She was forbidden to associate with her boy school-mate--was not allowed to speak to a boy on the street, or to acknowledge the bow and lifted cap of the most innocent acquaintance.

Even Tom Butterfield, their next door neighbor, never but once ventured to say "How do you do, Dallie?" when Mrs. Skittles was with her. All the boys could get by way of recognition was a deeper tint of pink in the cheeks and a conscious drooping of the eye-lids when they met the pretty girl. To do Dalrymple justice, she was as dutiful as she was modest and earnestly meant to please her fretful mother, whom she loved in spite of everything.

Dalrymple was untold comfort to both parents,--a perfect sunbeam in the home,--a model scholar, excelling in all her studies, particularly in mathematics, and by the time she was fifteen, the entire business of family accounts, marketing, settling of rent, etc., was entrusted to her. The landlord, young Squire Meliss always collected his own rents, and Mrs. Skittles had formerly met him herself, but, she declared, nothing so stirred her up as to meet that man who had everything in the world below, while she--

"But, mother!" interposed Mr. Skittles, using the name that reconciled him to his lot more than any other he could call his wife. "Just think, he is a love-lorn bachelor, and nobody to speak to in all that great house but servants. I wouldn't give our Dallie for all he is worth."

"He isn't an old bachelor," replied Mrs. Skittles. "Not over twenty-eight I am sure. Plenty of time yet for him to put the fine name of Mellis alongside some Smith or Murphy he may wish he hadn't. Moreover, it's because we have got Dalrymple that we ought to have the riches. That man has no use for half he owns. It fairly aggravates me, the very sight of him."

And so it came to pass that the unpleasant duty of paying the rent money devolved finally upon Dalrymple. If it were a trying thing for her, she never complained, but always answered promptly the ring announcing Mr. Mellis' call the first Saturday in each month, and returned from the brief interview with no other sign of disturbance than the heightened color in her cheeks.

Surely, there was never a more agreeable landlord than Mr. Mellis. He was as courteous as he was fine looking, and he was quite as neighborly as Mrs. Skittles would permit. As it was, many choice baskets of fruits or early vegetables found their way over the morning glories with "Mr. Mellis' compliments for Mrs. Skittles." The lady however did not allow herself to taste the luxuries in the presence of her family, though she might just "try what they were like" in secret. Openly, she avowed that the very sight of them made her sick.

Mrs. Skittles was one of those ladies possessed of such delicate nerves that the slightest ruffle of the waves would stir the very depths of the ocean. The wrong shade of trimming on a new dress had been known to give her a bilious headache; a trifling omission in the grocer's orders would send her in tears from the table, and it would be hard to estimate the hysterical attacks brought on by dear Mr. Skittles' blunders.

He was a man that dearly loved his home, and all through the busy day, looked forward to the bright supper time when, Dallie on his right hand and his orphan nephew, Jakey Billings, on his left, and his wife opposite him, his idea of earthly bliss was realized. That is, when she was opposite him. But he was never quite sure that he should see her. Slight causes and no causes at all were sufficient to keep her in state in her shaded room upstairs.

What was a serious matter to the elders in the family, however was great fun for the children. Dallie, dear child, was sorry for her hungry papa, no doubt, but she, as well as Jake enjoyed the freedom that Mrs. Skittles; absence afforded and they would not have been "young Folks" had they not, smiled at one another gleefully across the table, while Cressy, the girl, scolded because the stewed oysters were turning cold.

The more sharply she scolded, the more gently oblivious became the weary master of the house, till he nodded an unconscious assent to Cressy's remarks. He had a happy faculty of going to sleep when the wind blew, and had wisely learned to receive a woman's gusty temper with the same philosophic treatment.

Jake was never quite so happy as one these occasions when his aunt was absent. She viewed him with the sternest disapproval because he was a boy, and tortured herself with many a distressing vision of Dallie's falling in love with him one of these days. But I will say, here and now, before Jake has outgrown his jackets, that Dallie never did fall in love with him. He was "only cousin Jake" to her--the one boyish companion of a brotherless girlhood, remembered with a smile as she recalled his merry face across the tea-table; and thought of with a sigh in later years for poor Jake ran away to sea and was lost on the first voyage.

As for Jake, however great his admiration for his cousin Dallie, he declared he liked his uncle the best of the family, "because he was all Skittles." Jake had a wholesome disgust for the "Westcott Dalrymples,"--the "Wedgewood Chinas" he would say when speaking of Dallie's maternal ancestors. Light-hearted children they were, Jake and Dallie, and lucky for them that the pitiful spectacle of an ill-mated couple looked to them at that time only like a comedy.

But with Mrs. Skittles, life though hardly tragic, was not worth the living. The little comforts of their own humble home and the luxuries forts of their landlord alike irritated her discontented mind. What is to be done with such naughty, grown-up children? We can't stand them in a corner till they come out pleasant, and so they go on till they drive all love and comfort out of the home and fret themselves into chronic invalidism or an insane asylum.

God pity those nervous sufferers who can't behave, and pity the friends of those who can, but won't. With every year, the kindly relations between landlord and tenants increased, always excepting Mrs. Skittles. One would suppose she believed that Mr. Mellis cultivated hyacinths and sweetwater grapes for the sole purpose of tormenting her. Once, when Mr. Mellis made his usual business call, she brought a choice handful of Jacqueminot roses for "the lady of the house." "If your mother does not care for them," said the landlord pleasantly, "please keep them for yourself, Miss Dimple."

She placed the roses in her pet vase and set it, thoughtlessly perhaps, on the window-sill, not noticing that the morning sun was glaring in there and would soon wither the crimson petals. But Squire Mellis was glad to observe them there, and exclaimed, as he turned from his window to go to his office,--"I'm glad Dimple got the roses." After that, every rent bill was sweetened with a bouquet.

One Saturday morning, some months later, Dalrymple had just attended to her usual duty of receiving the landlord at the door and came in with her hands full of lilies. Perhaps it was the contrast that gave her such an unusual color her mother thought. Dalrymple drew a low stool beside her mother and said, with much hesitancy. "Do--you--suppose--mother--you--could--ever--bring--your--mind--to--such--a--thing--as--my--being--engaged?"

"Engaged! Why Robert Dalrymple Skittles! You are not acquainted with a single boy in town!"

"I know it mother. But this is a man."

The truth flashed, at once, upon Mrs. Skittles. "I told your father, years ago, when we talked of hiring this house that it never worked well to live under the landlord's eye, and now see what has come of it! To think, after all we have done for you that you should disregard our wishes at the first temptation. Ready to leave your poor papa, and no matter anything about your poor mother,--I won't mention her. Ready to leave home and school and go over and keep house for Mr. Mellis! You can sit up there in your fine drawing-room and see your mother washing dishes by the kitchen window."

"Oh mother, mother!" cried Dalrymple. "Don't go on so. I only asked about being engaged. I had not thought of all the dreadful things you are talking about."

"What ails my pet?" interrupted Mr. Skittles, coming into the room, his honest face troubled at the sight of the unusual tears in Dallie's sunny eyes. "Don't say anything about it, mother," whispered Dallie. "This is the last of it. Of course, it is all out of the question and I could not leave you."

A smile of satisfaction came over the mother's face. "Oh, Dalrymple is alright, father," said she. "She was crying, silly child, at the thought of leaving home supposing she should ever be married. I tell her soon enough to cry when the time comes."

The next morning, Mrs. Skittles and Dollie could not help noticing the unusual expression of Mr. Skittles' face after the carrier had left the morning mail. He did not look unhappy, but evidently, something serious was on his mind. At last, it came out.

"I have just had a letter from our landlord, Dallie," said her father tenderly. "You can guess what it is about, I suppose. Well, child, I'm not the one to hender ye. You've been a good child and the light of the house, and I've looked for this question to be put to me by somebody sooner or later. Your mother has tried to prevent anything or the sort, but even if she had kept you in her pocket-book--and dear knows how hard it is to get that open!--somebody would have spied my girl."

"Don't talk like a fool, Mr. Skittles," exclaimed his wife, fairly crying. "Dalrymple knows it is silly for a child like her to think of such things; and, in my state of health, how am I ever going to spare her, I would like to know? She wouldn't want to leave home herself, either, would you, Dalrymple? Wild horses wouldn't drag you, would they?"

"No, no," sobbed the girl, thoroughly humiliated. This new, sudden vision of love and marriage was as startling as it was delightful, and was naturally regarded by her as forbidden fruit when thus dragged into the dazzling light and ridiculed by her mother. Silly or not, most girls of seventeen and eighteen have their heroes. Perhaps the admiration may be at most a distant sentiment for somebody they do not know even to speak to. In this case Dallie's landlord had ever been in her estimation like a prince in an enchanted castle.

She had far too humble an opinion of herself to suppose he cared in the least for her, but she loved to look out upon his beautiful grounds and at the fine mansion she could see from her chamber windows and try to fancy how the beautiful rooms she had never seen were furnished. Secretly, she thought him the finest-looking person she had ever seen, and, though she always dreaded to answer the bell when he came for the rent, she cherished every tone of his voice and every word he spoke from one month to another.

As for Mr. Mellis, he had not lived to the age of twenty-eight without an affaire du coeur or two of his own, but those had resulted unfortunately. Both ladies in these cases proved unworthy. For a couple of years he had turned his back on society and devoted himself to business. The little time he had spent at home was generally in his own room and, from its windows he could not only see his own lovely garden but the humble home of his tenant, Mr. Skittles. It was a pretty picture that often met his eyes;--this dazzlingly beautiful girl, as modest as she was beautiful, tripping about the kitchen, carrying dishes from the sink to the pantry; or, on baking says with bib apron and sleeves rolled up, cooking as deftly as her mother.

Prettier still was it to see her helping her father in the garden, for then she seemed the happiest, and her light laugh rang out as joyously as a bird's song. Mr. Mellis' proposal however, was almost as unexpected to himself as it was to Dallie. A sudden impulse prompted him to say what he did, but it was an impulse seconded by sober afterthought. "I should have spoken to her father first," he reflected, and made the amende honorable by writing a most respectful request to Mr. Skittles that he would favorably consider him as a suitor for his daughter's hand.

As we have seen, Mr. Skittles was willing to forget his own comfort for the sake of his daughter's good, but Mrs. Skittles, though secretly flattered that their landlord admired Dalrymple could not bring her mind for an instant to think of giving up her daughter, and Dallie was in such subjection to her mother's will that she did not presume to question it. The result was that Mrs. Skittles carried the day. She persuaded her husband that Dalrymple was distressed and alarmed at the idea of marrying anybody.

Mr. Mellis received a respectful letter from Mr. Skittles conveying the reply that his daughter was yet too much of a child to know her own mind and that both she and her mother did not favor the marriage. "I kinder hated to send that letter, Dallie," he remarked, that evening after the decisive missive had been forwarded. "I don't never want to get red of you Dallie, as far as that goes, but Mr. Mellis is a fine man, and one of these days, ef you and he make it up, I am not the one to say no. You can't keep your father and mother always with you, my child."

Dallie, distressed now beyond measure, fled from the table to her own little chamber. She glanced out upon the "enchanted castle," but the sight only gave her pain. She seemed forever shut out from the right to admire and enjoy the beautiful flowers and terraced slopes again. In a few days Mr. Skittles received a brief business note from Mr. Mellis announcing that he was about to leave town to travel abroad for an indefinite absence and that Mr. Skittles could hand the rent money to his agent, giving the address. Mr. Mellis closed with a regret that his late proposal had been unwelcome and trusted that Mr. S's daughter would ultimately gain the happiness in life she deserved.

The mansion in sight of the Skittles' windows was closed within a week. Beggar boys stole the pears and grapes and trampled down the rare flowers with no one to molest unless a policeman chanced to be in sight. And no tidings of their landlord came to the family in the house on the backstreet.

Dallie's father was a painter, a house painter, I mean, not an artist. Among Mrs. Skittles numerous woes, not the slightest was this that she must always breathe an atmosphere of oil and turpentine. If she chanced to pass a freshly-painted house, the Dalrymple nose would become perceptibly elevated and she would exclaim "Dear me! Mr. Skittles! How that brings you to mind!" Poor Mr. Skittles did his best to keep his business from annoying his wife. He had established an impromptu dressing-room behind the woodshed door, where an unspotted suit hung by day and a painter's blouse and overalls by night.

He was careful not to appear in this last regalia in the presence of his wife. But he was always welcome to Dallie, whether he wore the tidy, well-kept suit of brown or was covered with as many paint samples as an artist's pallet. She had a childish fashion of talking to the familiar brown suit when her father was away. Mr. Skittles had few holidays. He was always striving to procure some luxury his wife was whining for and it was necessary to keep steadily at work to supply both luxuries and necessities.

The Westcott Dalrymples had, it is true, an aristocratic reputation, but very little money, and the fact was, though she would never own it--Matilda Dalrymple had really never been so comfortable in wordly goods as since she married the industrious painter, Hiram Skittles. There was to be a union picnic of the Sunday schools a few weeks after Mr. Mellis set forth on his travels.

"I think it is my duty to go and take Dalrymple," whined Mrs. Skittles at the breakfast table. "Though I feel such a care always when she is with me. She does get stared at so, and then some of those superintendents think it is their duty to shake hands with everybody and introduce everybody. I am afraid that a chance acquaintance made at such a time might make trouble with Dalrymple."

"Oh mother, mother!" exclaimed Dalrymple impatiently for her, "If you would only let me alone!"

"That is the way!" wailed Mrs. Skittles. "That is all the thanks we poor mothers have for our solicitude." Dallie was swift with apologies and comforting words, but there was deeper regret when she spoke to her father. "Oh, papa dear! If only you were going too I should be so glad!"

"I know it, pet, and so should I. But Mr. Bingham is in a tearing hurry to get his house painted. He just stands below and bosses us men until we are nearly crazy. I couldn't get off before afternoon, no how. I'll try to then, if it is a possible thing. Look out for me by the 1 o'clock train, dear."

"What's that?" piped Mrs. Skittles from the kitchen door. She held her handkerchief to her face, for her husband was arrayed in his working clothes and she fancied she could already detect the obnoxious odor of turpentine. "What's that?" she repeated. "You going to the picnic! Well, I only hope you'll allow time to get off all trace of paint, or the day will be spoiled for me." The long suffering husband repressed a sharp reply which might justly enough have been flung back, and with one more good-by to Dallie, he was off.

Mrs. Skittles, with a martyr air dressed for the picnic. In her heart she was glad to go and Dallie well knew it. There was little of the belle now in the face of the nervous and faded woman, but she still cherished the belief that she was uncommonly good-looking, and claimed for herself at least half the admiring glances bestowed upon her beautiful daughter.

The morning passed gaily as mornings generally do at picnics. Fresh toilets are as yet unstained, babies have not become tired and cross, children are not overloaded with lemonade and ice cream, rash boys have not tumbled out of swings nor drowned themselves in the lakes, lovers have not yet quarreled;--in fact everything is just in that perfect state where anticipation has just met realization.

There was a pleasant confusion of table spreading. Some of the party were walking to the station to meet the incoming train which would bring an accession of picnicers. Dallie was one of these. She had established her mother comfortably upon a bench under the shady trees, for Mrs. Skittles was never one of the active workers on such occasions. Her constitution would not permit it, she said.

As Dallie drew near the station, the train had arrived and laughing groups were hurrying up to the picnic grounds. Dallie looked intently for her father, but was disappointed;--the good, honest face she had hoped to see was nowhere among the passengers. She turned about and was wearily retracing her steps when a boy accosted her. He had shot from the train the first one and had already made the tour of the grove, not finding the one he sought. Now, he put a yellow enveloped message in Dallie's trembling hand.

Dallie's was one of those natures that cannot faint and burden others in awful extremities. Before she opened the envelope, she experienced that fearful strangling in the throat that accompany the hearing of shocking news. She realized that the saddest thing that could happen to her was about to happen. This swift premonition prepared her somewhat for his brief message from her family physician. "Your father fell from a staging--dangerously hurt. Come a once." A.F. THORNE, M.D.

Grief and anxiety were now at their height, and now torture added its sting, for it was simply torture to tell Mrs. Skittles what had happened and endure the selfish plaints she uttered. Strongest of Dallie's sensations was the unbroken prayer--"Oh, spare him till we get home!" That prayer was answered. The poor girl was in time,--only in time to hear his good-by. "God bless you, my little Dallie! I wouldn't a shocked your mother in this way if I could a helped it. It was the staging give way--not I. The men will tell you so. God take care of you both and He'll comfort you yet, Dallie, after many days."

"He did not address any special remarks to me," moaned the widow to a neighbor a few days later. "It was all Dallie with him, first and last."

"Lucky your husband had his life insured," observed the neighbor, changing the subject pleasantly.

"Yes--for my benefit," sighed the widow complacently. Dallie would have none of this "blood money" as she felt it to be. For once in her life, she would have her own way. She insisted upon earning her own living. She applied for a vacancy as a book-keeper, but, before engaging in the place, a position as teacher was offered her in the primary school. Dallie loved little children, and on assuming the role of teacher, she blossomed into a dignity and enthusiasm that left nothing to be desired in the opinion of both scholar and supervisor.

But though happy when busy in the school-room, her heart sank like lead when she came in sight of her own dear home. Sometimes, she would linger in the wood-shed and whisper fondly to the brown suit that still hung in its accustomed place behind the door. "Poor, blamed, banished papa!" she would cry, and put the empty sleeves around her neck and dry her hot tears against them. Then she would suppress her emotion and go in to cheer up who mother who always saved for Dalrymple a list of the domestic discomforts of the day,--all of her own unhappy moods and tenses--all the failings of long suffering Cressy, the maid-of-all-work. And then as a finale she would moan the refrain of all her grief,--"If your poor papa had only lived!"

Friends and neighbors often reiterated a part of this regret--"If Mr. Skittles had only lived," with the additional remark, "and if Mrs. Skittles had only been taken." It is a mystery indeed that generally the brightest, the best, and most useful members of a family are first allowed entrance to the Better Home.

Dallie grew only the lovelier under the trying discipline. True, the old, glad expression had gone--the pink in her cheeks was fainter and the droop of her shoulders and her languid walk showed she was overworking and lacked the inspiration of love. Months grew to years. Changes came to other homes. Many of Dallie's old school-mates went to homes of their own. It was rumored that Mr. Mellis had given up his law business entirely and would devote himself to mining interests in a distant land. Subsequently, the report came that he had lost everything. One confirmation of this report was that Mrs. Skittles was notified to pay the rent money into the hands of a new agent.

Strangers soon took possession of the neighboring mansion which held poor Dallie's vain dreams. The familiar garden was speedily transformed into a very different looking spot. Most of the old shrubs were uprooted,--the terrace graded into one velvet slope; and, on its bank, the skillful gardener, before many weeks had formed in rich mosaic of foliage plants,--a brilliant cross. It seemed to Dallie that it rested on her heart rather than on the green earth. The mansion was lively with voices, young and old, but the children were seldom permitted in the grounds where the old English gardener held sway. When they went out for an airing, they were too elaborately dressed to play, and a capped and aproned nurse walked beside them to see that their toilettes were not disarranged.

On one of the rare occasions when the little ones walked in the garden, with the nurse saying "shoo" on this side and the gardener saying "shoo" on the other, as if they were so many trespassing chickens, Mrs. Skittles sat by Dallie's chamber window, mournfully gazing out upon the scene. "Look here a minute, Dalrymple!" said she. "Don't you think Squire Mellis would have let his children play there? He liked those old-fashioned snowball bushes and lilacs and the roses--what a master hand he was for roses! Oh, Dalrymple, I'm afraid I made a mistake. But you see I wanted you all to myself. Will you forgive me, child?"

"Don't speak of it, poor mother!" said Dallie, "It can't be helped now."

"But, Dalrymple," persisted her mother. "I must say something. Did you ever have any other beau but him? Oh, Dalrymple, what if you should be an old maid!"

A look of scorn that was strange to Dallie's sweet face contracted her lips for an instant, but it gave place instantly to her usual, noble expression. "Don't worry about that, mother," she said. "There could never be but one love for me, any more than there could be more than one papa."

"As to that," said the widow, with a silly smile, "I may say that you have had more than one chance of another papa and I have not decided what answer I shall give to old Dr. Thorne on the subject. Don't be foolish, Dalrymple."

Oh, the bitterness of having a mother so unlike in every respect that there could be no sympathy! Yet before the sacred name of mother, Dallie could check an indignant reply. "It is not pleasant to speak of anything so unpleasant and unlikely, mamma," said she gently and walked out of the room, lest she should say more. From this time, Mrs. Skittles' thoughts centered upon a new worry,--"What if Dalrymple should be an old maid."

The poor girl had cause to blush more than once because of her mother's attempts at matchmaking. When the new minister, in his round of pastoral invitation, called at "the house on the back street," Mrs. Skittles astonished him with her remark,--"What do you think, Mr. Ballard! I was engaged at sixteen, and married at eighteen, and here's my daughter, still in the market at twenty-eight!" Of course, the minister was disgusted with the widow's evident angling, but he observed the closer and with increasing admiration the daughter in question.

In fact, he gave Dallie the trouble of refusing him as she had refused many suitors before. Mrs. Skittles was none the wiser, though it might have soothed her troubled soul had she known that Dallie was appreciated. By the time Dallie was thirty a new trial came to her. She was obliged to give up her congenial occupation of teaching and devote herself entirely to her mother. The nervous tendencies which Mrs. Skittles had shown for years, now developed in alarming proportions and were pronounced as insanity.

"You are wrong," urged a friendly neighbor, as Dallie declared her intention to take care of her mother herself. "You have given up your whole life to her, already. Now, she does not know one person from another. She would kill you in one minute, when her raving moods are upon her. Why will you do it?"

"She is my mother," said Dallie simply, "and she is all I have in the world to care for." And care for she did till the tortured, raving spirit slept in heavenly rest, its disease forever cured,--its sins forgiven, and, let us hope, its power of tormenting taken away by Him who of old cast the devils out of women, and men as well. The day she died, Mrs. Skittles' reason returned for one brief glimmer. "Poor Dalrymple!" she sighed. "God will make it up to you after so many days."

Shortly after her mother died, Dallie received a notification from the agent to whom she was accustomed to hand the rent, that the house she occupied had again been sold and that she must look for a new home, as the present owner wished to take possession as soon as possible. Poor Dallie! How she loved the little home where all her life had been spent. How could she give it up! She fairly broke down as she never had done before, and all her woes seemed dissolving into tears that would have their way.

As she was thus overcome with this last grief, Dr. Thorne happened to call and of course she had to explain her trouble. After a few moments' consideration, the good man said: "Don't be so down-hearted about it, Miss Dallie. I have an idea. Maybe this man that has bought the house would let you retain a room or two. I know,--he hasn't much of a family and he is kind-hearted and accommodating, I promise you. I suppose you don't feel much like meeting strangers, but I shall ask him to call round here this very evening and we will have this matter attended to without delay."

"Oh, I don't dare to hope!" smiled Dallie through her tears, but it was plain she did hope very strongly, for she had known Dr. Thorne so many years and he was not a man to offer unlikely encouragement. After tea, when Cressy had washed the dishes and gone out, Dallie went about the dear old home, from room to room, talking to each familiar spot as if it were a cognizant spirit.

"Oh, I hope I shan't have to give you up! Dr. Thorne says perhaps I may stay." The door-bell startled her. "The new owner!" she exclaimed. It chanced that Cressy had carelessly left the front door ajar, and immediately after ringing, the new owner saw this opportunity of entering which he improved and took possession at once. Took possession not only of the dear home itself but of its mistress' trembling little hands, as she was coming from the bright sitting-room into the shaded hall.

"Oh, Dimple!" he cried, glad to notice that the alarm in her face was giving place to utter joy--"After so many, many days!" We can imagine what long and interesting stories each had to tell the other--stories of over fifteen hard years. At last, they both felt that dying prayers had been answered and that God had, indeed made it up to them "After many days." They felt so truly, but the less sanctified neighbors sometimes remarked that Mrs. Skittles surely had took more than belonged to her when, without other reason than her unwillingness to part from her daughter she forced her to give up a lover, in every way desirable, so that the brightest days of youth were lost to them both.

However there is not now a happier pair in ----- than Mr. and Mrs. Mellis,--though early youth is gone and wealth is gone. They even looked serenely and without envy on the English gardener's floral abomination on the velvet slope that they can see from their kitchen windows. They are happy that they can spend their lives together in "the little house on the back street." THE END.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Armstrong flooring ad in November 1969 Ladies' Home Journal

#ladies home journal#retro magazines#retro home decor#retro interiors#1969#armstrong flooring#retro ads

39 notes

·

View notes

Text

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

via Heritage Auctions

Walter Martin Baumhofer (American, 1904-1987) Big Shot, Ladies Home Journal story illustration Oil on canvas.

Beautiful vintage illustration of a boy's fear 🔥🎨

10 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Image from page 1137 of "The Ladies' home journal" (1948)

11 notes

·

View notes