#kroton

Text

Jackie Tyler, River Song And A Kroton

#2nd doctor#patrick troughton#10th doctor#david tennant#11th doctor#matt smith#jackie tyler#camille coduri#river song#alex kingston#kroton#classic who#doctor who

75 notes

·

View notes

Text

Wade likes Chaz better from a distance

#chaz thurman#chaz#chazwick thurman#helluva boss chaz#helluva boss#helluva boss fandom#helluva boss fanart#Wade#kroton#oc#art#furry#furry oc#fursona#furry anthro#furry character#furry fandom#furry art#original species#original art#artist of tumblr#artists on tumblr#digital art

33 notes

·

View notes

Text

60 Years of Doctor Who Anniversary Marathon - McGann 2nd Review

The Company of Thieves: Comic

The Doctor and his companion, Izzy, land aboard a space freighter right when it's being attacked by pirates. They must escape the space-faring mercenaries and get back to the Tardis, but along the way they confront a crazed scientist, a talking gun, and a Cyberman with a soul.

This was really good. It's easily one of the better comics we've come across.

At the only three parts long the comic manages to keep up a brisk pace without feeling rushed or overcrowded despite juggling a lot of new concepts.

The best of these new ideas is Kroton, the Cyberman who can still feel. This is his introduction story and he really sells the comic. I'm actually interested in checking out more just for this character.

But that's not to say that the other characters are bad either. The pirate captain, his mutinous first mate, the insane hermit scientist, and his sentient gun; all mange to be really colorful and memorable in just a few short pages.

Ironically it is the mains, The Doctor and Izzy, who are the least interesting here, but they aren't bad. The Doctor is still the Doctor, and Izzy gets to be active and contribute to the story. She's just is a little generic here, but that's mostly because the story is focused on setting Kroton up as a new companion.

The artwork is good. It makes good use of the black and white format to really create bold contrast and easily readable silhouettes without sacrificing too much detail.

Even if the Doctor does look a little insane in a few panels.

But that's kind of part of the charm.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

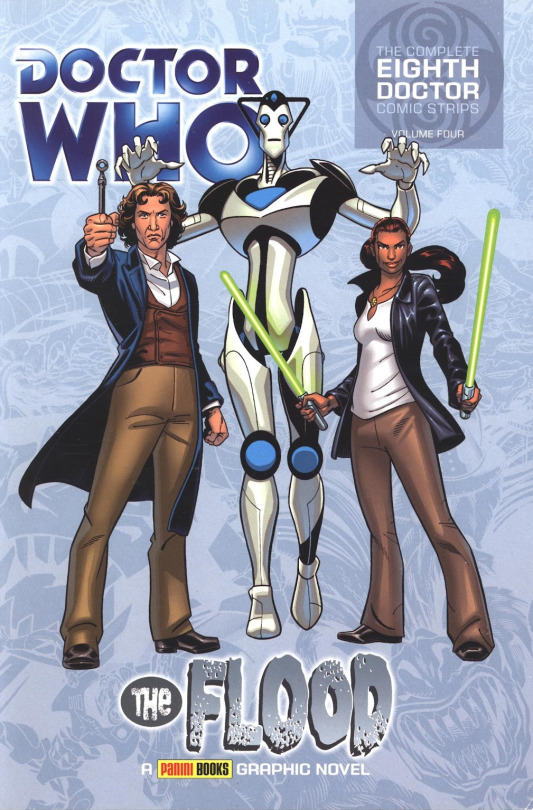

Anthony Lamb's cover art for "Cybermen: The Ultimate Comic Strip Collection" revealed

Panini have released to final cover art for Cybermen: The Ultimate Comic Strip Collection by Anthony Lamb, the new Doctor Who omnibus collection

Panini have released to final cover art for Cybermen: The Ultimate Comic Strip Collection by Anthony Lamb, the new Doctor Who omnibus collection due for release on 1st September 2023.

Utilising models owned by Gav Rymill, Anthony has produced a stunning image, the futuristic Cybermen from the Eighth Doctor comic strip story, “The Flood” to 3D life.

Written by Scott Gray with art by Martin…

View On WordPress

#Andrew Cartmel#Anthony Lamb#Cybermen#Doctor Who#Doctor Who Magazine#downthetubes News#Gav Rymill#Kroton#Martin Gergahty#Mike Collins#Panini UK#Scott Gray#SF Comics

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Something I Read - The Eighth Doctor Strips

So, while I haven't (yet) heard all of Eight's audios, there are only a handful left. And I have started reading the books (going through Kursaal right now. You can find my commentary of the books on the 'bookshelf' tag). So, while I have a lot to go through, I wanted to start something new, different, exciting.

And so I decided to read the Doctor Who Magazine comics. And what a ride it was.

To make it easier for me and to write a cohesive text, I'm going to talk about individual stories and then at the end of each volume comment upon the overall arch.

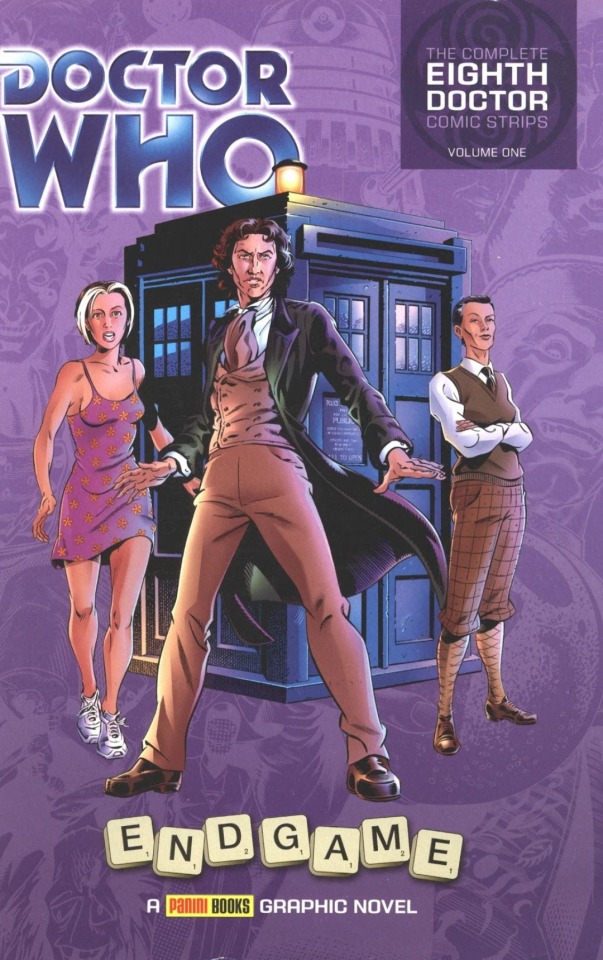

Endgame, by Alan Barnes - ★★★☆☆

It's not a bad start, but not my favorite. The Toymaker is a fun concept but his stories are very inconsistent to my tastes. Here, he is fine. The comic is smart in the sense that the use the format to its fulliest, allowing the Toymaker to be as cartoonish as ever - and it fits.

And even tho there is a comedic tone, he still comes off as a threat. There is a gruesome scene where he crushes a character bones and flesh. You can feel the pain. I usually do not like when a new companion is introduced in a continuity heavy story as I think it takes atention away from them.

Izzy is great. She is a geek, she is witty, she wants adventure. She is flawed, I couldn't help but wince at how selfish she sounds when she talks of her parents - which she has been fighting with over insecurities about being adopted. She doesn't even call them mom and dad anymore. And that makes her come alive. She is a breathing, living person. And we have a wonderful journey ahead in a yellow brick road.

The Keep, by Alan Barnes - ★★★★☆

The comics got me here. Endgame is nice and all, but it's The Keep who starts playing with bold new ideas for the stories. I got a glimpse of what I could get out of these and I loved it. I was all in for the ride.

Eight and Izzy arrive at the far, far future, near the time the sun is failing and soon enough it will be no more. It's Earth dying days. It's a wasteland. The whole planet turned into a warzone as the Transmat Wars begun - a concept never fleshed out but engaging nonethless.

What's more interesting, though, is that a local scientist have dedicated his whole life to building a superficial star. It had unexpected consequences, as it turned out that it's actually alive. Eight is nedeed so someone bonds with the star, guide it towards the right path. Crivello, the scientist, tried - but even short exposure to the star was enough to make him age years in a blink. A time traveller - even better, a time lord - is needed.

I find the scene Eight merges with the plasma beautiful. This incarnation more than any other feels to me like a force of nature, a constant to the universe, and so I'm always on board when he is influenced by forces outside his control - and vice-versa. Izzy gets anxious and cries, because the Doctor may have died, and it finally hits her that if he does, there is no way back home - for now the narrative don't dive into this topic, but it's a nice touch still.

And then the story takes your breath away, as when everything seems nice and done, Crivello is brutally murdered by his assistant.

Fire and Brimstone, by Alan Barnes - ★★★★★

I did not want a Dalek story, but I am glad I got one because this one is great. It continues the plot points left open at the end of The Keep, as Izzy and Eight visits the same place decades later. The new artificial sun is now stable, but there is a threat in the horizon.

I love that plasma from the Cauldron can be used to see the future, and I love that Eight still have a link to it because they'll always have a bit of each other. I really like the wasps weapons (biological?) the Daleks use to control the humans. It's horrifying, it's disgusting, it looks great. It's truly unsettling, the panels of characters vomiting hordes of insects after infection.

The Daleks are a real threat this time around and it makes perfect sense that they would try to irredicate genetic variants from other dimensions. It's a pity that we see little of that conflict, because the mutant Daleks looked GREAT.

I was devastated that the Cauldron imploded at the end. It all ends considerably well, but there is a wild sorrow of knowing that a whole new lifeform died. I love a rich diverse universe, and I want it to last. What is even more bitter, though, is Eight's silent rage that he can't right now strike back at the Threshold - you can tell by looking at his face in the last page how furious he is over Ace.

Tooth and Claw, by Alan Barnes - ★★★★★

The superior Doctor Who's Tooth and Claw, mind you. I loved this. It's a horror story at heart. The Eighth Doctor and Izzy are pulled into a murder mystery plot in an isolated, atmospheric isle as one old acquaintance of his, Fey, call for his help. And then the guests start dying, one by one.

It's fun, it's believable and it's the kind of horror story I am always open to. Conflict comes not only from the apparent supernatural menace, but also from humans interactions - Marwood hunting Izzy is terrifying, the human ability to be more frighting and cruel than any fictional villain ever could.

Which is not to say the fictional villain is bad, because it only gets better. From the start we are told of a local ghost; then we have bodies on the house and killer monkeys; and yet we also get bottle diseases and vampires. And it all ties well together. This is an island of terrors, ever entertaining.

It ends on a huge cliffhanger, with Izzy and Fey taking Eight to Gallifrey to help him recover from what may well be a mortal wound.

The Final Chapter, by Alan Barnes - ★★★☆☆

Reading the extras I was surprised by how harsh Barnes was with this story - it's not bad at all. Yes, a lot of its themes and plot points were better fleshed out in Neverland, but it's good for what it is.

I love the scene where Eight meets Rassilon and a whole council in his dreams. Demoiselle Drin says she has taken the seat of Merlin the Wise, and given that the Doctor himself is Merlin I wonder about these implications. I love villain Rassilon - but it's refreshing to a seemingly well meaning version of him, too. I wonder, also, as Eight is in the Matrix, if this is the same Rassilon of Zagreus. It's fun to try and fit all these piece of a jigsaw never meant to be completed.

The clone plot is not that enganging, but as Eight and Fey explores "madworld" to try to understand what the hell is happening, I was wondering if a bit of this went into Seven's part in Zagreus, with little rat Charley. And that's the main problem of this story. Ideas better realised elsewhere. A group of time lords trying to gain control of Gallifrey and rewrite its history? Neverland. A kind-of time cult? Faction Paradox. Weird surrealists scenes in the Matrix and timelords' minds? Zagreus.

The regulars are great, and the story is engaging enough. Also, the cliffhanger of a lifetime.

Wormwood, by Scott Gray - ★★★★★

This was fun and a great conclusion overall to the Threshold. It's not what I was expecting and while that sometimes oes play a role in how much I like a story, this one has ideas strong enough so that it didn't really matter.

I wouldn't say this story is mocking the Briggs-Doctor, but it does play with the readers expectations in that way in a time we only had the expanded universe. Of course I already knew Eight wouldn't be regenerating while reading these comics so it didn't hit me in that way, but it was fun nonetheless. What I thought, however, is that this would be a retroregeneration or something alike, so I was very much pleased to known that it was actually Shayde playing as the Doctor.

I'd have preferred if the Threshold were actually a natural ocurrance of the universe and not a fabricated species made mainly of humans buuuut as I said previously this is fine. I also wished to a darker motivation for them other than greed, but that's also fine. What I do like a lot is the terror that went through my body when they killed everything in space - and I wish it was not reversed at the end. Not only it would weight upon the characters, but also would be so interesting to see how the whole universe would handle something like this.

We have a glimpse of that kind of horror, of whole civilazations colapsing, but I wish we got some time to explore this idea fully.

Shayde is ine of my favorites things about the comics. It's an amazing concept brought to life wonderfully and that gets even better when coupled to Fey, who is also amazing. How they handle their new status quo is not explored here but rather in future stories, but I do have to say that I love it.

Happy Deathday, by Scott Gray - ★★★★★

It's a fun anniversary story. All these Doctors interacting is great.

The Fallen, by Scott Gray - ★★★★★

I'm not the biggest fan of Grace, mostly because I don't see many ways to use the character interestingly. Well, The Fallen does it wonderfully. There is something wrong in London and Grace is somehow at fault.

I love her relationship with Eight. It's still a bit sexual - they do kiss once more - but honestly it doesn't bother me. I do not share the opinion the Doctor should never engage in romantic or sexual relationships, I just want it to have meaning.

Grace is repenting for her faults. She thought she had a special future ahead of her beacuse of what she was told in the movie, but now she helped creating a huge danger that is getting people killed. She resents the Doctor in some ways, that he wasn't there and feels like he mislead her. She calls him out when he gets angry with her - he out the world in her hands and left her and she didn't known better.

Izzy and Eight at this point are already the dream team. Their domestic scenes are great and this time around Izzy is alone for a bit - the Doctor believes her dead. She is growing up and have already come a long way around, which is one of the main themes of her stay in the TARDIS. She is in a way a mirror to Ace - completely differente character, yes, but I mean in how she fits as a companion.

She is a sapphic character with parents issues, her stories can be read as a coming of age and her relationship with the Doctor is a bit paternal. Just like Ace. The first big arc of stories with Izzy as a companion handles the Threshold, who are responsible for Ace's death, so I don't think I am completely out of my depth when I say that this era of Eight mirrors Seven's life.

Unnatural Born Killers. by Adrian Salmon - ★★★★★

I love Kroton. If you don't love Kroton, there is something wrong with you. Seek help. This is not his introduction, he appeared on the magazine twice before - both good stories, but Ship of Fools is a must read. He is tragic to the core and deals with a concept that I love and wished to see more in Doctor Who: a faulty Cybermen, who kept this emotions.

I am happy to dicovered the expanded universe because now I have three plots like this to feed my fictional needs: Kroton, Marc and Bill. So that's no longer a problem. But I would love to see more of Kroton - it's such a pity that these stories don't leave much room to have him along Eight and Izzy because they are absolutely one of my favorites TARDIS teams ever.

Unnatural Born Killers get Kroton - already well established - and makes him even better by making him an action hero. The art is beautiful and I love every single fight scene of his. Also, he punches some Sontarans in the face. I love the guy.

The Road to Hell, by Scott Gray - ★★★★★

Izzy and Eight get to 17th century Japan, where creatures from the myths are terrorizing local population. Sato Kitsura is a samurai who just lost his lord to a demon and now seeks revenge upon these creatures.

I am a sucker for stories of fictional characters or monsters being real, so we already started strong. I also love historicals, so that's two points for The Road to Hell. And while I do prefer them to be pure historicals, I actually love how this story handles its sci-fi elements.

An alien species gave a local lady a machine that allows her to make anything alive out of her thoughts. They only wish to observe what she makes of it as they want to understand the concept of honor. It's a great idea even if not the highlight of the story, as their conflict with the Doctor is not all that much relevant, but I like it still.

What makes wonders out of this concept - besides amazing drawings of creatures and japanese pop culture - is when lady Asami uses the machine to try and see what comes of Japan in the future, when she discovers that Izzy is from the 20st century. What she sees is, of course, Hiroshima and Nagasaki. And then she goes bonkers.

What I think could've been handled better is how much seeing so impacted her psyche because she has little character layers after this points as she is going balistic. Because while she was not a good person up to this point, it's not hard to understand why she would get mad at what she saw. She has every reason to get furious. And I don't think that entitlement to anger is given proper focus. But I like it still.

This story also ends with the Doctor making Sato immortal, which he hates as he was trying to kill himself in ritual now that his revenge was done. He feels the Doctor robbed him of his honor, of his humanity even, but is dismissed. In one perspective, I like a lot what this says of the Doctor - about how him being a time lord make him insensible to others sometimes and how badly he can mishandle a situation. Because he thinks he knows better. And so he dismisses what other people have to say.

But I was also rewatching seasons eight and nine of the new series while reading these comics, so I was surprised about how similar Ashildr's character is to Sato. They are handled completely different in some aspects, and while I actually like Alshidr a lot, I would say Sato makes the most of it. I don't known if Moffat had ever read these comics, but oh my gosh it's almost the same plot.

TV Action, by Alan Barnes - ★★★☆☆

Beep the Meeo is back. Haven't read The Star Beast yet so I wasn't pumped, but he is fine. The best part is Beep being defeated by Tom Baker talking too much, however.

The Company of Thieves, by Scott Gray - ★★★★☆

Or that story where the Kroton plot comes into the ongoing Izzy storyline and we get the best TARDIS team ever.

I got worried for a second beacuse of Eight's initial reaction to Kroton - he tries to kill him and it appears to be sucessful - that I was going to be denied grandeur, but it all works out well. The crew characters are not that interesting and they look a bit too 90's comics for my tastes.

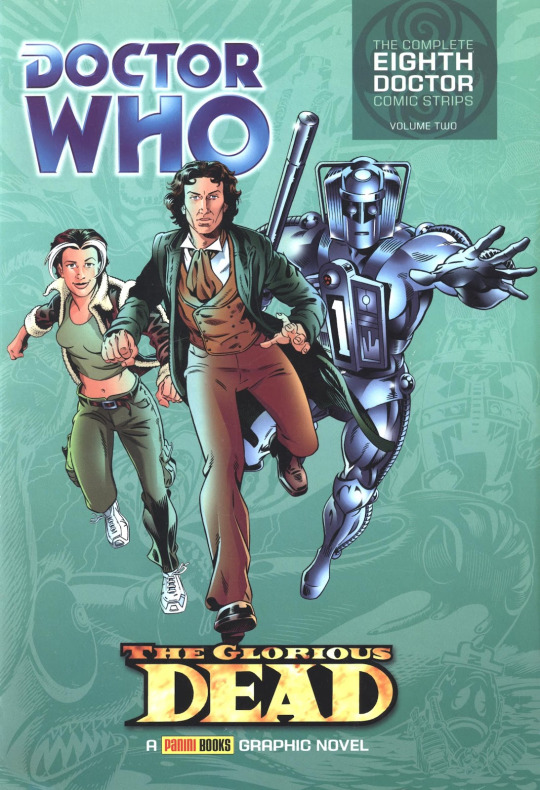

The Glorious Dead, by Scott Gray - ★★★★★

One of my favorites Doctor Who stories ever. It does everything it wants to do magnificently.

The setting is gorgeous. I love how this diplomatic meeting goes wrong in the worst way possible and we are left in this deadland. I love also how it ties to the religious themes and what makes humanity - in a loose sense of a human. The Doctor is out of the story when things gets bads; Izzy and Kroton are left to handle things themselves.

And how far has Izzy come. In one if its parts, this story makes the best of the doctorless time to show us how Izzy is now capable of doing a lot - I got my eyes wet reading her letter to Max; her relationship with Kroton is beautiful and I love how they relate by feeling like outsiders and less than human sometimes. I love that Izzy has a plan and that it works. The whole universe was doomed, but then Izzy Sinclair gave them a chance. And then she is dead.

Or so Russell T Davies thought, alongside us readers. Kroton rage after her death is heartbreaking. And then we see that Sato is somehow tied to this situation. Time made him insensible in his immortal life and now the only thing he believes in is death. Being denied death made it the thing he wants the most and the Doctor, even if unintetional, made a monster out of him. Of course Sato has personal responsabilities and this theme is dealt within the story itself, but it was his immortality that made it possible this horror movie ti happened.

And while I am in this topic, I love the body horror of this story. The way these people burn themselves to death for their beliefs is disturbing. The "monsters" desings are dope. There are a lot of alien species here, and they all look cool. Ooooh, and towards the end when it's revealed that this is what came of Earth...

And so I need ti talk about the other half of this story: the Doctor meets the Master once again. And of course he has been manipulating recents events. And it's interestingly in many layers.

First, the Master seems to have changed into someone different. Or so he says. And I do believed he did, I just don't think it was for the better. What he has now is a belief and that makes him more dangerous than ever. He may not have become a better or worthier person, but he does terrible things while trying to prove so. He wants to show how monstruous the Doctor's actions are but don't take any responsability to himself as he believe it was done for a cause. And it all comes into his need to prove himself better than the Doctor.

Secondly, it's a meta commentary on their relationship and how they destroy everything around them. And I mean that in a textual sense - they are the main characters of the story, but what about the lives of the people they leave in pieces? The Glorious Dead turns this around by making the Master - and even the Doctor, a little bit - think he has a destiny, that this story is about him and his friend. But it's not. It's about the little people. It's about Izzy and Kroton and Sato and how they try and get up again. Trying to reclaim themselves of a world that is usually center around other people stories.

Kroton and Sato are mirrors of each other in that sense; in how they are dealing with death and immortality. With loss. Of other people, of their souls. It hurts, but it's beautiful.

The Glorious Dead is one of favorites Doctor Who stories. You should read it.

The Autonomy Bug, by Scott Gray - ★★★★★

This is going to sound pedantic but I am not a comedy guy. It's not that I hate it, just that I prefer drama overall. It's why it's rare to see me having much to say about a comedy story. This was great. It's a basic concept - robots appears to have gone crazy - but handled beautifully to tell a story about what makes us, us. The characters are weirdly complex for the little time they have to show it off. The funeral scene is as sad as they come.

The ending made me emotional. It's completely different from the stories Scott Gray told in his Eighth ternure overall, and it's great by being so. It may not be my favorite of the bunch, but it stands ou as unique.

Izzy's Story, by Alan Barnes - ★★★☆☆

Second time listening to this story. The first one I hadn't read any Izzy stories yet so I wanted to see if my opinion changed. It didn't. It's not bad, I have fun with it and all, but it takes what I like the least from Barnes' stories to make an audio. It's one of Eight's most cuttest and comedy based like Deathday and TV Action and so it feels inconsequential to me.

I don't know if I agree this should be placed here. Izzy sounds a bit too immature and so I think it would work best earlier in her timeline. The plot itself of Izzy going after a comic book that desappeared is nice, but I don't care much for the conclusion.

Ophidius, by Scott Gray - ★★★★☆

This is interesting in many ways. It introduces Destrii, so that's already a must read. It also starts the body swap plot, which I love. Izzy has never been so betrayed and it's really interesting to read, as next stories will explore. And I love the setting. Ophidius is a living ship who has its own ecosystem. The people who control the ship are horrendous and the idea that so many people have been turned into beats is horrifying.

The visuals are beautiful. I love the design of the mobox when they are in fours, but I thought they didn't look that good on two legs. There are many other cool aliens designs in Ophidius, including Destrii. That chair that let Eight become invisible by placiing him just a milisecond in the future is a dope technology that, under the show rules, make sense.

I wondered for a second if Eight wasn't going to notice that Destrii was in Izzy's body but thank gosh he did. I don't like when this happens in this trope because it undermines the characters relationships and at this point Eight should be able to recognize if there is something wrong with Izzy - and he did.

Beautiful Freak, by Scott Gray - ★★★★★

A wonderful character piece. Izzy is depressed. She is in a body that isn't hers; her own destroyed in Ophidius. She feels ugly, disgusted and angry and don't know what to make from here on. Her life has changed forever. While I think Izzy's thoughts about Destrii's body are a bit cruel, it's understable. She was betrayed, she had her own body and now she won't ever be able to go home. She has every right to be outraged.

The pages where Izzy is submerged in pool as she can't breath is painful and so, so beautiful. Her dialogue with Eight gets to my heart. A sample of the best Doctor Who have to offer.

The Way of All Flesh, by Scott Gray - ★★★★☆

An interesting story. I don't think we reach the full potential of the concepts introduced here, but it's fun and emotional and have nice things ti say. We get a glimpse at Frida Kahlo's life in the Día de los Muertos as there is something terribly wrong happening.

This is a horror story. It uses body horror concepts to the fullest. It's as disgusting as Doctor Who gets. The Way of All Flesh introduces the necrotists, alien artists that make art of the dead, out of pain. A bit influenced by Hellraiser, I would say. I like that Gray chose the day of the dead as a setting for this story because it me disguted that the girl would dare to make something horrible out of such a beautiful date.

Frida also fits well into the story. She can relate to what Izzy is going through and I like that she calls her our on her bullshit. The ending is so beautiful, with Frida painting Izzy as she "was". Because it's the same person beneath. There is still the same beauty in her, no matter the state of her flesh.

Character Assassin, by Scott Gray - ★★★★★

Oh this is great. Scott Gray was already my favorite Doctor Who writer by this point but he got extra points by writing a hate piece for Moriarty, one of the most infuriating characters to ever be. Oh it was so fucking great to see him humiliated.

Children of the Revolution, by Scott Gray - ★★★★★

I thinks about Children of the Revolution a lot, even more than a month after have read it. It's my favorite Dalek story and I doubt that'll ever changed. I love the setting, I love what is done with established history and I love the art and the colors.

Izzy and the Doctor visits a friend of his who can help her acclimate to her new body, Alison. She is a marine biologist who is working in an underwater station. One day, however, they are attacked by (underwater) Daleks. What will happen next will shock you.

Nobody is exterminated. The Daleks choose to get the humans into the city they built underwater. Nobody can know they live there. Because they are peaceful. They are the Daleks with the human factor the Second Doctor helped engineer in Evil of the Daleks. In that sense this is a heavy continuity story and I could have hated it, but I don't. Because it makes something incredible out of the continuity it's using.

This Dalek city is engaging. You doubt every second when something will go wrong, because you know it will. But this time it's not these Daleks fault. It's the humans. I do think it's a complex situation because knowing every single thing the Daleks ever did I would never, ever trust any of them either and so the human characters are not hard to sympathise. But it's so heartbreaking to see something to beautiful crumble into pieces. There was potential here, for a better future, and it's shattered because of hate and mistrust.

It's interesting to have the TARDIS team as outcasts not because they put themselves in an awkward situation - they were friends with the crew - but rather because they are fundamentally different. Neither the Doctor or Izzy are humans at this point. The Doctor have story with the Daleks, and these ones trust him. They are outsiders and for once the Doctor have his hands tieds. He don't know if he can trust the Daleks, but if he don't and he is wrong - this is a chance of a lifetime. But he has no pull over the humans anymore. There is no winning.

And of course, there is Kata-Phobus. This huge, gorgeous, lovecraftian monster who has lived in this planet for ages and influenced this Dalek colony since its inception. It also influenced the conflict with the humans as it wants to feed upon them all. Kata-Phobus in a sense is there to externalize all that is wrong with the Dalek-human conflict, that ideia of racial superiority, that ideia that there are outsiders. That some people are essentialy different than others. Phobus is that fear made flesh. He plants fear and distrust in the head of these into his reach and he feeds on it.

So yes, I was moved when, in the climax, Alpha commands his fellow Daleks to autodestruction so that Kata-Phobus is defeated and they die as they wished to live - a peaceful people who didn't want any more death or cruelty in their lives. And so the Doctor and Izzy are left speechless because for once there were goods Daleks - while they saw the worst humanity had to offer. It's a must read. I love it. Just, trust me.

Me and My Shadow, by Scott Gray - ★★★★★

Children of the Revolution ends in a cliffhanger with Izzy being abducted by these weird aliens - and now the Doctor is out for blood. But that's not the focus of Me and My Shadow - this is a Doctor lite story as we are reunited with Fey and Shayde during World War II and see how they are doing - not that great, as they have difficulties sharing a body and for the modt part have agreed to be active at different times.

Fey is frustrated that she can't use her abilities to the fullest because Shayde knows what that can do with the timeline. They are now one living being, but they are not in sincrony, and that is holding them back. And we also get hem being badasses and killing some nazis. So ten out of ten.

Uroboros, by Scott Gray - ★★★★☆

The Doctor recruits Feyde to help him rescue Izzy. Somebody pointed out how this is a bit similar, but in a much smaller scale, to what he does in A Good Man Goes to War, and that's fair. He is also reunited with Destrii who, as we discover, did not actually die neither had Izzy's body been destroyed.

I know it's Destrii kissing him but that panel of Eight being kissed by Izzy's body it cursed. Burn it with fire.

I don't care much for the Mobox plot to be honest. And that's way it loses a star. It's a fair enough sequel to Ophidius and there sre some cool concepts, but the plot falls into who tropes that I don't like that much neither feel like this story had enough pages to try and do something new with then.

Still solid.

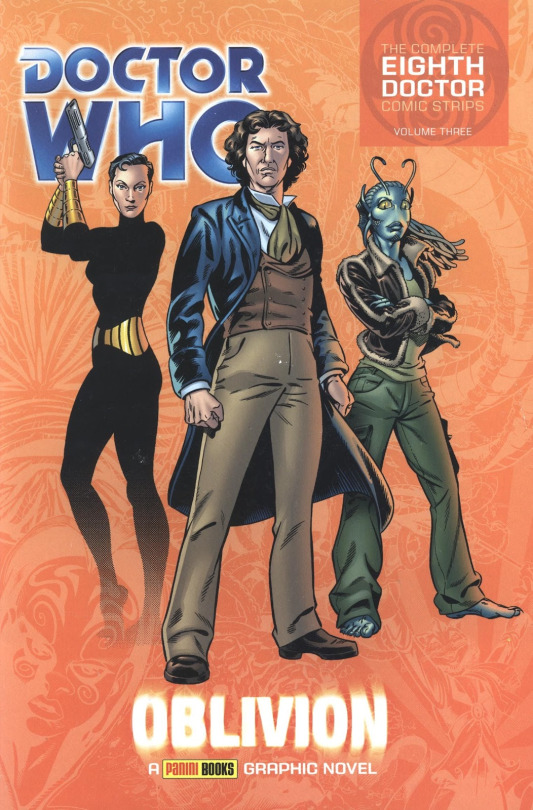

Oblivion - ★★★★★

So finally we go after Izzy, who has been taken to Destrii's homeworld. Which is very ugly. I know it's intentional because it's a wasteland, but nonetheless what a ugly, disguting place.

The local riches have turned into humanoid animals some decades before and are now there to entertain local "monsters" - who are actually people of this dimension who have been badly fucked up by actions of the royals themselves and...

This place is a mess and everybody is horrible and no wonder that Destrii became such a horrendous person. She is the most sympathetic of the bunch, actually. Her mother is indeed a monster and was horrible to her. And is horrible to Izzy, when she arrives there mistaken as Destrii. And, of course, she made her daughter fight in arenas to the death.

Destrii once had a pet, that she took care of for months, until the day her mother made her kill it. And Destrii's death since then have been pure death. I wonder why the hell the girl run away.

Oh and her uncle is not much better. He talks like a nicer man but he is as bad. He helps Destrii escape, but it's more so he could test a way to run away himself - he had no way of knowing she would survive doing so. He is only gentler as long as he get something out of it.

So yeah, Destrii is fucked up. The parallels between Izzy and Destrii are great and I love how it's written. I love that Destrii had the option to make hell on earth, but she steps away. I love that she tells Izzy how unfair she has been treating her parents. I love that she kills her mother, even.

And then Izzy. As I said before, this is a coming of age story for her. And now is fully intk adulthood, and is ready to leave home. The TARDIS. So she kisses Fey because you only live once and she is tired of being a closeted lesbian, asks the Doctor to take her to her parents and say it's time she fix things. Izzy has had many adventures and she has grown up so much, and now is time to move on.

And oh, how I will miss her.

Where Nobody Knows Your Name, by Scott Gray - ★★★☆☆

It's fine. The Doctor is dealing with missing easy while drinking in a bar. It has some fun alien concepts and the Doctor bits are fine. And unkown to him the barman is Frobisher, who doesn't know he is talking to the Doctor because he haven't met Eight yet.

The bits of Eight thinking about retiring do plant some nice ideas tho.

The Nightmare Game - ★☆☆☆☆

I tried. I promised I tried. But I have been reading hundreds of pages of wonderful imsginative stories and then I get to this and... it's inferior. It's leagues below the stories being told before.

The Doctor almost asks the worst kid to ever exist in London if he wants to travel with he him. I get that he is lonely but can we not.

Also it's that guy writing. Yeah. That guy.

The Power of Thoueris!, by Scott Gray - ★★★☆☆

Something I haven't yet is how more violent Eight is in these comics (and the books) when compared to the audios. You might think that's why three stars, but I like it. I think it's fine for some lives of the Doctor be more violent and even cruel than others.

And oh my gosh. He is savage here. That poor hippopotamo girl was irrititating, yes, but oh dear she was eating alive by crocodiles.

Overall a fun story with an art that I like but that is not that consequential.

The Curious Tale of Spring-Heeled Jack, by Scott Gray - ★★★★☆

And then we are back to form. The Doctor is still directionless and in search of his next companion to be, because he collects them as Bruce Wayne collects orphans, this time in victorian London as the city is being "haunted" by a badass looking prankster "ghost".

It has a kinda obvious twist but who cares, it's well written. And one of the best non-introductory companion stories I have seen so far as it actually does something interesting with the non-companion.

Once again the Doctor overstepped but this time he isn't called out neither by characters or by the story. I understand that the girl he met and the monster that revealed herself were two different people and you could make an argument that debating so would make a great plot, but that's not the focus of this story so instead what we see is the Doctor wiping a criminal's woman memory so she lives unaware of her crimes (and honestly without being taken to justice).

I understand why it happens, but I wish the story would delve more into the implications.

Bad Blood, by Scott Gray - ★★★★★

I like this story a lot. The Doctor arrives in the USA in 1875 in the middle of a conflict by an indigenous tribe and white people. The leader of the the tribe believes that the Doctor was sent to help them survive. The scenes where the both of them go into the "spiritual world" are beautiful.

And then there is Destrii and her uncle trying to get something out of this situation. There are "werewolfs" attacking nearby villages, which has been rising the racial tension. Jodafra and Destrii offer weapons, much more advanced than they should ever get, to the white soldiers. And, of course, there is also second intentions behind their actions.

I *must* say: Destrii is far from being a perfect person but these traits are written intentionally. She is kind of an asshole in this story because she thinks of this situation as being part of a western movie, one of the few references she has of Earth. She doesn't understand that is helping genocide, the impact of her actions. But she is not a monsters, so when her uncle put children into risk she draws a line in the sand and betrays him.

I like to think she had flashbacks to her own childhood. She is distress by children in danger while she usually have no problem with people dying. And the way Jodastra hits and almost kill her is disgusting and horrifying. Destrii is not a good person, but she is trying to be. And that's a little bit heartbreaking.

Sins of the Father, by Scott Gray - ★★★☆☆

The Doctor takes Destrii to a space station where she can be healed but the station is attacked by vengeanful monkeys who live in zero grav and centuries before were slaves of the same alien race that now owns the medical station. They are not slavers or even violent anymore but that's the only revenge the monkeys are going to get so they will destroy it anyway.

Destrii is a decent person and kinda saves the day and the Doctor offers her stay at the TARDIS. Not the strongest the DWM have to offer but not the best either.

The Flood, by Scott Gray - ★★★★★

Ok so let's start by talking about the elephant in the room. Destrii character makes sense but I still wish she was written a lil bit different here. She is not human and the only thing she knows of humanity are movies and cartoons that are filled with racial stereotypes so she reproduces them when meeting humans and it makes sense but oh my god it's so umconfortable. And I know it's intentional but still.

That out of the way, this is good. Destrii entusiasm of properly visiting Earth is contagious. Too bad they arrive just before a Cybermen invasion. And what a invasion. They have been manipulation local population through water that mess with their emotions. The guy Destrii is racist to tries to kill her because of it as his emotions are totally out of control and it seems as if he is having a breakdown.

Cybermen from the future have arrived in London and are about to try and convert everybody. For starts I love their design, they are my favorite Cybermen just for how gorgeous they look. We meet the M16 characters again and it's disturbing when their emotions are manipulated to they actually have a breakdown. It's cruel and effective when we see these characters that we have met before are hurting themselves, asking for mercy and, later, even converted.

We see them partially converted and it's disturbing.

At its heart this is the best the cybermen have to offer: a story about how our feelings is what make us humans, no matter how heartbreaking it can be, or how painful it might get.

It's also about change, as Eight's time was near its end and the Ninth Doctor was ready to make his debut.

At the climax of the story the Eighth Doctor falls into the time vortex and almost merges with it and the description of him almost becoming one with time itself is beautiful. He chooses to step away from eternity, though, for Destrii. She needs him.

It was the right choice from DWM to not have Eight regenerate here, because they got the perfect ending. Eight and Destrii walking towards the sun, ready to have many other adventures. Because their story together just begun.

This was a wonderful read and there is barely a story I could call bad. Most of them are great or classics, to be honest, and this is perhaps the best Doctor Who has ever been.

So farewell, "but change is what makes us real".

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sterben und Tod – Was man darüber lernen kann

In den Zeiten schwerer Depression habe ich Suizidgedanken. Gedanken an das Sterben, an den Tod. Das heißt vielmehr: ans Nicht-mehr-leben, noch genauer: Nicht-mehr-so-weiter-leben-wie-bisher. Zudem musste ich in den letzten Jahren das Sterben und den Tod einiger mir nahestehender Menschen miterleben. Kann man sich auf das Lebensende vorbereiten? Im Laufe der Philosophiegeschichte gab es immer wieder Vertreter einer Thanatologie, einer Lehre von Sterben und Tod. Mit der Todeslehre soll der Mensch auf das unausweichliche Ende seiner irdischen Existenz vorbereitet werden, ja, er soll regelrecht „sterben lernen“ (Platon). Die Thanatologie gehorcht dabei dem sittlichen Anspruch, dass zu einem gelungenen Leben auch ein „gelungenes Sterben“ gehört.

Thanatologie in der Antike

Die philosophische Thanatologie hat – wie fast alle Bereiche des systematischen Nachdenkens – ihren Ursprung in der Antike. Dabei erfährt die Behandlung des Themas von den Vorsokratikern zu Platon eine entscheidende Wendung: Während für die Vorsokratiker (etwa Alkmaion von Kroton, Empedokles oder auch Heraklit) die ontologische Betrachtung zentral war (also die Frage: Was ist der Tod?), geht es bei Platon um Kommunikation über den Übergang vom Leben zum Tod (also um die Frage: Was ist das Sterben?).

Bei den Vorsokratikern beherrschen die objektiven Fakten die Rede von Sterben und Tod: der Platz des Todes im Gefüge des Seienden (Topologie) und die Spekulation über seine Ursachen (Ätologie) – im Einzelfall (Gerichtsmedizin) wie im Allgemeinen (philosophische Anthropologie).

Alkmaion von Kroton glaubte: „Die Menschen vergehen darum, weil sie nicht die Kraft haben, den Anfang an das Ende anzuknüpfen“,

Empedokles erklärt den Tod als „Trennung des Feuers von der Erde“

und Heraklit meint: „Für die Seelen ist es Tod, zu Wasser zu werden, für das Wasser Tod, zu Erde zu werden. Aus Erde wird Wasser, aus Wasser Seele“.

Platon über Sterben & Tod

Platon entwickelt in der Apologie des Sokrates eine eigene Prozesstheorie des Todes, die sich weniger um ontologisch-naturalistische Deutungen bemüht als vielmehr um Metaphern und Vergleiche zum Thema „Sterben“. Sterben sei entweder wie ein Nichtsein oder wie ein Wechsel bzw. eine Übersiedlung der Seele: „Lasst uns auch auf folgende Weise bedenken, wie groß die Hoffnung ist, dass es sich um etwas Gutes handelt.

Denn von zwei Dingen kann das Sterben nur eines sein;

entweder nämlich ist es wie ein Nichtsein, so dass der Verstorbene auch keinerlei Empfindung mehr von irgendwas hat,

oder es findet, wie ja behauptet wird, eine Art Wechsel und Übersiedlung der Seele statt: von dem Orte hier an einen anderen Ort.“

Hier zeigen sich gleich 3 Veränderungen gegenüber den Vorsokratikern:

Nicht Tod, sondern Sterben, nicht Fakt, sondern „Hoffnung“,

nicht Beschreibung eines Sachverhalts, sondern gleichnishafte Referenz („wie“, „eine Art“) bestimmen die Darstellung.

Damit wird der Topos Sterben und Tod der ausschließlich ontologischen Betrachtung entzogen.

Das Ende wird bei Platon zum Übergang, entweder ins „Nichts“ oder an einen „anderen Ort“. Der Tod verliert damit seinen Schrecken, er ist kein Übel, das es zu fürchten gilt, sondern ein Ausdruck von Hoffnung, mehr noch: etwas Erstrebenswertes.

Zumindest muss niemand Sterben und Tod fürchten

Dabei wertet Platon den Ort der griechischen Unterwelt, den Hades, vom Furchtort („a-idés“, der Unsichtbare) zum Lernort („eidénai“, wissen) um. Vom Ort des Schreckens und der Strafe wird er zum Ort des Weiter-Lernens und damit der Selbstoptimierung über den Tod hinaus.

Da unser Wissen um den Tod eine Auseinandersetzung mit dem Sterben ermöglicht, kann Platon von einem solchen teleologischen Bezug sprechen und die favorisierte philosophische Lebensform, durch die der Mensch das Wahre, Gute und Schöne erkennt, an die Bereitschaft zur Auseinandersetzung mit Sterben und Tod knüpfen.

Dies gipfelt in der Meinung, alle Philosophie diene letztlich dazu, sich auf den Tod vorzubereiten („meléte thanátou“). Der Philosoph soll nach Platon „sterben lernen“, das heißt, er kann sich zum einen der Vorstellung nähern, dass das irdische Leben vergeht, zum anderen kann er lernen, darüber nicht traurig zu sein, weil ihm klar wird, dass es seinem Wunsch nach einem glücklichen, gelungenen Leben widerspräche, wenn dieses kein natürliches Ende hätte.

Interessant in diesem Zusammenhang ist die Metapher des „Loslassens“ im Sterbeprozess, etwas, das der Mensch tatsächlich einüben kann – gewissermaßen im Schlaf. Der Tod als „Schlafes Bruder“ (so in der Bach-Kantate „Ich will den Kreuzstab gerne tragen“) ähnelt am Ende des Lebens dem Loslassen, welches der Mensch am Ende jeden Tages vornimmt, wenn er sich schlafen legt.

Platons Gedanken eignen sich vielleicht mehr für Angehörige als für Betroffene, in jedem Fall eignen sie sich gut für Gespräche jenseits eines akuten Sterbefalls. Denn das Tabuthema Tod wird bei Platon zum zentralen Topos menschlicher Selbstvergewisserung. Statt das Unausweichliche zu verdrängen, wird es durch bildhafte Vergleiche bewusst ins Leben geholt.

Platon legt mit der Fokussierung auf den Sterbeprozess die Grundlage dafür, dass der Tod nicht nur als objektives Faktum wahrgenommen, sondern durch den Bezug auf das Sterben verhandelbar wird, da die Metaphorik des Übergangs der Seele, der entweder im Nichts oder in einer anderen Daseinsform mündet, als Teil intersubjektiver Kommunikation das rein persönliche Empfinden übersteigt.

Geteilte Sprachbilder in Sachen Sterben und Tod sind wiederum wichtig für Rituale der Begleitung und des Abschieds. Die Beschäftigung mit der antiken Auseinandersetzung mit dem Lebensende kann also durchaus auch heute als Grundlage des Gesprächs über Sterben und Tod dienen, besonders dann, wenn religiöse Ausdrucks- und Deutungsformen nicht zur Verfügung stehen.

Epikur über das Sterben & den Tod

Welche weiteren thanatologischen Ansätze sind aus der Antike überliefert? Epikur und Lukrez sind wie Platon der Meinung, dass der Mensch den Tod nicht zu fürchten braucht, jedoch mit einer ganz anderen Begründung. Epikur geht davon aus, „dass der Tod das am meisten Schrecken verursachende Übel“ sei. Deswegen muss man sich darum kümmern und versuchen, dem Tod den Schrecken zu nehmen. Epikurs Ziel ist es, die Todesfurcht nicht etwa durch Hoffnung zu überdecken, sondern sie als gegenstandslos zu entlarven.

Wenn der Tod „unser Bewusstsein fortnehme“, dann sei „er nichts für uns und gehe uns nichts an“. Und weiter: „Solange wir Bewusstsein haben, fehlt der Tod. Ist der Tod da, so fehlt uns jegliches Bewusstsein“. Deshalb habe der Tod für uns keine Bedeutung. Was logisch klingt, entpuppt sich bei genauer Betrachtung als unzulässiger Schluss von Bewusstseinsverlust auf Bedeutungsverlust.

Denn die Vorstellung, im Tod das Bewusstsein für immer zu verlieren, hat durchaus Bedeutung und kann Angst machen. Verlieren wir auch im Tod das Bewusstsein des Lebens, so verlieren wir ein Leben lang nie das Bewusstsein des Todes.

Die Folge: Der Tod beschäftigt den Menschen

Das zu leugnen, geht an der Wirklichkeit vorbei. Epikur meint dennoch, dass eine Nichtsbeschäftigung mit Sterben und Tod die beste Lösung sei. Nur ein Leben ohne Todesbezug ist ein gelingendes Leben.

Da es sich aber bei der Annahme, der Tod „gehe uns nichts an“, schon um einen Fehlschluss handelte, ist diese Schlussfolgerung ebenfalls falsch, zumal dann, wenn wir beim Tod nicht nur an den eigenen denken. Zumindest der Tod Anderer geht uns sehr wohl etwas an. Dass andere Menschen durch meinen Tod negativ betroffen sein würden, war mir immer ein starkes Argument für ein Weiterleben in suizidalen Krisen.

Lukrez über Sterben & Tod

Gleichwohl fand Epikurs Ignoranzempfehlung in Lukrez einen Rezipienten, der sie weiterentwickelte und zuspitzte. Lukrez fand, „dass der Tod uns nicht das Geringste bedeutet“. Wer sich dennoch mit dem Lebensende beschäftige, mache sich selbst das Leben zur Hölle – schon vor dem Tod.

Doch bietet Lukrez in seinem Bild vom Leben als Mahl, an dessen Ende ein gesättigter Gast Abschied nimmt, selbst eine Perspektive an, den Tod ins irdische Leben hineinzunehmen und zu verarbeiten. Als „Abschied“ gibt Lukrez dem Tod – positiv besetzt durch die Lebenssattheit des Abschiednehmenden – eine angenehme Bedeutung, die Trauernde trösten kann.

Denn dem Sterben als „Abschied nehmen“ haftet durchaus etwas Befreiendes an.

Ein „Mehr“ an Leben wäre ein „Zuviel“. Man kann das „Mahl“ nicht in alle Ewigkeit fortsetzen.

Also: Verdrängung, ganz im Gegensatz zu Platons Einübung, und – im Angesicht des Todes – Annahme, so wie bei Platon.

Doch: Geht das – ohne jede Vorbereitung? Wer dem Tod den Schrecken nehmen will – ohne Bezug auf das Christentum oder religiöse Deutungen überhaupt – bedarf umso mehr einer Beschäftigung mit ihm, damit sich die Depotenzierung des Todes im Sterbeprozess tatsächlich als tröstlicher Halt erweist.

Thanatologie in der Renaissance

Michel de Montaigne über Sterben und Tod

Werfen wir schließlich noch einen Blick auf die Thanatologie in der Renaissance, einer Epoche, die Bezug nimmt auf die Antike – auch beim Thema Sterben und Tod. Michel de Montaigne macht sich einerseits das platonische „Sterben lernen“ als Auftrag der Philosophie zu eigen („Que philosopher c’est apprendre à mourir“), negiert andererseits jedoch Platons Idee einer Chance zur postmortalen Vervollkommnung. Im Gegensatz zu Epikur und Lukrez erhält der Tod bei Montaigne jedoch echte Relevanz.

So gelangt Montaigne in seiner „Philosophie des Todes“ zu einer Formel, die epikuräische Endlichkeit mit platonischer Sinnhaftigkeit verbindet. Sterben lernen bedeutet für ihn, sich einerseits an den Gedanken des Todes zu gewöhnen und sich andererseits darüber klar zu werden, dass es nicht in unserem Sinne ist, unsterblich zu sein. Auf diese Weise kommt Montaigne zu einer gewissen Nonchalance gegenüber dem Tod, die nicht in Ignoranz aufgeht, sondern in Indifferenz.

Kurz: Bei Epikur und Lukrez erfahren wir, dass uns der Tod nichts angeht, bei Montaigne hören wir, dass wir nicht wissen können, ob er uns etwas angeht. Wir ahnen jedoch, dass der Tod für uns einen Sinn hat.

Montaigne, der den Essay als literarische Gattung erfand, konnte bei seiner thanatologischen Sinnsuche auf eine Nahtoderfahrung infolge eines Reitunfalls zurückgreifen, den er selbst zwar als „einen gar nicht ins Gewicht fallenden Vorfall“ bezeichnet hat, der aber maßgeblich war für seine Unterscheidung von Tod und Sterben.

Das Sterben erscheint in Montaignes Erinnerung als unbeschwerliches „in den Schlaf gleiten“, womit dem Prozess der Todesannäherung der Schrecken genommen ist. Dennoch bleibt der Tod ein Problem: Aus ihm gibt es – im Gegensatz zum Schlaf – kein Erwachen. Es sei denn, man nimmt – wie Platon – eine Fortexistenz der Seele an und einen Raum, in den sie „hineingleiten“ kann.

Fazit: Sterben und Tod

Hier verließen wir dann aber den Raum säkularer Vergewisserung, denn jede Vorstellung über den Tod hinaus setzt einen Glauben voraus, der nicht bei allen Menschen – Sterbenden wie Trauernden – vorausgesetzt werden kann.

Was alle Menschen gleichermaßen aus der Antike und ihrer Rezeption lernen können: Der Tod war kein Tabuthema und sollte es auch heute nicht sein.

Wir alle werden sterben. Zu lernen, wie das geht, ist dennoch keinesfalls überflüssig. Es kann unser Verhältnis zum Tod klären – schon zu Lebzeiten.

#todesbewusstsein#thanatologie#antike#platon#sterben lernen#epikur#heraklit#alkmaion#kroton#sokrates#tod#suizidal#lukrez#renaissance#montaigne#dr. bordat

0 notes

Text

#dwedit#doctorwhoedit#cwedit#doctor who spoilers#spoilers#dw spoilers#doctor who#classic who#modern who#my gif#**#*dw#second doctor#eleventh doctor#twelfth doctor#fourteenth doctor#the krotons#cold war#the witch's familiar#wild blue yonder#parallel#compilation

5K notes

·

View notes

Text

#mine#doctor who#dwedit#matt smith#karen gillan#i miss them so much...#i'm listening to the latest diary of river song#and there's been a lot of 'asking river about her mother' situations and i'm just like ;____;#the story with river and jackie tyler and the krotons was very fun#anyways i'm very tired... my class went on a field trip to the pumpkin patch today#and it was raining all day#but i think they all had fun#ok bye good night friends

1K notes

·

View notes

Photo

65º [520 a.C.]. Anochas de Tarentum, corrida do Stádium Anochas de Tarentum, filho de Adamatas, venceu tanto a corrida do Stádium e a corrida do Diaulos. Vindo de Tarentum, uma cidade fundada em 706 a.C. por imigrantes dóricos vindos de Esparta. Os fundadores foram Partheniae, filhos de mulheres espartanas solteiras e perioeci (homens livres, mas não cidadãos de Esparta); essas uniões foram decretadas pelos espartanos para aumentar o número de soldados (somente os cidadãos de Esparta poderiam se tornar soldados) durante a sangrenta Primeira Guerra Messênia, mas depois foram anuladas e os filhos foram forçados a sair, seu pai Adamatas lutou nas guerras messenias, e passou para o filho esse legado guerreiro de esparta, preparando-o tão bem que conseguiu vencer nas duas corridas mais importantes dos jogos. Nestes jogos, uma corrida com armadura completa foi adicionada, a corrida Hoplitodromos (numa distância de 400 metros cheios de obstáculos), e o vencedor foi Damaretus de Heraea. Milo de Crotona venceu pela quarta vez na luta, algo nunca realizado em nenhuma edição dos jogos olímpicos, a quinta vitória contando os jogos juvenis. Glaukos de Karystos, amigo de Milo, vence no pugilato usando a mão como um martelo (ele aprendeu a técnica ao ser derrotado por Milo na luta quatro anos antes). Também foram vencedores Philippos de Crotona – numa modalidade desconhecida e outro atleta desconhecido de Tebas – na corrida de carros. @prof.lucianodornelles #jogosolimpicosantigos #campeõesdeolímpia #culturacorporal #kroton (em Olímpia - Grécia) https://www.instagram.com/p/CeW0pAuun1M/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

0 notes

Text

“The HADS.”

The Krotons - season 06 - 1968

191 notes

·

View notes

Text

I'm enchanted

#doctor who#classic who#classic doctor who#doctor who classic#patrick troughton#2nd doctor#the second doctor#second doctor#the doctor#obsessed with his fruity ass#zoe heriot#the krotons#doctor who the krotons#the way he shyly lifts his shoulders... looks down and wiggles his shoulders#mecore#gif#doctor who gif

114 notes

·

View notes

Text

Wade fits into the hellaverse better than expected haha. He’s thinking that this is the last time his introvert ass is going to Mammons clown show.

#art#furry#furry anthro#furry art#furry character#furry fandom#furry oc#fursona#kroton#oc#helluva fanart#fizzarolli#helluva boss fanart#helluva boss fandom#scalie#demon#original species#procreate#wade#helluva boss#helluva boss mammon

24 notes

·

View notes

Photo

River Song and Jackie Tyler face the Krotons in "The Diary of River Song: the Orphan Quartet!"

Big Finish Productions

#10th doctor#11th Doctor#jackie tyler#camille coduri#river song#Alex Kingston#krotons#the krotons#classic who#doctor who

214 notes

·

View notes

Text

His bag. I can't.

57 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sterben und Tod – Was man darüber lernen kann

In den Zeiten schwerer Depression habe ich Suizidgedanken. Gedanken an das Sterben, an den Tod. Das heißt vielmehr: ans Nicht-mehr-leben, noch genauer: Nicht-mehr-so-weiter-leben-wie-bisher. Zudem musste ich in den letzten Jahren das Sterben und den Tod einiger mir nahestehender Menschen miterleben. Kann man sich auf das Lebensende vorbereiten? Im Laufe der Philosophiegeschichte gab es immer wieder Vertreter einer Thanatologie, einer Lehre von Sterben und Tod. Mit der Todeslehre soll der Mensch auf das unausweichliche Ende seiner irdischen Existenz vorbereitet werden, ja, er soll regelrecht „sterben lernen“ (Platon). Die Thanatologie gehorcht dabei dem sittlichen Anspruch, dass zu einem gelungenen Leben auch ein „gelungenes Sterben“ gehört.

Thanatologie in der Antike

Die philosophische Thanatologie hat – wie fast alle Bereiche des systematischen Nachdenkens – ihren Ursprung in der Antike. Dabei erfährt die Behandlung des Themas von den Vorsokratikern zu Platon eine entscheidende Wendung: Während für die Vorsokratiker (etwa Alkmaion von Kroton, Empedokles oder auch Heraklit) die ontologische Betrachtung zentral war (also die Frage: Was ist der Tod?), geht es bei Platon um Kommunikation über den Übergang vom Leben zum Tod (also um die Frage: Was ist das Sterben?).

Bei den Vorsokratikern beherrschen die objektiven Fakten die Rede von Sterben und Tod: der Platz des Todes im Gefüge des Seienden (Topologie) und die Spekulation über seine Ursachen (Ätologie) – im Einzelfall (Gerichtsmedizin) wie im Allgemeinen (philosophische Anthropologie).

Alkmaion von Kroton glaubte: „Die Menschen vergehen darum, weil sie nicht die Kraft haben, den Anfang an das Ende anzuknüpfen“,

Empedokles erklärt den Tod als „Trennung des Feuers von der Erde“

und Heraklit meint: „Für die Seelen ist es Tod, zu Wasser zu werden, für das Wasser Tod, zu Erde zu werden. Aus Erde wird Wasser, aus Wasser Seele“.

Platon über Sterben & Tod

Platon entwickelt in der Apologie des Sokrates eine eigene Prozesstheorie des Todes, die sich weniger um ontologisch-naturalistische Deutungen bemüht als vielmehr um Metaphern und Vergleiche zum Thema „Sterben“. Sterben sei entweder wie ein Nichtsein oder wie ein Wechsel bzw. eine Übersiedlung der Seele: „Lasst uns auch auf folgende Weise bedenken, wie groß die Hoffnung ist, dass es sich um etwas Gutes handelt.

Denn von zwei Dingen kann das Sterben nur eines sein;

entweder nämlich ist es wie ein Nichtsein, so dass der Verstorbene auch keinerlei Empfindung mehr von irgendwas hat,

oder es findet, wie ja behauptet wird, eine Art Wechsel und Übersiedlung der Seele statt: von dem Orte hier an einen anderen Ort.“

Hier zeigen sich gleich 3 Veränderungen gegenüber den Vorsokratikern:

Nicht Tod, sondern Sterben, nicht Fakt, sondern „Hoffnung“,

nicht Beschreibung eines Sachverhalts, sondern gleichnishafte Referenz („wie“, „eine Art“) bestimmen die Darstellung.

Damit wird der Topos Sterben und Tod der ausschließlich ontologischen Betrachtung entzogen.

Das Ende wird bei Platon zum Übergang, entweder ins „Nichts“ oder an einen „anderen Ort“. Der Tod verliert damit seinen Schrecken, er ist kein Übel, das es zu fürchten gilt, sondern ein Ausdruck von Hoffnung, mehr noch: etwas Erstrebenswertes.

Zumindest muss niemand Sterben und Tod fürchten

Dabei wertet Platon den Ort der griechischen Unterwelt, den Hades, vom Furchtort („a-idés“, der Unsichtbare) zum Lernort („eidénai“, wissen) um. Vom Ort des Schreckens und der Strafe wird er zum Ort des Weiter-Lernens und damit der Selbstoptimierung über den Tod hinaus.

Da unser Wissen um den Tod eine Auseinandersetzung mit dem Sterben ermöglicht, kann Platon von einem solchen teleologischen Bezug sprechen und die favorisierte philosophische Lebensform, durch die der Mensch das Wahre, Gute und Schöne erkennt, an die Bereitschaft zur Auseinandersetzung mit Sterben und Tod knüpfen.

Dies gipfelt in der Meinung, alle Philosophie diene letztlich dazu, sich auf den Tod vorzubereiten („meléte thanátou“). Der Philosoph soll nach Platon „sterben lernen“, das heißt, er kann sich zum einen der Vorstellung nähern, dass das irdische Leben vergeht, zum anderen kann er lernen, darüber nicht traurig zu sein, weil ihm klar wird, dass es seinem Wunsch nach einem glücklichen, gelungenen Leben widerspräche, wenn dieses kein natürliches Ende hätte.

Interessant in diesem Zusammenhang ist die Metapher des „Loslassens“ im Sterbeprozess, etwas, das der Mensch tatsächlich einüben kann – gewissermaßen im Schlaf. Der Tod als „Schlafes Bruder“ (so in der Bach-Kantate „Ich will den Kreuzstab gerne tragen“) ähnelt am Ende des Lebens dem Loslassen, welches der Mensch am Ende jeden Tages vornimmt, wenn er sich schlafen legt.

Platons Gedanken eignen sich vielleicht mehr für Angehörige als für Betroffene, in jedem Fall eignen sie sich gut für Gespräche jenseits eines akuten Sterbefalls. Denn das Tabuthema Tod wird bei Platon zum zentralen Topos menschlicher Selbstvergewisserung. Statt das Unausweichliche zu verdrängen, wird es durch bildhafte Vergleiche bewusst ins Leben geholt.

Platon legt mit der Fokussierung auf den Sterbeprozess die Grundlage dafür, dass der Tod nicht nur als objektives Faktum wahrgenommen, sondern durch den Bezug auf das Sterben verhandelbar wird, da die Metaphorik des Übergangs der Seele, der entweder im Nichts oder in einer anderen Daseinsform mündet, als Teil intersubjektiver Kommunikation das rein persönliche Empfinden übersteigt.

Geteilte Sprachbilder in Sachen Sterben und Tod sind wiederum wichtig für Rituale der Begleitung und des Abschieds. Die Beschäftigung mit der antiken Auseinandersetzung mit dem Lebensende kann also durchaus auch heute als Grundlage des Gesprächs über Sterben und Tod dienen, besonders dann, wenn religiöse Ausdrucks- und Deutungsformen nicht zur Verfügung stehen.

Epikur über das Sterben & den Tod

Welche weiteren thanatologischen Ansätze sind aus der Antike überliefert? Epikur und Lukrez sind wie Platon der Meinung, dass der Mensch den Tod nicht zu fürchten braucht, jedoch mit einer ganz anderen Begründung. Epikur geht davon aus, „dass der Tod das am meisten Schrecken verursachende Übel“ sei. Deswegen muss man sich darum kümmern und versuchen, dem Tod den Schrecken zu nehmen. Epikurs Ziel ist es, die Todesfurcht nicht etwa durch Hoffnung zu überdecken, sondern sie als gegenstandslos zu entlarven.

Wenn der Tod „unser Bewusstsein fortnehme“, dann sei „er nichts für uns und gehe uns nichts an“. Und weiter: „Solange wir Bewusstsein haben, fehlt der Tod. Ist der Tod da, so fehlt uns jegliches Bewusstsein“. Deshalb habe der Tod für uns keine Bedeutung. Was logisch klingt, entpuppt sich bei genauer Betrachtung als unzulässiger Schluss von Bewusstseinsverlust auf Bedeutungsverlust.

Denn die Vorstellung, im Tod das Bewusstsein für immer zu verlieren, hat durchaus Bedeutung und kann Angst machen. Verlieren wir auch im Tod das Bewusstsein des Lebens, so verlieren wir ein Leben lang nie das Bewusstsein des Todes.

Die Folge: Der Tod beschäftigt den Menschen

Das zu leugnen, geht an der Wirklichkeit vorbei. Epikur meint dennoch, dass eine Nichtsbeschäftigung mit Sterben und Tod die beste Lösung sei. Nur ein Leben ohne Todesbezug ist ein gelingendes Leben.

Da es sich aber bei der Annahme, der Tod „gehe uns nichts an“, schon um einen Fehlschluss handelte, ist diese Schlussfolgerung ebenfalls falsch, zumal dann, wenn wir beim Tod nicht nur an den eigenen denken. Zumindest der Tod Anderer geht uns sehr wohl etwas an. Dass andere Menschen durch meinen Tod negativ betroffen sein würden, war mir immer ein starkes Argument für ein Weiterleben in suizidalen Krisen.

Lukrez über Sterben & Tod

Gleichwohl fand Epikurs Ignoranzempfehlung in Lukrez einen Rezipienten, der sie weiterentwickelte und zuspitzte. Lukrez fand, „dass der Tod uns nicht das Geringste bedeutet“. Wer sich dennoch mit dem Lebensende beschäftige, mache sich selbst das Leben zur Hölle – schon vor dem Tod.

Doch bietet Lukrez in seinem Bild vom Leben als Mahl, an dessen Ende ein gesättigter Gast Abschied nimmt, selbst eine Perspektive an, den Tod ins irdische Leben hineinzunehmen und zu verarbeiten. Als „Abschied“ gibt Lukrez dem Tod – positiv besetzt durch die Lebenssattheit des Abschiednehmenden – eine angenehme Bedeutung, die Trauernde trösten kann.

Denn dem Sterben als „Abschied nehmen“ haftet durchaus etwas Befreiendes an.

Ein „Mehr“ an Leben wäre ein „Zuviel“. Man kann das „Mahl“ nicht in alle Ewigkeit fortsetzen.

Also: Verdrängung, ganz im Gegensatz zu Platons Einübung, und – im Angesicht des Todes – Annahme, so wie bei Platon.

Doch: Geht das – ohne jede Vorbereitung? Wer dem Tod den Schrecken nehmen will – ohne Bezug auf das Christentum oder religiöse Deutungen überhaupt – bedarf umso mehr einer Beschäftigung mit ihm, damit sich die Depotenzierung des Todes im Sterbeprozess tatsächlich als tröstlicher Halt erweist.

Thanatologie in der Renaissance

Michel de Montaigne über Sterben und Tod

Werfen wir schließlich noch einen Blick auf die Thanatologie in der Renaissance, einer Epoche, die Bezug nimmt auf die Antike – auch beim Thema Sterben und Tod. Michel de Montaigne macht sich einerseits das platonische „Sterben lernen“ als Auftrag der Philosophie zu eigen („Que philosopher c’est apprendre à mourir“), negiert andererseits jedoch Platons Idee einer Chance zur postmortalen Vervollkommnung. Im Gegensatz zu Epikur und Lukrez erhält der Tod bei Montaigne jedoch echte Relevanz.

So gelangt Montaigne in seiner „Philosophie des Todes“ zu einer Formel, die epikuräische Endlichkeit mit platonischer Sinnhaftigkeit verbindet. Sterben lernen bedeutet für ihn, sich einerseits an den Gedanken des Todes zu gewöhnen und sich andererseits darüber klar zu werden, dass es nicht in unserem Sinne ist, unsterblich zu sein. Auf diese Weise kommt Montaigne zu einer gewissen Nonchalance gegenüber dem Tod, die nicht in Ignoranz aufgeht, sondern in Indifferenz.

Kurz: Bei Epikur und Lukrez erfahren wir, dass uns der Tod nichts angeht, bei Montaigne hören wir, dass wir nicht wissen können, ob er uns etwas angeht. Wir ahnen jedoch, dass der Tod für uns einen Sinn hat.

Montaigne, der den Essay als literarische Gattung erfand, konnte bei seiner thanatologischen Sinnsuche auf eine Nahtoderfahrung infolge eines Reitunfalls zurückgreifen, den er selbst zwar als „einen gar nicht ins Gewicht fallenden Vorfall“ bezeichnet hat, der aber maßgeblich war für seine Unterscheidung von Tod und Sterben.

Das Sterben erscheint in Montaignes Erinnerung als unbeschwerliches „in den Schlaf gleiten“, womit dem Prozess der Todesannäherung der Schrecken genommen ist. Dennoch bleibt der Tod ein Problem: Aus ihm gibt es – im Gegensatz zum Schlaf – kein Erwachen. Es sei denn, man nimmt – wie Platon – eine Fortexistenz der Seele an und einen Raum, in den sie „hineingleiten“ kann.

Fazit: Sterben und Tod

Hier verließen wir dann aber den Raum säkularer Vergewisserung, denn jede Vorstellung über den Tod hinaus setzt einen Glauben voraus, der nicht bei allen Menschen – Sterbenden wie Trauernden – vorausgesetzt werden kann.

Was alle Menschen gleichermaßen aus der Antike und ihrer Rezeption lernen können: Der Tod war kein Tabuthema und sollte es auch heute nicht sein.

Wir alle werden sterben. Zu lernen, wie das geht, ist dennoch keinesfalls überflüssig. Es kann unser Verhältnis zum Tod klären – schon zu Lebzeiten.

#todesbewusstsein#thanatologie#antike#platon#sterben lernen#epikur#heraklit#alkmaion#kroton#sokrates#tod#suizidal#lukrez#renaissance#montaigne#dr. bordat

0 notes

Text

what’s with all these villains calling jamie stupid— like what did he do to you??

he’s about to beat your ass, but that’s neither here nor there

#shoutout to zoe for saying he’s untrained instead of agreeing#like 100% honestly#jamie IS NOT STUPID#we joke about the himbo stuff he’s kind and brave and slow on the uptake#but like in his time education was not the priority#war was#so the way he adapts so well to the doctors world of space and monsters#even with road bumps#proves he’s smart and intuitive and he remembers what people tell him#i just i can’t#like he gives me vibes of kids that are treated like they’re bad at school#when they’re actually dyslexic#he’s at a disadvantage for sure#but the krotons and dominators can eat bricks#classic who#jamie mccrimmon#doctor who

30 notes

·

View notes