#jidaigeki-chanbara

Text

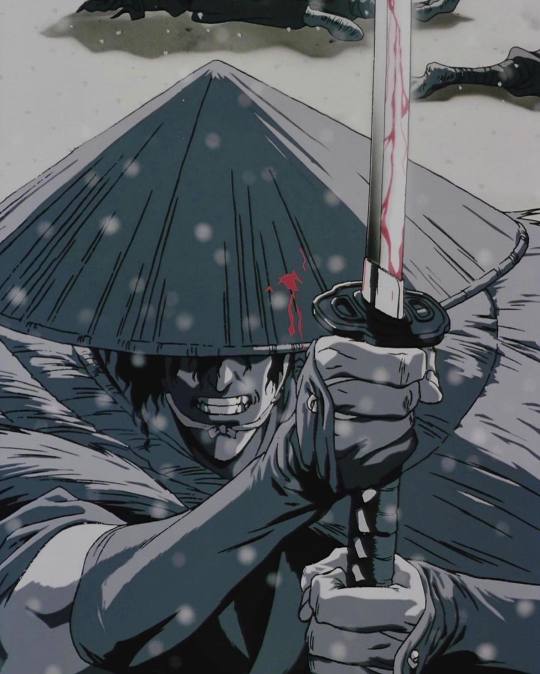

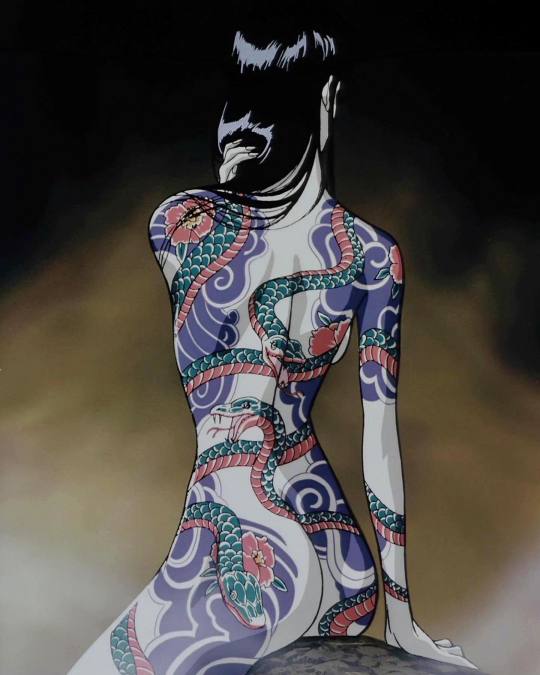

NINJA SCROLL, dir. Yoshiaki Kawajiri (1993)

#ninja scroll#1993#anime#art#film#anime and manga#anime art#best anime#yoshiaki kawajiri#demons#warrior#movies#sword#japan#shogun#jidaigeki-chanbara#jidaigeki#swordsmen#assassin#Devils of Kimon#Jubei Kibagami#Kagero#vagabond

820 notes

·

View notes

Text

Jubei Kibagami from Ninja Scroll.

"Wherever you go, people are people, the sky is sky. Nothing changes." (どこに行っても人は人、空は空。何も変わらねえよ。) 🥷 📜

#ninja scroll#jubei kibagami#anime#manga#ninja#gifs#1993#90s films#joshiaki kawajiri#jidaigeki-chanbara#period drama#mercenary#swordsman#edo period#i remember certain scenes clearly#used to have an anime crush on lol

9 notes

·

View notes

Photo

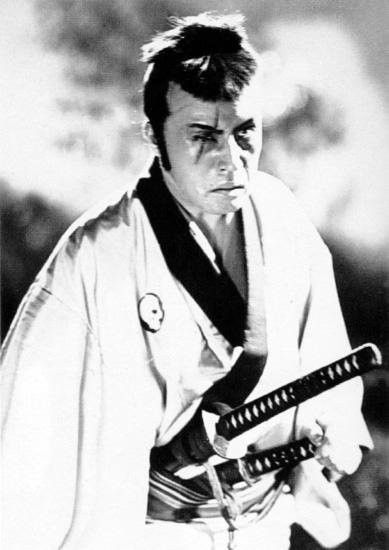

Zatoichi TV Series

275 notes

·

View notes

Text

Demon samurai going down in a blaze of glory type beat 👺🔥

#alpha chrome yayo#synthesizer#1990s#dungeon synth#japanese folklore#samurai#jidaigeki#chanbara#shakuhachi#taishogoto#koto#samurai music

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

I cut together a music video / Bunta Sugawara fancam for my latest single

#electronic#music#synthesizer#electronic music#groove#downtempo#jidaigeki#bunta sugawara#sadao nakajima#chanbara#Youtube

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Recently Viewed: Death Shadows

[The following review contains MINOR SPOILERS; YOU HAVE BEEN WARNED!]

The Criterion Channel’s synopsis of Hideo Gosha’s Death Shadow’s reads:

After their executions are faked by the authorities, three criminals are forced to become assassins under the command of the Shogun.

Technically, this is an accurate summary… of the film’s prologue. The actual story is significantly more convoluted—and I mean that as a compliment. The narrative is an intricately constructed puzzle that constantly reassembles, reconfigures, and recontextualizes itself; every scene introduces new characters, complications, and even entire subplots. If you ever find the subject matter objectionable or distasteful, just wait; the movie will be about something completely different within fifteen minutes.

This unconventional structure would be infuriatingly disjointed—were the central themes not so elegantly cohesive and clearly articulated. Like all of Gosha’s work in the chanbara genre, Death Shadows is staunchly antiauthoritarian, condemning any man that would abuse his power—including the secretive spymaster that “recruits” the eponymous assassins. After all, the corrupt clan officials, greedy merchants, and bloodthirsty gangsters that manipulate, exploit, and discard their subordinates deserve to be punished—but exceeding the limitations of the law in order to deliver “justice” is equally unethical (especially when this “necessary evil” is motivated by pragmatism rather than morality).

Beyond its deliberately puply premise, Death Shadows also represents the pinnacle of Gosha’s craftsmanship: this is the director’s style at its most economical, purposeful, and precise. He favors long, continuous, unbroken takes, repositioning the camera and performers to seamlessly transition from master shot to coverage (yes, this is very similar to Spielberg’s modus operandi)—a gracefully choreographed ballet that strikes a delicate balance between theatrical mise-en-scène and cinematic composition.

Gosha’s relatively restrained blocking and framing stand in stark contrast to the film’s unapologetically maximalist imagery. Much of the action unfolds on elaborately designed studio sets; hand-painted backdrops depict impressionistic sunsets and overcast skies, creating a surreal, hypnotic, dreamlike atmosphere—a dramatic departure from the grounded, gritty, naturalistic tone of the auteur’s earlier jidaigeki efforts (Three Outlaw Samurai, Sword of the Beast).

Thus, Death Shadows is a beautiful contradiction; serving as both the culmination of Gosha’s previous accomplishments in the industry and an evolution of his artistic vision, it resides comfortably at the intersection between avant-garde experimentation and popcorn entertainment.

#Death Shadows#Death Shadow#Hideo Gosha#chanbara#chambara#jidaigeki#jidai-geki#Japanese film#Japanese cinema#Criterion Channel#film#writing#movie review

7 notes

·

View notes

Photo

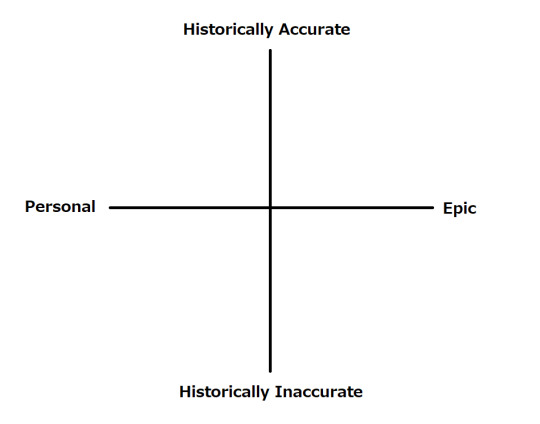

Sword of the Beast / Kedamono no ken (1965, Hideo Gosha)

獣の剣 (五社英雄)

6/5/23

#Sword of the Beast#Kedamono no ken#Hideo Gosha#Mikijiro Hira#Shima Iwashita#Go Kato#Toshie Kimura#Kantaro Suga#Yoko Mihara#Kunie Tanaka#Eijiro Tono#Shigeru Amachi#60s#Japanese#drama#action#chanbara#samurai#jidaigeki#Japanese New Wave#gold#mountains#fugitives#gold prospecting#corruption#river#assassination#social commentary

5 notes

·

View notes

Photo

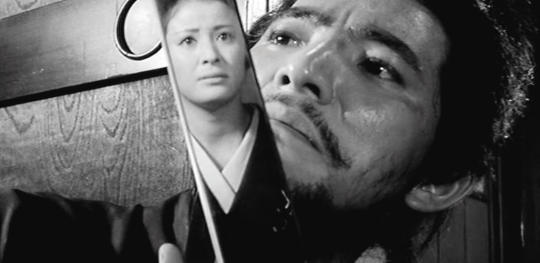

Tetsuro Tanba, the hardest working man in Japanese film (it’s said he never turned down a role), as Tange Sazen in One-Eyed, One-Armed Swordsman (1963).

This film is yet another remake of The Million Ryo Pot, based on the first Tange Sazen novel (Sazen had previously appeared as a supporting - but very popular - character in another series of stories) and first filmed in 1935. This production managed to put its own spin on the oft-told tale.

The story always involves the Yagyu Clan, whose members were advisors and/or sword trainers to the shogun. This time, instead of just a guy who gets involved with the search for a valuable object belonging to the Yagyu (a sword this time, instead of a pot), Tange Sazen is revealed to be a long-lost member of the clan. No one recognizes him because of the loss of his eye and arm, and he doesn’t reveal his identity to them, preferring his life as a wandering ronin.

Tange Sazen films since 1935′s The Million Ryo Pot had a decidedly comedic side, with many of the characters mugging and playing for laughs. Ryutaro Otomo, the actor associated most with Tange Sazen after Denjiro Okochi, had played a softer, friendlier Sazen, who wasn’t afraid to get in on the fun.

Otomo-san’s long series of Tange Sazen films ended in 1962. New studio Shochiko and director Seiichiro Uchikawwa decided to try a more serious, darker tone with the character. This was a trend that was slowly taking hold of jidaigeki and chanbara films, and would continue throughout the decade. This isn’t to say there isn’t any humor, or that Tange Sazen is any less the heroic figure he has always been. However, the film is definitely a more dramatic turn for the series.

Tanba-san also provides a physically different appearance to Tange Sazen. The character had always been presented as having lost his right eye and arm; Tanba-san’s Sazen is missing his left eye and arm. There are theories regarding why this was done, from using the change to show filmgoers that this was a different Tange Sazen than they were used to seeing, to it being too difficult or production not having enough time to train Tanba-san to use his left arm for sword fighting (a skill he wasn’t known for).

This was not Tanba-san’s first time playing Tange Sazen. He had played the role for one season of a television series that ran from 1958 to 1959 on NTV. I have found very little information on that series. I assume, however, since it ran while Otomo-san’s films were being released, that Tanba-san portrayed a more traditional Tange Sazen - comedic and missing the right eye and arm.

One-Eyed, One-Armed Swordsman ended like a Zatoichi film, with our hero hitting the road after the climatic battle. This was definitely leaving the door open for a sequel (or sequels), but they never manifested.

7 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Ninja Scroll (Iaponica: 獣兵衛忍風帖, Hepburn: Jūbē Ninpūchō, Litt. "Iubei Ninja Paralipomenon") est 1993 cinematographica animata jidaigeki-chanbara cinematographica scripta et directa ab Yoshiaki Kawajiri, voces Kōichi Yamadera, Emi Shinohara, Takeshi Aono, Daisuke Gōri, Toshihiko Seki et Shūichirō Moriyama. Pellicula co-productio inter JVC, Toho et Movic erat, cum Madhouse inserviens studio animationis. Ninja Scroll in Iaponia theatralem diem 5 mensis Iunii anno 1993 in Iaponia dimissus est et per Manga Entertainment anno 1995 liberationem Anglicam vocatam accepit.

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

1962- Denjirō Ōkōchi

Denjirō Ōkōchi (大河内傳次郎, Ōkōchi Denjirō, February 5, 1898 – July 18, 1962) was a Japanese film actor best known for starring roles in jidaigeki directed by leading Japanese filmmakers.

Ōkōchi entered Shinkokugeki (New National Theatre), training under Sawada Shōjirō (aka Sawasho). Sawada founded this new school of popular theatre in 1917 which had strong cultural impact by the early 1920s.[4] Shinkokugeki was known for jidaigeki the period drama genre, particularly for its realistic sword fights (tate) or swordplay (kengeki). With this background, Ōkōchi entered the Nikkatsu studio in 1925 and soon came to fame in chanbara (sword-fighting) samurai films – a subgenre of jidaigeki emphasizing tate[4] – playing characters such as Chūji Kunisada and Tange Sazen.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Animation Night 137: Jidaigeki the Second

Hi everyone. Hope you’re enjoying any winter holidays that take your fancy. (Hanukkah sameach!) According to Annex 3 of Animation Night Policy we do not observe “christmas” - instead, let me tell you a tale of the past...

Mukashi mukashi... back in the distant misty era of 2020, an era of bloodshed and plague and impending social change (we hope), I wrote the longest Animation Night ever.

Which mostly wasn’t actually about animation at all, but an excuse to infodump about samurai. Armed with a book with the exciting title of Japan to 1600: A Social and Economic History, I wrote at great length about everyone’s favourite feudal landlord-administrator-soldier class, and the genres of fiction that portray them...

^ me, relating information to passing tumblr users

Japanese revision time! 時代劇 jidaigeki basically just means ‘period drama’, and it needn’t have anything to do with samurai at all. Indeed, just a couple of weeks ago we watched Rintaro’s adaptation of Teito Monogatari, which qualifies as a jidaigeki despite taking place entirely in the 20th century. チャンバラ (chanbara) is a little narrower, referring to samurai films with an emphasis on the swordfighting.

Animation Night revision time! On AN 24, we watched oldschool films like Namakura Gatana [1917] and Benkei tai Ushiwaka [1939] along with Sword of the Stranger and Afro Samurai, and a small sampling of Seirei no Moribito, Samurai Champloo. Elsewhen, on AN 100 we watched The Tale of Princess Kaguya, Winter Days and Mononoke-hime, on AN 91 we marathoned Naoko Yamada’s incredible adaptation of Heike Monogatari, and on AN 122 we did the same for animation milestone The Hakkenden.

So are we out of animated films about samurai? Ha! No we ain’t.

The occasion this time? I’m itching to show you all Inu-Oh, but Science Saru are holding it tight to their chest at the moment. But there is something else!

Nahoko Uehashi is an ethnologist turned fantasy author, known for her works like Seirei no Moribito (Guardian of the Sacred Spirit) and Kemono no Sōja (The Beast Player), both of which have been adapted to anime by Production IG. In the first, Balsa, a bodyguard atoning for seven deaths, is entrusted with a young prince marked for death by his father - a prince who is, unknown to all, incubating a strange force of spiritual renewal. In the second, Erin, a girl from a culture being genocided, inherits the skill to control animals through her music and thus finds herself drawn into feudal politics.

Neither is exactly set in historical Japan, but that’s in the same way that most Western fantasy isn’t exactly set in medieval Europe. Both have a kind of thoughtful, slightly oldschool tone - highly attentive to nature, and avoiding simple heroes and villains. And Production I.G. - despite being a studio known primarily for scifi - turned out to be a perfect match.

Well, earlier this year, Production IG released their latest adaptation of Uehashi’s works in the form of 鹿の王 Shika no Ō (The Deer King). Co-director Masashi Andō has been a key animator for many many years, and in that time managed to work with just about anyone you’ve ever heard of. He drew for Ghibli under both Miyazaki and Takahata on nearly everything, for Satoshi Kon on Tokyo Godfathers, Paranoia Agent and Paprika, for 4C on Tekkonkinkreet, for Makoto Shinkai on Your Name, for Mitsuo Iso on Dennō Coil, for Mamoru Oshii on GitS 2: Innocence, for Anno on Eva 3.0... A glance over his sakugabooru page will show you why: he’s an expert in the realist tradition, not quite as flashy as some of his peers like Ohira or Inoue, but with a fantastic sense of naturalistic motion and an ease at drawing all sorts of weird angles.

^ this guy’s in a lot of gifs, he seems important

The Deer King was Andō’s first time directing, so he was joined by Masayuki Miyaji, who worked himself up from being a production assistant at Ghibli to storyboarding on a whole long list of TV anime, and acting as one of two ‘assistant directors’ (not entirely sure what that entails) on Spirited Away, before hopping into the director’s chair with Xam’d at Bones in 2008-09. Miyaji is of the school that situations animation within film at large, taking inspiration mostly from live action - or at least he was at the time of Xam’d.

So what’s it about? In a feudal setting cut up by war and plague, a slave and a young girl survive an attack by plague-carrying dogs and make their escape, hoping for a peaceful life - a classic Uehashi adoptive parent situation. But with the plague running rampant, prejudice everywhere, and the empire’s doctors searching for a cure, they won’t get it. It’s a lot of novel to pack into one film, and I’m warned that it struggles a little to contain it all, but Ando’s enormous experience shines through to give a film full of subtle and expressive animation.

Anyway, it’s one I’ve had my eye on for ages, so I’m really eager to watch it with you.

youtube

Now, let’s roll back the clock a bit. No, not quite to the sengoku jidai - 2012 will do. The Annecy International Film Festival is weighing up a massive slate, including a couple you may remember like Wrinkles (AN 87) and Children who Chase Lost Voices (AN 132). But there’s an odd little one tucked in there: a film by Toei, adapting the 70s manga Asura by George Akiyama. It’s a story set at the beginning of the sengoku period, where drought and famine wrack Kyoto, following a feral child who survives an attempted cannibalistic infanticide as he grows up amid all the war and devastation. Buddhas will be carved, symbolically. It’s that kinda thing.

George Akiyama was controversial in his day for his depictions of suicide, self-mutilation and cannibalism; ComiPress called him the ‘unstoppable king of trauma manga’. After making a serious impact with a bleak apocalyptic sci-fi story inspired by the infamous Maoist cult the Japanese Red Army, and even more so with an autobiography in which he revealed he had mixed Japanese-Korean parents (inspiring Big Racisms in those days), he surprised everyone by retiring. It didn’t stick. He moved from scandalising Shōnen Jump readers to adult manga, then back, uncannily anticipating the Aum terrorist attacks. He sounds like a fascinating guy and I’d like to read him some of that. Maybe it will be a Comics Comints one day. Hehe.

The most curious thing about Toei’s adaptation is the animation method. It’s very common now to place 2D animation in 3D scenes, but here we see the opposite: traditionally painted backgrounds populated by stylised 3D characters. Viewed with modern eyes, it has an interesting, uncanny look - certainly videogamey, but I’m curious to see how it works in a larger film. This CG approach may seem less odd when we consider director Keiichi Sato had the year before directed Tiger & Bunny at Sunrise, whose story of corporate-funded superheroes needed CG to plaster logos across the suits. Sato would actually later go on to mostly work in live-action film, notably the adaptation of Gantz we watched on Toku Tuesday 40.

I can’t guess what we’ll all make of Asura. It could be really great, a neglected classic like Birdboy - or it could end up being so exaggeratedly grimdark as to end up kind of goofy. We’ll find out! Animation Night would be no fun if we stuck to the well-known roads. At a brief 75 minutes, Asura is a pretty digestible size like an OVA episode.

After all that war and death, we probably want a breather. 百日紅 Sarusuberi (Miss Hokusai) looks at a different aspect of history - the renowned ukiyo-e painter Hokusai, best known for that one wave you might have seen here and there. Hokusai, it turned out, had a daughter called Katsushika Ōi, who followed her dad’s footsteps into ukiyo-e. Her story caught the eye of mangaka Hinako Sugiura.

Sugiura is another one I’ve got to have a look into. A manga artist with a deep interest in history, particularly the Edo period, she learned manga from Murasaki Yamada - not just a regular in the pages of Garo magazine, the fascinating alternative manga magazine, but a feminist essayist and a poet. Sugiura also debuted in Garo, drawing on ukiyo-e to great effect for her historical manga. She retired from manga in 1993 to focus on her research, and became something of a TV personality, supplying NHK with information on the Edo period for a comedy program.

The film intercuts Ōi’s life with her dad’s, a series of episodic stories in which we meet other painters from the period and watch Ōi growing up in the Edo period, working uncredited and trying to figure out sexuality. The animation comes from a studio called... Production I.G.... hmm I think I’ve heard of those guys?

So this time, the director was Keiichi Hara. While Masashi Andō was enjoying that wide-ranging career with all the big name directors, Hara was doing one thing, and that was directing Doraemon and Crayon Shin-Chan for Shin-ei. Two of the absolutely largest anime franchises in Japan, they don’t get a lot of play abroad - but then one is a kids’ series and the other leans heavily on Japanese wordplay so it’s not entirely surprising. From 1984 to 2005, Hara directed a movie for one of these two franchises nearly every year...

...I’m not kidding!

Anyway, it seems that in 2005 he decided he’d had enough (I can only assume) and from that point on he started directing non-franchise films. Quite a few of them actually - something for a future Animation Night, perhaps.

With Miss Hokusai, Hara could call on Production I.G. legends like Toshiyuki Inoue and Norio Matsumoto to realise a detailed, grounded Edo Period in exquisite detail. The clips I’ve seen look beautiful - I’ll try and have more than that to say later, but I am absolutely categorically out of time at this point.

So! Two Production I.G.s doing what Production I.G. do best, and a little oddity of Toei’s. If you’re willing to indulge me, please head over to

-> twitch.tv/canmom <-

for some mobies!

We may be up a bit late by UK standards, but I hope you can hop in for a bit, as suits! Movies will start in about 20 minutes (~21:20 UK time), modulo audience. See you theeerrreeeeeee!

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

On the nature of historical fiction

I have been thinking about this for a couple of weeks now, as I have been writing/researching my own piece of historical fiction. However a recent ask on @the-archlich‘s blog, as well as playing Ghost of Tsushima has made me want to get out my personal opinions on this subject. I will be ignoring concepts like historical fantasy or alternate historical fiction in this discussion and be focusing on the overarching category.

By nature of its design, historical fiction tends to fall into rigid categories. To elaborate, this is because it is based on an actual period of time. In my view tends to fall into a grid with two axes, which I will broadly refer to as accuracy and scale.

Accuracy is (as it implies) how true it is to the actual events and the history. You can get a very rigid historical fiction on one extreme and a very loose telling of the events on the other.

Scale refers to how involved the story is within the events of history. Are you telling an epic tale with hundreds of characters sprawling across a decade? Or is your story a personal one, which mainly uses setting as a backdrop? It would be the difference between a war-epic like Romance of the Three Kingdoms and a naturalist story like A Doll's House.

While this seems like an easy dichotomy to understand there is a factor I neglected to mention: cultural memory.

Cultural memory is how events are popularly interpreted. This can (and ususally does) cut against the recorded historical events. While this usually ends up creating inaccurate fiction, leaning on already established ideas can create a feeling of authenticity.

This is where something like Ghost of Tsushima comes into play. Ghost of Tsushima probably sits right about here:

Ghost is probably one of the most historically inaccurate games I’ve seen in a while. The swords are all wrong, as is the armour and the narrative goes entirely against what happened during the Mongol invasions. However, it feels authentic to the cultural memory of not just the Mongol invasions, but the samurai period as a whole.

It must be remembered that Samurai fiction and the cultural memory of samurai has largely been shaped by jidaigeki storytelling and chanbara film. So when playing Ghost the reason it feels authentic is because of how embedded it feels within the cultural memory of the samurai.

Cultural memory however, is a double-edged sword. It is the main reason why the narrative of Romance of the Three Kingdoms has prevailed for so long, and why much of the fiction of the Three Kingdoms Period feels stale. You have to really try to find something like DW7.

So the question becomes "What is the ideal place that your historical setting should target?" This is gonna differ for everyone, but what I personally like (and what I am personally writing right now) targets here:

I definitely have a preference for personal stories than epic stories. It's probably why of the Four Classics, I actually like Dream of Red Mansions the most. Moreover, a lot of chanbara and jidaigeki (and Japanese storytelling in general) fall into this category as they use the (rather broad) Edo Period as a backdrop to tell stories. This comes in part as a result of censorship within the Tokugawa bakufu. People were not allowed to tell certain types of stories that criticized the government, and in so doing developed a type of naturalist storytelling.

As a Historian though, I am fine with some historical inaccuracies if it serves a purpose in the narrative. In my storytelling, this is why I prefer to create characters that are analogues to actual people and try not to get the historical figures too involved in my story, which is a benefit that more personal stories and most jidaigeki use to their advantage. However this does not mean I wipe away the historical figures completely. They need to be actively involved in the larger events of the story, and can interact with your characters for important reasons. But what I want to avoid is that fan-fiction feeling of "Liu Jiao, secret cousin of Liu Bei teams up with Sima Yi to bring down the Cao Wei dynasty. (Looking at you, Ravages of Time).

Of course there will be exceptions to my personal standard and times when I break it. Part of writing generally is knowing when and how to break the rules. But make sure you carefully consider what you do before you do it.

65 notes

·

View notes

Photo

ICHI (2008)

67 notes

·

View notes

Photo

UGETSU (1953)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OaMehVoz_mM

A beautiful Japanese ghost story.

Sometimes, getting everything you want is getting what you don’t want, and losing what you need.

#ugetsu#jidaigeki#samurai#chanbara#movie#film#review#black and white#ghosts#ghost#supernatural#ghost story

1 note

·

View note

Text

Made a new song and music video

youtube

#electronic#music#synthesizer#electronic music#youtube#groove#chanbara#jidaigeki#chambara#red peony gambler#hibotan bakuto#junko fuji

0 notes

Text

Recently Viewed: Samurai Wolf

In Samurai Wolf, director Hideo Gosha shaves his already minimalistic chanbara formula all the way down to the bone. Although conspiracies, intrigue, conflicting loyalties, and double identities abound, these recurring tropes merely provide narrative context rather than serving as central themes. The setting is likewise quite modest compared to the lavish, densely populated feudal cities and quaint, fertile farms that tend to define the jidaigeki genre; the story instead unfolds in a remote ghost town nestled amidst an imposing mountain range, where the ramshackle buildings and dusty, desolate roads evoke an almost post-apocalyptic atmosphere. Even the heroic ronin du jour lacks his archetype’s trademark tragic origin, swaggering onto the screen pretty much fully formed, with only the clothes on his back (his frequent shirtlessness notwithstanding).

The simple, straightforward, no-frills plot allows Gosha to focus his creative energies on what truly matters: the style. Every image is a beautifully crafted work of art. The action is, of course, exquisitely choreographed, making excellent use of slow motion, precise editing, and dynamic framing (including claustrophobic closeups, sprawling wides, and disorienting Dutch angles) to add variety to the intentionally chaotic battles. Expository dialogue is filmed with equal care and attention to detail. In one early scene, for example, our protagonist negotiates with a prospective employer while casually trimming his beard, using his sword as a makeshift mirror; thus, both characters remain visible in each shot/reverse shot via the reflective surface of the blade, lending visual flair to the otherwise basic compositions.

Samurai Wolf isn’t Gosha’s best movie (that title rightfully belongs to either Three Outlaw Samurai or Hunter in the Dark, despite my personal preference for Sword of the Beast), but it certainly ranks among his most effortlessly entertaining. Running a lean, breezy seventy-five minutes without sacrificing any of its emotional resonance, it proves the old adage, “Sometimes, less is more.”

#Samurai Wolf#Hideo Gosha#Film Movement#Japanese cinema#Japanese film#jidaigeki#jidai-geki#chanbara#chambara#samurai movie#film#writing#movie review

3 notes

·

View notes