#insect clicking

Text

Insect Songs: Dog-Day Cicada - Neotibicen canicularis & Black-Legged Meadow Katydid - Orchelimum nigripes

In today's exploration of insects and their songs, we 2 familiar species today that are quite prevalent in Ontario's summer months. We begin with the tree-dwelling shriekers that seem to grow even louder when heat increases. Just as with Crickets and other Orthopterans, the large-bodied Cicadas only sing if they are male. To produce their sound, they rapidly expand and contract a membrane behind their thorax called a tymbal. Knowing this information, you can actually identify males and female by looking for the tymbals, which (in this specie) is located underneath the wing. Be very gentle when handling a Cicada in order to see this tymbal, and if it screeches in response, it's definitely a male. That said, unlike Orthopterous insects, Cicadas do not use stridulation to produce their song, as that process describes insects rub certain body parts together (e.g. see below) to produce sound. Vibrating a membrane doesn't match the description. If anything, it's more like flexing a muscle and allowing the hollow-filled body to amplify the sound so that all can hear it.

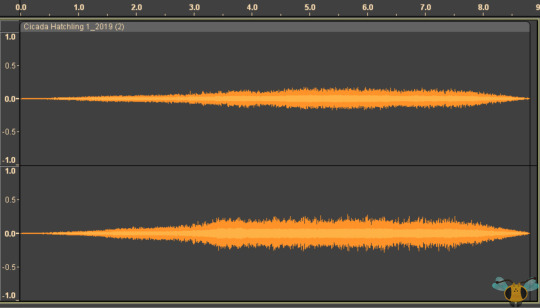

Pictured below is a typical example of how a Cicada song normally appears in audio form. It is a distinct, clear sound. Headphone warning, a Cicada shriek can be very shrill, even if the audio has been gently reduced.

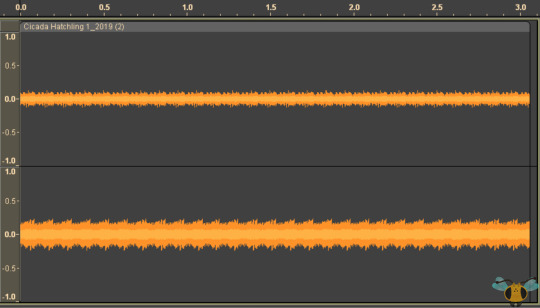

As mentioned in this blog's 100th post, the Cicada's song appears continuous because of the tremendously rapid expansion and contraction of this membrane. The muscles controlling the membrane are so powerful that the tymbal can vibrate several hundred times per second. The faster the vibration builds (for this specie), the higher the pitch of the song becomes. That said, just as a Cricket's chirp can be isolated to clicks, a Cicada's song can be slowed down to hear the individual pulses. After slowing the screeching down by several hundred times, this is the result:

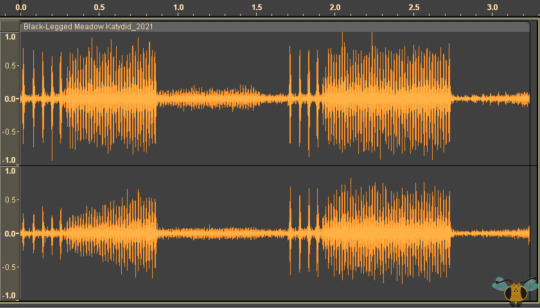

On the other side of the summer of insects, most Katydids generate their mating calls using wing-to-wing stridulation. There are exceptions of course (such as the Drumming Katydid), but today's specie has a loud method of communication! Like its Cricket friends, the loud, continuous sound is many clicks in rapid-succession. In fact, you can actually hear the beginnings of the clicks at the start of the song before the wings suddenly accelerate and make the call distinctive. Considered the role flight muscles play in controlling the wings and their noises, it's no surprise how the song can suddenly turn loud. It's very likely that the song can only be sustained in short bursts to prevent muscle damage or heat buildup, which is to say nothing of exposing oneself to a predator. The sound is alluring, for both mate and hunter alike. Pictured below is a typical example of the Black-Legged Meadow Katydid's song (headphone warning):

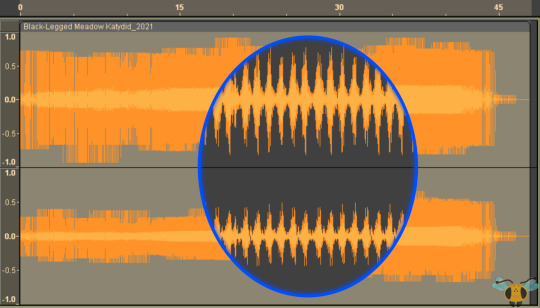

Do note, that while this is louder compared to the Cicada song, I was much closer to the source. If I was next to a singing Cicada, that too would have been an incredible amount of decibels! Nevertheless, when this Katydid's song is slowed down, the individual clicks become more prominent. Looking at it immediately after slowing the tempo down a few hundred times, a quick burst of less that one second becomes nearly 45 seconds of clicks! To showcase this, I've included a "portal" that offers a zoomed in look at the slowed song. Each spike in amplitude is a click of the wing-scraping. Even at reduce speed, you can hear the gradual acceleration of the clicking as the song goes on (headphone warning):

Pictures were taken on August 24, 2019 (Dog-Day Cicada) with a Samsung Galaxy S4 and on September 5, 2021 (Meadow Katydid) with a Google Pixel 4. Audio amplitude graphs were created using Audacity and samples from the following blog videos:

Black Legged Meadow Katydid | Dog-day Cicada

#jonny’s insect catalogue#ontario insect#cicada#dog day cicada#katydid#bush cricket#black legged meadow katydid#orthoptera#hemiptera#auchenorrhyncha#true bug#insect#insect audio#toronto#august2019#2019#september2021#2021#insect clicking#insect noise#a closer look#insect chirping#nature#entomology#invertebrates

5 notes

·

View notes

Note

hello hellsitegenetics I have decided to try my luck here. I'm a marine science student and a general fanatic of the ocean so if I don't get some sort of Ocean Beastie I will be very sad. blast please don't do me dirty I'm on my knees begging you. please.

String identified:

tgtc a c t t c . ' a a cc tt a a ga aatc t ca 't gt t ca at a. at a 't t ' ggg . a.

Closest match: Agriotes lineatus genome assembly, chromosome: 10

Common name: Lined click beetle

#tumblr genetics#genetics#asks#requests#sent to me#astral-nautical#<- i can tell you're a marine sci student lol#bugs#insects#beetles#lined click beetle

449 notes

·

View notes

Text

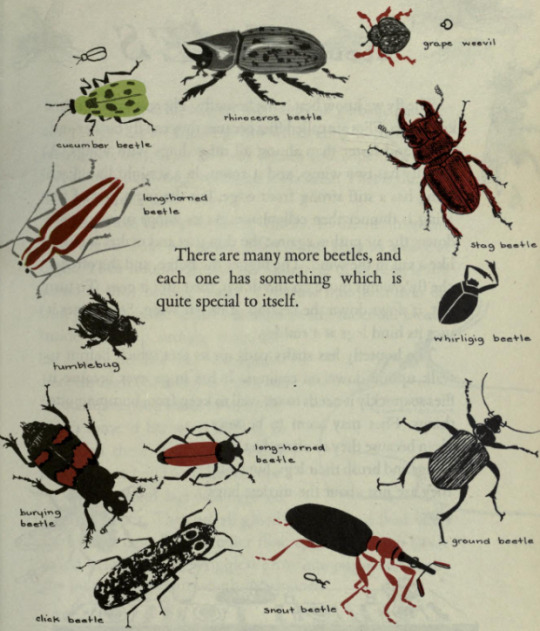

The First Book of Bugs. Written and illustrated by Margaret Williamson. 1949.

Internet Archive

#bugs#insects#beetles#cucumber beetles#rhinoceros beetles#stag beetles#scarabs#burying beetles#click beetles#eastern eyed click beetles#long horned beetles#ground beetles#whirligig beetles#weevils#Margaret Williamson

3K notes

·

View notes

Text

Eyed Elaters (Alaus)

eyed elater click beetles, like this Alaus oculatus from Florida, are the biggest click beetles (Elateridae) found in temperate North America.

Click beetles are best known for their eponymous clicking ability- a sort of elastic locking mechanism on their thorax can snap open with a loud clicking sound, which helps them startle or escape the grasp of predators and allows them to launch themselves into the air when overturned (you can see that in slow motion at the end of the video)

(more elating click beetle trivia below!)

They live around decaying trees and logs, the adults feeding on sap flows and other sugary liquids while the predatory grubs use their powerful jaws to tunnel in search of other wood-dwelling insect larvae to devour (by contrast many smaller click beetle larvae, often called wireworms, feed on rotting wood itself or other plant matter). To rear these beetles in captivity it’s necessary to keep the larvae in containers made of a hard material like glass, as they’ll chew through plastic and escape (I learned this the hard way the first time I found and attempted to raise a grub).

There are 6 Alaus species in the US, the largest of which can be over 5 cm long. Two are found in forests along the east coast- A. oculatus, the eastern eyed elater (below, left) and its smaller relative A. myops, the blind elater (right).

Even though the larvae don't feed directly on decaying wood, different Alaus species prefer different trees- oculatus breeds in dead oaks and other hardwoods, while myops found in the same habitats only use well-rotted pines.

#beetles#elateridae#click beetle#coleoptera#Alaus#eyed elater#Alaus oculatus#Alaus myops#bugs#bugblr#entomology#insects

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

Please keep in mind, when you pull back the skin. I am full of nasty, nasty things.

#art :0]#Illustration#original art#gore cw#insect cw#nudity cw#What they don’t tell you about making original art is that it is so strange trying to tag it.#Girl idk!! Just send it out into the crowd ok!!#tumblr love making my shit blurry as fuck. Click for better viewing ok

189 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ignelater havanensis, a large bioluminescent click beetle.

as if elaterids weren’t already fancy enough with their click mechanism, the tribe Pyrophorini have light-producing patches which glow brighter than most fireflies! their larvae are predatory and the adults eat fruit. one of the best neotropical beetles in my opinion… the US gets just a handful of species in Florida and Texas

one of the big gals glowing! almost enough to read by in a dark room, the video doesn’t do her justice

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

bro is made out of TV static

western eyed click beetle pal, Alaus melanops

168 notes

·

View notes

Text

dramatic

316 notes

·

View notes

Text

an Elaterid (click beetle) on Stemonitis splendens (chocolate tube slime mold)

by Richard Tehan

#stemonitis splendens#stemonitis#slime mold#myxomycota#chocolate tube slime mold#richard tehan#elaterid#click beetles#beetles#insects#bugs#forest floor#myxomycology#entomology#ecology#protists#microbiology#macro photography#fungi#mycology#forestcore

389 notes

·

View notes

Text

@fluffydogsquad submitted: Flipped over a big stick in my yard and found a bunch of friends. Any idea who the winged friend could be? Also the pal with the long black-and-orange segmented body. Found in New Jersey.

Looks like a gall wasp, I think. Couldn't say which species. The second dude is a rove beetle, maybe Paederus littorarius or similar. The last one is a click beetle, probably a sweet click beetle, Aeolus mellillus. Great group of pals! Always fun to see what's under a rock or stick.

#animals#insects#bugs#submission#wasp#gall wasp#beetle#rove beetle#click beetle#sweet click beetle#Paederus littorarius

63 notes

·

View notes

Text

i NEED tumblr to see this very cool beetle i found today!!

#insect#bugblr#beetle#click beetles#texas eyed click beetle#Alaus lusciosus#eyed click beetles#i fucking love this man so much#entomology#coleoptera

54 notes

·

View notes

Text

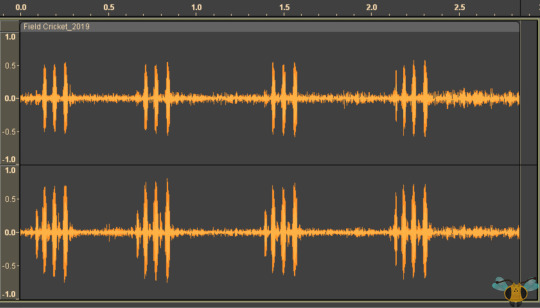

Insect Songs: Fall Field Cricket - Gryllus pennsylvanicus

Throughout last week I revisited a video on this blog that showcases a crafty Cricket sheltering within a rocky hollow while singing his song. His hideaway simultaneously functioned as both protection from intruders and amplifier of his chirping. While both listening to the audio over and over to clean it up and writing a description for its upload onto YouTube, I was reminded of one of the more important facts regarding insect noises and calls of this type. Plain and simple, what we're hearing is not one continuous sound; it is instead a series of rapid clicks/blips that coalesce together into a series of chirps. It sounds continuous given the speed at which the (in this case) wings scrape against each other. For this post, I want to show you what I mean and allow the opportunity to hear the difference, but I do apologize for any background noise. The audio displayed here is a small sampling taken directly from the singing Cricket video residing on this blog. I recommend you revisit it to see this great specimen in action and observe how his chirps are made using his wings rather than his legs.

Pictured below is a typical example of how a Field Cricket song normally appears in audio form. Each chirp appears in a series of 3 amplitude spikes. Listen for yourself:

Sounds normal and as to be expected. The rapid wing movement makes a cohesive, pleasant, attention-grabbing chirp. However, if you isolate one of those amplitude spikes in the series and slow down the tempo by (at least) 100%, you can start to hear the individual clicks made by the wing stridulation. The sample below has been slowed by 200% in order to make the clicks a bit more distinguishable. And so, here are the individual clicks in a Cricket's song:

Admittedly, the background noise make it sound like there is a loading delay between clicks. Rest assured, this is not the case: the audio sounds correct. There you have it: the artistry of a male Field Cricket's song. For the next post, we will turn our attention to 2 more insects that grace us with songs during the summer months. Stay tuned for more.

Pictures were taken on October 7, 2019 with a Samsung Galaxy S4. Audio amplitude graphs were created using Audacity and samples from the following blog video: Fall Field Cricket

#jonny’s insect catalogue#ontario insect#cricket#insect songs#insect chirping#insect clicking#insect audio#field cricket#fall field cricket#orthoptera#insect#toronto#audio#2019#2021#october2019#nature#entomology#a closer look#insect noise#invertebrates

1 note

·

View note

Text

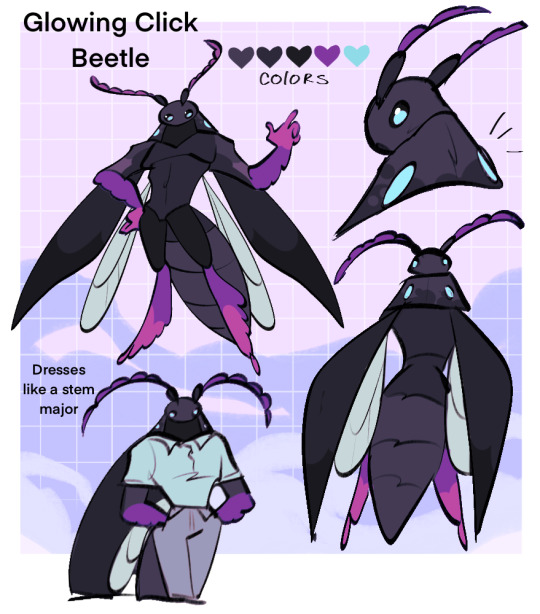

Glowing Click Beetle but make it purple !

#my art#bugs#insects#digital art#insectoid#character design#original character#ocs#anthro#click beetle#beetle#sorry I've been talking a lot sometimes a feel guilty for it lmao#here's beetle art to make up for it

336 notes

·

View notes

Text

i think WH's last Big Update has permanently rewired something in my head because the mental jolt my brain gets whenever i see a small bug jpeg is, quite frankly, ridiculous

#every time i barely stop myself from lunging at those little things with the cursor#my brain goes BUG BUG BUG CLICK ON IT BUG#at this rate if im ever on a different site with small bug adornments. i gonna instinctively click on them#its absurd. why is this a thing now#like i know Why#several hours straight of searching for them. them popping up out of nowhere. clicking on them asap bc i didnt know if theyd vanish or not#My Mind Is Now Wired To Click On Bugs#absolutely unprompted#its such a knee-jerk reaction#the insects#Give Them To Me.

80 notes

·

View notes

Text

click beetles are truly romantic creatures 😍

#alaus oculatus#eyed elater#click beetle#coleoptera#beetles#elateridae#bugs#bugblr#insects#entomology

516 notes

·

View notes

Text

Click beetle (species unknown) in northeastern US

#click beetle#beetle#coleoptera#nature photography#nature#bugs#biodiversity#animals#inaturalist#arthropods#entomology#insect appreciation#insects#bugblr#macro photography#pennsylvania wildlife

43 notes

·

View notes