#he just gets possessed by the spirit of idioms past every now and then

Text

Genuinely what was going through Iroh’s mind as he said that fighting the Firelord was the ‘Avatar’s battle’. Yeah I understand that history will see it as a power grab, but I think we have bigger problems than that. Like, I don’t know, THE FACT THAT SOZIN’S COMET IS IN A FEW HOURS AND THE AVATAR IS NOWHERE TO BE FOUND.

#Bro was like I’m going to let this thirteen year old with a year of training fight my brother#who was been training longer then has been conscious for#Instead of me#someone who has dedicated his whole life to the art of bending#Not surprising coming from the guy who let his 17 year old nephew rule a war-torn nation#Just go fight your brother dude please#Iroh is a 100x funnier when you realize he’s literally the epitome of “head empty”#he just gets possessed by the spirit of idioms past every now and then#He’s literally doing what Zuko did in Ba Sing Se (saying everything was great and fine when it was clearly not)#except for a much longer period of time#he is so used to having his way that he just lives in his own world of ‘everything will work out in the end’#this makes me think Iroh and Zuko are foils honestly#Azula and Iroh on the other hand are cinematic parallels#that’s why they hate each other#to some extent they know how destructive their mindset is but will never admit it#so instead they utterly despise each other#Would this technically make Ozai and Zuko cinematic parallels as well????#because oh boy that would be ironic and messy#I don’t know why this turned into a character study of Iroh and the fire nation royal family but oh well#iroh#ozai#aang#zuko#azula#atla#avatar the last airbender

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Lights of Treasure Island

For the past few years, I've been living on a barrier island named Anastasia. A sandy, sleepy, slow place, just off the coast of our nation's oldest city, Anastasia Island features tall palm trees and gorgeous beaches, along with excellent sushi and a surprisingly active arts scene. Its most splendid attraction, though, is an old lighthouse, one striped with a black and white spiral and crowned by a bright red lamphouse. It towers commandingly over the dunes, casting a long beam that can be seen from nearly anywhere in town.

I've always liked lighthouses. In days of old we set these magnificent lanterns on the edge of the sea, to guide sailors through dark and treacherous waters, to show them the way home. Lighthouses represent so many things we need: safety, comfort, reliability, navigation. But in my mind, these structures hold the magic of candles, the magic of illumination itself. When we speak of enlightenment, we may be speaking specifically of rationality and discovery, but we are also conjuring images of light prevailing over darkness. And in this way the lighthouse emerges as a powerful symbol of the spirit.

This February, for my 47th birthday, I explored the Outer Banks of North Carolina, where I saw several amazing lighthouses. Impressive as they were, I did not think they quite compared with the singular majesty of the structure that stands on Anastasia Island. After a harrowing return journey, one in which I drove with no working alternator (and sometimes without headlights or windshield wipers) through nearly 700 miles of tornadic thunderstorms, I felt the most profound relief when I finally crested the peak of the SR-312 bridge, which connects my island to the mainland, and I saw those familiar black and white stripes in the distance, signaling that I had made it home. Less than half a year later, my feelings about this special lighthouse of mine would be forever changed by a chance encounter.

Just under two months ago, I received a brief and rather unremarkable message from a stranger on Scruff, a queer dating platform that I use. One might charitably call Scruff "a social club for discerning gentlemen" ... it appeals to men who are hirsute, meaty, perpetually horny, and even a few of us freaks who defiantly straddle the line between "butch" and "nancy". Since this man's profile didn't really offer all that much information, and his one available picture wasn't particularly compelling, I promptly tucked his message away and forgot about it, and went for my customary sunset walk on the beach.

I live exactly one mile from the southern boundary of a state park, which offers a four-mile stretch of pristine dune habitat, completely undeveloped and sparsely occupied. The only man-made objects in sight are a few empty lifeguard stands, the city's sightseeing pier, a radio antennae, and our lighthouse. Dolphins gather here, their dorsal fins rising and falling between the breakers. Squadrons of pelicans fly in tight formations, gliding only a few feet above the water's surface. Terns and sea turtles nest in its sands, and I've found many shark teeth among the sea shells and ghost crab burrows. This is a special place, a holy place, and I've made a daily ritual of enjoying its cloudscapes and crepuscular glow as I explore the edge between land and sea.

After a pleasant stroll, maybe an hour or so of blissful meditation, I turned around and started heading back towards my car when I caught sight of a man who had just walked out of the water and was now drying himself off. We locked eyes.

He was the most beautiful man I had ever seen. Arrestingly beautiful, the kind of handsome that stops you dead in your tracks. I just kind of gulped for a second, and then walked right up to him, with an audacity that I didn't even know I possessed, turned on every damn bulb in my Christmas tree, and murmured, "Hi!", making the word shimmer like tinsel. In a short amount of time, I learned that he was a Russian artist, born in St. Petersburg but living in Moscow. I had met him during a brief pause on his long drive from Jacksonville to Key West; he had only intended on stopping in St. Augustine long enough to explore our old Spanish fort and take a swim on our nicest beach. He possessed a keen intellect, a quick wit, and a laudable command of English. As we spoke, he kept giving me flashes of the most mischievous smile, and so when I finally asked him what he was grinning about, he revealed that he was the same man who had messaged me earlier. This came as a surprise, for I hadn't recognized him at all ... I had only been drawn in now by his gorgeous movie-star looks, the undeniable sex appeal of his dripping wet body, and some weird sense of destiny.

We talked. We talked some more. We went to dinner. And then he stayed for the better part of three days.

In my bed, we enjoyed the most astonishing kind of communion. Our nights and mornings were filled with such tenderness ... soft eyes, soft caresses, fearlessly sustained gazes, the kind of kisses that tell a hundred little stories. One by one, various secrets were brought to light. We shared toe-curling carnality, thunderous climaxes, an unalloyed and unembarrassed intimacy. We shared joy.

On our second day together, I took him to the top of Anastasia Island's lighthouse. We lingered on each landing to kiss and giggle, and our embraces grew more intense. We felt a stronger and stronger pull towards one another. I knew that this was more than just a simple infatuation. By the time we reached the lantern's round balcony, and stepped out together onto the most spectacular view of St. Augustine, I knew that I was falling in love.

I don't blame you for rolling your eyes at this. You may, in your justifiable cynicism, think it ridiculous for a man to utter such a powerful phrase within such a short time. But if you've ever known me, you've come to recognize by now my considerable capacity for love. My passions and appetites may rise to the surface with little interference, and will I admit some recklessness in how I've invested my energies, but I am no fool. I am neither naïve nor desperate. And I can say in all sincerity that what we felt then was, at least for a short while, genuine love.

From the top of the lighthouse we could see everything. The old downtown, with its mixture of colonial and Spanish Renaissance buildings. The Matanzas River, named for the 1565 massacre of shipwrecked Huguenots, separating my island from the mainland. The harbor of St. Augustine, crowded with sailboats and pleasure craft, a forest of masts. And then the sea, blue and inviting, the sea that would soon separate us. We held each other tightly and looked upon the Atlantic together, casting our dreams towards the horizon, into this vista of seemingly endless possibility and hope.

On our last night together, we took a naked midnight swim in my pool, which is lit from above by a row of blue lights. A light and warm rain fell on our heads as we twined our legs underwater, and our ardor cast a web of rippling refractive patterns on the pool's concrete bottom. He looked me in the eyes, kissed me with the utmost gentleness, and formally invited me to come stay with him in Moscow. I accepted with my new magic word, "Да."

The following morning, our parting was so sweet, and so warm. We solidified our promise to be reunited. He drove down to Key West, enjoying a music playlist I assembled for him, and then he flew up to New York for a week's visit with old friends. After he returned to Moscow, we embarked on a passionate long-distance affair via telephone and social media apps.

I plunged right away into the Russian language, practicing for hours a day, rediscovering my knack for linguistics. I bought books on the cities of Moscow and St. Petersburg, books on Russian verbs, flashcards, a portable dictionary. I subscribed to online learning programs, put apps on my phone, read up on the country's history. I was all in, bringing every available bit of my enthusiasm, work ethic, and inventiveness to the challenge. Every day, I would send him sweet little videos or text messages ... sharing good news, conveying small but significant events of my daily life, showing off my rapidly accelerating grasp of Russian. I sent him notes of encouragement, pictures of me looking my cutest, small but enjoyable details of my life on Anastasia Island. I sent him a short clip of the black skimmers that sliced back and forth across the thin swash of the surf, their beaks dipping into half an inch of water. I sent him pelicans, beach crabs, waves, paintings, difficult words, idioms, cute terms of venery, sunsets, clouds, kisses, evidence of my changing body. I sent him love, every day. "каждый день," I promised him, placing my hand on my heart, "каждый день." Every day.

My love deepened by the hour. I know this is going to sound so gushy and gross, but I really pushed the lighthouse metaphor pretty hard, calling myself "твой смотритель маяка" or "your lighthouse keeper". I meant this in all sincerity, without a drop of bathos or schmaltz. Our time atop the lighthouse was sacred to me. I promised him that I would keep its light burning bright.

Over time, however, things shifted. As my interest grew, his began to dwindle. He sent less and less of himself, slowly removing from our conversation his humor, his sexuality, his warmth, his trust. It was like seeing a fully assembled jigsaw puzzle get lifted into the air, and watching all the pieces falling out ... at first only a few at a time, then more and more, until there was only a jagged perimeter where there had once been a lovely picture.

The nadir came when he lost his temper with me over my visa. I was confused about the process, as the Russian consulate and other sources were providing patchy and often conflicting information, and his own explanations changed from day to day. During our last video chat, I asked one too many questions, and he snapped. He rolled his eyes, effectively called me stupid and childish, and hung up on me three times. My many attempts at reconciliation were completely rebuffed. It was both baffling and extraordinarily painful.

Two days after our fight he was in a terrible car accident, one from which he miraculously escaped unharmed. He posted on social media an impassioned paragraph about the event, and how it drew into sharp focus all the love he had in his life, how he felt that he wasn't deserving of such love, how grateful he was for his friends. Yet instead of contacting me, inviting me into this experience, or trying to repair our frayed connection, he spent his evenings logging back into Scruff, the aforementioned dating app. He continued to ignore me, choosing instead to pursue (or perhaps refresh) other opportunities. I tried in vain to reach him, to restore our bond, but was met with only the most chilling silence.

How had I been so wrong? Had my desire devolved into mere obsession, albeit one artfully disguised as love? Had my zeal somehow suffocated him? The irony for me was that this disastrous affair unfolded during a period of rapid and positive transformation. In the space of the last seven months, I'd already changed my diet, fixed my teeth, joined a gym, paid off a chunk of my debt, reorganized my home office, purchased a standing desk, resumed my daily beach walks, started seeing both a psychiatrist and a therapist. My relationship to my body was improving, I was working at a higher level of professional responsibility, gaining new clients, writing my fourth novel, and churning out the finest paintings of my career. A recent experience with ayahuasca had given me valuable insights into my adulthood. It seemed only right that this Russian should be the cherry on my sundae, a prize I had been working so hard to deserve.

And so, after admitting my own disenchantment, I surrendered. Reeling from an overwhelming feeling of loss, I wrote him a heartfelt letter in Russian, one in which I explained the hurt his indifference was causing me. I poured a lot of benevolent energy into this letter. And then I said to him the saddest word I've learned in Russian, "Прощай", which is the type of goodbye you use when you think you are not likely to see someone again. It translates, literally, into "forgive me."

Here is the letter I wrote to him, translated into English:

***

"V_____, beautiful V____:

Okay. I give up.

Your silence gave me a very clear and very painful answer. You have been entrusted with something rare and beautiful, and you have shown that you do not want it. So now it's gone.

I'm sorry my heart bored you so much. I will no longer annoy you with my desires.

The love that I offered you ... pure and strong, given without demands or jealous limitations ... does not come often.

It pains me to realize that you do not appreciate what I have tried to give you. It is even more painful to realize that I may have aggravated the situation with my zeal. But the distance that you put between us is your choice, and I must respect that.

It seems that the epiphany you experienced in the car accident, the moment you thought of all the love in your life, did not include my love for you. Your priorities are yours, and I accept that. But you almost died yesterday, V_____. And instead of choosing to bond with a man who cares about you so much, your focus shifted to Scruff. Your indifference is so obvious now. Please do not say anything ugly or cruel in response. There is already enough sorrow on my island. I feel both grief and embarrassment, but not anger. I've always wanted the best for you, and it's still true.

I sincerely wish you a long and happy journey. I hope you enjoy many successes and find many pleasures. I hope you stay healthy. I hope the man you choose deserves your best gifts. I hope you find a better lighthouse. I must direct my light now to those who are really looking for it. So now I must tell you the saddest word that I have learned in your language.

Goodbye."

***

Please allow me now to rewind a few years, and tell a correlative story.

In the autumn of 2019, during a period of intense sadness and frustration, I fled from Anastasia Island and drove impulsively across the state to the Gulf Coast. I didn't have a clear destination, I didn't pack enough clothes or supplies, and I was so blinded with tears and unexpressed rage that I didn't know where I was, or even care much about where I might land. While getting lost somewhere in the vicinity of St. Petersburg, I glanced at a map, dragged my finger along the squiggly coastline, saw the name Treasure Island, and thought, "That's gotta be the place."

I don't know what I was expecting to find there. Something about the name sounded so exciting, so exotic. And as the evening wore on, my anticipation grew. I thought, in my desperation, that everything would be all right once I got to Treasure Island. Over the next few hours, I convinced myself that I'd finally feel good again in such a place, that my pain and confusion would certainly evaporate once I reached this safe haven. I'd check into a nice hotel room, preferably one with 300 thread-count sheets and a coffee maker, and I'd dream about pirate ships and gold doubloons, and when I opened my eyes and yawned and stretched against the sun-dappled pillows my life would basically feel like a commercial for some bougie brand of almond milk. When I arrived, however, I was deeply disappointed to see another narrow stretch of high-rise hotels, littered beaches, rank seaweed, and greyish-brown water. I found the cheapest hotel room around, one of the few remaining vacancies on the shore, and there I found neither crisp bedsheets nor good coffee. The view from my balcony, however, was utterly amazing: I could see not only a broad curving swath of the beach, but also a glow of distant resort hotels, some of them reflected in the waves. It was strangely romantic, seeing these twinkling lights ... red, gold, green, blue ... and their silent conversation with the stars, a dialogue of jewels above the warm churning waters of the Gulf. But it wasn't the salvation I had been hoping for.

When I got up the next morning, I was still facing the same problems, the same irritations, the same heavy sorrows. Treasure Island would not, could not, rescue me from myself. So I drove back home to my own island, back to my lighthouse, and was relieved to discover that it was in fact even more stirring than I had remembered. During my absence Anastasia Island had become a magical and restorative place, quite different than the one I had left only days before.

What I should have learned back then, but have only come to realize now, was this: I didn't need to travel to a distant island of treasure and twinkling stars, for my own island already had plenty of both. I didn't need to seek the incandescence of a handsome man to light my way, as my own inner flame was at last beginning to shine without the shutters of inhibition or profligacy.

I am now recalling my disappointment with Treasure Island, while concurrently considering my grief over the Russian. At first, I wanted to hate him for his carelessness, for how he squandered my gifts. But I don't hate him. Not really. There's no need to wring my hands any further over his callousness. I don't even mourn his absence anymore. My mood has shifted today, and I no longer choose to see this abortive liaison as being so devastating. For I know, deep down, that the failure here was not really mine. I am not a loser for investing myself unreservedly in someone who could not fully appreciate me, nor I am not the weaker man for feeling injured. I will not be permanently depleted for having offered all that kindness to an undeserving recipient, as my wellspring of love remains inexhaustible.

I tried to share my lighthouse with the Russian. But he did not recognize how special it really was, and he declined to follow its beacon to a rewarding harbor. And thus, our romance was destroyed, and his memory became just another broken boat littering the shallows.

I have seen so many ruins in my years: bad relationships, lousy jobs, soured opportunities. My life story reads like a ledger of dashed hopes. It seems sometimes that both the island I occupy and the more elusive island I am eternally seeking are surrounded by shipwrecks. Yet the lighthouse of my spirit still stands, sturdier and stronger than ever. The waves may batter its bricks, salt may scour its surfaces, it may occasionally groan under its own weight ... but it will not crumble, it will not fail, and even in the darkest of hours this lamp of mine will continue to shine: bright, focused, undiminished.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Thinking Positive

Disclaimer: Doom Patrol and associated characters are the creative property of DC Comics

Warnings: internalized homophobia, depression

Rating: T

Synopsis: In order to heal, Larry will have to work on being more positive. It’s a long and difficult journey.

A/N: I watched Doom Patrol last year and to say I loved it would be a major understatement. But the thing that took me by surprise the most was just how meaningful Larry Trainor’s story was to me, someone who also grew up surrounded by a lot of homophobia and feels like openly living with pride is still a difficult and ongoing struggle into my adulthood.

And with global quarantine being what it is, I’ve had a lot of strange and curious time on my hands to work on things so far as mental health is concerned. And it’s had me thinking a lot about how sometimes negativity and cyncism is a coping mechanism that’s easy to use but damaging in the long run. I tend to take that perspective away from Larry’s story rather than the way the show sometimes dismisses valid personal fears of outing and shames closeting. So this rambling story came barreling out of me. I hope it makes some sense.

Larry dismissed himself from dinner with the rest of Doom Manor’s residents.

It didn’t take much more than some dismissive words on his part, easily ignored over the rambunctious antics of Jane and Cliff, or the attempts to quell said antics by Vic and Flex. Rita was the most difficult to escape, considering Larry was her main outlet for commentary, but even she was willing to let him go when he stressed that he was tired.

He had tired rather easily over the last few months, and Rita knew why even more than the others.

In some ways, it was like therapy. In other ways, it was like torture. But that had always been Larry’s dilemma. He was rarely allowed to have one over the other.

Even before the Negative Spirit melded to his very soul.

When Larry attempted to frame his fears in less selfish designs, he framed his need for more energy as being there for the others. Cliff needed to have someone counter his gutsier instincts. Jane’s sarcasm needed someone equally verbose in it. And Rita, of course, counted on Larry’s counsel more than anyone’s. But it was easier, lately, with each other, with the others like Vic and Flex and even Dorothy, young in appearance and still finding her place as she was.

Besides all that, Larry had made a promise to himself that he wasn’t going to blame his reluctance on others anymore.

Which led to the closing of the thick lead door behind Larry. The slow removal of his protective bindings as the Richter scale crackled in the decompression port. The daily walk through his metal room and his radiation proofed furniture.

It was funny to think that his room had changed so little from the minimal aesthetic it had when the Chief first offered him a place nearly half a century ago. Funny, but also uncomfortable. Like it was wrong and stupid of him, but it had been so long that it would be weirder if Larry attempted to make any big changes.

He laid down on his bed and made himself comfortable, his hands rested over his chest, close to his heart.

Larry gazed at the ceiling and felt the rumbles deep in his body which let him know that the spirit was aware of what time it was.

“Hey there, buddy,” Larry said, voice low and tired. “It’s that time again. The one where I try to get stuff off my chest.” His hands tapped rather nervously over his shirt. It was light enough that the nerve damage kept the tips of his fingers from truly feeling more than the slight pressure of it. “Literally.”

For the life of him, Larry couldn’t figure out why he always started out so nervous and uncomfortable every day.

Then again, Larry had lived his entire life nervous and uncomfortable. It was hard to break habits formed over a century, he supposed.

“Okay, well, here goes nothing,” Larry sighed, closing his eyes and preparing himself. Idioms aside, it did not feel like nothing, it felt like everything every time.

“Start from the top? Positive things?” Larry asked out loud. With his eyes closed, the rumble from the negative spirit felt even stronger, more enthusiastic perhaps. “Of course, you eat those up. Alright.

”Today my azaleas began to bloom early. I got some rhododendron seeds in the mail. Chief is offering to get me a new greenhouse on the property, to expand things. Dorothy made me a flower crown. She didn’t use any of my flowers. I think she used paper and then with her, ah, powers turned them into real flowers. Usually, her using her powers is disturbing, like the whole thing with the puppets. But this was, you know, cute. I liked it. I mean it’s quicker to use a Snapchat filter, but…”

The negative spirit rumbles more abruptly. It gives Larry a sense of warning or disapproval.

“I know, I know, staying positive,” he sucks in a deep breath. It’s the sort of deep, lung filling breath that he’s only capable of thanks to the negative spirit’s possession of him. Their temporary separation reminded him of that. That, however, was an unspoken positive between them.

“I tried a new recipe, everyone seemed to enjoy it,” Larry continued. “It’s curried roasted eggplant with smoked cardamom and coconut milk.” He couldn’t resist the huff of a laugh that escaped him as a result. “Sheryl would’ve never believed it.”

There was a numbness that spread out from his chest. It was an overwhelming sense, but Larry considered it a good development.

He and the Negative Spirit both took a long time to have a response to his ex-wife being invoked that was anything other than overwhelmingly negative.

Still, it was best to trade subjects and not linger on old regrets. As natural as it was for Larry to do that.

“With all the new residents, this place has really gotten lively,” he said, arching his neck back more comfortably on the pillow. “I know I’ve let you out a few times to explore that for yourself, but you probably miss a lot of the little things.”

A gentle hum radiated out from his chest. Positive? Affirmation? Larry was still deciphering the finer bits.

“It’s good for all of them,” Larry concluded. “They fit together well. Well, not fit. The whole point of this place is that fitting is…”

He trailed off, catching his own turn toward negativity long before the spirit had a chance to disrupt him.

“It’s nice, seeing how meaningful it is for Cliff and Jane to have someone…” Larry scowled and lifted up one of his hands from his chest to scrub at his face. Doom Manor was so hard to contextualize sometimes. “Not younger. She’s older than all of us. Smaller? It’s nice to see Cliff and Jane both have someone smaller to look out for. Daughter. Little sister. However it goes.” He lowered his hand down to his side, away from his chest where he’d more acutely feel the rumbles of the Negative Spirit’s responses. “Did I mention she made me a crown? That was nice.”

Larry lapsed into silence, his eyes unfocused as they stared at his ceiling and past it toward all the feelings and regrets of a long life.

He never felt the need to regain a sense of fatherhood like Cliff was haunted by. But he had been a father, too. He had been a father of two.

And he never saw either of them again. Never tried.

Sheryl had taken them away to a better life. Maybe she remarried, to a man who could love her the way she deserved to be love. Maybe the boys got a father who could teach them all the things about being a man that were beyond Larry’s comprehension.

It probably would have been simple enough to find out, if Larry had asked questions or reached out.

But he hadn’t. He forfeited that part of his life, just like he had forfeited so much else.

In some ways, he hoped Sheryl had told the boys he had died. That way they never grew up wondering why Larry hadn’t reached out. So they didn’t have the accurate picture of what a coward their fearless flyboy father had been.

There was no telling how much time he was prepared to spend down that path before his body jolted.

Not without warning, the Negative Spirit seized through Larry’s body with force and separated. His eyes rolled back into his head and everything went limp and dark.

When Larry woke with a gasp, he already knew what had happened, but he sat upon his bed all the same and grabbed at his head in frustration.

“Look! This is part of it!” he yelled toward his chest. His heart was racing, equal parts the Negative Spirit’s pulsing and Larry’s own anger. “I know, I know we need to work on being positive, but you got yourself paired with one of the most naturally negative sons of bitches on the planet. This wasn’t just about you, alright? We’ve talked about this before. I was born negative. I’ve been looking at the dark side of things since I was seven years old and that’s not changed in a century. You have to work with me here if we’re going to get anywhere.”

He was answered only by the creaks and groans of Doom Manor.

“I’m allowed to remember bad things, you know,” Larry continued to argue. “Maybe you’re right. Maybe everyone’s right and I’ve been letting them rule me. I-I know you’re all right about that. But completely avoiding and ignoring negative things doesn’t keep them from existing. It’s dangerous. And it’s wrong.” His frown deepened. “I’d be more of a monster than I ever dreamed myself being, if I thought anything less than the fact that the boys didn’t deserve what they had to go through. Alright? They may be old men now, but they are still my boys. And they deserved not losing everything they ever knew. And they didn’t deserve all the secondhand anxiety and paranoia from me. Those are just facts. Even if they were unavoidable.”

Finally, the Negative Spirit hummed again.

“What? That’s what you wanted from me?” Larry asked, splaying his hands against his chest to feel the rumble more. “You wanted me to say it was unavoidable? Look, how many times do I have to learn these lessons until you’re satisfied?”

There was quiet once more.

“If it’s until I believe them,” Larry’s voice softened to a murmur, “we’ll be doing this every day for a long time. Maybe until the day I finally die. And even then it might not be enough. You know that, right? I’m pretty majorly fucked in here, and a good amount of that came with the package before you joined in, buddy.”

The hum was unmistakable that time, Larry felt it through his core.

Okay.

“Okay,” Larry repeated, laying back down. “Stop having fits the second we go into some territory you don’t like, I’ll try to respond quicker.”

There was another unmistakable hum through his chest.

“If you’re wondering about the conversation with Rita about Flex, then you probably were already aware of most of it,” Larry snorted. “I’m coming up on one hundred years old, I don’t want to repeat what I said to my best friend about someone else’s quads.” He tossed his head a little from side to side and then sighed. “They are nice, though. And admitting it out loud didn’t light me on fire, so, who knows. Maybe being gay does get easier with practice.”

That seemed to satisfy the spirit, and it did Larry, too.

Small victories — victories so small that a previous version of himself might have argued they weren’t worth celebrating, not for the amount of time it took for him to get to that point. But he felt the accomplishment all the same.

There were so many regrets and so much fear in his life that was still there, and he still didn’t believe that erasing all of it was the fully responsible or realistic thing to do.

But he could make himself lighter, in whatever small increments he could. And that was surely worth the battle alone.

39 notes

·

View notes

Text

The specificity of artistic languages-as voiced by Glenn Gould and Joseph Brodsky

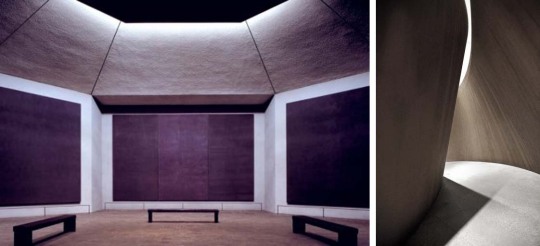

M. Rotchko, Huston, 1971 and R. Serra, Venezia, 2005

It is a pleasure to lend an ear to two megaphones of the caliber of the two artists cited to get at that colossus (of Rhodes?) that bears the name of Marcel Duchamp. It’s been exactly 34 (1) years since I started my battle, but my bullets bounced off a rubber wall rebounding to the sender. I have to thank heaven if I have come out unscathed so far. The thread of the discourse of the two unravels very clearly in different fields that never touch visual art, but it is also valid for this. Substantiated by very few others (including Susan Sontag and Franco Vaccari), it cannot be dismissed as biased: which, if one speaks of music and the other of poetry?

G. de Chirico, 1913, and Pontormo in S. Felicita, Firenze,1526/27

So let’s keep in mind what JB and GG say about their fields, but let’s ask ourselves why there should be a different discourse in that of visual art. If we give the etymological meaning to semantics and not that of the expression of its content, every interpretation, as Sontag (2) states, is a usurpation, a grand deception. Art cannot exhibit any semantic content separate from its form, because it is exactly this that conveys it. The ambiguity linked to the meaning does not interest us, but the mystery of form does (3). If a plethora of exegetes have strived, with good results for their profit, to give an explanation to the convoluted arguments of the “Frenchman”, this does not justify forgetting that the visual language possesses an autonomy of signs that do not preclude the past and are in search of a future that has nothing to do with the lingua franca, even that of the most distinguished critics, one that does not suffer from a translation. Even mine right now: I don’t pretend to do poetry.

G.B. Tiepolo,Venezia,1757 and Gordon Matta, Paris, 1975

Mine is an effort of collation of arguments produced in the lingua franca by two true artists: each of their own words, carefully chosen by me, can be applied to the green of a Poet’s dream as to the Conical hole of Gordon Matta-Clark or Tiepolo, to the pink of Santa Felicita (or to the Hand that indicates it; who? the Pontormo or Giovanni Anselmo?) as to the black of the Rothko Chapel, to the unbalanced Spiral space of Serra as to the agitation of Erasmus of Narni (who is able to curb it in its stillness?). There are no borders in art, nothing sets and often the classics are revived.

Gordon Matta, NY, 1974 and Federico De Leonardis, Peccioli (PI),1990

Here is the series of promised quotes. I’ll start with Gould. After pointing out Bach’s indifference if not unwillingness to write for a given keyboard instrument, Gould uses terms such as smug, silken, legato spinning resource for his own Steinway. This says a lot about the attention to the characteristics of one’s own expressive language:

Giovanni Anselmo, Pointing hand

Bach’s compositional method, of course, was distinguished by his disinclination to compose at any specific keyboard instrument. And it is indeed extremely doubtful that his sense of contemporaneity would have appreciably altered had his catalogue of household instruments been supplemented by the very latest of Mr. Steinway’s “accelerated action” claviers. It is at the same time very much to the credit of the modern keyboard instrument that the potential of its sonority—that smug, silken, legato-spinning resource can be curtailed as well as exploited, used as well as abused.

I suspect I may have unwittingly engaged in a dangerous game, ascribing to musical composition attributes which reflect only the analytical approach of the performer. This is an especially vulnerable practice in the music of Bach, which concedes neither tempo nor dynamic intention, and I caution myself to restrain the enthusiasm of an interpretative conviction from identifying itself with the unalterable absolute of the composer’s will. Besides, as Bernard Shaw so aptly remarked, parsing is not the business of criticism.

As for the reasons for his abandonment of concert halls for recording ones:

Well, you see, Bruno, I don’t really enjoy playing any concertos very much. What bothers me most is the competitive, comparative ambience in which the concerto operates. I happen to believe that competition rather than money is the root of all evil, and in the concerto we have a perfect musical analogy of the competitive spirit. Obviously, I’d exclude the concerto grosso from what l’ve just said.

Marliave’s mention of “the intimate and contemplative appeal to the ear“ illustrates an approach to these works based upon philosophical conjecture rather than musical analysis. Beethoven, according to this hypothesis, has spiritually soared beyond the earth’s orbit and, being delivered of earthly dimension, reveals to us a vision of paradisiacal enchantment. A more recent and more alarming view shows Beethoven not as an indomitable spirit which has overleapt the world but as a man bowed and broken by the tyrannous constraint of life on earth, yet meeting all tribulation with a noble resignation to the inevitable. Thus Beethoven, mystic visionary, becomes Beethoven, realist, and these last works are shown as calcified, impersonal constructions of a soul impervious to the desires and torments of existence. The giddy heights to which these absurdities can wing have been realized by several contemporary novelists, notable offenders being Thomas Mann and Aldous Huxley.

If you are particularly fond of the last works of Strauss, as I am, it is essential to acquire a more flexible system of values than that which insists upon telling us that novelty equals progress equals great art. I do not believe that because a man like Richard Strauss was hopelessly old-fashioned in the professional verdict, he was, therefore, necessarily a lesser figure than a man like Schoenberg who stood for most of his life in the forefront of the avant-garde. If one adopts that system of values, it brings about the inevitable embarrassment of having to reject, among others, Johann Sebastian Bach as also being hopelessly old-fashioned.

His opinion on the relationship between the tastes of the time and the eternity of language see the following fragments:

The generation, or rather the generations, that have grown up since the early years of this century have considered the most serious of Strauss’s errors to be his failure to share actively in the technical advances of his time. They hold that having once evolved a uniquely identifiable means of expression, and having expressed himself within it at first with all the joys of high adventure, he had thereafter, from the technical point of view, appeared to remain stationary—simply saying again and again that which in the energetic clays of his youth he had said with so much greater strength and clarity. For these critics it is inconceivable that a man of such gifts would not wish to participate in the expansion of the musical language, that a man who had the good fortune to be writing masterpieces in the days of Brahms and Bruckner and the luck to live beyond Webern into the age of Boulez and Stockhausen should not want to search out his own place in the great adventure of musical evolution. What must one do to convince such folk that art is not technology, that the difference between a Richard Strauss and a Karlheinz Stockhausen is not comparable to the difference between a humble office adding machine and an IBM computer?

The great thing about the music of Richard Strauss is that it presents and substantiates an argument which transcends all the dogmatisms of art—all questions of style and taste and idiom—all the frivolous, effete preoccupations of the chronologist. It presents to us an example of the man who makes richer his own time by not being of it; who speaks for all generations by being of none. It is an ultimate argument of individuality—an argument that man can create his own synthesis of time without being bound by the conformities that time imposes.

But one last examination of this hypothetical piece: let us assume that instead of attributing it to Haydn or to any later composer, the improviser were to insist that it was a long-forgotten and newly discovered work of none other than Antonio Vivaldi, a composer who was by seventy—five years Haydn’s senior. I venture to say that, with that condition in mind, this work would be greeted as one of the true revelations of musical history-a work that would be accepted as proof of the farsightedness of this great master, who managed in this one incredible leap to bridge the years that separate the Italian baroque from the Austrian rococo, and our poor piece would be deemed worthy of the most august programs. In other words, the determination of most of our aesthetic criteria, despite all our proud claims about the integrity of artistic judgment, derives from nothing remotely like an “art-for-art’s-sake” approach. What they really derive from is what we could only call an “art-for-what-its-society-was-once-like” sake.

The deficiencies of this argument arise from the fact that its proponents simply cannot tolerate the idea that the participation in a certain historical movement does not necessarily impose upon the participant the duty to accept the logical consequences of that movement. One of the irresistibly lovable facts about most human beings is that they are very seldom willing to accept the consequences of their own thinking. The fact that Strauss deserts the general movement of German expressionism (presumably, in Rosenfeld‘s terms, the embodiment of “Nietzsche‘s modernism”) should not be more disturbing than the fact that the unquestioned innovator Arnold Schoenberg found it extremely difficult in his later years to fulfill the rhythmic extenuations of his own motivic theories. The fact is that above and beyond the questions of age and endurance, art is not created by rational animals and in the long run is better for not being so created.

It would be most surprising if the techniques of sound preservation, in addition to influencing the way in which music is composed and performed (which is already taking place), do not also determine the manner in which we respond to it. And there is little doubt that the inherent qualities of illusion in the art of recording those features that make it a representation not so much of the known exterior world as of the idealized interior world-will eventually undermine that whole area of prejudice that has concerned itself

with finding chronological justifications for artistic endeavors and which in the post-Renaissance world has so determinedly argued the case of a chronological originality that it has quite lost touch with the larger purposes of creativity.

Whatever else we would predict about the electronic age, all the symptoms suggest a return to some degree of mythic anonymity within the social-artistic structure. Undoubtedly most of what happens in the future will be concerned with what is being done in the future, but it would also be most surprising if many judgments were not retroactively altered because of the new image of art. If that happens, as I think it must, there will be a number of substantial figures of the past and near past who will undergo major reevaluation and for whom the verdict will no longer rest upon the narrow and unimaginative concepts of the social-chronological parallel.

And so it seems to me a great mistake to read into the fantastic transition of music in our time a total social significance. Undeniably, there do exist correlations between the development of a social stratum and the art which grows up around it, just as the public manner of early baroque music related to some degree to the prosperity of a merchant class in the sixteenth century; but it is terribly dangerous to advance a complicated social argument for a change which is fundamentally a procedural one within an artistic discipline.

Of course, the early propagandists for atonality pointed with a good deal of pride to the fact that the movement toward abstract art began at almost exactly the same time as atonality, and there are certain comfortable parallels between the careers of the painter Kandinsky and the composer Schoenberg.

But l think it is dangerous to pursue the parallel too closely, for the simple reason that music is always abstract, that it has no allegorical connotations except in the highest metaphysical sense, and that it does not pretend and has not, with very few exceptions, pretended to be other than a means of expressing the mysteries of communication in a form which is equally mysterious.

The figure of Schoemberg outlined by the writings of G is emblematic for understanding the linguistic work of a great composer and his responsibility in the detachment of cultured music from popular music:

But the odd thing about it was that with this oversimplified, exaggerated system Schoenberg began to compose again; and not only did he begin to compose: he embarked upon a period of about five years which contains some of the most beautiful, colorful, imaginative, fresh, inspired music which he ever wrote. Out of this concoction of childish mathematics and debatable historical perception came an intensity, a ioie de vivre, which knows no parallel in Schoenberg‘s life. How could this be, then? By what strange alchemy was this man compounded that the sources of his inspiration flowed most freely when stemmed and checked by legislation of the most stifling kind? I suppose part of the answer lies in the fact that Schoenberg was always intrigued by numbers and afraid of numbers and attempting to read his destiny in numbers –and, after all, what greater romance of numbers could there be than to govern one’s creative life by them? I suppose part of it was due to the fact that after fifteen years awash in a sea of dissonance, Schoenberg felt himself to be on firm ground once again. Still another part of it is certainly that all music must have a system, and that particularly in those moments of rebirth such as Schoenberg had led us into, it is much more necessary to adhere to the system, to accept totally its consequences, than at a later, more mature stage of its existence.

I think there can be no doubt that its fundamental effect has been to separate audience and composer. One doesn’t like to admit this, but it is true nonetheless. There are many people around who believe that Schoenberg has been responsible for shattering irreparably the compact between audience and composer, of separating their common bond of reference and creating between them a profound antagonism. Such people claim that the language has not become a valid one for the reason that it has no system of emotional reference that is generally accepted by people today. Certainly concert music of today—

that part of it, at any rate, which owes a great deal to the Schoenbergian influence—plays a very small part in the life of many people. It cannot by any means claim to excite the curiosity that was generally aroused by significant new works fifty or sixty years ego. One must remember that at the turn of the century, any new work by a Richard Strauss or a Gustav Mahler or a Rimsky-Korsakov or a Debussy was a major event not only for the cognoscenti but for a very large lay audience as well.

No matter how little interest there may be in the more significant developments of music in our time, I think that there is little doubt that there are some areas in which the vocabulary of atonality—using this term now in a collective sense—has made quite an unobjectionable contribution to contemporary life. It has done this particularly in media in which music furnishes but a part—operas, to a degree (if you can consider styling Alban Berg’s Wozzeck a “hit”), but most particularly in that curious specialty of the twentieth century known as background music for cinema or television. If you really stop to listen to the music accompanying most of the grade-B horror movies that are coming out of Hollywood these days, or perhaps a TV show on space travel for children, you will be absolutely amazed at the amount of integration which the various idioms of atonality have undergone in these media.

Until here: Glenn Gould. Let us now turn to quoting Brodsky. The following fifteen lines (taken from On Grief and Reason) represent an eloquent summary of his thinking on art in general and poetry in particular, as well as on the meaning of the word “language”. Below I have collected other fragments (also taken from Less Than One) that specify its depth and richness. The only fundamental difference with the visual arts is on the affirmation of the inalienability of the word to the semantic value (unfortunately), but with the specification that this does not apply to the other arts.

For poetic discourse is continuous; it also avoids cliché and repetition. The absence of those things is what speeds up and distinguishes art from life, whose chief stylistic device, if one may say so, is precisely cliché and repetition, since it always starts from scratch. It is no wonder that society today, chancing on this continuing poetic discourse, finds itself at a loss, as if hoarding a runaway train. I have remarked elsewhere that poetry is not a form of entertainment, and in a certain sense not even a form of art, but our anthropological, genetic goal, our linguistic, evolutionary beacon. We seem to sense this as children, when we absorb and remember verses in order to master language. As adults, however, we abandon this pursuit, convinced that we have mastered it. Yet what we’ve mastered is but an idiom, good enough perhaps to outfox an enemy, to sell a product, to get laid, to earn a promotion, but certainly not good enough to cure anguish or cause joy. Until one learns to pack one’s sentences with meanings like a van or to discern and love in the beloved’s features a “pilgrim soul”; until one becomes aware that “No memory of having starred I Atones for later disregard, / Or keeps the end from being hard”—until things like that are in one’s bloodstream, one still belongs among the sublinguals. Who are the majority, if that’s a comfort.

In that, it-life-differs from art, whose worst enemy, as you probably know, is cliché. Small wonder, then, that art, too, fail-s to instruct you as to how to handle boredom. There are few novels about this subject; paintings are still fewer; and as for music, it is largely nonsemantic. On the whole, art treats boredom in a self-defensive, satirical fashion. The only way art can become for you a solace from boredom, from the existential equivalent of cliché, is it you yourselves become artists. Given your number, though, this prospect is as unappetizing as it is unlikely.

Herein lies the ultimate distinction between the beloved and the Muse; the latter doesn’t die. The same goes for the Muse and the poet: when he’s gone, she finds herself another mouthpiece in the next generation. To put it another way, she always hangs around a language and doesn’t seem to mind being mistaken for a plain girl. Amused by this sort of error, she tries to correct it by dictating to her charge now

pages of Paradise, now Thomas Hard}-“s poems of 1912-13; that is, those where the voice of human passion yields to that of linguistic necessity—but apparently to no avail. So let’s leave her with a flute and a wreath wildflowers. This way at least she might escape a biographer.

Of course, when talking about the signs of the word (semanticity) one cannot avoid addressing the theme of the relationship between art and life:

Now, the purpose of evolution is the survival neither of the fittest nor of the defeatist. Were it the former, we would have to settle for Arnold Schwarzenegger; were it the latter, which ethically is a more sound proposition, we’d have to make do with Woody Allen. The purpose of evolution, believe it or not, is beauty, which survives it all and generates truth simply by being a Fusion of the mental and the sensual. As it is always in the eye of the beholder, it can’t he wholly embodied save in words: that’s what ushers in a poem, which is as incurably semantic as it is incurably euphonic.

In “Home Burial“ (Frost’s poem) it results is both. For every Galatea is ultimately a Pygmalion’s self-projection. On the other hand, art doesn’t imitate life but infects it. …

… This is a poem about languages terrifying success, for language, in the final analysis, is alien to the sentiments it articulates. No one is more aware of that than a poet; and if “Home Burial”

is autobiographical, it is so in the first place by revealing Frost’s grasp of the collision between his métier and his emotions. To drive this point home, may I suggest that you compare the actual sentiment you may feel toward an individual in your company and the word “love.” A poet is doomed to resort to words. So is the speaker in “Home Burial.” Hence, their overlapping in this poem; hence, too, its autobiographical reputation. …

… So what was it that he was after in this, his very own poem? He was, I think, after grief and reason, which, while poison to each other, are languages most efficient fuel—or, if you will, poetry’s indelible ink. Frost’s reliance on them here and elsewhere almost gives you the sense that his dipping into this ink pot had to do with the hope of reducing the level of its contents; you detect a sort of vested interest on his part. Yet the more one dips into it, the more it brims with this black essence of existence, and the more one’s mind, like one’s fingers, gets soiled by this liquid. For the more there is of grief, the more there is of reason. As much as one may be tempted to take sides in “Home Burial,” the presence of the narrator here rules this out, for while the characters stand, respectively, for reason and for grief, the narrator stands for their fusion. To put it differently, while the characters’ actual union disintegrates, the story, as it were, marries grief to reason, since the bond of the narrative here supersedes the individual dynamics— well, at least for the reader. Perhaps for the author as well. The poem, in other words, plays fate.

For poetic discourse is continuous; it also avoids cliché and repetition. The absence of those things is what speeds up and distinguishes art from life, whose chief stylistic device, if one may say so, is precisely cliché and repetition, since it always starts from scratch. It is no wonder that society today, chancing on this continuing poetic discourse, finds itself at a loss, as if hoarding a runaway train. I have remarked else-

where that poetry is not a form of entertainment, and in a certain sense not even a form of art, but our anthropological, genetic goal, our linguistic, evolutionary beacon. We seem to sense this as children, when we absorb and remember

For art is something more ancient and universal than any faith with which it enters into matrimony, begets children—but with which it does not die. The judgment of art is a judgment more demanding than the Final Judgment.

Rilke’s Orfeo gives him the cue to clarify his thought on art, which in addition to the close relationship with the meaning of death, arises precisely from the rubbish of life:

This economy is art’s ultimate raison d’être, and all its history is the history of its means of compression and condensation. In poetry, it is language, itself a highly condensed version of reality. In short, a poem generates rather than reflects.

For why should we empathize with him? Less highborn and less gifted than he is. we never will be exempt from the law of nature. With us, the journey to Hades is a one-way trip. What can we possibly learn from his story? That a lyre takes one farther than a plow or a hammer and anvil? That we should emulate geniuses and heroes? That perhaps audacity is what does it? For what if not sheer audacity was it that made him undertake this pilgrimage?

A man of my occupation seldom claims a systematic mode of thinking; at worst, he claims to have a system—but even that, in his case, is a borrowing from a milieu, from a social order, or from the pursuit of philosophy at a tender age. Nothing convinces an artist more of the arbitrariness of the means to which he resorts to attain a goal—however permanent it may be—than the creative process itself, the process of composition. Verse really does, in Akhmatova’s words, grow from rubbish; the roots of prose are no more honorable. …

… Art, generally speaking, always comes into being as a result of an action directed outward, sideways, toward the attainment (comprehension) of an object having no immediate relationship to art. It is a means of conveyance, a landscape flashing in a window—rather than the conveyance’s destination. “If you only knew,” said Akhmatova, “what rubbish verse grows from . . .” The farther away the purpose of movement, the more probable the art; and, theoretically, death (anyone’s, and a great poet’s in particular, for what can be more removed from everyday reality than a great poet or great poetry?) turns into a sort of guarantee of art.

The hierarchy between ethics and aesthetics further clarifies his thinking on the relationship between art and life. This applies to all the arts, as the discourse about what art language means also always applies to all:

On the whole, every new aesthetic reality makes man’s ethical reality more precise. For aesthetics is the mother of ethics. The categories of “good” and “bad” are, first and foremost, aesthetic ones, at least etymologically preceding the categories of “good” and “evil.” If in ethics not “all is permitted,” it is precisely because not “all is permitted” in aesthetics, because the number of colors in the spectrum is limited. The tender babe who cries and rejects the stranger who, on the contrary, reaches out to him, does so instinctively, makes an aesthetic choice, not a moral one.

Unlike life, a work of art never gets taken for granted: it is always viewed against its precursors and predecessors. The ghosts of the great are especially visible in poetry, since their words are less mutable than the concepts they represent.

In such an absence, art grows humble. For all our cerebral progress, we are still greatly subject to relapse into the Romantic (and, hence, Realistic as well) notion that “art imitates life.” If art does anything of this kind, it undertakes to reflect those few elements of existence which transcend “life,” extend it beyond its terminal point—an undertaking which is frequently mistaken for art’s or the artist’s own groping for immortality. In other words, art “imitates” death rather than life; i.e., it imitates that realm of which life supplies no notion: realizing its own brevity, art tries to domesticate the longest possible version of time. After all, what distinguishes art from life is the ability of the former to produce a higher degree of lyricism than is possible within any human interplay. Hence poetry’s affinity with–if not the very invention of—the notion of afterlife.

Poetry after all in itself is a translation; or, to put it another way, poetry is one of the aspects of the psyche rendered in language. It is not so much that poetry is a form of art as that art is a form to which poetry often resorts. Essentially, poetry is the articulation of perception, the translation of that perception into the heritage of language—language is, after all, the best available tool. But for all the value of this tool in ramifying and deepening perceptions-revealing sometimes more than was originally intended, which, in the happiest cases, merges with the perceptions—every more or less experienced poet knows how much is left out or has suffered because of it.

It would be false as well as unnecessary to try to divorce Platonov from his epoch; the language was to do this anyway, if only because epochs are finite. In a sense, one can see this writer as an embodiment of language temporarily occupying a piece of time and reporting from within. The essence of his message is LANGUAGE I5 A MILLENARIAN DEVICE, HISTORY ISN’T”, and coming from him that would be appropriate.

A great writer is one who elongates the perspective of human sensibility, who shows a man at the end of his wits an opening, a pattern to follow.

Burning books, after all, is just a gesture; not publishing them is a falsification of time. But then again, that is precisely the goal of the system: to issue its own version of the future.

Whether one likes it or not, art is a linear process. To prevent itself from recoiling, art has the concept of cliché. Art’s history is that of addition and refinement, of extending the perspective of human sensibility, of enriching, or more often condensing, the means of expression. Every new psychological or aesthetic reality introduced in art becomes instantly old for its next practitioner. An author disregarding this rule, somewhat differently phrased by Hegel, automatically destines his work—no matter what good press it

gets in the marketplace—-to assume the status of pulp.

But to clarify the undemocratic nature of the language, just these sketches taken from some of his most important essays are enough:

Herein, of course, lies arts saving grace. Not being lucrative, it falls victim to demography rather reluctantly.

For if, as we’ve said, repetition is boredom’s mother, demography (which is to play in your lives a far greater role than any discipline you’ve mastered here) is its other parent. This may sound misanthropic to you, but I am more than twice your age, and I have lived to see the population of our globe double. By the time you’re my age, it will have quadrupled, and not exactly in the fashion you expect. For instance, by the year 2000 there is going to be such cultural and ethnic rearrangement as to challenge your notion of your own humanity.

Starting with the authors mentioned above, some may find these notes maximalist and biased; most likely they will ascribe these flaws to their author’s own métier. Still others may find the view of things expressed here too schematic to be true. True: it’s schematic, narrow, superficial. At best, it will be called subjective or elitist. That would be fair enough except that we should bear in mind that art is not a democratic enterprise, even the art of prose, which has an air about it of everybody being able to master it as well as to judge it.

For poetic discourse is continuous; it also avoids cliché and repetition. The absence of those things is what speeds up and distinguishes art from life, whose chief stylistic device, if one may say so, is precisely cliché and repetition, since it always starts from scratch. It is no wonder that society today, chancing on this continuing poetic discourse, finds itself at a loss, as if hoarding a runaway train. I have remarked elsewhere that poetry is not a form of entertainment, and in a certain sense not even a form of art, but our anthropological, genetic goal, our linguistic, evolutionary beacon. We seem to sense this as children, when we absorb and remember

The evaluation of reality made through such a prism—the acquisition of which is one goal of the species—is therefore the most accurate, perhaps even the most just. (Cries of “Unfair!” and “Elitistl” that may follow the aforesaid from, of all places, the local campuses must be left unheeded, for culture is “elitist” by definition, and the application of democratic principles in the sphere of knowledge leads to

equating wisdom with idiocy.)

taking inspiration from a poem by W. Auden, B. engraves his thoughts on language:

Time that is intolerant

Of the brave and innocent,

And indifferent in a week

To a beautiful physique,

Worships language and forgives

Everyone by whom it lives;

Pardons cowardice, conceit,

Lays its honours at their feet.

But for once the dictionary didn’t overrule me. Auden had indeed said that time (not the time) worships language, and the train of thought that statement set in motion in me is still trundling to this day. For “worship” is an attitude of the lesser toward the greater. If time worships language, it means that language is greater, or older, than time, which is, in its turn, older and greater than space. That was how I was taught, and I indeed felt that way. So if time—which is synonymous with, nay, even absorbs deity—worships language, where then does language come from? For the gift is always smaller than the giver. And then isn’t language a repository of time? And isn’t this why time worships it?

Uncertainty, you see, is the mother of beauty, one of whose definitions is that it’s something which isn’t yours. At least, this is one of the most frequent sensations accompanying beauty. Therefore, when uncertainty is evoked, then you sense beauty’s proximity. Uncertainty is simply a more alert state than certitude, and thus it creates a better lyrical climate. Because beauty is something obtained always from without, not from within. And this is precisely what’s going on in this stanza.

But you don’t dissect a bird to find the origins of its song: what should be dissected is your ear. In either case, however, you’ll be dodging the alternative of “We must love one another or die,” and I don’t think you can afford to.

1 note

·

View note