#hanaire

Photo

信楽 ハナ挿シ Shigaraki clay Flower base 97×107 200H ,@2021 Anagama kiln #vidro #shigarakiclay #noglaze #anagamakiln #wildclay #naturalashglaze #flowerbase #yakishime #satokionishi #woodfired #turukubi #woodfiring #hanaire #焼締め #信楽 #ハナ挿シ #茶壺 #花器 #煎茶 #大西左朗 #花入れ #自然釉 #窯変 #ハナ挿シ #鶴首 https://www.instagram.com/p/CmjIoZwLaW6/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

#vidro#shigarakiclay#noglaze#anagamakiln#wildclay#naturalashglaze#flowerbase#yakishime#satokionishi#woodfired#turukubi#woodfiring#hanaire#焼締め#信楽#ハナ挿シ#茶壺#花器#煎茶#大西左朗#花入れ#自然釉#窯変#鶴首

0 notes

Photo

Double-cut (Nijū-giri) Flower Container (Hanaire), named Cool Summer Morning (Shinryō), by Kōgetsu Sōgan, early 17th century

282 notes

·

View notes

Text

Nampō Roku, Book 7 (76): the Flowers and the Hanaire.

76) In the case of a meibutsu-hanaire -- or a hanaire that, while not [technically] meibutsu, is still treasured [by the host] -- the flowers should surely be handled in such a way that they seem a little sparse¹.

○ [You] should understand that the flowers should always be appropriate for the hanaire [in which they are arranged]².

_________________________

◎ Though this entry consists of only two sentences, there is no obvious connection between the two -- other than that they are both concerned with the flowers and the hanaire.

Even though this entry is so short, there are still several different versions of it found across the various Nampō Roku sources. In addition to Shibayama’s toku-shu shahon version (which, as usual, adds some additional material that helps to expand upon or illuminate the meaning), Tanaka’s genpon text reworks the toku-shu shahon material into a partially-new narrative that the chajin of the Edo period would have found more useful in the practice of their own chanoyu.

Because the genpon version is so different from the others, it will be covered separately, in an appendix that will be found at the end of this post. Shibayama’s version will, as usual, be discussed in the footnotes under the main translation.

¹Meibutsu no hanaire, sa-nakute mo shōgan no hanaire ni ha, hana ha ika ni mo sukoshi sabite ashiraite yoshi [名物ノ花入、サナクテモ賞翫ノ花入ニハ、花ハイカニモ少サヒテアシライテヨシ].

Meibutsu no hanaire [名物の花入]: a meibutsu-hanaire is generally one that was treasured, or declared to be such (if it had not been discovered by himself), by one of the great chajin of the past -- people like Yoshimasa and the early generations of expatriate chajin who began to arrive in Japan during the fifteenth century. No matter how much you might love and treasure one of your own pieces, you do not have the capacity to make it meibutsu.

Sa-nakute mo shōgan no hanaire [差なくても賞翫の花入]]: sa-nakute mo [差なくても] means as for the rest (of the hanaire) that are not (meibutsu); shōgan no hanaire [賞翫の花入] means a hanaire that is treasured (by the host).

Hana ha ika ni mo sukoshi sabite ashiraite yoshi [花は如何にも少し寂びて遇いてよし]: ika ni mo [如何にも] means to be sure, certainly, really; sukoshi sabite ashiraite [少し寂びて遇いて] means (the flowers) should be handled in such a way that they seem a little lonely*.

In other words, when using a treasured hanaire -- whether it is a meibutsu piece or simply one that is cherished by the host for whatever reason -- it is best to use fewer flowers than would ordinarily be the case. The point is that a complicated arrangement will not only conceal, but also detract from the hanaire. By using just a few flowers, the hanaire will neither be overpowered by their beauty, nor obscured by them physically.

Shibayama Fugen’s toku-shu shahon records this text as meibutsu no hanaire, sa-naku tomo shōgan no hanaire ni ha, saku-sha wo shō-shite, hana ha ika ni mo sukunaku sabite ashiraite yoshi [名物ノ花入、サナク共賞翫ノ花入ニハ、作者ヲ賞シテ、花ハイカニモ少クサヒテアシラヒテヨシ].

While essentially the same, this version adds the phrase saku-sha wo shō-shite, which means (a hanaire) that is treasured by the person who made it -- as another category of hanaire that should be handled in the way described here.

This phrase seems to be referring to take-zutsu [竹筒] (hanaire made from lengths of bamboo), such as the ichi-jū-giri [一重切], since these were the most common hanaire to be handmade by chajin for their own use.

__________

*Sabite [寂びて], which literally means lonely or forlorn, here means that the flowers should appear to be less than sufficient (according to the tastes of the time). This is why I chose to translate sabite as sparse.

The term sabi [寂び], and its various grammatical forms, became associated with chanoyu through Sōtan, who used it to describe a (positive) aesthetic of calculated rustic minimalism. This indicates that this entry was written around the middle of the seventeenth century, or after.

²Hanaire ni sō-ō-suru hana kokoro-e-beshi [花入ニ相應スル花心得ヘシ].

Hanaire ni sō-ō-suru hana [花入に相応する花心得べし] means flowers that are suitable for the hanaire.

This is referring to an Edo period teaching that divided both hanaire and flowers into the traditional categories of shin [眞], gyō [行], and sō [草]. As nothing like this was ever seen prior to the Edo period -- particularly in so far as the flowers were concerned -- this is another detail that informs us that we are dealing with an Edo period addition to the collection.

Rikyū, for his part, combined his flowers with his hanaire in ways that would likely frustrate many modern-day chajin -- since his rationale was always what looked best, rather than what conformed to the rules (most of which had not even been articulated in his day).

If a detailed list of which hanaire -- and which flowers -- are to be considered shin, or gyō, or sō, it is recommended that the reader apply to one of the authorities in the school with which they are affiliated, since these things differ, often radically, from school to school...so any list that would satisfy the members of one would likely displease, if not infuriate, the members of another.

About this entry, Shibayama Fugen wrote:

Hanami ni sugi, moshiku ha hō-fu ni hairureba, ka-ki wo oshite sono sakae nakarashi muru ni itaru yue ni, ka-ki wo sakae sen to hosseba, hana ha karuku ikezaru-bekarazu, tada ni keiki nomi narazu, sono utsuwa ni ōzuru shiki-sai kei-jō wo mo sen-taku subeki wo ieru nari.

Kore hitori ka-ki nomi narazu, sho-gu mina shikaru nari, ka no hon-roku 1 (13) ni iu tokoro no "tō no chaire ni imayaki chawan iu-iu" mo mina sono omoki mono wo sakae arashimen to ni soto narazu.

[花美ニ過ギ、若シクハ豊富ニ入ルレバ、花器ヲ壓シテ其栄ナカラシムルニ至ル故ニ、花器ヲ栄セント欲セバ、花ハ軽ク生ケザル可ラズ、啻ニ軽キノミナラズ、其器ニ應ズル色彩形状ヲモ撰擇スベキヲ云ヘルナリ。

[是特リ花器ノミナラズ、諸具皆然ルナリ、彼ノ本録一(一三)ニ云フ所ノ「唐ノ茶入ニ今焼茶碗云々」モ皆其ノ重キ者ヲ栄アラシメントニ外ナラズ。]

This means “if the flowers are too beautiful or plentiful, they will overwhelm the vase and diminish its glory. So if you want the vase to be seen at its best, you must arrange the flowers lightly. It can also be argued that the color and shape [of the flowers] should be chosen according to the vase.

“This is true not only with respect to vases, but also of all the utensils. As it says in Book One (entry 13), ‘kara-no-chaire, modern tea bowls....’: it is certainly true that everything [else] should be carefully selected in order to enhance [the presentation of] the important utensil.”

The cited passage from Book One reads:

With respect to the utensils for the small room, it is better if everything is [somewhat] lacking. There are people who detest things that are even slightly damaged, [but] this [kind of attitude] is completely unacceptable.

In the case of newly-fired [pieces of pottery] and objects of that sort³, if they have developed cracks, they are difficult to use. But things like imported chaire and other ‘proper’ utensils, when they have been repaired with lacquer, can still be used in the future.

Besides this, when [we] speak of the way to combine the utensils: a recently fired chawan [used together with] an imported chaire -- [you] must know how to do [things] like this.

In Shukō's period, even though the things [used for chanoyu] were still splendid at that time, he put his treasured ido-chawan into a fukuro, handling it just like a temmoku; and [he] initiated the practice of always bringing out a natsume, or a recently-made chaire, together with it.

The annotated version of the text, together with its footnotes and commentary, may be found in the post entitled Nampō Roku, Book 1 (17): the Utensils for the Small Room. The URL for that post is:

http://chanoyu-to-wa.tumblr.com/post/175662294463/namp%C5%8D-roku-book-1-17-the-utensils-for-the

Note that, because Shibayama’s teihon [底本] was divided into sections differently, the number of the entry in his source does not agree with the number found in this translation. Certain details of the entry in question, as it is found in the Enkaku-ji manuscript, also suggest that it was, at least in part, modified during the Edo period -- since certain details that it describes are anachronistic (reflecting Edo period attitudes rather than those of Shukō’s period).

==============================================

❖ Appendix: the Genpon Version of Entry 76.

In the case of a meibutsu-hanaire -- or, while not [a meibutsu], one that is still a treasured hanaire -- if it was one that had been treasured by its maker, on occasions such as when it is being used for the first time, the rule is that fewer flowers should be put in [than usual]³.

_________________________

³Meibutsu no hanaire, sa-nakute mo shōgan no hanaire aru-koto ha, saku-sha wo shō-shite, hanaire-biraki nado, hana sukunaku-iru hō nari [名物ノ花入、サナクテモ賞翫ノ花入アル事ハ、作者ヲ賞テ、花入ビラキナド、花少ク入ル法也].

Saku-sha wo shō-shite [作者を賞して] means (a hanaire) that was treasured by the chajin who made it.

This suggests that the author is referring specifically to bamboo hanaire, such as the ichi-jū-giri [一重切] or take-zutsu [竹筒] (shakuhachi-giri [尺八切]) sorts. Nothing of the sort was ever implied by the Enkaku-ji version of the text, however.

Hanaire-biraki nado [花入披き]: hanaire-biraki [花入披き]* means either the first time that the hanaire is used, or the first time it is being used by its current owner (who is presumed to be the host)†. Hanaire-biraki nado [花入披きなど] means on occasions such as the first time the hanaire is being used, and the like -- that is, on occasions when, for whatever reason, the host wishes to draw attention to the hanaire‡.

Hana sukunaku-iru hō nari [花少く入る法なり]: now the idea that the flowers should appear to be “a little lonely” (sabite [寂びて]) has been clarified into the more literal “fewer” or “insufficient” (sununaku [少く]), and elevated to the status of a law (hō nari [法なり]) -- both of which would have been better appreciated by the chajin of the Edo period than what we find in the original Enkaku-ji text.

__________

*Today it is usually written hanaire-biraki [花入開き]. Both forms mean the same thing -- the “opening,” which is to say the first use, of the flower vase.

†The text is ambiguous. The meaning could be that the hanaire turned out to be so perfect (in the estimation of the chajin who made it), that he is following this rule the first time he uses it. Or that, because the maker so deeply admired his own creation, the subsequent owner should use it this way on the first occasion when it is shown in his tearoom.

While something that would have been of concern to the chajin of the Edo period, this is really all irrelevant to the original text, since, in Jōō’s and Rikyū’s period the only pieces to which this entry could have applied were imported hanaire (all of which were either bronze or ceramic), or the rare locally potted pieces. Bamboo hanaire, even those made by renowned chajin such as Rikyū, were treated as disposable -- since they were (usually) discarded once the bamboo began to be discolored by mold or water stains.

‡The formula for such gatherings would be that the host displays the hanaire (without water or flowers) in the toko -- usually on the floor, sometimes resting on a tray, sometimes tied into its shifuku, and sometimes even accompanied by its box (or the lid of the box, in order to display its hako-gaki [箱書]), depending on the host (and the teachings of the school with which he is affiliated) -- during the shoza; then it is arranged properly (either suspended from a hook affixed to the back wall, or placed in the middle of the floor of the toko on an usu-ita), with water and flowers in it, during the goza.

On this genpon version of the text, Tanaka Senshō wrote:

Migi no gotoku de aru to, hanaire no saku-sha ni tai-shite, isasaka kei-i wo arawashite, hanaire wo hajimete shiyō-suru hanaire-biraki no toki nado mo, mina-bana wo sukoshi-ireru ga hō de aru to no i de aru.

Yo ha aru-toki, meibutsu no kago-hanaike wo toko ni kazari, hana-shomō wo uketa-koto ga atta. Tadachi ni kono mon-ku ga atama ni pin to hibiita yue, itatte kei-shō ni irete, teishu ni o-naoshi wo tote, fusoku no bun no soe-bana wo kōta ga, teishu ha tada mizu wo sosoi de ka-dai wo hiita-koto ga aru. Ka no gotoki toki ni, jibun no hana no ude wo mise-yō nado omotte ha naranu.

[右の如くであると、花入の作者に対して、聊か敬意を表して、花入を始めて使用する花入披きの時なども、皆花を少し入れるが法であるとの意である。

[予はある時、名物の籠花生を床にかざり、花所望を受けたことがあった。直ちにこの文句が頭にピンと響いたゆえ、至って軽少に入れて、亭主にお直しをとて、不足の分の添え花を乞うたが、亭主は只水を注いで花台を引いたことがある。かの如き時に、自分の花の腕を見せようなど思ってはならぬ。]

“As [we read] on the right, to show respect to the creator of the hanaire, when using the vase for the first time on an occasion when [the host] indicates it is the hanaire-biraki [花入披き], or something like that, it is the rule that the flowers should be added sparely.

“On a certain occasion when [I was] participating [in a gathering], [the host] displayed a meibutsu basket hanaike [花生] in the toko, with the request that [I] arrange the flowers [during the naka-dachi, before the others had returned to the room]. Because the text of this entry suddenly began to reverberate through my mind, I arranged the flowers very lightly and sparely.

“Asking the host to repair it [to his satisfaction], [I] begged him to add more flowers to make up for the deficiency; but the host simply added water, and then lifted [the arrangement] up onto the flower stand.

“On occasions such as this, one should not even think about showing off one’s flower-arranging skills.”

It might be good to mention that, far from the regimented minimalism seen in modern-day chabana, over the course of the Edo period these arrangements, too, had became increasingly stylized according to the tenets of the various schools of ikebana (specifically, their so-called nage-ire [投げ入れ] type of arrangement, which was a mechanical description of the way that chabana were always supposed to be created). Indeed, at least several of the schools that have survived into the present actually derived from the teachings of the prominent chajin of the early-to-middle Edo period. It was only in the 20th century that the tea schools began to actively distance themselves both from the practice of flower arrangement, and from the rule-based arrangements that were taught by those schools -- previously, the same town teacher who provided lessons in chanoyu to the local community also taught them ikebana. It is in light of all of this history (in which he most certainly was a participant) that Tanaka’s remarks should be understood.

==============================================

◎ If these translations are valuable to you, please consider donating to support this work. Donations from the readers are the only source of income for the translator. Please use the following link:

https://PayPal.Me/chanoyutowa

0 notes

Photo

Double-cut (Nijū-giri) Flower Container (Hanaire), named Cool Summer Morning (Shinryō)

early 17th century, Japan

Kōgetsu Sōgan

"(hanaire) was created for the tea ceremony by Kōgetsu Sōgan, who mentions making it in his accompanying letter, now mounted as a hanging scroll. The son of Tsuda Sōgyū (died 1591), one of the San Sōshō (Three Greatest Tea Masters), Sōgan became a Zen monk of the Rinzai sect as well as the 156th head abbot of the Daitokuji Temple in Kyoto. In 1612 he built the famous Kohōan, a subtemple of Daitokuji, with the noted feudal lord, architect, garden designer, and tea master Kobori Enshū (1579–1647)." MET

189 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Vase (hanaire), Masamune Satoru, early 21st century, Minneapolis Institute of Art: Japanese and Korean Art

thick body; roughly cylindrical shape; slightly asymmetrical; flat base with rounded outward-flaring area just above base; two thick handles below bulging ring below vertical, slightly wavy mouth; brown patina with grey spots and mottled golden areas

Size: 10 9/16 × 6 5/8 × 5 1/2 in. (26.83 × 16.83 × 13.97 cm)

Medium: Stoneware

https://collections.artsmia.org/art/116960/

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Today’s Chabana - 13.07.2020:

Veronica longifolia “Blue John”

Catharanthus roseus

Hanaire made by Stephani Borchardt, Garmisch-Partenkirchen

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Perché studiare #cerimoniadeltè #giapponese? Anche perché ci avvicina alla #natura e ce ne fa #godere appieno. Come con queste belle #ortensie del #chabana in #hanaire di #bamboo . #giappone #chanoyu #cerimoniadelte #scuoladicerimoniadelte #Jaku #omotesenke #corsi #lezioni #chado #matcha (presso Lucca, Italy)

#natura#ortensie#chabana#hanaire#omotesenke#bamboo#corsi#jaku#lezioni#scuoladicerimoniadelte#chado#giapponese#matcha#chanoyu#godere#giappone#cerimoniadelte#cerimoniadeltè

0 notes

Video

〈EDBFL+〉 #9 Seri Takeda [Ceramics] 20180405-17 ー Slow monday start with ICED LATTE☕️ 今週も頑張っていきましょうー ー [写真の作品] ・ハナイレ(右/ w7cm d7cm h6.5cm/ ¥5,000- w/tax) ーーー #edbfl+ #9 #seritakeda #ceramics #sericeramics #hanaire #slowmonday #icedlatte #specialtycoffee #coffee #flowertea #singleo #kinto #mamigashi #hototogisu #flowercoffeebb #everydaybeautiful #shonan #chigasaki #yuzostreet (FLOWER COFFEE / BREW BAR)

#hanaire#edbfl#everydaybeautiful#flowertea#9#ceramics#sericeramics#icedlatte#flowercoffeebb#hototogisu#chigasaki#seritakeda#singleo#kinto#shonan#yuzostreet#coffee#mamigashi#specialtycoffee#slowmonday

0 notes

Text

Hanair Mechanical Ltd - Specialists in Air Conditioning Services and Installation

Hanair Mechanical Ltd are an Air Conditioning company founded in 2015. They provide new and existing customers with installation and ongoing maintenance of their air conditioning units, both in commercial premises and domestic properties. In Addition to offering installation services, Hanair Mechanical Ltd can also tailor an ongoing maintenance package for their customers air conditioning system, to see that it performs efficiently and has a longer life span. Their experienced and professional team of engineers always on hand to assist in any emergency that may arise, with urgent call-outs for fast repairs in the event of a break down. For more information please call 01342 617 056/07546 930 940 or visit: http://www.hanair.co.uk/

Connect with us at:

youtube.com

blogspot.co.uk

tumblr.com

wordpress.com

weebly.com

about.me

medium.com

gravatar.com

Visit us at:

Hanair Mechanical Ltd

The Beehive

Beehive Ring Road

Crawley

Gatwick

RH6 0PA

01342 617 056

07546 930 940

51.144296,-0.163332

1 note

·

View note

Photo

How many blue frogs are there? #frog #shigarakiclay #greenfrog #anagama #shigaraki #shigarakijar #flowervase #yakishime #satokionishi #hanaire #vidoro #woodfiring #hanasashi #花入れ #花瓶 #信楽 #ハナ挿シ #茶器 #大西左朗 #穴窯焼成 #青ガエル #信楽花入 #うずくまる #青蛙 #ミニカエル #蛙 (信楽町) https://www.instagram.com/p/CQ5CX35jsdz/?utm_medium=tumblr

#frog#shigarakiclay#greenfrog#anagama#shigaraki#shigarakijar#flowervase#yakishime#satokionishi#hanaire#vidoro#woodfiring#hanasashi#花入れ#花瓶#信楽#ハナ挿シ#茶器#大西左朗#穴窯焼成#青ガエル#信楽花入#うずくまる#青蛙#ミニカエル#蛙

0 notes

Text

Nampō Roku, Book 7 (72c): Nambō Sōkei’s Collection of Wabi Tea Utensils (Part 3: Other Miscellaneous Utensils).

〽 A [tsuri-]bune [舟]. [Received] from [Sumiyoshi-ya] Sōmu¹.

〽 The Ōuchi no asa-nabe [大内ノアサナヘ]. Presented [to me] by Lord [Ri]kyū².

〽 A te-kago [手籠]³.

〽 A take-zutsu [竹筒]. [Made by Seta] kamon⁴.

〽 A metal koboshi [コホシ]⁵.

The things [listed] before [-- in parts one and two, as well as here --] were all praised by Lord [Ri]kyū⁶.〚But as for the rest [of my tea things], none are suitable utensils.⁷〛

〽 A large rōtei [hanaire]⁸.

〽 The Nara-ya [cha-]tsubo⁹.

〽 The nata-me mizusashi [ナタ目水サシ]¹⁰.

These three pieces were acquired after [Ri]kyū’s death¹¹. If [he] were still alive and able to look at them, I am sure they would have been a delight to his heart¹². How sad [that Rikyū is no longer with us]¹³!

_________________________

◎ This list continues on from parts one and two of entry 72; and all of the objects listed (with the exception of the final three entries here) are part of the same list of objects that, the author of this text alleges, were inspected and certified by Rikyū.

The identities of several of the objects discussed in this last section of the entry cannot be verified with anything approaching certainty. In those cases, the photos displayed below represent a best guess -- based on what little available evidence exists.

We must keep in mind that, far from being a historical source (documenting Nambō Sōkei’s tea-utensil collection -- even though this is what the text purports to be), this list was compiled (apparently by someone affiliated with the Sen family) and insinuated into the Shū-un-an cache of documents, for some specific (though unstated) purpose*. Very few of these things are actually mentioned by Rikyū, or described in kaiki that document his tea activities.

In just one instance, I added a sentence that is found in Shibayama Fugen’s toku-shu shahon text, but missing from the Enkaku-ji manuscript, because it helps to contextualize the first list (which only describes part of Sōkei’s tea-utensil collection). As always, this sentence has been enclosed in doubled brackets.

___________

*Possibly, since at least a number of these utensils are known to have been in the possession of the Sen family at the time when this list was apparently compiled, this was done in an effort to create an artificial denrai [傳來] -- a historical record of transmission -- for objects that otherwise lacked this kind of documentation. Such a denrai could be used either to give validity to the Sen family as the authentic successors and inheritors of Rikyū’s chanoyu, or to enhance the value of these utensils in the event that the Sen family ever wished to sell them -- or simply as a way to impress their guests.

¹Fune Sōmu yori [舟 宗無ヨリ].

The name Sōmu [宗無] is referring to Sumiyoshi-ya Sōmu [住吉屋宗無; ? ~ 1595*], who was a respected chajin from Sakai. He (along with Rikyū and Tennōji-ya Sōkyū) was instrumental in establishing the tea village in the pine barrens at the Hakozaki-gū [筥崎宮]†, where Hideyoshi could interact with the wealthy merchant-chajin of Hakata, during Hideyoshi’s Kyūshū campaign. Sōmu had been a disciple of Jōō, and it was from Jōō that he had learned the secret traditions related to the tsuri-bune -- thus he certainly would have owned a respectable bronze tsuri-bune (though none has been nominally associated with him in the kaiki that survive from the period).

Though none of the several bronze tsuri-bune that have survived from the sixteenth century has been identified with Sōmu, one of them -- the one that came into the possession of the Tokugawa family when they took ownership of Hideyoshi’s collection of tea utensils (shown below) -- is, oddly, not associated with any previous owner. Sōmu died on the same day in 1595 as Toyotomi Hidetsugu, Hideyoshi’s adopted son and heir‡. Though nothing is said that directly connects Sōmu with Hidetsugu, the fact that they died on the same day is certainly suspicious.

When someone presented a precious tea utensil to Hideyoshi, the fact was usually mentioned somewhere. But when a person was ordered to commit seppuku, his property was usually confiscated by the government, and in this case no special mention was made regarding how those objects came to be in Hideyoshi’s possession. If Sōmu was condemned on account of an association with Hidetsugu (who, we must remember, was both a talented practitioner of chanoyu, and who surrounded himself with others who shared this interest), this could explain how the high-quality bronze tsuri-bune shown above came to be in Hideyoshi’s collection (without any record of how it came to be there). For this reason, it is at least plausible that this hanaire may be the “fune” (boat) that had once belonged to Sōmu.

Sōmu yori [宗無より] clearly implies that this tsuri-bune was presented to Nambō Sōkei by (or else otherwise acquired from‡) Sumiyoshi-ya Sōmu, though there does not seem to be any evidence to support this assertion -- including the historical situation described above (Sōmu died a little over a year after Nambō Sōkei).

Tanaka Senshō is the only commentator to venture into expressing an opinion about this hanaire, and his conclusion was that this tsuri-bune must have been made from bamboo** (possibly by Sōmu himself). There is a major problem with this thesis, however: the tsuri-bune made out of bamboo is said (by many of his contemporaries, as well as subsequent generations) to have been created by Sen no Sōtan. So while this entry was clearly written during the late seventeenth century (according to its language), and also appears to be associated with the Sen family, this list was supposed to be a catalog of wabi utensils that had been owned by Nambō Sōkei prior to the Third Month of 1594, thus it would be stripping Sōtan of one of his achievements to imply that a bamboo tsuri-bune had been in existence at a time when Sōtan was a mere child. Though oki-zutsu [置き筒] -- bamboo tubes that were stood upright on the floor of the toko -- had been around since at least the time of Jōō, the ichi-jū-giri [一重切] and ni-jū-giri [二重切] made their first appearance in the summer of 1590, during Hideyoshi's siege of Odawara; and following his house arrest in the autumn of the year, and subsequent seppuku the following spring, experimentation with this medium seems to have been suppressed until the beginning of the third decade of the sixteenth century) -- during which multi-decade stretch chanoyu appears to have entered into a prolonged hibernation.

__________

*However, other sources give his dates as 1534 ~ 1603 (though most scholars seem to conclude that these dates are better connected with Sōmu’s son).

†As one of the chajin mentioned in Book Seven, it is not surprising that his name was appropriated for inclusion in this list.

Sumiyoshi-ya Sōmu is not included in the list of Hideyoshi’s eight tea officials (Hideyoshi no sadō hachi-nin-shū [秀吉の茶頭八人衆]), which, given his obvious importance during the tea events connected with the Kyūshū campaign, is difficult to explain (he was one of the very small number of chajin whose name and utensils are recorded in the Yamanoue Sōji ki [山上宗二記]). It is possible that he was demoted and his name was suppressed posthumously, on account of some association with Hidetsugu (as mentioned above, Sōmu curiously is said to have died on the same day as Hidetsugu and his other supporters).

‡His first son Tsurumatsu [鶴松] (also known by his infant name of Sute [棄]), was born during the summer of 1589. He was, however, a sickly child, who finally died in the early autumn of 1591.

Following this child’s death, Hideyoshi officially adopted Hidetsugu (who was the first son of Hideyoshi’s elder sister) as his heir. Hidetsugu had previously served in important positions in Hideyoshi’s government (after the death of Nobunaga), since he was one of Hideyoshi’s few biological relatives.

Hidetsugu’s decline began when Hideyoshi’s second son was born in 1593; and his position only worsened once it became clear that Toyotomi Hideyori [豊臣秀頼; 1593 ~ 1615] was a strong child, who showed every prospect of living to succeed his father. Thus Hidetsugu had to be eliminated, albeit carefully (since he was supported by many influential daimyō), in order to prevent a potential succession crisis.

‡Though a respected monk (he was formerly the shuso [首座] of the Nanshū-ji, meaning he was one of the three highest-ranked monks in the temple hierarchy), Nambō Sōkei does not seem to have had any money. Consequently, it is unlikely that he could (or would) have purchased this tsuri-bune from Sōmu.

**Which, he reasons, is why none of the surviving bronze boats are associated with Sumiyoshi-ya Sōmu.

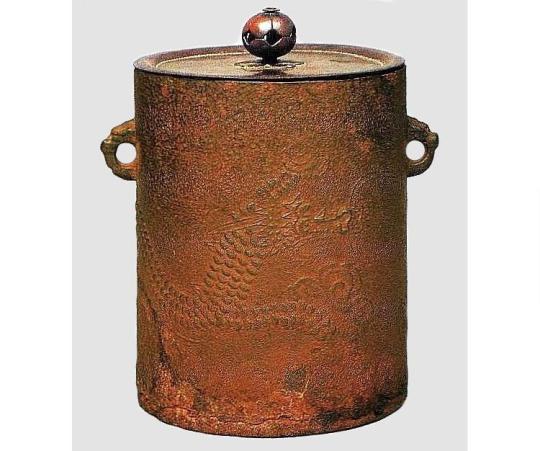

²Ōuchi no asa-nabe Kyū-kō yori tamawaru [大内ノアサナヘ 休公ヨリ給ル].

An asa-nabe [淺鍋] is a shallow metal (usually Korean bronze) vessel in which hot food (usually stir-fried meat or seafood) was served on the tables of people of the upper classes, in the Korean manner (the chafing-dish was heated over a fire, the hot food was put on it, and then it was moved to a wooden base, covered, and carried quickly to the room where the meal was being served -- so the person helped themself from the asa-nabe). Since this style of food service was rarely seen in Japan, these asa-nabe were converted into tsuri-kōro [釣り香爐]* (and later used as hanaire [釣り花入]†) by attaching (usually four) chains to then, as seen in the photo below. Asa-nabe are generally considered a subcategory of the tsuri-bune (and their use was governed by the same exhaustive list of rules, most of which were codified by Jōō).

The Ōuchi asa-nabe is the hanaire shown above.

Kyū-kō yori tamawaru [休公より給わる] means it was presented (to Nambō Sōkei) by Lord Rikyū*.

For the second phrase, Shibayama's toku-shu shahon has Kyū-kō yori tamau [休公ヨリ給フ], which has the same meaning.

__________

*The tsuri-kōro was usually suspended above the dashi-fuzukue [出し文机], the built-in writing desk in the shoin, to perfume the air blowing in through the window.

In fact, most of the tsuri-bune that dated from the early sixteenth century and before were originally used as tsuri-kōro, with these being appropriated for use as hanging flower containers only during Jōō’s lifetime (beginning in his middle period) While deeper “boats” were often provided with false bottoms perforated with holes, into which the flower stems were inserted, the asa-nabe may have been responsible for the creation of the kenzan hana-tome [劍山花留め] -- the pin-holder with a lead base that allows flower stems to be impaled at various angles. Though today the province of ikebana, during Rikyū’s lifetime such distinctions did not exist (the “wabi” version of stabilizing the flowers by using a Y- or X-shaped arrangement of twigs was championed by Sōtan and his sons, as a deliberate way to distance their practice from the things done in the flower-arranging schools).

†Kyū-kō [休公], Lord Rikyū, was the way that the Sen family began to refer to Rikyū during the seventeenth century (after he was mythologized by the Tokugawa bakufu).

³Te-kago [手籠].

This appears to refer to the basket usually referred to as the Arima kago [有間籠] today. This basket was originally made to be placed on the ground, with a candle burning inside*, along the paths leading from the private rooms to the baths at the famous Arima onsen [有間温泉].

Rikyū stayed at the Arima onsen for the first time, in the company of Hideyoshi, in 1590 (which is why the Sen family knew of this basket).

The above is supposed to be the original basket used by Rikyū when he served tea to Hideyoshi (during the daytime) on the occasion of their visit to the onsen.

__________

*The thin bamboo plaiting, that replaced the more common paper walls, allowed enough light to pass through that the guests could be sure of their footing, while leaving the garden as unaffected by light pollution as possible.

⁴Take-zutsu Kamon [竹筒 カモン].

Take-zutsu [竹筒] means a bamboo tube. While this was one common name for any hanaire made from a length of bamboo (regardless of how it was carved), here it probably refers to an oki-zutsu [置き筒], a length of bamboo cut so that it would stand up on the floor of the toko. Oki-zutsu had existed at least since the time of Jōō (and their history probably extended back even further, to the time of the earliest wabi practitioners who arrived in Japan in the middle of the fifteenth century)*.

The maker of the above take-zutsu is not known. It is sometimes ascribed to Rikyū†, and sometimes to another person from his period -- but these attributions date no earlier than the Edo period, and better reflect the desires of the owner than anything that might be considered historically accurate information. (This take-zutsu seems to have been made as an oki-zutsu, with a metal ring -- of the sort that are commonly used to hang up ceramic hanaire -- nailed into the back side, which was usually done only by someone other than the original maker; during the Edo period, the container was lined with copper, to help prevent cracking.)

Kamon [掃部] refers to the title owned by Seta Masatada [瀬田正忠; ? ~ 1596]‡, who held the position of kamon-no-suke [掃部頭], the head of the bureau of maintenance and housekeeping in the Kyōto Imperial Palace (which means that he held the junior fifth court rank). His proximity to the Imperial court, and his relative freedom of movement within the palace compound (coupled with the perennial impecuniosity of the denizens of the palace) meant that he was able to amass a collection of the (generally rather large-sized) utensils that had formerly been used on the various o-chanoyu-dana [御茶湯棚] that were found in anterooms adjacent to most of the audience rooms of the palace**.

Seta kamon [瀬田掃部] was famous among his contemporaries for his chashaku, so he certainly had the skills necessary to carve a take-zutsu. Unfortunately, none of them seem to have survived into the present (or even long enough to have entered the records dating from the Edo period††).

__________

*The ichi-jū-giri and ni-jū-giri were created during the siege of Odawara, in the summer of 1590. While it is possible that Seta Masatada was inspired to imitate Rikyū's ichi-jū-giri, there is no documentary evidence to support this. (As for the ni-jū-giri, that kind of take-zutsu was originally not used as a hanaire for chanoyu, since its actual purpose had been to hold the flowers for an all-night flower-arranging competition that Hideyoshi hosted during the siege -- with the arrangements created in either the ichi-jū-giri that was suspended on the back wall of the toko, or in the oki-zutsu -- the shaku-hachi-giri [尺八切] -- that was placed on the floor.)

Rikyū does not seem to have used his ni-jū-giri (named Yonaga [よなが]) at a chakai until the eighth day of the First Month of Tenshō 19 [天正十九年] (February 1, 1591); and on that occasion the guest was Abura-ya Jōsa [油屋常佐; dates of birth and death unknown], a wealthy Sakai merchant whose firm dealt in oils. It is not clear that anyone (particularly Seta kamon) was, at that time, familiar with the precedent that he was setting -- since the ni-jū-giri does not seem to have been used in this way again until the Edo period.

†Concerning attributions of any take-zutsu to Rikyū (other than the four that are known to have been created during the siege of Odawara), there is this argument:

“Aono Heinai (15??~15??): a chajin from Sakai in Izumi. He was a nephew of Sen no Rikyū. He received instruction from Sen no Rikyū on the [take-]zutsu. Many of the tsutsu-hanaire that are considered to have been made by Rikyū were actually made by Aono Heinai.”

This was quoted (in Japanese) from the Sengoku Jin-mei Jiten [戦国人名事典], Shin-jin-butsu Ōrai Sha [新人物往来社], Tōkyō (1987), by the author of the blog Sengoku bushō-roku [戦国武将録]. The URL for that relevant blog post is:

http://takatoshi24.blogspot.kr/2011/11/blog-post_10.html

Aono Heinai appears to have been the son of one of Rikyū’s sisters, though details of him and his life are scarce.

‡Some accounts give his dates as 1548 ~ 1595.

**With the appearance of chanoyu, these o-chanoyu-dana were no longer used, so their utensils were left to deteriorate where last they had been placed when the service of tea from the anteroom was moved to tea prepared at the daisu in the audience room itself.

††Prior to the Edo period, things like this made by the host were not usually mentioned in the records of gatherings. The antecedents of every utensil used during the chakai became “important” only in the Edo period, when chanoyu became hyper-monetized.

⁵Kane-no-koboshi [カネノコホシ].

This refers to the beaten-copper koboshi shown below.

This koboshi was made for Rikyū by one of the craftsmen who was working on Hideyoshi’s building projects*. The shape is based on a (cast) bronze model (that had probably come from Korea), from the sheet-copper that was imported from the continent for use as roofing material.

___________

*Though his name is unknown, this roofer was probably the same person who made the beaten-copper lid for the first small unryū-gama, seen in the photo below.

All of the subsequent small unryū-gama had cast-iron lids that were intended to replicate the shape of the original beaten-copper lid. (Nambō Sōkei came into possession of the second small unryū-gama, which had such a cast-iron lid -- that kama was the one that Rikyū had made for himself after he presented the first unryū-gama and large Temmyō kimen-buro to Hideyoshi. Since Rikyū used his small unryū-gama when making tea on the morning of his seppuku, that kama must have been sent to Sōkei shortly after he was finished.)

The above kama was damaged (as can clearly be seen in the photo) in the earthquake that destroyed Hideyoshi’s Fushimi palace, on the thirteenth day of the Seventh Month of Bunroku 5 [文祿五年閏七月十三日] (September 5, 1596).

Though this horrendous event is commonly known as the Keichō Fushimi dai-jishin [慶長伏見大地震], the “first year” of the Keichō era did not officially begin until the 28th day of the Tenth Month of the same year. Consequently, the last day of the Bunroku era was the twenty-seventh day of the Tenth Month of Bunroku 5 [文祿五年十月廿七日], and the first day of the subsequent Keichō era was the twenty-eighth day of the Tenth Month of the First Year of Keichō [慶長元年十月廿八日] (December 18, 1596).

The change in era names was occasioned by the devastating earthquake; but the change was delayed until the arrival of an auspicious day.

⁶Migi ha Kyū-kō no shōserare-shi-mono nari [右ハ休公ノ稱セラレシモノ也].

Migi ha [右は] is referring to the collection of utensils mentioned up to this point -- the various scrolls; the itome-gama, and the small unryū-gama; the pair of chaire; the Shigaraki mizusashi; the three chawan; the two hanging hanaire; Seta kamon’s take-zutsu, and the Arima-kago; and the beaten-copper koboshi.

Shōserare-shi-mono [稱せられし物]: shōserare-suru [稱せられする], though rarely used in this way today, appears to be equivalent to home-tataeru [褒め稱える], and so meaning (these) objects were celebrated or praised (by Rikyū)*.

__________

*The author does not seem to realize that at least several of these pieces had actually been owned and used by Rikyū. Migi ha Kyū-kō no shōserare-shi-mono nari seems to imply that Rikyū saw these things in the Shū-un-an, and expressed his approval of them to Sōkei.

⁷Hoka ni ha shikaru-beku dōgu mo nashi [外ニハ可然道具モナシ].

This sentence (which helps to qualify our understanding that the utensils listed up to this point did not constitute the entirety of Nambō Sōkei’s collection) is found only in Shibayama Fugen’s toku-shu shahon.

Hoka ni ha [外には] means “as for the rest....” In other words, with respect to the rest of the utensils in Sōkei’s personal collection....

Shikaru-beku dōgu [然るべく道具] is rather difficult to translate comfortably, since it is describing something that was unique to the Edo period (and thereafter)†.

Shikaru-beku dōgu literally means utensils that are “appropriate” or “suitable.” But this is not really a question of functionality or practicality. In the Edo period, as today, “suitable” utensils were either “respectable” pieces -- that is, utensils that had been selected and cherished by some famous tea master of the past (in other words, they were accompanied by a respectable denrai, history of transmission) -- or else‡ expensive contemporary objects that had been made by a famous craftsman, and then (preferably) approved by one of the major iemoto (usually this was certified by his writing his kaō on them with red lacquer and/or signing their box, and possibly giving them a poetic name as well).

Shikaru-beku dogu mo nashi [然るべく道具もなし] means there are no (other) “suitable” (or “appropriate”) utensils (beyond those listed heretofore).

__________

*The speaker is, of course, Nambō Sōkei. He is disparaging all of his other possessions.

†It is important for the reader to understand that modern-day chanoyu has nothing to do with Jōō or Rikyū. It is entirely a product of the Edo period mentality.

In Rikyū's day, particularly in the wabi small room, any utensil could be used. The ido chawan were bowls originally made for the poorest of the common people to use during family Ancestor-worship ceremonies. Chawan made by Furuta Sōshitsu and Chōjirō, as newly fired pieces, were without any commercial value at all, and usually looked down upon (or, at best, considered curiosities) by the professional chajin of the day. Yet these things were all considered, by Rikyū, to be extremely appropriate for use in the small room precisely because they lacked any value.

The closest contemporary equivalent (at least for anyone who had trained in chanoyu in Japan) would be if someone picked up a ¥5000 Shōraku chawan and a plastic natsume, then presumed to use them to serve koicha during a chaji. Any respectable guest would be scandalized and repulsed (and consider that he had been defrauded out of the fee that he had paid to the host for the privilege of having been invited); and the gossip that would buzz its way through the local tea community afterward would certainly deter anyone else from ever visiting that host in the future.

‡This was something that was just coming into being at the time when this entry was written -- as a response to the simple fact that there were not enough famous utensils from the sixteenth century to go around -- to satisfy the demand for “respectable” pieces that were “suitable” to be used when serving tea to one’s guests.

⁸Dai-rōtei [大ロテイ].

Rōtei [驢蹄], as explained in the first post in this series, means the hoof of an ass. The shape of the mouth resembles an upside-down hoof of this pack-animal.

Dai [大], meaning large, was added because rōtei usually described a shape more commonly associated with chaire.

Ceramic pieces with this mouth-shape -- usually flower vases, cruets, or tokkuri -- had been common in Korea since the Shilla [新羅] period (meaning that vessels with this kind of mouth appear among the earliest fired ceramic objects ever produced in the country).

Because flower vases of this sort had been commonly used during Ancestor-worship ceremonies in Korea since ancient times, and many likely made their way to Japan over the centuries, it is impossible to know the specific hanaire of this type that is being referred to in this list. In the late sixteenth century, these were mostly made of Korean celadon, of varying qualities (the best were blue-green, often with vertical carved lines encircling the body; with lower quality pieces featuring an ocher-colored glaze and under-glaze decoration in iron-oxide, such as seen above).

The above piece seems to have been brought to Japan during the 1590s, probably by one of the participants in the first invasion of Korea (in 1592). The ocher-colored glaze, and simplistic decoration, would have appealed to the wabi-chajin of the period.

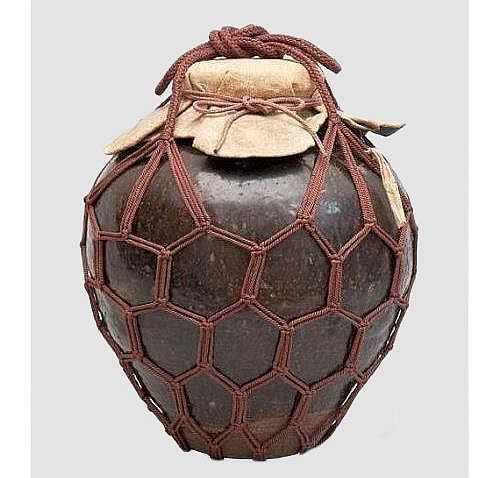

⁹Nara-ya tsubo [奈良屋壺].

The name Nara-ya [奈良屋] is problematic. This is clearly a ya-go [屋號], meaning the name of a commercial firm (and used by the family that owned the firm as a sort of surname). However, the name Nara-ya is associated with a person called Murata Saburōemon [村田三郎右衛門; dates unknown], who was supposed to have been a nephew* of Shukō [珠光]. The difficulty is that, according to all surviving accounts, Saburōemon was a monk, and never had any known connection with business matters at all. Furthermore, the name Saburōemon is the sort of moniker effected by wealthy (or pretentious) townsmen of the Edo period, rather than by citizens of the fifteenth century. Saburōemon is also referred to as Sōju [宗珠] or Dōju [道珠] (either of which would be an appropriate name for a monk); and according to still other versions of his story, he studied chanoyu with Shukō, and became his heir, founding the Jukō-ryū [珠光流], or Shukō school, in Nara.

Since there were no such things as “schools of tea” (as the term is understood in the post-Edo period tea world) in the fifteenth -- or even the sixteenth -- centuries, this entire story is most likely a Sen family fabrication, intended to connect their lineage back to Shukō himself.

The Yamanoue Sōji ki [山上宗二記], wherein one version of the Nara school’s history is recounted, makes no mention of a cha-tsubo [茶壺] associated with that family; neither is the Nara-ya tsubo listed either in the same book’s catalog of the famous cha-tsubo of the day, nor in any of the various kaiki that survive from the fifteenth, sixteenth, or seventeenth centuries. And no cha-tsubo of that name is mentioned in any of the later records. As a result, it is impossible to identify the jar in question, or know whether or not it survives to this day, perhaps under a different name.

The above is an example of a typical cha-tsubo, of the sort that was treasured during Jōō’s and Rikyū’s period. So, if the Nara-ya tsubo ever existed, it was likely similar to the jar shown above†.

__________

*Some accounts suggest that he was a nephew by marriage, and that the Japanese surname Murata [村田] was brought into the family through his marriage to Shukō’s niece (though, again, there is no evidence that Shukō, a tonsured monk, emigrated to Japan together with any members of his secular family: while sometimes accompanied by their sons, the people who quit Korea during the fifteenth century, either following the overthrow of the Goryeo court and the assassination of its last deposed king, or in the wake of the Ming invasion that was determined to seat the Lee family on the throne of a vassal state, seem to have considered female members of the family “wholly dispensable”).

Founding the Nara-ryū (Nara school of chanoyu), Sōju (Dōju) was succeeded by Sōin [宗印] (who is regarded as the third generation iemoto of the Nara-ryū) and Sōshun [宗春] (as the fourth generation grand master), though there are other versions of the lineage.

According to some accounts, the disciples of Sōju (Dōju) included:

- Jōō [紹鷗; 1502 ~ 1555];

- Murata Sōin [村田宗印; dates unknown];

- Wakasa-ya Sōka [若狭屋宗可; dates unknown]: he is alleged to have been the teacher of Shōkadō Shōjō, 松花堂昭乗; 1582~1639];

- Wakasa-ya Sōkei [若狭屋宗啓; dates unknown];

- Takase-ya Sōkō [高瀬屋宗幸; dates unknown]; and,

- Ko-ya Sōyū [木屋宗祐; dates unknown].

The fact that nothing is known about any of these individuals other than Jōō (and even in his case, his teachers are generally said to have been Fujita Sōri [藤田宋理; dates unknown], Jūshi-ya Sōchin [十四屋宗陳; dates unknown], and Jūshi-ya Sōgo [十四屋宗悟; ? ~ 1552]), makes this entire story suspicious -- suggesting that it was a seventeenth century concoction of the machi-shū tea culture, as a way to give historical validity to their lineage, and link themselves directly with Shukō himself.

†Since a jar with more remarkable coloring or glaze would have been singled out for a special name, or otherwise memorialized in the tea documents from the period -- when the cha-tsubo was an important utensil that was always displayed during the shoza of the gathering (at least if it was worthy of such treatment).

¹⁰Nata-me mizusashi [ナタ目水サシ].

A nata [鉈] is a sort of Japanese native machetti, used by wood-cutters* when harvesting the brushwood and undergrowth for use as fuel. Hacking at the stems of these bushes and small trees leaves rough chopping lines, such as seen on the sides of this mizusashi.

The nata-me mizusashi was made by Furuta Sōshitsu, and fired at the Iga [伊賀] kiln -- which is located on the opposite end of the valley from the Shigaraki [信樂] kiln (and where the same sort of clay and ash-glaze were used). This jar originally had a lid that Oribe made at the same time, but it seems it has been lost over the centuries.

While Oribe was certainly responsible for the creation of this mizusashi, there is no indication that it was ever given to Rikyū; nor is a mizusashi of this description mentioned in any of Rikyū’s kaiki (unlike Oribe’s white Shino mizusashi that features prominently in Rikyū’s kaiki, and which Rikyū’s notes in that kaiki indicate was made in 1586†). Indeed, the potting suggests that this was among Sōshitsu’s somewhat later efforts, perhaps not being finished until several years after Rikyū’s death (Oribe’s stay in Korea, during the preparations for the assault on Ming China, seems to have supercharged his creative impulses, which may have lead him to return to the Iga kiln, and try his hand at working in their medium, after his return from the war -- the free use of the spatula when sculpting the sides of this mizusashi gives the same feeling as some of the bowls he made while in Korea).

__________

*Woodcutters occupied one of the lowest strata of Japanese society, just above the literal outcastes. They tended to live in crude hovels in the mountains, and made their living by cutting the underbrush, which they then carried into the cities for sale as cheap fuel when their harvest made a sufficiently large bundle. They are invariably depicted, in the literature of the Edo period, as being bent-backed, and unable to stand upright even when not bearing any burden. The cutters are usually described as rough men; and the bearers were their equally uncouth women.

†Rikyū refers to this mizusashi as kotoshi-no-Seto [コトシノ瀨戸 = 今年の瀬戸], meaning “this year’s Seto” -- in other words that it had been made earlier that year (1586) -- in Book Two of the Nampō Roku.

In his Hyakkai ki [百會記] (which describes the chakai that Rikyū hosted between the Eighth Month of Tenshō 18 [天正十八年], 1590, and his death in the spring of the following year, and so begins its record 4 years later), he calls it a shin-Seto mizusashi [新瀬戸水指] (new Seto mizusashi) -- either because it was still relatively new, or because it was the white Shino glaze that truly made this piece revolutionary (though the Seto kilns had already existed for several centuries, this particular white glaze was never seen before 1586: the glaze on Jōō’s white temmoku represented a slightly different formulation that was nowhere near as effective in appearing to be truly white).

¹¹Kono san-shu ha, Kyū no shi-go motome-shi nari [コノ三種ハ、休ノ死後求シ也].

Kono san-shu ha [この三種は] means these three varieties or pieces (i.e., the dai-rōtei hanaire, the Nara-ya cha-tsubo, and the nata-me mizusashi)....

Kyū no shi-go [休の死後] means after Rikyū’s death.

Motome-shi [求めし]: motomeru [求める] means to ask for, request, want, desire, wish for, search for, and, by extension, things like to purchase, buy, get. So it seems Sōkei is saying that he acquired the above three utensils in the months and years after Rikyū’s seppuku.

Motome-suru [求め爲る], even more strongly than the verb motomeru itself, implies an active search -- Sōkei deliberately sought to purchase these utensils for his collection*. In other words, these things were not simply presented to Sōkei by someone else.

__________

*Which is something that would have been possible during the Edo period (when there were dedicated tea-utensil shops), rather than in the late sixteenth century.

While there were antique shops in Sōkei’s day, to be sure, at least one of these objects would have been newly made -- by Furuta Sōshitsu. And Oribe, as a daimyō and court official, would hardly have been offering his pots for sale in the monthly temple sale. So the basic scenario being advanced by the author does not really hold together.

¹²Zonjō ni te mi-tamae ha ba, kokoro ni kanō-beki-mono-domo nari [存生ニテ見玉ハヽ、心ニカナフヘキモノドモ也].

Zonjō ni te mitamae ha ba [存生にて見給えはば] means if (Rikyū) were alive and was able to look at* (these three utensils)....

Kokoro ni kanō-beki-mono [心に叶べき物]; the verb kanō [叶う] means to fulfill, to realize. Kokoro ni kano-beki [心に叶べき], then, means that all of (one’s) heart’s expectations should be fulfilled (in these pieces); all of (one’s) heart’s desires should be realized (in these pieces). In other words, Rikyū would have been pleased in his heart by these utensils -- they would have touched his spirit in a way that made him feel complete.

The author is asserting that, if these three utensils were presented to Rikyū for his approval, Rikyū’s expectations (in so far as what makes a “good” tea utensil) would have been fulfilled by these pieces. He would have fully approved of them† -- they would, in other words, have been what the people of the Edo period were beginning to refer to as konomi-mono [好み物], and sent Rikyū searching for his pot of red lacquer‡.

Here, Shibayama Fugen’s toku-shu shahon tweaks the original sentence so as to remove every possibility of ambiguity: Kyū zonjō ni te mi-tamae ha ba, kokoro ni kanō-beki dogu naru ni [休存生ニテ見玉ハヽ、心ニ可叶道具ナルニ]: “if [Ri]kyū were alive and able to look at them, he should have been pleased in [his] heart by what these utensils were.”

__________

*Mi-tamae [見給え] is an archaism that is rarely seen in the modern language (other than in Japanese translations of things like the plays of Shakespeare, where the expression is used to give the speech an antique flavor).

†Once again, this is all underlain by a uniquely Edo period sort of perspective on chanoyu. Though Sōkei was at least several years older than Rikyū, and had studied chanoyu with Jōō for longer (whatever “studied” actually meant in the context of early sixteenth century chanoyu, when schools and established curricula did not yet exist) -- Sōkei was already one of Jōō’s senior disciples when the young Rikyū was first introduced to the teacher by Kitamuki Dōchin (so that Jōō could purchase Rikyū’s collection of tea utensils) -- Sōkei is unsure about the utensils he has now acquired until he has obtained Rikyū's pronouncement that they are, indeed, suitable. The Nampō Roku is nothing if not a detailed handbook of the practice of kane-wari; and if Nambō Sōkei himself did not understand its rules, or how those rules impacted the selection of the utensils (that is, their suitability) and the way they were to be handled, then what was the purpose of his detailed notes?

The way of thinking encapsulated in this sentence is certainly the way things are still done in Japan today (where usually the disciple asks their teacher to come along whenever they are anticipating the purchase of a major utensil); but it does not ring true for the chanoyu of the sixteenth century -- when there were neither “schools,” nor “iemoto,” nor minutely codified temae (replete with rules of which utensils can be used for that temae, and which not), nor anything even remotely resembling the menjō-system under which we all function today.

‡Originally it was not a matter of favoring, liking, or a preference (konomu [好む]) for something -- though this is what it became during the Edo period. Rather, (and this is the salient point) the teacher puts his or her personal preferences, tastes, and ego aside, and assesses the utensil purely in terms of kane-wari. Does it conform to the teachings, and can be used in the manner that kane-wari prescribes? Is the piece of a suitable size, and a suitable make so that it can be used for chanoyu? If the answer to these questions was “yes,” then the teacher pronounced the utensil “good” or “suitable” (yoshi [好し] -- which conforms to the original Chinese meaning of the character hǎo [好]).

It was during the Edo period, once the teachings of kane-wari had been forgotten, that this impersonal assessment of the object’s suitability morphed into it being a matter of the master’s personal aesthetics -- whether he liked or disliked the piece in question (which then opened the door for the abuse of the favoritism-for-money situation that dominates the tea world of today).

¹³Zan-nen [殘念].

Zan-nen [殘念] is an ejaculation of intense regret -- regret that Rikyū is no more, and regret that Sōkei had failed to obtain Rikyū’s approval of his new utensils. It is written as if the regret was dripping from the author’s brush, the way the words would have slipped from his lips when overcome by a sudden and unexpected recollecting of the circumstances of this incident.

Shibayama’s text expands this exclamation into a grammatically complete sentence: zan-nen no koto nari [残念ノ事也]. This means “what a regrettable situation!” -- or, perhaps, “what a shame it was!” This is a more literary form, as might be found in an account that was being written by a scribe who had not a participant in the events that were being narrated.

==============================================

◎ If these translations are valuable to you, please consider donating to support this work. Donations from the readers are the only source of income for the translator. Please use the following link:

https://PayPal.Me/chanoyutowa

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Vase (hanaire), Yasuda Zenkō, before 1969, Minneapolis Institute of Art: Japanese and Korean Art

narrow vessel tapering slightly toward top; steeper taper at base forming narrow foot; cream and tan wood grain pattern on walls

Size: 10 3/8 × 6 × 6 in. (26.35 × 15.24 × 15.24 cm)

Medium: Ceramic

https://collections.artsmia.org/art/116951/

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

SHIRO TSUJIMURA

Hanaire Vase, ca. 1990

27.7 × 13.9 cm

Galerie Friedrich Mueller

“Suggestion depends on a willingness to admit that meanings exist beyond what can be seen or described”

“ Perfection, like some inviolable sphere, repels the imagination, allowing it no room to penetrate”

Some of the quotes that resonated with me after the reading. I found myself documenting many more as their poetic nature and profound statements were something i felt i could draw on later, within the unit or other areas. This japanese ceramic vase by Tsujimura seemed to fit the main ideas of the reading, an alluring beauty made all the more intriguing by its imperfections. It reminds me of a lot of different things which i enjoy. Leaving works in such a raw state makes you wonder where the artist was setting out to go, which is a nice concept. It might not have been the initial idea, but the outcome is beautiful none the less.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

La SFD actualise ses recommandations pour le diabète de type 2, en incluant les iSGLT2

La Société francophone du diabète a présenté mercredi dans un communiqué une actualisation de ses recommandations pour la prise en charge du diabète de type 2, qui notamment incluent les inhibiteurs du SGLT2 bien qu'ils soient actuellement absents en France, et accordent une plus grande place aux analogues du GLP-1.

La SFD devait présenter ces recommandations lors d'une conférence de presse, mais celle-ci a dû être annulée en raison des grèves dans les transports. Elle a néanmoins diffusé son actualisation des recommandations (disponible en versions longue et courte sur son site).

La société savante avait publié une "prise de position" il y a 2 ans (cf dépêche du 27/09/2017 à 17:45), qu'elle s'était engagée à réactualiser tous les 2 ans. De plus, "les données de la littérature accumulées depuis deux ans ont enrichi les connaissances et modifié la façon d’envisager les choix thérapeutiques".

L'objectif est d'"aider les médecins généralistes et les endocrinologues-diabétologues à choisir leurs stratégies thérapeutiques, en prenant en compte la balance bénéfices-risques des traitements, l’état de santé mais aussi les préférences du patient, ainsi que les aspects médico-économiques".

Cette accumulation de données nouvelles concerne en particulier les inhibiteurs de SGLT2 (iSGLT2) , avec des "preuves d’efficacité de cette classe chez les patients atteints de pathologies cardiovasculaires ou rénales". Cela permet "d’envisager un positionnement préférentiel de ces médicaments chez de nombreux patients DT2", affirme la société savante en soulignant que c'est déjà inclus dans les recommandations internationales.

En France, cette classe de médicaments n'est toujours pas disponible, la commission de la transparence (CT) de la Haute autorité de santé (HAS) continuant, à chaque évaluation d'un iSGLT2, d'émettre un avis défavorable au remboursement, rappelle-t-on (cf par exemple dépêche du 08/04/2019 à 17:19).

Malgré cela, "il nous a paru indispensable, à travers ce document d’actualisation, d’éclairer les confrères sur l’intérêt et le positionnement de cette classe, commercialisée aujourd’hui dans plus de 100 pays dans le monde", explique la SFD, qui affirme aussi vouloir "aider" la HAS dans son travail d’actualisation des recommandations.

Pour le Pr Hélène Hanaire, présidente de la SFD, cette absence "constitue pour les patients une véritable perte de chance". La SFD avait déjà exprimé son désaccord sur la position de la HAS en mars dernier en amont de son congrès annuel, rappelle-t-on (cf dépêche du 21/03/2019 à 15:53).

Les études récentes conduisent à réviser la place des iGLT2 et des GLP-1 dans plusieurs indications. Dans la maladie rénale chronique, "la priorité dans le traitement de seconde ligne, après la metformine, va aux iSGLT2" qui ont démontré un effet protecteur. Et en cas de contre-indication ou de mauvaise tolérance, la SFD recommande un analogue du GLP-1 ayant démontré un bénéfice sur l’excrétion urinaire d’albumine.

Dans l'insuffisance cardiaque, là aussi la priorité va aux iSGLT2 ayant fait leurs preuves dans cette pathologie, et en cas de contre-indication aux GLP-1 (mais seulement quand la fraction d'éjection est supérieure à 40%). Si aucune de ces classes ne peut être donnée, un inhibiteur de la DPP-4 ayant montré sa sécurité d'emploi dans cette maladie est recommandé.

Enfin, chez les patients ayant une maladie cardiovasculaire avérée, "le traitement de seconde ligne est un GLP-1 RA ou un iSGLT2 ayant apporté la preuve d’un bénéfice cardiovasculaire".

Mais hors de ces pathologies, dans les situations dites "communes", quand la metformine seule est insuffisante, c'est l'ajout d'un inhibiteur de la DPP4 ou d'un sulfamide qui est recommandé, en privilégiant la première classe qui a moins de risque de prise de poids et d'hypoglycémie.

Puis, au moment d’instaurer un traitement injectable, ce sont désormais les GLP-1 qui sont privilégiés par la SFD, au détriment de l'insuline, pour des raisons de bénéfice cardiovasculaire, de tolérance, d'effet favorable sur la perte de poids et d'effet plus marqué sur l'hémoglobine glyquée (HbA1c) tout en évitant les hypoglycémies.

Quand une insuline basale doit être prescrite, la SFD préfère un analogue à une insuline NPH car il y a moins d'hypoglycémies. Les insulines de nouvelle génération (glargine U300 [Toujeo*, Sanofi] et degludec [Tresiba*, Novo Nordisk]), "similaires d’un point de vue clinique", ont un bénéfice "modeste" sur les hypoglycémies nocturnes et un coût un peu plus élevé qu'un biosimilaire de glargine U100 et sont donc réservées à des "situations individuelles".

Lors de l'instauration d'une insuline basale, la recommandation est de garder la metformine mais d'arrêter progressivement les autres antidiabétiques, y compris le GLP-1 puisque si l'on change de traitement c'est qu'il s'est montré inefficace. Seule exception: si le GLP-1 a apporté une perte de poids significative et s'il y a une maladie rénale ou cardiovasculaire.

La SFD fait également des recommandations sur les objectifs glycémiques, considérant qu'ils doivent être "affinés en fonction du profil des patients". C'est l'HbA1c à moins de 7% qui est la règle générale mais les auteurs de ces recommandations estiment que chez un patient nouvellement diagnostiqué, on peut tenter de viser moins de 6,5%.

A l'inverse, chez les patients âgés fragiles ou dépendants présentant une espérance de vie limitée, un seuil à 8% est suffisant.

0 notes

Text

Hanair Mechanical Ramps Up Service Amidst Scorching UK Heat Waves

http://dlvr.it/R8bQvf

0 notes

Text

Hanair Mechanical Ramps Up Service Amidst Scorching UK Heat Waves

http://dlvr.it/R8bQrY

0 notes