#games criticism

Text

Getting whiplash going back to Armored Core VI after playing Starfield

Starfield trips over itself letting you know all of the quests are chill and good actually. The choices in dialogue range from doing a good deed to doing a good deed… for money😈. The only way to join the Space Pirates is to be offered the chance to go undercover first, making sure you see the Pirate but you’re a good guy option. If a persuasion check with someone fails, leaving you only with the prompt [Attack], your companion will say something to the effect of “woof, that was rough. But you did what you had to do.”

The most recent mission I finished in Starfield was for the United Colonies. You stand in front of a council of bureaucrats trying to convince them to hand over banned archival weapon data. This could help stop a small but growing danger to the galaxy. The council argues that it could also lead to that weapon falling into the wrong hands - It was locked away for a reason. It’s a great moment because it was the first time a character in starfield stood up and said to me No, you are in the wrong here, your research could lead to the weapon data leaking, civilians will be put it danger. ALERT. oh no. ALERT. Just as this conversation is happening an entirely contained but also extremely dire attack occurs. ALERT. You rush out and save the day. The threat is proven to be real and the data is necessary. No more questions about is it the right thing to do. Forget about all that other stuff we brought up, you were right. The whole council apologizes to you profusely. Here, take the nuclear launch codes, and here’s a thousand credits as an apology for insinuating that you weren’t the galaxy’s goodest bestest boy.

Mission 1 of Armored Core 6 is called “Illegal Entry”.

In mission 4 “Destroy the transport helicopters” the helicopters are just that. No weapons. Trying to run from you. The rubiconians who stand between you and the helicopters are defending their families. During the fight the enemies bark about you being the bad guy. After the mission your Dad calls you and says “It’s just a Job 621. All of it.” Throughout the entire game you are flooded with voicemails, calls, voices in your head, that all have an opinion on whether what you’re doing is good or bad or just a job.

Starfield is telling you not to think about it too hard. Armored Core is telling you to think about it. A lot. Screaming at you to think about it. What are you doing. It’s not just a job. The game is talking about your actions through all sorts of different lenses.

It’s stepping out of a lazy river and then immediately riding down Niagara Falls in a barrel. Sometimes literally. You see the same safe boring landing cutscene a million times in Starfield. Twice 621 has packed themselves into a barrel and yeeted it into danger.

#gaming#writing on games#armored core vi#starfield#games criticism#game design#fromsoft#Bethesda#621#writing#ac6#armored core 6#videogame essay

3K notes

·

View notes

Text

Abandon All Delusions Of Control

this is another cross-post. which is funny because I've paid for a domain name redirect to my tumblr since like 2016.. i never know what site is gonna explode these days. less people follow me here than anywhere but this write ups been passed around so...

I've been playing Dragon's Dogma 2 and while I'd love to talk about gameplay or interesting moments, the game's found itself something of a cultural lightning rod. It is a game with many friction points arising in a cultural moment where gamers are, perhaps more than ever, convinced that "consumers" are kings.

Dragon's Dogma 2 is not readily "solvable" and you can't min-max it. You will make mistakes. You will be scraped and bruised and scarred. Pain is sometimes the only bridge that can take us wher ewe need to go. And gaming culture, fed the lie of mastery and player importance, does not understand that scars can be beautiful. I love this game. I think it's a miracle it came out at all.

I also think in spite of the success it's found… that 2024 might be the worst possible year for it to have released.

Let's ramble about it..

It's easy to feel like Hideaki Itsuno and his team miscalculated the amount of friction that players are willing to endure and while I don't think that's true (he didn't miscalculate moreso stick to his particular vision) it certainly appears that we've reached a point in gaming where players, glutted on convenience, don't really know what to do when robbed of it. I've heard folks complain that they can't sprint everywhere or else balk learning that ferrystones required for fast travel cost 10,000 gold as if these shatter DD2 into pieces. I'm vaguely sympathetic to these concerns but at the same time they seem to spring entirely from a lack of understanding of the game's design goals. Much like how folks demanding a traditionally structured RPG narrative from an Octopath game misunderstand what that team is trying to do, players asking to sprint through the world or teleport with ease fundamentally misunderstand what Dragon's Dogma wants. The world is not a wrapper for a story. It is the story. Dragon's Dogma is a story factory whose various textures create unprecedented triumphs and memorable failure.

It is crucial to the experience to allow both of those to occur and live with whatever follows.

I'm always cautious of talking like this because it can come off as smug or superior but I think ultimately that's the truth of the matter here. This was not a well-played franchise before now and even if it's a AAA title, there's a way in which this game is meant to elide most AAA open world trends. You are expected to traverse. If you want relatively cheap and faster travel, you're meant to find an oxcart and pay the (quite modest) fee to move between trade hubs much like you would pay for a silt strider in Morrowind. Even if you do this, you could be ambushed on the road and in the worst case the ox pulling the cart can be killed. Something being "possible" in a game doesn't always mean it is intentional but Dragon's Dogma continually undercuts the player's ability to avoid long treks. Portcrystals, which act as fast travel destinations, are limited and ferry stones (while not prohibitively expensive compared to weapons and armor) are juuust expensive enough that you need to consider if the expense is worthwhile. Once is happenstance. Multiple times is a pattern. And the pattern in Dragon's Dogma is to disincentivize easy travel. It screams of intent.

Something I could not have imagined playing games growing up is the ways in which even a decade (or two) could lead to radically different attitudes on what games should provide. That's an audience issue to an extent but it's also something games have brought upon themselves. The "language" of an open world game has been solidified through years climbable towers, mini-map marked caves, and options to zip around worlds. When a game deviates from that language, the change is more noticeable than ever.

Hell, even Elden Ring (perhaps the closest modern relative to Dragon's Dogma) allows you to warp between bonfires and gives you a steed to ride. But that's also a much larger game! DD2 is not a large game and the story is not long. Yes, you can spend untold hours wandering about into nooks and crannies but a trek from one end of the world to another is still significantly shorter than bounding through most open worlds and a run through the critical path reveals a speedy game. Not as speedy as the first but brisk by genre standards.

exploration is the glue that binds the combat and progression system in place. Upgrading armor and weapons requires seeking out specific materials and fighting certain monsters. Gathering the funds for big purchases in shops mostly comes from selling your excess monster parts. The entire game hinges on the idea of long expeditions where you accrue materials and supplies on the road and then invest that horde one way or another once you return to town. It's not simply a matter of mood and tone for you to trek throughout the world without ease. The gameplay loop is built around it.

There's another complicating factor that I'm less interested in diving into and it's the presence of certain microtransactions at launch. Principally I'm against MTX in single players games, particularly conveniences of which most of DD2's microtransactions are. But I also think there's been a fundamental misunderstanding of what many of these are. Among the biggest things I've heard (repeatedly!) is that you can pay real life money for fast travel but that's not true. You can buy a single portcrystal offering you one more potential location to warp to. It's a one-time purchase and the only travel convenience offered. This has transformed, partly because of people's lack of familiarity with Dragon's Dogma's mechanics, into a claim that you can pay over and over to teleport around. I think that assumption reveals more about the general audience than anything else.

I think it is worth entertaining a question: does the existence of this extra port crystal signify a compromising of the game's goals regarding travel? That's not a discussion that folks seem to be interested in having—instead opting for more emotional and reactionary panicking—but it is the most interesting question. On face the answer is yes and that raises the follow up question of whether or not the developers had knowledge this convenience (though one-off) would be offered to players. If so, did that knowledge affect how they designed the game? Even slightly? It seems rather clear to me that these purchases are a publisher decision; there's nothing in the game's design that suggest the dev team wants players to have access to an extra portcrystal. As we've established it's quite the opposite!

They want you to haul your fucking ass around and get jumped by goblins, buddy.

Which is many words to say that as much as I care about microtransactions from a consumer standpoint, the way in which they undermine Dragon's Dogma 2's goals is a fair reminder of the ways in which they hurt developers. Ultimately, I do think that these purchases are ignorable and in that sense (combined with the misinformation surrounding them) I'm a little burned by the consumer-minded discussion. Doubly so because of the way it feels, at least in part, tied into a certain kind of rhetoric that's been on the rise lately. Instead, I find myself drawn to the question of the damage they do the devs and if more onerous plans actually would force their hands into undercutting portions of their own designs. The shift of many series into live-service chasing suggest so but even as I entertain these thoughts I don't get the sense that Itsuno and his team were forced to reshape their game world to encourage these microtransactions. The world is as they want.

If it wasn't, they wouldn't make it so failing to act quickly in a quest to find a missing kid stolen by wolves could end with you being too late. They wouldn't make it so buying goods from an Elven shop without an interpreter was a hassle. It's present in Every Damn Thing!

More interesting to consider is why this particular game became such a lightning rod of passion when I'm going to assume that most people caught up in the discussion have no particular fealty to the series. The answer is a combination of factors but there's something about the genre that ignites the panic we're seeing as much as the culture moment we're in. When people try to explain that these MTX purchases are not needed, it's confused for approval of their inclusion but that's not something we need to grant. I don't think anyone wants these things here and when they say "you don't need them" they are referring to the more complex thought that the game is better played without them. But this is not heard because the idea that you'd want to opt into friction and discomfort is not something that the general audience is likely to understand. They're wired against it. They crave ease.

not everyone, mind you. DD2's enjoyed a lot of excited reactions (there's tons of folks who like this game as it is and are happily playing it) but it has faced plenty of folks railing against "bad" design choices but the fact remains that those "bad" choices were intentional.

I'm writing about this stuff instead of, say, the wild journey I took solving one of the Sphinx's riddles because the immediately interesting thing about Dragon's Dogma 2 has been what it's become as a cultural object. It is a game suffering from success. Never designed for a general audience or modern standards but thrust into their hands due to Capcom's ongoing renaissance. Dragon's Dogma is a fine game whose cult status is well earned but the reason DD2 garnered this attention (and therefore becomes a hot-topic game) has as much to do with Capcom's ongoing success rate as anything else. In some ways, it actually IS a good time to release a game like Dragon's Dogma 2. There's certainly a curiousity in place. Partly borne of goodwill and also from folks' genuine desire to try something new.

and yet, we're in a odd moment in games. consumer rights lanaguge, having been fundamentally misunderstood and reconfigured by gamers as a rhetoric for justifying their purchase habits (I'm paying the money! why can't the game do exactly as I demand!?) has stifled many people's ability to have imaginative interpretations of gameplay mechanics. they don't ask "what is this thing doing as a storytelling device" (which mechanics are!) and rather default to "what is this thing doing to me and my FUN and my TIME". which are not bad questions but they also misunderstand the possibility space games have to offer. While we can attribute some of the objections that has arisen to players' thoughts about genre itself and the way in which Dragon's Dogma positions friction as a key gameplay pillar, the fact of the matter is that we would not be having such spirited discussion about these things in, say, 2017. not that things were great back then, but I think the audience is worse now in many, many ways. sarcastically? I blame Game Design YouTube.

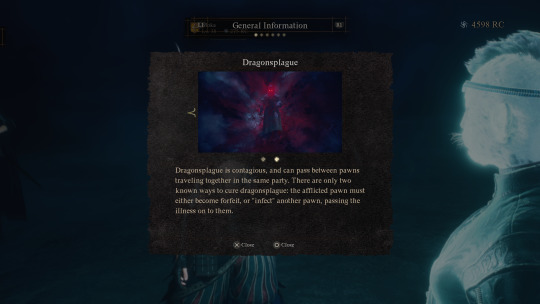

Even if there were no microtransactions, we'd still be having a degree of Discourse thanks to a key game mechanic: Dragonplague. It is a disease that can afflict your Pawn companions which initially causes them to get mouthy and start to disobey orders. If you notice these signs (alongside ominous glowing eyes) then your Pawn has been infected and you're expected to dismiss them back to the Rift where that infection can spread to another player. The game gives a pop up to the player explaining this the first time they encounter the disease. However, some players have ignored that warning and found a dire consequence: an untreated Pawn can, when the player rests at an inn, go on an overnight rampage that kills the majority of NPCs in whatever settlement they are in. This includes plot-important characters. The reaction's been intense. Reddit always sucks but man… just look…

I understand some of the ire. It's a drastic shift from your pawn being a bit ornery to instantly killing an entire city. On the other hand, the game does warn of potentially dire consequences if a Pawn's sickness is ignored. Players have simply underestimated the scale of that consequence. Surely no major RPG would mass murder important characters and break questlines! We're in post Oblivion/Skyrim world. Important NPCs are essential and cannot be killed, right? Well, wrong and this is another way in which Dragon's Dogma chases after the legacy of a game like Morrowind more than than it adapts current open world trends. This is a world where things can break and the developers have decided that they are okay with it breaking in a very drastic way. It's hard to think of anything comparable in a contemporary game. We don't really do this kind of thing anymore.

The result has been panic and a spread of information both helpful and hopelessly speculative. Is your game ruined? Well, maybe. There is an item you can find which allows for mass resurrection but that's gonna require some questing. But some players also say that you can wait a while and the game will eventually reset back to the pre-murder status quo. What's true? Hard to know. Dragon's Dogma doesn't show all of its cards and won't always explain itself. We know entire cities can be killed. We know that individual characters can be revived in the city morgue or else the settlement restored (mostly) with a special item. Dragonplague is detectable and the worst case scenario is, to some extent or another, something that the player can ameliorate. Those are facts but they don't really matter.

That's because players issue (panick? hysteria?) with dragonplague is as much to do with what it represents as what it does. Players are used to the notion of game worlds being spaces where they get to determine every state of affair. They are, as I've suggested before, eager to play the tyrant. Eager to enact whatever violences or charities that might strike their fancy. They do this with the expectation that they will be rewarded for the latter but face no consequences for the former. Dragonplague argues otherwise. No, it says, this world is also one that belongs to the developers and they are more than fine with heaping dire consequences on players. Before the dragonplague's consequences were known, players were running around the world killing NPCs in cities because it would stabilize the framerate. They're fine with mass murder on their own terms. they love it!

This is made more clear when we look at how Dragon's Dogma handles saving the game. While there are autosaves between battles, players are expected to rest at inns to save their game. This costs some gold, which is a hassle, but the bigger "issue" is that they only have one save slot. Which means that save scumming is not entirely feasible though not impossible with a bit of planning. What it does mean, however, is that the game is saved when a dragonplague attack happens. you have to rest at an inn for this to trigger. which saves the game. They cannot roll back the clock. The tragedy becomes a fact. It's not the only time Dragon's Dogma does this. For instance, players can come into possession of a special arrow that can slay anything. When used, the game saves. Much like how players are given a warning about dragonplague, they're warned before using this arrow: don't miss.

If you do? that's a real shame. The depth of this consequence is uncommon in today's gaming landscape. Games are mostly frivolous and save data is the amber from which players suck crystallized potentialities. Don't like what happened? No worries. Slide into your files and find the frozen world which suits your proclivities. You are God. In Dragon's Dogma, you are not god. The threads of prophecy can be severed and you must persist in the doomed world that's been created. The mere suggestion is an affront. The fact that Dragon's Dogma has the stones to commit to the bit in 2024 is essentially a miracle.

It's easy to boil everything I'm saying down to "Dragon's Dogma is not afraid to be rude to the player" but that doesn't capture the spirit of the design. It invites players to go on a hike. It makes no attempt to hide that the hike is difficult. But that's the extent of it. It offers little guidance on the path, doesn't check if you're a skilled enough hiker. Your decision to go on the hike is taken as proof of your acceptance of the fact that you might fall down.

This is not unique to Dragon's Dogma. In fact, this is part of the appeal (philosophically) of a game like Elden Ring. The difference being that even FromSofts much-lauded gamer gauntlets (excepting perhaps Sekiro, conincidentally their best work) offer more ways to adjust and fix the world state to the player's liking. Even the darling of difficulty will offering you a hand when you fall. Dragon's Dogma is not so eager to do so. In a decade where convenience is king for video games, that represents both a keen understanding of its lineages and a shocking affront to accepted norms and expectations.

The core of Dragon's Dogma, the very defining characteristics that earned it cult status, are the same things that have caused these modern tensions. It is both a franchise utterly consistent in its design priorities and entirely out of touch with the modern audience. Dragon's Dogma 2 has come into prominence during a time where imaginative interpretation of mechanics is at an all time low and calls for "consumer" gratification are taken as truisms. It is a game entirely at odds with the YouTube ecosystem and the very things that give it allure are the tools that have turned it into a debated object.

This flashpoint of discussion is proof of Dragon Dogma 2's design potency. It's also a sign of the damage that modern design trends have done to games as whole and the ongoing fallout that's come from gamers learning design concepts without really understanding what designing a game entails. And, uh… I dunno respond to that or how to end this. That's both very cool but it also bums me out. Dragon's Dogma 2 is a remarkably confident game but games are long beyond the point of admiring a thing for being honest.

35 notes

·

View notes

Text

Games Nobody Plays

I spent ten hours playing a wizard game from 2014 with 4 concurrent steam players and ended up writing a patreon article about how capitalism wants us to believe we'll never die. I say lots of melodramatic shit like:

Learning to read by looking constantly for the next drip in the feed is a kind of self-fulfilling prophecy, a mutually maladaptive system where we trick ourselves into thinking that one day — one day! — we’ll finish running up this infinite treadmill, check off all these experiences from our to-do list, and get a chance to go back to the old favorites we love. In the process, we demand the next drip and defer all our favorite objects until we’re finished with next week’s experiences. It could go on forever! Everything is both fleeting and perpetual. We’ll never run out of culture, and we’ll never run out of time, and we’ll stay young forever and never ever die.

and I also talk about these freak carrots:

check it out.

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

wild watching games criticism, real actual games crit without the shit of influencers and Geoff Keighley and sponsorships and the sort just like

Die

And its just because it doesn't make money in the billions, as if the cultural benefit is meaningless

130 notes

·

View notes

Text

Gender in Games that Aren’t About Gender

Imagine for a moment that you’re ten years old. You’ve just got your hands on the latest Pokémon game and after loading it up, watching the animated intro sequence, and selecting “New Game,” you’re quickly confronted by a choice: are you a Boy or a Girl? Cut to, INTERIOR, DAY, FOUR YEARS LATER. You boot up a copy of Fallout New Vegas for the PS3 that you acquired for twenty of your hard earned Canadian dollars. You’re kinda bummed you couldn’t find a copy of Fallout 3 because you don’t yet understand how much better the game you’re about to play is than that one. You once again hit New Game, and this time you immediately get shot in the face before are once again presented with The Choice. Cut to, INTERIOR, DAY, SIX YEARS LATER (I think). You boot up a copy of Fire Emblem: Three Houses. You get the picture by this point. The cuts come faster now. A new Pokémon game. The Choice. An old Pokémon game on an emulator. The Choice. An old Fire Emblem Game. The Choice. Genshin Impact. The Choice. Honkai Star Rail. The Choice. Prey (2017) on three separate occasions. The Choice. In none of these games does the gender of the player character radically alter the narrative of the game. Yet, choosing a gender is both the first act of player agency as well as the first act of player expression in each game. In Pokémon, you pick your gender before you even pick a single one of the eponymous little creatures. Despite being largely irrelevant, gender is nonetheless there, right at the very beginning.

On its own, this probably says something about the importance of gender to us as players and to the societies which produced these games. The social conventions of gender are ones we navigate on a daily basis, regardless of how enthusiastic we are about them. Being gendered is the social default. We are not only forced to engage with gendered relations by circumstance, but expected to as a matter of course. Given this reality, it would probably feel odd to choose a gender at any other point in the narrative because that would then seemingly make gender contextually relevant to whatever circumstances prompt the choice. Get gender out of the way first and we can just move on from it. For the rest of the game, it becomes purely aesthetic.

This is, I think, a kind of escapism. In games that aren’t about gender that nonetheless allow you to choose the gender of your player character, gendered relations are largely disregarded in order to fulfill the fantasy of a world where gendered expectations are minimized or absent. Female Robin in FE: Awakening is just as competent a tactician, mage, and swordswoman as Male Robin. Playing as a woman in Fallout New Vegas doesn’t preclude you from the skills to role play a hard drinking boxer with a penchant for gambling. Your gender in a Pokémon game doesn’t preclude you from catching whichever Pokémon game you want nor will the NPCs generally judge you for your choice of little guys. Cynthia won’t scoff at a male Pokémon trainer with a team of exclusively adorable Pokémon nor will Saturn tell a female Pokémon trainer that guys would like her more if she didn’t only use scary Pokémon and smiled more. These worlds spare us from the worst gendered interactions of our own world. Or at least, they do so long as you’re cisgendered and heterosexual.

Let’s go back to Robin, the player character in FE: Awakening. Through the course of the story, you meet a character named Tharja who is obsessed with Robin. Tharja’s obsession has romantic overtones which do not change regardless of Robin’s gender. She seems just as interested in keeping Female Robin to herself as she does Male Robin. However, only Male Robin has the option to enter a romantic relationship with her. In fact, you cannot romance any of the female characters as the female version of the player character. Likewise, the Male protagonist is limited to only romancing female characters. While the player is given agency over Robin’s gender, they are denied agency over their sexuality. Robin is immutably heterosexual. Here, the escapist fantasy of a gender-lite world is utterly derailed if your romantic interests are not heteronormative. This leads me to question how much agency the player is actually being given when making The Choice. Am I expressing myself within the narrative and the play-space if I’m a lesbian being forced to play the role of a straight girl? That feels a little bit too close to the reality of being closeted to be escapism anymore. I love FE: Awakening, it’s easily one of my favourite games of all time. This has always left a bad taste in my mouth.

Now, I’m not trying to say that all games that allow you to choose the gender of your character are as, let’s say, limiting as FE: Awakening. Fallout New Vegas allows you an impressive amount of freedom expression regarding gender, sexuality, and presentation. Later FE games have reluctantly added some same-sex romance options, but generally fewer M/M options than F/F ones. Pokémon is, for the most part, utterly unconcerned with romance. No, the thing I’m trying to point out is that gender is always lurking in the background of these games. While we make The Choice at the very beginning, that choice continues to define our interactions with the game and the narrative outside of the text itself. For instance, imagine going to make The Choice only to find that… there’s no option to pick your gender. After all, The Choice is always Boy or Girl. If neither of those are you, then your agency and expression as a player are immediately hamstrung. Your avatar is no longer indexed to you. Of course, not every game will explicitly say, “THIS ONE IS A MAN THAT ONE IS A WOMAN.” But gender is so deeply ingrained in our social world that they don’t have to. You can decide that your Male Robin is actually a butch lesbian who uses he/him pronouns, but the gendered signifiers of the game are such most people would look at your avatar and decide that they’re man. That head canon cannot be represented through player expression. As far as the game is concerned, that Robin is a man.

I don’t want to claim I’m being particularly novel or offering new insight into the nature of gender and games. Rather, I want to highlight some ways in which gender reasserts itself during the interactions between player and game because they illustrate how important The Choice can actually be to the experience of the game. Gender is, to borrow a phrase, a spectre haunting these games. We do not experience them divorced from gender. Instead, the degree to which gender is part of our gaming experience depends on how attuned we are to gendered relations outside the play-space. Those who, for whatever reason (usually situatedness, let’s be honest), are more readily disposed to think critically about gendered relations are more likely to encounter friction in the supposedly frictionless fantasy. However, even in cases where the player character leans more heavily towards being a character with goals, beliefs, and relationships independent of the player, the spectre of gender still looms.

This whole essay is the result of a comment on another post of mine which argued that the gender of the player character in Prey (2017) was purely cosmetic because it doesn’t change the text of the game in a meaningful way. This is technically true. The player character does all the same things and has all the same relationships. Hell, gender doesn’t even change the character’s name. They are always Morgan Yu. This was, until pretty recently, also more or less the case in Genshin Impact, a game about which I’ve written before. The player can name their character whatever they want (though they do have a canonical name mentioned in-game) and the gender of the Traveller is irrelevant to just about every story beat and relationship, with one sort of notable exception. Both Morgan and the Traveller are characters in a more robust sense that the previous games we’ve discussed. Actions Morgan takes at the behest of the player that differ from their pre-established character are accounted for in the text. The Traveller gets to make very few meaningful choices, as the player’s expression and agency are limited to extra-canonical choices like team composition and character builds (in cutscenes, the Traveller literally uses to default ‘Dull Sword’ to fight literal gods). In both games, the player character is more character than player avatar, at least as far as the narrative is concerned. Yet, in both games we are still confronted with The Choice.

Why give the player agency over Morgan or the Traveller’s gender but not, say, their appearance? Or the kind of person they used to be? Why present this choice that is seemingly irrelevant to the play experience? The simple answer is player expression. Even if both characters lean towards being actual characters, they are still the avatar for the player’s action and the expectation many gamers have is that we should have some agency over that avatar. While there may be no textual meaning influenced by The Choice, it still allows players to express something within the dialogue between game and player. My choice to play Morgan Yu as a woman or the Traveller as Lumine means something to me even if not the game. What that meaning is depends on the player, but it is inevitably informed by our lived experiences of gendered relations. I pick the female player characters because, even if the contents of their character are identical to their male counterpart, I nonetheless see myself reflected better in them. Here, we need to introduce a technical concept: distraction. For the distracted player, this is as far this relationship might go. I pick girl because I’m girl, done. I aced The Choice. However, the attentive player may find that the rest of the game is actually coloured by The Choice.

What then, do I mean when I use the term ‘distraction?”

HA YOU THOUGHT YOU’D GET THROUGH THIS ENTIRE MESS OF AN ESSAY WITHOUT ME CITING PHILOSOPHICAL SOCIAL CRITICISM? YOU THOUGHT WRONG, PUNK.

In his essay on aesthetics, “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction,” social critic Walter Benjamin offers an account of distraction. He describes distraction first with regards to architecture:

Architecture has never been idle. Its history is more ancient than that of any other art, and its claim to being a living force has significance in every attempt to comprehend the relationship of the masses to art. Buildings are appropriated in a twofold manner: by use and by perception-or rather, by touch and sight. Such appropriation cannot be understood in terms of the attentive concentration of a tourist before a famous building. On the tactile side there is no counterpart to contemplation on the optical side. Tactile appropriation is accomplished, not so much by attention as by habit. As regards architecture, habit determines to a large extent even optical reception. The latter, too, occurs much less through rapt attention than by noticing the object in incidental fashion. This mode of appropriation, developed with reference to architecture, in certain circumstances acquires canonical value. For the tasks which face the human apparatus of perception at the turning points of history cannot be solved by optical means, that is, by contemplation, alone. They are mastered gradually by habit, under the guidance of tactile appropriation. (Benjamin 2007, 240)

Here, he argues that architecture is consumed through our tactile use of it. Buildings, especially those we have to inhabit regularly, are too large to optically perceived. Between their sheer size and their multifaceted shape, it is impossible to perceive them in their entirety. However, by moving through them, we slowly gain a habitual understanding of them which informs, in turn, how we perceive them. As an example, I move through my apartment not so much by sight but rather by muscle memory. I know where everything is, so I can navigate from the living room to the bedroom while, say, watching a Youtube video. I can navigate the space while in a state of distraction. So when Benjamin, and thus I, use the term distraction, I am referring to the specific way in which habit allows us to move through a space without consciously navigating it, thereby freeing up cognitive capacity to be distracted with something else. Got it? Good, now let’s apply this analysis to video games.

Question: can you navigate the digital space within a video game in a state of distraction? Yes. I can navigate the Team Fortress 2 map ‘2Fort’ completely in a state of distraction because I spent hundreds of hours of my precious youth wandering around it while invisible as the Spy. However, I cannot navigate all virtual spaces by habit because, like real spaces, I first need to habituate myself too them. When I talk about consuming video games in a state of distraction, I want to make it clear that I do not mean virtual spaces. I am talking about the gestalt experience of playing a video game.

For instance, when I pick up my PS4 controller, I do not need to look at the face buttons to know where the button that opens and the button that closes are. I don’t need see the X on screen and then find the X on the controller to press X. I don’t need to even be told what X does because X always opens. I see X, I know I’m opening or selecting something. This is the kind of habitual action that I can preform in a state of distraction. However, the kinds of habits we form around games are not limited to input mechanisms. We can also form mechanical and interpretive habits. When I’m playing Genshin Impact, I don’t consciously think about whether I should use a normal attack, a skill, or an ultimate when I’m in the heat of battle. Instead, the mechanical habits I’ve formed kick in and my fingers react to whatever my eyes process. The more habitual those reactions are, the leeway I have to be distracted, which allows me to free up more cognitive capacity to process things like positioning and team rotation. Interpretive habits are a bit more difficult to grasp.

First off, what do I mean by an interpretive habit in the first place? Here, Genshin is again instructive. If you’re unfamiliar with the game, look through these character splashes and try to guess what element each character is associated with:

Left to right, top to bottom (hehe): Kokomi - Hydro, Nahida - Dendro, Shenhe - Cryo, Hu Tau - Pyro, Raiden Shogun - Electro

Even without me having told you that Genshin Impact has seven elements and each one is associated with a symbol and a colour, you could probably guess which element each character is associated with. This is an interpretive habit, or heuristic. It is a method through which we can offload cognitive capacity by reflexively interpreting a sign or symbol. This has mechanical utility in so far as it gives us an idea of what a character might be mechanically useful for. Hu Tao can probably set flammable things alight, Shenhe can probably freeze water, and Kokomi can probably douse flames. That we can use these interpretive habits to such great practical effect speaks volumes outside of video games as well, but that is a story for another time (a good friend and colleague actually wrote an entire thesis on heuristics and their effect on political polarization). What is more relevant to the argument I’m (slowly) making, is that interpretive habits allow us to engage with the text of a game in a state of distraction.

When the player presented with The Choice, it acts as a kind of assurance that they are entering the frictionless gender-lite world of fantasy. However, this illusion only works on those who are either willing to be taken in by it and on those who don’t know any different. If your experience of the gender in the social world is frictionless, you can easily slip into a fantasy world where gender is completely irrelevant. Likewise, if you want to be distracted, then simply accepting The Choice at face value allows you suspend disbelief. In both cases, interpretive habits are the mechanism by which the illusion goes unchallenged. For those who are privileged enough to be ignorant of gendered social experience, those habits are formed in the real world while for the rest of us they are formed through the consumption of media. The end result is the same: we can move through the text of the game unhindered by the cognitive burden of gender.

This interpretive ignorance, willful or not, offers a negative formulation of the argument I’m trying to make. By utilizing interpretive habits to distract ourselves from the real world implications of gender, we get to experience a game in a particular way. Recall this portion of the quote from Benjamin:

Tactile appropriation is accomplished, not so much by attention as habit. As regards architecture, habit determines to a large extent even optical reception. (Benjamin 2007, 240)

If we transpose this logic onto games, we can replace tactile habit with interpretive ones and optical reception with how we relate to the text of the game as a whole. This is to say, the interpretive habits we employ in the process of navigating the text of the game inform the impression that the game leaves on us. If you engage with the fantasy of a frictionless gender-lite world, the impression the game leaves will be likewise gender-lite. If we accept this as the negative formulation of the argument, then the positive one would suggest that suspending that interpretive habit will allow us to view the game through the lens of gendered relations. This isn’t to say that we’re reading into the text gendered relations that are not present, but rather that our reading of the text is informed by our understanding of gendered relations in the social world.

We could end things there and move on with our lives, but I think that an illustrative examples is necessary to really drive home the point. Consider the following passage (which I wrote myself):

“I don’t think you’re listening to me, Meyer.” I’m reaching my breaking point now. “This is unsustainable—we are unsustainable. I’m ending things.”

Picture the speaker as a woman and Meyer as a man. What does, “I don’t think you’re listening to me,” mean within the gendered context of this conversation? Now picture the roles are reversed. Does ‘listening’ necessarily mean the same thing? Try it with both speaker and listener as women and the listener is in tears. Try it with a female boss, face red with rage, speaking to her male subordinate. Try it with two men, sitting on the hood of a vintage car under a moonlit sky as they both weep. The words can mean different things in different contexts even though they do not change. If I really wanted to hurt you, the reader, and myself, I’d insert an entire section on Wittgenstein and language games here. But I don’t, so I won’t.

When we ignore our experience of gendered relations, we are unable to imagine new meanings for the text of a game that can only arise out of paying attention to the context gender provides. To say that Morgan’s relationship with the female Chief Engineer Ilyushin is the same regardless of which gender the player chooses for Morgan to embody is to ignore the reality that sapphic relationships are not the same as heterosexual ones. It also means rejecting the notion that a female employer entering a relationship with a female subordinate can mean something different from a male employer doing the same. Both Morgans are the same, but they are still different insofar as who we take them to be can be shaped by our understanding of gendered relations.

While it may come off as though I’m suggesting that it is somehow morally superior to be attentive to these kinds of relations, I want to emphasize that there’s nothing inherently wrong with escapism. It is everyone’s right to tune out things things which would ruin their leisure time. However, I also want to emphasize a notion I obliquely gestured at earlier: some people ignore these kind of contexts because they are generally ignorant. Art of all kinds present us with an opportunity to engage with new perspectives as well as to actively apply our perspectives to the act of interpretation. Giving up this opportunity in the name of leisure because you’re familiar enough already thank you is one thing. It’s a whole other to, say, get all bent out of shape when someone brings up gender in the context of a game that you don’t think has any gender in it because you don’t know better. Positions of privilege imply a level of ignorance regarding the experiences of marginalization. So if a person with experiences that do not occur for you says, ‘hey, i noticed a thing!’ you should probably listen to them and give their observation a fair shake because you don’t know what the fuck you’re talking about.

I’m not trying to take some moral high ground here, either. I am not immune to ignorance. Prey has a racially diverse cast of characters and Yu siblings who form the player character-primary antagonist dyad are both Chinese-Americans. Prey is also a game that drapes itself in an art-deco and mid-century modern aesthetic appropriate to its alternate timeline. These aesthetics are intrinsically bound up in periods of time and ideologies that were inherently racist. I’ve noticed this dissonance, but I don’t have the experience to make any meaningful observations about it. Instead, I mostly ignore it while I’m playing, allowing interpretive habits developed as a non-racialized person to guide me through the text. There is, no doubt, something that could be made of this dissonance as well as the general tendency of genre fiction to appropriate aesthetics from the past without much or any self-reflection. I am a queer woman and thus I do have relevant experiences of gendered relations that make me attentive to that aspect of the text. But, my whiteness further informs even these impression as race intersects with gender and sexuality in ways that I do not experience.

It is here that I think I want to wrap up this, uh, very long piece of writing. Where I to write a game, I probably would not force my players to make The Choice. I think its a bit of a cop out for having to deal with gender in any meaningful way and I don’t care for that as a feminist philosopher. It’s also exclusionary. My partner is non-binary and I’ve seen first hand how normative gendered expectations hurt them. However, since The Choice does exist and will continue to do so, I feel that interrogating how gender informs our readings of games that implement it can be both intellectually rewarding and fun. Doing so can help us understand our interpretive habits by consciously examining them, which is, I think, a good thing to do on occasion. It can also give us new ways of looking at characters which in turn can inform fan works and fan discussion. But at the end of the day, video games are a leisure activity for most and if you’re just looking for distraction, that’s fine too.

Works Cited

Benjamin, Walter. “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction,” in Illuminations, translated by Harry Zohn, edited by Hannah Arendt. New York: Schoken Books, 2007.

#claire thoughts#games criticism#this isn’t copy edited because it’s late#sorry#i’m gonna eat dinner now

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

Am I in this? I'm in this! So are lots of other cool essays about video games

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

THE SPECTACULAR LEVIATHAN

an essay about criticism and culture

ed sheeran doesn't need music critics

Rolling Stone published an article of cut content from a recent Ed Sheeran feature, in which the pop musician said, "Why do you need to read a review? Listen to it. It’s freely available! Make up your own mind. I would never read an album review and go, ‘I’m not gonna listen to that now.'"

And to some degree, Sheeran is right. Streaming services make music readily available and conjure the illusion that it's also freely given to us. We don't "need" cultural gatekeepers - such as, ironically, Rolling Stone - to tell us whether or not the newest song by Ed Sheeran is bad (that's just a deeply felt sense we hold in our bones, which Spotify or Apple Music can help us confirm at our leisure).

But like most criticism-of-criticism in this vein, Sheeran's point misses the forest for the trees. We absolutely don't need critics to tell us whether "thing good" or "thing bad," but that's not necessarily why critics even exist in the first place. In addition to that sort of mere qualitative statement, critics exist to help us understand context, like how financially deleterious the very existence of streaming services is to the artists themselves, for example, or how subscribing to a streaming service means that your music collection is never actually yours and can be revoked by the record companies at any time. Critics can help to place Sheeran in his historical context as a contemporary singer and songwriter, or offer more palatable, lesser-known alternatives to his vapid art. Critics could, if they wanted, try to situate Sheeran's songs in a political context, though I could not tell you how that would shake out to save my life.

Sheeran is not the only person to make that mistake, by any means. The idea that critics are unnecessary today except as objects of derision or agreement is popular, and the idea that criticism is only there to tell you whether "thing good" or "thing bad" is even upheld by people responsible for making sure criticism gets published to a broad audience, like IGN's executive editor of reviews.

Critics ourselves are often pushed into this narrow view of our field whether we like it or not, not necessarily out of malice but out of the harsh realities of business in the media industry. We watch as our friends and colleagues get fired from their "sure thing" jobs regularly, as outlets shutter and downsize to focus only on that which can get the greatest algorithmic return-on-investment.

Even with service journalism, the underpaid and undervalued field where writers put out dozens of how-to guides on everything from "How do I beat this level in Final Fantasy VII Remake" to "Where can I find the latest blockbuster on streaming," writers' jobs are being threatened by the looming mistake of Large Language Model (LLM)-generated content. Why pay someone to write an accurate, carefully considered guide that actually feels like a person wrote them - you know, the appeal of old chestnuts like GameFAQs guides - when you can just get a chatbot (and by extension, forced labor in Kenya) to do the work instead? At a certain level of bullshit jobs-style upper management, what's considered "efficient" is directly antithetical to human life.

But this isn't Ed Sheeran's fault, per se, nor is it really his problem. He's a point on a graph of a much broader trend.

anti-criticism in the age of disney adults

Poet laureate Karl Shapiro identified the concept of "anti-criticism" in a series of lectures delivered from October to December, 1949.1 He saw "[arguments] against criticism [as] related to a wider and more dangerous anti-intellectualism that in poetics leads to the primacy of the second-rate, and in literary politics may lead to official and controlled art." In his ensuing Poetry article, "What is Anti-Criticism?" Shapiro briefly examines the history of 18th and 19th century poetry and how it was analyzed, carefully demonstrating the values such structural and interpretive analysis upheld and how they were incompatible with contemporary 20th century poetry - and indeed, its critical apparatus.

The anti-critic takes for his quarry not only the modern symbolist poets but also the old symbolist poets like Blake; not only the modern metaphysical poets but also the old metaphysical poets; and in addition to these the polylingual poets; those who practice typographical or grammatical experiments, past or present; those who use one rhetorical figure at the expense of the other- those who are too abstract and those who are too concrete. The contemporary poet may not be tolerant of all these kinds of poetry himself, but the anti-critic would like to get rid of the lot. His measure, as I said before, is the prose semantic, and any violation of this central canon he regards as a threat to intelligibility and sanity. To the anti-critic any departure from the immediate area of the paraphrasable meaning is, moreover, a sign of wilful obscurantism. [...] A highly paraphrasable poetry is equivalent to a highly representational art, and both, in a period like ours, are liable to degenerate into escapist art.

Shapiro describes phenomena that would likely be familiar to anyone who has lived through the last decade of critical discourse around any kind of art you can imagine, from the indiscriminate uplifting of mediocre yet broadly popular "cultural products" to the bashing of art that resists easy interpretation and a sneering attitude toward the critics who attempt to analyze said art anyway. Through Shapiro we see anti-critics in those who endlessly repeat "Let People Enjoy Things" at anyone who doesn't like a superhero movie, in the throngs of gamers (and the reviewers who enabled them) who refused to let a little systemic transphobia get in the way of their Hogwarts Legacy run, and in Ed Sheeran's throwaway jab at the critics forced to listen to his pablum for less money than they should be getting for their troubles.

The anti-critic has surely evolved in other important ways away from what Shapiro observed in the first few years after World War II, just as the corporate media/art space has evolved. We see the "enthusiast" subsume more formal critics and critical outlets all the time, coincidentally as a monoculture forms around a few massive entertainment and technology corporations. In one particularly blunt example, critic B.D. McClay notes that a writer for IGN was replaced as the reviewer for the Disney+/Marvel series Loki after a single less-than-glowing review of the show. In a more recent example, replies to longtime film critic Robert Daniels's tweet panning The Super Mario Bros. Movie ranged from indifferent to derisive, with one reply telling him, "I’ll trust the reviews from people who actual [sic] play the game," together with a screenshot of IGN's 8/10 review synopsis.

We might revisit that IGN article that contends the purpose of criticism is to determine whether "thing good" or "thing bad," as it actually contends something worse: that the wide majority of things even worth talking about in IGN's eyes are broadly "good" along a sliding scale of quality from "mediocre" to "superlative." In this case, the criticism isn't even merely qualitative; it's meant to be singularly supportive or at worst ambivalent about a given cultural product. It is itself anti-criticism.

McClay (more charitably than I suspect Shapiro would have been) identifies the tendency for largely positive anti-critical writing about mass media as "a world of appreciation," not necessarily unadulterated fandom, but "essentially, a fan culture." In this dynamic, there is only people who like the thing, and the thing itself. If negativity in this world of appreciation exists, McClay explains, it does so as part of a binary: "the rave and the takedown."

an endless content™ jubilee

I remember when I first got into games criticism I heard everyone joke about the "discourse wheel" and how if you spent enough time in the industry you'd eventually find yourself back at the beginning, older, not necessarily wiser, yet experiencing many of the same arguments about a particular game or design concept yet again. The obvious punchline was someone yelling "LUDONARRATIVE DISSONANCE" and watching everyone in the discord server duck under their desks like an air raid alarm had gone off.

Since then, The Last of Us has gotten a sequel, a PC remaster, a full remake of the first game, and a whole-ass television show with a second season on the way. The discourse around that media franchise has happened in front of me not once, not twice, but like four times at this point. As Autumn Wright wrote, "there’s a new AAA catastrophe that’s weird about trans people and also The Last of Us is relevant again."

This is perhaps not the worst or wildest example of monoculture forming around us in a suffocating cloud, though. That dubious distinction goes to Disney and Microsoft, probably, as the companies attempting to gather up as much culture as they can to homogenize it, with the former going as far as digitizing actors' voices for use long after they retire in new portrayals of characters those actors first performed more than 40 years ago. Hell, it's not even the worst example in the games industry. What iteration number is Call of Duty on? Or Assassin's Creed? Or fucking Mario? Hell, we're already two deep into the reboot of God of War.

It's hardly worth saying at this point that nostalgia fuels so much of the media that we're given to consume. It's increasingly difficult to find new art or ideas in a media landscape that puts so much value on callbacks to old forms. If something isn't another superhero origin story, it's referencing a meme from 12 years ago. And it's nearly impossible to resist the ever-present pull of this strictly iterative culture: I can't lie and say I didn't thoroughly enjoy both of the above examples.

But we still need to try and cut through the overwhelm for a moment. Disney isn't a poison to the culture simply because it owns Marvel Studios or Lucasfilm. The reason for its negative impact is because of the absolute crushing presence it has in the film and television industries at large, having bought out major competitors like 20th Century Fox and nearly completely snowed out smaller film studios at the theaters. It doesn't help that the industry is consolidating in other ways with its move to streaming platforms. As Adam Conover said in a recent video about two different mergers (Live Nation and Ticket Master in the 90s and Warner Media with Discovery late last year), "one man's whims and preferences dictate which stories artists get to tell and what hundreds of millions of people get to watch."

The idea that a few rich dudes are in full control of every piece of media we consume and that the number of rich dudes who do so is actively getting smaller all the timesucks, not just for criticism's purposes but simply as someone who Consumes Content™. To my knowledge, no one has ever been explicitly asked if we want the same shit, year in and year out, only More. Nobody from Game Freak or Ubisoft ever sends out a survey like "hey are y'all tired of Pokémon or Rainbow Six: Siege seasons?" Instead, they just push them out, and let the resulting economic data do the talking: "People want more of this thing because a lot of them bought the thing when it came out." There's such a thing as too much of a good thing, especially when we're less likely (or able) to say no in the first place.

In this light, doesn't it make just too much sense that Ed Sheeran has a whole mini documentary series coming out on Disney Plus?

towards a guerrilla criticism

So what's to be done here? Aside from maybe the 🏴 most 🔥🍾 obvious 💣 (and unlikely) answers with regards to the most egregious monopolies, how can critics - who are, as a reminder, less institutionally supported than ever - or criticism even contend with Content™ backed by the most well-funded mega corps on earth and supported by hegemonically anti-critical fanbases?

Here is where I disagree most heavily with thinkers like Shapiro, who believed in retaining an elevated critical class and poetic movement with remove from the masses, and critics like McClay, who said "Opinions will become both more binary and more homogenous, and about fewer and fewer things. [...] things will get worse, whether or not they ever get better." I don't think our options necessarily have to be "remove ourselves to an academic ivory tower" or "accept that things are the way they are." We don't need to dutifully fall into line along the "rave" or "takedown" axis as McClay described.

The kind of criticism I am imagining is a criticism that is inherently and radically skeptical of (especially corporate-backed) nostalgia; a criticism that is not necessarily hostile to fans but antagonistic toward fandom as a system which undergirds larger structures of power; a criticism that is as transgressive and playful in the forms it takes as it is with the words that fill those forms. I believe we are capable of performing criticism that disappoints everyone in delightful ways.

Criticism as a weapon is not a new idea, of course. Marx is famously quoted as saying "The weapon of criticism cannot, of course, replace criticism of the weapon, material force must be overthrown by material force; but theory also becomes a material force as soon as it has gripped the masses." More modern philosophers and theorists, like the Situationists and Bruno Latour, have written about the decline and possible weaponization of criticism as well. To a degree, that worries me. Talk doesn't just become action because the talker wishes for it real hard. There's a real possibility, no, a near-certainty, that anything that comes out of this will result in next to nothing changing. If everything is part of the cycle of discourse, including conversations on how to break the discourse, what hope do we have?

The alternative to facing the leviathan and losing at the moment seems to be more or less doing nothing, which to me is more unbearable than all the pranks of all the cringe-ass culture jammers of the 90s and 2000s combined. At what point does quiet dissent simply morph into complicity?

***

Shapiro, Karl. “What Is Anti-Criticism?” Poetry, vol. 75, no. 6, 1950, pp. 339–51. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/20591169. Accessed 9 Apr. 2023.

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

Now that I've been done with Tears of the Kingdom for like 2 weeks, my thoughts on it have solidified. Spoiler free thoughts: the major elements of the game (dungeons, bosses, main quest) are a lot better than Breath of the Wild, but its moment to moment gameplay leaves me wanting something more, or really something else.

Minor spoilers below.

The depths are neat but very underbaked. Without shrines or much scenery to explore, it felt like a gear dump. Like you go down there for gear, bombs, and zonaite and that's about it beyond the ocassional hideout. The sky islands are very cool, but there are too few of them, and the ones that are there are too samey. There are like 5 separate islands that are essentially copypasted. You know the ones: there's like a crooked x bit and a launcher in the middle, a gacha dispenser, and a "fetch the crystal" shrine. The low gravity areas were very cool, but only used rarely. I could live with repeats if they're at least reskinned. But the depths and the sky islands were all visually almost identical, so no areas really stand out: the gerudo sky and the akkala sky look exactly the same, and the areas underground are also indistinguishable. Caves are fine, only one really impressed me (the big lookout landing shelter hole that leads to hyrule castle was cool as hell). Again, they're all visually indistinct, and follow the same formula (other than the eldin ones that are spicy).

It feels incoherent in a way that Breath of the Wild didn't. It's like a lot of little ideas packed together that don't necessarily mix. The shrines felt a little better than BotW's, and I'm very glad the tests of strength were gone, but most feel a bit insubstantial, like a massive snack instead of a meal (a problem in BotW too, but given the time they had, it's a shame there wasn't more done with them).

Ultrahand is really the only new ability worth a damn. Fuse is just ultrahand, and quickly becomes a routine necessity instead of a fun bonus. Ascend is just a quality of life feature outside of maybe two overworld boss fights. Recall is useful for puzzles, but rarely any good outside of that. In contrast, I used bombs, ice, and stasis all the time. Magnesis was no good, ultrahand is a straight upgrade there. I just don't really care about the vehicles. It's not what I play zelda for, and it's not what I play games generally for.

I think it's really hurt by being so similar to BotW at its core. Breath felt like a big jump forward, something new and exciting for zelda and a high water mark for open world games. TotK feels incremental, a decent refinement in some ways, and a frustrating step back in others. If it came out 2-3 years after BotW instead, that might have helped. As it is now, i don't think it will stand the test of time in a way that Breath of the Wild has. I don't feel like going back and replaying it.

It's fine. Middle of the pack zelda. Fun bosses, great final boss fight, cool story, and a few good side quests like the yiga stuff. Unfortunately, everything in the middle is kind of goopy and undefined. It slipped out of my mind as soon as I was done. Very few of the locations stand out in my memory, unlike how they did originally in Breath of the Wild. I still remember climbing dueling peaks the first time, watching the sunset in lurelin, camping on a mountainside and waiting for a dragon to come by, jumping off the great plateau for the first time. In TotK, I remember the water, lightning, and wind temple, and the underground yiga hideout. I remember fiddling with car parts and glider angles and a hot air balloon not working quite right. I remember my gerudo gf (Calyban 💙 Link) that lived in front of a cooking pot and grinding for rupees and monster parts.

I liked the idea of rebuilding hyrule and forming connections, but it didn't really work in practice. The game is left in this awkward middle ground where it's not empty enough to feel intentionally lonely, and not deep and crowded enough to feel lively. It also feels weirdly discontinguous from BotW for a direct sequel. It feels more like a do-over or retcon, like how Deltarune remixed people and places from Undertale, but it shouldn't since it's the same world, the same canon. There's very little from your previous adventure that carries over or that anyone mentions, even though it's only been a few years. The timeline between the two is very messy as well, but that doesn't really matter. It just feels off.

There's a lot to be said about how a game feels, about what it evokes and how, beyond or in tandem with the mechanics. BotW felt almost like a semi-transcendental meditation, a lonely journey through the wilderness, a piece of art with Something To Say about games, the series, maybe even life. TotK feels like a video-game-ass video game, like a lego set. If the temples and bosses were lifted from Tears and put into Breath (and maaaybe the building stuff was added as like a big expansion to BotW) I don't think anything of great value would really be lost. Some of the character work was nice, but there's not enough of it.

I really wish they would make something smaller, more inventive, and more intentional next. I want less control, less stuff, more feeling. But given the sales and praise for TotK, I sincerely doubt that will happen. Instead, we'll wait 7 more years for "another one."

And where the hell is my big bird man Kass

#i just want something new#legend of zelda#tears of the kingdom#totk thoughts#totk spoilers#games criticism#legend of zelda: tears of the kingdom

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Story You Want To See: Princess Zelda’s Narrative Arc in The Legend of Zelda: Tears of the Kingdom

Spoilers for The Legend of Zelda: Tears of the Kingdom

A piece about reviewer interpretations of Zelda's role in The Legend of Zelda: Tears of the Kingdom, as analysed by someone who has played neither BOTW or TOTK. (1,219 words)

Unlike many gamers, what I (as a bystander with no interest in any of the Zelda games besides maybe Majora’s Mask) was most curious about with regard to Tears of the Kingdom was how it would treat Princess Zelda in the wake of Breath of the Wild.

You see, although I haven’t played Breath of the Wild, I do know that quite a few people praised Zelda’s portrayal in that game. They argued that while still a princess requiring Link’s rescuing, Zelda being made the focus of the main story (as doled out through flashbacks) and having been locked up in Hyrule Castle with Calamity Ganon by her own choice gave a subversive twist to that game. As summed up by Critical Distance’s Chris Lawrence in a Twitter thread on June 17th, 2021: “…In BOTW, Link may be the playable character, but Zelda is the protagonist—the flashbacks deal principally with her character development, not Link’s. […] The entirety of BOTW […] is about Zelda’s struggle to achieve autonomy.”

I wondered: if Breath of the Wild subverted the typical hero-and-princess story and put the evil to rest, then how would Tears of the Kingdom, which comes after this destruction of the status quo, treat this newly-liberated princess, a damsel no longer in distress?

Fans said that the obvious next step was for Nintendo to give Zelda a more active role in the sequel; as a playable character or deuteragonist, perhaps, but either way, she needed to be able to enjoy the freedom won at the end of the previous game. To return to Chris Lawrence’s thread: “If Zelda is once again damselled and needs to be rescued by Link, the sequel isn’t reflecting the growth of Zelda’s character over the previous game. In other words, the sequel is failing to justify itself as a narrative continuation of the first game.”

So I skimmed through the many glowing reviews of Tears of the Kingdom, hoping to find out what had become of Zelda. At that point, I noticed something odd: reviewers seemed to have strongly conflicting interpretations of Zelda’s part in the narrative.

Many reviews were positive on the story, and some specifically cited Zelda’s role in it as a highlight. Gamereactor’s David Caballero apparently declared that “it is literally the legend of Zelda this time around” (quoted in TOTK review by Gamereactor’s Alex Hopley), and Gamespot’s Steve Watts concurs: “But more than the Sages or even Link, this story truly belongs to Zelda”. The Gamer’s Jade King expanded on this in her review, stating that “[although] Zelda isn’t playable here, […] all the discoverable memories scattered across the open world focus on her arc”, and therefore “she is still given room to shine and comes across as inquisitively capable in recruiting new allies and setting the stage for Link to vanquish evil once and for all”. Checkpoint Gaming’s Luke Mitchell likewise observes that “while [Zelda] isn’t present for your adventuring, the main questline gives you the opportunity to unlock memories, uncovering more about Zelda and her connection to Hyrule”.

But a handful of other reviewers had a very different perspective. Two specifically noted that the premise of the game involves saving Zelda: Eurogamer’s Edwin Evans-Thirlwell wrote that “Zelda […] is still fundamentally a damsel in need of rescuing”, while IGN’s Tom Marks flippantly remarked that the game is “about stopping some evil jerk (welcome back, Ganondorf) and saving Princess Zelda as usual” while pronouncing the story to be “so dang cool”. The Verge’s Ash Parrish and Press Start’s James Berich were rather more critical, stating that “Zelda, though teased as playing a more active role, has been, once again, utterly sidelined — this time in a particularly egregious way”, and “Zelda’s characterisation definitely feels like a step back from her appearance in Breath of the Wild”, respectively.

So what actually happened in the game? After looking up some spoilers on Screenrant, I’m still not too sure myself. It seems that much of the main story sees Link searching for Zelda after getting separated at the start, during the course of which the player unlocks flashbacks showing what befell the princess. These flashbacks, in turn, explain that Zelda got transported into the past, and due to various reasons ended up sacrificing herself in order to ensure that Link is able to defeat the big bad in the present day. This sacrifice involves her turning into a mindless dragon, and she is able to turn back into a human only after being healed by Link (and friends) at the end.

In short:

Zelda is absent from a large portion of the game

Zelda does have a story arc in which she demonstrates agency… by sacrificing herself to ensure that Link can play his heroic role

Without Link’s help, Zelda would be dead (and/or stuck as a dragon with no sense of self)

Hmm. I don’t know, but this sounds very much like Breath of the Wild to me.

But why the praise? Why such a gap in interpretation among the critics? The answer, I think, lies in Ed Smith’s excellent article on Resident Evil 4 Remake, “And Then There Are Things We Don't Remake”. In it, he observes that “commercial entertainment has gotten extremely good at ensuring that your beliefs, whatever they are, are somehow reflected back to you”, taking Ashley from Resident Evil 4 Remake as an example:

“If you’re a feminist, Ashley talks more, does more, is kind of semi appreciably less sexualised than before. It won’t work on everyone, but enough people will be impressed by this ostensible progress as compared to 2005 that Resident Evil 4 Remake more or less passes the look test. If you like things how they were, and you’re worried about how videogames increasingly seem politicised or driven by a liberal agenda, Ashley still doesn’t do that much, and you still get to order her around, and there’s a few decent close-ups of her and Ada.”

Put another way, female characters in modern, big-budget games are frequently written to appeal to all demographics, even conflicting ones. Progressives will latch onto the hints of nuance to the writing of a female character or her gameplay design, while anti-progressives are appeased because they see that nothing has changed in the overall scheme of things.

Tears of the Kingdom is good because all those flashbacks are focused on Zelda, and in them we see a capable, clever young woman make a very hard choice for the sake of her people. Tears of the Kingdom is bad because ultimately Zelda isn’t present for most of the game and needs to be saved by Link.

Alternatively: Tears of the Kingdom’s handling of Zelda isn’t great, but hey, did we really expect any better of Nintendo? The trouble is that the games most kaleidoscopic in their representation are likely the biggest names – and as Smith notes, “there’s only so much indignation you can have about this, because it’s obviously how it’s going to be, and always going to be—they’re always going to make games this way, the big games, because it’s an industry”.

His illustration of this defeatist mindset is spot-on, but I wish it wasn’t. It doesn’t need to be the case. Let’s keep looking to that horizon, rather than only sticking to familiar plains.

#tears of the kingdom#loz totk#totk spoilers#totk thoughts#games criticism#my writing#legend of zelda

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

something that's interesting about the culture war bullshit around the mario movie and movie critics (why is the world like this) is how much it mimics a constant narrative around games and how "games should just be fun"

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Lies of P // Been There, Done That

Early on in Lies of P, you cross this bridge to the city hall of Krat. It's dark and storming and most notably spotlights shine on a puppet strewn across it's steel beams. A sign is pinned to the body - "PURGE PUPPETS" . You're looking directly at this one specific spot above you to read that sign. It's a set piece fit for trailers. Much later in the game you fight your way up to a Cathedral on a mountaintop. Hours have passed. After completing the Cathedral you receive a side quest to come back down the mountain to this bridge and investigate the puppet hanging from the crossbeam again, but with one very specific difference.

The weather has cleared.

You look up to the puppet's sign and now see St. Frangelico Cathedral tower over the city of Krat. Clear in the morning Sun. This little treasure hunt pointed you towards recognizing the church looming over you. How'd you miss that? During the climb you looked down at the city so it makes sense you would have seen it. It's massive. It makes sense physically. You just didn't notice it.

St. Frangelico was still there in silhouette. Hotel Krat stands out on the skyline in the rain but Lie's of P's world designers chose to pull this punch until you had visited the Cathedral. The weather here, specifically here on this bridge, changes the focus of where you are guided to look at.

Lies of P demonstrates a complete understanding of this kind of world design without being a carbon copy of Dark Souls.

Venigni, an NPC in your home base, sets up shop next to his scale miniature models of the city. Little replicas of city hall, the tramway, the factory. You'll come back and visit his shop often over the course of the game. After you recruit him you begin your ascent up to the cathedral.

The Sun rises for the first time. You take a cable car up the mountain. It's a quiet moment. You look out at Krat in the sunrise. You look past the battlefield to see a city still mostly intact. The destroyed parts become too small to see. Like chips or imperfections in miniatures. Krat is now small, it's warm, it's serene. You can imagine the City surviving this.

You'll remember this quiet moment when you see the miniatures again.

#dark souls#lies of p#game design#fromsoftware#writing on games#gaming#souls like#world design#pinocchio#games criticism#videogame essay#dark academia#writing#neowiz#fromsoft#lop

65 notes

·

View notes

Text

Returning To The (Tumbling) Skies

Twitter’s exploding! That’s okay! Between this and my space at cohost, it looks like we’re gonna be back in action with light game crit and sharing my Skies of Arcadia novelization. How nice!

What’s that last part? Glad you asked, Hypothetical Tumblr user! Since 2020, I’ve been writing a full novelization of the fantastic (and for me life-changing) Dreamcast game Skies of Arcadia! You can read it here.

And I guess since it’s been a while since I posted here: if you’re catching this post and don’t know me: my name is Harper and I’m the community manager at Double Fine Productions we make games like Psychonauts 2 and Brütal Legend. I started writing here in 2015 or so, which led to a job as a journalist/games critic, and then to Double Fine.

(Gosh, I look at old posts here and it’s... a totally different me back then!)

I think I’ll be posting here more often. You can expect a migration of some of my cohost posts here in the next week or so. So hey: good to (re?) meet you.

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

Elden Ring: Anybody Home?

I wish Elden Ring had more people. Ordinary people, who aren’t soldiers or cultists or monsters or diseased or living jars stuffed full of the corpses of great warriors.

I’m always running into presumably human enemies and I can’t fathom what their deal is. What do they eat? Who do they work for? Who raised them and where are they?

There may or may not be some kind of answer to these questions buried deep within Elden Ring’s purposefully inscrutable lore, but for those of us who just play the actual game, 99% of the living things in this world exist only to stand in one spot until it’s their turn to try to kill you.

What’s There Is Great, But It’s Not Enough

Exceptions to this rule are generally memorable moments — arriving at Radahn’s castle to find Alexander and Blaidd waiting there, stumbling into the peaceful Jarburg, or any time you encounter a new non-hostile NPC.