#for you to have found family expectations it can repeatedly subvert.

Text

BnHA Chapter 301: All My Todorokis

Previously on BnHA: We learned that when a bunch of superpowered villains are suddenly set loose with nobody around to stop them, things get fucked pretty quickly. Old Man Samurai and a bunch of other useless people decided to make “I pretend I do not see it” their new mantra, and resigned. Endeavor had a moment of despair on account of being crushed by the guilt of having ruined the lives of himself, his family, and basically everyone else in the entire world. For various reasons the heretical notion of “person who has done bad things feels sorry for doing them” sent fandom spiraling into a meltdown, so that was fun. The chapter ended with the entire Todoroki clan descending upon Enji’s hospital room to have a dramatic chat about Touya and All That General Fuckery.

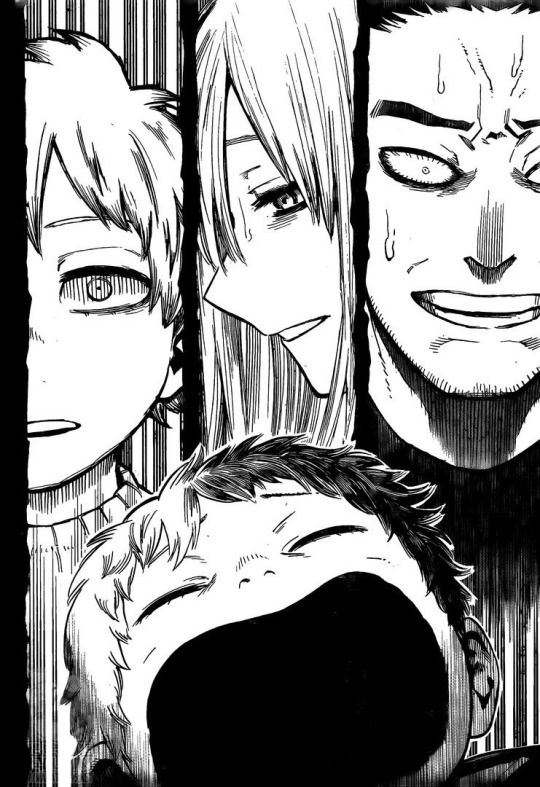

Today on BnHA: Horikoshi is all “here’s the story of how Baby Touya slowly went insane trying to win his father’s love.” It’s a tale full of subverted expectations and heartbreaking inevitability, and also like twenty panels of the cutest fucking kids who ever existed on planet earth, who are so fucking cute that I can’t stop thinking about their cuteness even with all of the horrifying family tragedy unfolding around them. It is absolutely ridiculous how cute they are. Touya is out here pushing his tiny body past its limits because he inherited the same obsession as his dad and neither of them can put it aside even though it’s destroying them, and yet all I can think about is Baby Shouto’s (。・o・。) face. Anyways what a chapter.

so I have to confess that even though I managed to avoid being caught off-guard by the early leaks, the number of people reblogging my Endeavor posts from earlier this week and using the tag “bnha 301” kind of gave me an inkling that this chapter will include more Tododrama lol. that said, I don’t know anything else about it, so we’re still good spoiler-wise

AHHHHH FLAHSBAKC AHHHH. omg I know I typoed the shit out of that, but I’m just going to leave it lol I think it’s fitting

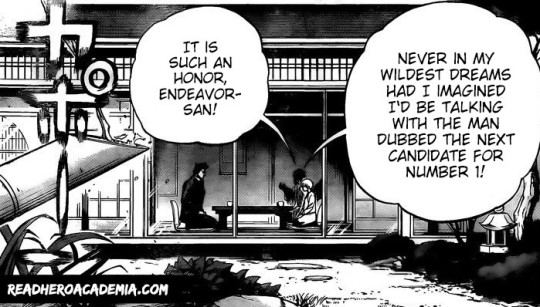

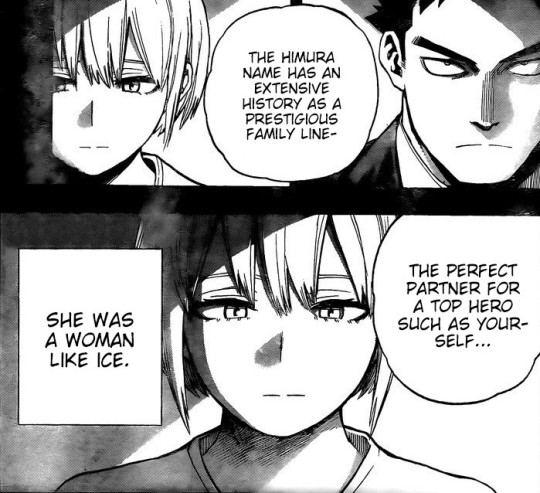

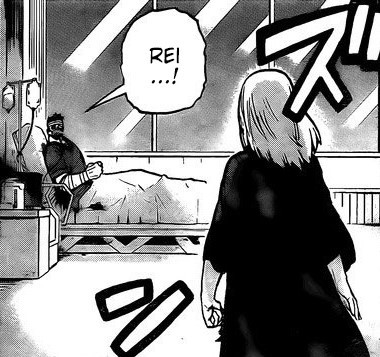

holy shit holy fuck. so this is Rei and Enji’s first meeting, then??

yepppp, oh shit

so wait, I know this is not even the slightest bit important, but are they meeting at Enji’s home or Rei’s? because I always figured that Enji was the one with the super-Japanese aesthetic, but maybe that was Rei’s side of the family all along

(ETA: from what I found during my very brief google search, omiai meetings are often held at fancy hotels or restaurants, so maybe that’s what this is.)

there’s such a period drama feel to this setting. like it’s so outrageously formal fff how can anyone stand this kind of atmosphere though seriously

OH THANK GOD

I mean they’re still stiff af but at least they’re not rigidly sitting in seiza and staring at each other unblinkingly anymore lol. Enji’s actually got his hands in his pockets now. why is this somehow almost cute

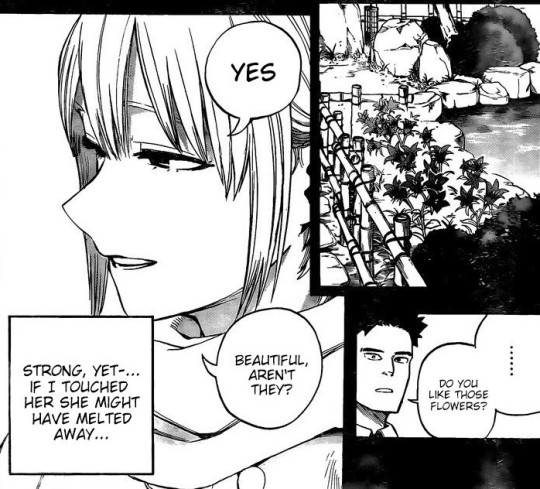

oh damn it’s the flowers

Rei seems so subdued and it’s so hard to get any idea of what she’s actually thinking. I want to see her side of this dammit

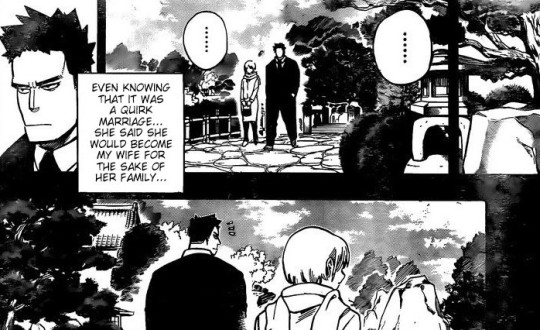

but anyway, so at least from Enji’s perspective it seems like even though the marriage was arranged and he picked her because of her quirk, he still loved his wife and wanted to do right by her. the fact that he was watching her and noticed that she liked the flowers, and remembered that detail for all these years -- there’s a reason why Horikoshi’s showing us this. we know what’s going to happen later on; we know how much fear and violence and breaking of trust is coming up ahead, and while it may seem like this scene is serving to soften Enji’s character further -- which to be fair it is -- it also helps drive home the full impact of his abuse. that it’s so terrible not only because of the trauma of the abuse itself, but also because of the way it retroactively destroys all of the good things as well. this could have potentially been such a sweet scene, but it’s inescapably tainted by the knowledge of what’s to come, at least for me. and that’s just brutal

anyways, shit. is the whole chapter going to be like this?? feel free to toss in something I can actually make a joke about sometime, Horikoshi

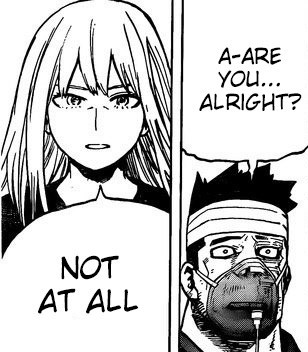

oop, back to the present

omfg lol

“are you all right” “NO I’M NOT ALL RIGHT WHAT THE FUCK.” “oh, right, because of all the stuff that’s happened with me abusing you and you having a mental breakdown and being hospitalized for ten years and then our son coming back to life and killing thirty people, right, right. I almost forgot.” whoops

omfg you guys I’m loving this new and improved steely-eyed Rei. I’m loving her a lot

and what do you mean “part one” fkjds how long is this going to be. TOO MUCH DRAMA FOR ONE CHAPTER TO HANDLE

oh, hello

yeah I’ll say you did. didn’t seem to bother you much at the time, though

HMMMMMMMMMMMM

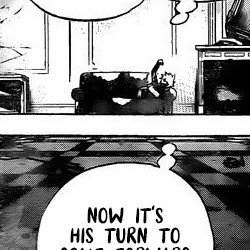

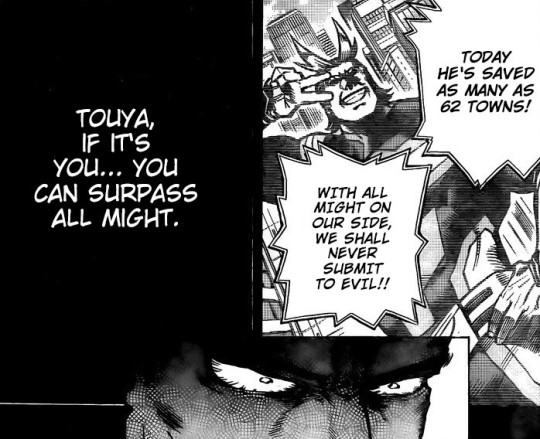

Dabi Is A Noumu intensifies even further. anyways though would you fucking look at this boy lounging on this moth-eaten couch doing his best DRAW ME LIKE YOUR FRENCH GIRLS impression wtf

Dabi what if you actually had killed him??? what would you feel?? satisfaction?? regret?? anything at all?? tell me your secrets goddammit

who are you talking to buddy

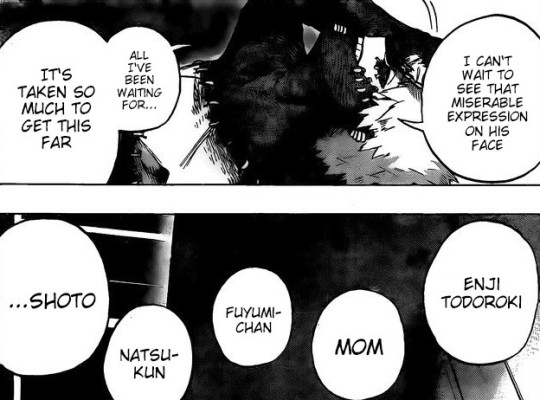

Fuyumi-chan, Natsu-kun (is it common for brothers to address each other as -kun?? can’t recall seeing that in many other anime, but hey), and “dot dot dot,,,,,, SHOUTO” lol thank you so much for this bountiful heaping of Tododrama Horikoshi we are blessed

AH, WHAT DID I SAY THE OTHER DAY

ULTIMATE MELODRAMATIC THEATER CHILD. “I’M JUST GOING TO LIE ON THIS COUCH SHIRTLESS AND ALONE AND MAKE SPEECHES TO MY FAMILY MEMBERS WHO AREN’T THERE AND SAY THINGS LIKE ‘WATCH ME IN THE PITS OF HELL’ WITH A STRAIGHT FACE BECAUSE NO ONE’S THERE TO JUDGE ME.” WELL JOKE’S ON YOU MISTER CHATTERBOX BECAUSE I AM IN FACT JUDGING THE SHIT OUT OF YOU LOL

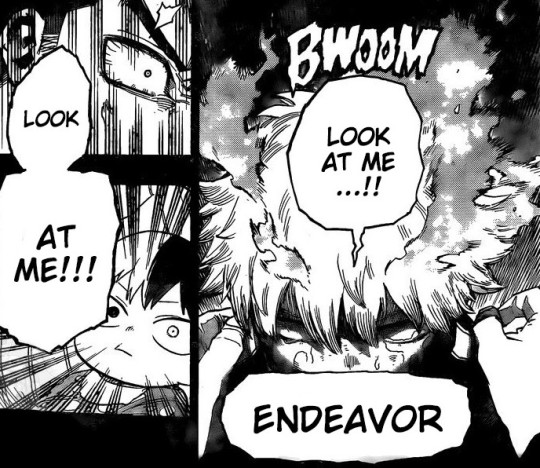

(ETA: and on a more serious note, it’s interesting to see that “look at me”/”watch me” theme being used again though, because we see that same sentiment uttered repeatedly by the younger Touya in the flashback. well kid, you definitely got your wish at last. don’t know what else to say.)

OKAY HORIKOSHI HAS DECIDED THAT’S ENOUGH FUN, TIME FOR MORE FLASHBACKS

oh my sweet precious lord

just as cute as we left him. giving us a child this cute when we all know full well what’s going to happen to him is just unspeakably cruel though

HOMG

I’m fucking speechless. you broke me, congratulations. what am I even supposed to do with this

I can’t get over this. moving forward my life will be split into two distinct parts, B.P. (Before the Pout) and A.P. (After the Pout)

and meanwhile there’s ALL THIS BACKGROUND ANGST BUILDING UP, AND I CAN’T EVEN FOCUS ON IT. Touya’s arm and cheek are covered in bandages (I’m guessing this is shortly after that “ouch!” panel we got some chapters back), and Enji is deliberately avoiding training with him because he doesn’t want him to hurt himself further. I can’t fucking get over the irony that all this time everyone thought Touya had died because Enji pushed him too far in his training, and it turns out that it’s the opposite -- the tragedy ultimately happened because he didn’t want to push him. but I’m jumping ahead of myself though I guess

by the way,

remember this?? just wanted to remind you that it exists just in case you forgot

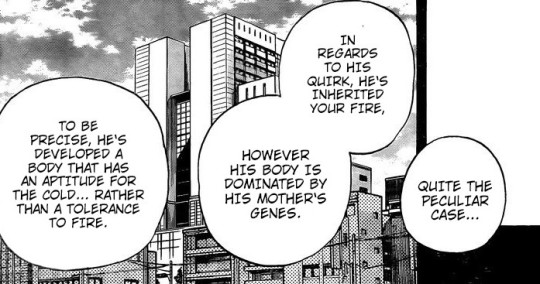

so now someone is talking and basically saying that Touya is the exact opposite of what Enji was hoping for when he decided to start playing with quirk genetics

-- okay hold up

...lol no, never mind. for a second I thought “holy shit he looks kind of familiar WHAT IF IT’S UJIKO OMG” before I remembered that Enji would have recognized him during the hospital capture mission if that was the case. so NEVER MIND, PROCEED

IMAGINE THAT, ENJI DOESN’T QUITE SEEM SATISFIED WITH THIS SUGGESTION OF QUITTING NOW

(ETA: how the fuck did this man go around saving 62 towns in a single day what even is All Might.)

[clicks tongue several times] trouble a’brewin’

MEANWHILE BABY TOUYA HAS UNFORTUNATELY INHERITED HIS DAD’S STUBBORN STREAK

KLDIHWOEIJFL:KSDJ

!!!!!!!!!!!

oh my god. oh my god. what is this chapter. WHAT IS IT

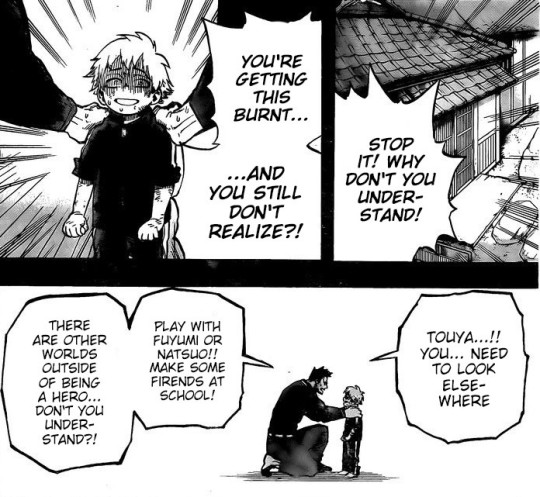

so now Touya is all “YOU JUST DON’T UNDERSTAND MY MANLY DESIRE TO BURN MYSELF ALIVE” well you got her there champ

THEY’RE TOO CUTE. OH MY GOD. HIS FURIOUS LITTLE TEARS. HER CHUBBY LIL FACE. HIS STUBBY LIL FISTS. SOMEONE HELP ME

also are they just home alone lol or what. “hey Touya, you’re what, like six now?? do us a favor and look after your baby sister for a couple hours for us would you? make sure not to set yourself on fire or anything.” WHAT COULD POSSIBLY GO WRONG!!

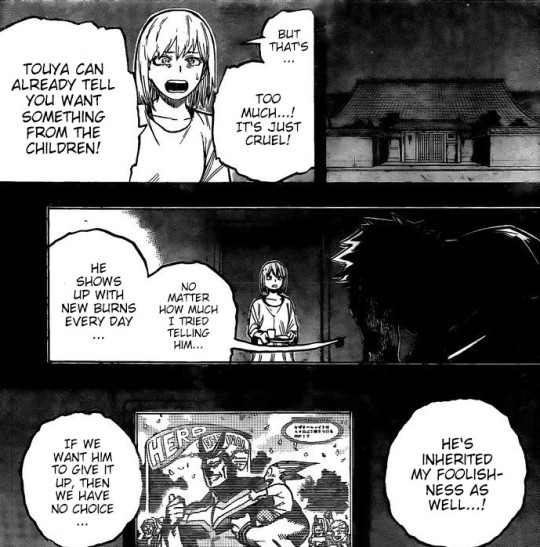

now it’s nighttime and Enji and Rei are arguing, presumably about his decision not to train Touya anymore

whew. okay. so, a couple of things here

1. first of all I think this conclusively shows that Enji really was trying to do the best he could for Touya. he stopped training him as soon as he realized it was hurting him, but Touya was still determined so he tried to make it work anyway, and even visited doctors to try and figure out if there was anything they could do. then, once they were absolutely sure that it wasn’t going to work, he tried multiple times to explain to Touya why they had to stop. he didn’t just abandon him out of the blue, which is really important to note. “no matter how much I tried telling him...”

so yeah, that debunks another common fandom accusation. so by the time he finally makes this decision, which we all know is going to turn out horribly, it’s basically because he’s already tried everything else he could think of. which, by the way, still doesn’t mean he handled this right. but at the very least he was taking Touya’s feelings into account and he was trying, and he didn’t just abruptly toss his son aside (at least not yet)

2. buuuut, then there’s this panel right below all that

which is the other side of it. if he’d just quit like the doctor person advised him to, that would have been the end of it. Touya would still have been upset, but he would have eventually gotten over it and the family would have moved on and possibly even been happy. but what happens next happens because Enji can’t let go. he still has this maddening urge to surpass All Might, and so he and Rei keep having more children, and then Shouto is born, and Enji finally has a kid he can start projecting all of his hysterical ambitions onto once again, and everything starts spiraling out of control soon after

though p.s. none of that is Shouto’s fault though!! he’s one of the few good things to come out of this whole mess and I’m very happy that he exists. the tragedy is that his dad fucking lost his mind over his quirk and fucked everything up. but that’s on him, not Touya or Shouto

anyways, SLKFJLSHGLKJL

I CAN’T FUCKING TAKE THIS YOU GUYS??? LOOK AT THAT LIL BUTTON OF A NOSE??? I’M LOSING IT HERE???

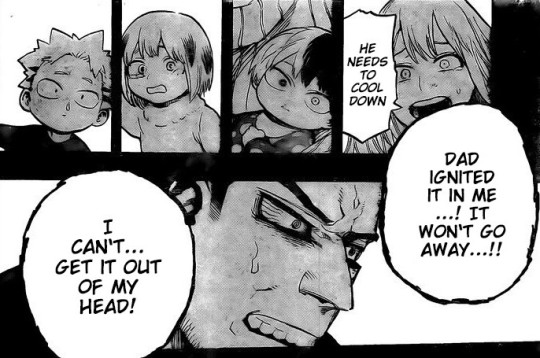

AND TOUYA JUST SEEMS DEVASTATED OMG

because children aren’t stupid, after all. he understands that his dad is still looking to surpass All Might. and so he feels like a failure, and feels like his dad is trying to replace him because he wasn’t good enough. and even now, isn’t that what the adult Touya is trying to prove?? that he was good enough after all?? “I’ll show you what happens when you give up on me, dad”?? “I’ll show you what I can do”?? fuck my life fuck everything

AND YOU CAN SEE THE TOLL THAT IT’S ALL TAKING ON REI GETTING WORSE AND WORSE AS WELL OH GOD

really nice touch here with the panel outlines becoming all shimmery from the heat of Endeavor’s flames (and/or becoming more unstable as the family gets closer and closer to their breaking point). but man, Horikoshi I can’t handle this, please show us more cute kids or something I can’t

GKELKWFJLDKSHFLKL

WITTLE BABE. BEEB. BUBS. SMOL. lkj; oh ouch a piece of my heart just detached and latched onto him huh look at that

TODOROKI “I’M SO SMALL AND I HAVE NO IDEA WHAT’S GOING ON AND I DIDN’T ASK TO BE HERE” SHOUTO AHHHHH

crazy how they all just seem to know right off the bat lol. kid doesn’t even have object permanence yet, let alone a quirk. but do they care?? IT’S THE HAIR, RIGHT. WE’RE ALL THINKING IT, I’M JUST GONNA COME OUT AND SAY IT. they knew the minute they looked at him lol

AND MEANWHILE TOUYA IS OFF HAVING UNSUPERVISED TRAINING/CRYING SESSIONS IN THE MOUNTAINS OR WHATEVER, AND, UH OH

are those blue flames yet?? they seem pretty close

(ETA: this is one of the few cases where the manga being in black and white is infuriating lol.)

OH MY GOD AND STILL

so it’s not like he was so disinterested that he didn’t notice what was happening, and he was still trying to stop it and get through to him. trying to reassure him that it wasn’t the end of the world and there were other things he could do with his life, but this one particular thing just wasn’t going to happen

fucking hell. it’s agonizing seeing how close they actually were to fixing it. if he’d only said the right words, or if he’d realized at this point how destructive his obsession could be to his kids, and backed off from putting that same pressure on Shouto. we came so close to possibly having a happy ending

AND ALSO THIS HAS NOTHING TO DO WITH ANYTHING BUT PLEASE LOOK AT HOW TOUYA IS LIKE THREE AND A HALF FEET TALL AND HIS DAD IS LIKE NINE AND A HALF FEET. Touya barely comes past his knees flkjlkg. the Todoroki household must have been so filled with like plastic stepstools to reach the bathroom sink and all the little baby toothbrushes, and baby gates to keep the kiddos out of the important grown-up rooms and stuff. and also days-old half-empty cups of water and stale crackers and hot wheels and my little ponies strewn everywhere

“BUT EVERYONE AT SCHOOL SAYS THEY’RE GONNA BE HEROES” a wild Deku parallel appears?? how bout that

I know this is like a pivotal moment in the Todo Tragedy and all, but fucking look at this lil dumpling

“sup bro, it’s me, the manifestation of your fears of inadequacy and lack of fatherly affections. a GAAA. ba-baAA-baa [gurgling baby sounds]”

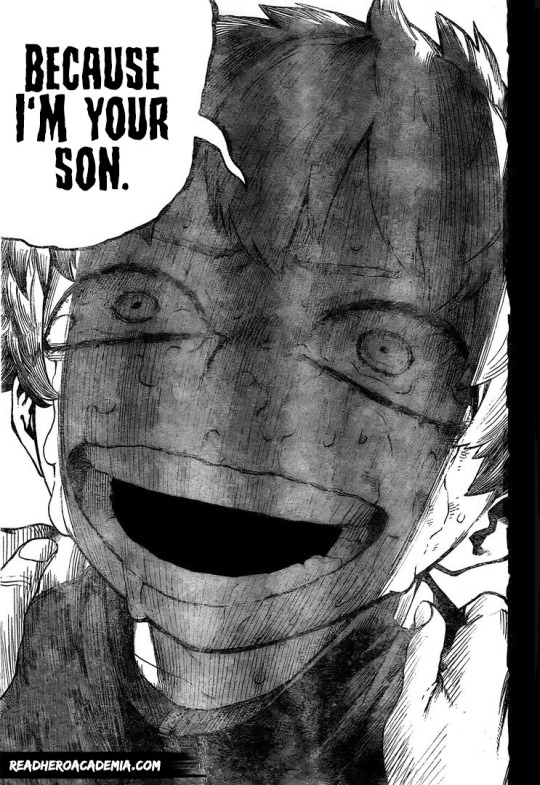

OHHHHH IT’S THE SOUND OF MY HEART BREAKING OH NO

HE WANTS TO BE LIKE YOU ENJI. good lord somebody please just get this family some therapy

“DAD YOU IGNITED IT IN ME” flkjslkj nope, nope. not ready for this pain here

baby Shouto, would you like to weigh in on this affair? “DA!! ba-ga-daaa, [pacifier chewing noises]” oh my, you don’t say. so insightful for one so young

OH MY GODDDDDD

IT’S SO DRAMATIC BUT ALL I CAN THINK ABOUT ARE THE SHOUNEN WOOSH LINES SURROUNDING FOUR-MONTH-OLD SHOUTO LOL HE WAS LIKE THIS FROM BIRTH OH MY GOD I AM DYING HELP

SHOUTO YOU’RE RUINING THIS ENTIRE CHAPTER!?!?!

“yo, the fuck kind of family was I fucking born into” oh, son. if you only knew. IF YOU ONLY KNEW!!

(ETA: lmao I got so distracted by the ridiculous cuteness that I glossed over the fact that Baby Touya seems to possibly be aiming at him?? it’s hard to tell because he’s also super out of it from heatstroke and may just be losing control in his attempt to show off his upgrade.)

ANYWAY THAT’S THE END EXCEPT WHAT’S THIS LAST LINE OMG

ffffff. and we’re in for ANOTHER chapter of this next week?? MORE drama?? MORE BABIES?? MORE OF EIGHT-YEAR-OLD TOUYA’S SLOW DESCENT INTO MADNESS. MY HEART CAN’T TAKE IT, BUT ALSO YES PLEASE SIGN ME UP

#bnha 301#dabi#todoroki touya#endeavor#todoroki enji#todoroki rei#todoroki shouto#todoroki fuyumi#todoroki natsuo#bnha#boku no hero academia#bnha spoilers#mha spoilers#bnha manga spoilers#makeste reads bnha

395 notes

·

View notes

Text

Tangled Salt Marathon - “Rapunzel Knows Best!” ( A first half of S3 Recap)

So I decided to place the recap after Be Very Afraid for several reasons. For starters it’s where the season three hiatus took place. It’s also framed like a cliffhanger episode the same as The Great Tree and Queen for a Day; so while Cassandra’s Revenge is technically the midseason finale, Be Very Afraid functionally servers this narrative purpose better. Finally I want to keep the Cassandra heavy stuff contained in it’s own recap later same as I did for Varian’s arc in season one.

Also keep in mind, everything I discussed in previous recaps still apply here. Nothings changed and you could argue that the issues I bring up now could have also apply to past seasons; they just happen to be at their worst here.

Here are the past recaps

To Filler or Not to Filler

Hey, What Ever Happened to That Varitas, Guy?

What Is the Point?

‘Whatta Twist’

And here are the episodes that’s covered in this recap

Rapunzel’s Return Part 1

Rapunzel’s Return Part 2

Return of the King

Who’s Afraid of the Big Bad Wolf

The Lost Treasure of Herz Der Sonne

No Time Like the Past

Beginnings

The King and Queen of Hearts

Day of the Animals

Be Very Afraid

Poorly Defined Conflicts

I’m not just talking about Cassandra’s lack of goals here either, though that is a part of it. I mean in several episodes the central conflict isn’t laid out clearly enough before being resolved. We flip from one set up to the next without ever resolving the first; like in Rapunzel’s Return when Cass and Varian fight for screen time or whenever Rapunzel is suppose to learn one lesson only for someone else to learn a completely different lesson in every other episode. And to this day I don’t know what Rapunzel and Feldspar’s subplot in Lost Treasure was suppose to be about.

There’s also of course the ill-defined overall conflict; which at this point has become convoluted and nonsensical to the extreme, and will only grow more aggravatingly stupid as the season progresses. The main villains lack clear goals, their motivations don’t align with previously stated facts, and the actual interesting conflict involving the threat of the rocks and their destruction of people’s lives and homes is just shoved under the rug and forgotten about.

There is no story without conflict. Having the conflict be all over the place is not only confusing but makes it harder for the audience to invest in what’s going on.

Failed Narrative Promises

Tying in with the above statement regarding conflicts, we have failed narrative promises. Rapunzel is repeatedly told to that she needs to learn something in several episodes only for her not to learn it at all. She either learns some unrelated ‘lesson’ that wasn’t established, (like in Rapunzel’s Return with her pervious goal about ‘opening up to others’ being switched out for a generic ‘responsibility’ lesson that at the last minute, where she doesn’t even do anything responsible,) or she winds up ‘teaching’ the opposite lesson to a different character thereby rewarding her for her bad behavior.

And that’s just within the induvial episodes themselves; there’s also broken narrative promises through out the overall story arc; like...

no justice/redemption for Lady Caine,

no acknowledgment that the Saporians are the victims of colonization

no conclusion regarding Corona’s murky past

no satisfying ending to Varian’s plot that sees everyone in involve grow

a poor copout of an explanation for Cassandra’s face/heel turn

The Dark Prince reveal going nowhere

The Brotherhood being put on a bus

King Frederic, or any royal, not being held accountable for their past actions

Lance’s new found responsibilities just being thrown away for the tenth time

The Disciples plot being being dropped

next to nothing in season two winds up being relevant

And Rapunzel, the protagonist of a coming of age story, fails to learn anything at all

I could probably go on but you get the gist. Tangled is incredibly frustrating show to watch because doesn’t deliver what it promises. You’re not being clever by ‘subverting audiences expectations’ unless you can justify your narrative decisions with previous set up. Tangled is too lazy to build proper set ups so it’s ‘twists’ leave you wanting to punch things rather then impressing you.

Character Assassinations

Every single character in Tangled the Series gets thrown under a bus, driven off a cliff, and then allowed to drown in the ocean of their completely unaware self-congratulatory smugness.

Rapunzel is turned into a bully

Cassandra is given the idiot ball to hold permanently

The King and Queen are lobotomized

Quinin gets replaced by a robot

The rest of the Brotherhood are pale shadows of what they could have been

Edmund is transformed from tragic complex figure into a dumb jerkoff who abuses his kid for a laugh

Zhan Tiri, once an ancient demon warlock, is reduced to a floating impotent ghost girl

The Saporians become poor hipster parodies

Cap is put on a bus

Any villain who isn’t Cass is gets ignored

Lance is infantilized to the point of absurdity

Eugene becomes a doormat

and poor Varian is forced to become a complacent victim to his abusers as oppose to being allowed to keeping his dignity

I think the only person who escapes this mass murder of characterization is freaking Calliope, and she’s hasn’t even appeared yet! (Well okay her and Trevor, maybe)

This all ties back into the poorly defined conflict and failed narrative promises. Rather than let the characters drive the story, they’ve become puppets to the plot, and plot is really stupid and forced, and circles back in on itself and is full of contradictions.

Manipulating the Audience’s Empathy to Do the Work for the Writers

The reason why the creators believe they can get away with such poor characterization and lazy writing is because they expect the audience to do all the heavy lifting for them.

Cass isn’t given an on screen reason for what she does because they’re hoping her fans will just automatically excuse her because they like her/relate to her and not, you know, get mad at the writers for dumbing her down. And after all who doesn’t love the creator’s pet? Meanies! That’s who!

No one calls out Rapunzel’s bullshit on screen, because if everyone likes her, then you, viewing audience, should too. Because if you have any sort of independent critical thinking abilities and a sense of right and wrong then clearly you’re ‘just a hater’.

Everyone should just shut up and be satisfied that Varian is even on screen now and be grateful for the scraps that they get cause he’s not the real point of the show and according to Chris ‘Varian fans aren’t real fans’. Even though they make up most of his viewing audience.

I could go on, but it’s just variations of the above. The writing in this series is very fond of gaslighting the audience and trying to trick them into justifying the absolute worst behaviors while desperately hoping they doesn’t noticed the continued downgrading and dismissal of characters they do like or once liked.

And the sad thing is, it’s worked. There are people to this day that still try to justify this show’s shitty morals and bend over backwards to excuse the likes of Rapunzel, Frederic, Cassandra, and Edmund. Worst, there are loud sections of the fandom, (usually on twitter) who think bullying is okay and follow in Chris and his characters footsteps. Most of them young impressionable girls who are now ripe for TREFS to indoctrinate because they use the same bullying tactics and excuses for authoritarianism.

Media does effect reality, but not in the way purists and antis would have you believe. No one is going to become a violent manic from playing a video game nor a sex offender because they read a smut fic. But they very much will conform to toxic beliefs if it’s repeated enough at them by authorities they ‘trust’; like say the world wide leading company known for family entertainment and children’s media, and the ‘friends’ they find within the fandom for said company...

I’m not saying you can’t enjoy Tangled the series or that you’re some how wrong for liking it’s characters, nor do you have to engage with every or any criticism thrown it’s way. But yes you need to think about the media you consume on some level and valid criticism is very much important to the fandom experience for precisely the above reasons.

Conclusion

This isn’t even the tip of the iceberg of what’s wrong with this show, but it is most of its biggest problems laid bare. Anything that haven’t covered here or in the past recaps will be explored in the final recap. Cause this is it folks; the last leg of the journey for this retrospective. When come back, hopefully next week, we’ll tackle Pascal’s Dragon.

94 notes

·

View notes

Text

Some thoughts about The Magicians S4 finale

I want to write a bit (recreational activity for me) and I have thoughts about The Magicians, especially about what went down in S4, so there we go. It will probably turn out long and rambly, so buckle up. But first, a few disclaimers.

X

As I will discuss The Magicians plotlines & the writers' creative choices there will be spoilers. If you haven't seen S1-S4 and you don't want to be spoiled, don't read past this point.

X

I won't be discussing the writers actions after the finale, neither the silence nor the interviews. It's garbage fire and I don't have time for this. (It's rather baffling that in this day and age tv business professionals still handle the communication with the fanbase this badly.)

X

Now, I would not call myself a fan of The Magicians, but I got engaged in the story. I'm a fan of very few shows these days and usually I steer clear from the fandoms' open waters. I don't have the time or the energy, so I stick to the friends I've made back in the day.

As such, I haven't watched The Magicians until after the S4 finale. Recently I've been thinking about the treatment of the queer characters in the ongoing tv shows, so the Q's death controversy was right up my alley. I also had some time for a binge and some personal issues to be distracted from (no worries, I'm dealing with them, I just couldn't allow them to cause me obsessing over them).

X

I've tried to read Grossman's books when they first came out and I decided they weren't for me. I still think that. If you want some quality fantasy recs, hit me up.

When the show first came out I watched first few eps and then noped out of it. I thought it was pretty bad and full of issues and, and upon rewatch, that's still my opinion about the first half of the 1st season.

X

The show does get better. It's ocasionally great (S3 is pretty strong and thoroughly enjoyable – with eps 3.04 & 3.05 being really really good, the first one for its storytelling quality, the second one for its emotional payoff). However it has various issues throughout that would have made me mistrustful of the writers, even if I didn't know what happens to Q.

X

So, you may say I went in prepared and with my reservations. As a consequence I didn't really have the feeling of rage and betrayal that the long time fans did. But I get them and they are so valid. Take care of yourselves, take care of each other, take your time to process the grief in a way that works for you. And stay hydrated.

Now, processing what happened might include some action and engagement. I've seen fanfic writing, article writing, venting on different platforms, sharing the experiences of your lives and loves and mental health, #PeopleLikeMe campaign, Change petition, decisions to stop watching the show and fundrasing for the Trevor Project. Things big and small, heartbreaking and inspriring. The only thing we shouldn't do is harass the writers (and thankfully I've seen very little of that), because harassment is never ok. And we are better than that.

Creators can fuck up (and I will defend their right to fuck up, we're all only human) and we can call them out. Maybe they will learn from their mistakes, maybe not (and if not, well, fans will move on to the greener pastures, where we will get better and kinder stories), but maybe someone else will, someone who is or might become a creator themselves. And maybe there's a little consolation in that.

(And this is why we shouldn't stay silent.)

X

Thinking about it, I see two explanations for killing Q:

the writers did it for shock value, knowing it will get them some buzz (and they miscalculated how much and what kind of buzz)

the writers really don't understand their own show and characters

I believe it may be both.

Even in the first season, when Q introduces us to the world of the show as he himself gets introduced to it, I'd still say The Magicians are an ensemble show. And the show deals with Q being the „white male lead” in the S1 finale when Q gives Alice the knife (and has a speech dealig with that directly, the show does this kind of thing repeteadly, characters monologuing or explaining trope/plot to another character, it's terrible writing, but it's explicit, you can't say the show didn't say something) and uses the fact that the Beast sees him as the „hero” against it, providing distraction for Alice to act. And the show reinforces the notion of Q not being the main hero of the story repeatedly throughout the series and in various ways (Julia being the variable to make loop 40 successful, Eliot becoming High King and so on and so forth).

So when we arrive to S4 Q is:

one of a diverse group of pretty fucked up but still lovable friends (effectively a millenial found family)

average magician

dealing with his mental issues that didn't go away when he discovered magic/Fillory

canon bisexual

caring and loyal and nerdy and awkward

(Gee, how come so many people identified strongly with that.)

(Sorry for the snark.)

No one holds against Q that he isn't some kind of Chosen One, because it was never what his friends expected from him or valued him for. He sometimes/low-key expected it from himself, but the show dealt with that. Repeteadly. And that was fine and that was subverting tropes.

So when the writers first sideline him and then have him killed in S4 finale (in a pretty straightforward Heroic Sacrifice scene), they don't kill a straight white male hero wearing the plot armor, they kill a vulnerable young queer man with mental health issues. And guess how many of them we have on our screens.

What makes the matter even worse:

they handled Q's history of suicidal thoughts/tendencies horribly

it turns out that what looked like a clear setup for future romantic relationship between Q and Eliot was in fact a setup for Eliot's grief story (Right up the Bury Your Gays alley as if that's still the only story a gay man can get on tv. In 2019.)

X

I do belive you still can write a valuable and respectful story of a queer person comitting suicide and their family, friends and community being left to deal with the aftermath, but you'd need to put into it a lot more work, time, thought, talent and sensivity than The Magicians writers did or even are (in my opinion) capable of.

X

For all of the tropes subverting, sometimes very entertaining, The Magicians still were an escapist story at heart. And I really can't think of anything worthwhile the writers archieved by pulling the rug from under its fans.

X

Other issues with S4 finale that I might write about sometime in the future (but now maybe I’ll go and rewatch some Black Sails, Doom Patrol or Killing Eve):

treatment of Julia and Penny 23

treatment of Kady

treatment of the Monster (really)

treatment of Margo and Josh

resolution of the two main storylines (The Library & the Monsters)

#the magicians#the magicians finale#the magicians syfy#the magicians spoilers#the magicians s4#tw: death#tw: suicide#quentin coldwater#eliot waugh#tw: mental health

62 notes

·

View notes

Link

...There are two related, yet distinct, kinds of anti-Semitism that have snuck into mainstream politics. One is associated with the left and twists legitimate criticisms of Israel into anti-Semitic conspiracy theories. On the mainstream right, meanwhile, political leaders and media figures blame a cabal of wealthy Jews for mass immigration and left-wing cultural politics in classic anti-Semitic fashion.

[Rep. Ilhan Omar’s (D-MN)] tweet was a pretty clear example of the first kind of anti-Semitism. Plenty of Jews who are critical of the Israeli government, including me, found her comments offensive...

But it’s also clear that a lot of Omar’s critics don’t have much of a leg to stand on. Conservatives have been trying to label Omar an anti-Semite since she was elected in November, on the basis of fairly flimsy evidence. (...) Trump once told a room full of Jewish Republicans that “you’re not going to support me because I don’t want your money,” adding that “you want to control your politicians, that’s fine.”

The fact that Omar apologized under pressure, and that Trump and McCarthy have never faced real consequences for their use of anti-Semitic tropes, tells you everything you need know about the politics of anti-Semitism in modern America.

...There are two core truths about this incident. First, Omar’s statement was unacceptable. Second, Republicans going after her — including the president — should spend less time on Democrats and more time dealing with the far worse anti-Semitism problem on the right.

...In the day and a half since Omar’s initial comments, a number of left-wing writers have emerged to defend her. They argue that Omar was attempting to point out the financial clout of the pro-Israel lobby — the American Israel Public Affairs Committee, or AIPAC — and not to make generalizations about Jews. The pushback against Omar, they say, is part of a broader campaign to smear a young Muslim congresswoman and silence criticism of Israel.

...It’s true that in some cases, all criticism of Israel or AIPAC, even if it’s legitimate, is labeled anti-Semitic — and that’s a real problem. Omar’s faith has made her a particular target, and it’s fair to want to defend her against these smears in the abstract.

But the specifics of Omar’s tweet make things quite different. In the original context — where she was quote-tweeting [Glenn Greenwald]— she says that US lawmakers’ support for Israel is “all” about money. Yes, it’s a Puff Daddy reference, but she’s a member of Congress and maybe should be a little more careful about the implications of what she says...

There are two problems here: First, the tweet isn’t true. The US-Israel alliance has deeper and more fundamental roots than just cash, including the legacy of Cold War geopolitics, evangelical theology, and shared strategic interests in counterterrorism. Lobbying certainly plays a role, but to say that “US political leaders” defending Israel is “all” about money is to radically misstate how America’s Israel politics work (and discount the findings of the scholars who study it).

Second, and more important, totalizing statements like this play into the most troubling anti-Semitic stereotypes. The Protocols of the Elders of Zion, an infamous early-20th-century Russian forgery, describes a plot by Jewish moneyed interests to subvert and destroy Christian societies through their finances. This in turn draws on longstanding European anti-Semitic traditions that portray Jews as greedy and conniving.

After World War II and the creation of the state of Israel, the conspiracy theory shifted. Anti-Semites started using “Zionist” or “Zio” as a stand-in for “Jewish,” using Jewish activism in favor of the Jewish state as proof that they were right all along about the Jewish conspiracy. David Duke, the former Louisiana state representative and Ku Klux Klan grand wizard, released a YouTube video in 2014 that bills itself as an “illustrated” update of the Protocols. The video features footage of leading Democratic and Republican politicians speaking to pro-Israel groups, with the caption “both are in the grips of Zio money, Zio media, and Zio bankers.”

...Omar is, of course, not coming from the same hateful place as Duke is. But by using too-similar language, she unintentionally provides mainstream cover for these conspiracy theories. After her comments, Duke repeatedly defended her, even tweeting a meme that said “it took a Muslim congresswoman to actually stand up & tell the truth that we ALL know” (he rescinded the praise after her apology).

This is not to equate Duke and Omar — which, to be clear, would be absurd — but rather to point out how if you’re not careful when talking about pro-Israel lobbying, you can provide ammunition to some awful people. By saying that US support for Israel is “all” about money, Omar was essentially mainstreaming ideas that have their roots in anti-Semitism, helping make them more acceptable to voice on the left.

...There’s a real dilemma here. Pro-Palestinian activists, writers, and politicians have every right to point out what they see as the pernicious influence of groups like AIPAC. The group is undeniably powerful, and it’s worth mentioning in our conversations about both Israel policy and money in politics. You can and should be able to say, “AIPAC’s lobbying pushes America’s Israel policy in a hawkish pro-Israel direction,” without saying that it is literally only about dollars from (disproportionately) Jewish donors.

At the same time side, there is a special need on the left — where most pro-Palestinian sentiment resides — to be careful about just how you discuss those things. It’s not just a matter of providing ammunition to the David Dukes of the world; it’s about the moral corruption of the left and pro-Palestinian movement. If references to the baleful influence of Jews on Israel policy become too flip, too easy, things can go really wrong.

...When left-wing insurgent Jeremy Corbyn won the center-left Labour Party’s leadership [in Britain] in 2015, the people who inhabited these spaces seized control of the party power centers.

Corbyn, who had once referred to members of Hamas and Hezbollah as his “friends,” opened the floodgates for the language of Labour’s left flank to go mainstream. The result is a three-year roiling scandal surrounding anti-Semitism inside the party.

Dozens of Labour elected officials, candidates, and party members have been caught giving voice to anti-Semitic comments. One Labour official called Hitler “the greatest man in history,” and added that “it’s disgusting how much power the Jews have in the US.” Another Labour candidate for office said “it’s the super rich families of the Zionist lobby that control the world.” The party has received 673 complaints about anti-Semitism in its ranks in the last 10 months alone, an average of over two complaints per day.

...This is why Omar’s tweet was so troubling, and why the pushback from leadership really was merited. If the line isn’t drawn somewhere, the results for Jews — who still remain a tiny, vulnerable minority — can be devastating.

...The way Omar handled the controversy is interesting. Her apology was certainly given under immense pressure, but it reads (at least to me) as quite sincere[, and] this kind of sincere willingness to reconsider past comments is characteristic of Omar. She had previously gotten flak for a tweet about Israel “hypnotizing” the world, and recently gave a lengthy and thoughtful apology for the connection to anti-Semitic tropes during an appearance on The Daily Show.

“I had to take a deep breath and understand where people were coming from and what point they were trying to make, which is what I expect people to do when I’m talking to them, right, about things that impact me or offend me,” she told host Trevor Noah.

This is not the kind of behavior you see from deeply committed anti-Semites. Yair Rosenberg, a journalist at the Jewish magazine Tablet who frequently writes about anti-Semitism, argued on Monday that Omar has earned the benefit of the doubt:

“I’ve covered anti-Semitism for years on multiple continents, and this level of self-reflection among those who have expressed anti-Semitism is increasingly rare. Not only did Omar apologize for the specific sentiment, but she put herself in the shoes of her Jewish interlocutors and realized that she ought to extend to them the same sensitivity to anti-Semitism as she would want others to extend to racism.”

...This is what it looks like when the system works. A member of Congress says something offensive, most of her party explains why it’s wrong, and then she issues a sincere apology and demonstrates an interest in changing. That is a healthy party dealing with bad behavior in a healthy way.

This is not what you see on the Republican side when it comes to most forms of bigotry — up to and including anti-Semitism.

...Last summer, McCarthy sent a tweet accusing three Democratic billionaires of Jewish descent — George Soros, Tom Steyer, and Michael Bloomberg — of trying to buy the midterm election...

...Around the same time, President Trump claimed that protesters against Brett Kavanaugh were being paid by Soros...

And Florida Rep. Matt Gaetz suggested Soros was behind the so-called “migrant caravan” coming to the US through Mexico, a theory spread when Trump tweeted the video in Gaetz’s original tweet...

This all follows years of Soros demonization in the conservative press, with everyone from conspiracy theorist Alex Jones to Fox News anchors blaming the Jewish billionaire for various ills in the United States.

The defense of these lines is the same as the left-wing defense of Omar: It’s not anti-Semitic to simply state facts. But many of these “facts,” like Soros masterminding immigrant caravans, are false. Moreover, creating a narrative in which Soros and other left-wing Jews are puppet masters, using their money to undermine America from within, they are engaging in the same normalization of Protocols-style anti-Semitic tropes as Omar.

What’s more, they’ve done it with virtually no official pushback. The GOP has not reacted to the Soros hate and other anti-Semitic conspiracy theories with the same fierceness with which the Democrats responded to Omar’s comment. There has been no leadership statement condemning the mainstreaming of anti-Semitism; in fact, demonizing Soros has long been part of the overall party strategy. In 2016, Trump released a campaign ad that played a quote from one of his speeches over footage of Soros and former Fed Chair Janet Yellen (also Jewish) that comes across as an anti-Semitic dog whistle...

...“Don’t kid yourself that the most violent forms of hate have been aimed at others — blacks, Muslims, Latino immigrants. Don’t ever think that your government’s pro-Israel policies reflect a tolerance of Jews,” Jonathan Weisman, the New York Times’s deputy Washington editor and author of the new book (((Semitism))), writes. “We have to consider where power is rising, and the Nationalist Right is a global movement.”

...While the Democratic Party handled an offensive comment quickly, Republicans have never shown a willingness to do the same when it comes to right-wing anti-Semitism. There’s a reason most Jews in the United States are Democrats, and will likely remain so for the foreseeable future.

[Read Zack Beauchamp’s full piece at Vox.]

#long post#antisemitism#if you reblog or reply with antisemitism or any defense of antisemitism i will block you#if you reblog or reply with islamophobia anti blackness misogynoir or any other bigotry i will block you

145 notes

·

View notes

Text

Meeting & Subverting a Reader’s Expectations

A murder mystery needs to open with a murder!

Whenever a reader chooses something to read dictated by their own tastes and preferences they come to that story with expectations and preconceived notions in mind. A writer that managed to both fulfill and at the same time subvert those expectations and notions is going to be more successful than a writer who ignores them completely.

When you go to an action movie, you expect to see a big fight and hopefully some explosions. The faster you get to a fight scene the happier you're probably going to be. That's what you came for. And if the movie manages like The Expendables or Furious 7 to have a story that hangs on by more than a thread, then you're going to remember that movie more than a movie that doesn't. As a viewer, you got what you came for, fights, explosions, funny quips and then some, a meaningful story that made you think or tugged at the heart strings.

Every genre has conventions.

That's why they're genres. Authors ignore them at their peril. In a murder mystery, a writer needs to have a murder in the beginning of the book. If they're a detective, someone might bring them a case. If they're a bumbling amateur that is actually the town baker with an interest in history and crime then somehow they're going to stumble across this body and mystery one way or another. Or maybe they're a columnist for the local paper but aren't assigned to crime, but art or sports. Then there is another set of expectations added. The reader expects to learn something about baking or to learn something about whatever column the newspaper man is researching.

In a romance novel, the two main characters need to meet and find each other attractive. In an adventure novel, the characters are most likely going somewhere else and delivering at least one punch to the gut. In a thriller, the character needs to be escaping a deadly situation. In a mystery, a stolen item, a missing person, a dreadful secret, it all needs to be solved. In a fantasy novel... okay, that honestly depends on the fantasy novel. Speculative Fiction has gotten so fractured.

Think about the article about the "worst way to open a book from literary agents" that I linked the other day. In there two agents gave contradictory advice on how to open a book in the same genre. One said not to open with exposition and prose (such as describing the scenery or someone bringing you the mail, I suppose.) The other said not to open in the middle of a fight or an action scene. Which leaves a writer wondering what's left?

Here is the thing, it's conventional in the speculative fiction genre (fantasy and science fiction) for there to be lots of descriptions of the scenery and aliens, especially if it is harder scifi and high fantasy. The readers of those genres expect to read paragraphs about odd or magnificent landscapes. This was set in stone by writers such as Asimov, Tolkien and Burroughs. If you don't have those type of scenes in your speculative fiction novel the reader that loves that type of novel will be cheated of their expectations.

On the other hand, low fantasy, soft science fiction and most urban fantasy novels are expected to open with some sort of "action" to kick off the plot whether it's a fight or not. (Though many also go the exposition route.) In these genres, the readers care less about the scenery and the technology and the culture, they want to get to the action and to the characters as fast as possible. If there were long paragraphs about chewing the scenery, they'd be put off and go read something else.

Writers who meet the expectations of their genre in a believable way are more likely to be successful than writers that aren't.

In Shrek, the writers set up a bunch of expectations. This was a fantasy realm filled with characters we know out of fairy tales. Somewhere, there is a Princess in a tower waiting for her true love (no doubt a Prince) to rescue her. They set up a classic tale of a damsel in distress waiting for her hero. Then they made the local Lord the villain and sent an ogre to rescue her instead. Subverting all the expectations of the viewer. In fact, they built their entire marketing campaign around this. Then, in Shrek 2, they were able to do whatever they wanted because they'd already simultaneously fulfilled and subverted what the viewers of Shrek wanted to see. They wanted to see the Princess get rescued and live happily ever after. Except, she did it with an ogre. The writers didn't need to continue and write another fairy tale based story. They'd done that. They could move on to something different and potentially new. That's what made both Shrek and Shrek 2 so successful. By the end of Shrek, we wanted Shrek to win the day because he'd spent so much time talking with Donkey like they were both teenagers. And well, Shrek had done all these awesome things (without slaying the Dragon) in order to prove he was worthy of the girl. (Then found out he had some things in common with the girl. Still, two day romance, cringe.)

Of course, you don't have to be a parody to meet and subvert your reader's expectations.

Like, with the Expendables, you can write a story that caters to your readers needs and still include a message that is profound and meaningful. Or, you can choose a slightly different ending that is still plausible and then poke mild fun at what the expected ending would have been.

Going against the readers expectations are what writers and readers call twists. And as long as they are supported somehow in the story and don't come out of nowhere, then they can be surprising and feel natural. If they aren't foreshadowed in any way or feel like the writer reached into a hat of random ideas and pulled them out, then that's an unsuccessful twist. Even highly lauded writers have done bad endings and twists. And they've been called out on them, loudly and repeatedly.

Crime procedural are full of twists. Some stories have more than others over the course of the season. The writers of an episode set up several plausible suspects among the victims family, friends and coworkers. Then they'll knock them out leaving at least two as potentials and then go "ah hah, no it was really this third person all along!"

Shows like Criminal Minds also add a thriller element to their episodes. The perpetrator is still out there, committing crimes. Can they stop him before he kills another victim? (This is why I can't watch Criminal Minds, my nerves just can't take it.) The viewer expects the team to be able to find and apprehend the killer before they strike again. If they don't succeed they'd actually be subverting the viewers expectations and if it isn't made apparent that they didn't succeed this time because it's a bigger story arc, the viewers will feel cheated. They expected the heroes to win. (Because shows like Criminal Minds aren't actually reality.) If it is made apparent that they're going to try and catch the criminal another day, then the viewer will more likely feel intrigued that this is a new story arc and will continue to watch.

Timothy Zahn wrote a science fiction trilogy about humans conquering space and meeting aliens. In science fiction, you have the Star Trek types where seek out new life forms and try to be friendly. And then you have the alien invasion types like Starship Troopers, Ender's Game or Star Craft (though it's debatable on who is really doing the invading.) In the invasion types, the aliens can't or won't communicate with humans and in the Star Trek types, at least the aliens and humans share enough similar technology that they can talk to each other. Timothy Zahn took a Star Trek type situation where the humans wanted to be friendly and subverted it by making the aliens unable or unwilling to communicate. Both sides thought they other started the fight first. And it took 3 books to sort it out.

He set up an expectation, the aliens were obviously intelligent beings, but then instead of helping the humans, they in turn destroyed them and tried to attack them without explanation. As a subversion of genre expectations, it worked well. The readers still got what they came for, humans exploring space, aliens, pseudo science!

You can subvert a reader's expectations in a variety of ways, character roles, plot, a twist ending, and even setting. Star Trek was essentially "Horatio Hornblower in SPACE!" That's in a way, how urban fantasy came to be. "Fantasy creatures in the modern world!" It's okay to subvert your reader's expectations, as long as you do it consistently and still give them what they came for. Because if you don't, they may not read you ever again.

Enjoy my blog posts, please think about supporting me and buy me a Ko-Fi. Thank you!

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Misfit of Demon King Academy - S1E1

So when I was browsing anime on crunchyroll, I found this show that was pretty new. It only has 3 episodes released as of now, so I figured I’d give it a watch and keep watching and reviewing as I go on.

SPOILERS AHEAD - DUH!

The first episode begins with a slight exposition, giving us the basic premise: 2000 years ago, a demon king conquered the world and said he would reincarnate in 2000 years (aka now). Honestly, a pretty good premise, somewhat reminiscent of The Devil is a Part Timer. It takes the whole heroes vs bad guys and flips it on its head, making it so the bad guy has already won, let’s see what happens afterwards. It’s a lot to think about and It’s definitely different. However, in case you couldn’t guess, our main character is the reincarnated demon king, so we have this evil overlord demon king isekai, although to be fair, it didn’t take the age old trope of someone in modern times sleeping/dying/reading a book/playing a video game.

Interestingly enough, we don’t see the demon king’s original demise at first. Interestingly enough, we don’t meet our main protagonist first. We actually meet a female companion named Misha as she and our main character are about to take an exam at a demon academy. Almost immediately, we have a stereotypical bully-type character named Zepes, who is used as a bunching bag multiple times, once outside the academy and once more during the practical exam, where our main character kills him and resrurrects him multiple times, just because he can. In fact, in case the writers thought you were so dense you couldn’t comprehend how powerful our main character (as well as our first main female character) are, Misha gets a score in the 100,000 range while most scores are in the 100-300 range, and our main character gets a score of 0 and breaks the scale.

Yes, the writers are blatantly admitting how op the main character and his companion are compared to everyone else, and everyone else isn’t concerned, because LOGIC.

The only interesting parts of the exams was the aptitude test and the brief worldbuilding we get during the practical exam. During the aptitude test, we finally know our main character’s name, Anos Voldigord, and the fact that he burnt down his homeland to ressurect the populace into powerful zombies. Other than that, we sadly don’t get anymore information about the world, which I honestly would have preferred than multiple displays of how OP our main character is, which include killing Zepes multiple times with his heartbeat and snaps of his fingers. Just call him G-d at this point, except well, in his past life Anos killed the gods, so hooray? The other good part is at the beginning of the practical exam, where Zepes reveal anti-Demon armor that resists Anos’s original attack of magic being sent through the vibrations of his voice, only to be completely ignored 5 seconds later when Anos’s heartbeat, an attack that has magic sent through the vibrations of his heartbeat. Zebes also reveals a fire sword but it’s useless because Anos snuffs out the fire again. Whoopee, super interesting. I wonder if the combat will get as exciting as the practical exam.

After this mess of an intro, we get the gratuitous “the main character has a female friend, so let’s assume they’re dating and going to be married” trope, as Anos brings Misha to his place to celebrate them passing their exams. There, we meet Anos’s “parents”, as well as the fact that Anos’s reincarnated self is only a month old. Everyone is unreasonably cool, and it’s honestly stupid how now one, not even his parents, suspect that he is the resurrected Demon King based on how OP he is and how fast he has grown. What’s even more strange is how Misha responds to the parents calling her his “wife he brought home”, being unnaturally calm about it. I can see that it’s a way to subvert the classic trope, but it just feels like the same trope, but weaker now that Misha doesn’t give an actual embarrassing reaction. However, I can see that the writers were showing how Misha isn’t easily embarassed and is a different kind of female character than in normal Isekais, so it’s honestly fine, just kind of disappointing.

We end off the episode with Anos walking Misha home, and the topic of Anos being the Demon King still isn’t brought up, because everyone dumped their Wisdom stat and can’t relize that breaking the magic scale and killing a guy and resurrecting home over and over again, especially after audience members are shocked at the resurrection part due to it never having been performed recently, isn’t exactly normal. Suddenly, the arean from the practical exam gets copy-pasted around our heroes and Zepes’s older brother Leorg, along with some guards and Zepes himself, come to exact revenge on our hero because Anos embarassed Zepes. You see, they believe Anos is a hybrid, who is someone with magic who isn’t a noble. In other words, it’s the writers stuffing class warfare/discrimination into this anime because every fantasy anime has to have it at this point. So now we have nobles trying to kill Anos because he’s a filthy hybrid who’s better than them, yada-yada-yada, Leorg kills Zepes, Anos get ready to fight....WAIT WHAT?

Yeah. For some god-forsaken reason, Leorg kills his younger brother Zepes. The reasoning behind this is because Zepes embarssed his family. This doesn’t make sense. Leorg should want to keep his brother alive because in case Leorg dies, Zepes can immediately take over as the Demon Lord replacing his brother and keeping the family in power. Killing Zepes after being bested in combat isn’t honestly one of the stupidest things Leorg could have done. Anyway, now we get actual combat. Let’s hope Anos actually takes a step this time (spoiler alert, he doesn’t).

I swear, this anime should be called, how to beat up everyone while doing nothing, because that’s all Anos does with combat. First, Leorg and his guards try to launch magic attacks, but Anos thinks for a bit and causes their magic circles to spiral out of control, making them blow up in everyone’s faces. Next, Leorg decides it’s time to launch the big guns, and uses what is called origin magic. This is actually a neat concept that I’ve never seen before, so I have to give the writers credit for this one. Basically, origin magic takes magic from someones ancestor, in this case the demon king himself, and uses it temporarily. It’s like your parents letting you drive their car for a bit because your car is a piece of crap. So they launch it at Anos and Anos doesn’t move, surely he’s not dead, right?

Anos is untouched, and do you know why? Because origin magic can’t affect the origin, and because Anos is the Demon King, aka the origin, he can’t be affected by origin magic. It’s admiteddly kind of dumb and it’s really only used to make Anos seem cool, because i mean, I can still hypothetically run over my parents with their car, right?

Anyway, after that, Anos decides to zombify Zepes and show them how zombies work. Because one one has seen a zombie yet, this is a perfect time to explain to the audience that zombies gain more magic power and are full of revenge against their killer. Anos tries to make Leorg assert control over the zombie and get the both of them to attack Anos, but Leorg argues that it’s mindless and won’t follow his orders, so Anos tells Leorg to speak zombie Zepes’s name to stop him, but because their bond is weak, they both die. After the arena starts collapsing because Leorg is dead, Anos shows more how OP he is (for the billionth time) by stopping rocks, resurrecting everyone, and shielding Misha. Finally, because Leorg still doesn’t get that Anos is the Demon King, Anos introduces himself, and we get the credits.

Final thoughts:

The concept was what really brought me to start this anime, and when I found it was just another Isekai with random tweaks, I immediately got turned off. The writers are only writing to subvert expectations and not to write a good story, with the main protagonist showing off their power any chance they can get, getting only slight confusion from new inventions. It’s a story that’s been told time and time again with nothing new to add to the table. Overall, a bad first impression. I’ll still watch it, hoping that I might just be wrong, but I’m not expecting any miracles.

Additional Comments and Comparisons:

Here are some additional thoughts/questions about the episode. Throughout the episode, we can see Anos being kind. He picks up Misha’s letter, he defends Misha from Zepes, his parents describe how kind Anos is to Misha, etc. There’s a lot of kindness here, something that doesn’t seem right for a Demon King. As of now, this kindness isn’t addressed, which is understandble, but my question is, when will it be? Let me compare this instance of “is the bad guy pretending to be nice or nah” to how it was handled in The Devil is a Part Timer (This question may have been handled differently in the light novel or manga series but for the sake of argument, let’s focus solely on the anime). In it, Sadao Mao, aka Satan, retreats from his world, Ente Isla, to Earth, originally to plan his reconquering of Ente Isla. Throughout the series, Sadao’s intentions are repeatedly questioned by the Hero and her comrades, thinking that Sadao is simply being kind because it benefits him the most and that he will eventually turn on them and reconquer Ente Isla, despite how much he denies it. The truth is, this question, at least in the anime, is not fully answered. We don’t know Sadao’s intentions and we’re left wondering whether or not we should sympathize with Sado or not. It’s honestly great how they handled it because, at least in the anime, we don’t know. Also, on the topic of The Devil is a Part Timer, they handle Sadao’s power/OP-ness beautifully. It’s so simple, yet it solves the problem that many other Isekai protagonists struggle with. We know that Satan is powerful on Ente Isla, but when Sadao is on Earth, because Earth doesn’t have magic (or rather, it has very little magic), Sadao and anyone else from Ente Isla can’t use their magic. It’s a simple fact that keeps Sadao in check and reveals his true power only when it’s actually necessary. Sadao doesn’t waste magic on the Hero when she arrives, nor does he use it on anyone he feels like. He uses it only when necessary, unlike Anos, who’ll show off everything on a simple bully character.

0 notes

Text

Summer 2017 Anime Overview: My Hero Academia Season 2 and KiraKira Precure a la Mode

We return to our look at the summer 2017 anime. I’ve been reviewing the seven anime I watched from worst to best. Previously I talked about the two weakest anime I watched and an anime that was kind of mixed and middling. Now we’re going to talk about too anime I watched that I consider to be Very Good and would overall recommend (with some warnings and caveats regarding some stuff for one of them). Let’s dig in!

My Hero Academia Season 2

I found the first season of My Hero Academia to be pretty good but nothing to get excited about- but damn, this season officially sucked me in. I am now a Fan. Very unwillingly, I might add, but the show wrestled my doubting heart into submission with its endearing characters. fight-y fun and surprisingly good handling of growth and relationships (for the most part).

The basic concept behind My Hero Academia is that in a world where most people have some form of superpower, superheroism is considered a legit profession. Nerdy teenager Izuku Midoriya really wants to be a hero, but he’s one of the few people born without superpowers. However, when he encounters his idol, the number one hero All Might, everything changes and he soon finds himself enrolled in the top-ranked superhero academy.

MHA sparked my interest by being a superhero show (I’m a huge comics nerd) and kept me interested by having a legit adorable and sympathetic protagonist (Midoriya is very earnest and also cries a lot, both things I find intensely cute and relatable), good animation and generally solid fights and storytelling. But it wasn’t really until this season that it came into it’s own as an impressive ensemble show. It subverted quite a few expectations I had, in a really good way and delivered on some pretty incredible character work and interesting world building. Also, it has a great soundtrack.

The season opened with a tournament arc, and I usually find those pretty boring in shonen (though still good, they were easily my least fave parts of HXH, for instance) but this one really mixed things up by weaving in some really good emotional hooks for the one-on-one fights and actually *gasp* developing characters and rivalries that WEREN’T focused on the protagonist.

Rather than going the safe and expected route of having a big match-up be between Midoriya and his intimidating, violent explosion-happy rival, the series showed us a fight between explosion dude and the adorable, sweet main female character (whose superpowers were NOT well-suited for fighting his explosions) and used it to showcase her determination even against incredible odds and further her story along.

It also explored her motive for being a hero- her family isn’t well off and she wants to make some serious cash so they can live in comfort. She worried this motive was “unheroic” but was reassured it was admirable, which was nice to see, especially considering how female characters are generally discouraged from being ambitious.

But the biggest highlight of the arc was the exploration of one character’s trauma and abuse. An arc revolved around a characrer (Todoroki Shouto) having difficulty using the powers he inherited from his abusive father. The story was heartbreaking and well-done and addressed in a very moving way with a very emotional “you are not your parents, it’s your power and body, not theirs” core- but what really impressed me was that the arc’s acknowledgement that this kid’s recovery would not be instantaneous and it was going to be a long and difficult process involving many other steps.

In most shows, once Todoroki had gotten his weird therapy session courtesy of the protagonist, Midoriya, and had been able to use his powers once, it would have been over, done, he’s fixed and he can totally use them now. But instead, the show acknowledged that being able to overcome his trauma enough to use them for a few minutes didn’t mean he’s now so recovered he can just use them whenever he wants. Todoroki realized that he had a lot of unresolved issues he needed to work through and a lot of steps he needed to take before he could recover enough to be truly comfortable with using his powers all the time. “It’s not that I’ve accepted anything, it’s just that, for a moment, I was able to forget about [my dad]”, as he put it. And the show showed us that it had every intention of following him through that recovery process.

Seeing this over-the-top show about superpowers and fights where people suffer ridiculous injuries actually approach trauma recovery in a realistic and nuanced way really shocked me and also majorly tugged by heartstrings. The whole conflict also added some depth to the show’s world building- Todoroki’s scumbag dad is one of the top superheroes out there, despite being a totally horrible person. When being a superhero is a competitive profession rather than a calling you get people who aren’t necessarily “good” or into “saving people” as much as they are in it to make a profit and show off their powers. Which went nicely with the themes of the arc that followed the tournament arc.

The way the show plays around with typical shonen tropes is also great- the show has the highly gifted, arrogant once-upon-a-time-they-were-friends rival for our main character, but he doesn’t become insufferable like most of those characters because the show makes fun of him constantly. None of the other characters put up with his bullshit or take him seriously, he’s constantly called out and made fun of for his asshole attitude and the main character finds him genuinely unpleasant to be around and tried to avoid him socially. This allows his ANGRY EDGELORD nature to be funny rather than annoying, because the show’s in on it too.

And while Todoroki also could have also been a brooding asshole rival character, he’s pretty quickly to be revealed as a nice, kinda dorky guy who’s just quiet, awkward and introverted due to trauma and lack of social interaction. The show’s really self aware in how if plays with these character archetypes for the most part, and that makes it a pleasure to watch.

The show continued its solid character work, punctuated by dramatic and well done fight scenes, through the next arc. Almost every single kid on the show got a moment to shine this season, and you got to know them as characters and heroes and I came to realize- hey, I REALLY LIKE most of these characters.They’re being developed in a fun and interesting way, and they have lives and motivations that don’t just revolve around the main character. And the relationships and dynamics between the various characters are fun and heartwarming too.

And this includes the girls, who, while definitely outnumbered by the boys and underutilized compared to them, are really competent, interesting and have some great moments and arcs going. I especially enjoyed the mini-arc where one of the girls lost confidence in her ability to lead and thought a dude would be better at it, only for him to assure her she’s way better suited for it than him. Always nice to see ladies in command being respected by the dudes with them.

But that does bring us to the fact that while it has some good female characters, the show also has some pretty big sexism issues. All the older female heroes we’ve seen so far are basically walking sex jokes/fanservice dispensers and even some of the younger female characters are uncomfortably sexualized (Momo’s got the classic “oh she has to wear a ridiculously impractical costume because her powers require it” aka “I gave this teenage female character these powers specifically so I could sexualize her”). The fanservice gets to the point of distracting from the plot at times.

There’s a huge absence of female mentors so far (I hear that gets better later) and out of the entire teaching staff of the school, only one is a woman (and her character boils down to “bondage joke”) What’s more, while the girls are good fighters, their powers tend to be less offensive and "powerful” than the boys (this is especially obvs if you look at their official stats). Oh and there’s this fucker:

...who routinely sexually harasses and assaults his female classmates and it’s supposed to be funny and harmless. Every single time this asshole comes on screen u have to put up with a deluge of gross-ass comments and seeing the female characters repeatedly be objectified and have their space invaded. And no, them hitting him or other characters saying it’s gross does not make it okay. It’s still allowed, it’s still clearly there to be “funny” and “titillating” and it still uses girls being abused as a “fun” interlude. That’s NOT okay. It’s not funny. He adds nothing to the show, he just grinds everything to a halt and makes everything uncomfortable. It’s jarring, and takes you out of an otherwise well done story. I really want him and this type of “humor” to be ejected from the show.

But yeah, with those major issues in mind (and god I wish they weren’t there), I still really enjoyed MHA and can’t wait until the next season. The plot’s ramping up and I can’t wait to see where it goes next.

KiraKira Precure a la Mode

Kira Kira Precura a La Mode follows a group of magical girls with superpowers based on both sweets and animals. They run a pastry shop together and protect their city from monsters who want to suck the energy of people who are happily enjoying their favorite confections.

Okay, this is still ongoing, but I think it’s safe for me to say at this point that KiraKira is well on its way to being one of my favorite Precure shows, which considering how I’m a pretty big Precure fan, says a lot.

The writing is solid, the characters are fun and well-developed and the animation and art design is well-done and adorable.

This season added a few fun new touches to the Precure formula, including having two older girls on the team- a pair of 17 year olds hanging with the 14 yr olds (14 is the typical age for Precure protagonists). This pair is a butch and femme couple pretty clearly patterned after Haruka and Michiru- and yes, that also means they are fairly blatantly a lesbian couple.

There is in fact an entire episode revolving around Yukari (femme cat magical girl) trying to make Akira (butch dog magical girl) jealous by threatening to marry a prince and making Akira compete with him for her love. All the while, Akira struggles with whether she should share her true feelings with Yukari. This culminates in a big love confession scene that added ten years to my life. Seeing the younger girls aggressively encourage and support their relationship is great too.

So yeah, about as blatant as S-season Haruka and Michiru- which, if you understand that reference, means there ARE some scenes that try to cast ambiguity on the relationship. This one, for instance, where Akira acts flustered in response to the prince’s suppositions about her relationship with Yukari (and his incorrect assumption about her gender), makes sense in the context of a just forming relationship, but also didn’t add much to show and was likely included so the show could make it seem ambiguous if Yukari and Akira will truly enter a relationship.

However, it has been a long time since we’ve gotten lesbians this blatant in a magical girl show aimed at young girls. Ever since the days of Cardcaptor Sakura and Sailor Moon, gay subtext and text in magical girl shows has been much lighter (and heck, even fanservicey aimed-at-guys magical girl shows don’t seem to have the guts to have girls kiss).

So the fact Precure is now deliberately homaging and emulating Haruka and Michiru and doing blatant love triangle/confession scenes IS a big deal and a step in the right direction. It’s sad we haven’t progressed since the days of Sailor Moon, but it’s good we’re at least not regressing anymore. And while Akira and Yukari haven’t gotten the word of god “Yes they are lesbians” confirmation Naoko Takeuchi gave Haruka and Michiru, (at least, not any we’ve heard of in the West), I wouldn’t say it’s outside the realm of possibility that could happen. (I really doubt the “lol we’re having sex” lines similar to what we got in Sailor Moon Stars will happen though, just because Precure doesn’t do sexual innuendo).

And it’s worth mentioning, we do have an official duet song for Yukari and Akira that’s VERY blatantly romantic. “Koi” is even in the title.

Yukari and Akira are a censored relationship for sure, and it’s obnoxious and wrong those censors are still in place (though not surprising, considering this is a big corporate studio running Precure). They should be able to kiss, they should be openly dating. However, they are obvious enough that if they were a straight couple, we’d be calling them canon at this point, so I’m gonna. Also, I have to shout out that they’ve poured on Utena references GALORE with these two, and I’m super into that.

It should also be noted that Akira is allowed to maintain her butchness even after transforming into a magical girl- she gets a frilly PRINCE outfit. That’s a first for a magical girl show aimed at girls (unless you count Utena, which I don’t for various reasons). She’s never derided for her lack of femininity either (in fact she’s considered cool and attractive) which is a very good affirming message for young girls. There’s also another episode that frames rebellion against enforced traditional femininity as a good thing and has women standing up for and supporting other women who don’t follow gender roles.

To state the obvious, Precure is a show that exists in a capitalist society. So it’s focused on selling toys to little girls and those toys are often stereotypically hyper-feminine. However, it’s still valuable and positive that this show is casting non-gender conforming heroes in a positive light- if a little girl wants to play as Akira, she might have a pink compact, but she can use it to become a dashing butch prince. The lines are blurring in a good way.

Yukari is also notable as a great character- she’s not the genki girl archetype, but messy, petty and a bit cynical. She’s complex. The episodes where she struggles with whether she’s a “good girl” are pretty inspiring and carry the message girls can be heroes even if they’re not all sunshine and daisies.

In fact, all the characters in the season are ALL pretty solid. Their relationships are fleshed out and so are their arcs. The dynamic the whole team has is great. The villains redemption arcs are strong as well. And as always, it’s cute as heck and bursting with lady friendship feels.

My biggest problem with this show would be pacing- it suffers from being two rushed a lot of the time, and often tries to cram way too much in one episode rather than giving conflicts and arcs room to breathe. But that’s my only big issue.

It’s possible KiraPre could have a disappointing finale, but I at least feel confident it won’t end in total disaster. It shows none of the warning signs shows like Hachepre did- there’ve been no love triangles, bland male love interests or anything of the sort shoehorned in, so I don’t feel I have to worry about the worst happening (the “worst” being “the finale revolves around soothing a dude’s wounded ego, with the bond between the magical girls and their power being sidelined for the sake of really uncomfortable and contrived het romance”, if you haven’t seen HachaPre).

Let’s hope KiraPre’s finish is as strong as the rest of it has been!

#my hero academia#kirakira precure a la mode#kira kira precure a la mode#anime overview#summer 2017 anime

52 notes

·

View notes

Text

For the Love of an Unworthy White Man

In October 2018, I finally saw Miss Saigon, after deliberately boycotting it for almost thirty years.