#emily brontё

Text

— How did you write it? How did you write "Wuthering Heights"?

youtube

#emily#emily 2022#emily bronte#emily brontё#emma mackey#bronte sisters#bronteedit#wuthering heights#charlotte bronte#jane eyer#Youtube#heathcliff#catherine earnshaw#catherine x heathcliff#literature#english literature#classic literature#period drama#film edit

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

JOMP Book Photo Challenge, August 2021.

Day 12: Retelling

From top to bottom, the title and author of the book with the work it is a retelling of in parentheses:

Under a Dancing Star by Laura Wood (William Shakespeare's Much Ado About Nothing)

The Wrath and the Dawn by Renee Ahdieh (A Thousand and One Nights)

Hood by Jenny Elder Moke (Robin Hood)

Waking Romeo (Shakespeare's Romeo and Juliet and Emily Brontё's Wuthering Heights)

#beautifulpaxiel reads#justonemorepage#jompbc#book photography#mine#book stacks#book photography challenges

10 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Fantastika Journal, Volume 4, Issue 1, edited by Kerry Dodd, July 2020. Cover art by Sinjin Li, info and free download: fantastikajournal.com.

“Fantastika” – a term appropriated from a range of Slavonic languages by John Clute — embraces the genres of Fantasy, Science Fiction, and Horror, but can also include Alternate History, Gothic, Steampunk, Young Adult Dystopic Fiction, or any other radically imaginative narrative space. The goal of Fantastika Journal and its annual conference is to bring together academics and independent researchers who share an interest in this diverse range of fields with the aim of opening up new dialogues, productive controversies and collaborations. We invite articles examining all mediums and disciplines which concern the Fantastika genres. This special issue is based off the fifth Fantastika conference — After Fantastika — which investigated how definitions of time are negotiated within Fantastika literature, exploring not only the conception of its potential rigidity but also how its prospective malleability offers an avenue through which orthodox systems of thought may be reconfigured. By interrogating the principal attributes of this concept alongside its centrality to human thought, this issue considers how Fantastika may offer an alternate lens through which to examine the past, present, and future of time itself.

EDITORIAL

After Bowie: Apocalypse, Television and Worlds to Come – Andrew Tate

ARTICLES

In the Ruins of Time: The Eerie in the Films of Jia Zhangke – Sarah Dodd

The Time Machine and the Child: Imperialism, Utopianism, and H. G. Wells – Katie Stone

“Turn[ing] dreams into reality”: Individual Autonomy and the Psychology of Sehnsucht in Two Time Travel Narratives by Alfred Bester – Molly Cobb

Dystopian Surveillance and the Legacy of Cold War Experimentation in Joyce Carol Oates’s Hazards of Time Travel (2018) – Nicolas Stavris

“THE ONLYES POWER IS NO POWER”: Disrupting Phallocentrism in the Post-Apocalyptic Space of Russell Hoban’s Riddley Walker (1980) – Sarah France

“Then when are we? It's like I'm trapped in a dream or a memory from a life long ago”: A Cognitive Analysis of Temporal Disorientation and Reorientation in the First Season of HBO’s Westworld – Zoe Wible

Rewriting Myth and Genre Boundaries: Narrative Modalities in The Book of All Hours by Hal Duncan – Alexander Popov

NON-FICTION REVIEWS

Science Fiction Circuits of the South and East (2018) edited by Anindita Banerjee and Sonia Fritzsche – Review by Llew Watkins

The Evolution of African Fantasy and Science Fiction (2018) edited by Francesca T. Barbini – Review by Esthie Hugo

We Don’t Go Back: A Watcher’s Guide to Folk Horror (2018) by Howard David Ingham – Review by Marita Arvaniti

Witchcraft the Basics (2018) by Marion Gibson – Review by Fiona Wells-Lakeland

Gaming the System: Deconstructing Video Games, Game Studies, and Virtual Worlds (2018) by David J. Gunkel – Review by Charlotte Gislam

Twin Peaks: Fire Walk With Me (2018) – Review by John Sharples

Children’s Literature and Imaginative Geography (2018) by Wilfrid Laurier – Review by Chris Hussey

Sleeping with the Lights on: An Unsettling Story of Horror (2018) by Darryl Jones – Review by Charlotte Gough

Posthumanism in Fantastic Fiction (2018) edited by Anna edited by Anna Kérchy – Review by Beáta Gubacsi

Old Futures: Speculative Fiction and Queer Possibility (2018) by Alexis Lothian – Review by Chase Ledin

The Theological Turn in Contemporary Gothic Fiction (2018) by Simon Marsden – Review by Eleanor Beal

Reified Life: Speculative Capital and the Ahuman Condition (2018) by Paul J. Narkunas – Review by Peter Cullen Bryan

Mind Style and Cognitive Grammar: Language and Worldview in Speculative Fiction (2018) by Louise Nuttall – Review by Rahel Oppliger

None of this is Normal: The Fiction of Jeff VanderMeer (2018) by Benjamin J. Robertson – Review by Kerry Dodd

The Last Utopians: Four Late 19th Century Visionaries and their Legacy (2018) by Michael Robertson – Review by Peter J. Maurits

Once and Future Antiquities in Science Fiction and Fantasy (2019) edited by Brett M. Rogers and Benjamin Eldon Stevens – Review by Juliette Harrisson

Bodyminds Reimagined: (Dis)ability, race, and gender in Black Women’s Speculative Fiction (2018) – Review by Polly Atkin

Modern Dystopian Fiction and Political Thought: Narratives of World Politics (2018) by Adam Stock – Review by Ben Horn

CONFERENCE REPORTS

Reimagining the Gothic 2018 (October 26-27, 2018) – Conference Report by Luke Turley

Transitions 8 (November 10, 2018) – Conference Report by Paul Fisher Davies

Looking into the Upside Down: Investigating Stranger Things – Conference Report by Rose Butler

Tales of Terror (March 21-22, 2019) – Conference Report by Oliver Rendle

Glitches and Ghosts (April 17, 2019) – Conference Report by Vicki Williams

Glasgow International Fantasy Conversations (May, 23-24, 2019) – Conference Report by Benjamin Miller

Gothic Spectacle and Spectatorship (June, 1, 2019) – Conference Report by Brontё Schiltz

Current Research in Speculative Fiction 2019 (June 6, 2019) – Conference Report by Phoenix Alexander

Legacies of Ursula K. Le Guin: Science, Fiction and Ethics for the Anthropocene (June 18-21, 2019) – Conference Report by Heloise Thomas

Folk Horror in the 21st Century (September 5-6, 2019) – Conference Report by Miranda Corcoran

FICTION REVIEWS

Modern Monsters and Occult Borderlands: William Hope Hodgson. A Review of The Weird Tales of William Hope Hodgson (2019) – Review by Emily Alder

From the Depths. A Review of From The Depths; And Other Strange Tales of the Sea (2018) – Review by Daniel Pietersen

‘Shun the Frumious Bandersnatch!’: Charlie Brooker, Free Will and MK Ultra Walk Into A Bar. A Review of Black Mirror: Bandersnatch (2018) – Review by Shannon Rollins

The Power of the Everyday Utopia: Becky Chambers’ Record of a Spaceborn Few. A Review of Record of a Spaceborn Few (2018) – Reviewed by Ruth Booth

Another Green World. A Review of A Brilliant Void: A Selection of Classic Irish Science Fiction (2019) – Reviewed by Richard Howard

Burn Them All? Game of Thrones Season Eight. A Review of Game of Thrones Season Eight (2019) – Reviewed by T Evans

Making New Tracks in African Fantasy. A Review of Black Leopard, Red Wolf (2019) – Reviewed by Kaja Franck

Impossible Creations for the Gothically Minded. A Review of The Curious Creations of Christine McConnell (2018) – Reviewed by Rachel Mizsei Ward

In a Broken Dream: The Home for Wayward Children Series. A Review of Down Among the Sticks and Bones (2017), Beneath the Sugar Sky (2018) and In an Absent Dream (2019) – Reviewed by Alison Baker

Blackfish City: A Place Without a Map. A Review of Blackfish City (2018) – Reviewed by Lobke Minter

Diné Legend Comes to Life in Rebecca Roanhorse’s Trail of Lightning. A Review of Trail of Lightning (2018) – Reviewed by Madelyn Marie Schoonover

Aquaman; or Flash Gordon of the Sea. – A Review of Aquaman (2018) – Reviewed by Stuart Spear

The Tower of Parable. A Review of The Writer’s Block (2019) – Reviewed by Timothy J. Jarvis

#magazine#journal#literary journal#fantastika#weird essay#horror essay#weird reviews#horror reviews#weird studies#horror studies#gothic studies

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

Was Emily Brontё's Heathcliff black?

Was Emily Brontё’s Heathcliff black?

All the evidence points to Brontё’s most famous outcast being a product of the British slave trade. Source: Was Emily Brontё’s Heathcliff black?

View On WordPress

#BLACK HISTORY#Emily Brontё#Heathcliff#product of the British slave trade#Slavery in Yorkshire#Wuthering Heights

0 notes

Quote

[...] with the glow of a sinking sun behind, and the mild glory of a rising moon in front ̶

Emily Brontё, from ‘Wuthering Heights’ (1847)

35 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Was Emily Brontё’s Heathcliff black?

The novel’s most famous action takes place on the moorlands surrounding the quaint Yorkshire village of Haworth – and moorlands are traditionally associated with uncivilised regions. Heathcliff embodies this idea – he is depicted as the quintessential “savage” whose foreignness establishes his position at civilisation’s periphery.

But historians have found abundant evidence to suggest that Heathcliff’s foreignness is not merely symbolic – it makes historical sense. The novel is set in 1801, when Liverpool handled most of Britain’s transatlantic trade in enslaved people. Evidence of this terrible trade could be seen everywhere – the Brontё critic Humphrey Gawthrop records that: “[William] Wilberforce’s colleague, Thomas Clarkson … saw in the windows of a Liverpool shop leg-shackles, handcuffs, thumbscrews and mouth-openers for force-feeding used on board the slavers.”

#wuthering heights#emily bronte#heathcliff#yorkshire#england#history#black history#slave trade#lit#corinne fowler

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Episode #18 – Epilogue, What Epilogue?

In this episode of Radio Free Fandom, my guest Julianne & I talk about the Harry Potter fandom and our experiences with it as the books were being released, compared to now. We’ll also recommend some hopeful speculative fiction.

Mentioned in this episode

The Sorting Hat Chats primary/secondary Sorting system

The Mirror of Maybe by Midnight Blue, a sprawling fic from the mid-2000s, still marked as in-progress

Golden Age by zeitgeistic, a Hogwarts Eighth Year fic in which students are re-Sorted into secondary Houses

Books Recommendations

Station Eleven by Emily St John Mandel

The Martian by Andy Weir

On The Edge Of Gone by Corinne Duyvis

The Wayfarer Universe series by Becky Chambers

Sunvault: Stories of Solarpunk and Eco-Speculation edited by Phoebe Wagner and Brontё Christopher Wieland.

Seveneves by Neal Stephenson

Lillith’s Brood series by Octavia Butler

Time Stamps:

00:04 Intro

00:46 The Harry Potter Fandom, Then & Now

35:50 Hopeful Speculative Fiction Recs

55:21 Outro

Find Claire online:

Twitter: @ClaireRousseau

Website: http://www.clairerousseau.com/

Youtube: https://www.youtube.com/user/ClaireRousseau

Find Elizabeth online:

Twitter: @books_pieces

Instagram: @thebooksandpieces

Youtube: Books And Pieces

If you have comments or questions, you can email the podcast at [email protected] or tweet us @RadioFreeFandom.

Thanks for tuning in to Radio Free Fandom!

from WordPress https://ift.tt/2moQXdy

via IFTTT

0 notes

Text

“Scrivere è sollevare un microscopio e accudire un bambino”: dialogo con Tracy Ryan, la Sylvia Plath australiana

Non è un abuso giornalistico. Il paragone tra Tracy Ryan e Sylvia Plath ricorre un po’ in tutti i repertori critici. Lei, classe 1964, tra i poeti più originali e riconosciuti in Australia, non si tira indietro, riconosce il debito d’ispirazione con la Plath, ma anche quello con Ted Hughes e Rainer Maria Rilke, ad esempio, e marca delle rigorose distanze. D’altronde, è poesia rigorosamente australe, sghemba all’ovvietà narrativa, quella della Ryan, che procede per densità verbali, tenta la rabdomante anomalia del quotidiano. Poesia colta, che trafigge con oracoli meridiani, condotta da quasi 25 anni – la prima raccolta, Killing Delilah, è del 1994, l’ultima, The Water Bearer, “così piena di intima intensità, di limpidezza visionaria, sintesi lirica di uno dei poeti australiani viventi più noti e premiati” (Marion May Campbell), da cui provengono le poesie che abbiamo tradotto in calce all’intervista, è pubblica quest’anno – con ostinata coerenza formale e formidabile impeto ‘etico’. L’esperienza lirica della Ryan – che ancora attende un degno riconoscimento in Italia – attraversa le tradizioni, sia per la biografia dell’autrice – nata in Australia, ha lavorato a Cambridge e ha vissuto negli Stati Uniti, in Ohio – che per la natura della sua poesia. Spifferi di Emily Dickinson e barriti di Baudelaire, infatti, s’imprimono nella sua poesia, onnivora. “Non appartengo ad alcuna scuola di pensiero”, ha detto, in una riflessione del 2001, “in senso più ampio la mia scrittura è inestricabilmente legata al mio femminismo”. Alla sua femminilità, pare, leggendo Tracy. Anarchica, inafferrabile, virile.

Da dove proviene la tua ispirazione poetica? Sei ispirata da un fatto, un evento storico, un elemento naturale, un’illuminazione improvvisa… Che cos’è la poesia?

Può arrivare assolutamente da qualsiasi parte: è la sensazione che prendere e sorreggere un pesante microscopio assomigli a tenere in braccio e allevare un bimbo. Deriva dal riconoscere il rumore dei passi del tuo compagno sulle scale, un rumore che distingui minuziosamente dalla camminata di chiunque altro. Più lo tengo in considerazione, più mi rendo conto che ciò accade in modo specifico attraverso ciascuno dei sensi; a volte in più percezioni contemporaneamente… La certezza fisica che, per esempio, dopo la gravidanza continui a fare più spazio del necessario o senti la mancanza del peso del bambino sul tuo fianco, sul tuo braccio. Queste cose sembrano banalità ma non lo sono, dal momento che comportano connessioni psicologiche, sociali e anche spirituali. Tutto questo, scontrandosi con il lavoro altrui – perché l’ispirazione arriva anche da altre poesie, corre attraverso il vaglio (mescolare la metafora) delle tue stesse esperienze.

Ho letto che la tua poesia è stata avvicinata ai poemi di Sylvia Plath, una poetessa molto conosciuta in Italia. Ti intimidisce questo confronto, pensi sia corretto? Quali sono i poeti che ami di più? Quali poeti – vivi o morti – hanno contribuito alla tua crescita poetica?

Come molti altri poeti, sono profondamente debitrice nei confronti del lavoro della Plath. Non penso che il mio lavoro assomigli così tanto al suo, tematicamente quasi per niente, anche se nella tecnica e nel mestiere lei è per me un grande esempio. Questo non è insolito, specialmente nella mia generazione che le succede direttamente (lei appartiene all’era dei miei genitori). Sono stata influenzata da così tanti poeti che è difficile menzionarli tutti, ma in modo cruciale da entrambi, sia dalla Plath che da Ted Hughes, quanto, allo stesso modo da Theodore Roethke; ma anche dagli australiani Judith Wright, che ho studiato a scuola, e da Dorothy Hewett. Di epoche precedenti, ho imparato da John Donne, George Herbert e poi da Gerard Manley Hopkins. Ritorno continuamente a Emily Dickinson e a Emily Brontё. Per quanto riguarda i poeti non inglesi invece, assolutamente Rainer Maria Rilke e probabilmente Baudelaire, nonostante tutti i problemi con lui!

Pensi che esista una particolarità della scrittura ‘femminile’? Cosa c’è di diverso da quella ‘maschile’?

Non penso che l’originalità o la differenza sia assoluta. Penso si tratti piuttosto di un disposizione, una tendenza o un punto di vista – ma nessuno precipita ordinatamente in un ‘campo’ piuttosto che in un altro – il ‘genere’ non è così semplice, come le persone stanno finalmente iniziando a riconoscere! (alcune persone lo hanno sempre riconosciuto). Detto questo, penso che ci siano stati elementi che la scrittura delle donne abbia evidenziato per via di una differenza storica nell’esperienza, una esperienza spesso svalutata. Intendo gli standard di giudizio in base ai quali un particolare argomento era considerato banale o personale perché allineato con l’esperienza tipicamente ‘femminile’. Queste categorie sono state messe in dubbio già da molto tempo. Io sono una femminista, ma ciò non significa che accetti qualsiasi opinione le persone associano a quella parola.

Che rapporto tra etica ed estetica? Quando scrivi, risolvi solo un problema formale o ti preoccupi anche del fatto ‘politico’, sociale, ambientale?

Penso che etica ed estetica siano inscindibili, nonostante si tenda a separarli. Tuttavia, non so con chiarezza a quale posizione etica attingere. Risolvere un problema formale è semplicemente una piccola parte della scrittura, anche se a volte risulta essere la parte più difficile. Preoccuparsi riguardo ai problemi che hai menzionato è sempre un punto fisso per me, nonostante a volte sembri più uno ‘sfondo’ piuttosto che un argomento centrale, decisivo.

Ho letto che hai vissuto in Inghilterra, negli Stati Uniti e in Australia. Quali sono le caratteristiche della poesia Australiana?

La questione è troppo vasta per poter generalizzare.

Su cosa stai lavorando ora, che libro stai scrivendo?

Ho un nuovo romanzo che uscirà quest’anno e la maggior parte delle mie energie le ho impiegate in questo. Allo stesso modo in cui gli attori amano dire, enfaticamente, che sono ‘nella parte’ o ‘tra impegni’, io sono ‘in mezzo ai libri’ al momento!

*

La settima nuotata

Quando l’uomo con la barba bianca

l’ho confuso con una maschera la scorsa settimana

viene di nuovo, io scelgo di restare.

Senza parole, come una mezz’onda.

mi muovo, lascio a lui la parte migliore

mantenendo il passo.

Deve ricordare come sono fuggita,

in quel momento, supponendo la modestia

forse, ma così non è.

Terminato con il pigro galleggiante

la rimozione del pensiero

ora devo apparire una che nuota.

La compagnia designa perimetri

linee invisibili tracciate

pur non essendo te stesso.

Ineleganti, instabili

noi fuggiamo dalla stessa fine

come due che inaugurano l’atto del parlare

nel medesimo istante

qualcuno deve sopraffare

o l’altro soccombe.

Eppure mi basta solo

il mio naturale languore,

e anche se più giovane, la mia debolezza

per disporci in difficoltà senza sforzo.

Saremo opposti prematuramente

varcando il centro

tentando di duplicare lo spazio

ma questo è superfluo:

lui prepara una lunga bracciata

lasciando la sua scia

al largo quasi al punto da soffocarmi

insolito a questo altro ritmo

pone la sua faccia in profondità

e prepara un polmone

percorrendo l’intera lunghezza

Perfino lungo un fianco

apparentemente mio, non posso competere.

Se questa fosse una barca, sarebbe l’estremità.

*

Il Doppio Appuntamento

L’essenziale è invisibile agli occhi.

St-Exupèry, Il Piccolo Principe

Prendendo ciascuno il proprio turno per entrare

questo armadietto oscuro come se fosse

un confessionale, solo gli errori sono

oculari, ordinari e noi speriamo

veniali non mortali; comunque

il computo di questo maestro non esenta

alcun sacramento, soltanto prospettive. E scolpite

immagini: una nuova macchina in grado di scrutare

e penetrare negli occhi, alternandosi

in tre dimensioni – osserva, la mia

macchia come dovrebbe essere, consolante , lui

ti chiama dal panchetto per osservare,

restituito all’intimità: tua moglie in vesti

mai viste prima, non equivoca ma spiritosa,

tracciando il modo in cui noi, così vicini, condividiamo la perdita

di escludere il mondo – una coppia

di vecchie scarpe o pantaloni che si conservano insieme

in declino come tutto il resto – eppure ancora ne faccio tesoro

l’un l’altro e nientemeno. Guarda quella membrana

fluttuante, staccata! Dice lui, staccata, e la tua

domanda balza ansiosa ma nulla

è serio solo il mio vitreo invecchiare

insieme al resto di noi, e adesso per settimane

tu dovrai guidarmi, vai dove

ho bisogno di andare, proprio come farei se fossi tu

questa impotenza, che estende i sensi l’un l’altro,

simbiosi ossea della mia carne,

fino quando il mio nuovo sarà pronto per essere raccolto,

ed io sarò di nuovo praticante, esteriormente

focalizzata, dimostrando di condurre tutto da sola

Tracy Ryan

(le poesie sono tratte dal libro “The Water Bearer”, Fremantle Press, 2018; trad. it. dell’intervista e delle poesie di Matilde Casagrande)

*

Where does your poetic inspiration come from? You are inspired by a fact, an historical event, a natural datum, a sudden lighting… What is poetry?

It can come from absolutely anywhere: out of the sensation that picking up and supporting a heavy microscope resembles picking up and supporting a small baby. Or out of recognising your partner’s tread on the stairs as minutely distinct from anyone else’s footfall. The more I consider it, the more I realise it’s specifically happening through each of the senses; sometimes more than one sense at a time, of course. The spatial realisation that, for instance, after pregnancy, you keep making more room than you need – or missing the weight of the child on your hip, your arm. These things seem trivial but are not, since they entail psychological, social, even spiritual connections. All of it within the context of bouncing off other people’s work – because inspiration comes from other poetry too, run through the sieve (to mix the metaphor!) of your own experiences.

I have read that your poetry has been compared to Sylvia Plath’s poems, a well-known poet in Italy. Do you like this comparison, do you think it’s right? What poets do you love? Which poets — living or dead — have helped your poetic growth?

Like many other poets, I’m deeply indebted to Plath’s work. I don’t think my work resembles hers very much, thematically almost not at all, though in craft and technique she’s a huge model for me. This is not unusual, especially in my generation, since it came directly after hers (she’s of my parents’ era). I’ve been affected by too many poets to mention all, but crucially both Plath and Ted Hughes, as well as Plath’s great influence Theodore Roethke; also the Australians Judith Wright, whom I studied at school, and Dorothy Hewett. From earlier times, I’ve learned from John Donne, George Herbert, then Gerard Manley Hopkins. I return again and again to Emily Dickinson and Emily Brontë. For non-English poets, absolutely Rainer Maria Rilke and probably Baudelaire, despite all the problems with him!

Do you think there is a specificity of ‘feminine’ writing? What is different from that of the ‘males’?

I don’t think the specificity or difference is absolute. I think it can in some cases be detected as a disposition, tendency, or a way of seeing – but nobody falls neatly into one “camp” or the other – gender just isn’t that simple, as people are finally starting to recognise! (Some people always did recognise it.) Having said that, I do think there have been elements that women’s writing has highlighted because of historical difference in experience, sometimes devalued experience. I mean the standards of judgement whereby a particular subject matter was previously considered “trivial” or “personal” because it was more aligned with typically “female” experience. Those categories have been questioned a long time now. I am a feminist, but that doesn’t mean I accept every viewpoint people associate with that word.

What is the relationship, in your opinion, between ethics and aesthetics? When you write you only solve a formal problem or do you also worry about a ‘political’, social, environmental problem?

I think ethics and aesthetics are inseparable, even if we intend to separate them. Even if we don’t quite know when we have drawn on an ethical position. Solving a formal problem is just such a small part of writing, even though sometimes it feels like the hardest part. Worrying about those problems you mention is always there for me, despite sometimes seeming more of a “backdrop” rather than a front-and-centre topic.

I read that you lived in the UK, USA, Australia. What are the characteristics of Australian poetry?

It’s probably too diverse to characterise.

What are you working on now, what book are you writing?

I have a new novel coming out this year and a lot of my energies have gone into that. In the way that actors like to say, euphemistically, they are “between roles”, or “between engagements”, I’m “between books” at the moment!

L'articolo “Scrivere è sollevare un microscopio e accudire un bambino”: dialogo con Tracy Ryan, la Sylvia Plath australiana proviene da Pangea.

from pangea.news https://ift.tt/2LNOYKz

0 notes

Text

Linkspam #2

Top Links

Public Policy After Utopia by Will Wilkinson at the Niskanen Center:

It is intellectually corrupt and corrupting to define liberty or equality or you-name-it in terms of an idealized, counter-factual social system that may or may not do especially well in delivering the goods. Commitment to a vision of the perfect society is more likely than not to lead you astray. Consider how unlikely it is for a typical libertarian to correctly predict more than a couple of the top-ten freest countries on the libertarian freedom index. The fact that ideological radicals are pretty unreliable at ranking existing social systems in terms of their favored values ought to make us skeptical of claims that highly counterfactual systems would rank first. And it ought to lead us to suspect that ideal-theoretical political theorizing leads us to see the actual world less clearly than we might, due to cherry-picking and confirmation bias.

What I Don’t Tell My Students About ‘The Husband Stitch’ by Jane Dykema at Electric Lit:

Reliable information about, or even an official definition of, the husband stitch is conspicuously missing from the internet. No entry in Wikipedia, nothing in WebMD. Instead there are pages and pages of message board entries and forum discussions on pregnancy websites, and a pretty good definition on Urban Dictionary. In James Baldwin’s 1979 New York Times piece, “If Black English Isn’t a Language, Then Tell Me, What Is?” he writes, “People evolve a language in order to describe and thus control their circumstances, or in order not to be submerged by a reality that they cannot articulate.” How can a practice like the husband stitch be warned against if there’s no official discussion of it, no record of it, no language around it, nothing to point at, to teach?

[...] But this is not an essay about the husband stitch. It’s an essay about believing and being believed.

The scientists persuading terrorists to spill their secrets by Ian Leslie at the Guardian:

Implicit in Miller and Rollnick’s critique of traditional counselling was the uncomfortable suggestion that counsellors should turn their professional gaze upon themselves and question their own instinct to dominate. Instead of thinking of himself as an expert sitting in judgment, the counsellor needed to adopt the more humble position of co-investigator. As Miller put it to me, “The premise is not ‘I have you what you need, let me give it to you.’ It’s ‘You have what you need and we’ll find it.’ The patient must feel “autonomous” – the author of their own actions.

Emily Alison, who had trained in MI while working as a counsellor for the probation service in Wisconsin, noticed that interrogations failed or succeeded for similar reasons as therapeutic sessions. Interrogators who made an adversary out of their subject left the room empty-handed; those who made them a partner yielded information. The best ones suspended moral judgment and conveyed genuine curiosity. She concluded that the detainee, like the addict, wants to feel free, despite or rather because of their confinement, and that the interviewer should help them do so.

When Trauma Becomes Dominance: An Interview with Sarah Schulman by Adam Fitzgerald at Lit Hub:

A person who was very hurt can do a tremendous amount of damage in somebody else’s life. If you’re on the receiving end of this—whether it’s coming from someone who is a supremacist or someone who hasn’t processed their own trauma—it can be equally damaging to you. There are dramatic cases of transformation. In 1945, Jews were probably the most oppressed people in the world. By 1948 and the founding of the state of Israel, you see a Jewish nation-state subordinating an entire people, the Palestinians. For some individuals or for some entities, you see a transformation from profound trauma and oppression to an unjust dominance.

Certainly with white gay men, who during the AIDS crisis died in enormous numbers and were treated with gross indifference by the state and by their families, today, if they are middle class or above, in many cases enjoy the privilege of the whiteness. And in Europe we’re seeing, for example, more white gay men moving towards the right and voting for right-wing parties. So that’s another example of being transformed into an oppressive entity.

On the Table, the Brain Appeared Normal by John Branch at the New York Times:

The brain arrived in April, delivered to the basement of the hospital without ceremony, like all the others. There were a few differences with this one — not because it was more important, but because it was more notorious.

Third-Party Party-Crashing? The Fate of the Third-Party Doctrine by Michael Bahar, David Cook, Varun Shingari and Curtis Arnold at Lawfare:

This fall may prove a landmark in the ongoing debate between security and privacy. Poised to take action are both the U.S. Supreme Court, in Carpenter v. United States, and the U.S. Congress, with the impending sunset of Section 702 of the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act (FISA). Decisions made—or not made—this autumn will have ripple effects in the United States and around the globe.

This post explains the dynamics of the Supreme Court’s upcoming decision in Carpenter, and how it could impact this and other important surveillance authorities. It then discusses the implications of Carpenter to the emerging global privacy regime, and the conflicts of law that may ensue.

Something is wrong on the internet by James Bridle at Medium:

Someone or something or some combination of people and things is using YouTube to systematically frighten, traumatise, and abuse children, automatically and at scale, and it forces me to question my own beliefs about the internet, at every level.

Other Favorites

We Warned You About Milo and You’re Still Not Listening by Katherine Cross at the Establishment - on the willingness of centrists to redeem Milo Yiannopoulos

The rules about responding to call outs aren’t working by Ruti Regan at RealSocialSkills.org

Avengers in Wrath: Moral Agency and Trauma Prevention for Remote Warriors by Dave Blair and Karen House at Lawfare - a deep dive into the psychology and morality of drone warfare

Heroku’s Ugly Secret by James Somers at Rap Genius - how a change in routing algorithms blew up in Heroku’s face thanks to poor documentation

The Complexities of Trans Gerudo Town by Laura Dale at Let’s Play Video Games - on gender in Zelda: Breath of the Wild

California Police and Civil Liberties Groups Agreed on a Simple Transparency Measure. Gov. Brown Vetoed It Anyway. by Dave Maass at the Electronic Frontier Foundation

For George Washington, #BringBackOurGirls meant something very different by Fred Clark at Patheos - on George Washington’s attempts to re-enslave Oney Judge

My Path To Becoming A Third Parent by David Jay at the Establishment - building a different kind of family

Christopher Wray and the Myth Created by Parallel Construction by Marcy Wheeler at Emptywheel - discussion of FISA Section 702, which allows warrantless surveillance of US citizens, and FBI Directory Christopher Wray’s defense of it

The Cost of White Comfort by Chenjerai Kumanyika at HiLoBrow - who gets comforted after racial harms

2 Broke Lab Rats: Human Research Subjects in Film and Television by Marci Cottingham at Sociological Images

In Praise of Theory in Design Research: How Levi-Strauss Redefined Workflow by Bill Selman and Gemma Petrie at EPIC - how Levi-Strauss’s theory of the bricoleur helped redefine Mozilla’s approach to user experience

It’s a Fact: Supreme Court Errors Aren’t Hard to Find by Ryan Gabrielson at ProPublica

Factory science by Martin Schmidt, Benedikt Fecher and Christian Kobsda at Elephant in the Lab - on the meaning of authorship in the digital age

You Can’t Understand Anti-Queer Violence In Jamaica Until You Understand Colonialism by Shanna Collins at Medium

Was Emily Brontё’s Heathcliff black? by Corinne Fowler at the Conversation

On Minimization as a Patriarchal Reflex by Matthew Remski at their personal website

AI Model Fundamentally Cracks CAPTCHAs, Scientists Say by Merrit Kennedy at NPR

Interpreting Harriet Tubman’s Life on a Silent Landscape by Anne Kyle at the Preservation Leadership Forum - on creating the Harriet Tubman Underground Railroad Byway (this was of special interest to me as I visited it this past summer)

Causal inference and random trials by Daniel Little at Understanding Society - how much can we learn from random control trials?

Sorry Facebook, Blasphemy Is Not Apolitical by Sarah McLaughlin at Popehat

UI design as if users actually mattered: backwards compatibility by Dan Luu at their personal website

0 notes

Text

Weather-related expressions in translating “Wuthering Heights” into Polish - Ludwika Kazimierska

1. Introduction

In the present contribution, we illustrate some of the practical problems that translators encounter while giving Polish equivalents of selected weather descriptions as found in Emily Brontё’s Wuthering Heights.

2. The data

Our data includes 11 original weather-related expressions and their translations in Polish provided by two different translators. These translations were published in the same year (2013). Our choice is Hanna Pasierska’s rendering, published in 2013 by Prószyński and S-ka, referred to as Polish 1, and Tomasz Bieroń’s rendering, published in 2013 by SIW Znak, referred to as Polish 2.

Our examples are presented in Table 1 (see below).

As we can see, some of Emily Brontё’s expressions seem to be embarrassing for the Polish translators in the sense that their respective visualizations are different, giving different Polish equivalents. In our analysis below, we present and discuss only 2 typical cases.

3. Contextual examination of selected phrases from Wuthering Heights

The main purpose here is to examine the selected phrases or words from Wuthering Heights by taking into consideration cultural context as well as translation techniques.

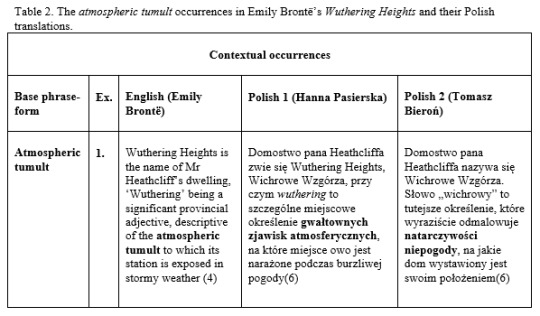

3.1 Case Study 1: atmospheric tumult

As evidenced in Table 2, the translators do not agree with each other. Also, it must be noted that Hanna Pasierska’s translation is closer to the English original.

As we can see in Table 2, neither of the two Polish translators gives the same equivalent to the original text. Pasierska’s translation includes: gwałtowne zjawiska atmosferyczne, while Bieroń uses: natarczywości niepogody. It is interesting to see the practical side of these cases. In the next part, we summarize the situational context, which is the very situation in which the expression is used. Then, we do some EFL dictionary search as to the possible meaning(s) of atmospheric tumult. Lastly, we refer to the quality of the Polish translations, referring them to the situational context and to the Polish dictionary definitions.

Situational context. The discussed expression appears when the narrator describes the property of Mr. Heathcliff. The mansion is located on a hill that is exposed to the harsh weather conditions - especially during the storms when the gusty winds blow. Nature around the house also indicates the strength of the winds in the area. The narrator describes a few stunted firs and a weak brier. Next, the architecture of the house is described. The building has the narrow windows that are framed deep in the walls and in the corners of the protruding stones - these measures are meant to protect the house from the winds. The facade is decorated with grotesque carvings. The author also describes the interior of Mr. Heathcliff’s estate and his customs. This is not a typical Yorkshire house from the eighteenth century.

Atmospheric tumult: dictionaries definition[1]. When we compare the Polish translations, tumult seems to be the key word. It is of utmost importance here. Moreover, in any of the presented dictionary definitions it does not apply to weather conditions. The results of our research are presented in Table 3.

[1] online editions of the following EFL dictionaries: Longman, Cambridge, Macmillan, Oxford

The primary meaning of the word tumult is the noise caused by the large number of people staying in the same place. This noise can be caused by many factors, such as loud noise caused by a large group of excited people. There is an important reason for this noise, important because it is caused by a large group of people. Tumult also means a mental state.

Our sources give examples of sentences with tumult. For example, in Longman, we can find this:

I could simply not be heard in the tumult.

The whole country is in tumult.[1]

In the first example, tumult is related to a lot of loud noise made by a crowd of people. The second one indicates the mental state of a large group of people - all over the country. In this context, the whole country is in chaos as the result of the assassination attempt.

Cambridge shows an example of the word tumult in relation to the financial meltdown in the stock market:

The financial markets are in tumult.[2]

The oxford online dictionary has got this:

The play ends in a tumult of sounds, the woman's screams and the man's pleadings with the doctor to ‘send help immediately’ being drowned by music and the screams of an ambulance siren.

Hundreds of other families were also separated in the tumult.

his personal tumult ended when he began writing songs

The poetry of great minds has grown and been nurtured in the midst of life's mystic tumult and disorder.

Despite all tumult and turbulence, one after all, had to carry on.

Public tumults and tragedies gradually recede into the past and become less emotionally fraught for all of us.[3]

In the first sentence, tumult occurs in the context of the noise caused by people. In another example, the use of the noun is connected with a crowd of people or their confusion rather than with the noise caused by them. In the context of the third sentence, we notice the emotional state of the people, namely an anxious spirit. In the fourth embodiment, tumult means a mess caused by inappropriate behavior of people. Last but not least, it is a state of confusion or disorder.

Translation effect. In order to evaluate the translation effect, let us do a dictionary search in relation to the Polish equivalents provided by the translators (see Table 4).[4]

[1] http://www.ldoceonline.com/dictionary/tumult

[2] http://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english/tumult

[3] http://www.oxforddictionaries.com/definition/english/tumult

[4] In this and the other cases, our Polish data come from the online editions of Wielki słownik języka polskiego and Słownik języka polskiego.

As we can see, in the table presented above, we have no reference to any weather conditions, whereas the adjective atmospheric appears to give the word tumult such a weather-related meaning. Thanks to the translators, it refers to the prevailing weather. Considering the above table and the situational context, we can conclude that gwałtowny, with its definition from SJP, namely: ,,mający znaczne natężenie; nagły i szybki” (Eng. “having significant intensity; sudden and fast”), is better suited to the above-mentioned in the context of the situation than the other version, i.e. natarczywy. In the present case, we are actually talking about the violence of the weather conditions.

General assessment. In this example, considering all the above EFL dictionaries, the definition of tumult refers to the noise caused by a crowd of people. In none of the given definitions, there is any reference to the weather conditions, but the definition of tumult in Longman dictionary, that is “a confused, noisy, excited, and situation, often caused by a large crowd; a state of mental confusion caused by strong emotions such as anger, sadness, etc.” illustrates best the described situation. However, we can say that Hanna Pasierska's translation is better than Tomasz Bieroń's one, because her gwałtowny refers more properly to the atmospheric conditions than the one used by Bieroń - natarczywy.

3.2 Case Study 2: blustered

Another interesting translation effect, which is a part of this study, is how Polish interpreters refer to the expression blustered. All the translations are presented in the following table (Table 5). Again, the translators do not agree with each other in this case.

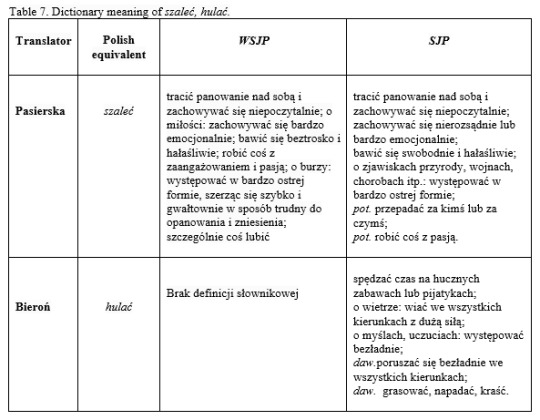

As we can see in Table 5, the two Polish translators gave different equivalents to the original text. Pasierska provides: szalał, while Bieroń uses: hulał. Now, we will focus on the practical side of these cases.

Situational context. The situation occurs when Ellen (Nelly) Dean - the main narrator of the novel, tells the story of the death of Mr. Earnshaw. It happened in one October evening. The weather outside was unpleasant - “A high wind blustered round the house, and roared in the chimney...”[1]. Mr. Earnshaw was sitting in an armchair by the fireside with his children and servants. His daughter sat with him and they talked. She had to sing a song to lull his father to sleep. Everyone thought that Mr. Earnshaw fell asleep, but when Joseph wanted to wake his master up for an evening prayer, it became clear that he had died.

bluster: dictionaries definition[2]. The results of dictionary search are presented in Table 6.

[1] Emily Brontё Wuthering Heights, page 49

[2] online editions of the following EFL dictionaries: Longman, Cambridge, Macmillan, Oxford

The most general meaning of bluster is connected with a specific kind of speech. No matter what the reason of the speech is, it must be threatening and uttered with anger. However, the word bluster refers also to the gusty, sudden wind, or torrential rain.

Our sources give convincing illustrative sentences. For example, in Longman, we can find this:

'That's hardly the point,' he blustered.

blustering wintry weather[1]

In the first example, blustered refers to expressing one’s attitude in an angry or threatening way, while the second example, which relates to the discussed translations, describes weather conditions and stands for the penetrating wintry weather.

In contrast, Cambridge dictionary unfortunately does not show any examples of sentences using bluster. Yet, there is one in Macmillan:

His response was first to persuade, then to bluster.[2]

In the above example, bluster was used again in the context of the conversation and the outbreak of anger caused by failed attempts to persuade someone to your point of view.

Lastly, we analyze examples provided by oxford dictionary:

you threaten and bluster, but won’t carry it through

‘I don’t care what he says,’ I blustered

a winter gale blustered against the sides of the house

the blustering wind[3]

The first two examples refer to talking in a loud, aggressive, or indignant way with little effect. The next two sentences describe weather conditions, where bluster blows or beats fiercely and noisily. In the last example, bluster is used as an adjective, translated as wściekły, gwałtowny.

Considering all the above examples, we can conclude that the word bluster has many meanings and its meaning can change depending on the context in which it is used. Then, we would like to take advantage of all EFL dictionary definitions, use examples given by them as well as make use of definitions from Polish dictionaries to determine which Polish translator made a better choice in terms of the given context and discuss their choices thoroughly.

Translation effect. In order to evaluate the translation effect, let us do a dictionary search in relation to the Polish equivalents provided by the translators (see Table 7).[4]

[1] http://www.ldoceonline.com/dictionary/bluster

[2] http://www.macmillandictionary.com/dictionary/british/bluster

[3] http://www.oxforddictionaries.com/definition/english/bluster?q=blustered

[4] In this and the other cases, our Polish data come from the online editions of Wielki słownik jezyka polskiego and Słownik jezyka polskiego.

Considering the above table and the situational context, we can say that the rage, with its definition from WSJP, namely: ,,o burzy: występować w bardzo ostrej formie, szerząc się szybko i gwałtownie w sposób trudny do opanowania i zniesienia” (Eng. “about the storm: to be in very sharp form, spreading quickly and violently in a way difficult to control and bear”), is better suited to the above-mentioned than hulać, taking the situational context into consideration.

General assessment. In the discussed example, in all the above EFL dictionaries, the definition of blustered refers mainly to the expression of somebody’s opinion in a violent way and to the threat other people who are not convinced of the virtue of the speaking one. However, the definition of blustered in Longman dictionary, that is “if the wind blusters, it blows violently,” illustrates best the described situation. And again, we can conclude that Hanna Pasierska’s translation is better than Tomasz Bieroń’s one, because her szaleć is more akin to the described situation than hulać (used by Bieroń).

4. Summary and conclusion

Two weather-related expressions from different parts of Emily Bronte’s Wuthering Heights are examined for both accuracy and translation effect. In each case, we discuss the situational context and offer a brief dictionary search. We use the online editions of the following EFL dictionaries: Longman, Cambridge, Oxford, and Macmillan. In order to evaluate the translation effect, a dictionary search is conducted in relation to the Polish equivalents provided by the translators. In this respect, the online editions of Wielki słownik języka polskiego and Słownik języka polskiego are used.

References

Brontë, E. Wuthering Heights. 1847. PDF version available at: http://www.planetpublish.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/11/Wuthering_Heights_T.pdf (Accessed April 15, 2016)

http://www.ldoceonline.com/dictionary/

http://www.macmillandictionary.com/dictionary/british/

http://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english-polish/

http://www.oxforddictionaries.com/definition/english/

http://wsjp.pl/index.php?pwh=0

http://sjp.pwn.pl/

Opieka merytoryczna: dr hab. Przemysław Łozowski, prof. nadzw. UTH, Radom

0 notes

Quote

You said I killed you - haunt me then! ... Be with me always - take any form - drive me mad!

Wuthering Heights, Emily Brontё

13 notes

·

View notes

Quote

[...]; and my mind is so eternally secluded in itself, it is tempting at last to turn it out to another.

Emily Brontё, from ‘Wuthering Heights’ (1847)

3 notes

·

View notes

Quote

I cannot express it; but surely you and everybody have a notion that there is or should be an existence of yours beyond you. What were the use of my creation, if I were entirely contained here?

Emily Brontё, from ‘Wuthering Heights’ (1847)

17 notes

·

View notes

Quote

They remind me of soft thaw winds, and warm sunshine, and nearly melted snow.

Emily Brontё, from ‘Wuthering Heights’ (1847)

9 notes

·

View notes

Quote

You are so much happier than I am, you ought to be better.

Emily Brontё, from ‘Wuthering Heights’ (1847)

3 notes

·

View notes