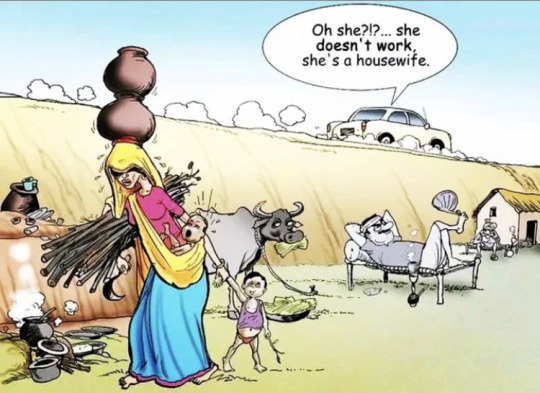

#domestic labor

Text

Truck comes first and if there is any money left over the kids may eat. - Modern Consumer Patriarchy

#heterorealism#gender equality#men ain't shit#divorce him#feminism#wages for housework#domestic labor#working class women#blue collar women#fuck the patriarchy

38K notes

·

View notes

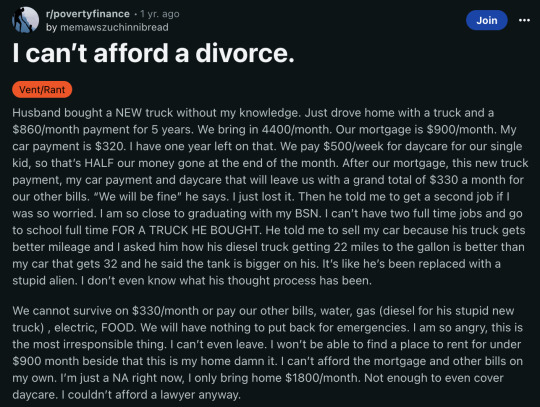

Text

I'm a disabled trans guy who is unemployed, and I don't bring any income to my household. I love to cook, clean, organize, manage calendars, appointments, etc. so in my polycule, that's the role I fill.

I'm a homemaker and very proud of it, but I wish I could say that with more frequency without constantly having people roll their eyes or interrogating me about my personal life.

"How can you be too disabled to work a job, but not to take care of your household? Don't the other people in your family do any housework? Are you being taken advantage of? Have you ever had a job? Can't you work part time? Why aren't you on disability? Have you tried a work from home job?"

I've been trying to find more support and community for people like me, but the sheer wall of red usernames that appear when I dip into any kind of "homemaker", "housekeeping", "domestic labor", type of tag is absolutely terrifying. It's either tradwives or radfems, with no in-between. "stay at home dad" tags are basically empty, and i don't even have a kid living at home with me anymore to bond with other parents anyway.

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

Whether in your personal home or in your workplace, domestic and hospitality labor is labor!

[Image description: A square graphic with red text that reads, "Domestic labor is real labor whether in the workplace or the home." Below the text is an illustration of four different people performing domestic tasks such as trash pickup and sweeping. More text below the illustration reads, "Industrial Workers of the World. Find your local branch. IWW.org/join." The IWW logo is included in the bottom right of the image. End description.]

947 notes

·

View notes

Text

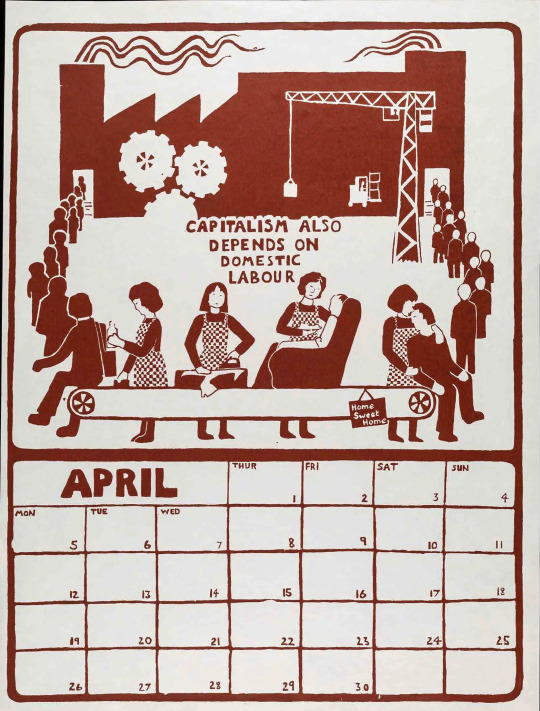

"A feminist silkscreen poster collective founded in London in 1974 by three former art students, the See Red Women’s Workshop grew out of a shared desire to combat sexist images of women and to create positive and challenging alternatives. Women from different backgrounds came together to make posters and calendars that tackled issues of sexuality, identity and oppression. With humor and bold, colorful graphics, See Red expressed the personal experiences of women as well as their role in wider struggles for change."

Red Women’s Workshop, 1975

369 notes

·

View notes

Text

Marilyn French, The Women's Room (1977)

#marilyn french#the women's room#feminism#literature#feminist literature#second wave feminism#women's domestic labour#domestic labor

123 notes

·

View notes

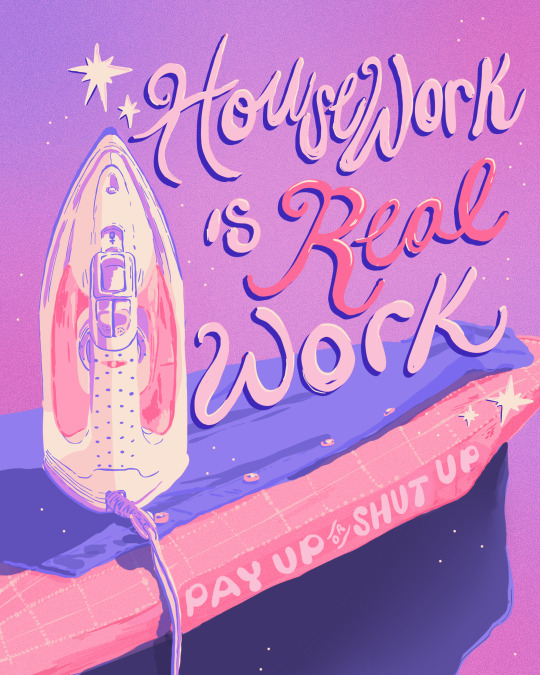

Text

Housework is real work. Pay up or shut up.

Colorful image that reads, 'housework is real work' with an iron, ironing board and button-up shirt. The bottom text reads, 'pay up or shut up.'

#art#feminism#feminist#housework#domestic labor#labor rights#women's rights#gender pay gap#gender inequality

956 notes

·

View notes

Text

Its not men not being taught how to do things, its that men are taught to imagine a future where someone will do those things for them so they don't feel they have to figure it out on their own

#or at least a future where you will have someone who already knows those things so youll have someone to fill in the gaps of the things#of the things you didnt /have to/ learn youself#domestic labor#weaponized incompetence

277 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Relentless Toil: A Reading List About Filipino Laborers

“What happens when the only way to ensure the survival of the people you love the most is to leave them behind?” Amy DePaul compiles a reading list on the enormous sacrifices of Filipino laborers at home and abroad.

A strong sense of family duty. Incredible kindness and generosity. Pride. “Such sought-after traits have been a blessing and a curse,” writes Amy DePaul, “giving Filipinas access to the lives of elite families in cities like Hong Kong, Dubai, and New York City, but also subjecting them to highly exploitative and even dangerous situations.” In this new reading list, DePaul recommends five powerful stories on the sacrifices of Filipino laborers, both at home and overseas.

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

Women and the Subversion of the Community

…

THE ORIGINS OF THE CAPITALIST FAMILY

In pre-capitalist patriarchal society the home and the family were central to agricultural and artisan production. With the advent of capitalism the socialization of production was organized with the factory as its center. Those who worked in the new productive center, the factory, received a wage. Those who were excluded did not. Women, children and the aged lost the relative power that derived from the family’s dependence on their labor, which was seen to be social and necessary. Capital, destroying the family and the community and production as one whole, on the one hand has concentrated basic social production in the factory and the office, and on the other has in essence detached the man from the family and turned him into a wage laborer. It has put on the man’s shoulders the burden of financial responsibility for women, children, the old and the ill, in a word, all those who do not receive wages. From that moment began the expulsion from the home of all those who did not procreate and service those who worked for wages. The first to be excluded from the home, after men, were children; they sent children to school. The family ceased to be not only the productive, but also the educational center.[2]

To the extent that men had been the despotic heads of the patriarchal family, based on a strict division of labor, the experience of women, children and men was a contradictory experience which we inherit. But in pre-capitalist society the work of each member of the community of serfs was seen to be directed to a purpose: either to the prosperity of the feudal lord or to our survival. To this extent the whole community of serfs was compelled to be co-operative in a unity of unfreedom that involved to the same degree women, children and men, which capitalism had to break.[3] In this sense the unfree individual, the democracy of unfreedom,[4] entered into a crisis. The passage from serfdom to free labor power separated the male from the female proletarian and both of them from their children. The unfree patriarch was transformed into the “free” wage earner, and upon the contradictory experience of the sexes and the generations was built a more profound estrangement and therefore a more subversive relation.

We must stress that this separation of children from adults is essential to an understanding of the full significance of the separation of women from men, to grasp fully how the organization of the struggle on the part of the women’s movement, even when it takes the form of a violent rejection of any possibility of relations with men, can only aim to overcome the separation which is based on the “freedom” of wage labor.

THE CLASS STRUGGLE IN EDUCATION

The analysis of the school which has emerged during recent years—particularly with the advent of the students’ movement—has clearly identified the school as a center of ideological discipline and of the shaping of the labor force and its masters. What has perhaps never emerged, or at least not in its profundity, is precisely what precedes all this; and that is the usual desperation of children on their first day of nursery school, when they see themselves dumped into a class and their parents suddenly desert them. But it is precisely at this point that the whole story of school begins.[5]

Seen in this way, the elementary school children are not those appendages who, merely by the demands “free lunches, free fares, free books,” learnt from the older ones, can in some way be united with the students of the higher schools.[6] In elementary school children, in those who are the sons and daughters of workers, there is always an awareness that school is in some way setting them against their parents and their peers, and consequently there is an instinctive resistance to studying and to being “educated.” This is the resistance for which Black children are confined to educationally subnormal schools in Britain.[7] The European working class child, like the Black working class child, sees in the teacher somebody who is teaching him or her something against her mother and father, not as a defense of the child but as an attack on the class. Capitalism is the first productive system where the children of the exploited are disciplined and educated in institutions organized and controlled by the ruling class.[8]

The final proof that this alien indoctrination which begins in nursery school is based on the splitting of the family is that those working class children who arrive (those few who do arrive) at university are so brainwashed that they are unable any longer to talk to their community.

Working class children then are the first who instinctively rebel against schools and the education provided in schools. But their parents carry them to schools and confine them to schools because they are concerned that their children should “have an education,” that is, be equipped to escape the assembly line or the kitchen to which they, the parents, are confined. If a working class child shows particular aptitudes, the whole family immediately concentrates on this child, gives him the best conditions, often sacrificing the others, hoping and gambling that he will carry them all out of the working class. This in effect becomes the way capital moves through the aspirations of the parents to enlist their help in disciplining fresh labor power.

In Italy parents less and less succeed in sending their children to school. Children’s resistance to school is always increasing even when this resistance is not yet organized.

At the same time that the resistance of children grows to being educated in schools, so does their refusal to accept the definition that capital has given of their age. Children want everything they see; they do not yet understand that in order to have things one must pay for them, and in order to pay for them one must have a wage, and therefore one must also be an adult. No wonder it is not easy to explain to children why they cannot have what television has told them they cannot live without.

But something is happening among the new generation of children and youth which is making it steadily more difficult to explain to them the arbitrary point at which they reach adulthood. Rather the younger generation is demonstrating their age to us: in the sixties six-year-olds have already come up against police dogs in the South of the United States. Today we find the same phenomenon in Southern Italy and Northern Ireland, where children have been as active in the revolt as adults. When children (and women) are recognized as integral to history, no doubt other examples will come to light of very young people’s participation (and of women’s) in revolutionary struggles. What is new is the autonomy of their participation in spite of and because of their exclusion from direct production. In the factories youth refuse the leadership of older workers, and in the revolts in the cities they are the diamond point. In the metropolis generations of the nuclear family have produced youth and student movements that have initiated the process of shaking the framework of constituted power: in the Third World the unemployed youth are often in the streets before the working class organized in trade unions.

It is worth recording what The Times of London (1 June 1971) reported concerning a headteachers’ meeting called because one of them was admonished for hitting a pupil: “Disruptive and irresponsible elements lurk around every corner with the seemingly planned intention of eroding all forces of authority.” This “is a plot to destroy the values on which our civilization is built and on which our schools are some of the finest bastions.”

THE EXPLOITATION OF THE WAGELESS

We wanted to make these few comments on the attitude of revolt that is steadily spreading among children and youth, especially from the working class and particularly Black people, because we believe this to be intimately connected with the explosion of the women’s movement and something which the Women’s movement itself must take into account. We are dealing with the revolt of those who have been excluded, who have been separated by the system of production, and who express in action their need to destroy the forces that stand in the way of their social existence, but who this time are coming together as individuals.

Women and children have been excluded. The revolt of the one against exploitation through exclusion is an index of the revolt of the other.

To the extent to which capital has recruited the man and turned him into a wage laborer, it has created a fracture between him and all the other proletarians without a wage who, not participating directly in social production, were thus presumed incapable of being the subjects of social revolt.

Since Marx, it has been clear that capital rules and develops through the wage, that is, that the foundation of capitalist society was the wage laborer and his or her direct exploitation. What has been neither clear nor assumed by the organizations of the working class movement is that precisely through the wage has the exploitation of the non-wage laborer been organized. This exploitation has been even more effective because the lack of a wage hid it. That is, the wage commanded a larger amount of labor than appeared in factory bargaining. Where women are concerned, their labor appears to be a personal service outside of capital. The woman seemed only to be suffering from male chauvinism, being pushed around because capitalism meant general “injustice” and “bad and unreasonable behavior”; the few (men) who noticed convinced us that this was “oppression” but not exploitation. But “oppression” hid another and more pervasive aspect of capitalist society. Capital excluded children from the home and sent them to school not only because they are in the way of others’ more “productive” labor or only to indoctrinate them. The rule of capital through the wage compels every ablebodied person to function, under the law of division of labor, and to function in ways that are if not immediately, then ultimately profitable to the expansion and extension of the rule of capital. That, fundamentally, is the meaning of school. Where children are concerned, their labor appears to be learning for their own benefit.

Proletarian children have been forced to undergo the same education in the schools: this is capitalist levelling against the infinite possibilities of learning. Woman on the other hand has been isolated in the home, forced to carry out work that is considered unskilled, the work of giving birth to, raising, disciplining, and servicing the worker for production. Her role in the cycle of social production remained invisible because only the product of her labor, the laborer, was visible there. She herself was thereby trapped within pre-capitalist working conditions and never paid a wage.

And when we say “pre-capitalist working conditions” we do not refer only to women who have to use brooms to sweep. Even the best equipped American kitchens do not reflect the present level of technological development; at most they reflect the technology of the 19th century. If you are not paid by the hour, within certain limits, nobody cares how long it takes you to do your work.

This is not only a quantitative but a qualitative difference from other work, and it stems precisely from the kind of commodity that this work is destined to produce. Within the capitalist system generally, the productivity of labor doesn’t increase Unless there is a confrontation between capital and class: technological innovations and co-operation are at the same time moments of attack for the working class and moments of capitalistic response. But if this is true for the production of commodities generally, this has not been true for the production of that special kind of commodity, labor power. If technological innovation can lower the limit of necessary work, and if the working class struggle in industry can use that innovation for gaining free hours, the same cannot be said of housework; to the extent that she must in isolation procreate, raise and be responsible for children, a high mechanization of domestic chores doesn’t free any time for the woman. She is always on duty, for the machine doesn’t exist that makes and minds children.[9] A higher productivity of domestic work through mechanization, then, can be related only to specific services, for example, cooking, washing, cleaning. Her workday is unending not because she has no machines, but because she is isolated.[10]

CONFIRMING THE MYTH OF FEMALE INCAPACITY

With the advent of the capitalist mode of production, then, women were relegated to a condition of isolation, enclosed within the family cell, dependent in every aspect on men. The new autonomy of the free wage slave was denied her, and she remained in a pre-capitalist stage of personal dependence, but this time more brutalized because in contrast to the large-scale highly socialized production which now prevails. Woman’s apparent incapacity to do certain things, to understand certain things, originated in her history, which is a history very similar in certain respects to that of “backward” children in special ESN classes. To the extent that women were cut off from direct socialized production and isolated in the home, all possibilities of social life outside the neighborhood were denied them, and hence they were deprived of social knowledge and social education. When women are deprived of wide experience of organizing and planning collectively industrial and other mass struggles, they are denied a basic source of education, the experience of social revolt. And this experience is primarily the experience of learning your own capacities, that is, your power, and the capacities, the power, of your class. Thus the isolation from which women have suffered has confirmed to society and to themselves the myth of female incapacity.

It is this myth which has hidden, firstly, that to the degree that the working class has been able to organize mass struggles in the community, rent strikes, struggles against inflation generally, the basis has always been the unceasing informal organization of women there; secondly, that in struggles in the cycle of direct production women’s support and organization, formal and informal, has been decisive. At critical moments this unceasing network of women surfaces and develops through the talents, energies and strength of the “incapable female.” But the myth does not die. Where women could together with men claim the victory—to survive (during unemployment) or to survive and win (during strikes)—the spoils of the victor belonged to the class “in general.” Women rarely if ever got anything specifically for themselves; rarely if ever did the struggle have as an objective in any way altering the power structure of the home and its relation to the factory. Strike or unemployment, a woman’s work is never done.

…

[2] This is to assume a whole new meaning for “education,” and the work now being done on the history of compulsory education—forced learning—proves this. In England teachers were conceived of as “moral police” who could 1) condition children against “crime”—curb working class reappropriation in the community; 2) destroy “the mob,” working class organization based on family which was still either a productive unit or at least a viable organizational unit; 3) make habitual regular attendance and good timekeeping so necessary to children’s later employment; and 4) stratify the class by grading and selection. As with the family itself, the transition to this new form of mini control was not smooth and direct, and was the result of contradictory forces both within the class and within capital, as with every phase of the history of capitalism.

[3] Wage labor is based on the subordination of all relationships to the wage relation. The worker must enter as an “individual” into a contract with capital stripped of the protection of kinships.

[4] Karl Marx, “Critique of Hegel’s Philosophy of the State,” Writings of the Young Marx on Philosophy and Society, ed. and trans. Lloyd D. Easton and Kurt H. Guddat, N.Y., 1967, p.176.

[5] We are not dealing here with the narrowness of the nuclear family that prevents children from having an easy transition to forming relations with other people; nor with what follows from this, the argument of psychologists that proper conditioning would have avoided such a crisis. We are dealing with the entire organization of the society, of which family, school and factory are each one ghettoized compartment. So every kind of passage from one to another of these compartments is a painful passage. The pain cannot be eliminated by tinkering with the relations between one ghetto and another but only by the destruction of every ghetto.

[6] “Free fares, free lunches, free books” was one of the slogans of a section of the Italian students movement which aimed to connect the struggle of younger students with workers and university students.

[7] In Britain and the US the psychologists Eysenck and Jensen, who are convinced “scientifically” that Blacks have a lower “intelligence” than whites, and the progressive educators like Ivan Illyich seem diametrically opposed. What they aim to achieve links them. They are divided by method. In any case the psychologists are not more racist than the rest, only more direct. “Intelligence” is the ability to assume your enemy’s case as wisdom and to shape your own logic on the basis of this. Where the whole society operates institutionally on the assumption of white racial superiority, these psychologists propose more conscious and thorough “conditioning” so that children who do not learn to read do not learn instead to make molotov cocktails. A sensible view with which Illyich, who is concerned with the “underachievement” of children (that is, rejection by them of “intelligence”), can agree.

[8] In spite of the fact that capital manages the schools, control is never given once and for all. The working class continually and increasingly challenges the contents and refuses the costs of capitalist schooling. The response of the capitalist system is to re-establish its own control, and this control tends to be more and more regimented on factory-like lines.

The new policies on education which are being hammered out even as we write, however, are more complex than this. We can only indicate here the impetus for these new policies: (a) Working class youth reject that education prepares them for anything but a factory, even if they will wear white collars there and use typewriters and drawing boards instead of riveting machines. (b) Middle class youth reject the role of mediator between the classes and the repressed personality this mediating role demands. (c) A new labor power more wage and status differentiated is called for. The present egalitarian trend must be reversed. (d) A new type of labor process may be created which will attempt to interest the worker in “participating” instead of refusing the monotony and fragmentation of the present assembly line.

If the traditional “road to success” and even “success” itself are rejected by the young, new goals will have to be found to which they can aspire, that is, for which they will go to school and go to work. New “experiments” in “free” education, where the children are encouraged to participate in planning their own education and there is greater democracy between teacher and taught are springing up daily. It is an illusion to believe that this is a defeat for capital any more than regimentation will be a victory. For in the creation of a labor power more creatively manipulated, capital will not in the process lose 0.1% of profit. “As a matter of fact,” they are in effect saying, “you can be far more efficient for us if you take your own road, so long as it is through our territory.” In some parts of the factory and in the social factory, capital’s slogan will increasingly be “Liberty and fraternity to guarantee and even extend equality.”

[9] We are not at all ignoring the attempts at this moment to make test-tube babies. But today such mechanisms belong completely to capitalist science and control. The use would be completely against us and against the class. It is not in our interest to abdicate procreation, to consign it to the hands of the enemy. It is in our interest to conquer the freedom to procreate for which we will pay neither the price of the wage nor the price of social exclusion.

[10] To the extent that not technological innovation but only “human care” can raise children, the effective liberation from domestic work time, the qualitative change of domestic work, can derive only from a movement of women, from a struggle of women: the more the movement grows, the less men—and first of all political militants—can count on female baby minding. And at the same time the new social ambiance that the movement constructs offers to children social space, with both men and women, that has nothing to do with the day care centers organized by the State. These are already victories of struggle. Precisely because they are the results of a movement that is by its nature a struggle, they do not aim to substitute any kind of co-operation for the struggle itself.

#repost of someone else’s content#Mariarosa Dalla Costa#Selma James#theory#capitalism#patriarchy#domestic labor#misogyny#antiblackness#ageism#adultism#adult supremacy#school#schooling#anti school#school abolition#youthlib#youth liberation#feminism#socialism#communism#leftism#leftist

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Domestic workers throughout the country are pushing for better working conditions, staging rallies and protests and lobbying for labor protections.

The workers, including nannies, house cleaners and home care workers, have launched campaigns in places including Miami, where two organizations led a mid-June march calling for a “Domestic Workers’ Bill of Rights.”

90 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hartley’s book doesn’t just identify emotional labor as a set of tasks that disproportionately fall to women. She dives deep into why emotional labor is so important, and for many, so central to their identities as mothers, wives, sisters, and friends. What she finds is that the act of thinking about the needs of others, the work of care, is as profoundly gratifying as it is exhausting. She contends that teaching adult men to be better partners in this way is a net good for everyone. “They may, with time and practice, find the value in it as it opens a new side of the world to them, a new human wholeness that can help them feel more connected to their lives,” she writes. Getting boys into the kitchen could be a step toward teaching them to value taking care of others as adults—one lovingly prepared dinner at a time.

Can confirm, once I got back into food service I became significantly more invested in making more meals that covered every group of the food pyrmaid and were more elaborate than my frozen meals. I wouldn't say I'm a perfect cook or anything but helping out in the kitchen for a living has changed my perspective on domestic labor as well.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

people on this site regularly talk about domestic labor in a way that reads shockingly similar to the way radfems talk about sex work, and it seems like everyone here has just decided that’s ok for some reason

like “it’s bad to force a woman to be a housewife and sometimes being a housewife can lead to abusive/exploitative situations; therefore no one should ever be a housewife/stay at home parent/etc EVER or else they are dumb and don’t understand feminism”

is shockingly similar to terfs saying that because forced sex work is bad and sometimes sex workers are abused/exploited, therefore no one should ever be a sex worker or else they are dumb and don’t understand feminism

like… you’re all just cool with recycled terf rhetoric being barfed up ad nauseum during every single discussion of domestic labor??

5 notes

·

View notes

Link

32 notes

·

View notes

Quote

Back in the day, physicians had to go through filing cabinets to find records and write notes and prescriptions by hand. Back in the day, office clerks had to run around the office with paper reports to track down their bosses for their approval. Back in the day, farmers planted by hand and harvested with sickles. What do these people have to whine about these days? No one is insensitive enough to say that. Every field has its technological advances and evolves in the direction that reduces the amount of physical labor required, but people are particularly reluctant to admit that the same is true for domestic labor. Since she became a full-time housewife, she often noticed that there was a polarized attitude regarding domestic labor. Some demeaned it as “bumming around at home,” while others glorified it as “work that sustains life,” but none tried to calculate its monetary value. Probably because the moment you put a price on something, someone has to pay.

Cho Nam-Joo, Kim Jiyoung, Born 1982

4 notes

·

View notes