#countercultures 1969-1989

Text

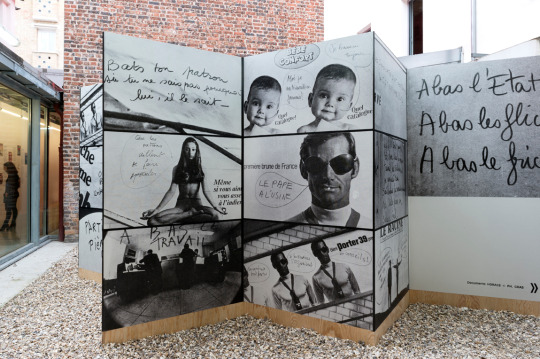

PARIS, April 2017 — Before filter bubbles, there were countercultures: self-selecting groups that did not give a shit about what other people liked or wanted. [...]

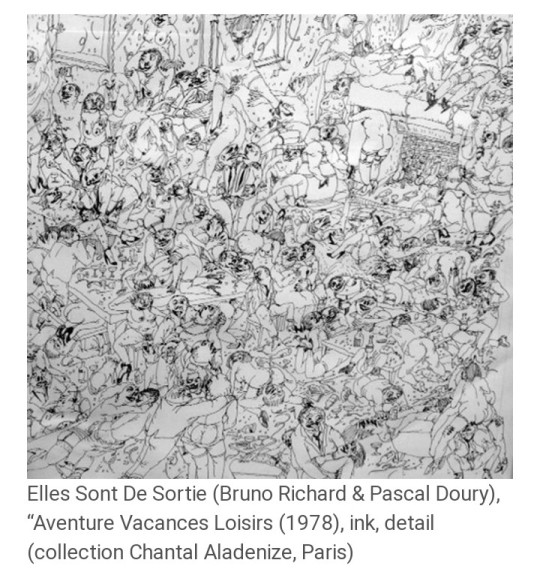

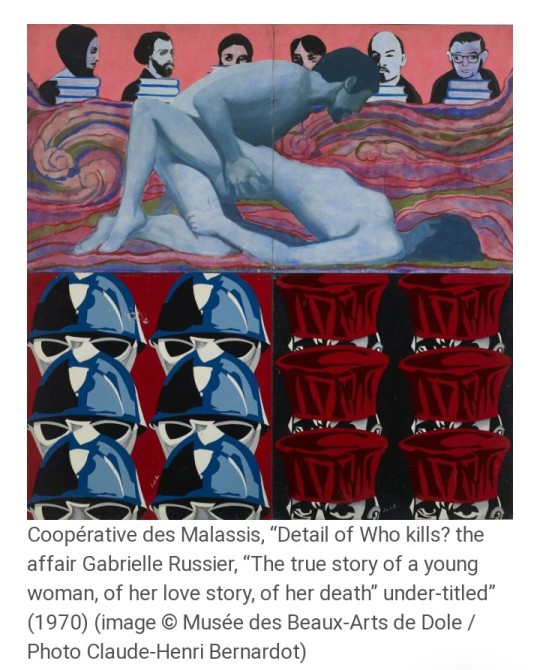

The latest misty-eyed effort is Guillaume Désanges and François Piron’s display of 700 pieces of punk and post-punk art and ephemera, L’Esprit français, Countercultures, 1969–1989, which is jarring the house at Antoine de Galbert’s La Maison Rouge.

Pierre Klossowski, "L'Hermaphrodite souverain", 1972

Bérurier Noir, “Macadam Massacre” (1984), vinyl record cover

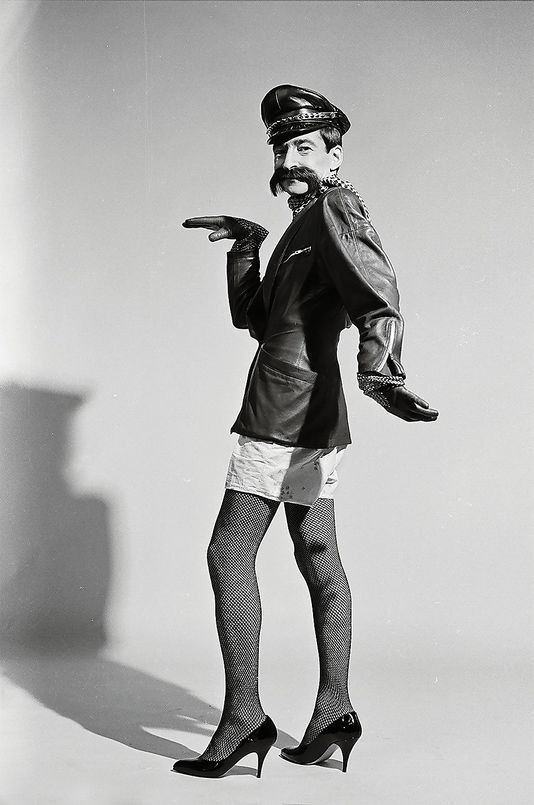

Jorge Damonte, “Copi posing for one of his roles in the play Le Frigo” (1983) (image courtesy Lola Mitchell)

#l'esprit français#countercultures 1969-1989#exhibition#mostra#art#punk art#punk#post punk#french punk and post punk#counterculture#subcultures#sottoculture#2017#la maison rouge#le monde

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

While time travel remains a hypothetical concept, imagining the ability to revisit historical events can be intriguing. Here are 20 events one might consider revisiting, each chosen for its significance or impact on shaping the course of history:

1. **The Signing of the Magna Carta (1215):**

- Witness the foundational document that laid the groundwork for constitutional governance.

2. **The Renaissance in Florence (14th-17th century):**

- Experience the cultural and intellectual flourishing of the Renaissance, interacting with influential figures like Leonardo da Vinci and Michelangelo.

3. **The Age of Enlightenment (17th-18th century):**

- Participate in the intellectual awakening that challenged traditional authority and championed reason, science, and individual rights.

4. **The American Revolution (1775-1783):**

- Observe the birth of a new nation and the drafting of the U.S. Constitution.

5. **The French Revolution (1789-1799):**

- Witness the tumultuous events that shaped modern concepts of democracy, equality, and human rights.

6. **The Industrial Revolution (18th-19th century):**

- Experience the transformative impact of industrialization on society, economy, and technology.

7. **The Constitutional Convention (1787):**

- Observe the drafting of the United States Constitution, a pivotal moment in political history.

8. **The Gettysburg Address (1863):**

- Hear Abraham Lincoln deliver his iconic address during the American Civil War.

9. **The Suffragette Movement (early 20th century):**

- Stand alongside suffragettes advocating for women's right to vote.

10. **The Apollo 11 Moon Landing (1969):**

- Witness humanity's first steps on the moon, a monumental achievement in space exploration.

11. **Woodstock Festival (1969):**

- Experience the iconic music festival that symbolized the counterculture of the 1960s.

12. **The Fall of the Berlin Wall (1989):**

- Be present during the historic moment when the wall dividing East and West Berlin came down.

13. **Nelson Mandela's Release from Prison (1990):**

- Witness the end of apartheid in South Africa as Mandela walks to freedom.

14. **The Internet's Inception (1969):**

- Observe the creation of the first message sent over ARPANET, laying the groundwork for the internet.

15. **The Wright Brothers' First Flight (1903):**

- Witness the birth of aviation as the Wright brothers achieve powered, controlled flight.

16. **The First Performance of Shakespeare's Plays (17th century):**

- Attend one of William Shakespeare's original plays during the Elizabethan era.

17. **The Building of the Great Wall of China (7th century BCE):**

- Witness the construction of one of the most iconic structures in human history.

18. **The First Printing Press (1440):**

- Be present at the invention of the printing press, a revolutionary moment in communication.

19. **The Rosetta Stone's Discovery (1799):**

- Observe the uncovering of the Rosetta Stone, unlocking the mysteries of ancient Egyptian hieroglyphs.

20. **The End of World War II (1945):**

- Experience the celebrations and relief as World War II comes to an end.

Each of these events played a pivotal role in shaping the world as we know it, and revisiting them would provide valuable insights into their historical, cultural, and societal significance.

0 notes

Text

Barbara T. Smith: Food in Feminist Concept Art

Bottinelli, Silvia, and Margherita d'Ayala Valva, eds. The Taste of Art: Cooking, Food, and Counterculture in Contemporary Practices. 2017. great for my seminar paper AND studio, hooray!

look at this lovely bread. be a shame if someone ... politicised it.

Laurie Beth Clark and Michael Peterson's Ways of Eating: Tradition, Innovation, and the Production of Community in Food-Based Art is included in the book, and it discusses the visibility of tradition and avant-garde lines of thought within food, and the significance and universality of bread - something I have considered focusing on before even reading about it - among other things.

'Bread is the food “of the people” and is associated with both populist social movements and with the reduction of the “body politic” to a consumer of bread and circuses. Except for its association with political pandering, bread is wholly wrapped up in a “virtuous” traditionalism; bread is rarely constructed as “backward” or conservative ... Perhaps the fundamental aura of bread means we should not be surprised that bread in the West is a particularly resonant food in the construction of community.' P. 227

“While cultures associate traditional foodways with both conservative and progressive values, tradition typically performs a resistance to change and a celebration of repetition.” P. 227 – tradition as a means of change, even though it's counterintuitive, is an interesting angle to view current food trends from.

Then their writing mentioned the work of Barbara T. Smith. I had not heard of Barbara T. Smith. So I found an article about her.

https://www.jstor.org/stable/3245978?seq=3

Her Ritual Meal from 1969 saw sixteen guests partake in a medicalised six course meal. They had to wear surgical scrubs, cut meat with scalpels, eat with their hands, drink from test tubes; in which wine resembled urine or blood. 'Ordinary food took on extraordinary connotations.'

'Smith's layering of western, tribal, and prehistoric rituals and ceremonies was an intuitive choice that came in part from her study of art history. While still an undergraduate at Pomona College, Smith had been struck by the way in which the civilization of the Italian Renaissance had been born from the pestilent remains of the Black Plague, an apocryphal event that wiped out at least half of Europe's population...' Is this what we're seeing, once again, with the resurgence of food-based or collective/community-centred works? what was our disaster? Was it the isolation imposed upon us by the pandemic? Is it an ongoing decline in faith for the technological age?

Documentation of Barbara Smith's Ritual Meal, 1969. (https://www.jstor.org/stable/3245978?seq=3)

She also did other bizarre food rituals, such The Celebration of the Holy Squash, in which she and others reverently ate a squash after coming together and meditating; and casting the innards of the squash in resin.

'Although The Celebration of the Holy Squash was conceived partly as a tongue-in-cheek parody of Christian rituals and institutions, Smith truly believed in the ... spiritual power of the squash ... "... the squash has consciousness, and the squash came to me and put that obligation on to me." After Smith became an ecofeminist in 1983 "I realized that the fate of me and the fate of the earth are irrevocably connected" she understood that the squash was the perfect centerpiece for a new, feminist religion.'

'In 1989, Smith ... played up the ecological implications of the squash. The first part of the performance was a parody of a Christmas pageant (nativity play) ... On December 21, the squash was put on a litter and taken in a processional from the Bronx through Harlem to St. John the Divine. Boom boxes played walking music, squash lore and recipes were distributed to people on the street ... A large fire was made in order to cook the squash. People who came to view the pageant were given little squashes ... Nitsch, who had come to New York specifically for the ceremony, spoke about the significance of the squash for Smith and taught a Native American song. Meanwhile, the original cast-resin squash was installed at Fashion Moda in a semi-permanent tableau with a life-sized cut-out of the farmer and the cook...'

It's a bit more on the outlandish side, for the kind of work I'm looking at, but it does exemplify just how far we can take food in art.

'Smith took a very different role in her 1973 performance Feed Me, part of an event entitled All Night Sculptures at Tom Marioni's San Francisco Museum of Conceptual Art. Feed Me lasted an entire night, during which a naked Smith sat in a room with a mattress, rugs, pillows, and a heater, surrounded by things with which she could be fed such as body oils, perfume, food, wine, music, and marijuana. In the background, a taped loop played "Feed Me, Feed Me" over and over again. During the course of the evening, people (mostly men) who came to participate in the piece were allowed to enter one at a time and interact with Smith, who had placed no conditions on these interactions ... Smith had an intensely spiritual experience.' The article goes on from there, I recommend reading. She's like the Marina Abramovic of food.

#art research#food#bread#performance art#relational aesthetics#feminism#ecofeminism#concept art movement#spirituality

0 notes

Photo

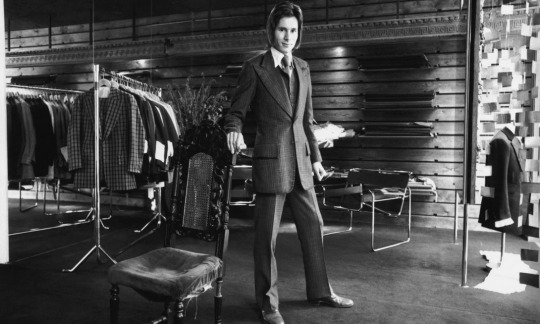

Tommy Nutter was born Thomas Albert Nutter on the 17th of April, 1943, in Barmouth, Merioneth (now Gwynedd) in Wales.

David Nutter, Tommy’s brother, has said this was due to them being evacuated to Wales during the Second World War. They grew up in Edgware, where their father, Christopher, ran a cafe, and in Kilburn, near London.

Tommy began to study tailoring at the age of 19, began to work as a tailor in the 1960s and opened ‘Nutters of Savile Road’ on Valentine’s Day in 1969 with Edward Sexton, and backed by Cilla Black and her husband, Bobby Willis and Peter Brown, who managed the Beatles and also had a romantic relationship with Tommy.

Also in 1969, Tommy dressed three of the Beatles (all but George, who wore denim) on the cover of ‘Abbey Road'. This partly led to his fame, as did his flamboyant style along with traditional Savile Road tailoring - he’s said to have reinvented the Savile Road suit, as was also seen on Mick Jagger and Elton John. He also dressed Cilla Black, for Hardy Amies, Bianca Jagger and created the clothing for Jack Nicholson’s Joker in Batman in 1989.

At the age of 49, Tommy died at Cromwell Hospital, London, from AIDS-related complications, on the 17th of August, 1992.

Tommy’s brother, David, spoke of his own and Tommy’s sexuality for Lance Richardson’s ‘House of Nutter: The Rebel Tailor of Savile Row’. Both were fascinated by Hollywood, wanted to escape their working class background, weren’t supported by their father, and were influenced by gay counterculture. David Nutter is a retired music photographer who Elton John, Mick Jagger, the Beatles, as well as Queen and many more.

#tommy nutter#1960s#gay history#queer history#lgbt history#welsh history#david nutter#1970s#welsh queer history

41 notes

·

View notes

Text

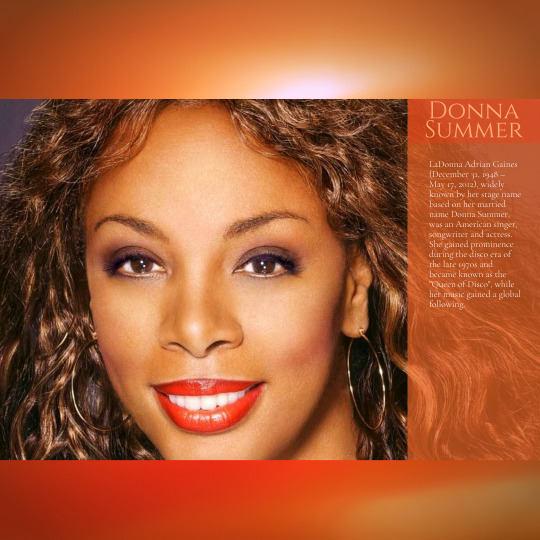

Donna Summer

LaDonna Adrian Gaines (December 31, 1948 – May 17, 2012), widely known by her stage name based on her married name Donna Summer, was an American singer, songwriter and actress. She gained prominence during the disco era of the late 1970s and became known as the "Queen of Disco", while her music gained a global following.

While influenced by the counterculture of the 1960s, Summer became the lead singer of a psychedelic rock band named Crow and moved to New York City. Joining a touring version of the musical Hair, she left New York and spent several years living, acting and singing in Europe, where she met music producers Giorgio Moroder and Pete Bellotte in Munich, where they recorded influential disco hits such as "Love to Love You Baby" and "I Feel Love", marking her breakthrough into an international career. Summer returned to the United States in 1975, and other hits such as "Last Dance", "MacArthur Park", "Heaven Knows", "Hot Stuff", "Bad Girls", "Dim All the Lights", "No More Tears (Enough Is Enough)" (duet with Barbra Streisand) and "On the Radio" followed.

Summer earned a total of 42 hit singles on the US Billboard Hot 100 in her lifetime, with 14 of those reaching the top-ten. She claimed a top 40 hit every year between 1975 and 1984, and from her first top-ten hit in 1976, to the end of 1982, she had 12 top-ten hits (10 were top-five hits), more than any other act during that time period. She returned to the Hot 100's top-five in 1983, and claimed her final top-ten hit in 1989 with "This Time I Know It's for Real". She was the first artist to have three consecutive double albums reach number one on the US Billboard 200 chart and charted four number-one singles in the US within a 12-month period. She also charted two number-one singles on the R&B Singles chart in the US and a number-one single in the United Kingdom. Her most recent Hot 100 hit came in 1999 with "I Will Go with You (Con Te Partiro)". While her fortunes on the Hot 100 waned through those decades, Summer remained a force on the Billboard Dance Club Songs chart over her entire career.

Summer died on May 17, 2012, from lung cancer, at her home in Naples, Florida. She sold over 100 million records worldwide, making her one of the best-selling music artists of all time. She won five Grammy Awards. In her obituary in The Times, she was described as the "undisputed queen of the Seventies disco boom" who reached the status of "one of the world's leading female singers." Giorgio Moroder described Summer's work with them on the song "I Feel Love" as "really the start of electronic dance" music. In 2013, Summer was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. In December 2016, Billboard ranked her at No. 6 on its list of the Greatest of All Time Top Dance Club Artists .

Early life

LaDonna Adrian Gaines was born on December 31, 1948 in Boston, Massachusetts, to Andrew and Mary Gaines, and was third of seven children. She was raised in the Boston neighborhood of Mission Hill. Her father was a butcher, and her mother was a schoolteacher.

Summer's performance debut occurred at church when she was ten years old, replacing a vocalist who failed to appear. She attended Boston's Jeremiah E. Burke High School where she performed in school musicals and was considered popular. In 1967, just weeks before graduation, Summer left for New York City, where she joined the blues rock band Crow. After a record label passed on signing the group since it was only interested in the band's lead singer, the group agreed to dissolve.

Summer stayed in New York and auditioned for a role in the counterculture musical, Hair. She landed the part of Sheila and agreed to take the role in the Munich production of the show, moving there after getting her parents' reluctant approval. She eventually became fluent in German, singing various songs in that language, and participated in the musicals Ich bin ich (the German version of The Me Nobody Knows), Godspell, and Show Boat. Within three years, she moved to Vienna, Austria, and joined the Vienna Volksoper. She briefly toured with an ensemble vocal group called FamilyTree, the creation of producer Günter "Yogi" Lauke.

In 1968, Summer released (as Donna Gaines) on Polydor her first single, a German version of the title "Aquarius" from the musical Hair, followed in 1971 by a second single, a remake of the Jaynetts' 1963 hit, "Sally Go 'Round the Roses", from a one-off European deal with Decca Records. In 1969, she issued the single "If You Walkin' Alone" on Philips Records.

She married Austrian actor Helmuth Sommer in 1973, and gave birth to their daughter (called Mimi) Natalia Pia Melanie Sommer, the same year. She provided backing vocals for producer-keyboardist Veit Marvos on his Ariola Records release Nice to See You, credited as "Gayn Pierre". Several subsequent singles included Donna performing with the group, and the name "Gayn Pierre" was used while performing in Godspell with Helmuth Sommer during 1972.

Music career

1974–1979: Initial success

While working as a model part-time and back up singer in Munich, Summer met German-based producers Giorgio Moroder and Pete Bellotte during a recording session for Three Dog Night at Musicland Studios. The trio forged a working partnership, and Donna was signed to their Oasis label in 1974. A demo tape of Summer's work with Moroder and Bellotte led to a deal with the European-distributed label Groovy Records. Due to an error on the record cover, Donna Sommer became Donna Summer; the name stuck. Summer's first album was Lady of the Night. It became a hit in the Netherlands, Sweden, Germany and Belgium on the strength of two songs, "The Hostage" and the title track "Lady of the Night". "The Hostage" reached the top of the charts in France, but was removed from radio playlists in Germany because of the song's subject matter; a high ranking politician that had recently been kidnapped and held for ransom. One of her first TV appearances was in the television show, Van Oekel's Discohoek, which started the breakthrough of "The Hostage", and in which she gracefully went along with the scripted absurdity and chaos in the show.

In 1975, Summer passed on an idea for a song to Moroder who was working with another artist; a song that would be called "Love to Love You". Summer and Moroder wrote the song together, and together they worked on a demo version with Summer singing the song. Moroder decided that Summer's version should be released. Seeking an American release for the song, it was sent to Casablanca Records president Neil Bogart. Bogart played the song at one of his extravagant industry parties, where it was so popular with the crowd, they insisted that it be played over and over, each time it ended. Bogart requested that Moroder produce a longer version for discothèques. Moroder, Bellotte, and Summer returned with a 17-minute version. Bogart tweaked the title to "Love to Love You Baby", and Casablanca signed Summer, releasing the single in November 1975. The shorter 7" version of the single was promoted by radio stations, while clubs regularly played the 17 minute version (the longer version would also appear on the album).

By early 1976, "Love to Love You Baby" had reached No. 2 on the U.S. Billboard Hot 100 chart and had become a Gold single, while the album had sold over a million copies. The song generated controversy due to Summer's moans and groans, and some American stations, like those in Europe with the initial release, refused to play it. Despite this, "Love to Love You Baby" found chart success in several European countries, and made the Top 5 in the United Kingdom despite the BBC ban. Casablanca wasted no time releasing the album A Love Trilogy, featuring "Try Me, I Know We Can Make It" No. 80 and Summer's remarkable rendition of Barry Manilow's "Could It Be Magic" No. 52, which was followed by Four Seasons of Love, which spawned the singles "Spring Affair" No. 58 and "Winter Melody", No. 43. Both albums went Gold.

In 1977, Summer released the concept album I Remember Yesterday. The song "I Feel Love", reached No. 6 on the Hot 100 chart. and No. 1 in the UK. She received her first American Music Award nomination for Favorite Soul/R&B Female Artist. The single would attain Gold status and the album went Platinum in the U.S. Another concept album, also released in 1977, was Once Upon a Time, a double album which told of a modern-day Cinderella "rags to riches" story. This album would attain Gold status. Summer recorded the song "Down Deep Inside" as the theme song for the 1977 film The Deep. In 1978, Summer acted in the film Thank God It's Friday, the film met with modest success; the song "Last Dance", reached No. 3 on the Hot 100. The soundtrack and single both went Gold and resulted in Summer winning her first Grammy Award, for Best Female R&B Vocal Performance. Its writer, Paul Jabara, won both an Academy Award and Golden Globe Award for the composition. Summer also had "With Your Love" and "Je t'aime... moi non plus", on the soundtrack. Her version of the Jimmy Webb ballad, "MacArthur Park", became her first No. 1 hit on the Hot 100 chart. It was also the only No. 1 hit for songwriter Jimmy Webb; the single went Gold and topped the charts for three weeks. She received a Grammy nomination for Best Female Pop Vocal Performance. The song was featured on Summer's first live album, Live and More, which also became her first album to hit number one on the U.S. Billboard 200 chart and went double-Platinum, selling over 2 million copies. The week of November 11, 1978, Summer became the first female artist of the modern rock era to have the No. 1 single on the Hot 100 and album on the Billboard 200 charts, simultaneously. The song "Heaven Knows", which featured Brooklyn Dreams singer Joe "Bean" Esposito; reached No. 4 on the Hot 100 and became another Gold single.

In 1979, Summer won three American Music Awards for Single, Album and Female Artist, in the Disco category at the awards held in January. Summer performed at the world-televised Music for UNICEF Concert, joining contemporaries such as ABBA, Olivia Newton-John, the Bee Gees, Andy Gibb, Rod Stewart, John Denver, Earth, Wind & Fire, Rita Coolidge and Kris Kristofferson for a TV special that raised funds and awareness for the world's children. Artists donated royalties of certain songs, some in perpetuity, to benefit the cause. Summer began work on her next project with Moroder and Bellotte, Bad Girls. Mororder brought in Harold Faltermeyer, with whom he had collaborated on the soundtrack of film Midnight Express, to be the album's arranger. Faltermeyer's role would significantly increase from arranger, as he played keyboards and wrote songs with Summer.

The album went triple-Platinum, spawning the number-one hits "Hot Stuff" and "Bad Girls", that went Platinum, and the number-two "Dim All the Lights" which went Gold. The week of June 16, 1979, Summer would again have the number-one single on the Hot 100 chart, and the number-one album on the Billboard 200 chart; when "Hot Stuff" regained the top spot on the Hot 100 chart. The following week, "Bad Girls" would be on top of the U.S. Top R&B albums chart, "Hot Stuff" remained at No. 1, and "Bad Girls", the single, would climb into the top five on the Hot 100. The following week, Summer was the first solo artist to have two songs in the Hot 100 top three at the same time. In July 1979, Summer topped the Hot 100 singles chart, and the Billboard 200 albums chart, and the Soul singles chart simultaneously. In the week of November 10, 1979, "Dim All the Lights" peaked at No. 2 for two weeks; the following week "No More Tears (Enough is Enough)" would get to No. 3; and once again Summer would have two songs in the top 3, on the Hot 100. One week later, "No More Tears" climbed to No. 1 spot on the Hot 100 chart, and "Dim All the Lights" went to No. 4; she again had two songs in the top 5 of the Hot 100 chart. In the span of eight months, Summer had topped both the singles and albums charts simultaneously, three times. She became the first Female Artist to have three number-one singles in a calendar year. With "Mac Arthur Park", "Hot Stuff", "Bad Girls", and the Barbra Streisand-duet "No More Tears (Enough is Enough)", Summer achieved four number-one hits on the Hot 100 chart within a 12-month period. Including "Heaven Knows" and "Dim All the Lights" she had achieved six top 4 singles on the Hot 100 chart in the same 12-month period. Those songs, along with "Last Dance", "On the Radio", and "The Wanderer", would give her nine Top 5 singles on the Hot 100 chart in just over a two-year period. The single, "No More Tears (Enough is Enough)" would sell over 2 million copies becoming a Platinum success. "Hot Stuff" won her a Grammy Award in the Best Female Rock Vocal Performance, the first time the category was included. She was nominated for the Grammy Award for Album of the Year and both Best Female Pop Vocal Performance and Best Female R&B Vocal Performance, as well as Best Disco Recording. That year, Summer played eight sold-out nights at the Universal Amphitheater in Los Angeles.

Casablanca then released On the Radio: Greatest Hits Volumes I & II, her first (international) greatest hits set, in 1979. The album was mixed differently than the original songs issued on it, with each song segueing into the next, and included two new songs "On the Radio" and "No More Tears (Enough is Enough)". It would be the first time that such an album package would be made. The album went No. 1, her third consecutive No. 1 album on the Billboard 200, and gained double-Platinum status. "On the Radio", reached No. 5, selling over a million copies in the U.S. alone, making it a Gold single. Summer would again receive a Grammy nomination for Best Female Pop Vocal Performance.

1980–1985

Summer received four nominations for the 7th Annual American Music Awards in January 1980, and took home awards for Female Pop/Rock and Female Soul/R&B Artist; and well as Pop/Rock single for "Bad Girls". Just over a week after the awards, Summer had her own nationally televised special, The Donna Summer Special, which aired on ABC network on January 27, 1980. After the release of the On the Radio album, Summer wanted to branch out into other musical styles, which led to tensions between her and Casablanca Records. Casablanca wanted her to continue to record disco only. Summer was upset with President Neil Bogart over the early release of the single "No More Tears (Enough is Enough)"; she had penned "Dim All the Lights" alone, and was hoping for a number-one hit as a songwriter. Not waiting until "Dim All the Lights" had peaked, or at least another month as promised; Summer felt it had detracted from the singles chart momentum. Summer and the label parted ways in 1980, and she signed with Geffen Records, the new label started by David Geffen. Summer had filed a $10 million lawsuit against Casablanca; the label counter-sued. In the end, she did not receive any money, but won the rights to her own lucrative song publishing.

Summer's first Geffen album, The Wanderer, featured an eclectic mixture of sounds, bringing elements of rock, rockabilly, new wave and gospel music. The Wanderer was rushed to market. The producers of the album wanted more production time. The album continued Summer's streak of Gold albums with the title track peaking at No. 3 on the Hot 100 chart. Its follow-up singles were, "Cold Love" No.33 and "Who Do You Think You're Foolin'", No.40. Summer was nominated for Best Female Rock Vocal Performance for "Cold Love", and Best Inspirational Performance for "I Believe in Jesus" at the 1981 Grammy Awards.

She would soon be working on her next album. It was to be another double album set. When David Geffen stopped by the studio for a preview, he was warned that it was a work in progress, but it was almost done. That was a mistake, because only a few tracks had been finished, and most of them were in demo phase. He heard enough to tell producers that it was not good enough; the project was canceled. It would be released years later in 1996, under the title I'm a Rainbow. Over the years, a few of the tracks would be released. The song "Highway Runner" appears on the soundtrack for the film Fast Times at Ridgemont High. "Romeo" appears on the Flashdance soundtrack. Both, "I'm a Rainbow" and "Don't Cry For Me Argentina" would be on her 1993 Anthology album.

David Geffen hired top R&B and pop producer Quincy Jones to produce Summer's next album, the eponymously titled Donna Summer. The album took over six months to record as Summer, who was pregnant at the time, found it hard to sing. During the recording of the project, Neil Bogart died of cancer in May 1982 at age 39. Summer would sing at his funeral. The album included the top ten hit "Love Is in Control (Finger on the Trigger)"; for which she received a Grammy nomination for Best Female R&B Vocal Performance. Summer was also nominated for Best Female Rock Vocal Performance for "Protection", penned for her by Bruce Springsteen. Other singles included a cover of the Jon and Vangelis song "State of Independence" (No. 41 pop) and "The Woman in Me" (No. 33 pop).

By then Geffen Records was notified by Polygram Records, who now owned Casablanca, that Summer still needed to deliver them one more album to fulfill her contract with them. Summer had her biggest success in the 1980s while on Geffen's roster with her next album She Works Hard for the Money and its title song — which were released by Mercury Records in a one-off arrangement to settle Summer's split with the soon-to-be-defunct Casablanca Records, whose catalogue now resided with Mercury and Casablanca's parent company PolyGram.

Summer recorded and delivered the album She Works Hard for the Money and Polygram released it on its Mercury imprint in 1983. The title song became a major hit, reaching No. 3 on the US Hot 100, as well as No. 1 on Billboard's R&B chart for three weeks. It also garnered Summer another Grammy nomination, for Best Female Pop Vocal Performance. "Unconditional Love", which featured the British group Musical Youth, and "Love Has a Mind of Its Own" did not crack the top 40. The album itself was certified Gold, and climbed to No. 9 on the Billboard 200 chart; the highest chart position of any female artist in male-dominated 1983. The song "He's a Rebel" would win Summer her third Grammy Award, this time for Best Inspirational Performance.

British director Brian Grant was hired to direct Summer's video for "She Works Hard for the Money". The video was a success, being nominated for Best Female Video and Best Choreography at the 1984 MTV Music Video Awards; Summer became one of the first African-American artists, and the first African-American female artist to have her video played in heavy rotation on MTV. Grant would also be hired to direct Summer's Costa Mesa HBO concert special, A Hot Summers Night. Grant who was a fan of the song State of Independence had an idea for a grand finale. He wanted a large chorus of children to join Summer on stage at the ending of the song. His team looked for local school children in Orange County, to create a chorus of 500 students. On the final day of rehearsals, the kids turned up and they had a full rehearsal. According to Grant, "It looked and sounded amazing. It was a very emotional, very tearful experience for everyone who was there." He thought if this was that kind of reaction in rehearsal, then what an impact it would have in the concert. After the rehearsal Grant was informed that he could not use the kids because the concert would end after 10 pm; children could not be licensed to be on stage at such a late hour (California had strict child labor laws in 1983). "It's a moment that I regret immensely: a grand finale concept I came up with that couldn't be filmed in the end". When the final sequence was filmed, Summer's daughter Mimi and her family members joined her on stage for "State of Independence".

In late 1983, David Geffen enlisted She Works Hard for the Money's producer Michael Omartian to produce Cats Without Claws. Summer was happy that Geffen and his executives stayed out of the studio during the recording and thanked him in the album's liner notes, but her request for the lead single would be rejected. The album failed to attain Gold status in the U.S., her first album not to do so. It was first album not to yield a top ten hit, since 1977's Once Upon a Time. The Drifters cover "There Goes My Baby" reached No. 21 and "Supernatural Love" went to No. 75. She would win another Grammy for Best Inspirational Performance for the song "Forgive Me".

On January 19, 1985, she sang at the nationally televised 50th Presidential Inaugural Gala the day before the second inauguration of Ronald Reagan.

1986–1989

In 1986, Harold Faltermeyer wrote the title song for a German ski movie called Fire and Ice, and thought Summer would be ideal to sing the song. He decided to reach out to Summer and, although she was not interested in singing the song, she was very much interested in working with Faltermeyer again. After a meeting with David Geffen he was on board with the project. Summer's main objective for the album was that it have stronger R&B influences; Faltermeyer who had just finished doing the soundtracks to Top Gun and Fletch, was after a tough FM-oriented sound. On completion, Geffen liked what he heard, but his executives did not think there were enough songs that could be deemed singles. They wanted Faltermeyer to produce "Dinner with Gershwin", but he was already busy with another project, so another producer was found. They also substituted a previous recording called "Bad Reputation", songs like "Fascination", fell by the wayside. Geffen had shared the vision of moving Summer into the R&B market as a veteran artist, but these expectations were not met. Faltermeyer, in a 2012 interview with Daeida Magazine, said, "She was an older artist by then and the label's priority may have been on the youth market. The decision was made afterward by executives who were looking for a radio hit for 1987 and not something that would perhaps last beyond then." The label's President Ed Rosenblatt would later admit: "The company never intended to focus on established superstars". The album All Systems Go, did not achieve Gold status. The single "Dinner with Gershwin" (written by Brenda Russell) stalled at 48 in the US, though it became a hit in the UK, peaking at No. 13. The album's title track, "All Systems Go", was released only in the UK, where it peaked at No. 54.

For Summer's next album, Geffen Records hired the British hit production team of Stock Aitken Waterman (or SAW), who enjoyed incredible success writing and producing for such acts as Kylie Minogue, Bananarama, and Rick Astley, among others. The "SAW" team describe the working experience as a labour of love, and said it was their favourite album of all that they had recorded. Geffen decided not to release the album Another Place and Time, and Summer and Geffen Records parted ways in 1988. The album was released in Europe in March 1989 on Warner Bros. Records, which had been Summer's label in Europe since 1982. The single "This Time I Know It's for Real" became a top ten hit in several countries in Europe, prompting Warner Bros.' sister company, Atlantic Records, to sign Summer in the U.S. The single peaked at No. 7 on the US Hot 100 and became her 12th Gold single in America. She scored two more UK hits from the album, "I Don't Wanna Get Hurt" (UK No. 7) and "Love's About to Change My Heart" (UK No. 20).

In 1989, Summer and her husband, Bruce Sudano, had been in talks to do a new kind of reality-based sitcom. It would be based on their own hectic household. At the time, they lived with their children Amanda, Brooklyn and Mimi, two sets of in-laws, and a maid. The television network started changing the premise of the show, making it less funny, says Sudano, "And because we were an interracial couple, they didn't want us to be married anymore". In 1989, this was "an issue. So with that mentality we just backed out of it."

1990–1999: Mistaken Identity, acting, and Live & More Encore

In 1990, a Warner compilation, The Best of Donna Summer, was released (No U.S. issue). The album went Gold in the UK after the song "State of Independence" was re-released there to promote the album. The following year, Summer worked with producer Keith Diamond emerged with the album Mistaken Identity, which included elements of R&B as well as new jack swing. "When Love Cries" continued her success on the R&B charts, reaching No. 18. In 1992, Summer embarked on a world tour and later that year received a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame. She reunited with Giorgio Moroder, for the song "Carry On", which was included on the 1993, Polygram issued The Donna Summer Anthology, it contained 34 tracks of Summer's material with Casablanca and Mercury Records, and from her tenures with Atlantic and Geffen.

Summer signed with Mercury/Polygram that same year, and in 1994 she re-teamed with producer Michael Omartian to record a Christmas album, Christmas Spirit, which included classic Christmas songs such as "O Holy Night" and "White Christmas" and three Summer-penned songs,"Christmas is Here", "Lamb of God" and the album's title track. Summer was accompanied by the Nashville Symphony Orchestra. Another hits collection, Endless Summer: Greatest Hits, was released featuring eighteen songs. There were two new tracks "Melody of Love (Wanna Be Loved)" and "Any Way at All". In 1994, she also contributed to the Tribute To Edith Piaf album, singing La Vie En Rose. In 1995, "Melody of Love (Wanna Be Loved)" went No. 1 on the US dance charts, and No. 21 in the UK. In 1996, Summer recorded a duet with Bruce Roberts, Whenever There Is Love, which appeared on the soundtrack to the film Daylight (1996 film). In 1996, Summer also recorded Does He Love You with Liza Minnelli, which appeared Minnelli's Gently (album).

During this time, Summer had role on the sitcom Family Matters as Steve Urkel's (Jaleel White) Aunt Oona. She made a few appearances in 1997. In 1998, Summer received the first Grammy Award for Best Dance Recording, after a remixed version of her 1992 collaboration with Giorgio Moroder, "Carry On", was released in 1997. In 1999, Summer was asked to do the Divas 2 concert, but when she went in and met with the producers, it was decided that they would do Donna in concert by herself. Summer taped a live television special for VH1 titled Donna Summer – Live & More Encore, producing the second highest ratings for the network that year, after their annual Divas special. A CD of the event was released by Epic Records and featured two studio recordings, "I Will Go with You (Con te partirò)" and "Love Is the Healer", both of which reached No. 1 on the U.S. dance charts.

2000–2009: Later recordings and Crayons

In 2000, Summer participated in VH1's third annual Divas special, dedicated to Diana Ross, she sang the Supreme's hit Reflections, and her own material for the show. "The Power of One" is a theme song for the movie Pokémon: The Movie 2000. The dramatic ballad was produced by David Foster and dance remixes were also issued to DJs and became another dance floor success for Summer, peaking at No. 2 on the same chart in 2000. In 2003, Summer issued her autobiography, Ordinary Girl: The Journey, and released a best-of set titled The Journey: The Very Best of Donna Summer. In 2004, Summer was inducted into the Dance Music Hall of Fame as an artist, alongside the Bee Gees and Barry Gibb. Her classic song, "I Feel Love", was inducted that night as well. In 2004 and 2005, Summer's success on the dance charts continued with the songs "You're So Beautiful" and "I Got Your Love". In 2004, Summer re-recorded the track with the Irish pop band Westlife (with a live performance) for the compilation album, Discomania.

In 2008, Summer released her first studio album of fully original material in 17 years, entitled Crayons. Released on the Sony BMG label Burgundy Records, it peaked at No. 17 on the U.S. Top 200 Album Chart, her highest placing on the chart since 1983. The songs I'm a Fire, Stamp Your Feet and Fame (The Game) all reached No. 1 on the U.S. Billboard Dance Chart. The ballad Sand on My Feet was released to adult contemporary stations and reached No. 30 on that chart. Summer said, "I wanted this album to have a lot of different directions on it. I did not want it to be any one baby. I just wanted it to be a sampler of flavors and influences from all over the world. There's a touch of this, a little smidgeon of that, a dash of something else, like when you're cooking."

2010–2013: Final recordings

On July 29, 2010, Summer gave an interview with Allvoices.com wherein she was asked if she would consider doing an album of standards. She said, "I actually am, probably in September. I will begin work on a standards album. I will probably do an all-out dance album and a standards album. I'm going to do both and we will release them however we're going to release them. We are not sure which is going first."

In August 2010, Summer released the single "To Paris With Love", co-written with Bruce Roberts and produced by Peter Stengaard. The single went to No. 1 on the U.S. Billboard Dance Chart in October 2010. That month, Summer also appeared on the PBS television special Hitman Returns: David Foster and Friends. In it, Summer performed with Seal on a medley of the songs "Un-Break My Heart / Crazy / On the Radio" before closing the show with "Last Dance".

On September 15, 2010, Summer appeared as a guest celebrity, singing alongside contestant Prince Poppycock, on the television show America's Got Talent.

On June 6, 2011, Summer was a guest judge on the show Platinum Hit, in an episode entitled "Dance Floor Royalty". In July of that same year, Summer was working at Paramount Recording Studios in Los Angeles with her nephew, the rapper and producer O'Mega Red. Together they worked on a track titled "Angel".

On December 11, 2012, after four prior nominations, Summer was posthumously announced to be one of the 2013 inductees to the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame., and was inducted on April 18, 2013, at Los Angeles' Nokia Theater.

A remix album titled Love to Love You Donna, containing new remixes of some of Summer's classics, was released in October 2013. "MacArthur Park" was remixed by Laidback Luke for the remix collection; it was also remixed by Ralphi Rosario, which version was released to dance clubs all over America and successfully peaked at No. 1, giving Summer her first posthumous number-one single, and her twentieth number-one on the charts.

Controversy

In the mid-1980s, Summer was embroiled in a controversy. She allegedly had made anti-gay remarks regarding the then-relatively new disease, AIDS. Summer publicly denied that she had ever made any such comments, and in a letter to the AIDS campaign group ACT UP in 1989 said it was "a terrible misunderstanding." In explaining why she did not respond to ACT UP sooner, Summer stated "I was unknowingly protected by those around me from the bad press and hate letters. If I have caused you pain, forgive me." She closed her letter with Bible quotes (from Chapter 13 of 1 Corinthians).

Also in 1989, Summer told The Advocate magazine that "a couple of the people I write with are gay, and they have been ever since I met them. What people want to do with their bodies is their personal preference." A couple of years later, she filed a lawsuit against New York magazine when it printed an old story about the rumors as fact, just as she was about to release her album Mistaken Identity in 1991. According to a Biography television program dedicated to Summer in which she participated in 1995, the lawsuit was settled out of court, though neither side was able to divulge any details.

Personal life

Summer was raised in the African Methodist Episcopal Church. She married the Austrian actor Helmuth Sommer in 1973 and gave birth to their daughter Natalia Pia Melanie Sommer (called Mimi) the same year. The couple divorced in 1976, but Summer kept the anglicized version of her ex-husband's surname as her stage name.

Summer married Brooklyn Dreams singer Bruce Sudano on July 16, 1980. On January 5, 1981, she gave birth to their daughter Brooklyn Sudano (who is now an actress, singer and dancer), and on August 11, 1982 she gave birth to their daughter Amanda Sudano (who in 2005 became one half of the musical duo Johnnyswim alongside Abner Ramirez). In Los Angeles, Summer was also one of the founding members of Oasis Church.

Summer and her family moved from the Sherman Oaks area of Los Angeles to Nashville, Tennessee, in1995, where she took time off from show business to focus on painting, a hobby she had begun back in the 1980s.

In 1995, Summer's mother died of pancreatic cancer. Her father died of natural causes in December 2004.

Death

Summer died on May 17, 2012 at her home in Naples, Florida, aged 63, from lung cancer. A nonsmoker, Summer theorized that her cancer was caused by inhaling toxic fumes and dust from the September 11 attacks in New York City. However some reports have instead attributed the cancer to Summer's smoking during her younger years, her continued exposure to second-hand smoking while performing in clubs well after she had herself quit, and a predisposition to this disease in the family. Summer was survived by her husband, Bruce Sudano, and her daughters Mimi (with ex-husband Helmut Sommer), Brooklyn Sudano, and Amanda Sudano.

Summer's funeral service was held in Christ Presbyterian Church in Nashville, Tennessee, on the afternoon of May 23, 2012. The exact location and time of the service were kept secret. Several hundred of Summer's friends and relatives appeared at the funeral, according to CNN. The funeral was a private ceremony, and cameras were not allowed inside the church. She was interred in the Harpeth Hills Memory Gardens cemetery in Nashville.

Reaction

Singers and music industry professionals around the world reacted to Summer's death. Gloria Gaynor said she was "deeply saddened" and that Summer was "a fine lady and human being". Liza Minnelli said, "She was a queen, The Queen Of Disco, and we will be dancing to her music forever." She said that her "thoughts and prayers are with her family always." Dolly Parton said, "Donna, like Whitney, was one of the greatest voices ever. I loved her records. She was the disco queen and will remain so. I knew her and found her to be one of the most likable and fun people ever. She will be missed and remembered." Janet Jackson wrote that Summer "changed the world of music with her beautiful voice and incredible talent." Barbra Streisand wrote, "I loved doing the duet with her. She had an amazing voice and was so talented. It's so sad." Quincy Jones wrote that Summer's voice was "the heartbeat and soundtrack of a generation." Aretha Franklin said, "It's so shocking to hear about the passing of Donna Summer. In the 1970s, she reigned over the disco era and kept the disco jumping. Who will forget 'Last Dance'? A fine performer and a very nice person." Chaka Khan said, "Donna and I had a friendship for over 30 years. She is one of the few black women I could speak German with and she is one of the few friends I had in this business." Gloria Estefan averred that "It's the end of an era", and posted a photo of herself with Summer. Mary J. Blige tweeted "RIP Donna Summer !!!!!!!! You were truly a game changer !!!" Lenny Kravitz wrote "Rest in peace Donna, You are a pioneer and you have paved the way for so many of us. You transcended race and genre. Respect.. Lenny".

Beyoncé penned a personal note: "Donna Summer made music that moved me both emotionally and physically to get up and dance. You could always hear the deep passion in her voice. She was so much more than the queen of disco she became known for, she was an honest and gifted singer with flawless vocal talent. I've always been a huge fan and was honored to sample one of her songs. She touched many generations and will be sadly missed. My love goes out to her family during this difficult time. Love, B".

David Foster said, "My wife and I are in shock and truly devastated. Donna changed the face of pop culture forever. There is no doubt that music would sound different today if she had never graced us with her talent. She was a super-diva and a true superstar who never compromised when it came to her career or her family. She always did it with class, dignity, grace and zero attitude. She lived in rare air ... She was the most spectacular, considerate, constant, giving, generous and loving friend of 35 years. I am at a total loss trying to process this tragic news."

U.S. President Barack Obama said, "Michelle and I were saddened to hear about the passing of Donna Summer. A five-time Grammy Award winner, Donna truly was the 'Queen of Disco.' Her voice was unforgettable and the music industry has lost a legend far too soon. Our thoughts and prayers go out to Donna's family and her dedicated fans."

Summer was honored at the 2012 Billboard Music Awards ceremony. Singer Natasha Bedingfield honored Summer, calling her "a remarkable woman who brought so much light and who inspired many women, including myself, through her music. And if we can remember her through her music, this will never really be the last dance." After her statement, she began to sing "Last Dance", Summer's Academy Award-winning song. As she sang the song, photos of Summer were displayed on a screen overhead.

Fans paid tribute to Summer by leaving flowers and memorabilia on her star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame. A few days after her death, her album sales increased by 3,277 percent, according to Nielsen SoundScan. Billboard Magazine reported that the week before she died, Summer sold about 1,000 albums. After her death that number increased to 26,000.

Legacy

According to singer Marc Almond, Summer's collaboration with producer Giorgio Moroder "changed the face of music". Summer was the first artist to have three consecutive double albums reach No. 1 on Billboard's album chart: Live and More, Bad Girls and On the Radio: Greatest Hits Volumes I & II. She became a cultural icon and her prominence on the dance charts, for which she was referred to as the Queen of Disco, made her not just one of the defining voices of that era, but also an influence on pop artists from Madonna to Beyoncé. Unlike some other stars of disco who faded as the music became less popular in the early 1980s, Summer was able to grow beyond the genre and segued to a pop-rock sound. She had one of her biggest hits in the 1980s with "She Works Hard For the Money", which became another anthem, this time for women's rights. Summer was the first black woman to be nominated for an MTV Video Music Award. Summer remained a force on the Billboard Dance/Club Play Songs chart throughout her career and notched 19 number one singles. Her last studio album, 2008's Crayons, spun off three No. 1 dance/club hits with "I'm a Fire", "Stamp Your Feet" and "Fame (The Game)". In May 2012, it was announced that "I Feel Love" was included in the list of preserved recordings at the Library of Congress' National Recording Registry. Her Rock and Roll Hall of Fame page listed Summer as "the Diva De Tutte Dive, the first true diva of the modern pop era".

Keri Hilson portrayed Donna Summer in her 2010 music video for "Pretty Girl Rock." In 2018, Summer: The Donna Summer Musical, a biographical musical featuring Summer's songs, began performances on Broadway at the Lunt-Fontanne Theatre, following a 2017 world premiere at the La Jolla Playhouse in San Diego.

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Internet was WHAT?

Probably a high percentage knows that Internet really expanded between the 1980s and the 1990s, specially thanks to Internet pioneers that decided to come up with new terms such as “cyberspace” or with new acronyms like “MOO” and “MUD” (supposedly might be referred to videogames)

Yes you already knew that, of course. But do you know how Internet actually was? It was the coolest war machine! Kind of...

I will explain myself better trying to wrap up the basic concepts:

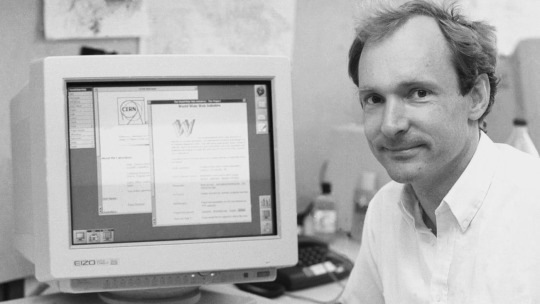

Internet started as a small publicly owned computer network established in 1969 in the United States. At the time it was not called how we know it today but it was called internetworking, in fact the term Internet only emerged in 1974 as an abbreviation. The “modern” Internet dates from 1983 with the establishment of a network of networks independent of the US armed forces.

A moment of transition happened when CERN (European Organization for Nuclear Research) adopted internet protocol (IP) for its internal connection and then consequently, in 1989, they opened their first external IP connection.

It’s expansion was also contributed by Globalization which was at its first steps. Naturally, further in the years Internet returned the favor by letting Globalization actually happen.

So, with the internationalisation of the internet, it’s first key applications were e-mails and bulletin boards. And believe it or not, the world wide web (or as we all know it as WWW) publicly launched in 1991. Then of course, the new century saw the rise of social media with the launch of Facebook in 2004 and consequently in 2010, smartphones took off.

But the most absurd part is internet’s technological innovation.

The Internet started as a vast machine that occupied a whole room and turned into a normal object that we can carry around and keep on our laps

Internet went through different developments such as computer networking, shared codes for transporting and addressing communication, and of cloud computing

The Internet became a connective software that facilitated accessing, storage, linking

Internet’s development of communications infrastructure.

Can you believe that Internet did all this in just thirty years? But the most important part was how Internet was at the actual beginning.

Remember when I said that in 1989 CERN opened their first external IP connection? Do you think that’s casual? I don’t think so.

Even though Internet is seen as an agency of peace, it was actually a product of the Cold War.

In 1957, the Soviet Union launched a satellite orbiting the Earth; a factor that was not really appreciated by the Pentagon, which saw this action both as a demonstration but also as a threat. In fact, the Pentagon set up the Advanced Research Projects Agency (ARPA)— a new, independent military body whose aim was to bridge the space gap and to ensure that a technological defeat from the Soviet Union would never happen again. The main idea was also to have one single network in order to maintain all the information together and also to have all different computers around the world function together as a unit. This network was called ARPANET.

Computer networking could facilitate in some way the development of a sophisticated military command and control system that was capable of withstanding a nuclear attack from the Soviet Union. This idea led the military to sponsor a system without a command center that would be destroyed by the enemy in case of attack. This was not a problem because the military also had the idea of a development of network technology that would permit the use of the system even if some parts were destroyed. The military had different concerns because they wanted to have a networking system that could serve different specialized military tasks; in fact, this concern incouraged the creation of a diverse system that allowed different networks to be incorporated.

The military seemed young Tony Starks, huh?

Yes the military did it’s part, but what about other developments?

The military-scientific complex shaped the Internet but also the American counterculture did its part in the 1980s. Basically the counterculture reconceived how the computer could be used to advance its vision of the future. In fact, its activists transformed it from a tool of a techno-elite into a creator of virtual communities, a sub-cultural playground and an agency of democracy.

That’s not it.

A third influence was a European welfarist tradition that created great public health and broadcasting systems. While the internet was born in the US, the world wide web was created by Tim Berners-Lee.

He was inspired by two fundamental ideas:

opening up access to a public good

bringing people into communion with each other

Berners-Lee had the desire not to promote the web through a private company because he thought it might trigger competition and lead the web to be divided into different domains. This would destroy his conception of a universal medium for sharing information.

Now my actual question is: did you really know all THIS? Because I did not.

Starting off, it was incredibile how the military thought of a way to use the network in order to keep their data secret but only knowledgeable among the people who actually had to know the facts; in fact there was a contract between the military and scientists in order to keep the situation a secret. We can call that era of internet WEB 1.0 and the one of this era WEB 2.0.

The Internet is a complete different world now, in which you can search things and probably have an opinion, even though at some point you couldn’t have that either, or at least you could give your opinion but it wouldn’t matter.

Unfortunately there is also another kind of web called the dark web, which are networks that use the Internet but require a specific kind of software, configurations and also authorizations to access. Also the internet has its dark side.

With the rise of social media the Internet completely changed. From what was a military experiment, it turned out to be a daily necessity for everyone: from searching important things such as news to also looking for memes or school-related articles. Not to mention also how the internet and social media became a platform that gave access to bullism or actually cyberbullism; apparently with the Internet things can get better but also worse.

If the old Internet could see where the new Internet is at, probably it would tear its hair off.

REFERENCES:

Curran, James. “The Internet of history: rethinking the internet’s past”, in Misunderstanding the Internet

Levine, Yasha. Surveillance Valley: The Secret Military History of the Internet

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Let’s Face the Music and Dance: Two Sad-Eyed Musicals by Herbert Ross by Nathaniel Thompson

If you polled critics or movie buffs about significant American film directors, it’s highly doubtful that Herbert Ross would appear anywhere close to the top 100. That’s not a slight against his abilities but rather the simple fact that he doesn’t fit the auteur idea of a director who puts an indelible stamp of authorship on every film he touches. Fortunately, you don’t have to be a great auteur to be a solid director—Hollywood is loaded with dozens of skilled craftsmen who were never lauded by the critical powers that be—and Ross fits the bill with a pretty astonishing run that kicked off with his underrated 1969 debut, a musical version of GOODBYE, MR. CHIPS, and continued all the way through, more or less, to at least STEEL MAGNOLIAS in 1989. There’s been a lot of discussion lately about how rare it is for directors to have a “hot streak” of more than four films in a row, but Ross managed to pull it off a couple of times over.

Somehow you also never hear of Ross cited as a significant director of musicals, though he dipped his toes in at least three times – or four if you count the dance-crazy FOOTLOOSE (’84), his biggest box office hit. You can see two of them in FilmStruck’s five-film spotlight on Ross, and it’s interesting to note how they snugly fit in with his recurring theme of nostalgia as both a soothing mental snuggly blanket and a dangerous pitfall that can blind you to the harsh realities of life if you aren’t careful. That also goes for his other third bona fide musical, FUNNY LADY (’75), which is also worth tracking down and far more interesting than most critics like to admit.

Now, as they like to say in school, let’s compare and contrast. GOODBYE, MR. CHIPS was an easy target when it opened among a slew of doomed Hollywood roadshow song-and-dance projects that went down in flames, most notably STAR! (’68) and PAINT YOUR WAGON (’69). No one seemed to hate it (after all, the film earned a couple of Oscar nominations and, for what it’s worth, snagged a Golden Globe for Peter O’Toole), but audiences were a lot more eager to see sexy ‘30s outlaws and counterculture motorcyclists than Vaseline-lensed odes to Hollywood’s musical tradition, so the odds were stacked against this one before it even opened. Luckily time has proven the strength of Ross’s film, an inventive and emotionally effective adaptation of James Hilton’s classic novel (earlier filmed as an Oscar-winning 1939 production starring Robert Donat).

I have to be upfront that I’m a little biased since I’m a sucker for just about anything with Petula Clark, but there’s an infectious charm to this film that makes the emotional punches land even harder. It’s clear that former choreographer Ross relished the opportunity to pull out all the stops here with a widescreen 70mm period film set over multiple eras, and a splashy score and book by John Williams and Leslie Bricusse, a luxury similar to what Bob Fosse would be afforded the same year with his colorful and often exhilarating big screen take on SWEET CHARITY (which has also amassed a dedicated fan following). Stepping in for a departed Richard Burton, O’Toole brings a sweetness and slightly dizzy sincerity to his part that pays dividends as his character ages through the film; you really believe his mannerisms and body language as he transforms through the various phases of Mr. Chips over the course of the running time. Just throw out any comparisons to the classic black-and-white version of the story and you’ll find this one has continued to age quite beautifully.

Though it was made only 12 years later, Ross’s PENNIES FROM HEAVEN (’81) might as well be from a different planet in terms of its target audience and philosophy. Once again, we have a big-budget musical revamp of a preexisting property, in this case an acclaimed Dennis Potter miniseries that originally aired on the BBC in 1978. It’s also a true MGM musical and the last legitimate gasp of the studio in that realm, which seems wistfully appropriate. Steve Martin (whose extensive musical talents are still often overlooked) and Bernadette Peters, a real-life coupe who had just starred in THE JERK (’79), teamed up again here for a film that’s anything but a comedy as Potter transposes his original London-set script to Great Depression-era Illinois. Otherwise the story’s the same, as traveling sheet music salesman Arthur Parker escapes from his dreary reality (including an unhappy marriage to the always welcome Jessica Harper) by drifting off into the starry-eyed tunes he hawks. After hooking up with schoolteacher Eileen (Peters), he’s subjected to several cruel twists of fate far removed from the optimism of his daydreams.

The mixture of bleak Midwestern tragedy and glitzy musical numbers is still a powerful one that distinguishes this film from its more scaled-down BBC presentation, but the overriding philosophy is the same: entertainment might be an easy way to escape for three minutes or a couple of hours but using it as a yardstick for reality is only going to ruin your life. It’s a message that moviegoers of the early ‘80s really, really didn’t want to hear and the film flopped at the box office. That’s a shame as it’s chock full of classic sequences, most notably Christopher Walken’s scene-stealing tap dance number as a charismatic pimp (a scene that was cut out wholesale when this used to run on commercial TV) and, my personal favorite, Martin and Peters miming the timeless FOLLOW THE FLEET (’36) performance of “Let’s Face the Music and Dance” by Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers. (Astaire’s very vocal disdain for this film probably didn’t help, but don’t let his opinion dissuade you from watching it.) Even more than GOODBYE, MR. CHIPS, Ross feels like a kid in a candy store here with rows of dancing chorines, instrument-playing school kids and an eye-popping array of glittering costumes. It’s the sort of film you never forget once you’ve seen it, and you don’t have to look much further than films like DANCER IN THE DARK (2000) or even the unflinchingly downbeat INTO THE WOODS (2014) to see how unexpected and potent its influence continues to be. Like much of Ross’s work, it’s a resilient and crafty little number that has a way of winning you over in ways you might never expect.

#FilmStruck#Herbert Ross#Goodbye Mr. Chips#Pennies From Heaven#Steve Martin#Peter O'Toole#Petula Clark#Bernadette Peters#musicals#StreamLine Blog#Nathaniel Thompson

35 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Domestic Cold War and Reagan’s California (1967-1975)

It got by George Washington

The ideas of justice, liberty, and equality

. . .

Ronald Reagan, it got by him

Hollyweird

Acted like a actor

Acted like a liberal

Acted like General Franco when he acted like governor of California

Now he acts like somebody might vote for him for president

-Gil Scott-Heron, “Bicentennial Blues,” The Mind of Gil Scott-Heron (1975)

Reagan’s California

Ronald Reagan is associated with many of the most fundamental changes that have taken place in American politics over the last five decades. The “Reagan Revolution” (along with Thatcherism, the UK’s counterpart) is often seen as being responsible for the neoliberal turn that American politics and economics have taken since the 1980s. Reagan ushered in anti-union and pro-business policies that fall under the banner of supply-side economics, or more euphemistically, “trickle-down economics.” Reagan also did his part to revolutionize the American security state. The Iran-Contra scandal, in which Reagan administration officials were caught selling arms to Iran (who was under an arms embargo) in order to fund the Nicaraguan anti-communist Contra fighting forces, went a long way in institutionalizing the use of private military contractors and defense companies.[1] Reagan accomplished all of this as the president of the United States, an office he held from 1981 to 1989.

A less examined portion of Reagan’s political career, but one in which he and his political associates also affected extensive political change, is his tenure as the governor of California. Reagan served two consecutive terms as the governor of California, from 1967 until 1975. The Watts riots in Los Angeles occurred two years prior to his first term in 1965. Thus, as a Republican, law-and-order governor, Reagan presided over some of the most tumultuous moments of California and the United States’ history. These include, but are not limited to:

1967 - Summer of Love; thousands of youths migrate from around the United States to California’s Bay Area to be a part of a burgeoning counterculture movement

June 6, 1968 - Assassination of Robert F. Kennedy; occurs roughly five years after his brother’s, John F. Kennedy’s assignation, three years after the assassination of Malcolm X, and just over two months after the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr.

January 17, 1969 – Black Panther shootout with rival United Slaves (US) organization; shootout left two Panthers (Bunchy Carter and John Huggins) dead, US and their leader Ron Karenga believed to possibly be opportunistically working with state and federal security apparatus to neutralize the Black Panther Party.

August 9, 1969 – Manson Family murders Sharon Tate and four others; Charles Manson and his white youth followers lead to association of the psychedelic, hippie and drug counterculture with violence.

December 9, 1969 – LAPD instigates an early morning shootout by initiating a surprise raid on the Los Angeles Black Panther Party headquarters; raid comes only 5 days after Fred Hampton was assassinated in Chicago by a similar early morning unannounced “raid”; Panthers survive shootout by shooting back and holding their ground until media and the public arrive to scene.

August 7, 1970 – Jonathan P. Jackson killed in attempt to kidnap and take hostages from a Marin County, California courtroom, which he planned to trade for the release of his brother and their transportation to a county supportive of the Black Panther Party;

August 21, 1971 – George Jackson, probably the most well-known face of California’s revolutionary prisoner movement, is killed by guards in San Quentin prison during an alleged escape attempt; controversy exists over the facts surrounding the escape attempt, particularly how he supposedly smuggled in a pistol without the guards seeing, as well as the circumstances of the guard’s gunshots that took his life.

December 16, 1971 – California Correctional Officers Association (CCOA) in conjunction with Attorney General Evelle Younger’s office attempt to frame Soledad psychiatrist, Dr. Frank Rundle (a self-ascribed “New Republic liberal”[2]) for two killings of Soledad guards after he publicly advocated for prison reform, especially for prisoners in need of mental health treatment; conspiracy is discovered because the prisoner (Tony Pewitt) who was used by the state to frame Rundle refused to go through with the plan and alerted him, at which point Rundle contacted private detectives and media.

1973-1975 – Rise and demise of the Symbionese Liberation Army; a Maoist group led by an escaped black convict, Donald DeFreeze, and comprised of majority white student radicals goes on a highly publicized string of violent acts in the name revolution, including the kidnapping of Patricia Hearst, the college-aged heir to the Hearst family fortune.

This small list of political violence during Reagan’s governorship is by no means exhaustive, but it does comprise many of the better known incidents. One trend that is clear is that as time went on, the radical left became associated with greater amounts of violence, both as the supposed aggressors and as recipients of state violence. All of this contributed to the sentiment that many participants in the 1960s and 1970s radical left today hold themselves, that America’s radical left was predisposed toward counterproductive and self-destructive violence. This violence soured the view of the radical left in the eyes of the general American public and led to defeat of the movement. The trend of increasing violence applies to all sects of the radical left—the black power movement, the youth student movement, hippies, Maoists, radical prisoners, and even “defectors” from wealthy families who ended up involved in radical left activities (like Patricia Hearst). The combined effect of all of this violence was the delegitimation and sundering of radical left politics.

Charles Manson was associated with the hippie youth counterculture.[3] His crimes marked a shift from the initial, positive, psychedelic Summer of Love to the mood after the Manson murders and into the 1970s which was much darker. By the time Manson was arrested, the psychedelic positivity associated with LSD in the late 1960s had been replaced by a heroin and amphetamine fueled paranoia and pessimism. In the case of the Black Panther Party, it is more evident that authorities were attempting to eliminate the organization and that instigating violence against the Panthers (such as the LAPD shootout) was a method toward this end.

The Symbionese Liberation Army (SLA) came along in the mid-1970s and seemed to synthesize these separate currents into one organization. The SLA was a self-described Maoist insurgency group headed by a black escaped prisoner (Donald DeFreeze) and composed of radical students from multiple ethnic backgrounds (but primarily middle class whites). The group kidnapped Patricia Heart and forced her to commit crimes with the organization, such as bank robbery and car theft. The SLA provided the final proof to the public that the radical left had devolved into something unnecessarily violent, shortsighted, and counterproductive. These are ideal circumstances for a conservative law and order governor to prosper. And prosper Reagan did. Reagan won two elections and chose not to run for a third term before eventually becoming the country’s president in 1980.

Amidst this period of sustained political violence and turmoil Governor Reagan greatly increased the power of domestic police and intelligence in the state of California. To be more specific, it appears that Reagan (with assistance from Richard Nixon’s presidential administration) ran a counterinsurgency program designed to neutralize and delegitimation the radical left opposition throughout the state. The term counterinsurgency, a term primarily associated America’s foreign military operations, is important here. While domestic police are, in theory, not supposed to care about private citizens’ political beliefs, military counterinsurgency doctrines are precisely concerned with the political beliefs of their targets. In fact, in a counterinsurgency warfare, elimination of an ideology may be seen as more important and vital than elimination of particular individuals and leaders.

This reality is ignored because of an American exceptionalist attitude and bias that tends to whitewash the nature of domestic intelligence practices and operations. This whitewashed view says the government security apparatus (from the federal agencies to local police) operates by different rules domestically than it does internationally. One way this manifests itself is in the idea that anyone who is victimized or killed by the domestic security apparatus deserved such treatment on some level, even if the public still widely condemns the action. It is understood that in modern warfare, beginning primarily with Vietnam, the United States and its allies assassinate important enemy officials outside of direct engagement and that these assassinations are carried out to hamper the enemy’s effectiveness (a macro consideration)—not in response to particular actions carried out by the individuals (a micro consideration). For example, the 2008 joint Israeli and U.S. car bomb assassination of Hezbollah’s Imad Mughniyah, known to be a particularly intelligent and effective military tactician, did not come in the course of combat, it was carried out clandestinely away from an active battlefield. The assassination received condemnation from some Western allies,[4] but the methodology was clear. Mughniyah was killed for simply being a highly skilled leader for the enemy. In the academic literature on counterterrorism and counterinsurgency, such tactics are vividly referred to as attempts at “leadership decapitation.” There is hesitation from domestic observers within the United States to ascribe such simple and undemocratic motivations for the repression (via assassination and incarceration) that the Black Panther Party and others faced, but the facts of the situation suggest that the Panthers faced a concerted leadership decapitation effort from the United States government, and much of this was executed by and through Reagan’s gubernatorial administration.

I argue that the sustained counterinsurgency operations against California’s radical leftists in the 1960s and 1970s have more in common with the American intelligence community’s counterinsurgency efforts overseas in theaters like Italy, Latin America, and Indochina (where the Vietnam War was raging) than they have in common with more sanitized narratives that take the purported actions and statements of groups like the SLA at face value. Historical investigation has shown that the Western powers, as well as lesser powers like the authoritarian Latin American regimes of the era, operated under the same general counterinsurgency doctrine. This doctrine was developed by a myriad of anti-communist hardliners from a variety of countries, but British, French, American, and former-Nazi intelligence and military personnel seem to have been key in the intellectual development of the doctrine. Declassified documents and information gathered from governmental and non-governmental investigations have revealed that a key element of this doctrine was that Western intelligence operatives ought to implicate communists (and the wider radical left) in terrorism and indiscriminate violence. The function of this violence would be to strengthen the existing status quo by discrediting the left and driving a scared and disoriented public into the arms of the state and its security apparatus. The existence of such activities in the so-called Second and Third Worlds are well established (Operation CONDOR in Latin America and the Phoenix Program in Vietnam and Indochina), but irrefutable evidence of similar tactics was discovered by Italian parliamentary investigators in the early 1990s. Italian investigators concluded that neo-fascist elements of the Italian state and security apparatus committed terrorist attacks in the 1960s through 1980s that were wrongly attributed to anarchists and communists, as well as clandestinely encouraging other terrorist attacks and forms of political violence.

There is an immense value to this type of inquiry. There is an obvious and inherent value in gaining a deeper understanding of how modern states (and private organizations) engage in repression and stamp out dissent. This ought to interest anyone with even a passing interest in radical, left, or anti-capitalist politics. Further, these tactics were deployed against non-revolutionary liberal reformists, not just radical leftists. Thus, this research should give anyone who is interested in genuine democracy, representative or otherwise, serious pause. This research also challenges existing narratives of the decline of the American radical left. By challenging the basis of California’s political violence of the 1960s and 1970s and suggesting that the state played a more prominent role in committing and encouraging violence than is commonly understood, one challenges the narrative that the radical left caused its own downfall by sliding toward violence. Such an investigation into American political violence of the 1960s and 1970s is overdue. I hope to spur such an investigation and conversation.