#but like. back to Dave McKean and Sandman

Text

also let's be honest I'm like 50% less interested in Things Neil Gaiman Makes if Dave McKean or Chris Riddell or Charles Vess aren't anywhere to be seen like come on man. what can I say. I'm an illustration guy.

#all the Neil Gaiman comics i give a shit about at least tangentially involve Dave McKean#Sandman. Signal to Noise. Arkham Asylum. That's it.#other than that also: McKean's Coraline is best Coraline. Mirrormask OBVIOUSLY.#and where Dave McKean isn't the best fit Chris Riddell usually is#his Coraline is also ok but not as good as McKean's bc McKean is right for the tone#however he MAKES the Graveyard Book and Fortunately The Milk#but like. back to Dave McKean and Sandman#did he ever do interior art for Sandman? he did not. and yet his artwork is definitionally Sandman#it and the lettering are the most utter aesthetic throughline#the interior art is hugely variable. Some of it is gorgeous (always loved the art for the Emperor Norton story and for Ramadan#and Brief Lives is really nicely and characteristics drawn)#and some is. not. (The Kindly Ones is fucking unreadable fight me)#and a lot is good but not to my taste (like. i think The Wake art is meh but that's. personal preference. it's objectively good comic art)#but like if I see a Dave McKean Sandman cover I'm like ah. sandman.#(this is why i am so lucky to have a full set of original singles)#(that means i have every McKean Sandman cover in hand including the ones that aren't in the trades)#(also have a signed McKean variant cover of Overture#no 1)#(i swear I'm not an annoying Comics Guy. I'm a trade paperback person i just love Dave McKean more than almost any other artist alive)

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

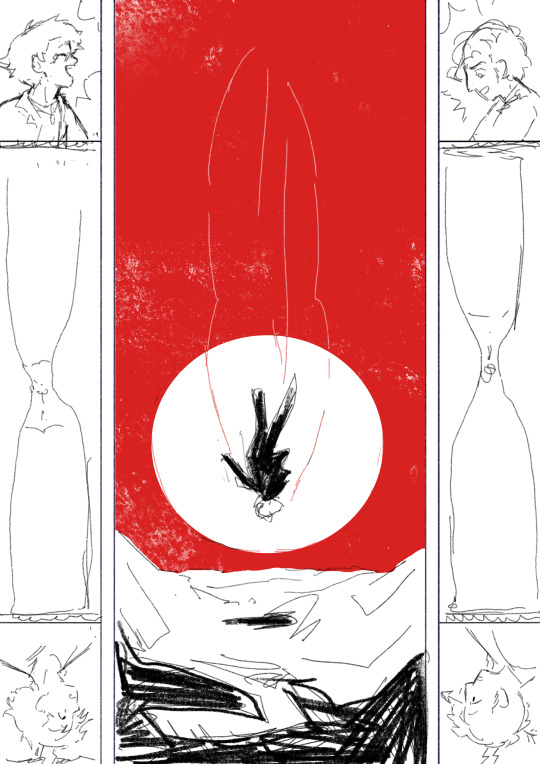

A Canary’s Final Flight

My piece for @trafficzine 4th edition! Get it for free here! 200 pages of excellent art and fics, incredible work from all participants and from the mods especially!! huge shoutout to the mods for real

Process notes under the cut! (I struggled a lot so it's a bit of a novel)

So the entire process was a Ride. I knew when I picked this prompt that I was going to have a hard time, because Jimmy’s final death had been illustrated a billion times over by extremely talented artists. But I had a Vision of the snapshot of the second before the impact, when everything is still but you know what’s about happen. It was very much inspired by the clip of Fog by Jabberwocky, bu the thing is, they have the advantage of all the build up of the fall, and that’s when the trouble started.

This was my first version, and obviously it wasn't working. And I was trying so hard, with so many iterations! Small wings, big wings, no wings, different poses, less backgrounds elements. I'd done compositions were everything seemed peaceful but something is Wrong, but it wasn't working this time.

So instead I focused on what rendering I'd like to do - I tried a painterly approach, for that visceral feeling, but it wasn't working either (but hey, I did keep the red sky, so, progress)

At this point I'd been doing back and forths for weeks and I was just as lost as at the start. Now that's my tip for people who make art of any kind, in situations like that, stop thinking about how you can make the best piece possible, and think about you can have fun with it (because when you aren't it's visible). And for that was, 1 - going back to using ink and pen nibs and doing way too detailed inking, and 2- looking at Dave McKean's covers for Sandman (which, funnily enough, was also a reference for my previous trafficzine piece)

And from there I was actually going somewhere! Between the jagged rocks, the red sky, and the increased verticality with the borders, I had hit the vibes I wanted.

I did some experimentation with the border, and even though I really liked the bad boys I drew they were taking too much away from the lonely desolation, so I actually used Red (Unecessary Redstone)'s idea of all of Jimmy's worldy's possessions scattered on the ground post impact, with the idea to make it looks like the central image is his grave being dug.

(and yes for a short amount of time the were supposed to be clock markings on the sun, but there was already enough going with the wings so I scrapped that) (also fun fact the reason why the wings aren't fully material but more ghostly is because my toddler cousin was watching me draw the very first draft and asked why he didn't just use his wings and i went :( so the wings are a metaphor now)

So from there I found a bunch of picture and took some myself, cut and assembled everything together, added shadows in all the appropriate places, and repainted some elements so that everything would look better intergrated (some of the wheats are basically 100% handpainted, the cardboard as well). This took a suprisingly long amount of time, but I was done!

Well I wasn't expecting to have that much to say, but I hope if you're still reading, it was at least interesting!

#trafficzine#limited life#limlife#limlife fanart#jimmy solidarity fanart#solidaritygaming#i forgot all the tags augh#curse of not posting often#mcyt fanart#mcyt#zine illustration#zines#my art

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

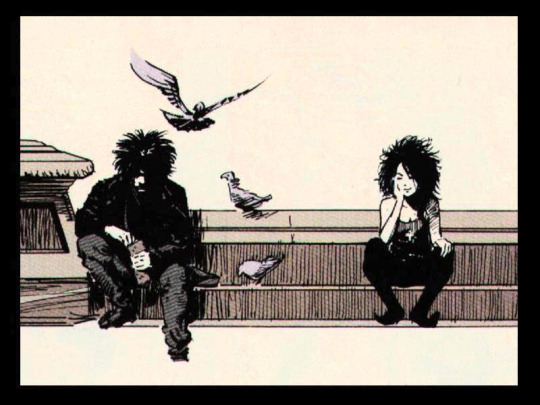

A guide for reading The Sandman: Part 3

“I said in my previous post (part 2 of this guide) that I covered everything related to Sandman that Neil Gaiman had an active part in, as a writer/scripter/creator. This is not... exact. There is one thing I have not talked about, the “Books of Magic” mini-series which was made by Neil Gaiman and features several of the Endless such as Death, Destiny and Dream. And if I have skipped it, it is because in this post I will cover everything you can consider a “spin-off” of the main Sandman bulk. And if you thought you had read everything related to The Sandman by just check-listing my previous posts, if you thought that with my two previous guides you would be over, oh you’re in for quite a surprise!

So... let’s begin. Given there is a LOT of spin-offs and a lot of the “Sandman extended universe” and a lot of Sandman works not done by Neil Gaiman, I’ll just cram a a few here, and another part in a fourth post later.

A) THE BIG SERIES

Let’s begin with the “big” series, as I call them - either big in size, in notoriety or in autonomy.

# The Dreaming. A 60-issues comic book of the 90s. NOT TO BE MISTAKEN WITH THE NEW “DREAMING” COMICS EVERYBODY TALKS ABOUT. The Dreaming was designed to be a pure Sandman spin-off, as in an anthology of various tales covering different characters and elements presented in The Sandman: you have stories about Cain and Abel, stories about Mad Hettie, stories about the Corinthian. You find back Matthew, and Eve, and Nuala, and other inhabitants of The Dreaming, and some of the Endless (such as occasional appearances of Destiny or Dream) - but it also ends up introducing a lot of new characters in The Sandman landscape.

Now, The Dreaming started out as an anthology series, as I said: there were several stories following each other, unrelated, just all taking place in The Sandman universe, but each done by a different writer and a different artist. Neil Gaiman was here of course, but not as a creator: he authorized the series, and he acted as a “creative consultant”. He suggested ideas to develop a character or a storyline to the new writers of the series, and he had the right to refuse or forbid any kind of script or idea that he didn’t like (something he actually never did, according to testimonies). The series was overseen by DC editor Alisa Kwitney, in collaboration with Neil Gaiman, and when the series hit issue 21, the two agreed a change needed to be done.

The series couldn’t stand strongly on its legs just being a series of Dreaming-related stories, especially since the models and structures of said stories started to become repetivie. It was about to turn into “The dream of the week”, and the new characters introduced were quickly dropped after their individual stories. So, starting with issue 22, “The Dreaming” became one long story about events happening in The Dreaming after the end of The Sandman (aka under Daniel’s “era”), with arcs and an internal chronology and plot twists - a big story that actually changed the way we knew The Dreaming. Originally co-written by Caitlin Kiernan and Peter Hogan, it quickly became Kiernan’s own product as Hogan left. Something quite of note: Dave McKean, the artist who did the covers of The Sandman, returned to make those of The Dreaming (and there is even a book that collects all of The Dreaming covers of his somewhere).

The series went up to sixty issues before being cancelled. Kiernan was heavily criticized for how her story changed the world of The Sandman and how she handled the character (which is a plague most of the spin-offs writers had to face, because readers always compare you to Neil Gaiman) ; and other spin-offs of The Sandman were much more popular. (But don’t worry, despite all the stress caused by it, Kiernan said she still has very fond memories of working on this comic).

One last note: The Dreaming is not actually “canon”. Well... technically it probably happened somewhere in one of the various parts of the Multiverse, but when Neil Gaiman returned to The Sandman (starting with Endless Nights and going on with all I covered in previous guides), he ignored the changes brought in The Dreaming, and similarly, more modern spin-offs (aka The Sandman Universe) also ignored the events of The Dreaming. So while they are a fun read and an “alternate universe”, the series actually doesn’t have any impact on the main series or on the Sandman works of Neil Gaiman. But its very existence was important to bring forward even more spin-offs to the extended Sandman universe (such as Sandman Presents or the Sandman Universe).

# Lucifer. This was the second notorious spin-off of The Sandman - and one of the series that was popular enough to get “The Dreaming” cancelled. You might know this comic as the “inspiration” and “basis” for the popular TV show Lucifer, but trust me, the two are actually VERY different. VERY VERY different. This 2000s series of 75 issues was created by Mike Carey (also known for “Crossing Midnight”, “The Unwritten” and his works on X-Men and Hellblazer) and, while taking place in The Sandman universe, it focuses entirely on Lucifer and what he is up to after the events of The Sandman. There is a deeper exploration of the working of angels, demons, Hell and God with a big G when it comes to The Sandman, with also a lot of new additions and creations by Carey. Unlike Kiernan’s work on “The Dreaming”, Carey’s creation was quite warmly received, hence why it managed to run for an equal number of issues as The Sandman’s original run.

(Apparently the series had a revival in 2015, following the huge reboot of the DC Comics as the New 52? But it is maybe not canon? I honestly only know of the original 2000s series, so I’ll leave this for your exploration).

# The Dead Boy Detectives.

Now this isn’t exactly one given series, but rather a pair of Sandman characters that became an iconic duo hoping from one series to another: After the end of The Sandman, they reappeared, written by Neil Gaiman himself, for a DC crossover event he participated to: “The Children’s Crusade”, a crossover story of the DC comics. After this, they reappeared in several other Sandman-related comics, be it the “Sandman Presents” ensemble, the “Books of Magic” series or the “Winter’s Edge” comics (in fact the Children’s Crusade series ended up crossing with the Books of Magic in the “Arcana Annuals” or “Arcana: The Books of Magic”). Anyway, after a last apparition in the well-loved “Vertigo Anthology” series, and the release of “Sandman: Overture”, they finally got their own series entirely dedicated to them: “Dead Boy Detectives”, twelve issues published in 2014.

EDIT: Now that I am proof-reading this in 2014 I have to precise that, in the wake of the success of the tv series adaptation of “Sandman”, there is an upcoming television series for “Dead Boy Detectives” about to be released soon.

# The Books of Magic.

The Books of Magic was originally a four-issues miniseries created by Neil Gaiman due to DC’s desire to explore and present more of its “magical” and “mystical” side. Published between 1900 and 1991, this mini-series was basically a huge exploration of the DC universe and the various forms of magic, witches and wizards existing in it through the eyes of Timothy Hunter, a young English boy who just learned that magic is real and that he is destined to become the greatest wizard of all times... Due to being both a geographical and historical exploration of the DC world, several elements of The Sandman appear in this mini-series: Death makes an appearance, Hunter visits The Dreaming, and Titania with her Faerie realm is also one of Hunter’s destinations. (This series is especially important because one character in it reappears in Sandman: Overture).

It was just supposed to be a limited mini-series, but it got a huge success. A success big enough for it to get some sequel mini-series : such as “Mister E.”, a non Gaiman-related miniseries which continues the events of “Books of Magic”, or “The Children’s Crusade”, the crossover I talked about above. “The Children’s Crusade” got much more tangled with the world of the Books of Magic thanks to an Annual that focused much more on Timothy, the famous “Arcana” stories (Arcana: The Books of Magic annual, technically part of The Children’s Crusade series).

And it got big and popular enough for “The Books of Magic” to being released and published as its own, ongoing series developping the events described previously. Starting in 1994, this second Books of Magic series was done by John Ney Rieber, who was the one tasked with creating the “Arcana” story - which is why the Arcana story is a sort of prequel/introduction to this series. Rieber worked on “The Books of Magic” series until 1997 - at which point he decided to quit. You see, he had grown quite a distate and dislike of Timothy as a character, and he didn’t want to work on this series anymore. It however kept going: it was decided that the series’ artist, Peter Gross, who was following Timothy’s adventures since the Arcana, would take on writing for the rest of the series - and he brought the series up to its last and final issue, issue 75. Yep, the exact same number of issues The Sandman and Lucifer had. (I insist on the difference between writers, because some people felt and discussed the change of narration between Rieber’s work and Gross’ work).

I said “The Dreaming” was popular - I said “Lucifer” was even more popular. Well “The Books of Magic” was EVEN more popular. It was so big it spawned its own spin-offs. “The Books of Faerie”, “The Names of Magic”, “Hunter: The Age of Magic”... Hell, the world of “The Books of Magic” deserves its own guide. But hey - you might wonder “What about Neil Gaiman? He created the original mini-series, he wrote parts of The Children’s Crusade, what was his part in this new series?”. Well... none. You will see his name printed in the Arcana Annual and in the first half of the Books of Magic (volume 2) comics, under “creative consultant”. But in truth, as he latter revealed, he had no actual role in the creation of these comics. He had suggestions and ideas for Arcana - but when he tried to give them it was “too late” and no modification could be done. The same lack of power appeared during the ongoing series: he couldn’t give any ideas, didn’t had any influence, and even if he made suggestions they never manifested in the comics. All of this ending up with him leaving the comic at the same time as Rieber - with issue 50.

(There’s also a very funny thing with “Harry Potter”, but I’ll let you discover it on your own).

# Sandman Mystery Theater

I already talked about this series in the part 2 of this guide, so I’ll try to be quick. Before Neil Gaiman’s The Sandman, there were several “Sandmen” super-heroes, the first and oldest of them being Wesley Dodds, starting with the original “Adventure Comics” back in the 30s. He had his run and his series in the Golden Age of comics, and then was slowly forgotten and pushed away as a minor character - until he reappeard in Neil Gaiman’s “The Sandman”, as the “replacement” the world tried to create to fill the absence of the real Sandman, Dream of the Endless.

After The Sandman ended, DC decided to ride on the newly gained popularity of Wesley Dodds, and resurrected him for a new comic: “Sandman Mystery Theater”, running for 70 issues in the 90s and exploring in a film noir-like setting the adventures of this 30s Batman-like vigilante. The comic even managed to have a crossover with “The Sandman” under the shape of a one-shot special comic: “Sandman Midnight Theater”.

Okay, I won’t lie to you - I hadn’t planned for this post to be so long. I only covered half of what I wanted to talk about - but honestly, The Sandman “extended universe” is HUGE. Really. You’ll need years and years to read everything. So I’ll keep the rest of the spin-offs and extended universe for a part 4 and a part 5.

(As you can also note, I myself do not know everything about all of those spin-off comics. I read quite a few - Lucifer, some parts of The Dreaming, I read the Books of Magic series, but I also have to rely a bit on information I learned through searching the Internet, like everybody else - so I strongly advise you to not take this post at face value. Go read the comics yourself, search out each title, each artist, each writer, read the issues and discover this world on your own. This is just a stitched-together map. The wonders await.)

#the sandman#sandman#reading#guide#spin offs#spin-off#neil gaiman#lucifer#books of magic#dead boy detectives#the dreaming#the endless#timothy hunter

150 notes

·

View notes

Text

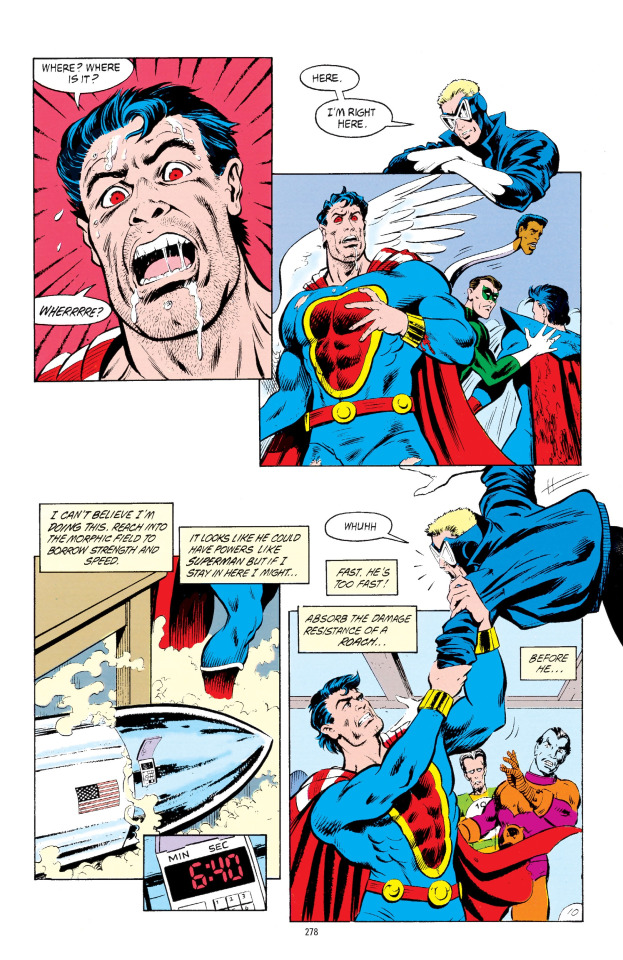

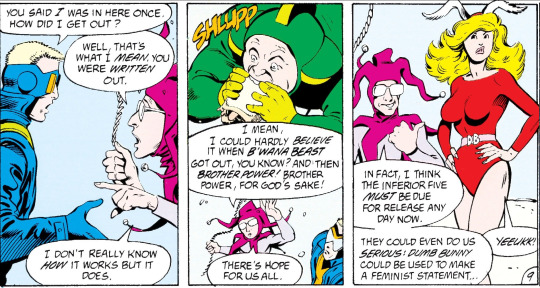

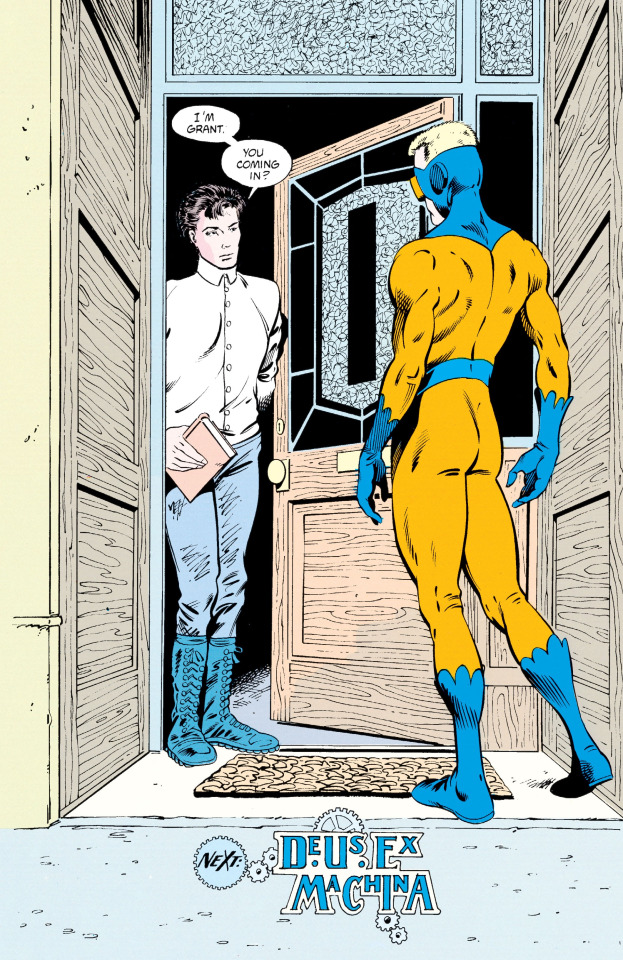

Comics Comints 3: Animal Man

Previously on Comics Comments: [The Incal] [Solo Levelling]. (Yeah this name is kind of terrible isn’t it? Part of me is like ‘for god’s sake change it’ and part of me is like ‘commit to the bit’.)

I think you could say I tend to like three different sources of comic. One is webcomics. The second is manga (and also manhwa). The third? Comics written by a wizard in the 1980s.

You see, most of the real ‘classic’ comics from this period are by some sort of wizard. Alan Moore? Famously a magician and really looks the part. Grant Morrison? Chaos magician. Alejandro Jodorowsky? Read the last first post in this series lmao.

It’s not actually all that surprising since comics are an incredibly densely symbolic medium which give you a pretty direct line of attack on the collective unconscious, if you believe in that. Being a wizard is probably pretty good training for writing interesting comics. Or maybe Alan Moore’s success just kicked off a fad of trying to find more British wizards to move comics off the shells at DC - pretty much Morrison’s own account of their introduction into the world of comics.

And that brings us to...

Animal Man

(1988-95, written by Grant Morrison, pencilled Chas Truog, Tom Grummett and Paris Cullins, inked Doug Hazlewood, Mark McKenna, Steve Montano and Mark Farmer, coloured Tatjana Wood and Helen Vesik, lettered by John Costanza and Janice Chiang, covers illustrated by Brian Bolland... phew...)

So. Animal Man! Basically the story as Morrison tells it in the intro to the collected edition is...

In 1987, at the height of the critical acclaim for Alan Moore’s work on SWAMP THING and WATCHMEN, DC Comics dispatched a band of troubleshooters on what is quaintly termed a “headhunting mission” to the United Kingdom. The brief was to turn up the stones and see if there weren’t any more cranky Brit authors who might be able to work wonders with some of hte dusty old characters languishing in DC’s back catalogue. As one of those who received the call that year, I had no idea who I might dig up and revamp. On the Glasgow to London train, however, my feverishly overstressed brain at last lighted upon Animal Man. This minor character from the pages of STRANGE ADVENTURES in the ‘60s had always, for heaven only knows what murky reasons, fascinated me and, as the train chugged through a picturesque language of Tudor houses and smiling bobbies on bicycles, I began to put together a scenario involving an out-of-work, married-with-children third-rate superhero who becomes involved with animal rights issues and finds his true vocation in life.

You can read the full introduction here. It’s pretty funny.

In fact, Morrison is leaving out a little of the story. The ‘headhunting mission’ took place after Alan Moore decisively cut ties with DC over issues related to royalties (particularly for merchandising) and a proposed age-rating system. He stopped writing for them after finishing the last few issues of V for Vendetta, and DC went looking for someone new to fill his niche of ‘left-wing British guy, good at prose, wizard’. Along with Morrison, they found...

Jamie Delano, who was approached by DC as the writer of the Swamp Thing spin off Hellblazer; Neil Gaiman and Dave McKean, who collaborated on the Black Orchid limited series, as well as the famous and acclaimed Sandman; Peter Milligan, who launched a new Shade, the Changing Man series; and Scottish creator Grant Morrison, whose pitch of an Animal Man series was approved. Later British creators to work on American comics include Mark Millar, Warren Ellis, Garth Ennis and Paul Jenkins.

This also comes in a time when American comics are getting more and more literary aspirations: complex characterisation, more naturalistic dialogue, less emphasis on superheroes. Which can perhaps also be attributed to Alan Moore. The ‘British invasion’ might be compared with the rise of gekiga in Japan in the 60s and 70s, although here the change was happening not in alternative magazines like Garo but the most mainstream comics. Putting in a pin in that, because I need to learn more about this period.

I came to Animal Man knowing really only one thing: that it gets increasingly metafictional, culminating in an arc where the protagonist goes and meets Grant Morrison themself. This does indeed happen and it’s cool! But before that a bunch of other stuff has to happen to set up the thematic significance of this metafiction...

What follows: a lot of art and story breakdown.

Morrison is a very interesting figure who I’d like to learn a lot more about. I thought of them as another example of the ‘spend years making sequential art instead of transitioning’ archetype, but it seems maybe a little more complicated than that - I think I need to do more research before I try and say anything definitive about the many noticeable ways trans girls figure in the imagination of comics from this period, and it doesn’t factor much in Animal Man compared to say Doom Patrol.

Indeed, main character Buddy is an almost parodically Normal Dad, a blonde white man living in an American suburban house with a white picket fence and... well, 2 children, not 2.5, but you know.

Into this world comes all sorts of weird stuff because it’s a Grant Morrison comic, and a lot of the humour in the earlier parts of the comic comes from the idea of shining a look at the fringes of the DC universe away from the central superhero battles, with a local low-tier superhero making TV appearances and becoming a minor celebrity. I think ‘everyday life in a world where superheroes are real’ has been done a lot since then, but it’s done well here. Being a superhero for Buddy starts out as just a day job; obscure superhero teams from Morrison’s encyclopedic knowledge of DC comics history are made into obscure superhero teams in-universe as well.

I don’t read American comics nearly as often as I read manga and webcomics - working on filling in the gaps there - so it’s hard for me to comment on Truog’s art in contrast to other comics. Which means what strikes me is probably more traits of ‘American Comics’ than this one specifically, but what ho...

The immediate thing I noticed is the immense anatomical precision, particularly when it comes to drawing muscles - something I’d also been struggling with at the time I read it so I was paying attention lol. Peter Chung made an interesting remark in an interview which I’ll quote here...

I think a lot of illustrators realize—and you see this a lot in American comics as well—that if you draw costumes realistically, it's very difficult. You end up spending all your time trying to create believable drapery. So the tendency is to draw skin-tight costumes that mold around the body. This allows you to use the body more. You see this with classical sculpture, and dancers. You try to use the expressive qualities of the human body more—that's why sculptors prefer to work with nudes, as opposed to trying to make the clothing look accurate. Otherwise you end up concentrating on the clothing and not the person.

Fairly early on, Animal Man’s outfit is updated to include a leather jacket, and there’s a solid sense of how to handle the cloth. Here’s an action scene from fairly early on with Buddy fighting against a rat monster created by the tragic villain B’wana Beast (more on him in a bit)...

You can see how the cloth stretches at the elbow and bunches up on the inside fold. This also shows a few other aspects of the art: the shading is completely carried by hatching in the linework, with the colours being flat, either pastel or highly saturated. I think this is in part a limitation of the printing technologies of the time. There’s occasional use of screentone, as you can see on the top right panel there (which downscaling has turned into a moiré pattern...)

In comparison to manga, beyond the general differences in character design, it’s interesting to see what’s different in how action scenes are conveyed. The panelling is generally very regular and rectangular, but there will occasionally be layouts with figures overlapping the border. Some of the ways of conveying motion, like dynamic unbalanced poses, or replacing lines with perpendicular hatching, is also widely used in manga; some aren’t, such as the motion arcs you can see in the page above. There usually isn’t a lot of exaggeration or extreme perspective distortion.

I think the colouring weakens it. The colours mostly serve to separate out different volumes, but they don’t really convey much in their own right. Out of curiosity, I tried putting the page above through desaturate and threshold filters to see what it would look like uncoloured. Here’s a threshold, which is what the inked page would look like...

and here’s a desaturate, which replaces the colours with pure value:

So you can see having some values to separate different elements helps, but honestly I think I prefer it desaturated lol. Still, it’s much better than the overly rendered hyper-contrast style that became popular a decade later.

The other big thing that’s different from what I’m used to in manga is the large amount of narration accompanying panels, typically but not always first-person. This is apparently something Alan Moore is responsible for establishing with V for Vendetta. I think the potential drawback with this approach is that your eyes may go straight for the text boxes, and skip the drawings entirely.

There are absolutely good sequences though, such as when Buddy and his friend the physicist

Despite these small complaints, the art generally works very well. Where it gets interesting is later in the comic when things start to get very meta, so you get a character’s deterioriation represented by using unfinished art (sketches or uninked drawings), and later messing with the formal elements like panel borders. There’s a sequence where a highly advanced Buddy fights an evil version of Superman from another timeline during a massive reality breakdown provoked by a character who is aware of all the discarded storylines and timelines in the DC universe and wants to save them, and thus you get pages like this:

Animal Man’s villains are rarely ever especially villainous, and the tone of a lot of the earlier stories is Buddy finding out about the situation and trying to prevent a tragic outcome and usually failing. Morrison used the comic to some degree to soapbox for animal rights, with early arcs dealing with animal experimentation labs and sadistic dolphin hunters. At one point he even pops by the UK to help out some hunt sabs. But it’s more using this as a source for stories than something purely didactic, and leans into conflicts like Buddy’s ambivalence when his ecoterrorist allies kill a firefighter during an attack on an animal lab as part of a broader arc of his life going to shit; he is, superhero or not, just one man who gets swept up in larger events most of the time.

Speaking of larger events, Morrison’s run on Animal Man coincided with one of DC’s periodic massive crossover events called uhh (*looks up*) Invasion!. Basically a bunch of aliens show up, so Buddy’s helping fight them; then off-screen a ‘gene bomb’ goes off which scrambles Buddy’s powers. (This also played into Morrison’s run on Doom Patrol, which I’m still reading at the moment, so more on that in the future!) The storylines associated with this event - one about an alien artist who wants to terraform the Earth, the other about a washed-up suicidal supervillain - are both good, and ‘aliens show up’ is really not far outside the usual sort of things that happen in Animal Man, but it’s funny that Grant Morrison, at the time ‘just’ an up-and-coming new writer at DC comics, is now probably the only reason that this whole event is still remembered in 2022.

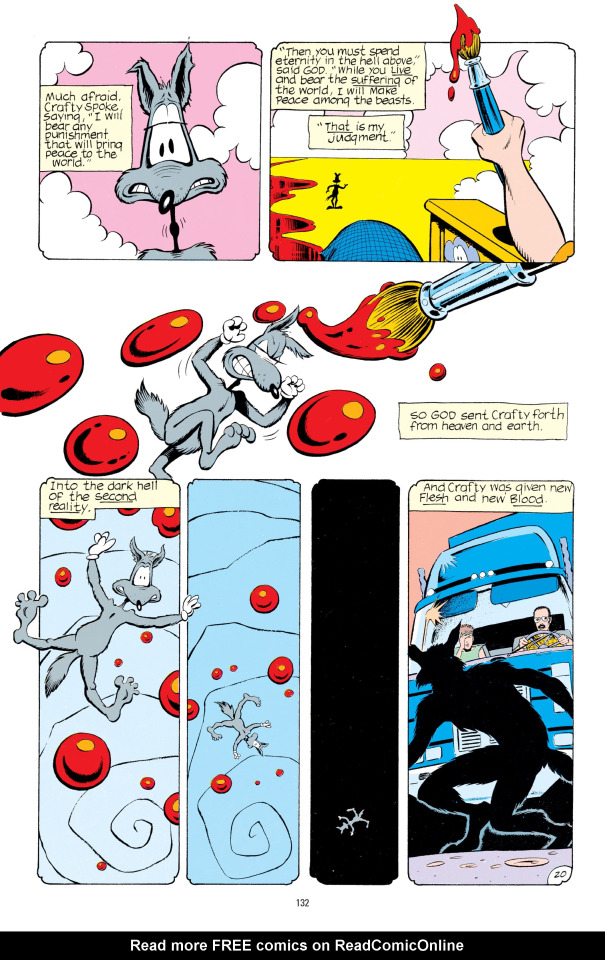

Anyway, let’s get into the metafiction stuff. The story is full of DC deep cuts, and Morrison seems to be very interested in how fictional characters are constructed, how they relate to their readers, how their stories are affected by the outside world...

The first movement in this direction is the story about Wile E. Coyote, which sees him rebel against God for creating a life of ceaseless violence for cartoon animals - only to be punished by incarnating him as a werewolf in the real world. Over the course of that story, Wile E. Crafty is run over, shot, crushed, and blown up, becoming a kind of Jesus-like figure whose suffering is supposed to save the animals. It’s a wonderfully batshit idea, and it works well in context - apparently this comic sold like mad so Morrison was encouraged to take it further. Animal Man’s role in this story - as in quite a lot of stories - is to witness Crafty’s death.

Thus over the course of Animal Man, we encounter a pair of aliens who find that the general trends in comic writing of the day - the emphasis on more complex characterisation for example - is increasingly straining the fabric of fictional reality...

The aliens stage an intervention to try and use Buddy’s memories to repair the timeline (or something??), but this ends up unleashing more chaos down the line, as more and more characters start attaining a fourth-wall breaking awareness. The next arc sets up some unexplained weirdness: a strange ghostly figure of Buddy attempts to communicate with his family, while meanwhile we’re introduced to the character of Highwater, a Native physicist who’s drawn into the mystery of an Arkham Asylum patient who seems to (for our outside eyes) have fourth-wall breaking knowledge.

So after the incident with the aliens, Buddy meets up with Highwater, and they go into the desert and have a peyote trip which leads to some fun imagery, hero gets power up. Meanwhile, government/corporate goons kill Buddy’s family. He gets back, and we find out the cause of the ghostly Buddy: distraught, he tries to time travel back to save them, but when his means of time travel doesn’t make that possible. The guy from Arkham Asylum meanwhile summons a bunch of DC characters from various discarded storylines and alternate universes; the aliens intervene, and Highwater ends up sealing it all off again, in the process becoming a mute Arkham inmate.

Buddy demands answers from the aliens, but they peace out; nevertheless he finds a strange door which takes him to a metafictional plane where he can - much like good old Crafty! - go and demand explanation from his creator. He soon finds discarded fictional characters in a realm where nothing can form stories, and is given a dying monkey with a typewriter that’s writing the comics script, and instructed to carry the monkey to the mythical city of ‘Formation’. (So I guess it’s still kind of animal related!)

But like all the other people Buddy couldn’t save, the monkey dies, and his journey takes him back to the start. After all this he finally gets to meet Grant Morrison!

The final issue has Morrison talking to both Buddy and the reader - giving acknowledgements, telling the story of their childhood imaginary friend Foxy, and explaining the craft of comics-making to Buddy and musing on the differences between comics life and real life.

Which is a fun little dialogue, because while it is drawing our attention to the constructed and arbitrary nature of everything in the story, it also at the same time has to function as a story. Buddy’s reactions - panicked incomprehension, questioning - have to continue to feel natural. Even though the comic is turning to us and saying ‘this man is fake’, it does its level best to cue us to think he’s real.

I like metafiction, but after you’ve handled the ‘character discovers they’re fictional’ scene, you need to figure out what it’s actually for. In this case, it’s part of the comic’s general theme of powerlessness and futility. Here’s the key page:

...which literally leads to a panel where Morrison turns to the camera and tells you to join PETA, something that hasn’t aged especially well. Morrison agonises a bit over why we use real death and suffering as entertainment - why they’d think about using their own cat’s death as material for this story - and then leaves, resurrecting Buddy’s family on the final panel.

So! Long summary over (thanks for bearing with me, I wanted to get it all straight in my head).

At this point, ‘fictional characters discover they are fictional’ is a pretty heavily done narrative, so you have to have some kind of very strong reason to use the device. I think that was way less true in the 80s - Italo Calvino’s novel If on a winters night a traveler was only published ‘79 after all!

In this case, its use is to provide a little reflective monologue on 1. living in a cruel and nihilistic world, in contrast to fictional characters who have a creator they can confront 2. Morrison’s position as an outside writer being pulled into the vast machine of the DC universe. Their intervention is... an interesting kind of critical, seeking to update rather than simply write out dubious past storylines, so the story acts as a kind of critical commentary on its predecessors. This is most apparent in one storyline which sees the old character B’wana Beast, a Tarzan-like figure who gets animal powers from a special helmet and is known as the ‘White God’, passing on his powers to a Black anti-apartheid activist. A lot of others simply deal with nostalgia, getting older, the world moving on and becoming more complicated.

Morrison describes their final storyline as an anticlimax. Which like... on the one hand, how could it possibly be? Buddy has uncovered the truth that no character in the setting can know. But on the other hand, by heavily emphasising everything is arbitrary, it does indeed dismantle the tension; there is no way it could be anything other than a final storyline.

Buddy spends much of his narrative under Morrison being unable to do more than stand by as terrible things happen around him. He tries extremely hard to be caring and empathetic, and this is often appreciated but rarely enough to save anyone. In the end he ‘realises’ that ‘he’ has even less power than that - he’s just an instrument of Morrison and whichever next writer (who would apparently choose to turn it into a story about quantum mechanical weirdness, but I stopped at the end of Morrison’s run) so not only are his efforts futile, even his motivation is also not under his control. All pretty solid as far as ‘pseudo-existential’ stories (in Buddy’s words) go.

And yet, as Morrison notes in their conversation, ‘Buddy’ will likely outlive Morrison themselves. To elaborate on that, we can see the figure of ‘Buddy’ conjured in our minds by the prompt of this book lasting as long as it continues to be printed, read, and iterated on - a meme, egregore, etc. etc.. This is the very hollow form of ‘life’ given to dead people who pass into memory, but it isn’t nothing; to create a character who’s not forgotten is quite an achievement.

Morrison’s theme of limited, even disabled characters for whom things never seem to go quite right is the whole impetus of Doom Patrol, so I guess I’ll pick up this thread when I finish digesting that one. Even so early in their career, they’re a very witty writer with a real knack for coming up with compelling, thematic scenarios and convincing characterisation. (Morrison had been writing comics in the UK for 5-6 years before that, so it’s hardly like this is the first time they wrote for a comic, but they were still younger than me at the point they began Animal Man.)

All in all, Animal Man is a compelling story that still holds up very well in 2022. If you want to read it, ComicExtra has the most complete collection of scans I found - scroll down to the 30th anniversary deluxe edition, which is annoyingly uploaded in reverse order.

Next up we’ll be doing a manga! I recently caught up with the absolutely delightful Witch Hat Atelier by Kamome Shirohama, and I can’t wait to dig into all the brilliant techniques she’s using in the art of this manga. See you then.

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

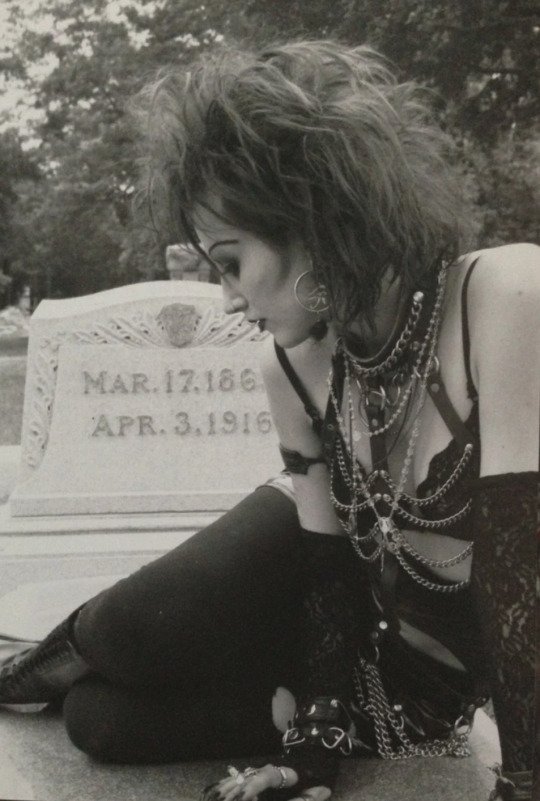

Cinamon Hadley - the Inspiration for Death of the Endless

Cinamon Hadley, the inspiration for the character design of Neil Gaiman’s Death of The Endless featured in his Sandman comics, passed away in 2018. Hadley’s influence on goth fashion and culture cannot be overstated.

“Death is the only major character whose visuals didn’t spring from me; that credit goes to Mike Dringenberg. In my original Sandman outline, I suggested Death look like rock star Nico in 1968, with the perfect cheekbones and perfect face she has on the cover of her Chelsea Girl album.

But Mike Dringenberg had his own ideas, so he sent me a drawing based on a woman he knew named Cinamon Hadley — the drawing that was later printed in Sandman 11 — and I looked at it and had the immediate reaction of, “Wow. That’s really cool.” Later that day, Dave McKean and I went to dinner in Chelsea at the My Old Dutch Pancake House and the waitress who served us was a kind of vision. She was American, had long black hair, was dressed entirely in black — black jeans, T-shirt, etc. — and wore a big silver ankh on a silver necklace. And she looked exactly like Mike Dringenberg’s drawing of Death.” - Neil Gaiman

In an interview originally published in part in her book Some Wear Leather, Some Wear Lace: The Worldwide Compendium of Postpunk and Goth in the 1980s, Andi Harriman interviewed Cinamon on what her style inspirations were, and on how Mike Dringenberg utilized her for his design of Death:

When did you first enter the scene? What attracted you to it?

“I was a ballerina and grew up on the stage. What attracted me to the deathrock scene was, it was like theatre – make-up, costumes... oh and dancing! You could be so creative with hair, makeup and clothes. And I’m a very creative individual. I designed and made most of my clothes-not only was I poor, but I had specific ideas of what I wanted to wear. I didn’t enter the scene until late ’87. I was 18. I dyed my hair black, bought black liquid eye liner, and bought my first pack of cigarettes-camel lights hard pack. Lol. I heard about a dance club in Salt Lake called the Palladium. I put my ballet stage make-up on, my little black outfit and teased my hair as big as I could get it and went to the club. I was in awe. I felt so at home, everyone was nice to me and I thought everyone was so “cool”. I decided this was the world I wanted to be in. I copied Patricia Morrison’s hair from Sisters of Mercy!”

Who inspired your look? Was there a specific person?

“I wasn’t really influenced by any specific person-except my big hair-it was more; I saw people in lots of black and lots of eyeliner. I would just start out with my Maybeline liquid eye liner and just start drawing. I often didn’t know what I was going to do. I really like the Egyptian makeup, I guess actually I was influenced by King Tutankhamen -a photo used in the comic has this makeup. But, there really isn’t anything original- someone somewhere has done it or thought about doing it. I thought I was so creative, drawing a big spiderweb on my face and gluing a little plastic spider in the center—yeah-well, it had already been done. Now for the infamous swirl under Death’s eye. That was a result of one of my little drawing sessions on my face. Now I see it everywhere. It’s kind of neat.”

How did you get involved with Neil Gaiman?

“Mike Dringenberg, the original artist for the Sandman, was a good friend of mine. He asked me one day if he could use me as a character for a comic book. I said sure. I didn’t know anything about comics and I didn’t know it was even anything special. I certainly had no idea it would be what it is now. Funny story... About three years after Mike asked me if he could use my likeness, I was living in Houston, having moved from Salt Lake City, and I was at a friend’s house. My friend told me his favorite comic was the Sandman and showed me an issue. When I opened it I saw a picture of myself staring back at me. (It was one of the 2 photographs actually used and just inked over). I said ”oh my God, that’s me!” I had no idea I was in the Sandman, and I had even forgotten about being asked by Mike to use me as the model.”

MORE PICTURES HERE!

#Sandman#Death#Character Design#goth#goth fashion in the 80s and 90s#(not my article! it's from post-punk.com! I just thought it was super neat and couldn't find it on tumblr)

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

"The inspiration for his clothes came from a print in a book of Japanese design, of a black kimono, with yellow markings at the bottom which looked vaguely like flames; and also from my desire to write a character I could have a certain amount of sympathy with. (As I wouldn't wear a costume, I couldn't imagine him wanting to wear one. And seeing that the greater part of my wardrobe is black [it's a sensible colour. It goes with anything. Well, anything black] then his taste in clothes echoed mine on that score as well.)"

"Fast forward to January 1988. Karen [Berger]'s back in England for a few days. Dave McKean, Karen and I met in London, and wound up in The Worst French Restaurant In Soho for dinner (it had a pianist who knew the first three bars of at least two songs, the ugliest paintings you've ever seen on the wall, and a waitress who spoke no known language. The food took over two hours to come, and was neither what we had ordered, nor warm, nor edible)."

"Rereading these stories today I must confess I find many of them awkward and ungainly, although even the clumsiest of them has something - a phrase, perhaps, or an idea, or an image I'm still proud of."

--- snippets I found interesting from the Afterword to The Sandman, volume 1: Preludes & Nocturnes by Neil Gaiman, in June 1991.

2 notes

·

View notes

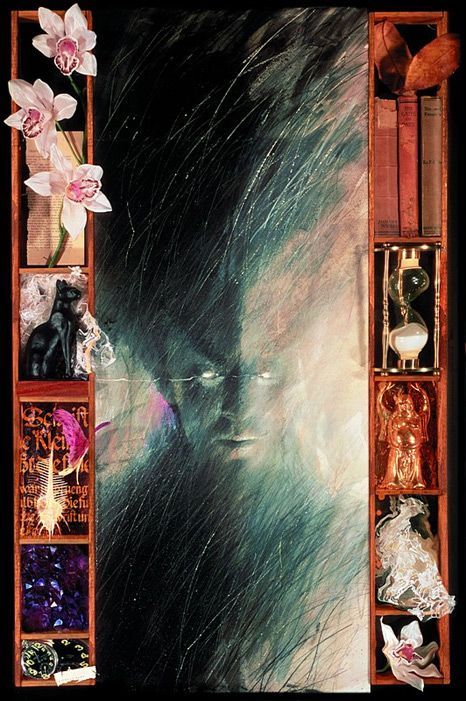

Photo

I’m running out of ways to say how lucky I feel to have dream projects like this come across my desk. Here’s my variant cover for the collected nightmare country vol1 hardcover, after Dave McKean’s Dream Country cover from way back in 1990. I’ll just say this one means a lot to me. Thanks as always to editors @whattheshea and @logovisual for being the best at what they do. . . . . . . #sandman #thecorinthian #toothsome #surrealcollage #illustration #comiccover #nightnight https://www.instagram.com/p/Cl1L5HWOM95/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

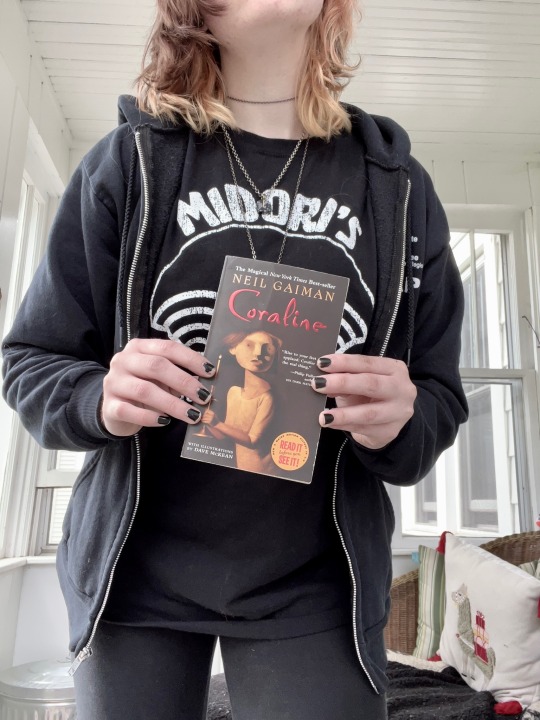

When did I start reading Neil Gaiman?

If I'm being honest, I didn’t REALLY start reading Neil Gaiman’s books until last year. After talking with a friend of mine I realized I really hadn’t read enough of his work to call myself a true fan.

I had read 1.5 books of his. The .5 is for me getting halfway through The Graveyard Book in high school. No one asked for my reading history, but here it is!

I actually have the original receipt from my first Gaiman book: 02.24.2011. I would have been 12 when I bought my copy of Coraline. I got it from an independent bookstore called Dreamhaven because at the time I had just seen the Coraline movie! And the book? It was so amazing and so great and actually ACTUALLY scared me, which I loved.

Instead of getting into Neil Gaiman’s other books, I hunted down books with pictures by the illustrator of Coraline: Dave McKean. Queue my obsession with this artists for the next few years.

In high school, I saw a copy of The Graveyard Book at a children’s bookshop, The Wild Rumpus. I bought it with my allowance because, once again, Dave McKean. I barely made the association that Neil Gaiman wrote this book, too. I got halfway through this masterpiece before quitting. At the time, a friend of mine had died very young and tragically and I was so distraught that I couldn’t bear to read a book with ghosts and graveyards. I didn’t pick the book up again until 2021.

In the summer/fall of 2021 my friend J mentioned Neil Gaiman and I said “he’s one of my favorite authors” and when I was asked which books I had read… well, only 1.5. But those books had such a profound impact on me that just 1.5 books made him one of my favorite authors (plus his association with Dave McKean, one of my favorite artists).

After creating a list of Gaiman books I scrounged, I bought, I dug, I bargained, and I started creating my own library filled with his books. Well, the library consists of 1.5 (ironic, right?) cubbies in my bookshelf. I read M is for Magic, I read The Ocean at the End of the Lane, I read so much!

(Side note: I tried reading The Ocean at the End of the Lane once in high school because a girl I liked swore by it.)

I started reading The Sandman, and eventually, I read The Graveyard Book again, which was such a profoundly beautiful and wonderful experience, I wish I had finished it in high school. I feel like it was a book I needed at that time and I was so sad and scarred to see it. It was a book where you find yourself hugging it to your chest and breathing in and out to know you’re alive.

Earlier this year I had the amazing opportunity to see Neil Gaiman for an evening of readings, Q&A, and stories. I jumped at the opportunity, buying tickets. Being able to hear a beloved author speak and laugh and joke and care… it was amazing. It made me think of two authors I had met and loved: Kate DiCamillo and Peter S. Beagle.

So, why am I writing this? Well, I’ve decided to go back where it all began. I’m going to read Coraline.

#godzilla reads#neil gaiman#Coraline#neil gaiman books#book blurb#long post#reading#reads#book blog#personal#books#booklr#bookworm#bookish#booklover#bibliophile#booklife#booknerd#book aesthetic#literature#books and libraries#books and literature#bookblr#book addicts#book addiction

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

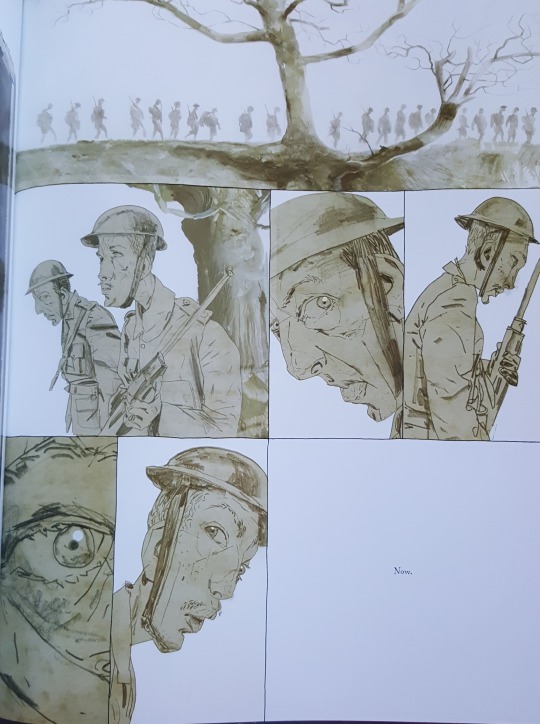

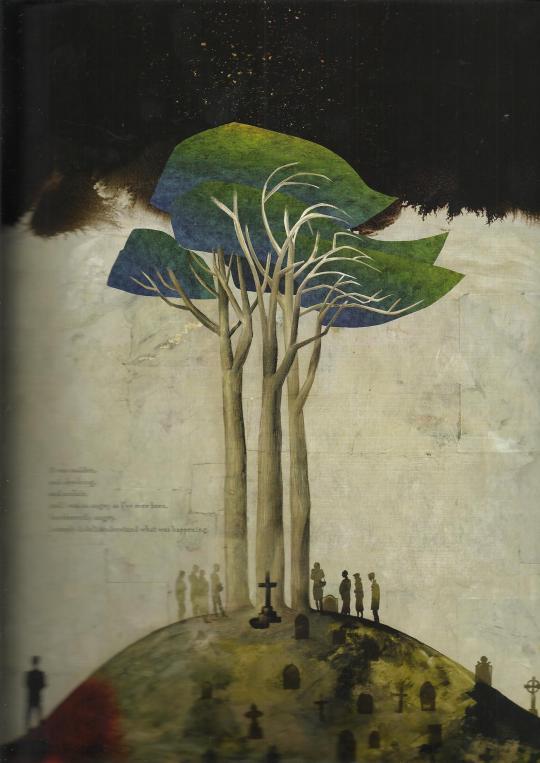

Black Dog: The Dreams of Paul Nash is incomparable to any other comic in appearance. Dave McKean, perhaps most well known to the comics world (most well known to me, anyway) for his covers for Neil Gaiman's The Sandman, has a style that transcends one's usual expectations for craft, materiality, form, and quality for a comic, looking more likely to have come from a museum catalog than destined for the pages of a book. McKean's Sandman covers tended towards sculptural collage; this book makes use of a variety of different styles. The most common is a linework-focused, pencil-drawn style, with collage elements, but the chapters shift between more intently rendered pencil and ink, something that appears digital but I think is in fact screen print, acrylic, pencil, collage, oil pastel, and much more. Black Dog is peppered with splash pages and images that could headline museum shows, densely textured, imaginative, made with incredible craft and ingenuity, they sucked me into this book like nothing else. Even at their simplest McKean's art has such a sense of texture and materiality it gives Black Dog this art book quality, every page arresting in a new way. This artistry is well served by the other elements of the comic. McKean's paneling tends toward simple but effective. He chooses shots and imagery with masterful efficacy, creating evocative dreamlike sequence after evocative dreamlike sequence. Strange surrealistic imagery abounds. The feverish nightmare of the images is tied together by a more straightforward first-person narration by real-life war painter Paul Nash, as he both walks us through the real events of his life and adds evocative psychological context to the imagery and encounters of his titular dreams. McKean pairs text and image, again, masterfully, so one is always fed or confounded by the other. He knows, mercifully, as so many artists seem not to, when to pull back the text and let the words do the talking, making for many of the most breath-holding moments of the comic. The few conversations of the book are as delightfully well-written as the narration, every character as immediately charming or terrifying as they ought to be, and always full of portent. Black Dog is one of my favorite comics of all time, dreamlike, grimly meaningful, as gorgeous and breathtaking as anything you've ever seen.

5/5

0 notes

Text

The Dreaming #1 (1996) Dave McKean Cover, Terry LaBan Story, Pencils by Peter Snejbjerg "The Goldie Factor, Part One" Goldie gets fed up with the way Cain is murdering Abel all the time and so leaves the House of Secrets. Premiere issue expanding on the Sandman Universe, the realm of Dream and its inhabitants. https://www.rarecomicbooks.fashionablewebs.com/Sandman%201989.html#Dreaming

#RareComicBooks #KeyComicBooks #Keycomics #RareComics #DCComics #DCU #DCUniverse

The comic book is in Near Mint+ condition. Like NEW. All comics are shipped in a bag, back board, with a tracking number, and in heaving duty shipping box! Rare Comics strong sturdy boxes help prevent damage to your comic books.

#the dreaming#dave mckean#peter snejbjerg#rare comic books#key comic books#dcuniverse#dc comics#dcu#vertigo#the sandman

0 notes

Text

Comics Read 08/01 - 06/2022

Partially to go with timeliness, partially because I wanted a really easy read with little to write about, over this week I read Dream States The Collected Dreaming, Sandman Presents and Sandman Overture covers 1997-2014 by Dave McKean. As I have said in the past The Sandman was the beginning of me reading comics, and my coming back to it coincided with the announcement of Sandman Overture. I always admired the covers with their multi-media build adds to their unworldly dream likeness. At some point that was my preferred style of comic covers, but I have come to appreciate that wouldn’t be appropriate for the variety of comics out there, and just broadening my taste.

The collection comes with a short story called “Fish Out of Water” written by Sandman scribe Neil Gaiman. It is dream like and is about a man who is given a fish that he has to carry around with him, and eventually relates to the fish profoundly. It’ s lovely and the art style is not really like the covers that come later.

The covers are great, and I should refer to them later when I just want to look at art. I have read some of the comics they were from, but mostly through Comixology, and I am glad to have a physical copy. I do wish there was more about how they were made. Often there is a caption that says something like “Acrylic, photography, digital” and I just want more about the how. The book’s format has the covers on the right hand side of the book with the captions on the left above a McKean sketch made more recently than the covers. There are captions for the sketches below. I would love to talk about the pairings of sketches and covers.

#The Sandman#Sandman#Sandman Universe#DC Comics#vertigo comics#dc Vertigo#what i’m reading#DaveMcKean#Neil Gaiman

1 note

·

View note

Note

I've never written anything to anyone relatively popular, but here goes. I loved Sandman, and it was so well written. I have always wanted to to write something as iconic as that. I have so many works in progress, including a game plan and possibly even something for DC comics. So, how'd you do it? How'd you land something with DC? How can you have gotten so many hits in a row, and how can I do it to? I just want to see my characters and stories become hits. Any advice at all to do that?

Well, you don't try and make hits. You try and tell stories that you care about, and you hope that if you care about them enough other people will too.

If I had thought I was going for hits, I would have spent a career being very disappointed, as for many decades things I made were always, if they were hits at all, minor cult hits. Sandman spent most of its run somewhere in the lowest reaches of the top 100 comics. It didn't actually outsell comics like Batman or Superman until the final issue. At this point, if you count all the graphic novel sales of Sandman, it's one of the bestselling comics of the last 30 years. But it wasn't at the time it was being released. Good Omens, Neverwhere, Stardust, and Coraline didn't make it onto the NYT Bestseller lists when they came out. They've become perennial bestsellers over the last 30 years. They weren't hits then.

I "landed something with DC" by making things I liked, and showing them to DC when they came to the UK on a talent scouting expedition, which got me a foot in the door. I was working on an independent graphic novel called Violent Cases at the time, with Dave McKean. And then I gave the people from DC an outline for Black Orchid after meeting them before they went back to the US -- they said later that it was because we had come up a possible project, and then I gave them an outline two days later that made them take a chance on me.

891 notes

·

View notes

Text

Why does everything I love interconnect in some way?

Back in my teens I had a deep obsession with Anne Rice’s Vampire Chronicles. For various reasons that obsession eventually died. But in 2006 (when I was twenty-four) the very last Broadway play I ever saw with my mother before she passed away with Lestat. For a while I was obsessed with the musical. I still have the libretto I bought on ebay in a blue binder and the demo recordings.

I knew Linderwoolverion wrote the libretto. I loved the animated Beauty and The Beast (that she wrote), and I later liked Maleficent well enough, not deeply obsessed but still loved. Beauty and the Beast (animated version) was my favorite cell animated Disney film.

In 2017 I discovered (and fell in love with) Neil Gaiman’s The Sandman.

But only tonight, just now, I learned Dave McKean had anything to do with the Lestat musical. Dave McKean, the man who did the covers for all of Sandman did the visual concept designs for Lestat the musical...

This is not the first time that my obsessions have interconnected. It’s just the latest in a long line of patterns of things I love webbing out into eachother. My obsession with Anne Rice’s Lestat died a long time ago but still it seems everything I love connects in some way.

Other obsessions interconnecting include Terrence Mann. I was very obsessed with Tim Curry and by extension Rocky Horror in 2001. I saw Rocky Horror on Broadway that year when Terrence Mann was Doctor Frank N. Furter. In 2007 I got hooked on the short lived TV series The Dresden Files where Terrence Mann was the ghost, Bob. Through my fanned interest in Terrence Mann I started to listen to Frank Wildhorn musicals like Scarlet Pimpernel. I had seen one of Frank Wildhorn’s musicals on Broadway in 2004, Dracula. And Dracula was / is yet another of my obsessions.

Certain obsessions of mine are cycler and come to me in waves and alternate. Dracula, Frankenstein, Faust, and most recently Sandman are the top four. But from this a bunch of tiny, thinner interests spoke out and connect, so it’s like my interests when visually conceptualized forms a great big spider’s web.

5 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Dave McKean

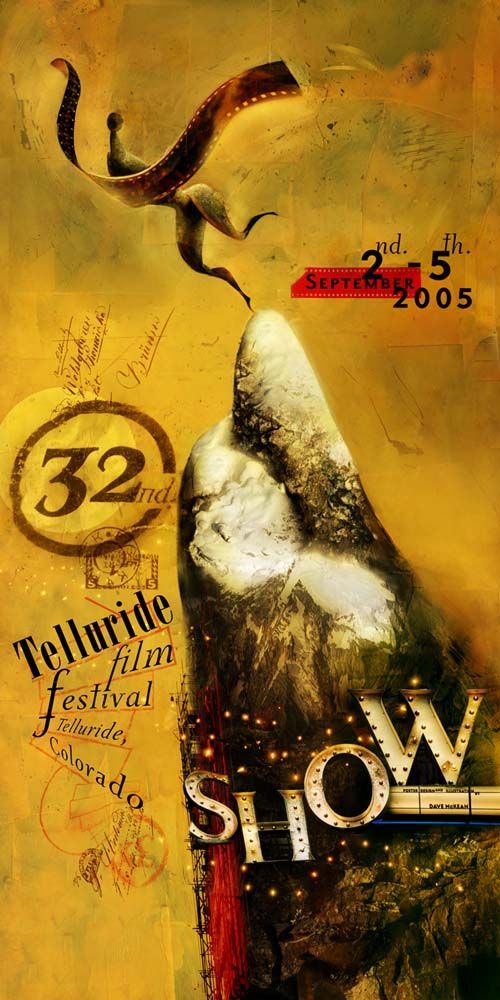

I’m using these first 4 research/influence posts to highlight influences that I’ve built up so far in my practise.

I’ve been a big fan of McKean’s work since 2005.

The best work showing his range and skills as an illustrator and layout designer has to be ‘Black Dog’, the dream-like retelling of the life events of Paul Nash, a British Modernist painter. In the book he uses collage, pencil and ink, photoshopped manipulations as well as paint and photography. It’s a great piece of work and captures his range and love of materials.

Another aspect of McKeans work that I really enjoy is his hand made typography and inventiveness with type. Sometimes he cuts out simple shapes to make letters or uses his fine line work and then goes back in an manipulates individual letters or just uses a variety of sizes and styles in the one heading. The best examples of this are in ‘The Sandman’ series where he made the illustrations and titles for each graphic novel.

Dave McKean Exhibition:

Dark Horse Comics (2020).

Special-Dave-McKean-Exhibit-in-Chicago-7-9-09

. [online] Cloudfront.net. Available at: https://d2lzb5v10mb0lj.cloudfront.net/darkhorse/index_images/news/mckean.jpg [Accessed 2 Oct. 2020].

Telluride 32. Film festival poster 2005:

McKean, D. (2020).

Telluride 32. Film festival poster

. [online] Davemckean.com. Available at: https://www.davemckean.com/wp-content/gallery/posters/Telluride_32.JPG.

Raindance 25. Film festival poster. 2017

McKean, D. (2015). Raindance 25. Film festival poster. 2017. [online] Davemckean.com. Available at: https://www.davemckean.com/wp-content/gallery/posters/Raindance25.jpg [Accessed 2 Oct. 2020].

BDFIL Poster:

McKean, D. (2015a). BDFIL. [online] Davemckean.com. Available at: https://www.davemckean.com/wp-content/gallery/posters/Lausanne-BDFIL-poster-corr.jpg [Accessed 2 Oct. 2020].

Exert from ‘Black Dog’ (Line):

Mckean, D. (2016). Black Dog : the dreams of Paul Nash. Milwaukie, Or: Dark Horse Books.

Exert from ‘Black Dog’ (Shape/Collage):

ibid.

Exert from ‘Black Dog’ (Shape/Collage)

ibid.

Dust Covers:

Gr-assets.com. (2020). 181015.Dustcovers. [online] Available at: https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/books/1386922278l/181015.jpg [Accessed 3 Oct. 2020].

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

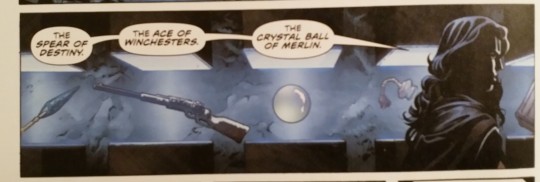

A nice little reminder that all this nonsense about whether Constantine is in the DCU or not, and the movement back and forth, is pretty irrelevant, and time would be better spent on storytelling than worrying about what universe is in what continuity. The Ace of Winchesters was first mentioned in Hellblazer, in the early days of Vertigo. Garth Ennis then used it in Hitman a couple of years later- John and Brendan had stolen it previously, now it was the turn of Catwoman to get her hands on this mystical weapon. Nobody seemed particularly concerned about this (admittedly vague) linking of the mature readers line with more mainstream characters then, it just seemed to be accepted that both things could exist (as with the Justice League references to the Doom Patrol being in the same headquarters at one point, or the heroes that occasionally showed up in Vertigo books), without having to alter the entire premise for no real reason, as DC ultimately did with Constantine.

A further example of the redundancy of such moves is seen with the presence of Jason Woodrue- his recollections of his past here are firmly tied to established Vertigo (or really, the Berger books that became Vertigo) stories- he refers to his discovery that the Swamp Thing was not human (as per Moore’s “The Anatomy Lesson”) and he talks of teaching both Alec Holland and Pamela Isley (as established by Neil Gaiman and Dave McKean’s Black Orchid mini-series). This history can coexist with the less ‘serious’ events of his history, such as becoming a New Guardian as a result of events in Millennium, without any need to segregate them or ret-con them.

Perhaps you wouldn’t want a reader of a certain age to be picking up the source texts from the shelf, but that doesn’t mean you can’t refer to them, particularly when they are significant events in the character’s biography- I always felt that the DC version of John Constantine might have had more luck if his biography had been left alone, instead of altered in some sort of poorly conceived notion of making it more suitable for a wider audience. Clearly there are elements that would not be suitable for inclusion in a book you have decided to aim at younger readers (and I will skip the questioning of the logic behind that decision, because I still don’t understand what they thought they would get out of that....), but one can easily refer to a character’s past without needing to provide all the detail- there’s no real sign of Moore’s unsettling horror here, for example, which would likely be deemed a little much for the target audience, but his story is untouched- the unsavoury elements can be brushed over, as required.

It seems particularly strange, now that DC is quite happy to have horror and violence more mainstream than it once was, turning a lot of titles darker than they may have been when Vertigo was still a force to be reckoned with, that they weren’t better able to reconcile the differences before now. Vertigo existed to tell the darker tales, but the DCU never quite separated from the imprint for a large part of the 90s, even if there was rarely any need for each ‘universe’ to directly reference the other, as they were clearly operating under different purposes and audiences. Yet as DC decided to make moves that ultimately lead to Vertigo closing its doors (Swamp Thing, Constantine, Animal Man and Doom Patrol all moved to the DCU, as well as the first run of Justice League Dark indicating that there was an editorial appetite for something a little different to the normal Justice League books, where previously this would have probably been more adult and at Vertigo, if commissioned at all), they deliberately separated things out, making it clear that Swamp Thing et al. were in the DCU, unnecessarily pushing some sort of continuity agenda that, if sales are any indication, no one really cared for.

Hellblazer and Swamp Thing had both lasted some time under the guidance of Vertigo editorial (171 issues and another volume of 20 or so for Alec Holland’s alter-ego, 300 issues for John Constantine’s mis-adventures), and Doom Patrol and Animal Man had both made into the high 80s (Shade, who was never really moved over with quite the same fanfare, instead confined to a few issues of Peter Milligan’s run on Justice League Dark, still made it to 70 at Vertigo). It would be misleading to suggest they didn’t have their own popularity problems- sales figures eventually led to cancellation in most cases, I believe (I’m not sure about Hellblazer, it seemed to just keep going, so I assume it was cancelled because DC wanted Constantine, whereas the others they could just lay claim to since nothing much was happening with the properties anyway)- but the characters were lucky to last even half as long in the DCU as they had done at Vertigo, and often with less critical adulation.

Giving up John’s 300 issue success story for about 38 issues of a not-so-interesting DCU version, with the only benefit to the character being a bit of rejuvenation (presumably editorial logic about no one wanting to read about an older person?), seems very much the sort of shitty deal John would con someone into accepting before he pisses off into the dark and lights up a fag. Now that editorial seems to be admitting failure and bringing him back to Vertigo (or whatever label the Sandman family of books will now be under, since Vertigo is gone), we seem to ironically be seeing a little more reason on the DCU side when it comes to accepting the existence of the mature readers books- Dark seems happy to accept the existence of Vertigo stories, as required, and the Dark Multiverse seems to have brought a little bit of a Vertigo touch to certain ‘mainstream’ books. Dial H For Hero was even happy to spoof entire Vertigo styles in what is effectively an all ages book. Hopefully this all indicates an improved relationship between characters, and a future where there will be less of a turf war over who can be used and what they can say/do/refer to, and instead the right character (as well as the right aspects of their history) will be used to serve the story instead of serving the confused god of continuity.

From Justice League Dark 15, by James Tynion IV, Álvaro Martinez Bueno, Raul Fernandez, Brad Anderson & Rob Leigh

#comics#DC comics#justice league dark#james tynion iv#alvaro martinez bueno#raul fernandez#hellblazer#swamp thing#jason woodrue#hitman

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Sandman never lived up to my initial expectations. If it had, it wouldn't be the benchmark series it is today. Instead, it turned into something I never imagined: one of the best comics works ever produced."

- Karen Berger (executive editor, Vertigo) on The Sandman, volume 1: Preludes & Nocturnes by Neil Gaiman

What's so interesting about this comic is that is was worked on by quite a few young people or people new to comics.

From the same introduction:

"Back in 1987, Neil was a new writer to comics"

"The artists on PRELUDES AND NOCTURNES, Sam Keith, Mike Dringenberg, and Malcolm Jones III, provided the right atmosphere for Morpheus' haunting origin story. Like Neil, they were relatively new to comics and were evolving their own distinctive styles."

"The covers for this first storyline (and all future ones) were illustrated, constructed and assembled by Dave McKean. An extraordinarily gifted artist at the ripe old age of 22, Dave was fresh out of art school when he worked on BLACK ORCHID [Neil's comic before The Sandman]."

#the sandman#morpheus#neil gaiman#sandman comics#comic books#sam kieth#mike dringenberg#Malcolm jones III#dave mckean#I need to borrow the subsequent comics from the library

4 notes

·

View notes