#borovsk

Text

1 note

·

View note

Text

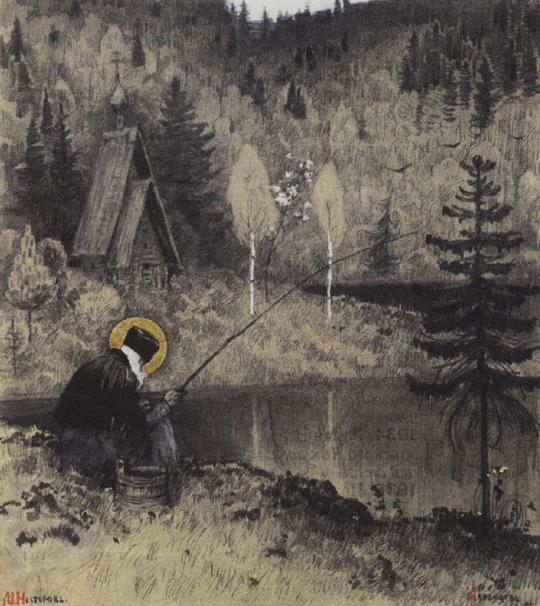

Mikhail Nesterov - Saint Pafnuty of Borovsk

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Ivan III of Russia

Ivan III of Russia (Ivan the Great) was the Grand Prince of Moscow and Russia from 1462 to 1505. Ivan III was born in 1440 to Grand Prince Vasily II of Moscow (r. 1425-1462) and his wife, Maria Borovsk (l. c. 1420-1485). He served as co-ruler for his blind father from 1450 until he became regent in 1462.

Continue reading...

81 notes

·

View notes

Text

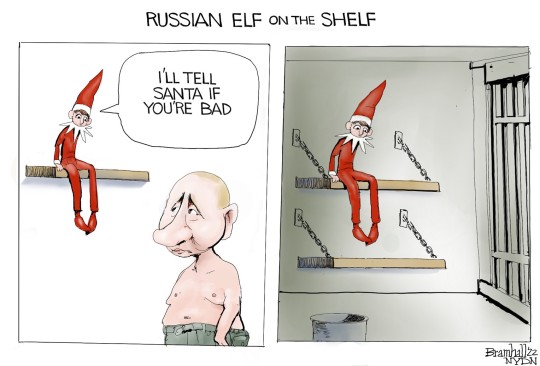

Rosenberg: Russia's stage-managed election

In Borovsk, Steve Rosenberg looks at the Russia Putin wants you to see – and Russia in reality.

from BBC News https://ift.tt/Bb6Cwx4

via IFTTT

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

Wings (Крылья, 1906) by Mikhail Kuzmin - Part Two

“Think about it, Vanya, what a wonder it is, that here’s a stranger, a complete stranger, and his legs are different, and his skin, and his eyes, and he’s all yours, you can see, kiss, touch all of him, all; and every blemish on his body, no matter where it was, and the golden hairs that grow along his arms, and all the little furrows and hollows of his skin, beloved beyond measure. And at the same time, you know how he walks, eats, sleeps, how the wrinkles on his face scatter when he smiles, how he thinks, how his body smells. And then you’ll not be your own self, rather, it’s like you and he are the same person: bound together by flesh, by skin, and there is no greater fortune on Earth, Vanya, than love, and without love it’s unbearable, unbearable! And what I’ll tell you, Vanya, is that it’s easier to love without having than to have without loving. Marriage, marriage: it’s not a secret that the priest blesses and then children come along – the cat there is expecting four times a year, even – but that the soul burns to give itself to another and to take him completely, whether for a week, whether for a day, and if both souls blaze then that means that God has united them. It’s a sin to make love with a cold or calculating heart, but he who is touched by destiny’s fiery finger will remain pure before the Lord, whatever he does. Whatever a person whose soul is ablaze with love does, he will be forgiven everything, because he’s not himself, in his soul, in his ecstasy…”

And Maria Dmitriyevna, who had earlier stood up in agitation, paced from apple tree to apple tree and settled back down next to Vanya on the bench, whence could be seen the demi-Volga, unending forests on the other bank and, far away on the right, a white church sat across the Volga.

“But it’s a frightful thing, Vanya, when love strikes you; happy, but frightful; it’s like you’re flying and falling all the time, or dying, like it is in a dream; and then you keep seeing the same thing everywhere, that your face has been struck through by your beloved: perhaps your eyes, perhaps your hair, perhaps your gait. And it’s marvellous, indeed: here’s a face, what about it? A nose in the middle, a mouth, two eyes. What about it gets you so worked up, captivates you so? And, after all there are a lot of beautiful faces that you see and you feast your eyes upon them, like flowers or some kind of brocade, while another is not beautiful, yet it transforms your whole soul, but it’s not for everybody, only you and only this face: how can that be? And what’s more,” added the speaker, hesitating, “is that, yes, men love women and women love men; it also happens, it is said, that a woman can love a woman, and a man, a man; it happens, it is said, and indeed I have read about it myself in biographies: Eugenia of Rome, Niphon, Paphnutius of Borovsk, even Tsar Ivan Vasilyevich.[1] It’s not even difficult to believe, why should God not be able to embed this thorn in humanity’s heart? It is difficult, though, Vanya, to go against that which is embedded, perhaps even sinful.”

The sun had almost set behind the tooth-like pinewood forest and the three meanders could be seen turning yellow in the pink light. Maria Dmitriyevna, silent, watched the dark forest on the other bank and the paling purple hue of the evening sky; Vanya was silent too, as though continuing to listen to his interlocutor with his whole being, his mouth half-open, then, not quite regretfully, not quite judgingly, he suddenly remarked:

“As it happens, that even such people are sinning: from curiosity, or pride, from self-interest.”

“It may be, it all may be; their sin,” Maria Dmitriyevna, somehow humbled, confessed, without shifting her position or turning to Vanya, “but it’s so hard for them, those who have this embedded within them, ah, so hard, Vanechka! I’m not speaking to grumble, life is easy for others, but there’s not point in it; it’s like shchi without salt: filling, but not tasty.”

After the room, the balcony, the vestibule and the yard with the apple trees, dinners were moved to the cellar. It was dark in the cellar and smelt of malt, cabbage and some mice, but it was considered to be less hot there, and there weren’t flies; a table was placed opposite the door for the best lighting, but when Malania, practically running across the yard with her meal, paused in the entryway in order to descend the steps in the dark, it became even darker and the cook inevitably grumbled, “It’s already so dark, Lord forgive me! Tell me, what were you thinking, where were you running off to?” Sometimes, without waiting for Malania, the curly-haired Sergei, a fine man from the store who lunched at the house together with Ivan Osipovich, would run after the dishes; and, when he was then hurrying about the yard with the dish held high with both hands, the cook would hurtle after him with a fork or a spoon, shouting, “What’s this all about, as if I wouldn’t serve it myself? Why would I chase Sergei? Soon, I will be…”

“You might be soon, but we’re now,” retorted Sergei, rakishly clattering down his tableware in front of Arina Dmitriyevna and sat down with a smile on his spot between Ivan Osipovich and Sasha.

“And what was God’s point in coming up with this heat?” Sergei kept asking. “No-one needs it: the water dries up, the trees burn – it’s a burden for everything.”

“It’s for bread, you know.”

“Yes and for bread without time, without measure, there’s not much profit. Whether it’s in time or not, God sends everything.”

“If it’s not in time, then that means it’s an ordeal because of your sins.”

“And here,” intervened Ivan Osipovich, “we had an old man killed by the heat; he didn’t offend anyone, and he went off on a pilgrimage, but he was killed by the heat. How can we understand this?” Sergei silently triumphed.

“For someone else’s sins, he suffered, not his own,” decided Prokhor Nikitich, in a tone not entirely convinced.

“But how can that be? Other people get wasted and go carousing, but for them, the Lord kills guiltless old men?”

“Or, forgive me, for example, if you hadn’t been paying your dues and I got put in jail instead of you; would that be good?” remarked Sergei.

“You’d fare better to slurp up some shchi than to pick apart these stupidities; what’s the point, well, what is the point! What’s the point of you? You think about the heat, that there’s no point to it, while it might be thinking about you, Serjozhka, that you're pointless."

Satisfied, they drank long and onerously of tea, whether apple or varenye.[2] Sergei once again began to resound.

“It’s often very hard to understand what needs to be understood; let’s take this: a soldier kills a person, I kill a person; he gets a medal, I get hard labour – why is that?”

“Where did you get that from? I’ll say: a husband lives with his wife, while a bachelor with a woman is getting mixed up; another person would say it’s all the same, but the difference is big. What in, you ask?”

“I can’t know,” responded Sergei, looking him fully in the eye.

“In the imagination. First,” said Prokhor Nikitich, as though reaching not only for the right words, but the thoughts as well, “first: the married man living with one other has once concern; for another thing, they live quietly, peacefully, accustomed to one another and the husband loves his wife all the same as he eats food or scolds his helpers, while those others with all those stupidities in mind, all hee-hee and ha-ha, have neither steadiness nor staidness; that’s why one is law and the other is lechery.”

“Allow, though, since it happens, you know, that a husband can adore his wife with heartfelt awe, while another is so at one with his lover that kissing her is as natural as crushing a mosquito: how then can we determine, where it’s law and where it’s lechery?”

“To do so without love is a singular abomination,” suddenly responded Maria Dmitriyevna.

“Here you say ‘abomination’, but I don’t know the word well, I need to understand its force. They say animal sacrifice is an abomination, so roughly speaking, eating hares is an abomination; lechery even!”

“Why are you all ‘lechery’ this and ‘lechery’ that! Give some thought about what kind of conversation you’re leading in front of young boys!” shouted Arina Dmitriyevna.

“What about it? They can understand it themselves. Isn’t that right, Ivan Petrovich?” the old man Sorokin turned to face Vanya.

“What’s that?” started Vanya.

“What do you suppose about all of this?”

“Well, you know, it’s very hard to judge other people’s business.”

“And there’s the truth, Vanechka,” rejoiced Arina Dmitriyevna, “And you should never judge; it is said, ‘Judge not, lest ye be judged.’”

“Well, other people don’t judge but get judged themselves,” said Sorokin, getting up from the table.

There were only tradeswomen left on the wharf and the footbridges, with little loaves, roaches, raspberries and salted cucumbers; the mooring boys in their colourful shirts stood around, leaning on the railings and spitting into the water, and Arina Dmitriyevna, having led the old man Sorokin to the steamboat, took a sit in a wide row next to Maria Dmitriyevna.

“How have we managed to forget those flatbreads, Mashenka? Prokhor Nikitch does so love to have his tea with them.”

“But I put them in plain sight and everything, all for nothing.”

“If only you’d remembered, Parfyon!”

“Hey, what’s it to me? If it had been left behind somewhere on purpose, then of course I would have shouted, but I didn’t go up to the upper rooms” the old worker justified himself.

“Ivan Petrovich, Sasha! Where are you going?” called Arina Dmitriyevna to the young people, who had already started to climb the hill.

“We’re going on foot, Mamenka, by some path or other, we’ll get there even before you.”

“Well, walk, walk young legs. Would you get a lift then, Ivan Petrovich?” she urged Vanya.

“No, it’s nothing, we’ll do it on foot, thanks you,” cried he from halfway up the hill.

“There – Ljubimovski’s come running,” remarked Sasha, taking off his cap and turning his slightly perspiring, reddened face to the wind.

“Is Prokhor Nikitich away for long?”

“No, he won’t be staying on the Unzha past St Peter’s Day,[3] he doesn’t have much business there, just taking a look.”

“And you, Sasha, how come you never go out riding with your father?”

“I go out with him all the time, it’s just that since you’ve been a guest round ours that I’ve not gone.”

“What do you mean you’ve not gone out? Why are you ashamed of me?”

Sasha pulled his hat down low once more over his black hair blowing around in all directions, and, smiling, remarked:

“There’s no shame, Vanechka, none, and I’m so glad to stay with you, Of course, if I were alone with mamasha or auntie, I’d get bored, but I’m very happy,” having fallen quiet, he continued, as though in deep reflection, “here you are, spending time on the Unzha, the Vetulga, the Moskva and you don’t see much of anything, besides your own business, like a blind person! It’s just forest everywhere and on and on about the forest: how much it’s worth, how much to transport, how many logs will come out of it, lumber too – that’s all! Daddy is already set up that way, and he intends to make me the same. And wherever we go – now to the foresters’, or the taverns, it’s all the same thing everywhere, one conversation. It’s boring, it is, you know. It’s like, let’s say, there was a builder and he only built churches, and not whole churches, but just the eaves on the churches; and he went round the whole world and everywhere he went, he had eyes only for the church eaves, looking neither at the diverse people, nor how they lived, how they thought, prayed, loved, nor the trees, nor the flowers in those places – he saw nothing, besides his eaves. A person should be like a river or a mirror – he should accept what is reflected within him; then, like in the Volga, there will be a little sun, clouds, forests, tall mountains and towns with churches inside of him- everyone should get it straight and then you combine everything in yourself. Whoever gets hung up on something gets eaten, most of all by self-interest or something divine, perhaps.”

“Well, church matters, or something! Whoever thinks and reads about it all the time will find it hard to understand other things.”

“But then there are bishops who don’t shy away from the secular, our own Bishop Innokenti, for example.”

“Of course there are, and, you know what, in my opinion they’re doing very poorly; you cannot be a good officer, a good merchant while understanding everything in the same way; that’s why, from the bottom of my heart, I envy you, Vanya, that none of you are taught alone, rather, you know and understand everything, unlike me for example, despite us being of the same age.”

“Hey, where are you getting it from that I know everything? They don’t teach us anything at the gymnasium!”

“All the same, knowing nothing is better than knowing only one thing through which to understand everything.”

From below, rattling of the droshky[4]could start to be heard, and somewhere out far away on the water resounded a loud argument and the splashing of oars.

“Our people have been gone a long time!”

“They must have gone round to Loginovo,” noted Sasha, sitting down next to Smurov on the grass.

“Are we the same age?” asked the latter, gazing at the Volga, where the shadows of clouds sped over meadows.

“And how; we were almost born in the same month. I asked Larion Dmitriyevich.”

“Do you Larion Dmitriyevich well, Sasha?”

“Not so well, as such; we only got acquainted not long ago, after all; that, and he’s not the kind of person you can grasp at first meeting.”

“You heard what kind of story has come out around him?”

“I’ve heard, I was still in Petersburg at that point; only, I thought that all of that was untrue.”

“What’s untrue?”

“That that young lady didn’t kill herself. I saw her, Larion Dmitriyevich once showed me her in the garden. What a wonder! I then said to Larion Dmitriyevich, ‘mark my words, this young lady will end badly.’ How blissful she was, in a way.”

“Yes, but even without shooting, there can be a motive for suicide.”

“No, Vanechka, if someone gets offended by something that doesn’t concern them and they kill themself, then no-one is the cause.”

“And you blame Stroop for whatever it was that Ida Pavlovna shot herself because of?”

“And because of what do you think she shot herself?”

“I think you know yourself.”

“Because of Fyodor?”

“So it seems to me,” answered Vanya, grown confused.

Sorokin did not respond for a long time, and when Vanya raised his eyes, he saw that he was completely apathetically, even a little bit angrily watching the path, from whence the droshky with Parfen was ascending.

“Why aren’t you saying anything, Sasha?”

He gave a cursory glance over Vanya and said, angrily and simply:

“Fyodor is a simple lad, a muzhik, why should someone shoot themself because of him? In that case, well, Larion Dmitriyevich would need to take on neither a coachman for the horses, nor a doorman for the days, neither would he need to go to the doctor’s when his teeth ached. For it to not have been Fyodor, it must be…”

“Are you waiting for us?” cried Arina Dmitriyevna, dismounting from the droshky, while Parfen and Maria Dmitriyevna gathered their bags and sacks, and a black mongrel dog flew around with a bark.

On Saint Peter’s day, they were preparing to go on a trip to the hermitage about forty versts[5] from the Volga, to stand through mass together with the priest on such a big holiday, and to meet up with Anna Nikanorovna, a distant relative of the Sorokins, who lived at the hermitage’s apiary; at Cheremshana, where Prokhor Nikitich’s daughter lived, they put off leaving until Elijah’s Day, so that they could take advantage of the hospitality until the end of the fair, where Vanya was intending to go as well. In September, they were thinking of meeting up – the women from Chereshmana, the men from Nizhny, while at the end of August, Vanya intended to go straight to Saint Petersburg, without dropping by. Four days before departure, almost packed for the road, everybody sat down over evening tea, discussing for the tenth time who was going where and for how long, when the evening post brought two letters to Vanya, who had not received a single one since his very arrival. One was from Anna Nikolaevna, in which she asked to look for a small dacha in Vasili for 60 roubles, since in the end, Nata had lost heart to the extent that she could not stand to live in a dacha near Saint Petersburg, Koka had left to tend to his grief in Naantali, near Hanko, while Aleksei Vasilyevich, uncle Kostya and Boba simply remained behind in the city. The other was from Koka himself, in which, between sentences about how he grieved ‘the death of that ideal girl, slain by that scoundrel’, he related how there was an entertainment hall nearby, plenty of young ladies and how he spend entire days riding his bicycle and so on and so forth.

Why has he written all this to me? thought Vanya after reading the letter: Could it be that he doesn’t have anyone, besides me, to address this to?

“Here, my aunt and sister are asking to come look for a dacha; they want to come here.”

“Well then, it seems the Germanikhas aren’t busy, the people from Astrakhan wanted to come, but for some reason aren’t; it wouldn’t be far for you.”

“Please ask, Arina Dmitriyevna, whether she won’t give it up for 60 roubles, and how everything is there, generally.”

“She’ll do it for 50; don’t worry, I’ll sort everything out.”

Retired to his room, Vanya sat a long while by the window without lighting his candle, and Petersburg, the Kazanskys, Stroop, his apartment, and, for some reason, Fyodor in particular, the way he had seen him the last time, in the red silk shirt without a belt, a smile on his face, blushing, yet unaccustomed to colour, with a carafe in hand – it all came back to him; now having lit his candle, he took out a little volume of Shakespeare, containing Romeo and Juliet, and tried to read it; there was no dictionary and without Stroop, he understood a fifth to a tenth of it, but something of a torrent of beauty and of life suddenly swept him up like never before; it was as though something primeval, long unseen and half-forgotten had resurrected and embraced him with burning hands. There was a gentle knock at the door.

“Who’s there?”

“Me! Can I come in?”

“As you please.”

“Forgive me, I’m bothering you,” said Maria Dmitriyevna as she entered: “Here’s a leaflet I brought you, put it in your bag.”

“Ah, good!”

“What’s that you were reading?” Maria Dmitriyevna hesitated to leave. “I thought, it couldn’t be a synaxarion[6] that he’s taken to read, could it?”

“No, it’s just the one play, an English one.”

“I see; I thought it couldn’t be a synaxarion, I couldn’t hear the words, but you do read with some emphasis.”

“I was reading aloud?” Vanya was surprised.

“How else…? I’ll put the leaflet on the shelf… Good night.”

“Good night.”

And Maria Dmitriyevna, correcting a candlestick, noiselessly departed, quietly, but firmly shutting the doors. Vanya looked around in wonder, as though awakened, at the image in the icon case, the candlestick, the ironbound chest in the corner, the made bed, the strong table by the window with the white curtain, through which the garden and the starry sky could be seen – and, after shutting his book, he blew out the candle.

“Look, there’s some forget-me-nots in the marsh!” exclaimed Maria Dmitriyevna every minute for as long as they were riding through the marshland meadows, grown over with pale blue flowers and tall water grass, on which perched dragonflies with the almost imperceptible thrill of their glittering wings and wholly green little bodies. Fallen behind with Vanya from the first trap cart, in which Arina Dmitriyevna was riding with Sasha, now she would get out from the cart and walk along the track by the marshes and the woods, then she would sit back down again, or pick flowers, or sing something, and the whole while she spoke to Vanya as though to herself, as if she were drunk on the forest and the sun, the blue sky and the blue flowers. Vanya looked on with almost condescending interest at the beaming, adolescent-seeming face of this woman in her thirties.

“In Moscow we had a wonderful garden. We lived in Zamoskvorechye: apple trees and lilacs grew, and in the corner was a spring and a blackcurrant bush; in the summer, we didn’t go anywhere, and so it would be that I’d spend the whole day in the garden, cooking jam… Here’s what I love, Vanechka, to go walking barefoot on hot earth, or to bathe in a brook; through the water you see your body, golden light scatters over it, and when you plunge below the surface and open your eyes there, everything is so green, and you see the fish fleeing from you, and then you lay on the hot sand to dry, a light breeze blows, glorious! And it’s better when you lay alone, without any friends. And it’s not true, what old ladies say, how the body is sinful, flowers and beauty are sins, washing is a sin. Did God not create all of this? The water, and the trees, and the body? To sin is to go against the will of the Lord: when, for example, someone is set upon something, dying for it, to not allow it – that’s a sin! And how you have to hurry, Vanya, it’s unspeakable! Like a good housewife stores away cabbages and cucumbers in time, knowing that you won’t be able to get them later, so do we, Vanya, need to get our fill of seeing, loving, breathing all in time! Are our lives so long? And youth is even shorter still, the minute that passes will never come back, and you must remember this always; then everything will be twice as sweet, like an infant who has only just opened its eyes, or a dying person.”

The voices of Arina Dmitriyevna and Sasha could be heard from far away; behind them, Parfen’s cart rattled along the causeway, flies buzzed, the grass smelt of the marsh and of flowers; it was hot, and Maria Dmitriyevna, in a black dress and white handkerchief in the process of falling apart, pale from exhaustion and the heat, with shining dark eyes, sat, slightly hunched over, on the little cart next to Vanya, tearing apart the flowers she had gathered.

“I don’t care what I think about myself, or what I speak about with you, Vanechka, because you have an infantile soul.”

As they turned, a vast field opened up before them, upon which stood a jumble of houses with entrances inside; a lot of them looked like sheds, without windows, or with windows only on the top floor, without perceptible streets, rubbish tips, grown grey with time. There were no people visible and only the barking of dogs came from the hermitage to meet Arina Dmitriyevna and Sasha’s cart as it kicked up dust.

After Mass, the Sorokins and Vanya set off in the direction of the elder Leontius who lived at the apiary, around half a verst from the hermitage. As they hastened through a shaded copse to the little field, where, among the tall grass and flowers, the flow of an unseen brook in a wooden gutter could be heard, Arina Dmitriyevna informed Vanya about the elder Leontius:

“He switched from the Great Russian[7] to the true Church a long time ago, about thirty years, and even then, he was not young. And he’s a tough old man, a zealot; he’s been in court four times, served two years in Suzdal; he fasts, terribly so, and is angry when he prays – like a coiled spring! And he sees everything coming in advance… You really shouldn’t say directly that you’re orthodox, Vanya, he might not like that.”

“Or perhaps he’ll start teaching me better?”

“No, really, you’d better not say…”

“Yes, ok, ok,” said Vanya absent-mindedly while he looked with curiosity at the low little peasant cottage, pink mallows around, and, standing upon the earthwork that protected the house from the weather, the grey old man in a white shirt of a course, dark blue fabric and a small skull cap on his head, with a long, pointed beard and lively, joyful eyes.

“How he came, that priest, upstairs to me to dredge up the Gospel. ‘It’s fortunate,’ your man says, ‘that you have a way out, otherwise I’d have taken them, the pictures and drawings, I’ll be sure to take away.’ I had portraits of Semyon Denisov, Pyotr Fillipov and a few others hanging on the wall. But I’m not old yet, I’m healthy, and I say, ‘that’s up to you, pa, like I’d let you take them.’ The deacon was completely drunk, all moaning and groaning, and he says, ‘stop it, father.’ The priest threw me onto the bed and he wanted to pour tea out of this little saucer – to baptise me, apparently, but I gathered my strength and he gave off: ‘goodbye,’ he says, ‘I’ll chat with you later’ – and as I went to see him off, he grabbed me and shoved me down the slope.”

And the old man recounted, as though by heart, how he had been with Nekrasovites[8] in Turkey, how they had wanted to kill him, how he had been judged, how he had done his time in Suzdal, how he was saved in all circumstances by a cross with relics, and he brought out of his hut, stooping lowly in the doorways, a bare cross, where on the copper mounting was embossed ‘Relic of Saint Peter, Metropolitan of Moscow,[9] miracle worker, of the Faithful Saint Priestess Fevronia of Murom, of the Prophet Jonah, of the Faithful Saint Tsarevich Dmitri, and of our Reverend Mother Mary of Egypt.’

Inside, through the window, icons on the shelves, the red flames of little lampads and their candles, books on the windowsills and tables, and a bare bench with a log of firewood by its headboard were all visible. And the elder Leontius, looking upon Vanya with unwelcomely jolly eyes, said in a sing-song manner:

“Stay firm in the true faith, my son, for what is higher than the true faith? She covers over all sins and inducts you into the house of eternal light. The light eternal of our Lord Jesus must be loved more than all else. What else is eternal, imperishable as the paradise of radiant light, the salvation of the soul? Whether a flower charms you, or you love a person – tomorrow, it shall wither, tomorrow, they shall die; they become sunken, your eyes, their clear light shall fade, your rosy cheeks shall yellow, you shall be deprived of your hair, your teeth and you shall be food for worms, entirely. Marching corpses – such are the people of this world.”

“It will be easier now that you’re allowed to build and serve openly,” Vanya tried to distract the old man.

“Pursue not that which easy, but rather aim yourself towards that which is hard! Simplicity, freedom and wealth – peoples perish from these things, while in baleful sufferings, they save their faith. The enemy of mankind is cunning, his machinations secret – and it needs be determined, whence comes every kindness.”

“Where has this spitefulness come from?” said Vanya, leaving the apiary.

“And also: are people guilty for the fact that they die?” agreed Maria Dmitriyevna. “But I would love so much the more that which is condemned to death tomorrow.”

“You can love anything, but not give your heart away to any one thing, lest it get eaten,” remarked Sasha, who had been silent the whole time.

“What philosophers have appeared,” remarked the aunt, disdainfully.

“What, do I not have a head, then, huh?”

“And how did he not find this out, that you’re ecclesiastical? Or perhaps, my dear, he foresaw that you’ll arrive at the true faith?” reasoned Arina Dmitriyevna, looking sweetly at Vanya.

It was almost completely dark in the room, being lit by a single candle; the deep red sunset sky, yellowing towards the top, and the black pinewood beyond the glade could be seen in the window, and Sasha Sorokin, warming himself by the evening window as it turned red, continued speaking:

“It’s difficult to reconcile this! As one of ours said, ‘How are you going to read the canon to Jesus after the theatre? It’s easier to kill a person.’ And just so: to kill, to steal, to commit adultery you can do while under any faith, but to understand Faust and prayer with a lestovka[10]with conviction is unthinkable, or, God knows, teasing the devil. And if, say, a person doesn’t commit any sins and follows the rules, but doesn’t believe in their necessity or propriety, then that’s worse than if they believed but didn’t follow. But how to believe when it’s not to be believed? How to not know what you know, to not understand what you understand? And then you can’t judge: this is wise, I’ll follow this through, while that is nonsense, unnecessary: who set you up to judge like that? Wherever they’re not repealed by the Church, all rules must be followed, and we must shun worldly arts, not be treated by infidel doctors and observe all fasts. The old orthodoxy can only be held to by old men in the woods and why should I be called something that I don’t belong to and don’t consider necessary? And how can I think that only this handful of us will be saved while the whole lounges in sin? But how can I consider myself an Old Believer without thinking this? Likewise, to accept any other faith or life, and all other people’s humiliations is cruel, but understanding everything at once, you cannot be a true believer in any way.

Sasha’s voice quietened and rang out again, while Vanya, laying on the bed, said nothing in response from the darkness.

“See, from your outside perspective, maybe our life, faith and rituals are more obvious and better understood than by ourselves, and our people are understood by you, perhaps, but by them, you are not, or only one part of you, not the most important, will be grasped by one of our aunties or old men, and you will always be a stranger, an outsider. There’s nothing for you to do there! As for you yourself, Vanechka, no matter how much I love and respect you, I can feel what’s in you that weighs upon and confuses me. Our fathers, and our grandfathers, too, lived, thought and knew in different ways, and we can’t yet compare ourselves with you – a difference will manifest in some way, and here, a single desire won’t do anything.

Sasha’s voice once again fell silent and for a long time all that was heard was the faraway singing from the open doors of the oratory.

“And how’s Maria Dmitriyevna?”

“What about Maria Dmitriyevna?”

“How does she think, is she getting along?”

“Who knows how; she’s devout and misses her husband.”

“Did her husband die a long time ago?”

“A while ago, eight years already, I was still rather a little boy.”

“You’re lucky to have her.”

“She’s not bad, she doesn’t have very many big ideas either,” said Sasha, closing the window.

The cart with the guests was still approaching the gates; Arina Dmitriyevna, who had hardly sat down at the table, ran out to meet them and the welcoming cries and kisses could be heard from the porch. In the hall, where about ten men were dining, it was loud and hot; taking Malania on for help, the bare-footed Froska momentarily ran to the cellar with a large glass pitcher and came back, bearing it filled with cold, foamy kvass. In the room where the women were eating, coming in behind the hostess, who was running from table to table, meeting and greeting, and into the kitchen and into all the newly-arrived guests, Maria Dmitriyevna, Anna Nikolaevna and Nata, along with five-hundred other guests, sat down, having wiped the sweat from their faces with their coats, already soaked through, whilst the dishes piled up more and more, the Madeira port and Nalewka liqueurs drank themselves, and flies climbed in the dirty glasses and sat in mounds on the whitewashed walls and on the crumbs upon the tablecloth. The men took off their jackets and in waistcoats over colourful shirts, red and drowsy, they loudly had a laugh, chatting and hiccoughing. The sun came through the open door and the glass vitrine, shining upon the candlesticks, brightly ablaze, and further, into the neighbouring room, upon the painted birdcage with the canaries in, which, aggravated by the noise all around, sang frantically. Every minute dogs that had crawled in from the yard were being led out, and the door, held open by Froska’s bare foot, slammed on the block and she squealed; it smelt of raspberries, pierogi, wine and sweat.

“Well, judge for yourselves, I order him to reply by telegram to Samara and he doesn’t say a word!”

“To begin with, take it down to the cellar, drenched in spirit and then on another day, cook it with oak bark – it turns out very tasty.”

“On Ascension Sunday, Father Vasily from Gromov gave a wonderful speech: ‘Blessed are those who make peace – that goes for you as well, make peace over the Chubykin almshouse, forgive the warden the debts and don’t ask for a statement!’ – It was a laugh!”

“I said 35 roubles and he gives me 15…”

“Blue, so blue, and pink stains,” came from the women’s room.

“To your health! Arina Dmitriyevna, your health!” cried the men to the hostess hurrying to the kitchen.

The chairs all made a noise at once and everyone began to silently cross themselves before the icon in the corner; Froska was already hauling the samovar out and Arina Dmitriyevna was trying to wrangle the guests so that they didn’t split off before tea.

“You can’t possibly like this life,” Nata asked Vanya, who had come to lead them through the courtyard away from the Sorokin’s dogs.

“No, but there’s worse.”

“Hardly,” remarked Anna Nikolaevna as she opened the gate again to free the hem of her grey silk dress which had become caught.

“Let’s sit here, Nata, I’d like to speak with you.”

“Let’s sit, then. What did you want to talk about?” said the girl, sitting next to Vanya on a bench in the shadow of some large birch trees. Maintenance was being carried out on the nearby church and the through the open doors, the painters, who were forbidden by the priest from singing worldly songs inside the church, could be heard singing hymns. The portico, lined with thick bushes of wheatgrass, was not visible, but each word was clearly audible on the evening air; in the distance, the herd lowed on its way home.

“What did you want to speak with me about?”

“I don’t know; perhaps it will be heavy or unpleasant for you to look back on this.”

“You want to talk about that unfortunate business, is that right?” said Nata, falling silent.

“Yes, if you could clear it up for me, even however much, do so.”

“You’re making a mistake if you think that I know more than anyone else; I only know that Ida Golberg shot herself, and I’m not even aware of the reason for her actions.”

“You were there when it happened, though?”

“I was, although not for half an hour, it was more like ten minutes, seven of which I spent stood in the empty hallway.”

“Were you there in the room when she shot herself?”

“No; it was the shot itself that made me go into the office…”

“And she was already dead?”

Nata silently nodded in affirmation.

The painters in the church began to belt out psalm 141, “Lord, I cry unto thee: make haste unto me.”

“Let go, damn you! Where are crawling off to?! Come on!”

“Ah!” rang out the feigned cries of a woman’s voice from the portico, whilst an unseen partner preferred to continue the playfight, silent.

“Ah!” even louder, like the screams of drowning people, rang out the exclamation, and the wheatgrass bushes shivered in one particular spot without any wind.

“Evening sacrifice!” finished the singers inside, pacifyingly.

“On the table, there was a carafe, or a siphon – something glass – and a bottle of cognac, a person in a red shirt was sitting on a leather sofa, doing something near that table, while Stroop himself was standing to the right and Ida was sitting, with her head thrown back on the back of the armchair by the writing table…”

“She was no longer alive by that point?”

“Yes, it seemed she was already dead. I’d barely got in the room when he said to me, ‘Why are you here? For your own happiness, for your own peace, get out! Get out right now, I beg you.’ The one sitting on the sofa got up and I noticed that he had no belt on and was very red; his face was glowing red and his hair was dishevelled; he seemed drunk to me. And Stroop said, ‘Fyodor, show the lady the way out.’”

“Thy will be done,” they were already singing another song in the church; the voices from the portico, already quietened down, babbled on without shouting; the woman, it seemed, was very quietly crying.

“All the same, that’s terrible!” declared Vanya.

“It’s terrible,” echoed Nata, “but even more so for me: I loved that person so much,” and she began to cry.

Vanya disaffectedly watched the somehow suddenly aged, slightly saggy-skinned girl with a pouting mouth and freckles, now joined together into solid brown blemishes, and dishevelled red hair, and asked:

“So you loved Larion Dmitriyevich, then?”

The girl silently nodded, and began, unusually tenderly:

“Vanya, you won’t keep in correspondence with him now, will you?”

“No, I don’t even know his address, not since he gave up his apartment in Petersburg.”

“You could always find it.”

“And what if I had been writing to him?”

“No, nothing.”

A young man in a jacket and cap quietly left the bushes and when he had drawn even with and bowed before Vanya, the latter recognised him for Sergei.

“Who’s this?” asked Nata.

“The Sorokin’s steward.”

“He’s probably also the hero of some recently transpired story,” added Nata, smiling somewhat vulgarly.

“What story?”

“So you didn’t hear anything at the portico?”

“I heard some women screaming but that’s none of my business.”

Vanya almost stumbled over the person laying in a white suit with cap which belonged to a summer uniform, and which had slipped off of his face upon which it had been placed, with his hands thrust under his head, sleeping on the shaded slope down towards the river. And he was very surprised when he recognised – by the bald patch, the pinched nose, the rare ginger beard and the on-the-whole rather small figure – his Greek teacher.

“Is that you here, Daniil Ivanovich?” said Vanya, forgetting on account of his amazement to even greet him.

“As you can see! But what’s got you so surprised, being as it is that you yourself are here, you’re also from Petersburg?”

“It’s that I’ve not met you before?”

“Very understandable, as I only arrived last night. Are you here with your family?” asked the Greek, finally sitting up and wiping his bald patch with a red-trimmed handkerchief. “Have a seat, it’s dark and windy.”

“Yes, my aunt and cousin are also here, but I live apart from them, with the Sorokins; maybe you’ve heard of them?”

“I’ve not had the pleasure so far. But it’s not bad here, it’s quite good enough: the Volga, gardens, and all the rest.”

“But where’s your cat and your thrush, are they with you?”

“No, I’m going to be travelling a long time, after all…”

And he began to recount with enthusiasm how he had perfectly unexpectedly received a little inheritance, took holiday and wanted to live out his lifelong dream: to travel to Athens, Alexandria, Rome, but while waiting for autumn, when it would be less hot for those southerly wanderings, he had gone along the Volga, stopping wherever he pleased, with a little suitcase and three or four beloved books.

“Currently, the most interesting excavations are taking place in Rome, Pompeii and Asia, and new works of ancient literally have been found there,” and the Greek, getting carried away and with a sparkle in his eyes, once again took off his jacket and spoke for a long time about his dreams, his delights, his plans and Vanya looked with sadness at the unlovely, but glowing with overflowing liveliness, face of the bald little Greek.

“Yes, it’s all interesting, all very interesting,” he said pensively once the latter had finished his account and started to smoke a cigarette.

“And will you be here until autumn?” Daniil Ivanovich suddenly remembered to ask.

“Probably. I’ll go to Nizhny Novgorod for the market and from there, home,” confessed Vanya, as though embarrassed by the paucity of his plans.

“So, are you satisfied? These Sorokins, are they interesting people?”

“On the whole they’re simple, but kind and welcoming,” again answered Vanya as he thought ill-disposedly towards these people who had suddenly become so foreign to him. “I’m so bored, really! You know, there’s nobody who’d not only be able to infect me with delight, but also simply understand and share the slightest movement of my soul,” suddenly escaped from Vanya, “both here, and, perhaps, in Petersburg.”

The Greek looked at him with a sharp eye.

“Smurov,” he began, somewhat solemnly, “you have a friend capable of valuing the highest outbursts of the soul and in whom you can always find sympathy and love.”

“Thank you, Daniil Ivanovich,” said Vanya, extending his hand to the Greek.

“It’s nothing,” the latter responded, “especially since as a matter of fact, I was not talking about myself.”

“Then who?”

“Larion Dmitriyevich.”

“Stroop?”

“Yes… Stop, don’t interrupt me. I know Larion Dmitriyevich very well, I saw him after that unfortunate incident and I testify that he was as guilty of that as you would be guilty if, for example, I drowned myself because you had blond hair. Of course, Larion Dmitriyevich, to the utmost degree, does not care what is said about him, but he expressed regret that some people very dear to him might change in their attitude towards him, and, among others, he named you. Keep that in mind, and also that he is now in Munich, in the Four Seasons hotel.”

“I’m not judging him, but I don’t need his address and if you came to communicate this to me, then you’re struggling in vain.”

“My friend, what dreadful conceit! Would I, an old man, take a detour to Vasilsursk on the way from Petersburg to Rome, just to tell Vanya Smurov Stroop’s address? I didn’t even know that you were here. You’re agitated, you’re not well, and I, like a good doctor, like a mentor, point out to you what you’re lacking – that life which for you was embodied in Stroop – that’s all.”

“How well-put-together you are, Vanechka!” said Sasha while undressing as he watched Vanya’s naked figure, still standing fully on the dry sand as he bent down to scoop up some water – to wet the crown of his head and his underarms before entering fully into the water. Vanya himself looked at the reflection, disrupted by the ripples dispersing in the water, of his tall, flexible body, with his narrow hips and long, slender legs, tanned from the bathing and the sun, of the light curls growing on his delicate cheek, of his big eyes in his round face, grown thin – and, silently smiling, stepped into the cold water. Sasha, short-legged despite his tall height, pale and chubby, plopped with a splash into the deep place.

Along the whole bank up until the herd were groups of bathing children, shrieking back and forth between the bank and the water, while here and there lay heaps of red shirts and underclothes, while further off, higher up, children and adolescents were also gleaming on the bright green, freshly-mown grass, with their delicately pink bodies reminiscent of paintings of heaven in the style of Thomas. Vanya, with an almost violent joy, felt how his body cleaved the cold depths of the water and with quick turns, like a fish, made the warmer surface foam. Having tired himself out, he swam on his back, not moving his arms, not knowing where he was going, seeing only the sky, sparkling from the sun. The intensifying shouts on the banks, growing distant as they headed off in the direction of the herd and the ploughing machinery, brought him back to consciousness.

They ran, putting their shirts on along the way, and towards their way came cries of, “They’ve caught him, they’ve caught him, they’re dragging him out!”

“What’s that?”

“The drowned man, he went under back in spring; they’ve only just found him now, he got caught on a log and couldn’t swim out,” the kids running with and overtaking them informed them.

From the hill came running, loudly sobbing, a woman in a red frock and white scarf; reaching the spot where the body was lain on a piece of burlap, she fell collapsed, face upon the sand and burst out sobbing, wailing in lament.

“Arina … the mother!” the whisper went round in a circle.

“Remember, I told you the biography of his life,” Sergei, who had come out of nowhere, kept repeating to Vanya, who regarded with horror the swollen, slimy corpse with a face already unformed, nude other than a single boot, disgusting and terrible under the bright sun and among noisy and curious children, whose tenderly pink bodies were visible through their unbuttoned shirts. “He was her only son, he wanted to go with the monks, three times he ran away, and worked hard to boot; they even beat him, nothing helped; kids buy gingerbread cakes and he would buy all these candles; there was a broad, a real piece of work, she got caught up here, he didn’t understand anything, but as soon as he did, off he went swimming with the lads and he drowned; all of 16 years old, he was…” Sergei’s tale reached him as though through water.

“Vanya! Vanya!” shrieked the woman piercingly, rising and falling again upon the sand at the sight of the swollen, slimy body.

Vanya broke off in horror into a run towards the hill, stumbling and pricking himself on the bushes and nettles, as he was not looking around, as though being chased hard at heel, and with a thumping heart and noise in his temples, he stopped only once he reached the Sorokins’ garden, where apples were gleaming red on the rarely planted apple trees, forests across the peaceful Volga were darkening, grasshoppers were chirruping in the grass, and it smelt of honey and mint geranium.

There are muscles, ligaments in the human body, that are impossible to look upon without awe, a recollection of Stroop’s words came over Vanya when, in horror, looked over himself in the mirror by candlelight, his thin, now fearfully pale, face, with the thin eyebrows and grey eyes, bright-red mouth and the curly hair on the thin cheek. He was not even surprised that at such a late hour, Maria Dmitriyevna came in unheard, quietly and tightly shutting the door behind her.

“What’ll it be, huh? What’s it going to be?” he flung at her. “They’ll sink and grow pale, my cheeks, my body will bloat and go all slimy, worms will eat my eyes, all the joints in this sweet body will come apart! But there are ligaments, muscles in the human body, that are impossible to look upon without awe! Everything will pass, it’ll all die! I don’t know anything, I haven’t seen anything, but I want to, I want… I’m not unfeeling, not some kind of stone; and now I know my own beauty! It’s terrible! Terrible! Who will save me?”

Maria Dmitriyevna, without surprise, watched Vanya with glee.

“Vanechka, darling mine, I pity you, pity you! I’ve been afraid of this moment, but it’s clear that the hour of the Lord’s will has come,” and, having unhurriedly put out the candle, she embraced Vanya and started to kiss him on the mouth, eyes, cheek, pressing him all the closer to her chest. Vanya, immediately snapped out of it, became hot, uncomfortable and cramped, and, liberating himself from the embrace, he quietly repeated with a completely different voice: “Maria Dmitriyevna, Maria Dmitriyevna, what’s wrong with you? Leave me alone, you mustn’t!” But she pressed him all the harder to her chest, quickly and inaudibly kissing him on the cheek, the mouth, the eyes, and whispered, “Vanechka, my darling, my joy!”

“Get off me already you repulsive old hag!” shouted Vanya finally, and, breaking away with all his strength from the woman embracing him, he ran out, slamming the door.

“What do I do now?” asked Vanya to Daniil Ivanovich, to whom he had run directly from his home during the night.

“The way I see it, you need to get on the road,” said his host, in a robe over his underwear and slippers.

“Where would I go, though? Surely not to Petersburg? They’ll ask why I’ve come back, that and I’ll get bored.”

“Yes, it’s inconvenient, but it’s not possible for you to stay here, you are completely ill.”

“What do I do?” repeated Vanya, looking on helplessly at the Greek drumming on the table.

“I, of course, don’t know your condition and means, how far you’ll be able to get; and you mustn’t go alone.”

“What do I do?”

“If you would believe my disposition towards you and not take into your head God knows what rubbish, then I would suggest, Smurov, that you come travelling with me.”

“Where?”

“Abroad.”

“I don’t have money.”

“We’d be alright; then, with time, we’ll work it out; we’d get to Rome and there it would become clear, with whom you should return and where I’ll travel further. That would be the best.”

“You can’t be serious, Daniil Ivanovich?”

“Never more so.”

“Surely that can’t be possible: me – in Rome?”

“Very much so, in fact!” smiled the Greek.

“I can’t believe it…” Vanya worried.

The Greek silently smoked a cigarette while smiling at Vanya.

“How great you are, how kind!” came Vanya’s outpouring.

“I am very glad to be travelling alone myself; of course, we will have to economise on the road, we won’t be staying in the most opulent of hotels, but in local inns.”

“Ah, that’ll be even better!” rejoiced Vanya.

And they spoke about the trip until morning, marking all the stops, cities and little places they would see along the way, laid their plans for tours, and, going outside in the bright sunlight, on the overgrown grass, Vanya was surprised that he was still in Vasil and that the Volga and dark forests beyond could still be seen.

[1] Ivan the Terrible

[2] A fruit preserve similar to jam but not as thick.

[3] 12th July by the Grigorian calendar (29th June by the old Julian calendar in use in Russia at the time)

[4] A type of open-topped horse drawn carriage

[5] A pre-revolutionary unit of distance, a little more than one kilometre.

[6] A compilation of hagiographies.

[7] I.e., what is now known as “Russia”; in the past the various East Slavic lands were sometimes called by variations on the word “Russia” – Little Russia (Ukraine), White Russia (Belarus), etc.

[8] A sect of Old Believer Don Cossacks

[9] I.e., not the Saint Peter who founded the Church in the first place, but rather the patron saint of Moscow (who, while in effect was the Metropolitan of Moscow, never held that title in practise, as it was not changed from ‘Metropolitan of Kiev and all Rus’’ until over 100 years after his death.

[10] A type of prayer rope once in common use in the Russian Orthodox Church, like rosaries are in Catholicism, now only used by Old Believers.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Ivan III

Ivan III de Russie (Ivan le Grand) fut le Grand Prince de Moscou et de Russie de 1462 à 1505. Ivan III vit le jour en 1440, fils du Grand Prince Vassili II de Moscou (r. de 1425 à 1462) et de son épouse, Maria Borovsk (c. 1420-1485). De 1450 à 1462, il remplit les fonctions de régent à la place de son père aveugle.

Lire la suite...

1 note

·

View note

Text

May 1, 2016

Prophet Jeremiah (6thBC); Right-believing Tamara, Queen of Georgia (13th); Venerable Paphnutius the abbot of Borovsk (1478); Martyr Vatas the Persian (4th); Hieromartyr Macarius, metropolitan of Kiev (1497); Venerable Ultan, founder of Fosse; New Martyrs Euthymius, Ignatius, and Acacius of Mt Athos (1814-1816)

Feast of Feasts: The Resurrection of our Lord, Holy Pascha

John 1.1-17

In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God. He was in the beginning with God; all things were made through him, and without him was not anything made that was made. In him was life, and the life was the light of men. The light shines in the darkness, and the darkness has not overcome it. There was a man sent from God, whose name was John. He came for testimony, to bear witness to the light, that all might believe through him. He was not the light, but came to bear witness to the light. The true light that enlightens every man was coming into the world. He was in the world, and the world was made through him, yet the world knew him not. He came to his own home, and his own people received him not. But to all who received him, who believed in his name, he gave power to become children of God; who were born, not of blood nor of the will of the flesh nor of the will of man, but of God. And the Word became flesh and dwelt among us, full of grace and truth; we have beheld his glory, glory as of the only Son from the Father. (John bore witness to him, and cried, “This was he of whom I said, ‘He who comes after me ranks before me, for he was before me.’”) And from his fulness have we all received, grace upon grace. For the law was given through Moses; grace and truth came through Jesus Christ.

Acts 1.1-8

In the first book, O Theophilus, I have dealt with all that Jesus began to do and teach, until the day when he was taken up, after he had given commandment through the Holy Spirit to the apostles whom he had chosen. To them he presented himself alive after his passion by many proofs, appearing to them during forty days, and speaking of the kingdom of God. And while staying with them he charged them not to depart from Jerusalem, but to wait for the promise of the Father, which, he said, “you heard from me, for John baptized with water, but before many days you shall be baptized with the Holy Spirit.” So when they had come together, they asked him, “Lord, will you at this time restore the kingdom to Israel?” He said to them, “It is not for you to know times or seasons which the Father has fixed by his own authority. But you shall receive power when the Holy Spirit has come upon you; and you shall be my witnesses in Jerusalem and in all Judea and Samaria and to the end of the earth.”

0 notes

Text

War between Ukraine and Russia: Latest news live | kyiv denounces that 8,600 Ukrainian children have been forcibly deported to Russian territory

War between Ukraine and Russia: Latest news live | kyiv denounces that 8,600 Ukrainian children have been forcibly deported to Russian territory

The Russian retiree who denounces the war in Ukraine through urban art

For 20 years, Russian retiree Vladimir Ovchinnikov became famous for his murals of Stalinist-era repression painted on the streets of the small town of Borovsk, about 115 kilometers southwest of Moscow. Just over a month after Russia invaded Ukraine, Ovchchik changed the subject for his new work, a job that put his freedom in…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

"Banksy of Borovsk," a Russian muralist, is waging his own war

“Banksy of Borovsk,” a Russian muralist, is waging his own war

An 84-year-old artist was standing in front of one of the many murals he has painted in his provincial hometown the other day when a group of young women walked by. They’d traveled some 60 miles from Moscow just to see his latest work, and they giggled at the encounter.

“This is so cool,” said one. “You are the main attraction of the city.”

Artist Vladimir A. Ovchinnikov has long covered the…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

‘Banksy of Borovsk,’ a Russian Muralist, Wages His Own War

‘Banksy of Borovsk,’ a Russian Muralist, Wages His Own War

An 84-year-old artist, defying Moscow’s crackdown on dissent, wants his country to acknowledge misdeeds both past and present.

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

In a Small Russian Town, a Pensioner's Street Art Denounces Ukraine Conflict : Inside US

In a Small Russian Town, a Pensioner’s Street Art Denounces Ukraine Conflict : Inside US

BOROVSK, Russia (Reuters) – Over 20 years, Russian pensioner Vladimir Ovchinnikov gained a following for his street murals in the small town of Borovsk, some 70 miles (115 km) southwest of Moscow, many of which depicted the plight of victims of Stalinist-era repressions.

But on March 25, just over a month after Russia sent tens of thousands of troops into Ukraine, Ovchinnikov created a new work,…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

Купить гидротестер на Авито в Боровск

https://www.avito.ru/borovsk?q=%D0%B3%D0%B8%D0%B4%D1%80%D0%BE%D1%82%D0%B5%D1%81%D1%82%D0%B5%D1%80

0 notes

Photo

Borovsk, Russia, October 2017

#35mm#35mm film#35mm photography#Black and White#fomopan 400#Street Photography#olympus mju-2#olympus mju ii#Russia#kaluga#Borovsk

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Мы приехали в Боровск всего на несколько часов и мне повезло застать его за работой. Владимир Александрович Овчинников. Художник. Почти 20 лет украшает город. Настенную живопись портят, закрашивают, сносят вместе с домами, а Владимир Александрович все равно рисует. Теперь его работы – часть города. Сюда специально едут «на посмотреть»! Посмотреть и почитать стихи соавтора и жены мастера Эльвиры Частиковой. Нам всем очень многое не нравится. Мы все очень многим недовольны. Мы все ругаем всех. А кто их НАС что-то сделал? Вот ОН – сделал. И мир вокруг стал лучше! ☝️😉👍#art #artwork #artist #streetart #russianstreetart #pic #streetpics #streetphotographyinternational #streetphoto #streetcolors #russianart #streetartist #traveltoRussia #photooftheday #borovsk #BorBorich67 #instasrt #instacolors #instaphotography #instapic #художник #уличноефото #уличноеискусство #боровск #картинка #уличныйхудожник #путешествиепороссии #Россия #фотодня #рисование https://www.instagram.com/p/B_DwM5uKPKt/?igshid=7tqj7paezr57

#art#artwork#artist#streetart#russianstreetart#pic#streetpics#streetphotographyinternational#streetphoto#streetcolors#russianart#streetartist#traveltorussia#photooftheday#borovsk#borborich67#instasrt#instacolors#instaphotography#instapic#художник#уличноефото#уличноеискусство#боровск#картинка#уличныйхудожник#путешествиепороссии#россия#фотодня#рисование

0 notes

Photo

St. Paphnutius of Borovsk, Mikhail Nesterov

102 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Borovsk, Kaluga oblast of Russia (1978)

#1970s#churches#Architecture#snow#wooden houses#soviet union#soviet#ussr#russia#history#photography#vintage#retro

926 notes

·

View notes