#berengaria of castile

Photo

La reina sin reino aborda la azarosa y compleja vida de Berenguela de Castilla, que fue reina consorte de León entre 1197 y 1204 por su matrimonio con el rey Alfonso IX, quien convocara las primeras Cortes de Europa; un matrimonio anulado por el papa Inocencio II ya que los cónyuges eran parientes en tercer grado.

Al morir su hermano Enrique siendo solo un niño, los derechos dinásticos del reino de Castilla pasaron a Berenguela, que los traspasó a Fernando, uno de los hijos que tuvo con Alfonso IX y a quien Berenguela protegió y aconsejó a lo largo de toda su vida. Uno de los hechos más conocidos de este periodo es el que se refiere al final del Reino de León como estado medieval independiente: en 1230, antes de fallecer, Alfonso IX designa como herederas al trono leonés a sus hijas Sancha y Dulce, frutos de su primer matrimonio con Teresa de Portugal, en detrimento de los derechos de Fernando III. Berenguela se reunió en la villa de Benavente con la madre de las infantas y consiguió la firma de lo que se ha dado en llamar «la concordia de Benavente», por el que estas renunciaban al trono en favor de su hermanastro a cambio de dinero y otras ventajas.

«en una jugada maestra, Berenguela, con audacia y sentido de la oportunidad, consigue que su hijo Fernando, apenas un adolescente, sea proclamado rey. Este movimiento desencadenará tanto oposiciones como adhesiones que la astuta Berenguela sabrá manejar siempre a favor de la dinastía y de Fernando III, el Santo, quien estará destinado a culminar la Reconquista para el reino de Castilla».

5 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hello. I was reading about a Queen consort/technically queen regnant named berengaria of Castile who had her marriage annulled by the pope due to consanguinity. However, the pope decided that the children they had during their marriage were still legitimate and were still able to inherit both parents’ lands. I was thinking about writing a story based on this scenario, but one of the things I wanted to change was having the king or queen marry other people after her annulment. If they did remarry, would that cause any problems from their children in their first marriage? Even if her kids were still deemed legitimate, would anyone kick up a fuss about their parent’s marriage being annulled as a way to prevent them from inheriting over any children from a future marriage?

No, if the pope insists they are legitimate any children their parents have would come after them in succession.

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Blanche, Marguerite, and Queenship

Blanche's actions as queen dowager amount to no more than those of her grandmother and great-grandmother. A wise and experienced mother of a king was expected to advise him. She would intercede with him, and would thus be a natural focus of diplomatic activity. Popes, great Churchmen and great laymen would expect to influence the king or gain favour with him through her; thus popes like Gregory IX and Innocent IV, and great princes like Raymond VII of Toulouse, addressed themselves to Blanche. She would be expected to mediate at court. She had the royal authority to intervene in crises to maintain the governance of the realm, as Blanche did during Louis's near-fatal illness in 1244-5, and as Eleanor did in England in 1192.

In short, Blanche's activities after Louis's minority were no more and no less "co-rule" than those of other queen dowagers. No king could rule on his own. All kings- even Philip Augustus- relied heavily on those they trusted for advice, and often for executive action. William the Breton described Brother Guérin as "quasi secundus a rege"- "as if second to the king": indeed, Jacques Krynen characterised Philip and his administrators as almost co-governors. The vastness of their realms forced the Angevin kings to rely even more on the governance of others, including their mothers and their wives. Blanche's prominent role depended on the consent of her son. Louis trusted her judgement. He may also have found many of the demands of ruling uncongenial. Blanche certainly had her detractors at court, but she was probably criticsed, not for playing a role in the execution of government, but for influencing her son in one direction by those who hoped to influence him in another.

The death of a king meant that there was often more than one queen. Blanche herself did not have to deal with an active dowager queen: Ingeborg lived on the edges of court and political life; besides, she was not Louis VIII's mother. Eleanor of Aquitaine did not have to deal with a forceful young queen: Berengaria of Navarre, like Ingeborg, was retiring; Isabella of Angoulême was still a child. But the potential problem of two crowned, anointed and politically engaged queens is made manifest in the relationship between Blanche and St Louis's queen, Margaret of Provence.

At her marriage in 1234 Margaret of Provence was too young to play an active role as queen. The household accounts of 1239 still distinguish between the queen, by which they mean Blanche, and the young queen — Margaret. By 1241 Margaret had decided that she should play the role expected of a reigning queen. She was almost certainly engaging in diplomacy over the continental Angevin territories with her sister, Queen Eleanor of England. Churchmen loyal to Blanche, presumably at the older queen’s behest, put a stop to that. It was Blanche rather than Margaret who took the initiative in the crisis of 1245. Although Margaret accompanied the court on the great expedition to Saumur for the knighting of Alphonse in 1241, it was Blanche who headed the queen’s table, as if she, not Margaret, were queen consort. In the Sainte-Chapelle, Blanche of Castile’s queenship is signified by a blatant scattering of the castles of Castile: the pales of Provence are absent.

Margaret was courageous and spirited. When Louis was captured on Crusade, she kept her nerve and steadied that of the demoralised Crusaders, organised the payment of his ransom and the defence of Damietta, in spite of the fact that she had given birth to a son a few days previously. She reacted with quick-witted bravery when fire engulfed her cabin, and she accepted the dangers and discomforts of the Crusade with grace and good humour. But her attempt to work towards peace between her husband and her brother-in-law, Henry III, in 1241 lost her the trust of Louis and his close advisers — Blanche, of course, was the closest of them all - and that trust was never regained. That distrust was apparent in 1261, when Louis reorganised the household. There were draconian checks on Margaret's expenditure and almsgiving. She was not to receive gifts, nor to give orders to royal baillis or prévôts, or to undertake building works without the permission of the king. Her choice of members of her household was also subject to his agreement.

Margaret survived her husband by some thirty years, so that she herself was queen mother, to Philip III, and was still a presence ar court during the reign of her grandson Philip IV. But Louis did not make her regent on his second, and fatal, Crusade in 1270. In the early 12605 Margarer tried to persuade her young son, the future Philip III, to agree to obey her until he was thirty. When Philip told his father, Louis was horrified. In a strange echo of the events of 1241, he forced Philip to resile from his oath to his mother, and forced Margaret to agree never again to attempt such a move. Margaret had overplayed her hand. It meant that she was specifically prevented from acting with those full and legitimate powers of a crowned queen after the death of her husband that Blanche, like Eleanor of Aquitaine, had been able to deploy for the good of the realm.

Why was Margaret treated so differently from Blanche? Were attitudes to the power of women changing? Not yet. In 1294 Philip IV was prepared to name his queen, Joanna of Champagne-Navarre, as sole regent with full regal powers in the event of his son's succession as a minor. She conducted diplomatic negotiations for him. He often associated her with his kingship in his acts. And Philip IV wanted Joanna buried among the kings of France at Saint-Denis - though she herself chose burial with the Paris Franciscans. The effectiveness and evident importance to their husbands of Eleanor of Provence and Eleanor of Castile in England led David Carpenter to characterise late thirteenth-century England as a period of ‘resurgence in queenship’.

The problem for Margaret was personal, rather than institutional. Blanche had had her detractors at court. It is not clear who they were. There were always factions at courts, not least one that centred around Margaret, and anyone who had influence over a king would have detractors. They might have been clerks with misgivings about women in general, and powerful women in particular, and there may have been others who believed that the power of a queen should be curtailed, No one did curtail Blanche's — far from it. By the late chirteenth century the Capetian family were commissioning and promoting accounts of Louis IX that praise not just her firm and just rule as regent, but also her role as adviser and counsellor — her continuing influence — during his personal rule. As William of Saint-Pathus put it, because she was such a ‘sage et preude femme’, Louis always wanted ‘sa presence et son conseil’. But where Blanche was seen as the wisest and best provider of good advice that a king could have, a queen whose advice would always be for the good of the king and his realm, Margaret was seen by Louis as a queen at the centre of intrigue, whose advice would not be disinterested.

Surprisingly, such formidable policical players at the English court as Simon de Montfort and her nephew, the future Edward I, felt that it was worthwhile to do diplomatic business through Margaret. Initially, Henry III and Simon de Montfort chose Margaret, not Louis, to arbitrate between them. She was a more active diplomat than Joinville and the Lives of Louis suggest, and probably, where her aims coincided with her husband’s, quite effective.

To an extent the difference between Blanche’s and Margaret’s position and influence simply reflected political reality. Blanche was accused of sending rich gifts to her family in Spain, and advancing them within the court. But there was no danger that her cultivation of Castilian family connections could damage the interests of the Capetian realm. Margaret’s Provençal connections could. Her sister Eleanor was married to Henry III of England. Margaret and Eleanor undoubtedly attempted to bring about a rapprochement between the two kings. This was helpful once Louis himself had decided to come to an agreement with Henry in the late 1250s, but was perceived as meddlesome plotting in the 1240s. Moreover, Margaret’s sister Sanchia was married to Henry's younger brother, Richard of Cornwall, who claimed the county of Poitou, and her youngest sister, Beatrice, countess of Provence, was married to Charles of Anjou. Sanchia’s interests were in direct conflict with those of Alphonse of Poitiers; and Margaret herself felt that she had dowry claims in Provence, and alienated Charles by attempting to pursue them. Indeed, her ill-fated attempt to tie her son Philip to her included clauses that he would not ally himself with Charles of Anjou against her.

Lindy Grant- Blanche of Castile, Queen of France

#xiii#lindy grant#blanche of castile queen of france#blanche de castille#grégoire ix#innocent iv#raymond vii de toulouse#aliénor d'aquitaine#louis ix#philippe ii#guérin#louis viii#marguerite de provence#aliénor de provence#alphonse de poitiers#henry iii of england#philippe iii#jeanne i de navarre#philippe iv#simon de montfort#edward i of england#jean de joinville#sancia de provence#béatrice de provence#charles i d'anjou

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

Browsing the shelves at York City Library. Am happy to report that the section where the history books are kept is nice and peaceful!

The queens related to the Norman Conquest during the period 1066 to 1167 were:

Matilda of Flanders (William I 'the Conqueror)

Matilda of Scotland (1st wife of Henry I)

Adeliza of Lovain (2nd wife of Henry I)

Matilda of Boulogne (Stephen)

The Empress Maud (daughter of Henry I and wife of (i) Heinrich V Holy Roman Emperor & (ii) Geoffrey 'Plantagenet')

The queens of the Crusades during the period 1154 to 1291 were:

Eleanor of Aquitaine (Henry II)

Berengaria of Navarre (Richard I)

Isabella of Angouleme (John)

Alienor of Provence (Henry III)

Eleanor of Castile (Edward I)

CHECK OVERLAP BETWEEN 1154 & 1167.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Henry III of England: Alright, everything is good and calm. I am FINE-

Blanche of Castile, standing behind him with a metal folding chair:

Berengaria of Castile: Yep, everything is a just peachy.

Otto IV: Uh…hey cousin-

Marie of Champagne, covering Otto’s mouth: Hush, I wanna watch this.

Eleanor of Brittany, sitting there with popcorn and 3D glasses: :)

#welcome to the Plantagenet cousins smackdown#they all love each other but Blanche would beat Henry’s ass any day

1 note

·

View note

Photo

the granddaughters of henry ii and eleanor of aquitaine

#historyedit#history#eleanor of aquitaine#isabella of england#joan lady of wales#joan of england#matilda of saxony#matilda of england#eleanor of england#eleanor of castile#berengaria of castile#urraca of castile#blanche of castile#eleanor fair maid of brittany#malafda of castile#12th century#13th century#english history#british history#scottish history#spanish history#welsh history#our edits#by julia#german history#sicilian history#italian history#portuguese history

306 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Berengaria ( 1179 or 1180 – 8 November 1246) was queen regnant of Castile in 1217 and queen consort of León from 1197 to 1204. As the eldest child and heir presumptive of Alfonso VIII of Castile, she was a sought after bride, and was engaged to Conrad, the son of Holy Roman Emperor Frederick I Barbarossa. After his death, she married her cousin, Alfonso IX of León, to secure the peace between him and her father. She had five children with him before their marriage was voided by Pope Innocent III.

When her father died, she served as regent for her younger brother Henry I in Castile until she succeeded him on his untimely death. Within months, she turned Castile over to her son, Ferdinand III, concerned that as a woman she would not be able to lead Castile's forces. However, she remained one of his closest advisors, guiding policy, negotiating, and ruling on his behalf for the rest of her life. She was responsible for the re-unification of Castile and León under her son's authority, and supported his efforts in the Reconquista. She was a patron of religious institutions and supported the writing of a history of the two countries.

6 notes

·

View notes

Photo

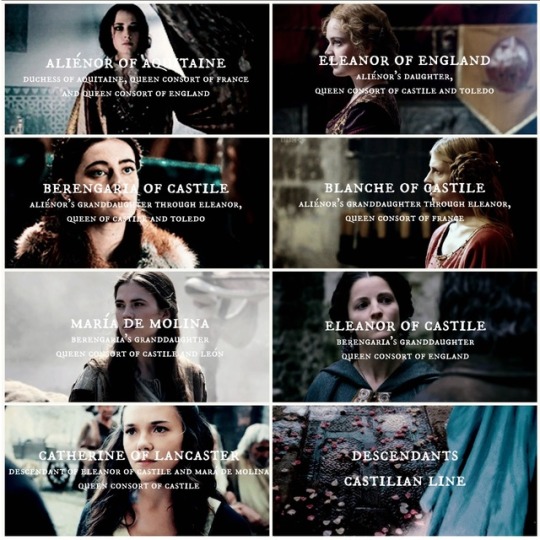

Aliénor of Aquitaine’s female descendants | Castilian line

«Your crown has been bought and paid for. Put it on your head and wear it».

− Maya Angelou

#eleanor of aquitaine#leonor of england#eleanor of england#berengaria of castile#berenguela of castile#blanche of castile#maria de molina#eleanor of castile#catherine of lancaster#plantagenets#house of ivrea#aliénor of aquitaine#kings and queens of castile#kings and queens#kings and queens of england#england#castile

202 notes

·

View notes

Photo

“There were very few queens like Berenguela. There were not many kings like her either. She deserves to be reinstated to the place she earned in the pantheon of medieval monarchs, for the history of Iberia, of Europe, and of the Middle Ages was as much the work of women’s hands as men’s. “- Janna Bianchini, The Queen's Hand

She was the eldest daughter of King Alfonso VIII of Castile and Eleanor of England. Many of the children born later to the couple died shortly after birth or in early infancy, and so Berenguela became a greatly desired bride throughout Europe. Berenguela's first engagement was agreed in 1187 when her hand was sought by Duke Conrad of Swabia, the fifth child of Holy Roman Emperor Frederick I Barbarossa. The marriage was not consummated, due to Berenguela's young age, as she was less than 10 years old. By 1191, she requested an annulment of the engagement from the pope but the duke’s assassination in 1196 finalized the situation. In 1197, it was decided that Berenguela should marry her father’s cousin King Alfonso IX of León in an effort to bring peace to the two kingdoms. After seven years of marriage and five children, their marriage was voided by Pope Innocent III due to consanguinity. Berenguela returned to Castile and to her parents, where she dedicated herself to the care of her children.

After her father’s death in 1214, Berenguela was regent for her younger brother Enrique I of Castile until internal strife, instigated by the nobility, forced her to cede regency and guardianship to Count Alvaro Núñez de Lara. By May 1216, the situation in Castile had grown perilous for Berenguela, so she decided to take refuge in the castle of Autillo de Campos and sent her son Fernando to the court of his father. Circumstances changed suddenly when King Enrique died on 6 June 1217, after receiving a head wound from a tile which came loose while he was playing with other children at the palace of the bishop of Palencia. The new sovereign was well aware of the danger her former husband posed to her reign; being her brother's closest agnate, it was feared that he would claim the crown for himself. Therefore, Queen Berenguela kept her brother's death and her own accession secret from Alfonso IX of León. She wrote to Alfonso asking that Fernando be sent to visit her, and then abdicated in their son's favour on 31 August. In part, she abdicated as she would be unable to be the military leader Castile needed its king to be in that time.

Although she did not reign for long, Berenguela continued to be her son's closest advisor, intervening in state policy, albeit in an indirect manner. Well into her son's reign, contemporary authors wrote that she still wielded authority over him. Berenguela’s political acumen helped quell the rebellious nobles and provided her son with crucial support in his crusade against the Muslims of Al-Andalus. Berenguela communicated with, negotiated with, and advised other rulers across Europe, including a succession of popes, the queen of France, and the Latin Emperor of Constantinople. She arranged the marriage of her son Fernando III of Castile with Beatriz of Swabia, and her daughter Berenguela to John of Brienne, a maneuver which brought Fernando III closer to the throne of León, since John was the candidate Alfonso IX had in mind to marry his eldest daughter Sancha. By proceeding more quickly, Berenguela prevented the daughters of her former husband from marrying a man who could claim the throne of León.

Perhaps her most decisive intervention on Fernando's behalf took place in 1230, when Alfonso IX died and designated as heirs to the throne his daughters Sancha and Dulce from his first marriage to Theresa of Portugal, superseding the rights of Fernando III. Berenguela met with the princesses' mother and succeeded in the ratification of the Treaty of las Tercerías, by which they renounced the throne in favor of their half-brother in exchange for a substantial sum of money and other benefits.Thus were the thrones of León and Castile re-united in the person of Fernando III.

She intervened again by arranging the second marriage of her son with a French noblewoman, Joan of Dammartin, a candidate put forth by Berenguela's sister Blanche of France. Berenguela served again as regent, ruling while Fernando was in the south on his long campaigns of the Reconquista. She governed Castile and León with her characteristic skill, relieving him of the need to divide his attention during this time. She is portrayed as a wise and virtuous woman by the chroniclers of the time. Much like her mother, Berenguela was a strong patroness of religious institutions. She was also concerned with literature and history, charging Lucas de Tuy to compose a chronicle on the Kings of Castile and León to aid and instruct future rulers of the joint kingdom. The necrology of Las Huelgas gives November 8, 1246, as the date of Queen Berenguela’s death. Her son was canonized as St. Fernando by Pope Clement X in 1671. (x)(x)(x)

144 notes

·

View notes

Text

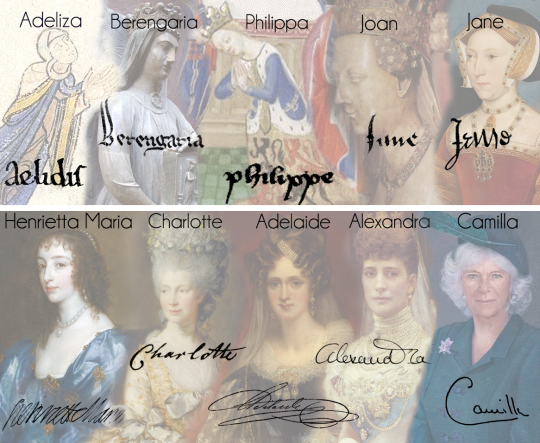

The Queens of England (3/7)

Queen consorts and queen regnants of England from 856 to present day

#eleanor of aquitaine#margaret of france#berengaria of navarre#isabella of angoulême#eleanor of provence#eleanor of castile#isabella of france#philippa of hainault#anne of bohemia#history#historical women#gif#gifset

115 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Queens of the Crusades follows the lives of five of England's Queens: Eleanor of Aquitaine (Henry II), Berengaria of Navarre (Richard I), Isabella of Angoulême (John I), Eleanor (Alienor) of Provence (Richard III), and Eleanor of Castile (Edward I) -- Yes lots of Eleanors. The book uses primary sources and other research (mostly Mathew Paris) to tell the story of these five queens.

The majority of the book focuses on two of them: the formidable Eleanor of Aquitaine and the ambiguous Eleanor of Castile. In fact, the first third of the book is devoted to Eleanor of Aquitaine which can be good or bad depending on your tastes. I personally would have liked a bit more time spent on the other queens... particularly Isabella, but that is me.

The book is told in Weir's incredibly readable style. And it's easy for the armchair historian to pick up and follow along with. While there's a lot of very interesting information in this book, readers need to be aware that there is some unstated bias in the prose and some theories/facts which are in dispute. It's a good start for people looking for more information about these queens who have exhausted Wikipedia but it's really only a start.

There were also some odd tangents at times that didn't seem to fit with the rest of the narrative and felt shoehorned in because they were interesting tidbits but didn't relate fully to the information at hand.

In all, I am torn about what to rate this book. It's readable. It's approachable. But there's a lack of context provided to some of the sources and Weir's bias is present but it's not stated or acknowledged. There's also the potential for confusion regarding the names in this book. Maud is used instead of Mathilda for Henry II's mother. Alienor is used for Eleanor of Provence. At several points, I had to pause to check to make sure that the name in question was a viable one and that lessened my reading enjoyment. I'm not a fan of fact-checking my non-fiction, and I needed to fact check much of this book. Additionally, I also felt that the book was uneven. The section on Eleanor of Aquitaine was far and away the best and most in depth. However the section on Berengaria of Navarre felt lacking.

If you're a fan of Weir's work, you're going to enjoy this. If you aren't, I'd give it a miss. If you're new to the subject, then this is a good starting point and something light and easy to read.

In all, I liked and disliked parts of this book. And for that I give this:

Three Stars

If this is your jam, you can get it here.

If you like these kind of honest reviews, please consider supporting us here!

I received an ARC of this book via NetGalley

#book review#historical nonfiction#eleanor of aquitaine#eleanor of castile#berengaria of navarre#historical queens#english queens#alison weir#there's some inaccuracies and unacknowledged bias#there's good in here too#but it's hit and miss#three stars#Rose and Lark review books#I don't have a hate-on for Alison Weir like some people#She's not a trained historian and that bugs some people#It doesn't bug me#I just want her to admit her biases and check her sources#you don't have to go to oxford to be a historian#or have to spend years in school#that's just elitist#and this is a hill I will die on

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Queen Consorts of England by name

Anne of Bohemia (1366-1394), first wife of Richard II

Anne Neville (1456-1485), wife of Richard III

Anne Boleyn (c. 1501-1536), second wife of Henry VIII

Anne of Cleves (1515-1557), fourth wife of Henry VIII

Anne of Denmark (1574-1619), wife of James I

Catherines:

Catherine of Valois (1401-1437), wife of Henry V

Catherine of Aragon (1485-1536), first wife of Henry VIII

Catherine Howard (1524-1542), fifth wife of Henry VIII

Catherine Parr (1512-1548), sixth wife of Henry VIII

Catherine of Braganza (1638-1705), wife of Charles II

Elizabeths:

Elizabeth Woodville (1437-1492), wife of Edward IV

Elizabeth of York (1456-1503), wife of Henry VII

Elizabeth Bowes-Lyon (1900-2002), wife of George VI

Isabellas:

Isabella of Angouleme (1187-1246), second wife of King John

Isabella of France (1285-1358), wife of Edward II

Isabella of Valois (1387-1409), second wife of Richard II

Eleanors:

Eleanor of Aquitaine (1122-1204), wife of Henry II

Eleanor of Provence (1223-1291), wife of Henry III

Eleanor of Castile (1241-1290), first wife of Edward I

Matildas:

Matilda of Flanders (1031-1083), wife of William I

Matilda of Scotland (1080-1118), first wife of Henry I

Matilda of Boulogne (1105-1152), wife of King Stephen

Margarets:

Margaret of France (1282-1317), second wife of Edward I

Margaret of Anjou (1430-1482), wife of Henry VI

Carolines:

Caroline of Ansbach (1683-1737), wife of George II

Caroline of Brunswick (1768-1821), wife of George IV

Marys:

Mary of Modena (1658-1718), second wife of James II

Mary of Teck (1867-1953), wife of George V

Others:

Adeliza of Louvain (1103-1151), second wife of Henry I

Berengaria of Navarre (c. 1165-1230), wife of Richard I

Philippa of Hainault (1314-1369), wife of Edward III

Joan of Navarre (1370-1457), second wife of Henry IV

Jane Seymour (1509-1537), third wife of Henry VIII

Henrietta Maria of France (1609-1669), wife of Charles I

Charlotte of Mecklenburg-Strelitz (1744-1818), wife of George III

Adelaide of Saxe-Meiningen (1792-1849), wife of William IV

Alexandra of Denmark (1844-1925), wife of Edward VII

Camilla Parker Bowles (1947- ), second wife of Charles III

Annes:

#When I couldn't find a signature I used a document that used their name#Henrietta Maria was officially called Queen Mary but she didn't use the name herself#Normans#Plantagenets#Tudors#Stuarts#Hanoverians#Windsors#I can't believe I found Adeliza's name written down I am hella stoked

574 notes

·

View notes

Text

i have now put the ai to work generating characters for my next project, which is a Court Intrigue Drama Thing, which has resulted in such classics as:

a character named “all the people of naples”

"Duke Rodrigo of Castille: Duke Nuno of Castille's brother, and a man who jealously manages his daughter's affairs. Hates Duke Rodrigo of Castille to the extent that he completely severed ties with him after he married Claudia of Castille, and is one of the few people who is genuinely happy that the Duke has finally gone."

a million dukes of castille apparently

a priest described only as "Around fourty years old and with a name like a type of cheese"

"A Castilian Captain of the Guard who is of service to the duke of Naples and a man who is not notably close to or loyal to anyone. But quite honestly, who can blame him?"

"easy to manipulate and incredibly annoying. Berengaria and Froila are terrified of him because he actually loves them and would risk his life for them, breaking every rule of being a good prince ever written."

king ferdinand. he keeps popping up in the descriptions of other characters but i don’t know who he is or what it is that he is the king of

"when he's not drinking, he's drinking wine"

either about five different men are berengaria’s father or there are a whole host of berengarias

"Is not particularly sneaky and normally manages her way through life by talking loudly."

"Ormella's mother, which is nice."

about ten guys, all with a description just reading “Meh.”, in a row

people designated first, second, third, and fourth choruses. i do not know why.

“A weirdo trader and entrepreneur, a woman who befriends Berengaria and becomes a cross between a mom and a weird aunt.“ (this one is my favourite)

#ollie considers#text#ollie writes#thank you this has been Automatically Generated Guys with me your host

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Queen consorts of England and Britain | [19/50] | Berengaria of Navarre

Berengaria was Queen consort of England from 1191 until 1199 as the wife of Richard I. She was born sometime between 1165 and 1170 as the daughter of Sancho VI of Navarre and Sancha of Castile. Through her mother, she was the first cousin of Margaret of France, wife of Henry the Young King who was the older brother of Berengaria’s husband, Richard. In 1190, Berengaria was betrothed to King Richard of England, however the betrothal had to be kept secret as Richard was already betrothed to someone else. Shortly afterwards, Richard requested that Berengaria be brought to him as he was already off on the Third Crusade. Berengaria travelled with Richard’s mother, Eleanor of Aquitaine, and after a long and difficult journey they finally arrived in Sicily during lent. Berengaria was left in the care of Richard’s sister, Joan, who was the Dowager Queen of Sicily. While en route to the Holy Land, Joan and Berengaria’s ship ran aground off the coast of Cyprus and they were captured. Eventually, they were rescued by Richard and he and Berengaria were married on 12 May 1191, with Berengaria being crowned the same day, officially making her Queen consort of England. Berengaria is known as the only English queen never to set foot in the country as she spent her entire tenure as consort living in Richard’s French holdings. It’s been speculated whether or not the marriage was actually consummated and Richard was very neglectful of Berengaria for the first several years of their marriage. Eventually, Pope Celestine III had to order Richard to return to his wife, to which he complied. He returned to France where Berengaria was living and would take her to church every week thereafter. Richard died in 1199 and Berengaria was distressed about this, leading some to speculate that she genuinely loved Richard while others have argued that she was simply upset over having been neglected as Queen. Although she never visited England as Queen, she did send envoys to England in order to get what was owed to her as Queen dowager. Richard’s brother, John who succeeded him, had refused to pay her what she was due and, eventually, John’s mother, Eleanor, and the Pope had to intervene and John was forced to pay—although he still owed her £4,000 at the time of his death and it wasn’t until the reign of his son, Henry III that the entire debt was finally paid off. After Richard’s death, Berengaria spent the rest of her life living quietly in France where she eventually died on 23 December 1230.

21 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Sancho III, rey de Castilla. By José Castelaro y Perea.

King Sancho III (1134–1158), called ”the Desired”, was King of Castile and Toledo for one year, from 1157 to 1158. He was the son of Alfonso VII of León and Castile and his wife Berengaria of Barcelona, and was succeeded by his son Alfonso VIII. His nickname was due to his position as the first child of his parents, born after eight years of childless marriage.

During his reign, the Order of Calatrava was founded.

#José Castelaro y Perea#monarquia española#reyes de españa#reyes de castilla#rey de castilla#kingdom of castile#spain in the middle ages#house of ivrea#casa de borgoña#king sancho iii

7 notes

·

View notes

Photo

queens and empresses regnant who lost their crowns

↳ requested by anonymous

#historyedit#perioddramaedit#history#irene of athens#berengaria of castile#theodora of trebizond#charlotte of cyprus#mary queen of scots#christina of sweden#ranavalona iii#Lili'uokalani#our edits#by nadz#byzantine history#greek history#Spanish History#cypriot history#Scottish history#swedish history#malagasy history#Hawaiian History#8th century#13th century#15th century#16th century#17th century#19th century

1K notes

·

View notes