#ben lerner

Quote

She said she hoped she would see me again, and the next thing I knew I was running through light snow back to my dorm, laughing aloud from an excess of joy like the schoolboy that I was. I had overwhelming sense of the world's possibility and plenitude; the massive, luminous spheres burned above me without irony; the streetlights were haloed and I could make out the bright, crustal highlands of the moon, the far-sprinkled systems; I was going to read everything and invent a new prosody and successfully court the radiant progeny of the vanguard doyens if it killed me; my mind and body were as a fading coal awakened to transitory brightness by her breath when she'd brushed her lips against me; the earth was beautiful beyond all change.

Ben Lerner, 10:04

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

my second ben lerner book — charming, self-affacing without being insincere, with traces of what eventually became the hatred of poetry, committed to poetry without being able to define it, drifting but not aimlessly, and so, so funny

#booklr#books#books and reading#studyblr#bookblr#book blog#aesthetic#aes#reading#bookstagram#literature#coffeeblr#written extracts i like#ben lerner#granta#studysthetics#home#study aesthetic#coffee aesthetic

303 notes

·

View notes

Text

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Art has to offer something other than stylized despair.”

― Ben Lerner

#Ben Lerner#reading#literature#quotes#life#life quotes#quote#world#random beautiful stuff that i read#random quotes#stumbling on random beautiful quotes

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sometimes what you see belongs to another world. Stars. City streets on a movie screen. The remembered face of someone gone. You know it is another world because you cannot touch what you see, or because it cannot see you.

Kamran Javadizadeh from “Ben Lerner’s Long Search for Contact”

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

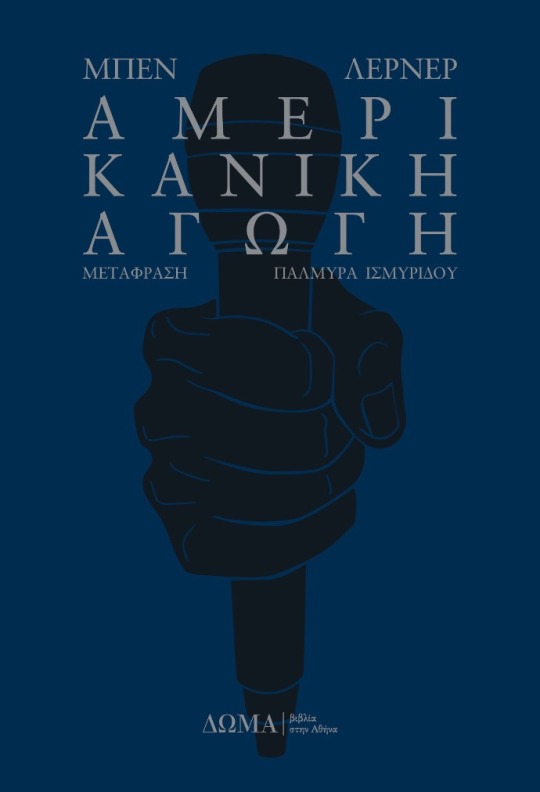

Τέλη της δεκαετίας του ’90 και, παρά το υποτιθέμενο «τέλος της Ιστορίας» και το θρίαμβο του φιλελευθερισμού, τα νεαρά αρσενικά της βαθιάς Αμερικής δείχνουν αποπροσανατολισμένα. Ο εκνευρισμός είναι διάχυτος, οι ρωγμές εμφανείς. Επικρατεί ο φόβος ότι μια μεγάλη βία όπου νά ’ναι θα ξεσπάσει.

Ο Άνταμ Γκόρντον, τελειόφοιτος του Λυκείου της Τοπήκα, προσπαθεί να μάθει πώς ένα αγόρι γίνεται άντρας. Μέσα απ’ τους αγώνες ρητορικής, τις μονομαχίες ραπ αυτοσχεδιασμού, τις ψυχαναλυτικές συνεδρίες, ο Άνταμ έχει προλάβει να καταλάβει πως η γλώσσα δεν είναι εργαλείο χαλιναγώγησης της βίας. Η γλώσσα είναι όπλο.

Ανενδοίαστα εξομολογητική και απροκάλυπτα πολιτική, η Αμερικανική αγωγή παρουσιάζει την ιστορία μιας οικογένειας σε μια εποχή σιωπηρών τεκτονικών μετατοπίσεων, μια ακτινογραφία της κουλτούρας της τοξικής αρρενωπότητας, και μια αρχαιολογία της ανόδου της νέας Δεξιάς, αναζητώντας χαμηλόφωνα έναν τρόπο ώστε να μάθουν οι άνθρωποι «και πάλι, αργά-αργά, πώς να μιλούν, μέσα στο γενικό σφυροκόπημα».

ΔΥΟ ΛΟΓΙΑ ΓΙΑ ΤΟΝ ΣΥΓΓΡΑΦΕΑ: Ο Ben Lerner (1979) γεννήθηκε στην Τοπήκα του Κάνσας. Έχει δημοσιεύσει τρία βιβλία ποίησης, τρία μυθιστορήματα, και ένα βιβλίο κριτικής. Ήταν φιναλίστ για το βραβείο Pulitzer, το National Book Award και το National Book Critics Circle Award. Έχει λάβει υποτροφίες από τα ιδρύματα Fulbright, Guggenheim και MacArthur. Είναι καθηγητής αγγλικής φιλολογίας στο Brooklyn College.

Daily inspiration. Discover more photos at Just for Books…?

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

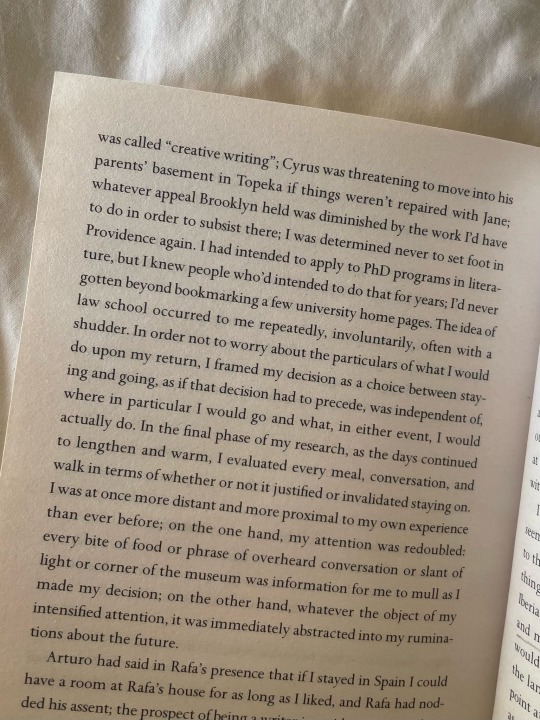

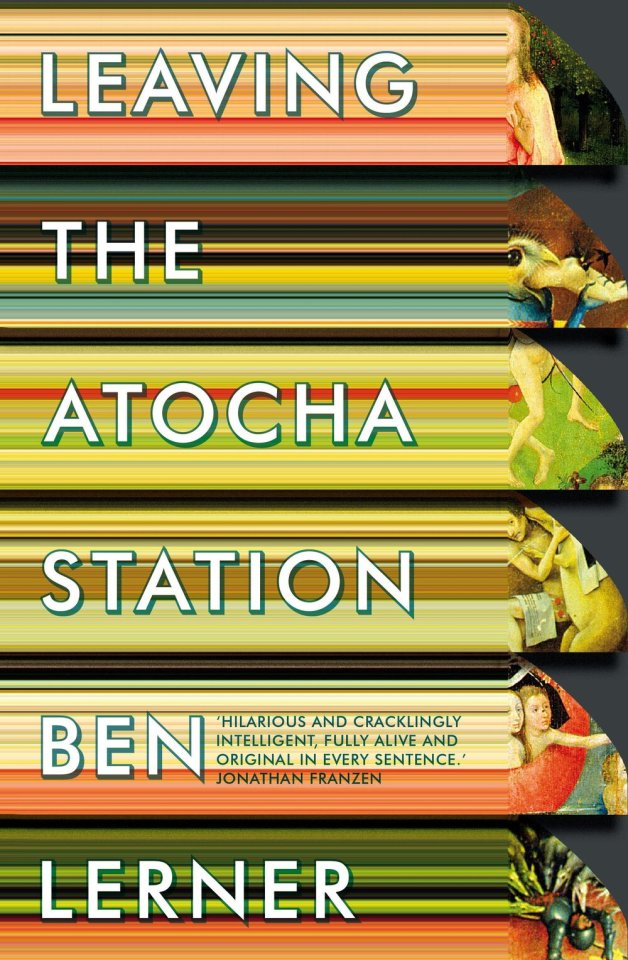

Leaving the Atocha Station

by Ben Lerner

Veering between the comic and tragic, the self-contemptuous and the inspired, Leaving the Atocha Station is a dazzling introduction to one of the smartest, funniest and most audacious writers of a generation.

Adam Gordon is a brilliant, if highly unreliable, young American poet on a prestigious fellowship in Madrid, struggling to establish his sense of self and his attitude towards art. Fuelled by strong coffee and self-prescribed tranquillizers, Adam's 'research' soon becomes a meditation on the possibility of authenticity, as he finds himself increasingly troubled by the uncrossable distance between himself and the world around him. It's not just his imperfect grasp of Spanish, but the underlying suspicion that his relationships, his reactions, and his entire personality are just as fraudulent as his poetry.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

When the Internet came back at the first stop in Manhattan, I Googled the lanternflies the radio had told us all to kill on sight and read: 'The tree of heaven is a preferred host.' When everything is poetry I know I am unwell.

"The Ferry," Ben Lerner

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

And when I felt I finally mastered a word, when I could slide it into a sentence with a satisfying click, that wasn't poetry anymore -- that was something else, something functional within a world, not the liquefaction of its limits.

Ben Lerner, The Hatred of Poetry

2 notes

·

View notes

Quote

Think about how often — before cell phones, before any kind of caller ID — you answered the landline as a child and had to have an exchange, however brief, with aunts or uncles or family friends. Even if it was that five-second check-in, How are you doing, how is school, is your mom around — it meant periodic real-time vocal contact with an extended community, which, through repetition, it reinforced.

Ben Lerner, The Topeka School

338 notes

·

View notes

Text

Leaving the Atocha Station, Ben Lerner

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

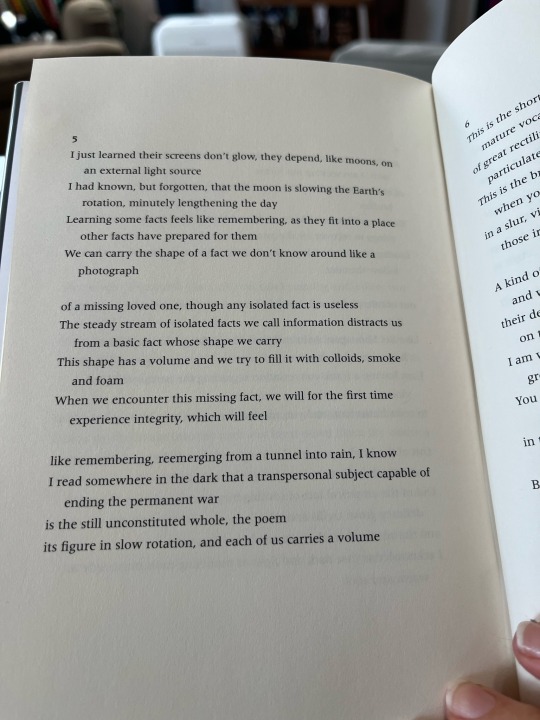

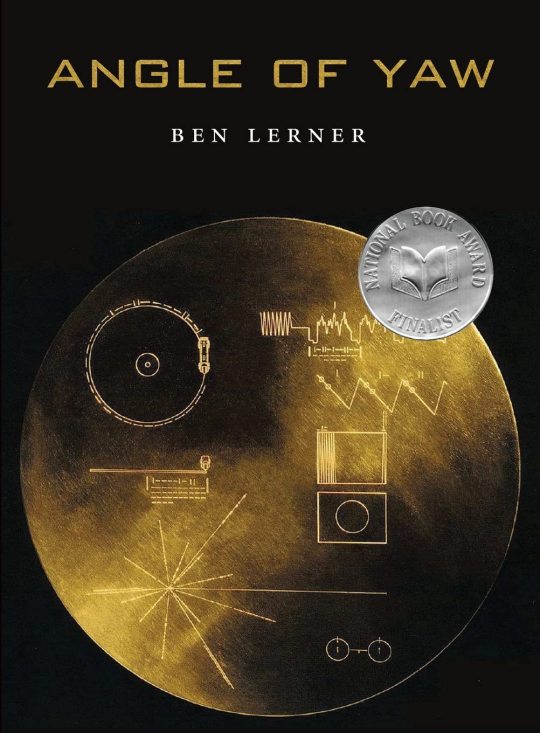

Title: Angle of Yaw | Author: Ben Lerner | Publisher: Copper Canyon Press (2006)

1 note

·

View note

Text

“Nothing is a cliche when you’re living it.”

― Ben Lerner

#Ben Lerner#reading#literature#quotes#life#life quotes#quote#world#random beautiful stuff that i read#random quotes#stumbling on random beautiful quotes

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

a responsibly equivocal stance

Max Norman's review of Diane Arbus's work in The Drift brings together some questions I've wrestled with lately, as I always wrestle with them: the questions of having a position on an artist and having complex assessments of art. Some of this is triggered by the experience of watching some friends of mine process the Oscars and the sweep made by Everything Everywhere All at Once—a therapeutic millennial movie that seems to want to palliate viewers' childhood wounds by using larger-than-life spectacle as a vehicle for overly simplified sentiment, and is being disproportionately rewarded considering its ultimate lameness (the natural product of excessive spectacle for those who don't find that charming) and conservatism. (The case for the conservatism is laid out quite well by Kieran McLean, here.) Versus the kind of artwork that tries to be several things at once, say TAR.

Which everyone online seems to be kind of stupid about? Much of this is likely shaped by Twitter's particular economy of terse opinions, quote tweeting, and dunking. Versus, say, an ecosystem of alt-weeklies or blogs issuing comparatively considered pieces (written by critics of whatever stripe, and not Twitter-posting Substackers, each hanging out their own little shingle, subjected to the demands and incentives and scale of those platforms), which people then reflected on via comments in comment sections—which is not to glamorize blogs or comment sections, just to say that what we've got now might be worse than what we had then. With TAR, it feels like a film that was designed to be ambiguous enough to evoke multiplicity in its interpretations just got such flat reads from people whose tastes I normally trust. It was a portrayal of an abuser in cancel culture being justly punished for her arrogance. Or it was a portrayal of an abuser being unjustly punished, because according to Todd Field, Lydia Tar's genius, or her age and socialization to older mores, or the perceived stupidity of her antagonists in the culture—for all that I don’t think the student she argues with, in a moment that goes viral and begins her fall, Max, is actually meant to be seen as stupid—ought to have excused her bad behavior.

To my mind, the film seemed to want to do both these things—or, as the memes would have it, a secret third thing, some hybrid of the two.

It seemed Field wanted to show a person whose character has been dessicated by the pursuit of fame experiencing the destruction of all her ties to the world that satisfied her desire — perhaps even to get back in touch with some new form of creation both degraded and genuine. Yes, Tar, at the end of the film, is in an objectively worse position than when she began. And she's not exactly saved. She may not be capable of any reckoning with herself more concrete than the atavistic, overwhelming stab of feeling that makes her vomit when she's confronted by a reminder of the women she worked to manipulate, like Krista and Olga, in the form of the girls in the spa she visits, lined up like a banquet for her delectation. She's also conducting in a meaningful way, absorbed in the act of it, in a way she has not been up to that point. And she is so because now, she has no other choice...

All this is to say: maybe Field wanted to create an object that could meaningfully be taken several ways. Maybe he meant us to go back and forth on whether Tar is right or Max is right, or to what degree; maybe he meant us to like Tar in some ways, or to find her charismatic or funny in fucked-up ways, and to disapprove of or hate her in other ways, to find her blinkered and odious and sad in her attempts to aggrandize herself. All this is so very basic to say, and I don't mean to imply I'm being radical here, but I have had this thought: maybe we're fucking up by being so insistent with how we feel about this movie and what we think it's saying About The Culture We're In. Artists shouldn’t be expected to have a single stance on something, a single intention that each work exists just to express. An artist can, should, be working through something...

Which brings me back to the Arbus piece. I appreciate Norman's calling out the position taken by curator John Szarkowski and critic Sebastian Smee that Arbus meant to humanize her subjects. I don't think Arbus's intent was to rehabilitate, to "show," as Szarkowski has it "that all of us—the most ordinary and the most exotic of us—are on closer scrutiny remarkable"; that would be banal, and perhaps as instrumentalizing of the subjects as work made to emphasize their strangeness. "Does Arbus’s photograph ["A naked man being a woman, N.Y.C., 1968"] send him up, or support him?” Norman asks, “Or is the real joke on the viewer who insists on one interpretation or another?" I don't think it's a joke played on the viewer who insists on one interpretation or the other; I do think that viewer ought to be capable of acknowledging multiple possibilities... Maybe—to state another basic point—artists, whether Diane Arbus or Todd Field, don't have answers, but questions, and they chose to do something felt as well as thought to represent them... And I think artists should be allowed to look bad, to have complicated feelings, to encounter a desire to gawk or objectify and portray that desire with a degree of honesty and interrogation so that those of us who, obeying certain limits that collective life justly(!) places, won't cop to it can confront it in some form...

I do want to be clear that interrogating the ethics of Arbus's relationship to her subjects, so many of whom were marginalized as she was not, feels useful and necessary. I also don't think we can do that with much precision if the only question we ask is Did Arbus have a right to do what she did? And while none of this is new, it does feel like Norman's piece opens a way to that more precise interrogation of the ethics of Arbus's work by pushing us past the simple binary of "the work is good" or "the work is bad"—a binary that feels particularly ubiquitous now, and undignified in the overheated discourse about art that it often fuels. Ultimately, if the Smee/Szarkowski take on Arbus is, as Norman writes, one in which "Arbus's biography, which testifies to her own 'inner mysteries,' is used to help straighten out the problem of a privileged white woman on the prowl for weirdos—a woman who once compared taking pictures to being a butterfly collector," I don't want to discount the "butterfly collector" bit. But what if what’s so often seen as a problem could once again become fact... As Norman puts it, we so often take positionality as key to understanding works of art. And how much has that uncovered for us that a responsibly equivocal stance toward an artwork—a stance that acknowledges possibilities good and bad and makes no final judgments, or doesn't rush to translate a first impression, a take, into a summary judgment—could not more effectively do?

Time, I guess, to page Sontag for those erotics of art; we might need them again...

Ironically, Sontag appears in Norman's piece as another critic determined to reduce Arbus, specifically by critique of her privilege and the perceived amorality of her voyeurism rather than by praise for some arguable desire she had to humanize her subjects. Maybe by the time Against Photography came out, Sontag too had forgotten her own edict. Or more likely, the demands of nascent image culture—and the nature of photography, versus those technologies of art that are less automatic on the part of the artist, and less readily assimilated into a media economy that goes on to inform a country's politics—had overwhelmed it.

To be clear, Sontag's take on Arbus in "America, Seen Through Photographs, Darkly" is clearly the product of intense engagement with the work and Arbus's own writings on it. But I resent the harshness of the judgments—their fixity. When Sontag writes the line

What happens to people's feelings on first exposure to today's neighborhood pornographic film or to tonight's televised atrocity is not so different form what happens when they first look at Arbus's photographs.

I think: is Arbus's work about inuring us to what is terrible? Are the subjects "necessarily ahistorical," is her view "always from the outside"? Perhaps Arbus's work is "reactive—reactive against gentility, against what is approved" to some degree; is that all it is? Sontag takes Arbus to task for not being ethical with her photographs, as a journalist might be ethical, but can't the creation of a dramatic confrontation with one's own instinct to be a voyeur be a meaningful exercise; meaningful in an ethical sense, for a viewer—particularly viewers in the same wealthy and sheltered position as Arbus—if still something for which the artist should be held to account? As Norman writes, "Looking through Arbus’s lens only makes the encounter more demanding." I suppose the point is this: There's rigor and even beauty in an unequivocal stance, but also the risk of a shrillness, an antagonism, a hostility not unlike the hostility people brought to TAR—and I'm increasingly tired of assuming a hostile, suspicious, exclusively hermaneutic relationship to art...

Right as I was writing this post, I was tipped off to the publication of an essay by Garth Greenwell in The Yale Review in which he talks about an apophatic theory of the relation between art and morality: "a theory that would allow us to explore the moral work of art without limiting or prescribing that work, as certain theologians attempt to develop ways to think about God without defining God in a manner that would violate God’s freedom." Which puts precisely the words to what I'm searching for; the relation to art I would like to return to. Marked by generosity, an understanding of an artwork as necessarily multifaceted, the taking of time in the consideration of it, an assumption of good faith. There's also a line in Ben Lerner's book The Lichtenberg Figures that comes to mind: "a great work takes up the question of its origins / and lets it drop..." Maybe I'd tweak that line now: A great work takes up the question of its ultimate meaning and lets it drop...

#movies#max norman#diane arbus#susan sontag#todd field#kieran mclean#ben lerner#garth greenwell#criticism#culture

4 notes

·

View notes