#artist is sebastiano de piombo

Text

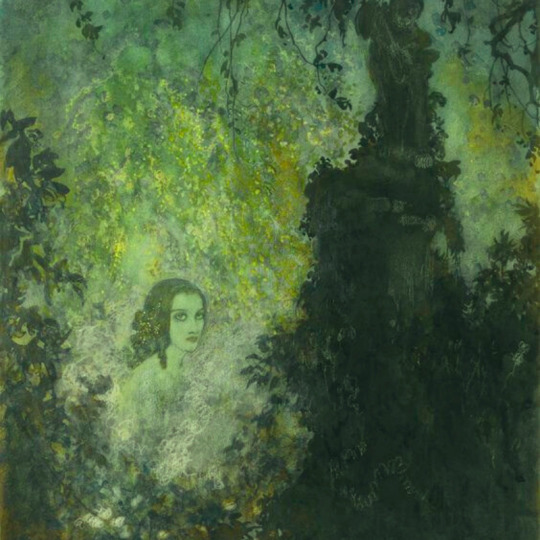

green is the fresh emblem of well founded hope. in blue the spirit can wander, but in green it can rest

#artist is sebastiano de piombo#artist is frederique brunner#artist is quinten metsys#artist is fatima ronquillo#artist is bartolomeo veneto#artist is louis jean francois lagrenee#artist is joseph dorffmeister#cant find the artist#this piece is from the workshop of rubens#artist is sophie anderson#-cant find the artist#artist is hieronymus bosch#aartist is hubery van eyck and jan van eyck#artist is m k ciurlionis amzinybe#artist is clive hicks-jenkins#artist is max bruckner#artist is hermann hendrich#artist is edward steichen#artist is john william waterhouse#artist is antonin hudecek#artist is sir frank dicksee#artist is louis welden hawkins#artist is romaine brooks#artist is anna & elena balbusso#artist is armand point#artist is francesco balsmo#artist is dean cornwell#artist is alexander rothaug#artist is josef manes#artist is edmund dulac

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

#artist is sebastiano de piombo#artist is frederique brunner#artist is quinten metsys#artist is fatima ronquillo#artist is bartolomeo veneto#artist is louis jean francois lagrenee#artist is joseph dorffmeister#cant find the artist#this piece is from the workshop of rubens#artist is sophie anderson#-cant find the artist#artist is hieronymus bosch#aartist is hubery van eyck and jan van eyck#artist is m k ciurlionis amzinybe#artist is clive hicks-jenkins#artist is max bruckner#artist is hermann hendrich#artist is edward steichen#artist is john william waterhouse#artist is antonin hudecek#artist is sir frank dicksee#artist is louis welden hawkins#artist is romaine brooks#artist is anna & elena balbusso#artist is armand point#artist is francesco balsmo#artist is dean cornwell#artist is alexander rothaug#artist is josef manes#artist is edmund dulac

0 notes

Text

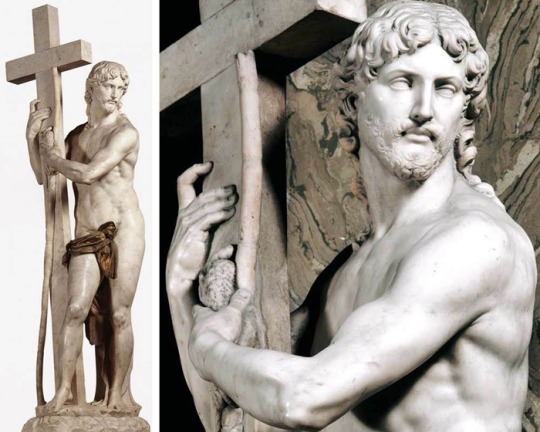

Michelangelo’s The Risen Christ: Discovering the sacred in the profane.

The true work of art is but a shadow of the divine perfection.

- Michelangelo Buonarroti

While a visit to Rome’s grand squares like Piazza Navona is at the top of everyone’s list, there is much more to the Eternal City. The Piazza della Minerva, is one of Rome’s more peculiar squares and is a must-see for lovers of Bernini’s work.

As one of the smaller squares in Rome, Piazza della Minerva holds some interesting sites. Built during Roman times, the square derives its name from the Goddess, Minerva, the Roman Goddess of wisdom and strategic warfare. During the 13th Century, the decision was made to build a Christian Church on top of what was once a square dedicated to a pagan Goddess – and so the church of Santa Maria Sopra Minerva was born, a beautiful example of Gothic architecture and Rome’s only Gothic church.

In fact this is the only Gothic church in Rome. It resembles the famous Church of Santa Maria Novella in Florence. There are three aisles inside the church. The soaring arches and the ceiling in blue are outstanding. The deep blue colours dominate the structure while the golden touches promote the intricate design. There are paintings of gold stars and saints. The stained glass windows are beautiful too.

In the centre of the Piazza is an elephant with an Egyptian obelisk on its back, one of Bernini’s last sculptures erected by Bernini for Pope Alexander VII and possibly one of the most unusual sculptures in Rome. There are several theories which aim to decipher Bernini’s inspiration for the sculpture, some of which point to Bernini’s study of the first elephant to visit Rome, while others point to a more satirical combination of a pagan stone with a baroque elephant in front of a Christian church.

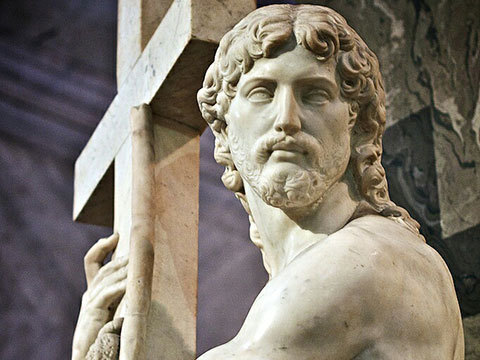

Tourists flock to see the elephant but more often than not they miss out visiting an almost forgotten marble masterpeiece by Michelangelo himself inside the church. This controversial statue has resided in the Santa Maria sopra Minerva Church in Rome for almost five hundred years. Indeed The Risen Christ by Michelangelo is one of the artist's least admired works. While modern observers frequently have found fault with the statue, it satisfied its patrons enormously and was widely admired by contemporaries. Not least, the sculpture has suffered from the manner in which it is presently displayed and from biased photographic reproduction that emphasises unfavorable and inappropriate views of Christ.

Around 2017 I was fortunate on a visit back to London to see once again Michelangelo’s marble masterpiece, The Risen Christ, which was being displayed in all its naked glory at an exhibition at the National Gallery.

This was another version of this great sculpture that no one has got round to covering up. It has just come to Britain. Michelangelo’s first version has been lent to the National Gallery, in London, for its exhibition Michelangelo and Sebastiano del Piombo in 2017. It came from San Vincenzo Monastery in Bassano Romano, where it languished in obscurity until it was recognised as Michelangelo’s lost work in 1997.

I found it profoundly moving then as I had seen the other partially clothed one on several visits to the church in Rome. It has always perplexed me why this beautiful work of art has been either shunned to the side with hidden shame or embarrassment when it holds up such profound sacred truth for both art lover or a Christian believer (or both as I am).

Michelangelo made a contract in June 1514 AD that he would make a sculpture of a standing, naked figure of Christ holding a cross, and that the sculpture would be completed within four years of the contract. Michelangelo had a problem because the marble he started carving was defective and had a black streak in the area of the face. His patrons, Bernardo Cencio, Mario Scapucci, and Metello Vari de' Pocari, were wondering what happened when they hadn't heard for a while from Michelangelo. Michelangelo had stopped work on The Risen Christ due to the blemish in the marble, and he was working on another project, the San Lorenzo facade. Michelangelo felt grief because this project of The Risen Christ was delayed. Michelangelo ordered a new marble block from Pisa which was to arrive on the first boat. When The Risen Christ was finally finished in March 1521 AD Michelangelo was only 46 years old.

It was transported to Rome and this 80.75 inches tall marble statue was installed at the left pillar of the choir in the church Santa Maria sopra Minerva, by Pietro Urbano, Michelangelo's assistant (Hughes, 1999). It turns out that Urbano did a finish to the feet, hands, nostrils, and beard of Christ, that many friends of Michelangelo described as disastrous). Furthermore, later-on in history, nail-holes were pierced in Christ's hands, and Christ's genitalia were hidden behind a bronze loincloth.

Because people have changed this sculpture over time; many are disappointed with this work of art because it is presently different than the original work that Michelangelo made. The Risen Christ had no title during Michelangelo's lifetime. This sculpture was given the name it has now, because Christ is standing like the traditional resurrected saviour, as seen in other similar works of art.

It was in discussion with an art historian friend of mine currently teaching I was surprised through her to discover the sculpture’s uncomfortably controversial history. There is no doubt Michelangelo’s marvellous marble creation has raised robust debates about where beauty as an aesthetic sits between the sacred and the profane. And nothing exemplifies that better than the phallus on Michelangelo’s The Risen Christ.

For the majority of its time there, however, the phallus has been carefully draped with a bronze loincloth - incongruous at best, and prudish at worst, but either way a less than subtle display of the historic Church’s discomfort with the full physicality of Christ.

Indeed, it is worth noting that this attitude prevails, at least in some sense, into the twentieth-century: the version of the statue in Rome remains covered to this day, and much of the critical attention the sculpture has received after Michelangelo’s death has been grating. Romain Rolland, an early biographer, described it as ‘the coldest and dullest thing he ever did’, whilst Linda Murray bluntly dubbed the work ‘Michelangelo’s chief and perhaps only total failure’.

But Michelangelo himself saw no such mistake. The censored statue seen in Santa Maria sopra Minerva is what we might call his second draft.

It’s interesting to note that when artist was originally commissioned to sculpt a risen Christ in 1514, he had all but completed it before realising that a vein of black marble ran across Jesus’ face, marring the image of classical perfection which he so wished to emulate. It had nothing to do with the phallus. Furious, Michelangelo abandoned this Christ - the one I saw at the National Gallery - and began again. Even given a fresh chance, he chose to retain Christ’s complete nudity.

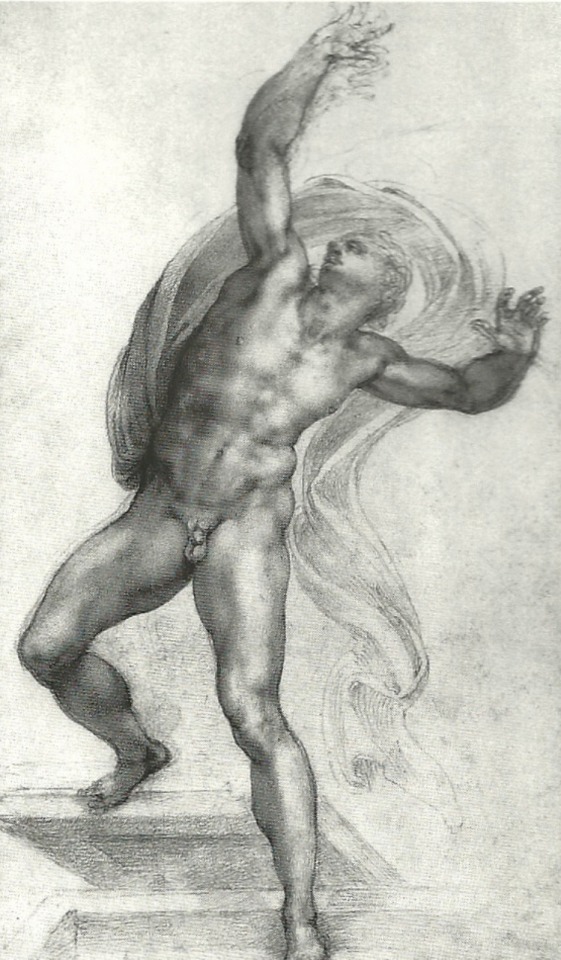

Why was this of such importance to Michelangelo? Why did he so strongly wish to craft the literal manhood of Christ, as never depicted before? Part of the answer may lie in his historical context: the Renaissance in Italy was driven in the part by the remains of Roman antiquity discovered there; study of the classics became commonplace, and scholars tended to consider the Graeco-Roman world as a cultural ideal, with ancient art in particular being emblematic of a lost Golden Age. Famously, classical sculpture was almost always nude.

In his interview with The Telegraph in 2015, Ian Jenkins, curator of the British Museum exhibition “Defining Beauty: The Body in Ancient Greek Art”, attempted to explain this tradition. ‘The Greeks … didn’t walk down the High Street in Athens naked … But to the Greeks [nudity] was the mark of a hero. It was not about representing the literal world, but a world which was mythologised.’

We see evidence for this trend in Greek literature as well as sculpture: Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey, considered by some to be the earliest known works of Western literature, were likely written between the 8th and 7th centuries BC, but their setting is in Mycenaean Greece in the 12th century. The Greeks believed that this earlier Bronze Age was an epoch of heroism, wherein gods walked the earth alongside mortals and the human experience was generally more sublime. In setting the texts at this earlier stage in Greece’s history, Homer echoes the belief held within his contemporary society that mankind had been better before (what we might now call nostalgia, or, more colloquially, “The Good Old Days syndrome”). There is a real feeling of delight present in the distance Homer creates between his actual, flawed society, and the idealised past.

Indeed, it calls to mind a line I once read in an introduction to L.P. Hartley’s The Go-Between, by Douglas Brookes-Davies: ‘Memory idealises the past’. Though modernist texts such as The Go-Between problematise this, in antiquity it was not only commonplace but celebrated to look back to a more perfect existence and relive it through art. The very fact that Michelangelo abandoned his sculpture after years of work on account of a barely noticeable flaw in the marble is evidence that he, too, was striving towards the classical ideal of perfection. ‘Unfortunately,’ Hazel Stanier has commented, ‘this has resulted in unintentionally making Christ appear like a pagan god.’

This opens up another question – why does such a rift exist between the way ancient cultures envisaged their divinity and our own conceptions of a Christian God? Why are we not allowed to anthropomorphise the deus of the Bible in the same way that the Roman gods were?

Christ, of course, makes this somewhat confusing, given that he is described in the Bible as ‘the Word made flesh’, a physical and very human incarnation of the spiritual being that we call God. Theology tells us that he is fully human and fully divine, and yet the Church have excluded him from many aspects of life that a majority of us see as typifying a human being. Christ has no apparent sexual desires or romantic relationships, and though not exempt from suffering, he does not play any part in sin (which, as the saying goes, is ‘only human’). I think that the enormous controversy caused by films such as The Last Temptation of Christ (1988), which explore the possibility of Jesus having a sex life, is reflective of the possibility that - though in theory the Christian messiah is fully human - we feel significant discomfort at the notion that he may have explored particular aspects of the human experience.

Purists and the prude and liberals rush to opposite sides of the debate. If purists run one way to completely deny Christ had any sexual desires or even inclinations as all humans are want to do, liberals commit the sin of rushing to the other extreme end and presuppose that Jesus did act on sexual impulses simply because it was inevitable of his human nature.

I think the truth lies somewhere between but what that truth might actually be is simply speculation on my part. It doesn’t detract for me the life and saving mission of redemption that Jesus was on - to suffer and die for our sins as well as the Godhead reconciling itself to sacrificing the Son for Man’s sins and just punishment.

Of course, it is well-known that the classical gods had no qualms about sexual activity. It is difficult to make retrospective judgements about citizens’ opinions on this but, as it was the norm, we might assume that they felt it was rather a non-issue. I can empathise with some critics who reason that the Christian God is not entitled to sexual expression is because of the traditional Christian idea that sex is inherently sinful – that original sin is passed on seminally and so by having sex we continue to spread darkness and provoke further transgression. It is from this early idea that theological issues such as the need for Mary to have been immaculately conceived (she was not created out of a sexual union, much like her son) have stemmed. But here - the immaculate conception - the critics are profoundly wrong in their theological understanding of why God had to enter the world as Immanuel in this miraculous way.

Some Christian critics - and I would agree with them - assert that the vision of a naked Christ might make a powerful theological point in a world where sex still carries these connotations. They rightly point out that clothing - and I might extend this to mean the covering-up of the sexual parts of our body - was only adopted by humankind after the Fall, the nudity of Christ is making a statement about his unfallen nature as the second Adam. In other words, Christ has no shame, because he is sinless and has no need for shame. Perhaps what Michelangelo intended was actually to disentangle nudity from its sexual, sinful associations, instead presenting us with a pre-lapsarian image of purity taking the form of the classical Bronze Age hero.

There is another, less theological explanation for the sculptor’s obvious use of the classical form. It reminds us of a time when gods walked the earth alongside us, when they were fully human – us, only immortal. Maybe he wanted to emphasise that fully human aspect of Christ’s being. Questionable as much of their behaviour was, the classical gods were certainly easy to identify with. For Michelangelo, this may have been his own way of embodying John 1:14 in marble: ‘The Word became flesh and made his dwelling among us’.

It is here critics may have gotten hold of the wrong end of the stick with The Risen Christ when they point out the odd proportions of the figure: that it has a weighty torso, or the broad hips atop a pair of tapered and rather spindly legs, or even a side or rear view of the figure that show Christ’s buttocks.

For a start, this ungainly rear view was not supposed to be seen. The statue was meant to go in a wall niche, so that the back of the statue was hidden. Michelangelo of course knew this, and shaped the statue so that it would appear well proportioned from the front. If we view the sculpture from the front left, perhaps its best side, then Christ is no longer a thickset figure. Rather, his body merges with the cross in a graceful and harmonious composition.

The turn of Christ’s body and his averted face suggest something like the shunning of physical contact that is central to another post-Resurrection subject, the Noli me tangere (“Touch Me Not”). The turned head is a poignant way of making Christ seem inaccessible even as the reality of his living flesh is manifest.

We are encouraged to look at not Christ’s face, but the instruments of his Passion. Our attention is directed to the cross by the effortless cross-body gesture of the left arm and the entwining movement of the right leg. With his powerful but graceful hands, Christ cradles the cross, and the separated index fingers direct us first to the cross and then heavenward. Christ presents us with the symbols of his Passion – the tangible recollection of his earthly suffering.

Behind Christ and barely visible between his legs we see the cloth in which Christ was wrapped when he was in the tomb. He has just shed the earthly shroud; it is in the midst of slipping to earth. In this suspended instant, Christ is completely and properly nude.

We must imagine how the figure must have appeared in its original setting, within the darkened confines of an elevated niche. Christ steps forth, as though from the tomb and the shadow of death. Foremost are the symbols of the Passion, which Christ will leave behind when he ascends to heaven.

Why was Michelangelo compelled to portray Christ completely naked in a way that was bound to trouble some Christians? It was not out of a desire to blaspheme. On the contrary, this genius – poet, architect and painter as well as the greatest sculptor who has ever lived – was not only a faithful Christian but someone who thought deeply about theology. You can bet he had good religious reasons to depict Christ in full nudity.

But it would be complacent to think there was no tension in showing Christ nude. The fact that The Risen Christ in Santa Maria still has its covering proves how real those tensions are. The fundamental reason Michelangelo could get away with it was that he was Michelangelo. By the time he created this statue, he had the Sistine Chapel ceiling (with all its male nudes) under his belt and was the most famous artist in the world.

For centuries, the faithful have kissed the advanced foot of Christ, for like Mary Magdalene and doubting Thomas, they wish for some sort of physical contact with the Risen Christ. To carve a life-size marble statue of a naked Christ certainly was audacious, but it is also theologically appropriate. Michelangelo’s contemporaries recognised, more easily than modern viewers, that the Risen Christ was a moving and profoundly beautiful sculpture that was true to the sacred story.

#the risen christ#michelangelo#marble#church#christian#beauty#aesthetics#statue#religious#renaissance#history#rome#bernini#art#arts#culture#society#religion#sculpture

201 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Christ Carrying the Cross, Sebastiano del Piombo, 1515, Art Institute of Chicago: European Painting and Sculpture

This painting by represents one of the most popular compositions invented by one of the most distinguished painters working in Rome during the High Renaissance. In the 1510s, following an early period in Venice, Sebastiano del Piombo traveled to Rome, where he was drawn into the lively atmosphere of competition between the two great luminaries of the period, Michelangelo Buonarroti and Raphael. Michelangelo took Sebastiano under his wing, teaching him his monumental style and providing drawings for some of Sebastiano’s major commissions. Following Raphael’s death in 1520, the painter and historian Giorgio Vasari stated that“first place in the art of painting was unanimously granted by all, thanks to the favor of Michelangelo, to Sebastiano.” Christ Carrying the Cross draws upon recent developments of an enormously popular iconography by artists including Giovanni Bellini, Giorgione, and Andrea Mantegna, among others. Here, Simon of Cyrene assists Jesus, emphasizing the heavy weight of the cross on his shoulders. A Roman soldier stands behind, his jeering face just visible in the darkness. In the background, the tightly packed composition opens up onto a crowd assembling at the foot of the hill of Golgotha, with two crosses barely visible. The luminous landscape is a hallmark of the artist’s Venetian training. The painting’s dramatic visual impact is a result of the powerful diagonals of the cross; the dynamic, almost sculptural quality of Christ’s clothing; and the pathos of his expression. The popularity of Sebastiano’s composition is reflected in the number of surviving variants that he created over the course of his career. The Art Institute’s version is an autograph replica of a painting—now in the Museo del Prado, Madrid—made for Jerónimo Vich y Valterra, the Spanish ambassador to Rome. Other versions survive in the State Hermitage Museum, Saint Petersburg; the Monasterio de las Descalzas Reales, Madrid; and the Szépmüvészeti Múzeum, Budapest. Lacy Armour, Ada Turnbull Hertle, Mary Swissler Oldberg Acquisition, Charles H. and Mary F. S. Worcester Collection funds; Wirt D. Walker Trust; Alyce and Edwin DeCosta and the Walter E. Heller Foundation Fund; Estate of Walter Aitken; Frederick W. Renshaw Acquisition, Marian and Samuel Klasstorner funds; Edward E. Ayer Fund in Memory of Charles L. Hutchinson; Lara T. Magnuson Acquisition, Director's funds; Samuel A. Marx Purchase Fund for Major Acquisitions; Edward Johnson, Maurice D. Galleher Endowment, Simeon B. Williams, Capital Campaign General Acquisitions, Wentworth Greene Field Memorial, Samuel P. Avery, Morris L. Parker, Irving and June Seaman Endowment, and Betty Bell Spooner funds

Size: 118 × 92 cm (46 7/16 × 36 1/4 in.)

Medium: Oil on panel

https://www.artic.edu/artworks/234781/

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

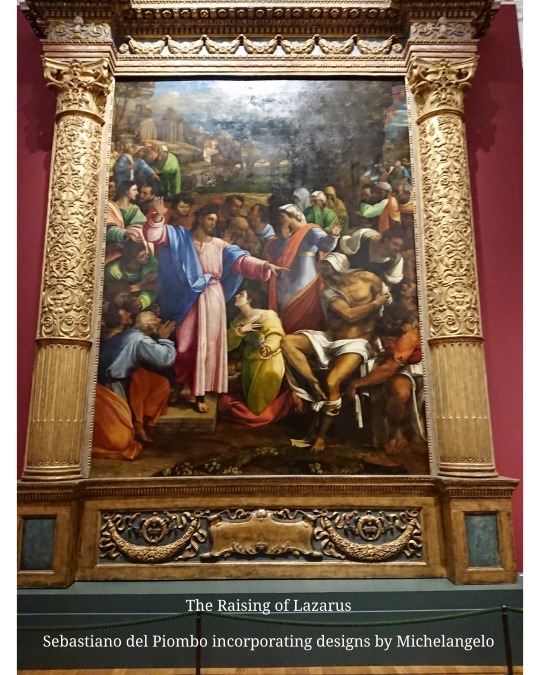

The Raising of Lazarus

.

Sebastiano del Piombo incorporating designs by Michelangelo

.

.

National Gallery description;

.

At the request of Martha & Mary, Jesus visited the grave of their brother Lazarus & raised him from the dead (John 11:1–44). Sebastiano shows Christ standing with one hand raised to invoke the power of God & the other pointing to Lazarus, who is seated on the edge of his stone tomb.

.

Christ speaks the life-giving words, ‘Lazarus come forth’. A kneeling man helps Lazarus remove the shroud and bindings in which he had been buried. Mary kneels at Christ’s feet in awe while Martha raises her hands & turns her head away, unable to look. Saint Peter at bottom left falls to his knees while other disciples turn to one another in amazement.

.

The painting was commissioned for Narbonne Cathedral in southern France by Cardinal Giulio de' Medici, who had also commissioned Raphael’s Transfiguration for the same cathedral. Michelangelo provided drawings for some of the main figures in this complex composition as he was keen to help Sebastiano outperform Raphael, their artistic rival.

For more information about the National Gallery London, click the link below 👇

National Gallery London

.

#historic#historical#history#historians#art work#arthistory#artwork#artgallery#art galleries#Explore London#Visit London#trafalgarsquare#National gallery#National gallery London

0 notes

Text

This summer throughout January, I’m catching up with some of my unpublished stories from earlier travels throughout Europe in 2017. Some posts will be light-hearted, centered around food and accommodation, ‘the best of’ reports, while others are research based essays. It will be rewarding to polish them up and give them a final airing. Of course there will be a few cooking posts along the way too.

Buona Lettura

I’ve been thinking a lot about Agostino Chigi lately, and wondering why there’s not a great deal written about him. Given that he commissioned one of the most elegant and beautiful buildings of the Renaissance, Villa Farnesina in Trastevere, Rome, and was a generous patron of the arts, I fins this quite unusual.

Agostino Chigi, (pronounced kee-gee) was a 15th to 16th century banker who was born Siena then moved to Rome to assist his father, Mariano Chigi in 1487. He became the wealthiest man in Rome, especially after becoming banker to the Borgia family, in particular Pope Alexander V, followed by Pope Julius 11. If there’s one thing that helps a banker stay at the top, it’s having business dealings in Rome and becoming the Pope’s treasurer. The Florentine Medici, Giovanni di Bicci and Cosimo de’ Medici, also milked their Roman and Papal connections in the preceding years. Chigi’s financial interests expanded to obtaining lucrative control of important minerals, including the salt monopoly of the Papal States and Naples and the alum monopoly in Southern Italy. Alum was the essential mordant in the textile industry. With financial and mining interests, like a modern-day crony capitalist and entrepreneur, Chigi was ready to splurge.

The connection between the arts and banking makes an interesting Renaissance study in itself ¹. Banking families were keen patrons of the arts, not only in a bid to show off their taste and refinement, but also to cast off the slur of usury. Usury, making profit from charging interest on a loan, was a crime in 15th century Europe: a usurer was heading straight to hell, according to the main religious thinking of the day, unless he made a few corrections to that practice, through intricate bills of credit requiring lengthy international currency exchange deals. Banker patrons, worried about their afterlife, could buy a place in heaven by financing religious works -perhaps a marble tomb for a Pope, or some fine brass relief doors for a baptistry, or a few walls of religious themed freschi demonstrating their piety and devotion by appearing as genuflecting bystanders in a painting or two.

Chigi, like other bankers before him, was keen to spend time with the literati and patronised the main artistic figures of the early 16th century, including Perugino, Sebastiano del Piombo, Giovanni da Udine, Giulio Romano, Il Sodoma and Raffaele. These artists, and the architect Baldassare Peruzzi, all had a hand in making Villa Farnesina so attractive and harmonious. But the main feature you’ll notice in the painted works is its secularity: no religious themes appear in the decoration at all. Thus somewhere between the mid 15th century and 1608,when this building was commissioned and begun, the subject of the visual arts had shifted. Here, the freschi depict classical and historic themes: there’s not a Madonna or baby Jesus in sight except for those cheeky putti holding up garlands. I doubt that Agostino Chigi was overly concerned with the sin of usury. Times had changed.

Suggestive coupling of fruits. New world fruits appear in the garlands of Udine.

The ground floor room, the stunning Loggia di Psiche e Amore, was designed by Raffaele, though is mostly executed by one of his followers Giulio Romano, and seems heavier in style. It’s not the best secular work of Raffaele: his most graceful works are held in the quiet gallery of Gemäldegalerie, in Berlin, Germany ( more on this gallery later). The decorative garlands and festoons are by Giovanni da Udine, and although hard to get close to, draped as they are on high ceilings and around tall window sills and pillars, they steal the show.

Sensuous and erotic, the total effect of the Loggia is complete in its aim and purpose. This is a pleasure palace, a space decorated with pagan themes of love and seduction from classical mythology, designed to amuse Chigi’s guests. The modern addition of a walled glass fronting the garden allows more light to shine on the rich colours and detail. It is delightful.

Upstairs in a smallish room, the wall panels by Il Sodoma, ( catchy nick name for the artist, Giovanni Antonio Bazzi , no two guesses why), depict scenes from the marriage of Roxana and Alexander. The total effect in such a small space visually overwhelming.

At the end of the 16th century, Villa Farnesina was bought by Cardinal Alessandro Farnese ( of course a Cardinal needs an erotically decorated villa) and its name “Farnesina” was given to distinguish it from the Cardinal’s much larger Palazzo Farnese on the other side of the Tevere. Today the Villa is the centre for the Accademia Nazionale dei Lincei, the Italian Science Academy and the rooms are open to visitors. Palazzo Farnese, across the river, is occupied by the French Consulate and is not open to the public.

These small decorative motifs on window shutters and in cornices add to the overall aesthetic of the villa.

Some useful accompanying notes.

Giorgio Vasari, (1511-1574) author of Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors and Architects, often simply called Vasari’s ‘Lives’, was the first art historian and the first to use the term rinascita ( Renaissance) in print, though an awareness of the ongoing “rebirth” in the arts had been in the air since the writings of the Florentine Humanist, Alberti, almost a century earlier. He was responsible for the use of the term Gothic Art, and used the word Goth which he associated with the “barbaric” German style. His work has a consistent bias in favour of Florentines and tends to attribute to them all the developments in Renaissance art. Vasari has influenced many art historians since then, and to this day, many travellers to Italy are blinded by Vasari’s Florentine list and bias, at the expense of other important works in Milano and Rome. Vasari, however, does recognise the works in the Farnesina.

¹ The nexus between banking and art patronage is fully explored by Tim Parks in Medici Money. Banking, Metaphysics and Art in Fifteenth- Century Florence,one of my favourite books. I am now re- reading this excellent history: it has an accessible style and makes for enjoyable summer reading, for those who enjoy reading about the Renaissance.

² Various papers on the festoons and garlands in the Villa Farnesina in Colours of Prosperity Fruits from the Old and New world, produced by the Accademia Nazionale dei Lincei and purchased at Villa Farnesina in Rome.

Agostino Chigi, 1506. Oil on canvas, anonymous.

Villa Farnesina is in the quiet part of Trastevere, well away from the tourist hordes in that precinct, and is very quiet in the month of November. Sadly the garden wasn’t open to casual visitors.

http://www.villafarnesina.it/

Via della Lungara, 230, 00165 Roma RM, Italy

Villa Farnesina, Rome. Who was Agostino Chigi? This summer throughout January, I'm catching up with some of my unpublished stories from earlier travels throughout Europe in 2017.

#Agostino Chigi#art#Classicism#Cosimo de&039; Medici#florence#freschi#Italy#patronage#Raffaele#Renaissance bankers#Renaissance patronage#renaissance popes#Roma#Rome#secular art#Tim Parks#Trastevere#Udine#Vasari#Villa Farnesina

0 notes

Text

Beyond Disegno: Professional Identity and Material Experimentation in mid 16th-century Italian Portraiture

Venue: Theatre C (124), Old Arts

Presenters: Dr Elena Calvillo

By 1531, the Venetian artist Sebastiano del Piombo had resettled in Rome after the Sack, received a lucrative sinecure as the keeper of the papal seals and won acclaim for his method of painting in oils on stone supports. Two decades later, Agnolo Bronzino produced a series of portraits on tin supports while working for Cosimo I de' Medici. This lecture examines the ways in which their innovative use of materials in portraiture contributed to both the painters' and patrons' identities, and how it made claims of originality and invention that might otherwise be denied to artists who excelled in the portrait genre.

Dr Elena Calvillo is Associate Professor of Art History, University of Richmond. Her research and writing focus on artistic service and imitative strategies in 16th-century Italy, Spain and Portugal.

Image: Sebastiano del Piombo. Portrait of Pope Clement VII. c. 1531. Oil on slate. Naples, Museo di Capodimonte (Photo Scala)

from Australia & Canada https://events.unimelb.edu.au/events/9214-beyond-disegno-professional-identity-and-material-experimentation-in-mid-16th-century

0 notes

Text

Hyperallergic: The Getty Buys Trove Valued at Over $100M, Includes a Michelangelo and a Watteau

Girolamo Mazzola, called Parmigianino, “Head of a Young Man” (ca.1539-40) (all images courtesy the J. Paul Getty Trust)

The Getty Museum has announced a major acquisition of master works that will greatly enrich its Department of Drawings. Entering its collection are 16 drawings by Michelangelo, Parmigianino, Rubens, Goya, Degas, and other great artists — all male, notably — from Western art history. Purchased as a group from an unidentified British private collection, the acquisition is a landmark move for the institution, which has built up its trove of European drawings over two and a half decades. The institution’s director Timothy Potts described it as “a transformative event in the history of the Getty Museum. Many art specialists are estimating the total amount paid for the works certainly exceed $100 million, but the museum has not commented on the final price.

Michelangelo Buonarroti, “Study of a Mourning Woman” (ca. 1500-05)

“It is very unlikely that there will ever be another opportunity to elevate so significantly our representation of these artists, and, more importantly, the status of the Getty collection overall,” he said in a press release.

Among the acquired masterpieces is Parmigianino’s incredibly detailed ink drawing a young man’s head, portrayed frontally, and a drawing by Michelangelo of a woman in mourning who hides her face within the folds of her draped garment. The latter was discovered in 2000 at Castle Howard in England and was valued then at £8 million (~$10.4M USD).

While the museum did not reveal the price tag of this monumental buy, Potts told the New York Times that it was “the Getty’s biggest in terms of financial value.”

The drawings mostly date to the 16th century and the majority are by Italian artists. Also represented is Rubens, whose early 17th-century oil-on-paper work of an African man served as the study of one of the central figures in his famed “The Adoration of the Magi.” And from Goya arrives a particularly foreboding brush-and-ink drawing: “The Eagle Hunter” (1812–20) portrays a hunter hanging from a cliff to reach for eggs in a nest, his face hidden by a metal cooking pot that serves as a helmet — particularly necessary in this scene, as the parent eagle appears behind him, with sharp claws at the ready.

Aside from the drawings, the Getty also acquired one painting of a fête galante by Antoine Watteau. “La Surprise” depicts a couple in an amorous embrace as a musician watches them, and a dog watches him. Once lost for almost two centuries and believed to be destroyed, the work was found in 2007 in a British private collection. According to the LA Times, the Watteau was “on offer for more than $22 million in 2011.”

It will be some time before the public will be able to see these treasures in person. The majority of the artworks are currently in storage at the Getty, but export licenses for three are still pending. The museum is currently planning to showcase the entire group together in a special exhibition at a date to be decided.

Lorenzo di Credi, “Head of a Young Boy Crowned with Laurel” (ca. 1500-05)

Fra Bartolommeo, “Studies of the Heads of Two Dominican Friars” (ca. 1511)

Jean Antoine Watteau, “La Surprise” (ca. 1718) (all images courtesy the J. Paul Getty Trust)

Francisco de Goya, “The Eagle Hunter” (ca. 1812-20)

John Martin, “The Destruction of Pharaoh’s Host” (1836)

Sebastiano del Piombo, “Study for the Figure of Christ Carrying the Cross” (ca.1513-14)

Federico Barocci, “Study for the Head of St. Joseph” (ca. 1586)

Edgar Degas, “After the Bath” (ca.1886)

Domenico Beccafumi, “Head of a Youth” (ca.1530)

Peter Paul Rubens, “Head of an African Man Wearing a Turban” (ca. 1609-13)

The post The Getty Buys Trove Valued at Over $100M, Includes a Michelangelo and a Watteau appeared first on Hyperallergic.

from Hyperallergic http://ift.tt/2v0X2Dr

via IFTTT

0 notes

Video

youtube

Places to see in ( Burgos - Spain ) Catedral de Burgos The Cathedral of Saint Mary of Burgos is a Catholic church dedicated to the Virgin Mary located in the Spanish city of Burgos. Its official name is Santa Iglesia Catedral Basílica Metropolitana de Santa María de Burgos. Catedral de Burgos construction began in 1221, following French Gothic patterns . Had major changes in the 15th and 16th centuries: the spiers of the main facade, the Chapel of the Constable and dome of the cruise, elements of the advanced Gothic which give the temple its unmistakable profile. The last works of importance (the Sacristy or the Chapel of Saint Thecla) already belong to the 18th century, century in which were also modified the Gothic portals of the main facade. The style of Catedral de Burgos is the Gothic, although it has, in its interior, several decorative Renaissance and Baroque elements. The construction and renovations were made with limestone extracted from the quarrys of the nearby town of Hontoria de la Cantera. In Catedral de Burgos are preserved works of extraordinary artists, such as architects and sculptors of the Colonia family (Juan, Simón and Francisco), the architect Juan de Vallejo, sculptors Gil de Siloé, Felipe Bigarny, Rodrigo de la Haya, Martín de la Haya, Juan de Ancheta and Juan Pascual de Mena, the sculptor and architect Diego de Siloé, the fencer Cristóbal de Andino, the glazier Arnao de Flandes or painters Alonso de Sedano, Mateo Cerezo, Sebastiano del Piombo or Juan Ricci, among others. The design of the main facade is related to the purest French Gothic style of the great cathedrals of Paris and Reims, while the interior elevation as a reference to Bourges Cathedral. It consists of three bodies topped by two lateral square towers. The squelettes of Germanic influence were added in the 15th century and are the work of Juan de Colonia. In the outside are outstanding also covers del Sarmental and la Coronería, 13th century Gothics, and the cover de la Pellejería of 16th century Plateresques-Renaissance influences. Catedral de Burgos was declared a World Heritage Site by UNESCO on October 31, 1984. Catedral de Burgos is the only Spanish cathedral that has this distinction independently, without being joined to the historic center of a city (as in Salamanca, Santiago de Compostela, Ávila, Córdoba, Toledo, Alcalá de Henares or Cuenca) or in union with other buildings, as in Seville. Catedral de Burgos is similar in design to Brussels Cathedral. There are numerous architectural, sculptural and pictorial treasures inside. Highlights include: The Gothic-Plateresque dome, raised by Juan de Colonia in the 15th century. The Chapel del Constable, of Isabelline Gothic style, which worked the Colonia family, Diego de Siloé and Felipe Bigarny. The Spanish-Flemish Gothic altarpiece by Gil de Siloé for the Chapel of Saint Anne. The stalls of the choir Renaissance Plateresque work by Bigarny. The late Gothic reliefs of the girola by Bigarny. Numerous Gothic and Renaissance tombs. The Renaissance Golden staircase by Diego de Siloé. The Santísimo Cristo de Burgos, image of great devotional tradition. The tomb of El Cid and his wife Doña Jimena, his letter of Down payment and his chest. The Papamoscas, articulated statue that opens his mouth to give the chiming of the hours. ( Burgos - Spain ) is well know as a tourist destination because of the variety of places you can enjoy while you are visiting the city of Burgos . Through a series of videos we will try to show you recommended places to visit in Burgos - Spain Join us for more : https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCLP2J3yzHO9rZDyzie5Y5Og http://ift.tt/2drFR54 http://ift.tt/2cZihu3 http://ift.tt/2drG48C https://twitter.com/Placestoseein1 http://ift.tt/2cZizAU http://ift.tt/2duaBPE

0 notes

Photo

Christ Carrying the Cross, Sebastiano del Piombo, 1515, Art Institute of Chicago: European Painting and Sculpture

This painting by represents one of the most popular compositions invented by one of the most distinguished painters working in Rome during the High Renaissance. In the 1510s, following an early period in Venice, Sebastiano del Piombo traveled to Rome, where he was drawn into the lively atmosphere of competition between the two great luminaries of the period, Michelangelo Buonarroti and Raphael. Michelangelo took Sebastiano under his wing, teaching him his monumental style and providing drawings for some of Sebastiano’s major commissions. Following Raphael’s death in 1520, the painter and historian Giorgio Vasari stated that“first place in the art of painting was unanimously granted by all, thanks to the favor of Michelangelo, to Sebastiano.” Christ Carrying the Cross draws upon recent developments of an enormously popular iconography by artists including Giovanni Bellini, Giorgione, and Andrea Mantegna, among others. Here, Simon of Cyrene assists Jesus, emphasizing the heavy weight of the cross on his shoulders. A Roman soldier stands behind, his jeering face just visible in the darkness. In the background, the tightly packed composition opens up onto a crowd assembling at the foot of the hill of Golgotha, with two crosses barely visible. The luminous landscape is a hallmark of the artist’s Venetian training. The painting’s dramatic visual impact is a result of the powerful diagonals of the cross; the dynamic, almost sculptural quality of Christ’s clothing; and the pathos of his expression. The popularity of Sebastiano’s composition is reflected in the number of surviving variants that he created over the course of his career. The Art Institute’s version is an autograph replica of a painting—now in the Museo del Prado, Madrid—made for Jerónimo Vich y Valterra, the Spanish ambassador to Rome. Other versions survive in the State Hermitage Museum, Saint Petersburg; the Monasterio de las Descalzas Reales, Madrid; and the Szépmüvészeti Múzeum, Budapest. Lacy Armour, Ada Turnbull Hertle, Mary Swissler Oldberg Acquisition, Charles H. and Mary F. S. Worcester Collection funds; Wirt D. Walker Trust; Alyce and Edwin DeCosta and the Walter E. Heller Foundation Fund; Estate of Walter Aitken; Frederick W. Renshaw Acquisition, Marian and Samuel Klasstorner funds; Edward E. Ayer Fund in Memory of Charles L. Hutchinson; Lara T. Magnuson Acquisition, Director's funds; Samuel A. Marx Purchase Fund for Major Acquisitions; Edward Johnson, Maurice D. Galleher Endowment, Simeon B. Williams, Capital Campaign General Acquisitions, Wentworth Greene Field Memorial, Samuel P. Avery, Morris L. Parker, Irving and June Seaman Endowment, and Betty Bell Spooner funds

Size: 118 × 92 cm (46 7/16 × 36 1/4 in.)

Medium: Oil on panel

https://www.artic.edu/artworks/234781/

8 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Christ Carrying the Cross, Sebastiano del Piombo, 1515, Art Institute of Chicago: European Painting and Sculpture

This painting by represents one of the most popular compositions invented by one of the most distinguished painters working in Rome during the High Renaissance. In the 1510s, following an early period in Venice, Sebastiano del Piombo traveled to Rome, where he was drawn into the lively atmosphere of competition between the two great luminaries of the period, Michelangelo Buonarroti and Raphael. Michelangelo took Sebastiano under his wing, teaching him his monumental style and providing drawings for some of Sebastiano’s major commissions. Following Raphael’s death in 1520, the painter and historian Giorgio Vasari stated that“first place in the art of painting was unanimously granted by all, thanks to the favor of Michelangelo, to Sebastiano.” Christ Carrying the Cross draws upon recent developments of an enormously popular iconography by artists including Giovanni Bellini, Giorgione, and Andrea Mantegna, among others. Here, Simon of Cyrene assists Jesus, emphasizing the heavy weight of the cross on his shoulders. A Roman soldier stands behind, his jeering face just visible in the darkness. In the background, the tightly packed composition opens up onto a crowd assembling at the foot of the hill of Golgotha, with two crosses barely visible. The luminous landscape is a hallmark of the artist’s Venetian training. The painting’s dramatic visual impact is a result of the powerful diagonals of the cross; the dynamic, almost sculptural quality of Christ’s clothing; and the pathos of his expression. The popularity of Sebastiano’s composition is reflected in the number of surviving variants that he created over the course of his career. The Art Institute’s version is an autograph replica of a painting—now in the Museo del Prado, Madrid—made for Jerónimo Vich y Valterra, the Spanish ambassador to Rome. Other versions survive in the State Hermitage Museum, Saint Petersburg; the Monasterio de las Descalzas Reales, Madrid; and the Szépmüvészeti Múzeum, Budapest. Lacy Armour, Ada Turnbull Hertle, Mary Swissler Oldberg Acquisition, Charles H. and Mary F. S. Worcester Collection funds; Wirt D. Walker Trust; Alyce and Edwin DeCosta and the Walter E. Heller Foundation Fund; Estate of Walter Aitken; Frederick W. Renshaw Acquisition, Marian and Samuel Klasstorner funds; Edward E. Ayer Fund in Memory of Charles L. Hutchinson; Lara T. Magnuson Acquisition, Director's funds; Samuel A. Marx Purchase Fund for Major Acquisitions; Edward Johnson, Maurice D. Galleher Endowment, Simeon B. Williams, Capital Campaign General Acquisitions, Wentworth Greene Field Memorial, Samuel P. Avery, Morris L. Parker, Irving and June Seaman Endowment, and Betty Bell Spooner funds

Size: 118 × 92 cm (46 7/16 × 36 1/4 in.)

Medium: Oil on panel

https://www.artic.edu/artworks/234781/

24 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Christ Carrying the Cross, Sebastiano del Piombo, 1515, Art Institute of Chicago: European Painting and Sculpture

This painting by represents one of the most popular compositions invented by one of the most distinguished painters working in Rome during the High Renaissance. In the 1510s, following an early period in Venice, Sebastiano del Piombo traveled to Rome, where he was drawn into the lively atmosphere of competition between the two great luminaries of the period, Michelangelo Buonarroti and Raphael. Michelangelo took Sebastiano under his wing, teaching him his monumental style and providing drawings for some of Sebastiano’s major commissions. Following Raphael’s death in 1520, the painter and historian Giorgio Vasari stated that“first place in the art of painting was unanimously granted by all, thanks to the favor of Michelangelo, to Sebastiano.” Christ Carrying the Cross draws upon recent developments of an enormously popular iconography by artists including Giovanni Bellini, Giorgione, and Andrea Mantegna, among others. Here, Simon of Cyrene assists Jesus, emphasizing the heavy weight of the cross on his shoulders. A Roman soldier stands behind, his jeering face just visible in the darkness. In the background, the tightly packed composition opens up onto a crowd assembling at the foot of the hill of Golgotha, with two crosses barely visible. The luminous landscape is a hallmark of the artist’s Venetian training. The painting’s dramatic visual impact is a result of the powerful diagonals of the cross; the dynamic, almost sculptural quality of Christ’s clothing; and the pathos of his expression. The popularity of Sebastiano’s composition is reflected in the number of surviving variants that he created over the course of his career. The Art Institute’s version is an autograph replica of a painting—now in the Museo del Prado, Madrid—made for Jerónimo Vich y Valterra, the Spanish ambassador to Rome. Other versions survive in the State Hermitage Museum, Saint Petersburg; the Monasterio de las Descalzas Reales, Madrid; and the Szépmüvészeti Múzeum, Budapest. Lacy Armour, Ada Turnbull Hertle, Mary Swissler Oldberg Acquisition, Charles H. and Mary F. S. Worcester Collection funds; Wirt D. Walker Trust; Alyce and Edwin DeCosta and the Walter E. Heller Foundation Fund; Estate of Walter Aitken; Frederick W. Renshaw Acquisition, Marian and Samuel Klasstorner funds; Edward E. Ayer Fund in Memory of Charles L. Hutchinson; Lara T. Magnuson Acquisition, Director's funds; Samuel A. Marx Purchase Fund for Major Acquisitions; Edward Johnson, Maurice D. Galleher Endowment, Simeon B. Williams, Capital Campaign General Acquisitions, Wentworth Greene Field Memorial, Samuel P. Avery, Morris L. Parker, Irving and June Seaman Endowment, and Betty Bell Spooner funds

Size: 118 × 92 cm (46 7/16 × 36 1/4 in.)

Medium: Oil on panel

https://www.artic.edu/artworks/234781/

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hyperallergic: Chronicling the Rivalry and Camaraderie of Michelangelo and Sebastiano

Sebastiano del Piombo, “The Judgement of Solomon” (c. 1506-9) tempera (lower layers) and oil on canvas, traces of gold leaf (in half-dome) 208 x 318 cm, Kingston Lacy, the Bankes Collection (National Trust) (© National Trust images by Derrick E. Witty)

LONDON — It is fair to say Sebastiano del Piombo is not the first name that springs to mind when thinking of High Renaissance Italy — specifically the artistic hub of Rome during the early 16th century. That role goes to Michelangelo, then working on the immortally iconic Sistine Chapel. Considering that the new exhibition, Michelangelo and Sebastiano, in London’s National Gallery promises in its press release the “first ever exhibition devoted to the creative partnership” between these two artists, and thinking of this year’s earlier Caravaggio show remarkable for its lightness on Carvaggio’s actual paintings, one’s immediate dread is that Michelangelo’s ticket-selling name has been shoehorned into a study seeking to elevate an obscure contemporary of his. How delightful it is then that the show methodically and academically does what it says on the tin: offer compelling instances of collaboration, consistently demonstrated with convincing examples, and reveal the twists and turns of a 25-year friendship and artistic relationship. A happy bonus is how this survey paints an image of a deliciously Machiavellian art world in Rome — all scheming competition and heated rivalry.

Michelangelo “The Entombment (or Christ being carried to his Tomb)” (c. 1500-1) oil on poplar, 161.7 x 149.9 cm (© The National Gallery, London)

As such, it quickly becomes clear that curator Matthias Wivel is not out to champion del Piombo as an unsung master. Throughout the show, his work is shown to be decidedly clunky and lacking in comparison to the finesse and genius virtuosity of Michelangelo. Beginning with the Venetian-trained del Piombo’s arrival in Rome, the focus is exploration of the technical differences between the two artists within the context of fiercely competitive art patronage in Rome. We are thus invited to compare the working method behind Michelangelo’s “Virgin and Child with Saint John and Angels” (c. 1497) — its unfinished state revealing meticulously exact linear planning, green coloring of the dead flesh, and a piecemeal approach regarding covering the canvas surface — with del Piombo’s also unfinished “Judgement of Solomon” (c. 1506–09). With its underdrawing clearly showing hesitancy and a late-stage change in composition characteristic of an improvisatory way of working, it contrasts with Michelangelo’s determined precision. Del Piombo’s preference for an overall painterly fuzziness that evokes mood and atmosphere is consistent with the Venetian school of painting. Elsewhere, del Piombo’s Saints Bartholomew and Sebastian (c. 1510–11) from the doors of the Church of San Bartolomeo in Venice, similarly show a kind of all-over sfumato that fuzzes outlines, giving a murky, moody tone. In his paintings there is none of the distinguishing dynamism of the Florentine Michelangelo’s solid figures and strong composition.

Sebastiano del Piombo “The Visitation” (1518-19) oil on canvas, transferred from wood, 168 × 132 cm Musée du Louvre, Département des Peintures, Paris (© RMN-Grand Palais (musée du Louvre) by Hervé Lewandowski)

This technical introduction to the two artists in the exhibition’s first room thus makes the story that del Piombo was actively promoted by Michelangelo as competition against his “detested” rival Raphael, all the more compelling. In an era of prodigious art commissioning by the ruling religious and political elite (most famously, the powerful Medici family), a highly cynical scene emerges in which del Piombo, specializing in oil painting (tempera being the more common medium), is championed by Michelangelo specifically as a challenger to the city’s only other big oil painter, Raphael. The National Gallery makes a convincing case of del Piombo seeing himself as being in direct competition with the famed colorist skills of Raphael via a progression of works showing del Piombo’s increasing tendency away from murky painting towards pure brilliant color. More juicy illustration of the two artists’ devious machinations in pursuit of patronage comes with the display of their correspondence: del Piombo says to Michelangelo in 1519, having just finished his Raising of Lazarus, “I beg you to persuade Messer Domennico [Boninsegni] to have the frame gilded in Rome, and to leave me to arrange the gilding, because I want to make the Cardinal realise that Raphael is robbing the Pope of at least 3 ducats a day for gilding .” Similarly, in 1520 following Raphael’s death, Michelangelo writes to Cardinal Bernardo Dovizi da Bibbiena persuading him to take on Sebastiano to “share in the work at the Palace, now that Raphael is dead,” humbling adding “You are always granting favours to men of esteem; I beg your Lordship to try out [the favour] with me.”

After Michelangelo “Pietà” (1975) (copy after “Pietà” (1497-1500) St Peter’s, Vatican City) plaster cast from five piece moulds, with wood and iron armature, 174 x 195 cm, Vatican Museums, Vatican City (© Photo Vatican Museums)

In terms of concrete art historical evidence, the show works brilliantly with a methodical presentation of clear examples of the cross-pollination of ideas and designs between the two artists. The Vatican museums have loaned the Gallery a 1975 plaster cast of Michelangelo’s “Pietà” of 1497–1500, shown opposite del Piombo’s Pietà, or “Lamentation over the Dead Christ” (c. 1512–16). (Enjoy it — this is the closest you’ll get to the sculpture; the real thing should never leave its bulletproof case at St. Peter’s cathedral in Rome.) Each piece has its monumental, centrally positioned Virgin arranged to be perpendicular to the horizontal Christ, yet del Piombo makes innovative changes by including a nocturnal setting. More thrilling is the adjacent drawing by Michelangelo: a study of hands (among other bits and bobs), which is placed directly in the line of sight of the Virgin’s hands in del Piombo’s “Lamentation.” So displayed, it’s extremely hard to defy the argument that the former was a preparatory drawing for the latter. If this isn’t exciting enough, on the back of the “Lamentation” panel are sketches the National posits as studies consistent with designs in the Sistine Chapel; suggesting Michelangelo used this panel to sketch out designs and ideas eventually used there.

Sebastiano del Piombo, after partial designs by Michelangelo, “Lamentation over the Dead Christ (Pietà)” (c. 1512-16) oil on poplar, 248 × 190 cm, Museo Civico, Viterbo (© Comune di Viterbo)

The same presentation occurs again for two main del Piombo showpieces, demonstrating a working relationship in which del Piombo blended into his oil painting drawings provided by Michelangelo. The near four-meter-tall “Raising of Lazarus” (1517–1519) — apparently del Piombo’s answer to Raphael’s “Transfiguration” (1516-20) — is surrounded by supporting drawings. Sensationally, del Piombo’s Borgherini Chapel in Rome has been reconstructed here using state of the art printing technology to add visual heft to the translation of Michelangelo’s preparatory drawings.

The rigorous, academic method of display absolutely makes this show. It is undeniable, looking at the key examples in the “Lamentation” and “Raising of Lazarus,” that there is little to distinguish del Piombo as a key Renaissance presence. The latter piece has been in the National’s collection since 1824, yet for all its scale and vibrant colour it somehow still feels uninspiring and workman-like. That del Piombo was not a Renaissance master of the level of Michelangelo is confirmed in the final room covering their parting of ways after

After Michelangelo “The Risen Christ” (c. 1897-8) (copy after the Risen Christ, 1519-21, Santa Maria sopra Minerva, Rome) plaster cast from approximately eight piece moulds consisting of approximately 81 individual pieces 251 × 74 × 82.5 cm, Statens Museum for Kunst, Copenhagen (© SMK Photo by Jakob Skou-Hansen)

1536 by which time Michelangelo has broken from his one-time collaborator, labelling him, according to the final room’s wall caption, “lazy.” Del Piombo’s latter works melt into generic Italian Renaissance fare. The show’s press has trumpeted much about the envelope-pushing reconstruction of the Borgherini Chapel, and boasted of some admittedly excellent loans. The Pietà copy, and the two versions of Michelangelo’s the Risen Christ — one from 1514, loaned by the San Vincenzo Monastery in Bassano Romano, the other a cast of its second version from Santa Maria sopra Minerva in Rome, both surrounded by exceptional preparatory drawings — are a very rare treat indeed. However, Michelangelo’s “Taddei Tondo” (1504–06) doesn’t count since it’s otherwise freely viewable in the Royal Academy, down the road, the presence of the Pietà copy, and the two versions of Michelangelo’s the Risen Christ — one from 1514 loaned by the San Vincenzo Monastery in Bassano Romano, the other a cast of its second version from Santa Maria sopra Minerva in Rome, both surrounded by exceptional preparatory drawings – are a very rare treat indeed.

Most importantly, the exhibition has successfully steered clear of unduly inflating the importance of del Piombo, or presented another painter as an excuse for yet more Michelangelo worshipping. It is fortunate that their 25-year friendship has proven ripe for examination. It provides a rewarding experience that overcomes the complaint by some critics that Michelangelo by nature just dominates any other artist on the bill.

Michelangelo & Sebastiano continues at the National Gallery (Trafalgar Square, London, UK) until June 25.

The post Chronicling the Rivalry and Camaraderie of Michelangelo and Sebastiano appeared first on Hyperallergic.

from Hyperallergic http://ift.tt/2qkhZCj

via IFTTT

0 notes