#aquitainian

Text

The Battle of Tours, October 732 by Charles de Steuben

#battle of tours#battle of poitiers#art#charles de steuben#umayyad#invasion#gaul#franks#frankish#charles martel#aquitainian#muslim#christian#history#europe#european#germanic#abdul rahman al ghafiqi#umayyad caliphate#france#western europe#christianity

61 notes

·

View notes

Text

“One authority recently wrote, ‘The notion of an “Angevin empire” is nothing more than a convenient invention of modern historians.’ Historians tend to reject the possibility of the Plantagenets’ collection of lands achieving permanence and political stability, seeing them merely ‘as the lucky acquisition of a quarrelsome family and not as an institution’. Although these lands are lumped together under the convenient term, Angevin or Plantagenet ‘empire’, few see much evidence for any Angevin concept of imperial doctrine or permanent union. In the Middle Ages the only true empire was the Roman Empire’s successors in East and West. Richard I and John’s seals bore the inscription Rex Anglorum, Dux Normannorum et Aquitanorum et comes Andegavorum; they had no name for the bloc of lands assembled by their father. […]

Henry II and his sons’ concept of their ‘empire’ and its permanence proves a difficult question; no concrete notion of unity for this ‘empire’ seems to have taken shape. Despite centralising tendencies in England and Normandy, the Angevin monarchs made no attempt to impose a uniform administration on their other continental territories. While Norman and English law and administration under Henry II followed closely parallel lines, he followed his father’s advice in his other domains, avoiding imposing uniform laws or institutions and ruling according to their different laws and customs. It is impossible to know exactly what notion John had of his inheritance other than a bloc of family possessions and feudal rights, source of his family’s wealth and political power. Many of his subjects, however, were coming to see the Plantagenets’ congeries of lands as ‘a curious anachronism’. […]

Scholars note too that the Angevin monarchs provided no unifying principle, no common culture that could bind their Anglo-Norman, Angevin and Aquitainian subjects together. Their ‘empire’ was a new creation, and Henry only began to construct administrative machinery in its constituent parts after the 1173–4 rebellion.”

— Ralph V. Turner, King John: England’s Evil King?

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Where John established chaplains and made gifts for the souls of his brothers Henry the Young King and Richard, similar arrangements for Geoffrey were almost non-existent. They appear to be limited to his inclusion amongst the royal relatives for whom chaplains were to pray at Lichfield, arrangements made not by John but by Bishop Geoffrey Muschamp in 1206. There may have been good reason for this lack of attention. Those for whom John made provision were anointed kings and queens who died within the Angevin lands. Geoffrey died in Paris. John does not seem to have provided for the souls of his sisters Matilda, who died in Saxony (1189), and Eleanor, who died in Castile (1214). Yet John could hardly have known these sisters, who left the Angevin lands in 1167 and 1170. He did know Geoffrey, whose final rebellion, unlike that of the Young King, was not in alliance with his brothers. His death was also to John’s advantage, increasing his chances of becoming king. John was in direct competition with the duke of Brittany’s son Arthur for the succession. He may have preferred not to commemorate Geoffrey.

This trend is further confirmed by naming patterns. In naming his legitimate children, John largely followed the example of his own parents, except that Geoffrey, a traditional Angevin name, was absent, as were two names with Anglo-Norman, Angevin, and (or) Aquitainian pedigree: William and Matilda.

-Paul Webster, King John and Religion

#''Arthur had been John's albatross and he knew it'' etc#''we are not looking. we do not see it'' asdfgg#thirteenth century#king john#Duke Geoffrey#prince arthur

6 notes

·

View notes

Photo

My new, sixth illustration of a fantasy knight I retouched to feature the colours and faction iconography I designed for House Lyonheart, the current and reigning dynasty of Kings of Albion in my medieval fantasy world. Both this artwork and it’s associated faction iconography were designed for a low-fantasy setting of my original conception with technology and material culture roughly equivalent to the late medieval and renaissance periods of European history. Where formations of heavily armoured and mounted, aristocratic knights in either suits of full plate armour or heavy coats of chainmail fight alongside professional armies of pikemen and matchlock musketeers. Where medieval-style stone castles are gradually being outsourced in favour of both lavish, sumptuous country estates and devoted military fortifications, or “bastions,” due to the technological advancements made in gunpowder-based, siege artillery. And where fledgling nation-states, most notably in the form of kingdoms and empires begin to look beyond the great oceans and the frontiers of The Known World in search of even greater wealth and territory.

In context to the canon lore of my low-fantasy world, House Lyonheart is the reigning, dynastic house of constitutional monarchs over The Island Kingdom of Albion, a fantasy kingdom loosely inspired by The Kingdom of England under The Lancaster, Tudor, and Stuart Kings during the late medieval to early modern periods of English and European history, while also drawing fantastical sources of inspiration from “Ulthuan,” or the land of The High Elves in Warhammer Fantasy as well as The Kingdom of The Westerlands in Game of Thrones. Unlike the overwhelming majority of nation-states based on the mainland of “The Civilized World,” as rigidly defined and interpreted by both the clergy of The Conservative Church of The New Gods, as well as the nonconformist preachers of the myriad “Reformed” and “Dissenter” Churches of The New Gods, The Kingdom of Albion under the dynastic rule of House Lyonheart has embraced a limited form of consensual government known as “constitutional monarchy,” where the executive, legislative, military, fiscal, and religious powers of House Lyonheart as the longtime and reigning dynasty of Kings of Albion have been subjected to the rule of law, as well as bounded by the consent of Albionic “parliament,” a bicameral legislative body invested with the powers of raising and passing state legislation as well as the levying of taxes with or without the consent of The Kings of Albion. Albionic Parliament as the national, legislative body of The Kingdom of Albion consists of both an upper “House of Lords” containing representatives of the greater and lesser houses of feudal aristocracy and nobility within The Kingdom of Albion, as well as representatives of both the ecclesiastical and monastic clergy of The Conservative Church of The New Gods as the official, state-sanctioned religion of The Kingdom of Albion, as well as a far more recent, lower “House of Commons” containing representatives of the country gentlemen, the bourgeoisie, and the merchant guilds with The Kingdom of Albion. The House of Lords as the upper, senior house of Albionic Parliament came into existence following a baronial revolt against Edward Shortsword as 31st King of Albion and former head of House Lyonheart following the calamitous and failed wars of Aquitainian Succession to usurp House Williamson as the lawful and legitimate Kings of Aquitaine and the subsequent drafting of “The Magna Rhetra” as a codified constitution governing the various bodies of Albionic Common Law that were first codified by Albionic court scribes and clergymen under the reign of Artorius the Lyonhearted as the culturally Southern Aquitainian grandson and heir apparent to Hengist Skullsmasher, the first King of Albion and Founding Head of House Lyonheart. The House of Commons as the lower, junior house of Albion’s parliament, by contrast, came into existence following a massive peasant uprising against Robert III as the 40th and late King of Albion and former head of House Lyonheart after a decade of brutal, extortionate taxation levied to in order to pay for the king’s ransom imposed by House Williamson as The Aquitainian Monarchy after his defeat and subsequent capture in The Battle of Tourangeau at the hands Prince Tancred Williamson Duc de Chambord in the wake of the last great Albionic Invasion of Aquitaine.

Although born of House Lyonheart’s disastrous and failed wars against The Kingdom of Aquitaine, both the constitutional monarchy and parliamentary houses of legislation that distinctly characterized the government and society of The Kingdom of Albion under the rule of House Lyonheart has resulted in a fairer, more consensual political and social system that has protected the subjects of The Kings of Albion from the brutal economic recessions and extortionate taxation that became synonymous with the perpetual warfare, cutthroat political intrigues, and brutal religious upheaval that characterized the kingdoms and empires based on the continental mainland of The Civilized World, whose hereditary monarchs and princes universally aspired to the model of House Williamson and The Kingdom of Aquitaine as the “paragon,” “exemplar,” “ideal,” or otherwise “gold standard” of a strong, powerful, and prestigious, prolific, and illustrious absolute monarchy who had finally achieved the centralization of their kingdom into a proper nation state through their ancient, carefully cultivated and manicured political alliance forged with The Conservative Church of The New Gods based in The Holy Sept in Romulus as the official, state religion of The Kingdom of Aquitaine, as well as their gradual pacification of the legislative and military autonomy of the great houses of feudal aristocracy through the superimposition of “Aquitainian Parlements,” or “royal law courts,” over the historic regions of jurisdiction of both the feudal, aristocratic legal customs and traditions of Northern Aquitaine, as well as the old Cosmopolitan, Classical Romulan law codes of Southern Aquitaine left over from the days of “The Romulan Empire” or “The Empire of Mankind Primus” during the long forgotten epoch of “Classical Antiquity” within the long and storied history of “The Civilized World.” As well as using the power and authority of “The Aquitainian Parlements” to organize a national, professional, state funded “royal” army at the expense of the feudal, private levies of the great houses of nobility and aristocracy within The Kingdom of Aquitaine.

Due to the executive, legislative, military, fiscal, and religious restrictions imposed on House Lyonheart as the hereditary, dynastic Kings of Albion through the combination of the unique political and social system of constitutional monarchy and parliamentary legislature, The Kingdom of Albion under the hereditary rule House Lyonheart has remained relatively aloof from the perpetual warfare, cutthroat political intrigues, and brutal religious upheaval that came to characterize the aspiring absolute monarchies based on the continental mainland of The Civilized World. However, under the reign of Edmund IV as the 41st and reigning King of Albion and the current Head of House Lyonheart, The Kingdom of Albion has been officially declared both a political and religious asylum for religious subscribers to The “Reformed” Faith of The New Gods derived from the theological reforms preached and published by Karl Von Luxembourg at Die Universität Wörtzburch in The Empire of Mankind, as well as religious subscribers to any of The “Dissenter” Faiths of The New Gods that either directly or indirectly descend from The “Dissenter” Theology of the Aquitanian vagabond and theologian Cassyon Dufresne as originally preached in “The Cathedral of Les Œillets” in “The Borderlands Confederacy” of culturally “Austere” or “Northern Imperial” states strategically situated between Der Reichstaat and Die Markgrafschaft Brannenborg within The Empire of Mankind. Despite The Kingdom of Albion’s international status as a political and religious asylum for all religious subscribers to both the multitude of “Reformed” and “Dissenter” Churches of The New Gods fleeing from religious persecution and marginalization at the hands of religiously Conservative monarchs and aristocrats, the fourteen year old Edmund IV as the 41st and reigning King of Albion and the current Head of House Lyonheart has already been officially proclaimed as “Defender of The Faith” by elderly Archpatriarch Vexillarius IV as the 299th and reigning Bishop of Romulus and the current Head of The Conservative Church of The New Gods for his written thesis’ openly condemning both the theological reforms of Karl Von Luxembourg as the leading and titular “Great Reformer” to The Conservative Church of The New Gods, as well as Edmund IV’s own maternal grandfather Friedrich I, “Der erster und herrschend König von Middenland” und “Der Gründungschef von Hohenrotbart” and Albrecht Von Biermann, “Der herrschend Markgraf von Brannenborg,” “Der momentan Chef von Hohenbiermann,” und “Kurfürst Des Selbst Kaiserreich der Menscheit” for their actions in officially confiscating the lands, property, and treasuries the ecclesiastical and monastic clergy of The Conservative Church of The New Gods based in Das Königreich Middenland and Die Markgrafschaft Brannenborg, respectively, as the first and second hereditary, dynastic rulers in both the recorded history and the enormity of The Known World to officially renounce The Conservative Faith of The New Gods in favour of The Luxembourgian Reformation on behalf of both their houses and subjects.

Outside of his affairs concerning the religious upheaval surrounding both Karl Von Luxembourg’s and Cassyon Dufresne’s respective reforms to The Conservative Church of The New Gods on the continental mainland of The Civilized World, Edmund IV as 41st and reigning King of Albion and Current Head of House Lyonheart has used the restrictions on any continental military, political, economic, and religious ambitions in The Civilized World imposed by The Kingdom of Albion’s unique system of constitutional monarchy and parliamentary legislature to develop a new, and enduring policy of overseas colonialism and mercantilism devoted to the production and acquisition of luxury goods and natural resources by granting legally exclusive “letters of marque” or “colonial charters” to “trade companies” of merchants, traders, and professionals willing to use their own capital to establish trade posts and colonies in overseas trade theatres in order to export luxury goods and natural resources harvested and produced in “virgin lands” back to The Kingdom of Albion in return for generating a handsome profit from their corporate ventures. In addition to being granted legally exclusive monopolies over certain trade theatres with these “letters of marque” or “colonial charters,” these “trade companies” created by the 41st and reigning King of Albion and the current Head of House Lyonheart would also be given unrestricted political and military autonomy over any acquired and developed colonies and territories established in overseas trade theatres, with the most prominent and lucrative Albionic colonial possessions being established by “The King’s Landing Trade Company” in “New Albion,” and “The World’s End Trade Company” in “Arcadia.” To accommodate his ambition of colonialism and mercantilism, Edmund IV as the reigning King of Albion and the current Head of House Lyonheart has diverted The Kingdom of Albion’s annual, national budget in favour of a powerful, professional, state-funded “royal” navy over a strong standing army, in contradiction to the traditional and historic policy of all historic Kings of Albion before him, and to “subsidize” or otherwise “invest in” the business and industry of trade guilds devoted either to the construction of seafaring vessels or the production of maritime goods and resources on an industrial scale, as a means of bolstering both his ambitions to develop The Kingdom of Albion’s mercantile trade through the establishment of overseas colonies and territories in different trade theatres, and to give his growing professional navy the necessary assets and resources needed to secure the maritime trade lanes established between any overseas colonies and territories with The Kingdom of Albion.

In terms of The Kingdom of Albion’s standing military left over from Robert III’s failed war with House Williamson and The Kingdom of Aquitaine, the infantry regiments serving in the national, professional, state-funded “royal” army of House Lyonheart and The Kingdom of Albion oddly continue to employ peasant levies of billmen and longbowmen in an age when the overwhelming majority of fledgling nation-states and their ruling, dynastic houses based on the continental mainland of The Civilized World have moved on to employing professional regiments of pikemen and matchlock musketeers as the line, core, and bulk of their campaigning armies. Although, like the overwhelming majority of continental, mainland states of The Civilized World, The Kingdom of Albion under the constitutional monarchy of House Lyonheart has fully embraced the employment of gunpowder-based, siege artillery that is so inherently vogue of the current epoch of the post-chivalric battlefields of The Civilized World, fully displacing it’s outdated arsenal of classical and feudal-style windlass artillery pieces such as catapults, trebuchets, ballistae, mangonels, and onagers that have been both historically and traditionally employed on the battlefields of The Civilized World since the days of the Classical Mycaenean “Poleis” or “city states” that once flourished during the long forgotten epoch of “Classical Antiquity” in recorded history of The Civilized World. Despite the seemingly antiquated military technology and tactics employed by the billmen and longbowmen serving in the traditionally strong, standing army of The Kings of Albion. The mixed formations of Billmen and Longbowmen employed personally by House Lyonheart as the constitutional monarchs to The Kingdom of Albion are completely and perfectly capable of holding their own line against the more professional, pike and shotte infantry regiments employed by continental powers in The Civilized World such as Le Royaume d’Aquitaine, Das Königreich Middenland, and Die Markgrafschaft Brannenborg.

#coats of arms#heraldry#shields#medieval#renaissance#chivalry#knights#plate armour#painted armour#black armour#blackened plate#gilding#swords#scuta#fantasy#fantasy world#graphic design#art#Robert III#Edmund IV#Kaitlin Lyonheart#Edward Fitzroy

4 notes

·

View notes

Note

🎶✨when you get this, put 5 songs you actually listen to, then publish. Send this ask to 10 of your favorite followers/ mutuals (non-negotiable, positivity is cool) ✨🎶

En Todo Tempo Faz Ben -Court of Alfonso X (I just love how jaunty it is)

2. Telling The Truth 2004 -Phoenix Wright: Ace Attorney (The whole AA soundtrack goes hard, do yourself a favour and listen to it)

3. Gas Gas Gas -Manuel (Been digging Eurobeat quite a bit recently)

4. Shrooms -Jerobeam Fenderson (The visuals for this are actually the waveforms of the music displayed on an oscillosope!)

youtube

5. Robot Rock -Daft Punk (Engineer Gaming)

There's some funky ones here so I hope you dig at least one of them

Honourable Mentions:

This choral piece from 1300s Aquitaine

youtube

I've also been kinda interested in this instrument called the Trumpet Marine, which in all honesty doesn't sound amazing but is so utterly unique I love it.

Have a lovely evening, all!

1 note

·

View note

Text

On the Treaty of Verdun and its Consequences

Louis the Pious died in 840. Three years later his empire was divided into three independent kingdoms. The Treaty of Verdun was the first great European accord whose consequences proved durable, and its terms came as no surprise to contemporaries. The idea of partitioning the empire was not new. In accordance with Frankish custom, Charlemagne had provided for the division of his legacy in 806, and Louis the Pious had done so several times. Nevertheless, the death of Louis did not ensure the implementation of the scheme he had proposed. Only after three years of warfare and negotiation did the three brothers, Lothar, Louis, and Charles, arrive at a solution of their own formulation.

Prelude and Circumstances

The death of his father prompted Lothar to forget the arrangements he had agreed to at Worms in 839. He meant to claim it all, as Nithard reports:

“When Lothar heard that his father had died, he dispatched messengers everywhere, especially across all of Francia. They announced that he would take over the empire that had once been given to him. He promised that he would allow everyone to keep the benefices granted by his father, and that he desired to augment them. He ordered that persons whose loyalty was doubtful should promise their fealty. Moreover, he commanded that they should come before him as soon as possible, and that those who refused to do so should be executed.”

Lothar’s position appeared in fact quite strong. Louis of Bavaria had only a few troops and faced threats of Saxon revolt and Slavic incursion. Lothar, moreover, could count on the help of his nephew Pippin II, who led a part of the Aquitainian nobility in a revolt against Charles the Bald.

Lothar Versus Charles

Now seventeen, Charles had been established by his father in Aquitaine, where his mother Judith also resided. Because he needed to ensure the allegiance of followers north of the Loire and west of the Meuse, he embarked on a trip across his realm. But no sooner had Charles moved on from a locale, than Lothar's promises and threats seduced the local nobility. Thus, according to Nithard, as Lothar approached the Seine, Abbot Hrlduin of St. Denis, Count Gerard IT of Paris, and Pippin, the son of Bernard of Italy, “chose like slaves to break their word and disregard their oaths rather than give up their holdings for a little while.” Lothar sent envoys everywhere, including Provence and Brittany, to exact oaths from the nobility. Alternating flattery with threats, he promised Charles protection and a new partition, and meanwhile schemed to undermine his noble support with the help of repeated truces. Charles, however, also worked relentlessly to shore up his position by renewing ties with old supporters and gaining new ones. At Orleans, he received a pledge of fealty from Count Warin of Mâcon; at Bourges, he worked to win over Bernard of Septimania from Pippin II; and at Le Mans, he secured the support of Lambert III, count of Nantes. Nevertheless, the fruits of these efforts remained uncertain because Charles could not be everywhere at once. To obtain lasting success, he needed to defeat Lothar’s numerically superior forces. For this, Charles would have to make common cause with his brother Louis, who had withdrawn into Bavaria after suffering similar desertions among his followers.

The Alliance of Louis and Charles

In the spring of 841 fortune smiled on the two brothers. Charles managed to force a crossing of the Seine, and Louis arrived in the west to meet him after defeating Adalbert, Duke of Austrasia. The two princes combined forces near Auxerre. With the agreement of the bishops, they appealed for a “judgment of God,” that is, a trial by battle. On 25 June 841, the army of Charles and Louis squared off against that of Lothar and Pippin II at Fontenav-en-Puisave, near Auxerre. As lay-abbot of St. Riquier, die historian Nithard was also a participant, and he declared that “it was a great battle.” The engagement was, in fact, one of the greatest and most horrific of the Carolingian period. Contemporary chroniclers speak of thousands of dead: “a massacre whose equal no one could recall ever before witnessing among the Franks.” A certain Angilbert left an echo of the fratricidal slaughter in a rhythmic Latin poem:

‘May neither dew nor rain nor shower moistens that meadow where men most skilled in war did fall, who were lamented with tears by fathers, mothers, brothers, sisters, and friends.

From a hilltop, I gazed upon the valley below where brave Lothar repulsed his enemies and beat them back in flight across the brook.

Likewise on the side of Charles and Louis, the fields are white with the linen garments of the dead, as they are wont to be with birds in autumn.

The battle deserves no praise; it should be no subject of fine song. North, south, east, and west, may they all lament those who died by such a penalty.”

Whatever the assessment of Angilbert, his master Lothar was defeated and fled to Aachen. After celebrating a Mass of thanksgiving on the field of victory, Louis and Charles received a number of nobles who had waited to see the issue of the battle. Thus Bernard of Septimania arrived from his nearby camp, and committed his sixteen-year-old son William to the care of Charles the Bald. The young man became as much a hostage as a vassal, and his mother Dhuoda responded to his absence by composing for him her famous Handbook, where in she outlined a program of education for a young Christian nobleman.

The Strasbourg Oaths (842)

Despite his defeat, Lothar continued to intrigue, making new offers to Charles in an effort to break his alliance with Louis of Bavaria. The two allies, however, were firm in the belief that God was on their side, and they sealed their pact of cooperation. On 12 February 842, they exchanged oaths to this effect at Strasbourg in the presence of each other’s troops:

“For the love of God and for our Christian people’s salvation and our own, from this day on in as much as God grants me knowledge and power I shall treat my brother with regard to aid and everything else as a man should rightfully treat his brother, on condition that he do the same for me. And I shall not enter into any dealings with Lothar which might with my consent injure my brother.”

Nithard preserved the foregoing words, and he did so not once, but twice, in two similar yet decisively different forms. To make himself clear to the other’s followers, each brother pronounced his oath in their language: Louis spoke in “Romance,” while Charles spoke in lingua teudisca, or “Germanic.” Thereupon their respective vassals proceeded to swear an oath in their own vernacular—also recorded by Nithard—promising to abandon their lord should he break his pledge. Thus the Strasbourg Oaths have come to mark not only a momentous diplomatic and political event, but also an important step in the linguistic history of Europe. In order to celebrate the harmony that reigned between the allies, games were often arranged, as Nithard describes:

“They came together wherever a show could be accommodated. With a whole multitude gathered on either side, each with an equal number of Saxons, Gascons, Austrasians, and Bretons, they first rushed at full speed against one another as if they meant to attack. Then, one side would turn back, pretending to flee to their teammates under the cover of shields, but countering, they would dart back after their former pursuers. Finally, both kings and all the young men spurred forward their horses with immense clamor and lances in hand, and they gave chase by turns as the other side took flight. It was a show worth seeing thanks to the outstanding participants and good discipline. In such a vast array of different players no one dared hurt or abuse another, as often happens even when the games are small and among friends.”

Lothar Submits

Finally, the two brothers marched on Aachen. They occupied the palace, though Lothar had already carted away the treasury. With the accord of the bishops, they then proclaimed Lothar unworthy to govern, and they proposed to divide the empire between themselves. Twelve commissioners were appointed on each side to determine their respective shares. Thus, Lothar had to know that an indefeasible alliance now united Louis and Charles. After Fontenay, the Strasbourg Oaths and the capture of Aachen, the ambitious emperor had no choice but to yield. He abandoned his erstwhile ally, Pippin II. With great generosity, Charles and Louis agreed to resume negotiations on a new basis aimed at a tripartite division of the empire, excluding Aquitaine, Bavaria, and Lombardy, since these regions were considered respectively as the home domains of Charles, Louis and Lothar.

Negotiations (Spring 842-August 843)

It was high time for the brothers to come to terms. Frankish political turmoil had dramatically emboldened foreign sea-borne raiders, who now went so far as to pillage important centers like Quentovic and even Rouen. To dislodge one group of Northmen, the monks of St. Wandrille had agreed to pay an enormous tribute, and thereby introduced an inviting precedent. A group of Danes also settled themselves, with Lothar’s consent, on the Frisian island of Walcheren and some neighbouring places. In Provence, Muslim raiders attacked Marseille and Arles, while other Arab forces made inroads against Benevento in southern Italy. Finally, the usual restiveness of Aquitaine, Brittany, Saxony, and the Slavs posed a host of additional challenges.

The Difficulties

Nevertheless, the negotiations were to last for well over a year, such was the mistrust of the parties and the difficulty of the issues involved. On 15 June 842, the three brothers came together near Mâcon, and agreed to keep the peace until autumn, when a meeting of delegates was scheduled to convene on 30 September for the purpose of dividing the empire equally and fairly. This gathering was scuttled due to fears aroused by Lothar’s behaviour. Another meeting successfully convened on 19 October 842 at Koblenz, where the Rhine separated the camps of the two delegations, and the abbey of St. Castor served as a site for their deliberations. Although Charles and Louis had originally agreed that Lothar should choose first among the three parts of the kingdom, Lothar’s envoys cavilled over the terms of a “fair and equitable partition” in face of the avowed ignorance of all concerning the empire’s extent and resources. Although Charles and Louis had offered him everything between the Rhine in the east and the Meuse, Saône, and Rhone in the west, Lothar wanted, in addition, those portions of the Carolingian heartland that lay west of the Meuse in the region of the Charbonnière Forest. In the end, the protests of Lothar’s delegates over what was “fair and equitable” backfired. It was decided that no decision could be made until a survey of the empire was taken to ensure a just partition. The truce between the brothers was twice extended while commissioners worked to assess the resources of the empire. Though arduous and long, their work was furthered by inventories (descriptiones) listing bishoprics, religious foundations, counties, and royal properties.

Charles’s Marriage

Meanwhile, Charles the Bald used the truce to consolidate his position. He married Ermentrude, the daughter of Count Odo of Orléans, on 14 December 842. Odo stemmed from a family based along the Middle Rhine which was probably related to that of Gerold, Charlemagne’s brother-in-law. Odo himself had married Engeltrude, the sister of Count Gerard and the seneschal Adalhard, one of the most powerful lords in western Francia. Nithard wrote at length concerning Charles’s choice of bride:

“Louis the Pious in his time had loved this Adalhard so much that he did whatever Adalhard wanted everywhere in the empire. Adalhard cared less for the public good than for pleasing everyone. He persuaded the emperor to distribute privileges and public property for private use, and since he arranged for whatever anyone requested, he totally ruined the government. By this means it happened that he could bend the people to do whatever he wanted.”

Charles no doubt hoped to gain the favor of Adalhard through his marriage, even though his brother Gerard had joined Lothar’s cause. For Nithard added: “Charles entered into this marriage above all because he thought he could attract the largest following with Adalhard.” Charles spent the rest of the harsh winter of 843 with his new wife in Aquitaine, prosecuting the fight against Pippin II. Spring brought him a series of unpleasant reports: Empress Judith died on 13 April; Scandinavian raiders captured Nantes on 24 June; and an important victory was scored by the Bretons under the leadership of their duke, Nominoë. The young king required freedom to act, and this largely presupposed a resolution of the disputes surrounding the partition. In August 843, the three brothers agreed to meet at Dugny, near Verdun, and there they concluded their momentous transaction.

The Treaty of Verdun and Its Terms

The text of their agreement has not been preserved, but the boundaries of the three kingdoms established around the kernels of Aquitaine, Lombardy, and Bavaria can be determined from indirect evidence. To Charles went everything to the west of a line that roughly followed the Scheldt, Meuse, Saône, and Rhone rivers, while Louis acquired everything east of the Rhine and north of the Alps. Retaining his imperial title, Lothar received the central strip of territories extending from the North Sea to Italy. Still, it is not enough to trace the map of the three kingdoms of the Treaty of Verdun, we must also consider the underlying reasons for the boundaries that emerged.

The Rationale of the Partition

Since the nineteenth century, historians, especially in France and Germany, have used a variety of rationales to account for the formation of the three kingdoms. In the heyday of the principle of nationality, the French historians Jules Michelet and Augustin Thierry believed that the negotiators of 843 had sought above all to do justice to national sentiment and linguistic distinctions. Hence, “France” and “Germany” were born at Verdun, while the portion assigned to Lothar was destined to break up into pieces that later emerged as the Netherlands, Belgium, Switzerland, and Italy. This idea proved so durable that Joseph Calmette could still remark in his generally balanced synthesis “Effondrement d'un empire et la naissance d'une Europe (Paris, 1941)” that the Treaty of Verdun had ‘Violated nature” in establishing a no-man’s-land between France and Germany. The negotiators had cut into “the living flesh of France and Germany, and the wounds thus made had never healed, and had even reopened at periodic intervals.” In his “Naissance de la France (Paris, 1948)”, Ferdinand Lot was in general more circumspect. Although he noted that “no concept of race or language had ever determined the shape of Carolingian or Merovingian partitions,” he added that “having experienced the rupture of their close tics, the future France and Germany could take stock of their individuality, until then confused, and live henceforth independent existences.” Moreover, he judged that “without the amputation of her eastern flank, France could never have arisen: France could only live at the cost of losing an arm.”

At the time, however, there was no “France,” no “Germany.” Charles the Bald made a kingdom composed of diverse peoples speaking very different languages. Precious little could serve to unite the Goths of the Spanish March, the Gascons, the Aquitainians, the Bretons and the peoples of Neustria and Flanders. To the east, Louis of Bavaria could scarcely claim greater cohesion among his subjects, despite the contrary assertions of German historians of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. To explain the grounds for the partition enacted at Verdun, we must look beyond nationality and nationhood. Some historians have proposed that the emphasis had lain on the economic needs of each of the future kingdoms. In his “History of Europe”, written in 1917 and first published in 1936, Henri Pirenne stated that “the point of view espoused by the negotiators was dictated by the prevailing system of economy.” Each partaker in the division was to receive an area whose revenues were more or less equal. On the basis of this idea, Roger Dion noted in 1948 that each allotment divided the various economic zones of western Europe along a north-south axis: the coastal pasturelands of the north, the central cereal plains, forests, and wine regions, and finally the salt marshes and olive groves of the south. However intriguing, these hypotheses fail in their turn to account for all the facts. Moreover, the Carolingian princes had not read Aristotle and learned from him that polities should be self-sufficient.

The Belgian historian François Louis Ganshof turned to contemporary sources to penetrate the rationale of the partition of 843, and we shall follow his example. On the subject of partitions, Nithard had, of course, noted two significant facts: first, that “fertility or equal size of the lands apportioned was not considered so much as the fact that they were adjacent and fitted into the territory already held by each brother”; and second, that “Lothar complained about the fate of his followers, since in the share that had been offered to him he would not have enough to compensate them for what they had lost.” Nithard’s remarks suggest the most satisfactory explanation. The brothers were most concerned about the fate of their followers, for without their help, they could do nothing.

Therefore, they had to keep the benefices of their vassals within their respective kingdoms, since it was recognized that no vassal could pay homage to several lords. To avoid the likelihood of incompatible obligations, Charlemagne had articulated a key principle in his Divisio regnorum of 806: “The followers of each king shall each receive their benefices inside the realm of their master.” Likewise in the Ordinatio imperii of 817, Louis the Pious had instructed that “each vassal should hold his benefices only within the dominion of his lord, and not in that of any other.” This concern explains, for instance, why the border of the western kingdom of Charles the Bald crossed the Saône and took in a part of Burgundy that included the holdings of his vassal Warin, count of Mâcon, Autun, and Chalon and abbot of Flavigny. Louis of Bavaria likewise received a section of the left bank of the Rhine including the bishoprics of Mainz, Worms, and Speyer, not on account of the local vineyards, as a later chronicler would report, but to keep the lands of powerful episcopal vassals inside his kingdom.

Hence, the problems of benefices and fealty weighed heavily in the negotiations that led to the treaty ratified at Verdun. As Fustel de Coulanges pointed out in the nineteenth century, “the partition was not undertaken for the people, but rather for the vassals.” With the help of maps, we can easily see that each brother wanted to maximize the number of his abbeys, bishoprics, and fiscal domains in Francia. The heartland of the empire was home to choice benefices held by great Austrasian families, but there also lay the main state residences that each king strove to retain for his own use, enjoyment, and profit. Each of three brothers was a “king of the Franks.” They reigned jointly over their respective fractions of the “Kingdom of the Franks,” while they separately ruled Aquitaine, Bavaria, and Lombardy.

The Consequences of the Partition at Verdun

Those who divided the empire could not possibly have foreseen that the borders fixed at Verdun would determine the map of medieval Europe, and furthermore that the boundary between the kingdom of Charles the Bald and the empire of Lothar was destined to survive for centuries. Throughout the Middle Ages, the Scheldt River separated the “kingdom” from the empire; the Saône divided Burgundy into two parts: the duchy to the west, and the county—later known as Franche-Comté—to the east, while further south one passed once again from the “kingdom” to the empire by crossing the Rhone. The border of the “kingdom” as fixed at Verdun is still visible today near the Argonne plateau along the line separating the modem French départements of Meuse and Marne. To the southeast, the Pyrenees did not represent a frontier at all, since Charles possessed Spanish lands that remained part of the “kingdom” until the reign of Saint Louis (1258). The boundaries between the realms of Lothar and Louis would later prove less stable as a consequence both of further partitions made among the emperor’s heirs and of the territorial ambitions of the German kings. Yet there again we find the outline of the future Germany. To my mind, the Treaty of Verdun was the “birth certificate” of modem Europe. For contemporaries, the momentous event marked the end of the great ideal of unity. Florus of Lyon reacted with bitterness:

The mountains and hills, woods and rivers, springs,

High cliffs and deep valleys too.

All bemoan the Frankish people, which, after its rise to empire by the gift of Christ,

Now lies covered in ashes.

It has lost both the name and the glory of empire,

and the united kingdom has fallen to three lots.

For there is no longer any one recognized as emperor:

instead of a king, there is a kinglet; for a realm, but the fragments

thereof.

This Lament on the Division of the Empire voiced the concerns of the clerical party, who had hoped to maintain imperial unity and who deeply feared that division would weaken the church. The ecclesiastical provinces and individual bishoprics were also partitioned as a result of the Treaty of Verdun. Thus, the sees of the province of Cologne were variously assigned to the separate realms of Lothar and Louis; similarly, the bishop of Strasbourg lived in Lothar’s empire, while he remained a suffragan of the archbishop of Mainz, a subject of Louis. Sometimes, a single diocese was divided into areas controlled by different sovereigns, as happened with Reims, Münster, and Bremen. A host of additional problems arose from the fact that many abbeys and bishoprics owned parcels of land situated in far-off regions, and these now came under “foreign” political control. Nevertheless, circumstances militated against the unitary ideal. Political realism dictated the creation of new dominions that could be ruled effectively by separate kings and their followers.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

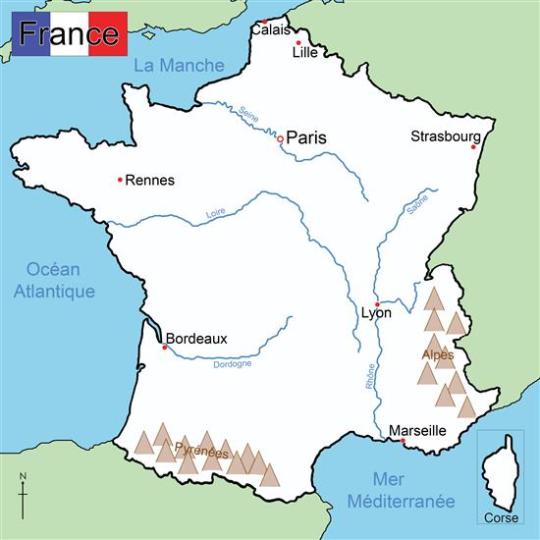

The extent of the physical settlement of Franks as opposed to the political control by Franks varied enormously across the kingdom. In the east and the north along the lower and middle Rhine the settlement was extremely dense. In these regions the Roman presence, in the form of clerics, merchants, and the remains of the Jmreaucracy, continued only within the walls of cities such as Cologne, Bonn, and Remagen. In the countryside, the remaining Roman peasants were absorbed into the nonfree dependents of the Franks, whose system of farms and estates replaced the previous Roman organization of the countryside.

Between the Seine and the Loire, the Frankish presence was even less significant; archaeological and linguistic evidence suggests scattered islands ~£ Frankish settlement in an overwhelmingly Gallo-Roman countryside. South of the Loire, the Frankish presence was even less in evidence. Prior to 507, the region had been largely unaffected by its Visigothic lords, who mostly resided in towns from which they controlled the countryside with the assistance of the Aquitainian aristocracy. Little changed with the Frankish conquest in terms of actual population. Certainly some Franks were sent Romans and Franks in the Kingdom of Clovis 115 · south as counts and others no doubt settled in the rich cities of Aquitaine, but these scatterings of Franks had little effect on · tl].e population, its language, or customs.

the core of the Frankish kingdom had been constituted; a loose confederation of barbarian chieftains had been replaced by a single ruler whose wealth was matched only by his capacity for violence; an uneasy alliance of pagan and Arian barbarians and Christian Romans had been replaced by a kingdom unified culticly under a Christian king recognized by 116 Before France and Germany the emperor in Constantinople and supported by orthodox bishops, the representatives of the Gallo-Roman elite. In spite of the disunity and internecine violence that characterized the reigns of Clovis's sons and grandsons, the transformation of the West would continue along the lines he had begun ..

0 notes

Text

“…Eleanor’s wealth, land, and wit enabled her to be a formidable political figure in Europe. Louis VII and Henry II married Eleanor because her inheritance considerably enlarged and enriched their respective holdings. However, the kings could only oversee Aquitaine with Eleanor by their side, because her title was what gave them authority. Her sons, Richard and John, appointed Eleanor as queen-regent above their own wives.

Of Eleanor’s ten children, only one son died during childhood; the rest of her children became queens and kings or married into influential families. Her grandchildren and other royal descendants shaped much of Europe’s history, including that of England, Denmark, Castile, and Sicily, giving her the well-deserved title of “grandmother of Europe.” Eleanor’s influential and political presence in Europe had a long-term impact on medieval noblewomen’s application of power.

…Eleanor gained the title Queen of France upon her marriage to Louis VII in 1137. The couple was both young and inexperienced, prompting rash decisions and encouraging counselors to vie for the king’s ear and favor. The years before the Second Crusade would reveal the young king’s lack of judgment and reckless decisions, often spurred on by his wife. Much to the displeasure of the courtiers, Eleanor exhibited significant influence over her husband through intercession in the marriage’s early years.

Intercession constituted a vital component of a queen’s duty in the Middle Ages, functioning “as an acceptable avenue of queenly influence and power,” precisely because queenship “was a type of motherhood” where the queen sought the best interest for her “children,” the people. Even if denied official political involvement, the queen could still intervene and persuade the king, because of the intimate, personal access to her husband.

Eleanor visibly exercised her rights of intercession with Louis on one major occasion. Petronilla, Eleanor’s younger sister, was romantically involved with Count Ralph of Vermandois, which Eleanor wholeheartedly supported. Louis, “incapable of resisting the insistence of Eleanor,” found bishops to nullify the count’s previous marriage, and marry Petronilla and Ralph. The scandalous marriage so outraged the rejected wife’s uncle, Theobald of Blois-Champagne, that he convinced the pope to excommunicate the newlyweds. Louis VII, indignant from Theobold’s opposition, invaded Champagne in the summer 1142.

Tragically, when Louis’s men invaded the town of Vitry, they burned to the ground the church providing refuge for the townspeople. Several hundred people burned to death inside, while the king helplessly watched from outside the town. Louis is reported to have transformed into a different man after the massacre, becoming staunchly religious and seeking the counsel of Bernard of Clairvaux and Suger of Saint-Denis.

Despite the tragedy, Eleanor stubbornly pushed for the revocation of the couple’s excommunication, possibly bribing two cardinal deacons. In 1148, the Church finally divorced Ralph of Vermandois and his first wife, allowing the count and Petronilla to officially be wed. Eleanor was secretly blamed for the disaster, and her influence over Louis quickly deteriorated as the king now sought the advice of clergymen.

Regardless of the tension within the royal couple, Eleanor still held the title of Duchess of Aquitaine. Despite being king of France, Louis VII could not govern Aquitaine without Eleanor. While their marriage entitled him as duke, Louis needed to earn authoritative legitimacy over the Aquitainians by associating himself with the lawful duchess. He attempted to accomplish this by identifying himself with the duchess-queen’s lineage of male ancestors. Most of Louis’s Aquitanian charters, an official grant of authority or rights, confirmed the acts of Eleanor’s ancestors, conveying the king’s attachment to her family. Aquitaine was never a truly united duchy, but rather constructed of factions overseen by barons who rarely agreed. These barons despised rule from anyone besides an Aquitanian, which is why Louis attempted to graft himself into Eleanor’s lineage and identify as an “Aquitanian.”

…French society denied Eleanor unrestricted power over Aquitaine, even as heiress, and she held no official authority as queen of France. Especially under Louis and his father, Louis VI, the French government centered on the king’s authority, reducing the queen’s role and power. One of the first victims to this centralization, Eleanor’s power extended only to Aquitanian matters and personal influence. During the twelfth century, men’s intolerance for powerful women grew, preferring subordinate and weak-willed women.

The Church instigated this low perception of women by portraying females as the evil seed of Eve, inheriting the temptress’s wickedness. The Church promoted the Virgin Mary as a role model for good, subordinate women to combat their inherited sinfulness. Powerful women who defied traditional feminine standards, like the queen-duchess, were considered unnatural and wrong. It is understandable why Eleanor experienced this diminishing of female power, with Louis’s father initiating the decline and with great religious men being her king’s closest advisors.”

- RITA SAUSMIKAT, “Well-Behaved Women Rarely Make History: Eleanor of Aquitaine’s Political Career and Its Significance to Noblewomen.”

44 notes

·

View notes

Text

"A handful of months after her husband's death and burial, Joan married Edward of Woodstock, Prince of Wales in another marriage per verba de praesenti. Perhaps it was the knowledge that it would not be a particularly popular marriage with King Edward III who would have wanted a more prestigious bride than Joan, and one without the scandal attached to her name.

It took a papal dispensation, much money and a promise to found two chantry chapels in Canterbury Cathedral for Joan and Edward to straighten out the mess of this first marriage. Eventually it was complete and they were married again, this time with all the legal trappings at Windsor, in October 1360. The tradition that King Edward and Queen Philippa disapproved seems to be without evidence. They attended the marriage and visited the happy couple at Berkhamsted where they celebrated Christmas.

For the first years of their married life, as Prince and Princess of Aquitaine, Joan and Edward lived in Aquitaine and Gascony, a peripatetic lifestyle as they travelled around the major towns and cities to make an impression on the local nobility, but mostly based in Bordeaux. It was not a happy time. The Aquitainian nobility were in opposition, stirred up by the King of France who had his own eye on Aquitaine. Edward’s campaign on behalf of Pedro of Castile achieved the great victory at Najera but drained their money. Their eldest son Edward of Angouleme died, and the Prince’s health also began to break down. Eventually they returned to England.

Prince Edward died in June 1376 after a long illness. King Edward III was also in severe decline, leaving Joan to consider the future of the next king, Richard II, who would inherit the throne as a mere child.

Joan was not appointed to the Royal Council and had no official status in the new reign but had considerable influence in the early years as King’s Mother. She was very supportive of Richard’s first marriage with Anne of Bohemia even though her father’s pro French policies were not at first acceptable to England."

Source:

https://www.anneobrienbooks.com/767-2/

#joan of kent#fair maiden of kent#perioddramaedit#history#edit#history edit#medieval#edward woodstock#the black prince#joan of kent and edward#alice perrers#edward iii#richard ii#anne o'brien#the shadow queen#middle ages#british history#a historic love#historical couple#edward x joan#santiago cabrera#abbie cornish

76 notes

·

View notes

Note

I know you’re Team Smallfolk so I wanted to ask about how peasants felt when they were under the rule of new liege lord’s and such. Like the Angevin Empire where England took over large swaths of France. Or the partitioning of Poland. Or Alsace-Lorraine after the Franco-Prussian War. How did these people feel? Were the happy or upset? Did they long for the old order?

That’s a very complicated question, because it really varied depending on the time, the background of individuals, the broader cultural and political environment, and so forth.

So to take one of your examples: the Angevin Empire isn’t exactly a case of England taking over large swathes of France, especially since most of the Angevin Kings of England didn’t speak English or spend time in England. It’s more accurate to say that the Angevins were French nobility whose landholdings included England. So would a peasant care? Probably not. (Especially because the nationalizing effects of the Hundred Years War had yet to take place, so that peasant would probably care more about their identity as a Gascon or an Aquitainian than as French or English.)

However, someone who was living during the partitioning of Poland might care quite a bit, depending on various factors - was their primary language Polish, German, Ruthenian/Ukrianian/Belarusian, Lithuanian, Hebrew, Yiddish, etc., were they Catholic or Orthodox or Lutheran or Calvinist or Jewish, etc. - and whether those factors lined up with the country they had been partitioned into or not. Likewise, someone living in Alsace-Lorraine between 1871-1920 would probably feel quite differently about it depending on whether they spoke French or German as a primary language.

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Other Princeps, Chap 37

Title: The Other Princeps

Fandom: Codex Alera

Characters: Aquitainus Attis, Amara, Antillus Raucus, Ensemble

Pairings: past!Attis/Invidia, slight past!Attis/Septimus, Attis/OCs

Word Count: 3,621

Rating: R

Summary: In which Attis’s confrontation with Invidia during the Battle of Riva goes better for him. AU. WIP.

Warnings: Massive spoilers for First Lord’s Fury.

Disclaimer: I do not own the Codex Alera. This is only for fun & no profit is being made from it.

Previous Chapters

Chapter 37: Aurelius

We remained in Rhodes for nearly two months in all. Much of that time was spent clearing Vord and croach out of the surrounding lands. After the first couple of weeks I split my time between the Legions and the city. Repairs were already well underway to the sections which had been damaged. I even spent some time assisting with the planting. Rhodes would be able to get one harvest in at least before winter. The rest of the province was another story—it was simply impossible to clear out every single path of croach before winter. We did what we could. Those whose lands were still covered in croach could eat the stuff to get through the winter. From what I heard it was absolutely disgusting, but it would do when nothing else was available.

Rhodes Tadius was duly sworn in as High Lord Rhodes, with me serving as an official witness. Witnessing a High Lord’s swearing in was interesting—I’d never been to one aside from my own. It was something of a relief to have a neighbor who wasn’t someone I despised. A few days after the ceremony, we left for Aquitaine. Winter was nearly upon us, meaning it wasn’t an ideal time for marching. Nonetheless the Legions were in high spirits, glad to be going home. The return journey was quicker than the trip to Rhodes had been, since we didn’t have to spend so much time clearing out Vord and croach. Along the way, the Second and Third left the main column to return to their usual winter quarters. The auxiliary Legions would be quartered in the city along with the First.

Crowds were present in the city to greet us, despite the chill in the air. I was so eager to get back to the palace that I hardly noticed them. Thyra, on the other hand, was enjoying the attention. I suppose it felt good after years of essentially being hidden away. I’d hardly set foot in the palace courtyard before we were greeted by Camilla, Phaidros, and Melitta. I barely had time to register how heavily pregnant she was before she pulled me into an embrace. “I’m so pleased you’ve returned safely, my love,” she breathed.

“I’m glad to be home,” I murmured, stroking her hair. “I told you I would be back in time for the birth.”

“The healers have told me our child is due any day now, so it seems you’re just in time.”

“Indeed. How have you been feeling, Camilla? I hope you are not in too much discomfort.”

“Well, I can’t say that I feel comfortable exactly, but it’s bearable. I am quite ready for it to be over,” she admitted. I detected a bit of excitement from her, which was to be expected. I felt the same way about the impending birth. Our child… what would it be like? To my surprise, I found myself not having a preference when it came to gender. The vast majority of Aleran lords would’ve wanted a son so they might have an heir. I myself needed a legitimate heir, but in truth daughters can legally inherit if there are no sons, so it really matters very little. Camilla, curiously, didn’t feel the same way and told me she very much hoped to give me a son and heir. The prospect of fatherhood wasn’t so intimidating now that I’d been a father for the last several months. I was ready now.

Once I was settled in, I sent for Ismene and Clio. They reacted much as Samarra had when I freed them. It wasn’t surprising—I knew both of them had been sold into slavery as young children and thus had no inclination to return to their families. Both made the same decision as Samarra and chose to remain with me as free concubines. I was quite pleased to hear it, as I would’ve been very disappointed to lose either of them.

My freeing of the dancing girls turned out to be just in time, for I’d scarcely been home a week before a courier came with a summons from the First Lord. He desired my presence in Riva, to address the Senate on the subject of the abolition of slavery. I immediately regretted offering to address the Senate if he asked it of me as I read the summons. How could I leave Aquitaine again, with Camilla due any day now? Given my regrets about not finding my bastards sooner, I was determined not to miss the birth. Camilla could hardly travel in her condition. But a summons from the First Lord could hardly be ignored.

Camilla was not pleased when I shared the news with her. “I will return as soon as this is done,” I assured her. “I cannot refuse an official summons of the First Lord.”

“If you must go, then you had better return swiftly,” she retorted, fixing me with a stern glare.

As I packed, it occurred to me that perhaps I ought to bring Samarra along. Who better to speak of the evils of slavery than a former slave? Odiana might’ve been a better example with a more tragic story, but she was not exactly of sound enough mind to address the Senate on her experiences. Having Samarra join me for my address, maybe even speak of her own experiences in Kalare, would surely add something of a personal touch to my speech. To see someone who’d been a slave and had worn a discipline collar might help move some of them to support abolition. They didn’t need to know that she’d been my slave as well until recently. When I mentioned the idea to her, she was quick to agree to it.

A short while later, Samarra and I boarded the windcoach together. I brought with me a sheaf of paper along with a quill and ink—there was no time like the present to begin writing my speech. Writing would be a pleasant distraction from my worry over Camilla, at least. It did not take long for the words to come. I’d always done quite well in Rhetoric class at the Academy and had addressed the Senate many times before. “My lo—Attis.” Samarra’s voice pulled me away from my writing. “What precisely do you want me to say?”

“Speak about your experiences,” I answered. “I won’t ask you to share the most painful parts, only enough for them to understand what it was like to be a Kalaran bed slave and wear a discipline collar.”

Samarra nodded. “I can do that. There’s not so much that’s too painful to speak of.”

It was not long before we arrived in Riva. Octavian was soon there to greet us. If he was surprised to see Samarra with me, he gave no sign. “How has the debate proceeded so far?” I inquired. Knowing what arguments had already been made would allow me to refine my speech.

“We are still at the beginning stages, but my mother has already addressed the Senate on her brief experience being enslaved.”

“And what has the response been?”

“Well, the people are in favor—the Vord War fostered a sense of solidarity that still remains. I can’t exactly say the same of the Senate. A number of Senators have already spoken out against it and I suspect a number of others are opposed as well,” Octavian explained.

“I wish I could say. I’m surprised, but I’m not. Aleran solidarity wouldn’t last long among a bunch of Senators who had money in the slave trade. We will have to do our best to win enough votes to our cause. I have brought someone to help convince them.” I gestured for Samarra to step forward. “This is my concubine Samarra, formerly a Kalaran bed slave. I thought she might share her experiences with the Senate.”

Octavian raised an eyebrow and for a moment I thought he would object before he said, “A good idea. Would you be ready to address the Senate tomorrow?”

“Yes. I already began writing my speech on the way here.”

It was immediately apparent that Riva was not the same city I’d left months ago. Repairs had been made to the areas most damaged in the battle, though it was still a long way from what it had been before the war. High Lord Riva and his architects would have no shortage of work, that was certain. It was not nearly as crowded as the last time I’d seen it either, with some of the refugees having left the city and the High Lords gone to liberate theirs.

Most of my time before the speech was spent revising my remarks, though I did take some time to inform the Aquitainian Senators that I supported abolition and I expected them to vote in favor of it. I wanted my speech to be the best it could be for a cause of such importance. When it was finally done to my satisfaction, I set it aside to wait until the time came. Normally I would’ve memorized it, but there wasn’t the time. It was no matter—I could deliver a speech just as well reading it as I could reciting it. I always scored well in Rhetoric.

When the day came, Samarra and I headed to the Senate chamber as soon as the session began. Both of us put in considerable effort to look our best—appearances were important for an occasion such as this. We wore red and black to represent Aquitaine, as it was traditional to wear your city’s colors when formally addressing the Senate. I accented it with my High Lord armbands and signet dagger, which hung in its sheath at my waist. We waited in my box until it was our turn to speak.

“Nervous?” I asked Samarra as we watched the Speaker of the Senate open the session.

“I’ve never attended anything like this before,” Samarra replied. “I would be lying it if I said I wasn’t nervous.”

I laid a hand over hers. “It’s all right. It’s not hard to ignore the crowd once you’re at the podium. They begin to blur together into one mass. One thing that helps is to choose a spot in the back of the room and keep your eyes on it. Don’t look at the crowd at all.”

“I will try my best to do so.”

“Very good. I’ll give you some calming to help settle your nerves in the meantime.” I reached out with my earthcrafting and soothed her nerves. When it was done, I felt her hand relax beneath mine.

We did not have to wait long before the Speaker called me to the podium. I descended from the box, Samarra following closely behind me. When I reached the podium, the Speaker stepped aside so I could take his place. Samarra stood several paces behind me. I laid my speech on the podium and began.

“Honored Senators, I come before you to speak on an institution which has been a plague on this land for many years: slavery.” My wind furies carried my voice to every corner of the chamber. “We need only to look to the recent wars to see the proof of this. Our own cruelties were turned against us by our enemies. When an evil in our society can be so easily be exploited, there is no sense in allowing such an evil to continue.”

I will not record my entire speech here—it is in the official senatorial record for those who wish to read it. Suffice it to say I continued in that vein for a while, detailing the many ways that slavery was a plague on Alera as well as incredibly cruel. When I finished describing the horrors inflicted by Kalarus on his slaves, I beckoned Samarra forward. “My own concubine Samarra, once a Kalaran bed slave, will share her experiences with you.” I stepped back from the podium and patted her on the shoulder for encouragement.

“Honored Senators,” she began, “my name is Samarra and until recently I was a bed slave belonging to a Kalaran nobleman. High Lord Aquitaine has asked me to share my experiences with you. I was sold into slavery as a very young child, to a slaver who specialized in training bed slaves. There were several other girls in the household as well, some of them collared. They didn’t collar every slave, only those who were disobedient.

“I was thirteen when I was first sold as a bed slave. My new master put discipline collars on all of his slaves as a matter of course. I was collared right after I arrived in his household.” She paused to take a deep breath before continuing. I reached out with a tendril of earthcrafting to calm her. “When a discipline collar is put on you, you feel nothing. But when you obey your master’s orders, the pleasure you feel is like no other pleasure in this world. I was fortunate in that I was not collared for very long. My master thought I was sufficiently docile and obedient and therefore I didn’t need to be collared for an extended period of time. The others, though, they were collared for long enough that they became totally addicted to the feeling. Their eyes all went vacant after a while. All of the other bed slaves had that same look. I was my master’s favorite for a while, but sometimes he wanted two of us. The dead look remained in the other bed slaves’ eyes, even when he bedded them. There simply… wasn’t anything there. They felt the pleasure from obeying his orders, but nothing else. The collars had made them into mindless shells.

“That is my experience with what discipline collars do. My master’s collars paled beside those made by the late High Lord Kalarus. You need only look to his Immortals to see what he was capable of doing with discipline collars. It is time these abuses were ended.” With that, Samarra stepped back from the podium. For someone with no formal rhetorical training, she had done well.

“There you have it. Slavery is a weakness our enemies were able to exploit to great effect, but more importantly it is a moral outrage. Countless brutalities and cruelties have been exhibited upon Aleran slaves, much like what our nation has suffered from the Vord. Are we not one people?” My eyes flicked up to the First Lord’s box, where Octavian sat with Isana by his side. “And if we are one people, how can we allow our fellow Alerans to be treated so cruelly? The First Lord intends to build a new Alera. Let us leave slavery where it belongs—in the old Alera.”

Applause broke out in the chamber as I stepped away from the podium. Relaxing my shields a little so I might sense the mood of the audience, I noticed my words and Samarra’s story had moved them somewhat. “Well done,” said Octavian once the session had concluded. “The plan is to have the Senate vote on this within the week. If we’re lucky, playing on their consciences just enough might overcome their financial interests.”

“Let’s hope their feelings of Aleran solidarity haven’t entirely faded,” I replied. “Would you have me remain here for the final vote? I have already instructed the Aquitainian Senators to vote in favor of abolition.”

“No, that won’t be necessary. I understand there are… other matters occupying your mind at the moment,” said Octavian.

“Much appreciated, sire.”

That evening, I dined with Octavian and First Lady Kitai. I was momentarily taken aback by how heavily pregnant she was. So much had happened since I liberated Aquitaine that I’d nearly forgotten about her pregnancy. I didn’t know if these matters differed at all for Marat, but she was likely near her time. With a start I realized Octavian’s child would be very close in age to my own. Our conversation over the meal was quite informative, as Octavian took it upon himself to fill me in on what had been going on in the rest of the Realm. The process of liberation continued, though it would slow down considerably once winter set in. Food was a major concern now, though the liberated areas had been hard at work producing as much as they could. The meal was nearly over when we were interrupted by the sudden appearance of one of my own household Knights Aeris. His face was red and it took him a moment to catch his breath before he spoke. He saluted, then turned to Octavian. “Apologies for interrupting, sire. I have an urgent message for Lord Aquitaine.”

“What is it?” I inquired, my heart beating faster. I had a good idea what the urgent message was.

“It’s the Lady Camilla, my lord. She has gone into labor.”

I all but leapt out of my chair at the news. “When?”

“It began this afternoon. She sent me here to tell you the news as soon as it began.”

I glanced over at Octavian, who smiled. “Go to her, Lord Aquitaine.”

After he dismissed me, I wasted no time donning my flying leathers. “I must return to Aquitaine immediately,” I informed Samarra. “Take the windcoach back.”

“Give my regards to Camilla,” she said as I took my leave of her.

**

The stars were shining brightly in the night sky when I arrived home. Thyra and Eolus were waiting at the doors for me.

“What’s happening? Has she given birth?”

“Last I knew, she was still in labor,” said Thyra. “We came out here to wait for you.”

“The wait’s over; I’m here. Lead me to her.” Thyra nodded and I followed her and Eolus inside.

“How was it proceeding last you knew?”

“From what the healers and midwife said, things were proceeding as normal,” Thyra assured me.

“It will be fine, Attis. Camilla has the best midwife and healers in the city attending her,” Eolus added, sensing my anxiety. I hadn’t bothered hiding it behind my shields.

I waved a hand. “Of course. It’s only that this is the first time I’ve gone through this, so you’ll have to forgive me for being a bit anxious.”

When we arrived at Camilla’s chambers, a small crowd of family members had already gathered in her solar. I paused only to greet Phaidros and Melitta before making for the door to her bedchamber. The doors opened and Sabina gave a surprised gasp when she saw me there. “Attis, you’re just in time! The child has been born!”

Waves of relief and elation washed over me. “And Camilla?”

“Perfectly fine, though exhausted from giving birth. Come in and see.”

I followed Sabina inside and made straight for the bed. Camilla lay propped up on the pillows, our child resting in her arms. “Attis,” she breathed, “you’ve returned.”

The midwife and healers who were clustered around her bed moved aside and I seated myself on the mattress. Camilla’s face was pale and weary, yet her eyes were bright. “We have a son.”

My mouth broke into a wide grin and I let out a cry of joy. I had a son, one who would be legitimate once Camilla and I wed. She held him out to me and I gingerly took him into my arms. He was a red, wrinkled thing, gazing at me with clever, curious eyes. I’d never bothered to sense the emotions of an infant before, but a wave of simple contentment hit me from him. “Hello,” I said softly, “I’m your father. I’ve been greatly looking forward to meeting you.”

The three of us remained like that for several minutes before the doors burst open and the crowd who’d been waiting in Camilla’s solar rushed in. Thyra, Phaidros, and Melitta were the first through the doors and made straight for the bed.

“Children,” I began, “this is your new brother.”

They gathered around me, gaping at the child in my arms. “He’s so small!” Melitta exclaimed.

“You were surely so small, once,” said Camilla.

“I was hoping for another boy!” Phaidros remarked, grinning. “What’s his name?”

“We haven’t decided yet,” I replied. “You’ve got another younger sibling to look after. That’s an important responsibility.” I did not think there would be any animosity between my illegitimate children and my legitimate child, but I still wanted to emphasize that we were all one family.

“Of course!” said Phaidros. “It’ll be just like being a big brother to Melitta. I can’t wait to teach him some crafting!”

Thyra leaned forward to look at her new brother, studying him intently. “He has your eyes, Father.”

“Yes, he does.”

The rest of my and Camilla’s families had by now gathered around the bed, all eager for a look at the baby. They each took their turn and offered us their congratulations. After a while the baby began to fuss and I could sense Camilla’s growing weariness. Slowly they trickled out until Camilla and I were left alone.

“You are sorely in need of rest, my dear,” I said, pushing a lock of hair away from her face.

“Yes.” Our son was now sleeping in her arms. “But our son needs a name.”

We’d hardly discussed names at all previously, only whether we wanted a son or a daughter. “Well, we could go the more traditional route and name him Marius after my father, but… I rather like the name Aurelius. Aquitainus Aurelius flows nicely, don’t you think?”

“Aurelius,” she said as if she were tasting the name. “A good name. Aquitainus Aurelius.”

0 notes

Text

“Fontevraud was founded by Robert of Arbrissel, a hermit whose charismatic preaching attracted a following of mostly women of all social classes, including members of the high nobility as well as prostitutes and beggars, and which, in about 1100, he was required to regularize. The community at Fontevraud became the special concern of the counts of Anjou, and the community remembered not only Robert as its founder, but them also. The structure of the monastic community was distinct. It was a mixed house with both men and women living in it, but was unique in that the women were dominant. The men were not monks but canons regular who laboured on the nuns’ estates and acted as their chaplains, in order that the nuns might enjoy the rituals of the monastic life. The men lived in one part of the monastery, while the women lived in several cloisters, separated by function and by class. It was the aristocratic women who ruled. When it came to the decision-making process, in the world of Fontevraud, it was class that mattered, not gender. The community followed the Rule of St Benedict, and by the time that John is said to have been a member of the community, it was still being strictly observed. No other monastic community, whether long established or part of the new movements in monasticism of the twelfth century, had a structure in which religious women governed religious men. Like other orders that succeeded in the twelfth century, Fontevraud attracted imitators, and thus became the mother house of a large number of dependent communities, including, after the accession of Henry II, three in England. The community had a special place in the hearts of the Angevins, and under Henry II Fontevraud took on the character of a royal mausoleum. It was here that Henry was to be buried, to be followed by his son, Richard the Lionheart, his daughter, Joanna, queen of Sicily, and his wife, Eleanor of Aquitaine – her grandfather had had a hand in supporting the founder of Fontevraud, so the community had Aquitainian connections that satisfied Eleanor. John, in the company of his sister, Joanna, had therefore been placed in a matriarchy for the purposes of learning his letters.10 Quite when he entered Fontevraud is difficult to say. He certainly could not have been there in his teenage years (nuns did not teach teenage boys), and it is unlikely that John had been placed in the community as an infant (nuns were not in the habit of wet-nursing babies). In 1170, aged three, John had been handed over to the care of his eldest brother, the Young King, for him to promote and support, so we can suppose that John was not at Fontevraud until after that time. John emerges from the records as an individual in about the year 1177, so the simple deduction has to be that John’s time at Fontevraud occurred between 1172 and and 1177. But it would be wrong to see this period in John’s life as one during which he was abandoned. On the contrary, he was at the spiritual home of the Angevin dynasty, nurtured by women who would have been friends and relations of his own family. There were few better locations for a boy to learn the basics of his literate education even if it was an unsuitable place for a boy to learn how to fight.