#and Marius in Bonapartism!

Text

Hot take: by the time Hugo picked Les Mis back up in 1860 to finish it, I don't think he intended for Marius and Cosette's marriage to be a good or happy one.

#I just got home after being out of my house nearly fourteen hours#and it is past my bedtime with a very early start intended for tomorrow#but the gist of the argument is that Fantine was the best of us — the French empire under Bonaparte!#and Cosette as Hugo was writing her in 1848 was intended to be the extension of that progress!#and Marius in Bonapartism!#(and then you have the amis who are different levels of supporters of Robespierre and Babeuf and maybe even Lafayette a little)#different political philosophies and directions of taking France#and by 1860 when Hugo was picking up at Blotter Talks#he was fully aware that Actually returning to the Bonaparte line kinda sucked and so did that dick NIII#who forced Hugo to flee to England where he had to (gasp) listen to people speak God's imperfect middle child language English#and he was like ''actually Cosette marrying Marius isn't all it's cracked up to be#idk I'm probably missing a ton of crucial context and background that will easily swat down this theory#but as of 21.45 18 Oct 2022 GMT+8 or whatever that is my take#PLEASE feel free to provide more info#les mis#shitposting @ me#marius#marisette#cosette

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

He has a ouchie :[[

#LISTEN…..#napoleon bonaparte#jean lannes#napoleonic wars#I have nothing to say 😇🙏#posts that Marius Pontmercy would reblog#also this literally happened so trust I’m not being delusional#blood

68 notes

·

View notes

Text

For The Literal Love Of My Life and overlord of the Empereur's Mercy corner of this cursed site, @shitpostingfromthebarricade

Four years of knowing you, and what a delight it has been <3

#i am almost certain this set up must exist but this one is special because its for my beloved#Happy Anniversary Boo!#Marius Pontmercy#Empereurs Mercy#Napoleon Bonaparte#Les Memerables#Les Mis#Problematic Marius#Cait Makes

317 notes

·

View notes

Text

The way I'm currently on Corsica, have been to the city Napoleon was born and will be on Elba in a week. I'm literally living Marius's dream.

#yet all that's going on in my brain is “Être libre dit Combeferre”#and “Citizen my mother is the republic”#les mis#river rants#les miserables#les misérables#marius pontmercy#combeferre#enjolras#marius pontmercy napoleon#napoleon bonaparte#corisca#elba

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

At The Emperor's Mercy

(yes this just happened don't think too hard about it)

there's an extra jumbo cursed explicit version on my deviantart that I cannot in good conscience post here, that I made cause I had finished this and figured, since I'm already here... you do have to have an account to see it tho. I can't just let anybody view this cursed object

#emperor's mercy week#marius#marius pontmercy#les mis#les miserables#extremely cursed#napoleon bonaparte#fave arts#2022#my art

141 notes

·

View notes

Text

So I had a nightmare that the Mob Psycho finale was just Garou ripping out Genos' core again. I threw a plant at the television and promised only to write RPF about UN delegates from now on.

...my subconscious is a really scary place sometimes.

#first of all they're not even *in* that show#second of all i've never even considered writing RFP#except for maybe Marius Pontmercy x Napoleon Bonaparte (but it's been done)#or Robespierre x Reader but like#strictly for the lulz

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Saint-Just/Enjolras (don’t look at me)

I manifested this earlier, and the supreme being did give me some abilities to draw, and so I put pen to paper and thus this was born

It’s 12am here and I don’t have an eraser nor the will to make this actually good

Here’s the significantly better and cuter work I did for empereur’s mercy. I refuse to draw Bonaparte well out of spite

#little rambles#empereur’s mercy#enjolras#antoine saint just#marius pontmercy#napoleon bonaparte#those sure are a set of tags#whatever cursed energy overtook me this late night better leave me in the morning#honestly I have worse/more cursed ships in my mind but those are dying with me#actually.#momo don’t look#my other friends who follow me can suffer this though

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

I know we (rightfully) clown on Marius for his Bonapartism and the to be free debacle, but at least he stopped his yapping.

A few weeks ago in my class on Reformation and reformations, which is fantastic except for that it contains one specific individual, I got into an argument with said individual.

He's a Bonapartist (among other things) and he wouldn't kriffing. shut up. about how Napoleon was the most moral and did so many great things and how he didn't know how anyone could dislike him. It could have been my to be free moment if he had a grain more sense in his head, but alas.

#lm#marius pontmercy#napoleon bonaparte#to be clear I don't think it's academically helpful to impose modern morality on historical figures in order to determine their “goodness”#but. I find him odious#<- talking about Napoleon or my classmate? You decide!#Frankie.txt

1 note

·

View note

Text

Les Mis French History Timeline: all the context you need to know to understand Les Mis

Here is a simple timeline of French history as it relates to events in Les Miserables, and to the context of Les Mis's publication!

A post like this would’ve really helped me four years ago, when I knew very little about 1830s France or the goals of Les Amis, so I’m making it now that I have the information to share! ^_^

This post will be split into 4 sections: a quick overview of important terms, the history before the novel that’s important to the character's backstories, the history during the novel, and then the history relevant to the 1848-onward circumstances of Hugo’s life and the novel’s publication.

Part 1: Overview

The novel takes place in the aftermath of the Battle of Waterloo, during a period called the Restoration.

The ancient monarchy was overthrown during the French Revolution. After a series of political struggles the revolutionary government was eventually replaced by an empire under Napoleon. Then Napoleon was defeated and sent into exile— but then he briefly came back and seized power for one hundred days—! and then he was defeated yet again for good at the battle of Waterloo in 1815.

After all that political turmoil, kings have been "restored" to the throne of France. The novel begins right as this Restoration begins.

The major political parties important to generally understanding Les Mis (Wildly Oversimplified) are Republicans, Liberals, Bonapartists, and Royalists. It’s worth noting that all these ‘party terms’ changed in meaning/goals over time depending on which type of government was in power. In general though, and just for the sake of reading Les Mis:

Republicans want a Republic, where people elect their leaders democratically— they’re the very left wing progressive ones, and are heavily outcast/censored/policed. Les Amis are Republicans.

Liberals are (iirc) actually the most powerful “leftist” group at the time; they generally want limits on monarchical power but don’t go as far as Republicans.

Bonapartists are followers of Napoleon Bonaparte I, who led the Empire. Many viewed the Emperor as more favorable or progressive to them than a king would be. Georges Pontmercy is a Bonapartist, as is Pere Fauchelevent.

Royalists believe in the divine right of Kings; they’re conservative. Someone who is extremely royalist to the point of wanting basically no limits on the king’s power at all are called “Ultraroyalists” or “ultra.” Marius’s conservative grandfather Gillenromand is an ultra royalist.

Hugo is also very concerned with criticizing the "Great Man of History," the view that history is pushed forward by the actions of a handful of special great men like kings and emperors. Les Mis aims to focus on the common masses of people who push history forward instead.

Part 2: Timeline of History involved in characters’ Backstories

1789– the March on the bastille/ the beginning of the original French Revolution. A young Myriel, who is then a shallow married aristocrat, flees the country. His family is badly hurt by the Revolution. His wife dies in exile.

1793– Louis XVI is found guilty of committing treason and sentenced to death. The Conventionist G—, the old revolutionary who Myriel talks to, votes against the death of the king.

1795: the Directory rules France. Throughout much of the revolution, including this period, the country is undergoing “dechristianization” policies. Fantine is born at this time. Because the church is not in power as a result of dechristianization, Fantine is unbaptized and has no record of a legal given name.

1795: The Revolutionary government becomes more conservative. Jean Valjean is arrested.

1804: Napoleon officially crowns himself Emperor of France. the Revolution’s dream of a Republic is dead for a bit. At this time, Myriel returns from his exile and settles down in the provinces of France to work as a humble priest. Then he visits Paris and makes a snarky comment to Napoleon, and Napoleon finds him so witty that he appoints him Bishop.

Part 3: the novel actually begins

1815: Napoleon is defeated at the Battle of Waterloo by the allied nations of Britain and Prussia. Read Hugo’s take on that in the Waterloo Digression! He gets a lot of facts wrong, but that’s Hugo for you.

Marius’s father, Baron Pontmercy, nearly dies on the battlefield. Thenardier steals his belongings.

After Napoleon is defeated, a king is restored to the throne— Louis XVIII, of the House of Bourbon, the ancient royal house that ruled France before the Revolution. In order to ensure that Louis XVIII stays on the throne, the nations of Britian, Prussia, and Russia, send soldiers occupy France. So France is, during the early events of the novel, being occupied by foreign soldiers. This is part of why there are so many references to soldiers on the streets and garrisons and barracks throughout the early portions of the novel. The occupation officially ended in 1818.

1815 (a few months later): Jean Valjean is released from prison and walks down the road to Digne, the very same road Napoleon charged down during his last attempt to seize power. Many of the inns he passes by are run by people advertising their connections to Napoleon. Symbolically Valjean is the poor man returning from exile into France, just as Napoleon was the Great Man briefly returning from exile during the 100 days, or King Louis XVIII is the Great King returning from exile to a restored throne.

1817: The Year 1817, which Hugo has a whole chapter-digression about. Louis XVIII of the House of Bourbon is on the throne. Fantine, “the nameless child of the Directory,” is abandoned by Tholomyes.

1821: Napoleon dies in exile.

1825: King Louis XVIII dies. Charles X takes the throne. While Louis XVIII was willing to compromise, Charles X is a far more conservative ultra-royalist. He attempts to bring back the Pre-Revolution style of monarchy.

Underground resistance groups, including Republican groups like Les Amis, plot against him.

1827-1828: Georges Pontmercy, bonapartist veteran of Waterloo, dies. Marius, who has been growing up with his abusive Ultra-royalist grandfather and mindlessly repeating his ultra-royalist politics, learns how much his father loved him. He becomes a democratic Bonapartist.

Marius is a little bit late to everything though. He shouts “long live the Emperor!” Even though Napoleon died in 1821 and insults his grandfather by telling him “down with that hog Louis XVIII” even though Louis XVIII has been dead since 1825. He’s a little confused but he’s got the spirit.

Marius leaves his grandfather to live on his own.

1830: “The July Revolution,” also known as the “Three Glorious Days” or “the Second French Revolution.” Rebels built barricades and successfully forced Charles X out of power.

Unfortunately, TL;DR moderate politicians prevented the creation of a Republic and instead installed another more politically progressive king — Louis-Philippe, of the house of Orleans.

Louis-Philippe was a relative of the royal family, had lived in poverty for a time, and described himself as “the citizen-king.” Hugo’s take on him is that he was a good man, but being a king is inherently evil; monarchy is a bad system even if a “good” dictator is on the throne.

The shadow of 1830 is important to Les Mis, and there’s even a whole digression about it in “A Few Pages of History,” a digression most people adapting the novel have clearly skipped. Les Amis would’ve probably been involved in it....though interestingly, only Gavroche and maybe Enjolras are explicitly confirmed to have been there, Gavroche telling Enjolras he participated “when we had that dispute with Charles X.”

Sadly we're following Marius (not Les Amis) in 1830. Hugo mentions that Marius is always too busy thinking to actually participate in political movements. He notes that Marius was pleased by 1830 because he thinks it is a sign of progress, but that he was too dreamy to be involved in it.

1831: in “A Few Pages of History” Hugo describes the various ways Republican groups were plotting what what would later become the June Rebellion– the way resistance groups had underground meetings, spread propaganda with pamphlets, smuggled in gunpowder, etc.

Spring of 1832: there is a massive pandemic of cholera in Paris that exacerbates existing tensions. Marius is described as too distracted by love to notice all the people dying of cholera.

June 1st, 1832: General Lamarque, a member of parliament often critical of the monarchy, dies of cholera.

June 5th and 6th, 1832: the June Rebellion of 1832:

Republicans, students, and workers attempt to overthrow the monarchy, and finally get a democratic Republic For Real This Time. The rebellion is violently crushed by the National Guard.

Enjolras was partially inspired by Charles Jeanne, who led the barricades at Saint-Merry.

Part 4: the context of Les Mis’s publication

February 1848: a successful revolution finally overthrows King Louis Philippe. A younger Victor Hugo, who was appointed a peer of France by Louis-Philippe, is then elected as a representative of Paris in the provisional revolutionary government.

June 1848: This is a lot, and it’s a thing even Hugo’s biographers often gloss over, because it’s a horrific moral failure/complexity of Hugo’s that is completely at odds with the sort of politics he later became known for. The short summary is that in June 1848 there was a working-class rebellion against new unjust labor laws/forced conscription, and Victor Hugo was on the “wrong side of the barricades” working with the government to violently suppress the rebels. To quote from this source:

Much to the disappointment of his supporters, in [Victor Hugo’s] first speech in the national assembly he went after the ateliers or national workshops, which had been a major demand of the workers. Two days later the workshops were closed, workers under twenty-five were conscripted and the rest sent to the countryside. It was a “political purge” and a declaration of war on the Parisian working class that set into motion the June Days, or the second revolution of 1848—an uprising lauded by Marx as one of the first workers’ revolutions. As the barricades went up in Paris, Hugo was tragically on the wrong side. On June 24 the national assembly declared a state of siege with Hugo’s support.

Hugo would then sink to a new political low. He was chosen as one of sixty representatives “to go and inform the insurgents that a state of siege existed and that Cavaignac [the officer who had led the suppression of the June revolt] was in control.” With an express mission “to stop the spilling of blood,” Hugo took up arms against the workers of Paris. Thus, Hugo, voice of the voiceless and hero of workers, helped to violently suppress a rebellion led by people whom he in many ways supported—and many of whom supported him. With twisted logic and an even more twisted conscience, Hugo fought and risked his life to crush the June insurrection.

There is an otherwise baffling chapter in Les Mis titled "The Charybdis of the Faubourg Saint Antoine and the Scylla of the Fauborg Du Temple," where Hugo goes on a digression about June of 1848. Hugo contrasts June of 1848 with other rebellions, and insists that the June 1848 Rebellion was Wrong and Different. It is a strangely anti-rebellion classist chapter that feels discordant with the rest of the book. This is because it is Hugo's effort to (indirectly) address criticisms people had of his own involvement in June 1848, and to justify why he believed crushing that rebellion with so much force was necessary. The chapter is often misused to say that Hugo was "anti-violent-rebellion all the time" (which he wasn't) or that "rebellion is bad” is the message of Les Mis (which it isn't) ........but in reality the chapter is about Hugo attempting to justify his own past actions to the reader and to himself, actions which many people on his side of the political spectrum considered a horrible betrayal. He couldn't really have written a novel about the politics of barricades without addressing his actions in June 1848, and he addressed them by attempting to justify them, and he attempted to justify them with a lot of deeply questionable rhetoric.

1848 is a lot, and I don't fully understand all the context yet-- but that general context is necessary to understand why the chapter is even in the novel.

Late 1848/1849:

Quoting from the earlier source again:

In the wake of the revolution, Hugo tried to make sense of the events of 1848. He tried to straddle the growing polarization between, on the one hand, “the party of order,” which coalesced around Napoleon’s nephew Louis-Napoleon Bonaparte, who in December 1848 had been elected France’s president under a new constitution, and the “party of movement” (or radical Left) that, in the aftermath of 1848, had made considerable advances. In this climate, as Hugo increasingly spoke out, and faced opposition and repression himself, he was radicalized and turned to the Left for support against the tyranny and “barbarism” he saw in the government of Louis Napoleon.

The “point of no return” came in 1849. Hugo became one of the loudest and most prominent voices of opposition to Louis Napoleon. In his final and most famous insult to Napoleon, he asked: “Just because we had Napoleon le Grand [Napoleon the Great], do we have to have Napoleon le petit [Napoleon the small]?” Immune from punishment because of his role in the government, Bonaparte retaliated by shutting down Hugo’s newspaper and arresting both his sons.

Thenardier is likely meant to be Hugo’s caricature of Louis-Napoleon/Napoleon III. He is “Napoleon the small,” an opportunistic scumbag leeching off the legacy of Waterloo and Napoleon to give himself some respectability. He is a metaphorical ‘graverobber of Waterloo’ who has all of Napoleon’s dictatorial pettiness without any of his redeeming qualities.

It’s also worth noting that Marius is Victor “Marie” Hugo’s self-insert. Hugo’s politics changed wildly over time. Like Marius he was a royalist when was young. And like Marius, he looked up to Napoleon and to Napoleon III, before his views of them were shattered. This is reflected in the way Marius had complicated feelings of loyalty to his father (who’s very connected to the original Napoleon I) and to Thenardier (who’s arguably an analogue for Napoleon IiI.)

1851:

On December 2, 1851, Louis Napoleon launched his coup, suspending the republic’s constitution he had sworn to uphold. The National Assembly was occupied by troops. Hugo responded by trying to rally people to the barricades to defend Paris against Napoleon’s seizure of power. Protesters were met with brutal repression.

Under increasing threat to his own life, with both of his sons in jail and his death falsely announced, Hugo finally left Paris.

He ultimately ended up on the island of Guernsey where he spent much of the next eighteen years and where he would write the bulk of Les Misérables. It was from here that his most radical and political work was smuggled into France.

Hugo arguably did his most important political work after being exiled. In Guernsey, he aided with resistance against the regime of Napoleon III. Hugo’s popularity with the masses also meant that his exile was massive news, and a thing all readers of Les Miserables would’ve been deeply familiar with.

This is why there are so many bits of Les Mis where the narrator nostalgically reflects on how much they wish they were in Paris again —these parts are very political; readers would’ve picked up that this was Victor Hugo reflecting on he cruelty of his own exile.

1862-1863: Les Mis is published. It is a barely-veiled call to action against the government of Napoleon III, written about the June Rebellion instead of the current regime partially in order to dodge the censorship laws at the time.

Conservatives despise the book and call it the death of civilization and a dangerous rebellious evil godless text that encourages them to feel bad for the stupid evil criminal rebel poors and etc etc etc– (see @psalm22-6 ‘s excellent translations of the ancient conservative reviews)-- but the novel sells very well. Expressing approval or disapproval of the book is considered inherently political, but fortunately it remains unbanned.

…And that’s it! An ocean of basic historical context about Les Mis!

If anyone has any corrections or additions they would like to make, feel free to add them! I have researched to the best of my ability, but I don’t pretend to be perfect.

I also recommend listening to the Siecle podcast, which covers the events of the Bourbon Restoration starting at the Battle of Waterloo, if you're interested in learning more about the period!

#les mis#someone in a discord server asked about this a while back#so i put it together!#it’s basically what I told them in the discord server but as a tumblr post#and with some extra stuff I forgot to say#but yeAH maybe if more historical information gets spread#we’ll get more canon era fanfics >:3333#which are always fun

440 notes

·

View notes

Text

Oh, so this is the chapter with Javert’s leather stock askew! I had a false memory that it happened in his “punish me, Monsieur le Maire” episode and was surprised not to find it there. It means that he came to Monsieur le Maire’s office unshaken and balanced, Inspector at his best. However, the mere possibility that he could have nearly missed Jean Valjean profoundly stressed him.

In this chapter, Hugo attributes some of the most unforgettable characteristics to Javert. “Javert was a complete character, who never had a wrinkle in his duty or in his uniform; methodical with malefactors, rigid with the buttons of his coat.” And his belief system and all the things he is forever associated with are also here:

he, Javert, personified justice, light, and truth in their celestial function of crushing out evil. Behind him and around him, at an infinite distance, he had authority, reason, the case judged, the legal conscience, the public prosecution, all the stars; he was protecting order, he was causing the law to yield up its thunders, he was avenging society, he was lending a helping hand to the absolute, he was standing erect in the midst of a glory.

So, he is “avenging society” – the same society, most of us agree, is the main villain and culprit of “Les Misérables.” That’s very telling. Javert is triumphant, satisfied, “erect, haughty, brilliant,” but also very wrong.

I have just noticed that he is simultaneously likened to a demon and to the “monstrous Saint Michael” – while one is supposed to fight the other.

Javert is not the only intriguing figure in this chapter. How do you like the moment when the royalist court president was shocked to hear how Valjean said “the Emperor, not Bonaparte”? Valjean has pro-Napoleonic sympathies. That’s amusing, for it makes him akin to Marius in this respect.

My hero here is the counsel for the defence: this man really does his job well and effectively defends poor Champmathieu, despite the fact that the defendant is an obscure labourer. It seems to me that such counsels for the defence are the only positive aspects of the whole legal system of the early nineteenth century.

34 notes

·

View notes

Text

i really love the idea of eponine and combeferre being friends like eponine is just sobbing over marius and combeferre is standing on a table just like EPONINE HE LIKES BONAPARTE WAKE UP EPONINE HES NOT EVEN CUTE HE JUST HAS FRECKLES PLEASE its very pleasing to me

433 notes

·

View notes

Text

Things Tumblr Blaze has taught me, a saga:

Napoleon Bonaparte is frequently referenced in the original text of Les Mis.

Victor Hugo wrote 19 chapters dedicated to the battle of waterloo alone in Les Mis

A not insignificant (at least one person) portion of the les mis fandom ships Napoleon with Marius.

Yes, Marius, who, unlike Napoleon, was very much never a real person.

A post surrounding the ship was sponsored on tumblr-

-To be seen by 50k people.

At No Point did I uncover ANY interaction between Marius and Napoleon????

Probably because Napoleon is dead during the story.

There is actually internet discourse surrounding this ship (?) from a book published in 1862.

This is because in the story Napoleon died when Marius was 11. So fair?

I have been pissing myself at this image for the past ten minutes

#tumblr things#ether speaks#tumblr blaze#tumblr#les mis#PLEASE TELL ME OTHER PEOPLE HAVE SEEN THIS RIGHT

718 notes

·

View notes

Text

They’re here at last!!!

I love all of Les Amis, but their introductory paragraphs have also been pretty thoroughly analyzed - @everyonewasabird and @fremedon have pretty comprehensive posts on them from previous Brickclubs. Rather than go through them individually, then, I’ll try to point out some general trends that would be relevant to Marius (given that we meet them as soon as he’s kicked out of his house, we can assume there’s a connection):

The first major issue is the legacy of the French Revolution (1789) and the Terror (1793). All of the characters we meet here (with the exception of Grantaire) are attached to the legacy of the former, but they’re divided over the latter. Enjolras, for instance, is compared to Saint-Just – a more radical figure from that time period – and with his “warlike nature” and link to the “revolutionary apocalypse,” he’s definitely more in the tradition of ‘93 than ‘89, even if he’s attached to both. Combeferre, on the other hand, fears that kind of violence, only finding it acceptable if the only alternative is for things to stay the same. Like Marius’ newfound Bonapartism, all of their ideas come out of the clash and evolution of thought after the Revolution and the French Empire under Napoleon, placing each Ami in a similar position to him as they work out their ideas. All of them, though, came to a different conclusion than Marius, prioritizing the Republic over the Empire. At the same time, they’re all distinct from each other, too, revealing the diversity in French republican thought. With his limited exposure to political ideas outside of royalism (and now, idolization of Napoleon), the myriad veins of republicanism that the Amis offer broaden up the political sphere of the novel significantly.

On top of that, they’re a group; they can learn from each other in a way that Marius hasn’t had a chance to. Even Grantaire, who claims to not believe in anything, has friends, and while he distances himself from specific ideologies, his jokes illustrate that he’s familiar with them (for example: “He sneered at all devotion in all parties, the father as well as the brother, Robespierre junior as well as Loizerolles”). Marius doesn’t have friends or people to really work through ideas with. Oddly enough, the most similar structure to this that we’ve seen so far is the royalist salon. The key difference (aside from the obvious) is the chance to learn from different perspectives, whether that’s based on variations in republicanism, in priorities (conflict vs education, the local vs the international), or both. They’re not even all defined by their politics. Courfeyrac (who easily has the most insulting character introduction in the book) is defined by his character and personality first, with his political ideas mainly being a given from his participation in this group. These variations in emphasis, then, not only show us the diversity of their views, but the varying intensities with which they hold them (as in, you could talk to Courfeyrac about something that isn’t political, but you couldn’t do that with Enjolras) and how they’re kept together in spite of their disagreements (a common goal – a Republic – and many fun and socially savvy members). All of these factors serve to give a sense of liveliness as well, contrasting sharply with the “phantoms” of the royalist salon.

Les Amis aren’t very diverse class-wise, but they’re still better than the salon. Bahorel and Feuilly, at least, aren’t bourgeois or aristocrats.

Feuilly also brings us to the international level, far beyond Marius’ early attempts at imagining himself as part of a country. Focusing on the partition of Poland in particular, Feuilly advocates for national self-determination in all lands under imperial rule. The idea that a people should govern themselves was key to republican thought more broadly in that time (nationalism really took shape in the 18th-19th centuries), but to Feuilly, this isn’t just an issue of nationalism, but of tyranny:

“There has not been a despot, nor a traitor for nearly a century back, who has not signed, approved, counter-signed, and copied, ne variatur, the partition of Poland.”

The word “despot” ties this back to France in a way, with his rejection of despotism as it affects Poland possibly implying a similar anger at the same phenomenon in France. The Bourbons at the Congress of Vienna in 1815 were, after all, the same Bourbons who ruled during the Restoration.

A quick note on Lesgle: I didn’t get the joke around “Bossuet” the first time I read this book. Then, I had to take a class on the French monarchy, and I was assigned a text by Bossuet of Meaux, court preacher to Louis XIV and fierce proponent of absolutism. His name seemed familiar, but it took me a while to think to check Les Mis? And now I think calling Lesgle Bossuet because he’s Lesgle (like l’aigle=eagle) of Meaux is one of the funniest jokes in this book.

#Les mis letters#lm 3.4.1#les amis de l'abc#enjolras#combeferre#courfeyrac#feuilly#grantaire#Bahorel#Lesgle#bossuet#this ended up being much less organized than I’d hoped#But that’s OK because they’re here and now we can all talk about them!!

66 notes

·

View notes

Text

makes me sad how people only see marius’s bonapartism as “haha dumb sheltered kid has dumb political beliefs” and not like…the product of trauma

i mean it’s not like he just woke up one day and was like, “wow! dictatorship ROCKS!”

he grew up being made to believe his father didn’t love him and abandoned him?? so much so that when he dies he just feels. nothing. because he felt no connection to this man whatsoever except being ashamed for who he was. when he finds out that his father actually did love him, he feels TREMENDOUS guilt for his antipathy towards him all these years, even though it of course wasn’t his fault. so he clings to his father’s military career and the baronetcy as a way to feel connected to him, like he’s honoring him the way he didn’t do while he was alive.

and like he does face severe consequences for this. he’s kicked out of the house by his grandfather and becomes homeless at 17. i feel like people tend to gloss over this bit because yay, we get to meet courfeyrac and everyone, but yeah let’s not forget marius is literally a homeless teenager at this point.

so it is deeply painful for him to challenge these beliefs, because he feels like he’s betraying his father again by doing so. he’s been robbed of his heritage and any meaningful relationship he could have had with his father by his abusive family and this is the only link he has left to him.

again, this is essentially a kid growing up in an emotionally and physically abusive conservative household who gets kicked out for daring to express different beliefs, so yeah i do feel compelled to cut him a little slack where those beliefs are concerned.

257 notes

·

View notes

Text

MARIUS PONTMERCY - Les Misérables

PROPAGANDA:

so like. the fandom has a whole word for doing dumb shit (pontmercying) named after him. he is so silly goofy actually. at some point his girlfriend has to move away so he slams his head against a tree for 2 hours. one time marius' friend introduces him to his other friends (known revolutionary guys) and he spends at least 2 pages praising napoleon bonaparte (because i think he has a crush on napoleon bonaparte) and then he gets shut down by two words lmao.

also all of said friends die on the barricades so i think he deserves something at least :((((

in conclusion marius pontmercy is a pathetic lil man and you all should love him <3

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

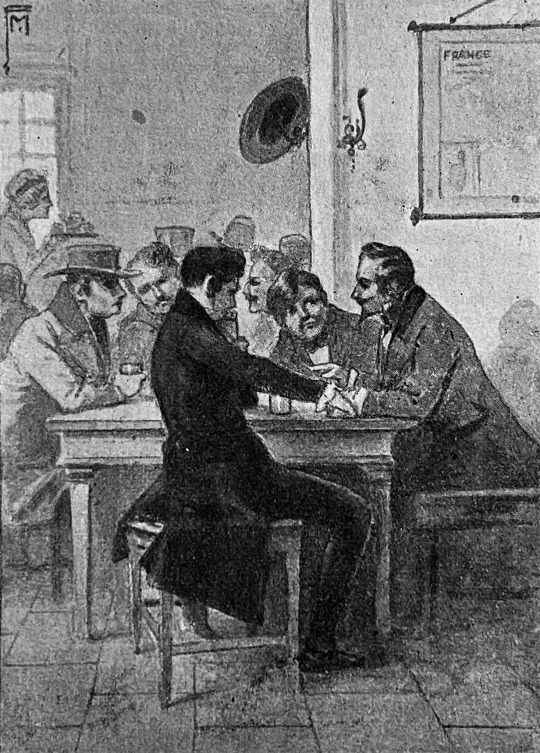

..In the midst of the uproar, Bossuet all at once terminated some apostrophe to Combeferre, with this date:—

‘June 18th, 1815, Waterloo.’

At this name of Waterloo, Marius, who was leaning his elbows on a table, beside a glass of water, removed his wrist from beneath his chin, and began to gaze fixedly at the audience.

‘Pardieu!’ exclaimed Courfeyrac (“Parbleu’ was falling into disuse at this period), ‘that number 18 is strange and strikes me. It is Bonaparte’s fatal number. Place Louis in front and Brumaire behind, you have the whole destiny of the man, with this significant peculiarity, that the end treads close on the heels of the commencement.’

Enjolras, who had remained mute up to that point, broke the silence and addressed this remark to Combeferre:—

‘You mean to say, the crime and the expiation.’

This word “crime” overpassed the measure of what Marius, who was already greatly agitated by the abrupt evocation of Waterloo, could accept.

Vol.III - Book.IV - Ch.V

#les miserables#les mis#les amis#Bossuet#courfeyrac#enjolras#marius#(Enlargement Of Horizon)#Adriano Minardi Illustrations#illustration

103 notes

·

View notes