#different political philosophies and directions of taking France

Text

Hot take: by the time Hugo picked Les Mis back up in 1860 to finish it, I don't think he intended for Marius and Cosette's marriage to be a good or happy one.

#I just got home after being out of my house nearly fourteen hours#and it is past my bedtime with a very early start intended for tomorrow#but the gist of the argument is that Fantine was the best of us — the French empire under Bonaparte!#and Cosette as Hugo was writing her in 1848 was intended to be the extension of that progress!#and Marius in Bonapartism!#(and then you have the amis who are different levels of supporters of Robespierre and Babeuf and maybe even Lafayette a little)#different political philosophies and directions of taking France#and by 1860 when Hugo was picking up at Blotter Talks#he was fully aware that Actually returning to the Bonaparte line kinda sucked and so did that dick NIII#who forced Hugo to flee to England where he had to (gasp) listen to people speak God's imperfect middle child language English#and he was like ''actually Cosette marrying Marius isn't all it's cracked up to be#idk I'm probably missing a ton of crucial context and background that will easily swat down this theory#but as of 21.45 18 Oct 2022 GMT+8 or whatever that is my take#PLEASE feel free to provide more info#les mis#shitposting @ me#marius#marisette#cosette

10 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Two generations preceding 1789

In the two generations preceding 1789, such Englishmen as Boling- broke, Hume, Adam Smith, Priestley, Bentham, John Howard (one might almost claim part, at least, of Burke and of Pitt); such Americans as Franklin, Washington, and Jefferson; such Italians as Beccaria and Galiani; such Germans as Lessing, Goethe, Frederick the Great, and Joseph 11., had as much part in it as Voltaire, Montesquieu, Turgot, Diderot, and Condorcet, and the rest of the French thinkers who are specially associated in our thoughts with the movement so ill-described as the French Revolution.

By the efforts of such men every element of modern society, and every political institution as we now know it, had been reviewed and debated — not, indeed, with any coherent doctrine, and utterly without system or method. The reformers differed much amongst themselves, and there were almost as many schemes of political philosophy, of social economy, or practical organisation, as there were writers and speakers. But in the result, what we now call modern Europe emerged, recast in State, in Church, in financial, commercial, and industrial organisation, with a new legal system, a new fiscal system, a humane code, and religious equality.

Over the whole of Europe the civil and criminal code was entirely recast; cruel punishments, barbarous sentences, anomalies, and confusion were swept away; the treatment of criminals, of the sick, of the insane, and of the destitute was subjected to a continuous and systematic reform, of which we have as yet seen only the first instalment. The whole range of fiscal taxation, local and imperial, external and internal, direct and indirect, has been in almost every part of Western Europe entirely reformed. A new local administration on the principle of departments, subdivided into districts, cantons, and communes, has been established in France, and thence copied in a large part of Europe customized tours istanbul.

The old feudal system of territorial law

The old feudal system of territorial law, which in England had been to a great extent reformed at the Civil War, was recast not only in France but in the greater part of Western Europe. Protestants, Jews, and Dissenters of all orders practically obtained full toleration and the right of worship. The monstrous corruption and wealth of the remnants of the mediaeval Church was reduced to manageable proportions. Public education became one of the great functions of the State. Public health, public morality, science, art, industry, roads, posts, and trade became the substantive business of government. These are ‘the ideas of ’89’ — these are the ideas which for two generations before ’89 Europe had been preparing, and which for three generations since ’89 she has been systematically working out.

We have just taken a rapid survey of Franee in its political and material organisation down to 1789, let us take an equally rapid survey of the new institutions which 1789 so loudly proclaimed, and so stormily introduced.

For the old patriarchal, proprietary, de jure theory of rule, there was everywhere substituted on the continent of Europe the popular, fiduciary, pro bono publico notion of rule. Government ceased to be the privilege of the ruler; it became a trust imposed on the ruler for the common weal of the ruled. Long before 1789 this general idea had been established in England and in the United States.

0 notes

Photo

Two generations preceding 1789

In the two generations preceding 1789, such Englishmen as Boling- broke, Hume, Adam Smith, Priestley, Bentham, John Howard (one might almost claim part, at least, of Burke and of Pitt); such Americans as Franklin, Washington, and Jefferson; such Italians as Beccaria and Galiani; such Germans as Lessing, Goethe, Frederick the Great, and Joseph 11., had as much part in it as Voltaire, Montesquieu, Turgot, Diderot, and Condorcet, and the rest of the French thinkers who are specially associated in our thoughts with the movement so ill-described as the French Revolution.

By the efforts of such men every element of modern society, and every political institution as we now know it, had been reviewed and debated — not, indeed, with any coherent doctrine, and utterly without system or method. The reformers differed much amongst themselves, and there were almost as many schemes of political philosophy, of social economy, or practical organisation, as there were writers and speakers. But in the result, what we now call modern Europe emerged, recast in State, in Church, in financial, commercial, and industrial organisation, with a new legal system, a new fiscal system, a humane code, and religious equality.

Over the whole of Europe the civil and criminal code was entirely recast; cruel punishments, barbarous sentences, anomalies, and confusion were swept away; the treatment of criminals, of the sick, of the insane, and of the destitute was subjected to a continuous and systematic reform, of which we have as yet seen only the first instalment. The whole range of fiscal taxation, local and imperial, external and internal, direct and indirect, has been in almost every part of Western Europe entirely reformed. A new local administration on the principle of departments, subdivided into districts, cantons, and communes, has been established in France, and thence copied in a large part of Europe customized tours istanbul.

The old feudal system of territorial law

The old feudal system of territorial law, which in England had been to a great extent reformed at the Civil War, was recast not only in France but in the greater part of Western Europe. Protestants, Jews, and Dissenters of all orders practically obtained full toleration and the right of worship. The monstrous corruption and wealth of the remnants of the mediaeval Church was reduced to manageable proportions. Public education became one of the great functions of the State. Public health, public morality, science, art, industry, roads, posts, and trade became the substantive business of government. These are ‘the ideas of ’89’ — these are the ideas which for two generations before ’89 Europe had been preparing, and which for three generations since ’89 she has been systematically working out.

We have just taken a rapid survey of Franee in its political and material organisation down to 1789, let us take an equally rapid survey of the new institutions which 1789 so loudly proclaimed, and so stormily introduced.

For the old patriarchal, proprietary, de jure theory of rule, there was everywhere substituted on the continent of Europe the popular, fiduciary, pro bono publico notion of rule. Government ceased to be the privilege of the ruler; it became a trust imposed on the ruler for the common weal of the ruled. Long before 1789 this general idea had been established in England and in the United States.

0 notes

Photo

Two generations preceding 1789

In the two generations preceding 1789, such Englishmen as Boling- broke, Hume, Adam Smith, Priestley, Bentham, John Howard (one might almost claim part, at least, of Burke and of Pitt); such Americans as Franklin, Washington, and Jefferson; such Italians as Beccaria and Galiani; such Germans as Lessing, Goethe, Frederick the Great, and Joseph 11., had as much part in it as Voltaire, Montesquieu, Turgot, Diderot, and Condorcet, and the rest of the French thinkers who are specially associated in our thoughts with the movement so ill-described as the French Revolution.

By the efforts of such men every element of modern society, and every political institution as we now know it, had been reviewed and debated — not, indeed, with any coherent doctrine, and utterly without system or method. The reformers differed much amongst themselves, and there were almost as many schemes of political philosophy, of social economy, or practical organisation, as there were writers and speakers. But in the result, what we now call modern Europe emerged, recast in State, in Church, in financial, commercial, and industrial organisation, with a new legal system, a new fiscal system, a humane code, and religious equality.

Over the whole of Europe the civil and criminal code was entirely recast; cruel punishments, barbarous sentences, anomalies, and confusion were swept away; the treatment of criminals, of the sick, of the insane, and of the destitute was subjected to a continuous and systematic reform, of which we have as yet seen only the first instalment. The whole range of fiscal taxation, local and imperial, external and internal, direct and indirect, has been in almost every part of Western Europe entirely reformed. A new local administration on the principle of departments, subdivided into districts, cantons, and communes, has been established in France, and thence copied in a large part of Europe customized tours istanbul.

The old feudal system of territorial law

The old feudal system of territorial law, which in England had been to a great extent reformed at the Civil War, was recast not only in France but in the greater part of Western Europe. Protestants, Jews, and Dissenters of all orders practically obtained full toleration and the right of worship. The monstrous corruption and wealth of the remnants of the mediaeval Church was reduced to manageable proportions. Public education became one of the great functions of the State. Public health, public morality, science, art, industry, roads, posts, and trade became the substantive business of government. These are ‘the ideas of ’89’ — these are the ideas which for two generations before ’89 Europe had been preparing, and which for three generations since ’89 she has been systematically working out.

We have just taken a rapid survey of Franee in its political and material organisation down to 1789, let us take an equally rapid survey of the new institutions which 1789 so loudly proclaimed, and so stormily introduced.

For the old patriarchal, proprietary, de jure theory of rule, there was everywhere substituted on the continent of Europe the popular, fiduciary, pro bono publico notion of rule. Government ceased to be the privilege of the ruler; it became a trust imposed on the ruler for the common weal of the ruled. Long before 1789 this general idea had been established in England and in the United States.

0 notes

Photo

Two generations preceding 1789

In the two generations preceding 1789, such Englishmen as Boling- broke, Hume, Adam Smith, Priestley, Bentham, John Howard (one might almost claim part, at least, of Burke and of Pitt); such Americans as Franklin, Washington, and Jefferson; such Italians as Beccaria and Galiani; such Germans as Lessing, Goethe, Frederick the Great, and Joseph 11., had as much part in it as Voltaire, Montesquieu, Turgot, Diderot, and Condorcet, and the rest of the French thinkers who are specially associated in our thoughts with the movement so ill-described as the French Revolution.

By the efforts of such men every element of modern society, and every political institution as we now know it, had been reviewed and debated — not, indeed, with any coherent doctrine, and utterly without system or method. The reformers differed much amongst themselves, and there were almost as many schemes of political philosophy, of social economy, or practical organisation, as there were writers and speakers. But in the result, what we now call modern Europe emerged, recast in State, in Church, in financial, commercial, and industrial organisation, with a new legal system, a new fiscal system, a humane code, and religious equality.

Over the whole of Europe the civil and criminal code was entirely recast; cruel punishments, barbarous sentences, anomalies, and confusion were swept away; the treatment of criminals, of the sick, of the insane, and of the destitute was subjected to a continuous and systematic reform, of which we have as yet seen only the first instalment. The whole range of fiscal taxation, local and imperial, external and internal, direct and indirect, has been in almost every part of Western Europe entirely reformed. A new local administration on the principle of departments, subdivided into districts, cantons, and communes, has been established in France, and thence copied in a large part of Europe customized tours istanbul.

The old feudal system of territorial law

The old feudal system of territorial law, which in England had been to a great extent reformed at the Civil War, was recast not only in France but in the greater part of Western Europe. Protestants, Jews, and Dissenters of all orders practically obtained full toleration and the right of worship. The monstrous corruption and wealth of the remnants of the mediaeval Church was reduced to manageable proportions. Public education became one of the great functions of the State. Public health, public morality, science, art, industry, roads, posts, and trade became the substantive business of government. These are ‘the ideas of ’89’ — these are the ideas which for two generations before ’89 Europe had been preparing, and which for three generations since ’89 she has been systematically working out.

We have just taken a rapid survey of Franee in its political and material organisation down to 1789, let us take an equally rapid survey of the new institutions which 1789 so loudly proclaimed, and so stormily introduced.

For the old patriarchal, proprietary, de jure theory of rule, there was everywhere substituted on the continent of Europe the popular, fiduciary, pro bono publico notion of rule. Government ceased to be the privilege of the ruler; it became a trust imposed on the ruler for the common weal of the ruled. Long before 1789 this general idea had been established in England and in the United States.

0 notes

Photo

Two generations preceding 1789

In the two generations preceding 1789, such Englishmen as Boling- broke, Hume, Adam Smith, Priestley, Bentham, John Howard (one might almost claim part, at least, of Burke and of Pitt); such Americans as Franklin, Washington, and Jefferson; such Italians as Beccaria and Galiani; such Germans as Lessing, Goethe, Frederick the Great, and Joseph 11., had as much part in it as Voltaire, Montesquieu, Turgot, Diderot, and Condorcet, and the rest of the French thinkers who are specially associated in our thoughts with the movement so ill-described as the French Revolution.

By the efforts of such men every element of modern society, and every political institution as we now know it, had been reviewed and debated — not, indeed, with any coherent doctrine, and utterly without system or method. The reformers differed much amongst themselves, and there were almost as many schemes of political philosophy, of social economy, or practical organisation, as there were writers and speakers. But in the result, what we now call modern Europe emerged, recast in State, in Church, in financial, commercial, and industrial organisation, with a new legal system, a new fiscal system, a humane code, and religious equality.

Over the whole of Europe the civil and criminal code was entirely recast; cruel punishments, barbarous sentences, anomalies, and confusion were swept away; the treatment of criminals, of the sick, of the insane, and of the destitute was subjected to a continuous and systematic reform, of which we have as yet seen only the first instalment. The whole range of fiscal taxation, local and imperial, external and internal, direct and indirect, has been in almost every part of Western Europe entirely reformed. A new local administration on the principle of departments, subdivided into districts, cantons, and communes, has been established in France, and thence copied in a large part of Europe customized tours istanbul.

The old feudal system of territorial law

The old feudal system of territorial law, which in England had been to a great extent reformed at the Civil War, was recast not only in France but in the greater part of Western Europe. Protestants, Jews, and Dissenters of all orders practically obtained full toleration and the right of worship. The monstrous corruption and wealth of the remnants of the mediaeval Church was reduced to manageable proportions. Public education became one of the great functions of the State. Public health, public morality, science, art, industry, roads, posts, and trade became the substantive business of government. These are ‘the ideas of ’89’ — these are the ideas which for two generations before ’89 Europe had been preparing, and which for three generations since ’89 she has been systematically working out.

We have just taken a rapid survey of Franee in its political and material organisation down to 1789, let us take an equally rapid survey of the new institutions which 1789 so loudly proclaimed, and so stormily introduced.

For the old patriarchal, proprietary, de jure theory of rule, there was everywhere substituted on the continent of Europe the popular, fiduciary, pro bono publico notion of rule. Government ceased to be the privilege of the ruler; it became a trust imposed on the ruler for the common weal of the ruled. Long before 1789 this general idea had been established in England and in the United States.

0 notes

Photo

Two generations preceding 1789

In the two generations preceding 1789, such Englishmen as Boling- broke, Hume, Adam Smith, Priestley, Bentham, John Howard (one might almost claim part, at least, of Burke and of Pitt); such Americans as Franklin, Washington, and Jefferson; such Italians as Beccaria and Galiani; such Germans as Lessing, Goethe, Frederick the Great, and Joseph 11., had as much part in it as Voltaire, Montesquieu, Turgot, Diderot, and Condorcet, and the rest of the French thinkers who are specially associated in our thoughts with the movement so ill-described as the French Revolution.

By the efforts of such men every element of modern society, and every political institution as we now know it, had been reviewed and debated — not, indeed, with any coherent doctrine, and utterly without system or method. The reformers differed much amongst themselves, and there were almost as many schemes of political philosophy, of social economy, or practical organisation, as there were writers and speakers. But in the result, what we now call modern Europe emerged, recast in State, in Church, in financial, commercial, and industrial organisation, with a new legal system, a new fiscal system, a humane code, and religious equality.

Over the whole of Europe the civil and criminal code was entirely recast; cruel punishments, barbarous sentences, anomalies, and confusion were swept away; the treatment of criminals, of the sick, of the insane, and of the destitute was subjected to a continuous and systematic reform, of which we have as yet seen only the first instalment. The whole range of fiscal taxation, local and imperial, external and internal, direct and indirect, has been in almost every part of Western Europe entirely reformed. A new local administration on the principle of departments, subdivided into districts, cantons, and communes, has been established in France, and thence copied in a large part of Europe customized tours istanbul.

The old feudal system of territorial law

The old feudal system of territorial law, which in England had been to a great extent reformed at the Civil War, was recast not only in France but in the greater part of Western Europe. Protestants, Jews, and Dissenters of all orders practically obtained full toleration and the right of worship. The monstrous corruption and wealth of the remnants of the mediaeval Church was reduced to manageable proportions. Public education became one of the great functions of the State. Public health, public morality, science, art, industry, roads, posts, and trade became the substantive business of government. These are ‘the ideas of ’89’ — these are the ideas which for two generations before ’89 Europe had been preparing, and which for three generations since ’89 she has been systematically working out.

We have just taken a rapid survey of Franee in its political and material organisation down to 1789, let us take an equally rapid survey of the new institutions which 1789 so loudly proclaimed, and so stormily introduced.

For the old patriarchal, proprietary, de jure theory of rule, there was everywhere substituted on the continent of Europe the popular, fiduciary, pro bono publico notion of rule. Government ceased to be the privilege of the ruler; it became a trust imposed on the ruler for the common weal of the ruled. Long before 1789 this general idea had been established in England and in the United States.

0 notes

Photo

Two generations preceding 1789

In the two generations preceding 1789, such Englishmen as Boling- broke, Hume, Adam Smith, Priestley, Bentham, John Howard (one might almost claim part, at least, of Burke and of Pitt); such Americans as Franklin, Washington, and Jefferson; such Italians as Beccaria and Galiani; such Germans as Lessing, Goethe, Frederick the Great, and Joseph 11., had as much part in it as Voltaire, Montesquieu, Turgot, Diderot, and Condorcet, and the rest of the French thinkers who are specially associated in our thoughts with the movement so ill-described as the French Revolution.

By the efforts of such men every element of modern society, and every political institution as we now know it, had been reviewed and debated — not, indeed, with any coherent doctrine, and utterly without system or method. The reformers differed much amongst themselves, and there were almost as many schemes of political philosophy, of social economy, or practical organisation, as there were writers and speakers. But in the result, what we now call modern Europe emerged, recast in State, in Church, in financial, commercial, and industrial organisation, with a new legal system, a new fiscal system, a humane code, and religious equality.

Over the whole of Europe the civil and criminal code was entirely recast; cruel punishments, barbarous sentences, anomalies, and confusion were swept away; the treatment of criminals, of the sick, of the insane, and of the destitute was subjected to a continuous and systematic reform, of which we have as yet seen only the first instalment. The whole range of fiscal taxation, local and imperial, external and internal, direct and indirect, has been in almost every part of Western Europe entirely reformed. A new local administration on the principle of departments, subdivided into districts, cantons, and communes, has been established in France, and thence copied in a large part of Europe customized tours istanbul.

The old feudal system of territorial law

The old feudal system of territorial law, which in England had been to a great extent reformed at the Civil War, was recast not only in France but in the greater part of Western Europe. Protestants, Jews, and Dissenters of all orders practically obtained full toleration and the right of worship. The monstrous corruption and wealth of the remnants of the mediaeval Church was reduced to manageable proportions. Public education became one of the great functions of the State. Public health, public morality, science, art, industry, roads, posts, and trade became the substantive business of government. These are ‘the ideas of ’89’ — these are the ideas which for two generations before ’89 Europe had been preparing, and which for three generations since ’89 she has been systematically working out.

We have just taken a rapid survey of Franee in its political and material organisation down to 1789, let us take an equally rapid survey of the new institutions which 1789 so loudly proclaimed, and so stormily introduced.

For the old patriarchal, proprietary, de jure theory of rule, there was everywhere substituted on the continent of Europe the popular, fiduciary, pro bono publico notion of rule. Government ceased to be the privilege of the ruler; it became a trust imposed on the ruler for the common weal of the ruled. Long before 1789 this general idea had been established in England and in the United States.

0 notes

Photo

Two generations preceding 1789

In the two generations preceding 1789, such Englishmen as Boling- broke, Hume, Adam Smith, Priestley, Bentham, John Howard (one might almost claim part, at least, of Burke and of Pitt); such Americans as Franklin, Washington, and Jefferson; such Italians as Beccaria and Galiani; such Germans as Lessing, Goethe, Frederick the Great, and Joseph 11., had as much part in it as Voltaire, Montesquieu, Turgot, Diderot, and Condorcet, and the rest of the French thinkers who are specially associated in our thoughts with the movement so ill-described as the French Revolution.

By the efforts of such men every element of modern society, and every political institution as we now know it, had been reviewed and debated — not, indeed, with any coherent doctrine, and utterly without system or method. The reformers differed much amongst themselves, and there were almost as many schemes of political philosophy, of social economy, or practical organisation, as there were writers and speakers. But in the result, what we now call modern Europe emerged, recast in State, in Church, in financial, commercial, and industrial organisation, with a new legal system, a new fiscal system, a humane code, and religious equality.

Over the whole of Europe the civil and criminal code was entirely recast; cruel punishments, barbarous sentences, anomalies, and confusion were swept away; the treatment of criminals, of the sick, of the insane, and of the destitute was subjected to a continuous and systematic reform, of which we have as yet seen only the first instalment. The whole range of fiscal taxation, local and imperial, external and internal, direct and indirect, has been in almost every part of Western Europe entirely reformed. A new local administration on the principle of departments, subdivided into districts, cantons, and communes, has been established in France, and thence copied in a large part of Europe customized tours istanbul.

The old feudal system of territorial law

The old feudal system of territorial law, which in England had been to a great extent reformed at the Civil War, was recast not only in France but in the greater part of Western Europe. Protestants, Jews, and Dissenters of all orders practically obtained full toleration and the right of worship. The monstrous corruption and wealth of the remnants of the mediaeval Church was reduced to manageable proportions. Public education became one of the great functions of the State. Public health, public morality, science, art, industry, roads, posts, and trade became the substantive business of government. These are ‘the ideas of ’89’ — these are the ideas which for two generations before ’89 Europe had been preparing, and which for three generations since ’89 she has been systematically working out.

We have just taken a rapid survey of Franee in its political and material organisation down to 1789, let us take an equally rapid survey of the new institutions which 1789 so loudly proclaimed, and so stormily introduced.

For the old patriarchal, proprietary, de jure theory of rule, there was everywhere substituted on the continent of Europe the popular, fiduciary, pro bono publico notion of rule. Government ceased to be the privilege of the ruler; it became a trust imposed on the ruler for the common weal of the ruled. Long before 1789 this general idea had been established in England and in the United States.

0 notes

Photo

Two generations preceding 1789

In the two generations preceding 1789, such Englishmen as Boling- broke, Hume, Adam Smith, Priestley, Bentham, John Howard (one might almost claim part, at least, of Burke and of Pitt); such Americans as Franklin, Washington, and Jefferson; such Italians as Beccaria and Galiani; such Germans as Lessing, Goethe, Frederick the Great, and Joseph 11., had as much part in it as Voltaire, Montesquieu, Turgot, Diderot, and Condorcet, and the rest of the French thinkers who are specially associated in our thoughts with the movement so ill-described as the French Revolution.

By the efforts of such men every element of modern society, and every political institution as we now know it, had been reviewed and debated — not, indeed, with any coherent doctrine, and utterly without system or method. The reformers differed much amongst themselves, and there were almost as many schemes of political philosophy, of social economy, or practical organisation, as there were writers and speakers. But in the result, what we now call modern Europe emerged, recast in State, in Church, in financial, commercial, and industrial organisation, with a new legal system, a new fiscal system, a humane code, and religious equality.

Over the whole of Europe the civil and criminal code was entirely recast; cruel punishments, barbarous sentences, anomalies, and confusion were swept away; the treatment of criminals, of the sick, of the insane, and of the destitute was subjected to a continuous and systematic reform, of which we have as yet seen only the first instalment. The whole range of fiscal taxation, local and imperial, external and internal, direct and indirect, has been in almost every part of Western Europe entirely reformed. A new local administration on the principle of departments, subdivided into districts, cantons, and communes, has been established in France, and thence copied in a large part of Europe customized tours istanbul.

The old feudal system of territorial law

The old feudal system of territorial law, which in England had been to a great extent reformed at the Civil War, was recast not only in France but in the greater part of Western Europe. Protestants, Jews, and Dissenters of all orders practically obtained full toleration and the right of worship. The monstrous corruption and wealth of the remnants of the mediaeval Church was reduced to manageable proportions. Public education became one of the great functions of the State. Public health, public morality, science, art, industry, roads, posts, and trade became the substantive business of government. These are ‘the ideas of ’89’ — these are the ideas which for two generations before ’89 Europe had been preparing, and which for three generations since ’89 she has been systematically working out.

We have just taken a rapid survey of Franee in its political and material organisation down to 1789, let us take an equally rapid survey of the new institutions which 1789 so loudly proclaimed, and so stormily introduced.

For the old patriarchal, proprietary, de jure theory of rule, there was everywhere substituted on the continent of Europe the popular, fiduciary, pro bono publico notion of rule. Government ceased to be the privilege of the ruler; it became a trust imposed on the ruler for the common weal of the ruled. Long before 1789 this general idea had been established in England and in the United States.

0 notes

Photo

Two generations preceding 1789

In the two generations preceding 1789, such Englishmen as Boling- broke, Hume, Adam Smith, Priestley, Bentham, John Howard (one might almost claim part, at least, of Burke and of Pitt); such Americans as Franklin, Washington, and Jefferson; such Italians as Beccaria and Galiani; such Germans as Lessing, Goethe, Frederick the Great, and Joseph 11., had as much part in it as Voltaire, Montesquieu, Turgot, Diderot, and Condorcet, and the rest of the French thinkers who are specially associated in our thoughts with the movement so ill-described as the French Revolution.

By the efforts of such men every element of modern society, and every political institution as we now know it, had been reviewed and debated — not, indeed, with any coherent doctrine, and utterly without system or method. The reformers differed much amongst themselves, and there were almost as many schemes of political philosophy, of social economy, or practical organisation, as there were writers and speakers. But in the result, what we now call modern Europe emerged, recast in State, in Church, in financial, commercial, and industrial organisation, with a new legal system, a new fiscal system, a humane code, and religious equality.

Over the whole of Europe the civil and criminal code was entirely recast; cruel punishments, barbarous sentences, anomalies, and confusion were swept away; the treatment of criminals, of the sick, of the insane, and of the destitute was subjected to a continuous and systematic reform, of which we have as yet seen only the first instalment. The whole range of fiscal taxation, local and imperial, external and internal, direct and indirect, has been in almost every part of Western Europe entirely reformed. A new local administration on the principle of departments, subdivided into districts, cantons, and communes, has been established in France, and thence copied in a large part of Europe customized tours istanbul.

The old feudal system of territorial law

The old feudal system of territorial law, which in England had been to a great extent reformed at the Civil War, was recast not only in France but in the greater part of Western Europe. Protestants, Jews, and Dissenters of all orders practically obtained full toleration and the right of worship. The monstrous corruption and wealth of the remnants of the mediaeval Church was reduced to manageable proportions. Public education became one of the great functions of the State. Public health, public morality, science, art, industry, roads, posts, and trade became the substantive business of government. These are ‘the ideas of ’89’ — these are the ideas which for two generations before ’89 Europe had been preparing, and which for three generations since ’89 she has been systematically working out.

We have just taken a rapid survey of Franee in its political and material organisation down to 1789, let us take an equally rapid survey of the new institutions which 1789 so loudly proclaimed, and so stormily introduced.

For the old patriarchal, proprietary, de jure theory of rule, there was everywhere substituted on the continent of Europe the popular, fiduciary, pro bono publico notion of rule. Government ceased to be the privilege of the ruler; it became a trust imposed on the ruler for the common weal of the ruled. Long before 1789 this general idea had been established in England and in the United States.

0 notes

Text

1971: The Year That Music Changed Everything Review – The Revolution Is Hummable

https://ift.tt/eA8V8J

Apple TV+’s 1971: The Year That Music Changed Everything is immersive and fairly ambitious. The eight-part documentary series wants to run 33 revolutions per minute, and only comes up about a third short. It captures how musicians’ fingers were on the pulse of the day’s headlines and the laid the tracks for the nights’ rhythms.

Artists sang the news, sometimes causing it, other times reacting. Rock and roll had grown up and rock musicians took on responsibilities. Rhythm and blues got loose and soul musicians took to the streets. A former University of California philosophy professor named Angela Davis was charged with aiding and abetting the murder of a judge and Aretha Franklin personally offered to post bail.

The documentary series points out how The Beatles took the lead on youth culture movement during the 1960s, and how the elder society tried to beat it down in the 1970s, only to have John Lennon read the news and write “Gimme Some Truth,” before breakfast. Or to charge Oz Magazine, a British underground newspaper, with obscenity, and find Lennon outside the courtroom with a bullhorn in his hand and a single about it on a flipside. British television tried to celebrate the wake of the Beatles’ breakup with regressive programming. American TV fought to stay as progressive as its radio stations.

The docu-series was inspired by the book Never a Dull Moment: 1971 the Year That Rock Exploded by David Hepworth, but leaves out all the more gossipy bits. We don’t get cake from the Mick and Bianca Jagger wedding, but we get exiled with the Rolling Stones right on Main Street. Co-directed by Asif Kapadia (Senna, Amy, Diego Maradona), James Rogan and Danielle Peck, 1971: The Year That Music Changed Everything doesn’t look away from rockstar excesses, but it also doesn’t indulge them. We get the feeling albums by the Stones and Sly and the Family Stone may have achieved perfection through the sloppiest of accidents.

The artistic stories are a lot of fun to watch, though. Listening to Keith Richards talking about getting out of France minutes before both the mob and the cops were about to bang down the door is almost as much fun as sitting in the mid-section of the speedway concert at Altamont. Far enough away from the Hell’s Angels pool cues, but close enough to feel the danger, and still at the right place for the sound mix.

The best part of 1971: The Year Music Changed Everything is the footage. We get a clip of George Harrison and Bob Dylan rehearsing a song they didn’t do on stage at The Concert for Bangladesh. Home movies capture the Stones in Villa Nellecôte, scoring dope and nodding out during sessions for Exile on Main St. There is footage of James Brown performing in Paris which hasn’t made its way to his fans here. Gritty black and white celluloid shows David Bowie awkwardly miming his way through his first visit to Warhol’s Factory. Candid photos capture insanely intimate moments like a fan biting Marc Bolan’s hair. It is fun to watch Dick Cavett try to crawl up his own ass while trying to interview James Baldwin and Sly Stone. One highlight is the Ike and Tina Turner Review, along with the Staple Singers and dozens of other Black musicians visiting Ghana for a concert.

It is exhilarating to hear Marvin Gaye explain, in his own words, why What’s Going On was the record he was put on this earth to make. It is very cool hearing Lennon say how much it means to have revolutionary music coming from Gaye. There are no talking heads. Interviews, like those done with Elton John, are only heard through voice-overs. This adds to the intimacy of Chrissie Hynde of the Pretenders remembering how personally she took Crosby, Stills, Nash and Young’s song “Ohio,” after having been on the campus at Kent State during the shootings. It stands in stark contrast to President Richard Nixon declaring his love for “square music” while he gives an “off with their heads” glare at the most civil of disobedient young people.

The documentary mixes the musical stories with the period’s news. Archival footage includes protests, police brutality, the My Lai massacre trials, Charles Manson, and Lance Loud, who taught American families to embrace differences on the proto-reality TV show An American Family. The documentary also shows Nixon launching the war on drugs as a military offensive. It takes on the Attica prison uprising, and the prison study at Stanford, which proved anyone can be a mindlessly cruel bastard if they have something to hide behind, like a badge and a baton. The documentary doesn’t mention it, but the study seems even more accurate when considering the attempted damage done by anonymous Internet trollers. The documentary also offers a broad spectrum of retro-fashion tips.

The post-counterculture musicians didn’t only face political pressure. The documentary also highlights how newer artists were challenging the established pecking order of rock. A slightly premature delving into Glam Rock rebels Bowie and T. Rex’s Marc Bolan replaces any segments on heavy metal and hard rock. “We were creating the 21st century in 1971,” Bowie says in the opening of every installment. We applaud as Kraftwerk fires their drummer for a drum machine.

Because the series focuses on the theme of interactive social change, it skips a lot of what was happening musically in 1971. Some of it is understandable, and some appears arbitrary. Not to let one bad apple spoil the whole bunch, but the series includes a segment on the Osmonds but doesn’t mention The Jackson 5. While we get a broad overview of world music, we get precious little of the electricity of Latin percussion which propelled Santana and War.

The doc talks about the growing Jesus Saves movement which was sonically represented in Jesus Christ Superstar, but they don’t even offer a sound clip of Jethro Tull’s Aqualung, which proclaimed “man created god.” I get it, a lot of the rock and roll press, and I’m looking at you Rolling Stone, has had a bug up their ass about prog music for years. The documentary relegates all of eight seconds to Yes, but only as an example of the snobbishness of dinosaur rock. But this is 1971, even T-Rex is new. The Flintstones hadn’t been off TV for a decade.

“Rock stars, is there nothing they don’t know?” Homer Simpson once asked, reverently. That kind of thinking began in 1971. Musicians were the most influential people on the planet. When Carole King told you to get up every morning with a smile on your face, you felt beautiful. If Gil Scott-Heron warned you about the cop’s “No Knock” policy, you double locked your door. 1971: The Year Music Changed Everything is an excellent time capsule of music from a time which was a lot less innocent. How do we get that lack of innocence back?

cnx.cmd.push(function() { cnx({ playerId: "106e33c0-3911-473c-b599-b1426db57530", }).render("0270c398a82f44f49c23c16122516796"); });

1971: The Year Music Changed Everything begins streaming on Apple TV+ on May 21.

The post 1971: The Year That Music Changed Everything Review – The Revolution Is Hummable appeared first on Den of Geek.

from Den of Geek https://ift.tt/3hBH4ad

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

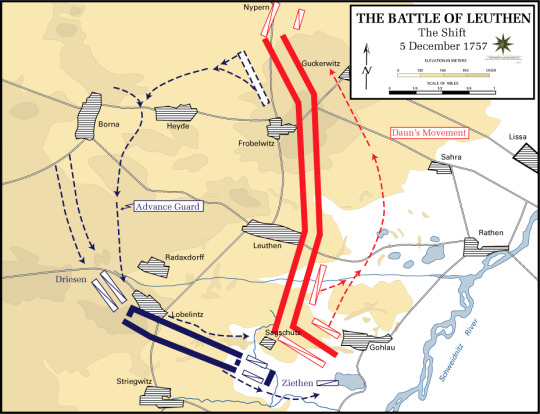

On this day in history: Battle of Leuthen (1757): Frederick the Great perfects his oblique order.

The Seven Years War (1756-1763) is regarded by many as the first true world war. It was fought on five continents and in many oceans, it was at its heart a battle of supremacy for worldwide influence, namely between Britain and France. Its origins were in colonial conflict between these two powers in North America which became known as the French & Indian War. However, it was also fought with a particularly ferocity in Europe. Britain was not a main participant involved in the European theater, instead this sector of fighting largely centered around their two main allies in this conflict and question of continental supremacy in Central Europe. it was the seeds to the so called German Question, would German speaking lands of Europe, then divided into the many entities of the Holy Roman Empire, be lead by the continual leadership of the Hapsburg Realm known based in the Archduchy of Austria or would it follow the Kingdom of Prussia?

Prelude: The German Question

-By the 18th century, the Holy Roman Empire, Central Europe and the German speaking peoples of Europe had largely been under the leadership of Vienna and the Hapsburg dynasty, then known as the Archduchy of Austria with its rulers serving as Holy Roman Emperor. A title that conveyed certain ceremonial & political weight with it. The Holy Roman Empire was a collection of mostly German speaking states that was concentrated in modern day Germany mostly alongside other parts of Central Europe. The Hapsburgs were its leading family and also held sway directly over parts of Italy, Bohemia, Hungary, Poland, Romania, Croatia, Italy and other parts of the Balkans. In the past its traditional enemy was the Ottoman Empire, long seen as the last bastion between Christendom and the spread of Islam throughout Europe.

-Its success against the Ottomans in the Great Turkish War (1683-1699) alongside Russia, Poland, Venice and other nations has essentially reversed the trend of Ottoman encroachment. Instead, the Turks now found themselves on the defensive and largely having to compete at against an expansionist Russia. Meanwhile, Austria challenged its longtime enemy France, now run by the Bourbon dynasty for control over influence within continental Europe.

-Austria sought Britain and the Dutch Republic’s assistance in containing French supremacy in Western and Central Europe, all these nations had a mutual interest in containing the expansion in French power which was coupled with the Bourbon’s taking over Spain and its empire too.

-Austria and France clashed in the War of the Spanish Succession (1701-1714) and the subsequent War of the Austrian Succession (1740-1748).

-It was in the last 17th and early 18th century and the aforementioned wars, that the Kingdom of Prussia, centered in northeastern Germany and run by the Lutheran Hohenzollern dynasty looked to gain power and influence.

-Prussia was comparatively small relative to Hapsburg lands but it built its reputation on its military prowess, starting with Frederick WIlliam, Elector of Brandenburg. As a member state of the Holy Roman Empire, it had a vote in the election of the Holy Roman Emperor, who was not a direct rule of other members of the fragmentary “empire” but a “first among equals” and one who held the most sway over the collective.

-Frederick William, his son and grandson (Frederick I) & (Frederick William I) were recognized Electors of Brandenburg and in the latter two’s case as Kings in Prussia and they made many military reforms that improved Prussia’s army.

-Under Leopold I, Prince of Anhalt-Dessau who served as Prussia’s royal military overseer a number of key reforms which set it apart from all other European armies were implemented. Firstly, he replaced the traditional wooden ramrod of muskets with which a soldier must plunge the musket ball into the barrel with an iron ramrod. The difference was stark, a more durable iron ramrod had a longer shelf-life than wood, was less prone to breaking and therefore was quicker for reloading. Secondly, he introduced the goose-step march which slowed the march of the army, conserving their energy when going into battle and providing for more uniform cohesion. Thirdly, he increased the role of the fife and drum musicians, making musicians out of some soldier and increasing the size of military marching bands, which was seen to boost morale. Fourth, he introduced relentless drilling with emphasis on the rate of fire and the maneuverability of units in formation. Fifth, the officer corps were directed and limited to the Junker (Prussian nobility) class which had a good miltary education and was firmly loyal to the Prussian nation and King. Additionally, firm but harsh corporal punishment was introduced to instill discipline and deter desertion. Finally, politically the introduction of mandatory conscription was more enforced in Prussia.

-All these elements left in place the Prussian Army becoming perhaps the most well oiled war machine in Europe at the time with only Austria, France, Britain and Russia being competitors, in time they would come to find out just how well trained and efficient this force was.

-As Prussia’s military reputation grew, so did its influence in the world of German politics and Austria clearly began to see it as a rival. Though initially, in the War of the Spanish Succession, both nations were together to curb French influence, with the Prussians serving with distinction as mercenaries under the Holy Roman Empire’s banner.

-1740, however changed things when two new rulers came to rule over Prussia & Austria. It started with Frederick II, the new King of Prussia. Frederick had a troubled relationship with father, Frederick William I. His father was well educated in government and military affairs and had hoped his son and heir would be inclined towards such matters too. Frederick was instead, prone to the burgeoning trends of the Enlightenment then coming into full flourish and sweeping Europe’s philosophy circles. Frederick was more interested in music, the arts and philosophy. His father also physical and mentally abused him, beating him with a cane and calling him many insults. To add to the strain, he appears to have been a homosexual, something punishable by death even for a royal during that time. Famously, he attempted to flee to Britain with his tutor/lover Han Hermann von Katte to escape the abuse by his father. However, both Frederick & Katte were caught in 1730 during their flight. Katte and Frederick were technically army officers and Frederick William I wanted to make an example of them for their flight as a betrayal of the nation. Though Katte’s initial sentence was imprisonment until the King’s death, Frederick William I instead ordered his execution. He made his son watch his friend and lover die by beheading, Frederick is said to have passed out at the sight of his lover’s execution by his father’s order. Frederick himself was also imprisoned by his father for the next two years.

-Eventually, father and son somewhat reconciled. In part, because he got Frederick to marry a woman, Elizabeth Christine of Brunswick-Wolfsbuttel. However, Frederick remained a semi-closeted gay man and never had children with his wife nor had any physical intimacy with her, though appears to have had no affairs with other women either. Instead, he always maintain an interest in the military and quite probably had male lovers & confidantes. Instead, the couple maintained separate residences over the course of their lives and Frederick knew full well the marriage was for political purposes. It was to last from 1733 until his death in 1786.

-Frederick came to the throne in 1740, having inherited a Prussia with a stable economy, efficient administration & most important of all, well trained and sizable army relative to its population. All things despite their often strained relationship he owed to his father. Of his father after his death he said:

“What a terrible man he was. But he was just, intelligent, and skilled in the management of affairs... it was through his efforts, through his tireless labor, that I have been able to accomplish everything that I have done since.”

-1740, also saw accession to the Austrian throne, Maria-Theresa, daughter of Charles VI, Holy Roman Emperor and Archduke of Austria. She had married, Francis, Duke of Lorraine, a Franco-German, portion of the Holy Roman Empire. Together, they would co-rule the Hapsburg Empire & give rise to the Hapsburg-Lorraine branch of the family, as Maria-Theresa was the last in the senior line of the Hapsburg family, which is declared to “die out” due to no more direct male heirs. Their subsequent branch would head the family and rule Austria in its many iterations through World War I in the form of the Austro-Hungarian Empire.

-The issue of Maria-Theresa’s gender came to be the powder keg for growing Austro-Prussian conflict. However, it was a smokescreen to expand Prussian power at Austrian expense, being just a convenient excuse other rulers needed to undermine Hapsburg rule as Holy Roman Emperors. Charles VI, aware of the problems caused by having no male heirs and relying on a system of primogeniture, where the eldest surviving legitimate male son or nearest male relative was given to rule, was forced to spend much of his reign using diplomacy and concessions to the other Electors of the Holy Roman Empire and great powers of Europe, to recognize his daughter as his heir and as Holy Roman Empress and ruler of Hapsburg lands. The Pragmatic Sanction of 1713 was the recognition by the other powers of Europe of her succession to these lands.

-However, looking to weaken the Austrians and get the balance of power set about in a more favorable fashion, France & Prussia backing the relative of Maria-Theresa, Charles-Albert of Bavaria, proclaimed his right to become Holy Roman Emperor. Making him in effect Charles VII, Holy Roman Emperor. He was of the House of Wittelsbach and his reign interrupted the Hapsburg claim to the title for the preceding 300 years. Citing, Salic Law, from the Middle Ages, neither France nor Prussia could truly “respect” a woman’s claim to hold the title of Holy Roman Emperor or to rule over the Hapsburg lands. For France it was about controlling the balance of power, for Frederick of Prussia, now Frederick II, it was a chance to increase Prussia’s profile. So launched the 8 year long War of the Austrian Succession. The war saw Frederick II invade Austrian Silesia in modern day Poland. With this Maria-Theresa & Frederick II were ever after archrivals.

- By 1745, Frederick’s army time and again surprised the Austrians and Europe at large and had more or less secured its war aims, Silesia. He secured for himself a reputation as a great tactician and for the Prussian army, a sense of true respect for their performance. The treaty of Aix-la-Chappelle in 1748 ended the war, Maria-Theresa was declared to be Holy Roman Empress and ruler of all Hapsburg lands with her husband who became Francis I as Holy Roman Emperor. Their family would continue to succeed them ever after. However, Frederick got to retain control of Silesia and this caused simmering tension and resentment with Maria-Theresa.

Diplomatic Revolution:

-In the years following the Treaty of Aix-la-Chappelle, the political goals of Europe’s great powers realigned. Britain and France still retained colonial rivalries the world over and both sought to have a favorable balance of power on the continent as well. Austria & Britain had been traditional allies for decades but with British support for Prussian claims to Silesia, Maria-Theresa no longer felt Britain could be a dependable ally in what she sought, a reclaiming of Silesia, she needed help to achieve this and turned to an unlikely place, its former rival...France.

-Meanwhile, Britain felt Austria itself was too weak to take on France and therefore was willing to subsidize other powers to contain French ambition on the continent while the Royal Navy & British Army took French colonies elsewhere. So a partner switch developed. Prussia & Britain signed an alliance in January 1756.

-Meanwhile. France at first declared neutrality thanks to diplomacy from Austria which no longer had borders on France’s natural borders and this lead to a thawing of icy relations. A series of treaties was signed between Austria and France in 1756-57 which formed an anti-Prussian coalition between the two and later supplemented by Russia & Sweden. France agreed to support Austria regaining Silesia, and subsidies for Austria to maintain a large army against the Prussians. In exchange at the war’s end, France would gain the Austrian Netherlands (Belgium). This would allow France new ports to threaten Britain.

War:

-War had broken out 1756 officially between Britain and France though their North American colonies had been fighting since 1754.

-Frederick II, sensing the growing alliance against him wanted to preempt any Austrian attack against Silesia and thusly invaded the Austrian ally, the Electorate of Saxony in August 1756, this kicked off the war and lead to many back and forth battles over the next 7 years.

-The war shifted in 1757 to Austrian Bohemia (Czech Republic) and left Prague under siege by the Prussians at one point. Frederick garnered many important early victories but was forced to withdraw in this instance.

-By late 1757, the French were providing Austria the long awaited support for its thrusts into Silesia. Prussia was gradually pushed back following the retreat from Prague and now was facing pressure from multiple approaches.

-This approach culminated in the November 1757 Battle of Rossbach, the only physical battle to involve both France & Prussia against each other. Frederick caught the Austro-Franco army by surprise and inflicted 10,000 casualties to his less than 1,000. France essentially remained a non-entity in this theater for the next several years, though they did continue to fund the Austrians. Austria’s real support would come later from Russia & Sweden against Prussia.

Battle of Leuthen:

-Meanwhile, another and even larger Austrian army was looking to engage Frederick, this one was lead by Maria-Theresa’s brother in law, Prince Charles Alexander of Lorraine. He sought to engage the Prussians and defeat Frederick decisively. Indeed he did defeat the Prussians, not under Frederick’s command at the Battle of Breslau in late November 1757 which threatened all of Prussian Silesia in December with 66,000 soldiers under his command.

-Frederick meanwhile had 33,000 meaning his troops would be outnumbered 2 to 1. Learning of the fall of Breslau, he moved his troops, 170 miles in just 12 days, a very accomplished maneuver given the roads and transport of the times.

-Prince Charles, aware of Frederick’s approach’s toward Breslau, the provincial capital of Silesia. He sought to stop the advance 17 miles west at the town of Leuthen.

-The Austrians hoped to check any Prussian countermove with a force running north to south spread out around Leuthen, knowing the Prussians would come from the west.

-Charles had placed his command in the village church tower to give him more of a vantage point over the rolling countryside displayed before his army. This meant he should be able to anticipate any move Prussia made.

-Frederick however, was quite familiar with the land, having used the Silesians countryside around Leuthen as parade and drilling grounds for the Prussian Army during peace time. Rarely one, to do the expected Frederick wanted to use his tactical prowess against the Austrians.

-His first step was to survey the land and hatch a plan. Austria’s strongest concentration of troops was on the left wing (south end) and their front stretched five miles north to south. Frederick, decided he would make the Austrians think he was in one place and then show in an unexpected place. His goal was to get the Austrians to react to this deceit which would provide an opening to his advantage.

-Realizing a series of low lying hills running almost parallel to the Austrian line lie in front of both armies. Frederick planned to use these hills to cover his troops movements for the main strike. First however, a force of cavalry would would launch an attack to distract the Austrians on the north end of the battlefield, the more lightly concentrated side. The Austrians thinking the attack was now coming from the north instead of the south would transfer the greatest concentration of troops from the south to north and check the Prussian attack. Meanwhile, Frederick employing his favorite tactic, oblique order would march from behind the hills to the now weakened south end of the Austrian line, perform a right angle turn and blast volleys into the weakened line, and roll it up from the south end, essentially performing a bait and switch on the Austrians.

-On the morning of December 5th, 1757, fog came onto the field, making it hard to see either side, this helped the Prussians more than the Austrians.

-Prince Charles saw Frederick’s initial moves early in the morning but interpreted them possibly as a retreat at first Meanwhile, Prussian cavalry attacked the north end of the Austrian line from the woods, indeed it seemed as if the Prussians were attacking the north end, having expected a southern end attack initially hence the greater concentration of troops. The worry was this attack coming from an unexpected direction could contribute to the Prussians rolling up the Austrian line.

-Charles reacted by shifting his entire southern flank’s reserve to reinforce and extend the line to the north. His transfer of troops drew out the line’s length and weakened the southern flank. They would in fact be facing the weaker Prussian attack, while the stronger attack would hit their originally anticipated southern flank, now weakened by deception. Little did he realize, he had fallen in Frederick’s trap.

-Indeed, Frederick marched his troops quietly in the fog and behind the hills before the Austrians, before he performed a right turn and executed oblique order, essentially moving the bulk of one’s forces against the weakened flank of the enemy and pushing them back so as to create an opening that forces the enemy line to shift, contort and break. His troops were well timed and disciplined to pull off such a maneuver.

-The main Prussian force marching south behind the hills was in two parallel columns. They moved past the length of the Austrian line and out of sight totally before veering eastward until they formed virtually a right angle with the Austrian line who was surprised by the sight of the Prussian army emerging from fog in battle line formation. The Prussian infantry opened fire with devastating volleys, keep in mind, the rate of five for Prussian infantrymen was 5 shots a minute per man compared to the 3-4 averaged by other European armies of the time. Their hard training had paid off with a faster and consequently more damaging rate of fire than their enemy.

-The Prussians now pushed forward against the confused and bedazzled Austrian army, which ironically, seeking to avoid being rolled up in the opposite direction, weakened their originally stronger side only to be rolled up anyway from a now completely unexpected direction.

-The Austrians had a few regiments try to check the Prussian advance from the south and indeed some artillery pointed south held them at bay but Frederick ordered some artillery of his own to be placed on one of the hills to the west of Leuthen, which in turn enfiladed the Austrian guns and forced them to withdraw.

-Meanwhile the Austrians tried to shift everything south in order to maintain control of the situation but the Prussian cavalry which had launched the screening attack on the Austrin north flank intially had withdrawn until was called into action by Frederick once more, causing more confusion for the Austrians who ultimately withdrew from the field, heading northeast.

-Frederick wanted to pursue but snowfall made him call off the pursuit. That night, Frederick arrived at the castle at nearby Lissa, occupied by both Austrian officers and refugees from villages caught near the battle. He politely surprised the Austrians by acknowledging they did not expect his presence their that night but did ask for lodging. Subsequently he went on to besiege Breslau and force an Austrian surrender.

-The war was far from over and Frederick and indeed Prussia’s fortunes fluctuated until its conclusion in 1763, in which Prussia would technically be the winner, retaining Silesia, in exchange for the recognition of Maria-Theresa’s son, Joseph as her heir. Though the war exhausted both sides in terms of manpower but ultimately, Frederick stopped Austrian +other Germans, French, Russian & Swedish armies from ending Prussia and his reign altogether.

-As a result of his tactical & strategic performance in this war and the preceding War of the Austrian Succession, he earned the historical moniker, Frederick the Great. The Battle of Leuthen was one illustration of the man’s tactical prowess, perhaps the most perfect example of this and more broadly of how far Prussia’s army had come from a comparative German backwater to the premier army on the European continent.

#on this day#military history#Seven Years War#third silesian war#prussia#tactics#oblique order#austria#Frederick the Great#maria theresa#holy roman empire#18th century#military tactics

10 notes

·

View notes

Quote

Both men could see the gap between propaganda and reality. Yet one remained an enthusiastic collaborator while the other could not bear the betrayal of his ideals. Why?

Why Do Republican Leaders Continue to Enable Trump? - The Atlantic

To understand, just ask yourself “What’s in it for him/her?” and your answer will materialize.

When we look at Republicans, why are they collaborating? They know what they’re doing is wrong. But they are willfully opting for money and power over humanity, over honor and dignity, over respect for other human beings. They are trade their souls for riches and power. Just don’t forget what they chose.

“In English, the word collaborator has a double meaning. A colleague can be described as a collaborator in a neutral or positive sense. But the other definition of collaborator, relevant here, is different: someone who works with the enemy, with the occupying power, with the dictatorial regime. In this negative sense, collaborator is closely related to another set of words: collusion, complicity, connivance. This negative meaning gained currency during the Second World War, when it was widely used to describe Europeans who cooperated with Nazi occupiers. At base, the ugly meaning of collaborator carries an implication of treason: betrayal of one’s nation, of one’s ideology, of one’s morality, of one’s values.

To the American reader, references to Vichy France, East Germany, fascists, and Communists may seem over-the-top, even ludicrous. But dig a little deeper, and the analogy makes sense. The point is not to compare Trump to Hitler or Stalin; the point is to compare the experiences of high-ranking members of the American Republican Party, especially those who work most closely with the White House, to the experiences of Frenchmen in 1940, or of East Germans in 1945, or of Czesław Miłosz in 1947. These are experiences of people who are forced to accept an alien ideology or a set of values that are in sharp conflict with their own.

It takes time to persuade people to abandon their existing value systems. The process usually begins slowly, with small changes.

Social scientists who have studied the erosion of values and the growth of corruption inside companies have found, for example, that “people are more likely to accept the unethical behavior of others if the behavior develops gradually (along a slippery slope) rather than occurring abruptly,” according to a 2009 article in the Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. This happens, in part, because most people have a built-in vision of themselves as moral and honest, and that self-image is resistant to change. Once certain behaviors become “normal,” then people stop seeing them as wrong.

But just as the truth about Hugo Chávez’s Bolivarian Revolution slowly dawned on people, it also became clear, eventually, that Trump did not have the interests of the American public at heart. And as they came to realize that the president was not a patriot, Republican politicians and senior civil servants began to equivocate, just like people living under an alien regime.

e·quiv·o·cate/əˈkwivəˌkāt/

verb

use ambiguous language so as to conceal the truth or avoid committing oneself."“Not that we are aware of,” she equivocated"

Nevertheless, 20 months into the Trump administration, senators and other serious-minded Republicans in public life who should have known better began to tell themselves stories that sound very much like those in Miłosz’s The Captive Mind. Some of these stories overlap with one another; some of them are just thin cloaks to cover self-interest. But all of them are familiar justifications of collaboration, recognizable from the past.

Many people in and around the Trump administration are seeking personal benefits. Many of them are doing so with a degree of openness that is startling and unusual in contemporary American politics, at least at this level. As an ideology, “Trump First” suits these people, because it gives them license to put themselves first.

Another sort of benefit, harder to measure, has kept many people who object to Trump’s policies or behavior from speaking out: the intoxicating experience of power, and the belief that proximity to a powerful person bestows higher status.

Cynicism, nihilism, relativism, amorality, irony, sarcasm, boredom, amusement—these are all reasons to collaborate, and always have been. If there is no such thing as moral and immoral, then everyone is implicitly released from the need to obey any rules. If the president doesn’t respect the Constitution, then why should I? If the president can cheat in elections, then why can’t I? If the president can sleep with porn stars, then why shouldn’t I?

“In some parts of the country it does seem like the America that we know and love doesn’t exist anymore.” This is the Vichy logic: The nation is dead or dying—so anything you can do to restore it is justified. Whatever criticisms might be made of Trump, whatever harm he has done to democracy and the rule of law, whatever corrupt deals he might make while in the White House—all of these shrink in comparison to the horrific alternative: the liberalism, socialism, moral decadence, demographic change, and cultural degradation that would have been the inevitable result of Hillary Clinton’s presidency.

Fear, of course, is the most important reason any inhabitant of an authoritarian or totalitarian society does not protest or resign, even when the leader commits crimes, violates his official ideology, or forces people to do things that they know to be wrong. In extreme dictatorships like Nazi Germany and Stalin’s Russia, people fear for their lives. In softer dictatorships, like East Germany after 1950 and Putin’s Russia today, people fear losing their jobs or their apartments. Fear works as a motivation even when violence is a memory rather than a reality. When I was a student in Leningrad in the 1980s, some people still stepped back in horror when I asked for directions on the street, in my accented Russian: No one was going to be arrested for speaking to a foreigner in 1984, but 30 years earlier they might have been, and the cultural memory remained.

Republican leaders don’t seem to know that similar waves of fear have helped transform other democracies into dictatorships. They are scared, and yet they don’t seem to know that this fear has precedents, or that it could have consequences. They don’t know that similar waves of fear have helped transform other democracies into dictatorships. They don’t seem to realize that the American Senate really could become the Russian Duma, or the Hungarian Parliament, a group of exalted men and women who sit in an elegant building, with no influence and no power. Indeed, we are already much closer to that reality than many could ever have imagined.

The price of collaboration in America has already turned out to be extraordinarily high. And yet, the movement down the slippery slope continues, just as it did in so many occupied countries in the past. First Trump’s enablers accepted lies about the inauguration; now they accept terrible tragedy and the loss of American leadership in the world. Worse could follow. Come November, will they tolerate—even abet—an assault on the electoral system: open efforts to prevent postal voting, to shut polling stations, to scare people away from voting? Will they countenance violence, as the president’s social-media fans incite demonstrators to launch physical attacks on state and city officials?

Each violation of our Constitution and our civic peace gets absorbed, rationalized, and accepted by people who once upon a time knew better. If, following what is almost certain to be one of the ugliest elections in American history, Trump wins a second term, these people may well accept even worse. Unless, of course, they decide not to.

In the meantime, I leave anyone who has the bad luck to be in public life at this moment with a final thought from Władysław Bartoszewski, who was a member of the wartime Polish underground, a prisoner of both the Nazis and the Stalinists, and then, finally, the foreign minister in two Polish democratic governments. Late in his life—he lived to be 93—he summed up the philosophy that had guided him through all of these tumultuous political changes. It was not idealism that drove him, or big ideas, he said. It was this: Warto być przyzwoitym—“Just try to be decent.” Whether you were decent—that’s what will be remembered.

11 notes

·

View notes

Note

Cross my heart part 2?

Cross my heart- Part 2

Tommy Shelby x OFC, John Shelby (platonic) x OFC.

A/N: Hope you like this chapter! Sorry if it disappoints.

I’ve gone into the friendship dynamic between John and Eliza a bit more this chapter and of course the drama between Grace and Eliza.

Previous//Next

“Ugh, why do I drink with you again El?” The grunting moans of John were muffled into his pillow.

“Because,” Eliza replied from the other end of the bed, “You’re a borderline alcoholic.”

The night before was a bit blurry, but nothing she wasn’t used to already. Eliza would be lying if she said she hadn’t had her fair share of drunken nights over the years.

To be honest, the night before was relatively tame for her. John and Arthur, however, were a fucking nightmare.

They most definitely were in over their heads in an alcoholic daze.

Which left Tommy and Eliza to heard them back to 6 watery lane.

They’d all fought in the war, seen terrible things no human should have to see. But dear lord- A completely pissed John and Arthur were a completely different type of battle.

Eliza knew from her time in France, that John was difficult to order around when he was completely sober- let alone when he had drunk his body weight in gin.

It took them 35 minutes to get back to the Shelby residence. A trip that would normally take 10 at the very most according to Tommy.

It was awkward to say the least, especially considering their history (of which Tommy couldn’t particularly recall.)

It got worse after that, especially since Eliza followed John to bed.

Now that she thought about it, it looked wrong- going into John’s room while both pair were experiencing an alcohol buzz.

Eliza always assumed that alcohol made the body bolder and flirty. That wasn’t the bloody case though, especially not for John and herself.

Liza had always been told by Harry that she could be wild while drunk, but would end up crashing within 15 minutes.

John on the other hand- questioned everything. From philosophy to why he had to follow Eliza and his brothers back to watery lane. It drove her insane.

So no doubt while Thomas Shelby assumed that his younger brother and the Fenton sister staying up all night fucking- it was actually the opposite, As John asked inquisitive questions through the night and Eliza desperately tried to ignore him as sleep beckoned her on.

“Oi!” John’s voice pulled the girl out of her thoughts about the previous night, “Watch it! Yer’ nearly fuckin’ kicked me in the face.”

Eliza rolled her eyes, and playfully kicked her legs in the direction of John's face.

John who was taken aback by the quick flick to his face and rolled off the side of the bed with a thump. He groaned as he massaged his bottom.

Eliza sat up laughing heartily and threw a pillow at her friend, “You fucking deserve that yer’ daft cunt.”

John threw the pillow back and it hit her square in the face.

The pair locked eye contact for a second before they both bolted.

John clambering down the banister despite his hangover and Eliza with a pillow in hand ready to strike and get her own back.

However, the one thing John had that she lacked, was knowledge of his childhood home.

Eliza rounded the corner at the bottom of the stairwell and SMACK

She had run head-on into an unimpressed Thomas Shelby.

Eliza let out a gasp.

“Shit.”

“Mornin’,” Tommy spoke deeply, he could see the tinted blush spread rapidly across the younger girl’s face.

“Good Morning.” She replied timidly.

“Would you care to explain why you were running in the house- not that eager to escape are yer’?”

“No!” She quickly tried to justify her actions, “I was just erm- running after your brother so I could...” another look of embarrassment flashed across her features, “So I could hit him.” She said lamely.

“Such a ladylike thing to do, aye love.”

That had obviously struck a nerve with Eliza as she raised an eyebrow in retaliation.

“Well, it’s a good fuckin’ thing that Small Heath doesn’t raise polite ladies then, aye Thomas.”

And with that, she turned on her heel and exited the house.

//

By the time Eliza had left watery lane, it was already 9 o’clock. Her body was still drained and Eliza wanted nothing more than to fall back into her own bed and sleep properly (without John pestering her all night).

When the Garrison came into sight again, she rummaged through her coat pocket to find a key for the door.

When she reached it, she was surprised to find the main door unlocked.

Odd she thought to herself, Harry always locks the door before opening hours

Eliza opened the door, creeping through as she kept her guard up. She hadn’t made that much noise- hoping to keep her position secret.

What Eliza hadn’t expected to hear when she entered the pub was a female voice on the telephone.

It was the Irish barmaid, the recipient was talking in the same accent as the blonde- only it sounded like a male.

Eliza craned her head, trying to listen to what was being said.

The pilot never particularly had a reason to listen to someone’s phone call before, but she got a bad feeling from this ‘Grace’ girl.

“No sir, they don’t suspect anything.”

The gruff man on the other end spoke something back.

“Yes- They’re beginning to trust me more. It’s becoming an advantage point.”