#ancient egyptian literature

Text

5: How to treat a wife

If you marry a woman who is plump

and jolly and well known by her townsfolk,

if she is faithful and time is kind to her,

do not be driven apart, but let her eat,

for her jollity brings contentment.

From The Teaching of Ptahhotep, c. 1850 BCE, translated by Toby Wilkinson.

In other translations "frivolous", "wanton" or "of good quality" have been used instead of "plump". Apparently the Egyptian term is unknown, so several translations have been suggested by various scholars.

150 notes

·

View notes

Text

The water is full of vegetation -

Ptah is the reeds.

Sakhmet the lotus shoots.

The goddess of dew is the lotus buds,

and Nefertem the blossoms.

The Memphis Ferry (Papyrus Harris 500) in Hymns, prayers, and songs: An anthology of ancient Egyptian lyric poetry. Translated by John L Foster. p 165.

#ancient egypt#ancient egyptian literature#ancient egyptian poetry#ptah#sekhmet#sakhmet#nefertem#netjer#netjeru#tefnut

104 notes

·

View notes

Text

*reads this*

Wow he's literally me

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

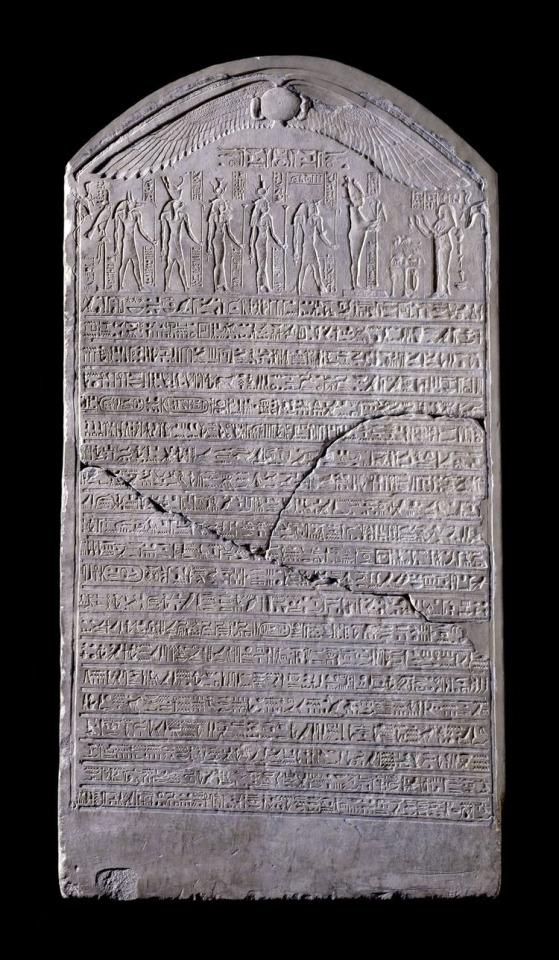

The Lament of Taimhotep

The stela of Taimhotep. Ptolemaic Period (42 BCE). British Museum EA147

On Taimhotep (73-42 BCE) and her funerary stela see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Taimhotep

After the narration of her life (her marriage at the age of fourteen to Psherenptah, the high priest of Ptah in Memphis, the birth of three daughters by him and, after the intervention of the deified Imhotep, the birth of the long-awaited son), Taimhotep laments her untimely death and more generally the situation of the dead, in perhaps the most pessimistic funerary text in the ancient Egyptian literature.

The translation of the part of the stela with Taimhotep’s lament that I reproduce here is from Miriam Lichtheim Ancient Egyptian Literature, vol. III The Late Period, pp 62-64:

O my brother, my husband,

Friend, high priest!

Weary not of drink and food,

Of drinking deep and loving!

Celebrate the holiday,

Follow your heart day and night,

Let not care into your heart,

Value the years spent on earth.

The west, it is a land of sleep,

Darkness weighs on the dwelling-place,

Those who are there sleep in their mummy-forms.

They wake not to see their brothers,

They see not their fathers, their mothers,

Their hearts forgot their wives, their children.

The water of life which has food for all,

It is thirst for me;

It comes to him who is on earth,

I thirst with water beside me!

I do not know the place it is in,

Since (I) came to this valley,

Give me water that flows!

Say to me: “You are not far from water!”

Turn my face to the northwind at the edge of the water,

Perhaps my heart will then be cooled in its grief!

As for death, “Come!” is his name,

All those that he calls to him

Come to him immediately,

Their hearts afraid through dread of him.

Of gods or men no one beholds him,

Yet great and small are in his hand,

None restrain his finger from all his kin.

He snatches the son from his mother

Before the old man who walks by his side;

Frightened they all plead before him,

He turns not his ear to them.

He comes not to him who prays for him,

He hears not him who praises him,

He is not seen that one might give him any gifts.

O you all who come to this graveyard,

Give me incense on the flame,

Water on every feast of the west!

The scribe, sculptor, and scholar; the initiate of the gold house in Tenent, the prophet of Horus, Imhotep, son of the prophet Kha-hapi, justified, has made it.

(Imhotep, son of Kha-hapi was the scribe and sculptor who composed the text and designed the stela -Lichtheim, op. cit., p. 65, note 23).

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

We should bring back the literary classic Eloquent Peasant to describe how we talk on this webbed site compared to others.

4 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hello again. I hope that you are doing well. I also that you could give me your opinion on the meaning, however long or short, on two very different texts. One is the Cannibal Hymn, while the other is the Instruction of Ankhsheshonq. The reason I ask is due to these two texts, in my opinion, being very different than their counterparts and I was hoping to get a few other perspectives on the topics.

Oh, I love the Cannibal Hymn. It's an exceedingly interesting work of parallellism - parallellism, in case you or anyone else reading this isn't aware yet, is a particular and very recognisable style in ancient Egyptian texts, mostly in hymns and especially in Old Kingdom texts. The Cannibal Hymn, also known as Utterances 273 and 274 of the Pyramid Texts and found in the Pyramid of Unas, is considered one of the first advanced examples of this style. Parallellism can range from an entire stanza of lines starting with the same verb or particle, to sentences that are completely similar in structure and only change one or two words.

Personally, I think the Cannibal Hymn, while it's definitely different in terms of mythological allusions, isn't actually an outlier within the ancient Egyptian religious beliefs. Although it talks about how Unas butchers, cooks, and eats the gods, which admittedly doesn't really sound very Egyptian at first glance, it is still part of a ritualistic text corpus concerned with the king's ascendance to heaven and transformation to a god of the sky. And it does also fit with the conditional immortality that the Egyptian gods had - they could and did die, see Osiris.

I'm going to tag @ikchen here for her input, because she is our resident Cannibal Hymn Cat and I want to give her ample space to go wild.

As for the Instructions of Ankhsheshonq, the handwriting is Ptolemaeic, but the contents may date to an earlier period. We don't have a firm dating as far as I know, though it's generally considered to be a Late Period work. I don't have much of an opinion on this apart from the fact that it seems to be relatively similar to other Demotic Instructions we have. In earlier Pharaonic times, Instructions are often highly idealistic, but the moralisation in Ankhsheshonq's is a bit more down to earth. It doesn't really structure its contents by subject the way Pharaonic Instructions do, but again that's not really too out of the ordinary for Demotic texts.

But, since Demotic isn't really my area of study, that's as far as my opinion on this text goes.

#the recaps are for people not familiar with the texts#egyptology#ancient egypt#ancient egyptian literature#cannibal hymn#instruction of ankhsheshonq

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

Prayer to Thoth

Come to me, Thoth, O noble Ibis,

O god who loves Khnum;

O letter-writer of the Ennead,

Great one who dwells in Un!

Come to me and give me counsel,

Make me skillful in your calling;

Better is your calling than all callings,

It makes (men) great.

He who masters it is found fit to hold office,

I have seen many whom you have helped;

They are now among the Thirty,

They are strong and rich through your help.

You are he who offers counsel,

Fate and Fortune are with you,

Come to me and give me counsel,

I am a servant of your house.

Let me tell of your valiant deeds,

Wheresoever I may be;

Then the multitudes will say:

“Great are they, the deeds of Thoth!”

Then they’ll come and bring their children,

To assign them <to> your calling,

A calling that pleases the lord of strength,

Happy is he who performs it!

M. Lichtheim, (2006), Ancient Egyptian Literature, Vol. II: The New Kingdom, London, p. 113; P. Anastasi V. 9.2-10.2

#Egyptology#Kemetic#Thoth#Djehuty#Ancient Egyptian Literature#New Kingdom texts#I really like this one#and it's relevant with semester starting again in under a month#I've seriously neglected my studies over break#maybe some divine help to get back into it would be helpful

162 notes

·

View notes

Text

A love poem from an anthology of literature of Ancient Egypt

I am sailing downstream on the ferry

By the hand of the helmsman

With my bundle of reeds on my shoulder

I am bound for Ankh-Tawy

And I shall say to Ptah, Lord of Ma’at

Grant me my beloved this night

The river is wine

Ptah is its reeds

Sekhmet is its lotus leaf

Iadet is its lotus bud

Nefertum is its lotus flower

There is rejoicing in the land as it brightens in its beauty

Memphis is a bowl of Mandrakes

Laid before the god who is beauteous of face

64 notes

·

View notes

Text

1 note

·

View note

Video

youtube

A stick figure animation of the ancient Egyptian tale "The Report of Wenamun". Animation by me and backgrounds by my friend.

#The Report of Wenamun#Wenamun#ancient Egypt#Egypt#ancient Egyptian literature#animation and all figures by me#I had a few late nights to get this for Monday

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

"My love is one and only, without peer, lovely above all Egypt's lovely girls.

On the horizon of my seen, see her, rising,

Glistening goddess of the sunrise star bright in the forehead of a lucky year.

So there she stands, epitome of shining, shedding light,

Her eyebrows, gaming darkly, marking eyes which dance and wonder.

Sweet are those lips, with chatter - but never a word too much -

And the line of the long neck lovely, dropping - since song's notes slide that way -

To young beasts firm in the bouncing light with shimmers that blue shadowed sidewall of hain.

And slims are those arms, overtoned with gold, those fingers which touch like a brush of Lotus.

And - oh - how the curve of her back slips gently by a whisper of waist to God's plenty below."

Love song, Ramesside period (1292-1070 BC ca.)

#Egyptologist#Egypt#Egyptian literature#Ancient Egyptian literature#Ancient Egyptian poetry#Poetry#Literature#Ancient Egypt#Kmt#Kemet#Love#Love song#Song#Archaeology#Archaeologist#Near East#ramses#ramesse#lovely#in love#ancient literature#ancient lit#near eastern literature

24 notes

·

View notes

Note

Two things. First, do you happen to have or know of a list of the available sebayt? Second, do you have a favorite sebayt that you like to read?

I looked, and can’t easily find a comprehensive list of the Egyptian wisdom texts, so I made one (in roughly chronological order). I’ve emphasised the ones that fall into the specific subgenre “instructions”, but all of them are wisdom texts in the broadest sense of the genre - i.e. texts that seek to impart a particular wisdom upon the reader.

Old Kingdom

The Instruction of Prince Hordjedef

The Instruction Addressed to Kagemni

The Instruction of Ptahhotep

First Intermediate Period

The Instruction Addressed to King Merikare

Middle Kingdom

The Teachings of Amenemhat I for His Son Senwosret I

The Prophecies of Neferti

The Complaints of Kakheperre-seneb

The Admonitions of Ipuwer

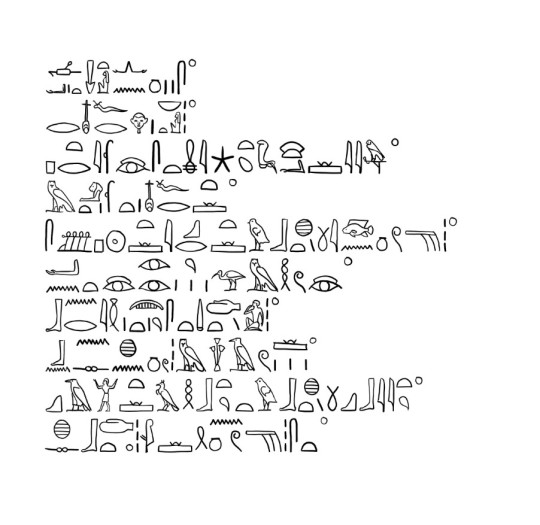

Dispute Between a Man and His Ba

The Eloquent Peasant

The Satire of the Trades

New Kingdom

The Instruction of Any

The Instruction of Amenemope

Papyrus Lansing

The Immortality of Writers

Late Period (Demotic texts)

The Instruction of Ankhsheshonq

The Instruction of Papyrus Insinger

My favourite wisdom text is The Teachings of Amenemhat I. It’s not only a gorgeous papyrus with incredibly nice handwriting, but a very poetic text as well.

#egyptology#wisdom texts#ancient egyptian literature#sebayt#ancient egypt#anon asks#this is exhaustive afaik but disclaimer: wrote it with a baby strapped to my chest#if I think of any I may have missed (I don't think so but again - baby brain) I will add them

64 notes

·

View notes

Text

New Post has been published on Goddess Isis

New Post has been published on http://goddessisis.net/tale-of-the-eloquent-peasant/

Tale of the Eloquent Peasant

What is so lovely about the Tale of the Eloquent Peasant is that it describes how ancient Egyptian law was like for the common man. So much of what we know about ancient Egypt comes to us from the tombs of elites and other great monuments – which are more of a testament to the lives of the rich and powerful.

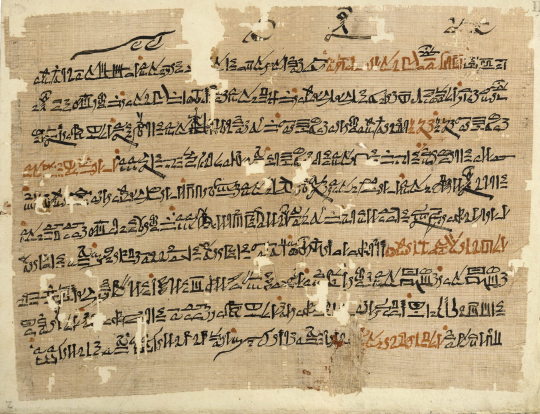

The Tale of the Eloquent Peasant was written in hieratic script on papyri that are now held in the British Museum and the Royal Library in Berlin.

The pharaoh in the story is thought to be King Nebkaure Khety of the Fourth Dynasty. The story itself is thought to have come later, sometimes around the Twelfth Dynasty, and is set in the town of Herakleopolis, near modern day Beni Suef.

Tale of the Eloquent Peasant Papyrus from the British Museum Website

tale of the eloquent peasant

The peasant Hunanup decided to go down to Egypt to bring back bread for his children. He asked his wife to divide up the grain, keeping some for her and the children and preparing the rest as beer and bread to sustain Hunanup on his travels.

He loaded up his donkeys and left his town to go to Herakleopolis.

On his journey, he crossed the path of a man named Dehuti-nekht, a serf of the chief steward Meruitensi.

Dehuti-nekht, seeing the donkeys loaded with these goods, felt the temptation to rob the peasant Hunanup.

Dehuti-nekht’s house was nearby, and the narrow path the peasant had to cross had water to one side and the estate’s grain crops on the other side.

Dehuti-nekht shouted to one of his servants to get him a shawl, which he spread on the middle of the road, from the edge of the water up until the pile of grain, blocking the way.

As the peasant came up close to it, Dehuti-nekht said to him “Look out, peasant, do not trample on my clothes!” The peasant Hunanup steered away from the shawl and found himself on top of the grain crops, where his donkey ate a mouthful of it.

Then Dehuti-nekht said “See, I will take away your donkey because it has eaten my grain.”

Hunanup understood what Dehuti-nekht was trying to do, and objected by saying that the chief steward Meruitensi punishes all thieves – implying that Dehuti-nekht is trying to rob him. Angered by this, Dehuti-nekht took the donkeys and beat Hunanup until he wept.

After four days of crying and pleading with Dehuti-nekht to give him back his donkeys and goods, Hunanup decided to seek out the chief steward Meuitensi. He managed to get a message through to him recounting the whole ordeal.

Meuitensi and his officials reviewed the case, with the peasant Hunanup in their presence. After some time of silence, the peasant decided to speak up for himself:

“Chief steward, my lord, you are greatest of the great, you are guide of all that which is not and which is. When you embark on the sea of truth, that you may go sailing upon it, then shall not the (?) strip away your sail, then your ship shall not remain fast, then shall no misfortune happen to your mast then shall your spars not be broken, then shall you not be stranded – if you run fast aground, the waves shall not break upon you, then you shall not taste the impurities of the river, then you shall not behold the face of fear, the shy fish shall come to you, and you shall capture the fat birds. For you are the father of the orphan, the husband of the widow, the brother of the desolate, the garment of the motherless. Let me place your name in this land higher than all good laws: you guide without avarice, you great one free from meanness, who destroys deceit, who creates truthfulness. Throw the evil to the ground. I will speak hear me. Do justice, O you praised one, whom the praised ones praise. Remove my oppression: behold, I have a heavy weight to carry; behold, I am troubled of soul; examine me, I am in sorrow.”

Meruitensi found the peasant’s speech so eloquent that he passed him onto another officer, who passed him onto another and another. Hunanup began to grow tired, making speech after speech, and during his eighth speech, he insulted the chief steward.

Meruitensi punished Hunanup, who had left after trying to undo his insults with a ninth speech that was much more pleasing.

But Hunanup was sent for again, and he feared that he was being brought back to be punished, but Meruitensi assured him this wasn’t the case.

Meruitensi had the speeches and tale of the Eloquent Peasant Hunanup from the entire nine days written on scrolls. He sent them to the pharaoh, King Nebkaure. The king found them so beautiful that he sent word back to the chief steward Meruitensi to pass the sentence himself. Meruitensi decided to take goods selected from Dehuti-nekht’s possessions and give them to Hunanep, who then went home rejoicing.

This was my adaptation of George A. Barton’s translation of the Tale of the Eloquent Peasant. An original translation can be found here.

If you liked this page, Sign up for free to keep up to date on the newest content

Return from Tale of the Eloquent Peasant to Ancient Egyptian Literature

Return from Tale of the Eloquent Peasant to the EAE Home Page

0 notes

Text

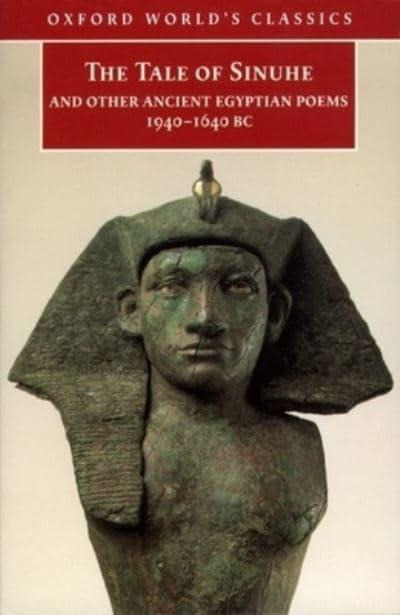

The Tale of Sinuhe - Oxford World's Classics

R. B. Parkinson

Paperback (10 Jun 1999)

2 notes

·

View notes

Quote

My one, the sister without peer,

The handsomest of all!

She looks like the rising morning star

At the start of a happy year.

Shining bright, fair of skin,

Lovely the look of her eyes,

Sweet the speech of her lips,

She has not a word too much.

Upright neck, shining breast,

Hair true lapis lazuli;

Arms surpassing gold,

Fingers like lotus buds.

Heavy thighs, narrow waist,

Her legs parade her beauty;

With graceful step she treads the ground,

Captures my heart by her movements.

She causes all men's necks

To turn about to see her;

Joy has he whom she embraces,

He is like the first of men!

When she steps outside she seems

Like that the Sun!

Part of a poem from the Chester Beatty Egyptian Papyrus I from the Ramesside era, but based on older fragments from the Middle Kingdom.

9 notes

·

View notes