#after barely representing craiglockhart

Text

watched the sass movie and didnt like it but i have the violent need to talk shit abt it to my thesis director

#i just think that sass deserved to do more than#argue w a revolving door of cruel lovers#and never brought up his war exp#except in generic footage#and that his poetry should have been better selected#or really just#everyone sang should be in there#giving wilfred owen the last word in a siegfried sassoon biopic#after barely representing craiglockhart#OOF.#arms and the bri

0 notes

Text

Wilfred Owen: the man not the memorial

All a poet can do today is warn.

- 2nd Lieutenant Wilfred Edward Salter Owen MC (1893-1918)

The body of Wilfred Owen’s work is generally regarded as a memorial to the atrocities of war. Often heralded as one of the finest poets of the First World War, Wilfred Owen has become a symbol to many of 1914-1918 encapsulating a sense of futility (the title one of his more famous poems), anger, and despair at the suffering endured by the soldiers during the Great War, or indeed any war before and after.

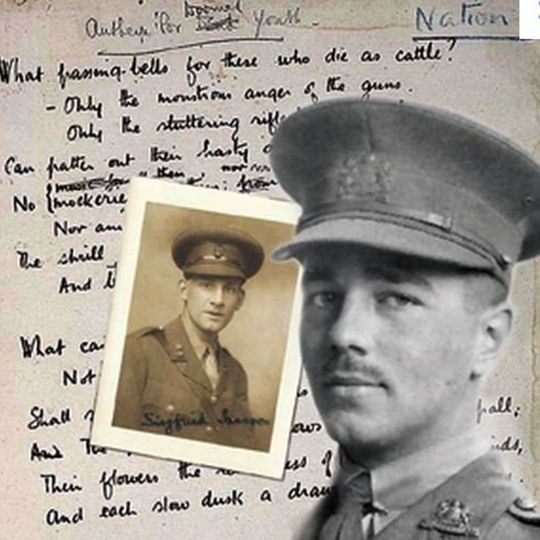

Poems like ‘Anthem for Doomed Youth’ convey the intense futility of it all, for “what passing-bells for these who die as cattle?”, whilst he evokes the disturbing psychological impact of the fighting in works like ‘Mental Cases’ where “these are the men whose minds the Dead have ravaged”. The canonisation of such works has preserved Owen as a symbol of the First World War and a reminder of its horrors.

This is not without challenge of course. Owen’s was only one voice representing one point of view and cannot be seen to capture the myriad of views and feelings of all the combatants and his generation, but at the same time that is not sufficient reason to dismiss his work as irrelevant to the study of the War.

More interesting to me is the feeling that Owen’s poetic legacy has put aside the man that was Wilfred Owen. Every schoolchild knows at least one of his poems but know very litte of his life as a man and as a soldier. It is easy to forget that he too was a flesh and blood man fighting in the trenches, with his own hopes and fears, uncertainties and complexities.

Born in 1893, Owen was teaching English to children near Bordeaux, France, when war broke out in the summer of 1914. The following year, he returned to England and enlisted in the war effort. On 21 October 1915, he enlisted in the Artists Rifles Officers' Training Corps. For the next seven months, he trained at Hare Hall Camp in Essex. On 4 June 1916 he was commissioned as a second lieutenant (on probation) in The Manchester Regiment. By January 1916 he was on the front lines in France. As he wrote in 1918, his motives for enlisting were twofold, and included his desire to write of the experience of war: “I came out in order to help these boys - directly by leading them as well as an officer can; indirectly, by watching their sufferings that I may speak of them as well as a pleader can.”

On April 1, 1917, near the town of St. Quentin, Owen led his platoon through an artillery barrage to the German trenches, only to discover when they arrived that the enemy had already withdrawn. Severely shaken and disoriented by the bombardment, Owen barely avoided being hit by an exploding shell, and returned to his base camp confused and stammering.

A doctor diagnosed shell-shock, a new term used to describe the physical and/or psychological damage suffered by soldiers in combat. Though his commanding officer was skeptical, Owen was sent to a French hospital and subsequently returned to Britain, where he was checked into the Craiglockhart War Hospital for Neurasthenic Officers in Scotland in 1917. There he was officially diagnosed as suffering from neurasthenia (‘shell-shock’).

It was there he famously met Siegfried Sassoon and his poetry took on a new direction and life. Owen spent the first part of 1918 in England training and recuperating. He did a short spell working as a teacher in nearby Tynecastle High School, he returned to light regimental duties. In March 1918, he was posted to the Northern Command Depot at Ripon. A number of poems were composed in Ripon, including "Futility" and "Strange Meeting". His 25th birthday was spent quietly in Ripon Cathedral.

In recent years much work has been done to restore Owen’s humanity, most notably Dominic Hibberd’s 2002 work Wilfred Owen: A New Biography, which, whilst clearing up other details of Owen’s life, confirms that he was gay. On one level that shouldn’t matter. But interestingly facts like this could cast some of his poetry in a new light, with particular regard to the vivid and sometimes shocking sensuality and even excitement that is undoubtedly present in poems like ‘The Sentry’, where “thud! flump! thud! down the steep steps came thumping/ And splashing in the flood, deluging muck”. An idea of the attractiveness and lure of war could possibly develop from this interpretation, particularly as Owen, like his friend Siegfried Sassoon, returned to the front line after absence.

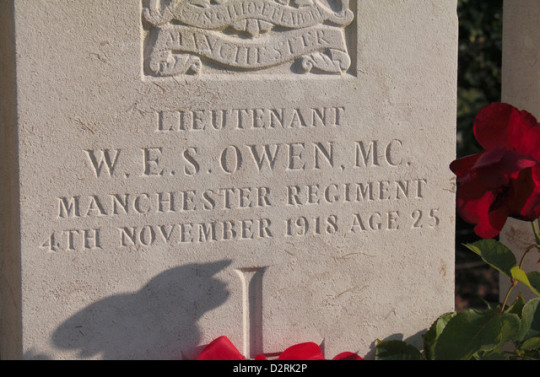

Indeed whilst Owen's work rises above that of many contemporary poets, the circumstances surrounding his death at such a young age (25), and the news of his death, has added to the powerful emotions that surround Owen. Rejecting offers by his friends to pull strings and arrange for him to sit out the rest of the war Owen chose to return to the front to help the men he felt he had left behind. Owen’s battalion was part of the spearhead used to break the final German defensive line after a series of Allied advances following success at Amiens in August 1918. On 1 October 1918, Owen led units of the Second Manchester's to storm a number of enemy strong points near the village of Joncourt. For his courage and leadership in this action, he was awarded the Military Cross.

Owen was killed in action on 4 November 1918 during the crossing of the Sambre–Oise Canal, exactly one week (almost to the hour) before the signing of the Armistice which ended the war, and was promoted to the rank of Lieutenant the day after his death. A key problem was to overcome the Sambre canal defences and gain the Eastern bank, and on 4th November at 5.45am Owen was involved in the attempt to cross. The exact details of that morning are hazy, and all that is known is that Owen was seen leading and encouraging his men in the early part of the struggle, but was killed, possibly as he crossed the water on a raft, sometime between 6 and 8.00am. Famously the telegram notifying his family of his death arrived mid-day on November 11th as the celebrations around the Armistice rang out.

These are facts known to all of us. But what I found really eye opening was going to the place where he spent his last night before his death. It puts a different perspective on Wilfred Owen, not the poet, but the man and the officer who cared deeply for his men under his command.

Owen and his platoon had spent the previous night in the cellar of a Forester’s House in the wood outside Ors. Ors is mere two hours’ drive from Calais in the Nord-Pas de Calais region. It’s a small village and if you walk across the canal you can church bells tolling. To right and left the countryside resembles a French Impressionist painting. The waterway is lined with tall, leafy Poplar trees; there are meadows full of cattle, the hills beyond roll into the distance - an idyllic scene, glowing in the spring sunlight. It’s hard to conceive of the ghastly sights, sounds and smells that once shattered this tranquil landscape.

When I was driving with friends around there we visited key sites that marked the First World War. When we got to Ors we came across Forester’s House, now a memorial to Wilfred Owen. We were told by that by some villagers that a great number of British visitors came looking for Owen’s grave and the exact spot where he had been killed, and asking to visit the cellar of the Forester’s house. And so a grassroots campaign amongst locals began to raise funds to commemorate Wilfred Owen properly. British artist Simon Patterson along with French architect Jean-Christophe Denise took seven years to design a suitable memorial - by re-designing the building into a place for reflection and meditation - which eventually opened in 2011.

The tiny cellar remains bare and untouched, but the 18th century house above has been transformed into a 21st century sculptural object, its entire brick facade painted stark white to resemble bleached bone, the original roof encased and glazed to form a face-down open book. The gutted interior is now a sanctuary, lined by translucent glass panels, each etched with fragments of original text from Wilfred Owen’s best-known and much-loved works, complete with his corrections, scribbles and crossings-out. The drafts bear testament to the poet’s struggle with the barbaric absurdity of war: “My subject is War, and the pity of War.” Included are lines from Dulce et Decorum Est, Anthem for Doomed Youth, The Dead Beat, Strange Meeting, and Spring Offensive; each poem backlit by waves of coloured lights activated by the recorded voice of actor Kenneth Branagh playing inside the room. Branagh’s stirring readings pitch the poems across the open space. They rise and fall from the walls and reverberate around the roof lights, before flowing out into the l’Évêque forest beyond.

It’s an impressive memorial and a powerful place, made all the more effective by being so simple. Unlike other war museums, there are no artefacts, no tanks, no weapons or uniforms. It was created as: “a quiet place that is suitable for reflection and the contemplation of poetry,” gently glorifying the art that has come out of the chaos and tragedy of war.

It’s all the more remarkable that the local French took the initiative because Owen was pretty much unknown in France - but today his poetry has been translated into French for schoolchildren to learn and reflect upon the pity of war.

We visited the cellar and I tried to imagine what Owen’s last night was like. I could empathise from my own experience of the battlefield out in Afghanistan waiting to leave on a night time or day time mission in my helicopter. As any soldier will tell you, everyone has their own coping mechanism to deal with the pre-mission nerves and unspoken anxieties. Some hide it better than others. I tried to imagine Wilfred Owen’s state of mind.

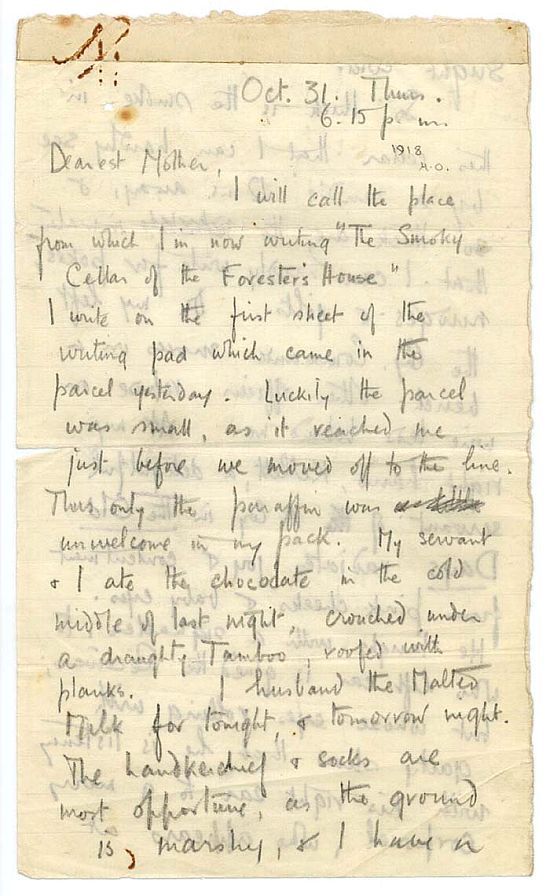

Thankfully we can have a good idea because he wrote a letter. Billeted in the cramped, smoke-filled cellar of a forester’s house in woods near Ors in late October 1918, Owen took time to write to his mother. His mother was to receive his letter on 11 November, 1918, the day the Armistice was declared, along with a telegram informing Susan and Tom Owen that their beloved son had died in action seven days earlier. The words of that last letter home are carved now into the stone wall of a curved walkway that leads to the brick-lined cellar of the forester’s house.

Entering the cellar, you are struck by how crowded it must have been that night when 29 soldiers were holed up here, smoking like chimneys. As you begin to absorb the surrounding a recording begins of Kenneth Branagh reading Owen’s last letter to his mother. It is observant, amusing - and deeply moving. Owen’s letter was designed to reassure his mother, saying nothing about the impending attack, but instead poking fun at his comrades that he cared deeply about.

To Susan Owen

Thurs. 31 October [1918] 6:15 p.m.

[2nd Manchester Regt.]

Dearest Mother,

I will call the place from which I’m now writing ‘The Smoky Cellar of the Forester’s House’. I write on the first sheet of the writing pad which came in the parcel yesterday. Luckily the parcel was small, as it reached me just before we moved off to the line. Thus only the paraffin was unwelcome in my pack. My servant & I ate the chocolate in the cold middle of last night, crouched under a draughty Tamboo, roofed with planks. I husband the Malted Milk for tonight, & tomorrow night. The handkerchief & socks are most opportune, as the ground is marshy, & I have a slight cold!

So thick is the smoke in this cellar that I can hardly see by a candle 12 ins. away, and so thick are the inmates that I can hardly write for pokes, nudges & jolts. On my left the Company Commander snores on a bench: other officers repose on wire beds behind me. At my right hand, Kellett, a delightful servant of A Company in The Old Days radiates joy & contentment from pink cheeks and baby eyes. He laughs with a signaller, to whose left ear is glued the Receiver; but whose eyes rolling with gaiety show that he is listening with his right ear to a merry corporal, who appears at this distance away (some three feet) nothing [but] a gleam of white teeth & a wheeze of jokes.

Splashing my hand, an old soldier with a walrus moustache peels & drops potatoes into the pot. By him, Keyes, my cook, chops wood; another feeds the smoke with the damp wood.

It is a great life. I am more oblivious than alas! yourself, dear Mother, of the ghastly glimmering of the guns outside, & the hollow crashing of the shells.

There is no danger down here, or if any, it will be well over before you read these lines.

I hope you are as warm as I am; as serene in your room as I am here; and that you think of me never in bed as resignedly as I think of you always in bed. Of this I am certain you could not be visited by a band of friends half so fine as surround me here.

Ever Wilfred x

At dawn on 4th November 1918, the bodies of hundreds of soldiers littered these fields. Bludgeoned, blinded, blown to smithereens, their hopes and dreams ended in the first minutes of brutal engagement as they floundered through a blasted land, thick with mud, blood and the gory detritus of war. They lost their lives horribly in a futile attempt to claim a few extra inches on the map of Europe at a time when both sides knew the First World War was over, and to carry on fighting was a cynical, cruel waste of time and the lives of men wanting to go home alive to their loved ones.

After the action, shocked survivors found a pair of standing bodies - an English Tommy and a German Fritz - welded face-to-face in death by the impact of their bayonet charge. On that day, England lost more than its fair share of brave men. In their midst lay a poetic genius whose compassionate and skilful writing still stirs the souls and breaks the hearts of millions of readers almost a hundred years after his death. After all these years, Wilfred Owen’s bleak words: “I am the enemy you killed, my friend,” continue to carry across borders and speak to nations about the foolishness of war - its horror, grief and waste - and the terrible impact warfare still has on the world today. Second Lieutenant Wilfred Edward Salter Owen MC now lies alongside 30 of his fellow soldiers buried beneath pristine rows of crisp white headstones inside the compact War Graves Commission Cemetery at Ors.

Any doubts of Wilfred Owen’s incredible bravery arising from his mental breakdown in 1917 can be quickly dispelled by his decision to go back to France. It is this little detail that is so often overlooked that truly lends pathos to the war poetry of Wilfred Owen. This is central to Owen’s complex identity that is lost by the reductive perspective of him as this mythic anti-war herald, and not as a man of immense sacrificial courage and an unspoken sense of personal duty to others.

Owen is not the only poet of the war era to suffer this arguable ‘dehumanisation’. Of course it is important to recognise what these figures reveal about war and its impact, but we must not lose sight of the men behind the symbols and thereby rob them of their humanity and thus their very human sacrifice. When we remember those who have lost their lives, our thoughts must be of the men, not just the memorials.

#wilfred owen#owen#poet#poetry#first world war#war#great war#remembrance#remembrance sunday#armistice day#britain#british army#france#soldier#battle#memorial#commemoration

132 notes

·

View notes