#Princeton battlefield

Text

Tree with carvings in it at the Princeton Battlefield State Park in Princeton, NJ.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

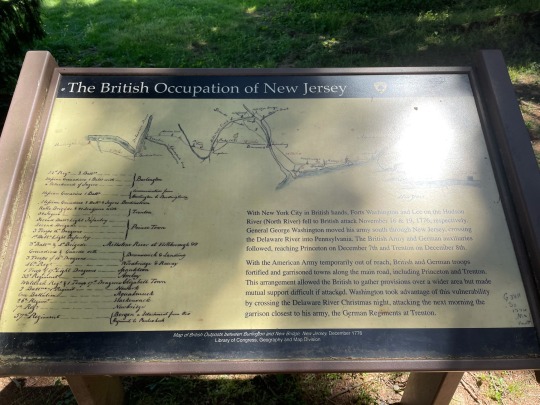

The Cheshire Regiment takes Princeton!

Wonderful, if exceedingly Damp, time with the regiment today. Normal people definitely get up at 6am on a Sunday just to march around in 30-something degree weather and get alternatively rained/sleeted/snowed upon (and enjoy it!). Weather cleared up beautifully as soon as we were not on the battlefield, as seen pictured here, outside Nassau Hall.

Allegedly, during the Battle of Princeton, Alexander Hamilton fired a cannonball right through the Hall (which was occupied by British forces), which "decapitated" a portrait of George II inside. No saying how true that is, but it is certainly a fun legend. Historically this was a Continental victory, but this redcoat had fun nonetheless.

#love this picture of the lads#one of our guys knows princeton really well and gave us the Post-Tavern Revolutionary Walking Tour of the campus#I love these guys#god save the cheshire regiment#this is your captain speaking#battle of princeton#awi#historical reenactment

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

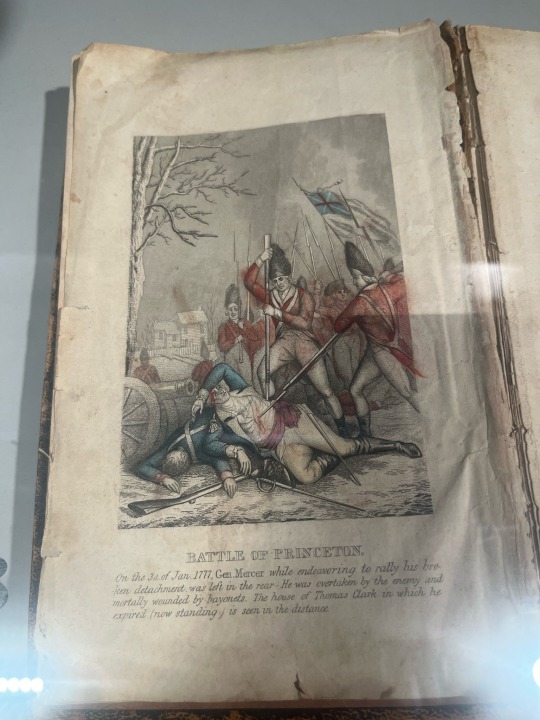

Brigadier General Hugh Mercer died on January 12th 1777 after being wounded at the Battle of Princeton.

Historians argue that, had it not been for his untimely and grisly death at the Battle of Princeton in 1777, Hugh Mercer, born in Aberdeenshire, would have been a greater leader than Washington and would rank as one of the greatest American heroes of all time.

Born on January 17h, 1726, at the manse of Pitsligo Kirk in Roseharty, Scotland, Hugh Mercer was the son of Reverend William Mercer and his wife Ann. At the age of 15, he left home to attend Marischal College at the University of Aberdeen to study medicine. Graduating as a doctor, he practiced locally until the arrival of Prince Charles Edward Stuart and the beginning of the 1745 Jacobite Uprising.

Rallying to the Prince’s colours, Mercer became an assistant surgeon in the Jacobite Army. He remained in this service until the Battle of Culloden. Mercer was forced to flee Scotland for America in 1747. Arriving in Philadelphia, he settled on the Pennsylvania frontier and returned to practising medicine. by 1758 he was, like many Scots who fled, serving in the British army, battling Shawnee and Delaware Indians, Mercer and his men took part in Lt. Colonel John Armstrong’s raid on Kittanning on September 8th, 1756. and became separated from his men. Alone following the battle, he made his way 100 miles on foot back to Fort Shirley where he received medical attention and was heralded a hero and promoted to the rank of Captain, it was here that Mercer was to become good friends with a man that would shape the remaining years of his life, also a Colonel at the time, his name was George Washington.

Before you start questioning his loyalty with being in the British army remember Washington was also in their pay at this time. After the 7 year war he settled back into private practice but 15 years later was elected as a Colonel of the Minute Men of Spotsylvania a Militia that would play an important part in the American Revolution, he had initially excluded from the elected leadership and branded a “northern Briton,” later being appointed Colonel in the Virginia Line part of the Continental Army which rose in revolt against British rule after the outbreak of the American Revolutionary War, once again he was fighting against “the auld enemy”.

One of the officers under Mercer was future president James Monroe. He rode through the ranks to Brigadier General distinguishing himself and involving himself with George Washington battle plans until January 3rd while on their way to The Battle of Princeton leading a vanguard of 350 soldiers, Mercer’s brigade encountered two British regiments and a mounted unit. A fight broke out at an orchard grove and Mercer’s horse was shot from under him. Getting to his feet, he was quickly surrounded by British troops who mistook him for George Washington and ordered him to surrender. Outnumbered, he drew his saber and began an unequal contest. He was finally beaten to the ground, then bayoneted repeatedly—seven times—and left for dead.

When Washington learned of the British attack and saw some of Mercer’s men in retreat, he himself entered the fray. Washington rallied Mercer’s men and pushed back the British regiments, but Mercer had been left on the field to die with multiple wounds to his body and blows to his head. (Legend has it that a beaten Mercer, with a bayonet still impaled in him, did not want to leave his men and the battle and was given a place to rest on a white oak tree’s trunk, while those who remained with him stood their ground. The tree became known as “the Mercer Oak” and is the key element of the seal of Mercer County, New Jersey.

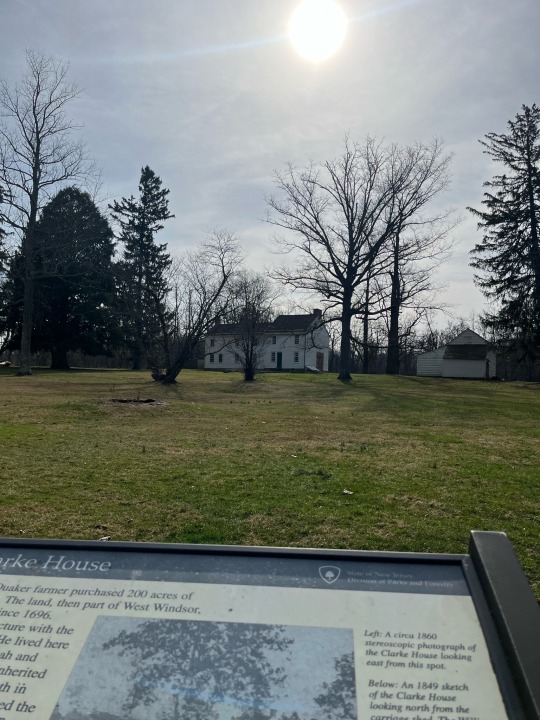

When he was discovered, Mercer was carried to the field hospital in the Thomas Clarke House (now a museum) at the eastern end of the battlefield. In spite of medical efforts by Benjamin Rush, Mercer was mortally wounded and died nine days later on January 12, 1777.

In 1840 he was re-buried at Philadelphia’s Laurel Hill Cemetery. Because of Mercer’s courage and sacrifice, Washington was able to proceed into Princeton and defeat the British forces there. He then moved and quartered his forces to Morristown in victory.

The second picture show a painting entitled George Washington at Battle of Princeton features in the foreground Hugh Mercer lying mortally wounded in the background, supported by Dr. Benjamin Rush and Major George Lewis holding the American flag. This portrait is the prize possession of Princeton University.

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

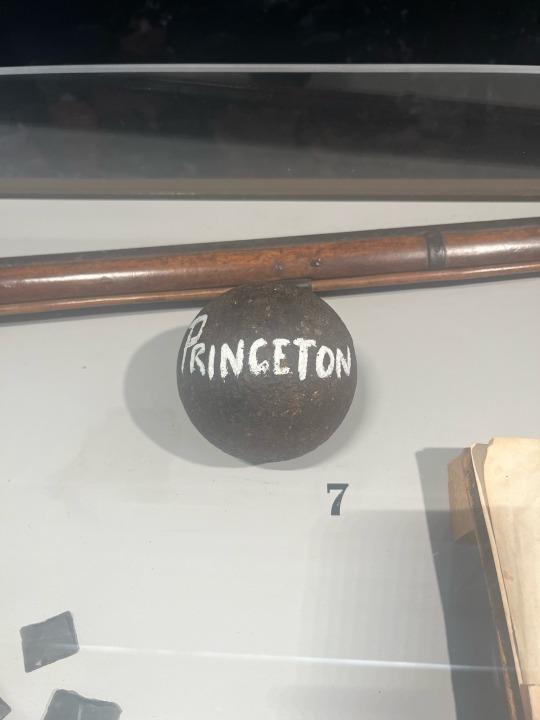

This week I visited the Thomas Clarke House on Princeton Battlefield State Park! If you’re interested in learning about the Jersey Campaigns of 1776 and ‘77, I highly recommend visiting! Their exhibit is nicely done— my favorite parts were the paintings of the campaign I hadn’t seen before (the Crossing one) and the original part of the house where General Hugh Mercer died after the Battle of Princeton. Check it out if you can!

#I was gonna write something really long and go insane but I will do that in a separate post#like. AHHH.#AHHHHHHHHHHHHHH#I love you battlefields I love you battlefields I LOVE YOU BATTLEFIELDS#amanda speaks#american revolution#american history#military history#revolutionary road trips#HUGH MERCER HIVE

9 notes

·

View notes

Photo

New Releases for the Week of June 13, 2022

Here are a few new releases coming your way this week--

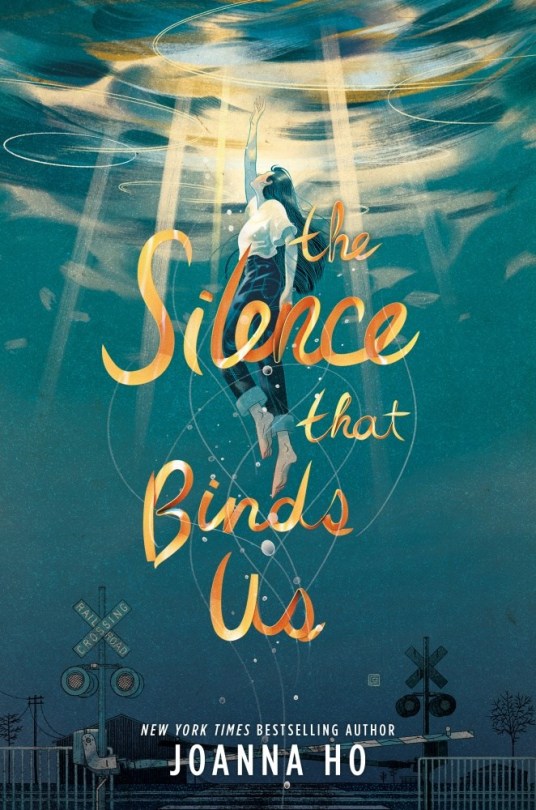

The Silence That Binds Us by Joanna Ho

HarperTeen

Maybelline Chen isn’t the Chinese Taiwanese American daughter her mother expects her to be. May prefers hoodies over dresses and wants to become a writer. When asked, her mom can’t come up with one specific reason for why she’s proud of her only daughter. May’s beloved brother, Danny, on the other hand, has just been admitted to Princeton. But Danny secretly struggles with depression, and when he dies by suicide, May’s world is shattered.

In the aftermath, racist accusations are hurled against May’s parents for putting too much “pressure” on him. May’s father tells her to keep her head down. Instead, May challenges these ugly stereotypes through her writing. Yet the consequences of speaking out run much deeper than anyone could foresee. Who gets to tell our stories, and who gets silenced? It’s up to May to take back the narrative.

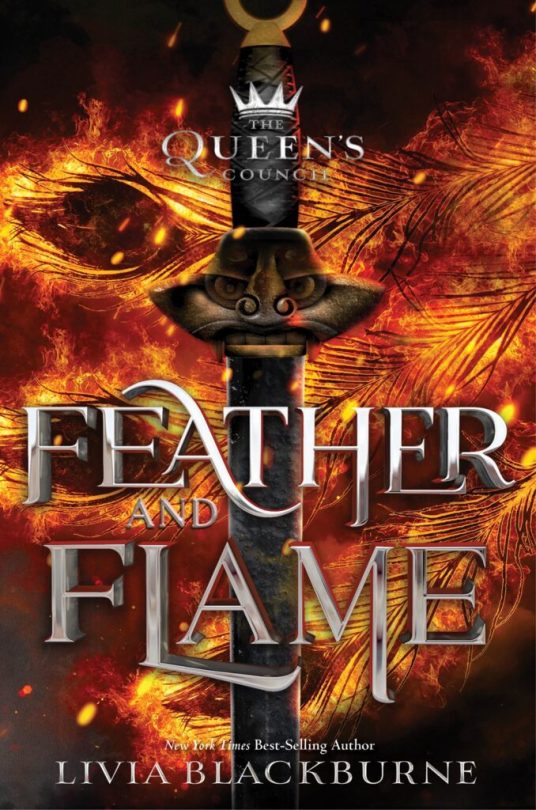

Feather and Flame by Livia Blackburne

Disney Hyperion

She brought honor on the battlefield. Now comes a new kind of war…

The war is over. Now a renowned hero, Mulan spends her days in her home village, training a militia of female warriors. The peace is a welcome one, and she knows it must be protected.

When Shang arrives with an invitation to the Imperial City, Mulan’s relatively peaceful life is upended once more. The aging emperor decrees that Mulan will be his heir to the throne. Such unimagined power and responsibility terrifies her, but who can say no to the Emperor?

As Mulan ascends into the halls of power, it becomes clear that not everyone is on her side. Her ministers undermine her, and the Huns sense a weakness in the throne. When hints of treachery appear even amongst those she considers friends, Mulan has no idea whom she can trust.

But the Queen’s Council helps Mulan uncover her true destiny. With renewed strength and the wisdom of those that came before her, Mulan will own her power, save her country, and prove once again that, crown or helmet, she was always meant to lead. This fierce reimagining of the girl who became a warrior blends fairy-tale lore and real history with a Disney twist.

The Loophole by Naz Kutub

Bloomsbury YA

Sy is a timid seventeen-year-old queer Indian-Muslim boy who placed all his bets at happiness on his boyfriend Farouk…who then left him to try and “fix the world.” Sy was too chicken to take the plunge and travel with him and is now stuck in a dead-end coffee shop job. All Sy can do is wish for another chance…. Although he never expects his wish to be granted.

When a mysterious girl slams into (and slides down, streaks of make-up in her wake) the front entrance of the coffee shop, Sy helps her up and on her way. But then the girl offers him three wishes in exchange for his help, and after proving she can grant at least one wish with a funds transfer of a million dollars into Sy’s pitifully struggling bank account, a whole new world of possibility opens up. Is she magic? Or just rich? And when his father kicks him out after he is outed, does Sy have the courage to make his way from L. A., across the Atlantic Ocean, to lands he’d never even dreamed he could ever visit? Led by his potentially otherworldly new friend, can he track down his missing Farouk for one last, desperate chance at rebuilding his life and re-finding love?

13 notes

·

View notes

Link

0 notes

Text

Works Cited

Abdullah Frères (Ottoman, 1858–1899). Album of Photographs of Views of the Interior of the Ottoman Military Museum in the Former Church of St. Irene, Constantinople (Vues de Sainte Irène, Constantinople). 1891. Albumen prints, paper, leather, textile, gold, L. 17 3/4 in. (45.1 cm); H. 13 in. (33.0 cm); W. 2 3/8 in. (6.0 cm). Album of Photographs of Views of the Interior of the Ottoman Military Museum in the Former Church of St. Irene, Constantinople (Vues de Sainte Irène, Constantinople) [2016.649]. The Metropolitan Museum of Art. https://jstor.org/stable/community.34623840.

Abdullah Frères (Ottoman, 1858–1899). Album of Photographs of Views of the Interior of the Ottoman Military Museum in the Former Church of St. Irene, Constantinople (Vues de Sainte Irène, Constantinople). 1891. Albumen prints, paper, leather, textile, gold, L. 17 3/4 in. (45.1 cm); H. 13 in. (33.0 cm); W. 2 3/8 in. (6.0 cm). Album of Photographs of Views of the Interior of the Ottoman Military Museum in the Former Church of St. Irene, Constantinople (Vues de Sainte Irène, Constantinople) [2016.649]. The Metropolitan Museum of Art. https://jstor.org/stable/community.34623835.

Ágoston, Gábor, HABSBURGS AND OTTOMANS: Defense, Military Change and Shifts in Power.

Ágoston, Gábor, Firearms and Military Adaptation: The Ottomans and the European Military Revolution, 1450-1800.

ANDRADE, TONIO. The Gunpowder Age: China, Military Innovation, and the Rise of the West in World History. Princeton University Press, 2016. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctvc77j74.

Börekçi̇, Günhan. “A CONTRIBUTION TO THE MILITARY REVOLUTION DEBATE: THE JANISSARIES USE OF VOLLEY FIRE DURING THE LONG OTTOMAN—HABSBURG WAR OF 1593—1606 AND THE PROBLEM OF ORIGINS.” Acta Orientalia Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae 59, no. 4 (2006): 407–38.

Brummett, Palmira. “Foreign Policy, Naval Strategy, and the Defence of the Ottoman Empire in the Early Sixteenth Century.” The International History Review 11, no. 4 (1989): 613–27.

Dean, Sidney E. “Ziska’s Wagenburg: Mobile Fortress of the Hussite Wars.” Medieval Warfare 6, no. 1 (2016): 43–46.

Górski, Szymon, and Ewelina Wilczynska. “Jan Žižka’s Wagons of War: How the Hussite Wars Changed the Medieval Battlefield.” Medieval Warfare 2, no. 3 (2012): 27–34.

Grant, Johnathan, Rethinking the Ottoman “Decline”: Military Technology Diffusion in the Ottoman Empire, Fifteenth to Eighteenth Centuries.

Hoffman, Philip T., Prices, the military revolution, and western Europe’s comparative advantage in violence.

Ligozzi, Jacopo (Italian, Verona 1547–1627 Florence). A Janissary “of War” with a Lion. ca. 1577–80. Watercolor, gouache, gold paint, gum arabic, and burnishing, 11 1/8 x 8 13/16in. (28.2 x 22.4cm). A Janissary “of War” with a Lion [1997.21]. The Metropolitan Museum of Art. https://jstor.org/stable/community.18691204.

Kadercan, Burak. “Strong Armies, Slow Adaptation: Civil-Military Relations and the Diffusion of Military Power.” International Security 38, no. 3 (2013): 117–52.

Khan, Iqtidar Alam. “Gunpowder and Empire: Indian Case.” Social Scientist 33, no. ¾ (2005): 54–65.

Pálffy, Géza. “SCORCHED-EARTH TACTICS IN OTTOMAN HUNGARY: ON A CONTROVERSY IN MILITARY THEORY AND PRACTICE ON THE HABSBURG—OTTOMAN FRONTIER.” Acta Orientalia Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae 61, no. ½ (2008): 181–200.

Tellis, Gerard, J. How Transformative Innovations Shaped the Rise of Nations: From Ancient Rome to Modern America.

*Note: I cannot do hanging indents.

0 notes

Text

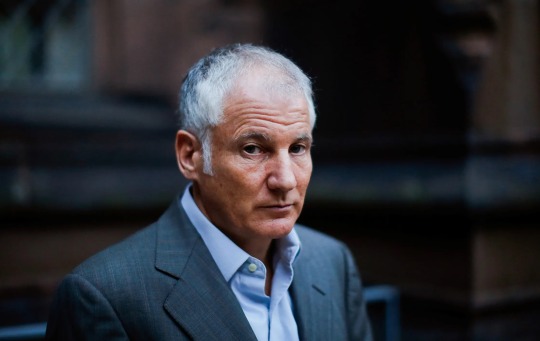

Should the West Threaten the Putin Regime Over Ukraine?

The Historian Stephen Kotkin on the State of the War and the Dangers of a Russian Tet Offensive.

— By David Remnick | October 3, 2023

“I’m Very Worried,” Stephen Kotkin Says. Photograph from Reuters

Since the Russian invasion of Ukraine, The New Yorker has been publishing on-the-ground reporting from our correspondents Luke Mogelson, Masha Gessen, and Joshua Yaffa, as well as commentary and reporting from Washington to Warsaw to the Baltic states. Throughout the conflict, I’ve been in touch with Stephen Kotkin, a professor of Russian history who taught at Princeton for more than thirty years, and is now at Stanford. Kotkin is the author of many books, including two volumes of a projected three-volume biography of Joseph Stalin.

Russia’s war against Ukraine began in 2014 with its militarized annexation of Crimea, and moved into its current phase when, in February, 2022, Vladimir Putin ordered a full-scale invasion. In the initial months of that second phase, Ukraine, under the leadership of Volodymyr Zelensky, and with support from nato, scored some astonishing victories, including the defense of Kyiv. But, although the people of Ukraine continue to stun the world with their resilience and imagination, the war shows no sign of ending anytime soon. And, as Kotkin puts it, Ukraine is running tragically low on young men of fighting age. Meanwhile, Putin does not hesitate to throw countless Russian bodies into the meat grinder of the war.

In an interview for The New Yorker Radio Hour, Kotkin talked with me about the situation on the battlefield and the evolving politics of Kyiv, Moscow, Washington, Beijing, and beyond. He raised the possibility of a Russian “Tet Offensive” that could alter the course of the American elections. He also questioned the Biden Administration’s seeming decision to “take regime change”—a threat to Putin’s rule—“off the table.” Our conversation has been edited for length and clarity; after we spoke, I added material, with Kotkin’s permission, from a series of e-mail exchanges.

This is our third conversation during this godforsaken war, and I have a very simple question: Where are we now?

Unfortunately, Ukraine is battling. They’re fighting and dying. The courage and the ingenuity are still there. But they’re running out of eighteen-to-thirty-year-olds. The average age of the Ukrainian soldiers training in Europe at the bases in Germany or the U.K. is thirty-five and older. They’re running out of munitions. They’re running out of anti-aircraft missiles. So I’m worried. I’m very worried, because of the huge casualties and the sheer size of Russia’s population compared with Ukraine’s.

It’s obvious that losses on both sides are enormous. What do we know about specific numbers?

Ukraine does not publicly release its casualty numbers, so we don’t know the exact number. But losses are really high––tens of thousands just during the counter-offensive alone. And here’s the problem: the guy in the Kremlin doesn’t care. Ukrainian leadership can’t just sacrifice their people in big numbers. So it’s not just that the numbers are bad; it’s that one side can use bodies as cannon fodder, and the other side can’t fight like that.

What’s your understanding of the success or nonsuccess of the Ukrainian counter-offensive against Russia?

It’s like the stock market these days. Everyone says they’re a long-term investor, they’re trying to produce long-term value, and then the analyst comes along and says, “Did you make your quarterly numbers? This was where you were supposed to be, and you failed.” Sadly, this is how we’re measuring what’s happening on the battlefield. The Biden Administration, our European partners, and the Ukrainians themselves talk about how they’re in it for the long haul. But then they go to a press conference and the first question they’re asked is, How come you didn’t meet your quarterly numbers? Why is the counter-offensive so slow?

The war is nine years old. People keep asking me how it’s going to end, and I say, “Why do you think it’s going to end?”

Speaking as a historian, what can a war of that length be compared to? What is the precedent for it?

All wars that start as wars of maneuver become wars of attrition, if they last longer than three to six months. And wars of attrition go on as long as both sides have the capability and the will to fight. If you don’t destroy the enemy’s capability or the enemy’s will, you can’t win a war of attrition. Ukraine has done some things that are just breathtaking. They’ve managed to neutralize the Russian Black Sea fleet without having a navy of their own. The ingenuity continues.

The problem is that there are two key variables in a war of attrition. One is the other side’s ability to fight. You’ve got to bomb their factories and take out their munitions production. The other variable is their will to fight. And, for Russia, the will to fight is about one guy. And we have taken regime change off the table. We have said many times, publicly and privately, that we’re not going to go after Putin’s regime because we don’t want him to escalate. But, by taking regime change off the table, we’re not pushing on the will to fight. And, if we’re not hitting Russia’s capacity to fight and not hitting their will to fight, then they can go on and on.

You seem to be saying that it was a mistake for the United States to make it clear to Russia that we are not pursuing a change of regime in Moscow?

I strongly back the policy of the threat of regime change. It is the most important lever to pull in order to exert pressure on Putin, who values his own personal regime above all else. As long as Putin feels that his regime is safe, he will continue to destroy Ukraine and throw his own people to their deaths.

But I acknowledge the argument that escalation is a danger that could arise from such a policy. I think this is a worthy public debate: Would the threat of regime change lead Putin to escalate the conflict? The avoidance of a wider war has been an achievement of the Biden Administration. It’s hard to get credit for something that does not happen, but the Administration deserves credit.

That said, I still support putting pressure on Putin’s regime. We should be seeking defectors among the nationalists, military, and security people who appeal to Putin’s base. Get those people—who are willing to state publicly that the war was a mistake, that it is hurting Russia, and that Ukraine is a separate country and people—out of Russia. Get them into European capitals, and on television or YouTube. The more the merrier.

The escalation debate has been solely about what might happen, or not happen, if we send more weapons. Most analysts have dismissed the possibility of escalation at all: we refuse to send tanks because of fears of escalation, then we send them, and there’s no escalation. Ditto for airplanes. But, of course, doing things gradually helps one to understand whether there will be escalation or not. In any case, sending tanks has not been decisive, and airplanes face the challenge of Russia’s anti-aircraft batteries (S-300s and S-400s). F-16s have almost never flown against anti-aircraft batteries in their history. Tanks are far less effective without air cover. Airplanes cannot fly against saturation anti-aircraft fire, and we are not attacking Russia’s anti-aircraft batteries, many of which are on Russian soil. It would take quite something to wipe them out.

Haven’t regime-change attempts brought about absolute disaster in our history, most recently in Iraq? And didn’t the fear of regime-change efforts, real or imagined, cause Putin to crack down in the wake of the Bolotnaya demonstrations in Moscow a decade ago?

You’re right—regime change has a checkered history. Readers are all too familiar with the Iraq War and the overthrow of Saddam Hussein. As you’ll recall from our private conversations back then, I did not support that war, largely because the vision and preparations for the aftermath were ludicrous. Probably the worst example of U.S.-induced regime change was the coup that overthrew Patrice Lumumba, in Congo, and eventually replaced him with Joseph Mobutu, leading to decades of misrule and agony.

But not all regime change is the same. Invading to impose democracy when one knows nothing about a country, or violently overthrowing a freely elected leader—after he had appealed to the U.N. for help and got no response, and then out of desperation appealed to Moscow, as in the case of Lumumba—is not something that I support. What I advocate is threatening regime change against Putin, who runs a mafia state and launched a criminal war against Ukraine, with the goal of stopping the war.

Putin will choose his regime over the war if he concludes that his regime’s survival is threatened. And others in Russia could step forward to make the choice for him. Some of this is going on already, in fact. William Burns, the head of the C.I.A., has admitted publicly that the U.S. and its allies are successfully recruiting Russian defectors. Richard Moore, the head of Britain’s M.I.6, gave a speech in Prague recently to encourage further defections in Russia. We should take the next step: making defections public, and using them to undermine the stability of the regime. We need men in uniform—Russian nationalists who appeal to Putin’s base, but who recognize that the war against Ukraine is hurting Russia—to speak the truth about the war, in Russian. We need help to convey to all Russian élites that Russia can still be a proud country and a major power if the war ceases.

France is another country with an absolutist monarchical tradition and a bloody revolutionary tradition. One day, I hope that Russia will look like France: a country that used to threaten its neighbors—think of Napoleon—but that now has the rule of law and democracy. But, for Russia, the distance to that outcome is not small, and even for France such a transformation did not happen quickly. Meanwhile, Ukrainians are dying en masse, and their country is being wrecked.

The threat of regime change in Russia—to force Putin into an armistice to preserve his regime, or to encourage others to do it—is among the ways to get Ukraine on a path toward peace. It might look like a bad idea, based on historical examples. It would not be easy, that’s for sure. But what is the superior, realistic alternative? More tanks that have limited battlefield utility because they lack air cover, while even F-16s would have limited effect because Russia has saturation S-300 and S-400 anti-aircraft batteries and a large inventory of missiles? Are we going to bomb Russian territory, where many of those batteries are located? Are we going to bomb factories located in Russia producing replacement batteries and missiles and other weapons? Are we going to blockade all of Eurasia, from Turkey through the U.A.E., Kazakhstan, and North Korea, not to mention China, to prevent easy sanctions-busting? Conjure munitions for Ukraine out of thin air? Watch a much smaller country fight a war of attrition indefinitely, costing lives and treasure?

On the Korean Peninsula, armistice negotiations lasted some two years. They finally resulted in an armistice only when Stalin died. I continue to hope that the Ukrainians can force an armistice on Putin by gains on the battlefield. But what if they cannot? What’s the plan? Are we prepared to wait until Putin dies? What happens to Ukraine in the meantime? Show me a better, more realistic plan than pressing the threat of regime change, and I’ll sign on to it.

We were talking on the phone the other day, and you raised what to me sounded like a shocking notion about what Russia could do next, and what it might resemble in American military history.

Yeah. I’m really worried about a Tet Offensive.

For those of us who might not remember the Tet Offensive, in Vietnam, in 1968, explain what it was, and what the parallel might be with Russia and Ukraine.

In January of 1968, the Vietcong and the North Vietnamese, who were fighting against the U.S. and its allies, the South Vietnamese Army, mounted an offensive. Until then, it looked like the war was going well for the U.S. And then, boom, lo and behold, they mount a very significant surprise offensive. We beat it back on the battlefield, and it’s ultimately a failure for the Communists. But, still, everyone is shocked that they could do this at all. And so Uncle Walter goes on TV—

Walter Cronkite, the anchor of CBS News at the time—

Yes. Uncle Walter says that this war is not winnable. And that was a pretty big moment for Lyndon Johnson, the incumbent Democratic President, who subsequently decides that he’s not going to run for reëlection. So, although the Tet Offensive was a battlefield failure for the North Vietnamese-Vietcong, it was a political triumph for them.

The Ukrainian counter-offensive could work. It’s way too early to evaluate it. However, they could be surprised by a Russian counter-offensive, which doesn’t have to succeed to any great degree on the battlefield. It could be just like Tet in that way. But it could send political shock waves through Washington, D.C., and through the European capitals. People could conclude that this war may not be winnable.

In March, 1968, following Tet, Johnson said he would not run for reëlection, opening the way for Eugene McCarthy, Robert Kennedy, and Hubert Humphrey to compete for the Democratic nomination. (Eventually, the Republican, Richard Nixon, won.) Do you really think that a Russian offensive like the Tet Offensive could affect the 2024 U.S. Presidential race to the same degree?

It could. I don’t know the probability, but my view is that, if it’s possible, we’ve got to be ready. We have to prepare the public. And we have to prepare the battlefield.

I want to drill down on one point. You said that a Russian offensive, a Tet offensive, even if it doesn’t succeed, could have profound effects on the American political scene, even to the point that it affects Joe Biden’s fate in the race.

Look at Biden’s numbers. They cratered with the Afghanistan pullout. If Putin outsmarts us on the battlefield and mounts a counter-offensive . . . Well, I’d want to get out in front of this. I would be talking about the coming Russian counter-offensive, and trying to make it more difficult for such a thing to have a political effect. That might even make it more difficult to carry out at all.

Do you think a Ukrainian victory is impossible in the foreseeable future?

Nothing’s impossible, right? Here’s the challenge, though. You take Tokmak. They’re still far from it, but that’s the next objective on their line of deepest penetration. It’s on the road to Melitopol. That’s on the road to the Sea of Azov, on the land bridge that connects Crimea and the parts of eastern Donbas that Putin has taken since February, 2022.

What’s your next step? How do you then win the peace? How do you start rebuilding Ukraine? How do you get to a Ukraine that is able to join the European Union over a period of time, and transform its internal institutions as a result of the E.U.-accession process? Where do you get the security guarantee from? Where do you get the expensive armaments that you can use as a deterrence?

The U.S. has been sending two hundred million dollars a day to Ukraine since this war started. I’m in favor of that support, but that’s not something that countries do forever. How do you get to the peace where Russia doesn’t do this again? Every war ends with a negotiation. Even unconditional surrender produces a form of negotiation. We need a process to win the peace, not just an assessment of the counter-offensive day to day. And, unfortunately, we haven’t had that, because there’s a divergence between the vision of the war in D.C. and the vision of the war in Kyiv.

Recently, President Zelensky was in Washington to see Joe Biden, and he spoke at the U.N. Zelensky gave the kind of speeches we’ve grown accustomed to, in which he’s both thanking the West for its aid and imploring it for more; he’s demanding constancy and the psychology that this is not just a war for Ukraine, but for the democratic West. Now, we’ve heard this before. I’m wondering if you perceived—on the part of the listeners—any change in perspective.

Yes. But the challenge is in the idea that the international order is at stake. In the U.S.’s rhetoric, nothing could be bigger than this, right? This is about deterring authoritarian powers, or they’ll do it again. This is about securing the rules-based order. This is about everything. There’s nothing bigger than this. But, at the same time, we can’t put American troops on the ground in Ukraine.

Those two statements cannot both be true. You can’t say that everything is at stake––world order, peace, and prosperity––while not considering the threat to be important enough to warrant putting American troops on the ground in Ukraine. And yet this is our strategy. And that’s why Americans don’t understand our strategy. That’s why our political figures can’t explain our strategy. And that’s why it’s not working as well as some people predicted it would work.

Of course, in Kyiv, they have a different view of this. For them, this war is about their existence, their sovereignty, their independence as a nation. The Russians are killing their people, destroying their infrastructure, raping their women and girls, destroying or pilfering their cultural artifacts to remove evidence that Ukraine is a separate culture and a separate nation. So, for Ukrainians, the idea of negotiation, the idea of relinquishing territory for an armistice, the idea of allowing Putin to get away with this without sitting at a military or international criminal tribunal, without paying reparations—that is anathema. It’s not just that the Russians are committing atrocities; this whole war is an atrocity.

So the Ukrainians have a maximalist view of what peace means. It’s about justice. It’s about reparations. It’s about war-crimes tribunals. It’s about stuff that they can’t impose because they can’t take Moscow. Their perspective is understandable. It’s completely justified from a moral point of view. But you’ve got to live in the world that you live in, and so this divergence between our view of the war and their view of the war is covered over by our rhetoric, which says it’s also existential. If the fate of the world is at stake, you have to be in favor of American boots on the ground.

I’m not clear what you’re saying. Are you arguing for America to send troops to Ukraine?

No, I am not. I’m arguing for bringing the rhetoric in line with the commitments. Otherwise, the American people are confused. Otherwise, we don’t understand the strategy. You can’t support this over the long haul if people think that you’re not telling the truth, or you’re not being level with them. Our commitments don’t match our rhetoric.

What do you think we need, in terms of Western policy, in terms of American policy?

We need an armistice. We need a D.M.Z. We need the fighting to stop. We need the eighteen-to-thirty-year-old Ukrainians who are left not to die. We need the Ukrainian kids who are going to school in Poland and Germany and elsewhere to come home, and go to school in the Ukrainian language, and become the future of the country. We need to invest and to rebuild the economy. We need Ukraine to start the E.U.-accession process. We need them to have some type of security guarantee, which is about not just deterring Russia but enabling a successful society in Ukraine.

That leaves a lot of Ukrainian territory, particularly the Donbas and Crimea, in the hands of Russia, which is an unacceptable outcome in today’s Ukraine. Both Crimea and the Donbas were part of sovereign Ukraine when it became an independent country, in 1991. Do you support relinquishing those territories?

If you can take them back, by all means, take them back. But, if you take back Crimea, what do you do with the Russians? There were 2.3 million people in Crimea, approximately, before the war, predominantly ethnic Russian. Five hundred thousand people from Russia have moved into Crimea since the war started. Russians who were abroad have bought apartments in Crimea since 2014. So you’ve got a big population of Russians there. What are you going to do—ethnically cleanse them? Force them out of Crimea in the hundreds of thousands or more? How’s that going to look when you start the E.U.-accession process?

Under international law, Russia has annexed territory that belongs to Ukraine, and it’s a violation. I proposed, in 2015, in Foreign Affairs, that if Ukraine can’t get the territory back, or isn’t willing to do what’s necessary to get it back, or getting it back might not be beneficial because of the high percentage of ethnic Russians there, how about if you force Putin to buy it? To pay for it? You do it on the installment plan. A five-, or ten-, or twenty-five-year plan. At the end of it, after Russia pays the money—and if, during that period, they behave in a way that doesn’t threaten Ukrainian sovereignty—we would internationally recognize it as Russian territory. Is that a good outcome?

It’s a lot less satisfactory than taking it back, and reinstating it as Ukrainian territory, the way it was from 1991 to 2014. It’s unsatisfactory. I get that. But, if you can’t get it back, if you can’t march on Moscow, if you can’t impose the peace that’s morally just, if your partners won’t put boots on the ground to impose that peace on Russia with you as your partner, and you can’t pay the costs that might be necessary to take it back on the battlefield—if those things are true, then what do you do? It’s not something that I’m happy about. But I’m aiming for a Ukraine that’s rebuilding, not being bombed and destroyed, and I’ll take as much of that Ukraine as I can get in the time being. And, if I don’t get it all, I’m not going to acknowledge Russian occupation legally. Ukrainians want to be part of Europe, and they’re willing to die for that. That’s winning the peace, in my mind. And territory is part of that, but territory is much less decisive.

President Zelensky recently fired and replaced the top six military leaders in Ukraine. I’m trying to imagine a situation in which the United States is at war, and the President suddenly gets rid of the entire top echelon of the military. It would be a gigantic story. What happened in Ukraine, and what does it indicate about the country’s military leadership and the state of the war?

Until an E.U.-accession process transforms Ukrainian domestic institutions, we have the Ukraine that we have. Courageous, ingenious—their tremendous resistance just blows me away. But, on the institutional side, it’s not a happy story. There are shortcomings in Ukrainian institutions. We have to use the word “corruption” to talk about Ukraine. If you’re eighteen or nineteen, and your parents have money—if they have the U.S. equivalent of eight or ten thousand dollars to spend—you can buy off the military-recruitment chief of your locality and get out of going to war. And that’s been happening. It’s a big business. So Zelensky fired all the heads of his military-recruitment offices. He’s doing what he can. He’s trying to say that we take corruption seriously, we’re going to be accountable for the money and the weapons that you send, we’re going to fight this corruption battle, we’re not going to turn a blind eye to it, even though we’re under attack. He’s showing that he’s serious. He’s trying to send a message to the others who are going to replace those military leaders, and saying, Don’t do what they did. Does it stop corruption in the longer term? I don’t know. I don’t know whether he can prevent it over the course of a longer war.

We’ve seen increasing evidence of a global realignment since the beginning of the second phase of the war against Ukraine, the full-scale invasion. Putin has sought to align with North Korea, with China, and to some extent with India, against the West. How successful has he been?

That’s a really important question. So far, Ukrainian courage and ingenuity have produced four big victories. One is that Ukraine has kept its sovereignty. It has defended its capital and kept itself independent. There is no puppet regime in Kyiv. That’s a huge victory.

The second victory—just as big, if not bigger, from a strategic point of view—is that the West has been resuscitated. People rediscovered that the West exists as a family of shared values and shared institutions. North America, Europe, and the first island chain in Asia, from South Korea all the way down to Australia: The West is not a geographical concept, but it’s an institutional concept, and it’s been revived, with unity and resolve. It’s got the wealth, it’s got the technology, it’s got the institutions. Rediscovering that was a huge victory.

The third victory was Russian humiliation. Not strategic defeat—that’s an exaggeration—but the humiliation of Russia. We’ve seen that Russia is not ten feet tall. Putin is not a genius. He’s not even a tactician, let alone a strategist. He’s a murderer, and he’s troubled, but he’s no genius.

The fourth big victory is China’s losing its lustre. Beijing had concluded that the U.S. was going to try to contain China, and it was going to be hostile. But Europe, which hates conflict and loves trade, could still be a friend. And so there was a wedge driven between the U.S. and Europe, these close allies, on China policy. But Xi Jinping, by siding with Putin in this war, has destroyed his wedge. Europe is now more aligned with the U.S. on China policy, and understands that having its economy be dependent on an authoritarian regime is not a good idea.

So those are four big victories. And, now that we’ve made them, we should want to take those off the table. You don’t want to be in a situation where Kyiv could still be at risk, and where Western unity and resolve could be undermined by a Tet Offensive. And yet these gains are still in play, still at risk, because we’re trying to get territory back in Ukraine, which may or may not be germane, in my view, to winning the peace. That’s the big story.

Then we have what you asked about—the success of Putin’s attempt to get closer to China. Let’s be careful here. Russia and China’s alignment has discredited both countries. Has it been a net plus for them or a net minus for them to get closer?

There are countries that are not part of the West, but that want the opportunity that the West offers. They want access to technology. They want access to our universities, where they can study. They want all sorts of things, including security, that we can provide. Why did it happen that China became synonymous with opportunity, and the U.S. became synonymous with war? We do Iraq, we do Afghanistan, and China does opportunity. China builds infrastructure, they build bridges, they build your telephone network. We dropped the ball. We have to get back to opportunity because the thirst for opportunity is so vast. It’s the international system that we created that brought Germany and Japan, our enemies, back into being successful, prosperous democratic societies. The conversation has to change. Everyone else is invited to join peace and prosperity. And those who are opposed to that, we need some deterrence. Your regime could fall if you are behaving in ways that are destabilizing to the international order. ♦

— Stephen Mark Kotkin (Born February 17, 1959) is an American Historian, Academic, and Author. He is the Kleinheinz Senior Fellow at the Hoover Institution and a senior fellow at the Freeman Spogli Institute for International Studies at Stanford University. For 33 years, Kotkin taught at Princeton University, where he attained the title of John P. Birkelund '52 Professor in History and International Affairs, and he took emeritus status from Princeton University in 2022. He was the director of the Princeton Institute for International and Regional Studies and the co-director of the certificate program in History and the Practice of Diplomacy. He has won a number of awards and fellowships, including the Guggenheim Fellowship, the American Council of Learned Societies and the National Endowment for the Humanities Fellowship. Kotkin's most prominent book project is his three-volume biography of Joseph Stalin, of which the first two volumes have been published as Stalin: Paradoxes of Power, 1878–1928 (2014) and Stalin: Waiting for Hitler, 1929–1941 (2017), while the third volume remains to be published.

#The New Yorker#Stephen Kotkin#David Remnick#Ukraine 🇺🇦 | Russia 🇷🇺 | Vladimir Putin | Volodymyr Zelensky#US 🇺🇸 | Joe Biden | Wars Diplomacy

0 notes

Text

well since 2022 I have been doing this again so the 1st everything’s always been old school or eabos again digitized stream tonight barely got any views. thanks for nothing. well for those who do care well again please watch i am live again now on youtube for 2nd stream so tune in now.

my simply everythings always been old school no∞turing visual glitches this time and alan turing etc. evolved the same old same old digital/computer algorithm since world war 2 stream live now and in 2022 I fought fire with fire digitized stream

so again my previous digitized stream had visual digitized glitches but no digitized audio glitches thankfully so again I know twitch is making it difficult for me to fight fire with fire. The past couple twitch streams have been unstable and the other one was not as unstable most of it was stable but the latest one was completely unstable. So now digitized live on youtube.

#military #army #marines #navy #usa #worldwar2 #wwII #life #turing #chatgpt #reddit #twitch #tumblr #twitter #youtube #algorithm #google #tech #technology #callofduty #battlefield #video #gaming #assassinscreed #sports #comedy #fun #Princeton #rutgers #prestigious #kids #puberty #adult #teens #preteen #puberty #ivyleague #marryville #ymca #frank #ign #cancer #eabos

0 notes

Text

https://www.newyorker.com/news/the-new-yorker-interview/how-the-war-in-ukraine-ends

The New Yorker Interview

How the War in Ukraine Ends

An eminent historian envisions a settlement among Russia, Ukraine, and the West.

By David Remnick

February 17, 2023

Illustration by Tomasz Woźniakowski

Last year, not long after Vladimir Putin ordered the invasion of Ukraine, I turned to the historian Stephen Kotkin for illumination and analysis. I’ve been doing that, for good reason, since the final years of the Soviet empire. Kotkin has published two volumes of a projected three-part biography of Stalin, and his works on the dissolution of the Soviet Union and its aftermath are without peer in their precision and depth. After spending more than thirty years at Princeton, he is now at Stanford.

In our conversation last year, we delved into the nature of the Putin regime, his decision to invade, and what the war could look like as time unfurled. Now we know: the Russian invasion has been a catastrophe in every sense. There have been hundreds of thousands of casualties––it is folly to attempt a more accurate reckoning––and much of Ukraine’s infrastructure is in ruins. Once the Russian military failed to achieve its early hope of taking the capital, Kyiv, and supplanting the Ukrainian leadership, it has prosecuted a vicious war of attrition, in which more and more human beings on both sides are sacrificed to Putin’s pitiless ambitions.

Kotkin is a top-flight scholar, but his ties to the subject are not limited to the archives and the library. He is well connected in Washington, Moscow, Kyiv, and beyond; his analysis of the war draws on his conversations with sources as well as on his own base of knowledge. We spoke again last week, and our discussion, which appears in different form on The New Yorker Radio Hour, has been edited for length and clarity.

Last year, you told me, at a very early stage of the war, that Ukraine was winning on Twitter but that Russia was winning on the battlefield. A lot has happened since then, but is that still the case?

Unfortunately. Let’s think of a house. Let’s say that you own a house and it has ten rooms. And let’s say that I barge in and take two of those rooms away, and I wreck those rooms. And, from those two rooms, I’m wrecking your other eight rooms and you’re trying to beat me back. You’re trying to evict me from the two rooms. You push out a little corner, you push out another corner, maybe. But I’m still there and I’m still wrecking. And the thing is, you need your house. That’s where you live. It’s your house and you don’t have another. Me, I’ve got another house, and my other house has a thousand rooms. And, so, if I wreck your house, are you winning or am I winning?

Unfortunately, that’s the situation we’re in. Ukraine has beaten back the Russian attempt to conquer their country. They have defended their capital. They’ve pushed the Russians out of some of the land that the Russians conquered since February 24, 2022. They’ve regained about half of it. And yet they need their house, and the Russians are wrecking it. Putin’s strategy could be described as “I can’t have it? Nobody can have it!” Sadly, that’s where the tragedy is right now.

How do you even begin to analyze Putin as a strategic figure in this horrendous drama?

He is not a strategic figure. People kept saying he was a tactical genius, that he was playing a weak hand well. I kept telling people, “Seriously?” He intervened in Syria, and he made President Obama look like a fool when President Obama said that there would be a red line about chemical weapons. But what does that mean? It means that Putin became the part owner of a civil war. He became the owner of atrocities and a wrecked country, Syria. He didn’t increase the talent in his own country, his human capital. He didn’t build new infrastructure. He didn’t increase his wealth production. And so if you look at the ingredients of what makes strategy, how you build a country’s prosperity, how you build its human capital, its infrastructure, its governance—all the things that make a country successful—there was no evidence that any of the things that were attributed to his tactical genius, or tactical agility, were contributing in a positive way to Russia’s long-term power.

In Ukraine, what is it that he’s gained? If you look over the landscape, he’s hurt Russia’s reputation—it’s far worse than it ever was. He consolidated the Ukrainian nation, whose existence he denied. He is expanding nato, when his stated aim was to push nato back from the expansion undertaken since 1997. He’s even got Sweden applying for nato membership. And, so, all across the board, it’s a disaster.

The problem is that he’s in power. And soft Russian nationalists, who were semi-critical of Putin, now have no place to go because you’re either all in, or you flee to Armenia, Georgia, Kazakhstan, and Turkey. He’s wrecking his own country in a way, although in a very different way from the murdering that he’s carrying out in Ukraine.

What has been revealed about Russia’s military and its intelligence capabilities in the past year?

The war’s a tragedy. There’s no way to spin it as other than tragic, given what’s happened: the number of deaths in Ukraine; the amount of destruction; the consequences for other countries, including food insecurity. But there have been some pleasant surprises. One was the Ukrainians’ ability and will to fight. It’s been very inspiring from the get-go. We knew they would fight to a certain extent, because they twice overthrew a domestic dictator: in 2004 and in 2014. They went out into the streets, risked life and limb, and were willing to confront those domestic tyrants. Now you have a foreign tyrant. We knew that they would resist, but it’s been a pleasant surprise, the depth of their courage and resistance.

The other pleasant surprise has been Russia’s failures. We knew that there were issues with Russia: many of us thought that the Russian Army was really only about thirty thousand or fifty thousand strong, maximum, in terms of trained fighters who had up-to-date kit—as opposed to hundreds of thousands of dog-food-eating conscripts, untrained or poorly trained, badly equipped soldiers under corrupt officers. But, still, the depth of the Russian failure in Ukraine, from a military point of view of their objectives, was a pleasant surprise for many of us, myself included.

And there’s Europe’s adaptability and fortitude, right? Everybody said, “If Europe doesn’t have its cappuccinos in the morning and its espressos after lunch, there’s no way they could put up with this.” Look what’s happened: they switched from their dependence on Russian energy much faster than anybody thought. They’ve rallied in support of Ukraine pretty much across the board.

Then there’s been what I would call an unfavorable surprise. Despite the sanctions, the Russian economy didn’t shrink, let alone shrink massively. It turns out that the Russian people proved extremely adaptable to the sanctions regime and figured out how to survive—and, in some cases, how to prosper. Russian imports are back, and Russian exports are back. Russian employment is looking O.K. Yes, the figures are a secret, but there are indirect ways that we can figure it out. How much is Turkey exporting? That helps us figure out how much Russia is importing, even though Russia’s keeping it a secret. So it turns out that the sanctions are not having the effect of inflicting severe pain in the short term. We’ll see what the long-term impact is. But so far the pressure to make Russia reconsider its policy of criminal aggression against Ukraine has not been there—even less than I thought it would be, and I was a skeptic on sanctions.

Steve, last year we talked about Sun Tzu, the great Chinese theorist of war, who said that you have to build your opponent “a golden bridge” so that he can find a way to retreat. A year later, do you have any thoughts on what that might look like, and is anybody even thinking about it at this point?

That would be a great thing, if we could do that. But there’s nothing like that in sight. You win the war on the battlefield. There are some shortcuts that could potentially enable you to get to a victory more quickly—for example, if the Russian Army disintegrated in the field. I said, a year ago, that that seemed unlikely, and there hasn’t been any evidence that the Russian Army is disintegrated in the field. In fact, the call-up of the several hundred thousand new recruits—they’ve been deployed, they’re on the front lines, and they’re fighting. The other shortcut we talked about was an overthrow of the Putin regime in Moscow and his replacement by a capitulatory, not an escalatory, Russian leader. But there was no evidence that the regime was in trouble. Authoritarian regimes can fail at everything—they can even launch self-defeating wars—so long as they succeed at one thing, which is the suppression of political alternatives. He’s very good at that. And then the third shortcut was the idea of the Chinese exerting pressure to force Russia to climb down. We didn’t think that China had this leverage, and we certainly didn’t think they would use their imaginary leverage.

So, without the shortcuts, we’re at the battlefield. And the problem with the battlefield is that victory is misdefined here. You have to win on the battlefield, but how do you then win the peace as well? What would winning the peace look like? We know you can win on the battlefield and lose the peace, right? Sadly, we’ve experienced that in our own country, with some of the wars that we’ve been involved in.

Vietnam, for example.

Yes. And then some of the more recent ones in the Middle East.

So here we are with Ukraine, and their definition of victory—as expressed by President Zelensky, who has certainly more than risen to the occasion—is to regain every inch of territory, reparations, and war-crimes tribunals. So how would Ukraine enact that definition of victory? They would have to take Moscow. How else can you get reparations and war-crime tribunals? They’re not that close to regaining every inch of their own territory, let alone the other aims.

If you look at the American definition of what the victory might look like, we’ve been very hesitant. The Biden Administration has been very careful to say, “Ukraine is fighting, Ukrainians are dying—they get to decide.” The Biden Administration has effectively defined victory from the American point of view as: Ukraine can’t lose this war. Russia can’t take all of Ukraine and occupy Ukraine, and disappear Ukraine as a state, as a nation.

But what would Biden—and U.S intelligence and the U.S. military—really like to see, in terms of a shift in attitude, if that’s the case?

We are slowly but surely increasing our support for Ukraine. First it was “Oh, no, we’re not sending that.” And then we send it. “Oh, no, we’re not sending himars,” the medium-range rocket systems. We sent them. “Oh, no, we’re not sending tanks.” Well, yes, we’re sending tanks. So there’s been a kind of grudging, gradual escalation because of the fear of what Putin could do on his side in an escalatory fashion. And so we’ve given enough so that Ukraine doesn’t lose, so that they can maybe push a little more on the battlefield, regain a little bit more territory, and be in a better place to negotiate.

Here’s the better definition of victory. Ukrainians rose up against their domestic tyrants. Why? Because they wanted to join Europe. It’s the same goal that they have now. And that has to be the definition of victory: Ukraine gets into the European Union. If Ukraine regains all of its territory and doesn’t get into the E.U., is that a victory? As opposed to: If Ukraine regains as much of its territory as it physically can on the battlefield, not all of it, potentially, but does get E.U. accession—would that be a definition of victory? Of course, it would be.

Says you, but would the Ukrainian leadership and the Ukrainian people accept a situation in which they’re in the E.U., but Donbas and Crimea remain in Russian hands?

Well, you accept it or you don’t accept it—meaning you continue to fight. And, if you continue to fight, your country, your people, continue to die, your infrastructure continues to get ruined. Your schools, your hospitals, your cultural artifacts get bombed or stolen. Your children get taken away as orphans. That’s where we are right now. I understand they want all of that territory back. But let’s imagine that they can’t take all the territory back on the battlefield. What then? We’re in a war of attrition right now, and in a war of attrition there’s only one way to win. You ramp up your production of weaponry, and you destroy the enemy’s production of weaponry—not the enemy’s weapons on the battlefield, but the enemy’s capability to resupply and produce more weapons. You have to out-produce in a war of attrition, and you have to crush the enemy’s production.

What’s an example of that historically?

Every war that’s ever been fought. There are two ways that major wars evolve. They all start as wars of maneuver because somebody attacks. There’s a lot of movement at first, and then they meet resistance and the offensive stalls out because it’s hard to maintain an offensive, and the other side’s resistance gets ramped up. Then what happens is you radically expand your industrial base for weapons. That’s what the U.S. did in World War Two, and that’s how we won the war.

And so think about this: We haven’t ramped up industrial production at all. At peak, the Ukrainians were firing—expending—upward of ninety thousand artillery shells a month. U.S. monthly production of artillery shells is fifteen thousand. With all our allies thrown in, everybody in the mix who supports Ukraine, you get another fifteen thousand, at the highest estimates. So you can do thirty thousand in the production of artillery shells while expending ninety thousand a month. We haven’t ramped up. We’re just drawing down the stocks. And you know what? We’re running out.

Is Russia running out?

We’ll get to that in a second. But we’re on the hook for Taiwan, and we’re four years behind now in supplying Taiwan for contractual orders of American and allied military equipment. General [Mark] Milley, [chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff], God bless him, he’s there in the Pentagon, in that big E-ring where all the important people sit, and he turns his head because all his stuff is going out the door. Everything in our stocks is going right out the door, right past his desk. And it’s not going to Taiwan, which is a place that we want to send it. And so we would have to radically ramp up production, us and our allies, to fight a war of attrition.

And, at the same time, the sanctions were supposed to destroy Russia’s ability to produce weapons, and that’s not happening. Russia can produce about sixty missiles a month under sanctions. So that’s two horrible barrages against Ukrainian civilian homes and infrastructure, their energy infrastructure, their water supply—sixty missiles a month. That doesn’t include what they’re buying back from Africa that they previously sold. What they’re trying to get in deals with North Korea or Iran. The Soviet arsenal, the biggest arsenal ever assembled—a lot of it is rotting, but not all of it is rotting. Some of the production is still ongoing, not as much as Russia would like, but enough to carry out the strategy of “If I can’t have it, nobody can have it.”

If you’re in a war of attrition, you’ve got to be bombing the other side’s production facilities. You have to be denying the other side the ability to resupply on the battlefield. And you have to be ramping up your production like we did in the previous wars where we were directly engaged, but we haven’t done here. So tell me: How do you fight a war of attrition with your left hand tied behind your back and your right hand tied behind your back? The Ukrainians are amazing. It’s just so inspiring to see what they’re doing. But if we get every inch of territory back—and we’re not close to that—we still need an E.U. accession process. Ukraine will need a demilitarized zone, no matter how much territory it gets back, including if it somehow gets Crimea back. It’s got the problem that, next year, the year after, the year after next, this could happen again.

Recently, in the Washington Post, there was an interview with [Kyrylo Budanov], the very young head of Ukrainian intelligence. What did I get out of the interview? Two things. One: a sense of optimism that includes not only doing well on the battlefield but getting back Crimea within the next year. And, number two, he said with great confidence that Vladimir Putin is extremely sick. I have the suspicion that the rumors of Putin’s poor health are—the origins of that are—from Ukrainian intelligence. Can you address those two points?

Of course, we fully understand Ukrainian intelligence has to be optimistic. He’s not going to go in the Washington Post and say, “Our chances of taking Crimea are next to zero. We’re going to have another hundred thousand casualties over the course of the next year or so. Even if the tanks arrive by May or late April.” He can’t say stuff like that.

Is there any evidence that Putin’s health is actually poor?

The director of the C.I.A., William Burns, publicly announced that there’s no evidence that Putin is sick. Once again, we want it to be true, because we want a shortcut to a Ukrainian victory. The problem is, we have to live in the circumstances we’ve got. If you look at the North Korea–South Korea outcome, it’s a terrible outcome. At the same time, it was an outcome that enabled South Korea to flourish under American security guarantees and protection. And, if there were a Ukraine, however much of it—eighty per cent, ninety per cent—which could flourish as a member of the European Union and which could have some type of security guarantee—whether that were full nato accession, whether that were bilateral with the U.S., whether it were multilateral to include the U.S. and Poland and Baltic countries and Scandinavian countries, potentially—that would be a victory in the war.

Now, if Ukraine can achieve its stated victory of every inch of territory, reparations, and war-crimes tribunals, it still has to get into the West in order to consolidate those gains. It still needs a security guarantee. So we’re arguing over some issues which are deeply important to the Ukrainians because of the atrocities committed against them. At the same time, it’s maybe not the definition of victory that would get Ukraine to a better place, in a more reasonable amount of time with fewer casualties, given the situation.

Western patience and Western supplies are not a given for all kinds of factors. Various European factors. You have a Republican Congress now that is not as likely to accede to Ukrainian requests as the Democratic one was. Am I right?

I’m not worried about resolve here. I came up with this equation early in the process, which is: Ukrainian valor plus Russian atrocities equals Western unity and resolve. And it’s held. Because the Ukrainian valor continues—and it continues to inspire the whole world, not just their own war effort internally. The Russian atrocities continue because that’s what this war is. It’s an atrocity. It’s more like murder than it is like war. So I’m good on the Western alliance holding together. My problem is material. I don’t have a military-industrial complex on the scale to continue this indefinitely. I’m running my own stocks down. I’m not supplying my other allies, including Taiwan. And I have an opportunity-cost issue here.

But wait a minute. Russia has the same problem, with a different look. It has proven that its military—on a level of organization and supply and strategy—is nothing like what it had been advertised. We have the so-called Wagner Group, led by Yevgeny Prigozhin, going from prison to prison, taking thousands of people who were serving time, and throwing them onto the Ukrainian battlefield within days.

He’s a former convict himself!

A former chef and former convict. But what does that suggest about Russia’s military? It, too, is being depleted rather quickly, no? Or are you just saying, because of the sheer population and scale, Russia’s advantages are obvious?

Russia is much bigger; it has many more people. Also, the Russian leadership doesn’t really care about its people. If the Russian leadership throws twenty thousand untrained recruits into the meat grinder and three-quarters of them die, what do they do? Do they go to church on Sunday and ask forgiveness from God? They just do it again. People talk about Stalin and the big sacrifices that the Soviet people made in World War Two, losing twenty-seven million people. They were enslaved collective farmers. He had millions and millions more of them. He threw them into the meat grinder and they died. Then he threw more into the meat grinder!

In that respect, isn’t the Stalin era different than the Putin era? Ever since the controversial mass conscription, you saw political repercussions in Russia that you would not have seen in Stalin’s time.

Sort of. You saw tens of thousands of people resist and flee. You also saw a couple of hundred thousand get deployed. You know, Leonid Bershidsky, of Bloomberg, got this right. He said we focus on those who resist the call-up, the conscription. We don’t focus on those who are actually deployed. The Russian leadership has no trouble expending its weaponry and sending its people to death. The value of life in the Putin regime is just not there. When you talk about Roosevelt not wanting to take Berlin before Stalin did, because he didn’t want to sacrifice human lives—and then people complain that he should have done it anyway? Democracies don’t fight wars which are intentionally a meat grinder, to just throw their people away. And a war of attrition is what we’re asking of the Ukrainians. They’re doing the fighting. We’re not doing any of the fighting.

Much of the challenge here comes from the fact that President Biden and the European allies have decided that there will be no direct engagement between nato forces and Russian forces. There’s been a ceiling on how far we would go in assisting the Ukrainians. We don’t want an escalation of direct confrontation with the Russians or Russians using some of the capabilities that Putin has, that we all know about—and we’re right to be concerned about.

People say, “It would be irrational if Putin were to use nuclear weapons. It would be self-defeating. He would just get destroyed himself in retaliation.” And the answer is: from our point of view, certainly that would be really stupid. Just like this war. Starting this war looks really stupid, from our point of view.

But he thought that he could take Kyiv, and arrest or kill Zelensky. That was the plan, that it would be a matter of days or weeks, tops. It hasn’t gone that way. On the use of nuclear weapons––it’s been made clear to him by representatives of Western governments and the United States precisely what kind of retaliation he could expect.

Yes, I think that’s a great policy. I’m very happy that that happened. But here’s the problem. He has the capabilities. He’s got a lot of capabilities short of nuclear weapons. He could poison the water supply in Kyiv with chemical and biological weapons. He could poison the water supply in London, and then he could deny that it’s his special operatives that are doing that. He could cut the undersea cables, so that we could not do this radio broadcast. He can blow up the infrastructure that carries gas or other energy supplies to Europe. He’s got submersibles, he’s got a submarine fleet, he’s got special ops who can go right down to the ocean floor where those pipelines are located.

What does restrain him?

We don’t know. You tell me. When someone has these capabilities, you have to pay attention. You can’t say, “Oh, you know, that would be crazy if he did that. That would be totally self-defeating. What idiot would do that?” And the answer is: O.K, but what if he does it?

We have to be concerned about escalation. I have been in favor of greater supply, more quickly, of more weapons to the Ukrainians from the beginning. But not because I’m blasé about the capabilities that Russia has.

Why are you in favor of that?

Because I think the Ukrainians deserve the chance to try to win on the battlefield before we get to that part that you described as: each side has to sit down and make unpleasant concessions, and you have to sit down across from representatives of your murderer, and you’ve got to do a deal where your murderer takes some of the stuff he has stolen—and killed your people in the process. That’s a terrible outcome. But that’s an outcome which may not be the worst outcome. The point being that, if you get E.U. accession, it balances the concessions you have to make.

How big has the Ukrainian exile been—or how many Ukrainians have left?

We don’t know exactly, but we’re in the multimillions. And that’s your future. That’s the future of your country. The hope is that it’s temporary and they get them back, and they can go back to a peacetime country. And they can be prosperous and they can have careers and they can show what they can do—not just on the battlefield, like their elders are doing now, with the incredible ingenuity that we see from the Ukrainians—but that they can do that and establish civilian companies. Then you have a reconstruction issue. Even if you win, you’re wrecked. You’ve got to have reconstruction. You know what kind of numbers we’re talking about? Three hundred and fifty billion dollars is one of the numbers being tossed around.

If things ended today?

Yeah. And who knows what the actual number is? What was Ukrainian G.D.P. before the war? About a hundred and eighty billion dollars. So you’re talking double G.D.P., in reconstruction funds, has to somehow enter that country and not disappear, not vanish. What happened to the covid funds in our country? We’re still trying to find some of them. Billions disappeared. And so you’re talking double their prewar G.D.P. So for that you need functioning institutions, not wartime resistance institutions. You need a civil service. You need an independent judiciary. You need a lot of stuff—a banking system—to manage that type of reconstruction and doing that honestly, fairly, and smartly. Right now, there’s no prospect of those reconstruction funds being able to be used well, because they don’t have those functioning institutions. They’re at war. And they didn’t have such functioning institutions before the war started, as you know.

It was interesting to see Zelensky get rid of a few top officials for corruption charges very recently, in the middle of the war.

What choice does he have? Part of it is real, and part of it is performance. He’s an incredible leader in a wartime situation, and we owe him a lot. We owe him the rejuvenation of the West—the rediscovery of the West—in institutional, not geographic, terms, including our Asian partners, Japan, Australia.

We’re in a situation where the sooner we get to a reconstruction of Ukraine in some form, where we don’t lose a generation of kids who grow up to be eighteen in Poland—we want to get those kids back. We want to build a South Korea-style Ukraine, part of the E.U., behind the D.M.Z., where there’s an armistice, not a settlement; where there is no legal recognition of any Russian annexations unless there’s some type of larger bargain, peace settlement; where the Russians make significant concessions as well and there is the move toward an actual security guarantee rather than discussion and promises of a security guarantee. We need to get to the other side of this in a way that gives Ukraine a chance to be the country that they want to be, deserve to be, and could be with our support.

It’s one thing for them to now get the tanks and see if they can pull off an offensive, likely in the summer—or, at a minimum, stave off a Russian offensive, which is under way as we speak, in the eastern part of Ukraine. There is the makings of a Russian offensive under way, with some of those hundreds of thousands of conscripts who got brought in. So when do we get to the point where we understand that it is E.U. accession, reconstruction, bringing people home to live—the end of hostilities in some form—to build a Ukraine, a peacetime Ukraine, on some version of Ukrainian territory, which doesn’t concede that the rest of the territory is no longer Ukrainian territory, even if they don’t control it?

Let’s remember a divided Berlin, and East and West Germany. You lived through that. Nobody thought that would happen, but it was the right thing to do: to build a successful West Germany, integrated into Europe with a nato security guarantee. You can look at that as decades and decades of commitment, but also success. You can look at the Korean Peninsula as a worse situation because it’s still divided.

People talk about the Cold War being over. It sort of is—except for the places where it’s not. And so that outcome is suboptimal. The better outcome is a Russia that looks like France. That is to say, it’s a regular big country, that behaves under rule of law and international norms, and is proud of its own culture, and has a large army but doesn’t threaten its neighbors, and wants to live peacefully in the region in which it’s in. That would be a great outcome. Let’s hope that we see that outcome for the Russian people, as much as for their neighbors. But, until we see that outcome, what are we going to do?

Say Ukraine takes back some of its territory—this spring and summer, maybe. And then, two years from now, there’s another Russian gear-up, to something else that might happen. How do we prevent ourselves from having hostilities continue indefinitely? Which I’m not sure they can, given our industrial base when it comes to production of weaponry. We have other priorities—as we should, as a country—where we want to expend taxpayer funding and resources, and build, and do a lot of things that your staff writers write about all the time in your magazine. And so I’m in favor of a Ukrainian victory. I’m against the Russian victory. But I’m defining a Ukrainian victory within the circumstances in which we live.

Let’s say there is such a settlement. Where does that leave Russia? Where does that leave a Putin regime?

Slobodan Milošević—you’ll remember him as the former tin-pot dictator in Serbia––lost four wars before he was kicked out. Four wars. So maybe the Putin regime experiences some domestic turbulence if it’s unable to achieve its maximal war aims. Maybe he survives—he lasts for a while. Russian power going forward degrades even further. Their status as an energy superpower degrades. Their status as a junior partner in a grand Chinese Eurasia gets more dependent, provided the Chinese will accept Russia as a junior partner. Russia’s hemorrhaging human capital. The whole new economy fled Russia.

All the I.T. people, called ITshniki.

They’re all gone.

In the tens of thousands, hundreds of thousands.

They have no future there. The Ukrainian ones are still there. They’re the brilliant people running the social-media side of the defense ministry. They’re the ones re-rigging those drones—commercial drones, bought off the shelf for ninety-nine dollars, that they attach a catapult and a grenade to. Those Ukrainian twentysomething-year-olds—and in some cases teen-agers—are still in Ukraine, many of them. And they’re on the side of their country. Russia has lost those people at least for the time being, but maybe for a generation or more.

That kind of cosmopolitan, urban life in Russia that you saw is gone.

And so we have a Russia which looks more and more like the Putin regime as a society, not just as a regime, potentially. We have all the flotsam of the xenophobic hard right in Russia complaining that the war is not being fought properly, wanting to nuke Ukraine, nuke the West, as they go on social media and express the extremism that unfortunately social media facilitates and encourages. And so that’s the Russia we have already. Russia has already been transformed utterly. Wars are transformational in all ways.

This war is just—it’s so painful. My whole life was writing about Stalin, and I would get absorbed in that. But then I put that down, and I had kids to hug, and I had a wife who loved me, and I had students that I could harangue in the classroom. Now I put the Stalin thing down—and then I got the Stalin thing again. In the real world. In real time. So it hurts. This whole thing hurts a lot. There’s no relief from this part of the world. ♦

New Yorker Favorites

In the weeks before John Wayne Gacy’s scheduled execution, he was far from reconciled to his fate.

What HBO’s “Chernobyl” got right, and what it got terribly wrong.

Why does the Bible end that way?

A new era of strength competitions is testing the limits of the human body.

How an unemployed blogger confirmed that Syria had used chemical weapons.

An essay by Toni Morrison: “The Work You Do, the Person You Are.”

Sign up for our daily newsletter to receive the best stories from The New Yorker.

David Remnick has been editor of The New Yorker since 1998 and a staff writer since 1992. He is the author of “The Bridge: The Life and Rise of Barack Obama.”

More:Vladimir PutinVolodymyr ZelenskyUkraineRussiaEuropean UnionWars

The Daily

The best of The New Yorker, every day, in your in-box, plus occasional alerts when we publish major stories.

E-mail address

Sign up

By signing up, you agree to our User Agreement and Privacy Policy & Cookie Statement.

Read More

Daily Comment

How Do Ukrainians Think About Russians Now?

After a year of war, the struggle for cultural sovereignty has triggered complex sentiments.

By Jon Lee Anderson

Comment

Sliding Toward a New Cold War

Not since the Berlin Wall fell has the world been cleaved so deeply by the kind of conflict that John F. Kennedy called a “long, twilight struggle.”

By Evan Osnos

The Political Scene Podcast

A Year of War in Ukraine

David Remnick talks with the historian Stephen Kotkin and the Kyiv-based journalist Sevgil Musaieva about a year of disaster, and what a Ukrainian victory would look like.

Essay

Russia, One Year After the Invasion of Ukraine

Last winter, my friends in Moscow doubted that Putin would start a war. But now, as one told me, “the country has undergone a moral catastrophe.”

By Keith Gessen

Limited-time offer.

Get 12 weeks for $29.99 $6, plus a free tote.SubscribeCancel anytime.

Sections

News

Books & Culture

Fiction & Poetry

Humor & Cartoons

Magazine

Crossword

Video

Podcasts

Archive

Goings On

More

Customer Care

Shop The New Yorker

Buy Covers and Cartoons