#Lender's Policy

Text

Insurance: Protecting Your Real Estate Investment

When you purchase a home or any piece of real estate, it's a significant investment, both financially and emotionally. You spend countless hours searching for the perfect property, secure a mortgage, and go through the intricate process of closing the deal. While you're likely aware of the importance of homeowner's insurance, there's another type of insurance that often goes overlooked but plays a vital role in safeguarding your investment: title insurance.

What is Title Insurance?

Title insurance is a specialized form of insurance that protects homeowners and lenders from financial losses related to defects in a property's title. A property's title is a legal document that establishes ownership and the right to use and possess the property. It also includes any claims or liens against the property, such as unpaid taxes, mortgages, or easements.

When you buy a property, you want to be certain that the seller has a clear and marketable title, which means there are no legal issues that could affect your ownership rights. Title insurance ensures that you are protected if any hidden title defects or legal problems arise after the purchase.

Why Do You Need Title Insurance?

Protection Against Unknown Title Issues: Title insurance provides you with protection against any undiscovered title problems that may arise in the future. Even a meticulous title search can't guarantee that every potential issue will be uncovered. Title insurance offers peace of mind, knowing that you won't be financially responsible for addressing these issues.

2. Safeguarding Your Investment: Your home is likely one of the most significant investments you'll ever make. Title insurance helps protect your investment by minimizing the risk of unexpected title disputes that could result in financial loss or even the loss of your property.

For more information visit → learnwithvm.com

#Title Insurance#Real Estate Investment#Homeownership#Property Ownership#Title Issues#Legal Protection#Lender's Policy#Owner's Policy#Real Estate Closing#Title Search#Title Defects#Mortgage Protection#Hidden Title Problems#Clear Title#Real Estate Transaction#Title Company#Title Examination#Title Policy#Title Search Process#Closing Costs

1 note

·

View note

Text

I had to tell a student last week that we couldn't find a lender for the book she requested (it was noncirculating at the libraries who do have it), and what does she do SHE REQUESTS IT AGAIN TODAY girl, the answer is still going to be no. I'm sorry.

#random personal stuff#it's not that we don't WANT to provide this book#but we don't control the lenders and their policies#there have to be plenty of other far more accessible sources on this topic

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Molly McGhee’s “Jonathan Abernathy You Are Kind”

Jonathan Abernathy You Are Kind is Molly McGhee's debut novel: a dreamlike tale of a public-private partnership that hires the terminally endebted to invade the dreams of white-collar professionals and harvest the anxieties that prevent them from being fully productive members of the American corporate workforce:

https://www.penguinrandomhouse.com/books/734829/jonathan-abernathy-you-are-kind-by-molly-mcghee/

Though this is McGhee's first novel, she's already well known in literary circles. Her career has included stints at McSweeney's, where she worked on my book Information Doesn't Want To Be Free:

https://store.mcsweeneys.net/products/information-doesn-t-want-to-be-free

And then at Tor Books, where she worked on my book Attack Surface:

https://us.macmillan.com/books/9781250757531/attacksurface

But though McGhee is a shrewd and skilled editor, I think of her first and foremost as a writer, thanks to stunning essays like "America's Dead Souls," a 2021 Paris Review piece that described the experience of multigenerational debt in America in incandescent, pitiless prose:

https://www.theparisreview.org/blog/2021/05/17/americas-dead-souls/

McGhee's piece struck at the heart of something profoundly wrong in American society – the dual nature of debt, which represents a source of freedom for the wealthy, and bondage for workers:

https://pluralistic.net/2021/05/19/zombie-debt/#damnation

When billionaire mass-murderers like the Sacklers amass tens of billions of liabilities stemming from their role in deliberately starting the opioid crisis, the courts step in to relieve them of their obligations, allowing them to keep their blood-money:

https://pluralistic.net/2023/08/11/justice-delayed/#justice-redeemed

And when Silicon Valley Bank collapses due to mismanagement by ultra-wealthy financiers, the public purse yawns open and billions flow out to ensure that the wealthiest investors in the country stay whole:

https://pluralistic.net/2023/03/18/2-billion-here-2-billion-there/#socialism-for-the-rich

When predatory payday lenders target working people and force them into bankruptcy with four-digit APRs, the government intervenes…to save the lenders and keep workers on the hook:

https://pluralistic.net/2022/01/29/planned-obsolescence/#academic-fraud

"Debtor vs creditor" is the oldest class division we have. The Bronze Age custom of jubilee – the periodic cancellation of all debts – wasn't some weird peccadillo. It was essential public policy, and without jubilee, the hereditary creditor class became the arbiter of all social priorities, destabilizing great nations and even empires by directing production to suit their parochial needs. Societies that didn't practice jubilee (or halted it) collapsed:

https://pluralistic.net/2022/07/08/jubilant/#construire-des-passerelles

Today's workers are debt burdened at scales and in ways that defy comprehension, the numbers are so brain-breakingly large. Students who take out modest loans and pay them off several times over remain indebted decades later, with outstanding balances that vastly outstrip the principle:

https://pluralistic.net/2020/12/04/kawaski-trawick/#strike-debt

Workers who quit dead-end jobs are billed for five-figure "training repayment" bills that haunt them to the end of days:

https://pluralistic.net/2022/08/04/its-a-trap/#a-little-on-the-nose

Hospitals sue indigent patients at scale, siccing debt-collectors on people who can't pay – and were entitled to free care to begin with:

https://armandalegshow.com/episode/when-hospitals-sue-patients-part-2/

And debt collectors are drawn from the same social ranks as the debtors, barely trained and unsupervised, engaging in lawless, constant harassment of the debtor class:

https://pluralistic.net/2023/08/12/do-not-pay/#fair-debt-collection-practices-act

McGhee's "American Dead Souls" crystallized all of this vast injustice into a single, beautiful essay – and then McGhee crystallized things further by posting a public resignation letter enumerating the poor pay and working conditions in New York publishing, triggering mass, industry-wide resignations by similarly situated junior editorial staff:

https://electricliterature.com/molly-mcghee-jonathan-abernathy-you-are-kind-interview-debut-novel-book-debt/

Thus we arrive at McGhee's debut: a novel written by someone with a track record for gorgeous, brutally insightful prose; incisive analysis of the class war raging in the embers of capitalism's American Dream; and consequential labor organizing against the precarity and exploitation of young workers. As you might expect, it's fantastic.

Jonathan Abernathy is a 25 year old, debt haunted, desperately lonely man. An orphan with a mountain of college debt, Abernathy lives in a terrible basement apartment whose rent is just beyond his means. The only thing that propels him out of bed and into the world are his affirmations:

Jonathan Abernathy you are kind

You are well respected and valued by your community

People, including your family, love you

That these are all easily discerned lies is beside the point. Whatever gets you through the night.

We meet Jonathan as he is applying for a job that he was recruited for in a dream. As instructed in his dream, he presents himself at a shabby strip-mall office where an acerbic functionary behind scratched plexiglass takes his application and informs him that he is up for a gig run jointly by the US State Department and a consortium of large corporate employers. If he is accepted, all of his student debt repayments will be paused and he will no longer face wage garnishment. What's more, he'll be doing the job in his sleep, which means he'll be able to get a day job and pull a double income – what's not to like?

Jonathan's job is to enter the dreams of sleeping middle-management types in America's largest firms – but not just any dreams, their nightmares. Once he has entered their nightmare, Jonathan is charged with identifying the source of their anxiety and summoning a more senior operative who will suck up and whisk away that nagging spectre, thus rendering the worker a more productive component of their corporate structure.

But of course, there's more to it. As Jonathan works through his sleeping hours, he is deprived of his own dreams. Then there's the question of where those captive anxieties are ending up, and how they're being processed, and what new products can be made from refined nightmares. While Jonathan himself is pulling ever so slightly out of his economic quagmire, the people around him are still struggling.

McGhee braids together three strands: the palpable misery of being Jonathan (a proxy for all of us), the rising terror of the true nature of his employment, and beautifully turned absurdist touches that are laugh-aloud funny. This could be a mere novel of ennui and misery but it's not – it's a novel of hilarity and fear and misery, all mixed together in a glorious and terrible concoction that is not like anything else you've ever read.

If you'd like an essay-formatted version of this post to read or share, here's a link to it on pluralistic.net, my surveillance-free, ad-free, tracker-free blog:

https://pluralistic.net/2024/01/08/capitalist-surrealism/#productivity-hacks

#pluralistic#books#reviews#science fiction#molly mcghee#debt#graeber#capitalist realism#capitalist surrealism#dreams#gift guide

78 notes

·

View notes

Text

TWO YEARS AGO, by a series of strange coincidences, I found myself attending a garden party at Westminster Abbey. I was a bit uncomfortable. It’s not that other guests weren’t pleasant and amicable, and Father Graeme, who had organized the party, was nothing if not a gracious and charming host. But I felt more than a little out of place. At one point, Father Graeme intervened, saying that there was someone by a nearby fountain whom I would certainly want to meet. She turned out to be a trim, well-appointed young woman who, he explained, was an attorney—“but more of the activist kind. She works for a foundation that provides legal support for anti-poverty groups in London. You’ll probably have a lot to talk about.”

We chatted. She told me about her job. I told her I had been involved for many years with the global justice movement—“anti-globalization movement,” as it was usually called in the media. She was curious: she’d of course read a lot about Seattle, Genoa, the tear gas and street battles, but … well, had we really accomplished anything by all of that?

“Actually,” I said, “I think it’s kind of amazing how much we did manage to accomplish in those first couple of years.”

“For example?”

“Well, for example, we managed to almost completely destroy the IMF.”

As it happened, she didn’t actually know what the IMF was, so I offered that the International Monetary Fund basically acted as the world’s debt enforcers—“You might say, the high-finance equivalent of the guys who come to break your legs.” I launched into historical background, explaining how, during the ’70s oil crisis, OPEC countries ended up pouring so much of their newfound riches into Western banks that the banks couldn’t figure out where to invest the money; how Citibank and Chase therefore began sending agents around the world trying to convince Third World dictators and politicians to take out loans (at the time, this was called “go-go banking”); how they started out at extremely low rates of interest that almost immediately skyrocketed to 20 percent or so due to tight U.S. money policies in the early ’80s; how, during the ’80s and ’90s, this led to the Third World debt crisis; how the IMF then stepped in to insist that, in order to obtain refinancing, poor countries would be obliged to abandon price supports on basic foodstuffs, or even policies of keeping strategic food reserves, and abandon free health care and free education; how all of this had led to the collapse of all the most basic supports for some of the poorest and most vulnerable people on earth.

I spoke of poverty, of the looting of public resources, the collapse of societies, endemic violence, malnutrition, hopelessness, and broken lives.

“But what was your position?” the lawyer asked.

“About the IMF? We wanted to abolish it.”

“No, I mean, about the Third World debt.”

“Oh, we wanted to abolish that too. The immediate demand was to stop the IMF from imposing structural adjustment policies, which were doing all the direct damage, but we managed to accomplish that surprisingly quickly. The more long-term aim was debt amnesty. Something along the lines of the biblical Jubilee. As far as we were concerned,” I told her, “thirty years of money flowing from the poorest countries to the richest was quite enough.”

“But,” she objected, as if this were self-evident, “they’d borrowed the money! Surely one has to pay one’s debts.”

It was at this point that I realized this was going to be a very different sort of conversation than I had originally anticipated. Where to start? I could have begun by explaining how these loans had originally been taken out by unelected dictators who placed most of it directly in their Swiss bank accounts, and ask her to contemplate the justice of insisting that the lenders be repaid, not by the dictator, or even by his cronies, but by literally taking food from the mouths of hungry children. Or to think about how many of these poor countries had actually already paid back what they’d borrowed three or four times now, but that through the miracle of compound interest, it still hadn’t made a significant dent in the principal. […]

But there was a more basic problem: the very assumption that debts have to be repaid. Actually, the remarkable thing about the statement “one has to pay one’s debts” is that even according to standard economic theory, it isn’t true. A lender is supposed to accept a certain degree of risk. If all loans, no matter how idiotic, were still retrievable—if there were no bankruptcy laws, for instance—the results would be disastrous. What reason would lenders have not to make a stupid loan?

[…] For several days afterward, that phrase kept resonating in my head. “Surely one has to pay one’s debts.” The reason it’s so powerful is that it’s not actually an economic statement: it’s a moral statement. After all, isn’t paying one’s debts what morality is supposed to be all about? Giving people what is due them. Accepting one’s responsibilities. Fulfilling one’s obligations to others, just as one would expect them to fulfill their obligations to you. What could be a more obvious example of shirking one’s responsibilities than reneging on a promise, or refusing to pay a debt?

It was that very apparent self-evidence, I realized, that made the statement so insidious. This was the kind of line that could make terrible things appear utterly bland and unremarkable. This may sound strong, but it’s hard not to feel strongly about such matters once you’ve witnessed the effects. I had. For almost two years, I had lived in the highlands of Madagascar. Shortly before I arrived, there had been an outbreak of malaria. It was a particularly virulent outbreak because malaria had been wiped out in highland Madagascar many years before, so that, after a couple of generations, most people had lost their immunity. The problem was, it took money to maintain the mosquito eradication program, since there had to be periodic tests to make sure mosquitoes weren’t starting to breed again and spraying campaigns if it was discovered that they were. Not a lot of money. But owing to IMF-imposed austerity programs, the government had to cut the monitoring program. Ten thousand people died. I met young mothers grieving for lost children. One might think it would be hard to make a case that the loss of ten thousand human lives is really justified in order to ensure that Citibank wouldn’t have to cut its losses on one irresponsible loan that wasn’t particularly important to its balance sheet anyway. But here was a perfectly decent woman—one who worked for a charitable organization, no less—who took it as self-evident that it was. After all, they owed the money, and surely one has to pay one’s debts.

Debt, the First 5000 Years

51 notes

·

View notes

Text

Holy fuck they are hawking this bullshit again about high mortgage rates being racist

Borrowing costs for mortgages have more than doubled over the last two years as the Federal Reserve has battled inflation by hiking interest rates, which hit a 22-year high earlier this year. […]

The Financial Services Forum, representing eight of the biggest U.S. banks, said it is spending a seven-figure sum on television advertising blasting the proposal as an added fee on Americans already burdened by inflation.

“The fed has hiked interest rates to reduce inflation, and also as the Evil League of Evil points out, these high interest rates exacerbate the problem of inflation.” Could you try to hide the doublethink a bit harder?

After George Floyd’s murder ignited nationwide protests in the summer of 2020, corporations across the economy committed to projects aimed at battling systemic racism. Mortgage lenders pledged to work with financial regulators to provide credit to more minority borrowers.

“To honour the death of George floyd, we need to use interest rates to hike housing values.” Shameless. Just fucking shameless.

Then again, if she extends the lease on her two-bedroom apartment — where her 11-year-old son is sharing a bedroom with his 22-year-old brother — her rent will increase by $70 a month, to nearly $1,400.

“To hear costs just keep going up is really disheartening,” she said. “Where do they want people to live?”

If the problem this woman is facing is that the rent is too damn high, I think the natural thing to do would be to focus on policies with the ability to make the rent less damn high. But no, increasing homeownership forever at all costs is clearly the only solution, which actually dovetails with instead of flatly contradicting addressing the problem of rentiers being able to extort more money from their tenants bc of their high property values

Sen. Sherrod Brown (D-Ohio), who chairs the Senate Banking Committee, struck an incredulous tone over the industry’s lobbying push as the bank CEOs testified before the panel Wednesday.

“Wall Street banks are actually saying that cracking down on them will, quote, ‘hurt working families.’ Really?” he asked. “You’re going to claim that?”

Love that the obligatory “And now we will give coverage to the other side” section is just sherrod brown saying “Sorry do u expect me to actually swallow this tripe?” Lol

40 notes

·

View notes

Note

If the King/Queen of Westeros decided to implement a national bank of Westeros, how would they navigate relationships with the Iron Bank and any perceived competition? Thinking of the same way that the Rogare Bank might have fallen to Faceless Man assassinations?

I would personally recommend a more cooperative policy, because there are definite ways that a Westerosi central bank could be of benefit to the Iron Bank - especially since central banks don't tend to compete with merchant or commercial banks for the same kind of business.

To begin with, the existence of a central bank acting as lender of last resort to Westerosi moneylenders and merchants is going to be good for the Iron Bank's business in Westeros, because that's going to massively reduce the risk of default, which would mean the Iron Bank's loans would see a higher rate of return even at lower interest rates, and likely would lead to an increased volume of business, as more people would be able to afford to take out loans from the Iron Bank.

If the Westerosi central bank is anything like the central banks of Early Modern Europe, it might be quite possible that the Iron Bank would become a minority shareholder in the Westerosi central bank, and quite likely would be one of the central bank's major customers when it comes to the sale of royal bonds - if only because the existence of a central bank would make Westerosi public debt a much sounder investment than under the medieval model.

#asoiaf#asoiaf meta#westerosi economic policy#medieval finance#medieval economics#iron bank#medieval banking#early modern state-building#early modern finance#central banking

35 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ok I should do an actual thoughtful post on this but instead I’m just gonna go off on a ramble. (I’m not a historian or a financial expert btw)

So I have always been interested in the discrepancy between Mitya’s assertion to Alyosha near the beginning that Grushenka “liked to make a bit of dough and made it by lending at wicked rates of interest, the cunning vixen, the rogue, without mercy.” (McDuff translation 1.3.5) and the narrator’s assertion in 3.7.3 “Not that she ever lent money on interest”. At first I chalked it up to Mitya just making assumptions about her, since he does say some things that are incorrect (for instance that Samsonov will leave her a considerable sum of money when he dies, when it is well known that he said he wouldn’t and, sure enough, did not even mention her in the will). However, I did think it was odd that a profit-motivated professional moneylender would never lend money on interest, and it feels even more odd now that I know there was a legal annual interest limit (6%). If it was legal to lend on interest, why wouldn’t she?

Well. I’m now reading the very fascinating Bankrupts and Usurers of Imperial Russia: Debt, Property, and the Law in the Age of Dostoevsky and Tolstoy by Sergei Antonov. And it’s fascinating getting context on all of this—and, bear in mind, context that Dostoevsky’s audience would have taken for granted.

There were a lot of regulatory laws that existed around moneylending and debt collecting, as usury was extremely frowned-upon legally, religiously, and socially. But these laws were very difficult to enforce, especially since moneylenders had all kinds of ways of skirting around them and hiding their more predatory practises. Besides, according to the above-mentioned reference work, “even at the highest levels the government realized that it was both impossible and undesirable to eliminate interest rates that exceeded the legally mandated maximum.” So, Antonov goes on to relate:

For example, an 1861 memo prepared by one of the tsar’s closest aides and a general in the Corps of Gendarmes, Ivan Annenkov, recognized that usurers in Russia enjoyed “complete immunity” but urged that “we must not [condemn as usurers] all persons who loan money for interest, even if under private agreements such interest would exceed the limit defined by the law. Everybody knows that no one has so far placed his capital in private hands in return for the legal 6% . . . [government’s policies] must not touch upon those private obligations and conditions that are founded upon mutual benefit.” Annenkov proposed a systematic procedure of identifying as many individual lenders as possible and then focusing on those known to engage in particularly abusive practices.

So this guy was like “yeah, even though what they’re doing is technically not legal, we kind of agree with it actually, and so instead of going after people based on the letter of the law, let’s just keep an eye on known moneylenders and go after the ones who are really crossing the line and hurting people.

Which meant that the police did keep detailed records of known moneylenders, and to the shock of absolutely no one, the notes beside the names in these records were heavily interested in the personal character of each lender. Political leanings, religion, whether they had a family, whether they were landowners, their morals and conduct, etc. I’m sure none of this led to any kind of discrimination in terms of who was allowed to get away with predatory moneylending practises and who was prosecuted for the very same. (Heavy sarcasm)

Since Grushenka did not have a powerful family behind her and was widely known to be a fallen woman and Kuzma Samsonov’s mistress (despite the fact that she was definitively known not to be promiscuous and to reject the advances of any other men who tried it), it’s very likely to me that she would be under special scrutiny, especially in a small town where there weren’t as many moneylenders to keep an eye on as there were in, say, St. Petersburg. Given that she received a lot of business advice from Samsonov, and some of this advice might very likely have included those methods of getting away with practises of dubious legality without leaving a paper trail, and given the necessity of her being extra careful in order not to be prosecuted, it would make sense that the narrator (being himself a character and resident of the town, and thus only able to report things to us based on the information he has available and how it appears to him,) would not have any information or records available to him which would suggest that she was lending on interest at all, let alone above the legal rates. Given the strong negative feelings against usury, making such an accusation or implication without evidence would be highly slanderous, and the narrator would be unwise to risk that, thus his statement that Grushenka did not lend on interest at all.

Whereas it is possible that, given Mitya’s close association with Grushenka during the past month and the fact that she does confide some things in him (her feelings about Alyosha, letting him read the letter her officer sent, laughing about Fyodor’s scheme to have him jailed, etc.), he may have known something the narrator didn’t. Of course, it’s also possible that he was just making an assumption that happened to be correct, or at least more plausible than the narrator’s.

And I think that Dostoevsky meant for the narrator’s assertion that she never lent on interest to seem highly improbable, even implausible, given that his audience would have been very familiar with the widespread business of moneylending across all classes of society, and how it operated. Again, if there was a legal maximum interest rate, and plentiful ways to get away with illegally lending above that maximum rate, then why would a professional moneylender consistently lend money on no interest at all? She would at the very least be lending on legal rates to make a profit off of the interest, and more than likely at illegal rates as well, simply taking care to do so covertly. And I think the original audience would have understood this implicitly.

Hope this was somewhat coherent.

#grushenka and her capitalist hashtag-girlboss crimes#the brothers karamazov#grushenka#agrafena alexandrovna svetlova#kuzma kuzmich samsonov#tbk#russian lit#russian literature#russian history#historical context#tbk meta#братья карамазовы#brothers karamazov#fyodor dostoevsky#dostoevsky#imperial russia#moneylending in imperial russia#ruslit

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Poverty is a policy choice

The Atlantic has an unflinching look at how the US is such a bad actor when it comes to poverty, especially child poverty, compared to the rest of the developed world. President Biden's Extended Child Tax Credit passed in his first year in office lifted 40% of the families living in poverty out of poverty, a stunning result achieved at a relatively small cost. The Republicans killed it.

There are tremendous knock-on benefits to lifting people out of poverty - healthcare costs go down, crime goes down, tax bases are widened, welfare rolls are reduced, productivity goes up. All these are well known. So why does America fall so short? Here are a few points from the article to consider:

Housing is typically the largest expense for a household. “Municipal zoning ordinances, enacted through referenda pushed by citizens’ groups and homeowners’ associations, and which prohibit the construction of multifamily apartment complexes in upscale neighborhoods, is a case in point. These benign-sounding rules foster segregation, effectively preventing the poor ... from moving in. Such policies are one of the few issues that Americans in red and blue states seem to agree on."

So yes, the NIMBY effect of the 'rich' forces the poor to live out of sight, unable to benefit from the schools, parks, and appreciation in property values enjoyed by the wealthy.

The financial structure favours the wealthy in a variety of ways. "When the wealthy patronize shops and restaurants that offer low prices and fast service, their satisfaction comes at the expense of cashiers and dishwashers paid poverty wages. When we open free checking accounts that require maintaining a minimum balance, we benefit from the fact that banks can collect billions of dollars in overdraft fees from poor customers who struggle to meet these requirements—and who often end up gouged by check-cashing outlets and payday lenders."

The notion that the government subsidizes the poor while taxing the rich does not take into consideration the massive tax benefits homeowners have with the mortgage interest deduction and state and local tax write-offs. Indeed, "the average household in the top 20 percent income bracket receives $35,363 in annual tax breaks and other government benefits—40 percent more than the average household in the bottom 20 percent."

"What is “maddening,” Desmond writes, is “how utterly easy it is to find enough money to defeat poverty by closing nonsensical tax loopholes,” or by doing 20 or 30 smaller things to curtail just some of the subsidies of affluence."

His bleak conclusion:

"Getting affluent people to engage in rhetorical hand-wringing over inequality is easy enough. Persuading them to yield some of their entitlements is a lot harder."

122 notes

·

View notes

Text

Establishment of an international commission for the audit of illegitimate foreign debt.

*translation (me and google) of the goals and politics of RF (Workers Front), croatian marxist party. its a long read but its very good, it goes into eu colonialism, effects of imperial core on periphery countries etc.

The debt of the Republic of Croatia should be (partially or completely – depending on the possibilities) frozen, reprogrammed and cancelled, and an international commission should be established, following the example of Ecuador and the existing world practice, which will establish the proportion of illegitimate foreign debt in it, i.e. debt that previous authorities (in cooperation with lenders) did illegitimately, without asking the people for their opinion and without taking into account the interests of the majority of society.

One of the biggest problems that plagues many countries, especially on the periphery of world capitalism, is debt repayment (as a rule, to banks, institutions and individuals from the most developed countries of the capitalist core).

Countries on the periphery are often forced to borrow precisely because of the imposition of economic policies imposed on them by the authorities and capital of the countries of the capitalist core, through instruments such as the International Monetary Fund, the World Bank, the World Trade Organization (WTO), the European Union, etc.

Thus, through the establishment of "free trade" (in which the stronger and bigger always win) and often the entry of "foreign investments", the domestic industry, natural resources and agriculture of peripheral countries are destroyed, while imports and dependence on foreign economies increase. The deficit that arises after the destruction of domestic production is then compensated by borrowing on the foreign market, often in such a way that the debts are practically impossible to repay and that entire countries are condemned to permanent indebtedness, which clearly benefits those who give loans because, apart from getting rich on it without any work, provides a tool for further political pressure.

This then leads to the fact that the entire economies of countries on the periphery, again under political pressure from the most developed countries (i.e. their capitalist class), are organized in such a way that everything is subordinated to (futile) debt repayment or reforms that benefit foreign capital, and what else then it prevents the development of the indebted countries of the periphery (the governments of the countries of the capitalist core also borrow, but in such cases it works differently because they and their capital are dominant in world power relations).

The question that arises here is whether it is fair that the return of debts to a handful of usurious institutions and individuals in the most developed countries is presupposed to the development of less developed and underdeveloped countries and the interests of the majority of society in these countries?

Is it more important, for example, that an individual country has enough money for its health and education, or is it more important that the loaned money be returned to Wall Street with interest and on time?

In addition, the question arises whether it is legitimate to impose on the entire society to pay back debts that, among other things, arose as a result of the economic policy imposed by the same circles to whom the debt is owed. Is it fair that entire countries live in misery because some government, elected in who knows what way, concluded a loan agreement (often on unfavorable terms) and for who knows what purposes? Considering that such loans have never been voted on in popular referendums, can the entire society be considered forever responsible for their return? In the end - why should the question of repaying debts depend only on the one who received the money, and not on the one who lent it to someone? Doesn't the person who lends money bear a certain risk?

Why should entire countries remain in debt slavery for years just because, for example, certain foreign banks decided to make money by lending funds that they knew in advance that the respective countries would hardly (if ever) be able to pay back? Why would Croatia have to repay the debts incurred by the government of Ivo Sanader, the former prime minister now in prison for corruption, for years to come?

Such questions are not just pure theory - in practice and international law, there has been an institution of the so-called illegitimate debt precisely in the cases we were talking about. If, for example, it is concluded that the money was lent by a corrupt government under deliberately unfavorable conditions and that the lender was aware of this, it is perfectly legitimate for the loan not to be repaid, or at least not to be repaid in full.

In view of this, and based on the already existing world practice, the Workers' Front advocates the establishment of an international commission to review the illegitimate foreign debt of the Republic of Croatia (as Ecuador recently did and as SYRIZA is planning for Greece). After the audit in question, it would be seen how much of the (illegitimate) debt can be canceled, frozen or rescheduled, in whole or in part. Canceling or freezing the payment of at least part of the debts would enable the redirection of funds for the development of the country and for social welfare.

Of course, it is unnecessary to specially mention that here too the matter should be carried out in a realpolitik wise, making various tactical political alliances around the world and minimizing potential damage.

Joint struggle with labor and social movements around the world to cancel the debts and interest on the debts of less developed countries. Drastic reduction of internal debts in all countries, except for small depositors up to a certain amount, and the use of the freed money to meet basic social needs.

The debt problem is not only a problem for Croatia, but also for a large part of the world. Therefore, in solving it, one must try to work together with other progressive governments (today, primarily some Latin American countries, and in the future maybe some others), as well as with various progressive social movements around the world that are not in power. Thus, pressure could be exerted jointly from below (e.g. through protests, public campaigns, etc.) to cancel the debts of less developed and indebted countries. Such a struggle, in order to succeed, must be international.

In addition, debt problems need to be solved within the country as well. There are currently around 315,000 blocked people in Croatia. The debts of ordinary people and workers should be immediately canceled and/or reduced, thus making life easier for those whose basic existence is threatened.

In cooperation with labor and social movements in other countries, the fight to build a world system where high production technology will not be limited only to the most developed Western countries, but will be systematically and at low prices transferred to less developed countries.

The struggle for a post-capitalist world cannot be limited to just one country. Progressive forces in the world must work together to build a more socially just world economic system that will be based not on competition and the wealth of the minority and the poverty of the majority, but on the cooperation and planned development of all countries. It is completely clear that there will be many problems in the process and that this goal will not be achieved in the near future.

The current EU functions primarily in the interests of large capital in the developed Western European core. Therefore, it should be disbanded and a new united workers' Europe built on the foundations of equality, solidarity and an economy that works for the benefit of the majority of society, and in cooperation with other progressive forces of all European countries.

In an attempt to realize its anti-capitalist program, the Workers' Front firmly stands on internationalist positions, realizing that the struggle against the dictatorship of capital cannot take place within the borders of just one country. Therefore, it is completely clear that the struggle for a fairer society, as we strive for, cannot take place without cooperation with progressive forces from other countries in Europe and, ultimately, the entire world.

It is therefore completely clear that the Workers' Front is not in favor of closing Croatia within its borders, but that it supports the idea of a united Europe (and in a broader framework than the framework of the currently existing EU) on the progressive foundations of cooperation, solidarity and an economy that would work in the interests of the majority of society.

But the European Union is not an idyllic union of European unity that works for the betterment of the entire European population. Today, the EU is, above all, a neoliberal project, under whose auspices an extremely pro-capitalist policy is conducted, primarily in the interest of large Western European capital (from countries such as Germany, Austria, Scandinavia, the Netherlands, etc.), and to the detriment of peripheral and semi-peripheral countries (such as are Croatia, Slovenia, Greece, Bulgaria, Romania, but to a large extent also larger countries such as Spain, Portugal and Italy) and generally the working majority of the entire EU.

Such political orientation of the EU is clearly seen in the recent insistence of the EU on austerity measures, in which the costs of the great global crisis of 2007-8. year, they are beaten exclusively on the backs of the workforce, while favors to capital continue. In addition, there are increasingly obvious tendencies to increase the democratic deficit in the EU, where more and more powers are transferred to the largely unelected structure of the Eurobureaucracy, and even the little limited democracy that exists within the framework of capitalist liberal democracy is ignored. In the same way, the EU institutions have been promoting policies for some time, especially since the beginning of the 2007-8 crisis, which tend to abolish acquired labor rights and "flexibilization", i.e. precarious, insecure and poorly paid work.

Considering the institutionalized neoliberalism that exists in the EU, where the EU roughly sets and controls the fiscal (budgetary), monetary and general economic policy, it is completely clear that a large part of the progressive moves highlighted in these program requirements are practically impossible to carry out within the EU (despite examples like that of Hungary, where the right-wing populist government managed to defy Brussels to a certain extent in some sectors).

It is also clear that any reindustrialization of Croatia in a completely open European free market is impossible - as examples from history show, industrialization and economic development in an open market (without protectionism towards industries in their infancy) is not possible because in a free market stronger (in (in this case, large Western European industries) always win. This became quite clear immediately after Croatia's entry into the EU - despite the fact that, according to experts' estimates, Croatia could produce food for around 25 million people, the import of milk increased by 90% after July 1, 2013. and already in the first months of membership in the EU, the import of pork increased by about 300%, and eggs by 524%.

From all this, it is clear that progressive politics, despite its necessary extremely internationalist ideological orientation, cannot and must not be enslaved by misconceptions about the EU as the realization of the dream of a united Europe - the EU is not and cannot be. Such a Europe has yet to be fought for, and on completely different, progressive economic and political grounds.

Leaving NATO membership considering that it implies questionable moral and political decisions (such as military participation in the occupation of different countries), unnecessary costs (annual membership fee and purchase of weapons) and increases uncertainty (explicit inclusion in one of the global geopolitical blocs certainly does not contribute security of the country, for example in the event of a conflict between the West and Russia or China).

Membership in NATO, contrary to the proclaimed goals, does not bring any benefits to Croatia (as well as other smaller countries in a similar position). As a member of NATO, Croatia must participate (at its own expense) in imperialist occupation "peace" missions, such as the one in Afghanistan, where the Croatian army is used to enforce the geopolitical interests of the USA and other major Western countries. The costs of participating in NATO will increase even more after 2014 due to the cooling of relations with Russia (it is required to allocate 2% of GDP to the military of each of the members), and NATO membership does not in any way increase the country's security. Namely, it is very easy to see that in any future conflict (eg between Russia and the West) it would be much safer for Croatia to stay out of the entire conflict, instead of positioning itself in one of the camps. Membership in NATO does not make Croatia safer, but becomes a potential target in conflicts in which NATO participates.

The complete openness and availability of all interstate treaties, agreements and diplomatic acts and the disbandment of existing secret services to expose the trading of social interests under the slogan of "protection of national interests".

It is a common political practice that various decisions, documents and contracts are made in secret, away from the public eye, which is especially used when it comes to unpopular and unfavorable circumstances for the majority. In the last few years, some of such practices have exposed the so-called Wikileaks affair. The same applies to the secret services, which under the slogan of "protection of national interests" actually work against the interests of the majority of society, as was recently seen with the scandals exposed by Edward Snowden. Such practices should be stopped - all documents etc. of public importance must be accessible and transparent to everyone (through publication in the media and on the Internet), while the existing secret services, which are an important tool in preserving the status quo (and which work against the interests of the majority of society ), should be disbanded.

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

When Henry VII sought his great council’s approval for a general loan, the last such exercise lay more than 40 years in the past. Nevertheless, earlier in the same year the pretender Perkin Warbeck had issued a manifesto, which pilloried inter alia King Henry’s oppressive tax policy. It was probably in response to these charges that it was decided to raise a loan that was repayable, rather than a benevolence, which was not. Indeed, as opposed to the state loans of the Lancastrian periods when creditors had only limited hope of ever recovering what they had lent, by March 1498 the bulk of the money borrowed eighteen months previously, some £49,397, had been repaid to the lenders.

— Hannes Kleineke, 'Morton's Fork'? - Henry VII's 'Forced Loan' of 1496

Yet, the state loan of 1496 did not follow exactly the blueprint of its Lancastrian precursors. In terms of its mechanics, it was a hybrid combining the characteristics of the Lancastrian state loan with some of those of the Yorkist benevolence. As in the case of the former, creditors were approached by royal letters which were subsequently followed up by panels of commissioners. As in the case of the latter, men’s ability to contribute was assessed and moral pressure applied. The king added his personal authority to the money raising effort by signing each signet letter individually, but in the localities it fell to his close associates to induce potential lenders to contribute.

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

Dirty Bank

Hundreds of students from leading UK universities have launched a “career boycott” of Barclays over its climate policies, warning that the bank will miss out on top talent unless it stops financing fossil fuel companies.

More than 220 students from Barclays’ top recruitment universities, including Oxford, Cambridge, and University College London, have sent a letter to the high street lender, saying they will not work for Barclays and raising the alarm over its funding for oil and gas firms including Shell, TotalEnergies, Exxon and BP.

Courtesy The Guardian Newspaper #barclays #dirty #banking

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

Why the Fed wants to crush workers

The US Federal Reserve has two imperatives: keeping employment high and inflation low. But when these come into conflict — when unemployment falls to near-zero — the Fed forgets all about full employment and cranks up interest rates to “cool the economy” (that is, “to destroy jobs and increase unemployment”).

An economy “cools down” when workers have less money, which means that the prices offered for goods and services go down, as fewer workers have less money to spend. As with every macroeconomic policy, raising interest rates has “distributional effects,” which is economist-speak for “winners and losers.”

Predicting who wins and who loses when interest rates go up requires that we understand the economic relations between different kinds of rich people, as well as relations between rich people and working people. Writing today for The American Prospect’s superb Great Inflation Myths series, Gerald Epstein and Aaron Medlin break it down:

https://prospect.org/economy/2023-01-19-inflation-federal-reserve-protects-one-percent/

Recall that the Fed has two priorities: full employment and low interest rates. But when it weighs these priorities, it does so through “finance colored” glasses: as an institution, the Fed requires help from banks to carry out its policies, while Fed employees rely on those banks for cushy, high-paid jobs when they rotate out of public service.

Inflation is bad for banks, whose fortunes rise and fall based on the value of the interest payments they collect from debtors. When the value of the dollar declines, lenders lose and borrowers win. Think of it this way: say you borrow $10,000 to buy a car, at a moment when $10k is two months’ wages for the average US worker. Then inflation hits: prices go up, workers demand higher pay to keep pace, and a couple years later, $10k is one month’s wages.

If your wages kept pace with inflation, you’re now getting twice as many dollars as you were when you took out the loan. Don’t get too excited: these dollars buy the same quantity of goods as your pre-inflation salary. However, the share of your income that’s eaten by that monthly car-loan payment has been cut in half. You just got a real-terms 50% discount on your car loan!

Inflation is great news for borrowers, bad news for lenders, and any given financial institution is more likely to be a lender than a borrower. The finance sector is the creditor sector, and the Fed is institutionally and personally loyal to the finance sector. When creditors and debtors have opposing interests, the Fed helps creditors win.

The US is a debtor nation. Not the national debt — federal debt and deficits are just scorekeeping. The US government spends money into existence and taxes it out of existence, every single day. If the USG has a deficit, that means it spent more than than it taxed, which is another way of saying that it left more dollars in the economy this year than it took out of it. If the US runs a “balanced budget,” then every dollar that was created this year was matched by another dollar that was annihilated. If the US runs a “surplus,” then there are fewer dollars left for us to use than there were at the start of the year.

The US debt that matters isn’t the federal debt, it’s the private sector’s debt. Your debt and mine. We are a debtor nation. Half of Americans have less than $400 in the bank.

https://www.fool.com/the-ascent/personal-finance/articles/49-of-americans-couldnt-cover-a-400-emergency-expense-today-up-from-32-in-november/

Most Americans have little to no retirement savings. Decades of wage stagnation has left Americans with less buying power, and the economy has been running on consumer debt for a generation. Meanwhile, working Americans have been burdened with forms of inflation the Fed doesn’t give a shit about, like skyrocketing costs for housing and higher education.

When politicians jawbone about “inflation,” they’re talking about the inflation that matters to creditors. Debtors — the bottom 90% — have been burdened with three decades’ worth of steadily mounting inflation that no one talks about. Yesterday, the Prospect ran Nancy Folbre’s outstanding piece on “care inflation” — the skyrocketing costs of day-care, nursing homes, eldercare, etc:

https://prospect.org/economy/2023-01-18-inflation-unfair-costs-of-care/

As Folbre wrote, these costs are doubly burdensome, because they fall on family members (almost entirely women), who have to sacrifice their own earning potential to care for children, or aging people, or disabled family members. The cost of care has increased every year since 1997:

https://pluralistic.net/2023/01/18/wages-for-housework/#low-wage-workers-vs-poor-consumers

So while politicians and economists talk about rescuing “savers” from having their nest-eggs whittled away by inflation, these savers represent a minuscule and dwindling proportion of the public. The real beneficiaries of interest rate hikes isn’t savers, it’s lenders.

Full employment is bad for the wealthy. When everyone has a job, wages go up, because bosses can’t threaten workers with “exile to the reserve army of the unemployed.” If workers are afraid of ending up jobless and homeless, then executives seeking to increase their own firms’ profits can shift money from workers to shareholders without their workers quitting (and if the workers do quit, there are plenty more desperate for their jobs).

What’s more, those same executives own huge portfolios of “financialized” assets — that is, they own claims on the interest payments that borrowers in the economy pay to creditors.

The purpose of raising interest rates is to “cool the economy,” a euphemism for increasing unemployment and reducing wages. Fighting inflation helps creditors and hurts debtors. The same people who benefit from increased unemployment also benefit from low inflation.

Thus: “the current Fed policy of rapidly raising interest rates to fight inflation by throwing people out of work serves as a wealth protection device for the top one percent.”

Now, it’s also true that high interest rates tend to tank the stock market, and rich people also own a lot of stock. This is where it’s important to draw distinctions within the capital class: the merely rich do things for a living (and thus care about companies’ productive capacity), while the super-rich own things for a living, and care about debt service.

Epstein and Medlin are economists at UMass Amherst, and they built a model that looks at the distributional outcomes (that is, the winners and losers) from interest rate hikes, using data from 40 years’ worth of Fed rate hikes:

https://peri.umass.edu/images/Medlin_Epstein_PERI_inflation_conf_WP.pdf

They concluded that “The net impact of the Fed’s restrictive monetary policy on the wealth of the top one percent depends on the timing and balance of [lower inflation and higher interest]. It turns out that in recent decades the outcome has, on balance, worked out quite well for the wealthy.”

How well? “Without intervention by the Fed, a 6 percent acceleration of inflation would erode their wealth by around 30 percent in real terms after three years…when the Fed intervenes with an aggressive tightening, the 1%’s wealth only declines about 16 percent after three years. That is a 14 percent net gain in real terms.”

This is why you see a split between the one-percenters and the ten-percenters in whether the Fed should continue to jack interest rates up. For the 1%, inflation hikes produce massive, long term gains. For the 10%, those gains are smaller and take longer to materialize.

Meanwhile, when there is mass unemployment, both groups benefit from lower wages and are happy to keep interest rates at zero, a rate that (in the absence of a wealth tax) creates massive asset bubbles that drive up the value of houses, stocks and other things that rich people own lots more of than everyone else.

This explains a lot about the current enthusiasm for high interest rates, despite high interest rates’ ability to cause inflation, as Joseph Stiglitz and Ira Regmi wrote in their recent Roosevelt Institute paper:

https://rooseveltinstitute.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/12/RI_CausesofandResponsestoTodaysInflation_Report_202212.pdf

The two esteemed economists compared interest rate hikes to medieval bloodletting, where “doctors” did “more of the same when their therapy failed until the patient either had a miraculous recovery (for which the bloodletters took credit) or died (which was more likely).”

As they document, workers today aren’t recreating the dread “wage-price spiral” of the 1970s: despite low levels of unemployment, workers wages still aren’t keeping up with inflation. Inflation itself is falling, for the fairly obvious reason that covid supply-chain shocks are dwindling and substitutes for Russian gas are coming online.

Economic activity is “largely below trend,” and with healthy levels of sales in “non-traded goods” (imports), meaning that the stuff that American workers are consuming isn’t coming out of America’s pool of resources or manufactured goods, and that spending is leaving the US economy, rather than contributing to an American firm’s buying power.

Despite this, the Fed has a substantial cheering section for continued interest rates, composed of the ultra-rich and their lickspittle Renfields. While the specifics are quite modern, the underlying dynamic is as old as civilization itself.

Historian Michael Hudson specializes in the role that debt and credit played in different societies. As he’s written, ancient civilizations long ago discovered that without periodic debt cancellation, an ever larger share of a societies’ productive capacity gets diverted to the whims of a small elite of lenders, until civilization itself collapses:

https://www.nakedcapitalism.com/2022/07/michael-hudson-from-junk-economics-to-a-false-view-of-history-where-western-civilization-took-a-wrong-turn.html

Here’s how that dynamic goes: to produce things, you need inputs. Farmers need seed, fertilizer, and farm-hands to produce crops. Crucially, you need to acquire these inputs before the crops come in — which means you need to be able to buy inputs before you sell the crops. You have to borrow.

In good years, this works out fine. You borrow money, buy your inputs, produce and sell your goods, and repay the debt. But even the best-prepared producer can get a bad beat: floods, droughts, blights, pandemics…Play the game long enough and eventually you’ll find yourself unable to repay the debt.

In the next round, you go into things owing more money than you can cover, even if you have a bumper crop. You sell your crop, pay as much of the debt as you can, and go into the next season having to borrow more on top of the overhang from the last crisis. This continues over time, until you get another crisis, which you have no reserves to cover because they’ve all been eaten up paying off the last crisis. You go further into debt.

Over the long run, this dynamic produces a society of creditors whose wealth increases every year, who can make coercive claims on the productive labor of everyone else, who not only owes them money, but will owe even more as a result of doing the work that is demanded of them.

Successful ancient civilizations fought this with Jubilee: periodic festivals of debt-forgiveness, which were announced when new monarchs assumed their thrones, or after successful wars, or just whenever the creditor class was getting too powerful and threatened the crown.

Of course, creditors hated this and fought it bitterly, just as our modern one-percenters do. When rulers managed to hold them at bay, their nations prospered. But when creditors captured the state and abolished Jubilee, as happened in ancient Rome, the state collapsed:

https://pluralistic.net/2022/07/08/jubilant/#construire-des-passerelles

Are we speedrunning the collapse of Rome? It’s not for me to say, but I strongly recommend reading Margaret Coker’s in-depth Propublica investigation on how title lenders (loansharks that hit desperate, low-income borrowers with triple-digit interest loans) fired any employee who explained to a borrower that they needed to make more than the minimum payment, or they’d never pay off their debts:

https://www.propublica.org/article/inside-sales-practices-of-biggest-title-lender-in-us

[Image ID: A vintage postcard illustration of the Federal Reserve building in Washington, DC. The building is spattered with blood. In the foreground is a medieval woodcut of a physician bleeding a woman into a bowl while another woman holds a bowl to catch the blood. The physician's head has been replaced with that of Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell.]

#pluralistic#worker power#austerity#monetarism#jerome powell#the fed#federal reserve#finance#banking#economics#macroeconomics#interest rates#the american prospect#the great inflation myths#debt#graeber#michael hudson#indenture#medieval bloodletters

464 notes

·

View notes

Text

Our “snapshots” are brief, structured case studies that give a taste of the many diverse ways that startups have been trying to grow into community ownership and governance, albeit with mixed results.

The snapshots range from my Colorado neighbors Namaste Solar and Trident bookstore, which converted to employee ownership, to major open-source software projects like Debian and Python, which are mini-democracies accountable to their developers. There is NIO, a Chinese electric car company whose founder set aside a chunk of stock for car-buyers, and Defector Media, a co-op founded by employees who quit their previous job in protest. There are also blockchain-based efforts, like Gitcoin and SongADAO, that have tried to make good on a new technology’s often-betrayed promises for making a more inclusive economy.

I have taken two main lessons from these snapshots so far.

1. There is widespread craving for a better kind of exit—and the creativity to back it up. Entrepreneurs, investors, users, and workers alike are all recognizing the need for a new approach, and they are trying lots of different ways to get it. They are relying on old technology and the latest innovations. They are using many different legal structures and techniques for empowering communities. The resourcefulness is pretty astonishing, really.

2. Better exits need to be easier—and this will require structural change. In just about every case, E2C attempts have faced profound challenges. They are often working at the very edge of what the law allows, because many of our laws were written to serve profit-seeking investors, not communities. Much of what communities wanted was simply not possible. Truly changing the landscape of exits will mean policy change that takes communities seriously as sources of innovation and accountability.

I want to stress this second point. It first became clear to me when working with collaborators at Zebras Unite on the idea of turning Meetup into a user-owned cooperative. The founder wanted it. The business model made perfect sense—a rare platform whose users actually pay for it. The company was up for a fire sale. But we simply could not find investors or lenders prepared to back a deal like that. This is a problem I have seen with many other co-op efforts, over and over. Policy is the most powerful shaping force for where capital can aggregate, and there is no adequate policy to support capital for large-scale community ownership. This is also the reason we have lost many community-owned companies in recent years, from New Belgium Brewing to Mountain Equipment Co-op—the most successful community-owned companies too often can’t access the capital they need to flourish.

#community-owned startups#community as exit strategy#solarpunk#solarpunk business model#startups#solarpunk business

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Protip everyone if you click decline on a lender's website privacy policy then you don't have to pay back your car loan.

7 notes

·

View notes

Note

Could the Iron Throne be able to issue bonds, to finance its expenses, instead of going to the Iron Bank for a loan?

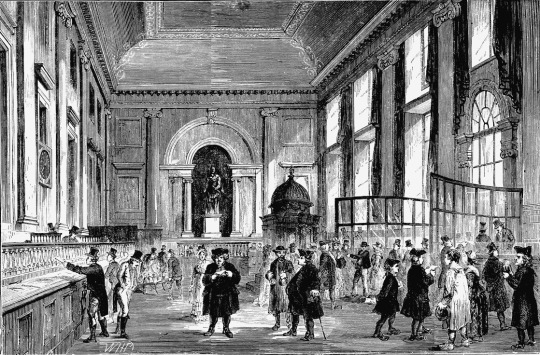

A government issuing bonds is the same thing as the government taking out a loan. The main difference is that, in the case of issuing a bond, the government is spreading out its borrowing between many lenders by selling bonds on the open market to anyone who wants to buy them rather than having that loan owed to a single entity like the Iron Bank. This means that the government is less beholden to any one creditor and it's less likely that the government's creditors can use their economic leverage to affect government policy.

The second advantage of structuring government debt through bonds is that it allows the government to break its total borrowing needs into smaller, more affordable units. Very few financial institutions would have had the capital to finance the £1,200,000 that made up the government's inaugural loan at the Bank of England in 1690 - but a lot more people could afford to lend the government £10, £25, £50, or £100 pounds.

Between this and later innovations in marketing bonds to the general public, the market for government debt was massively expanded. Not only did this create a class of rentiers who were now personally invested in the government's success, but it also immediately deepened the capital markets by creating a large supply of stable assets that could be bought and sold and borrowed against. While some of the shortcomings of the Hamilton musical and Chernow's biography have become more obvious in hindsight, they're not wrong about the impact of Hamilton's policies as Treasury Secretary on the development of the American economy.

The difficulty facing the Iron Throne in adapting an early modern system of government finance is that it doesn't have the state capacity to run this kind of an operation: it doesn't have a central bank to act as the government's marketer, issuer of banknotes, and lender of last resort; it doesn't have a sinking fund to manage the level and price of debt; it hasn't issued charters to merchant's guilds or joint-stock companies that could combine the small capital of individuals and thus more easily afford to buy bonds; and it doesn't have enough literate people who've studied accounting to staff a royal bureaucracy large enough to coordinate and keep records of all of this economic activity.

#asoiaf meta#asoiaf#medieval banking#medieval economics#medieval finance#early modern finance#westerosi economic development#early modern economy#central banking#westerosi economic policy#early modern state building

27 notes

·

View notes

Note

Give me a hot take any hot take, can be lukewarm or on literal fire I trust your judgment

Been overthinking this for days so here we go, under the cut bc this got a lil rambly:

the IMF as an institution is a tool of global economic terrorism mostly utilized by the United States to destabilize countries that a) hold nationalized resources the us gov't wants access to, b) are engaging in a form of economic growth that threatens the Washington Model (see: what was done to Korea post WWII, for example), or c) that house or are sympathetic to forms of ""communism"" or ""religious extremism"" in whatever form most currently convenient.

everybody talks (and rightly so) about how the US gov't has, via the CIA, orchestrated assassinations, overthrown governments, and caused general public chaos both at home and abroad, but like. the IMF bills itself as an independent organization aimed at helping struggling nations, except that the largest lender/donor country is the United States, and they have almost explicitly operated as a safeguard of US economic interests abroad.

they have essentially one set of protocols, which they throw like a net over everyone who comes to them for help: cut inflation by raising interest rates and cutting government funding for social safety nets. which is basically just the standing order for US monetary policy but on steroids. they put the client country on this plan whether inflation is the actual problem or not--and frequently, it's not--and then watch as the nation either starves its citizenry out trying to keep up with these demands, or defaults.

there's a book I read for undergrad called globalization and its discontents: revisited by joseph stiglitz which covers a bunch of things, but one of them is the role the IMF has played in curbing and crushing a lot of developing economic models over the decades in pursuit/defense of US economic interests, which I highly recommend if you'd like another reason to be incandescent with rage lmfao.

#av speaks#ask#answered#azure-arsonist#I have no idea whether this was what you wanted BUT#this topic is bubbling in the back of my mind constantly so here we are

4 notes

·

View notes