#I just hope and pray they go after asian americans or people mixed with asian

Text

been trying to cope with the fact that nct hollywood isn’t a joke, nothing’s working 🙃

#did they really think that was a good idea???#I just hope and pray they go after asian americans or people mixed with asian#cause we don’t need a group of tanners 💀

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Being an Agender, 1st-Gen Indian-American

I’m a first-generation immigrant, with both my parents being Indian immigrants. My mom immigrated to Canada before she came to America (when she was in her late twenties), and is a Canadian citizen. She was born and raised in Ahmedabad, a city in Gujarat. My dad moved to India when he was in his early twenties. He moved from Ahmedabad to Mumbai in his fifth standard, and moved from a Gujarati-medium school to an English-medium one.

My dad is more fluent in English than my mom, though they both are fluent and speak mostly without an accent. I speak Gujarati more-or-less fluently, since that’s what we spoke at home, but I can barely even write my name. I’m Hindu, as is my family, and a strict vegetarian. I’m agender, but I use she/her and they/them pronouns.

Beauty Standards

One of the biggest issues in the Indian-American community is the issue of body hair. I’m AFAB, so I was expected to have smooth, hairless legs and arms. The reality was rather different. Since the age of ten, I had more body hair than the boys in my class. I was mocked and called by the name of a TV animal character, whose name was a mispronunciation of my own. No one ever did anything about it. I was eight. My mother, though she meant well, pushed me into waxing and threading and other forms of hair removal since the day I turned eleven. Even now, as a fully-grown adult with my own apartment and my own life, I can’t bring myself to wear shorts or capris without having spent hours making sure my legs are smooth. Body hair is a huge issue that needs to be addressed more, and not just as a few wisps of blonde hair in the armpit region.

Food

It’s complicated. Growing up, we had thaalis (with roti, rice, sweet dal, and shaak [which is a mix of vegetables and spices]) for dinner almost every night. When we didn’t, it was supplemented with foods like pasta, veggie burgers, and khichdi. We made different types of khichdi each time, based off of different familial recipes that were all named after the family member who introduced them. My mom had to make milder food for my sister, and while my sister loves spicy foods now, I’m still not a big fan. A side effect of growing up in a non-white, vegetarian family is that no one in my family has any idea of what white non-vegetarians eat. Like, at all. It’s kind of funny, to be honest.

Holidays/Religion

My mom is a Vaishnav, and my dad is a Brahmin, so the way they both worship is very different. My dad’s family places a huge emphasis on chanting and prayer, as well as meditation. They mostly pray to capital-G G-d, as the metaphysical embodiment of Grace. My mom’s family, however, places emphasis on– I don’t want to say “idol worship" because of the negative connotations that has– but they worship to murtis, statues that represent our gods. My mom’s favored god to pray to is Krishna, and we have murtis in our home that she performs sevato every day.

We celebrate Janmashtmi, Holi, Diwali, Ganesha Puja, Lakshmi Puja– too many to count, really. We don’t always go all-out, especially on most of the smaller celebrations, but we do try and attend the temple lectures on those days, or host our own. We also celebrate Christmas and Easter secularly. I didn’t even know Christmas was a Christian holiday until I was in elementary school, and Easter until I was in high school.

Micro-Aggressions

Whooo, boy. Where do I start?

When my sister was in first grade, she had a friend. I’ll call her Mary. Mary, upon learning that my sister was not, in fact, Christian, brought an entire Bible to school and forced my sister to read it during recess, saying that otherwise, she wouldn’t be her friend anymore. Mary kept telling my sister that she would go to hell if she didn’t repent, and that our entire family was a group of “ugly sinners.” When my sister came to me for advice, I told her that Mary wasn’t her friend, that Mary wasn’t being nice, and that my sister wasn’t going to go to hell, and that we don’t even believe in hell. When my sister finally stood up to Mary and told her that she wasn’t going to listen to her anymore, Mary got angry and dumped a mini-carton of chocolate milk on her and told her that “now she looks like what she is– a dirty [the Roma slur term].” Not only was that inaccurate, it was extremely racist, and Mary was only reprimanded for the milk-spilling, not the racist remark that came with it.

On top of that, since I have long hair, I’m always getting asked if so-and-so can touch it, or what I do to get it so long, or why I allow myself to be “shaped by such backwards ideals of women.” My name is never pronounced correctly, and I’ve been asked to give people my “American name” to be called by instead of my actual name. I’ve been called a terrorist, asked why I wasn’t wearing a hijab (by white people btw), and mocked for my food. I’ve been told that I wasn’t “really Indian” because I didn’t have a dot on my forehead. I’ve been told I wasn’t “really Hindu” because I had milk on my plate, by a white boy whose mom was a leader of a local choir.

I grew up in a town where only 4-5% of the population was South Asian, and there were a total of five South Asians in my grade level. The school administration consistently and intentionally placed us in different classes, and I never made a friend that was South Asian until 7th grade. When I came to the school, I was placed in ESOL without even being tested, while also being in the Advanced Readers class. The school didn’t even care to look at my school records before placing me into ESOL based on the color of my skin.

Things I’d Like to See Less/More Of

I’d like to see less of the “nerd” stereotype, of the “weak, nonathletic” stereotype. I’d like to see less of the “prude” stereotype, of the “I hate my culture/feel I don’t belong” stereotype. I’d like to see less of the “rebellion” stereotype, of the “my parents are so strict and I hate them” stereotype. I never want to see the “unwanted arranged marriage” trope. Ever.

I want to see bulky, tall Indian characters. I’d like to see Indian characters confident in their sexuality, whether that’s not having sex (for LEGITIMATE reasons like risk of STDs, general awkwardness before and after The Deed, and wanting to wait, not “oh my parents said so and also I’m sheltered and innocent”), or having a new sexual partner every night.

I want Indian characters (especially children/teens!!!) proud of their culture and their heritage and their religion, whether that’s Islam, Hinduism, Sikhism, or anything else. I want to see supportive Indian parents, I want to see more than chiding Indian grandmothers and strict Indian fathers. I want to see healthy arranged marriages, or healthy mixed-marriages. I want to see mixed Indian-POC couples, I want to see queer Indian couples.

I want to see body hair on female-presenting characters, I want to see more of India that isn’t “bustling market with the scent of spices in the air” and “poor slums rampant with disease” and “Taj Mahal”. I want to see casual mentions of prayer and Hinduism and Indian culture (a short “My mom’s at the temple, she can’t come pick us up” or a “what is it? i’m in the middle of a holi fight! eep! ugh, gulaab in my mouth” over a phone call, or a “she won’t answer until 12– she’s in her Bharatnatyam class/Gurukul class/doing seva/at the temple” would suffice). I want to see more Indian languages represented than just Hindi. There’s Tamil, Gujarati, Marathi, Nepali, and Kashmiri, just off the top of my head. The language your character speaks depends on the place they come from in India, and they might not even speak Hindi! (I don’t!)

I hate that Indian culture is reduced to “oppressive, strict, and prudish” when it's so much more than that. I hate that Indians are stereotyped to the point where it is a norm, and the companies reinforcing these stereotypes don’t take responsibility for their actions and don’t change. I hate the appropriation of Indian culture (like yoga, pronounced “yogh”, not “yo-gaaa” fyi, the Om symbol, meditation, and Shri Ganapathidada) and how normalized it is in Western society.

This ended up a lot longer than I had expected, but I hope it helps! Good luck with your writing :)

Read more POC profiles here

Submit your own

#POC Profiles#submission#Indian#South Asian#agender#first generation#Canadian#beauty standards#food#holidays#Indian holidays#Vaishnav#Brahmin#Hindu#Microaggressions#racism#sexism#Culture#Indian culture#representation#Indian representation#South Asian representation#Indian stereotypes#stereotypes

1K notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

JAMILA WOODS - BALDWIN

[8.20]

Her legacy is secure on our sidebar, but she clearly has more lofty ambitions...

Alfred Soto: Absorbing James Baldwin's incantatory power into musical history that encompasses soul horns and a unforced communitarian spirit, Jamila Woods remains skeptical of his legacy anyway. She understands how an influence is a menace too.

[8]

Nellie Gayle: How do you live a legacy, honor a history, that's equally heartbreaking and triumphant? Jamila Woods brings brightness and joy to her reflections on African American history in the United States, without ignoring the trauma implicit in its story. "Your crown has been bought and paid for. All you have to do is put in on your head" the video quotes from Baldwin. Much like the author she named the track after, Woods will not gloss over the daily suffering and indignities of white supremacy in the US. But also like Baldwin, she's an optimist who derives happiness and hardwon joy from a history of resistance. So long as there is a vibrant culture and community whose stories deserve to be celebrated (not just told), Woods will literally sing its praises with melodies reminiscent of Bill Withers - upbeat, sunny, and heartfelt. Another Baldwin quote for Woods, one that deserves to be framed & hung up on bedroom walls in times like these: "To be a pessimist means that you have agreed that human life is an academic matter, so I'm forced to be an optimist. I'm forced to believe that we can survive whatever we must survive."

[9]

Nortey Dowuona: A warm, dreamlike roll of piano chords swirl with the wind as a loping bass limps alongside dribbling drums as warm bursts of horns drift past Jamila, who gently stirs the cauldron, which bubbles warmly as the kids gather around in cautious excitement.

[9]

Kylo Nocom: "BALDWIN" is a perfect explanation of how the idea of (argh!) optimistic and loving resistance can (often justifiably) feel like a pointless endeavour, especially when applied to the struggles of black Americans. Poetic descriptions of gentrification, police brutality, and non-black inaction are painfully outlined, betraying a central exhaustion that lies in Jamila's doubts of her friends' and icons' messages of hope. Jamila's croon also reads as tired, perhaps unintentionally, but with the help of some tasteful vocal accompaniment the sincerity beneath her uneasiness is allowed to flourish. Despite the underlying hesitance, "BALDWIN" is ultimately inspired by a real desire to see love as a means towards building community. As for Nico Segal, it seems he was just invited to aim at my weakness towards percussive horn blasts, punctuating the lines that seem to resonate the most powerfully: "we don't go out, can't wish us away."

[9]

Joshua Lu: Utterly sublime and warm, like the aural equivalent of a hazy summertime sunset, which is startling for a song with this subject matter. "BALDWIN" touches on the different ways racism manifests, bringing up not just images of black fathers dead on the streets and white women clutching their purses, but also referencing the "casual violence" in white speech and white silence. It's subtly damning, and Jamila sounds too weary to accept the solution she's been offered, to extend love to the people who will never reciprocate it. The song ends uncertainly, hanging on a cryptic line and an unsatisfying melody, as if daring the listener to provide their own resolution.

[8]

Joshua Copperman: "BALDWIN" struggles with its namesake's theory that "you must accept them with love" - 'them' referring to white people - "for these innocent people have no other hope." How is love even possible, even in Woods' definition of love, with the aggressions both macro (police brutality) and micro (purse-clutching) addressed in the lyrics? Obviously, there aren't easy answers, but Woods' educated guess on surviving is not just resilience, but community. That chorus starts with "all my friends" for a reason. It's not quite as anarchic as "You can tell your deity I'm alright/Wake up in the bed, call me Jesus Christ," but it's the same eventual conclusion. Instead of defying religion, Woods defies the expectation of being respectable. That's the interesting thing about this beat too, from Slot-A, mixing more traditional R&B instrumentation like Rhodes piano and canned synth pads with trap snares and horn stabs. He takes advantage of Woods' thin voice, not only contrasting it with those heavier textures but also giving it space to breathe. Another hook of this song - there are several - is "You don't know a thing about our story/you tell it wrong all the time," suggesting that if love alone won't overcome, telling your own tale will be more than sufficient.

[9]

Will Adams: So many (usually white) musicians handle the topic of racism as deftly as if it were a hot potato slathered in grease. Jamila Woods cuts to the core in a single verse, addressing police brutality, gentrification and purse-clutching casual racism. The arc of the song is balancing that anger with weariness of those who preach civility in the face of hate. If that all sounds a bit too down, Nico Segal's punctuation in the form of bright horn stabs are there to keep the message alive and resonant.

[7]

Jacob Sujin Kuppermann: Not the most transcendent piece on LEGACY! LEGACY! (see "BASQUIAT"), but a close competitor. The jazzy production sets the groove well, and the stabs of Nico Segal's horns and Gospel-adjacent choirs fill the space beautifully. But it's Jamila herself who takes "Baldwin" from something pleasant to something glorious. She bridges romance, protest, and memory like no one else can, melding them with her sweet, pointed voice into the album's best demonstration of its thesis.

[9]

Joshua Minsoo Kim: "BALDWIN" is a song that finds Jamila Woods detailing the outright, inescapable racism that occurs against Blacks every day. In referencing James Baldwin, she makes clear how such fear and hatred-fueled actions have persisted to the present day. But what makes this so fascinating a song is that Woods muddies the waters; she spends a bit of time wrestling with the positivity that Baldwin espoused throughout his lifetime, finding herself conflicted by the effectiveness of such praxis. In a way, listening to this feels like a legitimate Sermon on the Mount moment, where "lov[ing] your enemy and pray[ing] for those who persecute you" comes as a shocking command instead of a spoonfed Sunday School lesson. Miraculously, "BALDWIN" doesn't end up feeling knotty and tense, but overwhelmingly triumphant. You can sense it in the gospel choir and Nico Segal's horns, but it's Woods's own silk-smooth vocals and circuitous melodies that announce her impossible serenity. Has she found truth in such ostensible cognitive dissonance, or is she too elated to be bothered by this disagreement? That internal struggle finds no conclusion here, but Woods transcends it all by being an inspiration herself. She embodies something that Baldwin had written to his nephew in 1962--a specific instruction that feels ever necessary today: "You don't be afraid."

[7]

Iris Xie: With such a clear, gentle series of asks here, you would have to have an adherence to bigotry, or at least avoiding the discomfort of examining your own internalized anti-Black biases, in order to avoid considering what Woods is saying here. I think about this a lot as a queer Asian American, what my responsibility is to the project of helping not contribute and help demolish the project of anti-Blackness as enacted by white supremacist institutions and those who are complicit and facilitate them, especially when I see the amount of pain in both the news and what my friends experience. The line of "All my friends / Been readin' the books / readin' the books you ain't read" cuts deep for me especially, because I have an Bachelor's degree in Gender, Sexuality, and Women's Studies, which is an enormous amount of privilege in itself to receive and is due to countless activist histories that made that possible. It also made me think of the sheer amount of books about queer Black feminism that I genuinely feel I've barely scratched the surface of understanding, but am always in awe of the brilliance exuding forth. All of it is already written here for anyone to read, with new scholarship and articles and media produced all the time to help digest and made accessible for the rest of us. The loveliness of this song is that in its quiet neo-soul tempos, with the subtle snares, synths, and horns, results in a vibe she is secure in itself and asks the listener to move towards Woods. Black activists have put together the work and articulated these for decades, for any of us to read. The least we can do is listen and pay attention, as a complete bare minimum.

[7]

[Read, comment and vote on The Singles Jukebox]

2 notes

·

View notes

Quote

”So what are you?”

The question which plagued my childhood in suburban Kansas; the ponderance of which led me towards years of agonizing identity searching; the answer to which I still hesitate to deliver.

“So what are you?”

It is an innocent question; one I know I am not alone in hearing the echoes of. But what do I say? “I’m mixed” is the short answer, but it always leads to the question of “With what” so do I say “My mom is white and my dad is brown” but brown isn’t usually specific enough so do I say “my mom is white and my dad’s Pakistani” but that doesn’t flow right because white is a race and Pakistani is a nationality so do I say “my mom’s American and my dad’s Pakistani” but that isn’t true because my dad was born in Canada and he’s lived here his whole life and American sure as hell doesn’t mean white I mean my dad IS American so do I say “My mom’s a white American and my Dad’s Pakistani American” but that just sounds like I’m trying too hard so that’s out of the question and so do I just drop it and leave it at “none of your business” but that’s rude and it’s really such a simple question so what in the hell do I freaking say?

”So what are you?”

It’s a good question, really… why don’t you tell me? I am the alienation that I feel when my mom’s family talks about how dangerous those Muslim immigrants are over dinner and I am the strange sinking feeling in my stomach which occurs when my cousins tell me that whatever I’ve just done is haraam. I am the frustration which clouds me when people around me doubt that I am what the hell I say I am. I am the product of the millisecond long stares of confusion people give me when I tell them the pale as china blonde lady I’m with is my mother and the looks of disgust I get when I, the young, doll eyed light skinned girl, go out to dinner late at night with a big burly middle aged brown man, aka my father. I am the three and a half years it took me to decide what to call the pigmentation of my skin.

I am the sadness which clouds me when one of my Aunties asserts how lucky I am to be so fair skinned. I am the anger I feel each and every time I think about the people who called my full and plump Desi lips fat as a kid and now use copious amounts of lip liner to accentuate their tiny mouths on Snapchat. I am the hours of hoping and praying during and after shootings that it wasn’t a Muslim. I am the incredible lengths I go to, the precise and complex knowledge I feel I must have of my roots in order to truly claim my heritage. I am neither and I am both and I hate it.

“So what are you?”

I can’t stand here and tell you that it is all bad. That would be I lie, for I am also the cool, smooth feeling of the bronze crucifix which sits on one side of my bedroom wall and the sentiment of the words “Allah most merciful” written in beautiful Arabic script on the other. I am my large French hazel eyes and my thick and wavy South Asian hair, my favorite of my features.

I am the pride I feel as I trace my thumb over the intricate embroidery on one of my anarkalis and the anticipation I feel for Christmas as I help line my grandmother’s fireplace with garland. I am the rhythmic clanking of my bangles as I dance to bhangra music at a cousin’s wedding and the clicking of tongues by a sizzling grill as my grandpa flips our burgers during a Sunday night barbeque. I am the flavorful and savory taste of pulao my father makes and the creamy texture of mashed potatoes on Thanksgiving. I am the Maybelline mascara I coat my eyelashes with and the kajal I used to line the edges of my eyes. I am the flavorant meeting of two cultures melting in an incredible country in which such a thing is even possible.

So what are you?”

God, but what am I thinking? I’m Jackie. I am the impending messiness that is my bedroom. I am my inability to fall the hell asleep before eleven o’clock at night. I am my love for all things fashion and glamour. I am my obnoxiously large collection of makeup. I am my hideous shedding of tears each and every time Spock dies in the Wrath of Khan.

I am my intense love for horror movies and my struggle to move in the dark for two days after watching them. I am my passion for music and Michael J. Fox and Kanye West and my unrequited love for Zayn Malik. I am my collection of records and of 32 scarves which I never wear, my brown riding boots, my belting of Christmas carols in the middle of July, my irrational hatred of algebra, my inability to sleep without my phone being on its charger, the Toll House cookie dough I eat straight from the bag and the four Beatles posters I have hanging in my room.

I am the scent of Aussie conditioner and my clumsy, spacy nature; my obsession with the Kennedys, my adamant love for Diet Dr Pepper, losing myself in my daydreams, my extreme extroversion and procrastination of literally everything, my weakness for Reese’s peanut butter cups, my A to Z knowledge about Mick Jagger, my ever changing mind. I am my dreams and I am my fears and and I am my tenacity and I am my mistakes and my courage and my insecurities and my abilities and my hope … I am so much and yet I am so little. I am me. I am unapologetically and beautifully me.

“So what are you?”

I am Jacqueline Renee and I am what I am and no answer that I give you to this question will make what I am any different.

880 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hach Guli Ba Char Mast (No Rose Is Without Thorns)

Hach Guli Ba Char Mast

(No Rose Is Without Thorns)

2008:

This has been the hardest job of my life. I asked myself as I got on the plane whether going back to Afghanistan is the best idea. But I tell myself I am a doctor and I am an Afghan. I must help it to recover.

The organization I have come with this time is an Afghan organization run by Afghans. All of their support comes from private, international donations. It has cost me very much to come here. More than can ever be repaid. It is much better than the American organization I came with, on my first trip two years ago. The hospital was old. The conditions were horrible. The halls did not smell of antiseptic and sterile cleaning materials. They smelled of sixty years of urine and sewage. The scrub rooms were merely bathrooms. The electricity constantly cut out. It had only a drip for running water, and all of the sinks were backed up. The people in Washington had promised the hospital money. The Laura Bush Women’s Memorial Hospital. What a disgrace.

Guli Women’s Hospital is in the eastern province. It is a nowhere oasis in the middle of nowhere. It is in the middle of a large desert gully between two mountain ranges. The nearest village is 100 kilometers away in the mountains. Most of the patients come from many more kilometers away. It is many days journey for most. All of the hospital staff were lined up to shake our hands as our motorcade pulled into the large drive in front of the hospital. My wife, Naima, and I graciously accepted their greetings. I could tell this was a much cleaner and more professional hospital. It smells mostly of musk, figs, and jasmine. I have learned this is a good sign. However, the staff still has much to learn about modern medical procedures. Or maybe they don’t.

Shelab and Ali came from three days journey. They came two and a half month after we arrived at Guli. It was obvious that she was heavy laden with child. It is the same with most of the patients in the hospital. Ali was frightened. He stood up and leaned his rifle against the wall. He was like all of the other squatting men lining the halls of the little hospital. I told him that God willing all will go well. His sharp blue, green eyes pierced me, pleading with me not to let her or the baby die. I understood. I have seen the look many times now.

Many Mullahs still refuse to give up their position of power. Many husbands have died for taking their sick wives to the hospitals rather than to the Mullahs, to have the evil spirits beat or choked out of them. I have seen many women during my time in Afghanistan with bruises on their arms, legs, and backs from the whips of the Mullahs. And I have seen many dark finger-shaped bruises on the throats of women from the hands of the Mullahs. Shelab had surprisingly no marks for as sick as she was.

Shelab’s crimson robes and turquoise head scarf reminded me of a doll I bought for my daughter at the Afghan market in L.A. She was young. Her skin was old but still young and smooth for an Afghan woman of her region. Her beautiful round face and delicate almond-shaped Asian eyes made her look even younger. No one knows their exact age in Afghanistan, but everyone is older, thousands of years older.

Ali told me that the last baby died at birth and that ever since she has not stopped leaking urine. It is a common problem here. For many women, the inside of their legs become completely raw from the mix of chafing and urine. They bleed, and many times they get a serious infection. It is a simple procedure in the United States. But, this is Afghanistan, and nothing is simple.

I tell Shaleb that we try to fix all of this after the baby comes, and God willing all will go well. I ask her if she is alright if she is scared. She tells me, no, she is not nervous. She tells me if the baby lives it lives, if the baby dies it dies. It is the story of the Afghan woman.

Shaleb had been having contractions on and off for five days. It was good that they came to the hospital. Her lack of vitamins and malnutrition had caused her uterus to contract and tighten. It would have surely caused her to rupture, killing her and the baby. That is if the Mullahs had not gotten to her first.

I explained to her that the baby would not come out of her vagina. It would have to come out of her belly. I traced a C with my finger along the lower part of her abdomen. She covered her face with her scarf. She tells me if the baby lives it lives, if the baby dies it dies.

I tell the nurse to get the anesthesiologist. She says she told him already. I tell her that she has not told him yet. No one in Afghanistan takes responsibility.

The delivery room was warm. The two nurses are young, just out of their teens. The table is wood and steel, but it does have stirrups.

The incision only took a light amount of force. There was little blood. The baby was blue. I have to tell the nurse again that she must wrap the babies immediately. My wife steps in to help. The nurses do not like her. She is a doctor and she is strong. She goes over the procedures with them again. They do not like her.

My supplies are limited. My Laryngoscope was too big to fit down the babies throat. I have no smaller one. My finger was too big to fit in the babies throat. I could only suction and hope for the best. I give to God.

We have no oxygen masks small enough for babies. I have the nurse hold a hose up to the baby’s face and hope for the best. I give to God.

A nurse comes in followed by Ali. She tells me that six Mullahs from Ahmed, Ali and Shaleb’s village, are outside. She says they abused people as they came into the hospital. They are looking for Shelab and Ali. I tell her to send some men from the hall out to talk with them.

I tell Ali not to worry. I tell him that I am now going to fix the problem causing Shaleb’s urine drip. He thanks me and gives praise to God. I make four stitches in the small tear in her bladder. It went much better than I had expected. It was a clean tear. I give praise to God.

The baby had to be fed with goats milk poured from a small spoon. I tell Ali to stay in the recovery room with Shaleb. I explain that he must help. I did not want them to leave. I explain that the baby would not be able to travel for many days and that Shaleb’s recovery must be observed.

The Mullahs did not want to leave. The nurse tells me that the Mullahs call for my death. They want all the doctors to be killed. They say doctors use evil magic. I am frightened but not from them. I have become used to fear in Afghanistan. It is hard to know when people may be swayed. There is a whole generation all but lost. A whole generation that knows nothing beyond the Taliban, nothing beyond the Mullahs, nothing beyond war, nothing hopelessness. It is hard, especially in Afghanistan, for people to break the rules of their religion and their minds. But sometimes love overcomes love for wives, love for children, love for family. Sometimes it is love.

Two days later, I tell Ali and Shaleb their baby has died. It was this morning. I tell them perhaps next time it will be better. God willing, it will be better. Shaleb tells me if the baby lives it lives, if she dies she dies. She does not cry. They do not cry anymore in Afghanistan. I tell her that she must stay four more days. Ali takes his rifle and leaves the room.

I step out onto the porch of the hospital this evening. The sun is beginning to set. There are six men in black robes with black turbans standing together along the low wall around the hospital courtyard. They are waiting. That is what they do. They know I come from America. They know it is only a matter of time before I leave. They will wait. They know that is all they have to do, be patient enough and the American will leave. But I am Afghan too. The winds blow a dust devil on the dry plane behind them. The Mullah on the far left points at me. He makes a slashing motion across his throat. I watch the dust devil fade away. I finish watching the sunset. They watch me.

I fear for my wife. They will not kill her. They will rape her first. They will beat the evil spirits out of her. They will tell her she is going to hell. Then they will dismember her. She is not a mere criminal. She is an infidel, an enemy of Islam. She wears pants. She wears make-up. She does not wear a headscarf or a burkah. She is educated. She prays to God five times a day.

My wife asks me as I come to bed if I am afraid if I think they will kill us. She is beautiful. She is Afghan. We met in Kabul in 1968, before the Russians, before the civil war, before the Taliban, before the darkness. I had just begun my studies at the University. She was the sister of my friend, Zhair. He was my lab partner in Anatomy class. She was 16. She was so interested in our studies. She was educated. They were one of the richest families in Kabul. She said that she wanted to become a doctor as well. Their father beat her. He told her that she was to marry Sahib, an officer in the military. But we fell in love. She came to me one day when I was in the fig orchards outside of the city. She came to me with money and jewelry stolen from her father. She told me that she wanted to run away with me. I knew once I saw the jewelry we would have to run. There would be no giving them back. We ran away together. We went to America. I refueled airplanes at LAX, and she washed clothes. We both earned doctorates in Obstetrics in 1980 from UCLA. I brush her dark, wavy hair back behind her ear. I tell her that she is strong, that she should not worry.

Shaleb and Ali wait quietly in the recovery room this morning. I ask Ali how he is. He bows. The blue fabric from his turban slightly unravels. Shaleb looks worried. She covers her mouth with her scarf. I tell her that it is time to see how her operation has gone. I insert the calipers into her vagina and removes the lengths of gauze. I inspect the gauze for any of the dye the nurse gave her to drink the night before. No dye. I smile. I tell her that it has gone well. She covers her mouth again with her scarf. I can see the smile in her eyes. I check the stitches on her stomach. I tell her that the stitches are not healing as quickly as I had expected and that I would like it if they stayed several more days.

Ali tells me that they can not go home. The Mullahs have called for them to be killed. Word has come that Shaleb’s family agrees with the Mullahs. Their house has been burned and their goats and donkeys have been killed. They have nowhere to go. I tell them that we will find them a place to stay.

I go to the porch. The Mullahs still stand along the wall. Zammel, the head nurse comes to my side. She tells me that some of the men want to take their wives. They are afraid of the Mullahs. They have threatened to have the hospital burned. The men are afraid that people from the villages will come to support them. She tells me that it is not good, that she has not seen it like this. I know it is because I have come from America because my wife is strong. They do not like this. They are afraid.

I go to the men in the halls. I ask them, do they love their wives, lives, their families. I ask them, do they love their children. I ask them, do they love their own lives. They are afraid. They say nothing. They do not stand up from their squatted positions along the walls. It is hard for them to not stand. They are Afghans. But they are also the words of the Mullahs that have filled them since birth.

I think maybe I might call the Americans. I think maybe they will send troops. But I know that will only make things worse. That will only strengthen the Mullah's position. I think maybe Naima and I will leave. But I know more women will die, and more babies will die. The staff still has much to learn. If we leave people will be even more afraid to come to the hospital.

I can not sleep. It is hot this night. My turning rouses Naima. She tells me she also can not sleep. I tell her I do not know what to do. She apologizes. She tells me she is part of the problem. I tell her not to say that. I tell her she is part of the answer. She is so beautiful, still so young. I can see every curve of her face in the moon’s light. Her eyes are Jupiter. Her breath smells of almonds. She smiles. Her breasts are as the mounds of Kabul. Her stomach is a desert plane. Her lips feel smooth and beautiful as the California sunset. Her body moves like fields of wheat in the breeze, like waves of the sea. I’m drowning in her current. I gasp for air. I am pulled under.

In my dream, I hear a stirring from our garage. It is 4a.m. I get up to see what it is. Naima does not wake, and I do not wake her. I look out through the window to the garage. The light is on and Naima’s Lexus is pulling in next to my Mercedes. It is Fatima. I ask her why she took her mothers car, where she had been, how long she had been out, who she had been with. I tell her she is in much trouble. All she can do is cry. My daughter does not cry. I know it is bad. I pour her a glass of orange juice. It was a boy. I tell her she is sixteen, that she is too young for boys, that there are so many other things to experience in her life. She wanted to run away with him. She wanted to go to Europe. She found him with another girl. He told her she was crazy. I tell her that people will break her heart sometimes, but that love will always fix it, and that I loved her. I carry her to her bed. I sing her to sleep with the Afghan children’s songs I use to sing to her as a little girl.

I step on to the hospital porch. The sun begins to rise. The Mullahs begin to stir in their camp outside the gate. There are more now, twenty, twenty-four maybe. Ali comes to my side. He tells me that they came in from several of the villages the night before. I ask him what he thinks. He tells me there is no stopping them. They are only waiting for enough supporters from the villages. Then they will burn the hospital. He is young, but he knows. He tells me that he was Taliban until the Americans came. He ran away to the eastern provinces in hopes that no one would recognize him as Taliban. He tells me that when he came he had only four donkeys and a rifle. He trades one donkey for a house, and one donkey for Shaleb. The man she was to be married to had only a goat, and because she was a widow that was a good price. He tells me that the moment he saw her by the well he knew he loves her. I tell him I think I may go speak with the Mullahs. He assures me that it is not a good idea. I tell him that we cannot just wait for them to come. He tells me that he will go with me, and God willing we will live.

The courtyard is no different from the dry rocky plane outside the wall. The hospital is four hundred meters from the wall in all directions. The wall is only a little taller than waist high. The Mullahs line up as they see us coming across the courtyard. The wind blows my white coat open. I greet them. They say nothing. Their dark eyes burn my skin. I tell them that I have come to help, that the patients are well, and that they are given the opportunity to pray five times a day. The Mullah that pointed at me on that day steps out. He tells me that I am dirty, that I practice evil, that I am teaching people to go against Islam, that my wife is a whore of the lowest sort. I try to step forward, but Ali tugs at my coat signaling me that it is not a good idea. I bid them a good day. Ali and I turn and leave, keeping our eyes over our shoulders. The Mullah makes a last single statement to our backs. He says Afghans are patient, and I will have to leave sometime.

Ali and I step onto the porch. I hear a loud rumble from behind me. We turn to see a convoy of American vehicles. My stomach begins to tighten. The trucks turn toward the hospital. My knees begin to shake slightly. It is not good for them to be here. All of the men in the Mullah’s camp stand to their feet. The convoy breaks. Eight of the vehicles take up position at each of the corners of the four walls surrounding the hospital, two at each corner. Two blocks the gate, and one comes up the drive to the hospital. A US Army captain steps out of the vehicle with his Afghan interpreter. He is fully dressed in body armor. He is wearing dark Oakley sunglasses. He tells me through the interpreter that word has come to them, that there is trouble. I assure him through the interpreter that there is no trouble, that he is mistaken. He asks me about the men outside the wall. I explain that they are not immediate family and that they are not allowed to stay in the hospital. He asks why they don’t camp in the courtyard. I smile and tell him through the interpreter that they are Afghans. The young man returns to his vehicle. The interpreter stays with me and Ali. The officer makes a call on his radio. He shakes his head. He tells me through the interpreter that they have been told to stay here for several days. I assure him again that all is well. He tells me that he is under orders. I speak to him in English. I tell him that they must go. He is surprised. He tells me that they cannot go. I tell him that if they do not go it is going to be much worse. He smiles. He tells me that he has been to Iraq twice, that it is not the first time that he has seen trouble. He tells me that they are going to detain all of the men outside of the wall. I beg him to please not do this thing. He tells me he is under orders, and that if I have a problem with the men outside of the gate that I had better leave within the next few days.

I see over the captain's shoulder that the other vehicles have surrounded the Mullah's camp and have begun arresting them. I run across the courtyard. I try to stop them. I beg them to please not do this. They ignore my pleas. They tell me they are under orders. I see the Mullah who pointed at me. He is stone. He tells me that the devils on my side have blessed me with a small amount of time, but that my magic will burn in time, and God willing so will I with it. One of the soldiers kicks the Mullah in the back of the knees because he refuses to kneel. The Mullah sinks to his knees. He is unable to catch himself because his fingers interlocked behind his head and being squeezed by the soldier. He falls on his face in the dirt. The Mullahs and their supporters are searched and put on the back of trucks. The soldiers leave taking the Mullahs and all of their supporters.

The captain and twelve soldiers stay. The captain explains that he and his men will stay for a few days. He tells me he knows it is not over, but they will probably be pulled back before it starts. I do not understand. He goes to his men across the courtyard.

Ali assures me that this is not a good thing that has happened. He tells me that this will be used as a sign, as proof that I have the devil on my side. The Americans will only hold them a few days. Then they will be released back to their Mosque. He explains that the Americans do not understand Afghans, the Taliban, the Mullahs, or Islam. He tells me that they will be back, but the next time they will have many more with them, hundreds, maybe thousands.

I go to my wife. She is checking over one of the newly born babies. I tell her that I must speak with her immediately. She can see in my eyes that it cannot wait. We go to our room. It smells of rose and incense. She has blood on her apron, and her mask still covers her mouth. I tell her that something bad has happened, that American Soldiers have taken the Mullahs, that it is only a matter of time before we will be killed and the hospital burned. I tell her that she must leave within the next few days. She assures me that she will not leave without me. I know that she will not.

I go to the American captain. I ask him if he knows what he has done if he knows that he has killed me, that he has killed all of the patients in this hospital, that the hospital will be burned. He assures me that he does know, that he has seen it before, but that he is also under orders. He explains to me that politicians are running the war now and that his hands are tied. I ask him if there is any way he can get more troops because he is going to need them. He tells me that they won’t be needed, that new orders have come down, that all of the patients are being moved in three days by airlift, and that the hospital is being closed. I tell him that it is crazy, that there are over two hundred fifty sick and pregnant women in the hospital. He assures me that he understands. I ask him where they are being transferred. He tells me the Laura Bush Women’s Memorial Hospital.

I go to Ali. The moon is full. He is sitting on the porch re-wrapping his blue turban. His rifle sits on his lap. I explain to him that the hospital is being closed and that all of the patients and their families are being transferred to Kabul. He shakes his head. He tells me he cannot go to Kabul. He will be killed or arrested. He asks me to care for Shaleb. I tell him that Shaleb is probably well enough to stay with him. He tells me no. He tell me that she must go with me. I tell him I will care for as my own daughter. I tell him there is a fig orchard outside of Kabul. He tells me it is no longer there, but that he knows it. I tell him if he is still living, to come there at night in two months.

A crew of soldiers came this morning to build a tactical airfield on the dry plane. They are fast. It is finished by four o’clock. We will leave the day after tomorrow. A quarter of the patients have decided to leave. Some of them were well enough to leave. Some of them were not well.

0 notes

Text

If you are smart, then you’ll know that some journalists are extremely bad at their jobs. I was going to say that the media is whack, but it really isn’t and I’m not going to diss the platform I am able to write this on.

Before I throw around facts and examples, I am going to write about my truth and why I love the media and then my beliefs on the simple thing that is representation. As, once the facts and examples come in to play, they will fully support the truth.

Love and Truth: Mine

I think back on my childhood and I realise the views I hold to this day, have always been with me. I honestly do not know how this has happened or what impacted me to have these views. All I done was watch a lot of TV and read fair few books.

I attended a mixed primary school, it was a Church of England school, and we truly treated everyone as equal. From what I remember there was no racism on the schools part. We were children so we never saw each other as what adults with judgement would see.

Being a white person, when I think back on how things are I don’t think much difference of me and my friends. I have foreign friends and friends of colour, but it is hard for me to understand if I blend us together because of the privilege that comes with my ethnicity. But the fact that I have these thoughts is a safety net for me. It helps me realise where I stand, and allows me to always be cautious. So I do not succumb to the ignorance. I care for everyone like I care for myself. If they are not allowed to do something that I am, younger me would blindly defend them not knowing the real issue, whereas, adult me? She is woke and ready to set you ignorant bigots in your place.

My friend and I are planning to go to America sometime soon and she jokes that she hopes she can get through customs. At first it didn’t click, then I realised, she is mixed-race and UK customs is bad enough as it is, imagine what American customs are like especially when a bigot runs the country. Trump truly does put the C(o)unt in Country.

OK, this is already pretty lengthy and I am nowhere near done. Please leave me your thoughts on this, as I am after all, a white person speaking up on something I can never fully understand, so when I overstep I would like to be shoved back into my place..

Love and Truth: Media

The reason I love the media so much is because you can access it from anywhere and get your little fix of information. Currently we are in a media divide and it is hard to find any reliable sources. You think you have found one and then this obscene article promoting malicious views pops up. #cancelled.

The media used to be a place you could go to find out genuine facts and information but now all it seems to be is made up articles for clicks and reads. When did it all become so childish?

I’m going to skip to the more important factors now.

I saw the sentence “#CrazyRichAsians is a reminder that representation is important” and although I am yet to see it, I completely agree on that front. (I will be referring back to this at some point.)

Currently the media I am seeing is people fighting for things not to be whitewashed, and all though there has been a lot of accurate casting done and people are happy, there is a behind the scenes; how much did they fight for the truthful representation that they needed?

Examples and Facts: Media

Tim Burton was an artist I once admired, but his views on representation saying that POC weren’t a demand to be had cast in his projects, well that’s because he’s in his own little bubble of privilege and only thought about his norm. No one asked for us whites to come and take over everything. We have never been the only ones to interact with one another. Movies are supposed to represent life right? So you’re telling me you have never once interacted with a person of colour? OK, lets think about this: I am white. I live my life from a white perspective. If I was played in a movie you can cast me as any ethnicity. This is because there is no experience I go through that someone else hasn’t also experienced. A POC lives their life as one. PERIOD. You cannot taint that by making a white person play that, because that instantly gets played down and washed out.

We cannot portray lives where we cannot truly empathise with their experiences.

I am obsessed with art, books, films, paintings/drawings, etc. The lot of it makes me over the moon with joy. I would love to write a book. Then I saw that sentence: “Crazy Rich Asians is a reminder that representation is important“. It got me thinking about my book, I personally didn’t have anything in mind about what the characters I wrote about looked like, but then I remembered something: any book I have read, unless stated otherwise, my mind has subconsciously whitewashed it. That is an accident on my part as that was the originality of my minds programming. Once aware I would focus on the words blocking out any false imagery. But, this is a minor part.

Jenny Han has had her book, ‘To All The Boy I’ve Loved Before’, turned into a Netflix original. Upon watching the film, because of its strong representation with Lana Condor’s portrayal of the movies lead character, Lara-Jean Covey. The tea here is that Jenny took the book to numerous Casting Directors and they all wanted to whitewash Covey even though her ethnicity was a crucial part of the story. Does the cover suggest otherwise?

Thankfully, Jenny found some professionals willing to develop her work exactly as she had written it, thus began Lara-Jean’s journey with Netflix. Thank you to those of pure heart who saw the greatest potential was to keep the character as her true self.

This slideshow requires JavaScript.

Remember that film briefly mentioned ^? #CrazyRichAsians? Despite it’s name, people also tried to diminish its reality and tarnish it with white people. I know, its SHOCKING. Do they have brains? I know my brain doesn’t exactly work properly, but I’m glad it isn’t that broken. The images in the slideshow are taken from Emma Stefansky‘s article on Vanity Fair. I am currently tearing up at the powerful statement in the last slide: ‘What makes these people think that all we want to do is see the same white actors or actresses on screen?’.

That statement really caused me to breakdown and just think. I hope it had the same affect on you.

Sincerity to all of You

There are so many powerful, and influential artists I admire and look up to. If you’re a person of colour in any industry related to the media, you are a step in the right direction to putting bigots in their rightful place. It all starts with people noticing what’s wrong and standing against it to make it right; even if it means not getting paid. As long as you are not taking someone else’s rightful place, then its worth it. We have to speak up for those who need us to, but remember not to speak for them or over them.

This has been a very long post and I am sorry for that. I just wanted to write about this on my blog. I am still, quite literally shook, from reading about Kevin Kwan’s experience. As someone who one day hopes to be in the film industry, I am stunned that there are shameful people like this still thriving in the industry. I am hopeful and uplifted by this change, that they won’t be for much longer. I pray that once the new generation are grown that there are very little bigots in the industry. One can only hope.

I thank and love you if you stayed with me through all 1392 words. So much love xo

It's 2018 and this is still happening..?! If you are smart, then you'll know that some journalists are extremely bad at their jobs. I was going to say that the media is whack, but it really isn't and I'm not going to diss the platform I am able to write this on.

0 notes

Text

DWAYNE MARTINE | Naʹnízhoozhi: A Report from the Bordertown of the Mind

I left Naʹnízhoozhi (Gallup, New Mexico), my hometown, eight months after I graduated from high school. The train tracks, the fields of scattered broken glass, the summer ditches filled with sunflowers and thistles, and all the people there.

I moved to Albuquerque for school at the University of New Mexico. Like 6 a.m. light in my eyes, the next two years were all reading, studying and part time work. I didn’t have close friends, but was visited constantly by my lesbian friend from high school, Mia and every other weekend by my family.

I was twenty the first time I got drunk, which for growing up in Gallup was considerably late. There was me, three lesbians (including Mia), and one woman of questionable sexuality in the Howard Johnson’s off of I-25. I had 12 shots of tequila. The next day I went to class at 9:30 a.m. and took judicious notes, perfectly sober.

Two years later, May of 1995, I received a big envelope with the word “congratulations” on the back flap. It was just a week earlier I had been accepted as a transfer student to Cornell University. This envelope was my transfer acceptance into Stanford University. I was un-phased and immediately thought of months of blowing snow, as I mailed the acceptance postcard back to Stanford admissions.

Four months later, September of 1995, my mother prayed over me in Jicarilla Apache, as she, crying, left me and my few belongings in my dorm room. Save for a one-month high school writing program, I hadn’t lived away from Gallup for any significant time before. And even though I was poor, brown, Native, and backward, I felt proud, I felt I belonged.

In my first English class, “17th Century Lyric Poetry,” I was the only person of color. This one girl made a joke in French to which the rest of the class chuckled, as I sat there completely unaware. Then a few moments later, this other girl was asked to read a poem aloud. Even though on the page it was written in English, she started reciting it in Latin, which the rest of the class followed perfectly. I felt like I was back at Jefferson Elementary in Gallup, when these white kids were calling this poor girl from Smith Lake dirty and stupid. I had sat there, hoping they wouldn’t look at me next.

At this time I had many white and Asian friends in my dorm. I felt like I didn’t need to make Native friends, because my few interactions with the Natives on campus weren’t very impressive. I felt like the theme song for the Native program should’ve been 70’s Cher in a black wig with lots of turquoise singing “Half-breed.”

Growing up in Gallup, most of the children of interracial parentage didn’t appreciate us “fullbloods” and mostly hung out with the white kids. They were usually the children of Navajo women who married “out,” or as everyone said in town, married “up,” which generally socio-economically was the case.

Then there were the Navajo orphans adopted by non-Navajos. Many changed their last names because they sounded too Navajo. From Blackgoat to Black, from Manychildren to Mitchell. And then there were those special cases.

One girl denied having a Native parent. Being one of the popular, wealthy, “dumb” girls in school I never suspected she was Navajo. It wasn’t until years after high school that I met her parents and realized she wasn’t Hispanic like she told us. Her father was Navajo. I never saw her hang out with any Navajos. Even though we had the same classes for four years, I think she talked to me once. My views on racially mixed people have been colored by my experiences in Gallup.

So I didn’t have any Native friends my first quarter at Stanford and I thought I was just a regular student, making friends with people in my dorm. Those few white and Asian friends I had made me feel welcome. So within the pseudo-liberal safety of Stanford and with my new friends support, I called my family, my parents and four primary siblings, chatted briefly with them before I told them I was gay. I was 20 years old.

I had waited until I was away from home and had a place to go to if my family rejected me. I waited until I felt safe on my own to come out because I had heard the stories.

I had a Hopi friend who told his family he was gay and they threw him out. He was 17 at the time. I had another friend whose father beat her when she told him she was a lesbian. I had another friend who tried to commit suicide when her mother rejected her when she came out. There are so many stories. They gather like reeds in a stream, damming any progress until the water bursts forth and flows, like truth. My Native people have been the only ones to make me feel most ashamed of being different.

In Gallup, I have many Navajo “queen” friends, who haven’t officially come out to white gay standards. They’re flamboyant, perverse and unrepentant at the bars and with each other. At home, they’re the perfect sons to overbearing mothers or grandmothers. I don’t know if they’re lonely but sometimes when they drink and think no one is looking, they cry to themselves.

They don’t sleep with each other, other “girlfriends,” but rather have sex with the other Navajos in Gallup who are either closeted and married or looking for an easy, equal “trade.” My one friend who was raised “traditional” as she says, informed us one night that this situation is how it had always been, even before the onslaught of the Europeans. Her grandmother told her it was like this way back when and nobody objected or beat them for it.

They were called Nádleehi, Navajo for “one who changes.” It’s the alternative gender for Navajo persons who otherwise present as male but perform the Navajo women’s historical gender role, including weaving, household work, land ownership and child rearing.

Several years before the death of Matthew Shepard—in the parking lot of a drag bar in Albuquerque, New Mexico, a Navajo drag queen was stabbed to death. A month later another Native drag queen was stabbed to death. And then another. Three Native drag queens killed in the course of a two month period. The police attributed it to a “domestic violence” situation where each girl was killed by a close friend or relative. There was no in depth investigation and there is still no arrest for all three murders.

I know if I was found dead in a Gallup field, the white (now even Navajo or Zuni Pueblo) officers who would find me would not give a second thought as to how I would have died. They would presume I died from an alcohol related death or a drug overdose or from a murder committed by one of my drinking friends over money.

And if they found out I was gay, there would be no investigation about a “hate crime.” Just like the numerous “fag bashings” that happen all the time in Gallup, the police would show up and settle the “domestic” dispute but not arrest anyone unless it’s the gay person who is being disruptive or drunk.

So I waited until I was 20 years of age and in the San Francisco Bay Area. Presumably not the most liberal place in the world but certainly one of the more open cities in the US and I felt relieved.

My family didn’t reject me. My mother cried. My sister Cindy told me, “No matter what I will always love you.”

And if I was white that would be the end of the story. But I’m not. I know when I walk down the streets in Gallup, no matter what I’m wearing, where I’ve been, what I know or do not know, all my complexity can be reduced down to my hair, my color and my profile. White tourists speak slowly to me when they ask for directions or make the extra effort to be even more considerate but just short of being truly condescending. But it just isn’t white tourists.

I come home and go to the flea market or the Indian Health Service clinic and folk always begin speaking Navajo to me before I interrupt and correct them. They always seem disappointed I don’t speak Navajo fluently. Even though, if they press the issue I tell them my mother’s Jicarilla Apache, they still insist I should know. On the one hand, it’s good to have the expectation, on the other, it’s a burden that I’m not sure is mine.

My parents made the choice for me about whether I was to speak their languages or not. Both of my parents primary languages were Navajo and Jicarilla Apache. My father was taken away to boarding school at the age of 6, my mother at the age of 5. They were both abused and subjected to humiliating efforts to burn English into them.

My mother remembers—when she lets herself—as a young girl being in her nightgown at 3 a.m. cleaning the cement steps to the Santa Fe Indian School with her only toothbrush. Her crime was speaking Jicarilla Apache to the other Apache girls. My dad doesn’t speak of his boarding school years.

It was this history my parents remembered when the decision came of whether or not to teach their children their first languages. It was this and the racism they faced away from their respective communities that shaped their views. I blame them for nothing.

We can’t undo history. What’s done is done. If I choose to learn the languages now, it should be my privilege to do so, but not my burden. Which doesn’t mean I’m not glad other people grow up bilingual (and with more and more bilingual programs, this will surely increase), but I’m not going to feel bad either because I’ve had the history I’ve had. It’s maddening what we put ourselves through in order to feel we belong somewhere. I cannot help but belong where I was born and to whom I am related.

Yet even in my primary language, I am not completely welcome. In my senior year at Stanford, I went to ask for help from the Director of Undergraduate Studies in the English Department. I told him my English advisor, who was going through tenure review at the time, was too busy to offer me sufficient help to finish my senior thesis (which was no fault of my advisor’s, I felt). I told him my thesis, about American Indian women’s poetry and American Indian gay and lesbian poetry, needed the academic leadership that the department wasn’t otherwise providing. I told him my concerns as a Native person weren’t being met.

He, without any pause or long consideration, told me my concerns as a Native person did not matter. “I don’t think your concerns as a Native person are significant.” I said nothing for a while and then thanked him for his help and left his office. Later that quarter I didn’t finish the school session but “walked” at graduation nonetheless. I left Stanford without a degree in 1999 and didn’t return until 2002 to finish.

So three years later when I returned to Stanford to finish my English degree, I tried harder to fit in as an urban gay Native in San Francisco.

I would walk down the Castro and go into A Different Light bookstore and never feel more brown. Like an anthropologist or a hobbyist, I knew exactly where the gay “Native” section was and made a beeline to it. The few books they had were mostly by lesbians and the couple of gay Native book’s authors were whiter than the blonde man who kept eyeing me the whole time I was there.

To most gay men I am Asian or Latino, at the very best, exotic. Even knowing this, with this attractive white man staring at me, I had felt cute. I walked up to him and said “Hi.” He said, “I’m not into Asians.” I didn’t correct him. I said nothing. Gay white men have been the only other ones to make me feel most ashamed of being different.

That June, I went to the 2002 Gay Pride potluck for the Bay Area Native community. Again Cher’s “Half-breed” played in the background. Besides me there were two other Navajo men, (one of whom was afflicted with AIDS) and a dark brown women of indeterminate Nation. She kept looking across the table at me, lost, like she knew me but had forgotten my name. Most everyone was nice but otherwise blond and blue-eyed.

Yet it still didn’t feel like home. Except for one moment when the Navajo guy with AIDS, who had his white partner with him, who was also afflicted, started to eat. The white guy got up and got a plate of food for his light brown partner, kissed him on the forehead, put a fork in the guy’s hand and helped him to eat.

That one kiss denied a history of me not existing, it denied the idea that I do not love. It told me I exist, not in spite of everyone, but because of everyone. It told me that home for some of our people is wherever they make it.

****

A lot of the rhetoric in the literature on Native peoples is all culture-speak about what’s supposedly going on with us: traditional or modern, loss of culture or return of culture. It seems like everyone thinks we’re supposed to be only one or another, rather than just being who we are, living the history we’re dealt. They say we live in “two worlds.”

I’ve learned in school that “culture” is a concept with historical roots primarily in anthropology, which from what I’ve read, isn’t about Native lives so much as it is concerned with making up “truths” about them. The term “culture” does not exhaust the Native experience in any significant way.

I for one, do not live in two worlds. I live in one world, granted, one that at times, has a lot of white people in it, but one world nonetheless. And even though I have no clear idea who I am at every moment, I think I should have some leeway as far as finding out who I am. To read some of the academic or creative literature on Native people, you’d think we’d all have to be perfectly “Indian” by 25. I certainly believe my ancestors didn’t die so their progenitors would have to fit some untenable model of what a Native should be to fulfill white fantasies about our history.

But the one-history report of who Native people are will continue because there aren’t other voices published and disseminated. And there are a whole lot of Native identified writers who don’t come from Native communities that need to make ends meet so this story will continue.

We all have culture, whether we like aspects of it or not is up to ourselves to decide. Whether or not that culture is “Native” or not is up to the community of people from which we claim association to decide.

We’re constantly told what is supposed to be “traditional.” But I know stories about “traditional” medicine men who beat their wives, and in one horrible case, have molested their children. There was a story in the Gallup Independent about a medicine man raping a woman who went to him for help.

I know Gallup fills up at the first of the month with grandchildren and children who wait for their parents’ or grandparents’ social security checks to buy new TVs or stereos, to go out to eat, or to drink their entire checks away. I know persons who’ve stolen their grandmother’s Pendleton blankets and jewelry and pawned them for alcohol. These same people would say I act too white or need to become fluent in Navajo.

I also know good Christians, good Native American Church-goers and several good urban Navajo, who don’t have any religion. These people would not be considered “traditional” but do not hurt themselves or others.

I also know many good people, including my grandparents, who cannot help but live how their parents, their grandparents and their great-grandparents have lived.

We all have culture, whether we are good people or not is informed by that culture but not determined by it. There is no one “culture” that automatically makes you a good person. It is how you live your life. There are many paths to beauty, as the saying goes.

Our experience is more and less complicated than the literature attests. This needs to change. I, myself, have four fingers on the edge of a rainbow and I am leaning into the cool mist of an ever expanding present, getting less and less afraid every day to say what I mean.

****

I know what it is like to be among the mountains and in the ceremonies of my mother’s people. I know what it is like to be walking into Bloomingdale’s at Stanford Shopping Center and buying the Salvatore Ferragamo half boot, and then into Kenneth Cole’s, and buying the 50’s inspired black polyurethane jacket all the sporty gays were then wearing to the clubs without a second thought and without any spending money for the rest of the term. I do not live in two worlds. I live in one world, where I make both good and bad choices, one in which I know there are other Natives with less and more power to choose than I have.

My ancestors made a choice, the same one all Native people do at some point, whether it is a quick thought or a long drawn out deliberation, we have all made the choice. When we’re young for some, when we’re old for others, and then there are those who make it for years at a time: the choice of whether to live or die.

For many it is as if there is almost no thought to the choice they make. For others there is the seven years’ time, or fourteen years, or a life time of living to choose. My ancestors made the choice to go on living, through a tuberculosis plague, the onslaught of white people, Comanches to the east and Cheyenne to the north. I’m not sure if it was a simple choice for them or a hard won one but I know they made it because I am here now. I am the exponential sum of my ancestors’ prayers, dreams, and love for one another.

And at the end of all the drama is me and even if I’m brown, Native, dirty, stupid, poor, gay, backward and crazy—it doesn’t matter. Because just like my ancestors, I’ll go on as well.

Sometime within the past seven years, I made the choice to keep going, to not stop until I can walk no more and I lay my life down and rest. Like my parents, my grandparents, my clansmen and clanswomen, my people—I will go on.

I live between white people and Native people, and choose the one by denying the other. I live between male and female. I live between my ancestors and my own uncertain future, trying to remember the prayers that kept them going. I live between Jicarilla Apache and Navajo. I live between the reservation and the city. I used to live between the living and the dead. I used to live between my dreams and reality, destroying my successful future so I could have an anguish-free present of poverty. I choose a life of non-contradiction. I choose to not have to choose either one or the other. I choose to live indeterminate, ambiguous, in-between and always changing.

Dwayne Martine | is a poet and writer living in Scottsdale, Arizona. He has been published in

national and regional print and online journals, including Kweli, Malpais Review, Yellow Medicine Review and others. He has an undergraduate degree in English from Stanford University. He works as a professional technical writer in the financial services industry.

0 notes

Text

Day 41

6/ 15/ 17

Late post: So I wrote this on Tuesday, but then got too busy to post. Awk.

“When it rains, it pours.” Literally speaking, I suppose. I felt so bad for the nugs today because it was literally pouring this morning right when we were supposed to leave for school. unfortunately, when it pours here, most schools get cancelled. Our school, in particular, is so far out in the barrios that there aren’t paved roads for at least a mile. That means most kids live on dirt roads. When dirt and rain mix, a lot of mud happens. The kids slip and fall in the mud, then their only uniform (or one of their only sets of clothes) gets dirty. Once their clothes gets dirty, their mothers have to hand- scrub the clothes to get them clean, and dry them out in the sun. So today school was cancelled, and the kids had to stay at home and inside.

I had a very relaxing day, however. I relaxed all morning, listening to music and browsing Pinterest looking for new lesson plan ideas. I’ve been into this group called Shane and Shane after Lydia introduced them to me. They’re so good! Anyway, once I got bored, I decided to treat myself to brunch, so I went to Kathy’s waffle house. I should’ve taken a pic of my food because it was so hashtag Nica. I had gallo pinto, eggs, bacon, and a thick piece of toast. I also had coffee… the good Nica coffee, not the yucky American stuff. As I casually ate brunch, I played catch up with El Internado. I’m so close to finishing the series and it’s really helping me with my Spanish!

After brunch, I went to Spanish class. The walk there was surprisingly nice because it was cool since it had just rained. Class went really well today. I was able to talk a lot and understand almost everything, so I really feel like I’m improving. Who knows, maybe I’ll be basically fluent by the time I return home *she said with a glimmer of hope in her voice*.

After Spanish and before the Tuesday meeting for La Esperanza volunteers, there was an awkward time gap, so I decided to re- listen to a podcast I listened to yesterday. I listened to a Hillsong podcast called #LEVELS and it was SO good, but I was listening for enjoyment. I miss hearing my normal 3- point messages with a clearly defined outline and goal. Yesterday’s message was so good that I want to listen again and take notes, because I really think it totally applies to my life right now.

The meeting was of course, pointless. I truly don’t understand why we have them. We make the new volunteers say their name (even though we send an email to everyone saying who the people are) and we make the old volunteers say goodbye. At least it was quick, so that was good. Afterwards, I was able to hang out with the interns. We had good talks and lots of laughs.

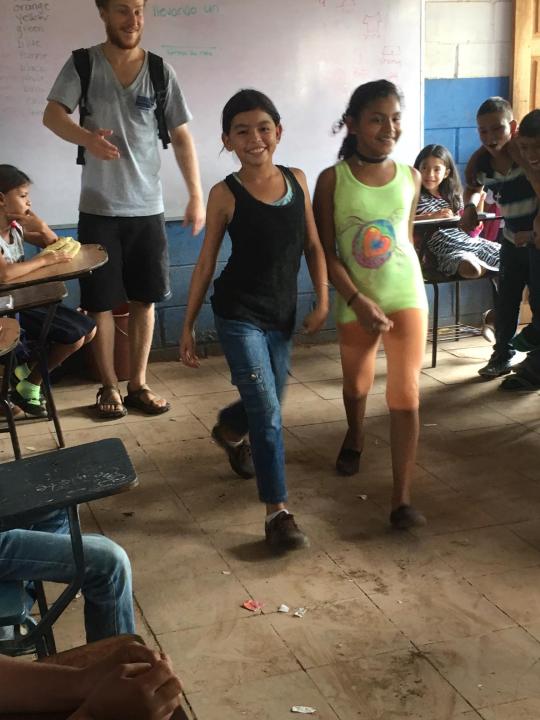

The past two days have been great at school, except for one hiccup. We had to have a kid physically removed and carried to the principal’s office because he wouldn’t stop fighting the other students, teachers, and volunteers. So that was sad. Luckily, he was able to regain his composure and come back to class. So we finally released my “big” idea with the kids. It didn’t exactly work out as planned because hashtag Nica probs (ex. canceled class, not knowing which classes will show up, lack of materials, etc.), but it’s okay because the kids loved it and we made do with what we had. We had a… Fashion Show! In most of the classes, we moved the desks to the sides of the room to create a runway and then had a chair for the kids to stand on when they got to the end of the runway. When they got on the chair, they were able to announce what they were wearing. We’ve been learning how to describe things (ex. green shirt, or black shoes). One class even got to use the stage in the front of the school and the other kids got to stand in front of the stage clapping and cheering. It was so much fun and so exciting to see the kids strutting down the runway.

After school today, I went to Spanish class. Even though I was completely exhausted, I pushed through and I learned a lot and remembered even more than I thought I would. I was pretty proud of myself.

Tonight I’m going to worship night with the interns and the mission team that’s here this week, and after that I’m going to celebrate Jada (the middle child in the Sandino dam… se previous posts)! It’s her birthday so we’re going to Wok in Roll, which is literally the best Asian restaurant in Nicaragua.

So overall, everything is going really well. Please pray for a great planning period tomorrow. It will be the last planning period with Lucas, the only boy on our English team, because he’s going home this weekend. On that note, please pray that we either get another strong male figure, or that the team and I can step up in incredible ways to really get these kids under control (mostly concerned with the fist fights).

Stay Salty & Shine Bright,

Heather

0 notes