#Hilary Mary Mantel

Photo

Dame Hilary Mantel, who has died aged 70 after suffering a stroke, was the first female author to win the Booker prize twice, which she did for the first two volumes in her epic trilogy of the life of Thomas Cromwell, Wolf Hall (2010) and Bring Up the Bodies (2012). The novels, which collectively weigh in at about 2,000 pages, have sold 5m copies worldwide, were made into an acclaimed BBC series (2015) staring Mark Rylance, and adapted by Mantel herself for the RSC stage version (2014), a process that she loved. The trilogy culminated with The Mirror and the Light (2020) and the death of Cromwell; it turned out to be her final novel. All told in the present tense, the novels constitute a feat of immersive storytelling and a monumental landmark in contemporary fiction.

Before Cromwell, Mantel had written nine novels, including A Place of Greater Safety (1992), about the French Revolution; Beyond Black (2005), a characteristically dark and idiosyncratic tale of a medium in Aldershot; a memoir, Giving up the Ghost (2003); and three collections of short stories. Although she received good reviews, her sales were modest and none of her novels had even been longlisted for the Booker. “I felt very much like a niche product, very much a minority interest,” she said in an interview with the Guardian in 2020. But it was only with Cromwell and her decision “to march on to the middle ground of English history and plant a flag”, as she put it, that she found a huge readership. It was the novel she had been waiting all her career to write.

Born Hilary Thompson in Glossop, a village in Derbyshire, she was the daughter of working-class Catholic parents with Irish ancestry who had moved to Manchester; her mother, Margaret (nee Foster), like her mother before her, had left school to work in a mill when she was only 14. Hilary’s father was Henry Thompson, but she took her surname from her mother’s second husband, Jack Mantel.

Hers was not a happy childhood. “The story of my childhood is a complicated sentence that I’m always trying to finish, to finish and put behind me,” she wrote in Giving up the Ghost. If she were to give it a pigment, she continued, it would be “a faded, rain-drenched crimson, like stale and drying blood”.

When she was six, a man called Jack had come for tea, she wrote. “One day Jack comes for tea and doesn’t go home again.” The neighbours gossiped and children at school teased her about their living arrangements.

They all lived together until her mother and two younger brothers moved to a semi-detached house in Romiley with Jack. She never saw her father again. “My childhood ended so, in the autumn of 1963, the past and the future equally obscured by the smoke from my mother’s burning boats,” she said. Until she was 12, she was a devout Catholic, and she went to Harrytown Convent school, Romiley.

She met her husband, Gerald McEwen, when they were 16, marrying in 1973, the year that she graduated from Sheffield University with a law degree. Instead of becoming a barrister as she had planned, she got a job in a department store and started reading about the French Revolution. She said she never thought of becoming a novelist until she “actually picked up a pen to become one” and even then it was only because she felt she had missed her chance to become a historian. She started her first novel, A Place of Greater Safety in, 1974, when she was 22. It would be two decades before it was published. In 1977 she and Gerald were sent to Botswana for his work as a geologist. She started teaching, but in her head she was always in 1790s France, writing whenever she could.

The impulse to write grew out of her sense that something was seriously wrong with her. While she was at university she started having terrible pains, but was told they were psychological and was prescribed antidepressants and anti-psychotic drugs. There followed years of pain, misdiagnosis and denial. It was only in a library in Botswana that she self-diagnosed severe endometriosis. When she was 27 and back in England over Christmas, she collapsed and underwent major surgery at St George’s hospital, which was then at Hyde Park Corner, central London, “having my fertility confiscated and my insides rearranged”, as she described it.

But it was recovering from the operation that cemented her determination to write. Unable to find a publisher for A Place of Greater Safety – it was not a great time to be trying to publish historical fiction – she shrewdly changed tack, forming what she called “a cunning plan”, and started on a contemporary novel, Every Day Is Mother’s Day, which was immediately snapped up in 1985, followed a year later by a sequel, Vacant Possession.

While her literary career was finally taking off, her marriage was foundering, and a year after her operation she and Gerald divorced, with Mantel returning to Britain. Gerald also came home, and barely two years later they remarried so that he could take up a job in Saudi Arabia. They moved to Jeddah in 1982, and this provided the inspiration for her fourth novel, Eight Months on Ghazzah Street (1988). A Place of Greater Safety was published four years later.

After returning to Britain, for many years she was a lead book reviewer for the Guardian, as well as film critic for the Spectator. Although sitting on various committees – the Royal Society of Literature, the Society of Authors and the Advisory Committee for Public Lending Right – and teaching, she never saw herself as part of any literary set, and was always slightly apart from her famous contemporaries such as Martin Amis, Ian McEwan and Salman Rushdie. The publication of The Giant, O’Brien in 1998 and Beyond Black in 2005 saw her begin to break out of being “a literary novelist” – at least in terms of sales.

And then came Cromwell. It was no small irony that after years of not being able to publish her first historical novel, she found fame with a book set during the reign of Henry VIII. “It was as if after swimming and swimming you’ve suddenly found your feet are on ground that’s firm,” she said. “I knew from the first paragraph that this was going to be the best thing I’d ever done.”

The debilitating pain and periods of ill health of her early years never left her. And in 2010, shortly after winning the Booker prize for the first time, she was back in hospital for yet more operations, a period she chronicled in a diary for the London Review of Books. “Illness strips you back to an authentic self, but not one you need to meet. Too much is claimed for authenticity. Painfully we learn to live in the world, and to be false,” she wrote.

After the success of Wolf Hall, she and Gerald moved to the Devon seaside town of Budleigh Salterton, which she had visited when she was 16 and where she had promised herself she would one day live. Gerald became her manager and was always her first reader. Never afraid of long hours, she liked to write first thing in the morning, and when she was deeply immersed in a novel she often would write in bursts during the night. She still had many notebooks full of ideas and projects she wanted to begin.

In 2013 she caused a minor outcry in a speech at the British Museum in which she described Catherine Middleton as a personality-free “shop window mannequin”, drawn from her fascination with public perceptions of the female body, and she wrote a powerful essay for the Guardian to mark the 20th anniversary of the death of Princess Diana. She was made a dame in 2014.

As her agent of nearly 40 years, Bill Hamilton, said: “You always have to remember how much her background and ferocious intelligence made her an outsider, and how her chronic ill health made her a stranger even to her own body. In her writing she had to invent everything from scratch. She wrote eloquently about how hard it was to know what each new sentence had to contain, and what surprises lay just round the corner, like the presences that populate her books: ghosts, and the ghosts of what the future might hold.”

Mantel did much to encourage other writers, and was generous with her time for anyone she met professionally. Equally, Hamilton said: “When success arrived she enjoyed it gleefully, as she knew it was so hard-earned.”

Gerald survives her.

🔔 Hilary Mary Mantel, author, born 6 July 1952; died 22 September 2022

Daily inspiration. Discover more photos at http://justforbooks.tumblr.com

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

anne boyer “the harm will come: it never doesn’t” / julia armfield “to watch a horror movie is to know that something bad is going to happen. to have a body is really the same thing” / hilary mantel “we don’t have to invite pain in, it’s waiting for us: sooner rather than later” / marie howe “you know how we’ve been waiting for the big pain to come? I think it’s here. I think this is it. I think it’s been here all along” / gregory orr “I want to go back to the beginning. we all do. I think: hurt won’t be there. but I’m wrong” / toni morrison “the hurt was always there” / torrey peters “pain that had to be endured, withstood, pain that was the same as being alive, and so without end”

#so you know#w#comparatives#anne boyer#julia armfield#hilary mantel#marie howe#gregory orr#toni morrison#torrey peters#the harm will come it never doesn’t

7K notes

·

View notes

Text

˙✧˖°📷 ༘ ⋆。˚ First-look pictures for Wolf Hall Season 2

Mark Rylance as Thomas Cromwell | Thomas Brodie-Sangster as Rafe Sadler | Harriet Walter as Lady Margaret Pole | Damian Lewis as King Henry VIII | Harry Melling as Thomas Wriothesley | Lilit Lesser as Princess Mary | Charlie Rowe as Gregory Cromwell | Timothy Spall as the Duke of Norfolk and Alex Jennings as Stephen Gardiner | Kate Phillips as Jane Seymour — x

#wolfhalledit#wolf hall#hilary mantel#thomas cromwell#mark rylance#henry viii#jane seymour#mary i#damian lewis#thomas brodie sangster#harriet walter#lilit lesser#timothy spall#kate phillips#wolf hall cast#weloveperioddrama#tudorerasource#*#tudor era#period drama#pics

169 notes

·

View notes

Text

Trastamara girls born after 1485 can’t cook. All they know is charge they phone, get abandoned by they father, eat hot chip, have complicated pseudo sexual relationship with male authority figure, twerk, and lie. (About their virginity.)

#the complicated relationship comment is about Mary & Chapuys/Catherine & Diego Fernandez#but if you’re one of those Phillipa Gregory girls it could always be about her and Henry VII :3#oh and you know who else? Mary and Cromwell#gotta throw Hilary Mantel a bone#thomas cromwell#mary i of england#katherine of aragon#eustace chapuys#diego fernandez#ferdinand ii of aragon#king henry viii

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Any recommendations for authors with a beautiful writing style that will make me feel emotional? I mean something like Robin Hobb (or even Juliet Marillier and Patricia A. McKillip). Some classic literature also have it because they used to be very dramatic with their feelings. That's what I want.

I appreciate some quotes as examples just so I can check if it's the kind of writing I am looking for.

Authors I have on the list to try already: Dorothy Dunnet, Mary Renault, Hilary Mantel, Sharon Kay Penman, Carolina de Robertis

Some examples of what I am looking for:

"The knowledge that he had left me with no intent ever to return had come over me in tiny droplets of realization spread over the years. And each droplet of comprehension brought its own small measure of hurt...He had wished me well in finding my own fate to follow, and I never doubted his sincerity. But it had taken me years to accept that his absence in my life was a deliberate finality, an act he had chosen, a thing completed even as some part of my soul still dangled, waiting for his return." (Fool's Assassin by Robin Hobb)

"I did not want to think about people. I wanted the trees, the scents and colors, the shifting shadows of the wood, which spoke a language I understood. I wished I could simply disappear in it, live like a bird or a fox through the winter, and leave the things I had glimpsed to resolve themselves without me." (Winter Rose by Patricia A. McKillip)

"Whenever I find myself growing grim about the mouth; whenever it is a damp, drizzly November in my soul; whenever I find myself involuntarily pausing before coffin warehouses, and bringing up the rear of every funeral I meet; and especially whenever my hypos get such an upper hand of me, that it requires a strong moral principle to prevent me from deliberately stepping into the street, and methodically knocking people's hats off - then, I account it high time to get to sea as soon as I can." (Moby Dick by Herman Melville)

#robin hobb#patricia a. mckillip#herman melville#dorothy dunnet#hilary mantel#mary renault#sharon kay penman#carolina de robertis#I am trying to organize the recs according to what I asked for so I can pick accordingly in the future#I like drama queens is what it is#characters that feel very deeply#books#book recs

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

So apparently Hilary Mantel"sf inal project was a retelling of Pride and Prejudice from Mary's pov....it's fanfiction.Jane Austen fanfiction.

#look if she could make jane Seymour interesting im sure she would have no trouble with mb#jane austen#hilary mantel#pride and prejudice#mary bennet

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

many years ago i watched the wolf hall tv series and was briefly obsessed with it. now i’ve finally taken it upon myself to read the books and i cannot believe i waited this long. i find myself truly in awe at mantel’s writing and character work

#wolf hall#thomas cromwell#obsessed with so many things about this book#mantel’s writing is so immersive and biting and colourful#i love the character dynamics so much; especially thomas/mary boleyn and cromwell/gardiner#hilary mantel#maddie.txt

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

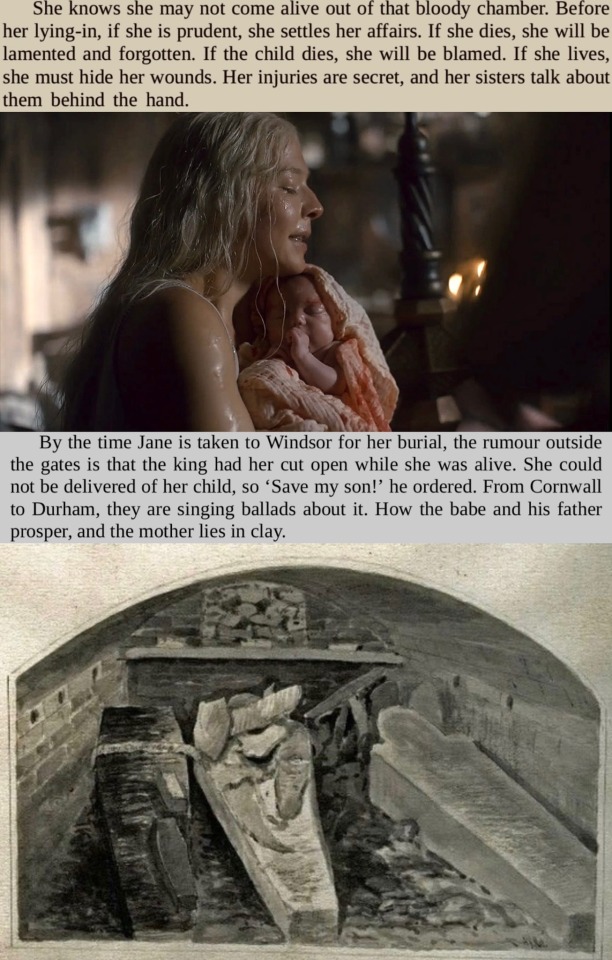

From Mantel Pieces by Hilary Mantel

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

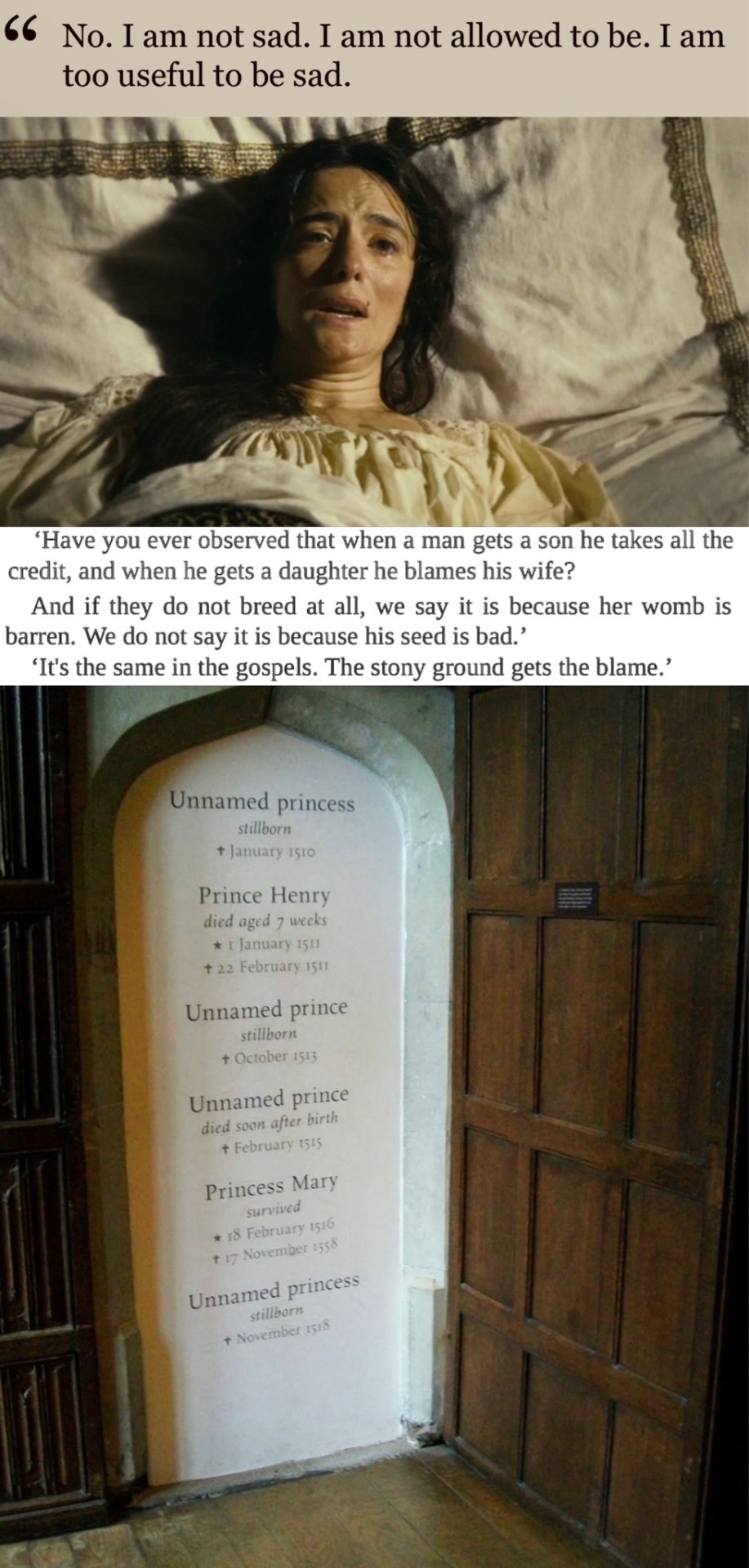

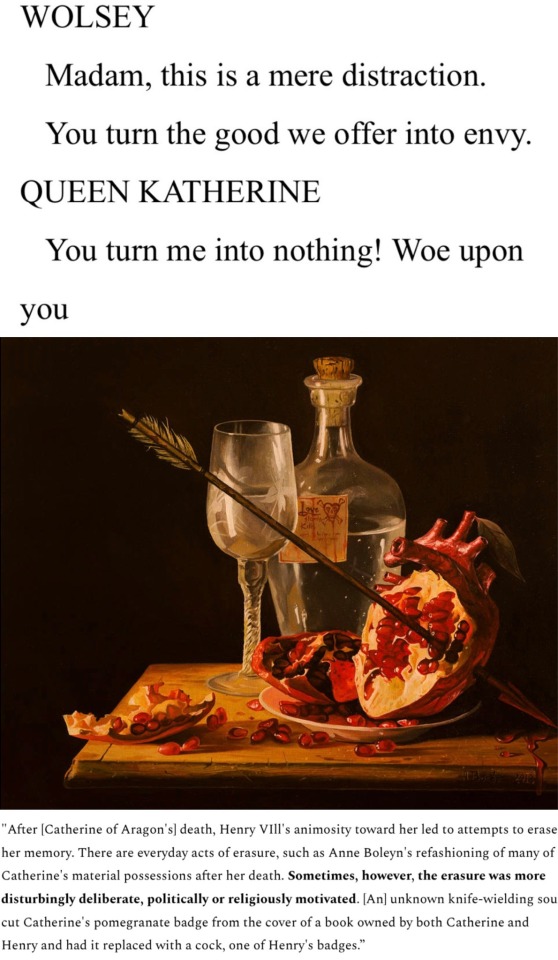

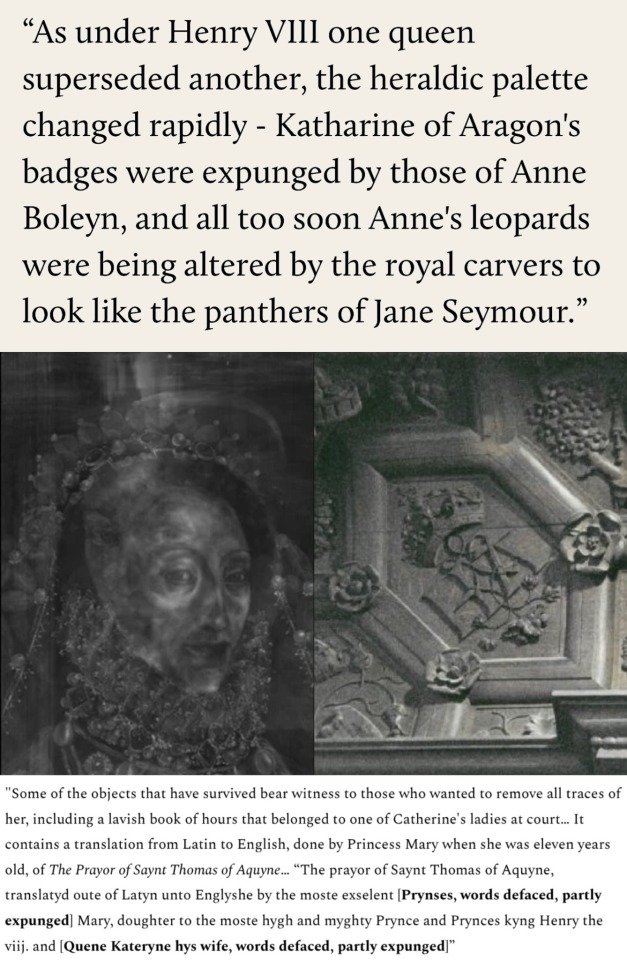

YOU TURN ME INTO NOTHING, WOE UPON YOU

The Mirror and the Light, Hilary Mantel / Ana Torrent in The Other Boleyn Girl / Wolf Hall, Hilary Mantel / memorial for Catherine of Aragon’s children at Hampton Court / Henry VIII, William Shakespeare / Love Slowly Kills, borda / Catherine of Aragon: Infanta of Spain, Queen of England, Theresa Earenfight / Houses of Power, Simon Thursley / Portraith with a serpent, X-Ray , unknown painter / Henry VIlI and Anne Boleyn's initials, King's College Chapel, Cambridge / Catherine of Aragon: Infanta of Spain, Queen of England, Theresa Earenfight / 29 January 1536 – Anne Boleyn “Miscarried of her Saviour”, Claire Ridgeway / Natalie Dormer in The Tudors / The Mirror and the Light, Hilary Mantel / Postcard, Amazon Quarterly / Roman Marble Relief of the Three Graces, circa 2nd Century A.D. / Catherine of Aragon: Infanta of Spain, Queen of England, Theresa Earenfight / Poster for Mother!, James Jean / The Mirror and the Light, Hilary Mantel / Unfinished portrait of Jane Seymour, after Hans Holbein the younger / This Is Not The Portrait Of Jane Seymour, Edoardo de Falchi / The Mirror and the Light, Hilary Mantel / Emma D’Arcy, House of the Dragon / The Mirror and the Light, Hilary Mantel / Henry VIII’s vault, A.Y. Nutt / The Mirror and the Light, Hilary Mantel / Saiorse Ronan in Mary, Queen of Scots / 1782 depiction of Katherine Parr’s lead coffin, unknown / The Mirror and the Light, Hilary Mantel / a piece of hair cut from the head of Katherine Parr, collection of Sudeley Castle / a piece of Katherine Parr’s burial gown, collection of Sudeley Castle / The Mirror and the Light, Hilary Mantel

#historicwomendaily#katherine of aragon#katherine parr#jane seymour#anne boleyn#catherine of aragon#henry viii#wolf hall#miscarriage tw#blood tw

748 notes

·

View notes

Text

Kate is not your drama queen Her self-possession drives people wild - Jenny McCartney UnHerd.

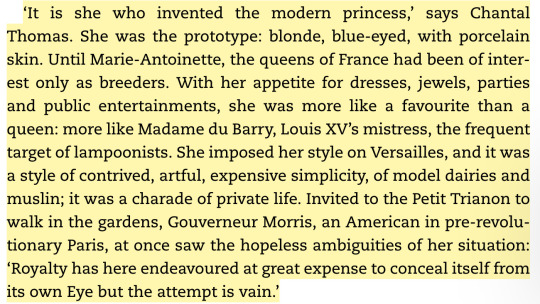

Just over a decade ago, the late novelist Hilary Mantel delivered a lecture to an event at the London Review of Books and triggered national outrage. In the course of a talk on “Royal Bodies”, which ranged widely across royal women from Anne Boleyn to Marie Antoinette and Princess Diana, she had made what many perceived as disparaging remarks about Kate Middleton, then the Duchess of Cambridge. The Duchess, she said, appeared to have been “designed by a committee and built by craftsmen, with a perfect plastic smile and the spindles of her limbs hand-turned and gloss-varnished”. Indeed, Mantel said, Kate “seems to have been selected for her role of princess because she was irreproachable: as painfully thin as anyone could wish, without quirks, without oddities, without the risk of the emergence of character”.

At this, the newspapers were soon in uproar. The prime minister David Cameron called the comments “completely misguided and completely wrong” and the Labour leader Ed Miliband agreed they were “pretty offensive”. Mantel doggedly refused to back down, saying that her remarks had been twisted out of context, and that she was in fact writing with sympathy about the perceptions that are forcefully projected on to royal women, the cage in which they are held to be goggled at. That was true, but also perhaps not the entire truth, for there was still a perceptible trace of authorial vinegar in the portrait: which of us would be happy to learn, even in sympathy, that we were held at low risk for “the emergence of character”?

Royals are public as well as private figures, of course, and authors are free to hang intellectual ideas on them to try out, as designers do with clothes. Yet while much of the lecture was sharply perceptive, I didn’t agree with the portrait of Kate. That word “selected” had rendered her passive, when in fact her behaviour thus far had suggested both an active intelligence and an unusual degree of self-discipline. The context of her entry into “The Firm” was different from that of other royal brides. Unlike Diana, who had barely emerged from the fractured chrysalis of her troubled aristocratic family when she first met the much older, more worldly Prince Charles, Kate was a contemporary of Prince William’s at the University of St Andrews. Her family background, which appeared warm and supportive, was comfortably middle-class. She seemed generally cheerful and unruffled, even when the press was at the barbed peak of its “Waity Katie” hysteria, trying to goad Prince William into a proposal or abandonment.

After the wedding, in her approach to royal duties, she clearly took the role she had inherited with marriage seriously. The royal whose attitude her own most resembled was the late Queen Elizabeth II, who had long understood the essential nature of the job: to turn up to public events looking the part, intuit precisely what was needed — gravitas, fun, consolation or reassurance — and deliver it while keeping one’s personal emotions on the back burner. This is what a monarchy demands, and the ability to act as an impeccable interpreter of the public mood, year after year, is a particular and testing art. A few have a natural aptitude for it, but most of us do not, and would quickly find its scrutiny and restrictions intolerable.

Grace under consistent pressure is an admirable quality. Were a ballet dancer to execute a string of flawless performances, or a pilot to conduct numerous flights without incident, it would not be deemed evidence of an absence of character: quite the opposite. Yet in Kate — especially for those who increasingly conduct their lives online — serene self-possession seems to drive a proportion of onlookers insane: what lurks behind it, what dark secret is waiting to destroy it, how best might it be disrupted? The uncomfortable truth is that what many people deeply crave in a young and beautiful royal wife and mother is not competence, but crack-up

The increasingly bizarre treatment of Kate, or the idea of Kate, is connected to the most dominant phenomenon of our age: a cultural prioritising of drama over duty. The supply of drama has spilled beyond the confines of the novel, theatre, cinema or television to become a commodity on which our public figures are judged. When Mantel spoke of Kate’s apparent absence of emerging “character” she was assessing her primarily through the hungry eyes of a novelist. In books, central female characters often generate dramatic tension by chafing against their circumstances, by the intensifying dazzle of their discontents, something that Kate refused to transmit. In contrast, Mantel described Diana as a “carrier of myth”: Diana, publicly trapped in the disappointments of her marriage, certainly carried more plot twists than any author had a right to expect. Unfortunately for her, the final one was her shockingly premature death.

Set against this artistic conception of “character” — distinctive qualities or flaws that, one way or another, deliver drama — is the societal judgement “of good character”, meaning someone who is broadly reliable and respected in relation to their behaviour to others. In recent years the electorate, in line with Neil Postman’s warning in his 1985 book, Amusing Ourselves To Death, has proved increasingly ready to select the former over the latter, even to the marked detriment of our civic health. The former prime minister Boris Johnson instinctively understood it as his job not to deliver the detail of workable policy, but to satisfy the public’s appetite for story: “People live by narrative,” he once told UnHerd’sTom McTague. In the US, Donald Trump — that relentless generator of low mockery and high fury — is now running for a second term as president, after his first one ended in his supporters storming the Capitol building.

Men are often permitted to survive the frantic generation of drama: it is everyone around them who suffers. Yet women — in art and life — have a greater tendency to be destroyed by it. There is no strutting female equivalent of the male “hellraiser”, but rather a woman who, soaked in the crocodile tears of the tabloids, is tragically “causing concern” among friends. Art and its audiences have always relished the restless struggle and disintegration of female characters who are, or become, unmoored from the harbour of marriage and children. Flaubert’s Emma Bovary — her imagination inflamed by reading novels — is bored with her marriage and disenchanted with motherhood; she seeks solace in affairs and excessive spending, the consequences of which hasten her suicide. Zola’s Nana, a courtesan who ruthlessly captivates Parisian society, has her beguiling face eaten away by smallpox. Janis Joplin and Amy Winehouse, immolated on their blazing talent, are hung posthumously high in the musical hall of fame, next to Sylvia Plath in the poetry section and Marilyn Monroe in cinema.

In Jean Rhys’s Good Morning, Midnight,a middle-aged English woman called Sasha Jansen, mourning an unhappy marriage and a dead child, finds herself in Paris, a vulnerable drifter seeking solace from stray men. Rhys herself, who died at 88 after a precarious but surprisingly long life, had much in common with her literary creations. As the writer and editor Diana Athill crisply put it: “Jean was absolutely incapable of living, life was just hopelessly beyond her. When she was young, she floated from man to man in a hopeless way… by the time she was old, she floated from kind woman to kind woman.”

In Rhys’s latter years — hard-drinking, irascible and impoverished — Athill and a small group of female friends formed what they called “The Jean Rhys Committee” which met regularly to ask “what should we do next?”. Rhys’s claim to such loyalty, I suppose, was the weight of her literary talent, her ability to exert an odd kind of fascination, and the fortunate soft-heartedness of her friends. The dramatic collided with the dutiful, and was kept alive by it.

From what I can see, the Princess of Wales exists at the opposite end of the feminine spectrum from Jean Rhys. Pinned firmly in place by her royal obligations, her wealth, her marriage and three children, she belongs to the realm of the respectable and dutiful rather than the erratic and dramatic. She is not a “character” in the artistic sense, nor does she desire to be, but both a survivor and upholder of an institution: hers is the territory of the prompt thank-you note, the kept promise, the commitment to public service, the uncomplicated pleasure in children, the stoic endurance of difficult times in the hope that better ones will come along soon. The public senses an emotional solidity in her, and it is partly why she is held in broad esteem. In this age of insistent self-definition, duty to others might be an unfashionable concept, but it is nonetheless one that keeps families and institutions from chaos and collapse.

With the advent of the internet, however, anyone with a keyboard can become a form of author, with the freedom to insert a toxic form of drama into real-life situations. What was extraordinary, during the Princess of Wales’s recent health problems, is how speedily and carelessly such speculations overrode the bounds of decency. It was already known that she had undergone major abdominal surgery, and was taking time to recover. And yet — egged on by the participation of silly celebrities and malicious US comedians — conspiracy theories about cosmetic surgery and affairs and nervous breakdowns spread like knotweed. According to social-media researchers, these were also vigorously introduced and amplified by fake accounts set up on Twitter and TikTok, some associated with Russia-linked disinformation eager to spread the termites of mistrust and doubt in Western institutions. Only the Princess of Wales’s revelation of cancer, which carries a testing drama all its own, served to shut up the majority of them.

Unlike these callous gossips, Mantel recognised her own complicity in dehumanising royalty. Upon encountering the late Queen, the novelist said: “I passed my eyes over her as a cannibal views his dinner, my gaze sharp enough to pick the meat off her bones.” The Queen looked back at her, she said, briefly hurt. Mantel warned of the way in which “cheerful curiosity can easily become cruelty” precisely as it has done in recent weeks. Her talk concluded with a prescient instruction for those who comprehend monarchy mainly as a source of entertainment: “I’m asking us to back off and not be brutes.”

In the midst of treatment and recovery, the most hitherto stable of royal women could be forgiven a keen sense of injustice: her job description, it seems, must now include the ability to weather the online public’s fits of brutish mania for drama. With its contempt for duty, and its savage appetite for story, it is hungry to chew up far more than just the Princess of Wales.

71 notes

·

View notes

Text

Just over a decade ago, the late novelist Hilary Mantel (6 July 1952 – 22 September 2022) delivered a lecture to an event at the London Review of Books and triggered national outrage.

In the course of a talk on “Royal Bodies,” which ranged widely across royal women from Anne Boleyn to Marie Antoinette and Princess Diana, she had made what many perceived as disparaging remarks about Kate Middleton, then the Duchess of Cambridge.

The Duchess, she said, appeared to have been “designed by a committee and built by craftsmen, with a perfect plastic smile and the spindles of her limbs hand-turned and gloss-varnished."

Indeed, Mantel said, Kate “seems to have been selected for her role of princess because she was irreproachable: as painfully thin as anyone could wish, without quirks, without oddities, without the risk of the emergence of character.”

At this, the newspapers were soon in uproar.

The prime minister David Cameron called the comments “completely misguided and completely wrong” and the Labour leader Ed Miliband agreed they were “pretty offensive.”

Mantel doggedly refused to back down, saying that her remarks had been twisted out of context, and that she was in fact writing with sympathy about the perceptions that are forcefully projected on to royal women, the cage in which they are held to be goggled at.

That was true but also perhaps not the entire truth, for there was still a perceptible trace of authorial vinegar in the portrait:

Which of us would be happy to learn, even in sympathy, that we were held at low risk for “the emergence of character”?

Royals are public as well as private figures, of course, and authors are free to hang intellectual ideas on them to try out, as designers do with clothes.

Yet while much of the lecture was sharply perceptive, I didn’t agree with the portrait of Kate.

That word “selected” had rendered her passive, when in fact her behaviour thus far had suggested both an active intelligence and an unusual degree of self-discipline.

The context of her entry into “The Firm” was different from that of other royal brides.

Unlike Diana, who had barely emerged from the fractured chrysalis of her troubled aristocratic family when she first met the much older, more worldly Prince Charles, Kate was a contemporary of Prince William’s at the University of St Andrews.

Her family background, which appeared warm and supportive, was comfortably middle-class.

She seemed generally cheerful and unruffled, even when the press was at the barbed peak of its “Waity Katie” hysteria, trying to goad Prince William into a proposal or abandonment.

After the wedding, in her approach to royal duties, she clearly took the role she had inherited with marriage seriously.

The royal whose attitude her own most resembled was the late Queen Elizabeth II, who had long understood the essential nature of the job:

To turn up to public events looking the part, intuit precisely what was needed — gravitas, fun, consolation or reassurance — and deliver it while keeping one’s personal emotions on the back burner.

This is what a monarchy demands, and the ability to act as an impeccable interpreter of the public mood, year after year, is a particular and testing art.

A few have a natural aptitude for it, but most of us do not, and would quickly find its scrutiny and restrictions intolerable.

Grace under consistent pressure is an admirable quality.

Were a ballet dancer to execute a string of flawless performances, or a pilot to conduct numerous flights without incident, it would not be deemed evidence of an absence of character: quite the opposite.

Yet in Kate — especially for those who increasingly conduct their lives online — serene self-possession seems to drive a proportion of onlookers insane: what lurks behind it, what dark secret is waiting to destroy it, how best might it be disrupted?

The uncomfortable truth is that what many people deeply crave in a young and beautiful royal wife and mother is not competence, but crack-up.

The increasingly bizarre treatment of Kate, or the idea of Kate, is connected to the most dominant phenomenon of our age: a cultural prioritising of drama over duty.

The supply of drama has spilled beyond the confines of the novel, theatre, cinema, or television to become a commodity on which our public figures are judged.

When Mantel spoke of Kate’s apparent absence of emerging “character,” she was assessing her primarily through the hungry eyes of a novelist.

In books, central female characters often generate dramatic tension by chafing against their circumstances, by the intensifying dazzle of their discontents, something that Kate refused to transmit.

In contrast, Mantel described Diana as a “carrier of myth”: Diana, publicly trapped in the disappointments of her marriage, certainly carried more plot twists than any author had a right to expect.

Unfortunately for her, the final one was her shockingly premature death.

Set against this artistic conception of “character” — distinctive qualities or flaws that, one way or another, deliver drama — is the societal judgement “of good character,” meaning someone who is broadly reliable and respected in relation to their behaviour to others.

In recent years, the electorate, in line with Neil Postman’s warning in his 1985 book, Amusing Ourselves To Death, has proved increasingly ready to select the former over the latter, even to the marked detriment of our civic health.

The former prime minister Boris Johnson instinctively understood it as his job not to deliver the detail of workable policy but to satisfy the public’s appetite for story:

“People live by narrative,” he once told UnHerd’s Tom McTague.

In the US, Donald Trump — that relentless generator of low mockery and high fury — is now running for a second term as president, after his first one ended in his supporters storming the Capitol building.

Men are often permitted to survive the frantic generation of drama: it is everyone around them who suffers.

Yet women — in art and life — have a greater tendency to be destroyed by it.

There is no strutting female equivalent of the male “hellraiser,” but rather a woman who, soaked in the crocodile tears of the tabloids, is tragically “causing concern” among friends.

Art and its audiences have always relished the restless struggle and disintegration of female characters who are, or become, unmoored from the harbour of marriage and children.

Flaubert’s Emma Bovary — her imagination inflamed by reading novels — is bored with her marriage and disenchanted with motherhood.

She seeks solace in affairs and excessive spending, the consequences of which hasten her suicide.

Zola’s Nana, a courtesan who ruthlessly captivates Parisian society, has her beguiling face eaten away by smallpox.

Janis Joplin and Amy Winehouse, immolated on their blazing talent, are hung posthumously high in the musical hall of fame, next to Sylvia Plath in the poetry section and Marilyn Monroe in cinema.

In Jean Rhys’s Good Morning, Midnight, a middle-aged English woman called Sasha Jansen, mourning an unhappy marriage and a dead child, finds herself in Paris, a vulnerable drifter seeking solace from stray men.

Rhys herself, who died at 88 after a precarious but surprisingly long life, had much in common with her literary creations.

As the writer and editor Diana Athill crisply put it:

“Jean was absolutely incapable of living, life was just hopelessly beyond her.

When she was young, she floated from man to man in a hopeless way… by the time she was old, she floated from kind woman to kind woman.”

In Rhys’s latter years — hard-drinking, irascible and impoverished — Athill and a small group of female friends formed what they called “The Jean Rhys Committee,” which met regularly to ask “what should we do next?”

Rhys’s claim to such loyalty, I suppose, was the weight of her literary talent, her ability to exert an odd kind of fascination, and the fortunate soft-heartedness of her friends.

The dramatic collided with the dutiful and was kept alive by it.

From what I can see, the Princess of Wales exists at the opposite end of the feminine spectrum from Jean Rhys.

Pinned firmly in place by her royal obligations, her wealth, her marriage, and three children, she belongs to the realm of the respectable and dutiful rather than the erratic and dramatic.

She is not a “character” in the artistic sense, nor does she desire to be, but both a survivor and upholder of an institution:

Hers is the territory of the prompt thank-you note, the kept promise, the commitment to public service, the uncomplicated pleasure in children, the stoic endurance of difficult times in the hope that better ones will come along soon.

The public senses an emotional solidity in her, and it is partly why she is held in broad esteem.

In this age of insistent self-definition, duty to others might be an unfashionable concept, but it is nonetheless one that keeps families and institutions from chaos and collapse.

With the advent of the internet, however, anyone with a keyboard can become a form of author, with the freedom to insert a toxic form of drama into real-life situations.

What was extraordinary, during the Princess of Wales’s recent health problems, is how speedily and carelessly such speculations overrode the bounds of decency.

It was already known that she had undergone major abdominal surgery and was taking time to recover.

And yet — egged on by the participation of silly celebrities and malicious US comedians — conspiracy theories about cosmetic surgery and affairs and nervous breakdowns spread like knotweed.

According to social-media researchers, these were also vigorously introduced and amplified by fake accounts set up on Twitter and TikTok, some associated with Russia-linked disinformation eager to spread the termites of mistrust and doubt in Western institutions.

Only the Princess of Wales’s revelation of cancer, which carries a testing drama all its own, served to shut up the majority of them.

Unlike these callous gossips, Mantel recognised her own complicity in dehumanising royalty.

Upon encountering the late Queen, the novelist said: “I passed my eyes over her as a cannibal views his dinner, my gaze sharp enough to pick the meat off her bones.”

The Queen looked back at her, she said, briefly hurt. Mantel warned of the way in which “cheerful curiosity can easily become cruelty” precisely as it has done in recent weeks.

Her talk concluded with a prescient instruction for those who comprehend monarchy mainly as a source of entertainment: “I’m asking us to back off and not be brutes.”

In the midst of treatment and recovery, the most hitherto stable of royal women could be forgiven a keen sense of injustice:

Her job description, it seems, must now include the ability to weather the online public’s fits of brutish mania for drama.

With its contempt for duty, and its savage appetite for story, it is hungry to chew up far more than just the Princess of Wales.

NOTE: Additional photos have been included in this article.

#Princess of Wales#Catherine Princess of Wales#Catherine Middleton#Kate Middleton#British Royal Family#cancer#chemotherapy#preventative chemotherapy#disinformation#misinformation#fake news#trolls#bots#click farms#targeted attack#malicious gossips

93 notes

·

View notes

Text

Favorite books with autumn vibes

Contemporary

All Souls Trilogy by Deborah Harkness

At the Edge of the Orchard by Tracy Chevalier

For the Wolf by Hannah Witten

The Ghost Bride by Yangsze Choo

The Graveyard Book by Neil Gaiman

The Historian by Elizabeth Kostova

The Invisible Life of Addie Larue by V.E. Schwab

The Night Circus by Erin Morgenstern

Ninth House by Leigh Bardugo

The Ocean at the End of the Lane by Neil Gaiman

The Once and Future Witches by Alix Harrow

The Only Good Indians by Stephen Graham Jones

Piranesi by Susanna Clarke

Red at the Bone by Jaqueline Woodson

The Scholomance Trilogy by Naomi Novik

The Secret History by Donna Tartt

The Shadow of the Wind by Carlos Luis Zafron

Under the Whispering Door by TJ Klune

Uprooted by Naomi Novik

Wolf Hall by Hilary Mantel

Classics

And Then There Were None by Agatha Christie

Anne of Green Gables by L.M. Montgomery

The Bloody Chamber by Angela Carter

Daddy Long Legs by Jean Webster

Dracula by Bram Stoker

Frankenstein by Mary Shelley

The Hound of the Baskervilles by Arthur Conan Doyle

Jane Eyre by Charlotte Bronte

Northanger Abbey by Jane Austen

Rebecca by Daphne du Maurier

The Turn of the Screw by Henry James

We Have Always Lived in the Castle by Shirley Jackson

The Woman in Black by Susan Hill

Graphic Novels

My Favorite Thing is Monsters by Emil Ferris

The Sandman Vol. I: Preludes and Nocturnes by Neil Gaiman

Through the Woods by Emily Carroll

Always looking for more! Tell me yours!

178 notes

·

View notes

Text

I mentioned in a little comments conversation with @bookhobbit that over the last year I've worked really hard on changing my relationship with my body (which had become totally medicalised after I developed long-term health problems). I said I'd write something about how I've gone about this, so here it is - a long post with brief medical details under the cut. This is not a post about what I think anyone else could or should do - I don't know what would be possible or helpful for anyone else. It's just a description of what I've been doing in response to a challenging aspect of my life.

Some background. I have several long-term health conditions, the most problematic being an autoimmune condition that causes muscle damage. If you can't get it into remission then it becomes a progressive disease, causing damage to the muscles that are needed to walk and lift things, and to control swallowing and breathing. So yeah, you want to get it into remission. I'm lucky in that I've responded to the immunosuppressants and the condition stays in remission or near enough as long as I take the meds, so my muscles are not getting massively damaged at the moment. But the meds have wrecked my stomach lining and intermittently do bad things to my liver, and the multiple muscle biopsies I needed to get a diagnosis have done other damage, and because of the meds, even in phases when the autoimmune condition is in remission, I still regularly have unpleasant symptoms. And when I take a break from the meds, the muscle damage starts again.

Relationship to my body. Since all this started a few years ago my life has felt like an endless stream of MRI scans, medications, biopsies, blood tests, injections, and rehab. And my body has come to feel like a collection of broken parts, just a heap of systems that don't work and feel bad and are frightening and exhausting. About a year ago I recognised that my relationship to my body had been completely changed by all this. I had come to see my body, to experience my body, as just a collection of medical problems and nothing more. And of course, that was being reinforced by the regular conversations I have to have with doctors about it all—dispassionate, diagnostic conversations about whatever bits of my body are currently failing to perform normally. I had come to experience my body as a bag of broken medical objects—and that is absolutely not the relationship I want to have with it. So, I decided to do what I could to change that relationship.

How I went about changing my relationship with my body. What I can’t change is the fact that I have long-term health conditions and that means symptoms and treatments to varying degrees for the rest of my life. I can’t change the fact that there are parts of my body, whole systems, that just don’t work well. But what I had to recognise is that my body is not merely that; I am not merely that. And knowing intellectually that I am more than a collection of symptoms was not enough. I needed to retrain my attentional habits to notice more than just medical stuff. And I needed to start treating my body as more than just medical stuff.

I’m lucky that I have some personal resources that I could lean on to do this:

I’m a (non-theist) pagan and I’m used to using ritual to turn towards painful experiences and explore them and set specific intentions about them

I have a decades-long history of mindfulness practice

I am a determined, obstinate creature!

This is what I did.

1. I made a ritual about the issue. I cast a circle and lined the circle with objects and pictures that represented my imaginary gang (Patti Smith, Kate Bush, Natasha Khan, Mary Oliver, and Hilary Mantel, in case you’re wondering!) I sat in the middle of the circle and told the ladies the story of what had happened—of how ill I was and how medicalised my body had become and how sad and lost and frightened I felt about it all. I stated my intention to the gang: to reclaim my physical, animal self—to relearn how to experience my physical self as more than a selection of medical problems; to treat my physical self as more than a medical problem. I listed some of the ways I could view and experience my body that were not about it being a broken medical object. I made a commitment to myself and to the gang to weave this practice into my daily life, and then to show that I was serious about the commitment, I acted on it in the ritual by putting on lots of temporary tattoos and jewellery—treating my body as something to be adorned and celebrated rather than just medicalised. I finished by having a little feast, thanking the gang, and closing the circle.

For me, a ritual like this acts as a clarifying lens and also as a crucible in which to form new behavioural habits. And I use the memory of the ritual as a support when I’m trying to act on my commitment day in, day out, and maybe struggling.

2. I put myself on an attention training programme. By that I mean that following the ritual, every time I noticed that I was focussed/fixated/ruminating on a symptom or some other aspect of my body-as-a-medical-object I would ask myself two questions:

Is there any reason why continuing to focus narrowly on this medical issue/body part right now is going to be helpful? (It was rarely helpful). I would then wish the body part well and would shift to the second question:

In addition to this medical issue/struggling body part, what else is my body right now? I’d make myself broaden out my attention to include the whole of my body (including but not limited to the body part or symptom I’d been fixating on), to be able to respond to this question based on direct, sensory experience: This is a body that’s wearing yellow socks with puffins on them. This is a body that’s feeling the breeze coming in through that open window and enjoying the sensation. This is a body that smells of pears from my favourite shower gel. This is a body that’s tired. This is a body that’s feeling hungry. This is a body that feels restless. This is a body that's listening to Chaka Khan and has an urge to dance.

Over the last year I have intentionally, thousands of times, acknowledged my body’s struggles and symptoms and then I've widened the field of my attention to notice what else my body is, what else it can experience, what else it means to me, what it is as a whole. I have trained myself, one tiny practice at a time, to reconnect with a wider, fatter, richer sense of what my body is, of who I am as an embodied creature. Of course, my attention is still pulled to pain and nausea and symptom-focussed worry etc. but I don’t get caught up in those things for as long as I used to, and I notice the non-medical stuff quicker and more frequently than I did.

3. As per the commitment I made in the ritual, I have begun (again) to treat my body as more than just a collection of medical problems that need treatment. Specifically, I have worked on changing my role/behaviour towards my body from that of merely nurse/physio. For me this has included (at different times) adorning it with temporary tattoos that make me smile, feeding it foods it really likes, wearing perfume, wearing clothes in colours I love, singing round the house, massaging my hands and feet, seeking more cuddles etc. from my husband, dancing when I feel able to, and really importantly to me, starting to have massages every six weeks or so that are utterly non-medical in nature. I still have to give myself injections and book blood tests and make myself have naps etc. but that’s not all I do in relation to my body now.

Given that my health conditions are going to be around for the rest of my life, I think these practices will also need to be around for the rest of my life, or at least for as long as I find them helpful.

This is already very long so I’m going to stop here, but I’m very happy to answer any questions about any of it - if anyone gets to the end and it's of interest :-)

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

2023 bookpost 🥳🥳🥳

43 books read this year! about 2/3rds of last year's number, but i fell off pace in summer and for the last two months and never actually have a target or care about my pace anyways, so 43 is a good solid number imho. as last year, full list with light commentary below, recs are bolded:

JANUARY

Neuromancer by William Gibson

The Browns of California: The Family Dynasty that Transformed a State and Shaped a Nation by Miriam Pawel (i am punished for my desire to learn more about the two governors brown's effects on the state of california with: family hagiography. should have known tbh)

Between Two Fires by Christopher Buehlman (SOOOOOO GOOD. apocalyptic/religious horror in 1350's france during the black plauge. for fans of the terror, and fans of people who are in love but for whom the love won't alwayshelp!)

The Mirror and the Light by Hilary Mantel (hilary ilu u were one of the greatest novelists of the past hundred years it was an honor to be alive at the same time as you. this could have been 200 pages shorter. ilu tho)

Did Ye Hear Mammy Died? by Seamas O’Reilly (short, sweet childhood memoir of the irish writer/comedian who, famously, tweeted that story about meeting the president of ireland on ketamine.)

FEBRUARY

Either/Or by Elif Bautman (girls can i tell you. i didn't realize this was a sequel until like 100 pages into the book. that was on me.)

Two Doctors Gorski by Isaac Fellman (ah mr fellman. lol)

The Swimmers by Julie Otsuka (really cool piece of fiction, first half told from the collective viewpoint of a group of regulars at a public swimming pool, second half about the one specific swimmer who's losing her independence to dementia. short, packs a punch)

Rebecca by Daphne du Maurier (UNDEFEATED!)

One Man’s Terrorist: a Political History of the IRA by Peter Finn

Nightcrawlers by Leila Mottley (love to see local 22yos succeed wildly. does NOT mean this book was good god bless)

MARCH

The Memory Police by Yoko Ogawa

The Passenger by Cormac McCarthy

Stella Maris by Cormac McCarthy (to be clear, if you are not a cormac mccarthy fan, these books will not make you his fan. they are very much about this man's incredible hopelessness regarding a world that has invented and used the atomic bomb. what can be redeemed, etc etc. i loved them, despite a major part of the plot being consensual sibling incest, they were beautiful and phenomenal, they were not light reading)

APRIL

A Smile in his Lifetime by Joseph Hansen

Glory by NoViolet Bulawayo (cannot recommend the audiobook highly enough. emma read the paper copy to catch up to where i was in the audiobook so we could listen together on a car trip, and she agreesTM that the audiobook is the way to go)

MAY

Barbarian Days by William Finnegan

The Dark Lord of Derkholm by Dianna Wynne Jones

JUNE

We Don’t Know Ourselves by Fintan O’Toole (really really really cool nonfiction about ireland since the 1950s, part autobiography, more parts cultural history of a very quickly changing nation. fascinating to read this within 12 months of finn's one man's terrorist, which was a very leftist history of the IRA, and keefe's say nothing, which was an only very slightly leftist history of the IRA that was most interested in like, how compelling the history is (not a drag on it). o'toole not as big on the IRA as the other two! understandable!)

JULY

The Binding by Bridget Collins

The War That Killed Achilles by Caroline Alexander (for all fans of the history of the story of the illiad!!! short and passionate!)

Flux by Jinwoo Chong (solid new debut scifi - who thought it could still happen!)

I’m Glad My Mom Died by Jeanette McCurdy

The Witch King by Martha Wells (this book sucked ass!!! have mentioned this several times already this year!!!)

An Oral History of the New York Commune, 2052–2072 by Eman Abdelhadi and M. E. O'Brien (some things about this book were fun, many were infuriating, absolute worst had to be the insistence that in the future: therapy would solve even more problems that it does today :))

The Last Samurai by Helen DeWitt (see my beautiful wife's post on the subject)

Stay True by Hua Hsu (beautiful, deserves the pulitzer, not 100% my thing but still very good)

AUGUST

Demon Copperhead by Barbara Kingsolver (the voice was hard to get used to for the first 50 pages, but i ended up really liking this tbh. i've never read copperfield, so not sure if that improved the experience)

Crying in H Mart by Michelle Zauner

The Boys by Katie Hafner (a mistake to read this, but at least the twist was funny! there wasn't anything else in the book, but only a partial waste of time at the end)

Tomorrow and Tomorrow and Tomorrow by Gabrielle Zevin (finally read this, which has truly polarized my extended social circle, but i ended up liking it. i didn't always get what it was doing 100% of the time, and didn't so much feel compelled to find out, but i tore through it and will always be a sucker for a story about that doesn't fix you but does keep you alive. can see both sides of this debate)

American Overdose: The Opioid Tragedy in Three Acts by Chris McGreal (we have to kill every sackler. solid history of the epidemic. EVERY sackler.)

SEPTEMBER

The Season by Kristen Richardson (half-baked history of the debutante social ritual. but, not like there's many other histories of the subject!)

All the Horses of Iceland by Sarah Tolmie

Big Swiss by Jen Beagin (funny, contained extensive dirtbag lesbian behaviors, but lacked some heft at the end)

In Memoriam by Alice Winn (do you s2b2? do you want some solid, tome-like origfic? do you want all of those things and also siegfried sassoon rpf? well great news!)

Now We Shall Be Entirely Free by Andrew Miller (pleaseeeeeee tell me if you have read this or do read this it was SOOOOOO GOOD and i had NEVER heard of this guy before!!! fantastically written prose, everything builds with infinite dread to a single horrible punchline, i am still wowed thinking about it)

The Trees by Percival Everett (haha hey wanna get fucked up. dark dark dark comedy)

OCTOBER

Flowers from the Storm by Laura Kinsale (really enjoyable if slightly overlong romance novel that i got off a rec list for historical romances with disabled love interests. does a really good interesting job of giving the love interest full breadth and agency despite severe processing impairment following a stroke)

Mobility by Linda Kiesling

The Rachel Incident by Rachel O’Donahughe

NOVEMBER

NO BOOK NOVEMBER MFS

DECEMBER

Not Even the Dead by Juan Gómez Bárcena (would also like to know if anyone else has read this so we can try and figure out what the fuck was going on right at the end!! also the fact that this is primarily about mexican history, written by a spaniard, with the specter of the US very prominent in the book is like. hm i would love to be able to read some mexican press reviews of this lol)

When Crack Was King: A People's History of a Misunderstood Era by Donovan X. Ramsey (picked this up following the opioid book, which discussed but didn't go deep on how the country's reaction to the opioid epidemic was so vastly different from the crack epidemic. put a lot of stuff into context lmao.)

WAIT AT SOME POINT THIS YEAR I REREAD RUMO AND HIS MIRACULOUS ADVENTURES BY WALTER MOERS. I DON'T KNOW WHEN. DIDN'T WRITE IT DOWN. BUT I DID REREAD IT. 44 BOOKS. shout out to mr. moers for writing some extremely fucking creepy books for teenagers <3

okay i was gonna do more about like general trends and vibes of this year's books, also about the four books i am still reading rn lol, but i have been typing for soooooooooooo long so i'm just gonna reblog with more thots in the morning. stay prepared everyone

24 notes

·

View notes

Note

Have you seen the guests for Camillas book reading festival? It includes the woman Hilary mantel who called Kate a plastic princess that is only good for having kids and another man is on there who also criticised Kate heavily…

Yeah, I actually like Hilary Mantel and you can read the article about her calling Kate plastic here. It was taken out of context, but she meant that Kate is like a more refined Marie Antoinette, people only care about her clothes and the children she has instead of her words and thoughts. I think she said she felt bad for Kate in the same article. It's more intelligent than what was reported:

Kate seems to have been selected for her role of princess because she was irreproachable: as painfully thin as anyone could wish, without quirks, without oddities, without the risk of the emergence of character. She appears precision-made, machine-made, so different from Diana whose human awkwardness and emotional incontinence showed in her every gesture. Diana was capable of transforming herself from galumphing schoolgirl to ice queen, from wraith to Amazon. Kate seems capable of going from perfect bride to perfect mother, with no messy deviation

Hilary Mantel was (she died last year) very critical of the monarchy so it is interesting that she was part of Camilla's bookish events, but she wrote a lot about royal history, famously the court of Henry VIII. She also said about Kate: "We don’t cut off the heads of royal ladies these days, but we do sacrifice them" long before anyone was having a discussion about how badly royal women are treated and she stuck up for Meghan a lot and said Britain lost something when she left. Honestly, for the reason, I like her and will miss her feminist critiques of the royal family

41 notes

·

View notes

Text

Novel Syllabus 2024

This coming year I think I'm going to be on here more often than I am on twitter or elsewhere, and as part of that, I'm going to start documenting the process of writing my novel more actively. I want to return to/resurrect the momentum and energy I had while writing the first draft and be more intentional about setting aside time to work, even when it's difficult. Below are my writing goals for the coming year as well as my reading list of texts for inspiration, genre/background research, comps, etc. Would welcome any suggestions of texts (any genre/discipline) pertaining to Antigone, death & resurrection, Welsh and Cornish myth and folklore, ecology & environmental crisis, and the Gothic.

Writing Goals

Reach 50k words in draft 2 overall

Finish a draft of Anna's timeline

Finish a draft of Jo's timeline

Polish & submit an excerpt for the Center for Fiction Prize

Reading

* = reread

Sci-Fi, Fantasy, & The Apocalyptic

The Memory Theater (Karin Tidbeck)

Who Fears Death (Nnedi Okorafor)

Urth of The New Sun (Gene Wolfe)

Slow River (Nicola Griffith)

Dream Snake (Vonda McIntyre)

Black Leopard, Red Wolf (Marlon James)

Notes from the Burning Age (Claire North)

Invisible Cities (Italo Calvino)*

Frankenstein (Mary Shelley)*

The Last Man (Mary Shelley)

The Drowned World (J.G. Ballard)

Strange Beasts of China (Yan Ge, trans. by Jeremy Tiang)

City of Saints and Madmen (Jeff VanderMeer)

Freshwater (Akweke Emezi)

The Glass Hotel (Emily St. John Mandel)

Pattern Master (Octavia Butler)

Sleep Donation (Karen Russell)

How High We Go in the Dark (Sequoia Nagamatsu)

The Magician's Nephew (C.S. Lewis)*

The Golden Compass (Phillip Pullman)*

The Green Witch (Susan Cooper)

The Tombs of Atuan (Ursula K. Le Guin)

Black Sun (Rebecca Roanhorse)

Gideon the Ninth (Tamsyn Muir)

Lives of the Monster Dogs (Kirsten Bakis)

Brian Evenson

Sofia Samatar

Connie Willis

Samuel Delaney

Jo Walton

Tanith Lee

Retellings

A Wild Swan (Michael Cunningham)

Til We Have Faces (C.S. Lewis)

Gingerbread (Helen Oyeyemi)

Circe (Madeline Miller)

The Owl Service (Alan Garner)

Literary Myth-Making, Mystery, and the Gothic

Nights at the Circus (Angela Carter)

Frenchman's Creek (Daphne Du Maurier)

Possession (A.S. Byatt)*

The Game (A.S. Byatt)*

The Essex Serpent (Sarah Perry)

Wuthering Heights (Emily Brontë)

The Secret History (Donna Tartt)*

The Wild Hunt (Emma Seckel)

King Nyx (Kirsten Bakis)

The Name of the Rose (Umberto Eco)

The Lottery and Other Stories (Shirley Jackson)

Beloved (Toni Morrison)

The Night Land (William Hope Hodgson)

Interview with a Vampire (Anne Rice)*

Sexing the Cherry (Jeanette Winterson)*

Night Side of the River (Jeanette Winterson)

Bad Heroines (Emily Danforth)

All the Murmuring Bones (A.G. Slatter)

The Path of Thorns (A.G. Slatter)

Gormenghast (Mervyn Peake)

Prose Work, Perspective, and Stream of Consciousness

The Chandelier (Clarice Lispector)

The Waves (Virginia Woolf)*

The Years (Virginia Woolf)

The Intimate Historical Epic / Court Intrigues

Wolf Hall (Hilary Mantel)*

Menewood (Nicola Griffith)

Dark Earth (Rebecca Stott)

A Place of Greater Safety (Hilary Mantel)

Research

The Mabinogion (trans. Sioned Davies)

Le Morte D'Arthur (Thomas Malory)

The Collected Brothers Grimm (Phillip Pullman)

Angela Carter's Collected Fairytales

Mythology (Edith Hamilton)

Underland (Robert Macfarlane)

The Wild Places (Robert Macfarlane)

Wildwood (Roger Deakin)

Vanishing Cornwall (Daphne Du Maurier)

Lonely Planet: Guide to Devon & Cornwall

A Traveler's Guide to the End of the World (David Gessner)

The Lost Boys of Montauk (Amanda M. Fairbanks)

A Cyborg Manifesto (Donna J. Harraway)

A Treasury of British Folklore (Dee Dee Chainey)*

The First Last Man: Mary Shelley and the Postapocalyptic Imagination (Eileen M. Hunt)

Antigone's Claim (Judith Butler)

Theories of Desire: Antigone Again (Judith Butler)

Ecology of Fear (Mike Davis)

7 notes

·

View notes