#Filioque

Text

The Orthodox tradition firmly teaches two things about the Holy Spirit. First, the Spirit is a person. He is not just a 'divine blast' [. . .], not just an insentient force, but one of the three eternal persons of the Trinity; and so, for all His seeming elusiveness, we can and do enter into a personal 'I-Thou' relationship with Him.

Secondly, the Spirit, as the third member of the Holy Triad, is coequal and coeternal with the other two; He is not merely a function dependent upon them or an intermediary that they employ. One of the chief reasons why the Orthodox Church rejects the Latin addition of the filioque to the Creed, as also the Western teaching about the 'double procession' of the Spirit which lies behind this addition, is precisely our fear that such teaching might lead men to depersonalize and subordinate the Holy Spirit.

The coeternity and coequality of the Spirit is a recurrent theme in the Orthodox hymns for the Feast of Pentecost:

The Holy Spirit for ever was, and is, and shall be;

He has neither beginning nor ending,

But He is always joined and numbered with the Father and the Son:

Life and Giver of Life,

Light and Bestower of Light,

Love itself and Source of Love:

Through Him the Father is made known,

Through Him the Son is glorified and revealed to all.

One is the power, one is the structure,

One is the worship of the Holy Trinity

-- Kallistos Ware, The Orthodox Way

9 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Today we also celebrate the Venerable Mark the Eugenicus, Archbishop of Ephesus and Pillar of Orthodoxy. Saint Mark was born in Constantinople in 1392 AD where he grew up in Christian piety. Many members of his family were clergy, and even hierarchs, and thus Mark was surrounded by the Orthodox faith from a young age. During this time, the Ottoman Empire was drawing closer to Constantinople, and out of fear of attack, the Byzantine Emperor John Paleologos agreed to make ties with the Roman Catholic Church in order to strengthen their armies and defeat the Ottomans. This union, however, required various theological compromises from the Orthodox in order to reunite the Eastern and Western Churches, especially the introduction of the Filioque clause into the Nicean Creed. Saint Mark, being elevated to the See of Ephesus, stood up for the Orthodox faith and was the only Eastern bishop to refuse to sign the decree of this council which agreed to this compromise. When the members of his own delegation attempted to persuade him to sign the document, he boldly stated, “there can be no compromise in matters of the Orthodox Faith.” During this council, he also refuted the doctrine of purgatory and as well as the primacy of the Roman Pope. When he returned to Ephesus, he urged his flock to beware of the snares of the West and to defend the Orthodox faith. Because of his steadfastness in the faith, he has been appropriately given the title “Pillar of Orthodoxy” along with Saint Photius the Great and Saint Gregory Palamas. The Great and Venerable Mark reposed peacefully in 1444. May he intercede for us always + #saint #mark #archbishop #ephesus #asiaminor #filioque #heresy #romancatholic #easternorthodox #catholic #council #ottoman #ottomanempire #trinity #pope #orthodoxy #truefaith #faith #orthodox #saintoftheday (at Ephesus, Turkey) https://www.instagram.com/p/CnklKd0h4Ri/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

#saint#mark#archbishop#ephesus#asiaminor#filioque#heresy#romancatholic#easternorthodox#catholic#council#ottoman#ottomanempire#trinity#pope#orthodoxy#truefaith#faith#orthodox#saintoftheday

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

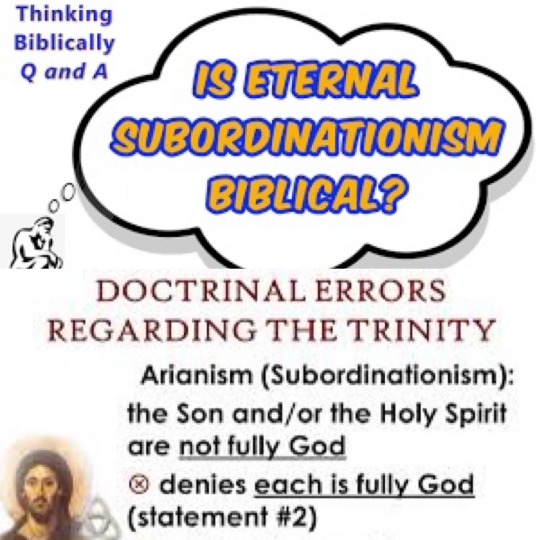

The Error of Subordinationism

By Biblical Researcher Eli Kittim 🎓

Ontological Subordinationism

The theological literature defines Subordinationism as comprising hierarchical rankings amongst the persons of the Trinity, thus signifying an ontological subordination of both the Son and the Spirit to the Father. The word ontological refers to “being.” Although some of the ante-Nicene fathers supported subordinationism, this doctrine was eventually condemned as heretical by the Post-Nicene fathers:

Athanasius opposed subordinationism, and

was highly hostile to hierarchical rankings

of the divine persons. It was also opposed

by Augustine. Subordinationism was

condemned in the 6th century along with

other doctrines taught by Origen.

Epiphanus writing against Origen attacked

his views of subordinationism. — wiki

Calvin also opposed subordinationism:

In his Institutes of the Christian Religion,

book 1, chapter 13 Calvin attacks those in

the Reformation family who while they

confess ‘that there are three [divine]

persons’ speak of the Father as ‘the

essence giver’ as if he were ‘truly and

properly the sole God’. This he says,

‘definitely cast[s] the Son down from his

rank.’ This is because it implies that the

Father is God in a way the Son is not.

Modern scholars are agreed that this was a

sixteenth century form of what today is

called, ‘subordinationism’. Richard Muller

says Calvin recognised that what his

opponents were teaching ‘amounted to a

radical subordination of the second and

third persons, with the result that the Father

alone is truly God.’ Ellis adds that this

teaching also implied tritheism, three

separate Gods. — wiki

The Eastern Orthodox position is yet another form of subordinationism that has asserted the Monarchy of the Father to this day:

According to the Eastern Orthodox view, the

Son is derived from the Father who alone is

without cause or origin. — wiki

The Catholic Church, however, is overtly antithetical to the subordinationism doctrine:

Catholic theologian John Hardon wrote that

subordinationism ‘denies that the second

and third persons are consubstantial with

the Father. Therefore it denies their true

divinity.’ — wiki

In theology proper, unlike ontological subordination, there is also the doctrine of “economic subordination” in which the Son and the Holy Spirit play subordinate roles in their functions, even though they may be ontologically equal to the Father. New Calvinists have been advancing this theory of late:

While contemporary Evangelicals believe

the historically agreed fundamentals of the

Christian faith, including the Trinity, among

the New Calvinist formula, the Trinity is one

God in three equal persons, among whom

there is ‘economic subordination’ (as, for

example, when the Son obeys the Father).

— wiki

According to the Oxford Encyclopedia, the doctrine of Subordinationism makes the Son inferior to the Father, and the Holy Spirit inferior to the Son. It reads thusly:

Subordinationism means to consider Christ,

as Son of God, as inferior to the Father.

This tendency was strong in the 2nd- and

3rd-century theology. It is evident in

theologians like Justin Martyr, Tertullian,

Origen, Novatian, and Irenaeus. Irenaeus,

for example, commenting on Christ's

statement, ‘the Father is greater than I’

(John 14:28), has no difficulty in

considering Christ as inferior to the Father.

… When Origen enlarged the conception of

the Trinity to include the Holy Spirit, he

explained the Son as inferior to the Father

and the Holy Spirit as inferior to the Son.

Subordination is based on statements

which Jesus made, such as (a) that ‘the

Father is greater than I’ (John 14:28); (b)

that, with respect to when the day of

Judgment will be, ‘of that day or hour no

one knows, not even the angels in heaven,

nor the Son, but the Father alone’ (Mark

13:32), and that He spoke of God as

somebody else (Mark 11:18). — wiki

However, Jesus’ statements are made from within the confines of his human condition, and thus they don’t pertain to his eternal status. As the Son of Man, namely, as a finite, limited human being, in comparison with the eternal Father, Jesus is obviously incapable of knowing all things. So Jesus’ statements must not be taken out of context and used to support the idea that he’s ontologically an inferior God. Micah 5.2 would certainly challenge that notion when it reveals that the messiah is actually uncreated: “His times of coming forth are from long ago, From the days of eternity.” Subordinationism ultimately leads to Arianism, the notion that the Son was created by the Father, and is not thus God:

Arius, therefore, held that the Son was

divine by grace and not by nature, and that

He was created by the Father, though in a

creation outside time. In response, the

Nicene Creed, particularly as revised by the

second ecumenical council in

Constantinople I in 381, by affirming the co-

equality of the Three Persons of the Trinity,

condemned subordinationism. — wiki

According to The Westminster Handbook to Patristic Theology, Subordinationism sees “the Son” and “the Spirit of God” as lesser deities, especially as demi-gods, or inferior gods:

Subordinationism. The term is a common

retrospective concept used to denote

theologians of the early church who

affirmed the divinity of the Son or Spirit of

God, but conceived it somehow as a lesser

form of divinity than that of the Father.

— wiki

Subordinationism is reminiscent of Gnosticism in which there’s a supreme God as well as lesser divinities. In Subordinationism, the Son is viewed as an inferior god, or a lesser god. However, as will be shown, Jesus is not a subordinate god in relation to God the Father. Some theologians argue that although the three persons of the Godhead are coequal, coeternal, and consubstantial ontologically, the Son and the Spirit are nevertheless subordinate in terms of economy, that is, in terms of their functions and roles. This notion of ranking or subordination within the trinity is supposedly supported by scripture when it says that the Father “sent” the Son (Jn 6.57), or that the Father and the Son “send” the Spirit (Jn 15.26), or that the spirit will “speak only what he hears” (Jn 16.13).

But this still implies a greater versus a lesser god, which makes the Trinity theologically indefensible! Not to mention that these verses are taken out of context. The temporal operations of the Son and the Spirit are scripturally depicted in anthropomorphic terms, ascribing human characteristics to divine operations and energies so that they can be better understood. As, for example, when scripture says that God changed his mind, or that he repented. And as regards Jesus’ connection to the God of the Hebrew Bible, appropriate New Testament language must be used so as to preclude a theological deviation from the monotheistic God of the Old Testament. Nevertheless, scripture does tell us categorically and unequivocally who Jesus is. Revelation 1.8 tells us that the Son is the Almighty! Who, then, ranks above him? Moreover, Jesus is Yahweh (the Lord) in the New Testament. Proverbs 8.28-30, John 1.3 and Hebrews 1.2 all indicate that Jesus is the creator. John 1.3 declares:

All things came into being through him

[Jesus], and without him not one thing

came into being.

Acts 4.12 reminds us of Jesus’ preeminent position within the Godhead:

there is salvation in no one else; for

there is no other name under heaven that

has been given among mankind by which

we must be saved.

In my view, subordinationism leads to tritheism!

The Eternal Subordination of the Son

The doctrine that the Son is eternally created by God the Father smacks of Arianism, as if his divinity is mediated to him by God the Father, implying that the Son doesn’t legitimately possess divinity in and of himself. It suggests that the Son and the Father were not always God in the same way, and that there was a time when the Son did not exist. Accordingly, only the Father was in the beginning. In other words, the Son is not eternal. This view holds that the Son is God only because Godhood is bestowed on him as a gift from the Father. To phrase it differently, the Son is God by grace and not by nature. Today, among the theologians who hold to Subordinationism are Bruce A. Ware, Wayne A. Grudem, and John W. Kleinig. But this doctrine contradicts John 1.1:

In the beginning was the Word, and the

Word was with God, and God was the word.

We must always remember that all of Jesus’ words must be understood within the context of the human condition. That is to say, Jesus is speaking of his human nature, as a human being, not as eternal God. He is a creature, a man, a finite being, located in time and space, and in that sense he is obviously in a subordinate relationship to the Father who remains eternal and is everywhere. So when Jesus employs the language of grace——specifying what the Father has “given” him——he is referring to what the eternal Father has done for the mortal Son of Man, namely, to give him authority, exaltation, worship, and glory (cf. Daniel 7.13-14). This apparent inequality between the Son and the Father is, strictly speaking, limited to Jesus’ humanity, a humanity which will then in turn redeem human nature and glorify his elect. It is not referring to Jesus’ ontological relationship with the Father, which is one of equality. And since he is appealing particularly to the monotheistic God of the old testament, which the Jews understood as a singular deity, Jesus is careful to use the language of grace in order to appease the Jews who would otherwise take exception to an incarnate God. But scripture is quite adamant about the fact that Jesus is both man and God! John 1.14 puts it thusly:

And the Word became flesh, and dwelt

among us.

Colossians 2.9 reveals that the Son is fully God, and that the fullness of the godhead (πᾶν τὸ πλήρωμα τῆς θεότητος) dwells in him bodily:

in him the whole fullness of the godhead

[θεότητος] dwells bodily.

Hebrews 1.3 proclaims that the Son is of the same essence as the Father:

The Son is the radiance of God’s glory and

the exact imprint of his being.

Titus 2.13 calls him “our great God and Savior Jesus Christ.” And in John 1.3 and Hebrews 1.2 Jesus is the creator and the “heir of all things, through whom he [God] also created the worlds.” That is to say, the Son of Man, in his *human nature*——as the mediator and savior of mankind——becomes heir of all things. Not that the Godhood is given to him as a gift or as an inheritance. How can a lesser god or a created being act as the ultimate judge of the universe? John 5.22 reads:

For the Father judgeth no man, but hath

committed all judgment unto the Son.

It doesn’t mean that the Son is given this office as a gift because the Son is God by nature and not by grace! How can God the Father hand over his Sovereignty to God the Son as a gift if Yahweh never yields his glory to another?

I am the LORD [Yahweh]; that is my name! I

will not yield my glory to another.

— Isaiah 42.8

How can an inferior god, a lesser god, or a created god be completely sovereign over the entire universe? In Matthew 28.18, Jesus declares:

All authority in heaven and on earth has

been given to me.

The clincher, the verse that clearly demonstrates the Son’s divine authority is Revelation 1.8. Since we are not waiting for the Father but rather for the Son to arrive, it becomes quite obvious that this is a reference to Jesus Christ:

‘I am the Alpha and the Omega,’ says the

Lord God, ‘who is, and who was, and who is

to come, the Almighty.’

In Daniel 7.14, why was the Son of Man “given authority, glory and sovereign power”? Why did “all nations and peoples of every language worship[ed] him”? If he’s a created being, why do the heavenly host prostrate before the Son in heaven? Partly because he is God, but also because of his deeds on earth. Revelation 5.12 exclaims:

Worthy is the Lamb that was slaughtered to

receive power and wealth and wisdom and

might and honor and glory and blessing!

Not that the Son doesn’t have power, or wealth, or wisdom, or honor, or glory, or blessing. But it’s as if additional exaltation is offered to him because of his achievements as a human being (as the Son of Man)! First Timothy 6.15-16 calls Christ the “only Sovereign” God and that “It is he alone who has immortality and dwells in unapproachable light”:

he who is the blessed and only Sovereign

[μόνος δυνάστης], the King of kings and

Lord of lords. It is he alone who has

immortality [ἀθανασίαν] and dwells in

unapproachable light, whom no one has

ever seen or can see.

Hebrews 1.3 reveals that the Son (not the Father) “upholds the universe by the word of his power.” Colossians 1.17 also says: “He [Christ] is before all things, and in him all things hold together” (cf. Philippians 3.21). What is more, if the Son is subordinate to the Father, then the Father is the source of life, not the Son. Yet John 14.6 says the exact opposite, to wit, that the Son is both “the truth” and “existence” itself:

Jesus said to him, ‘I am the way, and the

truth, and the life.’

Jesus also alludes to himself as Yahweh, using the ontological Divine Name “I AM” from Exodus 3.14:

Jesus said to them, ‘Truly, truly I say to you,

before Abraham was born, I am.’

— John 8.58

In Matthew 28.18, Jesus says that “All authority in heaven and on earth has been given to me” (Ἐδόθη μοι πᾶσα ἐξουσία ἐν οὐρανῷ καὶ ἐπὶ τῆς γῆς·). That means that Jesus has *ALL AUTHORITY*; not just some authority or most authority. So, if the Son possesses all authority, how is he subject to a higher authority? Consequently, there’s no one higher than him! We also know this through Special Revelation❗️

Eternal Sonship vs Incarnational Sonship

In his essay “JOHN 1:14, 18 (et al.),” Edward Andrews writes:

Literal translation philosophy versus

interpretive translation philosophy plays a

role here too. I submit that rendering

monogenēs as “only begotten” is the literal

rendering. In translating the Updated

American Standard Version (UASV), our

primary purpose is to give the Bible readers

what God said by way of his human

authors, not what a translator thinks God

meant in its place.—Truth Matters! Our

primary goal is to be accurate and faithful

to the original text. The meaning of a word

is the responsibility of the interpreter (i.e.,

reader), not the translator.

Therefore, a literal reading of monogené̄s is “only begotten” or “only-born.” However, scholars commonly argue whether the meaning of the Greek word μονογενὴς (monogenēs) is “only begotten” or “unique.” I will discuss that in a moment. Moreover, theologians have devised the doctrine of eternal Sonship, and have viewed this process as an eternal begetting, namely, the eternal begetting of the Son. That is to say, the 2nd person of the Trinity has always been the Son of God throughout all eternity. This is primarily based on the Nicene Creed (325 A.D.) which states: "We believe in one Lord, Jesus Christ, the only Son of God, eternally begotten of the Father, God from God, Light from Light, true God from true God, begotten, not made, of one Being with the Father.” However, the preposition “from” (e.g. God from God, Light from Light, true God from true God) is very problematic. So is the phrase “eternally begotten of the Father.” Both suggest that the the 2nd person is not fully God in his own right but derives his divinity eternally from the Greater God, the Father. So, for example, if the Father were to suddenly cut off the supply lines, for whatever reason, the Son would no longer be God. That’s the implication. Insofar as this language gives priority to the Father as the only true God, it suggests that the Son and Spirit are inferior and that they derive their divinity and existence from the Father. Yet Isaiah 9.6 calls the Messiah “Everlasting Father”!

In his book “Systematic Theology,” Wayne Grudem identifies one particular hermeneutical problem with these types of interpretations, namely, that they try to illustrate the eternal relationships within the Godhead based on scriptural information which only address their relationships in time. Therefore, it is both feasible and conceivable that the Bible uses the terms Father, Son, and Holy Spirit to describe the manner in which the members of the Trinity relate to humanity in space-time. For instance, the numerous references pertaining to the Father “sending” the Son into the world allude to time. Furthermore, the Father-Son-and-Holy-Spirit formula is an “analogy” to the human family and to human relationships, not an exact representation concerning the relationships of the persons within the Trinity. Moreover, the notion that the Son is “eternally begotten” of the Father is dangerously close to Arianism, which maintains that the Son of God didn’t always exist but was rather begotten by God the Father, thus implying that Jesus was not co-eternal with God the Father.

Those who take exception to the concept of eternal Sonship often espouse what is known as the doctrine of the Incarnational Sonship. While affirming the Son’s deity and eternality, this doctrine holds that he was not always the Son of God. Rather, his Sonship began when he was “begotten.” In other words, the Father-Son-and-Spirit formula only describes the manner in which the members of the Trinity relate to humanity in space-time. This means that the second person of the Trinity became the Son of God at some point in history, namely, at His incarnation. There are several nontrinitarian offshoots of this view, which hold that the second person of the Trinity was adopted as the Son of God at his baptism, his resurrection, or his ascension. This view is known as Adoptionism (also called dynamic monarchianism). Since this is a nontrinitarian formula which asserts that Christ was simply a mortal man who was later adopted as the Son of God at some point in human history, it has absolutely nothing to do with the Incarnational Sonship that I’m describing, which recognizes and affirms Christ’s deity and eternality. Advocates of this position view the Sonship of Christ as a title or a function that he historically assumed “in time,” at his incarnation. They do not view the Sonship of Christ as an essential element of “who he is” within the Trinity. The same is true of the Father. According to this view, the first person of the Trinity became the Father at the time of the incarnation.

MacArthur (who has since changed his position) originally denied that Jesus was “always subservient to God, always less than God, always under God.” He claimed that sonship is simply an “analogy.” In like manner, Ergun Caner describes Sonship as “metaphor.” Caner similarly argues that “sonship began in a point of time, not in eternity.” Other notable Christians who have taken exception to the doctrine of eternal Sonship are Albert Barnes, Walter Martin, Finis J. Dake, and Adam Clarke.

The language of Hebrews 1.5 clearly defines the relationship of the Father to the Son as beginning during Christ’s incarnation. That’s precisely why this verse is often used as proof of the Incarnational Sonship, in which the titles of Father and Son begin to be applied during a specific event that takes place at a particular point in time: “ ‘You are my Son; today I have become your Father.’ Or again, ‘I will be his Father, and he will be my Son.’ “ Thus, there seems to be an apparent subordination in the economy of God only insofar as Christ’s human nature is concerned.

Monogenēs

Scholars often argue whether the meaning of the Greek word μονογενὴς (monogenēs) is “only begotten” or “unique.” Given the view of Incarnational Sonship, in which the titles of Father and Son begin to be applied during Christ’s incarnation, the expression “the only begotten God” seemingly means “the only God who has ever been born on earth!” And in that sense it also means “unique,” or “one of its kind.” Otherwise, if we think of the Son begotten eternally of the Father, it implies that he is not God in and of himself but derives his divinity from the Father. Thus, he is not “true God from true God”!

Although the term monogenēs could mean the “only one of its kind,” the literal meaning is “only begotten” or “only born.” Given that the earliest papyri have μονογενης θεος in John 1.18, for example, monogenēs seemingly means “the only God who has ever been born in time,” or the “only-born God” (i.e. only-begotten). Put differently, no other God has ever been born in history. But the primary meaning is “only begotten,” or, literally, “only-born.” However, its meaning is commonly applied to mean "one of a kind,” or “one and only.” We can see the interplay between the two meanings in the book of Hebrews:

The word is used in Hebrews 11:17-19 to

describe Isaac, the son of Abraham.

However, Isaac was not the only-begotten

son of Abraham, but was the chosen,

having special virtue. Thus Isaac was ‘the

only legitimate child’ of Abraham. That is,

Isaac was the only son of Abraham that

God acknowledged as the legitimate son of

the covenant. It does not mean that Isaac

was not literally ‘begotten’ of Abraham, for

he indeed was, but that he alone was

acknowledged as the son that God had

promised. — wiki

Nevertheless, excerpts from Classical Greek literature, as well as from Josephus, the Nicene creed, Clement of Rome, and the New Testament suggest that the meaning of monogenēs is “only-born”:

Only-born

Herodotus [Histories] 2.79.3 ‘Maneros was

the only-born (monogenes) of their first

king, who died prematurely.’ — wiki

Herodotus [Histories] 7.221.1 ‘Megistias sent

to safety his only-born (o monogenes, as

noun) who was also with the army.’ — wiki

Luke 9:38 ‘only born (o

monogenes)’ {noun}. — wiki

Josephus, Antiquities 2.263 ‘Jephtha’s

daughter, she was also an only-born

(monogenes) and a virgin.’ — wiki

John 3.16 For God so loved the world, that

he gave his only-begotten Son (o

monogenes uios). — wiki

Nicene Creed - ‘And in one Lord Jesus

Christ, the only-begotten Son of God.’

Clement of Rome 25 [First Epistle of

Clement] – ‘the phoenix is the only one

[born] (monogenes) of its kind.” — wiki

Notice the *meaning* in the last quotation. It’s not just the only-born, but “the only one [born] of its kind”: a combination of both interpretations. And that seems to capture the meaning of *monogenes* in the New Testament. The titles of Father and Son seemingly begin when Christ is earth-begotten or earthborn:

Heb. 1:5 ‘For unto which of the angels said

he at any time, ‘Thou art my Son (uios mou

ei su), this day have I begotten thee (ego

semeron gegenneka se)’? And again, I will

be to him a Father, and he shall be to me a

Son?’ (citing Ps.2:7, also cited Acts 13:33,

Heb. 5:5) —wiki

Filioque

In the Eastern Orthodox Church, the Father is seen as Greater than the Son and the Spirit. To offset this imbalance, the Nicene creed was amended by the Roman Catholic Church with the addition of the filioque clause. The original creed from the First Council of Constantinople (381) states that the Holy Spirit proceeds "from the Father,” to which the Roman Catholic West added, “and the Son,” as an additional origin point of the Holy Spirit. Maximus the Confessor, who is associated more with the Orthodox East than with the Catholic West, didn’t take issue with the filioque. Similarly, I. Voronov, Paul Evdokimov and S. Bulgakov saw the Filioque as a legitimate theologoumenon (i.e. theological opinion)!

The reason we’re discussing the filioque is because this issue bears on the question of whether Jesus is God by nature or by grace. The Filioque was added to the Creed as an anti-Arian addition by the Third Council of Toledo (589). It is well-known that The Eastern Orthodox Church promotes the “Monarchy of the Father,” which signifies that the Father alone is the only cause (αἰτία) of the Son and the Spirit:

The Eastern Orthodox interpretation is that

the Holy Spirit originates, has his cause for

existence or being (manner of existence)

from the Father alone as ‘One God, One

Father’, Lossky insisted that any notion of a

double procession of the Holy Spirit from

both the Father and the Son was

incompatible with Eastern Orthodox

theology. — wiki

The view of the superiority of the Father actually finds expression in both east and west:

The Fourth Council of the Lateran (1215):

‘The Father is from no one, the Son from the

Father only, and the Holy Spirit equally from

both.’ — wiki

This view leads to Arianism, as can be seen from the seventeenth ecumenical council:

The Council of Florence, session 11 (1442),

in Cantate Domino, on union with the Copts

and Ethiopians: ‘Father, Son and holy Spirit;

one in essence, three in persons;

unbegotten Father, Son begotten from the

Father, holy Spirit proceeding from the

Father and the Son; ... the holy Spirit alone

proceeds at once from the Father and the

Son. ... Whatever the holy Spirit is or has, he

has from the Father together with the Son.’

— wiki

This implies that both the Son and the Holy Spirit are not God by nature but by grace. Thus, they’re not fully God: they’re inferior, lesser gods, created eternally by the Father so to speak. This smacks of Arianism and contradicts scripture which states that “in Christ all the fullness of the Deity lives in bodily form” (Colossians 2.9). Conversely, Eastern Orthodoxy tends to put the Father on a pedestal:

In Eastern Orthodox Christianity theology

starts with the Father hypostasis, not the

essence of God, since the Father is the God

of the Old Testament. The Father is the

origin of all things and this is the basis and

starting point of the Orthodox trinitarian

teaching of one God in Father, one God, of

the essence of the Father (as the uncreated

comes from the Father as this is what the

Father is). — wiki

Conclusion

It doesn’t appear as if there are hierarchical rankings amongst the persons of the Trinity, comprising an ontological subordination of both the Son and the Spirit to the Father. To say that “the Son is derived from the Father who alone is without cause or origin” is nothing short of Arianism. As Catholic theologian John Hardon put it, subordinationism denies that the Son and the Spirit are consubstantial with the Father. Thus, it denies their divinity. This doctrine can be construed as if Christ, the Son of God, were inferior to the Father. It would also invalidate the three coequal, coeternal, consubstantial divine persons of the Trinity. The New Testament also makes it abundantly clear that Jesus is Yahweh (i.e. the Lord) and the almighty (see Revelation 1.8)!

It’s also clear that there’s no eternal Sonship in which Christ is eternally begotten. The appellations of Father and Son relate to the economy of God as it pertains to the Incarnation of Christ (cf. Hebrews 1.5). And *monogenēs* doesn’t seem to mean that the Son is eternally begotten and ontologically subordinate to the Father. Rather, it seems to denote the only God who has ever been born in time, or the “only-born God” (i.e. only-begotten). That is to say, no other God has ever been born in human history. So, as the Son of Man, Christ can be described as both “unique” and as the “only begotten.”

Finally, it should be stressed that Jesus is God by nature, not by grace which suggests Adoptionism. The Filioque was added to the creed as an anti-Arian formula to offset the “Monarchy of the Father,” which signifies that the Father alone is the only cause (αἰτία) or principle of the Son and the Spirit. However, there’s no basis for claiming an ontological inequality within the Trinity. What is more, it’s *a contradiction in terms* to speak of an inferior and a superior God. God is God. And there’s only one God. Therefore, if we don’t want to fall into heresy, we must maintain the concept of the Trinity, which affirms the existence of one God in 3 coequal, coeternal, consubstantial divine persons who share one essence (homoousion)!

#ontologicalsubordination#arianism#eternalSonship#monogenēs#subordinationism#IncarnationalSonship#EternalSubordination#μονογενὴς#adoptionism#εκ#ελικιτίμ#economicsubordination#heresy#το_μικρό_βιβλίο_τη��_αποκάλυψης#theology proper#begotten#Filioque#evangelicaltheologians#thelittlebookofrevelation#ecclesiology#eternallybegotten#trinity#elikittim#PostNicenefathers#ek#Eternalfunctionalsubordination#EasternOrthodoxtheologians#anteNicenefathers#Catholictheologians#father son holy spirit

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

#blessed silence#angel of great counsel#icon#mystery#burning bush#angel#inside#troica#poor#filioque#enter#heaven#Glinka choir#Alexey Mikhailov#Sviridov#Pushkin#garland#reveille#Youtube

0 notes

Text

Benedetto XIV Allatae Sunt e quella mano tesa agli scismatici greci e orientali - 26 luglio 1755

Benedetto XIV: il vero ed autentico “dialogo” ecumenico con le Chiese Orientali – Ai Missionari destinati all’Oriente – nell’enciclica Allatae Sunt del 1755

“Sono queste le cose che giudicammo doversi esporre in questa nostra Enciclica, non solo per chiarire le ragioni su cui si fondano le risposte date al Missionario, che propose le questioni esposte all’inizio, ma anche perché a tutti sia…

View On WordPress

#allatae sun#Armeni#Caldei#concilio di firenze#concilio di Lione#dialogo#ecumenismo#Filioque#grenorio x#Maroniti#orientali#ortodossi#papa Benedetto xiv#Prospero Lambertini#san leone ix#scismatici#Siri#urbano ii

1 note

·

View note

Text

Jews 🤝 Muslims

Not understanding whatever the fuck the Trinity is.

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Oooh, not Karl Rahner simultaneously intensifying my conviction that the Spirit proceeds from the Father and the Son, and convincing me asking the filioque to the Creed may have been a mistake after all

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

It’s filioque hours

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Oriente e Occidente

La storia degli uomini ha sempre una segnatura teologica e può essere pertanto istruttivo guardare all’attuale conflitto fra Oriente e Occidente nella prospettiva dello scisma che molti secoli fa divise la chiesa romana da quella ortodossa. Com’è noto, alla base dello scisma era la questione del Filioque: il credo romano affermava che lo Spirito santo procedeva dal Padre e dal Figlio (ex Patre Filioque), mentre per la chiesa ortodossa lo Spirito santo procedeva solo dal Padre.

Se traduciamo il linguaggio teologico in concreti termini storici, ciò significa – dal momento che il Figlio incarna l’economia divina della salvezza sul piano della storia terrena – che per l’Oriente greco-ortodosso la vita spirituale dei credenti non era direttamente implicata nel piano dell’economia storica. La negazione del Filioque separa il mondo celeste da quello terreno, la teologia dall’economia storica. E questo – senza il pregiudizio di altri fattori – può spiegare perché l’Occidente – soprattutto nella sua versione protestante – rivolge allo sviluppo dell’economia storica un’attenzione affatto sconosciuta al mondo greco-ortodosso, che sembra ignorare la rivoluzione industriale e permanere ancorato a modelli feudali. Tradotto in termini teologici, anche il primato marxista dell’economia sulla vita spirituale corrisponde perfettamente al nesso dello Spirito santo col Figlio che definisce il Credo dell’Occidente.

Tanto più gravido di conseguenze è il rovesciamento che si produce con la Rivoluzione russa, quando il modello occidentale del primato dell’economia storica viene innestato a forza su un mondo spiritualmente del tutto impreparato a riceverlo. Ancora una volta, in questa prospettiva il fallimento del modello sovietico e l’evidente riproposizione di motivi teologici nella Russia postsovietica si lascia spiegare come il ritorno della rimossa indipendenza dello Spirito santo, che ritrova quella posizione centrale che il regime comunista non era riuscito a cancellare.

Tanto più assurdo appare che – mentre negli ultimi decenni la Chiesa romana e quella ortodossa si erano andate riavvicinando – l’Occidente, non a caso sotto la guida di un paese protestante, riproponga ora – più o meno inconsapevolmente in nome del Filioque – una guerra senza quartiere con la Russia ortodossa.

20 dicembre 2023

Giorgio Agamben

8 notes

·

View notes

Note

I'm sorry if this seems stupid or offensive, but how would you describe the major denominations of Christianity?

I was raised Lutheran but actively chose to not get a confirmation and never actively studied religion, so I know very little about what makes for example Catholicism different from Orthodoxy other than "those are the ones from Italy vs Greece"

I know you are a Muslim but you really seem educated on this as well, so I would be really interested to hear what you say. You don't have to be very detailed if you don't want to.

I'm about to sleep, so here's something quick:

Besides their liturgies being held differently due to the Christian schism, they're kinda disagreeing on stuff like how there isn't a papacy, since that was just a made up thing, according to the Orthodox. The idea comes from the fact that Peter was given the bind to Heaven, which would then pass down to people. Orthodox claim that Peter wasn't the only one given the key, also because humans aren't infallible (by conception) besides Christ.

The Orthodox Christians asl believe that the holy ghost proceeds from the Dad, since there is no evidence that the ghost proceeds from both the dad and the boy (filioque). Since that was written in the Nicaean Creed, it caused a bit of a ruckus or as I'd like to call it, a schism. Protestants inherited the Catholic view.

They also argue over the fact that Mary isn't sinless by conception, since that would mean that Dad is unfair cause his grace should extend to everyone else, so why would a human like Mary be sinless? So she was born with sin like everyone else. However, Mary didn't commit any personal sins in her life. At least Catholics have two thing in common with us Shi'as, lmao.

Oh yeah, Orthodox Christians don't believe in a stopway between Earth and the afterlife, such as purgatory or the indulgences. That's some Catholic stuff.

As for saints, Orthodox don't only hold that intercession is enough, you gotta live like them and engage in a synergic relationship with them to achieve spiritual growth. Catholic simply take them as intercessors.

40 notes

·

View notes

Text

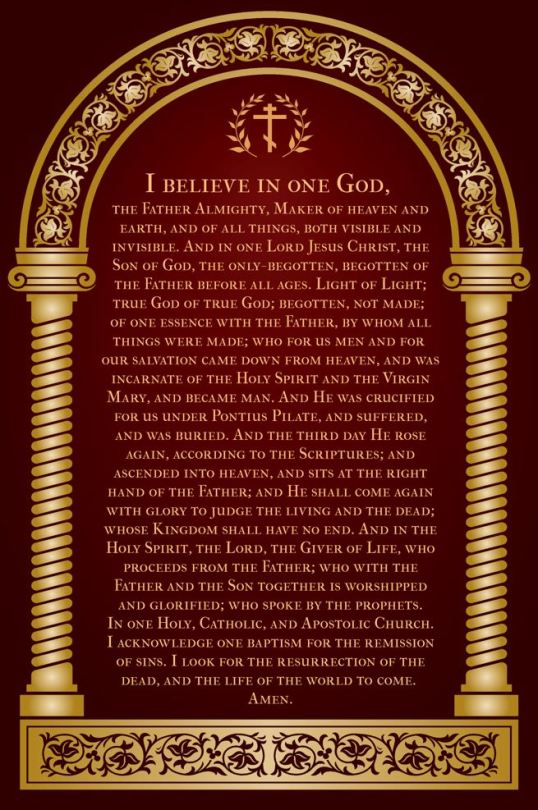

The Seven Ecumenical Councils: The Creed

The doctrinal definitions of an Ecumenical Council are infallible. Thus in the eyes of the Orthodox Church, the statements of faith put out by the Seven Councils possess, along with the Bible, an abiding and irrevocable authority.

The most important of all the Ecumenical statements of faith is the Nicene-Constantinopolitan Creed, which is read or sung at every celebration of the Eucharist, and also daily at Compline. The other two Creeds used by the West, the Apostles' Creed and the 'Athanasian Creed', do not possess the same authority as the Nicene, because they have not been proclaimed by an Ecumenical Council. Orthodox honour the Apostles' Creed as an ancient statement of faith, and accept its teaching; but it is simply a local western Baptismal Creed, never used in the services of the Eastern Patriarchates. The 'Athanasian Creed' likewise is not used in Orthodox worship, but it is sometimes printed (without the filioque) in the Greek Horologian (Book of Hours).

-- Kallistos Ware, The Orthodox Church

5 notes

·

View notes

Note

'so-called eastern catholics' thank you for your insight, john

I mean, they sold out their theology in exchange for submission to Rome, what more can I say? Many of them don't even realize that they actually are required to believe in the Filioque, and other things like allowing infant communion, the Divine Liturgy itself, and married priests are looked down upon by the Latin Rite hierarchy. They will never be treated as equals, especially not by the Vatican, who turn around and use "Eastern" Catholics to accuse the Eastern Orthodox Church for "having too much pride" to take the same deal they did.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Le filioquisme... et autres mots compliqués

Le fait d'avoir fait figurer ce mot étrange dans un ''édito'', il y a quelques semaines (cf. ''Retour à Ravenne'', le 18 octobre dernier) m'a valu un mini déluge de questions, dans le genre ''Kékcékça ?'' ou ''Céquoicetruc ?'', qui appellent deux mots d'explication. Ces deux mots, comme c'est souvent le cas, vont vite ''faire des petits''... et voilà comment naît un ''édito'' auquel on n'avait jamais pensé ! Ce texte est un peu particulier dans le lignée habituelle de ce Blog et ce ''billet'' est nettement moins léger que celui d'hier, sur les tatouages... J'en demande pardon...

La nature-même du sujet rend impossible toute explication simple et rapide. ''Filioque'' (qui se prononce ''filiocoué'', et qui veut dire ''et du Fils'', en latin) est un terme sorti du Credo de l'Église catholique romaine qui signifie que le Saint-Esprit ne procéderait pas du Père seul, mais du Père ''et du Fils'', ce qui fait ressembler cette querelle à une dispute entre spécialistes. Et pourtant, la ''disputatio du Filioque'' sur le Dogme de la Sainte Trinité hante la chrétienté depuis le VIIIᵉ siècle. Elle aboutira même, en 1054, à la séparation des Églises de Rome et de Constantinople, donnant naissance à la dualité Catholiques-Orthodoxes, avec ses conséquences dramatiques...

Dit comme ça, on ne peut penser qu'à une querelle entre évêques et théologiens, et ''pointus'', encore ! Mais pas du tout : c'est vraiment de la grande Histoire, avec tout ce que ce mot peut charrier de violence, de sang, et de drames. Pour le comprendre, il faut faire un petit retour sur les fondamentaux : pour tous les chrétiens, ''Dieu est unique, en trois ''hypostases'', autrement dit : Un seul Dieu, mais fait de ''trois parties individualisables'' --ce qui est plus exact que le classique ''en trois personnes'', qui est une traduction trop anthropomorphique (Traduttore, tradittore, disent les italiens : ''traduire, c'est trahir'').

Pour ''faire simple sur un sujet compliqué'', le meilleur exemple est de regarder une pièce de monnaie : chacune de ses faces et sa tranche sont parfaitement identifiables... et pourtant, on ne peut parler de l'un de ces éléments sans y inclure les deux autres, on ne peut en isoler un seul, en traiter un autrement que les deux autres, etc... : la pièce est une, en trois parties totalement unies et indiscutablement définies. Le Dieu des chrétiens est, de même, dit ''un et trine'', et le fait que l'un de ces éléments ait été, ou pas, ''engendré'' directement de Dieu-le-Père ou via Dieu-le-Fils pose donc le problème de l'importance de ses relations avec les deux autres, on dirait, dans notre société, ''son rang hiérarchique'' (NDLR : je demande pardon pour l'aspect assez ''technique'' de ce sujet, qui semble ressortir de l''Histoire des religions''... alors qu'il est d'une actualité on-ne-peut-plus-brûlante, dans une France qui se déchire autour d'interprétations de mots qui signifient la même chose et son contraire... et d'un Président qui érige son ''et en même temps'' en ''principe premier'' –ce qu'il ne pourrait être, évidemment !).

Alors que les Pères latins ont insisté sur une ''processio ex Patre Filioque'' (= une marche solennelle à partir du Père et du Fils), les Pères grecs ont, dès le IVè siècle, souligné l'antinomie entre une Uni-Trinité et une seule essence en trois hypostases : le Père est le "principe sans origine", le Fils est "engendré" par le Père, et l'Esprit vient du Père, disent les grecs. Ainsi la ''processio'' latine diffère de ''l'ekporeusis'' grecque (dont la traduction en français est : ekporèse (sic !), mot qui doit être utilisé une fois ou deux par millénaire ! Avec cet éditorial, ça va monter, d'un seul coup, à 3 fois !).

Dit autrement : dans l'entendement romain, l'Esprit procède donc à la fois du Père et du Fils (''Filioque''), alors que chez les grecs (si j'ose !), l'Esprit Saint tire son existence du Père uniquement, sans passer par le Fils. Cette querelle, d'apparence mineure, a pourtant été responsable d'une des plus grandes catastrophes historiques de tous les temps : la séparation définitive (à ce jour encore !) des Latins et des Orientaux, drame qui a scellé –comme nous le racontions le 18 octobre-- la chute de Constantinople et la fin de l'Empire romain... ce qui est un fait historique parmi les plus graves de tous les temps, dans ses conséquences, jusqu'à aujourd'hui, de la naissance de l'Empire ottoman et ses atrocités puis son effondrement plein d'horreurs , à sa ''renaissance'' (?) désirée par la folie d'Erdoğan, qui nous fait tourner en bourriques et se fout de nous, à son gré et pour notre plus grande honte...

Jusqu'au VIIIe siècle, la contradiction affirmée entre ces deux approches n'était ressentie comme insupportable par personne, et les Occidentaux ont même bien ''reçu'' le Credo latin –dit : de Nicée-- qui affirme : "Je crois [...] au Saint-Esprit [...] qui vient du Père et du Fils", allant jusqu'à donner une valeur dogmatique au Filioque dans plusieurs conciles, entre 447 et 797. La querelle a éclaté au IXe siècle, lorsque l'Occident a ''créé'' un Empire carolingien qui va s'opposer à Byzance, Charlemagne contre le Basileus Nicéphore, et Saint Empire Romain Germanique contre Empire Romain d'Orient. L'incompréhension réciproque des langues de référence, et de mots comme ''processio'' et ''ekporeusis'' favoriseront l'affrontement. Et en 807, quand les Grecs suppriment le Filioque du Credo, les moines latins les accuseront d'hérésie, et Photius, le patriarche de Constantinople, dénoncera à son tour une hérésie des latins...

Pendant tout le moyen âge, cette division entre chrétiens d’Orient et d’Occident va s’aggraver, et le "Filioque" va devenir le symbole des différences, un signe évident de ce que chaque partie de la chrétienté divisée trouvait comme manque ou distorsion chez l’autre. Et lorsque l'armée du sultan Mehmet II va assiéger Constantinople, c'est à cause de ce ''Filioque'' que l'antique Byzance va être abandonnée par Venise, la Sérénissime –dont la puissante flotte de galères aurait pu desserrer le siège-- ayant soumis son aide à l'abandon inconditionnel de ce désaccord... dont seules quelques élites (?) savaient de quoi il retournait, les populations n'ayant (déjà !) qu'une seule idée en tête : le départ des musulmans et un retour dans le cadre ''normal''.

Filioquisme hier, islamophobie et anti-judaïsme aujourd'hui... on frémit à la pensée que les fausses querelles de mots qui polluent nos médias, nos ministères et nos enceintes soi-disant nationales (en réalité : si peu représentatives et si peu soucieuses des vrais besoins de leurs administrés), ne finissent par déboucher sur un second effondrement de notre belle et riche civilisation, aujourd'hui de plus en plus envisageable et dont l'éventualité, même niée par les myopes qui sont ''aux manettes'' et en sont donc largement co-responsables, semble de jour en jour plus possible, hélas. Comme ledit le proverbe, ''Le diable se cache dans les détails...'', et une fois de plus, ''comprendre hier'' –même confus et touffu-- peut permettre de ''comprendre demain'', qui s'annonce au moins aussi inintelligible et aussi échevelé qu'hier et qu'avant-hier...

H-Cl.

3 notes

·

View notes

Note

hey it’s totally okay if you don’t want to answer this, but what made you decide to go Orthodox? I’m just curious since you were such a staunch Catholic, so it’s surprising to see this change

Well, I’m not Orthodox yet; my husband and I are trying to set up a meeting with our local Greek Orthodox parish’s priest so we can discuss theology and next steps with him. Trust me, no one is as surprised about this change as I am. Less than a year ago, I never would’ve dreamed that I would be leaving Catholicism, but, you know…God calls me where He calls me. I’m also not here to pick any fights with Catholics or try to argue/sway anyone over to the other side, so I hope my Catholic followers and mutuals know this is just me giving an honest explanation for my decision. Anyways, here are my main reasons:

1. The papacy. This is honestly THE big reason for my switch, and that’s not because I hate Pope Francis (I don’t) or anything like that. An honest look at early Church history and Scripture gave me the impression that the Bishop of Rome’s role wasn’t as clear cut and “in charge of everything” as the Catholic Church now claims. Vatican I in particular made me uncomfortable when I sat down and realized Christ’s Church supposedly took 18 entire centuries to declare papal infallibility as dogma. That’s…a very big thing to leave “unofficial” for so long. I understand the pragmatic reasons for the papacy growing in power the way it did over the centuries, particularly when you account for the fall of the Roman Empire and the secular politics the Catholic Church had to get involved in throughout history, but it all leaves me with the impression that the Church spun together theological explanations for pragmatic moves after those moves were already made.

2. Infant Communion. So, the Eastern Orthodox Church allows her babies to receive Communion, whereas the Catholic Church requires all children to wait until the “age of reason.” There are theological arguments for both sides, but I was more interested in which practice came first historically, because whichever practice is the earliest has the highest chance of coming directly from the Apostles themselves. In a shocking twist, infant Communion is indeed what the West practiced alongside their Eastern brethren before pragmatic reasons required the West to change. Personally, I find the age God wants one to begin receiving His Body and Blood very important, so this issue in particular sticks out like a sore thumb.

3. The Orthodox view of sin. It’s hard for me to explain clearly, but the Eastern Orthodox don’t separate sins between “mortal” and “venial.” Sin is not an “on/off switch” between salvation and damnation, but rather a sickness that separates you from God more and more each time you indulge in it. The “sin and Confession” process isn’t as straightforward as “If you commit a sin from THIS SPECIFIC LIST, you GO TO HELL unless you CONFESS.” You’re really supposed to confess every sin you commit so you can let your soul be healed and repair your relationship with God. (I know this sounds similar to the Catholic approach, but an actual Eastern Orthodox Christian can explain it better than me.)

4. The Filioque. I honestly can’t see how history backs the Catholic side of that debate, and I’ll just leave it at that.

5. Mass vs. Divine Liturgy. I have to concede that trads bring up a good point about how so many Masses done in the Ordinary Form lack reverence. My husband and I experienced a Mass in New Orleans that was APPALLING. Communion was being handed out like candy by EM’s as they walked around the pews, pre-recorded music was played, the altar servers walked down the aisle in jeans and hoodies. As recently as six months ago, I aggressively pointed out that there are plenty of reverent Novus Ordos, and while that’s true, it doesn’t change the fact that a “clown Mass” (as trads call irreverent Masses) is even allowed in the Catholic Church in the first place. Sure, on the books, the OF is supposed to be celebrated reverently, and I wouldn’t feel as strongly about this point if irreverent Novus Ordo Masses weren’t such a widespread problem, but it seems like next to nothing is done to actually enforce this rule. But, when you look at the Eastern Orthodox, you see the Divine Liturgy, which still maintains the Tradition and reverence that are wholly appropriate for celebrating the Eucharist and also used to be found in the Extraordinary Form in the Catholic Church. I’ll readily admit I was wrong about thinking the Catholic Mass isn’t in a dangerous position, but realizing this only led me down a different path than many TradCats.

I have more reasons, but these are just the main ones that come into my head. I have to stress that I still love the Catholic Church and have nothing against Catholicism; in many ways, I’m even sad to leave it all behind. You won’t see any Catholic bashing from me. But there are also many points where the Eastern Orthodox Church is what I originally thought the Catholic Church to be before my eyes were opened.

22 notes

·

View notes

Note

what is the difference between Orthodox Christianity and Western Catholic Christianity?

I’ve run into definition problems with friends before so I’m assuming a lot here but…

When I say “Orthodox Christianity” I am referring to the “Eastern Catholic Orthodox Church” and “Western Catholic Christianity” generally refers to the “Roman Catholic Church”.

There are many differences but the most apparent are:

The Filioque, Orthodoxy does not have the “the son” in the Apostles Creed when talking about the Holy Spirit (the Western Church added it later)

Orthodoxy does not believe in the infallibility of the Pope nor do we recognise he has any “special” position, he is just another bishop.

Orthodox do not believe in the Immaculate Conception and have a different view of “Original Sin” (see ancestral sin)

Orthodoxy has a different liturgy than Roman Catholics

Orthodox generally believe that Heaven and Hell are the same place, only experienced differently depending on your life and relationship to God. We do not believe in purgatory nor in “cleansing fire”.

Our priests can get married, as long as they are married before ordination.

There are a lot more but those are the basics.

11 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Today we celebrate Photius the Great, Archbishop of Constantinople. As for the thrice-blessed Photius, the great and most resplendent Father and teacher of the Church, the Confessor of the Faith and Equal to the Apostles, he lived during the years of the emperors Michael (the son of Theophilus), Basil the Macedonian, and Leo his son. He was the son of pious parents, Sergius and Irene, who suffered for the Faith under the Iconoclast Emperor Theophilus; he was also a nephew of Saint Tarasius, Patriarch of Constantinople (see Feb. 25). He was born in Constantinople, where he excelled in the foremost imperial ministries, while ever practicing a virtuous and godly life. An upright and honorable man of singular learning and erudition, he was raised to the apostolic, ecumenical, and patriarchal throne of Constantinople in the year 857. The many struggles that this thrice-blessed one undertook for the Orthodox Faith against the Manichaeans, the Iconoclasts, and other heretics, and the attacks and assaults that he endured from Nicholas I, the haughty and ambitious Pope of Rome, and the great persecutions and distresses he suffered, are beyond number. Contending against the Latin error of the filioque, that is, the doctrine that the Holy Spirit proceeds from both the Father and the Son, he demonstrated clearly with his Mystagogy on the Holy Spirit how the filioque destroys the unity and equality of the Trinity. He has left us many theological writings, panegyric homilies, and epistles, including one to Boris, the Sovereign of Bulgaria, in which he set forth for him the history and teachings of the Seven Ecumenical Councils. Having tended the Church of Christ in holiness and in an evangelical manner, and with fervent zeal having rooted out all the tares of every alien teaching, he departed to the Lord in the Monastery of the Armenians on February 6, 891. May he intercede for us always + Source: https://www.goarch.org/chapel/saints?contentid=527 (at Constantinople - Κωνσταντινούπολη) https://www.instagram.com/p/CoS7WF5hGb6/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

6 notes

·

View notes