#Fania Borach

Text

29 maggio … ricordiamo …

29 maggio … ricordiamo …

#semprevivineiricordi #nomidaricordare #personaggiimportanti #perfettamentechic

2021: Gavin MacLeod, Allan George See, attore e predicatore statunitense, noto soprattutto per aver preso parte alla serie TV Love Boat, in cui recitò dal 1977 al 1987, nel ruolo del comandante Merrill Stubing. Nel 1956 debuttò a Broadway nel dramma Un cappello pieno di pioggia e fu in questo periodo che scelse il suo nome d’arte. La popolarità di questo ruolo leggero costituì però un limite per…

View On WordPress

#29 maggio#Allan George See#Betsy Palmer#Carl Boehm#Coral Browne#Delma Byron#Dennis Hopper#Diego Pozzetto#Edward G. Ross#Edwin G. Ross#Fania Borach#Fanny Brice#Françoise Blanchard#Franca Rame#Gavin MacLeod#Gladys Louise Smith#Harvey Korman#Inge Landgut#John Barrymore#John Sidney Blyth#Karlheinz Böhm#Laurence Irving#Laurence Sydney Brodribb Irving#Lou Kamante#Lu Kamante#Lu Kanante#Luciano Rossi#Mabel Hackney#Mabel Lucy Hackney#Mary Pickford

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Fanny/Funny Girl

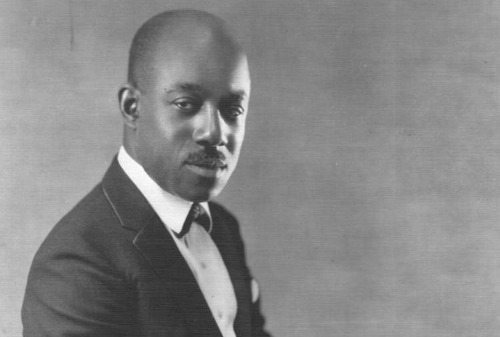

Fania Borach, known professionally as Fanny Brice, was a popular and influential American comedienne, singer, theatre and film actress, who was born on 29 October 1891.

Before becoming a film star, she was an illustrated song model, i.e. she appeared on the still images used to illustrate song lyrics and to accompany live performers in different venues.

She died in 1951 and thirteen years after her…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Photo

A unique, fashionable, lined notebook with modern and amazing Fanny Brice cover. It's your notebook and you can write here your goals, tasks and big ideas. On the special first white page is information - This notebook belongs to: (and a little motivation and inspiration about you! :) ). This great quality product make amazing gift perfect for any special occasion or for a bit of luxury for everyday use. Blank Notebooks Are Perfect for every occasion: Stocking Stuffers & Gift Baskets Graduation & End of School Year Gifts Teacher Gifts Art Classes School Projects Diaries Gifts For Writers Summer Travel & much much more… (proud, focus, fun, achievement, trust, pleasure, investments, profit, money) Fania Borach (October 29, 1891 – May 29, 1951), known professionally as Fanny Brice or Fannie Brice, was an American illustrated song model, comedienne, singer, theater, and film actress who made many stage, radio, and film appearances. She is known as the creator and star of the top-rated radio comedy series The Baby Snooks Show.Thirteen years after her death, Brice was portrayed on the Broadway stage by Barbra Streisand in the 1964 musical Funny Girl; Streisand also starred in its 1968 film adaptation, for which she won an Oscar, and in the 1975 sequel, Funny Lady. See the other products in this exciting series and discover hidden talents within yourself now! ⬇️⚜️⬇️⚜️⬇️⚜️⬇️⚜️⬇️ https://www.amazon.com/Fanny-Brice-notebook-achieve-Notebooks/dp/1700795473/ref=mp_s_a_1_1?keywords=lucanus+brice&qid=1574492534&sr=8-1 ⬆️⚜️⬆️⚜️⬆️⚜️⬆️⚜️⬆️ #streisand #borach #lucanus #notebook #notebooks #kdp #amazon #kindledirectpublishing #books #book #note #journal #inspiration #writing #gift #giftideas #amazing #biography #quotes #motivationalquotes #famous #famous #business #entrepreneurship #entrepreneur #marketing #motivation https://www.instagram.com/p/B5MusXBAdIg/?igshid=1thj59uxgn1mu

#streisand#borach#lucanus#notebook#notebooks#kdp#amazon#kindledirectpublishing#books#book#note#journal#inspiration#writing#gift#giftideas#amazing#biography#quotes#motivationalquotes#famous#business#entrepreneurship#entrepreneur#marketing#motivation

0 notes

Link

Fanny Brice (1891-1951) [comedian, singer, and actress] When Fanny Brice sat down to compose her autobiography, she told the writer, “I lived the way I want to live and never did what people said I had to do.” Fanny Brice, born Fania Borach, is a comedic legend who went about her life with audacious tenacity. […] The post Famous Estates-Champ or Chump? Fanny Brice appeared first on The Mendel Law Firm, L.P..

0 notes

Text

XXI: 1921

On Black Suffering as Spectacle, Paths to Immortality, and the Art of Noise

1. Noble Sissle and Eubie Blake: “Love Will Find a Way”

1920 saw Black American performers finally allowed to speak in their own voice on record, not an assumed one or through a minstrel mediary; and 1921 was the year that the same thing happened, in an even more unlikely fashion, on (actually off-off-) Broadway. Just like “Crazy Blues,” Shuffle Along saw the respectable tenth cringe at its low-down humor and sexy swing, and later generations would reject the blacked-up comedians who enacted the ribbon-thin plot, but attendance records were hardly broken over some slapstick: as with all good shows, catchy melodies sold tickets. Sissle had sung with Jim Europe, and Blake had ragged up and down the coast, and their score, jaunty or rowdy or plaintive as necessary, made Shuffle Along the first jazz musical. But this, the lovers’ duet, is more besides: the first true Black American love song, unblemished by minstrelsy.

2. Bert Williams: “Brother Low Down”

As a new generation, the jazz generation represented here by Sissle and Blake, dawns, the previous generation, powered by ragtime, vaudeville patter, and Coon song, sets. Bert Williams, here from the beginning, bows off with this mordant character sketch of an itinerant street preacher begging for booze money and defensive about his preaching permit. It’s Coonery, in the generic sense of presenting a caricature of blackness for the amusement of whites, but it’s also part of a long Black (and Jewish) tradition satirizing religious hypocrisy and celebrating idiosyncratic locutions. Williams collapsed on stage in February 1922, his final public act being to raise a laugh from an unfeeling audience believing it was part of the show. Which as a metaphor for his career, and the entire century, is hard to better: Black suffering as just another disposable consumer product, entertainment to the end.

3. Ethel Waters: “There’ll Be Some Changes Made”

With a song pitched at the exact midpoint between Sissle and Blake’s middle-class reverie and Williams’ working-class satire, we meet one of the century’s legendary figures, one of the peerless voices of the jazz-song revolution already underway. Written by overlooked Black composer Benton Overstreet and underappreciated Black comedian Billy Higgins (both retrospectively pointed out by Langston Hughes as masters in their field), “There’ll Be Some Changes Made” lifts a line from “Crazy Blues” to produce a more overtly comic song about putting oneself back together after being walked out on by a no-good man. Waters’ sweet-and-sour voice neither overplays the comedy nor makes a blues tragedy of the material: one of the first great recordings of the Harlem Renaissance, its clear-eyedness and good humor about sexual relations between consenting adults makes yet another subject on which Black America reluctantly instructed its white counterpart.

4. Fanny Brice: “Second Hand Rose”

The B side of Victor 45263 would in time prove to be one of the most influential recordings in US musical history, arguably inventing the torch song as a genre, but we met “Mon homme” last year on the continent where it was even more influential. Anyway the A side, “Second Hand Rose,” is far truer to Fanny Brice’s stage persona: a nice but impoverished Jewish goil whose ignorance, forthrightness, and pretensions are played for laughs — but crucially, the laughs came not only from the presumed upper-crust WASP theater audience, but from her fellow immigrants. The rubber-faced, nervily dynamic performer born Fania Borach had headlined the Follies in 1910, when she was just nineteen; ten years later she was back with Ziegfeld and bigger than ever. Jolson and Cantor got better publicity, but of that generation of Jewish-American stars, she was the genius.

5. Marion Harris: “Look for the Silver Lining”

Three years on from the Great War, only one of the Powers was experiencing an economic boom. Americans have traditionally been optimists anyway, but the psychological moment was even more ripe for popular songs expounding on the tenets of the New Thought, a philosophical charlatanry whose descendants include the Power of Positive Thinking and the Secret. Even Al Jolson making a bid as the Apostle of Pep with “April Showers” wasn’t as complete a victory for the sunny-side-up brigade as the smash hit from Sally, the Jerome Kern musical which inaugurated the Flapper decade almost as neatly as Shuffle Along inaugurated the Harlem same. The lyric for “Look for the Silver Lining” functions beautifully in the show as the plucky title character’s never-say-die philosophy, but it’s that swoony Kern melody which has made it immortal, long after every silver lining has rusted over.

6. Van & Schenck: “Ain’t We Got Fun?”

A more cynical philosophy, if one just as indelibly associated with the new decade, is expressed here, in our first encounter with Tin Pan Alley composer Richard A. Whiting, whose career will cross our paths many times more. His skip-a-doodle melody ensured the song a long life in newsboy’s whistles, but it’s Gus Kahn’s witty, slangy lyric, highlighting the contrast between the jet-setting lifestyle promised in magazine advertisements and the actual poverty experienced by millions in a time of ever-sharper inequality, that made the tune so characteristic of its era that it’s been quoted everywhere from Gatsby to Zelig. The vaudeville harmonists Gus Van (baritone) and Joe Schenck (countertenor), Americans of German stock who happily embraced Irish, Italian, or Jewish stereotypes depending on the routine, had the hit record, and their beefy, down-the-middle rendition sells both the title’s cheerfulness and the verses’ shrug.

7. Sam Moore: “Laughing Rag”

As jazz became, seemingly overnight, the newest sensation in popular music, its forefather ragtime, freed from the burden of being the most advanced thing going, continued to mutate. This record, essential to any history of jazz or even country music, takes the Hawai'ian slack-key technique (though on the Octo-Chord, a custom-built eight-string guitar) and applies it to ragtime proper, approaching jazz at one end and predicting Nashville steel pedal workouts for generations to come at the other. His protegé Roy Smeck’s 1928 cover of “Laughing Rag” is canonical in Grand Ole Opry lore, but it is Virginia-born vaudevillian, eccentric, and (briefly) Follies star Sam Moore who sits at the crossroads of Hawai'ian and country music, and his ragtime will, as we will see, spread kudzu-like through the broad highways and quiet backwaters which make up all the musical permutations of the American South.

8. James P. Johnson: “Keep Off the Grass”

Another, and perhaps more consequential, mutation of ragtime was the strain developed by piano hustlers at Harlem rent parties, hired hands to make the joint bounce so the hosts could make rent, a strain which only made its way onto record in 1921. New Jersey native James P. Johnson was the acknowledged master of the new “stride” piano style, so named because of the distance the hands traveled in order to maintain the rock-solid rhythm and harmonic filigree. Comparison to the popular piano novelty of the day, “Kitten on the Keys,” is instructive: Johnson’s composition has a real low end, a greater chromatic range, and an ass-shaking drive. Where “Kitten” simpers, “Grass” slams, which is why stride looks forward to boogie-woogie and thence to rock & roll, and thus gains a measure of eternity. Novelty lives for a day; Black American jazz is forever.

9. Johnnie Dunn’s Original Jazz Hounds acc. Edith Wilson: “Nervous Blues”

The “Crazy Blues” blues craze continues apace; this overview, attempting to look in dozens of directions at once, can only skim the surface. Edith Wilson was an another all-around singer rather than a blues singer strictly speaking, and had only been professional for two years when she found herself swept up in Columbia’s dragnet. With Wilson singing a Perry Bradford composition for Johnnie Dunn, who had led Mamie Smith’s band, “Nervous Blues” is as straight a sequel to “Crazy Blues” as anything, including Mamie’s own voluminous output. The subject was in the zeitgeist anyway — popularizations of Freud claimed nerves as the trouble of the age, and nervous disorders were, along with urbanization and Jewishness, diagnosed as one of the three scourges of traditional values by reactionaries everywhere, including Hitler; in which climate, there’s something heroic about a Black woman owning her mental health.

10. Gertrude Saunders: “I’m Craving for That Kind of Love”

Edith Wilson’s primary claim to fame in the later 1920s would be her showcases in revues built around Florence Mills, the startling comet of Black excellence in music, dance and comedy who flashed so briefly across the Harlem Renaissance that she never recorded; but she will haunt these pages. Florence was catapulted to fame as a replacement for the soubrette role in Shuffle Along; the woman she replaced was Gertrude Saunders, whose most legendary achievement in later years was getting cold-cocked by Bessie Smith over a man; but here, singing the song that Florence would make her own within a year, she whoops and hollers, turning Sissle and Blake’s original tune almost unrecognizable in her performance of salacious, wild-child desire. It’s the sort of gleefully unhinged performance that would come to be associated with punk rock, and it’s all we have of her.

11. Eubie Blake: “Sounds of Africa”

As epochal as Shuffle Along was, it was not the only, or perhaps even the greatest, achievement of its composer in the year of his glory. “Sounds of Africa,” its title usually changed to “Charleston Rag” in later publication form, is one of the deathless piano solos of a decade in which the piano solo recording became an art form to itself. Blake’s heterogenous musical apprenticeship had included years playing for the high rollers in Atlantic City, one of the liminal spaces where white people consumed Black bodies, services, and art without making much distinction between them; generally unaware that those Black bodies were doing just as much consuming. “Sounds of Africa” features both a funky walking bassline and Debussy-like chromaticism, and it is ragtime pushing not just into furious, hard-rocking modernism, but into regions of pure sound. That you can dance to.

12. Carlos Gardel: “La copa del olvido”

Tango and jazz were experiencing simultaneous early golden ages in 1921, but the dynamics of the musics’ dissemination were quite different. Shuffle Along was a landmark theatrical event, the first jazz musical; meanwhile, Cuando un pobre se divierte, the play from which “La copa del olvido” became working-class dramatist and lyricist Alberto Vaccarezza’s first hit song, was only another of the hundreds of sainetes criollos, in which tango songs were de rigeur, being produced in Buenos Aires in those years. Gardel, the by now irreplaceable voice of tango, recording the song — and Enrique Delfino, who has appeared here frequently as a composer, providing the music — was a greater imprimatur than the show. Although neither Gardel’s tremulous performance nor Delfino’s sketchy melody make the song immortal: that’s the lyric, in which the singer calls for another round while he contemplates murdering his faithless lover.

13. Grupo do Moringa: “No rancho”

The vast majority of our visits to Brazil have been to Rio de Janeiro, where the port-town outbreaks of miscegenation, musical and otherwise, allowed such epochal musical traditions as the samba to flourish. But Brazil has always been much larger and more diverse than that; as one hint of which, over to composer Eduardo Souto, born in Rio but who consciously worked in all of the established Brazilian (and some foreign) musical fields. “No rancho” (in the countryside) is designated as a cateretê, by legend an ancient folkloric Amerindian dance, revived by São Paulo cosmopolites like vanguardist poet and novelist Mário de Andrade, who considered it one of the few authentic Brazilian traditions. Souto’s melodic and rhythmic sense, though, is anything but ancient, and such representations of countrified subaltern traditions given national mythological meaning by sophisticated urban tastemakers was hardly limited to Brazil.

14. Georgel: “La vipère”

Vincent Scotto, the great twentieth-century composer of French chanson réaliste, is by now a regular in these pages, but the interpreter is new to us, though in 1921 he was well-known to Parisian audiences. His pompadour and mincing stage manner was borrowed (with blessings) from Félix Mayol, and his choice of repertoire owed something to music-hall legend Harry Fragson, but between the wars Georgel far outstripped his old masters as one of the key voices of les années folles. “La vipère” is about one of Scotto’s (and popular culture’s) standbys, the female viper, who tempts the young man away from work, home, and family, to keep him in misery while she sells her body. He gets his revenge in the final verse in classic Grand Guignol fashion, but the gruesome narrative isn’t really the point: Georgel’s half-sobbing, half-humorous delivery exemplifies the (French) decade.

15. Orchester mit Refraingesang: “Das Lila Lied”

A landmark in queer media, “Das Lila Lied” (the lilac song) was very likely the first gay anthem in Western popular music. Deviance, sexual and otherwise, had long been a subject of chanson, but lyricist Kurt Schwabach and composer Mischa Spoliansky — two Jews working in Berlin’s legendary queer-friendly kabarett scene — dedicated their lied to Magnus Hirschfeld, the researcher whose Institute for Sexual Science was the first organization in the Western world to advocate for the rights of homosexual and transgender citizens. The chorus, which begins and ends “We are different from the others,” is as much protest song as sentimental education, the way pop usually works; but although the Weimar Republic officially protected homosexuality, it was still so taboo that Spoliansky used a pen name, and as far as I can ascertain, the players and singer of this, the first recording, remain uncredited.

16. Kandel’s Orchestra: “A Zoi Feift Min Un a Schweiger”

By 1921, the most modern and up-to-date form of popular music was the dance band, playing uptempo, lightly syncopated but not actually jazzy music with orchestral instruments. Paul Whiteman was the clear leader, but there were similar outfits in every city in the nation, and much of the rest of the world. Which was nothing new to the Eastern Europe-born klezmorim of New York, who had been working in similarly-sized outfits, and often at much faster tempos, for decades without being embraced by uptown goyim hotel dancefloors. Clarinetist Harry Kandel, born in the Ukraine, was one of the great klezmer bandleaders of the era, and on this recording, “Putting it Over on Mother in Law,” he pushes his orchestra to such whirling, piercing heights, with the drummer knocking regular off-beats, that together they predict not only swing, but even elements of free jazz.

17. Achilleas Poulos: “Kamomatou”

Relatively little is known about proto-rebetiko singer Achilleas Poulos, save that he was born in the northwestern Balıkesir province of Turkey (then the Ottoman Empire), and emigrated to the United States in 1913. His powerful voice and wide repertoire made him a briefly popular recording artist in the Ottoman-Greek diasporic community, recording for just ten years before falling silent until his death in 1970. In this early recording, issued by an independent Armenian label in New York, the stark instrumentation (Poulos himself played the oud) creates a surprisingly modern backdrop for his arresting, emotional voice as he sings a lament of unrequited love, full of ancient, stark imagery like flames, clouds, and darkness. “Kamomatou” (lit. mischief-maker) can be translated as coquette or temptress, a woman who makes hay of men, and it’s been used frequently as a title in twentieth-century Greek songs.

18. Miss Indubala: “Ore Majhi Tori Hetha”

It’s virtually impossible to fit most Asian recording activity into the models I’ve been building of emergent Western popular musics; this recording by a young woman who would, a decade later, become one of the early stars of Bollywood, both on screen and in playback recording, was not so much a remarkable record in its moment as it is a historical marker, a signpost on the road to emergent modernism. The droning backdrop of the harmonium, introduced to the subcontinent by Victorian colonizers and still despised by classical purists in the early 20th century, is one element of modernity: another is the parenthetical (Jangla) on the label, indicating that the performance is a combination of two or more traditional ragas. The third is Indubala Devi herself, trained in the vanishing courtesan-singer tradition of Kolkata, granting herself immortality by saying her name on record.

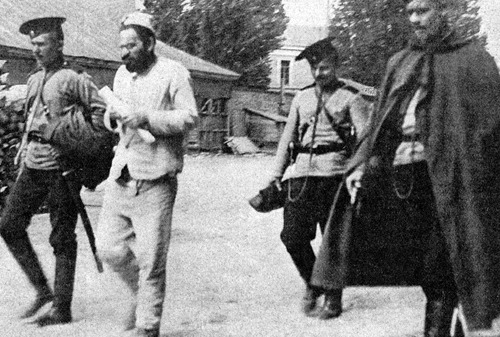

19. Jacob Gegna: “A Tfileh Fun Mendel Beilis”

In 1911, the body of a young boy was found mutilated on the outskirts of Kiev. Authorities arrested a local factory superintendent on suspicion of his having murdered the child in a secret Jewish blood ritual. After Mendel Beilis insisted on clearing his name, refusing a general clemency for convicted felons, his trial was one of the sensations of the late Tsarist era. The most infamous blood libel of the twentieth century swept up honest investigators and reporters who were threatened with dismissal or worse for defending the innocent man; Beilis was finally acquitted after two years of a horrific media circus, followed particularly closely by the millions of Jewish immigrants in the United States. Jacob Gegna, a violinist who had himself immigrated from the Ukraine the following year, cut a single record in 1921, including this moving tribute to the innocent Beilis.

20. Michael Coleman: “The Shaskeen”

Traditional Irish music has rarely taken up much space in these pages, and will continue to do so; my emphasis on novelty, hybridity, and pop ethics over tradition, purity, and folk ethics means that there’s rarely much space for purely local traditions, no matter how sentimentally widespread. Still, I have two ears and a heart. Probably the most influential traditional Irish musician of the twentieth century, Michael Coleman was a remarkable exponent of the Sligo fiddle tradition, playing fast-paced, polyphonic reels that allow him and his piano accompanist to sound like a full band. “The Shaskeen” was one of his first records, a corruption of the Irish seisgeann or marshland, and its sheer velocity makes plain the hypothesis that American vernacular music gets its funk from its African heritage and its recklessness from its Irish. And in December 1921, Ireland was free.

21. Antonio and Luigi Russolo: “Corale”

Eight years after Luigi Russolo’s landmark Futurist manifesto L’arte dei Rumori, in which he theorized an industrial, electronic “art of noises” that would come to replace the limited sonic palette of the traditional orchestra, a solitary 10-inch record was issued which combines his brother Antonio’s conventional orchestral pomp with the roar and howl of the Intonarumori, acoustic instruments of Luigi’s design that produced atonal snarls of noise by vibrating strings at different frequencies, amplified by a drum. It is an explosion of the avant-garde into the safe commercial marketplace of the recording industry, and it was followed by years -- even decades -- of silence. It will not be for another thirty years that further experiments in using pure noise as music become commonplace, by which time the whole structure of recording will have been transformed. But here in the 21st century, Russolo was right.

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

Fanny Brice Quotes

Are you interested in famous Fanny Brice quotes?

Here is a collection of some of the best quotes by Fanny Brice on the internet.

About Fanny Brice

Fania Borach (October 29, 1891 – May 29, 1951), known professionally as Fanny Brice, was an American illustrated song model, comedian, singer, theater and film actress who made many stage, radio and film appearances and is known as the creator and…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

FANNY BRICE, She won hearts on the Vaudeville Circuit, the Broadway stage, and on the big and small screens

FANNY BRICE, She won hearts on the Vaudeville Circuit, the Broadway stage, and on the big and small screens

Fania Borach, a.k.a. Fanny Brice. October 29, 1892 (New York City, NY) – May 29, 1951 (Hollywood, CA) Star of radio, television, stage (mainly the famed Ziegeld Follies), screen. Comedienne. Chanteuse. Though a Yiddish accent was her signature shtick*, Franny Brice didn’t speak the language. “I breathed and ate and lived theatre — in my neighborhood were all the nationalities of all of Europe.…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

Jane Austen’s “Fanny”

Q: Where do you stand on the debate in academia over whether Jane Austen winkingly used the name “Fanny Price” for her Mansfield Park heroine?

A: There’s no chance that Jane Austen was slyly winking at her readers when she used that name in Mansfield Park (1814).

The British use of “fanny” to mean the female genitalia (here in the US it means the buttocks) didn’t appear until Austen had been dead for 20 years.

And if she had been familiar with this use of “fanny,” she wouldn’t have used it for such a shy, upright, and conscientious character as Fanny Price.

The feminine name “Fanny,” a diminutive of “Frances,” was very common in England at the time Austen was writing. Before the slang usages came along, “Fanny” was no more suggestive than “Annie.”

“Frances” was the feminine version of the men’s name “Francis,” and it used to be very popular in both Britain and the United States.

Many famous and admired women were officially named “Frances” and known by the pet name “Fanny” from the 16th through the early 20th centuries.

Popular authors included Fanny Burney (1752-1840), and Fanny Trollope (1779-1863), Anthony’s mother. Well-known actresses included Fanny Kemble (1809-93) and Fanny Brice (1891-1951).

All of them had been given the formal name “Frances” except for Brice, who was originally named Fania Borach.

However, “Fannie” was the original name of the American cooking expert and food writer Fannie Farmer (1857-1915). Her name was borrowed with a different spelling in 1919 by the candy company Fanny Farmer.

In his book Names and Naming Patterns in England, 1538-1700, Scott Smith-Bannister writes that “Frances” held a mean ranking of 17.8 in a selected list of women’s names that were popular during that 162-year period.

At its peak during that period, “Frances” was ranked 13, Smith-Bannister says. (In case you’re interested, the names generally ranked ahead of Frances in Smith-Banister’s statistics were Elizabeth, Mary, Anne, Margaret, Jane, Alice, Joan, Agnes, Catherine, Dorothy, Isabel, Elinor, and Ellen.)

In “New Influences on Naming Patterns in Victorian Britain,” a 2016 paper, Amy M. Hasfjord classifies “Frances” and “Fanny” among England’s “classic” names.

Her statistical ranking places “Frances” 13th among names given to girl babies born between 1825 and 1840.

However, Hasfjord says both “Frances” and “Fanny” dropped in popularity during the period from 1885 to 1900.

In the United States, meanwhile, surveys of the popularity of “Fanny” show that the use of the name dwindled from a peak in 1880 to relatively uncommon in 1940.

In both cases—British and American usage—it seems that the name “Fanny” dropped in popularity just as the slang word “fanny” increased in common usage.

In British English, “fanny” came to mean “the vulva or vagina” in the late 1830s, according to The Random House Historical Dictionary of American Slang.

Jonathan Lighter, author of the slang dictionary, cites a collection entitled Bawdy Songs of the Music Hall (1835-40): “I’ve got a little fanny / That with hairs is overspread.”

The Oxford English Dictionary’s earliest example is from an 1879 issue of a pornographic magazine published in London, The Pearl: “You shan’t look at my fanny for nothing.”

And a British slang dictionary published in 1889 defined “fanny” as “the fem. pud.” (the female pudenda).

This genital usage is “always rare” in the US, Random House says. As an exception, both the OED and Random House cite the American writer Erica Jong, who used it in her novel Fanny (1980):

“ ‘Madam Fanny,’ says he, obliging me, but with the same ironick Tone. ‘D’ye know what that means in the Vulgar Tongue? … It means the Fanny-Fair … the Divine Monosyllable, the Precious Pudendum.”

However, Jong’s novel is an inventive retelling of John Cleland’s bawdy English classic Memoirs of a Woman of Pleasure (1748-49), popularly known as Fanny Hill after its main character.

We suspect that Jong’s imaginative take on Fanny Hill as well as speculation, since debunked, by the slang etymologist Eric Partridge may be responsible for the myth in academia that “fanny” meant the vagina in Cleland’s time.

In the original, 1937 edition of his slang dictionary, Partridge wrote that the use of “fanny” for the “female pudenda” was from “ca. 1860,” but was “perhaps ex Fanny, the ‘heroine’ of John Cleland’s Memoirs of Fanny Hill [sic], 1749.”

However, the 2015 edition of Partridge’s dictionary notes that Fanny Hill’s “publication in 1749 is about a hundred years before ‘fanny’ came to be used in this sense.” (From The New Partridge Dictionary of Slang and Unconventional English, edited by Tom Dalzell and Terry Victor.)

Two other slang dictionaries—those by Lighter and Jonathon Green—call the reader’s attention to Fanny Hill but date the slang usage from the mid-1830s or later.

So why mention Fanny Hill in connection with the usage? The only apparent reason is that the novel’s leading character is promiscuous and is named “Fanny.” Cleland might just as well have called his protagonist “Eliza Hill.”

Nevertheless a handful of academic writers have strained to establish an 18th-century history for the usage, based on guesswork or intuition from hindsight. Their claims have been often repeated, despite the lack of any direct evidence.

A pair of literary scholars demolished their case piece by piece in 2011.

“In fact the evidence is to the contrary,” Patrick Spedding and James Lambert write in their paper “Fanny Hill, Lord Fanny, and the Myth of Metonymy,” published in the journal Studies in Philology.

They write, for example, that the terms “Fanny Fair” and “Fanny the fair” were used in 18th-century songs, “but never in an obscene context or as a synonym for vagina.”

We won’t detail their arguments, but they painstakingly document actual historical uses of the term and conclude that “fanny” was not used as a sexual term until 1837, citing the same book of music-hall songs mentioned above.

“Consequently,” they write, “it is highly unlikely that any of the fictional Fannys were named with the intention of suggesting the female sexual organs, however specified or identified (vagina, genitalia, pudenda, vulva, mons veneris, or mons pubis), or the male or female buttocks.”

“Current usage rather than eighteenth-century usage is the basis of the interpretation of fanny as a sexual term,” they write.

The milder, American sense of “fanny,” meaning the derrière, apparently dates from World War I, according to Random House. Here is the slang dictionary’s earliest example:

“They made us all get in a circle and stoop over while a guy ran around and hit us on the—never mind where—with a strap—I believe they call the game ‘Bat the Fanny’ and they sure did bat me.” (From a diary entry in a regimental history, 12th U.S. Infantry, 1798-1918, published in 1919.)

The OED’s earliest example is from the hit Broadway play The Front Page (1928), by Ben Hecht and Charles Macarthur. Here’s the OED citation, which we’ve expanded for context:

“KRUGER. (To MOLLIE, who is in the swivel chair in front of the desk) What’s the idea, Mollie? Can’t you flop somewhere else?

“MURPHY. Yah, parking her fanny in here like it was her house.”

This milder usage soon caught on in Britain. The term was used in the same way by the British playwright Noël Coward in Private Lives (1930): “You’d fallen on your fanny a few moments before.”

Subsequently, the OED has examples of the “buttocks” sense of the word by both British and American writers.

Here’s the American poet Ezra Pound in The Pisan Cantos (1948): “And three small boys on three bicycles / smacked her young fanny in passing.”

And here’s the British novelist Nevil Shute in Trustee From the Toolroom (1960): “I’d never be able to think of John and Jo again if we just sat tight on our fannies and did nothing.”

In short, although there are exceptions, the OED still characterizes the “fanny” that means genitals as “chiefly British English” and the one that means the butt as “chiefly US.”

In case you’re wondering, the OED also labels the noun “fanny pack” (first recorded in 1971) as a North American usage, the equivalent of the British “bumbag” (1951).

Oxford’s definition, found under “bumbag,” is “a small bag or pouch incorporated in a belt worn round the waist or across the shoulder (orig. designed for skiers and worn at the back).”

A similar term, “fanny belt” was in American use almost a decade before “fanny pack” and today means the same.

Oxford’s earliest citation is from the journal American Speech in 1963, when the term had a more limited definition: “Fanny belt … slang for the belt on which ski patrol men carry their first aid kit. A term used by ski patrols.”

Help support the Grammarphobia Blog with your donation.

And check out our books about the English language.

from Blog – Grammarphobia http://www.grammarphobia.com/blog/2017/02/fanny.html

0 notes

Text

29 maggio … ricordiamo …

29 maggio … ricordiamo …

#semprevivineiricordi #nomidaricordare #personaggiimportanti #perfettamentechic #felicementechic #lynda

2015: Betsy Palmer, nome d’arte di Patricia Betsy Hrunek, attrice statunitense. (n. 1926)

2014: Karlheinz Böhm, conosciuto anche col nome di Carl Boehm, è stato un attore austriaco. (n. 1928)

2013: Franca Rame, attrice teatrale, drammaturga e politica italiana. (n. 1929)

2013: Françoise Blanchard, attrice e doppiatrice francese. (n. 1954)

2012: Renzo Gallo, è stato un cantautore, cabarettista,…

View On WordPress

#29 maggio#Betsy Palmer#Carl Boehm#Coral Browne#Delma Byron#Dennis Hopper#Diego Pozzetto#Edward G. Ross#Edwin G. Ross#Fania Borach#Fanny Brice#Françoise Blanchard#Franca Rame#Gladys Louise Smith#Harvey Korman#Inge Landgut#John Barrymore#John Sidney Blyth#Karlheinz Böhm#Lou Kamante#Lu Kamante#Lu Kanante#Luciano Rossi#Mary Pickford#Miranda Campa#Morti 29 maggio#Natale Cirino#Olga Vittoria Gentilli#Olimpia Di Nardo#Patricia Betsy Hrunek

1 note

·

View note