#Eric giacometti

Text

0 notes

Text

Partageons mon rendez-vous lecture #18-2023 & critiques

Voici ma critique littéraire sur Livres à profusion.

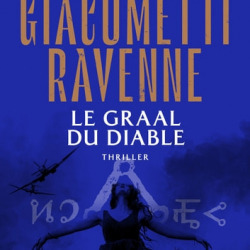

Le Graal du Diable d’Eric Giacometti et Jacques Ravenne

Le graal du diable de Giacometti et Ravenne – Editions JC Lattès

En lecture, une Masse Critique Babelio, Objectif : Forces Spéciales de Matt

Objectif : Forces spéciales

Matt (II)

tous les livres sur Babelio.com

Présentation de l’éditeur :

Intégrer les forces spéciales, tel est…

View On WordPress

#LEGRAALDUDIABLE#SAGADUSOLEILNOIR#avis Eric Giacometti#AVIS LE GRAAL DU DIABLE#AVIS LE GRAAL DU DIABLE D&039;ERIC GIACOMETTI#AVIS LE GRAAL DU DIABLE D&039;ERIC GIACOMETTI ET JACQUES RAVENNE#AVIS LE GRAAL DU DIABLE DE JACQUES RAVENNE#avis romans eric giacometti#avis romans jacques ravenne#AVIS SAGA DU SOLEIL NOIR#AVIS SAGA DU SOLEIL NOIR ERIC GIACOMETTI#AVIS SAGA DU SOLEIL NOIR JACQUES RAVENNE#Eric Giacometti#Jacques Ravenne#LE GRAAL DU DIABLE#LE GRAAL DU DIABLE D&039;ERIC GIACOMETTI#LE GRAAL DU DIABLE D&039;ERIC GIACOMETTI ET JACQUES RAVENNE#LE GRAAL DU DIABLE DE JACQUES RAVENNE#romans eric giacometti#romans jacques ravenne#SAGA DU SOLEIL NOIR#SAGA DU SOLEIL NOIR ERIC GIACOMETTI#SAGA DU SOLEIL NOIR JACQUES RAVENNE

0 notes

Text

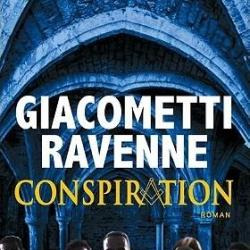

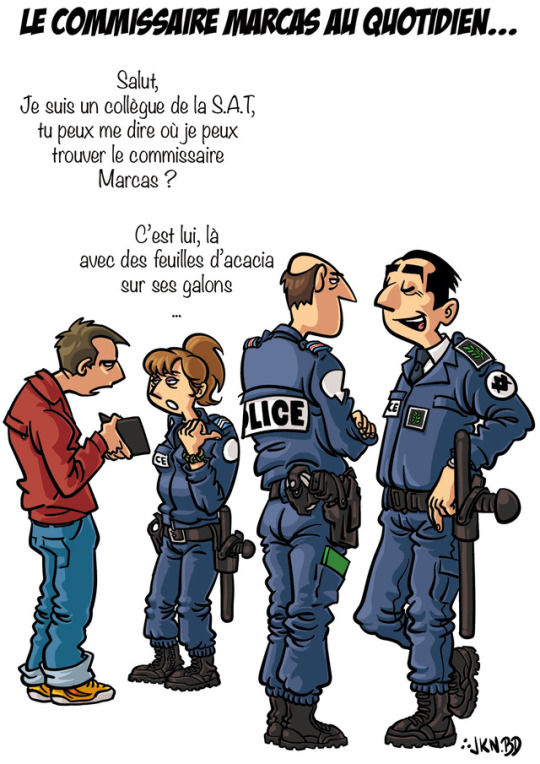

CONSPIRATION (Giacometti & Ravenne)

Résumé

De la France aux États-Unis, Marcas, mis sur la touche par sa hiérarchie, va devoir retrouver un secret qui hante l'histoire de France et dont la possession peut détruire les démocraties occidentales. Deux siècles plus tôt, en pleine Révolution française, l'inspecteur Ferragus présent dans les Illuminati est entraîné dans une implacable course contre la montre pour démasquer le groupe occulte qui veut s'emparer du même secret. Au coeur de ce secret, le pouvoir absolu.

Mon avis

Je dois avoir lu gentillement la plupart des enquêtes d’Antoine Marcas à force, ce ne fut pas le meilleur, mais pas le plus mauvais non plus.

J’ai apprécié la présence du policier Annibale Ferragus, dans le contexte post révolution française, où l’alternance période présente et période ancienne donne un bon tempo au polar. De plus, on est sur du polar purement ésotérique, théorie du complot, règne mondial, skull and bones, tout y est pour donner un mélange savoureusement complotiste.

Ce qui a donné une lecture en demi-teinte c’est finalement le commissaire Antoine Marcas lui-même, qui ne semble pas savoir gérer le quotidien. Le mec peut combattre le crime, trouver le trésors des templiers et bien d’autres en restant un personnage crédible. Par contre, lorsque monsieur est largué par sa copine et a des problèmes au niveau professionnel, j’ai pas eu l’impression d’avoir affaire à un humain lambda, plus un genre de protagoniste Marvelesque et caricatural.

En bref, une chouette lecture, un bon page-turner, mais pas extraordinaire.

0 notes

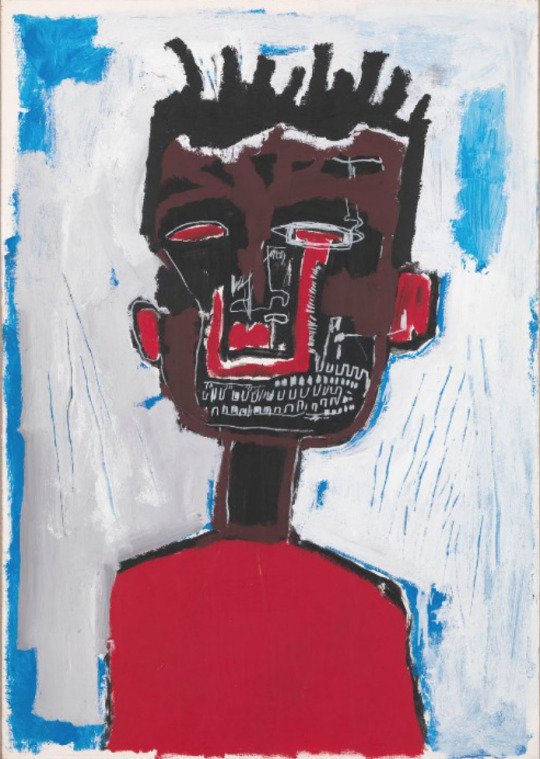

Photo

Alberto Giacometti (1934)

Image: Eric Philippe

34 notes

·

View notes

Text

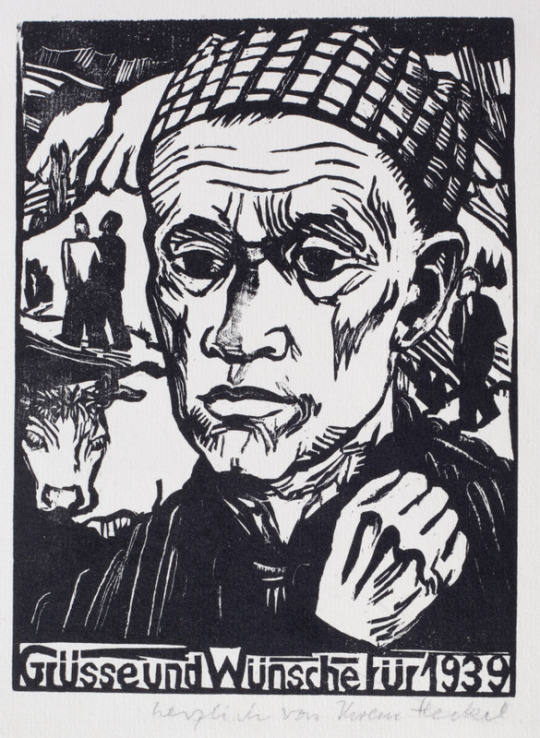

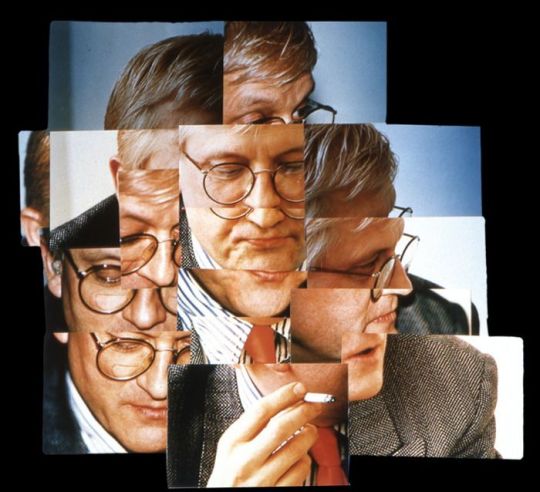

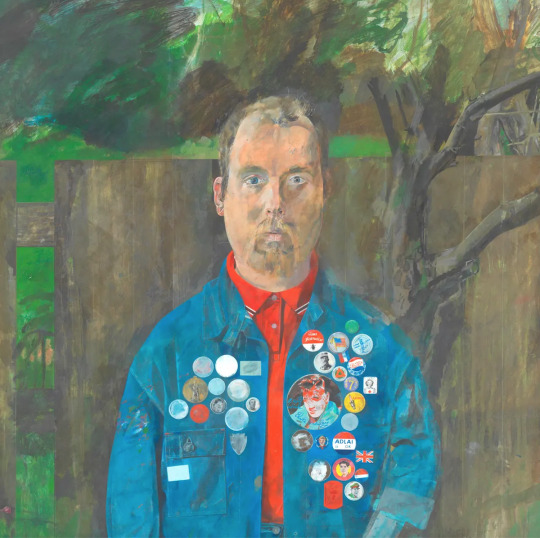

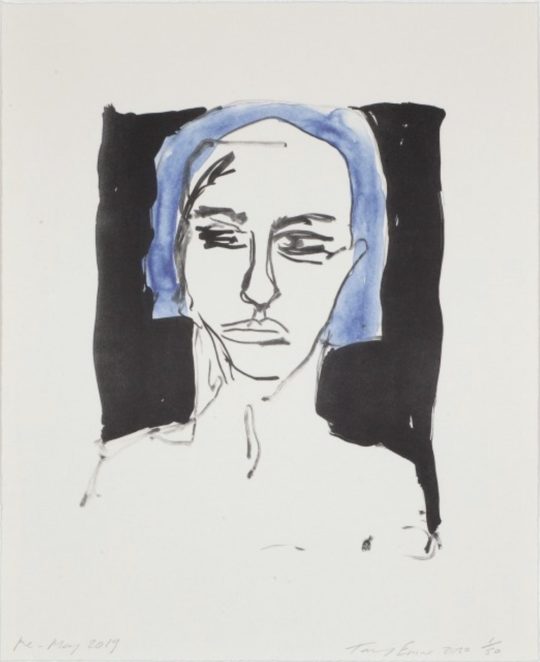

Me, Myself, I: self portrait

Make an image that is a representation of how you look.

Any media, and size. Paint, collage, stitch, print, photography, mixed media.........

Jean Michael Basquiat, Eric Heckel

Cindy Sherman, David Hockney

Peter Blake, Tracey Emin

Alberto Giacometti, Andy Warhol

Francis Bacon, Marc Quinn

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

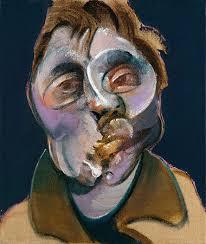

Francis Bacon

https://www.artsy.net/article/artsy-editorial-francis-bacon

https://www.francis-bacon.com/artFrom a small London studio littered ankle-deep with source material, bottles of fine champagne, and a cacophony of paint splatters,

Francis Bacon

conjured some of the most innovative and, as art critic Robert Melville once put it, “satanically influential” paintings of the 20th century. His canvases writhe with fleshy, screaming, contorted figures, from popes and famed art-historical subjects to friends and ill-fated lovers. His searing work embodies a host of post-war cultural anxieties, as well as Bacon’s personal demons and obsessions.

But what was this mighty, enigmatic painter’s secret to creating such spellbinding imagery—and, all the while, upholding his status as king of the bon vivants? Below, we pull back the curtain on who Bacon was, what motivated his deeply affecting paintings, and why their sulfurous power won’t be fading anytime soon.

Who Was Francis Bacon?

Bacon was a complex man whose work was informed by a tangled web of intense relationships, art-historical fixations, and a fair number of vices. Born in Dublin in 1909 to a domineering father, Capt. Anthony Edward Mortimer, and his much younger wife, Christina Winifred Firth, Bacon was derided as a “weakling” and, as legend has it, horse-whipped by his father during his youth due to issues with chronic asthma. At 17, he was kicked out of the family home for good when he was discovered trying on his mother’s underwear.

Francis Bacon

Three Studies for Self-Portrait, 1976

Richard Gray Gallery

But despite (or perhaps because of) his asthmatic bouts and the abuse he endured, Bacon was strong-willed and resilient, with the constitution of a bull. He drank, ate, gambled, loved, and painted with such voraciousness that he rarely had time for sleep; two to three hours a night was typical. Through this haze of debauchery and hard living, and bolstered by deep friendships and aesthetic obsessions, Bacon produced a cascade of paintings that were not only disturbingly beautiful, but also boldly original. His shocking work galvanized the group of painters surrounding him in mid-century London (the “School of London”) and eventually influenced several generations of artists to come, includingDamien Hirst, Jenny Saville, and Jake and Dinos Chapman, to name just a few.

What Inspired Him?

After Bacon was jettisoned from his family home, he embarked on a series of European escapades that opened his eyes to art and design, not to mention other earthly pleasures, like sex and wine. Several works he encountered during his travels made a lasting impact on his work and wouldn’t leave his mind until his death in 1992.

While studying French near Chantilly in 1927, he happened upon

Poussin

’sgreat Massacre of the Innocents (1628–29) and was struck by the emotional agony of the scene, embodied forcefully in the screaming maw of a mother whose child is about to be killed. Later that year, he picked up a book detailing diseases of the mouth, and not long after that, he watched Sergei Eisenstein’s 1925 film Battleship Potemkin, which features a scene of a howling, bloodied nurse—an image permanently tattooed on his mind. Around that time, on a trip to Paris, he was also introduced to

Picasso

’searly figurative drawings. All these run-ins provided Bacon with his initial art education (he was never formally trained) and went on to influence his unique approach to rendering the human body as a malleable—and, at times, grotesque—vessel of raw human feeling.

THREE STUDIES FOR FIGURES AT THE BASE OF A CRUCIFIXION

1944

Oil and pastel on fibreboard

approx. Triptych: Each panel: 37 x 29 in. (94 x 74 cm) irregular

The wide-open mouth would later materialize in some of the painter’s greatest canvases: his series of wailing popes, which he toiled over from 1949 until 1971. They show blurred, bethroned men caught in the act of an intense and seemingly eternal scream that, as Bacon biographer Michael Peppiatt has said, might have referred simultaneously to the militaristic orders of Bacon’s father, the raging rows between Bacon and his tortured lover Peter Lacy, or more simply, to a cry of fear or the climax of a body-quaking orgasm. This was the rare power of Bacon’s work: fusing a range of references into a Frankenstein’s monster of a whole, a beast shuddering with frustration, tension, and countless other, subtler emotions.

Bacon’s “Popes” also reveal another influence:

Velázquez

’s Portrait of Pope Innocent X (1650), a painting Bacon became so infatuated with that he admitted to having a “crush” on it. Time and time again, Bacon would rework his own version of the masterpiece, although, interestingly, he refused to see the painting in person when he finally made a trip to Rome. He was embarrassed, he told Peppiatt, of his many “stupid” manipulations of the piece.

Alongside the many other great artists (Giacometti, Van Gogh, and Matisse among them) who influenced Bacon, the painter also looked for creative guidance in the work of writers and poets—namely Racine, Baudelaire, and Proust. He was attracted to their ability to pare down the complexities of human existence into succinct lines and phrases; he sought to do the same with the arresting figures rooted at the core of his canvases.

THREE STUDIES FOR A CRUCIFIXION

1962

Oil on canvas

Triptych: Each panel: 78 x 57 in. (198.1 x 144.8 cm)

How Did He Work?

Reproductions of Bacon’s inspirations—like the Massacre of the Innocents, along with tattered photos of wild animals, Egyptian talismans, and more—ended up in a soupy jumble on the floors of the many studios he occupied over the course of his career. The exuberant mess was accented with paint and the occasional vestiges of parties he hosted after a long night of carousing through London’s drinking clubs and gambling houses. One of Bacon’s friends, the painter

Graham Sutherland

, once described Bacon’s early Cromwell Place studio as “a large chaotic place, where the salad bowl was likely to have paint on it and the painting to have salad dressing on it.”

But for all his decadence, Bacon was also extremely dedicated, with his own brand of regimentation. “You have to be disciplined in everything, even in frivolity,” he was known to have said. “Above all in frivolity.” Indeed, his passion for enthusiastic and prolonged socialization seemed to fuel his work. Without fail, after a late night of partying, he would wake up at 6 a.m. to paint for several hours in the morning light. Then he’d begin dining and boozing about town, liaising with his many friends and acquaintances, from fellow painters Lucian Freud and Frank Auerbach

to renowned London collectors, such as the Sainsbury’s, to one of his many lovers, like Lacy or Eric Hall. He even went so far as to say that he worked better after a night of drinking: “My mind simply crackles with electricity after one of those evenings,” he once boasted to his friends. “I think the drink actually makes me freer.”

THREE FIGURES AND PORTRAIT

1975

Oil, pastel, alkyd paint and sand on canvas

78 x 58 in. (198.1 x 147.3 cm)

There were some risks to this routine, however. On several occasions, he’d come home late at night, wildly drunk, and decide to “perfect” a painting he’d finished the day before, only to wake up the next morning and discover that he’d ruined it. After one of these episodes, his gallery began collecting his paintings from his studio the moment he finished them.

Bacon’s childhood nanny, Jessie Lightfoot, who lived with the painter until her death in 1951, and his two primary dealers—first Erica Brausen at Hanover Gallery, then Valerie Beston at Marlborough Gallery—also played major roles in helping organize his life and career. When Bacon was struggling financially during his youth, Lightfoot helped him find lovers who would also provide financial support. Brausen became a close friend and confidante; they bonded over their shared homosexuality and appetites for risk-taking (Bacon’s on the canvas; Brausen’s on the walls of her gallery). And starting in 1958, Miss Beston, as she was affectionately called, arranged almost all of Bacon’s day-to-day logistics during his most successful years. She paid his bills, arranged his calendar, made sure his apartment stayed clean, and kept him to his painting schedule. She also kept his canvases out of the trash bin, as he was known to destroy them.

Why Does His Work Matter?

Bacon brought new emotional intensity to the painted figure by representing his subjects—be they friends or mythological figures—as contorted, fleshy, emotionally open masses. He sought to reveal, in all its complexity, what was behind the human facade. “I would like my pictures to look as if a human being had passed between them, like a snail leaving its trail of the human presence…as a snail leaves its slime,” he once said. Indeed, Bacon’s paintings pulsate with the dual energy of human suffering and ecstasy. They seem to unearth, in their blurred limbs and wide-open mouths, our most primal urges. (Scholars have noted that in his canvases from the 1950s, monkeys and men often closely resemble one another.)

Francis Bacon

Triptych – August 1972, 1989

Marlborough Gallery

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

11 Febbraio - "LA NOTTE DEL MALE" Il ciclo del sole nero #2 di Eric Giacometti & Jacques Ravenne

11 Febbraio - "LA NOTTE DEL MALE" di Eric Giacometti Link Amazon https://amzn.to/3biYiDX

Titolo: La notte del male

Serie: Il ciclo del sole nero #2

Autore: Eric Giacometti & Jacques Ravenne

Genere: Thriller

Casa Editrice: Mondadori

Lunghezza: 357 pagine

Prezzo: Ebook €10,99 – Cartaceo €17,00

Data di pubblicazione: 11 Febbraio 2020

ACQUISTA

Sinossi

Novembre 1941. L’esercito del Terzo Reich è alle porte di Mosca e la Germania sta per vincere la guerra.

Per Himmler, capo delle SS, la…

View On WordPress

0 notes

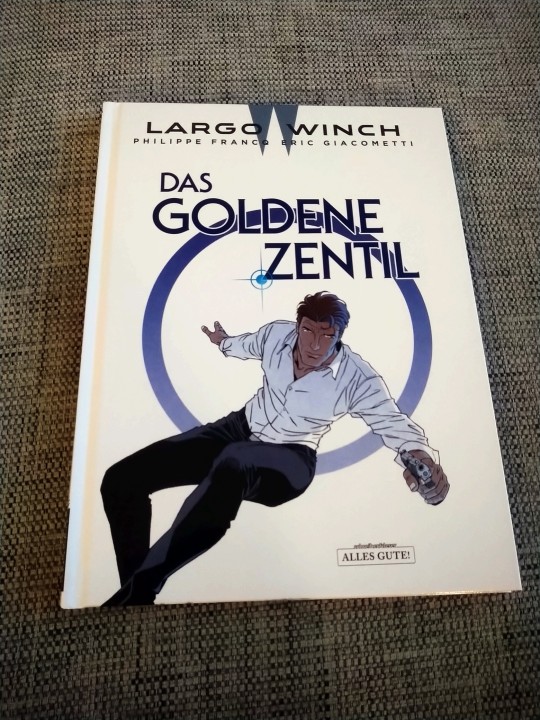

Photo

Hommages au Commissaire Marcas

0 notes

Photo

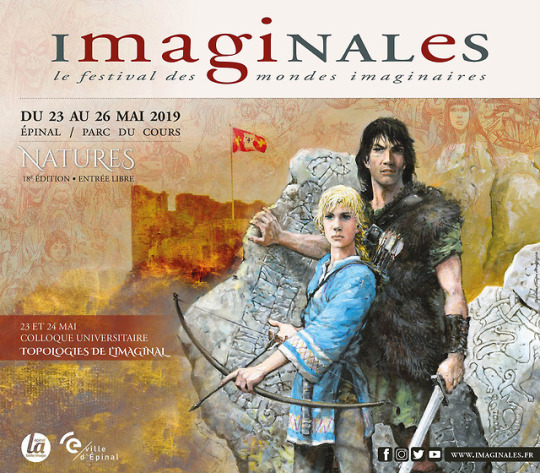

Imaginales: le festival des mondes imaginaires, 18ème édition. 23-26 May 2019, Ville d’Épinal, France. Poster art by Grzegorz Rosiński and Piotr Rosiński, info: imaginales.fr.

From Thursday 23rd to Sunday 26th May, 2019, more than 300 authors and illustrators from all over the world will come to Epinal, in France, for the 18th edition of Imaginales: le festival des mondes imaginaires, one of the first international exposition of Imaginative literature. Artists, novelists and experts in the Fantasy, SF and Fantastic genres will share their stories with a varied and enthusiastic audience. Founded in 2002, the festival is free and open to the public, welcoming more than 40,000 visitors from all over France.

Guest list:

Comics and illustration – Julien DELVAL, Renaud DENAUW, Emmanuel DESPUJOL, Steven DUDA, Gilles FRANCESCANO, Laurent GAPAILLARD, Armel GAULME, Didier GRAFFET, Loïc JOUANNIGOT, Milan JOVANOVIC, Frédéric MARNIQUET, Gilles MEZZOMO, Noë MONIN, Thimothée MONTAIGNE, Frédéric PILLOT, Michel RODRIGUE, Olivier ROMAC, Grzegorz ROSIŃSKI, Piotr ROSIŃSKI, Thierry SÉGUR, Olivier SOUILLÉ, Philippe ZYTKA.

International authors – Alex BELL, Sigridour Hagalin BJÖRNSDOTTIR, Peter BRETT, Anders FAGER, Mark HENWICK, Vic JAMES, S.T. JOSHI, Hildur KNÚTSDÓTTIR, Graham MASTERTON, Sam J. MILLER, Christopher PRIEST, Sofia SAMATAR, Johanna SINISALO.

French authors – Christophe ABAS, Sandrine ALEXIE, Nicolas ALLARD, Mel ANDORYSS, Jean-Pierre ANDREVON, Jacques BARBÉRI, Isabelle BAUTHIAN, Robert BELMAS, Paul BEORN, Karim BERROUKA, Georges BERTIN, Chloé BERTRAND, Pierre BORDAGE, Béatrice BOTTET, Nicolas BOUCHARD, Clément BOUHÉLIER, Charlotte BOUSQUET, Fabienne BRUGERE, David BRY, Sabrina CALVO, Nicolas CARTELET, Fabien CERUTTI, Fabien CLAVEL, Guy COSTES, Alain DAMASIO, Grégory DA ROSA, Nathalie DAU, Lionel DAVOUST, Nicolas DEBANDT, Romain DELPLANCQ, Jérôme DIDELOT, Julie de LESTRANGE, Marie-Charlotte DELMAS, Jean-Laurent DEL SOCORRO, Patrick K DEWDNEY, Romain D'HUISSIER, Victor DIXEN, Sara DOKE, Catherine DUFOUR, Jean-Claude DUNYACH, Silène EDGAR, Manon FARGETTON, Estelle FAYE, Franck FERRIC, Fabien FERNANDEZ, Élise FISCHER, Alexis FLAMAND, Célia FLAUX, Victor FLEURY, Jean-Pierre FONTANA, Isabelle FOURNIÉ, Thomas GEHA, Alison GERMAIN, Eric GIACOMETTI, Régis GODDYN, Marie-José GONAND, Alain GROUSSET, Lauric GUILLAUD, Colin HEINE, Johan HELIOT, Loïc HENRY, Ariel HOLZL, Raymond ISS, Jean-Philippe JAWORSKI, Gabriel KATZ, Florian KIEFFER, Katia LANERO ZAMORA, Gilles LAPORTE, Camille LEBOULANGER, Fabienne LELOUP, Christian LÉOURIER, Jérôme LEROY, Érik L'HOMME, Jean-Marc LIGNY, Méropée MALO, Eric MARCHAL, Jean-Luc MARCASTEL, Johanna MARINES, Jean MARIGNY, Danielle MARTINIGOL, Xavier MAUMÉJEAN, Patrick McSPARE, Hélène P. MÉRELLE, Sylvie MILLER, Vincent MONDIOT, Pierre PEVEL, Betty PICCIOLI, Stefan PLATTEAU, Jean PRUVOST, Jacques RAVENNE, Michael ROCH, Carina ROZENFELD, Éric SANVOISIN, Stéphane SERVANT, Floriane SOULAS, Charles SUZANNE, Ketty STEWARD, Rachel TANNER, Arthur TÉNOR, Philippe TESSIER, Nicolas TEXIER, Christophe THILL, Jean-François THOMAS, Jean-Christophe TIXIER, Adrien TOMAS, Jean-Michel TRUONG, Estelle VAGNER, Laurence VANIN, Cindy VAN WILDER, Claude VAUTRIN, Flore VESCO, Frédéric VINCENT, Frédérique VOLOT, Philippe WARD, Aurélie WELLENSTEIN, Georges ZARAGOZA.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Le graal du diable d'Eric Giacometti et Jacques Ravenne

Le graal du diable de Giacometti et Ravenne – Editions JC Lattès

Le graal du diable d’Eric Giacometti et Jacques Ravenne, présentation

Une femme, Nada la Noire, est à l’origine de massacres qui font peur, à l’été 1944 dans le territoire du Banat. Elle assassine toute une famille et laisse une petite fille survivante, Inge.

C’est la déroute pour l’armée allemande.

Paris, la milice procède à de…

View On WordPress

#legraaldudiable#sagadusoleilnoir#avis Eric Giacometti#avis Le graal du diable#avis Le graal du diable d&039;eric giacometti#avis Le graal du diable d&039;Eric Giacometti et Jacques Ravenne#avis Le graal du diable de jacques ravenne#avis romans eric giacometti#avis romans jacques ravenne#avis saga du Soleil noir#avis saga du Soleil noir eric giacometti#avis saga du Soleil noir jacques ravenne#Eric Giacometti#Jacques Ravenne#Le graal du diable#Le graal du diable d&039;eric giacometti#Le graal du diable d&039;Eric Giacometti et Jacques Ravenne#Le graal du diable de jacques ravenne#romans eric giacometti#romans jacques ravenne#saga du Soleil noir#saga du Soleil noir eric giacometti#saga du Soleil noir jacques ravenne

0 notes

Text

Bad Things

read it on the AO3 at https://ift.tt/2z93O9K

by lonesomewriter

Telepath Yuuri goes to a vampire club to investigate the murders of his colleagues, and meets the god-like club owner, a two thousand years old vampire Viktor.

“Who - who is he?”

“He’s Viktor Nikiforov, the oldest vampire in this club,” Chris answered truthfully, gulping down his drink in one go before continuing. “Probably nearly two thousand years old, I’m not exactly sure. You wanna go talk to him?”

Yuuri’s head was dizzy when he tried to comprehend the fact that someone had really lived for so long. That vampire surely must have a lot of stories to tell. “Is he a bad guy?”

“All vampires are. But he’s definitely someone you wouldn’t want to be in bad terms with.”

You don't need to know anything about True Blood to read this.

Words: 4488, Chapters: 1/1, Language: English

Fandoms: Yuri!!! on Ice (Anime)

Rating: Teen And Up Audiences

Warnings: Creator Chose Not To Use Archive Warnings

Categories: M/M

Characters: Katsuki Yuuri, Victor Nikiforov, Christophe Giacometti, Yuri Plisetsky, Mila Babicheva

Relationships: Katsuki Yuuri/Victor Nikiforov

Additional Tags: Alternate Universe - Vampire, Vampires, True Blood AU, telepath!Yuuri, Vampire!Viktor, basically Viktor is Eric and Yuuri is Sookie

read it on the AO3 at https://ift.tt/2z93O9K

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Bad Things

by lonesomewriter

Telepath Yuuri goes to a vampire club to investigate the murders of his colleagues, and meets the god-like club owner, a two thousand years old vampire Viktor.

“Who - who is he?”

“He’s Viktor Nikiforov, the oldest vampire in this club,” Chris answered truthfully, gulping down his drink in one go before continuing. “Probably nearly two thousand years old, I’m not exactly sure. You wanna go talk to him?”

Yuuri’s head was dizzy when he tried to comprehend the fact that someone had really lived for so long. That vampire surely must have a lot of stories to tell. “Is he a bad guy?”

“All vampires are. But he’s definitely someone you wouldn’t want to be in bad terms with.”

You don't need to know anything about True Blood to read this.

Words: 4488, Chapters: 1/1, Language: English

Fandoms: Yuri!!! on Ice (Anime)

Rating: Teen And Up Audiences

Warnings: Creator Chose Not To Use Archive Warnings

Categories: M/M

Characters: Katsuki Yuuri, Victor Nikiforov, Christophe Giacometti, Yuri Plisetsky, Mila Babicheva

Relationships: Katsuki Yuuri/Victor Nikiforov

Additional Tags: Alternate Universe - Vampire, Vampires, True Blood AU, telepath!Yuuri, Vampire!Viktor, basically Viktor is Eric and Yuuri is Sookie

source http://archiveofourown.org/works/16443800

1 note

·

View note

Photo

13 à table!, Pocket, 5,00€

13 à table ! vous fait revivre votre premier amour pour le meilleur et parfois pour le pire... Tonino BENACQUISTA Philippe BESSON Françoise BOURDIN Maxime CHATTAM François d'EPENOUX Jean-Paul DUBOIS Eric GIACOMETTI Alexandra LAPIERRE Agnès MARTIN-LUGAND Véronique OVALDE Romain PUERTOLAS Jacques RAVENNE Olivia RUIZ Leïla SLIMANI Franck THILLIEZ. Un livre acheté = 4 repas distribués.

(10 Exemplaires)

0 notes

Photo

There are few critics whose work can be read for style alone, and many of the best of those are essentially impressionists or appreciators, like Whitney Balliett and Henry James, idiosyncratic enthusiasts who wrote most often to explicate a new, if sometimes baffled, love. There is a still smaller number who, though passionately opinionated, and as often inclined to damn as praise, manage to turn opinion itself into a kind of art form, who bring to full maturity the moral qualities that hide in violent judgment—qualities of audacity, courage, conviction—and make them come so alive on the page that even if the particular object is seen in a fury, the object seems less interesting than the emotion it evoked, while some broader principle always seems defended by the indignation. Of that still rarer kind, those who come first to mind in English might be Tynan and Shaw on the theatre, Johnson and Jarrell on poetry—and to those names must be added that of Robert Hughes, the Australian (and, latterly, American) art critic, who died this week.

Hughes was many kinds of writers—his hugely popular account of Australia’s founding, “The Fatal Shore,” and his two marvellous books on the cities he loved, “Barcelona” and “Rome,” as well as his biography of Goya were all memorable in their kind—but his fame rightly rested on his thirty or so years of art criticism for Time, and (as he knew) above all on the series and book “The Shock of the New,” still much the best synoptic introduction to modern art ever written. “Nothing if Not Critical” was the title, taken from Iago, that, with mordant self-mockery, he used for a collection of his criticism. And he was a pure critic: both his memoirs and his essays on cities came most alive when he was laying into someone, or pouring praise on something, explaining why one fountain in Rome is more beautiful than another, or why someone he met in the course of life was not beautiful at all. The critics’ work was his work—not disclosing, but describing, fixing, defending, denouncing.

He was, first of all, an artist who just missed having a career as one—as a young man, a cartoonist, his line was said to be ridiculously, fluidly nimble. (There is a wonderful portrait of the young, inspired, angelic-looking Hughes in Clive James’s “Unreliable Memoirs”; indeed, a fine biography might be written of Hughes and James and of the conquest of Anglo-American opinion by Australian energy and unspoiled ambition.) He thought with his hands. When he was defending a notion of permanent value in his mid-nineties “culture war” polemic, “The Culture of Complaint,” it wasn’t with a sniffy reference to Plato or Dante, but through his direct experience as an amateur carpenter, of the practice of planing, sawing, varnishing, and getting it right. There were good tables and bad tables; master carpenters to make them well and miserable ones to make them badly. Craft attempted with passion—that was his critical touchstone. Though it was part of his achievement to help end for all time the notion that novelty in art is in itself a virtue, or that “radicalism” or progress was in any way a reasonable end for creativity, he did so without becoming a reactionary. He had only contempt for the cheap smug conservative taste that risked nothing and tried no new thing, and rooted its suspicions in bile and bad faith. He much preferred a rough-worn and unvarnished table made by passionate hands to a smooth one made to pattern.

His values rose not from some distant imagined past, but from the European modernism that still vibrated with excitement in the Australia of his youth, where no one yet knew it well enough to have grown tired of it. Shaped—some might say scarred—by a resolute Jesuit education, Hughes had as a teen-ager drunk in the images and ideas of that faraway modernism without the least touch of complacent familiarity. (Mechanical reproduction heightened, enhanced its value for him.) In the same way that his contemporary Barry Humphries relished the dandy-art of the eighteen-nineties in a way that few Brits could, or that Clive James kept faith in the power of the heroic couplet to communicate, Hughes believed in modern art with something close to innocence. Although “The Shock of the New” is in many ways an account of the tragedy of modernism—the tragedy of Utopias unachieved, historical triumphs made hollow, evasions of market values that ended by serving them—that tragedy is more than set off by the triumph of modern artists. The thesis of “The Shock of the New,” if such a work can be reduced to one, is that what art lost when it could no longer credibly be a mirror of nature it had gained as a transmitter of lived experience, so that, if the surface of the world had been ceded to the photographic image, the essentials of existence—desire in Picasso, physical ecstasy in Matisse, or the agonized alienation in Giacometti, or all of them at once in Van Gogh—could now be expressed with newfound urgency.

Hughes had an impressive line in indignation, but he was allergic to irony. If he seemed at times out of place in New York it wasn’t by virtue of unorthodox opinions; it was because of a kind of robust, unashamed absence of irony, or meta-awareness, in his work, an absence of sentences placed in inverted quotations or of any despair about the ability of plain speech to achieve plain ends. What he really detested was mannerism, in all its guises, whether the mannerism was the Italian kind that had to be cured by Caravaggio or of the postmodern kind that had yet to be cured at all. If this left him blind to the virtues that mannerism may contain—elliptical thought, the tangle of reference, stylishness—well, who would not want to be in a minority clamoring for truth and passion in a mannerist age?

A radical conservative, a skeptic about the avant-garde in authority who relished the trespasses and achievements of the avant-garde in opposition, he was like Swift, someone who had been driven into reaction only by the excesses of the reforming party in power. He could be rough and even brutal, and, like every critic, his hits and misses are, in retrospect, in about even balance. The odd thing was that, in conversation, he was immune to the habit of turning differences of taste into differences of value. If you explained to him why, say, Jeff Koons or Damian Hirst was not quite the monster he had imagined, he would listen patiently, and then sum up your wavering, hesitant hems and haws in a neat phrase: “Hmmmn…Well, Yes. You’re saying that Koons is to sex what Warhol was to soup cans?” A machine gun burst of laughter. “All right, then!” As with all first-rate writers, the bite, and even occasional bluster, was covering up something, and in Bob’s case this was an enormous vulnerability: to experience, to people, to art. The images that arrive from a quarter century of sporadically intense friendship are not of enemies excoriated but of gentle gestures attempted, of poetry recited and far-distant masterpieces evoked.

Advertisement

“Ah, yes!” was his usual start to a sentence, eyebrows raised in memory followed by the single name of whomever or whatever was about to be quoted or praised or described: “Ah, yes! Auden!” he would say, and then he would give you, from memory, the entire nativity section from “For the Time Being.” (I knew no contemporary writer of any kind who had so much poetry committed to memory; it was part of the rote-learning side of his Jesuit education.)

He was as touching a man as you could hope to meet: when our first son was born, Bob arrived at our loft with arms full of stuffed Australian animals for the newborn. “Now this, you see—this is … the Joey!” he said, showing him the baby kangaroo in its pouch, as though he were describing a work by David Smith. (When, a decade later, he called in the middle of the night, with the news that his only son, Danton, from whom he had long been estranged, but loved all the same, had taken his own life, it was with a desperate, apologetic grief that I have not, and hope never again, to hear equalled.) And, above all, he was a writer: I write this far from both from the Internet and from my own library and yet Hughes’s sentences and phrases stick in my head without either having to be consulted. For all the violence of his disdains, they are mostly phrases of enthusiasm: his insistence that Eric Fischl’s suburban vision “smells of unwashed dog, Bar-B-Q lighter fluid and sperm,” his evocation of the nineteenth-century American landscape artist as “God’s stenographer,” his description of a Morris Louis stain picture as “the watercolor that ate the art world,” or, more profoundly, his explanation of the rococo play of line and painterly weather in a Jackson Pollock and of how it belied his reputation as a mere paint-thrower.

He loved most of all art that danced on an edge between manifest accomplishment and audacity, where a painter managed to bring his or her sheer talent to bear upon the world—and then made the inadequacy of talent alone to bear adequate witness to the world manifest, too. The painters of the London School, which he did so much to raise in the world’s estimation, earned his trust because they echoed his virtues: a love of craft married to an allergy to mere elegance; a feeling for the life-giving qualities of healthy vulgarity and a love of life and the world as it really is, displayed without apology. The smears and howls and broken lines and awkward bodies, the will to truth evidenced in the open, blunt statements of Bacon and Auerbach and Kitaj and Freud—these artists were not so much his best subjects as his truest equivalents.

Criticism serves a lower end than art does, and has little effect on it, but by conveying value it serves a civilizing end. If Bob’s last years were in many ways sad, and at times agonized by the pain that his horrific 1999 automobile accident had left him, the work never stopped, and his affection for those round him never dimmed. Through it all, his mind would rise and a phone call would arrive, and one would race downtown to spend time with him; he would read page after page of whatever he was working on, reciting, in his gruff, warning voice, some masterly combo of verdict, examination, evocation, summary—and then, being Bob, look up, anxious as a schoolboy, and say, “But do you think it’s any good? Do you, really?” It was so much better than good that no good words came to mind. At the end of the evening he would dismiss you, as one raised Catholic and still surprised in the presence of the world, with a simple, “Bless you!” His writing will live as a repository of experience fixed in place by a consciousness tormented but never overthrown, and his memory will survive not as some hanging judge of the museums but as one of the indispensable mavericks of modern humanism.

Illustration by David Hughes, from Robert S. Boynton’s 1997 profile of Robert Hughes.

0 notes

Text

Partageons mon rendez-vous lecture #37-2022 & critiques

Partageons mon rendez-vous lecture #37-2022 & critiques

Voici mes critiques littéraires sur Livres à profusion,

Le Royaume perdu de Giacometti et Ravenne

Le royaume perdu de Giacometti et Ravenne – Editions JC Lattès

La maison sans souvenirs de Donato Carrisi

La maison sans souvenirs de Donata Carrisi – Editions Calmann Lévy

En lecture, une patience d’ange d’Elizabeth George

Une patience d’ange d’Elizabeth George – Editions Pocket

Présentation de…

View On WordPress

#avis Donato Carrisi#avis Jacques Ravenne#AVIS LA MAISON SANS SOUVENIRS#AVIS LA MAISON SANS SOUVENIRS DE DONATO CARRISI#AVIS LE ROYAUME PERDU#AVIS LE ROYAUME PERDU D&039;ÉRIC GIACOMETTI#AVIS LE ROYAUME PERDU D&039;ÉRIC GIACOMETTI ET JACQUES RAVENNE#AVIS LE ROYAUME PERDU DE JACQUES RAVENNE#AVIS LE ROYAUME PERDU GIACOMETTI ET RAVENNE#avis romans Donato Carrisi#avis romans eric giacometti#avis romans jacques ravenne#éditions calmann lévy#calmann lévy éditions#LA MAISON SANS SOUVENIRS DE DONATO CARRISI#LE ROYAUME PERDU D&039;ÉRIC GIACOMETTI#LE ROYAUME PERDU D&039;ÉRIC GIACOMETTI ET JACQUES RAVENNE#LE ROYAUME PERDU DE GIACOMETTI ET RAVENNE#LE ROYAUME PERDU DE JACQUES RAVENNE#romans Donato Carrisi#romans eric giacometti

0 notes

Photo

#1kitap1mekan serimin bugünkü seçkisi HOTEL PIMODON diğer adıyla HOTEL DU LAUZUN 📚 Ünlü fransız yazar Baudelaire’in de yaşadığı ve 17. yy iç mimarisinin en güzel örneği olan bina, Paris’in gözbebeği Ile St. Louis’de yer almakta. 📚 Günümüzde Paris İleri Araştırmalar Merkezi olan binada geçen KAZANOVA TARİKATI, 2 fransız yazar Eric Giacometti ve Jacques Ravenne’in ortak kaleme aldığı mükemmel bir polisiye. 📚 Son günlerde sıkça duyduğumuz corona virüs komplo teorilerinden birinin konu edildiği kitap, özellikle masonluk çevresinde yazılan polise severlerin hoşuna gidecek. #eleganscadisi #kitapkurdu #polisiye #mason #kazanovatarikatı #kitaptavsiyesi #instakitap #gezilecekyerler #paris #sanat #mimari https://www.instagram.com/p/B-E0SSZAyDQ/?igshid=1l2y8li2o880x

#1kitap1mekan#eleganscadisi#kitapkurdu#polisiye#mason#kazanovatarikatı#kitaptavsiyesi#instakitap#gezilecekyerler#paris#sanat#mimari

0 notes