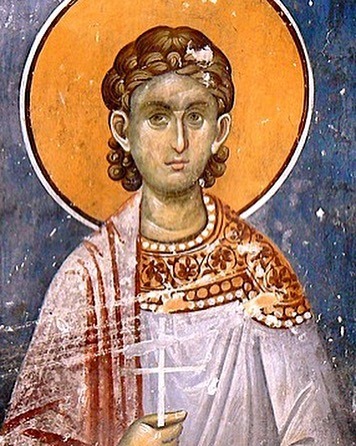

#Emperor Theodosius II

Text

Archaeologists Discovered Roman Floor Mosaics in Bulgaria

Archaeologists discovered floor mosaics with early Christian designs and nearly 800 artifacts in the archaeological reserve of Marcianopolis in Devnya, in the northeastern part of Bulgaria.

The Roman town of Marcianopolis (present-day Devnya) in northeastern Bulgaria appears to have originated as a Thracian settlement. It was later inhabited by Hellenized settlers from Asia Minor and named Parthenopolis.

Roman Marcianopolis was established around 106 CE, following Trajan’s campaigns in Dacia to the north. The settlement was named after his sister, Ulpia Marciana. At the crossroads between Odessos (modern Varna), Durostorum, and Nicopolis ad Istrum, as well as the location of plentiful springs, Marcianopolis became a strategically important settlement.

Diocletian’s administrative reforms in the late third century CE divided Moesia Inferior into Moesia Secunda and Scythia Minor, with Marcianopolis serving as the former’s administrative capital. Marcianopolis experienced its most prosperous period during the middle of the fourth century CE. From 367 CE to 369 CE, the eastern emperor Valens used Marcianopolis as his winter quarters during campaigns against Visigoth incursions in the region. During this time, it served as the Eastern Empire’s temporary capital.

Floor mosaics with early Christian designs were found in the remains of a building. Archaeologists are not yet sure whether it was a public building or it belonged to a rich Roman citizen.

The tentative dating of the mosaics is in the first half of the 4th century AD.

The finds from the current archaeological season in Devnya contain another thousand bronze coins, several clay lamps and two clay vessels, which are awaiting scientific processing and restoration.

During the past archeological season, researchers restored bronze vessels discovered in the 1990s in a brick-walled tomb dating to the late 2nd – early 3rd century.

The vessels had a ritual use and were related to the personality of the person buried, Mosaic Museum director Ivan Sutev said in a statement to BTA.

They are richly decorated and the workmanship is exquisite, he added. The find includes a vessel for pouring liquids as offering to a deity, and a wine jug with a trefoil mouth (oenochoe). A simple kitchen pan was also found along with these. All this leads archaeologists to suggest that a Roman citizen of Marcianopolis may have been laid to rest in the tomb, but that he may have had more specific functions: a soldier, a cook, or even a priest, Sutev said.

Pottery that was discovered in the basilica’s environs during excavations in 2023 has since been restored. Among these are a mortarium vessel for liquids and an exquisite crater-shaped pot for liquids. These were located in the structure with the mosaic floors. Coins from the time of Emperor Theodosius II were also found scattered on the floor.

In 447, Attila’s Huns captured and destroyed Marcionopolis after conquering the entire Balkan Peninsula but failing to capture Constantinople. That is determined by 20 gold coins scattered on the floor of the building being studied. On one side of the coins is an image of Theodosius II, while on the other is the patron goddess of Constantinople. Among the coins discovered during the Marcianopolis excavations were those from the city’s founding in the second century. The latter are dated to the sixth century, around the time of Emperor Justinian.

By Oguz Buyukyildirim.

#Archaeologists Discovered Roman Floor Mosaics in Bulgaria#The Roman town of Marcianopolis#gold#gold coins#roman gold coins#ancient artifacts#archeology#archeolgst#history#history news#ancient history#ancient culture#ancient civilizations#roman history#roman empire#roman art#Emperor Theodosius II

44 notes

·

View notes

Note

So I know my homoiousios vs. homoousios, and my monophysite vs. dyophysite, and my monothelite vs. dyothelite, and how it all led to the Arab caliphates getting a decent navy and winning the Battle of the Masts.

I don't, and I'd love to! (If you feel like it, obviously.) I'm pretty sure the homoiousios one is about, like, the Trinity or something, but beyond that it's all Greek to me.

(At this point, I feel like I owe @apocrypals royalties or something, but I'm getting a weird kick from doing this on Saint Patrick's Day, so let's do this).

I covered the impact of the monophysite vs. dyophysite split and the Battle of the Masts here, so I'll start from the top.

You are quite correct that the homoiousios vs. homoousios split was, like most of the heresies of the early Church, a Cristological controversy over the nature of Christ and the Trinity. This is perhaps better known as the Arian Heresy, and it's arguably the great-granddaddy of all heresies.

The Arian heresy was the subject of the very first Council of the early Church, the Council of Nicea, convoked by Emperor Constantine the Great in order to end all disputes within the Church forever. (Clearly this worked out well.) In part because the Church hadn't really sat down and attempted to establish orthodoxy before, this debate got very heated. Famously, at one point the future Saint Nicholas supposedly punched Presbyter Arius in the face.

What got a room of men devoted to the "Prince of Peace" heated to the point of physical violence was that Arius argued that, while Christ was the son of God and thus clearly divine, because he was created by God the Father and thus came after the Father, he couldn't be of the same essence (homoousios) as the Father, but rather of similar essence (homoiousios). Eustathias of Antioch and Alexander of Alexandria took the opposing position, which got formulated into the Nicean Creed. As this might suggest, Arius lost both the debate and the succeeding vote that followed, as roughly 298 of 300 bishops attending signed onto the Creed. This got very bad for Arius indeed, because Emperor Constantine enforced the new policy by ordering his writings burned, and Arius and two of his supporters were exiled to Illyricum. Game over, right?

But something odd happened: the dispute kept going, as new followers of Arius popped up and showed themselves to be much better at the Byzantine knife-fighting of Church politics. About ten years later, the ever-unpredictable Constantine turned against Athanasius of Alexandria (who had been Alexander's campaign manager, in essence) and banished him for intruiging against Arius, while Arius was allowed to return to the church (this time in Jerusalem) - although this turned out to be mostly a symbolic victory as Arius died on the journey and didn't live to see his readmission.

....and then it turned out that Constantine the Great's son Constantius II was an Arian and he reversed policy completely, adopting the Arian position and exiling anyone who disagreed with him, up to and including Pope Liberius. While the Niceans eventually triumphed during the reign of Theodosius the Great, Arianism unexpectedly became a major geopolitical issue within the Empire.

See, both during their exile and during their brief period of ascendancy within the Church, one of the major projects of the Arians was to send out missionaries into the west to preach their version of Christianity. Unexpectedly, Arianism proved to be a big hit among the formerly pagan Goths (thanks in no small part to the missionary Ulfilas translating the Bible into Gothic), who were perhaps more familiar with pantheons in which patriarchal gods were considered senior to their sons.

While they weren't particularly given to persecuting Niceans in the West, the Ostrogothic, Visigothic, Burgundian, and Vandal Kings weren't about to let themselves be pushed around by some Roman prick in Constantinople either - which added an interesting religious component to Justinian's attempt to reconquer the West.

27 notes

·

View notes

Note

One of the great tragedies of human history, in my humble opinion, is how Christianity was originally good before Constantine got ahold of it. In its early years of 33 CE-313 CE, it was a good and kind and just religion built around uplifting the marginalised peoples of the world and the New Testament is explicitly a socialist text. Yet I look at the Christian churches of today and see nothing about them any of the First Christians would even remotely recognise.

There are a lot of complex and delicate arguments to be had (and indeed, scholars have spent several literal millennia having them) about whether Christianity was totally good before the corrupting influence of those bad Romans aligned it with one of the largest and most culturally significant empires in history -- in which case, of course, its interests became about imposing and maintaining imperial control, often brutally, rather than any fidelity to founding precepts about love and care for others etc etc. In my opinion, this is a considerable oversimplification. From its founding, Christianity was subject to major internal crises and schisms, bitter arguments over what counted as "orthodox" (literally, "true") and what was describable as a heresy and for what reasons. The first few centuries of Christianity pre-Roman Catholicism are hardly a picture of peaceful coexistence, and Christianity was also unusual in the ancient world for its intolerance of competing theologies. The Romans were fairly lax about which local gods their subjects worshiped, as long as they also made sacrifices to Roma, Jupiter, and the other Roman pantheon, as that was felt to be an essential civic duty for the welfare of the Roman state. Thus, the Christians' refusal to honor any gods but their own was viewed not just as a religious defiance, but as a threat to public order and Homeland Security, and of course, it's always easy to scapegoat those kinds of people.

Even before the Romans, however, groups of Christians were viciously attacking other Christians, heretics, Jews, "pagans," Greeks or Hellenes (this was before medieval scholars such as Aquinas embarked on a valiant project to "Christianize" Aristotle and otherwise make the Greek philosophers acceptable to the Catholic canon) and definitely not constantly engaged in pure neighborly philanthropy. There are many options for how it could have developed, whether as a local sect in opposition to the Romans, a religion originally specific to a group of people and geographic region like Judaism, or just merely fractured into competing groups that all viewed each other as the enemy and eventually died out. However, it was additionally unusual in antiquity for its aggressive focus on conversion, and its spread beyond traditional tribal and ethnic groups. It was previously felt that each racial or national group of people had their own gods and those were the ones they were expected to stick with, but since the first few generations of Christians were all converts rather than being born into an established tradition, they were seen as "relinquishing" their previous gods, and this was unusual and possibly dangerous.

Constantine is often positioned as the establisher of Christianity in the Roman Empire, but this is also not quite true. He officially decriminalized Christianity after the increased persecutions of the late second and early third century CE, and may have personally been baptized on his deathbed, but this was also debated and he remained cagey about it during his lifetime. It was also not a straight line of uncontroversially Christian emperors from there; there was a guy named Julian the Apostate in the 360s, who rebuked institutional Christianity and tried to make a return to the Roman gods. However, the tide was generally moving toward Christianity, and in the 430s, the emperor Theodosius II issued the Theodosian Code, one of the original comprehensive legal-civic codes that mandated Christianity as the official religion of the Roman Empire and viewed non-Christians as the same kind of civic threat that Christians themselves had once been. Eventually, after the breakup of the western Roman Empire in 476, Rome -- while no longer the seat of major secular power -- was retained as the seat of religious authority, and became home to the Pope.

As I have written about many times, the legacy of medieval Christianity and medieval Catholicism is very complicated, and takes that reduce it to "the all-powerful church brainwashed everyone everywhere and they always did what it said" are wildly incorrect. It is a deeply flawed institution embedded into deeply flawed human society, and its control was never universal or complete. Indeed, the Catholics would love you to think it was, but the Great Schism of 1054 formalized the split between Greek Eastern Orthodox and Latin Western Catholic rites after centuries of acrimony, and the thirteenth century in particular was a hotbed for challenging and questioning the church (and the growth of new "heresies") in a way not really seen since the original first few centuries. Even in Europe, conversion was slow and patchwork and happened in different regions at different rates, and was always syncretic with local beliefs and magic/folklore traditions. So yes, even as one of the major inheritances of Rome, as Chris Wickham would put it, Christianity was not automatically or unquestioningly superior in medieval Europe. Though of course, it did become so, and allied itself with projects of institutional and generational religious warfare such as the crusades.

Anyway, the minutiae of the early church notwithstanding, it's true that almost invariably, the institutional Catholic church has found itself on the wrong side of history for the past 1700 years or so, and like all religions whose claim to universal and permanent truth means that any attempt to change or modulate its teaching is an existential threat, it has resisted any attempts to scrutinize, analyze, or acknowledge that. Because of Christianity's eventual permanent supremacy in European legal and religious worlds, and its violent exportation to the rest of the world via colonialism and imperialism, its truth-claims have been used to inflict immense systemic and individual suffering. The archconservative elements in the church (of which the recently late Benedict XVI was one), have doubled down on those claims and taken their refusal to modernize as a point of pride, and this is only in regard to Catholics. The churches that I suspect you're talking about, i.e. American evangelical/fundamental churches, owe their intellectual genealogy to Protestantism, and that is a whole OTHER can of worms.

146 notes

·

View notes

Text

Vatican Cityyyyyy!!!!!!!!!! 🇻🇦he’s real and he’s old :)

Vatican City State // Stato della Città del Vaticano // Status Civitatis Vaticanæ

Giovanni D’Amico • he/him • February 11, 1929 • 1,642 years old (71 human years)

Originally born around 380 AD when Christianity was made the empire’s official religion by Emperor Theodosius. Would later, in 754 AD by the Donation of Pepin, be known as the Papal States until year 1870. Finally, in 1929, he would be known as Vatican City.

Vatican City is a multifaceted elderly man. A loving and strict father, one who prefers tough love over a soft and gentle touch— he’s honest about the world and it’s struggles, even to children, and doesn’t sugar coat it when someone needs to be straightened out/intervened. He’s a devoted catholic who was ordained in 1961; if you ask him why he didn’t become a priest earlier, he’ll avoid answering, starting a brand new conversation all together or just walking away without a word. He has his reasons. Don’t underestimate him, however, because of his charming smile and kind air, he can be pretty cunning and even manipulative when he wants to be. His father was the Roman Empire after all.

Vatican City gets along with most people he meets and is pretty optimistic most of the time, much like Veneziano is. But he can lose his temper, or be in frequent bad moods, over small inconveniences in similar ways to Romano. Unlike the boys, he has a very close personal relationship with Switzerland— meaning he can walk onto his property uninvited without being shot at or chased out. This is due to their history since 1506, when Pope Julius II asked the Swiss to provide protection during the Italian Wars.

His relationship with the boys are actually newly built. Before now, his longest and closest interaction with the boys was when they were children. So having more time with them now is a little out of place to Vatican City when last he saw them was when they were teenagers and now they’re fully grown adults. It is still a little difficult to remember that oh yeah Veneziano is no longer a toddler, I shouldn’t be babying him like this. Romano isn’t some kid anymore either, he’s old enough to make his own decisions now. They’re still his kids though so of course he’ll baby them sometimes. His relationship with Seborga is the same as the Italies’— although the boys have noticed he treats Seborga with a softer hand than he did when they were kids. Like Rome often did, he shows favoritism. And Seborga is “allegedly” his favorite.

He walks with a limp, which many are unsure how it was obtained, some assuming it’s France’s fault when he lived in Avignon and jokingly shun him for kicking such a “harmless kind soul”. The real reason he limps is because of a humiliating trip he took down a flight of stairs in 1312, a story he plans to take to the grave. Vatican City uses a sleek wooden cane, however it’s more for the aesthetics than for practical use.

Vatican City claims to be extremely humble and honest, but he does pride himself on his continuous unwavering faith. He doesn’t brag about it though. …..Not often. He’s always looking out to help those around him, however he isn’t actually that good of a listener so sometimes he can totally misread the situation and apply the wrong fix/advice. He’s got a bigger mouth than he does ears.

Hobbies:

Reading

Just barely keeping the house plants alive Gardening

Cooking

Notes :)))))

I made him old as a contrast to the Italies— wanted him to stand out and seem wiser than them without actually being wiser because let’s face it. None of these fuckers are very smart. I can’t decide specifically when he ages so rapidly like this, but I am leaning towards the mid 1700s. He does appear much older than Rome, who, when he fell, was roughly 55-65 human years in appearance(in my headcanon). Also, if I remember correctly, Hima did describe how he thinks Vatican City would look— old and grouchy— which I didn’t remember until like. After I finalized this design 2 years ago 💀 which is awesome! We need more grouchy old men nations! Wrinkles are hot too! /j? even with the grouchiness, I really wanted him to be more like Veneziano, so I kind of split it in half, VC sharing traits with both the Italies.

Final side note that I couldn’t make fit above— yeeeeeah he’s kind of homophobic but at least he’s the type to not voice his disapproval so loudly or tries to force his opinions on others. He kind of just awkwardly and uncomfortably leaves the situation or starts a new conversation if you bring up being queer. Its the topic he’ll avoid, not the person. He’s not transphobic tho, even if he does misuse pronouns sometimes. Well he doesn’t understand nonbinary or genderfluid identities. He’s….. he’s trying at least. I think he actually forgets Romano is a transman though— “My daughter? I have two sons- oooooh yeah. That- no I have two sons now.” Also he’s celibate. Has been for many many years, even before he was ordained.

Please correct me if I got any historical or otherwise facts wrong!

#hetalia#hetalia fanart#hetalia oc#hws vatican city#oc: vatican city#hws veneziano#hws north italy#hws san marino#oc: san marino#hws romano#hws south italy#hws seborga#hws switzerland

44 notes

·

View notes

Text

me, very confidently: I don't actually care about roman emperors except for whatever valentinian and valens had going on, and theodosius. oh, also caligula, of course.

gratian using his half brother as a political proxy puppet, followed by theodosius doing the exact same thing culminating in valentinian ii's likely suicide at the age of 21

me, even more confidently: -- I will be making a dramatized comic about this

#me @ theodosius: the christians may have absolved you of this via propaganda but as a known christian propaganda hater#im going to unabsolve you. god. galla. you should've killed your husband for what he did to your brother

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

List of Roman Emperors and how many future emperors were born during their reign

"?" is for emperors whose birthdate is unclear, they'd be listed under every possible option

Emperors with no known birthdate won't be counted towards any reign

A lot of the reigns overlap (especially after the Empire is divided between east and west) so some emperors are born during the reign of several previous emperors

Republican Era: 2. Augustus, Tiberius

Agustus (40 years): 5. Caligula, Claudius, Galba, Vitellius, Vespasian

Tiberius (22 years): 2. Otho, Nerva

Caligula (4 years): 2. Nero, Titus

Claudius (14 years): 2. Domitian, Trajan

Nero (14 years): 0.

Galba (7 months): 0.

Otho (3 months): 0.

Vitellius (8 months): 0.

Vespasian (10 years): 1. Hadrian

Titus (2 years): 0.

Domitian (15 years): 1. Antoninus Pius

Nerva (1 year): 0.

Trajan (20 years): 0.

Hadrian (21 years): 4. Marcus Aurelius, Lucius Verus, Pertinax, Didius Julianus

Antoninus Pius (23 years): 2. Septimius Severus, Gordian I

Marcus Aurelius (19 years): 3-4. Commodus, Macrinus, Maximunus Thrax?, Pupienus

Lucius Verus (8 years): 2. Commodus, Macrinus

Commodus (13 years): 4-6. Caracalla, Geta, Maximinus Thrax?, Gordian II, Balbinus, Decius?

Pertinax (3 months): 0.

Didius Julianus (2 months): 0.

Septimius Severus (18 years): 6-8. Elagabalus, Severus Alexander, Philip the Arab, Decius?, Trebonianus Gallus, Aemilianus, Valerian, Tacitus?

Caracalla (6 years): 2. Claudius Gothicus, Aurelian

Geta (1 year): 0.

Macrinus (1 year): 0-1. Gallienus?

Elagabalus (4 years): 0-1. Gallienus?

Severus Alexander (13 years): 2-3. Gordian III, Probus, Carus?

Maximinus Thrax (3 years): 0.

Gordian I (1 month): 0.

Gordian II (1 month): 0.

Pupienus (3 months): 0.

Balbinus (3 months): 0.

Gordian III (5 years): 1. Diocletian

Philip the Arab (6 years): 0.

Decius (2 years): 0-3. Carinus?, Maximian?, Constantius I?

Trebonian Gallus (2 years): 0.

Aemilianus (2 months): 0.

Valerian (7 years): 2. Numerian, Galerius

Gallienus (15 years): 1. Licinius

Claudius Gothicus (2 years): 0.

Aurelian (5 years): 2. Maximinus II, Constantine I

Tacitus (7 months): 0.

Florianus (3 months): 0.

Probus (6 years): 0.

Carus (10 months): 0-1. Maxentius?

Carinus (2 years): 0-1. Maxentius?

Numerian (1 year): 0-1. Maxentius?

Diocletian (20 years): 0.

Maximian (21 years): 0.

Galerius (6 years): 0.

Constantius I (1 year): 0.

Severus II (8 months): 0.

Maxentius (6 years): 0.

Licinius (15 years): 4. Constantine II, Constans I, Constantius II, Valentinian I

Maximinus II (3 years): 0.

Constantine I (31 years): 7. Constantine II, Constans I, Constantius II, Julian, Jovian, Valentinian I, Valens

Constantine II (3 years): 0.

Constans I (12 years): 1. Theodosius I

Constantius II (24 years): 2. Gratian, Theodosius I

Julian (2 years): 0.

Jovian (8 months): 0.

Valentinian I (12 years): 1. Valentinian II

Valens (14 years): 2. Valentinian II, Arcadius

Gratian (8 years): 1. Arcadius

Valentinian II (4 years): 0.

Theodosius I (16 year): 2. Honorius, Marcian

Arcadius (13 years): 2. Theodosius II, Leo I

Honorius (29 years): 2. Theodosius II, Leo I

Theodosius II (42 years): 3-4. Valentinian III, Zeno, Anastasius I, Justin?

Constantius III (7 months): 0.

Valentinian III (29 years): 1-2. Zeno?, Anastasius I

Marcian (6 years): 0-1. Justin I?

Petronius Maximus (2 months): 0.

Avitus (1 year): 0.

Majorian (4 years): 0.

Leo I (17 years): 1. Leo II

Libius Severus (4 years): 0-1. Romulus Augustulus?

Anthemius (5 years): 1. Leo II

Olybrius (7 months): 0.

Glycerius (1 year): 0.

Leo II (10 months): 0.

Julius Nepos (6 years): 0.

Zeno (16 years): 1. Justinian I

Basiliscus (2 years): 0.

Romulus Augustulus (10 months): 0.

Anastasius I (27 years): 0.

Justin I (9 years): 0.

Justinian I (39 years): 3. Tiberius II, Maurice, Phocas

Justin II (13 years): 1. Heraclius

Tiberius II (4 years): 0.

Maurice (20 years): 0.

Phocas (8 years): 0.

Heraclius (30 years): 3. Constantine III, Heraclonas, Constans II

Constantine III (3 months): 0.

Heraclonas (9 months): 0.

Constans II (27 years): 1. Constatine IV

Constantine IV (17 years): 1-2. Justinian II, Leo III?

Justinian II (16 years, non-consecutive): 0-1. Leo III?

Leontius (3 years): 0.

Tiberius III (7 years): 0.

Philippicus (2 years): 0.

Anastasius II (2 years): 0.

Theodosius III (2 years): 0.

Leo III (24 years): 1. Constantine V

Constantine V (34 years): 6-7. Leo IV, Constantine VI, Irene, Nikephoros I, Michael I, Leo V?, Michael II

Leo IV (5 years): 0-1. Leo V?

Constantine VI (17 years): 0-1. Staurakios?

Irene (5 years): 0-1. Staurakios?

Nikephoros I (9 years): 0-1. Basil I?

Staurakios (2 months): 0-1. Basil I?

Michael I (2 years): 0-2. Theophilos?, Basil I?

Leo V (7 years): 0-1. Theophilos?

Michael II (9 years): 0.

Theophilos (12 years): 1-2. Michael II, Basil I?

Michael III (26 years): 1. Leo VI

Basil I (19 years): 2. Alexander, Romanos I

Leo VI (26 years): 1-2. Constantine VII, Nikephoros II?

Alexander (1 year): 0-1. Nikephoros II?

Constantine VII (46 years): 3. Romanos II, John I, Basil II

Romanos I (24 years): 2. Romanos II, John I

Romanos II (3 years): 1. Constantine VIII

Nikephoros II (6 years): 1. Romanos III

John I (6 years): 0.

Basil II (50 years): 9. Michael IV, Michael V, Zeo, Theodora, Constantine IX, Michael VI, Isaac I, Constantine X, Nikephoros III

Constantine VIII (3 years): 0.

Romanos III (5 years): 1. Romanos IV

Michael IV (8 years): 0.

Michael V (4 months): 0.

Zoe (2 months): 0.

Theodora (2 years): 0.

Constantine IX (13 years): 1. Michael VII

Michael VI (1 year): 0-1. Alexios I?

Isaac I (2 years): 0-1. Alexios I?

Constantine X (7 years): 0.

Romanos IV (4 years): 0.

Michael VII (6 years): 0.

Nikephoros III (8 years): 0.

Alexios I (37 years): 1-2. John II, Andronikos I?

John II (25 years): 4-5. Manuel I, Andronikos I?, Isaac II, Alexios III, Alexios V

Manuel I (37 years): 2. Alexios II, Theodore I,

Alexios II (3 years): 1. Alexios IV

Andronikos I (2 years): 0.

Isaac II (10 years): 1. John III

Alexios III (8 years): 0.

Alexios IV (6 months): 0.

Alexios V (2 months): 0.

Theodore I (16 years): 0-1. Theodore II?

John III (33 years): 2-3. Theodore II?, John IV, Michael VIII

Theodore II (4 years): 0.

John IV (3 years): 0.

Michael VIII (24 years): 2. Andronikos II, Michael IX

Andronikos II (45 years): 2. Andronikos III, John VI

Michael IX (26 years): 1. Andronikos III

Andronikos III (13 years): 1. John V

John V (50 years): 3. Andronikos IV, John VII, Manuel II

John VI (8 years): 2. Andronikos IV, Manuel II

Andronikos IV (3 years): 0.

John VII (5 years): 0.

Manuel II (34 years): 2. John VIII, Constantine XI

John VIII (23 years): 0.

Constantine XI (4 years): 0.

#possibly the most autistic thing I've done#rome#roman history#you would notice that Alexios III and V were born before Alexios II and IV#and that John VI was born before John V#that's because history is dumb

55 notes

·

View notes

Text

Today in Christian History

Today is Tuesday, October 31st, 2023. It is the 304th day of the year (305th in leap years) in the Gregorian calendar; 61 days remain until the end of the year.

415: Co-emperors Honorius and Theodosius II issue penalties against Montanists and against any land-owner who permits them to assemble on his property. Montanist meeting places are to be turned over to orthodox churches.

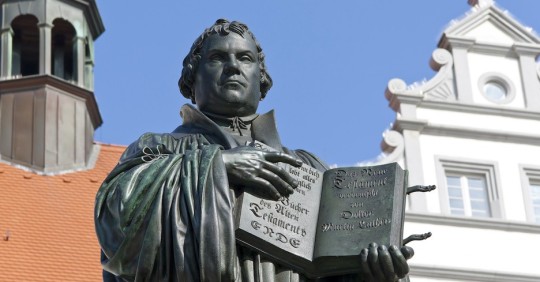

1517: Martin Luther (pictured above) nails a challenge to a debate on the Wittenberg church door. It consists of ninety-five statements, or theses, against the practice of indulgences—theses which he is willing to defend. The theses will be widely distributed and precipitate the Reformation.

1731: Catholic archbishop Leopold von Firmian of Salzburg, Austria, issues an edict expelling all Lutherans from his territory. About twenty thousand people have to leave. Many have nowhere to go and freeze to death in the coming winter.

1754: Provost Acrelius writes to the Consistory of Upsala, requesting the suspension of Rev. John Lidenius from the Swedish ministerial office because he preaches in English.

1772: Thomas and Samuel Green of New Haven publish “A Sermon” by Indian preacher Samson Occum which he had given the month before at the hanging of an Indian man for murder. The sermon becomes wildly successful, going through ten editions in eight years.

1816: Robert Moffat sails for South Africa where he will establish a mission work. Mission leaders had been reluctant to send him, believing he was unqualified. He will become a world-famed mission leader.

1832: George Washington Doane is consecrated Episcopal bishop of a diocese in New Jersey. He will be remembered by Christians for his hymns, especially “Softly Now the Light of Day.”

1871: Vasilii Ivanov is baptized in Tbilisi, Georgia, in the Kura River, an event considered the starting point of the Baptist movement in Azerbaijan, because he will spread the Baptist faith throughout Baku province.

1877: Samuel Schereschewsky is consecrated Anglican Bishop of Shanghai. Developing Parkinson’s disease, he will resign his position, and spend the rest of his life completing a translation of the Bible into Wenli (a Chinese dialect), typing hundreds of pages with the one finger that he could still move.

1879: Death of Jacob Abbott, American Congregationalist author. He wrote many groundbreaking works of children’s fiction, including the instructional Rollo series and the warm Franconia novels.

1920: Baptism of Spetume Florence Njangali in Saint Peter’s Cathedral, Hoima, Uganda. She will become a leader in the effort to obtain theological education for women and their ordination as deaconesses in the Anglican church of Uganda.

1992: Pope John Paul II admits that the Roman Catholic church erred three hundred and sixty years earlier when it condemned Italian astronomer Galileo.

1999: Catholics and Lutherans issue a joint statement on justification in Augsburg, Germany, declaring that “a consensus in basic truths of the doctrine of justification exists between Lutherans and Catholics.”

2010: Islamic terrorists besiege Our Lady of Perpetual Help Church in Baghdad, massacring most of the 120 worshipers inside, including a three year old boy who pleaded with them to stop killing.

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Horses of St Mark’s Basilica, Venice

The horses were placed on the facade, on the loggia above the porch, of St Mark's Basilica in Venice, northern Italy after the sack of Constantinople in 1204. They remained there until looted by Napoleon in 1797 but were returned in 1815. The sculptures have been removed from the facade and placed in the interior of St Mark's for conservation purposes, with replicas in their position on the loggia.

It is certain that the horses, along with the quadriga with which they were depicted, were long displayed at the Hippodrome of Constantinople; they may be the "four gilt horses that stand above the Hippodrome" that "came from the island of Chios under Theodosius II" mentioned in the 8th- or early 9th-century Parastaseis syntomoi chronikai. They were still there in 1204, when they were looted by Venetian forces as part of the sack of the capital of the Byzantine Empire in the Fourth Crusade. The collars on the four horses were added in 1204 to obscure where the animals' heads had been severed to allow them to be transported from Constantinople to Venice. Shortly after the Fourth Crusade, Doge Enrico Dandolo sent the horses to Venice, where they were installed on the terrace of the façade of St Mark's Basilica in 1254. Petrarch admired them there.

In 1797, Napoleon had the horses forcibly removed from the basilica and carried off to Paris, where they were used in the design of the Arc de Triomphe du Carrousel together with a quadriga.

In 1815 the horses were returned to Venice by Captain Dumaresq. He had fought at the Battle of Waterloo and was with the allied forces in Paris where he was selected, by the Emperor of Austria, to take the horses down from the Arc de Triomphe du Carrousel and return them to St Mark's in Venice. For the skillful manner in which he performed this work the Emperor gave him a gold snuff box with his initials in diamonds on the lid.

#horses#bronze#st mark’s basilica#venice#venetian#fourth crusade#sack of constantinople#constantinople#crusaders#classical antiquity#sculptures#classical greek#history#europe#european#hippodrome#napoleon#horses of saint mark#triumphal quadriga#horses of the hippodrome of constantinople#northern italy#republic of venice#crusades

163 notes

·

View notes

Text

Saints&Reading: Thursday, August 24, 2023

august 11_august 24

VENERABLE THEODOSIUS, (FEDOR) PRINCE OF OSTROZH (1483)

Saint Theodore, Prince of Ostrog, gained fame with the construction of churches and by his defense of Orthodoxy in Volhynia against the enroachment of Papism. He was descended from Saint Vladimir (July 15), through a great-grandson Svyatopolk-Michael, prince of Turov (1080-1093) and later Great Prince of Kiev (+1113).

The first time the name of the holy Prince Theodore is mentioned is in the year 1386, when the Polish king Jagiello and the Lithuanian prince Vitovt affirmed his hereditary possession of the Ostrog district, and they augmented the Zaslavsk and Koretsk surroundings.

In 1410 Saint Theodore participated in the defeat of the Teutonic Knights of the Catholic Order at the Battle of Gruenwald. In 1422 the holy prince, because of sympathy for the Orthodox in Bohemia, supported the Hussites in their struggle with the German emperor Sigismund. Theodore introduced the Hussite formation (i.e., the Taborite, adopted by the Ukrainian Cossacks) into Russian military strategy.

In 1432, after winning a series of victories over the Polish forces, Saint Theodore compelled Prince Jagiello to guarantee the freedom of Orthodoxy in Volhynia under the law. Prince Svidrigailo, apprehensive of the strengthening of his ally, locked Saint Theodore into prison, but the people who loved the saint rose up in rebellion, and he was freed.

Saint Theodore was reconciled with the offender and went to him for help in the struggle against the Lithuanians and the Poles. In 1438, the holy prince took part in a battle with the Tatars. In 1440, with the accession to the Polish throne of Cazimir, youngest son of Prince Jagiello, Saint Theodore received the rights of administration of the city of Vladimir, Dubno, Ostrog, and he was granted extensive holdings in the best regions of Podolia and Volhynia.

Saint Theodore left all this behind, together with princely power and fame. After 1441 he entered the Kiev Caves monastery, where he received the monastic tonsure with the name Theodosius, he struggled there for the salvation of his soul until the time of his blessed repose.

The year of Saint Theodore’s death is unknown, but it is probable that he died in the second half of the fifteenth century at a great old age (S. M. Soloviev in his History of Russia gives the year of his death as 1483). The saint was buried in the Far Caves of Saint Theodosius. His glorification apparently took place at the end of the sixteenth century, since in the year 1638 the hieromonk Athanasius Kal’nophysky testified that “Saint Theodore rests in the Theodosiev Cave, where his body was discovered incorrupt.”

Saint Theodore is also commemorated on the Synaxis of the Monastic Fathers of the Far Caves on August 28.

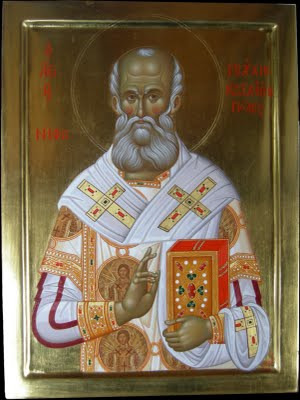

SAINT NYPHONTES, PATRIARCH OF CONSTANTINOPLE (1483)

Saint Nḗphon II, the Patriarch of Constantinople, was from the Peloponnesos. His parents were named Manuel and Maria, and he was named Nicholas in Holy Baptism. Later, he was tonsured as a monk at Epidauros, receiving the new name Nḗphon.

After the death of his Elder Anthony, he went to Mount Athos, where he occupied himself by copying books. Afterward, he was chosen as Metropolitan of Thessaloniki. In 1486 he occupied the Patriarchal throne of Constantinople.

Banished in 1488, the Saint went to the Holy Mountain, at first to Vatopedi Monastery, and then to the monastery of Saint John the Forerunner (Dionysiou). He concealed his rank and occupied the lowliest position. By God’s providence, his rank was revealed to the brethren of the monastery. Once, when the Saint was returning from the forest where he had gone for firewood, all the brethren went out to meet him, greeting him as Patriarch. But even after this, the Saint continued to share various tasks with the brethren.

In all, he served three times as Patriarch of Constantinople: 1486-1488; 1497-1498; and 1502.

Saint Nḗphon reposed on September 3, 1508 at the age of 90. Immediately after his death, he was honored as a Saint in many places. On August 16, 1517, in the newly-established monastery of Curtea de Argeş, Patriarch Theoleptos of Constantinople, together with the Synod of the Romanian Lands, and the Igoumens of the Athonite monasteries, performed the solemn glorification of Saint Nḗphon, decreeing that his Feast Day be celebrated on August 11th.

His relics are kept in a shrine at the Monastery of Dionysiou, where there is also a chapel dedicated to him. In gratitude, the Athonite monks gave the Saint's head and hand to Nyagoe Basarab, who placed them in the Monastery he built at Curtea de Argeş in what is now Romania. In the XVIII century, these relics were placed in a silver reliquary.

At the behest of the Holy Synod of the Romanian Orthodox Church, they were brought to Craiova, to the church of Saint Dēmḗtrios, the Metropolitan cathedral of Oltenia on October 25, 1949.

In 2009, the relics of Saint Nḗphon were moved to the Cathedral of the Ascension of the Lord at Târgovişte.

Source: All texts Orthodox Church in America_ OCA

2 CORINTHIANS 7:1-10

1 Therefore, having these promises, beloved, let us cleanse ourselves from all filthiness of the flesh and spirit, perfecting holiness in the fear of God. 2 Open your hearts to us. We have wronged no one, we have corrupted no one, we have cheated no one. 3 do not say this to condemn; for I have said before that you are in our hearts, to die together and to live together. 4 Great is my boldness of speech toward you, great is my boasting on your behalf. I am filled with comfort. I am exceedingly joyful in all our tribulation. 5 For indeed, when we came to Macedonia, our bodies had no rest, but we were troubled on every side. Outside were conflicts, inside were fears. 6 Nevertheless God, who comforts the downcast, comforted us by the coming of Titus, 7 and not only by his coming, but also by the consolation with which he was comforted in you, when he told us of your earnest desire, your mourning, your zeal for me, so that I rejoiced even more. 8 For even if I made you sorry with my letter, I do not regret it; though I did regret it. For I perceive that the same epistle made you sorry, though only for a while 9 Now I rejoice, not that you were made sorry, but that your sorrow led to repentance. For you were made sorry in a godly manner, that you might suffer loss from us in nothing. 10 For godly sorrow produces repentance leading to salvation, not to be regretted; but the sorrow of the world produces death.

MARK 1:29-35

29 Now as soon as they had come out of the synagogue, they entered the house of Simon and Andrew, with James and John. 30 But Simon's wife's mother lay sick with a fever, and they told Him about her at once. 31 So He came and took her by the hand and lifted her up, and immediately the fever left her. And she served them. 32 At evening, when the sun had set, they brought to Him all who were sick and those who were demon-possessed. 33 And the whole city was gathered together at the door. 34 Then He healed many who were sick with various diseases, and cast out many demons; and He did not allow the demons to speak, because they knew Him. 35 Now in the morning, having risen a long while before daylight, He went out and departed to a solitary place; and there He prayed.

#orthodoxy#orthodoxchristianity#easternorthodoxchurch#originofchristianity#spirituality#holyscriptures#gospel#bible#wisdom#saints

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

THE DESCRIPTION OF SAINT AMBROSE OF MILAN

Feast Day: December 7

"It is preferable to have a virgin mind than a virgin body. Each is good if each be possible; if it be not possible, let me be chaste, not to man but to God."

Like Augustine himself, the older Ambrose, born around 340, was a highly educated man who sought to harmonize Greek and Roman intellectual culture with the Catholic faith. Trained in literature, law, and rhetoric, he eventually became the governor of Liguria and Emilia, with headquarters at Milan. He manifested his intellectual gifts in defense of Christian doctrine even before his baptism.

While Ambrose was serving as governor, a bishop named Auxentius was leading the diocese. Although he was an excellent public speaker with a forceful personality, Auxentius also followed the heresy of Arius, which denied the divinity of Christ. Although the Council of Nicaea had reasserted the traditional teaching on Jesus' deity, many educated members of the Church – including, at one time, a majority of the world's bishops – looked to Arianism as a more sophisticated and cosmopolitan version of Christianity. Bishop Auxentius became notorious for forcing clergy throughout the region to accept Arian creeds.

At the time of Auxentius' death, Ambrose had not yet even been baptized. But his deep understanding and love of the traditional faith were already clear to the faithful of Milan. They considered him the most logical choice to succeed Auxentius, even though he was still just a catechumen. With the help of Emperor Valentinan II, who ruled the Western Roman Empire at the time, a mob of Milanese Catholics virtually forced Ambrose to become their bishop against his own will. Eight days after his baptism, Ambrose received episcopal consecration on Dec. 7, 374. The date would eventually become his liturgical feast.

Bishop Ambrose did not disappoint those who had clamored for his appointment and consecration. He began his ministry by giving everything he owned to the poor and to the Church. He looked to the writings of Greek theologians like St. Basil for help in explaining the Church's traditional teachings to the people during times of doctrinal confusion. Like the fathers of the Eastern Church, Ambrose drew from the intellectual reserves of pre-Christian philosophy and literature to make the faith more comprehensible to his hearers. This harmony of faith with other sources of knowledge served to attract, among others, the young professor Aurelius Augustinus – a man Ambrose taught and baptized, whom history knows as St. Augustine of Hippo.

Ambrose himself lived simply, wrote prolifically, and celebrated Mass each day. He found time to counsel an amazing range of public officials, pagan inquirers, confused Catholics and penitent sinners. His popularity, in fact, served to keep at bay those who would have preferred to force him from the diocese, including the Western Empress Justina and a group of her advisers, who sought to rid the West of adherence to the Nicene Creed, pushing instead for strict Arianism. Ambrose heroically refused her attempts to impose heretical bishops in Italy, along with her efforts to seize churches in the name of Arianism. Ambrose also displayed remarkable courage when he publicly denied communion to the Emperor Theodosius, who had ordered the massacre of 7,000 citizens in Thessalonica leading to his excommunication by Ambrose. The chastened emperor took Ambrose's rebuke to heart, publicly repenting of the massacre and doing penance for the murders. "Nor was there afterwards a day on which he did not grieve for his mistake," Ambrose himself noted when he spoke at the emperor's funeral.

The rebuke spurred a profound change in Emperor Theodosius. He reconciled himself with the Church and the bishop, who attended to the emperor on his deathbed. St. Ambrose died in 397. His 23 years of diligent service had turned a deeply troubled diocese into an exemplary outpost for the faith. His writings remained an important point of reference for the Church, well into the medieval era and beyond. St. Ambrose has been named one of the 'holy fathers' of the Church, whose teaching all bishops should 'in every way follow.'

Ambrose joins Augustine, Jerome, and Gregory the Great as one of the Latin Doctors of the Church.

#random stuff#catholic#catholic saints#ambrose of milan#san ambrocio#saint ambrose#beekeepers#candlemakers#doctor of the church

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Murder

According to Socrates Scholasticus, during the Christian season of Lent in March 415, a mob of Christians under the leadership of a lector named Peter, raided Hypatia's carriage as she was travelling home.[95][96][97] They dragged her into a building known as the Kaisarion, a former pagan temple and center of the Roman imperial cult in Alexandria that had been converted into a Christian church.[89][95][97] There, the mob stripped Hypatia naked and murdered her using ostraka,[95][98][99][100] which can either be translated as "roof tiles" or "oyster shells".[95] Damascius adds that they also cut out her eyeballs.[101] They tore her body into pieces and dragged her limbs through the town to a place called Cinarion, where they set them on fire.[95][101][100] According to Watts, this was in line with the traditional manner in which Alexandrians carried the bodies of the "vilest criminals" outside the city limits to cremate them as a way of symbolically purifying the city.[101][102] Although Socrates Scholasticus never explicitly identifies Hypatia's murderers, they are commonly assumed to have been members of the parabalani.[103] Christopher Haas disputes this identification, arguing that the murderers were more likely "a crowd of Alexandrian laymen".[104]

Socrates Scholasticus presents Hypatia's murder as entirely politically motivated and makes no mention of any role that Hypatia's paganism might have played in her death.[105] Instead, he reasons that "she fell a victim to the political jealousy which at that time prevailed. For as she had frequent interviews with Orestes, it was calumniously reported among the Christian populace that it was she who prevented Orestes from being reconciled to the bishop."[95][106] Socrates Scholasticus unequivocally condemns the actions of the mob, declaring, "Surely nothing can be farther from the spirit of Christianity than the allowance of massacres, fights, and transactions of that sort."[95][102][107]

The Canadian mathematician Ari Belenkiy has argued that Hypatia may have been involved in a controversy over the date of the Christian holiday of Easter 417 and that she was killed on the vernal equinox while making astronomical observations.[108] Classical scholars Alan Cameron and Edward J. Watts both dismiss this hypothesis, noting that there is absolutely no evidence in any ancient text to support any part of the hypothesis.[109][110]

Aftermath

Hypatia's death sent shockwaves throughout the empire;[40][111] for centuries, philosophers had been seen as effectively untouchable during the displays of public violence that sometimes occurred in Roman cities and the murder of a female philosopher at the hand of a mob was seen as "profoundly dangerous and destabilizing".[111] Although no concrete evidence was ever discovered definitively linking Cyril to the murder of Hypatia,[40] it was widely believed that he had ordered it.[40][88] Even if Cyril had not directly ordered the murder himself, his smear campaign against Hypatia had inspired it. The Alexandrian council was alarmed at Cyril's conduct and sent an embassy to Constantinople.[40] The advisors of Theodosius II launched an investigation to determine Cyril's role in the murder.[107]

The investigation resulted in the emperors Honorius and Theodosius II issuing an edict in autumn of 416, which attempted to remove the parabalani from Cyril's power and instead place them under the authority of Orestes.[40][107][112][113] The edict restricted the parabalani from attending "any public spectacle whatever" or entering "the meeting place of a municipal council or a courtroom."[114] It also severely restricted their recruitment by limiting the total number of parabalani to no more than five hundred.[113] According to Damascius, Cyril himself allegedly only managed to escape even more serious punishment by bribing one of Theodosius's officials.[107] Watts argues that Hypatia's murder was the turning point in Cyril's fight to gain political control of Alexandria.[115] Hypatia had been the linchpin holding Orestes's opposition against Cyril together, and, without her, the opposition quickly collapsed.[40] Two years later, Cyril overturned the law placing the parabalani under Orestes's control and, by the early 420s, Cyril had come to dominate the Alexandrian council.[115]

5 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Today we celebrate the Holy Hieromartyr Benjamin of Persia. Saint Benjamin was executed during a period of persecution of Christians that lasted forty years and through the reign of two Persian kings: Isdegerd I, who died in 421, and his son and successor, Varanes V. King Varanes carried on the persecution with such great fury that Christians were submitted to the most cruel tortures. Benjamin was imprisoned for a year for his Christian faith, and later released with the condition that he abandon preaching or speaking of his religion. His release was obtained by the Eastern Roman Emperor Theodosius II through an ambassador. However, Benjamin declared that it was his duty to preach about Christ and that he could not be silent. As a consequence, Benjamin was tortured mercilessly until his death in the year 424, specifically, "sharpened reeds [were] stuck under the nails of his fingers and toes." According to his hagiography, when the king was apprised that Benjamin refused to stop preaching, he "... caused reeds to be run in between the nails and the flesh, both of his hands and feet, and to be thrust into other most tender parts, and drawn out again, and this to be frequently repeated with violence. Lastly, a knotty stake was thrust into his bowels, to rend and tear them, in which torment he expired...." May he intercede for us always + Source: https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Benjamin_the_Deacon_and_Martyr (at Tehran, Iran) https://www.instagram.com/p/CqbO8OHLoLY/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Translation of the Relics of St. John Chrysostom (Feast Jan 27):

In the year after the Saint's repose both the Emperor Arcadius and his wife Eudoxia, who had been most responsible for St John's exile, died. Their son Theodosius II succeeded to the throne. Soon most of the exiled supporters of St John were restored to their sees. In 434 St Proclus, a disciple of St John Chrysostom, was made Archbishop of Constantinople, and persuaded the Emperor to have St John's relics solemnly translated from Comana to Constantinople. But all efforts to disinter his remains failed, as if his coffin were sealed in the earth. Learning of this, the Emperor wrote a letter to St John asking forgiveness for his father's persecution, and pleading with him to agree to return to the Imperial City for the benefit of the faithful. As soon as this letter was placed over the Saint's tomb, his coffin was removed with no difficulty and conveyed solemnly to Constantinople.

When the cortege reached Constantinople, the Emperor met it and prostrated himself before it, once again begging the Saint's forgiveness for the sins of the State against him. At last, the relics were deposited beneath the altar of the Church of the Holy Apostles, where they worked many miracles during the celebration of the Liturgy. Since then, the relics have been scattered throughout the world, where they never fail to reveal the Saint's loving presence.

17 notes

·

View notes

Note

It’s so hard to come by engaging discussions about the history of Rome. To be honest I’m more of a Greek and Hellenistic fanboy, would you believe me if I told you I sent a long letter to a university professor about Philip II of Macedon and got an answer just last week? But recently I’ve moved on from classical Rome towards late antiquity. Everyone likes Rome at its might, but it’s slow decline is equally fascinating. Reading about figures like Constantine (he’s such a massive character) and Theodosius the Great and the later dynasties made me see Rome’s struggle to become a state in the modern conception, but failing and falling. In the midst you can clearly see the medieval elements slowly creeping in.

But I can safely say I only understood something of Rome after reading Walter Scheidel’s Escape from Rome. It’s an academic book about the theory of empire applied to Rome, it was an eye opener for me in regards not only to Rome’s rise and fall, but also to patterns in history as a whole.

I really like your vision for Hannibal!Eren. The tragedy of Carthage and the intense rivalry with Rome is something Eren easily fits in. The tremendous efforts Hannibal and Eren went through only to fail in the end. What’s more, there’s this curious coincidence that Carthage was (in the myth) founded by Dido, which parallels Ymir Fritz. But where does Mikasa fit in all this? I’d love to hear your ideas about this.

When I first thought of Eren as Attila and Mikasa as Honoria, it was because history itself gave me the plot. It was already there, just adding a bit of romance. And Eren fits so well as someone known as “the scourge of God” (though I’d say your depiction with him as Hannibal and his relationship with Carthage/Paradis is more in tune to canon). I’m a way I identify the Huns’ massive invasion of Europe and Rome with the rumbling, a massive, earth-shattering event. And the idea of a “barbarian” king Eren having this political marriage to Mikasa Augusta, from such a different culture, seems such a challenge.

This doesn’t make a lot of sense but I’ve thought about Erwin as Aetius. Though Armin could be Aetius too, somehow. Levi could be the Roman emperor of the East. Safe behind the Theodosian Triple Walls of Constantinople, he paid Eren a hefty sum not to ravage the east. Which in turn prompts Eren, the newly ascendant leader of the Huns, to attack the much weaker west and expand his already huge Hunnic “empire”. Mikasa’s letter is just the perfect opportunity. I imagine he even presents himself as a hero, a true savior after Kenny places her in house arrest and claiming he’s always loved her from afar. While in reality his plans are to use her and the marriage as a political tool to control the western Roman Empire. Only he falls in love in the middle. He’d maybe be kind of brutish in his ways and she’d be all refined? Zeke, like Attila’s brother Bleda, would’ve either been killed by Eren right in the beginning of his reign during a typical brotherly power struggle. Or, mirroring their relationship in canon, Zeke is Eren’s second in command squabbling against Levi in the eastern border. Like this all came to me in an instant

By the way, I know Paradis is based on Nördlingen, but to me it’s impossible the Walls of Paradis aren’t a reference to the Theodosian land Walls of Constantinople, which lasted one thousand years. Triple walls, that is, three rows of huge walls, build to protect the city that’s seen as the last true vestige of a once greater civilization?

Anyways, what I like most about your idea of Eren as Hannibal is how it mirrors Eren’s profound desire to protect his home, while at the same time having this intense hatred towards the enemy that by all accounts is stronger. Eren’s obsessiveness, irrational hatred and prejudice is something you did so well on the witch hunter universe, and of course it’s not exactly the same thing here, but it is something I see when I think of Hannibal!Eren

i’m much more into greece as well! i started off as a huge greek mythology nerd as a kid then gradually started dipping my toes into more and more, like the romans, the egyptians, the mesopotamians, the phoenicians, etc. i’m in love with any ancient society and i’m fascinated by the way people lived back then. i’m doubly fascinated by the similarities that i spot in history that i can see around me today. like whenever i decide to read up on rome, i’m always struck by the parallelism between ancient roman society and modern american society. i know the founding fathers intentionally copied the romans when it came to the structure of the american government, but it’s still so surprising to see how blatant it is. beyond that, things like the fall of the republic, inflation, the late-republican issue of plebeians being bought out of their land by richer patricians and having to run to the city in droves reminds me so much of america today. it’s crazy. i don’t know if you’re american, but i am and seeing that just fills me with dread😭 humans will be humans. also, i wanna check out the book you mentioned! it sounds really interesting. i love the politics of that time period too, and while i’m not obsessed with the fall of (western) rome, i do still think that it’s an insane time period. i’ll add that to my rome list along with the mary beard book.

onto eren as hannibal, i like your point about ymir fritz being the mythical dido. it works really really well. as for how mikasa fits in, i know that hannibal had a wife named imilce, but as far as i know, not much is written about her. it���s not as exciting as attila/honoria, but i was thinking it can be more of a hector/andromache kind of relationship? there’s a really beautiful scene where they say goodbye and hector’s son is scared of him in his armor. i think it represents pretty well what eren is giving up in his pursuit to destroy rome. and with what we know about hannibal’s end, it’s basically for nothing. he’s exiled.

i really love your idea for honoria!mikasa/attila!eren. there’s a lot of intrigue for mikasa here, and i like the idea of it starting out as a marriage of convenience. eren definitely wouldn’t be shy about wanting to conquer the western seat of rome, and i think mikasa— wanting to escape whatever man she’s marrying— would know that and deliberately write to him for that reason. i think the man she’s marrying would have to be pretty drastically bad for her to do that, though. either he’s not as politically safe as the emperor imagined (and eren is a lesser threat by comparison) or he’s horribly abusive in some way and eren is still a lesser threat. though if it’s spite for being locked up, i get it😭 i’d do that too. fuck around and find out. i like zeke being his second in command and squabbling with levi. that’s really fun. and you say you cant write stories but everything you said here was awesome. i love this idea. it sounds like a political/romantic epic.

on your last point, i wouldn’t be surprised if isayama did base the walls on the walls of constantinople. he clearly did his research for the history of aot. even the ancient marleyans look very roman to me.

and thank you so much!!! witch-hunter eren is a character i really really enjoyed writing. he was essentially a child soldier adopted into a fanatic military cult hellbent on genocide. his psyche was really fun to explore, and i liked that he ended the story with the promise that he would change, not that he has. that kind of brainwashing isn’t something true love can just will away, but i liked that he had the strength to try. it seemed much more realistic to me than a sudden change of heart.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Istanbul day 1

I’ve returned home ! My legs are absolutely destroyed by walking but it was so very fun! I‘ve taken more then 200 photos in the days I was in Istanbul ,but I‘ve the best ones to show some of the best places I saw in the travel!

The first thing I saw was the Sultanahmet Square!

During the Byzantine Empire it was an Ippodromo, horse racing circus!

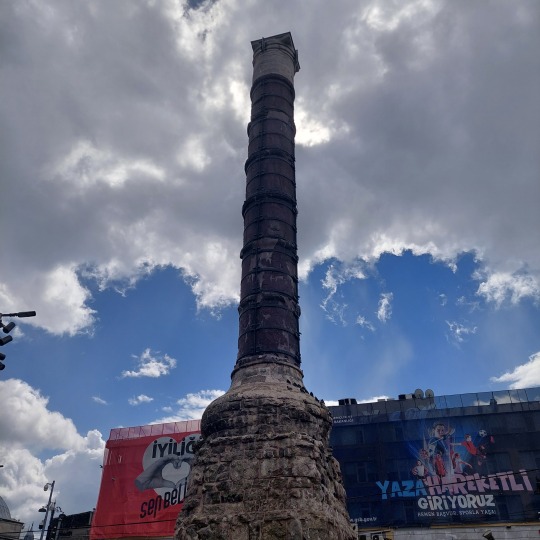

Örme Dikilitaş (Column of Constantine Porphyrogenitus) It used to have metal decorations but the crusades looted it.

The Serpent column ! It is part of an antient Greek Sacrificial tripod , originally in Delphi and relocated by Costantine the Great in 324!

It was built to commemorate the Greeks who fought and defeated the Persian Empire at the battle of Plataea (479 BC).

The Obelisk of Theodosius , that was erected during the 18th Dynasty by Pharaoh Thutmose III (1479–1425 BC), then transported to Costantinople by the Roman Emperor Theodosius I in the 4th century AD.

(it’s is 2/3 of it’s original height as it was cut )

…on the sides there are writings done in both Latin:

"Formerly [I was] reluctant to obey peaceful masters, and ordered to carry the palm [of victory] for tyrants now vanquished and forgotten. [But] all things yield to Theodosius and to his eternal offspring. So too was I prevailed over and tamed in three times ten days, raised towards the skies under governor Proculus.""

And ancient Greek!

"This column with four sides which lay on the earth, only the emperor Theodosius dared to lift again its burden; Proclos was invited to execute his order; and this great column stood up in 32 days"

Then there was a German Fountain!

It was dedicated to the second visitor the Prussian King and German Emperor Wilhelm II in 1898 and to represent Turkish and German friendship!

Then I went to the Grand Bazaar! This is Gate 1 where the Ottoman coat of Arms can be seen, It was full of shops of all kinds !

Ceramics!

Old things of all kinds! (Instagram: minyaturantika)

And Lamps! and all kinds of shiny colorful things!

After that I went to Out and found an other column , Column of Constantine!

In 330 AD it was Remouved from the temple of Apollo in Rome and erected in the Forum of Costantine by Costantine.

In origin At the top ther was the statue of Apollo saluting the sun , but Constantine ordered to replace it with a statue of himself , then later on it was changed by other emperors with their own statues as well.

The column was struck by lightning in 1081 and destroyed it , Alexios Comnenus I replaced the column with a pedestal and a big cross on the top , but said cross was removed by the Ottomans when they conquered the city in 1453.

After the conquest it was renovated for the first time by Selim I after the 1470s!

Later the Colum was severely damaged by a fire , and so Sultan Mustafa II (1695-1704) ordered to put additional walls under the column and to put rings or iron to reinforce it!

From that day on it has been called Cemberlitas(column with rings)

There is also a myth that say some belongings of Jesus are buried under the column

After this I went to the Basilica Cistern!It was built in the 6th century during the reign of Byzantine Emperor Justinian I!

All the columns used where taken from Ancient Greek and pagan temples to reused them, as Christianity became the main religion and didn’t allow to worship the old gods.

(Some of the columns had writings on them, they are the names of the ones that build the colum , they would write their name on it to then get paid)

Returning to the fact that the Byzantine Empire was Christian, in the back of the cistern there is two faces of unknown origin depicting Medusa! They were up in the back facing away and down and or by the side to not get seen.

To finish I went on a boat in the night to look at the coast of the Bosphorus! The stretch of water that separates the Europe and Asia, and separates Turkey by separating Anatolia from Thrace!

And that was it for the first day I went there!

I go eat dinner and post some other photos , I also plan on doing a thing with Turkey and Italy exploring the Archeological Museum and Science museum I went to, because they were some of the coolest museums I‘ve ever seen!

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

From Hope of Children to Object of God’s Care: Abortion in Classical and Late Antique Society

“Roman law viewed abortion through two specific lenses: husbands’ interests in safeguarding the inheritance of legitimate children and regulation of drugs or poisons. A rescript issued under the father-and-son emperors Septimius Severus and Caracalla in the early third century typified one approach. It subjected a woman (by implication, married) who had an abortion to temporary exile because ‘it can seem shameful that she cheated her husband of children with impunity’. Jurists lent this legal approach an aura of antiquity.

Tryphoninus, another jurist active under Septimius Severus, connected the rescript to a case originally recounted by Cicero (d. 43 BCE). A woman from Miletus, a Greek city in Asia Minor, received a capital sentence for deliberately having an abortion after receiving a bribe from rival heirs. In fact, Tryphoninus did not fully explain the background. In Cicero’s account the woman had been recently widowed. Her deceased husband’s interests were at stake. Cicero agreed with the sentence because she had injured the ‘parent’s hope, the memory of his name, the provisions of a race, the heir of a family and a future citizen of the republic’.

Nonetheless, for Tryphoninus, the point was clear. Any woman who ‘has brought violence upon her insides after a divorce, because she is pregnant, so that she does not procreate a son for a hated husband, ought to be forced into temporary exile, which has been written by our most noble emperors’. Abortion could harm male interests. Safeguarding these interests was not just a legal thought experiment.

The second legal approach focused on the use and abuse of drugs, venenae, a term which could also mean poisons. Roman jurists discussed and debated the parameters of legal regulations on drugs, including interpretation of a law dating back to Republican Rome, the Lex Cornelia de sicariis et veneficiis. Jurists thought carefully, for instance, about potential problems with the use of drugs in medical practice, including midwifery.

One provision clarified that drugs for healing (ad sanandum) did not fall under the remit of the law, but added that a senatorial decree penalized any woman ‘who not with bad intention, but with bad example, has given a drug for conception, from which a woman who received it has died’. The third-century jurist Paulus brought supply of specifically abortifacient drugs within the remit of the law.

Anyone who dispensed an abortifacient or aphrodisiac drink (abortionis aut amatorium poculum) was liable to be sent to the mines or, if from the upper class, exiled to an island because, ‘although [perpetrators] may do no harm, nonetheless … the matter sets a bad example’. Bad example was ill-defined but it was related to the possibility that such drugs imperiled a woman’s life rather than the life of the fetus she carried.

The principal laws quoted above were collected in the Digest, part of the great legal project undertaken during the reign of Justinian (d. 565). From the perspective of late Roman Christian emperors and their jurists, Roman legal approaches to abortion formed part of an inheritance that was centuries old. The impact of Christianization on Roman law after the conversion of Constantine can be felt in several areas, including in law on infant exposure and abandonment.

A rescript from 374 issued under Valentinian I, Valens and Gratian made infanticide a capital offence under the Lex Cornelia. This law channelled Christianizing dynamics through established legal tradition, though subsequent fifth- and sixth-century law on infant exposure and abandonment increased the distance between classical and late Roman law. But no clear equivalents on abortion were issued.

The closest thing to new legislation on abortion appeared in late Roman imperial legislation on divorce and remarriage, which possibly had abortion in mind. The sixth-century legal compilation, the Novellae, reiterated a law of Theodosius II (d. 450) which granted a husband the right to divorce his wife if she was guilty of specific offences, including being a druggist or poisoner (venefica). A similar law – a man could divorce his wife if it were proven, among other things, that she was a medicamentaria (druggist) or malefica (sorceress) – had been issued a century or so earlier by Constantine (d. 337).

Both laws might have envisaged (or have been interpreted as envisaging) recourse to abortion. Nonetheless, in Roman law abortion constituted a public offence insofar as it harmed husbands’ interests or risked women’s lives. But it was never punishable as the killing of a fetus. Different practices generated different perspectives on what made abortion problematic. For medical writers abortion raised questions about professional conduct and the nature of medicine.

The modern temptation is to start with the Hippocratic Oath. Precisely what the Oath’s provision on abortion might have originally meant and the extent to which it represented the mainstream of ancient Greek (let alone Roman) medical ethics remains debated. Thinking in terms of reception is more illuminating. In the first century Scribonius Largus, physician to the emperor Claudius, used Hippocrates to frame the ethics of medicine.

According to Scribonius, Hippocrates had prohibited teaching about abortifacients or prescribing them to pregnant women. His position was not exactly premised on the idea that destroying the fetus was murder. If people thought that to injure (laedere) the ‘uncertain hope of a person’ was wrong, then how much worse was it to kill (nocere) a perfected being? Abortion compromised the integrity of ‘medicine, the science of healing, not of killing’. Scribonius’s construal of medical ethics might well be an outlier, for his work was not widely read.

Another author, whose Greek work (and its Latin reincarnations) was, makes clear that abortion was subject to ethical and even physiological disagreement among doctors. Soranus of Ephesus famously distinguished between atokion (contraceptive), which ‘does not let conception take place’, phthorion (abortifacient), which ‘destroys what has been conceived’ and ekbolion (expulsive), which some regarded as ‘synonymous with abortion’ but others considered distinct because it entailed ‘shaking and leaping’.

Soranus also reported a ‘controversy’. Some doctors refused to prescribe abortifacients because of the Hippocratic injunction against abortion. According to this camp, the core obligation of medicine was to ‘guard and preserve what has been engendered by nature’. Other doctors prescribed abortifacients ‘with discrimination’ on medical grounds such as when uterine abnormalities made childbirth dangerous, and ‘they say the same about contraceptives as well’. Soranus sympathized with this second position, reasoning that it was ‘safer to prevent conception from taking place than to destroy the fetus’.

There were multiple conceptions of medical ethics and professional norms. Galen chided medical authors for divulging information on abortifacients because many were risibly ineffective and those which did work were dangerous. Pliny the Elder (d. 79), whose Naturalis historia provides an intriguing non-professional perspective on medical (and non-medical) reproductive technologies, refused in principle to provide information on abortifacients except by way of providing warnings.

He did not quite live up to his professed reticence, though much of his relevant information concerned expelling fetuses already dead in the womb and his references to abortion tended to carry warnings. He justified mentioning information on an atocium – an amulet containing worms cut out from a particular kind of spider – because ‘some women’s fecundity, teeming with children, needs such indulgence’. The plurality of perspectives represented, in part, different responses to the tension between safeguarding maternal health and medicine as healing.

The tension was palpable in the Euporiston, a fourth-century work by Theodorus Priscianus. The third book, adapted from Soranus, was devoted to gynaecology and contained a section on abortion. ‘It is never right to give an abortive to anyone,’ it began before quickly referring to Hippocrates. But Priscianus also recognized that complications such as uterine abnormalities or a woman’s age could precipitate dangerous obstetric emergencies. He likened the difficult choice to pruning the branches of a tree or emptying overloaded ships of their cargo during a storm.

Nine abortifacient remedies followed. The obstetric emergencies which these recipes were designed to avoid were real dangers. The most extreme recourse was embryotomy, the surgical excision of living or dead fetuses from the womb. A powerful evocation of the medical dilemma appeared in a tangent on embryotomy in De anima, a theological treatise by the early Christian author Tertullian (d. c. 225).

Tertullian used embryotomy, taught (so he claimed) by the medical heavyweights Hippocrates, Asclepiades, Herophilus, Erasistratus and even the milder (mitior) Soranus, to refute the argument that the soul was not conceived in the womb but only later after birth. If embryotomy killed a fetus, Tertullian reasoned, then the fetus had been alive and animate. He also conveyed some practical details. A special surgical device prised open the womb while an attached blade dissected the fetus. Another instrument with a copper spike took the fetus’s life.

Tertullian’s position on the morality of embryotomy is more difficult to interpret. He described the practice as a crime (scelus), a throat-slitting (iugulatio) and a furtive robbery (caecum latrocinium) performed with a gruesome spiked instrument he called the embryo-slayer (a Greek word, embruosphaktê). But Tertullian’s charged language was also flecked with acknowledgment that the predicament raised difficult choices.

The infant in the womb was ‘butchered with necessary cruelty’ because it threatened to become a ‘matricide unless it dies’. Embryotomy was a final resort. In other words, most medical and moral discussion of abortion focused on much earlier (and more ambiguous) stages of pregnancy. Nonetheless, Tertullian’s tangent dramatized the core medical tension between the life of the fetus and the life of the mother, between healing-not-killing and killing-to-heal. It also demonstrates that a medicalized construal of the problem of abortion could migrate beyond the works of medical writers.”

- Zubin Mistry, Abortion in the Early Middle Ages, c.500-900

15 notes

·

View notes