#Dachau concentration camp

Text

My grandmother Marianne spent her entire life telling the story of how she, her parents and her three brothers escaped Nazi Germany. At Thanksgiving or during Jewish holidays she would recount the same memories over and over, seemingly still traumatized by the violence she had witnessed and the hatred she saw from her German friends and neighbors.

The story she told, preserved in her unpublished memoirs — a combination of her own reflections and meticulously compiled correspondence and records related to her family’s escape — detailed the changes that came as authoritarianism slowly gained power, incrementally at first, so that people became accustomed to them. Writing about her childhood in Pirmasens, Germany, in the years following Hitler’s rise to power, Marianne recalled her non-Jewish friends turning their backs on her, her brothers being beaten up at school by classmates in the Hitler Youth and watching as other Jewish classmates in her public school disappeared, until she herself was no longer permitted to attend. She recalled lighting Sabbath candles on Friday nights in her family’s apartment, with the sound of the Nazi storm troopers’ boots marching past on the pavement, as they sang songs about violently murdering Jews. Six million Jewish people and millions of others were ultimately murdered by the Nazi regime.

Marianne’s immediate family had no illusions about the threat that Nazism posed, though many other relatives thought that it was a phase that would pass, like other waves of anti-Semitism that had preceded it. While my great-grandfather, Dagobert Nellhaus, a rabbi, was not prepared to abandon his congregation, he had already taken some measures for the rest of his family to leave Germany, if necessary. In 1936, after the Nuremberg laws went into force and effectively stripped German Jews of citizenship, one of Marianne’s older brothers, Gerhard, was sent to live in the United States. He became the foster son of a Jewish family, the Blumbergs, in Terre Haute, Ind.

The rest of the family was still in Germany on Nov. 9, 1938, when Nazis destroyed Jewish businesses and synagogues during what became known as Kristallnacht, the “night of broken glass.” Some 30,000 Jewish men were arrested and sent to Dachau, Buchenwald and other concentration camps. The morning after, as my grandmother recalled, Dagobert took her and her brother Martin to the collapsed ruins of the synagogue. They must have watched in shock as their father trod through the charred remains where the pews had stood, where congregants had faced toward Jerusalem and watched him lead prayers from the bimah, the elevated platform from which the Torah is read. Marianne was just 11 years old. In her memoir, she recalls that he searched the ruins and found a Torah, which Jews traditionally treat with the dignity and reverence that would be accorded to an important person. The three of them walked the short way home to find the S.S. waiting to arrest Dagobert. They confiscated his library, including a sizable collection of Jewish books and artifacts and, Martin still remembers, a Torah. My great-grandfather and around 150 other Jewish men from Pirmasens were taken to Dachau concentration camp, where he was held for a little over a month. While he was in Dachau, my great-grandmother, Minna — who spoke little or no English and must have needed to find translators to help her — desperately contacted the Blumbergs in Indiana to try to get American visas for the entire family.

Dagobert was released from Dachau and returned to the family in mid-December 1938. At that point, the imprisonment of Jewish men was often meant to frighten them into leaving Germany, so incarceration was temporary. My grandmother recalled that the five weeks her father was gone had aged him. His hair was shorn, and he was emaciated. While he and Minna never talked about his experience in Dachau in front of the children, my grandmother picked up fragments about the mistreatment there: the diet of watery soup that left everyone undernourished and the men who returned home with missing toes from frostbite after standing for hours in the freezing morning roll call.

American laws at the time posed a tremendous obstacle to the Nellhaus family’s attempts to resettle in the United States. The Johnson-Reed Immigration Act of 1924 imposed a strict quota for each country, greatly reducing the number of people that could enter the United States from Germany, Poland and other countries that were home to large Jewish populations. There were exceptions, including those for clergy members, as long as they could prove that they would be gainfully employed upon arrival. An affidavit from the board of the synagogue in Terre Haute stating that my great-grandfather would be its assistant rabbi proved the family’s means of escape. The family arrived in New York on the S.S. Europa on Aug. 16, 1939. Two weeks later, Adolf Hitler invaded Poland, and the narrow door to escape began to shut.

It’s unclear if the assistant rabbi position in Indiana ever actually existed. The family settled in the Boston area, where friends of the Blumbergs helped them find an apartment and employment, and they immediately went to work and school. By the end of World War II, all three of Marianne’s brothers were serving in the military. My grandmother went to Boston University and then had a long career at the State University of New York at Buffalo, where her fluency in four languages made her well-suited to work as a reference librarian in modern languages. I imagine Marianne chose to become a keeper of books because the field allowed her to be a protector of cultural property, which she had seen desecrated and destroyed on Kristallnacht. Later, after a trip to Russia in the early 1980s, she became deeply involved in supporting the resettlement of Soviet Jews, including successfully sponsoring the settlement in Buffalo of families who had been separated by the Iron Curtain.

My family’s commitment to immediately contribute to the nation that welcomed them influenced my decision to serve. I joined the Navy when I was 22. Before that, I rarely thought about my Jewish identity. In the military, I was around fewer Jewish people than ever before, and my heritage was on display, stitched on my uniform in the form of a recognizably Jewish surname. Fellow service members often asked thoughtful questions about Judaism. Non-Jewish chaplains went to great lengths to support me when I served as a Jewish lay leader. Commanding officers allowed me days off for major holidays without charging leave. The culinary specialists on the U.S.S. Peleliu learned how to make traditional Jewish meals, for those of us who wanted the right foods every Shabbat and on major holidays. My foreign military counterparts showed me the same respect. German military officers I worked with while assigned to NATO treated me as one of their own. Muslim officers from some of the Gulf States invited me into their homes, and we compared notes on our traditions. My religion made me stand apart from most of my peers, but I was always welcomed.

Recently I have had to face a very different attitude toward my religion, right here in the United States. The synagogue I attend in Washington, Sixth & I Historic Synagogue, was desecrated in late November with anti-Semitic graffiti. I had found security and acceptance in the places where I had initially been self-conscious about my Jewishness, but my spiritual home in the nation’s capital was not safe from a bigot inscribing his hatred on the very doors that welcome strangers to prayer and cultural events.

I recently found a copy of the speech that my grandmother and grandfather gave on the day of my bat mitzvah, when in my 13-year-old awkwardness I publicly read from the Torah for the first time. I realized how lucky I was to grow up never having to live in fear because I am Jewish — and how lucky I am even to be alive because the United States had welcomed my family here. Reading my grandparents’ speech 20 years later, I wept at this passage: “We are connected in many ways to the generations who precede us. … Nevertheless, we all share the pride of being part of a people who, despite pogroms, prejudice and persecution, have stubbornly kept their identity. … You have made a commitment to the future, and you will find how best you can fulfill that commitment.”

My grandmother, Marianne Goldstein, died last month on Dec. 21, in Buffalo. I’ve thought about all of the stories she told through the years about our family and the Holocaust and the millions of other families around the world who were uprooted, ripped apart, forced to flee, detained and killed. I considered why she repeated these stories over and over. It wasn’t just about remembering; she wanted everyone to know that no society is immune from once again committing or becoming complicit in such violence, whether it’s directed against Jews or another group.

#history#military history#current events#antisemitism#judaism#culture#racism#oppression#prejudice#ww2#holocaust#kristallnacht#germany#nazi germany#poland#usa#dachau concentration camp#concentration camps

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Standing in this punishing winter wind that blasts through the gas chamber doors and into the vents and flues of the gaping crematory ovens, Martin is at peace. He prefers these common and clichéd horrors of the Holocaust, those he has seen with his own eyes, heard with his own ears, those he shares with a million other survivors, those he has read of in books and seen in films, to the personal horrors of his wife and daughter, horrors he can only imagine. These eyes that have begun to fail him here in Dachau, these ears that no longer accept the sounds around him. In Dachau, Martin has seen and heard the worst of horrors that man ever committed against man, but they are nothing compared to his inner vision of the flaming barn that lit Jedwabne's night-time sky and cast its dancing flames against the rising twin-spired church.

Martin comes to the gas chamber, to this place of palpable horror, to escape the horrors he never knew, the screams he never heard but that have called to him every silent day, every silent hour of his long life, the cries of a wife he once loved, and possibly still does, the screams of a daughter whose age he cannot speak, whose name he cannot utter, whom, out of sheer horror for what she must have suffered, he can only describe with an extended arm and an open palm.

At the age of eighty-seven, Martin feels the biting wind on his cheeks, the chill in his legs, the numbness in his fingers, and the gnawing hunger in his stomach, and knows he is alive. He has survived another day in Dachau. He can slam the gas chamber door at will, he can run the body trays in and out of the crematory ovens a hundred times if he wishes, and no one, not Max Mannheimer, not Barbara Distel, not the voices that call him on the phone or in his dreams, can touch Martin Zaidenstadt here. This is Martin's domain.

Ich bringe Martin zur Gaskammer. He revels in these words, in the fact that they can be repeated day after day. He has survived the gas chamber today as he did fifty years ago, as he has done for the past four years, as he has done, so he believes, for the last half-century. The watchtowers are vacant, the electrified fences idle, the gas ovens cold, and Martin stands triumphant in Dachau. It is the story of death and rebirth, reenacted day in and day out within this walled compound. Ich bringe Martin zur Gaskammer. Once again, Martin has entered the gas chambers and come out alive.

— The Last Survivor: Legacies of Dachau(Timothy W. Ryback)

#book quotes#timothy w. ryback#the last survivor: legacies of dachau#history#nazism#antisemitism#psychology#trauma#ww2#holocaust#germany#nazi germany#dachau#dachau concentration camp#martin zaidenstadt

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Our European Adventure - Day 7

Our European Adventure – Day 7

A rural Catholic church near Neuschwanstein, Germany.

Our seventh day of sightseeing started on a somber note. A short drive from Munich is the World War II concentration camp of Dachau. It was a last-minute addition to our itinerary.

As sobering and humbling as our visit was there, I am glad we stopped. Everyone must visit at least one of these sights where the worst imaginable human behavior…

View On WordPress

#atrocities#Dachau#Dachau concentration camp#Disney Castle#Hohenschwangau Castle#Mad King Ludwig#Neuschwanstein Castle#UNESCO World Heritage Site#Weis Church#World War II

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

"First they came for the communists, and I did not speak out Because I was not a communist. Then they came for the socialists, and I did not speak out Because I was not a socialist. Then they came for the trade unionists, and I did not speak out Because I was not a trade unionist. Then they came for the Jews, and I did not speak outBecause I was not a Jew. Then they came for me - and there was no one left to speak for me."

Friedrich Gustav Emil Martin Niemöller was a German theologian and Lutheran pastor. He is best known for his opposition to the Nazi regime during the late 1930s.

Born: 14 January 1892, Lippstadt, Germany

Died: 6 March 1984, Wiesbaden, Germany

#today on tumblr#quoteoftheday#Theologian of the German Protestant Church#Preacher and theologian in Nazi Germany#Opponent of Hitler#Dachau concentration camp#Religious freedom advocate#Voice of conscience#Christian resistance movement#Protestant opposition to the Third Reich#Political prisoner#Ecumenical movement#Post-war reconciliation efforts#Cold War activism#Peace and justice advocate#Interfaith dialogue#Legacy of courage and activism#Martin Niemöller#German theologian#Lutheran pastor#Anti-Nazi activist#Resistance against the Nazi regime#Theologian and pastor during Nazi Germany#Protestant resistance#Confessing Church#Holocaust resistance#Persecution of Christians in Nazi Germany#Pastor's Emergency League#Concentration camp survivor#Post-war reconciliation

1 note

·

View note

Text

#Lee Miller#a female American combat photographer#taking a bath in Hitler's bathtub in his Munich apartment on April 30#1945#shortly after she'd photographed the Dachau concentration camp#haddock420#oldschool

54 notes

·

View notes

Text

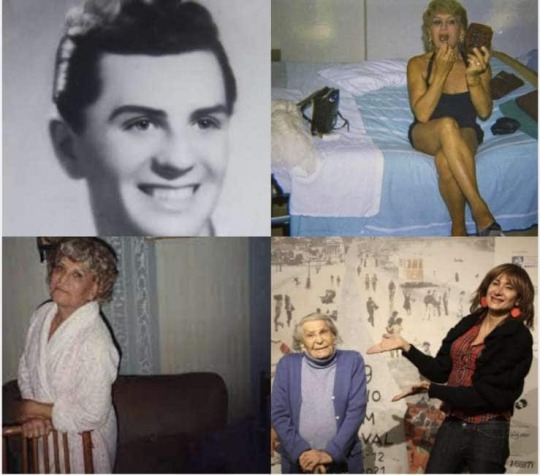

Today, Lucy Salani passed away at the age of 98. She was not only a survivor of one of the most horrific periods in history, she was also the oldest transgender woman in Italy. She survived Dachau, the first concentration camp built by Nazi Germany.

RIP

🏳️⚧️

75 notes

·

View notes

Text

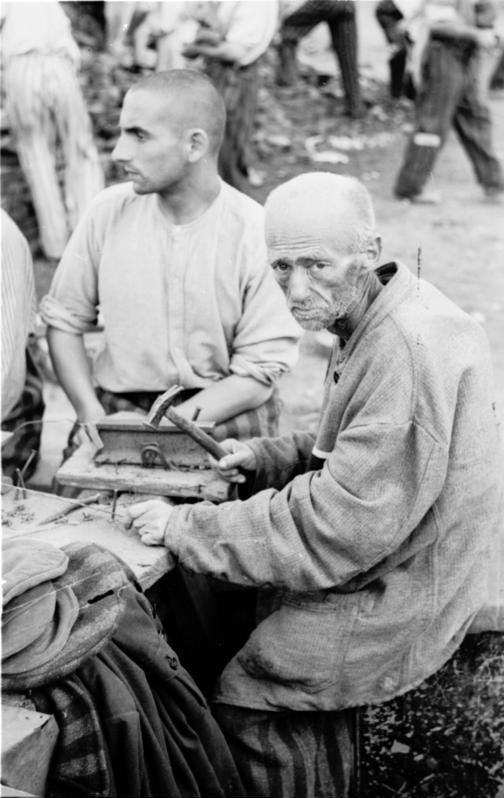

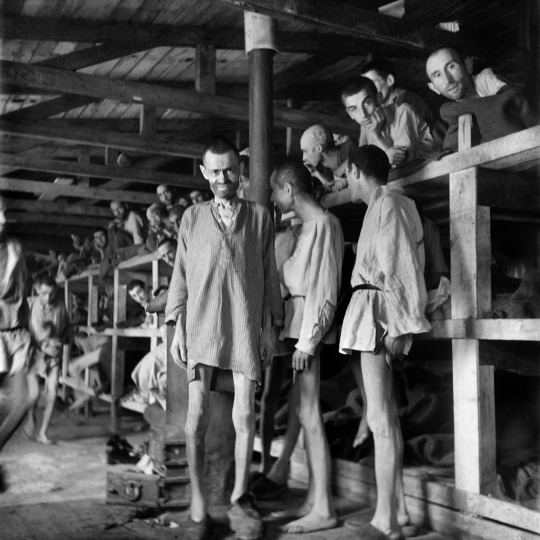

Camp de concentration de Dachau - Allemagne - 28 juin 1938

Photographe : Friedrich Franz Bauer

©Bundesarchiv - Bild 152-27-04A

#avant-guerre#pre-war#camps de concentration#concentration camps#dachau#allemagne#germany#28/06/1938#06/1938#1938

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

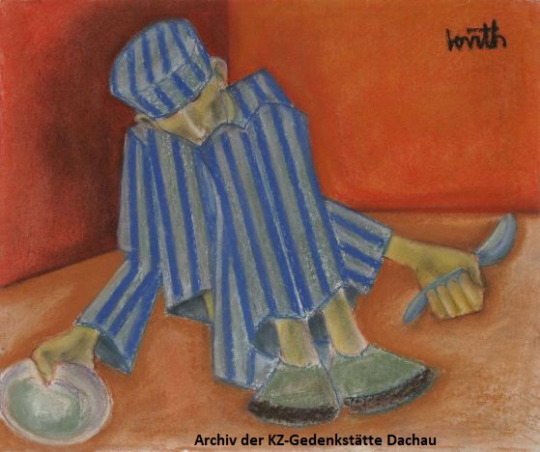

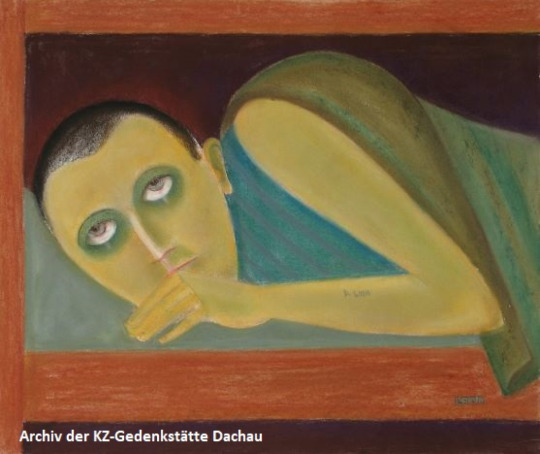

The Jewish artist Egon Marc Lövith was а survivor of the Dachau camp.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

📢 THE BIG DICTATORS from the entire globe

Chapter 1

Before we start this heading in our blog, I’ll say as a side notice, that all dictatorships are bad. And sadly, there are thousands, billions of people affected by these regimes. It’s also bad that a lot of people are saying good stuff about such dictatorships - that means that they have been caught mentally by propaganda.

Here, I’ll be talking about some of the worst dictators and some mysteries behind them. We’ll start with Asian dictators.

Let’s take a start with Kim Jong Un and his family

North Korea | Communism in XXI century

On the photo: poster from “Hall of Shame” exhibition, hosted by Peter Grigorian in Munich, Germany with the “nuclear idiot” title behind. Peter Grigorian (c)

After the WW2, the Korean Peninsula was divided between USSR and Western block - the Korean Peninsula was occupied by Japanese fascists. The North Korea became the satellite of USSR, the South Korea became an independent country.

In 1950’s North Korea wanted to unite the entire Peninsula under the regiment of Pyonyang. And at the time, the situation in North Korea regarding economics, food, job, etc. was a lot better than on South. That’s why a lot of people (ironically) wanted to communists and fleet to North Korea - later all these people have regretfully breathed about their mistake made years earlier because the situation in South Korea got a lot better than at North and the country became one of the highest economics Centre in Asia and entire world.

What about the leaders? Well, the first leader of North Korea was the colonel of Soviet Army Kim II-sung - he began to officially rule the country in 1948. After his death in 1994 he was replaced by his son Kim Jong-il - he died in 2011 and was replaced with the current leader Kim Jong-Un.

As you see, North Korea is ruled by a dynasty of Kims. And if you’ll see the photos from North Korean communistic demonstrations closely, you’ll see the portraits only of two previous leaders of KPDR (Korean People’s National Republic) - they are called as the “stars of nation” in North Korean propaganda. Well most of historians relate this phenomenon to the term of personality cult, but this is a little bit wrong and here’s why.

Let’s take it to simplicity. See, the personality cult takes place when the government wants to take people’s attention on one person - they constantly put the portraits of the leader, write the songs glorifying the leader and some long and boring speeches with the same context. But in case with KPDR, the Kim Jong Un is not shown on portraits - although Kim Jong Un is called the sun of nation among KPDR citizens, KPDR propaganda mostly talks about the beginner of this glorious golden dynasty - the Kim II-sung. This is called the family dynasty cult.

What about the people who don’t follow the communistic ideals of the country? Well, those are sent to concentration camps (let’s call them CCs). Remember Goulag in USSR? Well, in KPDR there are a lot more of these. Here’s the information what is available on the Internet.

On the photo: the map of the North Korean CCs. Translation: geschlossen (DE) -> closed, aktiv (DE) -> active, Leute (DE) -> people. Peter GRIGORIAN (c)

The CCs in KPDR contain of two zones - with high and low control. The high control zone is for people who are not worth (according to KPDR’s ideology Juche) having freedom - they are kept in the CC all the way until the prisoners die. In such zones, Pyonyang puts the people who have prepared the anticommunist rebellion, prepared the assassination of the KPDR’s leader or someone else among Communist Party, etc. The Low Control zone has a lot of similarities with the high control zone, but there are two differences: because of the people in high control zone are not worth of life and Juche ideology, there are no portraits in the territory, whereas in the low control zone has all the symbolics of KPDR, including portraits of Kim II-sung and Kim Jong-il. Also, in a low control zone, there’s a chance that you may legally leave this place in a while.

Conclusion: as we already confirmed, Korean People’s Democratic Republic is not people’s democratic at all - it’s a communistic dictatorship in style of Stalin but with other element on the place of the variable {x} in personality cult formula we discussed earlier in this blog.

Thanks for reading =) Hope you liked it!

P.S. all articles of The Big Dictators thread will be marked with #thebigdictatorsshow tag for you not to miss our next articles in this thread!

#thebigdictatorshow#north korea#kim jong un#kim jong il#communism#totalitarianism#stalinism#stalin#dictatorship#concentrationcamp#concentration camps#dachau#pyongyang

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Historically (and geographically) challenged Americans....

KL Dachau was a German concentration camp located in Bavaria, southern Germany, that operated from March 1933 to April 1945.

The majority of Dachau's prisoner population from 1940 until the camp was liberated in 1945 were Polish slavs (a little-known fact that's rarely acknowledged).

In 2017, while US vice president Mike Pence was visiting the camp, at least one American TV station added insult to injury by claiming that Dachau is in Poland....

#germany#dachau#concentration camp#history#second world war#world war 2#mike pence#historically (and geographically) challenged americans

3 notes

·

View notes

Link

On that same April evening in 1933, Joseph Hartinger received a call that four men had been shot attempting to flee the recently erected detention facility. As a local prosecutor, it was Hartinger’s job to establish a commission to investigate all deaths resulting from “unnatural causes.”

The blood was still damp on the ground when Hartinger arrived. He sensed immediately that something was horrifically wrong. “My reasons were based not only on the physical circumstances but in particular on my assessment of the personalities I encountered in the camp and especially on my evaluation of the nature of the camp commandant Wäckerle, who made a devastating impression on me,” Hartinger recalled. “I also had to include in my deliberations the fact that those who had been shot were all Jews.”

When Hartinger reported that a serial killing of Jews had taken place, his superior responded unequivocally: not even the Nazis would do that. The investigation was terminated.

But as killings continued to mount, Hartinger persisted. On June 1, 1933, he issued indictments against the camp commandant and three other SS men. It was a brazen act of legal defiance to the regime. Hartinger was not naïve. He knew the Nazi capacity for violence. That evening, he told his wife, “I just signed my own death sentence.”

The murder indictments had a surprising impact. The commandant was removed. The killings stopped. Hartinger had hurled a legal wrench into the Nazi bureaucracy and singlehandedly paralyzed its homicidal impulse.

For several weeks in the summer of 1933, the killings stalled as Nazi officials attempted to understand the implications of the Hartinger indictments. Solutions were found. The killing was renewed. Miraculously, Hartinger survived. The Nazis had deliberated on murdering him. Instead, he was transferred to another jurisdiction.

Recently, I came across the 40-page unpublished memoirs that Hartinger wrote in 1984 shortly before his death at age 91. Along with many technical details already familiar to scholars, Hartinger outlined an extraordinary plan for dismantling the emerging system in the Dachau Concentration Camp.

He understood that the Nazi regime, just a few months in power, was still sensitive to international opinion. It was his intention to use the murder indictments to expose publicly the atrocities in Dachau, force the government to evict the SS guards and replace them with trained police or military units familiar with the laws governing the proper detention and treatment of prisoners. It was a seemingly quixotic plan, but Hartinger understood the key decision makers within the government and sought to play them against one another.

He almost succeeded. “These were not fantasies,” Hartinger recalls in his memoirs. “As I later learned, there were conversations in exactly this direction except that the ‘good spirits’ did not prevail.”

But his indictments confounded the Nazi legal bureaucracy. In the end, the only recourse was to lose them. They were locked in a desk and forgotten.

#history#antisemitism#law#crime#justice#holocaust#germany#nazi germany#josef hartinger#arthur kahn#ernst goldmann#rudolf benario#erwin kahn#hilmar wäckerle#concentration camps#dachau concentration camp

1 note

·

View note

Text

On that same April evening in 1933, Joseph Hartinger received a call that four men had been shot attempting to flee the recently erected detention facility. As a local prosecutor, it was Hartinger’s job to establish a commission to investigate all deaths resulting from “unnatural causes.”

The blood was still damp on the ground when Hartinger arrived. He sensed immediately that something was horrifically wrong. “My reasons were based not only on the physical circumstances but in particular on my assessment of the personalities I encountered in the camp and especially on my evaluation of the nature of the camp commandant Wäckerle, who made a devastating impression on me,” Hartinger recalled. “I also had to include in my deliberations the fact that those who had been shot were all Jews.”

When Hartinger reported that a serial killing of Jews had taken place, his superior responded unequivocally: not even the Nazis would do that. The investigation was terminated.

But as killings continued to mount, Hartinger persisted. On June 1, 1933, he issued indictments against the camp commandant and three other SS men. It was a brazen act of legal defiance to the regime. Hartinger was not naïve. He knew the Nazi capacity for violence. That evening, he told his wife, “I just signed my own death sentence.”

The murder indictments had a surprising impact. The commandant was removed. The killings stopped. Hartinger had hurled a legal wrench into the Nazi bureaucracy and singlehandedly paralyzed its homicidal impulse.

— The First Killings of the Holocaust

#timothy w. ryback#the first killings of the holocaust#history#antisemitism#nazism#crime#law#justice#holocaust#germany#nazi germany#josef hartinger#arthur kahn#ernst goldmann#rudolf benario#erwin kahn#hilmar wäckerle#concentration camps#dachau concentration camp

1 note

·

View note

Text

Nazis attempted to cover up their crimes in the Holocaust—and denial of the genocide persists to this day. Scholars say memorials—like this one in the former train station of Pithiviers, France, from which Jews were sent to death camps—are essential to fighting anti-Semitism. Photograph By Christophe Pitit Tesson, Pool/AFP Via Getty Images

How The Holocaust Happened In Plain Sight

Six Million Jews were Murdered Between 1933 and 1945. How Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party Turned Anti-Semitism into Genocide.

— By Erin Blakemore | Published: January 27, 2023

Six million Jews murdered. Millions more stripped of their livelihoods, their communities, their families, even their names. The horrors of the Holocaust are often expressed in numbers that convey the magnitude of Nazi Germany’s attempt to annihilate Europe’s Jews.

The Nazis and their collaborators killed millions of people whom they perceived as inferior—including Jehovah’s Witnesses, gay men, people with disabilities, Slavic and Roma people, and Communists. However, historians use the term “Holocaust”—also called the Shoah, or “disaster” in Hebrew—to apply strictly to European Jews murdered by the Nazis between 1933 and 1945.

No single statistic can capture the true terror of the systematic killing of a group of human beings—and given its enormity and brutality, the Holocaust is difficult to understand. How did a democratically elected politician incite an entire nation to genocide? Why did people allow it to happen in plain sight? And why do some still deny it ever happened?

A shop selling household goods and clocks on Pinkas Street in the Jewish Quarter of Prague, then part of Czechoslovakia. In many parts of Eastern Europe, anti-Semitism was rampant before the Holocaust and Jews were forced to live separately from the rest of the population. Photograph Via History & Art Images, Getty Images

After Germany invaded Poland in 1939, Polish Jews were forced into ghettos like this one in Warsaw. This image taken by an unknown German photographer was later exhibited at the war crime trials that sought to hold the Nazis and their collaborators accountable after the war. Photograph Via Bettmann, Getty Images

European Jews Before The Holocaust

By 1933, about nine million Jews lived across the continent and in every European nation. Some countries guaranteed Jews equality under the law, which enabled them to become part of the dominant culture. Others, especially in Eastern Europe, kept Jewish life strictly separate.

Jewish life was flourishing, yet Europe’s Jews also faced a long legacy of discrimination and scapegoating. Pogroms—violent riots in which Christians terrorized Jews—were common throughout Eastern Europe. Christians blamed Jews for the death of Jesus, fomented myths of a shadowy cabal that controlled world finances and politics, and claimed Jews brought disease and crime to their communities.

The Rise of Adolf Hitler

It would take one man, Adolf Hitler, to turn centuries of casual anti-Semitism into genocide. Hitler rose to power as leader of the National Socialist German Workers’ Party, also known as the Nazi Party, in the 1920s.

Hitler harnessed a tide of discontent and unrest in Germany, which was slowly rebuilding after losing the First World War. The nation had collapsed politically and economically, and owed heavy sanctions under the Treaty of Versailles. The Nazi party blamed Jews for Germany’s troubles and promised to restore the nation to its former glory.

Hitler was democratically elected to the German parliament in 1933, where he was soon appointed as chancellor, the nation’s second-highest position. Less than a year later, Germany’s president died, and Hitler seized absolute control of the country.

Born in Braunau am Inn, Austria, in 1889, Adolf Hitler was a skilled speaker and rose to power in Germany democratically. In the wake of its WWI loss, he blamed the country's economic woes on Jewish people and promised to restore Germany to glory. Photograph By Roger Viollet, Getty Images

The Early Nazi Regime

Immediately after coming to power, the Nazis promulgated a variety of laws aimed at excluding Jews from German life—defining Judaism in racial rather than religious terms. Beginning with an act barring Jews from civil service, they culminated in laws forbidding Jews from German citizenship and intermarriage with non-Jews.

These were not just domestic affairs: Hitler wanted to expand his regime and, in 1939, Germany invaded Poland. It marked the beginning of the Second World War—and the expansion of the Nazis’ anti-Jewish policies.

German officials swiftly forced hundreds of thousands of Polish Jews into crowded ghettoes, and with the help of locals and the German military, specially trained forces called the Einsatzgruppen began systematically shooting Jews and other people the regime deemed undesirable. In just nine months, these mobile murder units shot more than half a million people in a “Holocaust by bullets” that would continue throughout the war.

But Hitler and his Nazi officials were not content with discriminatory laws or mass shootings. By 1942, they agreed to pursue a “final solution” to the existence of European Jews: They would send the continent’s remaining Jews east to death camps where they would be forced into labor and ultimately killed.

Hitler dismisses U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt's appeal for peace in a speech before the Reichstag, Nazi Germany's parliament, on April 28, 1939. Months later, Germany invaded Poland. Photograph Via Universal History Archive, Universal Images Groyp/Getty Images

Genocide in Plain Sight

By characterizing their actions as the “evacuation” of Jews from territories that rightfully belonged to non-Jewish Germans, the Nazi operation took place in plain sight. Though thousands of non-Jews rescued, hid, or otherwise helped those targeted by the Holocaust, many others stood by indifferently or collaborated with the Nazis.

With the help of local officials and sympathetic civilians, the Nazis rounded up Jews, stripped them of their personal possessions, and imprisoned them in more than 44,000 concentration camps and other incarceration sites across Europe. Non-Jews were encouraged to betray their Jewish neighbors and move into the homes and businesses they left behind.

Prisoners at Buchenwald Concentration Camp, near Weimar, Germany, in April 1945, the year it was liberated. In the eight years Buchenwald was in operation, it housed between 239,000 and 250,000 prisoners, who were subjected to medical experiments and grueling forced labor. Photograph By Eric Schwab, AFP/Getty Images

Dachau, which opened near Munich in 1933, was the first concentration camp. Five others—Auschwitz-Birkenau, Chelmno, Belzec, Sobibor, and Treblinka—were designated as killing centers, where most Jews were immediately murdered upon arrival.

The killings took place in assembly-line fashion: Mass transports of Jews were unloaded from train cars and “selected” into groups based on sex, age, and perceived fitness. Those selected for murder were taken to holding areas where they were told to set aside their possessions and undress for “disinfection” or showers.

In reality, they were herded into specially designed killing chambers into which officials pumped lethal carbon monoxide gas or a hydrogen cyanide pesticide called Zyklon B that poisoned its victims within minutes.

The earliest Holocaust victims were buried in mass graves. Later, in a bid to keep the killings a secret, corpses were burned in large crematoria. Some Jews were forced to participate in the killings, and then were themselves executed to maintain secrecy. The victims’ clothing, tooth fillings, possessions, and even hair was stolen by the Nazis.

As Allied troops advanced near the end of the war, Germany sent prisoners on death marches from the western front to Dachau, near Munich. When the camp was liberated in April 1945, pictured here, U.S. troops encountered piles of dead bodies and survivors on the brink of death. Photograph By Roger Viollet, Getty Images

Life in the Camps

Those not chosen for death were ritually humiliated and forced to live in squalid conditions. Many were tattooed with identification numbers and shorn of their hair. Starvation, overcrowding, overwork, and a lack of sanitation led to rampant disease and mass death in these facilities. Torture tactics and brutal medical experiments made the camps a horror beyond description.

“It is not possible to sink lower than this; no human condition is more miserable than this, nor could it conceivably be so,” wrote Auschwitz survivor Primo Levi in his 1947 memoir. “Nothing belongs to us any more…if we speak, they will not listen to us, and if they listen, they will not understand. They will even take away our name.”

But despite almost inconceivable hardships, some managed to resist. “Our aim was to defy Hitler, to do everything we [could] to live,” recalled Majdanek and Auschwitz survivor Helen K. in a 1985 oral history. “He [wanted] us to die, and we didn’t want to oblige him.”

Jews resisted the Holocaust in a variety of ways, from going into hiding to sabotaging camp operations or participating in armed uprisings in ghettoes and concentration camps. Other forms of resistance were quieter, like stealing food, conducting forbidden religious services, or simply attempting to maintain a sense of dignity.

In 2005, the Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe, also known as the Holocaust Memorial, opened in Berlin, Germany. Below ground, an information center shares stories of the Holocaust's victims—which scholars say is essential to preventing history from repeating itself. Photograph By Gerd Ludwig, National Geographic Image Collection

The Aftermath of the Holocaust

As World War II drew to a close in 1944 and 1945, the Nazis attempted to cover up their crimes, burning documents, dismantling death camp sites, and forcing their remaining prisoners on brutal death marches to escape the advancing Allies.

They didn’t succeed: As they liberated swaths of Europe, Allied troops entered camps piled high with corpses and filled, in some cases, with starving, sick victims. The evidence collected in these camps would become the basis of the Nuremberg Trials, the first-ever international war crimes tribunal.l

In the war’s aftermath, the toll of the Holocaust slowly became clear. Just one out of every three European Jews survived, and though estimates vary, historians believe at least six million Jews were murdered. Among them were an estimated 1.3 million massacred by the Einsatzgruppen; approximately a million were murdered at Auschwitz-Birkenau alone.

Many survivors had nowhere to go. Poland had Europe’s largest Jewish population before the war, but lost 93 percent of that population in just five years. Entire villages and communities were wiped out and families scattered across Europe. Labeled “displaced persons,” survivors attempted to rebuild their lives. Many left Europe for good, emigrating to Israel, the United States, or elsewhere.

Top: Photographs of a man held captive at Auschwitz, the largest of the Nazi concentration camps established during the Holocaust. These images can be found inside the Menorah Jewish Center in Dnipro, Ukraine, which explores the past, present, and future of Jewish life. Photograph By Abbas, Magnum

Bottom: Six million European Jews were killed—and hundreds of thousands displaced—during the Holocaust. When the international community learned the extent of Nazi brutality during World War II, it became clear existing laws of war were inadequate for addressing these crimes. Photograph Via Bar Am Collection, Magnum Photos (Left) And Photograph Via Bar Am Collection, Magnum Photos (Right)

Holocaust Denial

Despite the enormity of evidence, some people sowed misinformation about the Holocaust, while others denied it happened at all. Holocaust denial persists to this day, even though it is considered a form of antisemitism and is banned in a variety of countries.

How to counter the hate? “Educating about the history of the genocide of the Jewish people and other Nazi crimes offers a robust defence against denial and distortion,” concluded the authors a of a 2021 United Nations report on Holocaust denial.

Though the number of Holocaust survivors has dwindled, their testimonies offer crucial evidence of the Holocaust’s horrors.

“The voices of the victims—their lack of understanding, their despair, their powerful eloquence or their helpless clumsiness—these can shake our well-protected representation of events,” said Saul Friedländer, a historian who survived the Holocaust and whose parents were murdered at Auschwitz, in a 2007 interview with Dissent Magazine. “They can stop us in our tracks. They can restore our initial sense of disbelief, before knowledge rushes in to smother it.”

#Holocaust#Six Million Jews | Murdered#Adolf Hitler#Germany 🇩🇪#Pinkas Street | Jewish Quarter | Prague | Czechoslovakia#Poland 🇵🇱 | Polish Jews | Ghettos | Warsaw#European 🇪🇺 Jews#Braunau am Inn | Austria 🇦🇹 | 1889 | Adolf Hitler#Nazi Regime#Genocide#Buchenwald Concentration Camp | Weimar | Germany 🇩🇪#Concentration Camps: Dachau | Auschwitz-Birkenau | Chelmno | Belzec | Sobibor | Treblinka#Holocaust Denial#Aftermath

0 notes

Text

I went to the Dachau memorial yesterday and GOD.

Dachau was the first and longest running concentration camp. It was the model for all the others to follow. It wasn’t the most deadly, not by far, but more than 40,000 people died for no reason in any case. And I think being the example only adds to just. Everything. I can’t put it into words.

Absolutely gut wrenching. When there wasn’t a tour group in the room it was almost dead silent. I cannot stop thinking about it. Jehovah’s Witnesses and Jews and gay people and emigrants and so so many people died there.

I have a couple more (I really tried to capture how large the place was for my history teacher) but there’s a 10 pic count on the mobile app. I’ve added explanations in the alt text to some of the photos if you’re confused on something.

#100% go see it#there are so many quotes from Nazis and American soldiers who liberated the camp#so SO many from prisoners#there are wedding photos and legal documents and replicas of personal belongings#it’s so tough to do but I think it’s important#dachau#concentration camps#nazism#nazi germany#history#germany

0 notes

Text

"Never Again" at the Dachau Concentration Camp memorial.

0 notes

Photo

0 notes