#Cosimo Recording Studio

Text

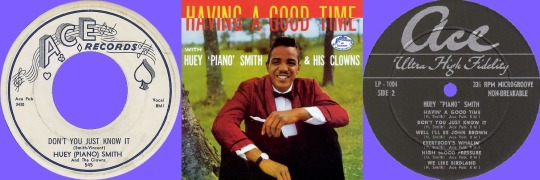

Huey "Piano" Smith and His Clowns - Don't You Just Know It (1958)

from:

"Don't You Just Know It" / "High Blood Pressure" (Single)

"Having a Good Time with Huey 'Piano' Smith & His Clowns" (LP | 1959)

R&B | New Orleans R&B | Rock and Roll

JukeHostUK

(left click = play)

(320kbps)

Personnel:

The Clowns: (Vocals)

Bobby Marchan

Geri Hall

"Scarface" John Williams

Huey "Piano" Smith: Piano

Robert Parker: Tenor Saxophone

Alvin Red Tyler: Baritone Saxophone

Frank Smith: Bass

Charles "Hungry" Williams: Drums

Produced by Huey "Piano" Smith

Recorded

@ Cosimo Recording Studio

in New Orleans, Louisiana USA

1957

Released:

on January 27, 1958

Ace Records

+++

Huey "Piano" Smith

1934 - 2023

+++

#Don't You Just Know It#Huey “Piano” Smith#Huey “Piano” Smith and His Clowns#New Orleans R&B#R&B#Ace Records#Cosimo Recording Studio#Louisiana Music#1950's#The Clowns

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Jimmy Page and Robert Plant at a party at Cosimo Matassa's Jazz City recording studio, May 14, 1973.

Before they left New Orleans, Atlantic Records boss Ahmet Ertegun threw a party for the band at Cosimo Matassa's Jazz City. Soul food comprised the menu that night and all of New Orleans' best R&B and rock legends would perform: Willie Tee, Art Neville and the Meters, Ernie K-Doe, the Wild Magnolias, Snooks Eaglin and the Olympia Brass Band. Rauls helped coordinate that party and remembers the event like it was yesterday.

"They didn't need some ritzy ballroom", he says. "Just going to a funky, soulful recording studio in a beat down part of New Orleans and to meet the guys they grew up listening to–they were in seventh heaven. Willie Tee was still alive, Ernie K-Doe was there, Professor Longhair–all these guys were former Atlantic artists that Ertegun had a relationship with. To bring them out at Cosimo's party, it gave the band a woody."

Davis writes of the party in Hammer of the Gods, "John Paul Jones played organ while a stripper bumped and grinded on the tabletop. Jimmy and Robert watched in awe as the elder statesman of rock and roll strutted their stuff."

#jimmy page#robert plant#led zeppelin#jimbert#john paul jones#john bonham#classic rock#rock#70s#1973#classic rock fandom#by dee dee 🌺🕯️

215 notes

·

View notes

Video

Paprika Plains - When You Wish Upon a Star from Luca Briganti M.P. on Vimeo.

#triphop #jazz #electronicmusic

“When You Wish Upon a Star” is the 4th single from the Italian artists Angelica Bucci and Giampiero Frulli, aka Paprika Plains.

Written by Harline & Washington, for the Disney animated movie “Pinocchio” (Victor, EMI, 1940)

Angelica Bucci - Voice & Choir Arrangement

Giampiero Frulli - Piano, Arrangement & Sound Design

Cosimo Galoppa - Sound Engineer

Mix & Mastering at Perfect Wave Studio

VIDEOCLIP

Perfect Wave Service - Backline Rent

Luca Briganti - Dop, Camera, Edit & Color Grading

℗ PW Records 2023

0 notes

Text

The Chinese generally!

Faking in China dates from at least the Sung Dynasty (960-1280) when the wealthy began to collect art. Forged paintings were mostly made by students seeking to imitate the masters. It still seems a common practice!

14th Century, Italian stone carvers:

The stone carvers lead the way in commercially forgery, faking works of art by imitating Greek and Roman master craftsmen and creating sculptures which could and were to be sold to the rich as authentic antiques! Much the same tale as that of their Roman counterparts.

Jacopo di Poggibonsi: (1418-1449) Italian

There are many contemporary critics at the University of Michigan who label Jacopo di Poggibonsi as a "master forger". This criticism stems from his purported imitation of the works of Fra Filippo Lippi which Cosimo de' Medici in about 1447 realised he had copied elements of, from an Adoration hanging in the Medici Palace. However, many artists of the time engaged in imitations of the earlier styles and after all, in translation from the French renaissance does mean, "rebirth." Clearly, many Renaissance artists not only imitated earlier forms of art, but also each other's recent works. It was standard practise.

History according to U of M has it however that Lippi was outraged and is believed to have hired paid muscle to track down di Poggibonsis' studio where more alleged copies were found.

A few days later, thirty-one year old Jacopo, is found murdered in his bed.

All in all a good story but sadly untrue.

Art History Students are advised to check this out very carefully. All may not be as it seems!

Piero del Pollaiuolo: (1443-1496) Italian

Made pastiches (copies) of works by artists such as Sandro Botticelli as illustrated here on the right.

His, Profile of a woman is a straight copy of Portrait of a Woman (La Bella Simonetta) and this reproduction is now housed in the Museo Poldi-Pezzoli in Milan.

Michelangelo di Ludovico di Lionardo di Buonarroti Simoni: (1475-1564) Italian

It's widely believed that the worlds greatest sculptor Michaelangelo as a student, forged an "antique" marble cupid for his patron, Lorenzo de' Medici.

It is certainly recorded that he also produced many replicas of the drawings of Italian painter Domenico Ghirlandajo (1449–1494) which were so good that on seeing them Ghirlandajo thought they were from his own hand. “He also copied drawings of the old masters so perfectly that his copies could not be distinguished from the originals, since he smoked and tinted the paper to give it an appearance of age. He was often able to keep the originals and return the copies in their stead.” Vasari on Michaelangelo

Colantonio

Neapolitan painter also known as Colantuono was appreciated as an imitator of the Flemish masters such as van Eyck and for making fake drawings by Dürer.

Marcantonio Raimondi: Italian (1480c. - 1534)

Interested in German engraving, he affected copper numerous woodcuts of Albrecht Dürer.

According to Vasari he made 17 copies of Dürer selling them as originals.

0 notes

Photo

Peripherie by rand is out! Today, a fabulous three years after the first recording sessions at Berlin's Chez Cherie studios, the time has finally come: We, Bogdan and Jan, are very happy and proud to present to you our album, which was also created with the help of a whole bunch of great people! We sincerely thank the fantastic and exuberantly patient Andrea Cichecki for mixing and mastering, Timo for the wonderful graphic design, Shai Levy for the beautiful photos, Cosimo Miorelli for the beautiful video painting and many more for their so positive vibes! Just as we believe in long-term artistic-musical work, these 9 tracks - 7 tracks on vinyl - are all expressions and results of that process and tell a very personal story of the past three years we have spent together. Being a musician means for us, today more than ever, to hear something inside, which then, in the best case, is strong enough to penetrate outside. Is the music strong enough in character to survive musically in this shark tank of musical diversity in this ever accelerating world? This requires a delicate balance of self-criticism, strength of character, courage and a lot of imagination. Bogdan and I have faced these challenges again and again with this album. And? We think we are strong! The results are precisely worked out, very individual and character-strong tracks, which carry our very personal signature! Torsos of post-romantic melodies thus stand for the somewhat lost human being, torn in and out of an environment of near-natural idyllic retreat and dystopian apocalyptic urbanity. The artwork finally, a detail of a drawing by Jan with the title Anhöhe (hill), fits exactly: our music sounds like these environments, whether the near-natural or the urban and illuminates especially acoustically-musically these supposed and often neglected corners and edges around us. (rand means egde) Sincerely, Bogdan and Jan @jangerdes @dr.nojoke #newreleases2022 #newmusic2022 #newalbum #debutalbum #vinyllove #vinylcollector #limitededition #stictlylimited #ambientmusic #electronicmusic #piano #jazz #electronica #minimalism #experimentalmusic #contemporarymusic #modernclassical https://www.instagram.com/p/CiR0MHtArof/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

#newreleases2022#newmusic2022#newalbum#debutalbum#vinyllove#vinylcollector#limitededition#stictlylimited#ambientmusic#electronicmusic#piano#jazz#electronica#minimalism#experimentalmusic#contemporarymusic#modernclassical

0 notes

Photo

Armonika @Cox18, Milano | Maggio 2022

DJ party, ambiente mistico, varietà performativo e riempi-pancia della domenica.

𝑨𝒓𝒎𝒐𝒏𝒊𝒌𝒂 è un ambiente per stare insieme, ascoltare storie tra i paralumi o seguire il groove sul dancefloor.

https://www.instagram.com/armonika_party/

https://www.facebook.com/armonikaparty

Nel suo quarto episodio, dalle ore 16 live, DJ set, performance & cena:

✻ 𝑯𝒆𝒂𝒓𝒕 𝑶𝒇 𝑺𝒏𝒂𝒌𝒆 Live

è un rituale essoterico ideato da Vincenzo Marando (Vernon Selavy, Movie Star Junkies, Krano) in combutta con Alberto Danzi e Cosimo Rosa, pubblicato nel 2018 dalla Maple Death Records e portato in diversi contesti e festival come Handmade, Here I Stay, Holidays, Muviments con collaborazioni in studio e dal vivo con Julie Normal, Maria Violenza, Dario Bruna, Foxhound, Vittorio Demarin (Father Murphy), Michele Guglielmi (Jooklo XXL)

https://mapledeathrecords.bandcamp.com/album/s-t-2

✻ 𝑩𝒍𝒂𝒅𝒆𝒃𝒍𝒂𝒏𝒄 DJ set

Bladeblanc is a Milan-based producer, DJ, and multimedia artist who works in the field of digital art with her project Ultracare. She already appeared on influential labels such as Heel.Zone and Eco-Futurism Corporation with her mixture of bass music and post-club which she skillfully collapses in mutant sound chimeras often turning to the darkest side of the spectrum. Mainly inspired by the UK underground scene, she commits to the dancefloor by combining bass and Jungle with grime-ish sounds, a pinch of post-internet exploration, and sharp drumline patterns.

https://soundcloud.com/bladeblanc

✻ 𝑺𝒆𝒓𝒑𝒊𝒄𝒂 𝑵𝒂𝒓𝒐 Camouflage

Serpica Naro organizza laboratori, iniziative e fa ricerca sociale in particolare intorno ai concetti di proprietà intellettuale, soggettività nelle industrie creative, lavoro e precarietà nella moda.

https://www.serpicanaro.com/

✻ 𝑹𝒂𝒃𝒊𝒊 𝑩𝒓𝒂𝒉𝒊𝒎 Live Improv

Fondatore della compagnia Corps Citoyen, Milano Mediterranea e nuovo membro di Addict Ameba. Spirito poliedrico e ben vestito.

https://milanomediterranea.art/

✻ 𝑬𝒍𝒍𝒂𝒉 𝑩𝒐𝒖𝒏𝒄𝒆 Live Vocals

Tra vari esperimenti artistici in ambito musicale, letterario e teatrale, e l'ideazione di workshop terapeutici e/o espressivi con materiali visivi, realizza performance vocali dove intuizioni, pensieri, fantasie, si adattano a sonorità elettroniche.

✻ 𝑳𝒆𝒔𝒕𝒆𝒓 𝑴𝒂𝒏𝒏 DJ set

Seleziona musica d'ascolto di impronta dub, stranezze disco, psichedelia e ritmi per danze rallentate, da diversi anni organizza concerti e feste nel sottobosco milanese. In duo, con il nome di Lester Laura, è stato resident per le serate Wan Va in Cox18, Nessuno (Nobodys Indiscipline Party) e ha curato una serie di podcast per Radio Quartiere durante il primo lockdown del 2020.

https://www.mixcloud.com/lester_mann/

✻ 𝑴𝒂𝒕𝒕𝒊𝒂 𝑫𝒂𝒎𝒃𝒓𝒐𝒔𝒊𝒐 DJ set

Cuore pulsante della surf band Wave Electric, guitar hero e animale notturno, seleziona beat caldi, dubby techno e disco hit.

https://instagram.com/mattdambrosio87

✻ 𝑭𝒓𝒆𝒅𝒅𝒚 𝑨𝒎𝒐𝒓𝒖𝒔𝒐 Live Armonica

Bending sfrenati di armonica, improvvisa sul groove dei dischi suonati durante la festa.

✻ 𝑭𝒆𝒅𝒆𝒓𝒊𝒄𝒂 𝑨𝒎𝒐𝒓𝒖𝒔𝒐 Vocalist

Fondatrice della rivista Tutto Oggi, vocalist occasionale, ci aggiornerà sulle previsioni metereologiche dei prossimi giorni.

https://instagram.com/vere.cundia

✻ 𝑬𝒎𝒎𝒂𝒕𝒐𝒎𝒂 Mani di Fata

Creatrice di ambienti mistici, costumi lucenti e atmosfere di altri mondi.

https://instagram.com/eesti.juust

✻ 𝑴𝒂𝒓𝒌𝒐 𝑩𝒖𝒌𝒂𝒒𝒆𝒋𝒂 ???

Ci sara davvero?

--- in orario aperitivo ---

✻ 𝑮𝒓𝒂𝒏𝒅𝒎𝒂𝒔𝒕𝒆𝒓 𝑳𝒆𝒍𝒆 Cibo & Cuore

--- + special thanks to ---

✻ 𝑺𝒂𝒍𝒊 Moment Catcher

✻ 𝑳𝒂 𝑺𝒊𝒎𝒐 General Manager

✻ 𝑳𝒊𝒍𝒍𝒚 𝑮𝒓𝒖𝒎𝒐 Spirito Guida

1 note

·

View note

Text

#john bonham#led zeppelin#drums#led zep#drummer#over the hills and far away#the song remains the same#old hyde farm#physical graffiti#in through the out door#1973#ahmet ertegun#atlantic records#cosimos studios

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

Lucrezia Buti (Florence, 1435; died in the sixteenth century) was an Italian nun, and later the lover of the painter Fra Filippo Lippi. She is believed to be the model for several of Lippi's Madonnas.

Lucrezia was born in Florence in 1435, the daughter of Francesco Buti and Caterina Ciacchi. She became a nun in the Dominican monastery of Santa Margherita in Prato. According to Vasari, while a novice or boarder at the monastery, she met the painter Fra Filippo Lippi who in 1456 had been commissioned to paint a picture for the nuns' high altar. Lippi requested Buti as a model for the Virgin in the painting he was creating for them.

Lippi fell in love with Buti during her sittings for the painting and caused a great scandal by kidnapping her from a procession of the Girdle of Thomas in Prato and took her to his nearby home. Despite attempts to force her to return to the monastery, Buti remained at Lippi's house at the piazza del Duomo.

Vasari records in his Lives of the Artists that in 1456 Fra Filippo while working in Prato, tended to frequent young women and indulge in countless romantic adventures. But it was one particularly comely young woman for whom he fell hard for.

It was in Prato while working on frescos to decorate the church of S. Margherita where he met and fell in love with the beautiful Lucrezia Buti, the daughter of Francesco Buti, a Florentine silk merchant. Lucrezia was born and raised in Florence, but after the death of her parents, Lucrezia was sent to Prato and placed under the protection of the Sisters of Santa Margherita.

The first time Fra Filippo saw Lucrezia at the convent, he thought her face exquisite, and he knew she would be the perfect model for the Madonna for his altarpiece. Right away, he asked the sisters for permission for Lucrezia to sit for him in his studio where he could paint her portrait.

In 1457, Buti bore Lippi a son, Filippino, and in 1465 a daughter, Alessandra. Through the intervention of Cosimo de' Medici, the couple received a dispensation to marry from Pius II, but according to Vasari, Lippi declined to marry Buti.

The couple remained together, and it was only several years later that Pope Pius II, thanks to the intercession of Cosimo de’ Medici, Fra Filippo, was granted an exemption to marry Lucrezia and to regularize their relationship.

Lucrezia is traditionally thought to be the model for Lippi's Madonna and Child, and Salome in his fresco cycle of the Stories of St. Stephen and St. John the Baptist in the cathedral of Prato.

#perioddramaedit#history#edit#history edit#lucrezia buti#fra filippo lippi#madonna with the child#salome#art#art history#anastasia tsilimpiou#caterina ciacchi#donne nella storia#donne italiane#donne della storia#donneitaliane#renaissance women#italian renaissance#renaissance art#women in history#francesco buti#15th century#madonna and child#filippo lippi#artist#renaissance painting#renaissance aesthetic#renaissance italy#florence#cosimo de medici

54 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Ever been to the Cabildo in New Orleans? to quote Earl Palmer, “I invented this shit.”

0 notes

Photo

Part two of the Cinderella AU! A few notes, just before we get started --

Although this story’s setting includes magic and fictional countries, its overall aesthetic is strongly based on the early Renaissance, most specifically 1550′s France and Italy, around the time of the Italian Wars. Therefore the palace of Royaume where Carewyn works is very evocative of French palaces such as Versailles and the Chateau de Chambord -- this room she’s pictured in above, in particular, is based on the Queen’s Chambers in Versailles. In this written section and in the picture of Orion above, we also see a secret passage in the palace of Florence, based off Italy’s Palazzo Vecchio, which also features an entire maze of passages. As another example, Orion’s real first name, “Cosimo,” is an Italian derivative of the name Cosmas, meaning “order” or “decency.” One of the most well-known historical bearers of the name was Cosimo de Medici, who founded the Medici political dynasty in the real-world Italian province of Florence and was a large patron of the arts during the Renaissance. “Henri,” Andre’s real first name, likewise references King Henry II of France.

Because this is a more fantasy-based setting, the songs Carewyn sings won’t just have historical links, but might also be references to other Cinderella adaptations. In this case, “The Sweetest Sounds” was originally written for Rodgers and Hammerstein’s play No Strings, but was later featured in the 1997 film adaptation of Rodgers and Hammerstein’s Cinderella. (Which, for the record, is one of the best Cinderella adaptations ever made -- go watch it.) “Sing Sweet Nightingale” is from Disney’s original animated version of Cinderella, which -- fun fact -- just like Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs made thirteen years earlier in 1937, saved the studio from bankruptcy. Sonnet 29 by William Shakespeare is slightly anachronistic here, as even if it’s from the Renaissance, it was likely published in the 1590′s...but I think if you read the words, you might see why I included that musical cover for Carewyn in this AU.

Carewyn, even in her canon, does have unusually narrow feet! Her size is an 8 narrow. It’s a problem that my maternal grandmother struggled with her entire life, especially while growing up during the Great Depression.

Previous part is here -- full tag is here -- and featuring in this part alongside many HPHM characters is Katriona “KC” Cassiopeia, who belongs to my friend @kc-needs-coffee! Make sure to send some love her way, yes?

x~x~x~x

Within several weeks, Carewyn had settled into life at the palace of Royaume. Although the workload was a lot more extensive than it was at home simply due to the amount of beds she had to make, floors she had to sweep and wash, surfaces she had to polish, and rooms she had to clean, it was truthfully a lot more pleasant of a work environment for Carewyn. She didn’t mind working hard or having high expectations put upon her -- at least she could do her work in peace, without her vile cousins going out of their way to walk right across the floor she’d just finished cleaning with dirty shoes so she’d have to start all over again.

One thing Carewyn did notice, however, was that the castle staff was rather limited, for how large the palace was. She saw a few other maidservants in passing, but by and large, she ended up cleaning entire wings of the castle by herself. Yet she never complained, and that only endeared her more to the royal family and the castle staff. There were times when the royal chamberlain -- an elderly, but sharp-eyed man with a full white beard named Albus Dumbledore -- amusedly remarked that the maidservant must have a kind of magic all her own, for her to get so much done without any help. Although Dumbledore himself meant it metaphorically, it was a rumor that flitted through the palace more seriously among the rest of the staff. After all, how else could someone so tiny reach the crystal chandeliers well enough to clean them better than anyone else had, all by herself? One such person who heard the rumors was castle guard Bill Weasley, and he found out the answer to that question one day on his way back from a meeting with the King and Queen.

Upon catching the sound of someone singing a familiar tune on the other side of a closed door, Bill curiously opened it and peeked into the Queen’s bedchambers. There he found tiny ginger-haired Carewyn balancing on top of the decorated mantle along the wall so that she could polish the crystal chandelier by hand. She’d tied up the long skirt of her burnt-orange-and-beige dress with her red hair ribbon just enough that she wouldn’t have to worry about tripping, showing off a pair of very worn, slightly-too-big cloth slippers. Even though she was dressed in a maidservant’s uniform with her hair loose and was in a position no noble lady would be caught dead in, her face was made-up and she balanced on the edge of the mantle with remarkable grace.

Once Bill got over his initial surprise, the castle guard couldn’t help but grin in both amusement and a bit of admiration. When Carewyn caught sight of Bill in the doorframe, she froze like a startled cat and her song immediately died in her throat.

��It’s all right!” said Bill. “Don’t stop on my account.”

Carewyn didn’t respond, instead just watching the taller man carefully as she lowered her hand and cleaning cloth from the chandelier. Sensing her nerves despite her stoic expression, Bill offered her a gentler smile.

“Would you like me to get you a ladder?” he asked.

Carewyn’s eyes drifted away, as was often the case when she was uncomfortable, but her expression remained proud.

“No, thank you,” she said quietly. “I can manage.”

Bill walked over and extended a hand to her. “At least let me offer you some help getting down.”

Carewyn looked down at his hand and then up at his face. Her expression softening ever-so-slightly, she came down into a seated position on the mantle, accepted his hand, and then leapt nimbly down into a nearby chair and back down to the floor.

“Thank you, sir,” she said politely.

“No problem,” said Bill with a full smile of his own. “Only, no need to call me ‘sir.’ The name’s Bill -- Bill Weasley, of his Majesty’s guard. And you’d be Carewyn, right?”

Carewyn raised an eyebrow at him as she bent down and untied the red ribbon from her skirt.

“Do I already have such a reputation that it precedes me?”

Bill laughed. “Wow, that’s some upper-crust-level talk! I guess people are right to call you ‘the little lady.’”

He grinned a bit more mischievously. “I have to admit, though...I didn’t reckon I’d find someone called that climbing up into such high places with so little effort. Weren’t you scared of falling?”

Carewyn tied her hair back into a modest ponytail, her gaze once again absently drifting away toward the corner of the room.

“Not particularly. I used to have to climb up on the counters in the kitchen, when ere I had to clean above the cabinets. And the tower windows were too high for me to reach, so I’d have to climb on the furniture and then up onto the windowsills to wash them.”

Bill raised his eyebrows, looking both surprised and slightly impressed. “Didn’t have a ladder then, either?”

“Not one I could access, or that anyone would give me, were I to ask. But it was truly not that much trouble,” she added quickly, seeing Bill’s face. “They were things that needed doing, and I was the only one to do them -- so I found a way.”

Carewyn dipped her cleaning cloth in a bucket of water on the floor, wringing it dry before returning to the mantle to clean it.

Bill glanced around the Queen’s Chambers. Carewyn had temporarily moved a marble bust, vase, and candelabra that no doubt were on the mantle to the floor so she could climb up and clean, but otherwise the room was pristine, with everything from the bed linens to the floor looking like it had never been touched.

Bill looked back at Carewyn, who’d had to go up onto her tiptoes to better reach the back of the mantle. The castle guard couldn’t help but notice how her too-large shoes kept sliding off her feet and frowned slightly.

“...What size do you wear?” he asked before he could stop himself.

Carewyn looked up, startled. Bill flushed, rubbing the back of his neck awkwardly.

“It’s just -- I noticed your shoes don’t fit. Reckon that might be uncomfortable, and it’s probably not safe, if you’re climbing up on stuff, either. And well, you’re kind of around my mum and sister’s size -- so maybe one of them might have a pair of old shoes that might fit better...”

Carewyn’s surprise slowly melted away -- she actually looked rather touched.

“Thank you,” she said, “but I’m afraid shoes have never fit that well for me, even when they are the right size. They’re always too wide for my feet. My mother used to save up to have a cobbler measure my feet and make a nice pair of shoes fit to size when I was young...but it was always rather expensive even for a child’s shoes, and it just wasn’t practical.”

She rubbed a particular spot on the mantle until it was shining again.

“Fortunately his Highness shares your concerns,” she said without turning around. “He’s actually nearly finished making a pair for me himself.”

“Really?” said Bill, surprised.

“Yes -- though I think it’s because these shoes so thoroughly offended his aesthetic sensibilities,” Carewyn added with a wry smile.

Bill burst out laughing. “That sounds about right!”

Carewyn finished polishing the mantle and set about returning the candelabra to its original spot, going up onto her tiptoes and sliding it back into place. Before she could reach the bust, Bill had strolled over and picked it up, putting it back on the mantle for her.

“Does it go here?” he asked.

Once she’d recovered from her surprise, Carewyn offered the tall guard a grateful smile.

“...Just a little to the left.”

She picked up the vase off the floor, and Bill took it from her and put it up on the mantle too.

From that day on, Bill Weasley was Carewyn’s friend. In the following weeks, he was joined by Bill’s brother Charlie, who served as a castle carpenter. When Charlie came up to fix the door on an ornate armoire in one of the guest suites, he collided with Carewyn, who was making the bed. The two ended up working side by side, talking and singing songs to pass the time. The cheeriness of Carewyn’s singing also helped her earn the friendship of the court artist Badeea Ali, who started positioning herself beside open windows or hallways so that she could listen to Carewyn singing while she worked on her paintings. Before long, it wasn’t too uncommon to catch Carewyn singing a song and Charlie and Badeea echoing it from other rooms a ways away.

“Oh sing, sweet nightingale...sing, sweet nightingale...”

The royal family of Royaume soon grew accustomed to hearing Carewyn singing while they went about their business too. The prince’s second cousin, the Lady Katriona Cassiopeia, in particular, was pleasantly surprised when she realized Carewyn (who’d been washing the library windows at the time) was singing a sonnet from a book she’d read, and the two ended up having a very nice conversation about both the sonnet and other books that they’d read and enjoyed. Andre took to leaving doors open so that he could catch Carewyn singing whenever he was walking from room to room, though his fencing instructor Erika Rath would rather pointedly slam the door closed to shut out all sound while they were training.

“No distractions, Prince Henri,” Erika said rather bluntly.

Andre deflated slightly. Andre’s current opponent -- a stocky, strong-shouldered noblewoman with auburn hair, dark blue eyes and copious freckles dressed in formal fencing gear -- immediately lashed out with her blade, and Andre was forced to block her.

“She’s right, Andre. Carewyn has a lovely voice, I know...but if you’re going to end up on the battlefield at any point, you can’t afford to get complacent.”

Andre gave an over-dramatic sigh. “‘If’ I do...KC, you know I never get to go anywhere -- ”

“And that’s probably just as well,” Lady Katriona, or KC, said levelly, before adding a bit more sourly under her breath, “considering they’ll have all the more reason to retaliate, after the hit we put out on their previous Crown Prince...”

“It was an eye for an eye, as far as I’m concerned,” said Erika rather bluntly. “Our King was killed first -- by a witch they protected, may I add.”

“Heated emotions don’t make for successful war strategy,” KC reminded her.

She and Andre parried their swords, but it didn’t take long for Andre to disarm her.

"Oh, for heaven’s sake -- ” KC swore under her breath.

“My turn,” said Erika dryly.

Her and Andre’s fight was much more aggressive and skilled from the off-set -- Erika was clearly very talented with a blade.

“What would you have proposed then, coz?” Andre asked KC over his shoulder. “I’m not saying I approve of it...but Father chose that plan with the thought that it would dishearten Florence and make them reluctant to keep fighting.”

“Yes, but a lack of strong leadership also makes predicting the enemy’s next moves that much harder,” KC said as she sat herself down in a nearby chair. “Florence’s new heir may be the king’s son, but he’s the child of a peasant, born out of wedlock -- a bastard, who by all accounts was raised in poverty...and therefore someone who likely doesn’t know the in’s and out’s of court politics and could very well end up becoming a pawn in someone else’s chess match. And that someone else definitely won’t be us.”

“A shame it can’t be -- ow!”

Erika successfully disarmed Andre by smacking his hand hard with the hilt of her sword. Even while nursing his hand, though, the Crown Prince of Royaume was smiling.

“Damn -- good show, Erika.”

Meanwhile, in the palace of Florence, the entire royal court had been assembled for a meeting. While the King led his troops in battle, the court wished to discuss a possible military strategy that Florence’s new heir, Prince Cosimo Orion Amari, could then employ on the front lines.

The man with the most authority and investment in the proceedings was the Lord Lucius Malfoy, who was not only the wealthiest royal courtier, but also the most connected -- and he had a proposal to end the War once and for all.

“Our enemies have shown time and again how much they fear the magical arts,” said Lord Malfoy. His voice was sardonic and well-articulated enough to linger on certain consonants. “It’s the one tool they are too cowardly to use -- and when we have the potential for such power at our disposal, would it not be prudent to use it to end the War once and for all?”

The courtiers murmured amongst themselves. Orion glanced around the table. His associates -- Sir Murphy McNully and Lady Skye Parkin -- were both frowning deeply from their seats on either side of him, but the few noblemen who looked wary of Lord Malfoy’s suggestion seemed too afraid to speak in opposition to it.

Orion’s hands clasped in front of him on the table as he surveyed the blond-haired Lord calmly.

"I didn’t know we were turning away any magical aid that had been offered to us,” he said. “Lady Haywood has saved many lives, with her potion remedies. And Master Snape has conjured very impressive illusions, to hide our troops during retreats.”

Orion inclined his head respectfully to the black-dressed court magician standing off to the side. There was a satisfied glint in the man’s black eyes, but otherwise his face remained very stony.

“No one is discounting Severus’s talents,” said Lord Malfoy, inclining his head a bit more curtly in Snape’s direction, “but it seems there is far more that one could do with it. However short-lasting the effects are, magic can still make a dramatic impact and potentially cause lasting damage...”

“Damage?” repeated Orion, his level voice never rising even though his eyebrows did. “Lord Malfoy, I’m no magician...but if I’m not mistaken, magic’s central purpose is to protect, not to harm. Isn’t that why we shielded the fugitive from Royaume so many years ago, when she was first accused of murdering their King?”

Lord Malfoy gave a smile that didn’t touch his gray eyes in the slightest. “In principle, yes -- but there are magics that are more aggressive, and more powerful.”

“Dark magic, do you mean?” asked Orion, his eyes narrowing ever-so-slightly.

Lord Malfoy reacted dismissively. “The Royaumanians already see all magic as black magic -- even the weaker kinds we use now. Does it really matter how they view our methods, particularly if it helps us achieve peace? And truly, can one really argue that we wouldn’t be protecting our nation -- our people -- our way of life -- by attacking full-force? The best defense is a strong offense...and don’t we want this conflict to come to an end quickly, before even more of what we hold dear is lost?”

“You mean like your wealth?” Skye couldn’t stop herself from muttering sourly under her breath in Orion’s ear.

Orion shot her a muted warning look out the side of his eye, before turning his focus back to Lord Malfoy.

“...You make a good argument, Lord Malfoy,” he said quietly. “However...I do not think the King would approve of any strategy that involves the use of dark magic. And both you and I must respect the King’s wishes.”

Lord Malfoy looked incredibly displeased.

“Prince Cosimo,” he said, his lips once again curled up in a cold smile as his gray eyes bore into Orion, “the King is a bit stuck in his ways -- you needn’t follow his will simply because it’s his -- ”

“I never said I was,” Orion cut him off very calmly.

He rose to his feet.

“Thank you all for your time. This meeting is adjourned.”

Lord Malfoy’s lip curled, but he nonetheless was forced to respectfully incline his head as Orion left the room, Skye walking and McNully rolling in his wheeled chair behind him.

“He’s getting bolder,” growled Skye. “He’d only ever hint that we should use dark magic before...”

“I daresay he thought the odds of success would be higher with you than with the King,” said McNully. “Which, yes, I suppose they were...but not high enough that I would’ve risked it.”

“That’s because you know me, McNully,” Orion said patiently. “Lord Malfoy does not. And for now, I’m content to let him underestimate me.”

“Don’t underestimate him either, though, Orion,” McNully warned him under his breath. “Lord Malfoy has a lot of influence over the court. I’d say a good 49% of them are in his pocket financially, and he’s scared another 39% of them into line through other means. And even if you’re heir now, you’re still not safe.”

“Right,” said Skye, her narrowed eyes more openly grim and anxious. “There are a lot of those creeps who don’t even feel like you’re worthy of being here. You should hear the things they call you behind your back -- ‘the Bastard Prince’ -- ‘the Royal Tramp’ -- ‘the Spare Heir’ -- ”

She looked like she wanted to spit nails, but Orion looked remarkably unfazed.

“I can’t control what other people think of me, only what I myself do,” he said levelly. “All I can hope is that by bringing the War to an end on my terms, in a way that brings balance and heals old wounds, I can prove cynical people like Lord Malfoy wrong. Peace is a plant that must be given the space, water, and sunshine needed to grow -- cruelty can’t cultivate a field, however much force might be used to plow it.”

The three had reached a certain hallway. Orion stopped in the middle of it, his black eyes darting from side to side to check that they were alone, before he approached the wall, just between a set of oil paintings.

Skye and McNully both sighed out of frustration and amusement.

“Sneaking out again?” said McNully.

Orion smiled. “Yes. I still seek openings in the wall built around Royaume’s heart -- and just as with individuals, the only way to know a group of people is to be among them.”

He lifted part of the wall aside to reveal a secret door, which he propped open enough to walk behind and start up the exposed stone staircase.

“And I suppose you just expect us to look the other way while you hightail it off into enemy territory again?” asked Skye, her own lips curled up in a smirk.

Orion’s black eyes glittered with mischief and his free hand came up to unbutton the stifling collars of his navy blue doublet and white undershirt as he let the door fall closed behind him.

McNully’s eyes rolled up toward the ceiling. “I’d better go get the coach ready so I can follow him.”

#hphm#hogwarts mystery#cinderella au#my art#my writing#carewyn cromwell#orion amari#bill weasley#charlie weasley#badeea ali#skye parkin#murphy mcnully#katriona cassiopeia#lucius malfoy#penny haywood#severus snape#yes orion's wearing his canon necklace under his doublet! X3#and I friggin' love him in a ponytail jiiiiii#next part: we'll get to see more of carewyn's family the cromwells and learn more about both her friends outside the palace and her history#and of course orion and carewyn will collide again soon as if there was any question of that#funnily enough I also used to climb up on the counters a lot though it was often to fetch things from the top shelf I couldn't reach#I always gave my mum a heart attack XDDD#even in canon I see little!carewyn doing it when she got home before her mum and had to look after herself at home for an hour or so#god I hate doing backgrounds DX

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

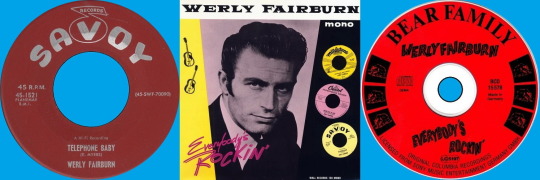

Werly Fairburn - Telephone Baby (1957)

E. Myers

from:

"Telephone Baby" / "No Blues Tomorrow" (Single)

"Werly Fairburn: Everybody's Rockin"

(1993 Bear Family Records Compilation)

"Rock-A-Billy Dynamite"

(2013 Box Set | CD23)

Rockabilly

JukeHostUK

(left click = play)

(320kbps)

Personnel:

Werly Fairburn: Vocals / Guitar

Joe Martin: Bass

Eddie Landers: Drums

Unknown: Piano

Recorded:

@ The Cosimo Recording Studio

in New Orleans, Louisiana USA

August, 1957

Released:

on September 9, 1957

Savoy Records

♫♫♫ ♫♫♫ ♫♫♫

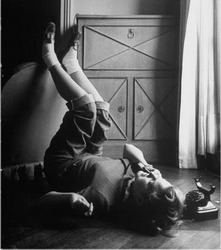

"Telephone baby, with your feet up on the wall"

Photograph by Gordon Parks, 1951

Gordon Parks:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gordon_Parks

#Rockabilly#Werly Fairburn#1950's#Cosimo Recording Studio#Savoy Records#Popular Culture#E. Myers#Gordon Parks#Telephone Baby

5 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Enrico Caruso was born on February 25, 1873. He was an Italian operatic tenor. He sang to great acclaim at the major opera houses of Europe and the Americas, appearing in a wide variety of roles (74) from the Italian and French repertoires that ranged from the lyric to the dramatic. One of the first major singing talents to be commercially recorded, Caruso made 247 commercially released recordings from 1902 to 1920, which made him an international popular entertainment star.

Caruso's 25-year career, stretching from 1895 to 1920, included 863 appearances at the New York Metropolitan Opera before he died at the age of 48. Thanks in part to his tremendously popular phonograph records, Caruso was one of the most famous personalities of his day, and his fame has endured to the present. He was one of the first examples of a global media celebrity. Beyond records, Caruso's name became familiar to millions through newspapers, books, magazines, and the new media technology of the 20th century: cinema, the telephone and telegraph.

Caruso toured widely both with the Metropolitan Opera touring company and on his own, giving hundreds of performances throughout Europe, and North and South America. He was a client of the noted promoter Edward Bernays, during the latter's tenure as a press agent in the United States. Beverly Sills noted in an interview: "I was able to do it with television and radio and media and all kinds of assists. The popularity that Caruso enjoyed without any of this technological assistance is astonishing."

Caruso biographers Pierre Key, Bruno Zirato and Stanley Jackson attribute Caruso's fame not only to his voice and musicianship but also to a keen business sense and an enthusiastic embrace of commercial sound recording, then in its infancy. Many opera singers of Caruso's time rejected the phonograph (or gramophone) owing to the low fidelity of early discs. Others, including Adelina Patti, Francesco Tamagno and Nellie Melba, exploited the new technology once they became aware of the financial returns that Caruso was reaping from his initial recording sessions.

Caruso made more than 260 extant recordings in America for the Victor Talking Machine Company (later RCA Victor) from 1904 to 1920, and he and his heirs earned millions of dollars in royalties from the retail sales of these records. He was also heard live from the stage of the Metropolitan Opera House in 1910, when he participated in the first public radio broadcast to be transmitted in the United States.

Caruso also appeared in two motion pictures. In 1918, he played a dual role in the American silent film My Cousin for Paramount Pictures. This film included a sequence depicting him on stage performing the aria Vesti la giubba from Leoncavallo's opera Pagliacci. The following year Caruso played a character called Cosimo in another film, The Splendid Romance. Producer Jesse Lasky paid Caruso $100,000 each to appear in these two efforts but My Cousin flopped at the box office, and The Splendid Romance was apparently never released. Brief candid glimpses of Caruso offstage have been preserved in contemporary newsreel footage.

While Caruso sang at such venues as La Scala in Milan, the Royal Opera House, in London, the Mariinsky Theatre in Saint Petersburg, and the Teatro Colón in Buenos Aires, he appeared most often at the Metropolitan Opera in New York City, where he was the leading tenor for 18 consecutive seasons. It was at the Met, in 1910, that he created the role of Dick Johnson in Giacomo Puccini's La fanciulla del West.

Caruso's voice extended up to high D-flat in its prime and grew in power and weight as he grew older. At times, his voice took on a dark, almost baritonal coloration. He sang a broad spectrum of roles, ranging from lyric, to spinto, to dramatic parts, in the Italian and French repertoires. In the German repertoire, Caruso sang only two roles, Assad (in Karl Goldmark's The Queen of Sheba) and Richard Wagner's Lohengrin, both of which he performed in Italian in Buenos Aires in 1899 and 1901, respectively.

Repertoire

Caruso's operatic repertoire consisted primarily of Italian works along with a few roles in French. He also performed two German operas, Wagner's Lohengrin and Goldmark's Die Königin von Saba, singing in Italian, early in his career. Below are the first performances by Caruso, in chronological order, of each of the operas that he undertook on the stage.

World premieres are indicated with **.

L'amico Francesco (Morelli) – Teatro Nuovo, Napoli, 15 March 1895 (debut)**

Faust – Caserta, 28 March 1895

Cavalleria rusticana – Caserta, April 1895

Camoens (Musoni) – Caserta, May 1895

Rigoletto – Napoli, 21 July 1895

La traviata – Napoli, 25 August 1895

Lucia di Lammermoor – Cairo, 30 October 1895

La Gioconda – Cairo, 9 November 1895

Manon Lescaut – Cairo, 15 November 1895

I Capuleti e i Montecchi – Napoli, 7 December 1895

Malia (Francesco Paolo Frontini) – Trapani, 21 March 1896

La sonnambula – Trapani, 25 March 1896

Mariedda (Gianni Bucceri [it]) – Napoli, 23 June 1896

I puritani – Salerno, 10 September 1896

La Favorita – Salerno, 22 November 1896

A San Francisco (Sebastiani) – Salerno, 23 November 1896

Carmen – Salerno, 6 December 1896

Un Dramma in vendemmia (Fornari) – Napoli, 1 February 1897

Celeste (Marengo) – Napoli, 6 March 1897**

Il Profeta Velato (Napolitano) – Salerno, 8 April 1897

La bohème – Livorno, 14 August 1897

La Navarrese – Milano, 3 November 1897

Il Voto (Giordano) – Milano, 10 November 1897**

L'arlesiana – Milano, 27 November 1897**

Pagliacci – Milano, 31 December 1897

La bohème (Leoncavallo) – Genova, 20 January 1898

The Pearl Fishers – Genova, 3 February 1898

Hedda (Leborne) – Milano, 2 April 1898**

Mefistofele – Fiume, 4 March 1898

Sapho (Massenet) – Trento, 3 June (?) 1898

Fedora – Milano, 17 November 1898**

Iris – Buenos Aires, 22 June 1899

La regina di Saba (Goldmark) – Buenos Aires, 4 July 1899

Yupanki (Berutti)– Buenos Aires, 25 July 1899**

Aida – St. Petersburg, 3 January 1900

Un ballo in maschera – St. Petersburg, 11 January 1900

Maria di Rohan – St. Petersburg, 2 March 1900

Manon – Buenos Aires, 28 July 1900

Tosca – Treviso, 23 October 1900

Le maschere (Mascagni) – Milano, 17 January 1901**

L'elisir d'amore – Milano, 17 February 1901

Lohengrin – Buenos Aires, 7 July 1901

Germania – Milano, 11 March 1902**

Don Giovanni – London, 19 July 1902

Adriana Lecouvreur – Milano, 6 November 1902**

Lucrezia Borgia – Lisbon, 10 March 1903

Les Huguenots – New York, 3 February 1905

Martha – New York, 9 February 1906

Madama Butterfly – London, 26 May 1906

L'Africana – New York, 11 January 1907

Andrea Chénier – London, 20 July 1907

Il trovatore – New York, 26 February 1908

Armide – New York, 14 November 1910

La fanciulla del West – New York, 10 December 1910**

Julien – New York, 26 December 1914

Samson et Dalila – New York, 24 November 1916

Lodoletta – Buenos Aires, 29 July 1917

Le prophète – New York, 7 February 1918

L'amore dei tre re – New York, 14 March 1918

La forza del destino – New York, 15 November 1918

La Juive – New York, 22 November 1919

Caruso also had a repertory of more than 500 songs. They ranged from classical compositions to traditional Italian melodies and popular tunes of the day, including a few English-language titles such as George M. Cohan's "Over There", Henry Geehl's "For You Alone" and Arthur Sullivan's "The Lost Chord".

On 16 September 1920, Caruso concluded three days of recording sessions at Victor's Trinity Church studio in Camden, New Jersey. He recorded several discs, including the Domine Deus and Crucifixus from the Petite messe solennelle by Rossini. These recordings were to be his last.

Dorothy Caruso noted that her husband's health began a distinct downward spiral in late 1920 after he returned from a lengthy North American concert tour. In his biography, Enrico Caruso Jr. points to an on-stage injury suffered by Caruso as the possible trigger of his fatal illness. A falling pillar in Samson and Delilah on 3 December had hit him on the back, over the left kidney (and not on the chest as popularly reported). A few days before a performance of Pagliacci at the Met (Pierre Key says it was 4 December, the day after the Samson and Delilah injury) he suffered a chill and developed a cough and a "dull pain in his side". It appeared to be a severe episode of bronchitis. Caruso's physician, Philip Horowitz, who usually treated him for migraine headaches with a kind of primitive TENS unit, diagnosed "intercostal neuralgia" and pronounced him fit to appear on stage, although the pain continued to hinder his voice production and movements.

During a performance of L'elisir d'amore by Donizetti at the Brooklyn Academy of Music on December 11, 1920, he suffered a throat haemorrhage and the performance was canceled at the end of Act 1. Following this incident, a clearly unwell Caruso gave only three more performances at the Met, the final one being as Eléazar in Halévy's La Juive, on 24 December 1920. By Christmas Day, the pain in his side was so excruciating that he was screaming. Dorothy summoned the hotel physician, who gave Caruso some morphine and codeine and called in another doctor, Evan M. Evans. Evans brought in three other doctors and Caruso finally received a correct diagnosis: purulent pleurisy and empyema.

Caruso's health deteriorated further during the new year, lapsing into a coma and nearly dying of heart failure at one point. He experienced episodes of intense pain because of the infection and underwent seven surgical procedures to drain fluid from his chest and lungs. He slowly began to improve and he returned to Naples in May 1921 to recuperate from the most serious of the operations, during which part of a rib had been removed. According to Dorothy Caruso, he seemed to be recovering, but allowed himself to be examined by an unhygienic local doctor, and his condition worsened dramatically after that. The Bastianelli brothers, eminent medical practitioners with a clinic in Rome, recommended that his left kidney be removed. He was on his way to Rome to see them but, while staying overnight in the Vesuvio Hotel in Naples, he took an alarming turn for the worse and was given morphine to help him sleep.

Caruso died at the hotel shortly after 9:00 a.m. local time, on 2 August 1921. He was 48. The Bastianellis attributed the likely cause of death to peritonitis arising from a burst subphrenic abscess. The King of Italy, Victor Emmanuel III, opened the Royal Basilica of the Church of San Francesco di Paola for Caruso's funeral, which was attended by thousands of people. His embalmed body was preserved in a glass sarcophagus at Del Pianto Cemetery in Naples for mourners to view. In 1929, Dorothy Caruso had his remains sealed permanently in an ornate stone tomb.

Daily inspiration. Discover more photos at http://justforbooks.tumblr.com

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

By: Amy Fredrickson

Artemisia Gentileschi was born on July 8, 1593, in Rome and is one of the most distinguished artists of her generation. She challenged the societal limitations placed on female artists during her time and became a successful history painter in her own right. Her career took her from Rome to Florence, Venice, London, and Naples, where she worked for elite patrons such as the Medici family in Florence and King Philip IV of Spain.

Artemisia was the eldest of Prudenzia Montoni and Orazio Lomi Gentileschi’s (1563–1639) five children as well as their only daughter. She was born into an artistic family. In addition to her father, her grandfather Baccio Lomi (c.1550–1595) and her uncle Aurelio Lomi (1556 – 1622) were well-known Pisan painters.

Originally a mannerist-style painter, Orazio became a follower of Caravaggio’s practice of working from nature, and he trained Artemisia to paint in this manner. As a child, Artemisia worked in his studio, mixing pigments and making varnishes. She learned the techniques of chiaroscuro, which was characteristic of Caravaggist paintings. In turn, Artemisia was a second-generation champion of Caravaggio’s realism; her first recorded paintings are almost indistinguishable from her father’s, such as Susanna and the Elders (1610). Painted a few years later, Judith and Her Maidservant (c.1614-20) in the Palazzo Pitti sets her apart from Orazio for its emotive protagonists and deep tenebrism.

Orazio hired painter Agostino Tassi (1578 – 1644) to tutor Artemisia. In the spring of 1611, Tassi raped her, and he refused to fulfill his promise to marry her. Orazio took him to trial because the crime against his daughter was a crime against his family’s honor. Artemisia’s infamous 1612 trial was well-documented and lasted seven months. She was forced to provide a testimony under torture. Found guilty, Tassi was sentenced to banishment from Rome for five months; however, his punishment was not enforced.

Shortly after, Artemisia married Florentine artist Pietro Antonio di Vincenzo Stiattes (b.1584), and they moved to Florence. Before their arrival, Orazio wrote to the dowager Grand Duchess of Tuscany, Christina of Lorraine, requesting her help in preventing Agostino Tassi's release from the Corte Savella where he was being jailed. In return, Orazio offered to send her one of Artemisia's paintings, Judith and Her Maidservant (c.1614-20).

Artemisia established herself as an independent artist in Florence, and she began developing her distinct style. She pushed against the societal norms established for women during her time, such as relegating women painters to the genre of still life or portraiture. Instead, she concentrated on history painting. She established herself within Florentine literary circles, which led to commissions from the Medici family and Michelangelo Buonarotti the Younger. She painted Judith and Holofernes (c. 1612–1621) and the Penitent Mary Magdalene (1620–1625) in the Palazzo Pitti for the Medicis, and for Casa Buonarotti, she painted a ceiling painting called the Allegory of Inclination (1615–1617). Her Florentine paintings illustrate her development beyond her father’s teachings and those of Caravaggio as she introduced a more polished surface, brighter colors, and sophisticated iconography. Perhaps these advances were a product of her association with the poets, painters, and intellectuals she had encountered in Florence. In 1616, Artemisia became the first female member of the Accademia delle Arti del Disegno.

Artemisia was business savvy; she ran her own studio and controlled her finances. The move to Rome may have coincided with Grand Duke Cosimo II de’ Medici’s death in 1621. His successor was Ferdinando, his ten-year-old son, who was governed by his mother and grandmother, and ultimately, their tastes leaned toward penitent biblical figures rather than Artemisia’s bloodletting heroines.

In 1620, Artemisia and her husband returned to Rome for approximately six years. Judith and her Maidservant (c. 1623-25), now in Detroit, dates to this time, although how many paintings Artemisia produced during her second Roman period is unclear. Little is known about her involvement in Roman artistic circles of this period, yet Simon Vouet’s portrait of Artemisia for the papal secretary Cassiano dal Pozzo provides some insight that she was associated with an elite circle of patrons and possibly the Academy of the Desiosi.

In 1627, Artemisia traveled to Venice for a few years to possibly attain commissions. During her Venetian sojourn, she participated in literary circles such as the Accademia degli Incogniti. Venetian poetry of this time alludes to her status in these circles. While in Venice, Artemisia began to specialize in monumental biblical and historic women; the subject of these paintings featured the triumphs and tragedies of these heroines.

In 1629, the Spanish viceroy, the Duke of Alcalá, invited Artemisia to Naples, and a year later, she resided in Naples and ran a successful studio. A remarkable example of this period is her Esther before Ahasuerus (1627-1630), which hints at her Venetian sojourn. The incorporated grandiose movements and ornamental dress emit an operatic air.

Her recently discovered paintings, such as Corsica and the Satyr (c. 1630-35) and Christ and the Samaritan Women (c. 1637), reveal that the 1630s marked a high point in her career. What sets these works apart from her earlier paintings are her lyrical subjects and the loose Venetian-inspired brushwork of broad white strokes with colors applied on top. During the 1630s, she began incorporating rich colors, such as ochres, blues, and cinnabar red. Artemisia created dimension and drama through her use of such rich hues.

Artemisia left Naples in 1638 to assist her ill father in London. Orazio worked for the English court beginning in 1626 and was working on ceiling paintings for the Great Hall in the Queen’s House in Greenwich. By 1640, she returned to Naples, where she remained until her death. It is unknown when she died, but a recently discovered document shows her living in Naples in August 1654. It is plausible that Artemisia died during the 1656 plague that had ravaged Naples and killed half of its inhabitants.

Images:

Self-Portrait as the Allegory of Painting, c.1630, oil on canvas, 96,5 x 73,7 cm., Royal Collection, Windsor

Susanna and the Elders, 1610, oil on canvas, 170 x 121 cm., Schloss Weissenstein, Pommersfelden

Judith and Her Maidservant, c.1614-20, oil on canvas, 114 x 93.5 cm., Galleria Palatina (Palazzo Pitti), Florence

Allegory of Inclination, c. 1615, oil on canvas (ceiling), 152 cm × 61 cm., Casa Buonarroti, Florence

The Penitent Mary Magdalen, 1620-25, oil on canvas, 146 x 109 cm., Galleria Palatina (Palazzo Pitti), Florence

Judith Beheading Holofernes, 1612-21, oil on canvas, 199 x 162 cm.,

Galleria degli Uffizi, Florence

Judith and her Maidservant, c. 1623–1625, oil on canvas, 184 x 141.6 cm., Detroit Institute of Art.

Esther Before Ahasuerus, c. 1627-1630, oil on canvas, 208.3 cm x 273.7 cm., Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Corsica and the Satyr, c.1630-35, oil on canvas, 155 x 210 cm., Private Collection.

Christ and the Samaritan Women, c. 1637, oil on canvas, 267.5 x 206 cm., Private Collection.

References:

Sheila Barker, 'Artemisia's Money: The Entrepreneurship of a Women Artist in Seventeenth-Century Florence,' Artemisia Gentileschi in a Changing Light, ed. by Sheila Barker (London, 2018), pp 59-88

Breeze Barrington, 25 April 2020, "The Trials And Triumphs Of Artemisia Gentileschi," Apollo Magazine. [online] <https://www.apollo magazine.com/artemisia-gentileschi-london/>

Ward R. Bissell, Artemisia and the Authority of Art: Critical Reading and

Catalogue Raisonné (University Park, 1999)

Ward R. Bissell,‘Artemisia Gentileschi-A New Documented Chronology,’ The

Art Bulletin 50, no. 2, (1968), pp. 153–168.

Patrizia Costa, ‘Artemisia Gentileschi in Venice’, Source: Notes in the History of Art 19, no. 3, (2000), pp. 28-36

Mary D. Garrard, 'Artemisia Gentileschi's 'Corisca and the Satyr,'' The Burlington Magazine 135, no. 1078 (1993), pp. 34-38

Mary D. Garrard, Artemisia Gentileschi: The Image of the Female Hero in Italian Baroque Art (Princeton, 1989)

Jesse Locker, Artemisia Gentileschi: The Language of Painting (New Haven, 2015)

#artemisia#artemisia gentileschi#florence#rome#caravaggisti#Caravaggio#Baroque Art#women artists#female artist#heroines#judith#judith and holofernes#susanna and the elders#self portrait

49 notes

·

View notes

Text

DR. JOHN BIO

“All my sisters married doctors”, said Dorothy Cronin Rebennack, the mother of Mac Rebennack. “ But only I had a Dr. John”. Indeed, there can be only one Malcolm Rebennack, aka “ Doctor John Creaux, the Night Tripper”. There can only be one walking repository of the storied city of New Orleans’ thriving musical history. There can be only one author of such classic songs as “ Right Place, Wrong Time”, “ Such A Night”, “Litanie Des Saintes”, and “I Walk On Gilded Splinters”. There can be only one torchbearer for the Crescent City sound as it second-lines its way into its fourth century. So Mrs. Rebennack was right -- physicians are indeed a dime a dozen in this doctor-clogged country; but a musician of her son’s caliber comes along but once in a very blue moon.

Malcolm John Rebennack Jr. was born in New Orleans a full month after term on Thanksgiving Day (November 20) 1942. Weighing a full ten pounds, Mac, as he came to be called, was born into a music-loving family in America’s most musical city. While still an infant, Rebennack starred as a model for various baby products, and showed remarkable musical ability in early childhood. By the age of three he was already hammering out melodies on the family piano, and soon exhausted the talents of the nun who was hired to give him lessons some years later. “If I play what his next lesson is going to be”, the sister complained, “he will play it right behind me, note for note”, His good-timing Aunt Andre, who it can be safe to assume had funkier taste than the nun, taught him the “Pinetop Boogie-Woogie”. My aunt was a groovy old broad”, Rebennack recalled in “Up from the Cradle of Jazz”. “I used to drive everybody mad playing it”.

Malcolm Rebennack Sr. was an appliance store owner who, as is traditional in New Orleans, also stocked the latest hit records. Thus young Mac was privy from early childhood to almost any music he wanted. Some years later the Rebennack appliance store was forced to close, and Mac lost his pipeline to the goldmine. But soon his father found work in a line even better suited to those of musical bent: PA system repair. The two Rebennacks would often be seen trundling in tandem to various nightclubs around town, bloodbucket dives with names like the Pepper Pot and the Cadillac Club. Always forbidden to enter the clubs, Mac would wait for his father to repair the system, and then peer in and dissect the musicians. It was at the Pepper Pot, in fact, and in this manner that Mac first saw Professor Longhair’s magical keyboard frolics.

At the age of seven Rebennack suffered through a bout of malaria. Even as a child, the over-modest Mac had decided that he could never cut it as a pianist in New Orleans. As he remembered wondering, “How was I going to complete with killer players like Tuts Washington? Salvador Doucette? Herbert Santina? Professor Longhair himself? And the list only began there”. He had, even before his illness, agitated to take up the guitar. His long convalescence enabled him to air his plea with such incessancy, such vehemence, that his beleaguered parents finally gave in. He was sent for instruction to Werlein’s Music Store on Canal Street, already at that time a New Orleans institution and still in business today. His teacher soon sussed that Mac was going to be a difficult, if talented student. The instructor delivered a verdict along the line of, “Good ear, will never learn to read music”. The fancy, store-bought lessons ceased forthwith; but Mac was still hard at it.

He locked himself in his room for weeks on end, learning by ear the licks of his twin idols of the time: T-Bone Walker and Lightning Hopkins. “If I can’t make it as T-Bone, I’ll try Lightning, he told himself. His father, seeing that his son had a talent and drive, and being himself connected in the music scene, made a wonderful decision. He persuaded Walter “Papoose” Nelson to instruct his son.

Papoose was Fats Domino’s lead guitarist (and the son of Louis Armstrong’s lead guitarist) and had long been a hero to Rebennack. As Mac recalled: “The first lesson, Papoose listened to my chops and said ‘Hey, man, you can’t play that shit and get a job. What are you, crazy? That outta-meter, foot-beater jive. You gotta play stuff like this’. Then he started playing legitimate blues, which I was on the trail of with T-Bone Walker. It was the Lightning shuffle that was off the wall as far as Papoose was concerned”.

Papoose’s primary contributions to Mac’s musical education were twofold. First, it was Nelson who finally won Mac over to the benefits of learning to read music. Second, to impart musical discipline, Nelson would force Mac to play rhythm guitar for hours on end, never allowing him a solo.

Mac’s next teacher, Roy Montrell, also imparted a valuable lesson. To his first lesson with this new teacher, Mac bounded in with his brand new guitar, “a cheap but flashy-looking green-and-black Harmony”. Roy took at the guitar and (said) ‘Why’d you bring this piece of shit over here?’ ‘It’s my guitar’, I said. ‘Give me that guitar’. He took it, walked outside into the backyard, laid it on the ground, picked up an axe, and split it right in half. Then he broke it in pieces and threw it in the neighbour’s yard”.

That done, he called Malcolm Rebennack Sr. on the phone and arranged for Mac to come back next week with a second-hand Gibson, an axe that Mac found himself working overtime with his father to pay for.

By the time Mac was on the cusp of his teens, he was a somewhat streetwise musician, hanging out in black clubs and scoring drugs in the projects for his older “junko partners”, or drug-buddies. Soon he was smoking pot himself, and in due course he progressed to pills, coke, and eventually junk. All the while, he was attending the south’s most prestigious Catholic high school, New Orleans Jesuit. In class, he daydreamed and wrote songs, which he would deliver to the offices at Specialty Records, and plotted gigs with several high school bands. Something had to give, and as one can imagine, it was school. He dropped out a year of graduation and later, while in prison, obtained a correspondence course diploma.

Not that in his lines of work he needed any such qualification. Soon he was a fully-fledged constituent of the New Orleans underworld. In addition to his burgeoning songwriting work, his session playing, and road gigs both local and regional, Mac attempted half-hearted sidelines such as pimping, forgery, and as an auteur of pornographic movies. His running buddies included street characters with names like Opium Rose, Betty Boobs, Stalebread Charlie, Buckethead Billy, and Mr. Oaks and Herbs. Meanwhile, he entered into a star-crossed, drug-sodden marriage to Lydia Crow. Lydia, though no shrinking violet herself, did attempt to go straight from time to time. But Mac would hear nothing of it, and their marriage ended by 1961.

His personal life a shambles, Mac’s professional life was faring better. He was kicking serious ass in the studio, and it is his guitar one still hears today on Professor Longhair’s, “Mardi Gras in New Orleans”. Mac-penned tunes like “Losing Battle” (a hit for Johnny Adams) and “Losing Battle” (recorded by Jerry Byrne) (the same song?) were just two of his fifty compositions recorded in New Orleans between 1955 and 1963. But (as is well-known today) the record companies of the 1950’s were not exactly ready coughers-up of royalties, so most of Mac’s compensation came from his sessions, gigs, and mostly ludicrous street tough sidelines. One such example of the corruption of the New Orleans music business of the ‘50s will suffice. Rebennack wrote a song entitled, “Try Not To Think About You” which languished unrecorded in the offices at Specialty Records for a while. Unrecorded, and more importantly, uncopyrighted. It eventually came to the attention of Lloyd Price, who changed the title to “Lady Luck”, switched record labels, and changed the composer’s name to - you guessed it - Lloyd Price. It would have been Rebennack’s biggest hit up to that date. After literally stalking Price, gun in hand (Mac planned on wasting him backstage after a show) for some time, he finally cooled off and chalked it up to bitter experience. An absurd coda ensured, when Rebennack’s parents unknowingly hired Price’s own attorney to sue Price for the royalties from “Lady Luck”. The lawyer, Mac related, “pocketed the change and did nothing. for a minute, I was afraid if I ever ran across that bastard, I’d kill him, too”.

Such chicanery aside, New Orleans of the 1950s was a paradise for musicians. Always a wide-open town (by American standards), the Crescent City was never more raucous and hard-partying than it was then. Gigs abounded in the all-night bars, bordellos, tourist joints, society haunts, and neighborhood taverns. That Rebennack was far ahead of his time regarding race helped him find work, but also earned him some less-enlightened enemies on both sides of the color line. He began to run into flak from the two musician’s union (one black, one white) for having the temerity to play with opposite-hued musicians.

Eventually these unions and the crusading, publicity-seeking New Orleans District Attorney Jim Garrison were to conspire to run Rebennack and most of the rest of the New Orleans music scene right out of town. The union began levying exorbitant fines on Rebennack (officially for playing scab sessions) and blacklisting record producers (like the legendary Cosimo Matassa) who dared to buy the latest equipment. Their short-sighted thinking was that new equipment would equal less studio time instead of more polished records and bigger hits. Garrison, for his part, launched a crusade on vice which closed down the thriving whorehouses and gambling dens, both important sources of income for both the music and tourist industries.

Rebennack’s troubles were only beginning. A fracas with a Jacksonville, Florida hotelier resulted in Rebennack getting the ring finger shot nearly off his left hand. Doctors reconstructed the finger to a degree, but not to the point that would enable him to resume making a living with a guitar. He was forced into playing bass with the tourist-oriented French Quarter Dixieland bands, a gig that convulsed him with boredom. He sank deeper than ever into heroin, and it was then that his marriage ended. To top it all, he was busted by Garrison’s goons for heroin possession, a charge that was to send him eventually to a Federal prison hospital in Fort Worth, Texas. There he served as a guinea pig for the various and infamous rehabilitation experiments then -as now - rampant in the land. He was released embittered but not in the least rehabilitated.

He returned briefly to New Orleans and was given some pointers on the organ from Crescent City keyboard maestro James Booker. However, he soon soured on Garrison’s Brave New Orleans and at the invitation of an old friend (saxophonist/arranger Harold Battiste) flew out to Los Angeles. A contingent of New Orleans musicians had already set up shop in the City of Angels, and Rebennack fell quickly to work doing studio odd jobs under the auspices of Battiste. Battiste was the brains (ahem) behind Sonny & Cher, and was a close associate of Phil Spector. Battiste mortared Rebennack in on some of Spector’s sessions, but Mac did not enjoy being just another brick in the ‘Wall of Sound’. He called it, “a monument to waste with echo all over the place! It was just padding the payroll, as far as I could see”.

He held down a brief stint as Frank Zappa’s pianist, but found that stultifying as well. This gave him an entrée into the acid rock world, in his words, “all these little acid groups springing up like mutant fungus after a chemical spill”. He attempted to work with Iron Butterfly, whom he termed “Iron Butterfingers” and Buffalo Springfield to little if any effect. A frustrating term as in-house producer with Mercury Records followed, but Rebennack and his cohorts suspected that it was just a tax dodge. He was more musically frustrated than he had ever been in New Orleans, and his drug woes continued unabated. As a parolee, he was under the watchful eyes of a great many government agencies as well. But slowly, the concept was forming that was to take him to heights he wouldn’t have dared dreamt possible.

Growing up in New Orleans, Rebennack had eagerly immersed himself in the City’s myriad native traditions and home-grown Afro-Latin religions. He himself was a half-hearted practitioner of gris-gris, New Orleans’ own unique branch of the voodoo tree. In his avid studies of the history and religion of the city, he had thrilled to the stories of John Montaigne aka Bayou John aka and most frequently, Dr.John. John was a Senegalese of self-proclaimed royal lineage who had been taken from Africa by slavers to Cuba. There he won his freedom, and shipped out as a sailor before eventually choosing to settle in New Orleans. He set up shop as a shaman, telling fortunes, healing, and selling a cornucopia of hexes. He was good at his job, and eventually prospered to the point where he even owned slaves himself. The kicker for Rebennack was coming across an account of a 19th Century vice bust in which John was arrested with one Pauline Rebennack for voodoo-related offences and suspicion of operating a whorehouse. For years, Mac had felt a spiritual kinship for Dr.John, and this account raised the quite possibility that one of his family had had the same feelings.

Even so, the idea that Rebennack had been ruminating cast his friend Ronnie Barron in the roll of Dr. John. But when the project was finally greenlighted, Barron had other contractual duties and Rebennack reluctantly assumed the mantle himself. Between Sonny & Cher sessions, virtually on the sly, Rebennack recorded the “Gris Gris” album with a band of New Orleans natives. Atlantic executive Ahmet Ertegun was at first displeased with the move. “Why did you give me this shit”?, Rebennack remembers Ertegun bellowing. “How can we market this boogaloo crap”? Eventually the canny Ertegun sniffed something in the late-’60s zeitgeist that could enable an off-the-wall act like Dr.John to sell, and he (to Rebennack’s surprise) released the album.

On “Gris Gris”, Rebennack played very little keyboard, contributing only organ parts on two tracks (“Mama Roux” and Danse Kalinda”). His aim was to introduce America to New Orleans’ mystical side, and also to “let us musicians get into a stretched-out New Orleans groove”. The album sold well enough to appease the suits, with very little backing, and meanwhile Rebennack’s fertile mind was cooking up a killer road show. Drawing on the venerable southern minstrel tradition and the pageantry of the Mardi Gras Indians, Dr.John and the Night Trippers’ road show boasted snake-festooned dancers, magic tricks, and costumes manufactured from the carcasses of virtually every living creature that ever crawled, slithered or flew in the bayou country. As Rebennack recalled, “When this stuff started coming apart in pieces, I had to start hanging around taxidermy shops big-time, scavenging new material.”

He and his similarly attired band of New Orleans roughnecks unleashed this act the acid-drenched southern California of 1968 to no little astonishment. But by the time “Babylon”, the Night Tripper’s second album came out, the band began to dissolve. Rebennack (along with the most of the rest of America) felt the end time was at hand, as the title implies. The album reflects Rebennack’s chaotic personal life - his drug use and police persecution, his dissolving band -- and the state of American life in 1968, a year in which it seemed that violet revolution was at hand. It was a year in which both Bobby Kennedy and Martin Luther King fell to assassins, riots consumed black ghettos in flames from Miami to Watts, and the Vietcong launched the ferocious TET offensive. The album features odd time signatures (11/4, 5/4,10/4), doom-laden lyrics, and hybrid Afro-Caribbean/avant-garde jazz feeling. As Rebennack later said, “ It was as if Hieronymus Bosch had cut an album”. Who better to chronicle those disorderly times?

Things were about to get extremely untidy for Rebennack again, as well.

While touring in support of “Gris-Gris”, the Night Trippers had been busted in St. Louis, and Rebennack as frontman shouldered the load. A lawyer arranged a deal in which Charlie Green (the manager of Sonny & Cher and Buffalo Springfield) was to pay off the St. Louis bail bondsman. The bondsman, unbeknownst to Rebennack, never collected. Green and partner Brian Stone then confronted Rebennack with the proverbial “Offer you can’t refuse”. Since he had gotten Rebennack sprung, Green put it to Mac, we get to manage you from now on. Rebennack, frazzled, saw no alternative.

Green proved to be the worst of all managerial archetypes, the would-be star. Mac recalled, “He thought of himself as the star and me as the roadie of the operation. Even though I wasn’t on no kind of star trip or nothing, I didn’t want my manager hanging around, running some kind of Jumpin’ Jack Flash number and trying to upstage me. Beyond that was the basic problem: a drugged out band hooked up with a starry-eyed manager results in a chemically unbalanced situation and, in general, a fearsome sight to behold.”

While at work on “Remedies”, the third of five of Rebennack’s Atlantic releases, Green and Stone persuaded Rebennack to check himself into a loony-bin, with an eye toward having him declared incompetent. This move would allow them to help themselves to a slightly higher percentage of Rebennack’s earnings than their current 25%, something more along the lines of 100%. Rebennack quickly wised up, escaped from the asylum, and exiled himself to Miami. Meanwhile, the managers had released the unfinished “Remedies” album. One of Rebennack’s chief aims for the album was to spread the news about Louisiana’s notorious Angola Farm, then as now America’s most deplorable and inhumane prison. Rebennack, incommunicado in Miami, was thus unable to put wise the Rolling Stone reviewer who took his lament Angola Anthem to be a protest song about the nation of Angola.

A disastrous European tour followed, one in which was Mac was hamstrung by a third string band (most of the Night Trippers were unable to get visas). The tour was augured in by Mac from backstage the electrocution death of the Stone the Crows guitarist Les Harvey at a festival. At Montreux, his bass player without warning dropped his bass and brandished a trombone which he had concealed in the wings, and proceeded to (Rebennack related) “start dancing around the stage, playing Pied Piper to the audience’s mountain villagers”.

At the end of this arduous road, Mac headed for London to round up session players for the album “The Sun, Moon, and Herbs”. Graham Bond, Eric Clapton, Ray Draper, Walter Davis Jr., Mick Jagger, Doris Troy, and a battery of drummers from virtually every West African and Caribbean country were on hand for a days-long, Opium and hash-fuelled epic of a session. He delivered the finished article to Green for post-production work a happy man.

Some weeks later, Rebennack returned to find his beloved album chopped, diced, and filleted by Green. Material was added and deleted, more was overdubbed. Most of what Rebennack felt was the best music was simply gone. In addition, it came to his attention (when he was alerted to a pair of bounty hunters at his doorstep) that Green had not, in fact, bailed him out of anything. Green was summarily dismissed, and Rebennack and some engineers endeavored to salvage what they could of the “Sun, Moon, and Herbs” album.