#CRISPR-Cas9

Text

Maiali geneticamente modificati virus resistenti

Questi maiali potrebbero essere i primi animali geneticamente modificati sulle nostre tavole. Sono resistenti a una malattia che provoca danni miliardari all’industria suinicola e secondo Science potrebbero invadere il mercato alimentare.

In agricoltura il dibattito sugli organismi geneticamente modificati è ormai vecchio, per quanto sempre attuale. Se parliamo di animali, invece, inizia ad entrare nel vivo solo in questi anni. Fino a poco tempo fa, infatti, non esistevano animali geneticamente modificati (gm) approvati per il consumo umano.

Le cose però stanno cambiando velocemente (almeno in America), e grazie alle nuove possibilità messe in campo da Crispr-Cas9, i tempi sembrano ormai maturi per l’arrivo della prima specie gm di rilevanza zootecnica destinata ad una diffusione mondiale: una razza di maiali modificata per resistere al virus della sindrome respiratoria e riproduttiva dei suini, sviluppata dall’azienda inglese Genus con l’ambizione di eliminare nel giro di qualche decennio questa malattia, che provoca ogni anno danni miliardari all’industria del maiale. Vediamo meglio di cosa si tratta.

La malattia

La sindrome respiratoria e riproduttiva dei suini (o Prrsv) è una malattia virale che colpisce i maiali ed affini, e provoca due sintomatologie principali: infertilità e problemi riproduttivi, e disturbi respiratori che possono colpire animali di tutte le età, ma che risultano particolarmente gravi (e spesso letali) nei cuccioli.

È stata identificata negli anni ‘80, e nei decenni seguenti ha raggiunto praticamente ogni angolo del globo, fino a rappresentare il principale pericolo infettivo per gli allevatori di maiali, con danni per il comparto stimati intorno ai 2,7 miliardi di dollari l’anno.

A causarla sono due virus, Prrsv-1 e Prrsv-2 appartenenti al gruppo degli Arteriviridae. Le strategie di prevenzione farmacologica attualmente consistono principalmente nell’utilizzo della vaccinazione, che però non risultano particolarmente efficaci, perché i due virus hanno un’elevata capacità di mutare, riducendo velocemente l’utilità dei vaccini.

Ad oggi, quindi, un’epidemia di Prrsv in un allevamento procura quasi certamente grosse perdite, che richiedono tempi lunghi e il sacrificio di molti capi di bestiame per essere controllate. È per questo, che il mercato per una razza di maiali immuni alla malattia è considerato dagli esperti particolarmente promettente.

Prevenzione genetica

I due artesivirus che causano la Prrsv utilizzano un recettore chiamato CD 163 come porta d’ingresso per infettare le cellule dei maiali. E un esperimento dell’università del Missouri di qualche anno fa ha dimostrato che è possibile rendere immuni i maiali eliminando artificialmente il recettore in questione: fortunatamente, per farlo è sufficiente colpire un singolo gene, e questo rende quindi possibile effettuare facilmente la modifica (o più correttamente il knockout del gene, visto che basta silenziarlo) utilizzando Crispr-Cas9.

Partendo da queste ricerche, Genus, un’azienda inglese specializzata nella selezione genetica di animali da allevamento, ha testato la fattibilità della tecnica sperimentata dai ricercatori dell’università del Missouri, su scala commerciale.

Le modifiche genetiche sono state effettuate su quattro animali, e dopo le verifiche del caso, necessarie per accertarsi che la procedura fosse andata a buon fine e non avesse causato la comparsa di tratti indesiderati, questi sono stati fatti incrociare per ottenere un popolazione di partenza con cui produrre una nuova razza di suini adatti all’allevamento, e immuni alla sindrome respiratoria e riproduttiva dei suini.

Le loro fatiche sono descritte in un articolo pubblicato sul Crispr Journal, e stando agli esami effettuati dagli scienziati dell’azienda avrebbero prodotto esemplari perfettamente sani e indistinguibili da animali non geneticamente modificati, che presentano tutti il knockout (cioè l’inattivazione) di entrambe le copie di CD 163.

A detta dei suoi creatori, i nuovi maiali gm hanno ottime chance di trasformarsi nei primi animali modificati geneticamente con ampia diffusione nel mercato zootecnico. Tutti gli allevatori – ragionano alla Genus – vorranno probabilmente mettersi al riparo dai rischi economici legati alla malattia, e le modifiche apportate potrebbero essere più “digeribili” per i consumatori rispetto ad altre viste in passato, perché in qualche modo mimano processi che possono avvenire naturalmente (il silenziamento di un gene) e non prevedono la creazione di organismi transgenici (cioè l’aggiunta di geni prelevati da altre specie). Resta da vedere quale opinione esprimerà al riguardo l’Fda, principale interlocutore dell’azienda in questa fase, che dovrebbe presentare la richiesta di approvazione per i suoi maiali nell’arco dei prossimi mesi.

Altri esempi

In Europa, per ora, non esistono ancora animali geneticamente modificati approvati per il mercato alimentare. Diversa invece la situazione negli Stati Uniti, dove i precedenti sono già due. Il primo è stato un salmone transgenico approvato nel 2015 per il consumo umano (primo animale al mondo) e sviluppato per incrementarne taglia e velocità di crescita, in modo da ridurre i costi di produzione e l’impatto ambientale degli impianti di acquacoltura.

Il pesce è un salmone atlantico, modificato inserendo nel suo Dna un gene che regola la produzione dell’ormone della crescita prelevato da un’altra specie imparentata, il salmone reale, e un gene promotore proveniente da un pesce della famiglia delle Zoarcidae. Il risultato, è un salmone atlantico che raggiunge in metà del tempo la taglia utile per la vendita, e che però dal 2021, quando è iniziata effettivamente la produzione, non ha ancora ottenuto risultati apprezzabili sul mercato americano e canadese (i due paesi in cui è attualmente disponibile).

Il secondo animale è un maiale conosciuto con il nome commerciale di Galsafe, approvato nel 2020 per il consumo umano e l’utilizzo nel campo degli xenotrapianti. I maiali Galsafe sono ingegnerizzati per bloccare la produzione di uno zucchero conosciuto come galattosio-alfa-1,3-galattosio (o alfa-gal) sulla membrana delle loro cellule, che può provocare reazioni allergiche anche gravi in persone che soffrono della cosiddetta allergia alla carne, o sindrome alfa-gal, associata alla puntura di alcuni tipi di zecche.

Per ora, i maiali in questione sono stati utilizzati unicamente per il prelievo di organi indirizzati agli xenotrapianti (che spesso nel caso di organi di maiale provocano rigetto proprio per la reazione dell’organismo allo zucchero alfa-gal). Ma nel corso del 2024 dovrebbe iniziare anche la commercializzazione alimentare, indirizzata al mercato degli allergici alla carne.

A fianco si due già approvati, la lista di quelli in attesa o in procinto di arrivare alla meta è relativamente affollata. Ci sono maiali modificati per essere sterili, in modo da potervi impiantare cellule staminali prelevate da un altro esemplare maschio con cui fargli produrre sperma (e quindi cuccioli) dalle caratteristiche genetiche desiderate (questa tecnologia sviluppata dalla Washington State University ha incassato per ora un’autorizzazione “investigazionale”).

Una specie di vacche modificate per avere un pelo corto e un’elevata resistenza al caldo, in modo da prosperare anche con le temperature sempre più elevate dei prossimi decenni. Maiali che non hanno bisogno di essere castrati. Vacche che producono solo cuccioli di sesso maschile. E molti altri.

La ricerca, al pari dell’industria, sembra pronta a sfruttare le nuove opportunità offerte da Crispr per rivoluzionare l’allevamento del bestiame, con la speranza di renderlo più economico, meno inquinante, e più resistente ai cambiamenti climatici e alle malattie. Non sempre, soprattutto in occidente, l’opinione pubblica condivide tanto ottimismo.

Uno scetticismo che per ora si riflette nelle normative con cui sono regolati. In Europa, lo dicevamo, le leggi Ue, piuttosto stringenti, non hanno ancora permesso la commercializzazione di alcun animale modificato geneticamente. In America sono lievemente meno restrittive, ma prevedono comunque gli stessi step di approvazione richiesti ai farmaci.

E questo allunga, e rende molto costosa, la strada da percorrere per giungere ad un’approvazione. Altri grandi mercati, come quello cinese o quelli di molte nazioni sudamericane, non si fanno gli stessi scrupoli, e potrebbero dare una spinta decisiva nei prossimi allo sviluppo di queste nuove tecnologie.

Read the full article

#alfa-gal#artesivirus#cellulestaminali#Crispr-Cas9#maiali#ogm#Prrsv-1#Prrsv-2#sindromerespiratoria#zootecnica

0 notes

Text

A New RNA Editing Tool Could Enhance Cancer Treatment - Technology Org

New Post has been published on https://thedigitalinsider.com/a-new-rna-editing-tool-could-enhance-cancer-treatment-technology-org/

A New RNA Editing Tool Could Enhance Cancer Treatment - Technology Org

The new study found that an RNA-targeting CRISPR platform could tune immune cell metabolism without permanent genetic changes, potentially unveiling a relatively low-risk way to upgrade existing cell therapies for cancer.

An artistic image depicting a CAR-T cell.

Cell therapies for cancer can be potentially enhanced using a CRISPR RNA-editing platform, according to a new study published in Cell. The new platform, Multiplexed Effector Guide Arrays, or MEGA, can modify the RNA of cells, which allowed Stanford University researchers to regulate immune cell metabolism in a way that boosted the cells’ ability to target tumors.

Lead author and Stanford graduate student Victor Tieu was interested in improving chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T cell therapy. In this cancer treatment, T cells – a type of white blood cell – are engineered with the CAR protein, a receptor that allows the cells to better track down cancer cells. While CAR T therapy has successfully treated blood cancers, including lymphomas and multiple myeloma, the engineered immune cells haven’t stacked up well against solid cancers such as pancreatic and lung cancers.

That’s because solid tumors have a bulkier structure for the immune cells to penetrate – the cells grow exhausted before they can make headway in destroying tumors. T cells evolved to fire up quickly and attack viruses, which means they often burn through their energy stores too soon when fighting cancer. “We were really interested in how we can make those cells better to improve clinical outcomes,” said Tieu. “A lot of the tools that we have right now just aren’t that good.”

The researchers tested their tool on CAR T cells in lab cultures with tumor cells and in mice with cancer. “Our finding is that it performs 10 times better, in terms of reducing the tumor growth and in terms of sustaining long term T cell proliferation,” said senior author Stanley Qi, Stanford associate professor of bioengineering and institute scholar at Sarafan ChEM-H.

Stopping cell exhaustion

Previous research efforts to improve CAR T cell therapy have used CRISPR-Cas9 to edit the cells’ DNA. However, this gene-editing platform comes with risks because it permanently deletes bits of DNA, which can have unintended consequences and even cause the T cells themselves to turn cancerous.

So the Stanford team pursued a different route, exploring whether CRISPR-Cas13d – which uses a molecular scissor that cuts RNA, not DNA – could enable reversible changes to gene expression in T cells. Unlike Cas9, Cas13d can easily target multiple genes at the same time – in the paper, the researchers demonstrated they could make 10 edits at once to human T cells. “RNA is the next layer up from DNA, so we’re not actually touching any of the genetic code,” said Tieu. “But we’re still able to get big changes in gene expression that are able to change the behavior of the cell.”

To see whether this tool could successfully improve CAR T cell function, they identified 24 genes that could be involved in the T cell exhaustion. They then tested 6,400 paired gene combinations in culture, with different genes turned down using the MEGA tool, and identified new gene pairings that worked especially well together to boost anti-tumor function.

Turning T cells into marathon runners

In another experiment, the team tuned a set of metabolic genes in the T cells to tilt the cells from sprinters to marathon runners, giving them the endurance to chip away at tumors. They compared these MEGA CAR T cells to non-engineered T cells and CAR T cells, both in lab cultures with tumor cells and in mice with cancer. After three weeks, they tested the extent of the tumors as well as how the T cells were surviving.

At first, the MEGA cells lagged in their anti-cancer activity. “Initially, I was like, ‘Oh, these cells are worse,’” said Tieu. But, after some time, these cells persevered against the tumor cells while the CAR T and regular T cells wore themselves out, leading to the 10-fold improvement in tumor growth reduction and T cell proliferation.

The secret was shifting how the cells spent their sugar, away from a fast-burning glycolysis process toward favoring oxidative phosphorylation. “We were able to use this technology to engineer the mRNAs in this sugar-usage pathway inside the T cells that regulate their choice of which sugar molecule to use,” said Qi. As a result, “We were able to really sustain the persistence of these T cells, so the T cell could live longer in the tumor site, and also exert much better performance.”

Not only did the MEGA platform allow for fine-tuning genes regulating T cell metabolism, the tune-up could also be regulated with a drug. When an antibiotic called trimethoprim was present, it turned on the RNA changes, tamping down on the cells’ glycolysis metabolism and turning them into endurance athletes in their attack on the tumor cells. When the drug was gone, the cells reverted to their original gene expression. This drug-based control mechanism “allows you to create a safety switch” for immunotherapy treatments, said co-author Crystal Mackall, the Ernest and Amelia Gallo Family Professor and a professor of pediatrics and of medicine at Stanford.

While the platform is still in its early stages, the researchers hope that it can eventually prove useful in clinical settings. Tieu plans to continue development of the platform toward this goal. “It would be really cool to try to push this to an actual clinical product,” he said. “I think there’s a lot of potential to really improve CAR T cell therapy in ways that people couldn’t have done before.”

Source: Stanford University

You can offer your link to a page which is relevant to the topic of this post.

#antibiotic#antigen#Arrays#Behavior#bioengineering#Biotechnology news#blood#Cancer#cancer cells#cancer treatment#cell#cell therapies#cell therapy#Cells#change#code#CRISPR#CRISPR-Cas9#crystal#development#DNA#DNA & RNA#drug#Editing#energy#Engineer#Featured life sciences news#gene editing#gene expression#genes

0 notes

Text

Precision Medicine Unleashed: The Impact of Gene Therapies on Neuromuscular Health

In the realm of medical breakthroughs, nucleic acid and gene therapies are emerging as promising avenues for revolutionizing the treatment landscape of neuromuscular disorders. From approved therapies to groundbreaking advancements in the pipeline, the trajectory of treating conditions like Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy (DMD) and Spinal Muscular Atrophy (SMA) is witnessing a transformative…

View On WordPress

#CRISPR-Cas9#Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy#Gene Therapies#Gene Therapy#Neuromuscular Disorders#Neuromuscular Disorders Treatment#Nucleic Acids#Nucleic Acids And Gene Therapies In Neuromuscular Disorders#Precision Medicine#Spinal Muscular Atrophy

0 notes

Text

Genetic Discoveries and the Revolution of Gene Editing Technologies

Genetics and gene editing technologies have brought about a transformative revolution in the field of biology and medicine. Breakthroughs in understanding the human genome and the development of precise gene editing tools have opened up unprecedented possibilities for advancements in healthcare, agriculture, and beyond.

Human Genome Project: The completion of the Human Genome Project in 2003…

View On WordPress

#CRISPR-Cas9#Gene Editing Technologies#Gene Therapy#Genetic Engineering in Agriculture#Genetics#Precision Medicine

0 notes

Text

"Artist genes" and the belonging enzymes have been created using the above mentiond tools and inserted into Lieuwe van Gogh's genome in order to elevate natural dispositions of creativity.

Sugababe, 2014-2021

by diemut strebe

replica of Vincent van Gogh’s ear, via mtDNA genome of great-great-great grandchild of Vincent’s mother

living genetically engineered, reprogrammed and immortalized chondrocytes seeded on a biodegradable scaffold, plasma, acrylic containers, pumpsystem, microphone, speakers

#van gogh#diemut strebe#mrna technology#genome editing#genetic engineering#tissue engineering#biodegradable#CRISPR-Cas9#theseus paradox#lieuwe van Gogh#vincent van Gogh’s ear#vincent van gogh

1 note

·

View note

Text

Using CRISPR-Cas9 to knock out asparagine gene in wheat to reduce cancer risk

A team of biologists from Rothamsted Research, the University of Bristol and Curtis Analytics Limited—all in the U.K.—has used the CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing system to knock out the asparagine gene in wheat grown in real-world conditions—part of an effort reduce the risk of cancer in people who consume food made from plants that produce the compound. The team has published an article describing…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

I just have to make it to june and then I get to go to an RNA conference headlined by jen doudna (and also see all my hoes in east coast area codes)

#I just need her to know who I am so that when I apply for Berkeley PhD she’ll go oh that guy and then I’ll get in no prablem#if you’re not familiar shes the berkeley RNA molecular biologist who won the Nobel for CRISPR-Cas9

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Rise of the TMNT Donatello Headcanons

(Based on things I or people I know have experienced.)

Long post ahead.

Donnie is a huge puzzle lover and every time he finds a new puzzle game to play, he rants/explains it to his brothers. (Leo tunes him out every time.)

On one such occasion, Donnie was ranting about the glorious creation of RegEx Crossword and Leo told him it seemed boring, so he's taken to writing Leo insults in RegEx shorthand.

When he was younger, Donnie would mess with his brothers by eating something that tasted disgusting and not reacting at all, then saying, "that was good," and giving his brothers the food to try.

Unfortunately for Leo, Donnie would usually go to his twin to infodump about a new topic, but it made Leo very good at gift-giving to Donnie.

Donnie is definitely touch-averted, but the kind where he will not tolerate touch from anyone at any time unless he initiates it. When he does initiate it, it is hard to get rid of him. (And in those cases it is rarely ever hugs, more like attacking Leo.)

Donnie frequently uses words like "hath," "doth," and "thou."

Donnie hates the phrase "me neither," and will get annoyed when his brothers say it. (It's NOR DO I or NOR HAVE I)

When Donnie is working in his lab, he gets very frustrated at any noise, even ambient noise, so when people walk into his lab during one of these moods, he will get very snippy with them.

When playing games like Headbanz or 20 Questions, Leo gets very annoyed because Donnie is way too specific. He will ask questions like "am I a vertebrate?" or argue semantics like whether ketchup is technically a fruit/fruit based. Eventually, this leads to both of them asking questions like, "in a nutrition label, would a fruit be one of the first three ingredients listed?"

Donnie is insanely curious and will constantly ask questions. Splinter used to lecture him about whatever topic he asked about when he was a child, but as he grew older he resorted to google or the library. (He is constantly bringing out his phone to google niche questions like, "the volume of a typical human body when fully liquefied including connective tissues.")

If he is into a task or project, he physically cannot sleep because his brain is thinking too much, and will stay up for hours without realizing it, but if he does not want to do something, it will take him literal days to do it, if at all.

He loves documentaries and video essays.

However, he also is a huge fan of any and all TV and movies. He has a list of movies he has heard people talk about that he wants to watch.

When watching sad movies, his brothers will periodically look over at him, trying to "catch" him crying because they cannot believe he does not cry during movies. Despite not crying though, Donnie gets extremely into movies and has to sit for a while afterward to process and then rant.

Donnie chews on things when he is preoccupied (especially because softshell turtles typically have a strong bite). This can be things like bottle caps, pens, and especially the hem of any shirt if he is wearing one. As such, all of his "human" clothes have holes in the collars.

Donatello is a very fast reader when he is interested in a topic, but if he is not interested, it is almost impossible to read because he just starts thinking about something else.

Similarly, he cannot read aloud because he reads too fast for his mouth to speak. This also causes him to frequently stutter or stumble when info dumping because his brain is going too fast to convey through spoken word.

He is extremely pretentious about grammar. For example, he constantly annoys Leo by pointing out any dangling participles.

Donnie is a very adept sarcasm user, but he frequently misses other people's sarcasm, especially Leo's.

He is a major perfectionist. When things go wrong or he is not immediately an expert at something, he gets very frustrated and snaps at those around him.

Donnie loves coffee, of course, but not to wake him up. He drinks coffee because it slows down his endless stream of ideas and plans enough for him to think. However, too much caffeine makes him sort of dazed or spacey.

Donnie is the type to be super organized and neat, but as soon as he starts a project, that goes out the window and his workspace becomes his own version of organized chaos.

Both he and Leo sign swears and insults at each other from across the room.

He loves cryptograms and fictional languages and will write messages in writing systems like Anglo-Saxon runes or alien languages (like from Jupiter Jim).

He LOVES drawing blueprints. He is decent artistic already (as shown by the chainsaw-made snow sculpture), but he really enjoys drawing blueprints with a straightedge and ruler and ends up hanging his favorites on the wall.

Donnie has a very high pain tolerance and would do things like poke needles through his epidermis to freak his brothers out.

He is a collector of junk. While most of it is sectioned off and organized, he also has bins of spare wires, screws, and tubes.

When he was young, he took apart everything. Nothing was ever safe. Radios, music boxes, flashlights, etc., all would be taken apart and strewn about to be studied.

Donnie is a proud Oxford Comma supporter!

He cannot use the same dish twice. If it is out of his sight for a minute, it is automatically contaminated. (Splinter hates this)

He loves nerdy science songs or science parodies of songs.

However, he also loves musical theatre and does mini performances of soundtracks.

He is constantly over-prepared. He keeps a first aid kit, flashlight, swiss army knife, pen, pencil, etc. in his battle shell at all times.

Because Donnie is much more flexible than his brothers due to his soft shell, he often sits in weirdly contorted positions that they cringe at.

When he was 5, Splinter wrote "good job" on a slip of paper and Donnie has kept it ever since.

He talks like an old man. For instance, he complains about "punk youths" and the state of the younger generations, despite being one of the said punk youths.

This is all for now. I always think of more, so I may make a second post of this with new ones I think of. Most of these are just from my own childhood.

#rise donnie#rise mikey#rise raph#rise leo#rottmnt#rise tmnt#rottmnt donnie#teenage mutant ninja turtles donnie#autism#donnie headcanons#if you do not use oxford commas leave#somebody needs to make more regex crosswords i have finished them all#my sister will no longer play 20 questions with me#crispr-cas9 (bring me a gene) is the best song ever#this is a formal apology to all of the children I tricked into eating orange peels#I have bullied my friends into never saying me neither again#donnie hypermobility headcanon but very lowkey#someone told me today I should be on the the speech team because I was infodumping#if you have not played 0h h1 you should#donnie probably says back in my day#He would love Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep and The Hitchhiker's Guide series.

75 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Axon Ax-off

Like trees growing in the wild, the branches or axons of our nerve cells reach out as they develop. In the optic tract of a zebrafish, some branches of these retinal ganglion cells are ‘pruned’ to guide the accurate shape of circuits behind its eyes. Like snipping at a bonsai tree (although about 1000 times smaller), cells on one side of the tract (highlighted in red) send signals that help to cut off stray axons of cells on the other side (blue), leaving grouped or 'sorted' neurons behind (seen on the right). Researchers using CRISPR/Cas9 technology block the activity of ones of the genes involved, gpc3, leaving the optic tract in a disorganised unpruned state (left and middle). Insight into this molecular tree surgery might influence therapies for the human brain, which also uses a form of gpc3 – offering a helping hand in shaping neural circuits that develop errant branches.

Written by John Ankers

Image from work by Olivia Spead, Trevor Moreland and Cory J. Weaver, and colleagues

Department of Biological Sciences, University of South Carolina, Columbia, SC, USA

Image originally published with a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0)

Published in Cell Reports, February 2023

You can also follow BPoD on Instagram, Twitter and Facebook

#science#biomedicine#axons#neurons#neuroscience#zebrafish#crispr#gene editing#retina#crispr/cas9#neural circuits#immunofluorescence

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

Etica a genetica un binomio forse impossibile

I primi dieci anni di CRISPR.Il sistema per modificare pezzi di DNA con estrema precisione ha rivoluzionato la ricerca e ha aperto molte questioni etiche ancora da risolvere

Alla fine di giugno del 2012, sulla rivista scientifica Science fu pubblicata una ricerca che non attirò da subito particolari attenzioni, ma che in seguito si sarebbe rivelata centrale per una delle più grandi rivoluzioni della scienza moderna: la possibilità di modificare velocemente, con precisione e a basso costo il DNA per trattare problemi di salute finora incurabili, creare piante resistenti a un clima sempre più caldo e prevenire le malattie genetiche. Lo studio era soprattutto il frutto del lavoro di due scienziate, Emmanuelle Charpentier e Jennifer A. Doudna, che circa otto anni dopo sarebbero state premiate con il Nobel per la Chimica per CRISPR/Cas9, il loro sistema per modificare pezzi del materiale genetico.

A distanza di dieci anni dalla pubblicazione di quella prima ricerca, CRISPR è diventato una delle più importanti innovazioni della biologia. Viene impiegato quotidianamente in centinaia di laboratori in giro per il mondo per capire quale sia il ruolo di particolari geni, l’unità ereditaria fondamentale degli esseri viventi.

I geni sono costituiti da sequenze di DNA e contengono le istruzioni per produrre specifiche proteine, che portano poi all’espressione di particolari caratteristiche fisiche (tratti) come il colore degli occhi o dei capelli, oppure particolari funzioni delle cellule. Il loro studio è fondamentale per capire che cosa può andare storto nel nostro organismo, causando disfunzioni e malattie. CRISPR rende inoltre possibile la modifica di porzioni del materiale genetico, in modo da attivare o disattivare alcuni geni.

A dirla tutta, Charpentier e Doudna dieci anni fa non inventarono qualcosa di nuovo, ma trovarono il modo di sfruttare un meccanismo presente in alcuni batteri e che era stato notato dai microbiologi a partire dagli anni Ottanta. All’epoca, erano state scoperte alcune porzioni di DNA fatte diversamente da quanto ci si sarebbe aspettati, e per un buon motivo.

Batteri vs virus

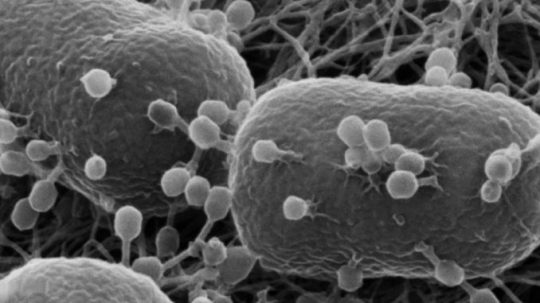

Tendiamo a pensare che batteri e virus siano un pericolo per noi e gli altri animali, ma in realtà questi patogeni sono in guerra tra loro praticamente da quando esistono. I batteriofagi (o fagi), per esempio, sono un particolare tipo di virus che va a caccia dei batteri. Lo fanno sistematicamente, tanto che si stima che da soli causino giornalmente la morte del 40 per cento circa dei miliardi di miliardi di batteri che vivono a mollo negli oceani. La lotta è strenua e i batteri riescono a non estinguersi grazie alla rapidità con cui si moltiplicano, formando miliardi di nuovi esemplari ogni giorno e utilizzando alcune particolari difese.

Quando i fagi entrano in contatto con i batteri, iniettano al loro interno il proprio materiale genetico, trasformando i batteri in piccole fabbriche che produrranno nuove copie dei virus che a loro volta infetteranno altri batteri. È il principio base di funzionamento di numerosi virus, come abbiamo ormai imparato in oltre due anni di pandemia. A differenze del nostro organismo, i batteri hanno sistemi di difesa meno elaborati e spesso falliscono nel resistere all’invasore virale.

Batteriofagi all’attacco di alcuni batteri di E. coli, le strutture più grandi (Wikimedia)

Ci possono però essere alcune circostanze in cui i batteri riescono a respingere l’attacco da parte dei batteriofagi, con una soluzione semplice e al tempo stesso raffinata. I batteri trasferiscono parte del materiale genetico del virus nel loro codice genetico, creando una sorta di catalogo che viene appunto chiamato CRISPR, da clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats (brevi ripetizioni palindrome raggruppate e separate a intervalli regolati).

Se il batterio entra nuovamente in contatto con un virus, produce una copia del materiale genetico che aveva archiviato e la passa a una proteina che si chiama Cas9. Lavorando come un’archivista, questa si mette al lavoro e cerca nel batterio pezzi di DNA e li confronta con quelli in archivio, per capire se stia avvenendo un attacco da parte di un virus. Nel caso in cui rilevi una corrispondenza, taglia la sequenza genetica appartenente al virus, rendendola in questo modo innocua. Non essendoci più istruzioni complete, il batterio non può diventare la fabbrica di nuovi virus e non rischia di fare una brutta fine.

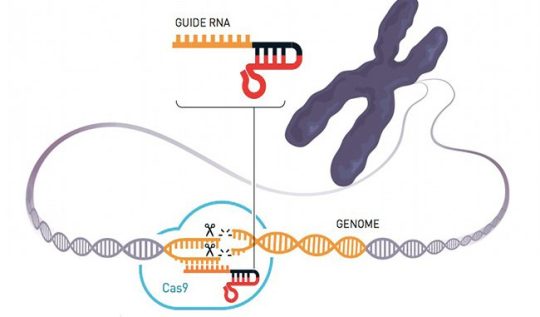

CRISPR/Cas9

Cas9 è una proteina molto accurata nel tagliare pezzi di DNA, come ebbero modo di sperimentare Charpentier e Doudna nei loro laboratori e analizzando le ricerche svolte in precedenza. Si chiesero quindi se potessero sfruttare Cas9 per trasformarla in una specie di sarta del materiale genetico, per modificarlo tagliandone e copiandone pezzi, cucendoli se necessario altro lungo la doppia elica del DNA. Riuscirci non fu semplice, ma quando infine nel 2012 realizzarono il primo sistema di “forbici genetiche”, quelle descritte nel loro studio, capirono di avere realizzato qualcosa dalle enormi potenzialità e che avrebbe poi portato allo sviluppo di altre soluzioni simili (noi ci concentreremo soprattutto su Cas9).

Le forbici di CRISPR/Cas9 partono da una sequenza genetica (RNA guida) preparata in laboratorio che corrisponde a quella del DNA dove si deve effettuare il taglio nella cellula. La proteina Cas9 si attiva e realizza il taglio: in mancanza di altre istruzioni, la cellula ripara il proprio DNA perdendo un pezzo del codice genetico, in molti casi rendendo inutilizzabile proprio il gene che il gruppo di ricerca voleva disattivare. Questo sistema permette inoltre di inserire del nuovo DNA nella fase di riparazione, nel caso in cui si voglia invece modificare il funzionamento della cellula.

Malattie genetiche e piante

CRISPR ha rivoluzionato il modo di fare editing perché in precedenza modificare i geni era estremamente difficile, richiedeva molto tempo e spesso portava a risultati poco affidabili. In dieci anni il nuovo sistema si è mostrato affidabile, per quanto ancora perfettibile, ed è diventato diffuso in numerosi ambiti della ricerca e con prime applicazioni pratiche in ambito sanitario.

Uno degli ambiti più promettenti per CRISPR si è dimostrato essere lo sviluppo di nuove terapie contro le malattie ereditarie. Alcune settimane fa, per esempio, sono stati presentati i primi risultati di un test clinico condotto su 75 volontari affetti da anemia mediterranea o da anemia falciforme, due malattie ereditarie del sangue che riducono la capacità del sangue di trasportare ossigeno tramite l’emoglobina.

Gli autori dello studio hanno sfruttato il fatto che gli esseri umani possiedono diversi geni che regolano l’emoglobina. Uno di questi è legato all’emoglobina fetale, che come suggerisce il nome è attiva solamente nei feti e si disattiva poi a qualche mese dalla nascita. Dal midollo osseo dei volontari sono state quindi prelevate cellule non ancora specializzate, poi con CRISPR è stato escluso il gene responsabile della disattivazione del meccanismo dell’emoglobina fetale. Le cellule modificate sono state poi trasfuse nuovamente nei volontari, che hanno così iniziato a produrre l’emoglobina necessaria al sangue per trasportare l’ossigeno.

Su 44 volontari con anemia mediterranea, dopo il trattamento 42 non hanno più avuto bisogno di sottoporsi periodicamente alle trasfusioni di sangue, come devono fare solitamente le persone con questa malattia. I risultati sono stati promettenti anche per i malati di anemia falciforme e per questo le due aziende coinvolte nello sviluppo del sistema, CRISPR Therapeutics e Vertex chiederanno presto alle autorità sanitarie statunitensi un’autorizzazione per il loro trattamento.

CRISPR Therapeutics è stata cofondata da Charpentier e ha vari progetti di ricerca in corso. Anche Doudna ha cofondato una propria azienda, Caribou Biosciences, impiegata in altre sperimentazioni nel settore sempre basate sull’editing con CRISPR.

Altre importanti aree di sperimentazione e applicazione sono legate alla ricerca contro il cancro. Già nei primi anni dopo la pubblicazione dello studio, numerosi gruppi di ricerca avevano iniziato a utilizzare CRISPR per capire meglio il ruolo di alcuni geni e disattivarli, osservandone le conseguenze in laboratorio. In questo modo è stato per esempio possibile scoprire un gene con un ruolo centrale nella crescita di alcuni tipi di tumore, portando poi allo sviluppo di un farmaco per inibire la sua attività in modo da fermare la diffusione delle cellule cancerose nell’organismo.

In altri ambiti, per esempio quello agricolo, CRISPR può essere utilizzato per produrre piante più resistenti e per migliorare la resa dei raccolti. In questi anni sono state per esempio sperimentate soluzioni per rendere la soia e i cereali più resistenti alla siccità, facendo in modo che abbiano bisogno di meno acqua per crescere.

Sperimentazioni sulle piante utilizzando CRISPR/Cas9, presso l’Istituto Leibniz per la genetica delle piante e la ricerca sulle piantagioni a Gatersleben, Germania (Sean Gallup/Getty Images)

Altre sperimentazioni hanno riguardato soluzioni per rendere le piante più resistenti ai parassiti o ancora in grado di crescere in condizioni ambientali non ottimali, in modo da dover ricorrere con minore frequenza agli antiparassitari e ai fertilizzanti. Piante di questo tipo non solo potrebbero contribuire a ridurre i rischi che si verifichino crisi alimentari, a livello locale o globale come quella degli ultimi mesi, ma anche di migliorare la resa dei campi in termini energetici, dovendo produrre meno prodotti chimici per favorire la crescita nei campi.

Etica, costi e opportunità

Risultati simili erano già stati ottenuti prima dell’introduzione di CRISPR, ma con tecniche più costose e minori opportunità per i centri di ricerca più piccoli di condurre sperimentazioni rilevanti. Come era già emerso all’epoca, la possibilità di creare piante geneticamente modificate porta con sé numerose complicazioni, legate sia alla percezione della loro sicurezza da parte della popolazione, sia per le opportunità commerciali che spingono le grandi multinazionali a brevettare le loro sementi OGM, rendendole talvolta meno accessibili, soprattutto per i paesi più poveri.

L’impiego di CRISPR, come di altre tecniche di editing del genoma, pone poi vari temi etici, considerate le ampie possibilità nell’alterazione degli embrioni umani. Se ne discusse molto nel 2018, quando il ricercatore cinese He Jiankui, annunciò la nascita di una coppia di gemelle modificate geneticamente, cui si aggiunse un altro bambino pochi mesi dopo. He aveva modificato un embrione umano con l’obiettivo di ottenere una resistenza all’HIV, il virus che può portare all’AIDS.

La notizia fu ampiamente commentata e criticata nella comunità scientifica, e non solo, per le numerose implicazioni che avrebbe potuto avere e per la salute dei neonati coinvolti. Nel 2019 un tribunale cinese condannò a tre anni di carcere He per pratiche mediche illecite, mentre non si sono più avute notizie chiare sullo stato di salute dei tre bambini.

He rimane a oggi l’unico caso noto di un ricercatore che si sia spinto così avanti, ma CRISPR pone molte domande sulle potenzialità per intervenire sugli embrioni e modificarne il corredo genetico. A fini terapeutici è una grandissima opportunità, ma potrebbe avere altri esiti difficili da governare. Ci si chiede per esempio fino a dove si potrebbero un giorno spingere i futuri genitori di un bambino nel richiedere modifiche: un conto sarebbe escludere il rischio di una malattia genetica invalidante, un altro scegliere altri tratti come il colore degli occhi o dei capelli.

Con le tecniche attualmente disponibili, siamo ancora lontani da questa eventualità, ma i progressi degli ultimi anni non fanno escludere che un giorno nemmeno troppo lontano le possibilità di avere ampia scelta sulle modifiche per gli embrioni. È un problema su cui si stanno interrogando esperti, comitati etici e i governi, con un confronto estremamente delicato i cui esiti condizioneranno buona parte della ricerca medica, e più in generale delle discipline biologiche, dei prossimi decenni.

Un approccio eccessivamente rigido potrebbe far perdere importanti opportunità per migliorare la salute di milioni di persone, bloccando importanti progressi nel settore, sostiene chi è più restio a introdurre nuove leggi e regolamenti. Al contrario, chi vorrebbe regolamentare più rigidamente l’editing del genoma sostiene che sia l’unico modo per evitare storture o il rischio che alcune soluzioni siano accessibili solo ai più ricchi, che potrebbero permettersi pratiche mediche brevettate e molto costose.

La modifica degli embrioni a livello del DNA continua comunque a essere un’attività difficile: CRISPR ha reso più accessibili alcune tecniche per farlo, ma sono emersi altri ostacoli legati a come si riorganizza il materiale genetico nelle cellule nel caso di particolari modifiche. Il sistema esiste del resto da appena dieci anni ed è considerato un importante punto di partenza, verso una meta ancora distante, ma che appare meno irraggiungibile di un tempo.

Read the full article

#batteri#batteriofagi#Cas9#Crispr#Crispr-Cas9#crispr/cas9#Dna#embrioni#EmmanuelleCharpentier#fagi#genetica#geni#JenniferA.Doudna#malattiegenetiche#modificaDNA#salute#virus

0 notes

Text

Genetically Modified Pluripotent Stem Cells May Evade Immunological Rejection After Transplantation - Technology Org

New Post has been published on https://thedigitalinsider.com/genetically-modified-pluripotent-stem-cells-may-evade-immunological-rejection-after-transplantation-technology-org/

Genetically Modified Pluripotent Stem Cells May Evade Immunological Rejection After Transplantation - Technology Org

Researchers say the genetically engineered stem cells also could pave the way for new regenerative medicine treatments for diseases such as Type 1 diabetes.

Deepta Bhattacharya, who is on the University of Arizona Health Sciences Center for Advanced Molecular and Immunological Therapies advisory council, is a professor of immunobiology in the UArizona College of Medicine – Tucson. Image credit: UArizona Health Sciences

One of the biggest barriers to regenerative medicine is immunological rejection by the recipient, a problem researchers at the University of Arizona Health Sciences are one step closer to solving after genetically modifying pluripotent stem cells to evade immune recognition.

The study “Engineering Human Pluripotent Stem Cell Lines to Evade Xenogeneic Transplantation Barriers” was published in the journal Stem Cell Reports last week.

Pluripotent stem cells can turn into any type of cell in the body. The findings offer a viable path forward for pluripotent stem cell-based therapies to restore tissues that are lost in diseases such as Type 1 diabetes or macular degeneration.

“There has been a lot of excitement for decades around the field of pluripotent stem cells and regenerative medicine,” said principal investigator Deepta Bhattacharya, a professor in the UArizona College of Medicine – Tucson’s Department of Immunobiology. “What we have learned from the experiences of organ transplantation is that you have to have matched donors, but the person receiving the transplant often still requires lifelong immune suppression, and that means there is increased susceptibility to infections and cancer. We’ve been trying to figure out what it is that you need to do to those stem cells to keep them from getting rejected, and it looks like we have a possible solution.”

To test their hypothesis, Bhattacharya and the research team used CRISPR-Cas9 technology, “genetic scissors” that allow scientists to make precise mutations within the genome at extremely specific locations.

Using human pluripotent stem cells, the team located the specific genes they believed were involved in immune rejection and removed them. Prior research into pluripotent stem cells and immune rejection looked at different parts of the immune system in isolation. Bhattacharya and his colleagues from The New York Stem Cell Foundation Research Institute, St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital and the Washington University School of Medicine opted to test their genetically modified stem cells in a complete and functional immune system.

“The immune system is really complicated and there are all sorts of ways it can recognize and reject things,” said Bhattacharya, a member of the UArizona Cancer Center and the BIO5 Institute who also serves on the UArizona Health Sciences Center for Molecular and Immunological Therapies advisory council.

“Transplantation across species, across the xenogeneic barrier, is difficult and is a very high bar for transplantation. We decided if we could overcome that barrier, then we could start to have confidence that we can overcome what should be a simpler human-to-human barrier, and so that’s basically what we did.”

The research team tested the modified stem cells by placing them into mice with normal, fully functioning immune systems. The results were promising – the genetically engineered pluripotent stem cells were integrated and persisted without being rejected.

“That has been the holy grail for a while,” Bhattacharya said. “You might actually have a chance of being able to perform pluripotent stem cell-based transplants without immune suppressing the person who is receiving them. That would be an important advance, both clinically and from the simple standpoint of scale. You wouldn’t have to make individualized therapies for every single person – you can start with one pluripotent stem cell type, turn it into the cell type you want and then give it to almost anyone.”

The next steps, Bhattacharya said, include testing the genetically modified pluripotent stem cells in specific disease models. He is already working with collaborators at The New York Stem Cell Foundation and the Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation to test the technology in animal models for Type 1 diabetes.

“We needed to overcome the immune system first,” Bhattacharya said. “The next steps are how do we use these cells? We set the bar pretty high for our study and the fact that we were successful gives us some confidence that this can really work.”

Bhattacharya also is the co-founder of startup Clade Therapeutics in Boston, which licensed the technology through Tech Launch Arizona, the University of Arizona’s commercialization arm. Clade Therapeutics is establishing a robust cellular platform using stem cell-derived immune cells for the treatment of cancer and autoimmune diseases. The company said it hopes to begin clinical trials by the end of the year.

Co-authors on the paper include Hannah Pizzato, research specialist in the College of Medicine – Tucson’s Department of Immunobiology; Dr. Paula Alonso-Guallart, James Woods and Frederick J. Monsma Jr. of The New York Stem Cell Foundation Research Institute; Jon P. Connelly and Shondra M. Pruett-Miller of the St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital; and Dr. Todd A. Fehniger and John P. Atkinson of the Washington University School of Medicine.

This work was supported in part by the National Institutes of Health under award no. R21AI132910 and the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation (OPP1206188).

Source: University of Arizona

You can offer your link to a page which is relevant to the topic of this post.

#Aging news#arm#autoimmune diseases#barrier#Biotechnology news#Cancer#cell#cell lines#Cells#Children#college#CRISPR#CRISPR-Cas9#diabetes#Disease#Diseases#engineering#Featured life sciences news#Foundation#genes#genetic#Genetic engineering news#genome#Health#Health & medicine news#how#human#immune cells#immune system#immunological rejection

1 note

·

View note

Link

The UK has achieved a historic milestone by becoming the first country to authorize a revolutionary new treatment for two serious inherited blood conditions – sickle cell disease and beta-thalassemia. The cutting-edge therapy utilizes CRISPR gene editing technology to precisely correct errors in patients’ blood stem cells, potentially curing them of debilitating symptoms.

Announced earlier this week, the treatment called Casgevy (exagamglogene autotemcel) has been approved for use by the Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency (MHRA). This landmark decision opens the door for this powerful gene editing approach to start benefiting eligible patients after final assessments by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE).

Casgevy targets two blood disorders sharing an underlying mutation that reduces normal hemoglobin levels. Sickle cell disease distorts red blood cells into inflexible sickled shapes, causing severe pain, organ damage, and shortened lifespan. An estimated 15,000 people in the UK live with this painful condition.

Continue Reading

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

CRISPR-Cas9: A Gene-Editing Revolution

Imagine wielding a microscopic scalpel, sharp enough to snip and edit the very blueprint of life itself. Sounds like science fiction, right? Not anymore! CRISPR-Cas9, a name that has become synonymous with scientific breakthroughs, holds immense potential to revolutionize various fields, from medicine to agriculture. But what exactly is this technology, and how does it work? Let's delve into the world of CRISPR-Cas9, unraveling its complexities and exploring its exciting possibilities.

The story begins not in a gleaming lab, but in the humble world of bacteria. These tiny organisms possess a unique immune system that utilizes CRISPR (Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats) sequences and Cas9 protein. When a virus attacks, the bacteria capture snippets of viral DNA and store them as CRISPR arrays. The Cas9 protein, guided by these arrays, then snips the matching viral DNA, rendering the virus harmless.

Scientists, inspired by this natural marvel, realized they could harness the power of CRISPR-Cas9 for their own purposes. By tweaking the guide RNA (the mugshot), they could target specific locations in any genome, not just viral DNA. This opened a new era of genome editing, allowing researchers to add, remove, or alter genes with unprecedented precision.

CRISPR-Cas9 holds immense promise for various fields:

Medicine: Gene therapies for diseases like cancer, sickle cell anemia, and Alzheimer's are being explored.

Agriculture: Crops resistant to pests, diseases, and climate change are being developed.

Biotechnology: New materials, biofuels, and even xenotransplantation (animal-to-human organ transplants) are potential applications.

As with any powerful technology, CRISPR-Cas9 raises ethical concerns. Modifying the human germline (sperm and egg cells) could have unintended consequences for future generations, and editing embryos requires careful consideration and societal dialogue.

So, is CRISPR-Cas9 the key to unlocking a genetically modified future? The answer is as complex as the human genome itself. But one thing's for sure, this revolutionary tool is rewriting the rules of biology, and the plot is just getting started. CRISPR-Cas9 is still in its early stages, but its potential is immense. As we continue to refine the technology and address ethical concerns, it has the power to revolutionize various fields and improve our lives in countless ways. However, responsible development and open discussion are crucial to ensure this powerful tool benefits humanity without unintended consequences.

#crispr cas9#biotechnlogy#molecular biology#laboratory#gene therapy#gene editing#microbiology#science#DNA#science sculpt#life science#life#biology

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

log #1

have you heard of crispr before? because i think you look crispr cas- fine

67 notes

·

View notes

Text

CRISPR Cas9 therapy targeting people living with HIV

CRISPR Cas9 therapy targeting people living with HIV

WORLDWIDE (Precision Vaccinations)

Recent announcements indicate innovative technologies may provide new clinical solutions for the 36.9 million people living with HIV/AIDS worldwide.

“Dosing the first participant with EBT-101 is a landmark event that solidifies Excision’s position as a pioneer in gene editing,” said Daniel Dornbusch, Chief Executive Officer of Excision, in a related press…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

hey sorry i used crispr on your boyfriend. yeah it deleted his whole dna. im so sorry you had to find out this way

17 notes

·

View notes